Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Vertical Farming Startup Oishii Raises $50m In Series A Funding

“We aim to be the largest strawberry producer in the world, and this capital allows us to bring the best-tasting, healthiest berry to everyone.”

By Sian Yates

03/11/2021

Oishii, a vertical farming startup based in New Jersey, has raised $50 million during a Series A funding round led by Sparx Group’s Mirai Creation Fund II.

The funds will enable Oishii to open vertical strawberry farms in new markets, expand its flagship farm outside of Manhattan, and accelerate its investment in R&D.

“Our mission is to change the way we grow food. We set out to deliver exceptionally delicious and sustainable produce,” said Oishii CEO Hiroki Koga. “We started with the strawberry – a fruit that routinely tops the dirty dozen of most pesticide-riddled crops – as it has long been considered the ‘holy grail’ of vertical farming.”

“We aim to be the largest strawberry producer in the world, and this capital allows us to bring the best-tasting, healthiest berry to everyone. From there, we’ll quickly expand into new fruits and produce,” he added.

Oishii is already known for its innovative farming techniques that have enabled the company to “perfect the strawberry,” while its proprietary and first-of-its-kind pollination method is conducted naturally with bees.

The company’s vertical farms feature zero pesticides and produce ripe fruit all year round, using less water and land than traditional agricultural methods.

“Oishii is the farm of the future,” said Sparx Group president and Group CEO Shuhei Abe. “The cultivation and pollination techniques the company has developed set them well apart from the industry, positioning Oishii to quickly revolutionise agriculture as we know it.”

The company has raised a total of $55 million since its founding in 2016.

Inside The GMO Law: What Needs To Be Labeled And Why It Matters

The regulations state that manufacturers can voluntarily disclose GMOs if a product contains some of these highly refined ingredients or has a lower concentration of biologically engineered material, which GMO advocates cheer and consumer organizations caution

Highly refined ingredients and the "BE" acronym are out, according to regulations issued in December. The food industry and consumer groups are split on how effective the new measure will be.

AUTHOR Megan Poinski@meganpoinski

Now that the final GMO labeling regulations have been rolled out, what is going to bear the new seal that certifies a product is derived from bioengineering?

The answer: Not as many products as advocates for the labeling might have thought. It's been estimated that up to 75% of the products in a grocery store are made with ingredients derived from crops that were genetically modified. According to the regulations, items that contain highly refined ingredients don't have to be labeled.

Additionally, to require a label, a product needs to have at least 5% bioengineered material, which is a higher concentration amount than most other countries that have GMO labels.

The regulations state that manufacturers can voluntarily disclose GMOs if a product contains some of these highly refined ingredients or has a lower concentration of biologically engineered material, which GMO advocates cheer and consumer organizations caution.

The new labeling requirements, which most manufacturers must implement starting in 2020, were viewed by some analysts as fair.

"They balance consumers' request for more information with a labeling approach that is based on facts, practicality and common sense, rather than politics and fear," Sean McBride of DSM Strategic Communication told Food Dive in an email. "No one side got everything it wanted, and there will be special interest skirmishes in the 116th Congress and beyond over this, but for now, we have a clear flight path to providing consumers with the transparency they want and deserve.”

There are many other aspects of the regulations those in the industry appreciate and despise. But the time for changes has passed. Manufacturers now need to work on ensuring that their labels comply with the new guidelines. According to the regulations, manufacturers may put their labels to the test as soon as this month.

Credit: Okanagan Specialty Fruits

What needs to be labeled?

While the new regulations outlined the symbols and terms that will be used, what needs to be labeled did not change during the rulemaking process. Meat, poultry and egg products by themselves are not included in the disclosure, which is stated clearly in the law. Neither are multi-ingredient products that have these items as their first ingredients, such as a canned stew with beef broth.

The final rule lays out a much more nuanced — and consequential — point. Many crops that become food ingredients are GMO, but they go through a refining process to become useful ingredients. That process often destroys the genetic material in the ingredients. One of the largest questions for the final rulemaking was whether these ingredients needed to be labeled as GMOs.

Companies and trade organizations were split on the issue. In its comments on the rule, the Grocery Manufacturers Association said about 90% of the nation's corn, soybean and sugar beet crops are genetically modified. If the products using refined versions of those crops do not have to be labeled as GMO, it estimated 78% fewer products would have to be disclosed under federal law.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture decided not to require the disclosure because the initial law said GMO food needs to contain modified genetic material. If it cannot be detected, it is not there. And because the initial law also does not say anything about classifying some of these ingredients from GMO crops as "highly refined," the final rule does not take on this classification of definition.

Consumer advocates who oppose GMOs were strident in their disapproval of the ruling.

"The USDA has betrayed the public trust by denying Americans the right to know how their food is produce," Andrew Kimbrell, executive director at Center for Food Safety, said in a written statement. "Instead of providing clarity and transparency, they have created large scale confusion and uncertainty for consumers, food producers, and retailers."

The Consumer Federation of America said in a statement that exempting refined products from disclosure is "inadequate."

However, many major food manufacturers — including Campbell Soup, Mars, Danone, Kellogg, Coca-Cola and Unilever — have been voluntarily disclosing GMOs, heavily refined or not, since the mandatory labeling issue was first debated several years ago.

The USDA also will maintain a list of crops that are definitively GMO that are produced anywhere in the world. This list helps food manufacturers know which ingredients they need to disclose, but it is not exhaustive and will be updated periodically. The regulation gives manufacturers 18 months to update their labels after an ingredient is added to the list.

Currently, the following crops are defined as GMO: alfalfa, Arctic apple, canola, corn, cotton, Bt-Begun eggplant, ringspot virus-resistant varieties of papaya, pink pineapple, potato, AquAdvantage salmon, soybean, summer squash and sugarbeet.

The regulation also indicates where and how on-package disclosure is required. It needs to be seen under ordinary shopping conditions, and must be located near other information on the label that features the manufacturer's name and location. The disclosure can be through text, smartphone-scannable digital links, URLs, a telephone number, text messages or the "BE" symbol. If a digital link is used, it needs to have the words "scan here for more food information" next to it.

While there were several options for the BE symbol in the preliminary framework, the final rules set one that has a round picture of a plant growing in a sunny farm field. A green circle around the picture features the word "BIOENGINEERED" or "DERIVED FROM BIOENGINEERING." There is no BE acronym — the regulations say many consumers did not know what it stood for — and an earlier logo with a smiley face was abandoned.

Credit: Flickr, Dave Herholz

Will it be useful for consumers?

Since it's been known that scientists and food companies were working with ingredients from lab-modified plants, many consumers have wanted to know if they are eating them. While the predominant scientific consensus is GMO food is safe and items made with these ingredients are just as nutritious as their counterparts, consumers value transparency.

Are they getting it from this labeling law? Reactions are mixed.

"No one should be surprised that the most anti-consumer, anti-transparency administration in modern times is denying Americans basic information about what’s in their food and how it’s grown," the Environmental Working Group said in a written statement. The organization takes issue with several aspects of the law, mainly the ruling on not having to label highly refined ingredients as GMOs. EWG has added "Certrified GMO-free" — using verifications from the Non-GMO Project — as a category on its food information website.

The Grocery Manufacturers Association focused on the cohesiveness of the labeling regulations. The federal law requiring labeling was quickly passed — partially to preempt a Vermont state law requiring its own labeling scheme for GMO products sold there. With the regulations in place, consumers are closer to getting the information they seek on food products, the trade group said.

"Disclosure is imperative to increasing transparency, educating consumers and building trust of brands, the food industry and government," Karin Moore, GMA's senior vice president and general counsel, said in a written statement. "We are pleased that the USDA has now provided a structure for our companies to share this information voluntarily, building a foundation for government to more quickly respond to innovation in food and agriculture in the future."

Food Marketing Institute President and CEO Leslie Sarasin agreed, hailing the "more precise vocabulary into the public discourse regarding biotechnology in food production" represented by the new labeling requirements.

While there has been some voluntary disclosure of GMOs — and certification of non-GMO products — Thomas Gremillion, director of the CFA's Food Policy Institute, mentioned the issue of terminology. Consumers have been using "GMO" and "genetically modified" to talk about these food products — not "bioengineered," which will appear on the label. "Bioengineered" is the term in the law — the acronym "GMO" only appears twice in the text, and each time to say certain products cannot be labeled "non-GMO."

