Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

This Belgian Start-Up Allows Anyone To Become An Urban Farmer

A Belgian start-up is helping people in major cities turn their hand to urban farming. Peas&Love is the brainchild of Jean-Patrick Scheepers, co-founder of Belgium’s biggest cooking school. After the failure of a sustainable farming project near Brussels, he moved into the city itself and started farming on rooftops and in gardens

14 Dec 2020

Senior Writer, Formative Content

A new approach pioneered in Belgium allows anyone to become an urban farmer.

Start-up Peas&Love rents out allotments on rooftops and in unused urban spaces.

The company does all the gardening but members get to harvest the fresh produce.

An app alerts them when crops are ready to pick.

Members share produce and garden space with the community.

A Belgian start-up is helping people in major cities turn their hand to urban farming.

Peas&Love is the brainchild of Jean-Patrick Scheepers, co-founder of Belgium’s biggest cooking school. After the failure of a sustainable farming project near Brussels, he moved into the city itself and started farming on rooftops and in gardens.

“For 20 years, I tried to grow fruit and vegetables in my garden or on my terrace and each year I failed,” he told the audience at the Change Now summit in 2017, the year Peas&Love was launched. “I didn’t have the time and I didn’t have the knowledge.

“My idea was that, if I could have my own personal source of vegetables and fruits that are local, that are seasonal, that are good, that are full of quality, that would exactly fit the description of a potager in French, or a kitchen garden in English, and that would be great.”

Garden of plenty: Crops ready to pick at a Peas&Love urban farm near Paris. Image: Peas&Love

Scheepers started Peas&Love after using vertical growing techniques to overcome his earlier gardening setbacks. It now has three urban farms in Brussels and five in Paris where anyone can rent an allotment for about $40 a month.

All of the farming work is taken care of by the company, and members are alerted by an app when it’s time to harvest the produce. Each 4m square vegetable garden is divided into two halves: one for the sole use of the subscriber and the other to grow crops that will be shared by all members.

Made for sharing: half the allotment is private, the other half is shared.

Community based on sharing

“The motivation of the people who are part of the concept is mainly to renew contact with nature but they don't have the time or the knowledge,” Scheepers says. “You come every week to harvest your own allotment but you don't have to do the work to get it.”

It’s all about creating a community of people who help each other and share values as well as food, he says. It’s a “new approach in urban farming” which has 200 active urban farmers at its first location in Woluwe-Saint-Lambert, in Brussels.

Rooftop agriculture: Peas&Love’s first Brussels urban farm. Image: Peas&Love

The company’s “Peas for all” programme makes 5% of the space on its farms available to educational projects and local associations to help more people reconnect to nature.

Scheepers recently set up the European Urban and Vertical Agriculture Federation to promote the concept and provide a forum to represent urban farmers at a European level, and he has launched an Urban Farm Lab in Istanbul.

Lead photo: Urban farms are becoming common all cross the world. REUTERS/Philippe Wojazer

Making Singapore A Land of Farmers

By 2030, the government has announced that 30 percent of food consumed locally will be locally grown under its “30 by 30” initiative

AUTHOR Malay Mail

December 13, 2020

Kuala Lumpur, Dec. 13 — Singapore is known for its ambition.

This tiny nation (just 700 square kilometers in area, 400 times smaller than Malaysia) is now one of the most competitive economies on Earth.

And yet even by its own standards, it has set a very lofty goal.

By 2030, the government has announced that 30 percent of food consumed locally will be locally grown under its “30 by 30” initiative.

Presently, under 10 percent of the things Singaporeans eat are grown in Singapore. This is extremely low by global standards but again Singapore has a resident population of almost six million, on a small island, with just 400 acres of true farmland in the entire country.

Four hundred acres is the size of a single modest farm in places like the USA and even a mid-scale Malaysian plantation can be double the size.

Yet in Singapore, this is the sum total of all our agricultural land so how on earth are we going to feed millions of people?

The answer is an unprecedented deployment of technology. Vertical farms, advanced hydroponics and growing techniques using nutrients, perfectly calibrated irrigation systems, robotics, and 24/7 monitoring.

The government is also going to work to utilize urban spaces – rooftops, balconies, alleys – on quite an unprecedented scale to achieve greater food self-sufficiency.

While the investment will be high, Covid-19 has proved the benefits are likely to be worth it.

The pandemic showed us that global supply chains can collapse and in times of disruption, governments will prioritize feeding their own populations.

A country with no farmland and agriculture is completely at the mercy of its suppliers.

While Singapore has long been somewhat cognizant of this vulnerability – the government does hold strategic food reserves – this simply isn’t enough and some sort of local agricultural base is needed.

Of course, local sourcing doesn’t just improve our security, it also reduces our carbon footprint and can help ensure what is being consumed is of a very high standard.

So more local farming seems like a clear win all around.

But things are never quite so simple.

As we ramp up our urban farming capacity, won’t we once again be shifting more power and capital to the same tech companies and multinationals that already control so much of our lives?

Recently the government announced that well-known agri-tech company Bayer would launch a large-scale vertical farm in Singapore with a multimillion-dollar investment.

Surely it’s only a matter of time before we have Amazon and Tencent farms. They already supply our homes with all manner of goods, so why not farmed produce? Basically, are we about to see another great leap forward in the dominance of big tech?

Farming has long been the domain of a fairly diverse array of small- and medium-scale producers.

A shift to local production under large-scale corporations will disadvantage many Indonesian and Malaysian farmers who currently supply Singapore.

Previously our purchasing power helped the broader region as we paid high prices for our foodstuff.

And, of course, what of the local population? If there is going to be a shift to local agriculture how can we ensure it creates opportunities for ordinary Singaporeans?

If giant corporations set up automated vertical farms, how will this create employment for us?

The government is clearly aware of the issue and it has been working to increase the number of allotments (plots that give those with no access to a garden a small green space to grow their own fruits and vegetables).

Local sourcing needs to engage local communities yet the resources needed to allow significant local agriculture in Singapore means ordinary citizens will struggle to participate meaningfully in this bid for self-sufficiency.

To reach this 30 percent target sustainably and in a way that benefits us all, we will all need to become urban farmers.

Virtually every home would need a micro-irrigation system, HDB (government housing) corridors would need to overflow with produce and bomb shelters and basements would need to be converted into little hydroponic farms on a staggering scale.

It really could be transformative – bringing together an entire nation to achieve the objective of locally-sourced food.

Working together to sustain the basis of our existence and a return to farming – something the ancestors of most Singaporeans left some time ago.

But for this to happen, as much effort must go into investing in ordinary families and homes as in big corporations.

I for one am already prepared; I’ve bought a few mushroom-growing packs and just acquired a small tomato plant so in a few weeks I look forward to my homegrown pasta sauce.

And in the meantime, I’ll keep waiting for the government to give me the grant to install a giant indoor hydroponic system.

*This is the personal opinion of the columnist.

For any query with respect to this article or any other content requirement, please contact Editor at contentservices@htlive.com

Copyright 2017 Malay Mail Online

INDIA: This Goa Couple Grow Their Veggies & Fish Without Using Soil or Chemicals!

On 185 square meters of greenhouse and rooftop garden, in their house at Dona Paula, Panaji, they produce 120 kilograms of fish a year and grow 3,000 plants consisting of vegetables and fruits

AUTHOR: GUEST CONTRIBUTOR

December 1, 2020

Goa-based Peter Singh is 74-years-old, and his wife Neeno Kaur is 65. They are a power couple, setting an example of how to be self-reliant with food, and at the same time, converting biodegradable waste into something useful.

On 185 square meters of greenhouse and rooftop garden, in their house at Dona Paula, Panaji, they produce 120 kilograms of fish a year and grow 3,000 plants consisting of vegetables and fruits.

For the last four years, they have been practicing aquaponics at home, a combination of aquaculture (raising fish in tanks), with hydroponics (cultivating plants in water).

However, they do with a twist. “We do aquaponics with permaculture,” says Peter Singh, explaining his system to a bunch of enthusiasts earlier this year.

