Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Garden City Brings A Breath of Fresh Air To Urban Paris

The project, Garden City of the Crescent Moon, seeks to showcase what the design of the future can look like. How can environmentally-friendly concerns be integrated into urban design? Garden City seeks to provide the answers to that question.

By KC Morgan

August 6, 2021

The project, Garden City of the Crescent Moon, seeks to showcase what the design of the future can look like. How can environmentally-friendly concerns be integrated into urban design? Garden City seeks to provide the answers to that question.

Urban agriculture is a big part of the design. This is a method of using space to create growing areas for herbs, spices and vegetables. Urban agriculture not only improves soil quality but also reduces air pollution. Most importantly of all, it produces food.

By providing spaces for farming and gardening within urban areas, the plan also provides opportunities for economic benefits. Produce, spices and other products harvested from these mini urban farms can become a source of supplemental income. Roof terraces and small urban greenhouses create space for urban agriculture and create a unique look.

The design also includes spaces for housing, offices, sports facilities and areas for cultural activities. The distinct silhouette of the project overall is made to resemble the shape of canyons. The Garden City design follows the natural bend of the Lac des Minimes and its natural islands.

In the Garden City, all yards, roofs and public spaces will be used for growing and livestock. In fact, cattle breeding and dairy production areas will be right in town at the heart of the action. Meanwhile, everyone will have the chance and the space to grow all sorts of commodities, including corn, beans and herbs.

This design shows how urban environments can become more eco-friendly and self-sustaining in the future. How can urban agriculture spaces like this impact society, climate and health? This project can serve as a case study to help answer these questions. The plan is a design created by architecture firm Rescubika. The firm describes Garden City as “created by man for man” and says it will improve the urban landscape by “adapting it to our new way of living in the city.”

Via DesignBoom

Images via RESCUBIKA Creations

USA: VIDEO: Veteran Finds Peace, Purpose In Unique Kind of Farming

John Miller's routine may seem a bit "scaled-down" compared to his former life as a combat soldier. Miller spends much of his time in a 40-foot-long shipping container converted into a hydroponic farm field. Hydroponics involves growing plants without soil.

KENTUCKY

August 2, 2021

LOUISVILLE, Ky. — As John Miller prepared to leave the Air Force, the combat veteran admits he had no idea what he was going to do next.

What You Need To Know

John Miller served 14 years in the Air Force

The Louisville resident is the owner of Falls City Farms

Miller has found peace and purpose in hydroponic farming

In the future, Miller hopes to expand and employ fellow veterans

John Miller's routine may seem a bit "scaled-down" compared to his former life as a combat soldier. Miller spends much of his time in a 40-foot-long shipping container converted into a hydroponic farm field. Hydroponics involves growing plants without soil.

A close-up of Miller's baby kale. (Spectrum News 1/Jonathon Gregg)

“In essence, we sell a lot of things what we would consider baby," Miller explained. Little white turnips is just one crop of many growing inside Falls City Farms. “Right now I’m just pulling off the plug to turnips and then clean up any of the leaves."

The Iraq War combat veteran grows, prunes, packages, and sells a variety of greens to Louisville restaurants, online and at local markets.

“Here is our wasabi arugula, this is one of our fresh herbs, our dill, this would be our romaine trio," Miller said while touring his indoor farm.

Scaled-down? Maybe, but the hydroponic farm has helped Miller overcome what can be a sizable challenge for soldiers adapting to life after service.

“I got into this post-military, trying to find my next thing because I didn’t know what I was going to do when I got out," Miller said.

Miller served 14 years in the Air Force. His wife Amy is still active with 17 years to her credit. In his pursuit to figure out the next chapter of his life, Miller learned about hydroponic farming from a marine veteran in San Diego.

Falls City Farm grows a lot of produce in just 320 square feet. (Spectrum News 1/Jonathon Gregg)

His operation encompasses 320 square feet and boasts 6,600 individual plant spaces. Crops grow thanks to a sophisticated watering system and good-old-fashioned artificial sunlight.

“Because we are in a shipping container, the plants and the crops don’t get any of the big yellow sun outside so we have to create that inside," he said. "So we do LED lighting because it is better from an energy standpoint as well as heat."

Miller has lots of time and enough room to think about his life as a soldier and his new career as a farmer.

“If I am being frank with you, I miss being surrounded by other airmen and folks I used to lead," he said. "But it is calming to be in here with the plants and at the end of the day, that’s one of the reasons I chose this path.”

He was after peace and a purpose, and now his purpose includes bringing other veterans aboard.

“A lot of veterans, as we know, suffer from trying to find that next mission. Hopefully, one day soon be able to bring fellow veterans in here to teach them the art of farming through hydroponics to help them find peace and purpose as well," Miller said.

At first, Falls City Farms may appear to be a small operation, it’s only until you spend time on the inside do you see all the big ideas growing.

“I fell in love with the sense of a day’s accomplishment of work, a sense of comfort of being inside a greenhouse," Miller said.

Urban Farming Combats Food Deserts In Southeast Fort Worth With Community Empowerment

On the western edge of Glencrest Civic League in Southeast Fort Worth sits a property that soon could become an epicenter of education and agriculture for the community.

By Brooke Colombo

August 5, 2021

On the western edge of Glencrest Civic League in Southeast Fort Worth sits a property that soon could become an epicenter of education and agriculture for the community.

There sits a three-and-a-half-acre farm, Mind Your Garden, manned by husband and wife Steven and Ursula Nuñez, 38.

Several days a week, Steven heads to local grocery stores to pick up their unsold and undesirable produce. Much of it is still in edible condition while the rest is buzzing with flies and dripping with juice as the pair unload the crates to weigh them.

“It’s a lot of work. It’s hard work,” Ursula said. “But it’s good work and we like to work and it’s therapeutic.”

Today’s haul was on the high end for the farm. The most they’ve received is over 1,000 pounds. of discarded produce. The couple composts the produce to use as fertilizer.

They’ll add it to their terraced gardens to prepare the soil for planting in fall. For now, they’re sowing the seeds for an urban farm, with which they hope to combat food scarcity and promote healthy living.

Steven loads and unloads produce onto a scale. His truck bed was full with various fruits and vegetables, some still in edible condition. (Brooke Colombo | Fort Worth Report)

Cardboard from the discarded produce and recycled wood make up the terraced beds. The Nuñezes try to make the farm as sustainable as possible. (Brooke Colombo | Fort Worth Report)

Steven turns over the soil in the terraced garden beds to show how the compost enriches it. While they weren’t planting anything for the summer, some of the composted produce has sprouted new plants. (Brooke Colombo | Fort Worth Report)

In 2013, the Nuñezes bought the property, which once belonged to Steven’s parents. The house on the property eventually became their home. But Steven always planned to make the backyard into a garden.

Steven’s passion and expertise began when he studied abroad in Guatemala, where he learned about urban agriculture. He then attended a workshop from the National Center for Appropriate Technology designed to teach veterans about agriculture.

These experiences inspired him to pursue a master’s degree in landscape architecture from the University of Texas at Arlington. Steven and Ursula also received certifications in permaculture and Ursula has a background in education.

The Nuñez family sits in their backyard where they have coffee each morning and brainstorm ideas to serve their community. Steven said the farm is his greatest passion and they want it to be their lifestyle and business. (Brooke Colombo | Fort Worth Report)

While looking for a thesis topic, Steven learned about food deserts in Southeast Fort Worth, where some residents didn’t have sufficient access to food. The Nuñezes said they feel the best way to address this is through an educational shift in the community.

“Food is what brings all of us together,” Steven said. “We can be a facilitator for the community to come in and have healthy food options and the education and social community building aspect.”

Mind Your Garden is now one of a handful of community gardens in the Grow Southeast network, an independent initiative that helps farms reach success.

About Glencrest and Southeast food deserts

Not all of Southeast Fort Worth is a food desert, but some of its census tracts meet the federal definition for one. In order for a census tract to be a food desert, according to the USDA’s Food Access Research Atlas, it must meet two criteria:

The poverty rate must be 20% or higher, or the median household income must be at or below 80% of the median household income for the region.