Regardless of terminology, some say that having the law in place doesn't correct fearmongering over GMOs. Transparency group Peel Back the Label said it may actually make it worse.

"While the USDA’s new disclosure rule provides additional clarity for consumers regarding what is and what is not a bioengineered food, it does nothing to reign in the growing use of misleading food labels and meaningless absence claims that are designed to capitalize on consumer fears and confusion in order to boost sales," the group said in a statement emailed to Food Dive. "Consumers deserve both truth and transparency in food labeling, and Peel Back the Label urges the USDA and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to review current voluntary disclosure regulations to ensure food labeling is founded in science, not in fear.”

Follow Megan Poinski on Twitter

Filed Under: Ingredients Packaging / Labeling Policy

Top image credit: U.S. Department of Agriculture

What The 2018 Farm Bill Means For Urban, Suburban And Rural America

Soybean crop on a family farm near Humboldt, Iowa, 2017. USDA/Preston Keres

What The 2018 Farm Bill Means For Urban, Suburban And Rural America

January 16, 2018

Author

Special Advisor, Colorado State University

Disclosure statement

Tom Vilsack served as Governor of Iowa from 1999-2007 and U.S. Secretary of Agriculture from 2009-2017. He is president and CEO of the U.S. Dairy Export Council (USDEC); a Strategic Advisor of Food & Water Initiatives at the National Western Center as part of the Colorado State University System team; and Global Chair for the International Board of Counselors on Food & Water Initiatives. He serves on the board of Feeding America, GenYouth and Working American Education Fund and the World Food Prize Foundation Board of Advisors.

Partners

Colorado State University provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Since the turn of the year, Congress and the Trump administration have been haggling over legislative priorities for 2018. Many issues are on the agenda, from health care to infrastructure, but there has been little mention of a key priority: The 2018 farm bill.

This comprehensive food and agriculture legislation is typically enacted every four or five years. When I became U.S. secretary of agriculture in January 2009, I learned quickly that the bill covers much more than farms and farmers. In fact, every farm bill also affects conservation, trade, nutrition, jobs and infrastructure, agricultural research, forestry and energy.

Drafting the farm bill challenges Congress to meet broad needs with limited resources. The new farm bill will be especially constrained by passage of the GOP tax plan, which sharply reduces taxes on the wealthy and large companies, and by concerns about the size of the federal budget deficit. Farm bill proponents will have to work even harder now than in the past to underscore the magnitude and impact of this legislation, and the ways in which it affects everyone living in the United States.

Nutrition programs, mainly SNAP, account for more than three-quarters of spending under the most recent farm bill.

Helping farmers compete

Of course, the farm bill helps farmers, ranchers, and producers. It provides credit for beginning farmers to get started. It protects against farm losses due to natural disasters through disaster assistance and crop insurance. It provides a cushion for the individual farmer if he or she suffers a poor yield or low prices, through a series of farm payment programs tied to specific commodities.

Agricultural trade is critically important to the bottom line for U.S. farmers, ranchers, and producers. More than 20 percent of all U.S. agricultural production is exported. Agricultural exports are projected to account for one-third of farm income in 2017.

The farm bill authorizes market access promotion and export credit guarantee programs that are key for promoting exports and generating farm income from exports. These programs provide resources to exporting businesses to aggressively market American agricultural products overseas and to enable exporters to price our products more competitively on the world market.

Then-Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack speaks with Provincial Agriculture Deputy Julio Martinez during a visit to a local farmers market in Havana, Cuba, Nov. 13, 2015. USDA/Lydia Barraza.

Making healthy food available and affordable

All of these provide a stable and secure supply of food for the nation. Along with efficient supply chains, they also allow us to enjoy relatively inexpensive food. On average, Americans spend less than 10 percent of their income on food.

The farm bill is also a nutrition bill. It funds the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program(SNAP), our country’s major program that helps low-income individuals and families afford a healthy diet. In 2016 SNAP served more than 44 million Americans.

Two issues are likely to arise during the farm bill discussion. First, there will be an effort to impose work requirements for able-bodied adults without dependents. Today, those individuals are required to be in school or working a minimum of 20 hours a week, or their benefits are limited to three months every 36 months.

Second, there will be efforts to limit what people can buy with SNAP benefits – for example, barring their use to purchase soda or other foods that are considered unhealthy. Implementing such restrictions might prove more difficult and costly than policymakers may expect.

Other nutrition provisions in the bill help senior citizens buy goods at farmers’ markets andmake fresh fruits and vegetables more readily available to millions of school children. It is easy to see why farm and nutrition advocates historically have worked together to support passage of the farm bill in an alliance that joins rural and urban interests.

Food insecurity means that access to adequate food for active, healthy living is limited by lack of money and other resources. Very low food security occurs when food intake for one or more household members is reduced and normal eating patterns are disrupted.

Boosting rural economic development

Only 15 percent of America’s population lives in rural areas, but as the bumper sticker reminds us, “No farms, no food.” The farm bill helps make it possible for people who want to farm to stay on the land by funding supporting jobs that provide a second income. It also provides resources to improve the quality of life in rural places.

Since 2009, programs authorized through the farm bill have helped over 1.2 million families obtain home loans; provided six million rural residents with access to improved broadband service; enabled 791,000 workers to find jobs; and improved drinking water systems that serve 19.5 million Americans.

The farm bill also supports our national system of land grant universities, which was proposed by President Lincoln and created by Congress in 1862. Lincoln envisioned a system of colleges and universities that would expand the knowledge base of rural America by improving agricultural productivity.

Through the farm bill, Congress provides grants for research at land grant universities in fields ranging from animal health to organic crop production and biotechnology. Lincoln would be pleased to know that these programs mirror his vision of increasing agricultural productivity through targeted research shared with farmers and ranchers.

Protecting natural resources and producing energy

Farmers, with the assistance of the farm bill, can improve soil quality and preserve habitat for wildlife. The farm bill funds voluntary conservation programs that currently are helping more than 500,000 farmers and ranchers conserve soil and improve air and water quality – actions that benefit all Americans.

For example, the Conservation Reserve Program pays farmers to take environmentally sensitive land out of agricultural production and conserve it for other purposes, such as wetland habitat for birds. The Environmental Quality Incentives Program and the Conservation Stewardship Program pay farmers to adopt conservation practices, such as conservation tilling and fencing livestock out of streams.

Producing renewable energy is an important tool for expanding economic opportunity in rural areas. USDA’s Renewable Energy for America Program authorizes investments in small- and large-scale projects including wind, solar, renewable biomass and anaerobic digesters, which farmers can use to produce biogas energy by breaking down manure and other organic wastes. Since 2009 the Renewable Energy for America Program has helped finance over 12,000 renewable energy projects.

Investing in food and farmers

In discussion of any legislation that affects so many different constituencies, a key challenge is to recognize that multiple interests are at stake and try to avoid pitting groups against one another unnecessarily. If differences become too divisive, the risk of not passing a farm bill grows.

Many programs in the farm bill are authorized only for specific periods of time. This means the ultimate consequence of not getting a bill passed could be that some policies would revert back to outdated “permanent” (nonexpiring) laws enacted more than 50 years ago. This would cause major disruptions to the nation’s food system and skyrocketing food costs.

Unfortunately, most people are unaware of the farm bill’s importance because they think it impacts only farmers. Over the next few months, debate and discussion about the farm bill will grow, and hopefully will lead to broader understanding of the bill’s importance. I hope this awareness will encourage Congress and the president to provide the level of investment that is needed to maximize the positive impacts that the farm bill can have for all Americans.

The Perils of Pesticide Drift

The Perils of Pesticide Drift

By Sara Novak on August 18, 2017

Running an organic operation in a sea of conventional farms isn’t easy. One waft of pesticide from a neighbor, and tens of thousands of dollars—and your organic certification—is down the drain. But there’s hope in the air. PHOTO BY: Daniel Martin

`Chemical spraying misses its mark with alarming frequency, and neighboring farms—especially organic ones—often pay the price. Luckily, hope is in the air.

