Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Shanghai Goes Green: District With Towering Vertical Farms May Become A Reality In The Near Future

Shanghai Goes Green: District With Towering Vertical Farms May Become A Reality In The Near Future

Saturday, May 20, 2017 by: Frances Bloomfield

Tags: agriculture, China, Shanghai, Sunqiao, Urban agriculture

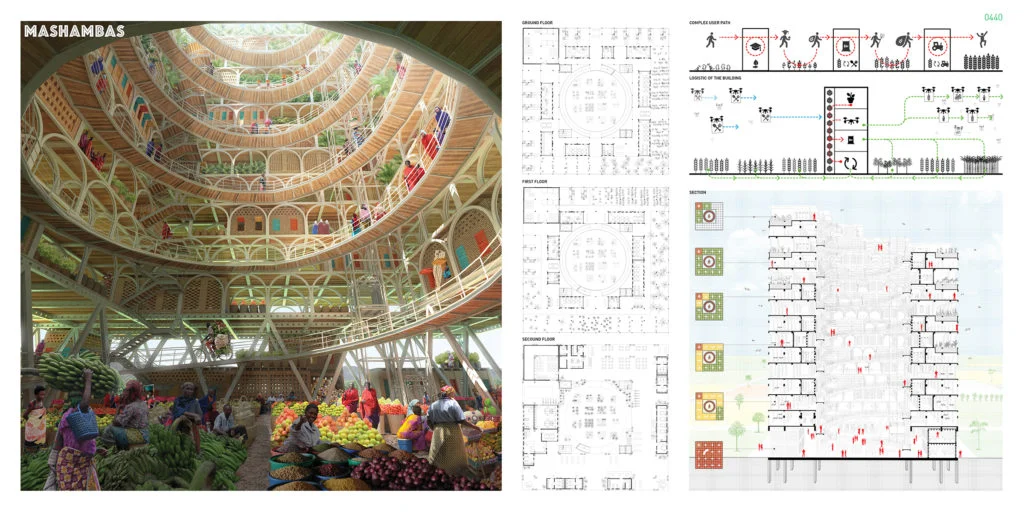

(Natural News) From towering symbols of urbanization, the skyscrapers of Shanghai may soon become agrarian wellsprings. Such is the plan for Sunqiao Urban Agricultural District, a 250-acre district where people will live, work, and shop while surrounded by massive vertical farming systems. Sasaki, the US-based architectural firm behind this bold undertaking, has called Sunqiao “a new approach to urban agriculture” and a “playful, and socially-engaging experience that presents urban agriculture as a dynamic living laboratory for innovation and education.”

Set to be constructed between Shanghai Pudong International Airport and the center of the city, Sunqiao will include all the civic essentials like housing, restaurants, and stores. Amidst all these, however, will be floating greenhouses, seed libraries, and algae farms. These will serve as an expansion of a Shanghai government project that began in the mid-1990’s, wherein a 3.6-square-mile area of the city was designated for agricultural production. Prior to Sasaki’s involvement, only three single-story greenhouses had been built.

The design firm hopes to change that. One major intended use for these is to meet the food requirements of Shanghai’s 24 million-strong population. Leafy greens like kale, bok choi, watercress and spinach make up a large part of the vegetables consumed by the Shanghainese on a daily basis; these same leafy greens do well in simple agricultural setups and require little attention to thrive, making them “an excellent choice for hydroponic and aquaponic growing systems.” Furthermore, these leafy greens are light in weight and grow quickly, making them highly-efficient, economically-viable choices for cultivation as well as food production. Michael Grove, director of Sasaki’s Shanghai office, stated that the district may also have vertical aquaponic fish farms in the future. (Related: The Technologies Making Vertical Farming a Reality)

Sasaki has even called Shanghai “the ideal context for vertical farming”, with its soaring land prices that make building up rather than building out the more prudent option. This goes hand-in-hand with the fact that over 13 percent of China’s total Gross Domestic Product comes from the country’s agricultural sector — the same agricultural sector that feeds 20 percent of the world’s population. Compare this to the United States, of whose agriculture industry only contributes to 5.7 percent of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product.

With over 200,000 kilometers of the country’s arable land now suffering from soil pollution, and 123,000 kilometers of farmland since lost to urbanization, the vertical farms of Sunqiao will become more important than ever. The threats of water shortages, deforestation, and many other complications that continue to affect small farms may soon be things of the past as investments are poured into the modernization and mechanization of the agricultural sector.

According to Sasaki, construction will begin in late 2017 or early 2018. The measurements for Sunqiao are as follows: 753,00-square feet of vertical farms, 717,000-square feet of housing, 138,000-square feet of commercial space, and 856,000-square feet of public space. Development and maintenance will be done by Shanghai Sunqiao Modern Agriculture United Development Co. Ltd., a Chinese company that develops and produces fertilizer. The company will be working together with local planning officials, reported Futurism.com.

Of the project, Sasaki has emphasized the need to balance the agrarian with the metropolitan, stating: “As cities continue to expand, we must continue to challenge the dichotomy between what is urban and what is rural.”

Japan To Prune Taxes In Hopes of Growing Farm Business

May 22, 2017 12:50 pm JST

Japan To Prune Taxes In Hopes of Growing Farm Business

Government panel proposes cutting levies on high-tech indoor agriculture

An indoor farm grows lettuce in Kyoto Prefecture.

TOKYO -- The Japanese government is moving to cut taxes on operators of high-tech indoor farms to encourage more businesses to enter the sector and turn "smart agriculture" into a growth industry.

Under current law, when a company paves over farmland to build an indoor farm, the land is no longer treated as agricultural. That makes it subject to much higher property taxes. The government will seek to reduce the tax burden by proposing that such land continue to be treated as farmland.

The cabinet's council on regulatory reform plans to include the proposal in a report to be submitted to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on Tuesday. The council hopes to start full-scale discussions on the issue within this fiscal year, which ends in March 2018.

Under the proposal, the agriculture ministry will revise the agricultural land act and the definition of farmland so that operators of indoor farms do not face a high tax burden.

According to the internal affairs ministry, the property tax levied on land used for indoor farming averaged 12,000 yen ($107) per 10 ares for the year through March 2016. That is more than 10 times the 1,000 yen rate for farmland. Industry backers, including the Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Osaka Prefecture, have been calling for deregulation.

New cultivation technologies make it possible to grow high-quality vegetables indoors. This allows indoor farmers to precisely control the environment -- including temperature and humidity, as well plant nutrition -- whatever the weather outside is doing.

Difficulties in financing indoor farming projects, including high startup costs and taxes, have kept businesses from entering the sector. According to a 2016 survey by the Japan Greenhouse Horticulture Association, about 40% of indoor plant growers were operating in the red.

The Abe government has called expanding Japan's farming industry through deregulation a key growth strategy.

This Uptown Urban Farm Is Growing Career Opportunities for Kids Throughout the City | Edible Manhattan

This Uptown Urban Farm Is Growing Career Opportunities for Kids Throughout the City | Edible Manhattan

By Sarah McColl

Photos by Corinne Singer

“We want to capture whatever spark the children have and try to nurture it, even if it’s well outside the realm of agriculture,” Vincent says.

Up the street from the Apollo Theater, a lot on West 134th Street was once home to prowling neighborhood cats, abandoned engine parts and men playing dominos. With the vision of founder Tony Hillery, the kids of Harlem Grown’s youth farm, a truckload of soil from Home Depot and 400 strawberry plants, the makeshift junkyard has been a blooming Eden since 2011. Now, an arbor casts a low ceiling of leafy shade and a sign warns with a wink that, “Trespassers will be composted.”

The mission of this urban youth farm has never been rootbound. While lessons in nutrition and agriculture happen over hydroponics, and conversations about economic, social and food justice unfold between the garden rows, Harlem Grown is also connecting schoolchildren with professional mentors, internships and career connections.

“We’re trying to use the farms and food as a vehicle to inspire change beyond the plate,” says development director Vanessa Vincent. “We’ve been able to connect our youth to opportunities beyond their wildest dreams.”

