Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Growing Up: The Next Frontier In Farming Is Vertical And It Could Cut Canada's Reliance on Imported Food

The spicy mustard micro green begins its short life in a plastic tray of mud, filed away in a germination warehouse at an industrial park on the outskirts of Guelph, Ont. It spends several days in hot and humid darkness, using all its energy to open itself, push through the top layer of soil and unfurl its first two tender leaves

By Jake Edmiston

July 30, 2021

The spicy mustard micro green begins its short life in a plastic tray of mud, filed away in a germination warehouse at an industrial park on the outskirts of Guelph, Ont. It spends several days in hot and humid darkness, using all its energy to open itself, push through the top layer of soil and unfurl its first two tender leaves.

In the germination room, trays of mustard greens all sit on shelves the size of ping pong tables, stacked in rows up to the roof. The plants are ready after about two days and the automated growing system comes to retrieve them, pulling the shelf from its stack and ejecting it through a slot in the warehouse wall.

Soaring crop prices will catch up to consumers

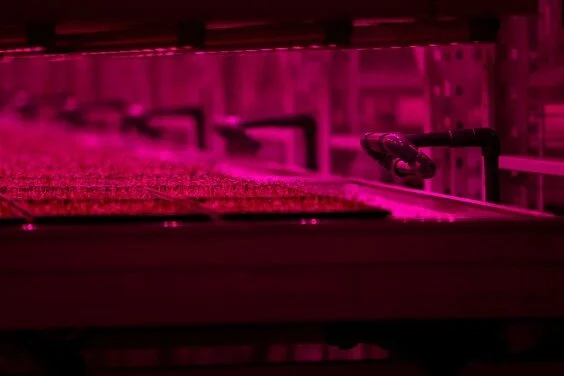

Next, they enter another, larger warehouse, with more shelves stacked up three to four storeys high. Here, the spicy mustard greens feel light for the first time. More than 14,000 LED lamps shine for 14 to 20 hours a day, using only the part of the light spectrum that the plants will need: red and blue. So the warehouse is always a thick, glowing magenta.

After spending two days in the darkness of the germination room, a large flat of spicy mustard greens is moved into the 45,000 square foot vertical farming grow room. PHOTO BY GLENN LOWSON FOR NATIONAL POST

“It’s always a beautiful, spring day,” says Juanita Moore, the executive director of operations at GoodLeaf Farms, which owns this indoor farm in Guelph.

It is incredibly important that these mustard greens survive, not just for GoodLeaf — the company uses them for its Spicy Mustard Medley and Ontario Spring Mix — but also for the long-term stability of the Canadian food system.

Canadian agriculture scholars are warning that the country’s dependence on California and other southern growing regions for fresh produce through the winter has become a national security risk.

“We have to really ask the question, ‘How secure are we?'” said Evan Fraser, director of the University of Guelph’s Arrell Food Institute. “On fruits and vegetables, we are not secure at all.”

On fruits and vegetables, we are not secure at all

EVAN FRASER

The pandemic has given companies and consumers a glimpse at how a global crisis can stymie supply chains and push trading partners to hold back exports. And the extreme drought and wildfires that have threatened California’s vast crop production this summer are just the latest example of a glaring vulnerability in the Canadian food chain, which relied on $11.2-billion worth of imported vegetables, fruits and nuts last year. Farmers in the United States supplied $5.4 billion of that produce — $3.1 billion of which came from California.

“Suddenly this idea that California might not be able to provide food is not that farfetched at all — to the point I’m actively kind of worried about it,” said Lenore Newman, director of the Food and Agriculture Institute at the University of the Fraser Valley. “My worry is, we’re going to start having shortages, because California’s production is going to fall. They don’t have the water.”

Fraser and Newman are part of a growing chorus of professors and industry leaders calling for Canada to stop relying on imports from the U.S. and Mexico and start feeding itself, fast. The best hope to do that, in a country with only five or six good growing months, is to farm indoors.

Juanita Moore, the executive director of operations at GoodLeaf Farm, in Guelph, Ont. PHOTO BY GLENN LOWSON FOR NATIONAL POST

“If the trends continue, we’re in real trouble in North America,” Newman said. “Growing all of this food intensively in one location and moving it all over the continent is not going to work. So we may as well start now. I mean, we should have started five years ago but now is good too.”