At least 500 people and/or at least 33% of the households must live more than a half-mile from a large grocery store or supermarket in urban areas.

Food deserts usually have an abundance of convenience stores, fast-food restaurants and liquor stores.

A QT, Popeyes and Burger King sit on the Southbound side of HWY 287. The majority of food sources for the Glencrest Civic League are located in this area and are fast food, liquor or convenience stores. (Brooke Colombo | Fort Worth Report).

Save A Lot, located at 3101 E. Seminary Drive, is the only grocery store within the neighborhood’s boundaries. It’s considered a small grocery store and only part of its half-mile service radius extends into the neighborhood boundaries. (Brooke Colombo | Fort Worth Report).

Foodland is a large grocery store located at a Foodland at 3320 Mansfield Highway. It is the only large grocery store within a half-mile service radius of Glencrest Civic League. But just a small portion of the neighborhood is in this radius. (Brooke Colombo | Fort Worth Report)

Linda Fulmer, the executive director of Healthy Tarrant County Collaboration, who partners with Grow Southeast, has lived in Fort Worth since 1980 and remembers the shift of Southeast Fort Worth to a low-income area.

“(Southeast Meadowbrook) was an aging community with homes built in the 1930s and 1940s that were mainly occupied by aging original homeowners,” she said. “At that time there were eight grocery stores within three miles of my little house. Today only one of those stores remains in operation.”

Original homeowners in the area died or moved away, and the homes became available for rent by lower-income families. Many residents take their money to stores outside of the area, Fulmer said, which “erodes the shopper public for what stores remain.” Grocery stores are not a high-profit business, she said, so the stores look for a high density of residents with disposable income.

Glencrest Civic League is about five miles southeast of downtown Fort Worth and South of Highway 287. There is one small market (a Save A Lot food store at 3101 E. Seminary Drive) and one large grocery (a Foodland at 3320 Mansfield Highway) within a half-mile-service radius of the neighborhood limits.

Both are located at the southernmost edge of the neighborhood, making them less accessible to the majority of the neighborhood. Steven’s thesis, published in December 2018, found 70% of the neighborhood’s food sources are located at its southernmost tip. His thesis also found 9% of residents did not have at least one vehicle for their household.

“Part of understanding food insecurity is also understanding the demographics of the communities,” said Jesse Herrera, CoAct’s founder and executive director, who works with Grow Southeast. “Historically, there have been effects one could attribute to redlining or other systemic oppressions that have led our communities to the path they’re on.”

With 29% of households below the poverty line, Glencrest Civic League is considered a low-income neighborhood, according to census tract data. This is about double the poverty rate in Fort Worth (14.5%) and more than double the rate in Tarrant County (12%). Sixty-one percent of residents have a household income under $50,000.

The neighborhood is 56% Black, 36% Hispanic, 4% white, 2% Asian and 2% Pacific Islander. Of its 466 residents, 11.6% of the population has veteran status.

While lack of food options is an issue, so too is poor infrastructure. A lack of sidewalks, lack of exterior lighting and inefficient or insufficient bus routes can make it difficult to access food, Herrera said.

“If your food takes you an hour, two hours, three hours to get to and from there — that’s assuming these routes would actually be open by the time an individual gets off work— that’s part of what leads to food scarcity,” Herrera said.

The area’s economy affects food insecurity. Herrera said it’s harder to come across well-paying jobs in the southeast. Money goes toward rent first, and putting food on the table can be difficult with a minimum wage job.

The effects of food insecurity and little access to nutritious food have greater implications for the residents’ health, as Steven and Ursula have experienced.

“Steven’s family has a history of diabetes, and my family has a history of heart disease, which are both food-related diseases,” Ursula said. “I didn’t understand that with the food you consume, there are effects to unhealthy eating.”

A healthy diet can lead to a longer life, lower risk of obesity, heart disease, diabetes and some cancer, as well as help with chronic diseases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Steven and Ursula said despite exercising and training for marathons, it wasn’t until they changed their eating habits — cutting out alcohol and turning to a plant-based diet — that they saw a difference in their health.

How community urban farms address food scarcity

Though putting more grocery stores with healthy, affordable options in a more accessible place seems like the obvious solution, Nuñez suggests in his thesis this would have little effect on the buying choices of residents. The biggest factors are cultural background, tradition, education, custom and habit, his thesis argues.

“The whole nutritional education is extremely important,” Steven said. “It’s a long and tough journey to live a healthy lifestyle. For our community, some people just don’t know how to cook or eat healthily. They see fast foods and convenience as their only option. They need that strong support from their community to be successful.”

Community farms aren’t just about selling produce to residents, Herrera said. Rather, the farms also empower residents and boost the local economy to lift these communities out of poverty.

Once the farmers are equipped with successful business models, the farms could create opportunities for secondary and tertiary markets like neighborhood composting services and niche restaurants or cottage industries, he said.

“We’re looking at this through the lens of entrepreneurship and trying to create resources that support,” Herrera said. “These farms have the ability to create a lot of jobs.”

The future of Mind Your Garden

Steven points to a map they’ve created for the future layout of the farm. This includes plans for an orchard, a chicken coop and additional terraced garden beds. (Brooke Colombo | Fort Worth Report)

Ursula and their daughter Alejandra walk across their backyard from their home. The house, built in 1948, was the first property on the block. This space behind it will serve as a workshop and classroom to educate residents when the farm opens to the public. (Brooke Colombo | Fort Worth Report)

A retention pond is on the Northside of the property. The pond existed before they purchased the property. They plan to deepen it with the money they won in the Fort Worth Hispanic Chamber of Commerce’s pitch competition. (Brooke Colombo | Fort Worth Report)

Though it’s not open to the public yet, Steven and Ursula have already planned how they want to get the community involved on the farm.

They have a handful of volunteers helping build infrastructure to ready the farm for planting and a public opening. Preparing for the fall has been more than just physical labor, he said. Farming has allowed him and the volunteers to dig deep with each other.

“It’s a therapy session when we’re out here,” Steven said. “We’re out in nature. We’re working, sweating, talking about food insecurity and health. By the time they leave, we’ve had a pretty deep conversation. That’s definitely the community outreach aspect of it.”

To provide that experience to other residents, they intend to have gardening spaces where the community can get their hands dirty, as well as outdoor classroom space.

They will have a “healthy hour,” which will be like a happy hour focused on inviting the community over to eat and discuss their health.

“When we went plant-based and stopped drinking alcohol, we realized almost every social thing revolves around eating or drinking,” Steven said. “There’s a need for people looking to have a healthy lifestyle but still want to socialize.”

The Nuñezes said it’s an honor to be able to provide for their community and share what their farm will have to offer.

“This is a lifestyle business, not a part-time business or hobby. This is our life,” Steven said. “It means so much to us to get to express ourselves, our creativity, and be of service.”

Lead Photo: Ursula and Steven Nuñez unload hundreds of pounds of discarded fruit from local grocers to weigh. This fruit will get composted in the pile behind them to create nutrient-rich soil for planting. (Brooke Colombo | Fort Worth Report)

World’s Largest Urban Coffee Farm Tucked Away Amid Sao Paulo’s Skyscrapers

Brazil’s most heavily populated metropolis also is home to the world’s largest urban coffee farm, a 10,000-square-meter (2.5-acre) plantation that is nestled amid skyscrapers and hearkens back to the city’s origins

By Alba Santandreu

August 6, 2021

Sao Paulo, (EFE).- Brazil’s most heavily populated metropolis also is home to the world’s largest urban coffee farm, a 10,000-square-meter (2.5-acre) plantation that is nestled amid skyscrapers and hearkens back to the city’s origins.

Although it is situated just a few meters from the famed Ibirapuera Park in the heart of Sao Paulo, that oasis of around 2,000 coffee shrubs is unknown to most inhabitants of Latin America’s biggest urban center.