(L) Peter Singh in his air-conditioned greenhouse that has plants which require a cooler climate. (R) Ornamental fish are grown in a fish tank

He adds, “We compost our kitchen and garden waste and use it in our aquaponics. Plants are potted in a layer of gravel, 1/3rd of coco peat, and 2/3rd of compost. So, our plants get compost plus fish waste, which results in a higher yield. I don’t use any chemicals for this, and I am taking care of my waste and my food.”

One may wonder why they are doing it. For them, the answer is simple–they want to eat organic and be sure of how their food is grown.

Moreover, both have a background in agriculture.

“I was studying Mathematics at the Delhi University; the idea was to stay in Delhi, but then we thought of moving back to our farms in Jalandhar, Punjab. We worked on different forms of agriculture, in which different fruit and timber trees were planted, we did intercropping in the orchard of oilseeds and pulses, produced seeds for the national seed corporation, had a dairy farm, did beekeeping and even exported the honey,” explains Singh.

They moved to Goa seven years ago and found it difficult to source organic vegetables. The majority of the vegetables in the state come from the neighboring city of Belgaum in Karnataka. So, they decided to grow their food in this unique way.

“As we have limited space in Goa, we experimented and discovered aquaponics. We downloaded papers from universities, and read about it. And came up with this model,” says Singh.

They opine that they are still experimenting and bring in changes accordingly. As they have the technical know-how and a background in farming, they are quite confident of their system.

How this system works

Peter Singh explaining the model

This system of aquaponics which involves the fish tank, NFT pipes, (Nutrient Film Technique) which are used to grow vegetables, water-pumps, and artificial grow lights, may look complicated. But Singh makes it easier to understand. He has also made a model of this system that can fit in any balcony or even in any corner of the living room.

“This unit of 2 ft by 6 ft and 6 ft high, with artificial lighting of 200 watts uses 250 litres of water and can grow 180 plants. One can grow lettuce, kale, bok choy or any other vegetable. One fish tank can sustain five kilograms of fish mass so that you can have ten fresh-water fish of ½ kg each,” elaborates Singh.

The system works mainly on electricity, water, and fish waste.

Singh explains, “In a fish tank, the fish waste is mainly ammonia. In this system, aerators circulate the water and create a current. The fish waste settles at the bottom, and the pipes take this waste into the bio-filter, which breaks the ammonia into nitrates and nitrites for plants to use.”

The water gets further filtered and goes back to the fish. It also has aeroponic towers which work as the nursery of plants. It is also a space-saving system as it is vertical.

“Because of heavy nitrogen, green vegetables grow very well. We have lettuce, bok choy, and celery. Also, this system uses 10 percent of the water used in traditional soil-based farming, as water is constantly getting re-used. The only loss is in the evaporation. There’s no need of watering, no weeding, one only has to feed the fish twice a day,” says Neeno Kaur.

The entire system has three fish tanks on the ground floor. One is of 3,000 litres of water; second is 1,500 litres, and the third is 4,000 litres. They raise three types of fresh-water fish—rohu, catla, and chonak or sea bass. If one does not eat fish, Singh suggests using ornamental fish.

The rooftop garden

On their roof, they have a greenhouse of 12ft by 24ft, which has 2,000 plants. The greenhouse in the back garden is 6 ft by 16 ft and has 500 plants. A roof-top garden has 25 fruit trees, 300 onions, and an assortment of chillies, lemons, tomatoes, aloe, chives, creepers like ivy gourd, bottle gourd, cucumber, bitter gourd, ladyfinger, brinjal.

Along a boundary on the ground floor, they have mango, banana, and papaya. They also have an air-conditioned tunnel of 8 ft by 12 ft in their greenhouse, with 1,000 plants of lettuce, kale, bok choy, basil, parsley, cabbage, and broccoli. For the whole system, they spend around Rs 14,000 per month.

The aquaponics system doesn’t require cleaning of water as the water gets filtered in the process. And all the fittings are made by Singh himself. He has also part-time workers for about six hours a day. He adds, “We spend Rs 6,000 on electricity, Rs 4,000 on feeding the fish, and another Rs 4,000 on labour.”

They won the first prize for Most Innovative Stall at the Aqua Goa Mega Fish Festival 2020 held in February.

Agriculture expert from Goa, Miguel Braganza opines, “Peter Singh’s aquaponics is good for those who can afford it as the basic cost of the unit is Rs 30,000. Also, it is ideal for those who eat salads and continental cuisine.”

Regarding the cost, Singh states that it is high “because we pump water from the ground floor to the greenhouse on the roof. If it is on the same floor, this is much lower.”

They also have plans for solar panels and making fish feed at home to be self-sustainable. He adds, “If we automate the system, and put in solar power, then costing will go down substantially. We are also working on growing feed for fish. So our whole system becomes self-dependent.”

However, they are also trying to monetise from this system, by conducting two-day training programmes priced at Rs 5,000. Singh adds, “We also custom design and help set up aquaponics systems, of any scale, from small home systems to commercial systems, charging 10 per cent of the capital cost for the design.”

(L) Bok Choi grown in aeroponic towers. (R) Gourds grown on the roof.

Recently, they started selling these vegetables from their home. A basket contains two bunches of lettuce, a baby bok choy, three sticks of celery, sprigs of parsley, basil, and a small bunch of mint, priced at Rs 100. They will also add kale and Swiss chard to it. From next month, their air-conditioned model will produce about 300 packs of greens a month at Rs 120 each.

Singh and Kaur are hopeful that more people will learn from this system and eat healthy food as it is the need of the hour.

He concludes, “This method is independent of the weather, rain, hail, and sun; it is protected from predators and is the future of agriculture. It doesn’t need land, soil, or chemicals, and produces vegetables and fish wherever you are.”

Also Read: Experts Answer: Can a Hydroponics Farm Be a Good Business? Here’s How!

This shows that aquaponics could be next best thing in agriculture due to urbanisation and loss of agricultural land. It is estimated that the market of aquaponics will grow with the awareness to eat healthy food.

According to a report by Assocham and Ernst & Young, organic products market in India have been growing at a CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) of 25 percent, expected to touch ₹10,000-₹12,000 crore by 2020 from the current market size of ₹ 4,000 crore. As aquaponics is a part of the organic market, the future looks bright for this new-age form of agriculture.

During the current nationwide lockdown to tackle COVID-19, Peter Singh is selling their produce once a week from their home by maintaining social distancing. He says, “We slowed down the sale of our produce in the first week, and worked out a weekly production schedule, which includes a weekly harvest and transplantation. This means we will be able to supply every week all year round.”

Lead photo: Peter Singh is 74, and his wife Neeno Kaur is 65. Together, they grow 3,000 plants on just 185 sqm by a method that’s independent of the rain, hail, and sun!

(Written by Arti Das and Edited by Shruti Singhal)

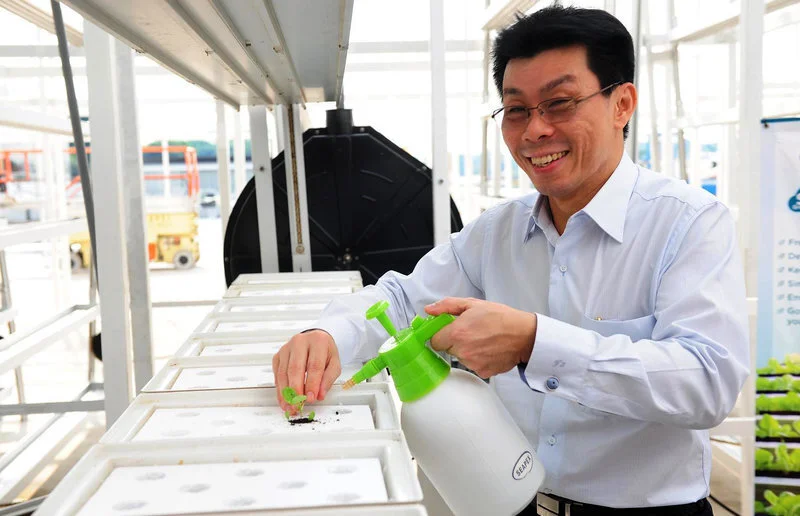

Sky-High Vegetables: Vertical Farming Sprouts In Singapore

Entrepreneur Jack Ng says he can produce five times as many vegetables as regular farming looking up instead of out. Half a ton of his Sky Greens bok choy and Chinese cabbages, grown inside 120 slender 30-foot towers, are already finding their way into Singapore's grocery stores

November 9, 2012

Singapore is taking local farming to the next level, literally, with the opening of its first commercial vertical farm.

