State-of-the-Art Vertical Farms Feed Auburn University Campus

by Kristen Bowman

Last updated: June 02, 2022

Auburn graduate student Kyle Hensarling works with lettuce plants inside a vertical farm shipping container. The plants use red and blue LED lights for photosynthesis.

When Jud Blount said he wanted to grow organic greens outside year-round for his restaurants in the Montgomery area, Dr. Desmond Layne, head of the Department of Horticulture at Auburn University, told him there was almost no chance of doing so.

Organic produce in Alabama is tough, Layne told him, because of the region’s rainfall, bugs and disease.

There was only one way Layne thought it would be possible, and that was vertical farming.

“And he said, ‘What’s that?’ ” said Layne with a laugh.

Today, Blount is an expert in vertical farming, a method of producing food on vertical surfaces, which maximizes crop output in a limited space and allows for total environmental control. In many ways, vertical farming is similar to farming in greenhouses.

But Blount — and now Auburn University — are farming in shipping containers.

In April 2021, the Transformation Garden at Auburn University acquired two Freight Farms, a Boston-based brand of shipping containers outfitted to operate as high-tech, state-of-the-art vertical farms.

These farms use two designated hydroponic methods that optimize water delivery to plants at different stages of growth. Unlike a traditional farm, these plants grow vertically indoors without soil, getting their nutrition from water and light energy from powerful LEDs.

The vertical farms are stationed on the College of Agriculture’s new 16-acre Transformation Garden, which will encompass all of plant-based agriculture — everything from fruits and vegetables to ornamentals, row crops and more.

Auburn’s interest in vertical farming started as a solution to a Campus Dining goal.

Director of Dining Services Glenn Loughridge and Horticulture Associate Professor Dr. Daniel Wells first initiated a partnership between the College of Agriculture and Campus Dining to provide locally grown and sourced food to the campus community.

In 2015, Wells and Loughridge worked together to build the Auburn Aquaponics Project in an integrated plant-fish greenhouse, which uses hydroponics and aquaculture technologies to provide a system in which nutrient-laden wastewater from fish production is used as a food source for plant growth. Fish produced from this effort are served in dining facilities on the Auburn campus.

The vertical farms build on that effort.

“We're in the process of finishing a $26-million dining hall in the center of campus,” Loughridge said. “It has always been foremost in my mind that we would have the opportunity to feature produce grown here on campus in that dining hall. In our biggest location, our biggest asset, we want to bring our A-game.

“This is hyper-local, on-campus sourcing,“ he said. “Can you imagine being a potential student coming to tour, seeing where these products are grown, and then going to eat there? It’s incredible. We truly believe this elevates our dining experience.”

Layne first heard about Freight Farms from a previous colleague of his, Dr. Carl Sams, a professor of crop physiology at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, where Sams and his team operate a Freight Farm.

At the time, Layne and Loughridge were discussing the possibility of building greenhouses at the Transformation Garden to grow produce for the new dining hall.

“I thought, ‘Man, if we can get one of these for our Transformation Garden, we could get into produce production for Campus Dining much faster,’ “Layne said.

He visited Sams in Knoxville, then came back and immediately started talking to Glenn and Daniel about the converted shipping containers.

“There are a few different companies out there doing this,” Layne said. “But Freight Farms is the most sophisticated. They’re the ones who have both the best product on the market and the largest production of these containers. It’s really a best-case scenario.”

Shortly thereafter, Blount — who is president of Vintage Hospitality Group and presiding owner of several restaurants in the Montgomery area — had contacted the College of Agriculture with his idea for year-round, organic, homegrown greens.

“I originally went to see Des about our traditional garden,” Blount said. “During that meeting he said, ‘You need to look into Freight Farms.’ When we got back, we found out Alabama Power had one, the LGM, or Leafy Green Machine model, and was already doing some testing.”

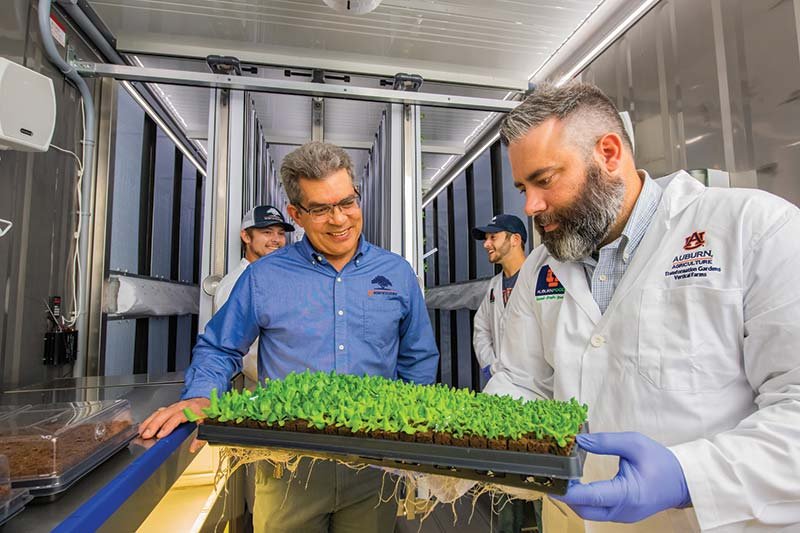

Auburn Associate Professor of Horticulture Dr. Daniel Wells inspects lettuce plants inside a vertical farm shipping container.

Layne and Blount met Cheryl McFarland with Alabama Power to learn about the facility and the data she was collecting.

“They let us come up there and kind of farm for a day and learn about the technology,“ Blount said. “It was a great experience.”