“It’s like riding down the highway and expecting to keep the exhaust from your car within the boundaries of the road.”

ANDREW AND MELISSA DUNHAM spent years transforming their farm, which has been in his family for five generations, from a conventional producer of corn, soy, and alfalfa into a diversified operation with 40 different kinds of fruits and vegetables, a herd of 20 grass-fed cattle, even a few beehives. Finally, in May 2009, the couple’s 80 acres in Grinnell, Iowa—now named Grinnell Heritage Farm—became certified organic.

Just two months later, the Dunhams’ pickers spotted a crop duster flying low over nearby seed-corn fields, then noticed a cloud creeping toward them. The crew got out of the way as a fog of fungicide descended on two acres of hay, effectively revoking the acreage’s organic certification for three years, the chemical-free transition period required by the USDA.

The Dunhams’ farm regained full certification in 2012, and the following year, trouble was in the air again. “I could smell it,” says Andrew. “A metallic smell, like a railroad tie.” On the back of a 15-mph wind, a plume of insecticide from a spraying rig began wafting onto the Dunhams’ asparagus. Andrew jumped in his car and rushed to the neighbors’ farm. “To their credit, they stopped spraying,” he says. But the damage had been done: The tainted acre cost the Dunhams tens of thousands of dollars during the three years the produce couldn’t be sold at premium organic prices.

Andrew (left) and Melissa Dunham, both 37, operate an organic farm in Grinnell, IA, that has twice fallen victim to pesticide drift. PHOTO: Kathryn Gamble

Grinnell Heritage Farm is an island of sustainable agriculture in a sea of commodity crops. Iowa leads the nation in corn and soy production, with 13.8 million acres of corn and 9.5 million acres of soybeans that together generated $14.6 billion in revenue last year. The state is also a hotbed of chemical application. Most of its farm acreage is sprayed with herbicide twice a season. Roundup Ready seed remains the norm, but many producers don’t stop at glyphosate; they also apply other powerful weed killers, such as atrazine, and insecticides, including neonicotinoids.

The Dunhams attempted to mitigate their risk by posting “No Spraying” signs and installing a 30-foot-deep perimeter of buffer shrubs; both methods obviously proved inadequate. “Applications usually result in some deposition away from the targeted site,” accord- ing to an Environmental Protection Agency spokesperson.

Though neither the EPA nor various state agencies could provide reliable statistics on the total number of drift incidents, experts agree that reported cases represent the mere tip of the iceberg. “We don’t have a good count due to underreporting,” explains Linda Wells, the Midwest director of organizing for the nonprofit Pesticide Action Network. “Many people neglect to report or do not know who to report to.” In Iowa, it’s the state department of agriculture’s pesticide bureau, which offers no online information about reporting drift. Mark Hanna, an extension agricultural engineer with Iowa State University, says, “The state receives around 200 drift complaints per year, but it’s difficult to grasp the magnitude of the problem.”

In one test, a plane retrofitted with 80 of these temporary vortex generators reduced chemical drift by 40 to 45 percent. PHOTO: Daniel Martin

Minimizing it, however, may be possible. Drones can hover close and spray with great precision, and electrostatic spraying uses an electric charge to attract pesticide droplets to target plants. Both technologies are still years away from widespread implementation, but a potential quick fix has emerged out of the USDA’s Aerial Application Technology Research Unit (AATRU) in College Station, Texas. Large-scale farms like the ones surrounding the Dunhams’ typically opt for aerial application over ground-rig spraying, because planes cover huge swaths faster, decreasing the time workers must be sidelined (per EPA regulations that prohibit them from reentering treated areas for up to 72 hours).

Starting in 2013, Daniel Martin, a research engineer at the AATRU, and his colleagues conducted a study to determine how small wing-mounted blades called vortex generators (VGs)—intended to increase pilot control of commercial and military airplanes—might affect the way agricultural aircraft spray chemicals. Martin’s team outfitted planes with VGs and used dye in place of pesticides. In one test, the VGs reduced the amount of drift by 40 to 45 percent.

Martin, 50, hypothesizes that the tiny vortexes created by VGs help pull pesticide spray down below the plane, thus preventing it from getting caught in the airflow coming off the wings, which can cause the droplets to drift off target (see “How Vortex Generators Work,” below left). He continues to test the concept, and hopes that aerial applicators will retrofit their planes with VGs (at a cost of only about $2,000 per plane).

Illustration by Susan Huyse

David Eby, a veteran aerial applicator in Wakarusa, Indiana, believes that pesticide drift will persist as long as wind and human error remain factors. “It’s like riding down the highway and expecting to keep the exhaust from your car within the boundaries of the road,” he explains. Nevertheless, the 68-year-old is intrigued by the prospect of VGs. “Reducing drift is a win for everybody,” says Eby, whose firm received only one such com- plaint after spraying 375,000 acres in 2016. Already, he employs a digital service called FieldWatch, which allows farmers with vulnerable crops and livestock to register their properties online, alerting aerial applicators to sensitive zones.

Though the Dunhams listed Grinnell Heritage Farm on FieldWatch earlier this year, they’re not overly optimistic. The couple managed to recoup some of their drift-related losses after settling with the applicators’ insurance carriers—but only after producing years’ worth of records and receipts. “It was an all- consuming task,” Andrew explains. “I’d rather have been in the fields.”

This Vertical Farming Startup Is Valued At $27.5 Million

This Vertical Farming Startup Is Valued At $27.5 Million

By Daniel Lipson 2017

What's vertical farming? In Bowery Farming's first indoor farm, located in a warehouse in New Jersey, proprietary computer software, LEDs, and robotics are able to grow leafy greens without any pesticides, using 95% less water than traditional farms. CEO Irving Fain describes his company as a tech company "thinking about the future of food."

Their indoor farms can be located near city centers and will be able to cut transportation costs and help curb the environmental impact of the industry. By being located indoors, they're unbeholden by weather and can produce 100 times more greens than a traditional outdoor farm of the same size. Fain sees it as a way to answer global population growth, shrinking farmlands, and an influx of people towards urban areas. The farms are enabled by recent technological advances in data analytics and lighting and are poised to scale up in the coming years.

YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP/Getty Images

Fain started his career as an investment banker at Citigroup, ran marketing at iHeartMedia, and co-founded loyalty marketing software firm CrowdTwist before venturing into food. They raised first round funds of over $20 million from a list of investors that includes Blue Apron CEO Matt Salzberg and celebrity chef Tom Colicchio as well as GV (formerly Google Ventures). The company has experimented with over 100 different crops and sells six varieties of leafy greens to Whole Foods and Foragers. They plan to use the extra cash to hire more workers and move towards other types of produce. For the long term, they are eyeing China and other emerging markets where food security is an important topic.

Bowery isn't the only one trying to do vertical farming. Competitors AeroFarms and Plenty United are also farming indoors with the capacity to produce millions of greens, and AeroFarms has already raised $100 million, while Plenty United has billionaire backing from Jeff Bezos and Eric Schmidt. The technology enables vertical farmers to convert old warehouses and factories into agricultural centers. All of them benefit from advances in LED lighting that can mimic natural sunlight, as well as lower costs for industrial-scale lighting setups

Exclusive Agreement Between Mastronardi Produce and Golden Fresh Farms

Exclusive Agreement Between Mastronardi Produce and Golden Fresh Farms

Mastronardi Produce and Golden Fresh Farms, located in Wapakoneta, Ohio, are pleased to announce an exclusive agreement between the two companies to bring Mastronardi’s SUNSET® brand produce to more consumers throughout the US. This will be the 5th state that the SUNSET® brand will be grown locally in, allowing the company to reach over 75% of the United States population, delivering a local fruit in less than a 10-hour drive.

“Luis Chibante is a fantastic grower and operator. I’ve known him for years,” stated Mastronardi Produce President and CEO Paul Mastronardi. “His passion and expertise in growing will enable both of us to expand the Ohio footprint together.”

The Ohio Proud program allows loyal consumers to choose great tasting products that help support their local communities and ensures freshness.

“I’m excited to join Paul and the SUNSET® team with our new crop starting this fall,” shared Luis Chibante, President and owner of Golden Fresh Farms. “Mastronardi is the best growing and marketing company in the greenhouse industry, and this will give us the opportunity we need to expand the next 15 acres.”

