The Future of Food

The Future of Food

MARCH 20, 2017 18:06

From computer-monitored growing chambers and vertical farms to superfoods, the increasing needs of a burgeoning population have led to technology-fuelled innovations in agriculture

If history is to be believed, the plow and seeder were invented by the Mesopotamian civilisation in 3000 BC. In 2017, if you do a Google search on technology used in farming, the results would display similar tools, with the exception of the innovations of the last century.

How does limited evolution in farming technologies fare against the challenge of feeding a population this world has never seen before? In the late 1950s, when serious food shortages occurred in developing nations across the world, efforts were made to improve the growth of major grain crops like wheat, rice and corn, by creating hybrid grains that responded well to the application of fertilisers and pesticides. This meant, especially for countries in Asia, high yields per hectare. However, the repercussions of ever-increasing use of chemicals are now visible, with many diseases being traced back to the use of chemically-grown food. A technology that was supposed to help feed the growing world has proven to be more hindrance than help. Today, more people are moving towards organic produce, but the question remains – how do we connect growing more and better with healthy and organic?

At a TED Talk in December 2015, Caleb Harper, Principal Investigator and Director of Open Agriculture Initiative at MIT Media Lab, gave a peek into the future of urban agricultural systems.

His team has created a food computer, a controlled-environment agriculture technology platform that uses robotic systems to control and monitor climate, energy, and plant growth inside a specialised growing chamber. Climate variables such as carbon dioxide, air temperature, humidity, dissolved oxygen, potential hydrogen, electrical conductivity, and root-zone temperature are among the many conditions that can be controlled and monitored within the growing chamber. While the food computer remains a research project at the moment, there are companies using technology in their current food-growing ecosystems.

Japan has been experimenting with Sandponics, a unique cultivation system that uses no soil, only sunlight and greenhouse facilities.

A small section of sand is supplied with a mix of essential nutrients, and in some cases, the same section of sand has been in use for over three decades. The first systems were developed in the 1970s and are still evolving today. They have proved to be not just efficient, but affordable and scalable too.

The 750-square-kilometre island of Singapore, feeds a population of five million by importing more than 90% of its requirement. With available farmland being low, the only way to grow food is to go vertical. This is where vertical farms and farming entrepreneurs and companies such as Sky Greens have come up with innovative solutions that are not resource-intensive.

India initiatives

India isn’t far behind in exploring urban farms either. Chennai-based Future Farms, Jaipur-based Hamari Krishi and a few others are bringing the urban farm revolution to India.

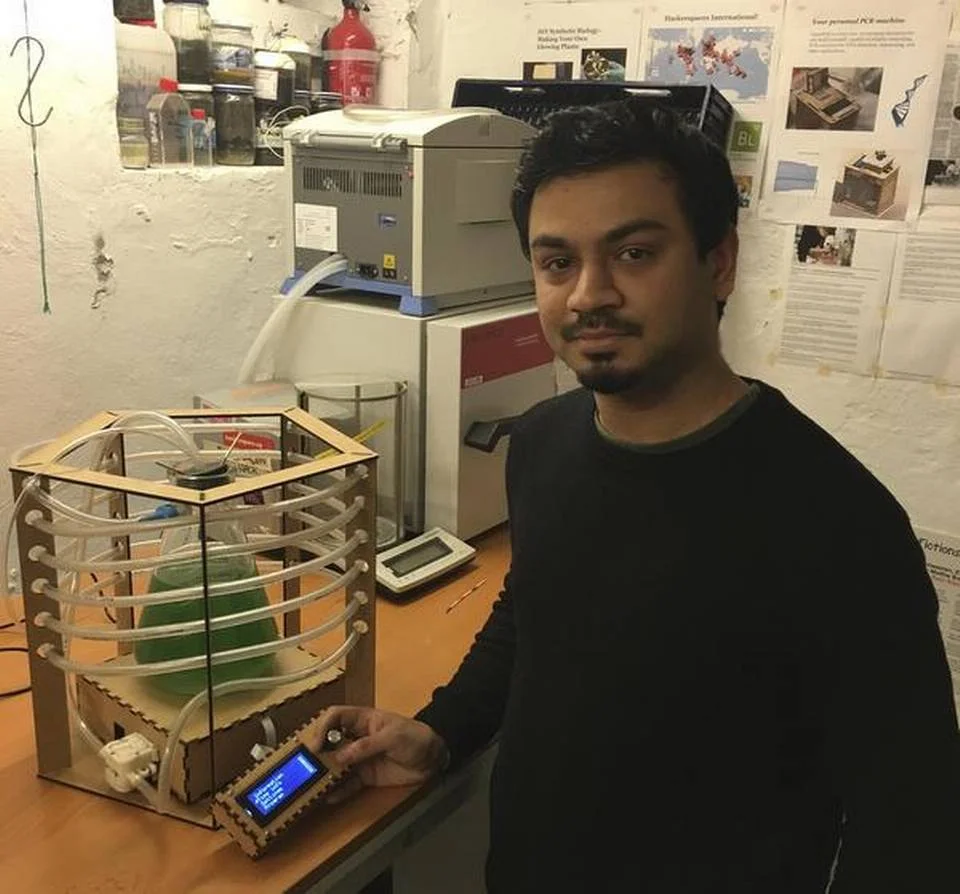

Most of the above technologies will help increase the yield in terms of quantities, but what about the nutrient value? Around the world, companies and researchers are spending time to find the next superfoods, something that our species might not be able to survive without. While some might think cricket (yes, the insect) flour is too extreme, there are those who consume it. Keenan Pinto, an engineer with a background in molecular biology and biotech, has created a bio-reactor for micro-algae after hearing that Spirulina could hold the key to fighting malnutrition. Companies such as Soylent (USA) and Onemeal (Denmark) have been making highly-engineered minimalist food powered by micro-algae, that only need water to make a liquid meal with 20% of daily nutritional value of a person.

NASA’s data has already shown evidence of drastically depleting groundwater resources in North India, and Pinto believes this makes initiatives like the Soil Health Card (a scheme launched by the Government under which farm soil is analysed and crop, nutrient and fertiliser recommendations are given to farmers in the form of a card) the need of the hour.

In the past two years, the image of agriculture and farming technologies has changed from a sickle and plough to computers and vertical farms.

As need grows, our food systems are destined to evolve, and it is our job to evolve with them.