Related:

Five Questions with Tony Hillery, Founder of Harlem Grown | Food Tank

Edible Manhattan: A Self-Guided Dominican Food Tour of Washington Heights & Inwood

At Harlem Shambles, The Meat is Worth the Trip | Edible Manhattan

Under the Tracks and Off the Grid, Urban Garden Center Rises Up | Edible Manhattan

Uptown, a Dominican Confection Makes Life Three Times Sweeter | Edible Manhattan

We invite you to subscribe to the weekly Uptown Love newsletter, like our Facebook page and follow us on Twitter & Instagram or e-mail us at UptownCollective@gmail.com.

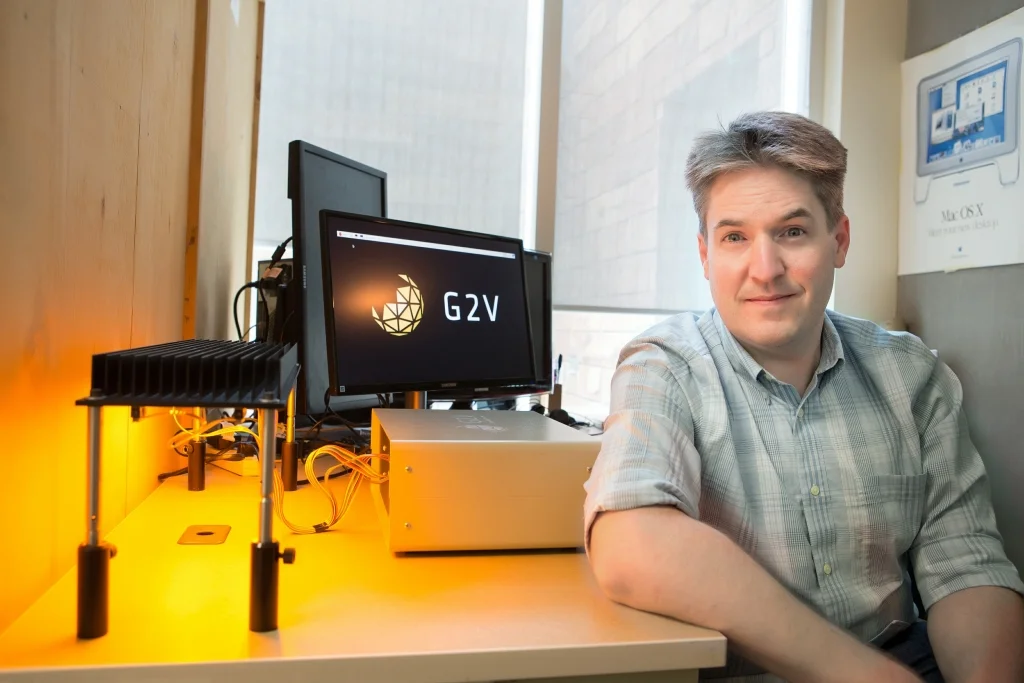

G2V Optics: Shining A Light On Indoor Farming

G2V Optics: Shining A Light On Indoor Farming

Anyone who’s lived through winter in Northern Alberta knows how few precious daylight hours there are in the winter months, and how short the growing season is once spring finally arrives. Now imagine being able to grow plants all year round.

G2V Optics is improving the technology that makes it possible to grow plants indoors by mimicking the sunlight conditions of locations around the world. Its grow lights offer as close a match to natural sunlight as you can get, along with the ability to replicate sunlight conditions for any location on earth.

The venture was founded by Michael Taschuk, a former research associate at the University of Alberta. “We started with solar cell testing and plant research for indoor growing and vertical farming,” he explains. “We were trying to make better solar cells, but were frustrated with the testing equipment available. It was clear that there was a better way to do it.”

The small market for solar cell testing equipment made it an unviable business venture, but food production and indoor farming remains a much bigger problem going forward.

“It was very attractive to see if we could do something there,” said Michael.

The technology uses different coloured LEDs that are precisely controlled to mimic natural sunlight.

Now just over two years old, G2V Optics made a home out of TEC Edmonton’s coworking space, TEC Innovation District. Going in, Michael wanted two things: interactions with other early-stage businesses, and coaching.

“It’s been really good, Michael says. “I’ve had really detailed coaching, which has been enormously helpful.”

Since Michael is trained as a scientist, his biggest challenge remains learning to think of G2V Optics as a business first and foremost, rather than a technical problem. Luckily, marketing help from TEC Edmonton’s Executives in Residence is helping.

“[My coach] is good at challenging my thinking and is able to frame marketing in a way that I can understand,” Michael explains.

Going forward, Michael plans to move G2V Optics into grow lights for commercial applications, farms, research space, or even windowsill growing – he’s already received a lot of interest from the orchid growing community.

We wish Michael and the best as he continues to grow G2V Optics out of TEC Innovation District!

Has This Silicon Valley Startup Finally Nailed The Indoor Farming Model?

Has This Silicon Valley Startup Finally Nailed The Indoor Farming Model?

Indoor farming is a trendy startup space, but many of those ventures have recently failed. Plenty thinks its technology, model, and timing mean it’s the place that will finally turn greens into green.

“We’re working to ensure that all of our food gets to the store within hours, and not days or weeks.” [Photo: courtesy Plenty]

“I like to call this the cathedral.” So says Matt Barnard, CEO and cofounder of the vertical farming startup Plenty. We’re standing in a room at the company’s headquarters in a former electronics distribution center in South San Francisco, staring up at glowing, 20-foot high towers filled with perfectly formed kale and herbs.

The company isn’t the first to build an indoor urban farm in a warehouse. Aerofarms, for example, grows greens in a 70,000-square foot former steel factory in Newark, New Jersey. Nearby, Bowery, another tech-filled indoor farm, grows what it calls “post-organic,” pesticide-free produce. But Plenty, which has received $26 million in funding to date from investors such as Bezos Expeditions and Innovation Endeavors, believes that it has the technology to grow food more efficiently–at the same cost or less than crops grown in the field–so it can more easily scale up to supply supermarkets around the world.

Inside another gleaming white room, wearing a food processing uniform and gloves, Barnard reaches up and picks rare varieties of basil, chives, a mustard green called mizuna, red leaf lettuce, sorrel, and Siberian kale, eating each and handing me samples as he talks. None of these are available in the average grocery store, because they wouldn’t survive the supply chain. Most produce available now has been bred or engineered to last through rough handling in distribution centers and long distances in trucks–not for taste. The heirloom seeds that Plenty uses, which were bred for taste, are more delicate.

“When you’re not outside and you’re no longer constrained by the sun, you can do things that make it easier for humans to do work and work faster, and for machines to work faster.” [Photo: courtesy Plenty]

“What the technology that we’ve developed enables us to do is essentially grow varietals that are just better than what’s in the store today,” he says. “What’s in the store today is the best that we can grow with a 3,000-mile supply chain. But the best that we can grow with a 50-mile supply chain is stunningly better. That’s why we’re working to ensure that all of our food gets to the store within hours, and not days or weeks.”

Unlike most other indoor farming companies, which typically grow food in rows on shelves, Plenty grows food vertically–each plant popping out of the side of a tall, skinny tower. Lights are also arranged vertically rather than pointing down from above. (BetterLife Growers, which plans to open in Atlanta this fall and provide jobs for underserved communities, is another example of a company that uses a vertical growing system; on a smaller scale, Tender Greens is using vertical systems to grow salad ingredients at some of its restaurants).

“When you’re not outside and you’re no longer constrained by the sun, you can do things that make it easier for humans to do work and work faster, and for machines to work faster,” says Barnard. “You can do things like use gravity to feed the water and the nutrients rather than having to use pumps, so you can be more energy efficient.” The farms are less expensive to build than other configurations. They also grow more food in less space than competitors like Aerofarms or Bowery. While Aerofarms claims to grow 130 times more produce than conventional farming in a given area, Plenty claims to grow 350 times more than conventional farming.