Entrepreneur Jack Ng says he can produce five times as many vegetables as regular farming looking up instead of out. Half a ton of his Sky Greens bok choy and Chinese cabbages, grown inside 120 slender 30-foot towers, are already finding their way into Singapore's grocery stores.

The idea behind vertical farming is simple: Think of skyscrapers with vegetables climbing along the windows. Or a library-sized greenhouse with racks of cascading vegetables instead of books.

Ng's technology is called "A-Go-Gro," and it looks a lot like a 30-foot tall Ferris wheel for plants. Trays of Chinese vegetables are stacked inside an aluminum A-frame, and a belt rotates them so that the plants receive equal light, good airflow, and irrigation. The whole system has a footprint of only about 60 square feet or the size of an average bathroom.

Troughs of bok choy stack up vertically at the 30-feet urban farm in Singapore. The veggies rotate along the A-frame to ensure they receive even light. Courtesy of MNDSingapore.

Advocates, whose ranks are growing in cities from New York City to Sweden, say vertical farming has a handful of advantages over other forms of urban horticulture. More plants can squeeze into tight city spaces, and fresh produce can grow right next to grocery stores, potentially reducing transportation costs, carbon dioxide emissions, and risk of spoilage. Plus, most vertical farms are indoors, so plants are sheltered from shifting weather and damaging pests.

But is vertical farming just a design fad, or could it be the next frontier of urban agriculture? That depends on your angle — and location.

Implementing these "farmscrapers" on a commercial scale has been challenging, and making them economical has been almost impossible.

It's still up for debate whether vertical farms are more efficient at producing food than traditional greenhouses, says Gene Giacomelli, a plant scientist at the University of Arizona, who directs their the Controlled Environment Agriculture Center.

The limiting factor is light. The total food produced depends on the amount of light reaching plants. Although vertical farms can hold more plants, they still receive just about the same quantity of sunlight as horizontal greenhouses.

"The plants have to share the existing light, and they just grow more slowly," Giacomelli tells The Salt. "You can't amplify the sun."

For American cities, like New York and Chicago, Giacomelli thinks putting plain-old greenhouses on rooftops could be just as efficient as vertical farms – and a lot easier to implement.

In fact, two companies are already working on that approach. Gotham Greens is producing pesticide-free lettuce and basil for restaurants and retailers from rooftop greenhouses in Brooklyn, while Lufa Farms grows 23 veggie varieties in a 31,000-foot greenhouse atop a Montreal office building.

But for the island of Singapore, where real estate is a premium, vertical farming might be the most viable option. "Singapore could be a special case, where land value is so exceptionally high, that you have no choice but to go vertically," Giacomelli says.

An illustration of the 177-feet vertical farm by Plantagon currently in the works for Linkoping, Sweden.

The Sky Greens vegetables are "flying off the shelves," reports Channel NewsAsia — perhaps because the vertical veggies are fresher than most available in Singapore, which imports most of its produce from China, Malaysia, and the U.S. They do, however, cost about 5 to 10 percent more than regular greens.

"The prices are still reasonable and the vegetables are very fresh and very crispy," Rolasind Tan, a consumer, told Channel NewsAsia. "Sometimes, with imported food, you don't know what happens at farms there."

Lead photo: Senior Minister of State Lee Yi Shyan transplants some leafy green seedlings at the grand opening of Singapore's first commercial vertical farm. Courtesy of MNDSingapore.

PODCAST: Learn About Urban Farming And The Technologies Fueling This Industry

We also talk about the brief history of hydroponics

Joe Swartz & Nick Greens | 11/27/2020

Learn about Urban Farming and the technologies fueling this industry. We also talk about the brief history of hydroponics.

Our new podcast called Polygreens Podcast with Joe Swartz from AmHydro and Nick Greens from Nick Greens Grow Team brings agriculture and technology together in educational episodes. This podcast is about hydroponics, greenhouse, urban farming, vertical indoor farming, and much more.

Chicago Proposed Home of Second Second Chances Farm

Garfield Produce, located in the East Garfield Park area in Chicago, is working together with Second Chances Farm to establish the Second Chances Farm Chicago in the Windy City

Garfield Produce, located in the East Garfield Park area in Chicago, is working together with Second Chances Farm to establish the Second Chances Farm Chicago in the Windy City. Garfield Produce is an indoor vertical farm and a licensed wholesale food establishment whose mission, values, and passion closely match ours.

On October 1st and 2nd, Garfield Produce’s co-founders, Mark and Judy Thomas visited Second Chances Farm in Wilmington after hearing about us during an Opportunity Zone seminar in Chicago earlier this summer. They had previously reached out to Ajit to open discussions about expanding the Second Chances Farm model to Chicago and invited him to visit Garfield Produce.

On October 21st and 22nd, Ajit visited Garfield Produce and toured vacant buildings in Opportunity Zones in Chicago. After discovering a strong connection to second chances for both people and neighborhoods, Ajit and Thomas’s pledged to continue the conversation.

Mark and Judy

Mark Thomas spent several days between November 8th and 13th at Second Chances Farm in Wilmington to further discuss the possibilities. He toured the facilities, met the returning citizens, engaged with the management team, and crunched some numbers. Both Ajit and Mark shook hands-on making the idea of establishing a Second Chances Farm in Chicago a reality in 2021-2022.

Mark, a graduate of an Ivy League college with an MBA and a CPA, was a top executive at the Tribune Company in Chicago for most of his career. He and his wife, Judy, a top corporate attorney, lived in the affluent western suburbs of Chicago. To get to work, they had to drive through the under-resourced areas on the west and south sides of the city, many of which still had the ruins of burned-out buildings from the Martin Luther King riots decades earlier.

Judy Thomas, co-founder, Garfield Produce

“I’d drive right through these impoverished landscapes and never give it a second thought,” says Mark. “But the workforce under my direction changed drastically when the Labor Union took over. Our established workforce was primarily older white males who were Italian, Croatian, and Irish. Suddenly, they were asked to manage a workforce that was around 22 years old, from the east and south sides of Chicago, mostly black and half female. This was when I became keenly aware of the problems that exist in inner-city areas of the United States.”

Mark remembers telling his wife the stories he’d heard during the day, and the shocking experiences he’d had. One employee, he says, shot another employee in the break room because they were from rival gangs.

“So, I said, Judy, it would be great if we could ever get to the point that we could create a small company so that we could hire people who lived in these tough areas,” says Mark. After Mark and Judy retired, that’s exactly what they did.

“We had done some volunteer work at an organization called, ‘Breakthrough Urban Ministries,’ which is in Garfield Park, a very tough area about 30 miles west of downtown Chicago,” Mark says. “It started out as a men’s shelter, then moved to a woman’s shelter, and then a flex area where teenagers could come, and then they started preschool programs. Our biggest frustration was that people would emerge from our job readiness programs, only to find there were no jobs. White flight had taken all the jobs and businesses away.”

In 2013, after having done extensive research and attending seminars about indoor vertical farms, Mark and Judy established Garfield Produce.

“We have a lot of experience with growing produce hydroponically, and a very strong brand in the Chicago area,” says Mark. “We look forward to finding a way we can combine our strengths with Second Chances Farm’s to continue to serve the struggling neighborhoods of Chicago by providing both jobs and healthy, nutritious foods.”

For more information:

Second Chances Farm

www.secondchancesfarm.com

16 Nov 2020

Small Urban Farms, An Oasis For Underserved U.S. Neighbourhoods

Thus the children and their families get a sense that food comes from the soil. This is not so obvious a connection in Ward 8. In this corner of the capital of the US, there is one full-service grocery store for 80,000 people, and access to something as basic as fresh vegetables is limited

October 30, 2020

Adrian Higgins

THE WASHINGTON POST – I ate the last of the season’s potatoes the other day, and it’s not a bad harvest achievement when you consider I dug the lot in July from a bed no more than 15 feet long. I’ve eaten many meals over the summer where the bulk of my plate has come straight from my small community garden plot in the city.