Currently the greenhouse grows approximately 20 acres of tomatoes year-round with advanced supplemental lighting.

For more information: www.sunsetgrown.com

Publication date: 8/15/2017

USDA and SCORE Launch Innovative Mentorship Effort to Support New Farmers and Ranchers

USDA and SCORE Launch Innovative Mentorship Effort to Support New Farmers and Ranchers

August 8, 2017 | USDA

News Release – DES MOINES, Iowa – U.S. Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue today signed a Memorandum of Understanding with officials from SCORE, the nation’s largest volunteer network of expert business mentors, to support new and beginning farmers. Today’s agreement provides new help resources for beginning ranchers, veterans, women, socially disadvantaged Americans and others, providing new tools to help them both grow and thrive in agri-business.

“Shepherding one generation to the next is our responsibility. We want to help new farmers, veterans, and people transitioning from other industries to agriculture,” said Secretary Perdue. “They need land, equipment, and access to capital, but they also need advice and guidance. That’s what SCORE is all about.”

SCORE matches business professionals and entrepreneurs with new business owners to mentor them through the process of starting-up and maintaining a new business. USDA and its partners across rural America are working with SCORE to support new farming and ranching operations, and identify and recruit mentors with a wealth of agricultural experience.

Secretary Perdue announced the new partnership in Des Moines during the Iowa Agriculture Summit. Perdue was joined by Steve Records, Vice-President of Field Operations for SCORE in signing a Memorandum of Understanding that will guide USDA and SCORE as they partner in the mentorship effort, which will soon expand to other states.

“SCORE’s mission to help people start and grow vibrant small businesses is boosted by this new partnership with USDA. America’s farmers, ranchers and agri-businesses will benefit from the business knowledge and expertise SCORE can offer,” said Records. “The partnership allows both SCORE and USDA to serve more people while providing America’s farmers added support to lead to more sound business operations, create profitable farms with sustainable growth and create new jobs. We are excited at the opportunity to extend SCORE’s impact to our farmers and the agriculture industry.”

SCORE mentors will partner with USDA and a wide array of groups already hard at work serving new and beginning farmers and ranchers, such as the FFA, 4-H, cooperative extension and land grant universities, nonprofits, legal aid groups, banks, technical and farm advisors. These partnerships will expand and integrate outreach and technical assistance between current and retired farmers and agri-business experts and new farmers.

This joint initiative leverages SCORE’s 10,000 existing volunteer mentors and USDA’s expertise and presence in agricultural communities to bring no-cost business mentoring to rural and agricultural entrepreneurs. This initiative will also be another tool to empower the work of many community-based organizations, cooperative extension and land grant universities working with beginning farmers in their communities. SCORE mentorship will also be available to current farmers and ranchers. Anyone interested in being a mentor can get more information and sign up on the USDA New Farmers’ website at https://newfarmers.usda.gov/mentorship.

Thomas Paine Plaza Will Transform Into A Big Urban Farm in 2018

Thomas Paine Plaza Will Transform Into A Big Urban Farm in 2018

The PHS-run Farm Will Produce 1,000 Pounds of Fruits and Vegetables

BY MELISSA ROMERO JUN 20, 2017, 12:00PM EDT

PHS will bring a temporary urban farm to Thomas Paine Plaza, similar to this pop-up garden that was set up at in 2011 at 20th and Market.

Photo courtesy of Pennsylvania Horticultural Society

Goodbye, larger than life Parcheesi pieces, hello 2,000-square-foot urban farm: Next summer, the Thomas Paine Plaza in Center City will be transformed into a large community farm that’s estimated to produce about 1,000 pounds of fruits and vegetables.

The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS) was just awarded a $300,000 grant from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage to create a “Farm for the City” at Thomas Paine Plaza, across from City Hall. The plaza is well-known for its 20-year-old “Your Move” art installation that features over-sized dominoes, chess and bingo pieces, and other game pieces scattered all over the plaza.

Thomas Paine Plaza in Center City, Philadelphia. via Flickr/Wally Gobetz

Farm for the City will bring a temporary 2,000-square-foot urban farm to the plaza as way to spotlight food security in the city, where many neighborhoods lack easy access to supermarkets or fresh food. In addition to the actual farm, the site will play host to forums, gardening workshops, and performances throughout the summer and fall of 2018.

Meanwhile, the produce produced from the farm will be donated to Broad Street Ministry, a non-profit organization that serves the homeless. The ministry, which will help tend the garden, says it will also host two community dinners for 150 people using the food grown at the farm.

PHS spokesperson Alan Jaffe says the design is still in the very early stages, so we’ll have to wait a little longer for a preview of Thomas Paine Plaza’s transformation and whether the “Your Move” art installation will remain in place.

Urban Farm Coming to Downtown Mobile

Urban Farm Coming to Downtown Mobile

Posted: Aug 13, 2017 10:50 PM CDT - By Lee Peck, FOX10 News Reporter

Shipshape Urban Farms hopes to break ground in near future and open in downtown Mobile later this year. Source: Dale Speetjens

Downtown Mobile Urban Farm

610 St. Michael Street may not look like much now, but the vacant lot will soon be home to something downtown Mobile has never seen.

Dale and Angela Speetjens are the masterminds behind Shipshape Urban Farms. Angela has a background in horticulture and will manage the farm. They'll use eight repurposed shipping containers, they'll grow the equivalent of a 20-acre farm on a 1/4 of an acre.

They'll use a process called hydroponics -- an efficient method of growing plants without soil in nutrient rich water. It maximizes the process from start to finish and takes the environmental pressures out of the equation.

"So normal farming you lose a lot of your crops to pests... here we are gong to be able to control the light, control the nutrients, we're going to be able to control the climate," explained Speetjens.

They expect to hire around four employees. Each container will require 8 to 15 hours a week of work.

Giving whole new meaning to homegrown, expect all your leafy green favorites 365 days a year.

"All year long -- we will produce every single week... We harvest close to 10,000 plants. Lettuce, herbs, salad mixes," said Speetjens.

They plan to serve local restaurants, farmers markets, and businesses in both Mobile and Baldwin counties. Customers will also be able to purchase produce through Shipshape's CSA program. CSA stands for "community Supported Agriculture. For an annual fee, CSA members will get a weekly basket of produce from the farm.

As a part of the mayor's innovation team, Speetjens knew there was a place for the urban garden in downtown Mobile.

"During that process, I worked on blight and vacant lots and I had a good idea where a lot of the vacant lots were in town," said Speetjens.

Speetjens expects their operation to spur other activity in the area.

"We are just one piece of the pie. If you look next to us... I can name 10 projects that are in some level of in the works," said Speetjens.

According to Speetjens, next door there's even talk of a restaurant and a brewery down the way.

"Most cities that are thought of as being walkable it's not a single street, it's a couple of streets and it won't take much for us to make connections between the St. Louis corridor and the Dauphin Street corridor -- a few in fills here and there - and we could really start seeing a boom. Doesn't take that much to make a big thing happen," said Speetjens.

Speetjens says they have a meeting with City of Mobile August 23 and will have a better idea of when they will break ground. He hopes they will be open by Christmas. For more information click here.

Urban Hydroponic Farms Offer Sustainable Water Solutions

Urban Hydroponic Farms Offer Sustainable Water Solutions

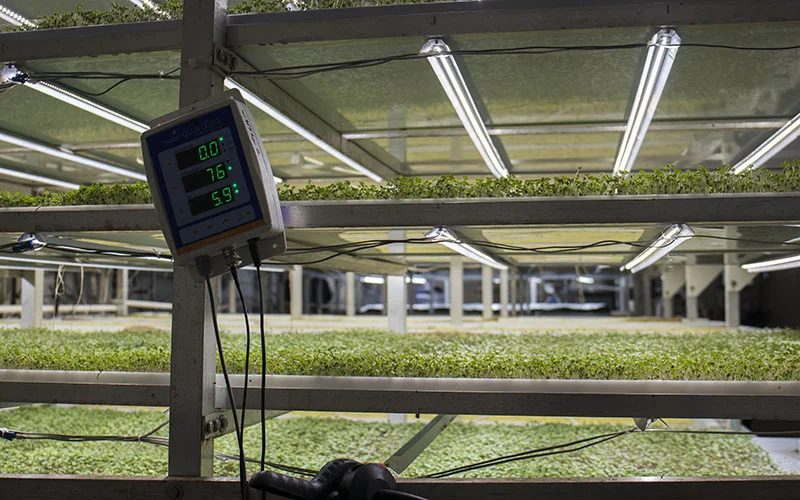

At Local Goods in California, Ron Mitchell’s monitoring system checks the plants’ water supplies for temperature, pH levels and electric conductivity. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

By Nicole Tyau | News21 Tuesday, July 11, 2017

BERKELEY, Calif. – Tucked behind a Whole Foods in a corner warehouse unit, Ron and Faye Mitchell grow 8,000 pounds of food each month without using any soil, and they recycle the water their plants don’t use.

