Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Farmers Grow A New Stream of Revenue Through Vertical Farming

Farmers Grow A New Stream of Revenue Through Vertical Farming

Combining hydroponic techniques with new timer control innovations

In January, the open fields of Harvard, IL, a far northwestern suburb of Chicago, are biting and bone-chilling. Inside Kirk Cashmore’s barn, it is a fair 72 degrees F, the perfect temperature for producing leafy heads of lettuce through vertical hydroponics, the practice of water-based gardening with vertically stacked shelving in a controlled environment.

Since 2011, Kirk Cashmore has been the only for-profit vertical hydroponic farmer in Northern Illinois. His pesticide- and chemical-free lettuce is served at a popular, Green-certified restaurant, Duke’s Alehouse and Kitchen, in nearby Crystal Lake, IL, and sold at biweekly basket drops along the North Shore and in the Madison, WI metro area.

“Working for my grandfather as a big acre farmer for many years taught me how things worked. I always knew I wanted to be a farmer, but wanted to take a different approach to it. I didn't have the capital or the money to buy big acres to start a traditional farm, so I went around the Midwest and looked at farms that were growing hydroponically and figured out how to start my own,” said Cashmore.

A Growing Industry

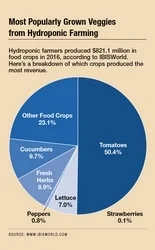

According to a recent market research report, the vertical farming market is estimated to be valued at 5.8B U.S. dollars by 2022, growing at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 24.8% between 2016 and 2022. Factors driving growth of the vertical farming market include generating high quality food without the use of pesticides, less dependency on the weather for production, a growing urban population, an increase in the year around production of crops, and reduced impact on the environment.

“The beauty of hydroponic farming is there really is no downtime… I have assets throughout the whole winter and am the only game in town when it comes to winter production of lettuce, Swiss chard, kale, and all the small greens that can be harvested hydroponically,” he remarked. None of his yield is ever wasted. Unsold, yet still edible, greens are donated to a local food pantry and wilted or damaged heads are sent to the compost bin.

Inside Cashmore’s 3,500 square foot building, three vertically stacked shelves, built from recycled materials, provide room for up to 4,000 heads of lettuce. Each shelf grows approximately 1,200 heads, or about five heads per square foot, which Cashmore reports is the number to beat in the world of vertical hydroponics. With room in his barn to still expand out- and upwards, Cashmore has the potential to harvest nearly 8,000 heads.

Plants are seeded in rockwool, a lava-like medium that allows for more oxygen than does soil or water, and an ebb and flow pumping system supplies water to the roots. Cashmore checks pH levels daily.

Winter in the Midwest means long periods of grey, cloudy skies. An electronic timer ensures lights remain on based on the amount of sun, typically 16 hours a day, 7 days a week. Relying on the timer to turn lights on and off as needed gives Cashmore – a one-man show – the freedom to tend to other business without worrying. “Timers are very important for turning lights and fans on and off,” stated Cashmore. “Having an electronic timer makes this an automated sport, so I can have more time with my family and friends. It gives me more time to not have to work.”

He also believes that ensuring a good supply of oxygen is absolutely vital to growing success. Floating rafts of lettuce -- or any system where roots are permanently soaked in water -- offer little available oxygen since the solubility of oxygen in water is remarkable low. Cashmore monitors how much oxygen his roots have and uses an ozone system to kill bacteria, control oxygenation, and keep the water sanitized. This has eliminated the need to use chemicals such as chlorine or hydrogen peroxide.

“I find that if something is worth doing, it's worth doing right. As a father of three little girls, I have no tolerance for chemicals going home and into my kids’ mouths. I want to make the best produce that I can for my family, my clients and my friends,” he explained.

Organically Grown Produce That’s Bug-Chemical-and Pesticide-Free

One of the biggest benefits of hydroponic farming is the superb quality of the produce. Plants don’t spend any time outside in the wind, dirt or the rain; they grow in a controlled environment that is bug-, chemical- and pesticide free. This creates greens with an unmatched body and texture. As more and more people buy organic and seek out locally grown produce, demand is certain to grow. Cashmore envisions remaining profitable and productive by adding more capacity to double or triple lettuce headcount and growing a variety of other vegetables in the winter.

“From school field trips to other farmers and private citizens, there’s an increasingly large interest in my hydroponics facility. I hope to see more vertical hydroponic farms popping up in the area over the next decade.”

Do you have a budding interest in vertical hydroponic farming? Learn more with an in-depth look at Kirk Cashmore’s farm.

Singapore Turns Vacant Space Into Urban Farms

ENVIRONMENT | Thu Jun 29, 2017 | 7:27am EDT

Singapore Turns Vacant Space Into Urban Farms

Head of farmers at Citizen Farm Darren Ho poses in front of an urban farm in Singapore June 20, 2017. REUTERS/Thomas White

Resource-scarce Singapore is turning vacant pockets of land into space for urban farming as the island city strives to ease its reliance on imported food.

The wealthy Southeast Asian city-state imports more than 90 percent of its food, much of it from neighboring countries, which can leave it exposed to potential supply chain disruptions.

Edible Garden City, a company with a grow-your-own-food message, has designed and built more than 50 food gardens in the tropical city for clients ranging from restaurants and hotels to schools and residences.

One of its projects is Citizen Farm, an 8,000 square meter plot that used to be a prison, converted into an urban farm "where the local community can learn and grow together", according to the project website.

Citizen Farm produces up to 100 kg of vegetables, 20 kg of herbs and 10-15 kg of mushrooms - enough to feed up to 500 people - a day.

It's tiny compared with demand for food in the country of 5.5 million people, but it's a start, said Darren Ho, head of the Citizen Farm initiative.

"No system will replace imports, we are here to make us more food resilient," said Ho, adding that it was "up to the community" to decide how self-sufficient it wants to be.

Government agencies are considering the company's urban farming concept for other parts of the city, including spaces around high-rise public housing.

(Reporting by Fathin Ungku)

Wisconsin Fish Farming Sees Growth After Decade of Stagnation

Superior Fresh, a high tech fish farm and aquaponics facility, overlooks I-94 in the unincorporated town of Northfield. The company claims it will be able to produce 160,000 pounds of Atlantic salmon and rainbow trout along with nearly 2 million pounds of leafy greens per year. Rich Kremer/WPR

Wisconsin Fish Farming Sees Growth After Decade of Stagnation

New Aquaculture Businesses Led By New Generation Of Farmers

Monday, June 26, 2017, 3:50pm | By Rich Kremer

Listen Download

Fish farming in Wisconsin has traditionally centered around raising bait and sport fish for the state's anglers. But after a 10-year lull, the state's aquaculture industry is seeing growth and new farms are raising fish destined for the dinner plate.

There are 2,500 registered fish farms in Wisconsin, but fewer than 350 raise fish as a business. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, sales from Wisconsin fish farms declined between 2005 and 2013.

University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point biology professor Chris Hartleb has tracked the state's aquaculture industry for years.

"For the past 10 years or so Wisconsin’s aquaculture industry has kind of been stagnant," Hartleb said. "It hasn’t really lost businesses, but it hasn’t gained any. I would say in the past three years there’s been this kind of resurgence in Wisconsin aquaculture, where not only are new businesses starting to open up but it’s younger generation people starting those businesses."

Superior Fresh

On a hill overlooking the unincorporated community of Northfield, just off Interstate-94 in Jackson County, a green metal building, two acres of Plexiglas and a red barn stand out in the surrounding sea of farm fields. This is the home of Superior Fresh, a multimillion dollar fish farm and aquaponic greenhouse capable of producing 160,000 pounds of Atlantic salmon and rainbow trout and up to 2 million pounds of varietal, leaf lettuce per year.

It’s hailed as the first privately owned, indoor, Atlantic salmon farm in America. Currently, there is a combination off around 60,000 salmon and rainbow trout in their early life stages.

Superior Fresh COO Brandon Gottsacker said they hope to ramp up to 75,000 by next year.

Nearly everything these young fish experience is computer controlled. Gottsacker and his team are able to use water temperature and lighting to fool the Atlantic salmon into believing they’ve gone through a winter, which triggers the fish to transition from fresh to saltwater and put on the majority of its weight.

"Inside our building we can grow these fish a little bit quicker than outdoor farms because we give the fish an optimum environment to live in their entire life," Gottsacker said. "So, we avoid winters and super cold water that would slow fishes metabolism down and ultimately their growth."

With this level of control, Gottsacker claims Superior Fresh will be able to grow their fish a year or two faster than in the wild or traditional salmon farms that use net pens in the ocean.