It is amazing how much you can grow in a small space if the soil is good and you stay on top of tasks such as watering and weeding. But even in a pandemic-driven planting year full of homegrown potatoes, beans and carrots, you have to face reality. If you relied on most urban veggie plots alone to feed yourself, never mind a large family, you’d be forever tightening your belt.

This is why I’ve had my doubts about whether urban agriculture can meet the challenge where it is most needed – in poorer, food-insecure neighbourhoods. Rosie Williams is in charge of such a garden, in an expansive side lot of the National Children’s Center, an early-learning and educational development provider in Southeast Washington, in the United States (US).

The garden packs a lot in. There are almost 70 raised planter beds, each four by eight feet and filled with deep, rich soil. That’s a lot of growing area; the beds generate bushels of edible plants for most of the year.

A shed houses tools, a single beehive is active, a few fruit trees ring the area, and one side is devoted to little benches for little people. The centre, which normally houses classes for 188 children up to age five, has been closed because of the pandemic, though a limited re-opening is in the works.

Teacher and garden coordinator Williams showed me cool-season veggies growing in the fall, young plants of kale, collards, cauliflower, broccoli and red cabbage. In other planters, mature plants are seeing out the season in robust vigour. The most obvious is a single pepper plant – now taller than Williams – whose leaves hide unripe green chillies that hang like ornaments. This is a mighty hot pepper from Trinidad named Scorpion, she said, and I have no doubt that it has a sting in its tail.

Nearby, a Japanese eggplant is full of purple streaked fruit. Along another path, Williams stopped to lift a wayward cherry tomato vine and places it back in its bed. “I don’t like to step on my babies,” she said.

Elsewhere, wizened sunflowers have had their day. “We bring the kids out, we show them how to plant seeds, what the plants need,” she said. “It’s getting folks exposed to the garden.” Food from the garden is used in the centre’s kitchen.

Thus the children and their families get a sense that food comes from the soil. This is not so obvious a connection in Ward 8. In this corner of the capital of the US, there is one full-service grocery store for 80,000 people, and access to something as basic as fresh vegetables is limited.

“We have a lack of grocery stores,” said Jahni Threatt, the Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) programme Market Manager for the non-profit Building Bridges Across the River. “In Wards 7 and 8, we have three grocery stores.” Residents eat from fast-food chains or out of convenience stores. “The food that’s available isn’t necessarily healthy,” she said. Under the CSAs, growers provide direct weekly harvests to subscribers.

The Baby Bloomers Urban Farm that Williams coordinates at the National Children’s Center is one of seven in a network of city farms east of the Anacostia River, including a one-acre farm run by Threatt’s organisation at THEARC, the arts, education and social services campus at 1901 Mississippi Ave.

This one farm produced as much as 1,600 pounds of food this year, but to provision its CSA programme, the Building Bridges group turns to an additional 10 farms within 50 miles of the city, most of them Black-owned, said Scott Kratz, vice president.

The CSA runs three seasons of subscriptions, and bags are picked up on Saturdays at THEARC. The spring season was cancelled because of the pandemic, but the summer and fall ones have been heavily subscribed and will provide food for over 400 families this year. The season has also been extended, from the end of this month to the end of next. Lower-income subscribers get a reduced rate, and families on assistance get the food free, Kratz said.

This is heartening, because the pandemic has hit the city’s poorest wards the hardest. Many residents have underlying health issues related in part to their diet, and many are front-line workers or rely on the gig economy, putting them at greater risk of contracting the novel coronavirus, Kratz said.

Ward 8, which is 92 per cent Black, so far has the highest number of virus deaths in the district, with 127, according to city data. Ward 3, 81 per cent White, had 34 for the same period.

“We need to make sure that the programming we have is coming through the lens of equity and making sure the access people need is available to everybody in the community,” said Building Bridges Farm Director Dominic Hosack. I am rethinking my sense that mini-farms in the city are of limited value. They are, rather, a key portal into a larger infrastructure of food-security efforts. Beyond their utility, they are places of deep reconnection, to the soil, to food and to communities. In the food deserts of big-city America, they are the oases.

GARDENING TIP

Whiteflies are tenacious pests of certain houseplants and should be tackled, preferably before bringing plants indoors for the season. A vacuum cleaner is an effective way of dealing with them without using pesticides. Repeat as needed.

Lead photo: Garden coordinator Rosie Williams checks a pepper plant at the National Children’s Center urban farm in Washington. PHOTO: THE WASHINGTON POST

US: MAINE - Planning Board Signals Support For Vertical Greenhouse/Parking Garage In Downtown Westbrook

The $60 million project is a collaboration between the city and developers that would see the Mechanic Street parking lot downtown turned into a free parking garage, topped with over 50 apartments and a Vertical Harvest farm along the structure’s side

The Vertical Harvest Project Will Go

To The Planning Board For Approval In November

AMERICAN JOURNAL

BY CHANCE VILES

The Westbrook Planning Board will vote Nov. 3 on a proposed $60 million combination greenhouse, apartment complex and parking garage. Courtesy

WESTBROOK— Planning Board members spoke in favor of a multi-use parking garage and vertical greenhouse at a public hearing Oct. 20.

The $60 million project is a collaboration between the city and developers that would see the Mechanic Street parking lot downtown turned into a free parking garage, topped with over 50 apartments and a Vertical Harvest farm along the structure’s side.

A rendering of what the view would be looking southwest from Main Street. Courtesy

“I love this project,” Ward 2 member Jason Frazier said. “It has jobs, parking, housing. It’s the perfect project.”

RELATED

Read more about the Vertical Harvest

The greenhouse would produce about 1 million pounds of food per year and bring in 56 full-time jobs with a focus on providing careers for people with disabilities.

“This is the equivalent of 40 acres worth of food, using 90% less land and water,” developer Nona Yehia said. “We recirculate all of the water we use in the greenhouse. … We aim for our food to be sold and consumed within the state of Maine and from farm-to-fork in less than 24 hours.”

The Planning Board members, on the right, look at the first-floor ground plan at their public hearing Oct. 20. Courtesy photo

The garage will be maintained by the developers, while city residents will still have access to over 400 free parking spaces.

Advertisement

According to Economic Development Director Dan Stevenson, they are confident the greenhouse will be successful, though developers did say that if need be, it could be turned into some other workspace.

“In my career, this is one of the strongest business models I have seen,” Economic Development Director Daniel Stevenson said.

RELATED

Read more about the whole project

“I am thrilled,” Ward 4 member Robin Tannenbaum said. “We are touching a lot of exciting areas and contributing to densification. To set the bar high, where there is still room, I’d like to see more development of the design to let the building sing.”

“Coming from the other side of the river into Main Street and into the downtown, that building is going to tower over all of these other, so why not?” Board Chairperson Rene Daniels said. “It would make it pop, it would be outstanding,”

The city will be paying $15 million for the parking garage through an agreement using tax revenue generated from the project, Stevenson said, meaning there will be no direct impact on taxpayers. Developers will take on $40 million of the cost.

“It’s been a goal of ours for a while to start expanding vertically downtown, and this meets that,” Ward 5 member Ed Reidman said.

The Planning Board will vote on the project Nov. 3.

A rendering of the building. Some Board members called for a more lively facade for the apartments on the top floor. Courtesy

Developers say there will be space outdoors with vegetation for some outdoor opportunities, as well as common spaces within the building for residents. Courtesy

AUSTRALIA: City Farming On Rise As COVID-19 Makes People Rethink How They Source Their Food

Urban farmer Rachel Rubenstein thinks the coronavirus pandemic, which has shut down major cities, state and international borders, is a chance to rethink where we get our food from. And growing good food in anything from local car parks, median strips and rooftops, to golf courses and even public parks are just some of the ideas she and her city farming friends are throwing around

By Jess Davis and Marty McCarthy

10-24-20

Urban farmer Rachel Rubenstein thinks the coronavirus pandemic, which has shut down major cities, state and international borders, is a chance to rethink where we get our food from.

And growing good food in anything from local car parks, median strips and rooftops, to golf courses and even public parks are just some of the ideas she and her city farming friends are throwing around.