The plantation has an annual production of 600 kilos (1,321 pounds) of arabica coffee, primarily the catuai and “mundo novo” varieties, which are harvested over a short stint between late May and early June.

Once they are collected, the beans are dried on a net, ground into smaller particles and later donated to a social solidarity fund, the project’s coordinator, agronomist Harumi Hojo, said in an interview with Efe.

“The plantation has already served for research (purposes), and the proposal now is to produce coffee in a sustainable manner. Starting this year, we’ll be renovating the coffee plantation, bringing in other coffees to monitor the behavior of other varieties in the same conditions,” she added.

The coffee farm has been in operation since 1950 at the nearly century-old Instituto Biologico agricultural research hub, an institution founded during the early 20th-century heyday of Sao Paulo state’s coffee sector with the purpose of combating the coffee borer beetle, a harmful pest that was threatening the region’s plantations at that time.

The plantation today is one of the few remaining vestiges of Sao Paulo’s golden coffee era, when so-called coffee barons used the profits from their farms in the state’s interior to erect luxurious mansions in the city.

Among the last of these decaying mansions is one located on the city’s iconic downtown Paulista Avenue, a major thoroughfare where thousands of people and vehicles come and go every day.

An 850-square-meter (9,140-square-foot) building constructed on 2,000 square meters of land, that mansion built in 1905 is conspicuous amid a sea of modern glass office towers and may be converted into a culinary museum.

Coffee was synonymous with progress and wealth for decades in Sao Paulo, a one-time poor and isolated village that ended up overtaking Brazil’s former capital, Rio de Janeiro, as the country’s leading industrial hub. That crop also was primarily responsible for the modernization, urbanization and development of what today is the South American nation’s wealthiest and most-populated state.

Arriving from Central America in 1760, coffee was the main basis of Brazil’s economy between the mid-1800s and mid-1900s and at one time accounted for 80 percent of the nation’s exports.

Despite its subsequent decline and the rise of other crops such as soybeans, Brazil remains the world’s leading coffee producer and exporter and the second-biggest consumer of that beverage after the United States.

Brazil’s “economic, social and cultural development was financed by coffee, as were its big infrastructure and public works projects, including railway lines. Even Sao Paulo’s financial system, which had been very precarious” thrived due to coffee-industry profits, Marcos Matos, director of the Council of Coffee Exporters of Brazil (Cecafe), which represents and promotes the development of that sector, said in a telephone interview with Efe.

“Coffee was Brazil and Brazil was coffee,” he said. EFE

Roto-Gro Set To Blast Into Space With Food Production System

Roto-Gro is capitalizing on the space exploration boom, as it applies to a NASA challenge developing novel food production technologies to feed astronauts on long-term missions

Advanced Agritech Company Roto-Gro International (ASX: RGI) Is Aiming To Feed The World’s Astronauts.

August 9, 2021

Roto-Gro is capitalizing on the space exploration boom, as it applies to a NASA challenge developing novel food production technologies to feed astronauts on long-term missions.

Advanced agritech company Roto-Gro International (ASX:RGI) is aiming to feed the world’s astronauts as it capitalizes on innovations in food production systems and a boom in space exploration.

Roto-Gro World Wide (Canada), a wholly-owned subsidiary of Roto-Gro International, has applied to the Deep Space Food Challenge as part of its first step into the space agriculture sector.

Administered under an international collaboration between National Aeronautics and the Space Administration (NASA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), the international competition aims to incentivize the development of novel food production technologies needed for long-development space missions and terrestrial applications.

Roto-Gro’s application highlight’s the technological diversification and adaptability of its patented proprietary indoor vertical farming technology.

Astronauts’ food needs changing as missions evolve

Astronauts currently receive food from spacecrafts regularly launching from Earth, for example to the International Space Station.

However, NASA and the CSA recognize that as the distance and duration of space exploration missions increase, the current method of feeding astronauts will no longer be sustainable.

Future astronauts will be required to use food production systems on their voyages and be self-sustaining. The challenge aims to inspire the agricultural industry to help bring innovative food production technologies to space, reducing the need for resupply from earth and ensuring astronauts have continuous safe and nutritious food supplies.

The ability to develop sustainable food production is considered the crucial next step for longer-term human presence on the lunar surface and the future missions to Mars.

The challenge is not only about space exploration but also missions in extreme arid and resource-scarce environments on Earth. Like space, input efficiency will be key, including the efficient use of water and electricity to reduce resources needed for food production here on Earth.

Adapting Roto-Gro’s existing models key to space success

A new Roto-Gro rotational garden system — branded Roto-Gro Beyond Earth — will be designed with engineering adapted-off components from its existing Model 420 and Model 710 rotational garden systems.

Roto-Gro Beyond Earth will be a smaller, more portable version of the Model 420 but feature the injection feed system from the Model 710, significantly reducing the required resource inputs while maximizing nutritional outputs when compared to other indoor farming technologies.

Roto-Gro CEO Michael Di Tommaso said Roto-Gro Beyond Earth will enhance the already existing, unique benefits of its rotational garden systems, optimizing both the operational efficiencies and yield per m2, which is crucial to the development and prospective use of food production systems in space.

“The technology developed to form the application to the challenge is astoundingly demonstrating the vast applicability and sheer innovation of the company’s technology,” Di Tommaso said.

He said the company had developed several key relationships with organizations currently providing food system solutions for long-duration space voyages, along with others focused on using space to solve problems we are experiencing on earth.

“We look to develop and foster these relationships moving forward, further strengthening our position in the sector,” Di Tommaso said.

He said entering the space agricultural sector was a natural progression for Roto-Gro, supporting its vision to provide sustainable technological solutions for agricultural cultivation, critical to ensuring global food security.

“Food system innovation is crucial to our progression in space, and we are excited with the prospect of moving to the next phase of the Deep Space Food Challenge, while also generating other opportunities to develop and implement Roto-Gro’s technology in the industry,” Di Tommaso said.

Roto-Gro global forecasts international growth

Established in 2015, Roto-Gro is continuing to attract interest on a global scale.

The company recently partnered with agriculture company Verity Greens Inc. who has signed a binding $10M Technology License to purchase 624 RotoGro Model 710 rotational garden systems, with the first, flagship indoor vertical farming facility to be built in Canada.

The deal is expected to generate long-term, sustained recurring revenue with Di Tommaso hailing it as not only a “win-win” for both companies but a venture that works on a socially responsible level by helping tackle global food shortages.

“RotoGro will introduce our revolutionary technology into the booming indoor vertical farming space, while Verity Greens, utilizing the RotoGro Garden Systems and supporting technology, will operate with a viable and cost-effective competitive advantage,” he said.

“Verity Green’s first facility also serves to further its objectives – to roll out indoor vertical farming facilities globally utilizing RotoGro’s technology, not only to generate substantial revenue for both companies but also to provide a truly sustainable solution to address the issues caused by food insecurity.”

Lead photo: Pic: Giphy

This article was developed in collaboration with Roto-Gro International, a Stockhead advertiser at the time of publishing.

This article does not constitute financial product advice. You should consider obtaining independent advice before making any financial decisions.

Lettuce: Meet The Salad Kings of SA

Back home in East London in 1978, he made the decision to become a farmer, an option that was met with criticism from family and peers who did not have farming backgrounds.

By Glenneis Kriel

August 6, 2021

Not knowing what to do after finishing his military service back in the 1970s, Michael Kaplan set off to work on a kibbutz in Israel, where he was exposed to banana, dairy and chicken production.

From there, he backpacked through Europe, and was particularly impressed by the new technologies that farmers in the Netherlands were using to protect their crops and improve production efficiencies.

Back home in East London in 1978, he made the decision to become a farmer, an option that was met with criticism from family and peers who did not have farming backgrounds.

“My mother, Ethel, was a doctor and my father, Lewis, a lawyer, so they thought I was completely bonkers when I told them I wanted to farm,” recalls Kaplan.

