Kimbal Musk's Tech Revolution Starts With Mustard Greens

A leafy green grows in Brooklyn. (Photo by Natalie Keyssar)

The other Musk is leading a band of hipster Brooklyn farmers on a mission to overthrow Big Ag.

Farmers have always had a tough time. They have faced rapacious bankers, destructive pests, catastrophic weather, and relentless pressure to cut prices to serve huge grocery suppliers.

And now they must compete with Brooklyn hipsters. Hipsters with high-tech farms squeezed into 40-foot containers that sit in parking lots and require no soil, and can ignore bad weather and even winter.

Follow Backchannel: Facebook | Twitter

No, the 10 young entrepreneurs of the “urban farming accelerator” Square Roots and their ilk aren’t going to overthrow big agribusiness — yet. Each of them has only the equivalent of a two-acre plot of land, stuffed inside a container truck in a parking lot. And the food they grow is decidedly artisanal, sold to high-end restaurants and office workers who are amenable to snacking on Asian Greens instead of Doritos. But they are indicative of an ag tech movement that’s growing faster than Nebraska corn in July. What’s more, they are only a single degree of separation from world-class disrupters Tesla and SpaceX: Square Roots is co-founded by Kimbal Musk, sibling to Elon and board member of those two visionary tech firms.

Kimbal’s passion is food, specifically “real” food — not tainted by overuse of pesticides or adulterated with sugar or additives. His group of restaurants, named The Kitchen after its Boulder, Colorado, flagship, promotes healthy meals; a sister foundation creates agricultural classrooms that center a teaching curriculum around modular gardens that allow kids to experience and measure the growing process. More recently, he has been on a crusade to change the eating habits of the piggiest American cities, beginning with Memphis.

“This is the dawn of real food,” says Musk. “Food you can trust. Good for the body. Good for farmers.”