“Growing at a small scale, you can’t get to the labor efficiencies that you need. It requires, in essence, too many people.” [Photo: courtesy Plenty]

“Shifting to the vertical plane makes us usually four to six times more efficient spatially than a stacked system–[like] someone like Aerofarms or someone like Bowery,” says cofounder and chief science officer Nate Storey, who previously founded another vertical farming company called Bright Agrotech. “Ultimately, we’re able to have a much higher space-use efficiency than we could if we were trying to stack our equipment. So everything in the system serves that end, which is how can we pack more plant production into the space without sacrificing plant health.”

The design allows for what the company calls “field-scale architecture”–rooms that can produce the same output as a fairly large farm field in a tiny space. Some early companies in the urban farming industry were constrained by smaller production.

“Small-scale growing in 2017 is not a profitable enterprise, and there are a lot of systemic reasons for that that aren’t going to change,” says Barnard. “Growing at a small scale, you can’t get to the labor efficiencies that you need. It requires, in essence, too many people.”

Early indoor farming companies–like Chicago’s FarmedHere, which was once the largest indoor farm in the country and had hopes of national expansion but shut down in January 2017–also struggled with the cost of components like LED lights, which have dramatically fallen in the last several years. Podponics, an Atlanta indoor farming startup, raised $15 million from investors, but went bankrupt in 2016 after struggling with the economics of its system, particularly the cost of labor. Local Garden, a greenhouse in Vancouver, went bankrupt in 2014 after issues with productivity and access to capital. Others, like BrightFarms, had to rework their initial strategy because of the high cost and challenges of working on urban land. But as technology has improved, other indoor farming companies are growing. AeroFarms, with $61.5 million in investment, has projects in development on four continents, including a farm in Camden, New Jersey, near its first location, and is on track for its plans to build at least 25 more farms by 2020. Urban Produce, a vertical indoor farm in Irvine, California, hopes to expand to 25 locations in five years.

“There’s a timing aspect to this,” Barnard says. “Our technology is necessary to get to the right set of economics. But it’s also not fully sufficient. In other words, it enables us to capitalize on what’s happening in the commoditization in other areas. Utility computing, IoT, machine intelligence, wasn’t effective enough five years ago, much less affordable. Seven years ago . . . you would have spent 64 times more to buy the same amount of LED lights. So we’ve built into our design the ability to take advantage of advances in that field.”

The company continually iterates on the design, tweaking the placement of lights or plumbing or how the towers are moved in and out of a room in order to improve cost or productivity or flavor. A custom designed “growth medium” made from recycled plastic bottles takes the place of soil, holding roots in place, delivering nutrients, and hosting microbes.

The system makes it economic to grow crops other than leafy greens, which have been the mainstay of most indoor farms to date. Strawberries may come next, and perhaps tomatoes and cucumbers, all grown in varieties that naturally have more flavor than standard offerings in stores, and preserve that flavor because of the short supply chain.

“The promise that we’re making to customers is that it’s literally days faster.” [Photo: courtesy Plenty]

The company plans to build its farms next to large cities, but not directly inside, to best fit in existing supply chains that have distribution centers on city limits. “If you want to be delivering a large amount of super-amazing tasting produce to a large grocery store in the middle of a city, you want to be in the distribution center that feeds that grocery store,” Barnard says. “Because otherwise, it’s going to go back out of the city to the distribution center and then back to the store. And now you’ve cost [yourself] hours and maybe even a day or two. The promise that we’re making to customers is that it’s literally days faster.”

The taste is noticeably different. Rick Bayless, the Frontera chef, tried the produce at Google, where the founders started testing their core technology in a demonstration farm in 2014 (that farm is still supplying greens to Google’s cafeteria, though Plenty is not running it). “When I visited Plenty’s pilot farm, I was skeptical,” he says. “I’d had produce before that was grown under lights. And it always disappointed: weak in flavor and texture, like a shadow of the original. But that day at Google, I tasted something different. True and vibrant flavors, textures like I’m used to in field-raised greens and fruits, unusual varieties I’d only expect from really savvy growers. I knew these guys were onto something.”

By delivering food to customers more quickly, the process preserves both flavor and nutrients (after a week in the supply chain, produce can lose as much as 55% of nutrients like vitamin C). Like other indoor farming, the technology also saves arable land; Plenty says it can grow up to 350 times more produce in the same amount of space as conventional farming, with 1% of the water. In a sealed environment, there are so few pests that the company can use ladybugs to deal with them rather than pesticides. The process also cuts the cost and pollution associated with a typical supply chain.

Barnard says that “30% to 45% of the value [of produce] at shelf is trucks and distribution centers.” He adds, “And that to us doesn’t make any sense when we can be getting people better food that tastes better, is more nutritious, with less pesticides. I like to call it food for people, not trucks.”

While early indoor farming was much more energy-intensive, the improving efficiency of LED lights means that the new system can actually have a smaller carbon footprint than farming in the field, at least for certain crops. (This calculation takes other impacts into account, including the carbon footprint of transportation and distribution in traditional farming and the impact of food waste in the supply chain.) The production facilities could potentially also run at least in part on on-site renewable energy like solar power.

“The fact that we can compete with the field on cost is great, but what is, of course, more exciting is that we’re not just competing on real costs, we’re competing on carbon cost,” says Storey. Eventually, he believes that many varieties of food will be more sustainable to grow indoors than out.

The company envisions building farms in every major metropolitan area around the world. After the launch in San Francisco in 2017, other major markets will follow in 2018. “People are going to see that the nutrient-rich food in their diet–fruit and vegetable–is going to start tasting better, and it’s going to be grown in farms like this,” says Barnard. “And it’s going to happen with stunning swiftness, because we’re now at the point where we can get this into everyone’s budget.”

PurePonics Is Planted In Geelong, Victoria

PurePonics Is Planted In Geelong, Victoria

Last Friday the PurePonics team planted the first crop in the brand new aquaponics facility in Geelong, Victoria.

A great milestone and now our sights are set on the first harvest in around 5 weeks time and getting the finest ingredients into the hands of our customers.

Thanks for following along with our progress and we look forward to providing plenty of interesting and exciting news around food production, urban farming and the beauty of aquaponics in protected cropping.

Follow us on Facebook - PurePonicsAUS

Where the Mouths Are: A Farm Grows In The City

May 21, 2017

Where the Mouths Are: A Farm Grows In The City

Relatively inexpensive space in underutilized urban areas, close to where the majority of the population will live for the foreseeable future.

It makes too much sense not to seize the opportunity. JL

Betsy McKay reports in the Wall Street Journal:

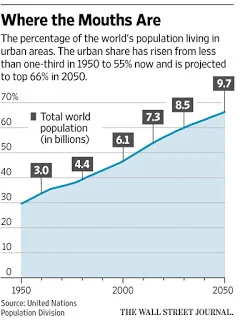

The world’s population is to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, 33% more than today. Two-thirds of them are expected to live in cities. Getting food to people who live far from farms is costly and strains natural resources. Startups and city authorities are finding ways to grow food closer to home. High-tech “vertical farms” are sprouting in rows, fed by water and LED lights, customized to control size, texture or other characteristic of a plant.

Billions of people around the world live far from where their food is grown.

It’s a big disconnect in modern life. And it may be about to change.

The world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, 33% more people than are on the planet today, according to projections from the United Nations. About two-thirds of them are expected to live in cities, continuing a migration that has been under way around the world for years.

That’s a lot of mouths to feed, particularly in urban areas. Getting food to people who live far from farms—sometimes hundreds or thousands of miles away—is costly and strains natural resources. And heavy rains, droughts and other extreme weather events can threaten supplies.

Now more startups and city authorities are finding ways to grow food closer to home. High-tech “vertical farms” are sprouting inside warehouses and shipping containers, where lettuce and other greens grow without soil, stacked in horizontal or vertical rows and fed by water and LED lights, which can be customized to control the size, texture or other characteristic of a plant.

Companies are also engineering new ways to grow vegetables in smaller spaces, such as walls, rooftops, balconies, abandoned lots—and kitchens. They’re out to take advantage of a city’s resources, composting food waste and capturing rainwater as it runs off buildings or parking lots.