In pursuit of his dream, he wanted to study agriculture at the Elsenburg Agricultural

Training Institute in the Western Cape, but entries had already closed by the time he applied. So he began working at what was then the English Trust Company farm in Stellenbosch, thanks to an introduction from his childhood friend, Bruce Glazer, who already worked there.

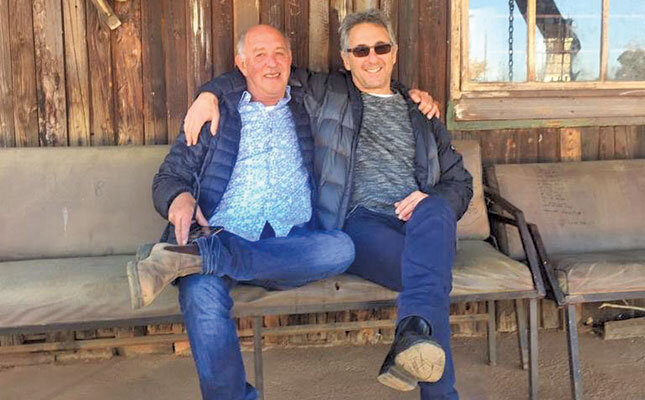

Dew Crisp was co-founded by childhood friends Michael Kaplan (left) and Bruce Glazer.

“It really was a case of being in the right place at the right time, as the English Trust Company was one of the first to introduce farming tunnels in South Africa.

“They produced tomatoes using the nutrient film technique [NFT] and experimented with the gravel flow technique [GFT] to grow butter lettuce and celery,” says Kaplan.

These hydroponic techniques, he explains, are similar in that both entail the circulation of a nutrient solution in a closed system. The difference is that with GFT, gravel is used as a growth medium, whereas, with NFT, plants are suspended and their roots exposed.

Early days

Kaplan worked at the English Trust Company for two years. He then learnt that the Joburg Market sold up to three times more vegetables than its Cape Town equivalent.

Deciding it was time to spread his wings, he drove up to Johannesburg, where he began looking for a business partner and land on which to grow his own produce.

“My mother lent me R10 000, which I used to rent land near Heidelberg [about 50km south-east of Johannesburg] and produce celery under 2 000m² of nets using GFT,” says Kaplan.

In 1981, Heidelberg was hit by a severe snowstorm. It destroyed almost all of Kaplan’s infrastructure, but he managed to save most of the crop and used the income from the sale to rebuild his operation.

“I kept costs low by doing almost everything myself, and using the income to grow the operation, reaching 8 000m² by the third year of production,” recalls Kaplan.

In his fourth year of operation, he started looking for land closer to the Joburg Market and with more favourable production conditions.

“These are actually two of the most important prerequisites for farming success; you need to be close to the market, and farm in a region where the climatic and production conditions are suited to the crop you want to grow. I learnt the hard way that the Highveld is unsuited to salad production in winter,” he says.

Financing

With a clearer idea of what he required, Kaplan bought land near Nooitgedacht and applied to the Land Bank for a loan.

Being unfamiliar with hydroponic production, the bank declined his application, but Kaplan managed to secure a loan from First National Bank at an interest rate of 26%. Fortunately, the market was far less competitive and demanding in those days, which enabled him to repay the loan quickly.

“It would be almost impossible to accomplish the same today; land, labour, infrastructure and production costs are exorbitant. And you buy everything in dollars and euros but get paid in rands,” he says.

Costs are driven up even further by international production standards and auditing programmes such as GlobalGAP and HACCP, which are required to supply most markets today, while market access is complicated by retailers and big buyers demanding huge supply volumes all year round.

An impressive growth path

In the intervening years, Glazer had studied agriculture at Elsenburg and thereafter also worked on a kibbutz in Israel. On his return in 1984 he bought a farm near Kaplan’s, and two years later the two decided to amalgamate their businesses to create better economies of scale.

The new company was called Dew Crisp. To add value to their produce, they sold ready-to-eat lettuce in pillow packs, a market they dominated for over six years.

Since then, Dew Crisp has grown into one of the largest value-added salad suppliers in South Africa, expanding their geographical footprint over time to lengthen their production season and mitigate climate and production risks.

Today, they have 10ha under production in Muldersdrift, 200ha near Bapsfontein and 140ha near Philippi, as well as processing plants in the West and East Rand of Gauteng and in Franschhoek in the Western Cape.

Dew Crisp also sources produce from between 15 and 20 selected farmers across geographically diverse regions, some of whom have been supplying the business for over 25 years.

The company’s empowerment arm, Rural Farms, supports and sources produce from five previously disadvantaged smallholder farmers.

In 2009, Agri-Vie, the Africa Food & Agribusiness Investment Fund, bought a 49% share in Dew Crisp, which enabled Kaplan and Glazer to grow the business and place greater emphasis on financial administration and corporate governance.

“We realised that it wasn’t enough to simply follow the market; we had to create our own destiny by becoming market leaders.

“To achieve this, we needed to be innovative and have a really good understanding of consumer trends. We’ve introduced many firsts on the market,” says Kaplan.

Glazer and Kaplan have also drastically diversified their market risks by supplying all the major retailers, various prepared-meal manufacturers such as the Rhodes Food Group, and food service companies such as KFC, McDonald’s, Nando’s and Burger King.

Production

Dew Crisp’s produce is grown under nets, in plastic tunnels and in open fields.

“Tomatoes, English cucumbers and peppers don’t like water or cold [air] on their leaves, so we generally produce them under plastic,” says Kaplan.

Shade nets are used in the production of salad vegetables, as these are sensitive to sunlight, heat and wind. The nets also protect against hail and bird damage while reducing the impact of rain by breaking up the droplets. In addition, they help to absorb heat and keep the production area cool.

Open-field production is highly seasonal and limited to hardier vegetables such as sweetcorn, onions and cabbage.

Most of the produce is grown in hydroponic systems, where the plants are supplied with nutrients via a nutrient solution. In most cases, Dew Crisp uses closed hydroponics (recycled water).

“Closed hydroponics is used for salad production in GFT, whereas open hydroponics is used in the production of tomatoes and cucumbers, as they are really sensitive to diseases that might spread with the water. For this reason, each of these plants has access to its own dripper,” explains Kaplan.

Sawdust and coco peat are used as growth mediums in the open hydroponic systems.

“Some farmers sterilise these mediums to reuse them, but I prefer using them only once to prevent disease outbreaks. We do, however, reuse the gravel in the open gravel system, after cleaning it with a chlorine solution at the end of each production cycle.”

In the same way, the crops that are planted in the soil are rotated to prevent a build-up of diseases.

Water quality largely determines the success of a hydroponic system, so a farmer should not even think of using it if the irrigation water is of poor quality or has high levels of chlorine or sodium. Water can be pretreated to rectify mineral imbalances, but this drives up costs. Water should, in any case, be filtered before use.

Dew Crisp has worked with scientists for years to refine its plant feeding programmes based on the nutritional requirements of various crops during different development phases.

“The trick is to supply exactly what the plant needs. An undersupply leads to plant deficiencies, while an oversupply is wasteful and might result in damage to the system and plants. To prevent this, we constantly monitor the recycled solution, plant growth and climatic conditions, and tweak the nutritional programme accordingly,” says Kaplan.

Achieving this with open-field crops is even more challenging due to soil differences. Soil, nonetheless, has a higher buffering capacity and is thus more forgiving.

The farm does not employ any climate-control technology because of its high capital and running costs. Instead, tunnel windows are opened and closed to augment ventilation and reduce the interior temperature.

Even without climate-control technology, production is energy-intensive, as the water has to be recycled continuously. Back-up generators are a necessity, as most of the salads will die within hours if water flow is interrupted.

Advice

Farming, and especially farming under protection, has become highly specialised over the years, with low profit margins leaving little room for error.

“In the past, when a buyer ordered a hundred frilly lettuces, we could plant 150 and it didn’t really have an impact on the bottom line. These days, production costs are so high that we plant to order and programme,” says Kaplan.

The shift has also made it increasingly important for farmers to make use of consultants to fill their knowledge gaps.