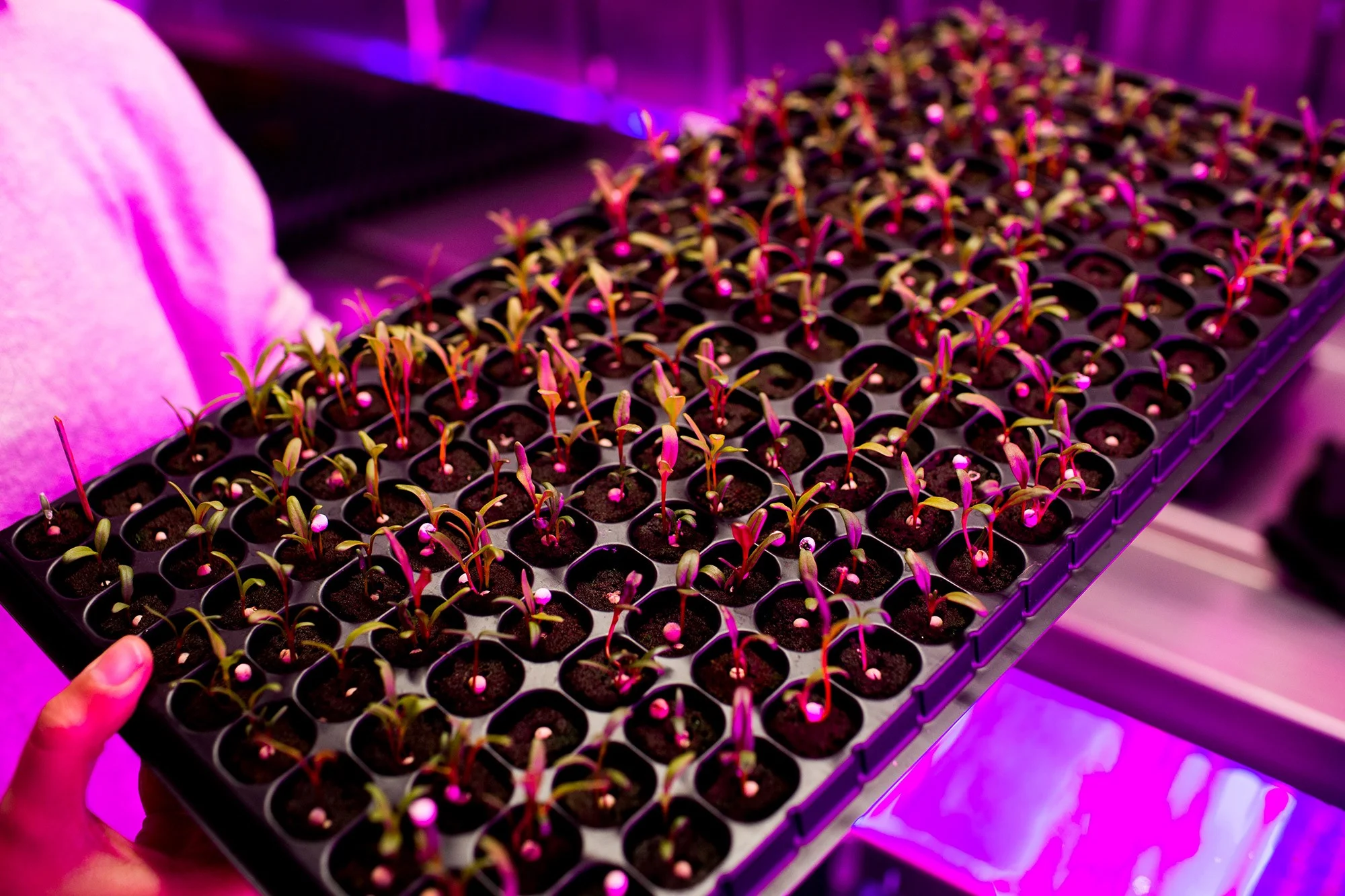

Square Roots is an urban farming initiative which allows “entrepreneurs” to grow organic, local vegetables indoors at its new site in Bed Stuy, Brooklyn. (Photo by Natalie Keyssar)

Square Roots is one more attempt to extend the “impact footprint” of The Kitchen, says its CEO and co-founder Tobias Peggs, a longtime friend of Musk’s. (Musk himself is executive chair.) Peggs is a lithe Brit with a doctorate in AI who has periodically been involved in businesses with Musk, along with some other ventures, and wound up working with him on food initiatives. Both he and Musk claim to sense that we’re at a moment when a demand for real food is “not just a Brooklyn hipster food thing,” but rather a national phenomenon rising out of a deep and wide distrust of the industrial food system, a triplet that Peggs enunciates with disdain. People want local food, he says. And when he and Musk talk about this onstage, there are often young people in the audience who agree with them but don’t know how to do something about it. “In tech, if I have an idea for a mobile app, I get a developer in the Ukraine, get an angel investor to give me 100k for showing up, and I launch a company,” Peggs says. “In the world of real food, there’s no easy path.”

The company is headquartered in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant, right next to the Marcy Projects, which were the early stomping grounds of Jay Z. It’s one of over 40 food-related startups housed in a former Pfizer chemicals factory, which at one time produced a good chunk of the nation’s ammonia. (Consider its current role as a hub of crunchy food goodness as a form of penance.) Though Peggs’ office and a communal area and kitchen are in the building, the real action at Square Roots is in the parking lot. That’s where the company has plunked down ten huge shipping containers, the kind you try to swerve around when they’re dragged by honking 18-wheel trucks. These are the farms: $85,000 high-tech growing chambers pre-loaded with sensors, exotic lighting, precision plumbing for irrigation, vertical growing towers, a climate control system, and, now, leafy greens.

Musk and Peggs (center) with the Brooklyn growers. (Photo by Steven Levy)

Each of these containers is tended by an individual entrepreneur, chosen from a call for applicants last summer that drew 500 candidates for the 10 available slots. Musk and Peggs selected the winners by passion and grit as opposed to agricultural acumen. Indeed, the resumes of these urban farmers reveal side gigs like musician, yoga teacher, and Indian dance fanatic. (The company does have a full-time farming expert and other resources to help with the growing stuff.) After all, the idea of Square Roots is not about developing farm technology, but rather about training people to make a business impact by distributing, marketing, and profiting off healthy food. “You can put this business in a box — it’s not complicated,” says Musk. “The really hard part is how to be an entrepreneur.”