This ambition for Canada to grow its own supply of fresh produce in the dead of winter isn’t as implausible as it might sound. The country actually isn’t bad at growing things indoors. Canada’s greenhouse industry is already proficient at growing tomatoes, cucumbers and peppers — to the point that 81.2 per cent of the domestically grown supply of cucumbers come from a greenhouse, according to Statistics Canada.

Historically, the problem with greenhouses has been that they rely on the sun, which means production dips in the darker, winter months. They’re also expensive to heat. Even in summer, the sun can be confounding, as Newman put it. It’s bright one day, obscured by clouds the next. It hits the plants unevenly, making it tougher to produce the sort of uniform crops that the market demands.

The new frontier in farming, Newman said, is to sideline the sun. Advancements in more efficient LED light technology have reduced the cost of growing plants indoors, allowing greenhouses to add lights to augment the sun and effectively extend their growing season.

Cheaper LED technology has also made it possible to farm without any sun at all, in the sort of windowless warehouses “you’d put a Costco in,” Newman said.

LED lights are calibrated to only emit the red and blue of the light spectrum. PHOTO BY GLENN LOWSON FOR NATIONAL POST

This new generation of indoor crop factory can pump out more production per acre because the farmer doesn’t have to worry about sun exposure, droughts or pests. In vertical farming — a common method in the rapidly changing world of closed environment agriculture — the plants are stacked one on top of another, in soil trays or in hydroponic fluid, with LED lights in between.

“You can take a 100-acre farm, compress it into a one-acre farm, and put the rest back into wilderness,” Newman said.

Vertical farms can recycle much of the water they use, and often cost little to heat through winter thanks to warmth from the LED lamps and the plants themselves. But possibly the most important perk, she said, is that “everything will taste better.”

The general vision, for Newman and others, is to have vertical farming operations supplying produce to every region in the country. That would drastically reduce the distance between farm and market, so producers would be able to focus on making varieties that taste good instead of the “wooden” varieties preferred in California because they travel thousands of kilometres without bruising.

Major food and technology companies have been funnelling capital into the indoor farming sector, including French fry giant McCain Foods Ltd.’s roughly $65-million investment to become the single largest shareholder in GoodLeaf.

A sampling of three of the six varieties of leafy greens GoodLeaf cultivates in it’s indoor 45,000 square foot vertical farming operation in Guelph, Ont. PHOTO BY GLENN LOWSON FOR NATIONAL POST

But vertical farming hasn’t quite proven itself to be a profitable option yet, according to one analyst who follows the sector. The building costs for new vertical farms and other large-scale indoor models can range as high as $30 million to $50 million per site. Even when the facilities are built, high energy bills and labour costs make it difficult for the farms to make consistent profits. So most operations focus on crops that grow quickly, can be packed into tight spaces and sell at a premium.

“A lot of these groups are still losing money,” said Steve Hansen, managing director at Raymond James Ltd. “The big challenge is, ultimately, getting to profitability.”

And the goal isn’t just to reach profitability by competing with organic farms on expensive niche products like spicy mustard greens. If the true purpose is to replace Canada’s $11.2-billion reliance on imported produce, indoor operations need to be able to reach the sort of scale that will allow them to compete in the broader fruit and vegetable market. More advancement in LED lighting and automation inside the farms are expected to keep tamping down energy and labour costs.

“The vertical industry is still not quite yet on par with field-grown product,” Hansen said. “They’re getting down there and they’re getting closer but they’re still not there.”

Hansen estimated that globally, capital investments into vertical farms and next-generation indoor farming technology are now in the “billions of dollars” globally.

“It’s become a large sector very quickly,” he said, adding that some established operations are finally starting to reach a scale where they’re able to make a profit. “The development we’ve seen on the indoor space has really happened in the last five years.”

Samples of the latest daily crop of leafy greens are taken for testing before shipping to customers at GoodLeaf. PHOTO BY GLENN LOWSON FOR NATIONAL POST

Still, vertical farms are mostly confined to growing salad greens, which grow within a matter of days and allow the farms to constantly be turning over product.

Branching out to other crops will be a challenge, Hansen said. Tomatoes and cucumbers, for example, can be too tall for vertical farming, which means the farm has to pack fewer rows into the space before hitting the ceiling. (Interestingly, greenhouses actually benefit from the height of cucumbers and tomatoes because they’re essentially vertical farms in and of themselves, Newman said.)