“We’re currently seeing the biggest movement of humans in the history of the planet, with rural people moving into cities across the world,” says Brendan Condon, co-founder and director of Biofilta Ltd., an Australian environmental-engineering company marketing a “closed-loop” gardening system that aims to use compost and rainwater runoff. “We’ve got rooftops, car parks, walls, balconies. If we can turn these city spaces into farms, then we’re reducing food miles down to food meters.”

Moving beyond experiments

Urban farming isn’t easy. It can require significant investment, and there are bureaucratic hurdles to overcome. Many companies have yet to turn a profit, experts say. A few companies have already failed, and urban-farming experts say many more will be weeded out in the coming years.

But commercial vertical farms are well beyond experimental. Companies such as AeroFarms, owned by Dream Holdings Inc., and Urban Produce LLC have designed and operate commercial vertical farms that aim to deliver supplies of greens on a mass scale more cheaply and reliably to cities, by growing food locally indoors year round.

At its headquarters in Irvine, Calif., Urban Produce grows baby kale, wheatgrass and other organic greens in neat rows on shelves stacked 25 high that rotate constantly, as if on a conveyor belt, around the floor of a windowless warehouse. Computer programs determine how much water and LED light the plants receive. Sixteen acres of food grow on a floor measuring an eighth of an acre.

Its “high-density vertical growing system,” which Urban Produce patented, can lower fuel and shipping costs for produce, uses 80% less fertilizer than conventional growing methods, and generates its own filtered water for its produce from humidity in the air, says Edwin Horton Jr., the company’s president and chief executive officer.

“Our ultimate goal is to be completely off the grid,” Mr. Horton says.

The company sells the greens to grocers, juice makers and food-service companies, and is in talks to license the growing system to groups in cities around the world, he says. “We want to build these in cities, and we want to employ local people,” he says.

AeroFarms has built a 70,000-square-foot vertical farm in a former steel plant in Newark, N.J., where it is growing leafy greens like arugula and kale aeroponically—a technique in which plant roots are suspended in the air and nourished by a nutrient mist and oxygen—in trays stacked 36 feet high.

The company, which supplies stores from Delaware to Connecticut, has more than $50 million in investment from Prudential, Goldman Sachs and other investors, and aims to install its systems in other cities globally, says David Rosenberg, its chief executive officer. “We envision a farm in cities all over the world,” he says.

AeroFarms says it is offering project management and other services to urban organizations as a partner in the 100 Resilient Cities network of cities that are working on preparing themselves better for 21st century challenges such as food and water shortages.

The bottom line

Still, these farms can’t supply a city’s entire food demand. So far, vertical farms grow mostly leafy greens, because the crops can be turned over quickly, generating cash flow easily in a business that requires extensive capital investment, says Henry Gordon-Smith, managing director of Blue Planet Consulting Services LLC, a Brooklyn, N.Y., company that specializes in the design, implementation and operation of urban agricultural projects globally.

The greens can also be marketed as locally grown to consumers who are seeking fresh produce.

Other types of vegetables require more space. Growing fruits like avocados under LED light might not make sense economically, says Mr. Gordon-Smith.

“Light costs money, so growing an avocado under LED lights to only get the fruit to sell is a challenge,” he says.

And the farms aren’t likely to grow wheat, rice or other commodities that provide much of a daily diet, because there is less of a need for them to be fresh, Mr. Gordon-Smith says. They can be stored and shipped efficiently, he says.

The farms are also costly to start and run. AeroFarms has yet to turn a profit, though Mr. Rosenberg says he expects the company to become profitable in a few months, as its new farm helps it reach a new scale of production. Urban Produce became profitable earlier this year partly by focusing on specialty crops such as microgreens—the first shoots of greens that come up from the seeds—that enerally grow indoors in a very condensed space, says Mr. Horton, who started the company in 2014.

One of the first commercial vertical-farming companies in the U.S., FarmedHere LLC, closed a 90,000 square-foot farm in a Chicago suburb and merged with another company late last year. “We’ve learned a lot of lessons,” says co-founder Paul Hardej.

Among them: Operating in cities is expensive. The company should have built its first farm in a suburb rather than a Chicago neighborhood, Mr. Hardej says. Real estate would have been cheaper.

“We could have been 10 or 20 miles away and still be a local producer,” Mr. Hardej says.

The company also might have been able to work with a smaller local government to get permits and rework zoning and other regulations, because indoor farming was a new type of land use, Mr. Hardej says. While FarmedHere produced some crops profitably, it spent a lot on overhead for lawyers and accountants “to deal with the regulations,” he says.

Mr. Hardej is now co-founder and chief executive officer of Civic Farms LLC, a company that develops a “2.0” version of the vertical farm, he says—more efficient operations that take into account the lessons learned. Civic Farms is collaborating with the University of Arizona on a research and development center at Biosphere 2, the Earth science research facility in Oracle, Ariz., where it runs a vertical farm and develops new technologies.

Blossoming tech

New technology will improve the economic viability of vertical farms, says Mr. Gordon-Smith. New cameras, sensors and smartphone apps help monitor plant growth. One company is even developing augmented-reality glasses that can show workers which plants to pick, Mr. Gordon-Smith says.

“That is making the payback look a lot better,” he says. “The future is bright for vertical farming, but if you’re building a vertical farm today, be ready for a challenge.”

Some cities are trying to propagate more urban farms and ease the regulatory burden of setting them up. Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed created the post of urban agriculture director in December 2015, with a goal of putting local healthy food within a half-mile of 75% of the city’s residents by 2020. The job includes attracting urban-farming projects to Atlanta and helping projects obtain funding and permits, says Mario Cambardella, who holds the director title. “I want to be ahead of the curve; I don’t want to be behind,” he says.

Many groups are taking more low-tech or smaller-scale approaches. A program called BetterLife Growers Inc. in Atlanta plans to break ground this fall on a series of greenhouses in an underserved area of the city, where it will grow lettuce and herbs in 2,900 “tower gardens,” thick trunks that stand in large tubs. The plants will be propagated in rock wool, a growing medium consisting of cotton-candy-like fibers made of a melted combination of rock and sand, and then placed into pods in the columns, where they will be regularly watered with a nutrient solution pumped through the tower, says Ellen Macht, president of BetterLife Growers.

The produce will be sold to local educational and medical institutions. “What we wanted to do was create jobs and come up with a product that institutions could use,” she says.

The $12.5 million project is funded in part by a loan from the city of Atlanta, with Mr. Cambardella helping by educating grant managers on the growing system and its importance.

Change at home

Another company aims to bring vertical farming to the kitchen. Agrilution GmbH, based in Munich, Germany, plans to start selling a “plantCube” later this year that looks like a mini-refrigerator and grows greens using LED lights and an automatic watering system that can be controlled from a smartphone. “The idea is to really make it a commodity kitchen device,” says Max Loessl, Agrilution’s co-founder and chief executive officer, of the appliance, which will cost 2,000 euros—about $2,200—initially.

The goal is to sell enough to bring the price down, so that in five years the appliance is affordable enough for most people in the developed world, Mr. Loessl says.

Biofilta, the company Mr. Condon co-founded, is marketing the Foodwall, a modular system of connected containers, an approach that he calls “deliberately low tech” because it doesn’t require electricity or computers to operate. The tubs are filled with a soil-based mix and a “wicking garden-bed technology” that stores and sucks water up from the bottom of the tub to nourish the plants without the need for pumps. The plants need to be watered just once a week in summer, or every three to four weeks in the winter, says Chief Executive Marc Noyce. The tubs can be connected vertically or horizontally on rooftops, balconies or backyards. “We’ve made this gardening for dummies,” Mr. Noyce says.

The Foodwall can use composted food waste and harvested rainwater, helping to turn cities into “closed-loop food-production powerhouses,” Mr. Condon says.

He and Mr. Noyce were motivated to design the Foodwall by a projection from local experts that only 18% of the food consumed in their home city of Melbourne, Australia, will be grown locally by 2050, compared with 41% today, Mr. Noyce says.