Peggs gave me a tour late last year as the first crops were maturing. The farmers themselves were not in attendance. Every season is growing season in the ag tech world, but once you’ve planted and until you harvest, your farms can generally be run on an iPhone, and virtually all the operations are cloud-based. Peggs unlocked the back of a truck and lifted up the sliding door to reveal racks of some sort of leafy greens. Everything was bathed in a hot pink light, making it look like a set of a generic sci-fi movie. (That’s because the plants need only the red-blue part of the color spectrum for photosynthesis.) Also, the baby plants seemed to be growing sideways. “Imagine you’re on a two-dimensional field and you then tip the field on its side and hang the seedlings off,” Peggs says. “That means you’re able to squeeze the equivalent of a two-acre outdoor field inside a 40-foot shipping container.”

Square Roots didn’t have to invent this technology: You can pretty much buy off-the-shelf indoor farming operations. We owe this circumstance to what once was the dominant driver of inside-the-box ag tech: the cultivation of marijuana. The advances concocted by high-end weed wizards are now poised to power a food revolution. “Cannabis is to indoor growing as porn was to the internet,” says Pegg.

Using light, temperature, and other factors easily controlled in the nano-climate of a container farm, it’s even possible to design taste. If you know the conditions in various regions at a given time, you can replicate the flavors of a crop grown at a specific time and place. “If the best basil you ever tasted was in Italy in the summer of 2006, I can recreate that here,” Peggs says.

So far, the Square Roots entrepreneurs haven’t achieved that level of precision—but they have jiggered the controls to make tasty flora. And they’ve used imagination in selling their crops. One business model that’s taken off has the farmers hand-delivering $7 single-portion bags of greens to office workers at their desks, so the buyers can nibble on them during the day, like they would potato chips. Others supply high-end restaurants. Occasionally Square Roots will run its version of a farmer’s market at the Flushing Avenue headquarters or other locations, such as restaurants in off hours.

The prices are higher than you’d find in an average supermarket, or even at Whole Foods. Peggs doesn’t have to reach far for an analogy — the cost of the first Teslas, two-seaters whose six-figure pricetags proved no obstacle for eager buyers. “Think of it as the roadster of lettuce,” he says. Later, Musk himself will elaborate: “The passion the entrepreneurs put into it makes the food taste 10 times better.”

One selling point of the food is its hyperlocal-ness — grown in the neighborhood where it’s consumed. The Square Roots urban growers often transport their harvest not by truck but subway. While this circumstance does piggyback on the recent mania for crops grown in local terroir, I wonder aloud to Peggs whether food produced in a high-tech container in a dense urban neighborhood, even if it’s a few blocks away, has the same appeal as fresh-off-the-farm crops that are grown on actual farms. In, like, dirt. Can you tell by a grape’s taste if it came from Williamsburg or Crown Heights? I’m having a bit of trouble with that.

Peggs brushes off my objection. Local is local. It’s about transparency and connectedness. “Here’s what I know,” he says. “Consumers are disconnected from the food, disconnected from the people who grow it. We’re putting a farm four stops on the subway from SoHo, where you can know your farmer, meet your farmer. You can hang out and see them harvest. So whether the grower is a no-till soil-based rural farmer or a 23-year or dream-big entrepreneur in a refurbished shipping container, both are on the same side, fighting a common enemy, which is the industrial food system.”

Plants grow in Nabeela Lakhani’s container. (Photo by Natalie Keyssar)

Square Roots is far from the only operation signing on to an incipient boom in indoor agriculture. Indeed, ag tech is now a hot field for investors — maybe not so much that founders can get $100k for just showing up, but big enough that some very influential billionaires have ponied up their dollars. I spoke recently to Matt Barnard, the CEO of a company called Plenty. His investors include funds backed by Eric Schmidt and Jeff Bezos. In its test facility in a South San Francisco warehouse, Plenty is developing techniques that it hopes will bring high-tech agriculture to the shelves of the Walmarts of the world.

In Barnard’s view, indoor agriculture is the only way we will feed the billions of new humans predicted to further crowd our planet. “We have no choice,” he says. “We are out of acreage [of productive land] in many places. In the US, the percentage of imported produce keeps growing.”

Going indoors and using technology, he says, will not only give us more food, but also better food, “beyond organic quality.”