Hydroponic farming grows crops without soil. Instead, farmers add nutrients to the water the plants use. This method can produce a wide variety of plants, from leafy greens to dwarf fruit trees.

According to a study by the Arizona State University School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, hydroponic lettuce farming used about one-tenth of the water that conventional lettuce farming did in Yuma, Ariz. A similar study from the University of Nevada, Reno, found that growing strawberries hydroponically in a greenhouse environment also used significantly less water than conventional methods.

(Video by Jackie Wang/News21)

The Mitchells started production of Local Greens in February 2014. They primarily grow microgreens such as kale, kohlrabi and sprouted beans while using the same amount of water as two average households and the same amount of electricity as three in a month, they said.

“Who knows what you’re getting when you’re using soil?” Faye said. “Hydroponics is a fully contained system, so we know exactly what’s in our water, what we want in it and what we don’t want in it, and we can control that.”

Ron installed a water filtration system he customized. He removes fluoride, a common additive in municipal water, and chlorine, a common disinfection byproduct, before adding oxygen and other plant-specific nutrients.

At Local Greens, Ron and Faye Mitchell mostly cultivate microgreens, which grow to about 10 inches before they are cut and sold in the area. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

To make use of the warehouse’s tall ceilings, the Mitchells stack six trays of microgreen seeds on top of each other. At one end, an irrigation spout controls the amount and type of water sent through the trays.

“Some plants don’t need or want nutrients because they have it in their seed,” Ron said. He explained that pea shoots don’t need any additives, but sunflowers require copious amounts of nutrients to grow quickly.

Ron Mitchell, 67, said the stacked trays inside his hydroponic farming facility in California allow them to grow twice as much. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

The water the plants don’t use is captured at the other end of the tray and reused for the next watering, with the nutrients replenished as needed. The additional nutrients in the water are organic and naturally-occurring since they don’t have to spray pesticides or herbicides in their controlled warehouse environment, Faye said.

The number of greenhouse farms has more than doubled since 2007, according to the 2012 U.S. Department of Agriculture Census of Agriculture. Some hydroponics advocates see the practice as a solution to a global food and water crisis.

“I don’t think it could take over the farming industry entirely because of the types of plants and vegetables people want to eat,” Faye said. “But I definitely think it could make a dent in the farming industry and make its place and replace certain types of farms for a more efficient and, in some cases, less expensive system.

Editor’s note: This story was produced for Cronkite News in collaboration with the Walter Cronkite School-based Carnegie-Knight News21 “Troubled Water” national reporting project scheduled for publication in August. Check out the project’s blog here.

This Company Wants to Bring Soil-Free Farming to Restaurant Kitchens

Hydroponics have allowed garden vegetables to grow in novel places—from a pillar inside a Berlin grocery store to a veritable skyscraper of plants in Singapore.

This Company Wants to Bring Soil-Free Farming to Restaurant Kitchens

by Cathy Erway • 2017

Hydroponics have allowed garden vegetables to grow in novel places—from a pillar inside a Berlin grocery store to a veritable skyscraper of plants in Singapore. The fast-growing, soil-free farming method has been well-embraced in urban areas to produce crops using less water and space, since the plants are grown in a nutrient water solution, rather than in-ground. But rarely is it done within some of the buzziest places for the farm-to-table movement: a restaurant.

The team behind Farmshelf hopes that will soon change, and recently debuted three indoor hydroponic growing units at Grand Central Station’s Great Northern Food Hall. There, the chefs at the busy food market’s Scandinavian restaurant Meyers Bageri reach into the glass-walled cubicles to pick lemon basil for a garnish on their zucchini flatbread, and nearly a dozen varieties of baby lettuces are plucked for salads at the neighboring Almanak vegetable-driven café. And, as it would appear on recent visits, curious bystanders peer through the glass, agape at the billowy mixture of herbs and greens, illuminated by a ceiling of LEDs. Unbeknownst to the casual observer, the units are also outfitted with five cameras along every shelf, so that the Farmshelf team can monitor the plants’ progress from afar and adjust the system via a web application.

“The more plants we grow, the smarter we are about plants,” said Jean-Paul Kyrillos, Farmshelf’s Chief Revenue Officer. He explained that through their data collection, Farmshelf can optimize the growth and flavor of any plants that a client may want. “This is for someone who doesn’t want to be a botanist, or farmer. The system is automatic.”

“Plants can grow two to three times as fast using 90% less water than traditional in-ground farming”

That’s why Farmshelf hopes its units will be a boon for restaurants serving greens galore. Founded in 2016 by CEO Andrew Shearer, Farmshelf is just planting its roots in the New York City restaurant industry with its first partner, Meyers USA hospitality group. The startup was in the inaugural lineup of the Urban-X accelerator and is part of the Urban Tech program at New Lab. The company is looking to partner with more restaurants soon, and Kyrillos mentioned a restaurateur who was excited about the idea of placing a Farmshelf unit right in the dining room, as a partition.

Distribution is the last challenge of getting local food onto plates, and Farmshelf eliminates that entire process—no middleman, forager, or schleps to Union Square Greenmarket. Kyrillos is hopeful that the efficiency of hydroponics—where plants can grow two to three times as fast using 90% less water than traditional in-ground farming—will also convince restaurants of the value of placing such a system on-site. Then, there is the potential of growing ingredients that you could never get locally, like citrus; or mimicking the terroir of, say, Italy, through a special blend of nutrients and conditions within the units.

Green City Growers in Cleveland, OH, has a 3.25-acre hydroponic greenhouse. Photo by Flickr/Horticulture Group

With hydroponics, you can grow a plethora of vegetables, even root vegetables like turnips, carrots, radishes, but these take much longer, and thus not suited to the fast-paced restaurant environment Farmshelf is trying to service. Crops that take up a lot of space, like watermelon and pole beans, are also not ideal, as the point is for these systems to use space efficiently (though future designs of hydroponic units might be able to tackle this challenge). It's most cost-effective to grow delicate, highly perishable, expensive leafy greens than roots, which are quick to grow and easy to ship and store.

The possibilities seem endless. But, in an age when the small family farm is rapidly disappearing in the US—and faces further threat from a recent White House budget proposal that would eliminate crop insurance—would this technology take away business from local farms, which restaurants might otherwise buy from?

Hydroponics—The Future of Farming in Detroit?by Lindsay-Jean Hard

Kyrillos doesn’t see Farmshelf as a replacement for the local farmer. There are some six to eight months of the year where traditional farms can’t grow too many crops, so restaurants would buy leafy greens and other warm-season produce elsewhere. If anything, Kyrillos posited that it might chip away at business from some of the bigger food distributors.

But time will have to tell what best works for the soon-to-be users of Farmshelf. Right now, the company is hoping to sell restaurants at least three growing units to make a significant enough impact on its kitchen orders. Rather than leaving it at that, Farmshelf wants to work with restaurants through a sort of subscription-based service, supplying seeds for crops that the restaurant would like to grow and monitoring the growing process consistently. Could a chef go rogue, and use the unit to plant and harvest whatever, whenever he pleased? Perhaps—but that wouldn’t really be taking advantage of the full product, which the team estimates might cost around $7,000 per unit (a medium-sized restaurant might need three units, at $21,000), which would pay off in ingredient costs.