“If you want to be successful today, you need to surround yourself with people who are better skilled than you are in their respective jobs.”

Email Michael Kaplan at mkaplan@dewcrisp.com.

Lead Photo: Shade nets are used in the production of salad vegetables, as these are sensitive to sunlight, heat and wind. Photo: Dew Crisp

Technology Is Shaping The Future of Food But Practices Rooted In Tradition Could Still Have A Role To Play

Its executive summary said the food we consume — and the way we produce it — was “doing terrible damage to our planet and to our health.”

By Anmar Frangoul

August 6, 2021

From oranges and lemons grown in Spain to fish caught in the wilds of the Atlantic, many are spoiled for choice when it comes to picking the ingredients that go on our plate.

Yet, as concerns about the environment and sustainability mount, discussions about how — and where — we grow our food have become increasingly pressing.

Last month, the debate made headlines in the U.K. when the second part of The National Food Strategy, an independent review commissioned by the U.K. government, was released.

The wide-ranging report was headed up by restaurateur and entrepreneur Henry Dimbleby and mainly focused on England’s food system. It came to some sobering conclusions.

Its executive summary said the food we consume — and the way we produce it — was “doing terrible damage to our planet and to our health.”

The publication said the global food system was “the single biggest contributor to biodiversity loss, deforestation, drought, freshwater pollution and the collapse of aquatic wildlife.” It was also, the report claimed, “the second-biggest contributor to climate change, after the energy industry.”

Dimbleby’s report is one example of how the alarm is being sounded when it comes to food systems, a term the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN says encompasses everything from production and processing to distribution, consumption and disposal.

According to the FAO, food systems consume 30% of the planet’s available energy. It adds that “modern food systems are heavily dependent on fossil fuels.”

All the above certainly provides food for thought. Below, CNBC’s Sustainable Future takes a look at some of the ideas and concepts that could change the way we think about agriculture.

Growing in cities

Around the world, a number of interesting ideas and techniques related to urban food production are beginning to gain traction and generate interest, albeit on a far smaller scale compared to more established methods.

Take hydroponics, which the Royal Horticultural Society describes as “the science of growing plants without using soil, by feeding them on mineral nutrient salts dissolved in water.”

In London, firms like Growing Underground are using LED technology and hydroponic systems to produce greens 33-meters below the surface. The company says its crops are grown throughout the year in a pesticide free, controlled environment using renewable energy.

With a focus on the “hyper-local”, Growing Underground claims its leaves “can be in your kitchen within 4 hours of being picked and packed.”

Another business attempting to make its mark in the sector is Crate to Plate, whose operations are centered around growing lettuces, herbs and leafy greens vertically. The process takes place in containers that are 40 feet long, 8 feet wide and 8.5 feet tall.

Like Growing Underground, Crate to Plate’s facilities are based in London and use hydroponics. A key idea behind the business is that, by growing vertically, space can be maximized and resource use minimized.

On the tech front, everything from humidity and temperature to water delivery and air flow is monitored and regulated. Speed is also crucial to the company’s business model.

“We aim to deliver everything that we harvest in under 24 hours,” Sebastien Sainsbury, the company’s CEO, told CNBC recently.

“The restaurants tend to get it within 12, the retailers get it within 18 and the home delivery is guaranteed within 24 hours,” he said, explaining that deliveries were made using electric vehicles. “All the energy that the farms consume is renewable.”

Grow your own

While there is a sense of excitement regarding the potential of tech-driven, soilless operations such as the ones above, there’s also an argument to be had for going back to basics.

In the U.K., where a large chunk of the population have been working from home due to the coronavirus pandemic, the popularity of allotments — pockets of land that are leased out and used to grow plants, fruits and vegetables — appears to have increased.

In September 2020 the Association for Public Service Excellence carried out an online survey of local authorities in the U.K. Among other things it asked respondents if, as a result of Covid-19, they had “experienced a noticeable increase in demand” for allotment plots. Nearly 90% said they had.

“This alone shows the public value and desire to reconnect with nature through the ownership of an allotment plot,” the APSE said. “It may also reflect the renewed interest in the public being more self-sustainable, using allotments to grow their own fruit and vegetables.”

In comments sent to CNBC via email, a spokesperson for the National Allotment Society said renting an allotment offered plot holders “the opportunity to take healthy exercise, relax, have contact with nature, and grow their own seasonal food.”

The NAS was of the belief that British allotments supported “public health, enhance social cohesion and could make a significant contribution to food security,” the spokesperson said.

A broad church

Nicole Kennard is a PhD researcher at the University of Sheffield’s Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures.

In a phone interview with CNBC, she noted how the term “urban agriculture” could refer to everything from allotments and home gardens to community gardens and urban farms.

“Obviously, not all food is going to be produced by urban agriculture, but it can play a big role in feeding local communities,” she said.

There were other positives, too, including flood and heat mitigation. “It’s … all those benefits that come with having green spaces in general but then there’s the added plus, [which] is that you’re producing food for local consumption.”

On urban farming specifically, Kennard said it provided “the opportunity to make a localized food system” that could be supported by consumers.

“You can support farms that you know, farmers that you know, that are also doing things that contribute to your community,” she said, acknowledging that these types of relationships could also be forged with other types of farms.

Looking ahead

Discussions about how and where we produce food are set to continue for a long time to come as businesses, governments and citizens try to find ways to create a sustainable system that meets the needs of everyone.

It’s perhaps no surprise then that some of the topics covered above are starting to generate interest among the investment community.

Speaking to CNBC’s “Squawk Box Europe” in June, Morgan Stanley’s global head of sustainability research, Jessica Alsford, highlighted this shift.

“There’s certainly an argument for looking beyond the most obvious … ways to play the green theme, as you say, further down the value and the supply chain,” she said.

“I would say as well though, you need to remember that sustainability covers a number of different topics,” Alsford said. “And we’ve been getting a lot of questions from investors that want to branch out beyond the pure green theme and look at connected topics like the future of food, for example, or biodiversity.”

For Crate to Plate’s Sainsbury, knowledge sharing and collaboration will most likely have a big role to play going forward. In his interview with CNBC, he emphasized the importance of “coexisting with existing farming traditions.”

“Oddly enough, we’ve had farmers come and visit the site because farmers are quite interested in installing this kind of technology … in their farm yards … because it can supplement their income.”

“We’re not here to compete with farmers, take business away from farmers. We want to supplement what farmers grow.”

Lead Photo: Fruit and vegetable allotments on the outskirts of Henley-on-Thames, England.

Crazy Poet Discovers Solution To Vertical Farming Challenges

How on earth are we going to be able to make vertical farming a viable solution without disrupting the cities we live in

August 10, 2021

Lawrence Ip

Facilitating Workforce & Leadership Transformation Through Organisational Governance.

Keep Reading & The House Gets Bulldozed!

Dramatic I know (it's just one of those things). Nope, I won't be making myself homeless as I do actually need a roof over my head. What I also need is to get this crazy idea off my chest before I do actually lose my mind.

You see, I was watching a documentary a while back, about future cities, off the back of a few others that were about farming, global warming and the looming food crisis, and they got me thinking about vertical farming, and the issues the industry sector faces - namely scale.

That was the first thing that struck me.

How on earth are we going to be able to make vertical farming a viable solution without disrupting the cities we live in it, why heck, according to Pew Research world population is pitted to hit 10.9 Billion by 2100, with more and more folks migrating to cities. This begged a flurry of questions such as:

How are we going to feed everyone, and where on earth are we going to put the vertical farms that are supposed to feed them?

Will they really be able to provide the quantity of fruit and vegetables sustainably?

How much will they cost to build?

How much will they cost to run and maintain?

How do we store, pack and deliver the product?

What infrastructure does it require to make it work?

What about the effect on traffic?

What about the load bearing issues of weight on the structure of the farm, the actual building?

How on earth do we face the challenges facing vertical farming?

