With Shipping Container, Fidelis Greens Fuses Technology, Farming

With Shipping Container, Fidelis Greens Fuses Technology, Farming

Credit: Josh Mandell, Charlottesville Tomorrow

Fidelis Greens aims to sell its fresh and sustainably produced microgreens to farm-to-table restaurants in Central Virginia year-round. From left: Kyle McCrory, Andre Ortiz, Joel Shindeldecker

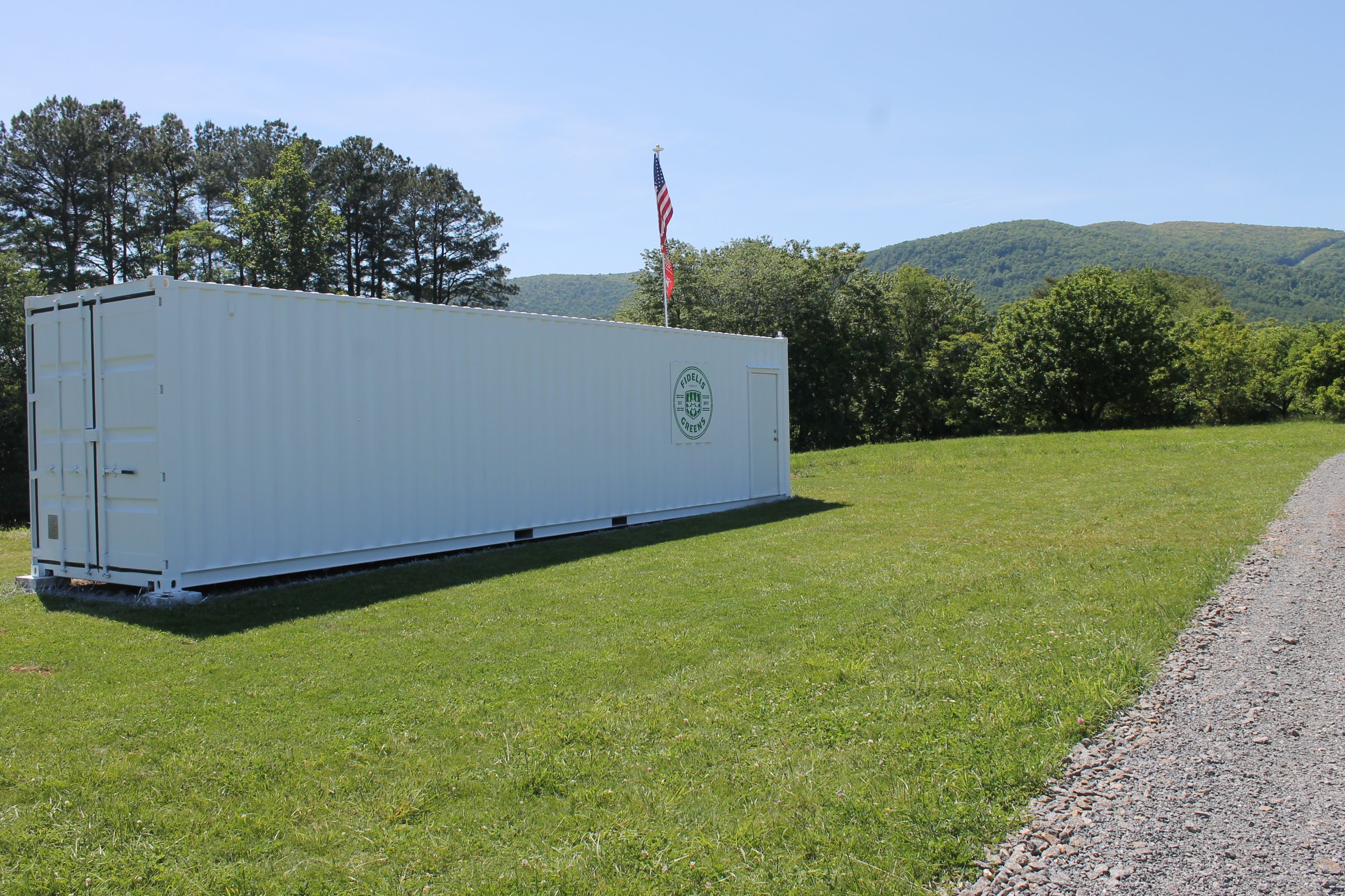

Fidelis Greens, an agricultural startup near Crozet, is located on a picturesque 154-acre farm. But most of its work is confined to a much smaller space.

The company grows tiny, flavorful microgreens inside a repurposed steel shipping container, including arugula, amaranth, mustard greens and a "spicy mix" of several varieties.

