Fresh Veggies Grown Close to Home, Without Pesticides — And Without Dirt

Fresh Veggies Grown Close to Home, Without Pesticides — And Without Dirt

Civic Farms touts having “pioneered the vertical farming industry.” The company says its proprietary growing systems, licensed patented technologies, and optimized processes for cultivation and harvesting processes maximize the efficiency and efficacy of growing indoors.

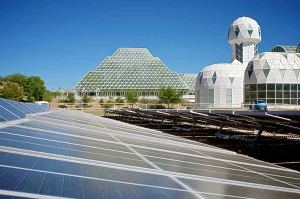

TUCSON (CN) – An ambitious project of emerging agricultural technologies that produce food without soil is taking shape at Biosphere 2, the University of Arizona’s research complex north of Tucson.

Civic Farms, an Austin-based company, this summer will start building a vertical farm in one of two 20,000-square-foot domes – or “lungs” – that regulated pressure inside a sealed glass structure during experiments to study survivability in the 1990s.

The company will invest $1 million to renovate the Biosphere’s west lung, unused for years, and outfit the space with stacked layers to grow soil-free plants in nutrient-laden circulating water under artificial lights.

At full capacity, the vertical farm will produce 225,000 to 300,000 lbs. a year of leafy greens and herbs such as lettuce, kale, arugula and basil, said Paul Hardej, CEO and co-founder of Civic Farms.

“Biosphere itself is a fantastic facility and food production is a big part of what it was originally intended to do,” he said.

As the world population continues to rise, particularly in cities, along with consumer interest in the origins of food, vertical farming is gaining traction as a commercially viable way to increase crop production in a fully controlled indoor environment.

“People want know what they eat and what’s in their food and how healthy and good it is for them,” Hardej said. “Growing food in city centers or close to city centers where people live makes perfect sense.”

Under an agreement with the university, Civic Farms will grow crops in half the space it will lease for $15,000 annually. Research and scientific education will comprise the other half and the company will contribute $250,000 over five years for those efforts.

“We envision that a portion of the lung will be open and accessible to the public so people can come in see how and what it is to have a vertical farm,” said John Adams, the Biosphere’s deputy director.

Civic Farms touts having “pioneered the vertical farming industry.” The company says its proprietary growing systems, licensed patented technologies, and optimized processes for cultivation and harvesting processes maximize the efficiency and efficacy of growing indoors.

The Biosphere already draws nearly 100,000 annual visitors to expansive grounds originally intended to showcase a self-sustaining replica of Earth, or Biosphere 1.

Set on a 40-acre campus against the backdrop of the rugged Santa Catalina Mountains, the Biosphere’s 91-foot steel-glass structure serves as a global ecology laboratory enclosing an ocean, mangrove swamp, rain forest, savanna and coastal desert.

In the early 1990s, a crew of scientists was locked inside the sealed structure in privately funded scientific experiments designed to explore survivability with an eye toward space colonization. Problems with the experiments and management disputes eventually halted the highly public venture.

The University of Arizona took over the property, about 30 miles north of Tucson in the town of Oracle, in 2011.

The Biosphere’s Adams views the planned vertical farm as a good fit for research initiatives.

“For the next 10 years, Biosphere’s focus is very much on food, energy, water – and the nexus,” he said.

Civic Farms’ Hardej said the university’s myriad resources were strong incentives for his company’s new enterprise in Arizona. A big plus are the concepts being developed at the university’s Controlled Environment Agriculture Center on North Campbell Avenue, where scientist Murat Kacira grows leafy crops indoors under LED lights.

“There’s so much interest in this technology platform because it provides the capability to grow food with consistency,” Kacira, a professor of agricultural-biosystems engineering, said of vertical farm systems.

Inside the lab where lettuce and basil grow in hydroponic beds under the glow of blue and red LED lights, Kacira and his students monitor the conditions in which seedlings mature.

“The environment is fully controlled in terms of providing temperatures needed, or humidity needed, carbon dioxide or the light intensity or the quality needed for the plant production,” Kacira said.

Not being at the mercy of Mother Nature makes vertical farms more productive than conventional farms, as well as more efficient at using natural resources such as water, he said. “You’re circulating it inside the environment, so the efficiency is much higher.”

Still, Kacira said, the technology is energy-intensive, given the use of artificial lights and the need to condition the environment. And although large-scale commercial operations are relatively rare, he said, advances in scientific research and the high-tech industry are making it a feasible platform to help supplement food production in cities.

“Our food transportation is coming from long distances, and by the time it gets to the consumer, especially leafy crops, the freshness may not be there,” Kacira said.

Vertical farms are a relatively new concept that hold great potential, Hardej said it. With a projected global population of 9.5 billion, mostly urban, by 2050, he views vertical farms as an increasingly important part of the world’s food system.

His own vertical farm aims to provide the Tucson and Phoenix markets with high-quality produce grown sustainably and without pesticides, Hardej said.

In time, he plans to incorporate more energy-efficient solutions into his operation.

“For commercial scale, those technologies still need to be perfected,” he said.

His company plans to begin growing the leafy greens by year’s end.