“We were shocked,” says Mr. Noyce. “We’re going to be beholden to other states and other countries dictating our pricing for our own food.”

“Then we started to look at this trend around the world and found it was exactly the same,” he says.

Traditional, rural farming is far from being replaced by all of these new technologies, experts say. The need for food is simply too great. But urban projects can provide a steady supply of fresh produce, helping to improve diets and make a city’s food supply more secure, they say.

“While rural farmers will remain essential to feeding cities, cleverly designed urban farming can produce most of the vegetable requirements of a city,” Mr. Condon says.

The Future of Farming: Japan Goes Vertical And Moves Indoors

The Future of Farming: Japan Goes Vertical And Moves Indoors

Spread, Fujitsu and AeroFarms are growing vegetables hydroponically, with successful yields

BY MELINDA JOE

21 MAY 2017

Spread, Fujitsu and AeroFarms are growing vegetables hydroponically, with successful yields

Indoor agriculture is on the rise all over the world – particularly in Asia, where concerns over food safety and pesticide use in recent years have fuelled a boom in so-called plant factories. Spread, Japan’s largest vertical farm, produces more than 20,000 heads of lettuce a day in its 3000-square-metre facility outside of Kyoto.

Spread Co's vertical farms

The vegetables are cultivated hydroponically – without soil, in beds of constantly circulating nutrient solution – under LED lights in a sterile, climate-controlled environment. Later this year, the company plans to open a second facility that will use robot technology to automate tasks such as harvesting and boost total production to a whopping 50,000 heads per day.

Electronics giant Fujitsu is among a number of Japanese technology firms to embrace horticulture, converting factories that had formerly been used to manufacture semiconductors into tightly sealed indoor plantations manned by engineers in white cleanroom suits.

Fujitsu’s cloud-based software allows workers to easily monitor sensors that track the growth of the plants. Nutrient and light levels can be adjusted to develop varieties of lettuce with, for example, low potassium content for people with kidney disease.

AeroFarms

Last year, AeroFarms, located in New Jersey, made headlines for becoming the world’s biggest vertical farm, with the capacity to harvest roughly 1,000 tonnes of greens per year.

The company employs aeroponic technology, a more efficient form of hydroponics, where plants are grown in a mist environment. The company relies on big data to oversee the cultivation of 250 varieties of organically grown herbs and leafy vegetables.

Ikea’s Flatpack Vertical Garden Can Feed an Entire Neighborhood!

Ikea’s Flatpack Vertical Garden Can Feed an Entire Neighborhood!

February 27, 2017 by Admin Leave a Comment

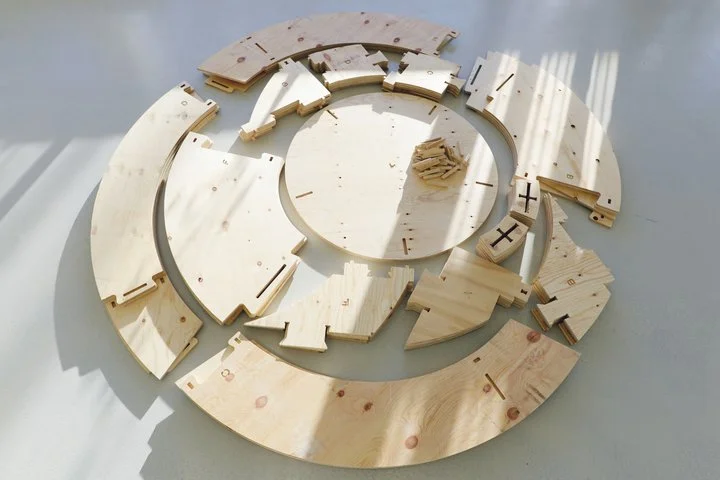

Ikea has come up with a flatpack garden so city dwellers with little space can enjoy a green patch all of their own. The Swedish furniture giant has launched the Growroom – a DIY 9ft tall sphere for nurturing plants, vegetables and herbs that you can actually sit in with your family and friends.

There’s a lot to appreciate about the Swedish company IKEA. From its numerous projects which have helped raise awareness about the Syrian peoples’ plight to its commitment to the environment by using mushroom-based packaging that decomposes within weeks, the furniture business is progressive, to say the least.

Now, IKEA has released open source plans for The Growroom, which is a large, multi-tiered spherical garden that was designed to sustainably grow enough food to feed a neighborhood. The plans were made free on Thursday with the hope that members of the public will invest their time and resources to create one in each neighborhood, if not in every person’s backyard.

The tools required to create the spherical garden include plywood, rubber hammers, metal screws, and diligence to follow the instructions comprised of 17 steps. The Huffington Post reports that The Growroom isn’t shipped in a flat pack like most IKEA products. Instead, users are required to download the files needed to cut the plywood pieces to size and are encouraged to visit a local workshop where the wood can be professionally cut. The free instructions online walk the builder through the remaining steps.

According to a press release, there are already plans to build Growrooms in Taipei, Rio de Janeiro, San Francisco, and Helsinki. You can add your city to the list by jumping on the opportunity and crafting a Growroom in your neighborhood.

The project is the brainchild of Space10, based in Denmark. The company writes:

“Local food represents a serious alternative to the global food model. It reduces food miles, our pressure on the environment, and educates our children of where food actually comes from. … The challenge is that traditional farming takes up a lot of space and space is a scarce resource in our urban environments.

The Growroom …is designed to support our everyday sense of well being in the cities by creating a small oasis or ‘pause’ architecture in our high paced societal scenery, and enables people to connect with nature as we smell and taste the abundance of herbs and plants. The pavilion, built as a sphere, can stand freely in any context and points in a direction of expanding contemporary and shared architecture.”

Following are some photos of the open source design:

What are your thoughts? Please comment below and share this news!

This article, by Amanda Froelich, (IKEA Just Released Free Plans For A Sustainable Garden That Can Feed A Neighborhood) is free and open source. You have permission to republish this article under a Creative Commons license with attribution to the author and TrueActivist.com. Photo credits: The Growroom.

Packaged Produce Sold At Some Giant Stores Recalled Due to Possibility of Metal In Product

Packaged Produce Sold At Some Giant Stores Recalled Due to Possibility of Metal In Product

- MEAGEN FINNERTY | Website Producer

- May 19, 2017

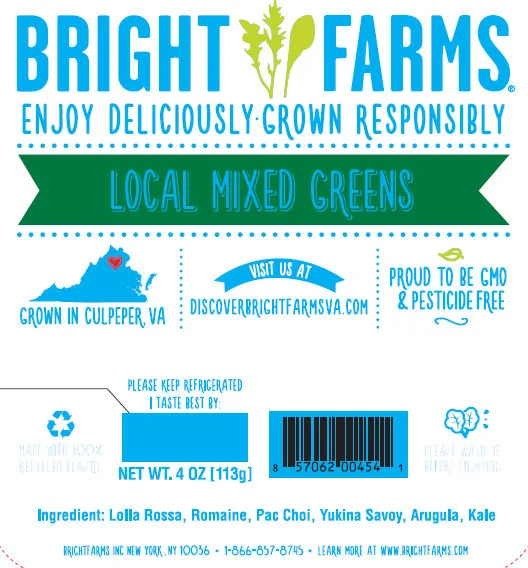

packaged produce company is recalling its products sold at some Giant stores and Martin's Food Markets.

BrightFarms, which sells spinach, spring mix, kale and other similar products issued the voluntary recall because of potential contamination of metal pieces in the produce.

The metal may have made its way into packaging during construction at the company's Elkwood, Virginia, greenhouse, according to the recall.