As its name implies, Plenty wants to scale into a huge company that will feed millions. Barnard, who previously built technology infrastructure for the likes of Verizon and Comcast, has a vision of hundreds of distribution hubs — think Amazon or Walmart, near every population center, putting perhaps 85 percent of the world’s population within a short drive of a center. Without having to optimize crops so they can be driven thousands of miles from farm to grocery store, almost all food will be local. “We’ll have food for people, not for trucks,” he says. “This enables us to grow from libraries of seeds that have never been grown commercially, that will taste awesome. These will be the strawberries that beforehand, you only got from your grandmother’s yard.”

As far as that goal goes — better-than-organic crops grown near where you consume them — Plenty is aligned with Square Roots. But Barnard insists that the key element in ag tech will be scale. “Growing food inside is the easy part,” says Barnard. The hardest part is to make food that seven billion people can eat, at prices that fit in everybody’s grocery budget.”

Green Acres? Try Pink Acres! Pictured here, Square Roots farms — and in background is Jay Z’s boyhood home, the Marcy Projects. (Photo by Natalie Keyssar)

Peggs and Musk themselves are interested in scale. They see Square Roots as grass roots — seedlings of a movement that will blossom into a profusion of food entrepreneurs who subscribe to their vision of authentic, healthy chow grown locally.

Earlier this year, Musk dropped by Square Roots to show it off to investors and friends, and then to give a pep talk over lunch to the entrepreneurs. Midway through their year at Square Roots, these urban ag tech pioneers were still enthusiastic as they described their wares. Nabeela Lakhani, who studied nutrition and public health at NYU, described how her distinctive variety of spicy mustard greens had gained a local following. “People lose their minds over this,” she says. Electra Jarvis, who hails from the Bronx, has done a land-office business in selling 2.5-ounce packages of her Asian Greens for $7 each to office workers. (That’s almost $50 a pound.) Maxwell Carmack, describing himself as a lover of nature and technology, packages a variety of his “strong spinach.”

After a tour of the parking lot — the 21st century lower forty — the guests leave and Musk schools the farmer-entrepreneurs as they feast on a spread of sandwiches and salads featuring their recently harvested products. It’s a special treat to hear from the cofounder, as he not only has that famous surname, but also is himself a superstar in the healthy food movement, as well as an entrepreneur who’s done well in his own right. And unlike his brother, who can sometime be dour, Kimbal is a social animal who lights up as he engages people on his favorite subjects.

“Are you making money?” he asks them. Most of them nod affirmatively. Only recently, they have discovered that the “Farmer2Office” program — the one that essentially sells tasty rabbit food for caviar prices — can be a big revenue generator, with 40 corporate customers so far. Peggs guesses that by the end of the year some of the farmers might be generating a $100,000-a-year run rate (the entrepreneurs pay operating expenses and share revenue with the company). But of course, because Square Roots is covering the capital costs of the farms themselves, it’s hard to claim they’re reaping huge profits.

Musk, in cowboy hat, gets back to his roots. Peggs is standing behind him. (Photo by Steven Levy)

“It’s a grind building a business,” Musk tells them. “It’s like chewing glass. If you don’t like a glass sandwich, stop right now.” The young ag tech growers stare at him, their forks frozen in mid-air until he continues. “But you choose your destiny, choose the people around you,” Musk continues.

And then he speaks of the opportunity for Square Roots. This year may only be the first of many cycles where he and Peggs pick 10 new farmers. Within a few years, he will have a small army of real-food entrepreneurs, devoted to disrupting the industry with authentic crops, grown locally. “The real problem is how to reach everybody,” he says. “We’re not going to solve that problem at Square Roots. But there are so many ways you can impact the world when you’re out of here.”

“Whole Foods is stuck in bricks and mortar,” he continues. “We can become the Amazon of real food. If not us, one of you guys. But someone is going to solve that problem.”

The urban farmers look energized. Lunch continues. The salad, fresh from the parking lot, is delicious.

Steven LevyFollow

Editor of Backchannel. Also, I write stuff. Apr 14,2017

Creative Art Direction by Redindhi Studio

Photography by Natalie Keyssar / Steven Levy