But with nearly 100,000 fish in an indoor facility one would expect fish waste to be a liability. For an aquaponics facility like Superior Fresh it’s part of their business model.

Brunno Cerozi is in charge of recirculating water between the fish house and the 123,000-square-foot greenhouse next door.

Superior Fresh COO Brandon Gottsacker and production manager Brunno Cerozi in the greenhouse where they’re processing leaf lettuce, which gets its water and nutrients from the fish house next door. Photo courtesy of Superior Fresh

"So, we feed the fish. They will take the nutrients that they need to grow and all the nutrients that they don’t use we recycle through the plants," Cerozi said. "So, that in a conventional aquaculture system would be wasted, would be polluting the environment, would be released into our natural water bodies and would be causing major environmental problems."

Standing next to a series of long, shallow pools with floating mats covered with heads of romaine, red leaf and butter lettuce, head grower Adam Shinners said he can grow greens nearly twice as fast as in the field and in a fraction of the acreage.

"I definitely believe that this is the future. The amount of space we utilize here is so much less than traditional agriculture, and we can keep this production going year-round, which is definitely something that’s going to be needed, especially in northern hemispheres," Shinners said.

Changing Regulations

In an effort to spur the growth of more fish farming and aquaponics facilities such as Superior Fresh, state Sen.Tom Tiffany, R-Hazelhurst, sponsored a bill easing regulations for the state’s aquaculture industry.

He said under the previous law fish farms weren’t treated as favorably as traditional agriculture.

Tiffany claimed fish farms were subject to similar rules by both the state Department of Natural Resources and the state Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection, which drove up costs for producers.

"What we did was we wanted to streamline some of the regulatory functions, not change any environmental standards, but just streamline the process and really give greater opportunity for people in the aquaculture industry because there’s no reason we don’t have a more robust, growing aquaculture industry," Tiffany said.

Tiffany first introduced his aquaculture bill in 2016, but it got a cool reception and was opposed by a number of environmental groups. After being retooled the senator re-introduced the bill this year and it passed unanimously in the state Senate. But it was still opposed by groups including environmental law firm Midwest Environmental Advocates.

Midwest Environmental Advocates attorney Sarah Geers calls Tiffany’s bill, now signed into law, a giveaway of the state’s water resources to the aquaculture industry.

"There are concerns about the waste coming out of all those fish and adding to algae concerns, additional nutrients from any feed given to them," Geers said. "It also raises questions about when fish are brought in from elsewhere creating problems for invasive species and cutting off so much of the water supply from the stream that the native fish population might be threatened."

Whether Tiffany’s bill will spur an aquaculture revolution in Wisconsin remains to be seen, but for the team at Superior Fresh, there is excitement about the future.

If all goes well, Gottsacker said they would considering building a new operation 10 times the size of the facility in Northfield.

This story is part of a yearlong reporting project at WPR called State of Change: Water, Food, and the Future of Wisconsin. Find stories on Morning Edition, All Things Considered, The Ideas Network and online.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2017, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.

Gurugram Adopts Soil-Less Farming and Shows How Easy It Is to Eat Chemical-Free!

A project commissioned by the Harayana Department of Horticulture is supplying safe, chemical-free fruit and vegetables to residents of Delhi and Gurugram and encouraging a new generation of urban farmers in India.

Gurugram Adopts Soil-Less Farming and Shows How Easy It Is to Eat Chemical-Free!

A project commissioned by the Harayana Department of Horticulture is supplying safe, chemical-free fruit and vegetables to residents of Delhi and Gurugram and encouraging a new generation of urban farmers in India.

by Lucy Plummer

Residents across Gurugram and Delhi are enjoying the benefits of safe, chemical-free produce grown from a soil-less environment thanks to a project set up by three friends and commissioned by the Haryana Department of Horticulture.

In a system already attracting hordes of India’s new-age farmers, crops are being grown in Panchgaon village, Manesar, without the use of soil, meaning that they are free from pest and disease attacks, chemical-free and nutrient-dense.

The produce is being supplied to residents of nearby cities Delhi and Gurugram through bulk buyers.

A hydroponic set-up. Photo Source: Urban Farm via Facebook

“This is the future of farming and vegetable cultivation. Instead of soil, coconut fibre is used to fill the pots and liquid nutrients are provided in a controlled environment,” Din Mohammad Khan, District Horticulture Officer, told Hindustan Times.

The project was set up in 2015 by three friends, Rupesh Singal, Avinash Garg and Vinay Jain, all IT professionals. It uses indoor farming techniques in a controlled environment. Some of the crops produced on-site include tomatoes, European cucumber, cherry tomatoes, bell peppers, basil, parsley and rosemary, which all come from locally sourced seeds. The capital investment made has been reported at Rs. 60 lakh with the annual operational cost totalling around Rs. 20 lakh.

“We do not require fertilisers and pesticides as the vegetables are grown in a controlled environment. We use a polythene sheet to shield the vegetables from ultraviolet rays. The plants grow in a safe and healthy environment and produce vegetables and fruits free of chemicals,” Dhruv Kumar, a farmer engaged in the project, told Hindustan Times.

The crops are grown in cocopeat, a fibre made out of coconut husk, and water is pre-treated with essential nutrients.

“We have installed two reverse osmosis (RO) water plants in our farm. The plant capacity is 2,000 litre/hour. We decided to use RO water for farming to have bountiful production and for that it is mandatory the plants must get the required nutrients and minerals in right proportion,” states Avinash.

Tomatoes growing without the use of soil. Photo Source: Sunil Manikpuri via Facebook

The future of India’s food production, Hydroponics?

More than ever, people across the world are becoming more conscious about what they are consuming and better sensitised to how the products they are consuming are being produced. Demands for safer and healthier foods, free from harmful chemicals, are forcing food companies and researchers to come up with new technologies and methods of growing produce, in particular fruits and vegetables, that are safe and healthy for human consumption.

The method of growing soil-less produce is known as Hydroponics. Indoor farming is nothing new, but many of India’s urban dwellers have taken to home farming and using hydroponics as a good solution to space restrictions and worries regarding the safety of their food.

What’s involved?

In a traditional soil-based system of growing produce, a plant wastes most of its energy developing a huge root system for it has to search far and wide in the soil for its food and water. In soil-less gardening, these are directly available to the plant roots by the nutrient rich water that hydroponics uses, thus saving time and space.

The main ingredient for growing soilless plants is adequate sunlight, which is becoming increasingly easier to replicate. Nowadays, the role of LED lighting is being widely investigated and used for promoting photosynthesis and saving energy and many are adopting it in their home practice.

See this guide to home hydroponics by The Better India: Growing Soil-Less With Hydroponics: An Introduction to Innovative Farming at Home

Artificial light helps this plant to grow indoors. Photo Source: Flickr

What are the benefits?

There are many reported benefits of hydroponic plant cultivation. For the urban dwellers, it requires less water, it maximises space as it allows for vertical farming, it requires little space and can even be carried out on windowsills, balconies, rooftops and backyards, it produces safe and healthy crops, free from harmful pesticides and fertilisers and ensures a clean and hygienic environment for crop growth.

There’s a long list of benefits for commercial farmers also; it can help to overcome temporal (seasonal) and spatial (agroclimatic) problems that can lead to failed crops, it produces bigger yields at a faster rate and it produces better quality crops with maximum nutrients.

And some potential drawbacks…

As with anything, it does not come without its potential drawbacks, most notably its costs. Not everyone will be able to handle the costs that come with hydroponic cultivation, which includes the initial capital cost and the cost to run and it can also be high maintenance as it requires constant supervision and management.

As such, in the case of soilless farming methods, it would appear that the next era of farming would be technological, in the hands of India’s urban residents instead of traditional rural farmers, and carried out in multi-storey towers of food and farming, not on soil but from soilless culture.

If you would like to get in touch with the Haryana project, see the contact details below:

Nature Fit

Farm: Village Panchgaon, Manesar, Haryana

Correspondence: 8786, C-8, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi – 110 070

Phone: +91 97173 33242

Email: rupesh_singal@yahoo.com

Urban Crop Solutions Collaborates With Albert Heijn (Ahold Delhaize) & Bakker Barendrecht

Urban Crop Solutions Collaborates With Albert Heijn (Ahold Delhaize) & Bakker Barendrecht

Climate change, the global lack of arable land and the fact that more and more people are living in cities are a real challenge for the daily supply of fresh and healthy food for retail companies.