The salad products have best-by dates between May 22 and 26. They are:

- BrightFarms Baby Spinach (4 oz. package)

- BrightFarms Spring Mix (4 oz. and 8 oz. package)

- BrightFarms Spinach Blend (4 oz. package)

- BrightFarms Baby Kale (3 oz. package)

- BrightFarms Arugula (4 oz. and 8 oz. package)

- BrightFarms Mixed Greens (4 oz. package)

- BrightFarms Baby Romaine (4 oz. and 8 oz. package)

Affected basil products, best-by dates ranging from May 18 to 23, are:

- BrightFarms Basil (.75 oz. package)

- BrightFarms Thai Basil (.75 oz. package)

- BrightFarms Lemon Basil (.75 oz. package)

Products from other greenhouses aren't affected by the recall. Consumers are encouraged to throw away products or return their purchases for a refund.

Affected stores are: Giant Landover, Giant Carlisle, Peapod and Martin’s Food Markets in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, West Virginia and Washington, D.C., and possibly Capital Area Food Bank.

An Inside View of Hong Kong’s Hidden Rooftop Farms

An Inside View of Hong Kong’s Hidden Rooftop Farms

Born out of a fear of contaminated foods, the city’s budding interest in high-altitude gardening may help heal an increasingly fractured – and ageing – society.

- By David Robson

17 May 2017

A butterfly perching on a lettuce leaf is not normally a cause for marvel. But I am standing on the roof the Bank of America Tower, a 39-floor building in the heart of Hong Kong’s busiest district, to see one of its highest farms. The butterfly must have flown across miles of tower blocks to reach this small oasis amidst the concrete desert.

“You just plant it out and nature comes and enjoys it,” says Andrew Tsui. We are joined by Michelle Hong and Pol Fabrega, who together lead Rooftop Republic, a social enterprise that aims to turn the city’s dizzying skyline green.

If it weren’t for the fact that we are 146 metres (482ft) above street-level, this farm would look like any allotment site or garden courtyard – row after row of rectangular crates, some with fresh sprouts poking through the surface, others with established plants almost ready for harvest. The loudest noise I can hear is not the traffic below, but the wind.

Although it is only February when I visit, the sun is so strong I end the morning with a slight tan, and Hong tells me that the local climate offers ideal growing conditions for most of the year, meaning that despite the exposure, they can cultivate a range of plants. “We have things like cherry tomatoes, salad, broccoli – all of that can be grown here,” explains Hong. The greens I see today are as lush as anything you would find growing at sea level. Workers from the offices below tend it day-to-day, and after harvest, the fruits of their labour are sent to a food bank, where they fill lunchboxes for the needy. “We want to share the good products – not just the leftovers,” says Tsui. On other projects, however, the farmers would take the produce for themselves.

Truly fresh, locally grown vegetables are something of a luxury in Hong Kong. To demonstrate why, Tsui points from our rooftop to the rings of mountains that encompass the city. In between are the two bands of dense urban development, straddling the harbour. “Five to six million people are squeezed in these two narrow belts,” he says

Thanks to these crammed conditions, the city imports more than 90% of its food – much of it from mainland China. But after some well-publicised cases of food contamination in China, more and more people are now looking for locally grown goods. And if they can’t grow it on the ground, they have to take it to the sky.

The team try to invite the remaining rural farmers from surrounding regions, to come and give classes to the city workers

Food production is only one of the project’s aims, however. Their greater goal is to revolutionise the city’s fast-paced culture. Like most urban areas, Hong Kong’s society is highly stratified, and its citizens are often isolated to their particular niche, formed of their colleagues and close friends. The Rooftop Republic team hope that the farms can help break through those barriers. “It’s a bit of a social experiment,” says Tsui.

The team try to invite remaining rural farmers from surrounding regions, to come and give classes to the city workers, for instance. “We hope that this rich knowledge of organic farming practice isn’t lost with their generation, so they can pass it on and share it with the community.”

In return, they pay the rural farmers to cultivate seedlings to be planted on the rooftop farms, providing them with a steady source of income that is not subject to the whims of the market. “This part of their income is lower risk and they can pre-empt and manage their time,” says Tsui. It’s a small step, perhaps – but one that helps connect two populations who would never normally interact. The team also work with the hard-of-hearing and people with other disabilities, who can find the contact with nature to be therapeutic.

Thirty-nine stories high, the rooftop farm on the Bank of America Tower adds some much needed greenery to the concrete jungle (Credit: Robert Davies)

After we descend from the Bank of America Tower, the team take me to a second project on the Hong Kong Fringe Club – which grows aubergines, tomatoes, oregano, lemongrass, mint and kale for the bar and restaurant below. I will have passed the building a dozen times on my trip so far without realising that it hosted this little haven on its roof.

Here the team tell me about their other goal: education. By running regular workshops, the team hope that Hong Kong’s city-dwellers will become a little more aware of the resources needed to grow the food they are eating. Pointing to a bed of broccoli, for instance, Hong remembers one recent group who had never seen the whole plant. “They didn’t realise that the florets that we eat are actually quite limited,” she says. “And if you look at the quantity we see in the supermarket, you begin to see how much space we would need to grow that,” she says.

We do have a mission, in a way – to make farming cool – Andrew Tsui

Fabrega agrees. He says that when the team give family workshops on farming, the parents often end up learning as much as the kids. “We’re teaching them, even though it’s at a basic level.” By seeing the origins and ecological consequences of their foods, they might just choose to be a little bit less wasteful with their groceries – encouraging greater overall sustainability.

Ultimately, Tsui’s dream is that a restful break on a rooftop farm will become ingrained in everyone’s daily routine. “I use the analogy of coffee,” says Tsui – something that was once a luxury, but which became a lifestyle, through sheer convenience. If he had his way, a trip to the farm would be as essential as a morning caffeine fix. “We do have a mission, in a way – to make farming cool.”

The rooftop farm at the Hong Kong Fringe Club provides ingredients for the bar and restaurant below (Credit: Robert Davies)

To better understand the broader potential for rooftop farming, I later met up with Matthew Pryor at the Division of Landscape Architecture of the University of Hong Kong (HKU). Originally from the UK, Pryor moved to Hong 25 years ago. “The pace of it, the intensity become addictive – you don’t love it but you can’t do without it.”

I catch Pryor when he is hard at work on his current project, as he attempts to model the city to estimate the total space that could be devoted to rooftop farms. His first estimates are surprisingly vast – 695 hectares in total, nearly five times the size of London’s Hyde Park or twice the size of New York’s Central Park. “Now the total ground level farmable land in Hong Kong was about 420 hectares,” he says. “So there’s more on the roof than there is on the ground.”

They are spending a huge amount of time on the street. Couldn’t they be spending that time on the roof?

As part of this work, Pryor has conducted a series of surveys of the rooftop farms in Hong Kong – finding around 60 in progress so far. “What attracts me to this is that they are completely unconnected, spontaneous – 60 groups who have had the same idea, at the same time, and they’ve gone out there and done it.”

Like Tsui, he sees the rooftop farms as an efficient form of social welfare – particularly for the elderly. “Life expectancy in Hong Kong is now at 90 – we outlive the rest of the world,” he says. “But there’s nowhere for the elderly to go. They are spending a huge amount of time on the street – particularly the low-income elderly. Couldn’t they be spending that time on the roof?” Light exercise and regular social contact, are, after all, two of the best ways to stave off dementia.

As a bonus, he says, the rooftop farms can also provide thermal insulation and sound insulation – saving the building’s overall energy consumption through air conditioning. “I’d like to persuade the government to recognise rooftop farms as a legitimate use,” he says – so they could be integrated into the city planning.

Hong Kong's climate makes it ideal for growing vegetables all year round (Credit: Robert Davies)

After chatting in his office, we potter around HKU’s own rooftop farm, which Pryor helped found with students and other staff members. He recalls that when he first got permission to build the farm, he had to lug tonnes of soil and compost up the final flight of stairs – while remaining silent for an exam in progress. Everything I see up here is recycled or reclaimed from construction sites, and they even have a wormery to produce their own compost. He has made sure that that each pot is anchored by the weight of its own soil – a crucial measure come typhoon season. So far, there have been no disasters during the heavy storms.