Don't get me wrong, I see incredible value in vertical farming and it could prove to be the answer to so many of the challenges we face ahead, because as we all know the way in which we produce the food we consume, and waste, is just not sustainable - not in the slightest. The globe's arable land is fast diminishing, and at the current rate the entire globe will be facing starvation soon after 2060 - it's a travesty just waiting to happen (if you haven't watched it yet I can highly recommend watching), Kiss The Ground, it's the documentary that got me started on the quest for answers.

A few weeks ago I woke up in the middle of the night, I had an epiphany.

Prior to going to sleep, I asked myself, what is the single most pressing problem you could solve that would provide the best bang for the buck?

When I woke from that sleep the answer came to me, it came down to answering the last question, which fundamentally is a design question.

Having previously watched a documentary series on super-structures, and thinking about logistics and transportation, it dawned on me that it was not a, how on earth question, but rather a let's go to sea proposition.

I jotted down these two words on the trusty notepad I keep bedside...

"... container ships."

That's right, container ships!

Don't be fooled into thinking that what you see is what you get. What you see on the top deck is just part of the picture, container ships have just as much, if not more storage in their lower decks.

It was like WOW! It makes complete and total sense, well at least to me it does. Let's outline the reasons why container ships could be the perfect vertical farm.

Container ships are designed to bare the types of load required in the design of a vertical farm.

You can move container ships around.

Container ships can have desalination plants built in.

They are freaking massive.

They can be even more massive. Fun fact: when the size of a ship is doubled, it increases the surface area by only 25%.

Transportation logistics is a non-issue.

No need to reinvent the wheel. It wouldn't take much to repurpose container ships that have been decommissioned.

Repurposed ships equals no scrap metal.

Access to the energy required to run them is at hand.

Image Credit: Bernd Dittrich - UnSplash.

That pretty much sums it up, and hey, I'm no expert, but yes, I am a poet, and it really doesn't matter whether I'm certifiable or not, I have at the very least put the idea out there. All I ask of you, is that before you send the men with the straightjacket around, that you consider the idea as a viable solution before discarding it. If anything I hope it provides some inspiration, maybe a spark of some out-of-the-box thinking of your own and I sincerely hope you found the read entertaining too. Thank you for making it this far. I'd love to hear your thoughts and ideas. Do you have a crazy vertical farming solution you'd love to get off your chest? Please feel welcomed and leave your thoughts below. Peace ✌

Image Credit: Bailey Mahon - UnSplash.

#verticalfarmingchallenges #arablelandcrisis #foodcrisis #circulareconomy

Lead photo: Image Credit: Torben - UnSplash.

Published by: Lawrence Ip

Crazy Poet Discovers Solution To Vertical Farming Challenges. hashtag#verticalfarming hashtag#containerships hashtag#crazypoettimes hashtag#sustainability hashtag#agriculture hashtag#environment hashtag#innovation hashtag#climatechange hashtag#circulareconomy hashtag#design hashtag#energy hashtag#arablelandcrisis hashtag#foodcrisis hashtag#kisstheground hashtag#verticalfarmingchallenges

The Farmory: Is Indoor Fish Farming A Viable Way of Tackling Declining Fish Populations?

The Farmory, an urban farming nonprofit, is the only indoor fish hatchery in Wisconsin. The nonprofit focuses on sustainable growing practices for both greens and gills

By John McCracken

August 6, 2021

For decades, Green Bay Wisconsin National Guardsmen stored munitions and trained new recruits in a stucco-clad, Chicago Street building built in 1918.

Now, the building is home to hundreds of fish babies.

The Farmory, an urban farming nonprofit, is the only indoor fish hatchery in Wisconsin. The nonprofit focuses on sustainable growing practices for both greens and gills. When it was founded in 2016, the focus was on growing produce indoors using aquaponic systems to both teach and provide a new source of food in the state’s harsh winters. As the program grew, they introduced percids such as yellow perch, walleye and sauger into their arsenal.

Executive director Claire Thompson said most aquaponic operations use tilapia because of its cheap price point due to massive global exports.

“There’s also some perceptions about (tilapia) here, especially in the Midwest, that it’s not as good of a fish,” said Thompson.

The Farmory settled on growing yellow perch to complement their vegetable production because of its beloved place on Wisconsin plates and its volatile population over the years.

They soon discovered a problem. No one was growing perch indoors yet.

“That led us down the road toward ‘more research needs to be done,’” said Thompson. “We need to be able to set up our own hatchery to produce a steady and consistent supply of year-round, feed-trained fingerlings that are grown from the egg in an indoor environment.”

In the bottom level of The Farmory, budding fish are separated by a bio-secure room and health protocols. Volunteers and entrepreneurial and technician students take turns monitoring temperatures in the complex hatchery. Each separate tank mirrors life cycles and seasons of growing yellow perch and their walleye cousins. During a late June visit, an insulated tank is sealed shut and a quick peak inside shows adolescent perch huddled together for warmth. The fish don’t know about the humid Midwest summer outside because their faux-winter hovers around a chilly 30 degrees Fahrenheit.

The Farmory (Photo Credit: John McCracken for Great Lakes Now)

Schools in session

Being a nonprofit allows The Farmory to not have to worry about mass production or profit margins as much as for-profit hatcheries that already exist on slim margins. Instead, they worry about being a stepping-stone for future fish farmers.

The Farmory offers 12-week technical programs that provide hands-on trainings and lectures from researchers and ichthyologists. Since The Farmory launched both pathway programs in 2020, they have had 34 graduating students.

Thompson said that for students interested in aquaculture there are only two options in the state. Students can go to a four-year program at either University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point or UW-Milwaukee.

For the students coming through The Farmory’s doors—who range from recent high school graduates to retirees—fish-wrangling fares better than test-taking in the growing industry.

“There’s a lot of jobs in the aquaculture industry that don’t require a four-year degree,” Thompson said. “You have to have people with basic technical skills.”

The Farmory’s students are much like their customers. Their interest and aspiration range from basement or backyard hobby farming to scalable commercial production. The Farmory grows fingerling perch until they are between 2 to 4 inches and then customers take them to grow them to adult size for spawning or frying.

In 2020, they had 60 customers and sold fish across state lines to Michigan, Ohio and Minnesota. Thompson said most customers bought between 100 and 500 fish, but a handful purchased thousands of perch pounds to fuel their own commercial fishery endeavors.

“We want to be able to secure a local food supply. We also want to teach people about aquaculture as a viable business opportunity,” said Thompson.

The Farmory (Photo Credit: John McCracken for Great Lakes Now)

Problems come with being new

Being the only indoor perch hatchery comes with its challenges though.

The COVID-19 pandemic hindered The Farmory’s first hatching year. They weren’t able to get brood stock up to full capacity due to supply-chain complications. The urban farm is working on getting their population to a sustainable level.

Additionally, Thompson said that there is a lack of research and applied standards when it comes to growing perch indoors.

“It’s not like any other agricultural commodity product like dairy or chickens,” said Thompson.

Thompson said yellow perch have an innate biology barrier, where survival is harder to come by—something that is important for an organization focused on producing and spreading young perch. Perch also don’t have a set diet. As of now, The Farmory feeds their perch a trout diet, which Thompson said is slightly fattier.

“We have to find a way to get enough people into the business of (indoor fisheries) to we can work with feed companies to be able to develop affordable feed,” said Thompson.

On the other end of the process chain, Thompson said a decline in the perch population since the booming years of yore has led to a lack of skilled fish processers and sustainable operations.

“Because of the decline of Great Lakes commercial fishing, we’ve also seen a decline in processors to clean and process fish,” said Thompson.

Smaller, sustainable scale

Sharon Moen echoed a lot of Thompson’s observations of the industry at large.

Moen is an outreach specialist with Wisconsin Sea Grant— a statewide research and stewardship program dedicated to the resources of Great Lakes—in charge of the Eat Wisconsin Fish Initiative. Eat Wisconsin Fish was established in 2013 to become a hub for information and resources for the state’s fish producers and consumers.

Moen said the many people in the industry believe the future of fish farming is heading indoors because of the effects of climate change on the industry, its habitats and the fish themselves.