"I think that having food grown close to home is super important, because we have seen a lack of access to fresh food with the bushfires and then COVID," Ms Rubenstein said.

An urban farm in East Brunswick in Melbourne is seeing a surge in demand for locally grown food by those stuck in lockdown.(ABC Regional)

In Melbourne's inner-northern suburb of East Brunswick, she's growing fresh organic produce such as carrots, radishes, spinach, broccoli, and citrus for Ceres — a not-for-profit community-run environment park and farm.

Ceres has seen demand for its food boxes double since the pandemic began, as lockdowns forced people to shop more locally than ever before.

"Everything that I grow here on the farm is harvested straight away and goes straight to the grocery and the cafe on site," Ms Rubenstein said.

"Just seeing how much I can grow in 250 square metres says something about how we can utilise space better in the city."

Ceres grows vegetables across two sites in the inner city, but it's not enough to fill demand with produce sourced from elsewhere to help fill the gap.

Ceres urban farm in Brunswick near the Melbourne CBD has seen demand for their produce triple since the pandemic started.(ABC Regional: Jess Davis)

Space constraints

Farms like this are a rare sight in Australian cities, with space a major constraint.

Calls to take existing green spaces, such as public parks and golf courses, and adapt them to support things like agriculture are growing in urban centres.

Nick Verginis recently started a social media group called 'Community to Unlock Northcote Golf Course' in a bid to get his local fairway converted into a public park with possible room for agriculture too.

The golf club is across the river from Ceres.

"In lockdown people have been really hungry to get in touch with nature, using whatever space they have on their balconies or in their small gardens to grow their own produce," he said.

"This [fairway] obviously would be a natural place to expand that [farm], so some local residents could have access to a plot of land."

Nick Verginis, with his son Teddy, started the Facebook group Community to Unlock Northcote Golf Course in the hope it could be used as a public space and potentially as a farm.(ABC Regional: Jess Davis)

Farming on the fringe

Converting sections of green spaces into farmland to create a local food bowl is already a reality in Western Sydney Parklands in New South Wales.

Thou Chheav learnt to farm 24 years ago after she moved from Cambodia. She now runs the family's Sun Fresh Farms with her daughter, Meng Sun.(ABC Regional: Ben Deacon)

Five per cent of the 264-hectare park has been set aside for urban agriculture and 16 farms are already operating on it, selling at the farmgate or across Sydney.

Western Sydney Parklands is one of the largest urban parks in Australia — almost the same size as Sydney Harbour — and is one of the biggest urban farming projects in the country.

Sun Fresh Farms, run by Meng Sun and her mother Thou Chheav, has been leasing land off the Parkland for nine years to grow cucumbers, strawberries, zucchini, cherry tomatoes, and broad beans.

Ms Sun said, even before the pandemic, the popularity of sourcing food from peri-urban farms like her family's was taking off.

"All the locals come out on the weekends. It's providing food for the local community and also it gives them a better understanding of where food and vegetables come from," she said.

Unlike produce sold at larger supermarkets that was often picked before it ripened, Ms Sun said being able to buy fresh vine-ripe produce appealed to customers.

"We like to pick fresh and sell direct to the customers. Cut the middleman out so there's not much heavy lifting involved, it is just straight to the farm gate," she said.

There are 16 urban farms operating in the Western Sydney Parklands, but there are plans to increase that number.(ABC Regional: Ben Deacon)

Suellen Fitzgerald, the chief executive of Greater Sydney Parklands, said they were currently accepting applications for new farming projects so that the precinct could expand its food production.

"Many of our farmers have roadside stalls and during the pandemic have reported an up-swing in customers, with the community choosing to shop locally over traditional supermarkets," Ms Fitzgerald said.

"Urban farming is a rising food phenomenon and people are increasingly interested in learning about where their food comes from."

Suring up food supply

Rachel Carey, a lecturer in food systems at the University of Melbourne, said cities should increase their urban farming capacity as an "insurance policy" in the event of future natural disasters or pandemics that disrupt supply chains.

"Obviously urban agriculture is a much smaller part of our food supply system, but I think it does have an important role in future," Dr Carey said.

"If we can keep some of this food production locally it acts as a bit of a buffer or an insurance policy against those future shocks and stresses."

Food systems lecturer Rachel Carey says urban farming has an important role to play in our future.(ABC Regional: Jess Davis)

Dr Carey said cities were more conducive to agriculture than most people realised.

Europe's largest urban farm opened in Paris during the COVID-19 pandemic.(Supplied: Nature Urbaine)

"Cities have access to really important waste streams, and also food waste that can be converted into compost and used back on farms," she said.

"If we can keep some urban food production close by it enables us to develop what we call circular food economies, where we are taking those waste products and we're reutilizing them back in food production to keep those important nutrients in the food supply."

The other benefit was financial.

Dr Carey said buying food from local farmers helped to "keep that money circulating within our own economy rather than going outside to other areas".

She believed Australian towns and cities should also consider the United Kingdom's food allotment system, where local governments or town councils rented small parcels of land to individuals for them to grow their own crops on.

Major European cities such as Paris have also embraced urban farming amid the pandemic — the largest rooftop farm in Europe opened there in July.

The farm, which spans 4,000 square metres atop the Paris Exhibition Centre, supports a commercial operation as well as leases out small plots to locals who want to grow their own food.

There are plans to increase it to 14,000 square metres, almost the size of two football fields, and house 20 market gardeners.

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen a surge in people growing their own crops, making their own bread, and even cooking more at home.(ABC Regional: Marty McCarthy)

From converting sections of golf courses or public parks into small farms, or median strips, car parks or rooftops, Dr Carey said the pandemic had shown the time was ripe to reconsider our urban food production methods.

"I see COVID-19 is a transformational moment that is going to lead to some rethinking about the way that we use our spaces in urban areas and in the city," she said.

"So cities around the world are starting to look more to urban agriculture not just in terms of city soil-based farms, but also non-soil-based farms such as vertical farms and intensive glasshouse farming."

City golf courses are being identified as potential sites for small urban farming plots.(ABC Regional: Jess Davis)

Lead photo: Urban farmer Rachel Rubenstein on a farm in East Brunswick, not far from the Melbourne CBD.(ABC Regional: Marty McCarthy)

Related Stories

Food suburbs: Urban farms in every neighbourhood creates close communities

Meet the farmers with the plan to create the nation's largest urban farm network

Urban farms feel the burn as climate change, water restrictions bite

Navotas City Launches Philippines' Tallest Vertical Farm

The vertical farm is equipped with state-of-the-art technology that increases vegetable yield by a factor of 100, two times more than other farms

October 24, 2020

By DANNY PATA

National Capital Region's Navotas City Council, together with the Boy Scout of the Philippines (BSP) and Good Greens & Co., unveiled on Saturday the tallest aeroponic vertical farm in the country.

Text and photos by Danny Pata

According to the city council, the four-tower farm standing on a 300-square-meter area in Tanza resettlement community."

The aim is to produce high-volume harvests that are centrally located in the community," according to Simon Villalon, GGC president.

He said that aeroponic tower farm technology allows saving 75% to 90% space, which is an important consideration when operating out of a greenhouse, indoors, or on a rooftop.

The vertical farm is equipped with state-of-the-art technology that increases vegetable yield by a factor of 100, two times more than other farms.

Suited to a tropical climate, the structure supports vegetable growth year-round, with a target harvest of eight tons of leafy vegetables every year.

In the Philippines, aeroponic vertical farm is already tested in Taguig City, Villalon said, adding that some have been built up in San Fernando, Pampanga; and two in Bacolod City; and in Paranaque City

Text and photos by Danny Pata

LBG, GMA News

GUAM: Small Urban Farms Can Be An Oasis For Underserved Neighborhoods

Adrian Higgins | The Washington Post

October 15, 2020

I ate the last of the season's potatoes the other day, and it's not a bad harvest achievement when you consider I dug the lot in July from a bed no more than 15 feet long. I've eaten many meals over the summer where the bulk of my plate has come straight from my small community garden plot in the city.