The biggest challenge is protecting the crops from sulphur-crested cockatoos

Recently, his biggest challenge is protecting the crops from sulphur-crested cockatoos. “They are a real pest – really noisy, aggressive animals.” When I visit this February afternoon, however, the university farm is astonishingly peaceful, with an extraordinary view into the mountains ringing the city. “Most people come in the late afternoon and watch the sunset,” he says.

Could this be a glimpse of the future for city-dwellers everywhere? “Hong Kong offers a kind of laboratory,” Pryor says. “When we’re teaching, we say ‘Don’t take Hong Kong as the norm, take it as the extreme.’” If the rooftop farms can catch on here – and become as popular as coffee – it seems only a matter of time before they become a regular fixture across the world.

David Robson is BBC Future’s feature writer. He is @d_a_robson on Twitter.

Join 800,000+ Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

$3.5M Indoor Farming Facility Could Break Ground In June

$3.5M Indoor Farming Facility Could Break Ground In June

By Mark Peterson | Posted: Tue 5:58 PM, May 16, 2017 | Updated: Tue 6:41 PM, May 16, 2017

The construction of an indoor farming operation in inner-city South Bend could begin next month.

City officials expressed a willingness Tuesday to buy into the proposed $3.5 million dollar project—but not sight unseen.

“We’d like to at least get a visual on what those look like before we put our dollars and investment. We hope it will enhance the neighborhood. We don’t want it to be a detriment to the neighborhood,” said Jeff Rea, Chairman of the South Bend Industrial Revolving Loan Fund Board.

While there are plenty of pictures that show what the inside of a vertical farming operation in South Bend would look like, there’s not a single depiction of what it would look like on the outside.

“So, from what we’ve been told is that the building would be more like a tent structure, not, made out of fabric, not a solid,” said Tim Corcoran with South Bend’s Community Investment Department. “I don’t know of any other fabric buildings in our community.”

The proposed indoor growing facility would stand a story and a half tall and be window-less. “So it's a temporary facility if you will, it's a tent-like facility, so tent conjures up a different images for a lot of different people,” said Jeff Rea.

It was the impact on the overall image of the neighborhood off Sample Street, north of the Ivy Tech campus that had some worried. Every neighboring building near the vacant lot where the farm would be built is made of brick.

Members of South Bend’s Industrial Revolving Loan Fund Board today tentatively approved a $700,000 loan for the project. Final approval will come only if the ‘ayes’ still have it—after pictures of the proposed facility are provided and perused.

“Ultimately we're in support of the loans, we approved the loan today contingent on the visual, us approving the visual piece of that too, so we're going to ask the owner to give us some pictures and help us understand what this operation is going to look like,” said Jeff Rea.

After getting a peek at the pictures, members of the loan board plan to hook up by conference call to consider giving final approval. Officials say the developer, Green Sense Farms, wants to break ground on the South Bend project in June.

The vertical farming facility would be a place where green leafy vegetables would be grown year-round, under artificial light, and carefully controlled conditions. The facility would also be a place where Ivy Tech students could earn a degree.

“Food sustainability is an important issue that is just going to continue to become more important as arable farmland is reduced in Indiana and around the world for that matter. So from the use perspective, I find it a very interesting thing and I’m glad that they’re trying to trial this in South Bend,” said Corcoran.

From Moscow: A ‘City Farm’ Home Appliance

From Moscow: A ‘City Farm’ Home Appliance

The body is completely leak-tight, made of sound eight-layered composite aluminum. You can select out of 9 coloring options.

Regulated «smart» tinting coating of a farm’s glass door enables to turn down the glaring light RainbowSpectrum ™. Tinting coating is controlled with the use of the INTELLIGENT EXPERT application.

Module body is made of Softtouch plastic due to which it is highly wear-resistance and possesses elegant appearance.

Innovative module structure with in-built drip watering system enables to

control the level of the nutrients and minerals supply to the plants as well as enables to easily change the glasses for growing.

Rainbow Spectrum ensures efficient process of plant photosynthesis at the expense of using solely the blue and red spectrum colors. Innovative light-emitting diode unit is automatically adjusted to the croppings grown in the city farm creating the most favorable conditions for their growth and fruiting.

Automatic climate control system ensures favorable air temperature and humidity for the croppings development inside a city farm. Measurements by all parameters are displayed in the INTELLIGENTEXPERT application.

A Farm Grows In The City

Startups are leading the way to a future in which more food is grown closer to where people live

At AeroFarms’ indoor vertical farm in Newark, N.J., greens grow on shelves 36 feet high Bryan Anselm for The Wall Street Journal

A Farm Grows In The City

Startups are leading the way to a future in which more food is grown closer to where people live

By: Betsy McKay | Photographs by: Bryan Anselm for The Wall Street Journal

May 14, 2017 10:05 p.m. ET

Billions of people around the world live far from where their food is grown.

It’s a big disconnect in modern life. And it may be about to change.

The world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, 33% more people than are on the planet today, according to projections from the United Nations. About two-thirds of them are expected to live in cities, continuing a migration that has been under way around the world for years.

That’s a lot of mouths to feed, particularly in urban areas. Getting food to people who live far from farms—sometimes hundreds or thousands of miles away—is costly and strains natural resources. And heavy rains, droughts and other extreme weather events can threaten supplies

Now more startups and city authorities are finding ways to grow food closer to home. High-tech “vertical farms” are sprouting inside warehouses and shipping containers, where lettuce and other greens grow without soil, stacked in horizontal or vertical rows and fed by water and LED lights, which can be customized to control the size, texture or other characteristic of a plant.

Companies are also engineering new ways to grow vegetables in smaller spaces, such as walls, rooftops, balconies, abandoned lots—and kitchens. They’re out to take advantage of a city’s resources, composting food waste and capturing rainwater as it runs off buildings or parking lots.

“We’re currently seeing the biggest movement of humans in the history of the planet, with rural people moving into cities across the world,” says Brendan Condon, co-founder and director of Biofilta Ltd., an Australian environmental-engineering company marketing a “closed-loop” gardening system that aims to use compost and rainwater runoff. “We’ve got rooftops, car parks, walls, balconies. If we can turn these city spaces into farms, then we’re reducing food miles down to food meters.”

Moving beyond experiments

Plants at AeroFarms receive light of a specific spectrum

Urban farming isn’t easy. It can require significant investment, and there are bureaucratic hurdles to overcome. Many companies have yet to turn a profit, experts say. A few companies have already failed, and urban-farming experts say many more will be weeded out in the coming years.

But commercial vertical farms are well beyond experimental. Companies such as AeroFarms, owned by Dream Holdings Inc., and Urban Produce LLC have designed and operate commercial vertical farms that aim to deliver supplies of greens on a mass scale more cheaply and reliably to cities, by growing food locally indoors year round.

At its headquarters in Irvine, Calif., Urban Produce grows baby kale, wheatgrass and other organic greens in neat rows on shelves stacked 25 high that rotate constantly, as if on a conveyor belt, around the floor of a windowless warehouse. Computer programs determine how much water and LED light the plants receive. Sixteen acres of food grow on a floor measuring an eighth of an acre.

Its “high-density vertical growing system,” which Urban Produce patented, can lower fuel and shipping costs for produce, uses 80% less fertilizer than conventional growing methods, and generates its own filtered water for its produce from humidity in the air, says Edwin Horton Jr., the company’s president and chief executive officer.

“Our ultimate goal is to be completely off the grid,” Mr. Horton says.

The company sells the greens to grocers, juice makers and food-service companies, and is in talks to license the growing system to groups in cities around the world, he says. “We want to build these in cities, and we want to employ local people,” he says.

An AeroFarms employee inspects a tray of greens.

AeroFarms has built a 70,000-square-foot vertical farm in a former steel plant in Newark, N.J., where it is growing leafy greens like arugula and kale aeroponically—a technique in which plant roots are suspended in the air and nourished by a nutrient mist and oxygen—in trays stacked 36 feet high.

The company, which supplies stores from Delaware to Connecticut, has more than $50 million in investment from Prudential, Goldman Sachs and other investors, and aims to install its systems in other cities globally, says David Rosenberg, its chief executive officer. “We envision a farm in cities all over the world,” he says.