And how about home chefs? When will average consumers be able to place Farmshelf inside our cramped, outdoor space-free apartments? That’s in the vision for Farmshelf someday. Not just homes, but school classrooms or cafeterias could be future sites of these hydroponic shelves, Kyrillos suggested, offering an easy, indoor way to connect youngsters to the food on their plates. “Imagine children were watching food grow, all the time.”

TAGS: HYDROPONICS, TECHNOLOGY, ENVIRONMENT, GRAND CENTRAL

Shenandoah Growers Opens Texas Indoor Production Facility

Shenandoah Growers Opens Texas Indoor Production Facility

July 13 , 2017

Virginia-based organic culinary herb grower and producer Shenandoah Growers (SGI) claims it is “set to transform the distribution of highly perishable produce”.

Through a proprietary combination of automated greenhouses and indoor LED vertical grow rooms to produce more than 30 million certified organic plants per year, SGI has now brought a third indoor growing facility online.

The new facility, located in Texas, is the latest component of SGI’s innovative hub-and-spoke farming and distribution system, and only the most recent step in the company’s three-year, multi-million-dollar nationwide expansion of indoor farming.

The group claims the system is quickly scalable for market growth, allowing Shenandoah Growers to “locally deliver certified organic superior flavor and shelf life at a fraction of the capital cost of other indoor farms”.

“This indoor farm, and the two others in our system, are critical elements of how Shenandoah Growers is transforming the way perishable produce is grown and distributed,” SGI CEO Timothy Heydon said in a release.

“With the integration of our modular indoor growing technology into our existing national footprint, we can grow amazing certified organic produce that delivers fresh flavor to consumers in a sustainable way, minimizing inputs of water, bio-media, land resources, and food miles.

“We are proud to be a part of transforming agriculture production and distribution for the future.”

SGI’s Rockingham, Virginia farm complex serves as the eastern hub of a nationwide growing system, and with a farming and supply chain platform spanning the country, the group claims its indoor farms cover the Mid-Atlantic, Midwest and South Central market.

The group continues the expansion of its farms, greenhouses and the implementation of an indoor farming hub and spoke system on the West Coast, with completion expected in 2018.

Nebraska Man’s Mushroom Growing Hobby Becomes A Business

Fence Post courtesy photo |

Nebraska Man’s Mushroom Growing Hobby Becomes A Business

At a farmers market in Lincoln, Neb., Ash Gordon talks to consumers about mushroom varieties.

They look like sculptures: mushrooms with exotic names like Lion's Mane and Blue Oyster. And they flourish inside a nondescript warehouse located near the airport in Grand Island, Neb. Nebraska Mushroom is an indoor farm where unusual varieties of the fungi are pampered and fussed over from colonization to harvest.

Ash Gordon is the mushroom man.

"The varieties we grow are different than what you normally find at the grocery store," said Gordon, the founder of Nebraska Mushroom. "They have different flavors and textures. Everybody can find a mushroom they like because there are so many options."

Growing up in Nebraska, Gordon spent time as a boy foraging for mushrooms along the Platte River near his Grand Island home. He even bought a mushroom field guide from the Audubon Society to bolster his hobby.

As an adult, Gordon worked as a kidney dialysis technician. Then, at age 27, he developed arthritis that was painful and debilitating. Research into the healing properties of mushrooms led him to include more mushrooms in his diet through tinctures, extracts and teas. With other lifestyle changes, his arthritis symptoms eased and his mushroom hobby grew into a business.

For Gordon, growing mushrooms is both a science and an art. He follows strict procedures to colonize and produce a mushroom, lessons learned by reading books and studying information found on the internet. The art of growing mushrooms has developed through trial and error.

"There's a lot of science in it but I would say the art is in manipulating the conditions so that the mushroom knows it's time to fruit, and then will produce for us," Gordon said.

COLONIZATION

The process begins with mycelium, a culture of mushroom tissue stored in a tube called a slant. A pea-sized piece of mycelium is transferred to a petri dish to colonize. The resulting mushroom culture is mixed with sterilized grain and eventually transferred to bags of sawdust.

One pea-sized piece of mycelium makes about eight grain jars. One jar translates into five master bags and each master bag expands into 30 bags of substrate, where the mushrooms begin to fruit.

The bags are moved to greenhouse-like structures where they begin to react to their environment in different ways. The grow rooms are warm and humid, but the air conditioning runs year round. Even in the winter, Gordon said the mushrooms generate so much heat as they grow they can actually start to cook if the temperature gets too high.

The growing process varies according to the mushroom. Gordon cuts holes in the bags of Oyster mushrooms, allowing them to recognize the fresh air and begin to grow out of the bags. Shitakes go through a more dramatic fruiting process.

"The Shitake mushrooms go through a popcorn stage where they really bubble up and blister. They break through the bags and turn completely brown," Gordon said. "The Oysters stay white the whole time."

Mushrooms also have different personalities: They can be small and delicate or troublesome and finicky. For example, Gordon keeps close watch on a particular strain of Shitake mushroom because if he overfeeds it, the mushroom starts to make mutants. If the bag isn't flipped over, the mushrooms start growing down, under the racks. In general, Gordon said, the mushroom "can be a pain sometimes."

AFTER THE HARVEST

After harvesting the mushrooms, Gordon packages the crop for sale at farmer's markets, grocery stores and co-ops. He also supplies a few restaurants with his fresh mushrooms.

Summer is the busiest time for Gordon. The mushrooms grow so fast, he goes through periods where he is constantly harvesting. Late nights in the greenhouse are followed by early mornings at the farmer's market. In spite of the long hours, Gordon enjoys introducing consumers to mushrooms. He sees a strong future for mushroom farming because consumers are more interested in buying fresh food and they want to know more about where their food comes from and how it's grown.

"The best part is people's reactions," he said. "They don't realize how many types of edible mushrooms there are, the different colors and textures. I like talking to the public and educating people about the mushrooms and how to use them."

Gordon never stops learning and thinking about what's next. He produces and sells mushroom extracts and dried mushrooms. Leftover mushroom substrate is dumped in a pile where, over time, a rich compost develops that can be used to improve the quality of soil for vegetable gardens. Gordon wants to expand his business to include creating products that will help other farmers get into the mushroom business, from providing information to selling mushroom cultures.

"People are interested but maybe they don't have the space or the time or the knowledge," Gordon said. "I'd like to give people more affordable, easier options to help them get started." ❖

— Mary Jane Bruce is a freelance reporter for The Fence Post. She can be reached at mbruce1@unl.edu, or on Twitter @mjstweets.

Alliance Greenhouse Uses Geothermal Heat To Produce All Year Long

Alliance Greenhouse Uses Geothermal Heat To Produce All Year Long

- TORRI BRUMBAUGH Staff Intern | torri.brumbaugh@starherald.com

- Jun 10, 2017

Russ Finch shows off his tango mandarins, a hybrid that contains no seeds.

Torri Brumbaugh/ Star Herald

ALLIANCE — Members of the Nebraska Master Gardener Program anxiously wait as Alliance’s Russ Finch cuts an orange. While the excitement for a simple orange seems strange, this orange is different. It is a 3-year-old orange that Finch grew in his own backyard.

Finch was simply a mail carrier and farmer in Alliance, until 45 years ago when he started experimenting with heating houses with geothermal heat. Fifteen years later, he began using the geothermal heat to improve greenhouses.

Geothermal heat produces heat from the ground. A singular heat source dispenses heat into a tubing system that runs under the ground of the greenhouse. The heat is constantly circulating and reused to create the perfect environment for the greenhouse. This means that in Finch’s greenhouses, he can grow any tropical or subtropical plant that he wants.

Russ Finch leads members of the Nebraska Master Gardener Program into a newly builty greenhouse.Torri Brumbaugh/ Star Herald

His personal greenhouse is filled with numerous plants, nine varieties of southern grapes, pomegranates, 13 types of citrus fruit and much more. His citrus fruits include Eureka lemons, Meyer’s lemons, Cara Cara oranges, Tango mandarins and Washington naval oranges.

At 78-feet long, Finch’s greenhouse is 24 years old and the first one he created.

Around three years ago, Finch began to sell the frames, systems and equipment for his geothermal greenhouses with his business, Greenhouse in the Snow.

Compared to his personal greenhouse, the new greenhouses are much more efficient.