As an innovative and progressive retail company Albert Heijn, member of the global retail group Ahold Delhaize, is always seeking to work with partners using the most advanced cultivation methods, for the benefit of their customers. As a major vegetable and fruit supplier for Albert Heijn, Bakker Barendrecht plays a significant role in this process. The past three days Urban Crop Solutions (UCS), a specialist and reference as a global total solution provider in the fast emerging world of indoor vertical farming, teamed up with Albert Heijn and Bakker Barendrecht

Already more than a decade ago Albert Heijn has acknowledged the importance of sustainable cultivation methods. At the same time, their supplier for herbs, Tuinderij Bevelander, has begun to produce chives with hydroponic systems. Nowadays, the customer can still buy these chives produced on water at Albert Heijn. The implementation of this innovative cultivation method is becoming more accessible, due to the increasing technological developments. UCS is playing a key role in making indoor vertical farming systems more accessible. The agtech company develops tailored plant growth installations (PlantFactory), has its own range of standard growth container products (FarmFlex and FarmPro) and has an in-house team of plant biologists which develops plant growth recipes to grow a wide range of crops in these installations.

UCS has joined forces with Albert Heijn and Bakker Barendrecht in order to promote this high-tech method of cultivating. A FarmFlex container was strategically placed in front of the headquarters of Ahold Delhaize in Zaandam (The Netherlands) where the past three days employees could visit this mobile indoor vertical farming system. Global Sales Director, Brecht Stubbe and Chief Technical Officer, Dr. Oscar Navarrete were on-site to provide detailed information.

“The past 3 days were a very intense experience”, explains Brecht Stubbe, responsible for Urban Crop Solutions for this project, “Working together with these well reputed cultivator and retailer group confirms our view that our solutions will definitely be part of the solution to meet with the ambitions of our partners to supply their customers daily with fresh and healthy food.”

IKEA Just Launched An Indoor Hydroponic Garden That Never Stops Growing Food

IKEA Just Launched An Indoor Hydroponic Garden That Never Stops Growing Food

Best news for all you people with green fingers!

From tasty lemon basil to crispy red romaine lettuce - KRYDDA/VÄXER series makes it easy to grow your own indoor garden all year round. You don't need soil, sunlight or even a spot outside! How does it work? Just keep an eye on the water level and that's it.

UAE-based Hydroponics Startup Looks To Raise $4.5 Million To Farm In The Desert

UAE-based Hydroponics Startup Looks To Raise $4.5 Million To Farm In The Desert

June 19, 2017

Pure Harvest has acquired a 3.3-hectare farm site in Nahel, UAE where it intends to establish the nation’s first commercial-scale greenhouse to produce tomatoes.

Jojo Puthuparampil | Contributor

Pure Harvest Smart Farms, a UAE-based agri-tech startup in the field of hydroponics, will soon complete a $4.5 million funding in a seed round to finance its 3.3-hectare farm site in Nahel, it said in a statement.

The firm raised roughly 60% of the round in addition to securing investments from its board, for which it has rejigged the board and made new appointments.

Pure Harvest expects the new appointments to help with technology selection, operational execution, legal structuring, corporate development and strategy as it expands its footprint across the Middle East, it said.

Pure Harvest, co-founded by Sky Kurtz, a former private equity investor based in Silicon Valley, and his Emirati business partner Mahmoud Adi, plans to bring the latest hydroponics farming techniques to the UAE.

Hydroponics farming is the process of growing plants in solutions, rather than soil, allowing for the careful control of the nutrients the plants receive.

Pure Harvest intends to cultivate high-value crops in modern glasshouses using a semi-closed climate controlled growing system that is built to overcome the challenges of year-round production in the littoral areas of the GCC region.

At the 3.3-hectare farm site in Nahel, the firm intends to establish the nation’s first commercial-scale greenhouse to produce tomatoes.

In October, Pure Harvest raised $1.1 million from Abu Dhabi-based Shorooq Investments.

The company’s solution uses over-pressure climate control technology with a hybrid evaporative and mechanical cooling system to maintain optimal indoor climate conditions.

In a market where existing commercial farms are forced to cease vegetable production during the summer period lasting June-October, the startup claims to offer technology that will deliver a tangible food security solution.

Pure Harvest claims to substitute high cost, air-freighted, seasonal imports and instead supply premium quality produce directly to retailers, airlines and hospitality food distributors.

The technology, it says, enables water conservation and carbon dioxide dosing, achieving high productivity for a variety of crops including tomatoes, capsicums, cucumbers, eggplants, and strawberries.

It plans to grow crops year-round in a “natural substrate”. The substrate—or the material chosen by Pure Harvest—will be derived from coconut shavings. It will not use pesticides.

Internet-connected sensors will monitor crops and precision-feed individual plants according to need, while the air will be dosed with CO2 to make the plants grow well.

Other hydroponic farms in the UAE include Elite Agro and Emirates Hydroponics.

These #4 Start-Ups Are Promoting Hydroponics in India

These #4 Start-Ups Are Promoting Hydroponics in India

Hydroponics or growing plants in water or sand, rather than soil, is done using mineral nutrient solutions in a water solvent

Image credit: Pixabay

Feature Writer, Entrepreneur.com

June 8, 2017

You're reading Entrepreneur India, an international franchise of Entrepreneur Media.

Only an expert gardener knows how difficult it can be to grow plants and how much extra care it takes with special attention to soil, fertilizer and light. One can’t get the process right and expect good yields without getting his/her hands dirty. But, to make their work a lot easy and convenient, many start-ups in India are working on hydroponics farming.

Hydroponics or growing plants in water or sand, rather than soil, is done using mineral nutrient solutions in a water solvent.Additionally, this indoor farming technique induces plant growth, making the process 50 per cent faster than growth in soil and the method is cost-effective. Mineral nutrient solutions are used to feed plants in water.

Here’s a list of four start-ups in India that are innovating agriculture methods and leading the way in indoor farming.

Letcetra Agritech

Letcetra Agritech is Goa’s first, indoor hydroponics farm, growing good quality, pesticide-free vegetables. The farm in Goa’s Mapusa is an unused shed and currently, produces over 1.5 to 2 tons of leafy vegetables like various varieties of lettuce and herbs in its 150 sq metre area. The start-up is founded by Ajay Naik, a software engineer-turned-hydroponics farmer. He gave up his IT job to help farmers in the country.

BitMantis Innovations

Bengaluru-based Iot and data analytics start-up BitMantis Innovation with its IoT solution GreenSAGE enables individuals and commercial growers to conveniently grow fresh herbs throughout the year. The GreenSAGE is a micro-edition kit that uses hydroponics methods for efficient use of water and nutrients. It is equipped with two trays to grow micro-greens at one’s own convenience.

Junga FreshnGreen

Agri-tech start-up Junga FreshnGreen has joined hands with InfraCo Asia Development Pte. Ltd. (IAD) this year to develop hydroponics farming methods in India. The project started with the development of a 9.3-hectare hydroponics-based agricultural facility at Junga in Himachal Pradesh’s Shimla district.

Junga FreshnGreen is a joint venture with a leading Netherlands-based Agricultural technology company – Westlandse Project Combinatie BV (WPC) — to set up high-technology farms in India. Their goal is to create a Hydroponics model cultivating farm fresh vegetables that have a predictable quality, having little or no pesticides and unaffected by weather or soil conditions. They will be grown in a protected, greenhouse environment.

Future Farms

Chennai-based Future Farms develops effective and accessible farming kits to facilitate Hydroponics that preserve environment while growing cleaner, fresher and healthier produce. It focuses on being environment friendly through rooftop farming and precision agriculture. The company develops indigenous systems and solutions, made from premium, food grade materials that are efficient and affordable.

Nidhi Singh

A self confessed Bollywood Lover, Travel junkie and Food Evangelist.I like travelling and I believe it is very important to take ones mind off the daily monotony .Read more

Going Indoors To Grow Local

Going Indoors To Grow Local

Alberta company wants to license its hydroponics-aquaponics system to others

Posted Jun. 15th, 2017 by Barbara Duckworth

Nutraponics employees include aquaculturalist Geoff Harrison, left, plant specialist Stephanie Bach and CEO Tanner Stewart. The company grows fresh produce at its facility near Sherwood Park, Alta. | Barbara Duckworth photo

SHERWOOD PARK, Alta. — Providing fresh local produce to Canadians year round could be achieved with a new farming concept that combines horticulture with aquaculture.

NutraPonics, which opened in 2015 near Sherwood Park, is dedicated to supplying the local produce market and supporting local suppliers.

Since last December, it has been selling fresh romaine lettuce, kale, Swiss chard, basil and arugula every week.

The produce is marketed through the Organic Box, a privately owned company in Edmonton that supplies its customers with individually selected orders of locally grown food through online sales and from a store front.

“Everything is marketed as local. We are 32 kilometres from the Organic Box, so that is as local as you can get,” said Stephanie Bach, a plant scientist with the company.