It is amazing how much you can grow in a small space if the soil is good and you stay on top of tasks such as watering and weeding. But even in a pandemic-driven planting year full of homegrown potatoes, beans, and carrots, you have to face reality. If you relied on most urban veggie plots alone to feed yourself, never mind a large family, you'd be forever tightening your belt.

FLOWER GARDEN: Dominic Hosack, left, and Scott Kratz, of Building Bridges Across the River, take in the flower garden at the National Children's Center urban farm in Washington on Oct. 2. Adrian Higgins/The Washington Post

This is why I've had my doubts about whether urban agriculture can meet the challenge where it is most needed: in poorer, food-insecure neighborhoods.

Rosie Williams is in charge of such a garden, in an expansive side lot of the National Children's Center, an early-learning and educational development provider in Southeast Washington.

The garden packs a lot in. There are almost 70 raised planter beds, each four by eight feet and filled with deep, rich soil. That's a lot of growing area; the beds generate bushels of edible plants for most of the year. A shed houses tools, a single beehive is active, a few fruit trees ring the area, and one side is devoted to little benches for little people. The center, which normally houses classes for 188 children up to age 5, has been closed because of the pandemic, though a limited reopening is in the works.

Williams, a teacher and the garden coordinator shows me cool-season veggies growing in the fall, young plants of kale, collards, cauliflower, broccoli, and red cabbage. In other planters, mature plants are seeing out the season in robust vigor. The most obvious is a single pepper plant – now taller than Williams – whose leaves hide unripe green chiles that hang like ornaments. This is a mighty hot pepper from Trinidad named Scorpion, she said, and I have no doubt that it has a sting in its tail.

Nearby, a Japanese eggplant is full of purple streaked fruit. Along another path, Williams stops to lift a wayward cherry tomato vine and places it back in its bed. "I don't like to step on my babies," she said.

Elsewhere, wizened sunflowers have had their day. "We bring the kids out, we show them how to plant seeds, what the plants need," she said. "It's getting folks exposed to the garden." Food from the garden is used in the center's kitchen.

Thus the children (and their families) get a sense that food comes from the soil. This is not so obvious a connection in Ward 8. In this corner of the capital of the United States, there is one full-service grocery store for 80,000 people, and access to something as basic as fresh vegetables is limited.

"We have a lack of grocery stores," said Jahni Threatt, the CSA market manager for the nonprofit Building Bridges Across the River. "In Wards 7 and 8, we have three grocery stores." Residents eat from fast-food chains or out of convenience stores and liquor stores. "The food that's available isn't necessarily healthy," she said. Under Community Supported Agriculture programs or CSAs, growers provide direct weekly harvests to subscribers.

'Through the lens of equity'

The Baby Boomers Urban Farm that Williams coordinates at the National Children's Center is one of seven in a network of city farms east of the Anacostia River, including a one-acre farm run by Threatt's organization at THEARC, the arts, education, and social services campus at 1901 Mississippi Ave. SE.

This one farm produced as much as 1,600 pounds of food this year, but to provision its CSA program, the Building Bridges group turns to an additional 10 farms within 50 miles of the city, most of them Black-owned, said Scott Kratz, vice president.

AN OUTDOOR CLASSROOM: The urban farm functions as an outdoor classroom for almost 200 children and is a portal for sources of fresh vegetables for families in a predominantly Black area of Washington with just one grocery store. Here, the pollinator garden is shown on Oct. 2. Adrian Higgins/The Washington Post

The CSA runs three seasons of subscriptions, and bags are picked up on Saturdays at THEARC. The spring season was canceled because of the pandemic, but the summer and fall ones have been heavily subscribed and will provide food for more than 400 families this year. The season has also been extended, from the end of this month to the end of next. Lower-income subscribers get a reduced rate, and families on assistance get the food free, Kratz said.

This is heartening because the pandemic has hit the city's poorest wards the hardest. Many residents have underlying health issues related in part to their diet, and many are front-line workers or rely on the gig economy, putting them at greater risk of contracting the novel coronavirus, Kratz said. Ward 8, which is 92% Black, so far has the highest number of virus deaths in the district, with 127, according to city-data. Ward 3, 81% White, had 34 for the same period.

"We need to make sure that the programming we have is coming through the lens of equity and making sure the access people need is available to everybody in the community," said Dominic Hosack, farm director of Building Bridges.

I am rethinking my sense that mini-farms in the city are of limited value. They are, rather, a key portal into a larger infrastructure of food-security efforts.

Beyond their utility, they are places of deep reconnection, to the soil, to food, and to communities. In the food deserts of big-city America, they are the oases.

Lead photo: CHECKING ON HER BABIES: Garden coordinator Rosie Williams checks a pepper plant at the National Children's Center urban farm in Washington in October 2020. Adrian Higgins/The Washington Post

Tags Farm Rosie Williams Food Agriculture Gardening Vegetable Garden Plant Pepper Veggy

Q & A With Jake Counne, Founder, Wilder Fields

Jake Counne, founder, Wilder Fields shares greens with Calumet City Mayor Michelle Markiewicz Qualkinbush

Jake Counne, founder, Wilder Fields shares greens with Calumet City Mayor Michelle Markiewicz Qualkinbush. Pictured announcing Wilder Fields’ commitment to build and operate a full-scale commercial vertical farm in a former Super Target store in Calumet City, Ill.

When Jake Counne established Backyard Fresh Farms as an incubator in 2016, he knew that most large-scale vertical farming operations were large-scale financial disappointments.

So rather than attempting to patch up the prevailing model, he and his team chose to build something new from the ground up. “Other start-ups had tried scaling their operations with antiquated greenhouse practices,” he says. “We realized that to solve the massive labor and energy problems that persist with indoor vertical farming. We needed to look to other industries that had mastered how to scale.”

That vision, and several years of persistent innovation, came to fruition in 2019 when Counne announced he would transplant the successful pilot farm—now renamed Wilder Fields—into a full-scale commercial vertical farm. It is currently under construction in an abandoned Super Target store, with an uninterrupted expanse of three acres under its roof in Calumet City, just outside Chicago.

Wilder Fields is designed to supply supermarkets and restaurants in the Chicago metro trade area,. It is scheduled to sell its first produce in the spring of 2021. It will provide fresh produce to those living in nearby food deserts in Illinois and Northwest Indiana. In this Q & A With Jake Counne, Indoor Ag-Con will share more about Jake’s vision and plans for the future.

According to an Artemis survey, only 27 percent of indoor vertical farms are profitable despite attracting $2.23 billion in investments in 2018. Why do you think a small start-up like Wilder Fields can succeed where so many have yet to earn a profit?

We started four years ago by investing our own resources. We were also working on a very limited scale in a small incubator space. I think those constraints pushed us to be more discerning about what we should tackle first. In that time, we developed an array of proprietary software and hardware, many of which have patents pending. And we refined a new paradigm for vertical farming, moving from the greenhouse model to lean manufacturing.

We also had the good fortune of starting up just as many first-wave indoor farms were closing down. So we looked at those case studies to understand what went wrong. And, what they could have done differently—what was needed to succeed. In fact, the founder of one of those first-wave farms now serves on our advisory board and really helped us identify the right blend of automation and labor.

With traditional vertical farming, the bigger you get, the more your labor costs increase. It seemed to us that the first generation of large-scale commercial vertical farms thought they could simply scale-up labor as they grew.

But we realized that operational excellence and efficiencies are essential to marry growth and profitability. It’s very hard to control a wide variety of factors using a 100 percent human workforce; for the most part, our industry has realized we need to recalibrate and find ways to automate.

This 135 thousand square foot former Super Target store in Calumet City, Ill. will soon be transformed into one of the world’s largest vertical farms. This former retail space will house 24 clean rooms with the capacity to produce 25 million leafy green plants each year.

So automation solves the problem? It’s not as simple as that.

Now the problem that the pendulum has swung a little too far in the other direction. The industry is almost hyper-focused on automation—as if automation is the answer to all of the vertical farming’s problems. It’s not. Remember when Elon Musk tried using too much automation to produce the Model 3? I believe he called his big mistake “excessive automation” and concluded that humans are underrated.

We believe well-run vertical farms, and the most profitable ones will achieve the right balance of human labor and automation. And that’s been our laser-focused goal from day one—to bring down labor costs in an intelligent way, in order to make vertical farming economically sustainable.