The new greenhouses are at least 96 feet long. They also include shelves on one wall to grow ground vegetables and fruit. The other side of the greenhouse is often designated for trees.

“We just put everything in it to see if it’ll grow, and almost everything did,” says Finch.

Finch’s geothermal greenhouses appear to be much more efficient than the standard greenhouse.

To run his personal greenhouse, it costs Finch up to 85 cents a day. Other geothermal greenhouses, like the one at Alliance High School, cost up to 97 cents a day. A geothermal greenhouse only costs around $200 to run in the winter, compared to the $8,000 it would cost with a regular greenhouse.

In his greenhouses, Finch can also produce more product than planting outside.

A greenhouse can produce 14 tomatoes to every one tomato that average farming produces, while with other crops it is often 50-1, Finch said. Weather is a big factor in this because greenhouses have a controlled environment.

Here is a prototype of Russ Finch's newer greenhouses.

Torri Brumbaugh/ Star Herald

The profit produced by the geothermal greenhouses is a great benefit as well.

Finch said, “Each tree needs an 8-foot circle and will produce 125 pounds of fruit. If a pound is usually $3.50 at a farmers market, that makes each 8-foot circle worth $430.”

According to Finch, most young people do not want to get into agriculture because they believe it is too expensive. Little do they know, a single 3-year-old tractor with four-wheel drive is the same cost as putting up nine of Finch’s greenhouses. So for those looking to get into agriculture, Finch highly suggests going geothermal.

Member of the Nebraska Master Gardener Program get the opportunity to explore one of Russ Finch's newer greenhouses outside of Alliance, Nebraska.

Torri Brumbaugh/ Star Herald

Greenhouses are efficient cost wise, but the newer greenhouses also include a key to helping with the extinction of bees.

Finch showcased an Australian beehive called Flow Hive. The hive would replace common beehives and take away the need for smokers, a device used to calm bees. Within Flow Hive, the hexagonal cells are already formed, so the bees do not need to create them with wax.

When the honey needs to be taken from the beehive, a key is used to break the cells and drain the honey. Finch claims that the new beehives would help kill less bees and hopefully, help the bee from coming extinct.

Finch has sold about 38 greenhouses and almost all of them have been used for commercial purposes. Nine states — including Alaska, South Dakota, Wyoming and Kansas — now have Finch’s greenhouses, along with two greenhouses in Canada.

The Federal Aviation Administration has just given the go for a greenhouse to be built at the Western Nebraska Regional Airport in Scottsbluff. The greenhouse will be used by the North Platte Natural Resources department. It is estimated that the greenhouse will be put in place in late spring.

With the success of Greenhouse in the Snow, Finch is very hopeful for the possibilities. He is trying to spread his geothermal heat across the globe to countries like Australia, Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Greece and South Africa.

According to Finch, all of the Midwest’s table citrus could be grown locally in greenhouses.

Lemons grow in Russ Finch's greenhouse.

Torri Brumbaugh/ Star Herald

For more information on purchasing a geothermal greenhouse, contact Finch at greenhouseinthesnow.com.

Indoor Farming Start-Up Plenty Secures $200m In Funding

Indoor Farming Start-Up Plenty Secures $200m In Funding

Posted By: News Deskon: July 19, 2017In: Agriculture, Environment, Food, Industries, Uncategorized

US indoor farming start-up Plenty has obtained $200 million in funding led by the SoftBank Vision Fund as it expands its agriculture model.

Plenty claims to be developing patented technologies to build a ‘new kind of indoor farm’ that uses LED lighting and micro sensor technology to deliver higher quality produce.

The company said the investment will boost its global farm network and support its mission of ‘making fresh produce available and affordable for people everywhere’.

As part of the deal, SoftBank Vision Fund’s managing director Jeffrey Housenbold will join the Plenty board of directors.

SoftBank Group Corp chairman Masayoshi Son said: “By combining technology with optimal agriculture methods, Plenty is working to make ultra-fresh, nutrient-rich food accessible to everyone in an always-local way that minimises wastage from transport.

“We believe that Plenty’s team will remake the current food system to improve people’s quality of life.”

Based in San Francisco, Plenty plans to build its farms near the world’s major population centres to produce GMO and pesticide-free produce while minimising water use.

Plenty CEO and founder Matt Barnard said: “Fruits and vegetables grown conventionally spend days, weeks, and thousands of miles on freeways and in storage, keeping us all from what we crave and deserve — food as irresistible and nutritious as what we used to eat out of our grandparents’ gardens.

“The world is out of land in the places it’s most economical to grow these crops.”

He concluded: “We’re now ready to build out our farm network and serve communities around the globe.

Urban Aquaponic Farmer and Chef Redefines Local Food in Orange County, CA

Urban Aquaponic Farmer and Chef Redefines Local Food in Orange County, CA

Heads of lettuce gain their sustenance through aquaponics channels at Future Foods Farms in Brea. Photo courtesy Barbie Wheatley/Future Foods Farms.

In a county named for its former abundance of orange groves, chef and farmer Adam Navidi is on the forefront of redefining local food and agriculture through his restaurant, farm, and catering business.

Navidi is executive chef of Oceans & Earth restaurant in Yorba Linda, runs Chef Adam Navidi Catering and operates Future Foods Farms in Brea, an organic aquaponic farm that comprises 25 acres and several greenhouses.

Navidi’s road to farming was shaped by one of his mentors, the late legendary chef Jean-Louis Palladin.

“Palladin said chefs would be known for their relationships with farmers,” Navidi says.

He still remembers his teacher’s words, and now as a farmer himself, supplies produce and other ingredients to a variety of clients as well as his restaurant and catering company.

Navidi’s journey toward aquaponics began when he was at the pinnacle of his catering business, serving multi-course meals to discerning diners in Orange County. Their high standards for food matched his own.

“My clients wanted the best produce they could get,” he says. “They didn’t want lettuce that came in a box.”

So after experimenting with growing lettuce in his backyard, he ventured into hydroponics. Later, he learned of aquaponics. Now, aquaponics is one of the primary ways Navidi grows food. As part of this system he raises Tilapia, which is served at his restaurant and by his catering enterprise.

Just like aquaponics helps farmers in cold-weather climes grow their produce year-round, the reverse is true for growers in arid, hot and drought-prone southern California.

“Nobody grows lettuce in the summer when it’s 110 degrees,” Navidi says.

But thanks to aquaponics, Navidi does.

Navidi also puts other growing methods to use at Future Foods Farms. He grows San Marzano tomatoes in a greenhouse bed containing volcanic rock (this premier variety was first grown in volcanic soil near Mount Vesuvius in Italy). Additionally, he utilizes vertical growing methods.

For Navidi, nutrient density is paramount—to this end, he takes a scientific approach in measuring the nutrition content of his produce. In the past, he and his staff used a refractometer, but now rely on a more precise tool—a Raman spectrometer. This instrument uses a laser that interacts with molecules, identifying nutritional value on a molecular level.

With a Raman spectrometer, Navidi measured the sugar content of three tomatoes—one from a grocery store, one from a high-end market, and one that he grew aquaponically. Respectively, measurements read 2.5, 4.0 and 8.5.

Navidi wants his customers to know about these nutritional differences, so he educates his Oceans & Earth diners through its menu and website. Future Foods Farms also offers internship opportunities to students from California State University, Fullerton. Interns conduct research and learn about cutting-edge ways to grow food.

Navidi believes aquaponics and other innovative growing methods can lead to a more robust local food system in Orange County. But he also sees some of southern California’s undervalued resources—namely, common weeds such as dandelion and wild mustard—helping the region become a major local foods player.

“We need more research on nutrients in weeds,” he says. “Dandelions and mustard are power weeds, and need little water.”

While these wild plants are important, they’re no substitute for policy. Navidi would like to see farmers in the county pay lower rates for water, and believes that a revised zoning code is needed for a county that is urban and becoming more so.

“Now, urban farming is happening all over,” he says. “We need changes to our zoning laws—politicians realize that.”

New zoning rules could help others in Orange County venture into aquaponics, something Navidi feels is necessary not only for the county, but for the country.

“For America to be sustainable, it needs aquaponics,” he says.

Ultimately, Navidi’s goal is to provide the best product possible, with an eye toward simplicity, health and wholesomeness.