Other vegetables that take months to reach market size mean months’ worth of energy costs have to be included in the price — which Newman suggested could lead to potatoes that cost $20 per pound.

Seed companies, however, have started to turn their attention to breeding varieties of crops that will work well indoors, though the developments are still in the early stages, Hansen said. “Very little effort has been done on short, stubby plants that can produce really high volume, because why would you have ever wanted that?”

Fully grown spicy mustard greens await packaging at GoodLeaf. PHOTO BY GLENN LOWSON FOR NATIONAL POST

The GoodLeaf vertical farm in Guelph is currently able to produce more than 800,000 pounds of micro greens and baby greens annually, though it’s currently producing less than half that. Hospitality and restaurants were intended to make up half the business, so the pandemic-related shutdown in that sector has significantly impacted sales. But the business is able to break even at an output of around 400,000 to 500,000 pounds, selling boxes at $3.99 for micro greens and $4.99 for baby greens in major Ontario supermarkets , including Whole Foods Market Inc., Metro Inc., Loblaw Cos. Ltd.

But even a top capacity of 800,000 pounds of greens is considered light. A new GoodLeaf facility in development in Montreal is expected to reach up to 1.4 million pounds, with an expansion option that would double that output.

“We won’t build farms as small as this one going forward,” GoodLeaf’s Juanita Moore said during a tour of the Guelph plant last week. “Every generation of farm will have kind of perfected it a little bit more.”

Fully grown spicy mustard greens grown at GoodLeaf in Guelph, Ont. PHOTO BY GLENN LOWSON FOR NATIONAL POST

In Guelph, the spicy mustard greens spend about six days in the glowing purple growing room. In that time, they extend themselves to half a finger long. There are hundreds of them per tray, a mix of vibrant greens and purples, all of them never knowing the sun or a bug or a breeze.

The automated lifts move the shelves of plants from one end of the growing warehouse to the other end, a little bit at a time, gradually pushing the mustard greens through the stages of their lives. At the end of it all, there is what appears to be a blue garage door.

When the greens are ready, the blue door cranks open and white light shines in. A worker in an overcoat and hardhat pulls them out of the growing warehouse and into a cold, sterile room with a conveyor belt in the centre.

Here, the greens meet the man who made them. As the move along the conveyor, Cesar Cappa, the head grower at the Guelph plant, stands over them and stares.

Agronomist and head grower Cesar Cappa inspects spicy mustard greens at GoodLeaf Farms in Guelph, Ont. PHOTO BY GLENN LOWSON FOR NATIONAL POST

He calls them by their technical name, cotyledons — the first little leaves to sprout from a seed. He watches for deviations in the cotyledons, aware that any problem means the micro mustard greens could rot and spoil the lettuce when they’re together in the spring mix.

“It can be something small,” he says, dressed in a lab coat.

After the inspection, the mustard greens continue along the conveyor belt toward a vibrating blade at the end of the line. It saws back and forth at high speed, aimed at the necks of the mustard greens. The trays move closer and closer in a slow, inevitable march. Each stem meets the knife and it severs them, clean and quick. From there, the greens are packaged, and the trays of roots and dirt are sent for compost.

Afterward, in an open-concept office connected to the vertical farm, Moore passed around paper plates of micro greens and lettuces grown at the facility. Everything tasted of the outdoors.

“It takes me right back to my grandpa’s farm,” she said.

Lead Photo: A tray of spicy mustard greens grown at GoodLeaf’s vertical farm in Guelph, Ont. PHOTO BY GLENN LOWSON FOR NATIONAL POST

US Farming Is Tasteless, Toxic And Cruel

and its monstrous practices have no place here: Radio 4’s veteran food presenter Sheila Dillon decries ministers’ dangerous plans

By SHEILA DILLON FOR THE DAILY MAIL

19 September 2020

And its monstrous practices have no place here: Radio 4’s veteran food presenter Sheila Dillon decries ministers’ dangerous plans

British farming and food production are a remarkable success story. In recent years, this sector has been at the forefront of a revolution that’s transformed the quality of our food — and acted as a guardian of our countryside.

Through the vision and dedication of our farmers, Britain is increasingly a global leader in animal welfare, environmental protection, and high standards of produce. Now all these achievements are at mortal risk. As we prepare to leave the European Union at the end of this year, our impressive agricultural system could soon be wrecked by ruthless competition and a flood of cheap imports.

The most serious threat comes from the U.S., whose vast and unwieldy farming industry is far less regulated than ours.