Added chief executive officer Tanner Stewart: “We are hoping to provide less need for products from very far away.”

Stewart, who invested in the company three years ago, is among about 50 private shareholders in the company, which plans to franchise the concept of growing produce indoors in a controlled environment.

“Our model is to not build our own farms and create a massive amount of in-house production,” Stewart said.

“Our business model is to build and license these facilities.”

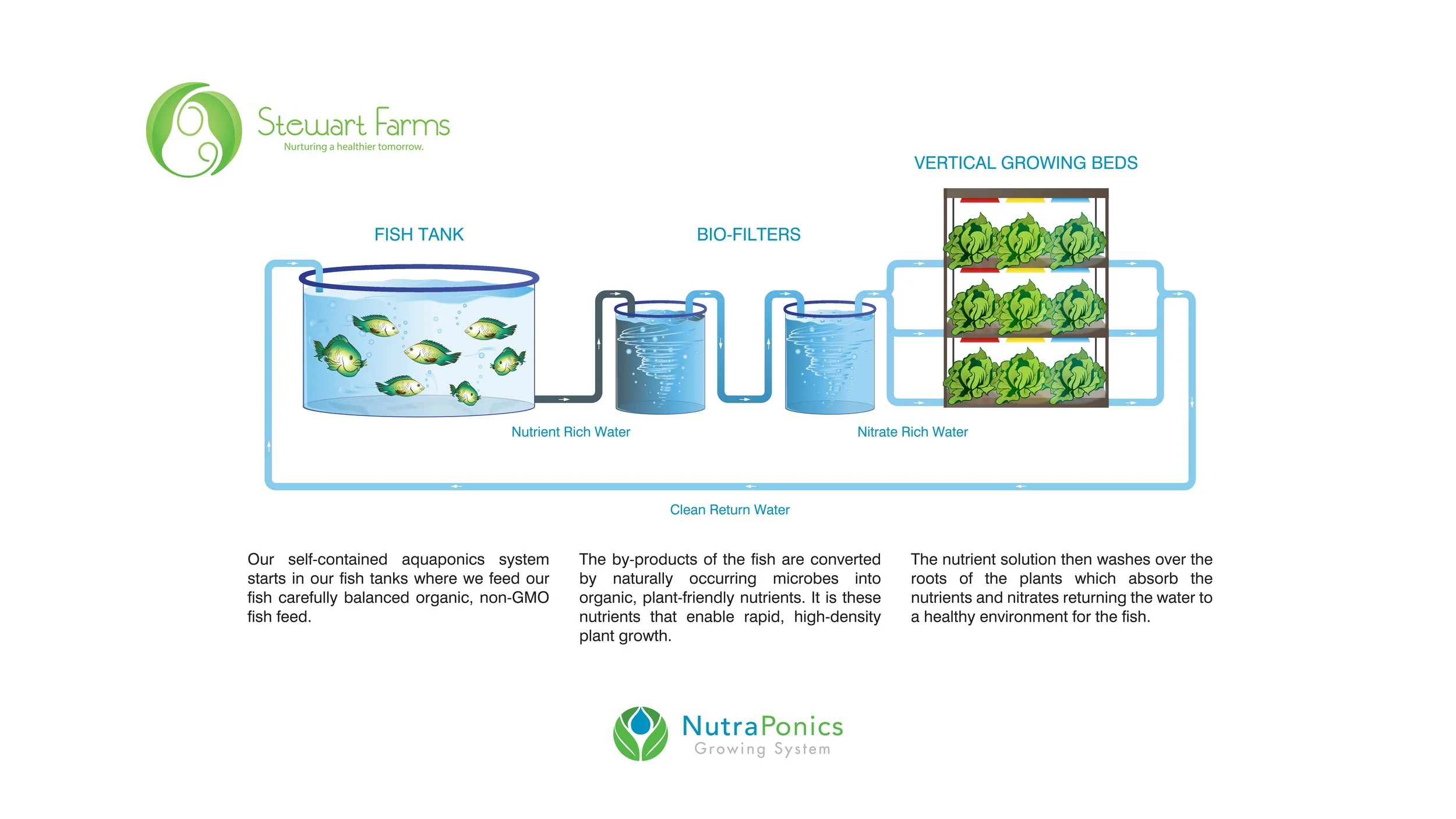

Former CEO Rick Purdy and a company owner started the system. Purdy researched hydroponics to grow food in water and added aquaponics to use byproducts from fish to create a new growing system.

This farm is considered a demonstration facility, where staff can research the best use of the fish, water and plant development.

There are three tanks full of tilapia fish. The nutrient-enriched water from the tanks is delivered to the plants, which are grown in five layers in a controlled atmosphere.

About 1000 sq. metres of growing space are available, where plants are under red and blue LED lights and fed hydroponically.

Under Bach’s supervision, seeds are planted in a special volcanic rock growing medium from Ontario. They sprout within a week and are then transplanted to the main growing rooms. The plants can be harvested within four weeks for same day pickup by clients.

The company employs about 10 people and while each person might have an official job description, the reality is everyone helps with the fish as well as planting and harvesting.

There is no plan at this time to sell the fish.

“The economics of land-based fish farms is fairly fixed,” said Stewart.

“In order to do business, you really have to look at 200 tonnes of production per year to reach economies of scale. This is two tonnes a year.”

This farm sits on 19 acres, but Stewart envisions any empty urban warehouse as a viable growing operation.

NutraPonics is an agriculture company which sells proprietary growing technologies. These technologies utilize symbiotic relationships between plants and fish known as aquaponics to grow nutrient-rich herbs, vegetables and fish in an enclosed, controlled environment. For more information please visit http://www.nutraponics.ca/home

Whitehorse, Yukon, will be the location of the next farm. The goal in the northern community is to grow and sell produce year round at a competitive price with less freight and a longer shelf life.

Stewart also hopes to develop a facility near his hometown in New Brunswick.

The produce is sold at a competitive price. For example, a bundle of romaine lettuce is offered at $6.25 in a 284 gram package.

“You have to be careful in an emerging industry like ours.” Stewart said.

“You really have to make sure you are focused on this as a business, you need to grow your produce at a certain price and you need to make sure your consumers are going to be happy to buy it at that price.”

He estimated that start-up costs are comparable to any new farm and considers this a stable business model with a decent rate of return on investment.

The difference could be a faster turnaround time from construction to the time saleable product is ready.

“Once we get up and running and all the capital costs are done, then we can produce on a consistent basis, week after week, in fairly short order after we turn the building on,” he said.

The Next Big Thing: Hydroponic and Aquaponic Greenhouse Farming

Greenhouse farming is expanding at a rapid rate, using hydroponic and aquaponic methods to grow produce. Many believe it's the next big thing in farming.

Wednesday, June 14th 2017 - by Nathan Edwards

The Next Big Thing: Hydroponic and Aquaponic Greenhouse Farming

MIAMI VALLEY, Ohio (WKEF/WRGT) - Greenhouse farming is expanding at a rapid rate, using hydroponic and aquaponic methods to grow produce.

Many believe it's the next big thing in farming.

Endless rows of carefully grown tomatoes are nurtured at golden fresh farms in Wapakoneta.

"You can see the consistency with the quality and size," VP Paul Mastronardi points out.

99 percent of the tomatoes in this massive greenhouse make it to the grocery store. That's 16 million pounds, enough to give everyone in Ohio and Kentucky a package of tomatoes.

"We are maximizing our yield per square meter," Mastronardi said.

What's the secret? Mastronardi said hydroponic farming.

Water is coursing through the pipes, keeping plants alive

"With the greenhouse environment we have more control over outside factors which helps us," Mastronardi said.

Famers monitor bees living near the plants, use gas to heat the floor on cold days and create sun light when there isn't any.

"One of the major benefits of growing in a greenhouse structure is that the consistency week in and week out is there," Mastronardi said.

The industry is rapidly expanding. In Wilmington, Bright Farms is planning a 10-million-dollar greenhouse, adding 30 jobs.

The hydroponic farm will grow lettuce, tomatoes, herbs and more.

Clinton County Commissioner Kerry Steed said they'll be the source of fresh produce for a hundred-mile radius.

"We're talking Cincinnati, Dayton, Columbus regions in regard to fresh produce," Steed said.

A 2014 USDA study said Ohio already has more than 50 indoor farms. That number is growing.

On a much smaller scale at Oasis Aqua Farm in Beavercreek, Kimball Osborne and his wife Stephanie grow 20 different crops.

"The first thing that you'll see when you look around is there's no dirt," Osborne said.

This is considered aquaponic farming, where fish help the plants thrive.