Because Blount is an Alabama Power customer, the company agreed to effectively loan its LGM container to Blount in exchange for data. Shortly thereafter, he bought a second, newer model called the Greenery.

“We stacked the Greenery on top of it,” he said. “Now we have a farm manager, and we’re growing pretty steadily.”

Today, Vintage Hospitality Group runs a robust vertical farming operation called MGM Greens out of the two containers behind one of his restaurants in Cloverdale, where they harvest lettuces and herbs for their restaurants, Vintage Year and Vintage Café, and for retail at the cafe. They also sell the produce at the Madison Farmers Market in downtown Montgomery.

Prior to the arrival of the vertical farms at the Transformation Garden, Wells started teaching a class in vertical farming for horticulture students at Auburn.

“It is a special topics class focused directly on these two shipping container greenery farms,” said Wells, who leads operations of the vertical farms. “They learn the concepts of vertical farming, and then actually as a class set them up and get them going.”

Adam Lenhard, a rising senior majoring in biological agricultural technology management, said Wells’ course has been one of the most influential courses he’s taken at Auburn.

“It has been very helpful, not just in preparation for the arrival of the freights, but also in learning all about new hydroponic technologies and growing techniques,” Lenhard said. “Post-graduation, I plan to continue to work with these types of indoor, LED hydroponic systems. My primary goal after college is to normalize urban hydroponic farming, provide large, consistent yields of fresh vegetables and provide food to those in need who do not have as much access to fresh produce.”

Wells said the containers are outfitted with a complete climate control system, which includes air conditioning and humidity control.

“They’re highly insulated; that’s one of the things Freight Farms, the company, has done,” he said. “So you can put them anywhere from, say, Miami to Ontario, and have the same climate inside that container 365 days a year.”

The containers also have an elaborate lighting system, giving all the light the plants need from two color LEDs.

“We can do any number of colors of lights,” he said. “But it turns out for photosynthesis, plants use mostly red and blue light. What’s neat about that is you can cut out a lot of the other color spectrum, creating far less heat energy. That's very efficient. It means more of the energy used is turned into light than heat.”

The containers also allow for controlled carbon dioxide levels, which accelerates plant growth.

Dr. Desmond Layne, front left, head of Auburn’s Department of Horticulture, and Wells prepare to transplant lettuce plants to the vertical rows in a converted, high-tech shipping container. In the background are students Hensarling and Adam Lenhard.

“Ambient CO2, what you and I are exposed to every day, is about 400 ppm,” he said. “And that’s fine, plants can grow there. But if we boost the CO2 to 1,000 ppm, they’ll grow faster. And because we’re containing the CO2, the plants can really use it. And it’s not dangerous for humans at all.”

Lenhard said he enjoys how the system allows the user to completely manipulate all factors concerning plant growth and development through the proper mixture of nutrients, light and carbon dioxide.

“This is state of the art,” Layne said. “We're talking growing from seed to fork in four to six weeks depending on whether it is lettuce, arugula or another vegetable crop that can grow in there. And we can produce 15 times as much per year as we could outside in the same exact spot.”

Loughridge said he’s excited about the sustainability opportunities the vertical farms provide. The goal is for not one scrap of food to go to waste — anything not used by Campus Dining will either be donated or will return to the Transformation Garden and used in composting.

Lenhard said he also believes that the high amount of water conservation that hydroponics provides can drastically help urban areas reduce their water usage while also providing consumers with fresh veggies harvested only a few miles from their homes.

“Not to mention there is zero shipping,” Loughridge said. “This produce will literally be delivered on a golf cart.”

Shipping issues were a major reason Blount wanted to find another source for greens.

“With lettuce especially, there have been so many romaine recalls,” he said. “We’re growing lettuce 70 feet out our back door. And when we harvest it, it is a living plant. And it remains that way until we serve it.”

Blount credited Layne for helping him build this sustainable aspect of his business. Since the establishment of MGM Greens, he has created a $1,000 scholarship for students in the Department of Horticulture.

Loughridge said the vertical farms are a unique opportunity for Campus Dining to support the academic mission of the university.

“These will be used to for research and will give horticulture students a great educational experience, but it will also have a direct impact on the student experience from a broader perspective,” he said. “Maybe someone who would never consider farming from a traditional sense would take an interest in this. This is a cool opportunity we have to educate in that sense in a broad way across our campus.”

Wells said the vertical farms allow him as an educator to “get down to the necessities.”

“What do plants actually need?” he asked. “Well, they need a few things. They need water, nutrients, space, the proper temperature, CO2, light and specifically the right kind of light and the right intensity of light.”

Loughridge said he is appreciative of the work the College of Agriculture is doing to make on-campus food a reality.

“I mean, this has to operate,“ he said. “Campus Dining made the investments, but we can’t just buy this thing and set it down. There will be students and faculty running it and putting in a lot of hard work to make this possible.”

The results, he said, are entirely worth the effort.

“There are a lot of things that can be easily replicated,” he said. “You can go to a lot of the brands we have on campus and eat the same food at their locations off campus. But this cannot be replicated. The fact that we can source fish, beef, pork and now produce on campus and that students participated in producing these things is a really unique experience for us all.”

Lenhard said he’s eager to see his peers eating the produce grown in the freight farms.

“I am absolutely stoked to have them finally on campus,” he said. “They are providing me and other students on campus with the amazingly unique opportunity to work directly with some of the most advanced type of farming technology available today.”

Layne said the level of investment in greenhouses and hydroponic operations in the U.S. is increasing tremendously, and there are good jobs — in exploding numbers — out there for graduates who have this kind of experience.

“I think about when I was an undergrad,” Layne said. “If we’d had something like this? Gee whiz. What an opportunity.”