In the name of efficiency, it has built a highly mechanised, intensive, and shockingly cruel approach which keeps animals in conditions so appalling it’s hard for us in the UK to grasp. Meanwhile, an arsenal of chemicals that are banned here are also deployed on these poor creatures.

It is not the sort of produce that should be allowed to swamp our own. When Brexit supporters spoke of ‘taking back control’, they did not envisage the destruction of British farming caused by mass-produced goods soaked in chlorine and cruelty.

In an attempt to prevent this grim eventuality, a last-ditch battle is under way at Westminster aiming to establish essential safeguards in post-Brexit Britain.

As the Agriculture Bill — which sets out a new domestic, post-Brexit alternative to the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy — makes its way through Parliament, MPs in the Commons and peers in the Lords have tried to impose amendments to keep Britain’s high standards of animal husbandry and environmental care. So far the Government has rejected all such proposals. Desperate to reach a trade deal, ministers seem unwilling to block the hugely influential U.S. food and agriculture lobby from gaining access to our market.

Their argument is that, in the brave new world of deregulation, consumers will enjoy more choice and, crucially, will have access to ‘cheap’ food. But cheapness will come at a huge cost to our health, our countryside, our rural economy, and our animals.

The reality is that choice will be restricted — because British farmers and producers will find it impossible to compete. From the supermarkets to takeaways, this ugly juggernaut of American food will sweep all before it.

The Agriculture Bill is about to go to the final stage of its passage through Parliament. There is one last chance for legislators to stop a free-for-all from which our agriculture would emerge the loser.

As someone who has covered the food industry for 20 years presenting The Food Programme on BBC Radio 4, I am deeply alarmed at the prospect of the advances British food has made in recent decades going into reverse.

Before COVID, British food was flourishing as never before. I think of the surge in high-quality bakeries, of our farmhouse cheeses beating rivals across the world — we produce more than France.

Even McDonald’s UK now uses free-range eggs and organic milk and recently won an RSPCA award for its animal welfare standards. I need hardly say it’s not how McDonald’s operates in the U.S.

It’s all part of Britain’s deep and enduring compassion for animals. We have 25 million free-range hens here, more than any other country — and more free-range pigs than anywhere in Europe.

In frequent talks with farmers, I have been struck by how they see themselves, not just as producers, but as custodians of the land, a vital role they fill with imaginativeness in an age of mounting concern about climate change.

The U.S. farming model is completely different. Its aim is not to work with nature but to dominate it. Industrialised and chemicalised, the entire system is a monument to the denial of biology.

I am not in any way anti-American — I’ve lived across that wonderful country in Indiana, California, Massachusetts, and New York. I’m married to an American: my son and his family live in Pennsylvania.

It’s precisely because I visit regularly, and have seen at first hand the harshness of U.S. food production, that I feel so strongly.

The ‘chlorinated chicken’ has rightly become a symbol of U.S. farming at its worst, but few ask why poultry has to be washed in chlorine before it can be sold. It is because the birds are kept in such over-crowded squalor and so pumped with chemicals during their brief, unfortunate lives.

The same applies throughout American industry. Even the British Government’s farming Secretary George Eustice has admitted U.S. animal welfare law is ‘woefully deficient’. Pigs are reared in grotesquely inhumane battery farms. More than 60 million are treated with the antibiotic Carbadox, which promotes growth and is rightly banned in the UK.

Similarly, U.S. cattle are fed steroid hormones to speed growth by 20 percent — the use of such chemicals has been illegal in Britain and the EU since 1989. And as the cattle are kept in vast confined feeding pens, they need regular antibiotics.

Incredibly, some staff processing carcasses at huge meatpacking plants wear nappies because they are not allowed time off to go to the lavatory. In arable production, pesticides are used on a scale far beyond anything in Britain. In recent decades, the U.S. has banned or controlled just 11 chemicals in food, cosmetics, and cleaning products — the EU has banned 1,300.

Polar opposites: Cows in a British field, and in beef pens in Texas

In U.S. farming there’s almost no effort to mitigate climate change yet here the National Farmers’ Union is committed to achieving zero carbon production by 2040. What will happen to that commitment if cheap U.S. food floods in?

The U.S. genetically modified crops to be resistant to Roundup weedkiller — but after weeds grew resistant to Roundup and flourished, one U.S. farmer told me proudly crops were now engineered to be resistant to the infamous Agent Orange, a defoliant used by the U.S. military to kill vegetation in the Vietnam War.