"We feed the fish and the fish take care of the fertilizer and the plants in turn send the water back to the fish," Osborne said.

They create a sustainable ecosystem. In these tubs herbs and vegetables grow 30 percent faster than a traditional farm.

"I have everything in this greenhouse that I need other than the sun, so as long as the sun doesn't go away I should be good," Osborne said.

The Osborne’s plan to expand as the demand grows, selling both produce and fish directly to locals.

At Golden Fresh Farms, their tomatoes are already sold in most major grocery stores.

Now they're testing peppers, wanting to eventually add 80 acres to their facility.

"The future of the greenhouse industry in the United States is about to take off in the next 5 years," Mastronardi said.

He believes this will replace traditional farming, due to its efficiency, making it the next big thing.

Making A Life Out of Lettuce

Making A Life Out of Lettuce

Controlled environment hydroponic lettuce growing provides an honest living for Jeff Adams and the employees of Circle A Farms in Cumming, Ga.

Jeff Adams started growing lettuce after 20 years of working as a contractor. Photo courtesy of Jeff Adams

Like others with a strong work ethic and an affinity for the outdoors, Jeff Adams enjoys what he does for a living. It’s demanding work to simultaneously grow and sell multiple varieties of lettuce — a job that, for him, doesn’t let up any time of the year. However, it’s worth the time he gets to spend in greenhouses and in the community learning the intricacies of growing and selling hydroponic produce.

A contractor by trade for 20 years, Adams didn’t have any experience with controlled environment agriculture (CEA) before he constructed his first two CropKing greenhouses in 2011 (He has since built two more). He did, however, have a passion for farming. He owned about 30 heads of cattle and grew lettuce in the backyard of his 13-acre Cumming, Ga., home.

Adams became interested in CEA and CropKing’s computer-controlled, hydroponic greenhouses when he read about R & G Farm, a lettuce grower based out of Dublin, Ga., in Hobby Farms magazine (Editor’s note: Read Produce Grower’s story on R & G Farm at bit.ly/2lsRZDe). “I started researching it for about two years, and went and took some classes through CropKing on it and just decided, ‘What the heck?’,” he says. “I think it might fit what we want to do in our passion for farming and growing. And we pulled the trigger. It’s been five years now.”

With a total of eight employees, a growing customer base and fresh, quality lettuce, Adams’ business, Circle A Farms, continues to grow.

Edible Education

Once Adams began growing produce in a greenhouse, it didn’t take long for him to realize that growing hydroponically is much different than growing in the ground.

Through its training materials and information, CropKing has helped Adams make his operation a success. “They have such a wealth of knowledge, and they’ve done it for so long, that, to me, they’re just a viable source that I’d hate to be without,” he says.

Adams' greenhouses control the environment — heating, cooling, air movement, nutrient supplies and carbon dioxide — through computers, he says. Adams has adjusted growth spacing by drilling small holes to accommodate growing baby lettuce.

Using nutrient film technique (NFT) trays, Circle A Farms grows nine varieties of lettuce, Adams says. “We grow bibb, romaine, spring mix, kale, arugula, basil and we do microgreens,” he says. “And there’s a couple other varieties. We do tropicana, frisee. All just leafy greens.”

Selling to local markets and consumers

Most of Circle A Farms’ customer base, which consists of stores and restaurants, are within about a 15-mile radius of the growing operation, Adams says.

Like many other CEA growers, Circle A Farms often markets directly to consumers through avenues such as local farmers markets. In January, it began delivering directly to customers’ homes through its new Farm to Porch program.

To participate in Farm to Porch, area customers find their location listed as a “zone” on circlealettuce.com and place a lettuce order, Adams says. “You either put a cooler out or we can sell you a cooler bag that you leave out, and then it’s delivered right to your porch,” he says.

I think a lot of people come into [CEA] like they’re going to make a lot of money — a get rich quick kind of deal — and that’s not the case, but there is some profitability. — Jeff Adams, Circle A Farms

Because Circle A Lettuce is grown in ideal conditions with computer-controlled nutrition levels, and sold to local markets, it has an approximately three-week shelf life, compared to lettuce that is shipped long distances, which often has a shelf life of only four to five days, Adams says. “It’s a great, wonderful product,” he says. “You just have to educate the consumer why they’re paying a little bit more for the product.”

When it comes to revenue streams for Circle A Farms, enough money comes in to provide Adams and his employees with a steady income, but that’s because of the hard work they put into the operation. “I think a lot of people come into [CEA] like they’re going to make a lot of money — a get rich quick kind of deal — and that’s not the case,” he says. “But there is some profitability.”

Growing Pains

It is often difficult to predict what will happen from one day to the next, Adams says. Tip burn and other problems have arisen that have taught Adams and his employees how to best care for the lettuce.

When production hiccups take a toll on a crop, customers still have the same expectations as when production is going flawlessly, Adams says. “They get used to your consistency and they start thinking you can produce it like a widget, that you can just turn out as many as you can, when still, you have issues and you have problems, and you might lose a crop of bibb or a crop of something here and there,” he says.

Many factors, such as lettuce variety and time of year, determine production cycles, Adams says. Circle A Farms doesn’t track how many cycles it produces in a year because they are constantly changing and rotating. Some lettuces have rotations of 30 days, while others have rotations of 45 to more than 50 days.

“It never stops growing, so you can’t just shut it down and leave,” Adams says. “It’s kind of like having chickens, except with chickens you get a break every six or so many weeks. With this, you never get a break.”

Still, Adams says he finds his work affords him an honest living. He doesn’t mind the extra hours he puts in throughout the week. “If you don’t mind hard work, weekends, nights, whatever — things happen, problems happen, you’ve got to be around — it can be rewarding because the product we’re able to turn out is superior to anything that’s out there

Engineers Use Shipping Containers For New Spin on Ancient Practice, Hydroponics

Engineers Use Shipping Containers For New Spin on Ancient Practice, Hydroponics

By Staff Reports - 6/8/17 6:27 PM

INDIANAPOLIS — Hydroponics — growing crops in water only, without soil — dates back to the first century, in the Roman Empire.

But four millennials working out of a barn just east of Indianapolis are putting a new spin on the old farming technique. And they’re using a surprising space for it.

During an educational outreach mission that took him through South Africa, Chris Moorman came up with a novel idea for refrigerated shipping containers.

Produce — and lots of it — could be grown in them, he surmised after a casual conversation with a local resident that somehow turned to the topic of uses for discarded shipping containers.

After concluding his overseas mission and a five-year tour as a Wall Street stock broker, Moorman decided to build a business on the unusual idea.

An acre’s worth of produce can be harvested from a 40-foot shipping container outfitted with his company’s high-tech system, according to the 30-year-old Bedford native.

These days, hydroponics is most often conducted in a greenhouse, but that involves high construction costs and building permits.

Moorman’s company, Greenfield-based Rubicon Agriculture, offers a self-contained, fully enclosed hydroponics unit, called an AgroBox, for $75,000. A higher-yield model costs $82,000.

Heads of lettuce in Rubicon’s AgroBox mature in less than half the time as those grown outside in a field.

“I’ve seen a lot of hydroponics operations, but I’ve never seen or heard of one using a shipping container,” said Robert Rode, lab manager of Purdue University’s AquaCulture Research Lab.

Rubicon’s founders’ backgrounds are as unique as their ideas. None of them have farmed.

Moorman, who graduated from Purdue University with an economics degree and is Rubicon’s CEO, spent his early career as a commodities trader before discovering his passion for sustainable agriculture during a year-long sojourn through several developing countries.

Moorman’s younger brother, Erik, 26, served as a nuclear engineer in the U.S. Navy. Serving on the USN Newport News, he learned about closed-circuit water systems in agriculture.

Jesse Robbins, 26, who, like the Moorman brothers, is from Bedford, and Pat Burton, 28, a Greenfield native, previously worked with automation technology in manufacturing that they now apply to the growing process. Both graduated from Purdue with electrical engineering degrees.

“We’re an eclectic group, but we all have vital skills we bring to the table,” Moorman said.

Initially, they had difficulty finding financing.

“We were a bunch of guys who never grew anything,” looking for funding to start an agricultural company, Moorman said with a laugh.

Eventually, the founders started the firm with $60,000 from their own pockets.

The company, which launched in July 2015, is approaching profitability, Moorman said.

Built-in Advantages

Rubicon’s system has several advantages, he said. It’s “easily movable with a semitruck and a winch. You can put it anywhere.”Also, because the containers are refrigerated, “they have a great insulation rating,” Moorman said, making temperature control — critical for maximum hydroponics production — easier and more efficient.

An added plus for Rubicon is that it can buy the containers — after they’ve made myriad trips across the globe — for pennies on the dollar.