The business aims to sell its fresh and sustainably produced microgreens to farm-to-table restaurants in Central Virginia year-round, giving chefs a local alternative to greens shipped from California and Mexico during the winter.

Joel Shindeldecker, who leads the company's marketing and sales, said the shipping container's hydroponic growing system can equal the output of a 2.5-acre plot of land, but requires much less water and allows for more consistent quality.

Fidelis Greens harvested its first microgreens earlier this year and has plans to share its open-source approach to indoor, "vertical" farming. They will be joined in the Charlottesville-area market by Freight Farms, a Boston-based startup that is bringing shipping container growing units to the Barracks Road and 29th Place shopping centers.

Fidelis Greens co-founder Randy Caldejon said his company has designed a simple, low-cost model for shipping container farms, while using computer technology to perfect the growing process.

"I'm fascinated by ways that farmers can optimize productivity and sustainability with software and machine learning," he said.

Caldejon previously co-founded nPulse Technologies, a network security firm that was acquired by FireEye in 2014 for more than $60 million.

Caldejon now supervises Fidelis Farm & Technologies, an incubator for agricultural startups at his Albemarle County estate. Fidelis Greens is the incubator's first venture and the startup has five team members who serve the company in multiple roles.

Kyle McCrory, an Albemarle native, brought expertise in industrial design and horticulture to the company. After graduating from Virginia Tech in 2010, McCrory started his career at Gotham Greens, which operates several large greenhouses in New York City and Chicago.

Credit: Josh Mandell, Charlottesville Tomorrow

Fidelis Greens currently specializes in four kinds of microgreens: arugula, amaranth, mustard greens and a “spicy mix” of several varieties.

"It was a great experience to be part of one of the pioneers in this field," he said. "I wanted to bring what I learned back home."

Fidelis Greens' shipping container farm became fully operational in mid-March, when many traditional farmers in Virginia feared a late winter storm could jeopardize the upcoming growing season.

Andre Ortiz said Fidelis Greens spent a few thousand dollars on a shipping container that had only gone through one voyage, even though heavily used containers can be purchased for much less.

The team insulated the container with spray foam, and built a hydroponic growing system out of materials that can be found at most hardware stores.

The container currently has six shelves installed on one side of the container that fit a total of 216 standard gardening trays. Shindeldecker said the company hopes to add six more shelves to the other wall.

Once seeds sprout into microgreens in seven to 10 days, Fidelis Greens delivers trays of live greens to restaurants that chefs can clip and serve as needed. The reusable trays avoid the waste generated by plastic clamshell packaging.

Shindeldecker said one of Fidelis Greens' strengths is the shipping container's automated climate control system, which combines open-source computer hardware and software with additional programming by Caldejon.

Caldejon's software automatically adjusts the container's air conditioning unit and fans to keep the temperature in the container constant at 77 degrees during the day, and 65 at night. It reads data from sensors placed throughout the container to regulate humidity, vapor pressure deficit and carbon dioxide levels.

Fidelis Greens staffers usually spend no more than two hours tending to the greens each day. They can monitor and adjust the growing conditions online when they are away from the farm.

McCrory said the company is in a "fast-paced learning mode," finding new ways to improve the quality of the product and distributing samples to restaurants in Crozet and Charlottesville.

Six restaurants have committed to regular deliveries from Fidelis Greens this summer, Shindeldecker said.

Kardinal Hall, a restaurant and beer garden in Charlottesville, uses Fidelis Greens' arugula as a garnish for salads and sausages.

"Putting a little arugula in everything is so 'in' right now," said Allison Hurt, Kardinal Hall's marketing manager. "We are all about trying new things, especially when they are locally made."

Kardinal Hall chef Jeffery Burgess said he has been using one or two trays of the arugula each week. "I think it's a great product," he said.

Caldejon said he will keep the design of Fidelis Greens' shipping container farm in the public domain, and hopes to publish a construction manual later this year so other organizations and individuals can replicate it.

Caldejon said military veterans, especially those suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, could benefit from the opportunity to start their own shipping container farm.

Caldejon, Ortiz and fellow co-founder James Edward King are veterans of the U.S. Marine Corps. The Marines motto, "Semper Fidelis," inspired the name of their company.

"It opens up an opportunity [for veterans] to be gainfully self-employed in an environment with relatively low stress," Caldejon said.

"High-tech can be intimidating, but we are incorporating technology in a way that makes it more approachable," McCrory said.

The Fidelis Greens team includes three veterans of the U.S. Marine Corps, whose flag flies above the shipping container farm. Credit: Josh Mandell, Charlottesville Tomorrow.