“Any fine-dining chef is concerned with the quality of their product,” he says. “There’s nothing better than real food. I try to grow the most nutrient-dense tomato possible. Just add sea salt and black pepper—that’s all you need.”

Convention Center Plays Host To Urban Farm: Take A Look Around

Convention Center Plays Host To Urban Farm: Take A Look Around

2017

Tour the urban farm outside Cleveland's convention center

BY EMILY BAMFORTH, CLEVELAND.COM | ebamforth@cleveland.com

CLEVELAND, Ohio -- Look out of some of the windows of the Cleveland Convention Center, and you'll see greenery, dozens of chickens, lines of bee hives and three pigs.

It's a sight that brings Clevelanders on their lunch breaks or enjoying downtown during the summer months peering over the top of the building from the mall above, trying to sneak a peek at the animals below.

The farm is run by, and produces significant amounts of ingredients for, Levy Restaurants, the food service provider for the convention center. The project began more than three years ago with beehives, and has slowly grown to include raised beds, chickens and pigs.

Read more: Honeybees bring the sweetness of urban agriculture to Cleveland's convention center

The farm is part of the convention center's sustainability efforts. More than 50 percent of the trash from the the Global Center for Health Innovation and the convention center was recycled in 2016, according to a report by SMG, a firm hired by the Cuyahoga County Convention Facilities Development Corporation to manage operations for the facilities.

The three Mangalista heritage breed pigs help with the recycling efforts by eating some of the food scraps.

Find out more about the farm and sustainability efforts at the convention center in the video above.

Some Urban Farmers Are Going Vertical

In a factory parking lot in Brooklyn, a crowd of about 100 people gasped and murmured as Tobias Peggs cracked open the heavy metal doors of a white shipping container, allowing pink light to spill out from within.

Some Urban Farmers Are Going Vertical

2017

In a factory parking lot in Brooklyn, a crowd of about 100 people gasped and murmured as Tobias Peggs cracked open the heavy metal doors of a white shipping container, allowing pink light to spill out from within. The interior of the container looked like a dance club, or a space station: Strips of dangling LED lights glowed red and blue, illuminating white plastic panels. Leafy green vegetables grew from the walls.

Mr. Peggs, 45 years old, chief executive of a new company called Square Roots, recently was leading a farm tour of his new urban agriculture operation in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn. The shipping container was a vertical farm, one of the company’s 10 located in the parking lot, each capable of growing the equivalent of 2 acres of crops in a carefully controlled indoor environment, he said. Square Roots, which uses hydroponic technology to raise a variety of herbs and greens, is one of the latest companies to join the expanding industry of high-tech indoor farming. Proponents of vertical farming say it is designed to meet the increasing demand for locally grown food—fueled by distrust of large-scale industrial agriculture—at a time when more people are moving into cities.

Square Roots, co-founded by Kimbal Musk, brother of famed inventor and businessman Elon Musk, isn’t only growing vegetables. The company is trying to cultivate a network of food entrepreneurs by operating a kind of apprenticeship program. Each of its 10 shipping-container farms is run by a different entrepreneur selected from hundreds of applicants.

Messrs. Musk and Peggs have a grand vision: A network of Square Roots farms in urban centers across the U.S., each supplying locally grown produce to city-dwellers, while transforming mostly young people into urban farmers and food entrepreneurs. While there is no age limit, the farmers in the first group range from 22 to 30 years old, Mr. Peggs said. Growing vegetables inside windowless metal boxes, however, has its difficulties. Critics of vertical farming point to extreme energy use, high price points of the final product, and the limited selection of vegetables that can be grown this way. Mr. Peggs acknowledges these challenges but says they can be overcome with rapidly improving technology. LED lights are quickly becoming more efficient, for instance, and the addition of solar panels could take the containers entirely off the grid in coming years, he noted.

Square Roots started last summer with $3.4 million raised from a first round of investors, Mr. Peggs, said. The company spent more than $1 million building the farm—buying and setting up 10 shipping containers from a Boston company called Freight Farms for more than $80,000 each. Farming began in November. Each entrepreneur selected was required to invest several thousand dollars in his or her farm, refundable at the end of the year, Mr. Peggs said. Nine of the farmers received microloans from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The new farmers took an eight-week course, learning how to cultivate hydroponic crops, and then decided what vegetables to grow and how to sell them. The farmers soon began cultivating crops such as watercress, basil, lettuces, Swiss chard, bok choy, and cilantro.

Square Roots plans to make money through a revenue-sharing model, taking a cut of whatever income the 10 farmers generate. Along the way, each entrepreneur is given mentoring and guidance on farming, as well as branding and marketing, Mr. Peggs said. The company is generating revenue, but is deliberately not running at a profit, to establish the platform, he said. Mr. Peggs declined to detail the profit share with farmers.

One of the farmers, Erik Groszyk, said recently that he had only just started making money from his farm. He raises arugula, mustard greens, and tatsoi, fueled by a $12,000 microloan from the USDA. He said he sells his produce directly to restaurants and is part of a companywide sales program called Farm-To-Local, a subscription service that delivers bagged greens to office workers at their desks around New York City.

Packets of salad greens—about the size of a bag of chips—cost between $5 and $7. At that price point—higher than New Yorkers might find at their supermarket—Square Roots won’t achieve its goal of making fresh local food accessible to everyone. But Mr. Peggs is quick to point out that Starbucks sells millions of coffee drinks a day at a similar cost. Neil Mattson, a professor of plant science at Cornell University, notes there are other drawbacks to shipping-container farms, such as a carbon footprint two to three times greater than a greenhouse because of the large amount of electricity required to run the lighting and ventilation systems.

Mr. Peggs said each shipping container costs about $1,500 per month to operate, with electricity and rent as the biggest expenses at about $600 each. Transportation costs are low because most deliveries are made by bike or subway. Mr. Mattson said greenhouses, which offer the same control of growing conditions as a vertical farm and can include LEDs to supplement sunlight, are often a better option for producing crops in or near urban areas. Mr. Peggs, however, contends that shipping-container farms are still the best option for Square Roots, which is less interested in scaling up to large operations that can replace industrial farms, and more interested in cultivating many farmers working smaller operations, so everyone knows their grower and where their foods comes from.

These 5 Technologies Are On The Verge of Massive Breakthroughs

These 5 Technologies Are On The Verge of Massive Breakthroughs

A new report highlights a few promising fields that could explode in the near future.

By Kevin J. Ryan |Staff writer, Inc.@wheresKR

An Aerofarms employee uses a scissor-lift to check the vertically-growing greens within the company's Newark, NJ headquarters.

CREDIT: Ellise Verheyen

Here's a glimpse of what the future will look like.

This week, Scientific American published its annual report on emerging technologies. The list is a compilation of what the publication calls "disruptive solutions" that are "poised to change the world." To qualify, a particular technology must be attracting funding or showing signs of an imminent breakthrough, but must not have reached widespread adoption yet.

Here are a few of the cutting-edge technologies that made the list--and the companies that are already making strides with them.

1. Noninvasive Biopsies

Cancer biopsies, which entail removing tissue suspected of containing cancerous cells, can be painful and complicated. Analyzing the results takes time. Sometimes, the tumor can't be reached at all.

Liquid biopsies could be the solution to all those issues. By analyzing circulating-tumor DNA--a genetic material that travels from tumors into the bloodstream--the technique can detect the presence of cancer and help doctors make decisions about treatment. It can potentially go even further than traditional biopsies, identifying mutations and indicating when more aggressive treatment is necessary. Grail, which spun out from life sciences company Illumina earlier this year, currently has $1 billion in funding from investors including Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates. The startup is working toward developing blood tests that could detect cancer in its earliest stages.

2. Precision Farming

Farming doesn't have to be an inexact science. Thanks to artificial intelligence, GPS, and analytics software, farmers can now be more precise in managing their crop yields. This makes agriculture a more efficient operation, which is especially critical in parts of the world where resources or climate aren't conducive to growing. Indoor farming startups including Aerofarms, Green Spirit Farms, and Urban Produce all closely analyze their crops using these types of tools to maximize output and flavor. Blue River Technology and others use computer vision to cut down on wasted fertilizer--sometimes by 90 percent.

3. Sustainable Design of Communities