About 2,500 plants can be placed on each unit’s floor-to-ceiling tiered shelving and, with only a water and electrical hookup, growers can control conditions inside a Rubicon unit with “pinpoint precision,” Moorman said. The key, he added, is a data-collection system that allows growers to monitor conditions for optimal growth.

“If I can’t act on the data, the data is just noise,” Moorman said. “Having our system is all about actionable data.”

Driven by Mitsubishi control components, the system is akin to those used in advanced manufacturing, he said.

Rubicon’s units are outfitted with LED lights and a system that controls light spectrum and wavelength, a climate control unit that tightly monitors and controls oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, and a hydration system that recirculates water with a precise mix of nutrients and a carefully set pH balance. Moorman boasts that Rubicon’s system uses only 10 percent as much water as traditional farming.

“One of the best parts of our system is, it doesn’t require pesticides or herbicides,” Moorman said. “It’s completely organic.”

But hydroponics comes with serious challenges, said Darin Kelly, who operates Good Life Farms in Eminence.

The technique “is technical and not simple,” said Kelly, who grows crops traditionally and through hydroponics. “You’ve got to worry about plumbing, slope, pressure and measuring nutrients. You become a plumber; you become an electrician.”

With Rubicon’s system, zoning can be a concern, too, Moorman admitted. Since this is a new concept, local zoning officials are still working out the regulations.

Rubicon’s system is best suited for predictably growing plants that don’t stretch upward too much or have lots of inedible biomass, like corn. Plants like snap peas, kale, basil, oregano, spinach, cilantro and lettuce are ideal.

Moorman said a head of lettuce grown in the field takes more than 60 days to mature — but only 24 in Rubicon’s unit. By using phased growing, Moorman said, farmers using Rubicon’s system can produce 500 heads of lettuce weekly year-round from a single 320-square-foot container unit.

“For a space that small, that type of production is really super,” Purdue’s Rode said. “It may even be optimistic. But if they can achieve that, it’s very, very good.”

Educational Component

Moorman has been working to get his system in the hands of several Hoosier high schools, including Shortridge High School in Indianapolis, another in southern Indiana, and one in Omaha, Nebraska. He said it’s a great teaching tool.“We’re going to have a generation of farmers that don’t live on farms,” Moorman said.

But the technology can go beyond farming.

It’s the same as that used “to make an intake manifold,” he said. “There’s a real workforce-development part of this.”

He predicted Rubicon’s portable system will also be key in furthering the farm-to-table movement and could help solve the problem of food deserts — neighborhoods, often low-income, that are more than a mile from a grocery store.

“The average American meal travels more than 1,500 miles from farm to plate,” Moorman said. “Of all the produce consumed in the U.S., 50 percent of it is grown in California, where there is a major water shortage. Those aren’t sustainable trends.

“We’re taking something — a shipping container — that has been bringing food to you in a more traditional sense and putting it back to work growing food right in your local neighborhood.”

No Aquaponics

One field Moorman has no interest in is aquaponics, a system not quite as old as hydroponics, but nevertheless one that has been around several centuries. In aquaponics, Rode said, producers have to balance two ecosystems that aren’t always compatible.Aquaponics operations use controlled ponds — often indoors — to raise fish, usually a hardy species like tilapia. The plants draw from the bionutrients in the fish ponds. The upside to aquaponics: Operators can sell both fish and crops. But Rode said establishing conditions that both the fish and crops can thrive in is tough.

“The fish and plants often prefer different pH levels and water temperatures,” he said.

Moorman said there’s plenty to harvest with the more manageable hydroponics. The U.S. hydroponics industry is projected to hit $9 billion by 2020, according to multiple sources. Moorman said Indiana can nab $2 billion of that, pointing out that Indiana and the four surrounding states spend $20 billion on produce annually.

“We think there’s an opportunity for Indiana to be a powerhouse of produce,” Moorman said. “But that opportunity comes with a lot of education. ”

These #4 Start-ups Are Promoting Hydroponics in India

These #4 Start-ups Are Promoting Hydroponics in India

Hydroponics or growing plants in water or sand, rather than soil, is done using mineral nutrient solutions in a water solvent

Image credit: Pixabay

Feature Writer, Entrepreneur.com

JUNE 8, 2017

You're reading Entrepreneur India, an international franchise of Entrepreneur Media.

Only an expert gardener knows how difficult it can be to grow plants and how much extra care it takes with special attention to soil, fertilizer and light. One can’t get the process right and expect good yields without getting his/her hands dirty. But, to make their work a lot easy and convenient, many start-ups in India are working on hydroponics farming.

Hydroponics or growing plants in water or sand, rather than soil, is done using mineral nutrient solutions in a water solvent.Additionally, this indoor farming technique induces plant growth, making the process 50 per cent faster than growth in soil and the method is cost-effective. Mineral nutrient solutions are used to feed plants in water.

Here’s a list of four start-ups in India that are innovating agriculture methods and leading the way in indoor farming.

Letcetra Agritech

Letcetra Agritech is Goa’s first, indoor hydroponics farm, growing good quality, pesticide-free vegetables. The farm in Goa’s Mapusa is an unused shed and currently, produces over 1.5 to 2 tons of leafy vegetables like various varieties of lettuce and herbs in its 150 sq metre area. The start-up is founded by Ajay Naik, a software engineer-turned-hydroponics farmer. He gave up his IT job to help farmers in the country.

BitMantis Innovations

Bengaluru-based Iot and data analytics start-up BitMantis Innovation with its IoT solution GreenSAGE enables individuals and commercial growers to conveniently grow fresh herbs throughout the year. The GreenSAGE is a micro-edition kit that uses hydroponics methods for efficient use of water and nutrients. It is equipped with two trays to grow micro-greens at one’s own convenience.

Junga FreshnGreen

Agri-tech start-up Junga FreshnGreen has joined hands with InfraCo Asia Development Pte. Ltd. (IAD) this year to develop hydroponics farming methods in India. The project started with the development of a 9.3-hectare hydroponics-based agricultural facility at Junga in Himachal Pradesh’s Shimla district.

Junga FreshnGreen is a joint venture with a leading Netherlands-based Agricultural technology company – Westlandse Project Combinatie BV (WPC) — to set up high-technology farms in India. Their goal is to create a Hydroponics model cultivating farm fresh vegetables that have a predictable quality, having little or no pesticides and unaffected by weather or soil conditions. They will be grown in a protected, greenhouse environment.

Future Farms

Chennai-based Future Farms develops effective and accessible farming kits to facilitate Hydroponics that preserve environment while growing cleaner, fresher and healthier produce. It focuses on being environment friendly through rooftop farming and precision agriculture. The company develops indigenous systems and solutions, made from premium, food grade materials that are efficient and affordable.

Future Of Food: How Under 30 Edenworks Is Transforming Urban Agriculture

JUN 1, 2017 @ 03:45 PM

Future Of Food: How Under 30 Edenworks Is Transforming Urban Agriculture

Tim Pierson

Jason Green, 27, and Matt LaRosa, 23, are the CEO and Construction Manager of Edenworks.

When Matt LaRosa joined Edenworks in early 2013, he was a college freshman who still hadn't even picked a major. But when he overheard CEO Jason Green at a pitch competition explain his plan to transform industrial buildings into high-tech farms, he immediately abandoned his own pitch and pitched himself to Green instead. The duo, along with cofounder Ben Silverman, went on to create the self-regulating aquaponic system that now supplies microgreens and fish to Brooklyn and landed them on this year's 30 Under 30 Social Entrepreneurs list.

The Edenworks HQ is not exactly where one would expect to find fresh produce and fish. Located in the Bushwick area of Brooklyn, the company sits atop a metalworking shop belonging to a relative of Green. Their office looks like a typical young startup: all eleven employees crowded in one room with computer screens occupying almost every surface. But upstairs across a narrow walkway is where the magic really happens: an 800 square foot greenhouse, custom built by LaRosa, housing fish tanks, vertically stacked panels of microgreens, and a sanitary packaging unit. Though admittedly cramped, the company says their size has made the team significantly more lithe than larger industrial agriculture operations.

"Being a startup, you have a ton of room to break things and iterate very quickly," LaRosa told Forbes. "We're so nimble with changing our prototypes... we have something different than anywhere else in the entire world."

Currently, about 95% of leafy greens consumed in the US are grown in the desert regions of California and Arizona. Most of these products are grown for mass production and durability in transport, rarely for quality or sustainability. Urban farms have cropped up as way to provide growing metropolises with fresher produce in a way that is better for the environment.