“Algae blooms and invasive species can’t get into the water,” Moen said of indoor, contained aquaculture systems.

Moen also said that the way consumers and producers import and export massive numbers of commodities has a continued effect on the planet due to gas emission.

“We have to stop carting things around the globe in order to really truly cut down on carbon emissions,” said Moen. “We need to learn to eat and grow our food more locally.”

In the past year, Moen observed how breaks in the supply chain—caused by global catastrophe such as the COVID-19 pandemic—make everyone and every supplier vulnerable. Just as the majority of The Farmory’s students are scaling down, many suppliers are focused on local, small-scale consumption.

“I think most (fisheries) are very modest people raising for their local community consumption,” said Moen.

Moen said to alleviate stress on perch’s floundering population and high price point – which she observed at upwards of $20 a pound last year – consumers could switch to a more abundant species like whitefish.

Both Moen and Thompson pointed out that adjusting to problems in the industry, whether you’re growing fish in a bedroom tank or in cavernous outdoor ponds, takes agility and a love for fish.

“It’s like gardening,” Moen said. “You have to have a knack for it and take care of what you’re growing.”

Exeter Town Council Considers Turning Schartner Farm Into Massive High-Tech Agricultural Project

On Wednesday, the Exeter Town Council will hold a public hearing on a proposal for a zoning change that will allow for the development of a high-tech farm, with huge parking areas for trucks, a building the size of the Warwick Mall, and a 13 acre solar farm.

By Frank Prosnitz

August 8, 2021

On a crisp October morning, leaves turning the color of the rainbow and pumpkin patches filled with pumpkins awaiting children to turn them into Jack-O-Lanterns, thousands of parents, children, and grandparents would flock to Schartner Farm in Exeter.

They’d likely find the home-cut French Fry stand, and inside freshly baked pies, homemade jams and newly picked apples of every variety, fresh vegetables and fruits, and an array of Mums.

But that was all a few years ago, before the 150-acre farm closed when a fire partially destroyed its main building in 2015, leaving fields that once produced corn and strawberries, pumpkins, and large variety of vegetables, to go fallow. The farm was founded more than a century ago, in 1902.

Farm buildings were left behind decaying, greenhouses in disrepair, and nearby residents fearful that the land would become a strip mall, the likes of which are found only in Rhode Island’s more urban areas.

On Wednesday, the Exeter Town Council will hold a public hearing on a proposal for a zoning change that will allow for the development of a high-tech farm, with huge parking areas for trucks, a building the size of the Warwick Mall, and a 13 acre solar farm.

Some in the community are fearful the council will approve the zone change and a project that will forever change the character of the land, and possibly the community. Others see it as providing a needed food source, making the property productive again.

The zone change, proposed by Richard Schartner of RI Grows, would establish a Controlled Environmental Agricultural Overlay District that, according to the town’s public hearing notice “would contain eligibility and process standards for establishing Controlled Environmental Agriculture (“CEA”) facilities which provide a controlled environment for year-round production of food and plants using a combination of engineering, plant science, and computer managed greenhouse control technologies to optimize plant growing systems, plant quality and production efficiency. The “CEA” facilities would also include onsite solar power as a ‘by-right’ accessory use to the primary CEA agricultural facility.”

In other words, high-tech greenhouse that are driven by technology, a building that would reportedly be 35 feet high and cover 20 acres, powered by solar energy.

The council’s public hearing is being held at the Metcalf School and begins at 6:30 p.m. on Wednesday.

In June, Rhode Island Grows broke ground for a 25-acre indoor tomato farm on Schartner Farm. At the time it was reported, the farm would have hydroponics technology, powered by solar energy, using recycled rainwater.

According to the RI Department of Environmental Management, the tomato farm facility would cost $57 million and take eight months to build, produce 14 million pounds of tomatoes, and employ 80 people. DEM said it is only the first phase of the $800 million project that will eventually add 10 greenhouses over the next decade.

“As industrial agricultural in other areas of the country and central America have squeezed out local farms, this self-sufficient facility will enable the Schartner family to continue their century of farming in Rhode Island with another 100 years,” the DEM said in a statement.

Opponents of the proposed zone that would permit the new high-tech farming, are concerned that the process is more manufacturing than farming and “since a CEA (Controlled Environmental Agriculture) does not need farmland, should a huge CEA be located on a farm when preserving what’s left of Rhode Island’s farms is critical?” wrote Megan Cotter of the Exeter Democratic Town Committee.

“The project would negatively impact the scenic beauty of Route 2 and disrupt the quality of life for all in the vicinity,” she wrote. Cotter emphasised she’s not opposed to high-tech farming but feels it’s more appropriate in industrialized locations.

Another Exeter resident, Asa Davis, who owns more than 100-acres in town, is a strong proponent of the project.

“If you really want to preserve things like natural resources for future generations, you don’t use them,” Davis wrote. “Traditional agriculture can wear land out, and uses a lot of water, fertilizer and pesticides. The 1930’s Dust Bowl in the Midwest was man-made, not a natural occurrence. If we want to preserve water and farming resources for future generations, CEA looks like a good solution. The greenhouse is big, but it’s got a dirt floor. If it doesn’t work out, it wouldn’t be hard to remove it and revert to traditional farming – nowhere near the cost or effort of removing a shopping mall.”

Lead Photo: On Wednesday, the Exeter Town Council will hold a public hearing on a proposal for a zoning change that will allow for the development of a high-tech farm, with huge parking areas for trucks, a building the size of the Warwick Mall, and a 13 acre solar farm.

iUNU Announces Acquisition of CropWalk, Significantly Expanding The Consulting Capacity For Both

iUNU (“you knew”) is an agricultural machine vision company headquartered in Seattle, with satellite offices in California, Florida, and Toronto as well

iUNU (“you knew”) is an agricultural machine vision company headquartered in Seattle, with satellite offices in California, Florida, and Toronto as well. Founded in 2013 and currently with over 40 employees across the world, the company leverages computer vision and machine learning to allow farms to better manage crop issues and optimize growth cycles. The LUNA system focuses on identifying growing maladies before the crop is affected and promotes better accountability of growing practices through the workflow management application.

In making the announcement, Adam Greenberg, CEO of iUNU, said: “Rising consumer demand is accelerating the growth of the greenhouse industry, but the massive shortage of both growers and manual labor requires a scalable machine vision solution to further produce supply. Having a renowned agronomy team to assist in deploying state-of-the-art technology like LUNA will have a profound impact on our constantly improving capacity to help growers increase quality, yields, and profits. 65% of growers are above the age of 55, and the shortage of qualified people is hitting the fast growing industry hard. Something has to give, thus the future is the centralized management of distributed facilities.”

CropWalk is an integrated pest management (IPM) company that was founded in 2019 and has an expanding team with employees located in key regions across North America, including their Founder and Director of Partnerships, Charlie McKenzie, in the US Southeast, and the CropWalk Director of Operations, Robert Shearer, and Director of Science, Education, and Strategic Development, Ayana Stock, along the US West Coast.

They are a widely recognized name in the horticultural industry for their unbiased approach to empowering growers of high-value crops with the knowledge and resources to prevent and manage pests and plant pathogens. With plans underway to expand their crop care services, CropWalk is well-known for how they customize a unique suite of services for operations of various kinds, offering risk assessments, IPM program development, training sessions, the online CropWalk Academy, and more, including remote monitoring services, the capacity of which are now dramatically enhanced by iUNU’s LUNA system.

Charlie McKenzie, CEO of CropWalk, said: “We’ve always used remote monitoring technology to identify and mitigate conditions that foster plant pathogens. The mantra we live by at CropWalk is ‘Start Clean, Stay Clean.’ Working with the iUNU team and using LUNA, we can digitally walk a crop from anywhere at any time allowing our team to effectively prevent problems before they result in economic injury. Our clients want us around more often, with LUNA, we can be there all the time. It’s a win for growers, a win for CropWalk, and a win for iUNU.”