Environmental devastation and health problems — including disabilities to as many as a million people — were caused in Vietnam by Agent Orange. Is this a road we want to go down in Britain?

The so-called cheapness of American produce is a delusion. These farming methods carry a heavy price in quality and health. A battery chicken is tasteless compared to an organic one, just as factory-farmed salmon has nothing of the flavour of wild.

Cheap, low-quality foods have brought with them disturbing health problems including obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

The coronavirus crisis proved the need for resilient supply lines. But that cannot be achieved if we ruin our own domestic agricultural system and become reliant on imported food.

In World War II, when the survival of the nation was imperilled, the Government attached huge importance to domestic food output, reflected in the propaganda campaign ‘Dig for Victory’ and the Women’s Land Army. We need that collective spirit today.

It would be stupidity beyond measure to obliterate our farming industry for a short-term, unbalanced trade deal with the U.S.

A trade deal without agricultural safeguards would be a calamity for British farming and our prosperity. One in eight jobs in Britain is in food supply, while food exports brought in £9.6 billion to the economy. All that will be lost if cut-throat competition prevails.

And a vital part of our heritage will also be lost. From the robust imagery of John Bull as a yeoman squire to William Blake’s Jerusalem, with its evocation of our ‘green and pleasant land’, the countryside has always held a central place in our national soul. It must not be sacrificed on the altar of illusory cheapness or trans-Atlantic subservience.

Lead photo: It’s all part of Britain’s deep and enduring compassion for animals. We have 25 million free-range hens here, more than any other country — and more free-range pigs than anywhere in Europe

Sheila Dillon presents BBC Radio 4’s The Food Programme.

US Farming Is Tasteless, Toxic And Cruel

and its monstrous practices have no place here: Radio 4’s veteran food presenter Sheila Dillon decries ministers’ dangerous plans

By SHEILA DILLON FOR THE DAILY MAIL

19 September 2020

And its monstrous practices have no place here: Radio 4’s veteran food presenter Sheila Dillon decries ministers’ dangerous plans

British farming and food production are a remarkable success story. In recent years, this sector has been at the forefront of a revolution that’s transformed the quality of our food — and acted as a guardian of our countryside.

Through the vision and dedication of our farmers, Britain is increasingly a global leader in animal welfare, environmental protection, and high standards of produce. Now all these achievements are at mortal risk. As we prepare to leave the European Union at the end of this year, our impressive agricultural system could soon be wrecked by ruthless competition and a flood of cheap imports.

The most serious threat comes from the U.S., whose vast and unwieldy farming industry is far less regulated than ours.

In the name of efficiency, it has built a highly mechanised, intensive, and shockingly cruel approach which keeps animals in conditions so appalling it’s hard for us in the UK to grasp. Meanwhile, an arsenal of chemicals that are banned here are also deployed on these poor creatures.

It is not the sort of produce that should be allowed to swamp our own. When Brexit supporters spoke of ‘taking back control’, they did not envisage the destruction of British farming caused by mass-produced goods soaked in chlorine and cruelty.

In an attempt to prevent this grim eventuality, a last-ditch battle is under way at Westminster aiming to establish essential safeguards in post-Brexit Britain.

As the Agriculture Bill — which sets out a new domestic, post-Brexit alternative to the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy — makes its way through Parliament, MPs in the Commons and peers in the Lords have tried to impose amendments to keep Britain’s high standards of animal husbandry and environmental care. So far the Government has rejected all such proposals. Desperate to reach a trade deal, ministers seem unwilling to block the hugely influential U.S. food and agriculture lobby from gaining access to our market.

Their argument is that, in the brave new world of deregulation, consumers will enjoy more choice and, crucially, will have access to ‘cheap’ food. But cheapness will come at a huge cost to our health, our countryside, our rural economy, and our animals.

The reality is that choice will be restricted — because British farmers and producers will find it impossible to compete. From the supermarkets to takeaways, this ugly juggernaut of American food will sweep all before it.

The Agriculture Bill is about to go to the final stage of its passage through Parliament. There is one last chance for legislators to stop a free-for-all from which our agriculture would emerge the loser.

As someone who has covered the food industry for 20 years presenting The Food Programme on BBC Radio 4, I am deeply alarmed at the prospect of the advances British food has made in recent decades going into reverse.