The Edenworks model differentiates itself from other urban farms in that it is a complete, aquaponic ecosystem. Waste from the tilapia fish is used as a natural and potent fertilizer for the microgreens planted on vertically stacked power racks. They have no need for synthetic fertilizers or pesticides that can diminish the nutritional quality of produce.

"The water table is falling every year, there's a huge amount of money invested in pumping water out of the ground and irrigating, and inefficiency in the supply chain where a lot of product gets wasted or left in the field," explained Green, a former bio-engineer and Howard Hughes research fellow. "We eliminate all of that waste."

A common phrase in the office is turning factories into farms instead of farms into factories, and many of their design challenges have been combated by embracing the industrial nature of the location. Indoor farms are often criticized because they can't make use of the natural processes used in traditional farming. But the team has invested in studying ancillary industries to find the lowest cost and highest return methods of mimicking the natural processes, like using custom LED lighting to emulate sunlight.

The research has paid off. In the current iteration, Edenworks is able to harvest, package and reach consumers within 24 hours. By cutting down on transport and prioritizing quality over durability, the greens are also up to 40% more nutrient dense than traditional produce.

For now, their largest barrier is clear: space. With $2.5 million in funding to date, their tiny greenhouse has managed to consistently service the local Whole Foods with two varietals of microgreens. In the winter of 2018 though, they plan to move to a space 40 times the size and simultaneously roll out five additional product lines across the NYC area.

The plans for the new building have been delayed a few times, but with LaRosa graduating NYU last month and joining the team full time, Green is confident they are on track to hit their deadline. The larger facility will be the result of years of planning that will incorporate new technology that will allow them to become even more efficient and competitive in the market.

"What we've developed is a huge amount of automation that will allow us to bring the cost down for local indoor grown product into price parity with California grown product, and that's really disruptive," says Green. "If we want to move the needle on where food comes from in the mass market, it has to be cost competitive. We want to be the cost leader, we want to bring the cost down."

The Greening Of Alaska: Vertical Hydroponic Farming & Alaska Natural Organics Affect The Economy

The Greening Of Alaska: Vertical Hydroponic Farming & Alaska Natural Organics Affect The Economy

Lester Mondrag | June 05, 2017 | 02:38 PM EDT

(Photo : Photo by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images) Spanish Intern Isabel checks Corriander plants in one of the Underground tunnels at 'Growing Underground' in London, England. The former air raid shelters covering 65,000 square feet lie 120 feet under Clapham High street and are home to 'Growing Underground', the UKs first underground farm. The farms produce includes pea shoots, rocket, wasabi mustard, red basil and red amaranth, pink stem radish, garlic chives, fennel and coriander, and supply to restaurants across London including Michelin-starred chef Michel Roux Jr's 'Le Gavroche'.

Alaska is now an agricultural supplier of fresh fruits and garden vegetables that usually grows in the warm areas of California and Mexico. The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Natural Resource Conservation Services supports and funds the farming technique. The 49th state enjoys the funding and is now accelerating its farming industry with additional greenhouses for construction, the greening of Alaska is at hand.

The greening of Alaska has its people feel the excitement of the sustainable farming industry with support from the government; the last seven years saw some 700 greenhouses put up to support the growing demand of agricultural products for domestic consumption and export to other states. Agricultural produce would include fresh tomatoes, eggplants, peppers, tomatillos, Asian greens, kales, and almost anything under the sun, except January when the sun limits its shine. The sun is farthest during the first month of the year and only rises for five hours in the southern front of Alaska.

From February to December, the greening of Alaska continues the application of Hydroponic Farming. The whole eleven months, a huge tunnel becomes a greenery of edible produce for Alaska's economy. The insides of the greenhouse become what scientists call the "hardiness zone" which the USDA classifies as the best environment for growing fruits and vegetables.

The region of ice and snow is now Alaska Greening as local farmers can now grow from corn to melons at will, as the green tunnels are reliably warm. January even extends its farming month when the sun only rises for 5 hours in the southern coast of the state. The far North never experience sunrise and setting of the sun, reports Scientific American.

The two startup companies, Vertical Hydroponic Farming and Alaska Natural Organics impacts the economy and the greening of Alaska. The two companies apply hydroponics farming with only natural nutrient rich mineral water which is a soil and pesticide free technique. The vegetation bask under red and blue LED lights mimicking sunlight, reports Eco Watch.

The growth of indoor farming is booming as its economics is feasible to make the industry flourish, says Head of the US Department of Agriculture's Farm Service Agency, Danny Consenstein. Alaska will have sustainable farming and would be able to export its produce to neighboring provinces of Canada and other states in America.

Vertical Farms Grow Amid Skyscrapers In A Plan to Help Feed China’s Largest City

Vertical Farms Grow Amid Skyscrapers In A Plan to Help Feed China’s Largest City

Laura Brehaut | June 1, 2017 9:39 AM ET

More from Laura Brehaut | @newedist

Sasaki Associates

The hydroponic vertical farm will be dedicated to growing Shanghai staple greens such as kale, lettuce and spinach.

As Shanghai sprawls outward, architecture firm Sasaki Associates has announced plans for a farm that grows upward. The hydroponic vertical farm will be built amid the skyscrapers of China’s largest city. Like most vertical farms in use today, it will be dedicated to growing staple leafy greens such as kale, lettuce and spinach, according to Dezeen.

Space-saving is the aim of the project, Dezeen reports. Sasaki Associates intends the multi-storey farm to act as an alternative to the vast swaths of land — and associated costs — required for traditional agriculture. The project will also incorporate urban farming techniques such as algae farms, floating greenhouses and a seed library.

Vertical farms exist in cities worldwide, providing fresh produce, fish, crabs and other foods to residents in cities such as Anchorage, Berlin, Singapore and Tokyo. Advocates say that vertical farms have a reduced carbon footprint, use fewer pesticides and guzzle less water than traditional farming. Opponents argue that there are many unanswered questions about the practice, and question its economic viability.

Construction of the Shanghai project is expected to start in late 2017 as part of a new development — the Sunqiao Urban Agricultural District. The district will also feature markets, a culinary academy, interactive greenhouses and an education centre for members of the community.

Can Hydroponic Lettuce Save Coal Country?

Story by Otis Gray

Illustration by Jia Sung

5.3.17

Can Hydroponic Lettuce Save Coal Country?

Young people tend to talk about “getting out” of McDowell County, West Virginia. But one radical farmer is bringing life back to his struggling hometown.

This story is a collaboration between Narratively and Hungry, a podcast about the food we eat, the people who make it, and the inspiring stories surrounding food you don’t usuall

* * *

Joel McKinney, 33, is thick and tall, with tattooed arms and a backward baseball cap. There’s a restless demeanor exuding from beneath the militaristic dude-ness he must have picked up during his time in the Navy. He slides open the greenhouse door and a warm draft washes out.

On the north side of the greenhouse are two long rows of eight-foot-tall bright white PVC towers standing at attention. From each PVC pipe explodes scores of violently purple and green heads of lettuce growing vertically up the tube. Each plant sits askew in a little cup fitted into its respective hole in the tower. A steady trickle of electricity and water reverberate in the warm tunnel. These are McKinney’s hydroponic lettuce towers.

“People are so stuck on traditional agriculture, and that’s fine, it’s all great. But I’m not growing out, I’m growing up,” he says. “What I’m doin’ with the towers, it’s not just about hydroponics to me. It’s not just about growing food. To me, this thing embraces change.”

A scene off the main road going through McDowell.

The vibrant, futuristic setup is entirely unexpected in a place like McDowell, and that’s kinda the point for McKinney. McDowell is a remote coal county tucked away in rural West Virginia. Back in the late fifties when coal was booming, McDowell’s population was over 100,000. In 2017 that number has dropped below twenty thousand. It has made headlines over the last decade for its daunting economic hardships, rampant opioid use, and most recently, its overwhelming support for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election. But these headlines fail to cover creative people like McKinney who are responding to those circumstances.

McKinney cradles a deep green head of lettuce between his fingers. The towers each sit atop big black buckets with neat tubes running in between, making the greenhouse look like a room full of computer servers as curated by an obsessive farmer. Each bucket is filled with a nutrient-rich solution – water loaded with natural stuff the plants need to grow. A pump system carries the solution to the top of the tower, where it trickles down inside and is directed to the roots of each plant. The roots dangle into the passing solution and soak it all up. The solution then falls back to the bucket, and is cyclically pumped up to the top again. While the physics of it are simple, McKinney has taken extreme care to make these towers as efficient as possible.