We also reduced costs by repurposing an existing structure rather than building a new one. We located a vacant, 135,000-square-foot Super Target in the Chicago suburb of Calumet City. What better way to farm sustainably than to build our farm in a sustainable way? Along with City leaders, we think we can help revitalize the depressed retail corridor where it is located.

To my knowledge, converting a big-box space to an indoor vertical farm has never been done before. So we also are creating a blueprint for how to impart new life to empty, expansive buildings.

We also will provide opportunities for upwardly mobile jobs and environmentally sound innovations, and produce food that promotes community health.

Vertical farming is a fairly new development. How does it fit into the history of modern agriculture?

I make an analogy with the automobile industry. Field agriculture is sort of like the combustion engine. It came first and was easy to scale up, making it available to more and more people. There were obvious downsides to it, but soon the whole world was using the combustion engine, so we kept churning them out.

But as the detrimental effects began to accumulate, we started asking ourselves how to reduce the negative impact. That’s when the auto industry came up with hybrid cars—they’re the greenhouses in this analogy—and while they were certainly a less bad solution, they weren’t really the solution.

And now we have the fully electric car and it has started outperforming combustion engines on many different levels—just as indoor vertical farming is now beginning to outperform field agriculture

Today’s business mantra holds that the more you automate, the more efficient you become. So why is vertical farming any different?

There are certain efficiencies that don’t require specialized robotics, especially if these tasks can be accomplished in other ways that sustain quality and reduce costs. For example, instead of our workers going among the plants to tend them, the plants come to the workers in an assembly-line fashion that requires fewer harvesters. So it’s always a balance between the investment in specialized machinery and the cost of the labor that it will eliminate.

And while there’s definitely room for automation, it doesn’t always require new specialized robotics. In our industry, plenty of mature automation already exists that can be used to good effects, such as automated transplanting and automated seeding: both employ proven, decades-old technology.

So when I see some other start-ups trying to reinvent these processes, it’s hard to understand. They design and build new, expensive equipment—something possible with an unlimited budget—but in fact, a more affordable, simple solution already is available.

Start-up costs are notoriously difficult to finance. How were you able to get off the ground? What advice would you have for others in the industry?

There’s no easy way to bootstrap from a small start-up to a large scale without that big infusion of capital. You’ve got to decide early on if you should try to secure venture capital from institutional folks or search out more, smaller checks from friends and family and accredited investors.

As I see it, venture capitalists look to the founders’ background and education more than a business model that needs to be tested. If you don’t have that pedigree out of the gate, it’s an uphill battle.

We chose to take a different path, one that has proven successful for me in the past. It’s one where I led a group of investors who acquired overlooked residential properties on Chicago’s South Side. We brought stability to neighborhoods and now manage a large portfolio of quality rental properties. There was no white paper when we embarked on that venture, but we shared a vision for revitalizing good housing stock.

I also tell people to explore equipment financing, which thanks to the cannabis industry has opened up more and more. It’s definitely possible to finance some of this equipment. That seems to be a good route as well.

How will vertical farming impact the types of the crops you grow?

Wilder Fields grows and will continue to grow a wonderful variety of leafy greens. Many will be new to people because they can’t be efficiently raised in a field. So we are building our product line around flavor and texture as opposed to supply-chain hardiness.

But remember, the indoor vertical farming industry is in its very early days. Soon we will have a whole new frontier of applications and crops to grow. Especially now that certain companies are offering indoor-specific seeds. We’ve seen this movie before. When greenhouse-style vertical farms first came on the scene, they used seeds that were really bred for the field. They were doing okay. But, as soon as seeds were bred specifically for that greenhouse environment, yield and quality shot through the roof.

Now that we’re on the cusp of having specialized seeds bred specifically for our purposes, I think we’re going to see that same leap in yield and quality as well.

Of course, your initial planning could not have factored in a global pandemic and ailing economy. How have the ramifications of COVID-19 affected Wilder Fields, and your industry at large?

This is a time for us to champion the benefits of indoor agriculture because vertical farming is doing really well. Any farms primarily serving restaurants obviously had a problem. Companies that pivoted away from restaurants have been able to reach consumers more than ever. They’re capitalizing on their indoor-grown—and therefore much cleaner—product.

Supermarkets are our primary market. With people cooking more at home and looking for fresher and healthier choices, they’re eating more leafy greens. This is another positive phenomenon.

The success of your model relies heavily on your proprietary technology. Do you have any plans to eventually license your innovations—to make them available to others, for a fee?

That’s a question we’ve been asked a lot, not only from our industry but also from the cannabis industry. We may revisit that opportunity in the future, but it’s not something we’re immediately considering.

Here’s why. When I first entered the industry in 2016, I noticed there were so many consultants. Many people were licensing technology, but none of them were actually using that technology to grow leafy greens at scale. They’re like the folks who sell the pickaxes and the shovels instead of mining the gold.

My perspective is, “You’ve got to venture into the mine to know what sort of shovel and pickaxe you need”; in other words, that’s how to understand what models to create for logistics and ergonomics and what tools are needed to make them work. I did not want our company to be one of those that are just sort of camping outside the mine and hawking its wares.

I think the only way we can develop a solution that’s worth its weight is by operating our own technology and equipment at scale. And I haven’t seen anybody do that yet. Is it possible that we license our technology somewhere down the road once we’ve actually proven it out at scale? Maybe; but it’s not part of our business model right now.

So, along those lines, when will Wilder Fields deliver your first produce—grown in your first full-scale commercial vertical farm—to grocers in metro Chicago?

We have committed to the end of the first quarter of next year: March 2021. In addition to this Indoor Ag-Con Q & A with Jake Counne, you can learn more about Wilder Fields visit the company website

Four Innovative Design Responses To The Climate Emergency

Design Emergency began as an Instagram Live series during the Covid-19 pandemic and is now becoming a wake-up call to the world, and compelling evidence of the power of design to effect radical and far-reaching change

October 4, 2020

Design Emergency began as an Instagram Live series during the Covid-19 pandemic and is now becoming a wake-up call to the world, and compelling evidence of the power of design to effect radical and far-reaching change. Co-founders Paola Antonelli and Alice Rawsthorn took over the October 2020 issue of Wallpaper* – available to download free here – to present stories of design’s new purpose and promise.

The redesigned System 001/B, The Ocean CleanupTragic, and destructive though the Covid-19 crisis has been, it is one of a tsunami of threats to assail us at the same time. A concise list of current calamities includes the global refugee crisis; spiraling inequality, injustice and poverty; terrifying terrorist attacks and killing sprees; seemingly unstoppable conflicts; and, of course, the climate emergency. Since the start of the pandemic, global outrage against systemic racism following the tragic killing of George Floyd, and the destruction of much of Beirut have joined the list. Design is not a panacea to any of these problems, but it is a powerful tool to help us to tackle them, which is why Paola Antonelli and Alice Rawsthorn are focusing Design Emergency on the most promising global efforts to redesign and reconstruct our lives for the future.

Thankfully, there are plenty of resourceful, ingenious, inspiring, and empathetic design projects to give grounds for optimism. Take the climate emergency, where design innovations on all fronts: from the generation of clean, renewable energy, to new forms of sustainable food growing, and rewilding programs are already making a significant difference to the quality of the environment.

Here Are Four of Paola Antonelli And Alice Rawsthorn’s

Favorite Design Responses To The Ecological Crisis

Urban farm

Photography: © Nature Urbaine

Looming beside the Porte de Versailles subway station in south-west Paris is the colossal exhibition venue Paris Expo Porte de Versailles. By the time it hosts the handball and table tennis events in the Paris 2024 Olympics, Paris Expo will also be the home of Agripolis, the largest urban farm in Europe. Agripolis already operates other urban farms in Paris and occupies 4,000 sq m of Paris Expo’s roof. Over the next two years, it plans to expand across another 10,000 sq m, to produce up to 1,000kg of fresh fruit and vegetables each day using organic methods and a team of 20 farmers. The produce will be sold to shops, cafés, and hotels in the local area, while local residents will also be able to rent wooden crates on the roof to grow their own fruit and vegetables. Once it is completed, Agripolis’ gigantic rooftop farm at Paris Expo should place the Ville de Paris’ program of encouraging urban agriculture at the forefront of global developments in greening our cities.