Before COVID, British food was flourishing as never before. I think of the surge in high-quality bakeries, of our farmhouse cheeses beating rivals across the world — we produce more than France.

Even McDonald’s UK now uses free-range eggs and organic milk and recently won an RSPCA award for its animal welfare standards. I need hardly say it’s not how McDonald’s operates in the U.S.

It’s all part of Britain’s deep and enduring compassion for animals. We have 25 million free-range hens here, more than any other country — and more free-range pigs than anywhere in Europe.

In frequent talks with farmers, I have been struck by how they see themselves, not just as producers, but as custodians of the land, a vital role they fill with imaginativeness in an age of mounting concern about climate change.

The U.S. farming model is completely different. Its aim is not to work with nature but to dominate it. Industrialised and chemicalised, the entire system is a monument to the denial of biology.

I am not in any way anti-American — I’ve lived across that wonderful country in Indiana, California, Massachusetts, and New York. I’m married to an American: my son and his family live in Pennsylvania.

It’s precisely because I visit regularly, and have seen at first hand the harshness of U.S. food production, that I feel so strongly.

The ‘chlorinated chicken’ has rightly become a symbol of U.S. farming at its worst, but few ask why poultry has to be washed in chlorine before it can be sold. It is because the birds are kept in such over-crowded squalor and so pumped with chemicals during their brief, unfortunate lives.

The same applies throughout American industry. Even the British Government’s farming Secretary George Eustice has admitted U.S. animal welfare law is ‘woefully deficient’. Pigs are reared in grotesquely inhumane battery farms. More than 60 million are treated with the antibiotic Carbadox, which promotes growth and is rightly banned in the UK.

Similarly, U.S. cattle are fed steroid hormones to speed growth by 20 percent — the use of such chemicals has been illegal in Britain and the EU since 1989. And as the cattle are kept in vast confined feeding pens, they need regular antibiotics.

Incredibly, some staff processing carcasses at huge meatpacking plants wear nappies because they are not allowed time off to go to the lavatory. In arable production, pesticides are used on a scale far beyond anything in Britain. In recent decades, the U.S. has banned or controlled just 11 chemicals in food, cosmetics, and cleaning products — the EU has banned 1,300.

Polar opposites: Cows in a British field, and in beef pens in Texas

In U.S. farming there’s almost no effort to mitigate climate change yet here the National Farmers’ Union is committed to achieving zero carbon production by 2040. What will happen to that commitment if cheap U.S. food floods in?

The U.S. genetically modified crops to be resistant to Roundup weedkiller — but after weeds grew resistant to Roundup and flourished, one U.S. farmer told me proudly crops were now engineered to be resistant to the infamous Agent Orange, a defoliant used by the U.S. military to kill vegetation in the Vietnam War.

Environmental devastation and health problems — including disabilities to as many as a million people — were caused in Vietnam by Agent Orange. Is this a road we want to go down in Britain?

The so-called cheapness of American produce is a delusion. These farming methods carry a heavy price in quality and health. A battery chicken is tasteless compared to an organic one, just as factory-farmed salmon has nothing of the flavour of wild.

Cheap, low-quality foods have brought with them disturbing health problems including obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

The coronavirus crisis proved the need for resilient supply lines. But that cannot be achieved if we ruin our own domestic agricultural system and become reliant on imported food.

In World War II, when the survival of the nation was imperilled, the Government attached huge importance to domestic food output, reflected in the propaganda campaign ‘Dig for Victory’ and the Women’s Land Army. We need that collective spirit today.

It would be stupidity beyond measure to obliterate our farming industry for a short-term, unbalanced trade deal with the U.S.

A trade deal without agricultural safeguards would be a calamity for British farming and our prosperity. One in eight jobs in Britain is in food supply, while food exports brought in £9.6 billion to the economy. All that will be lost if cut-throat competition prevails.

And a vital part of our heritage will also be lost. From the robust imagery of John Bull as a yeoman squire to William Blake’s Jerusalem, with its evocation of our ‘green and pleasant land’, the countryside has always held a central place in our national soul. It must not be sacrificed on the altar of illusory cheapness or trans-Atlantic subservience.

Lead photo: It’s all part of Britain’s deep and enduring compassion for animals. We have 25 million free-range hens here, more than any other country — and more free-range pigs than anywhere in Europe

Sheila Dillon presents BBC Radio 4’s The Food Programme.