McKinney served in the Navy as a machinist mate, and was honorably discharged after spending 2003 to 2007 aboard the USS Trenton. He went in as an engineer, devouring any manuals he could find and ravenously learning the technology of the ship’s systems. The old-school tech used on the ships – the steam-powered stuff, the electronics – captivated McKinney. He excelled among his peers and became the first E-3 Seaman with the title of qualified firearm supervisor in the 35-year history of the USS Trenton. He deployed to Lebanon, Beirut, facilitated an Israeli evacuation, traveled up and down Latin America, and has seen most of the United States.

Joel McKinney with his hydroponic towers.

Something you’d notice driving through McDowell is that there aren’t a whole lot of people McKinney’s age. You generally see children, and then people who look to be at least forty. This is in large part due to the dramatic decline of jobs over the last fifty years, which has forced adults to flee to urban areas in West Virginia, Ohio, and Kentucky, often sending money back to kids they left in McDowell to be raised by grandparents. The younger generation has seen the county rocked by floods, a recession, and an epidemic of opioid addiction that has deterred those who leave from ever coming back.

“I was forced to adapt,” McKinney says. After the Navy, McKinney went to work for the railroad. During the next seven years, he honed his skills in electrical engineering and operating machinery, but quickly plateaued and wound up unchallenged by the job. He got bored and started drinking heavily – “I have a really addictive personality,” he explains – and got a DUI. The DUI led to a suspension from his railroad job, during which time he wound up back in McDowell helping his mom Linda at their food bank. She had one of these towers lying around so, he did what he does best: He started tinkering.

As the coal industry declined, many people here turned to traditional farming for food and profit, but the runoff from the mines made it tough to grow anything, much less anything healthy. Byproducts like arsenic, selenium, mercury, and compaction often ravage otherwise fertile soil in coal-heavy towns. Even if you do produce enough crop to sell, McDowell is secluded enough that the time and money spent on transportation to a viable market would eat up any profits. Hydroponics provided McKinney a way to farm without using the contaminated water, and the cost is so low that folks in McDowell can afford to buy the resulting produce themselves, cutting out the need for costly transportation.

McKinney calculates that the 440 heads of lettuce he has growing in this roughly twenty-by-five-foot area take up less than one-eighth of the space it would take to grow in the ground and uses ninety percent less water. This means that farmers using McKinney’s systems could bypass tainted water, produce year-round, and multiply their crop by ten times each harvest. All without using pesticides, GMOs, or growth chemicals.

The local public school has become one of McKinney’s accounts and buys lettuce for their lunches. As part of the deal, he gets to teach a raucous group of six-year-olds about hydroponics by installing a tower in one of the classrooms. “Man, working on the railroad is a lot like working with kindergartners. But I’m a structured guy, I work with bullet points – so when you go from the military to working with kids. . .”

He fiddles with a tube feeding into one of the buckets and laughs. “I learn a lot from them. I can’t go in with kids and teach like, tropism and nitrogen cycles and covalent bonding, but you go in with kindergartners and you say, ‘okay well, this is lettuce. This is what lettuce should taste like.’”

“Oh my gosh, he thinks he’s horrible with the kids and he’s fantastic. I tell him he needs to be a teacher,” Kimball Elementary school teacher Sarah Diaz says. “Many of our kids are not exposed to varieties of food,” she adds. “So even simple things like a salad with homegrown vegetables and a homemade dressing, that’s a big deal. They love the flavor. We had so many kids coming away saying ‘I really like vegetables!’ Whereas before, they wouldn’t touch it!”

Diaz says the learning doesn’t stop after kindergarten, it has to become embedded in McDowell’s culture. “If we can get people like Joel to plant a fire in these kids and develop a program that allows them to grow with these systems and grow into it, I can see huge potential for change in the next couple generations.”

The question is whether people in McDowell will embrace the new system. McKinney admits that people in McDowell can be a tough bunch to work with because of their deep traditions and weathered attitudes. Folks in McDowell even describe themselves as “good people, but defensive.” This has a lot to do with decades of their livelihood (coal and other big industries) being outsourced, broken promises from the government, and media outlets that portray their home as a hellish wasteland waiting for politicians to come save them.

McKinney says the people of McDowell constantly surprise him with how on board they are with the hydroponics. “People can be pretty close-minded, but hey, man, I’ve been all over the world, these are very good people here in Appalachia.”

Hydroponic Lettuce Towers in Joel McKinney’s greenhouse.

Hydroponic projects in big cities get most of the media attention, focusing on people growing indoors without a lot of space. But it’s wildly useful in rural areas too. “This is absolutely sustainable here,” McKinney says. “It’s something anybody can do and now I’m training people of all ages how to pick this thing up and run with it.”

“The hydroponics is kinda’ a visual for the concept of change. I wanna bring some change into a rural poverty situation,” McKinney says, nodding his head and looking at a crop. “People will say opportunities don’t exist here. And I say, ‘you’re absolutely right. Create it.’ And that’s what we’re doin’, we’re creating a market.”

His operation is applicable to countless rural economies throughout Appalachia and the rest of the U.S. that are primed with mechanically-minded industry families who are in need of better food and sustainable incomes. Coal will not come back permanently. McKinney knows this, and the folks of McDowell know this too. Transitioning into simple yet futuristic agriculture could revolutionize their narrative.

McKinney shuts the door to the greenhouse. “Look,” he says frankly as he walks back across the cold lot. “I don’t believe that lettuce and strawberries are gonna save McDowell.”

Hydroponics are a beginning. An example that there is more. “Kids here, especially once they hit the junior high age, they just feel like there’s no hope, there’s no chance for change. So as soon as they can they say ‘let’s get out of McDowell.’

“I’m really trying to change that logic as best I can. I don’t think it’ll happen in my generation, but I’m hopin’ to kinda be the spark that initiated some change in this place ’cause I believe it can happen. It’s just gonna take a long time.”

Listen to the extended audio version of this story – featuring Senator Bernie Sanders – on the Hungry podcast. You can subscribe to Hungry on iTunes, Stitcher, your podcast app, or via www.hungryradio.org.

Hydroponic Farm In Lakewood, Colo., Takes Next Step

Hydroponic Farm In Lakewood, Colo., Takes Next Step

Photo courtesy Infinite Harvest |

The room Infinite Harvest grows food in look pink because only red and blue lights are used during photosynthesis.

Before 2002, Tommy Romano's life plans were not necessarily Earthly.

He was at the University of Colorado studing for his master's in aerospace engineering. His thesis was on ways to grow food in space.

But man still has yet to land on Mars, so Romano thought, why not tru this technology on Earth, first?

It took a lot of trial and error and growing food in his basement, including ears of corn. And in January 2015, Infinite Harvest began.

“The traditional ways aren’t fulfilling (the holes left by problems). If we held to the same traditions of farming ... we’d still be riding horses right now. We’re helping it take the next step.”

Infinite Harvest is an indoor hydroponic vertical farm. Currently the farm in Lakewood, Colo., grows 13 microgreens and lettuce. A week ago, when the Denver-metro area was hit with rain, hail and snow, the crops at Infinite Harvest weren't even touched by the elements.

TECHNOLOGY

That's the beauty of growing vegetables in an indoor hydroponic vertical farm — the weather is controlled by technology.

"We don't actively manage a lot," said Nathan Lorne, operations manager. "We really rely on her."

The "her" in this scenario isn't a human, but the greenhouse control system. A box containing machines and wires takes notes on everything that happens in the greenhouse.

The system controls how much water and nutrients the plants get, the temperature, humidity, carbon dioxide levels — anything that can and will affect the plants.

And, if something goes wrong, the control system will send a message to someone so they can come in to fix it.

The room doesn't have any natural lighting, only blue and red spectrum lights are used because that's all the plants need for photosynthesis. They go through day and night cycles.

One you leave the room, everything has a green hue to it because your eyes overcompensate after only seeing two hues of light.

The other lights just waste energy, which is against the goals of Infinite Harvest.

A tech-based farm might sound like it's just wasting energy, but the way the control system is set up, the farm actually pays about six times less than marijuana greenhouses pay in electricity costs each month. When it comes to energy comparisons, marijuana is the best comparison because both grow crops are grown indoors.

Another concern that Lorne said hydroponic farms raise is the amount of CO2 released.

But the system controls the amount of CO2 that is released at all times.

'BEYOND ORGANIC'

Lorne said one of the benefits of having an indoor farm is having complete control over what the plants are exposed to. Even more important for them, though, is what the plants aren't exposed to.

Before going into the farm, a person enters an air cleanser room. Air is circulating and that is where hair nets, hats, shoe covers or specific farm shoes are put on. This helps prevent some unwanted outside elements from getting in. There are traps that attract bugs to keep them from going in, too.

Because there aren't bugs or anything else in the farm, aside from what is planned, Infinite Harvest doesn't have to use genetically modified plants and there is no need to use pesticides.