The Ocean Cleanup

The redesigned System 001/B, The Ocean Cleanup

Scientists claimed that it wouldn’t work. Environmentalists warned that it risked damaging marine life. Few design projects of recent years have been as fiercely criticized as the Ocean Cleanup, the Dutch social enterprise founded in 2013 by Boyan Slat, who quit his degree in design engineering to try to tackle one of the biggest pollution problems of our time by clearing the plastic trash that is poisoning our oceans. Despite its critics and a series of setbacks, notably, when the original rig had to be towed back to San Francisco to resolve technical problems, the Ocean Cleanup has persevered. The redesigned System 001/B (pictured top) successfully completed its trials in the Pacific last year, and System 002 is scheduled for launch next year. The Ocean Cleanup has also developed a parallel project, The Interceptor, a solar-powered catamaran with a trash-collecting system designed specifically for rivers, and which can extract 50,000kg of plastic per day.

The Great Green Wall

Photography: The Great Green Wall of the Sahara and Sahel © UNCCD

Few regions are hotter, drier, and poorer than the Sahel, on the southern edge of the Sahara Desert. The brutal climate has wrought devastating damage in recent decades by causing droughts, famine, conflicts, poverty, and mass migration. The Great Green Wall is an epically ambitious project launched in 2007 by the 21 countries in the Sahel to restore the land by planting an 8,000km strip of trees and plants from the Atlantic coast of Senegal to Djibouti on the Red Sea. The practical work on the Great Green Wall, which is run as an African-led collective supported by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, is executed by each of the 21 countries. So far, more than 1,200km of greenery has been planted, although the focus of the project is less on the progress of the wall itself than on its impact in persuading each country in the Sahel region to transform what has become arid desert back into fertile farmland.

Zero-waste village

Photography: © Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP via Getty Images

This was to have been the year when the people of Kamikatsu, a village on the Japanese island of Shikoku, would achieve their goal of becoming a zero-waste community. The 1,500 villagers may struggle to produce no waste at all in 2020 but will come impressively close to doing so in a 20-year experiment that demonstrates the contribution a resourceful group of individuals can make to curb the climate emergency. The initiative began in 2000 when the local government ordered the closure of Kamikatsu’s incinerator. Rather than ship their waste elsewhere, the villagers took a collective decision to reduce and, eventually, eliminate it. They opened a Zero Waste Academy, where waste is sorted into 45 categories for reuse or recycling. Anything sellable is dispatched to a recycling store; fabric is upcycled at the craft center. The villagers have now eliminated over 80 percent of their waste, but are still struggling to recycle leather shoes, nappies, and a few other tricky exceptions.

Raising The Roof: Cultivating Singapore’s Urban Farming Scene

Urban farming has become quite a bit more than a fad or innovation showcase for our garden city. “The practice of urban farming has picked up in scale and sophistication globally in recent years,” said an Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) spokesperson.“

by STACEY RODRIGUES

NOKA by Open Farm Community at Funan Mall is one of the latest urban farms to take root in Singapore. (Photo: NOKA)

Call it a social movement or Singapore’s solution to sustainable self-sufficiency, but urban farming in our garden city is growing to new heights.

Whether you’re wandering through a residential area or exploring the recently re-opened Funan mall, you may have noticed new urban farms sprouting up – flourishing with fruit, herbs, and vegetables, occasionally tilapia inconspicuously swimming in an aquaponics system.

Urban farming has become quite a bit more than a fad or innovation showcase for our garden city. “The practice of urban farming has picked up in scale and sophistication globally in recent years,” said an Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) spokesperson.“

In Singapore, we encourage innovative urban farming approaches such as rooftop farming, which optimizes land, introduces more greenery into the built environment, and potentially enhances our food supply resilience.”Several companies have taken on the gargantuan task of cultivating the urban farming scene here. Rooftop farming pioneer, Comcrop (short for Community Crop), has been hard at work with its latest commercial farm, an 11-month-old greenhouse in Woodlands Loop. Edible Garden City (EGC) has more than 200 farms across the island and works closely with restaurants to ensure sustainable supply and demand.

Indoor micro-greens being grown at NOKA. (Photo: NOKA)

Citiponics has made a name for itself building water-efficient aqua organic “growing towers” that can be used to build anything from butterhead lettuce to sweet basil. In April this year, they opened the first commercial farm on the rooftop of a multi-story car park. The farm produces vegetables sold at the Ang Mo Kio Hub outlet of NTUC FairPrice under the brand, LeafWell.

Sky Greens is arguably the most impressive urban farming venture. It is the world’s first low carbon, hydraulic driven vertical farm, and has been recognized globally for its sustainability innovation.

There are several benefits to having our farms so close to home. Through community gardens or access to commercial-scale farm produce, the public has an opportunity to understand how food is grown.

As urban farmers take great care to ensure produce is pesticide-free, while incorporating sustainable zero-waste and energy-saving practices, there is also comfort in knowing where the food comes from and its impact on the environment.

Mushrooms fruiting in a chamber at NOKA. (Photo: NOKA)

“Having food production within the city or heartland [also] brings food closer to the consumers as it cuts transport costs and carbon emissions, and may improve environmental sustainability,” said a spokesperson from the Singapore Food Agency (SFA), the new statutory board created in April this year to develop the food supply and industry.

However, there are also broader concerns about the impact of climate change and food security in Singapore. It is why much is being done by the likes of the SFA to achieve “30 by 30” – “which is to develop the capability and capacity of our agri-food industry to produce 30 percent of Singapore’s nutritional needs by 2030,” said the SFA. “Local production will help mitigate our reliance on imports and serve as a buffer during supply disruptions to import sources.”

Singapore still has a long way to go as the urban farming scene is still a very young one. But there are opportunities for growth given the continued development here. In the URA’s latest phase of the Landscaping for Urban Spaces and High-Rises (LUSH) 3.0 scheme, “developers of commercial and hotel buildings located in high footfall areas can propose rooftop farms to meet landscape replacement requirements.”

Naturally, developers are taking advantage of this. One of the newest kids on the block is the urban rooftop farm run by EGC for a new Japanese restaurant, Noka by Open Farm Community at Funan. Noka is putting its money on offering Japanese cuisine that infuses local ingredients, from the butterfly blue pea to the ulam raja flower – ingredients are grown and tended to by the farmers at EGC’s 5,000 sq. ft. urban garden just outside Noka’s windows.

WOHA Architects’ edible sky garden, at the firm's office in 29 Hongkong Street, is a testbed for urban farming techniques. (Photo: WOHA Architects)

“The urban farming space is still in the emerging stages of development,” said Bjorn Low, co-founder of EGC. “We are literally scratching the surface of what’s possible. The areas of growth are in the application of urban food production in urban design and city planning, the use of urban farms for deeper community engagement, and the role urban farms plays in creating social and environmental impact in the city.”

While many farmers have found ways to convert existing rooftop spaces into farms or gardens, Jonathan Choe, an associate at WOHA Architects, says that one of the greatest opportunities to advance urban farming in Singapore is to build an entirely integrated system that not only incorporates growing spaces but also how these farms can interact with the entire building infrastructure – from building cooling measures to water recycling and energy management. The firm, which has their own testbed rooftop garden, is currently working on the upcoming Punggol Digital District development.

Dwarf bok choy being grown at WOHA Architects’ edible sky garden. (Photo: WOHA Architects)

But the greatest challenge for urban farmers is truly economies of scale. “Agriculture on its own is already a challenging industry due to industrialization of farming and our food system,” said Low. “Scale is a limiting factor in the city, and urban farming business models need to be able to adapt to both the challenges of a globalized food system and the availability of cheap food, whilst operating in areas of high cost and overheads.”

It begins with cultivating an awareness of and demand for local produce amongst both consumers and businesses alike. For Cynthia Chua, co-founder of Spa Esprit Group – the people behind Noka – taking an interest in agriculture is more than necessary, as it will have long-term benefits in preparing for the future generation of Singaporeans.

A harvest of white radishes from WOHA Architects' edible sky garden. (Photo: WOHA Architects)