LUNA, iUNU’s chief product, is an AI tasked with connecting plants, facilities, and people through a single interface. LUNA runs on computers or mobile devices and turns commercial greenhouses into precise, predictable, demand-based manufacturers. LUNA was born in the heart of Seattle, trained in Silicon Valley and the greenhouses of Washington, and is accessible from everywhere.

The future of crop care in modern greenhouses that will feed families for generations involves both people’s human expertise and the best available technologies. The union of iUNU and CropWalk is great news for CEA crop producers seeking the advantage of cutting-edge artificial intelligence, computer vision, and machine learning coupled with industry-leading IPM & biological services. Two companies that were excelling independently have joined forces to set a new standard for the remote monitoring of crops. Services of both companies will still be available for clients independent of one another but will have expanded resources at their disposal.

iUNU’s acquisition of CropWalk helps both companies become more effective in their work towards an important common goal: reducing the cost of nutrient-rich food reaching urban centers while helping growers thrive.

Growing Up: The Next Frontier In Farming Is Vertical And It Could Cut Canada's Reliance on Imported Food

The spicy mustard micro green begins its short life in a plastic tray of mud, filed away in a germination warehouse at an industrial park on the outskirts of Guelph, Ont. It spends several days in hot and humid darkness, using all its energy to open itself, push through the top layer of soil and unfurl its first two tender leaves

By Jake Edmiston

July 30, 2021

The spicy mustard micro green begins its short life in a plastic tray of mud, filed away in a germination warehouse at an industrial park on the outskirts of Guelph, Ont. It spends several days in hot and humid darkness, using all its energy to open itself, push through the top layer of soil and unfurl its first two tender leaves.

In the germination room, trays of mustard greens all sit on shelves the size of ping pong tables, stacked in rows up to the roof. The plants are ready after about two days and the automated growing system comes to retrieve them, pulling the shelf from its stack and ejecting it through a slot in the warehouse wall.

Soaring crop prices will catch up to consumers

Next, they enter another, larger warehouse, with more shelves stacked up three to four storeys high. Here, the spicy mustard greens feel light for the first time. More than 14,000 LED lamps shine for 14 to 20 hours a day, using only the part of the light spectrum that the plants will need: red and blue. So the warehouse is always a thick, glowing magenta.

After spending two days in the darkness of the germination room, a large flat of spicy mustard greens is moved into the 45,000 square foot vertical farming grow room. PHOTO BY GLENN LOWSON FOR NATIONAL POST

“It’s always a beautiful, spring day,” says Juanita Moore, the executive director of operations at GoodLeaf Farms, which owns this indoor farm in Guelph.

It is incredibly important that these mustard greens survive, not just for GoodLeaf — the company uses them for its Spicy Mustard Medley and Ontario Spring Mix — but also for the long-term stability of the Canadian food system.

Canadian agriculture scholars are warning that the country’s dependence on California and other southern growing regions for fresh produce through the winter has become a national security risk.

“We have to really ask the question, ‘How secure are we?'” said Evan Fraser, director of the University of Guelph’s Arrell Food Institute. “On fruits and vegetables, we are not secure at all.”

On fruits and vegetables, we are not secure at all

EVAN FRASER

The pandemic has given companies and consumers a glimpse at how a global crisis can stymie supply chains and push trading partners to hold back exports. And the extreme drought and wildfires that have threatened California’s vast crop production this summer are just the latest example of a glaring vulnerability in the Canadian food chain, which relied on $11.2-billion worth of imported vegetables, fruits and nuts last year. Farmers in the United States supplied $5.4 billion of that produce — $3.1 billion of which came from California.

“Suddenly this idea that California might not be able to provide food is not that farfetched at all — to the point I’m actively kind of worried about it,” said Lenore Newman, director of the Food and Agriculture Institute at the University of the Fraser Valley. “My worry is, we’re going to start having shortages, because California’s production is going to fall. They don’t have the water.”

Fraser and Newman are part of a growing chorus of professors and industry leaders calling for Canada to stop relying on imports from the U.S. and Mexico and start feeding itself, fast. The best hope to do that, in a country with only five or six good growing months, is to farm indoors.

Juanita Moore, the executive director of operations at GoodLeaf Farm, in Guelph, Ont. PHOTO BY GLENN LOWSON FOR NATIONAL POST

“If the trends continue, we’re in real trouble in North America,” Newman said. “Growing all of this food intensively in one location and moving it all over the continent is not going to work. So we may as well start now. I mean, we should have started five years ago but now is good too.”

This ambition for Canada to grow its own supply of fresh produce in the dead of winter isn’t as implausible as it might sound. The country actually isn’t bad at growing things indoors. Canada’s greenhouse industry is already proficient at growing tomatoes, cucumbers and peppers — to the point that 81.2 per cent of the domestically grown supply of cucumbers come from a greenhouse, according to Statistics Canada.

Historically, the problem with greenhouses has been that they rely on the sun, which means production dips in the darker, winter months. They’re also expensive to heat. Even in summer, the sun can be confounding, as Newman put it. It’s bright one day, obscured by clouds the next. It hits the plants unevenly, making it tougher to produce the sort of uniform crops that the market demands.

The new frontier in farming, Newman said, is to sideline the sun. Advancements in more efficient LED light technology have reduced the cost of growing plants indoors, allowing greenhouses to add lights to augment the sun and effectively extend their growing season.

Cheaper LED technology has also made it possible to farm without any sun at all, in the sort of windowless warehouses “you’d put a Costco in,” Newman said.

LED lights are calibrated to only emit the red and blue of the light spectrum. PHOTO BY GLENN LOWSON FOR NATIONAL POST

This new generation of indoor crop factory can pump out more production per acre because the farmer doesn’t have to worry about sun exposure, droughts or pests. In vertical farming — a common method in the rapidly changing world of closed environment agriculture — the plants are stacked one on top of another, in soil trays or in hydroponic fluid, with LED lights in between.

“You can take a 100-acre farm, compress it into a one-acre farm, and put the rest back into wilderness,” Newman said.

Vertical farms can recycle much of the water they use, and often cost little to heat through winter thanks to warmth from the LED lamps and the plants themselves. But possibly the most important perk, she said, is that “everything will taste better.”

The general vision, for Newman and others, is to have vertical farming operations supplying produce to every region in the country. That would drastically reduce the distance between farm and market, so producers would be able to focus on making varieties that taste good instead of the “wooden” varieties preferred in California because they travel thousands of kilometres without bruising.

Major food and technology companies have been funnelling capital into the indoor farming sector, including French fry giant McCain Foods Ltd.’s roughly $65-million investment to become the single largest shareholder in GoodLeaf.

A sampling of three of the six varieties of leafy greens GoodLeaf cultivates in it’s indoor 45,000 square foot vertical farming operation in Guelph, Ont. PHOTO BY GLENN LOWSON FOR NATIONAL POST

But vertical farming hasn’t quite proven itself to be a profitable option yet, according to one analyst who follows the sector. The building costs for new vertical farms and other large-scale indoor models can range as high as $30 million to $50 million per site. Even when the facilities are built, high energy bills and labour costs make it difficult for the farms to make consistent profits. So most operations focus on crops that grow quickly, can be packed into tight spaces and sell at a premium.

“A lot of these groups are still losing money,” said Steve Hansen, managing director at Raymond James Ltd. “The big challenge is, ultimately, getting to profitability.”

And the goal isn’t just to reach profitability by competing with organic farms on expensive niche products like spicy mustard greens. If the true purpose is to replace Canada’s $11.2-billion reliance on imported produce, indoor operations need to be able to reach the sort of scale that will allow them to compete in the broader fruit and vegetable market. More advancement in LED lighting and automation inside the farms are expected to keep tamping down energy and labour costs.

“The vertical industry is still not quite yet on par with field-grown product,” Hansen said. “They’re getting down there and they’re getting closer but they’re still not there.”

Hansen estimated that globally, capital investments into vertical farms and next-generation indoor farming technology are now in the “billions of dollars” globally.