AeroFarms says it is offering project management and other services to urban organizations as a partner in the 100 Resilient Cities network of cities that are working on preparing themselves better for 21st century challenges such as food and water shortages.

The bottom line

Still, these farms can’t supply a city’s entire food demand. So far, vertical farms grow mostly leafy greens, because the crops can be turned over quickly, generating cash flow easily in a business that requires extensive capital investment, says Henry Gordon-Smith, managing director of Blue Planet Consulting Services LLC, a Brooklyn, N.Y., company that specializes in the design, implementation and operation of urban agricultural projects globally.

AeroFarms packaged greens await shipment.

The greens can also be marketed as locally grown to consumers who are seeking fresh produce.

Other types of vegetables require more space. Growing fruits like avocados under LED light might not make sense economically, says Mr. Gordon-Smith.

“Light costs money, so growing an avocado under LED lights to only get the fruit to sell is a challenge,” he says.

And the farms aren’t likely to grow wheat, rice or other commodities that provide much of a daily diet, because there is less of a need for them to be fresh, Mr. Gordon-Smith says. They can be stored and shipped efficiently, he says.

The farms are also costly to start and run. AeroFarms has yet to turn a profit, though Mr. Rosenberg says he expects the company to become profitable in a few months, as its new farm helps it reach a new scale of production. Urban Produce became profitable earlier this year partly by focusing on specialty crops such as microgreens—the first shoots of greens that come up from the seeds—that enerally grow indoors in a very condensed space, says Mr. Horton, who started the company in 2014.

One of the first commercial vertical-farming companies in the U.S., FarmedHere LLC, closed a 90,000 square-foot farm in a Chicago suburb and merged with another company late last year. “We’ve learned a lot of lessons,” says co-founder Paul Hardej.

Among them: Operating in cities is expensive. The company should have built its first farm in a suburb rather than a Chicago neighborhood, Mr. Hardej says. Real estate would have been cheaper.

“We could have been 10 or 20 miles away and still be a local producer,” Mr. Hardej says.

The company also might have been able to work with a smaller local government to get permits and rework zoning and other regulations, because indoor farming was a new type of land use, Mr. Hardej says. While FarmedHere produced some crops profitably, it spent a lot on overhead for lawyers and accountants “to deal with the regulations,” he says.

Mr. Hardej is now co-founder and chief executive officer of Civic Farms LLC, a company that develops a “2.0” version of the vertical farm, he says—more efficient operations that take into account the lessons learned. Civic Farms is collaborating with the University of Arizona on a research and development center at Biosphere 2, the Earth science research facility in Oracle, Ariz., where it runs a vertical farm and develops new technologies.

Blossoming tech

New technology will improve the economic viability of vertical farms, says Mr. Gordon-Smith. New cameras, sensors and smartphone apps help monitor plant growth. One company is even developing augmented-reality glasses that can show workers which plants to pick, Mr. Gordon-Smith says.

“That is making the payback look a lot better,” he says. “The future is bright for vertical farming, but if you’re building a vertical farm today, be ready for a challenge.”

Some cities are trying to propagate more urban farms and ease the regulatory burden of setting them up. Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed created the post of urban agriculture director in December 2015, with a goal of putting local healthy food within a half-mile of 75% of the city’s residents by 2020. The job includes attracting urban-farming projects to Atlanta and helping projects obtain funding and permits, says Mario Cambardella, who holds the director title.

“I want to be ahead of the curve; I don’t want to be behind,” he says.

Many groups are taking more low-tech or smaller-scale approaches. A program called BetterLife Growers Inc. in Atlanta plans to break ground this fall on a series of greenhouses in an underserved area of the city, where it will grow lettuce and herbs in 2,900 “tower gardens,” thick trunks that stand in large tubs. The plants will be propagated in rock wool, a growing medium consisting of cotton-candy-like fibers made of a melted combination of rock and sand, and then placed into pods in the columns, where they will be regularly watered with a nutrient solution pumped through the tower, says Ellen Macht, president of BetterLife Growers.

BetterLife Growers will use ‘tower gardens’ like these to grow lettuce and herbs in Atlanta. Photo: Scissortail Farms

The produce will be sold to local educational and medical institutions. “What we wanted to do was create jobs and come up with a product that institutions could use,” she says.

The $12.5 million project is funded in part by a loan from the city of Atlanta, with Mr. Cambardella helping by educating grant managers on the growing system and its importance.

Change at home

Another company aims to bring vertical farming to the kitchen. Agrilution GmbH, based in Munich, Germany, plans to start selling a “plantCube” later this year that looks like a mini-refrigerator and grows greens using LED lights and an automatic watering system that can be controlled from a smartphone. “The idea is to really make it a commodity kitchen device,” says Max Loessl, Agrilution’s co-founder and chief executive officer, of the appliance, which will cost 2,000 euros—about $2,200—initially.

The goal is to sell enough to bring the price down, so that in five years the appliance is affordable enough for most people in the developed world, Mr. Loessl says.

Biofilta’s Foodwall system of connected containers requires minimal watering. Photo: Ben Mulligan

Biofilta, the company Mr. Condon co-founded, is marketing the Foodwall, a modular system of connected containers, an approach that he calls “deliberately low tech” because it doesn’t require electricity or computers to operate. The tubs are filled with a soil-based mix and a “wicking garden-bed technology” that stores and sucks water up from the bottom of the tub to nourish the plants without the need for pumps. The plants need to be watered just once a week in summer, or every three to four weeks in the winter, says Chief Executive Marc Noyce. The tubs can be connected vertically or horizontally on rooftops, balconies or backyards. “We’ve made this gardening for dummies,” Mr. Noyce says.

The Foodwall can use composted food waste and harvested rainwater, helping to turn cities into “closed-loop food-production powerhouses,” Mr. Condon says.

He and Mr. Noyce were motivated to design the Foodwall by a projection from local experts that only 18% of the food consumed in their home city of Melbourne, Australia, will be grown locally by 2050, compared with 41% today, Mr. Noyce says.

“We were shocked,” says Mr. Noyce. “We’re going to be beholden to other states and other countries dictating our pricing for our own food.”

“Then we started to look at this trend around the world and found it was exactly the same,” he says.

Traditional, rural farming is far from being replaced by all of these new technologies, experts say. The need for food is simply too great. But urban projects can provide a steady supply of fresh produce, helping to improve diets and make a city’s food supply more secure, they say.

“While rural farmers will remain essential to feeding cities, cleverly designed urban farming can produce most of the vegetable requirements of a city,” Mr. Condon says.

Ms. McKay is a senior writer in The Wall Street Journal’s Atlanta bureau. She can be reached at betsy.mckay@wsj.com.

Appeared in the May. 15, 2017, print edition.

Camden Will House The World's Largest Indoor Farm, Thanks To State Tax Breaks

Camden Will House The World's Largest Indoor Farm, Thanks To State Tax Breaks

Updated on May 16, 2017 at 9:26 AM Posted on May 16, 2017 at 7:45 AM

For NJ.com

CAMDEN -- The world's largest indoor farm is expected to open its doors in Camden next year, thanks to a tax break from the state.

Aerofarms LLC, a Newark-headquartered company that builds sustainable, efficient farms around the globe, plans to open its 10th facility, a 78,000-square-foot vertical farm, at 1535 Broadway in Camden.

The addition comes after the state Economic Development Authority announced Thursday that Aerofarms will receive $11.14 million in tax incentives over 10 years to build the farm in Camden. The facility is expected to create 56 new jobs in the area, according to documents from the agency.

That makes Aerofarms just one of several companies, including Subaru and Holtec, that have received incentives to relocate to the city as authorities look for ways to revitalize the area.

"We probably would not have made the move to Camden -- at least not now -- without the [Grow New Jersey] tax grant," David Rosenberg, the company's founder and CEO, told Philly.com.

Aerofarm's vertical spaces and aeroponics growing technologies allow them to grow produce efficiently, using up to 95 percent less water than traditional agriculture methods while still seeing yields that are 130 times higher per square foot each year, according to the company's site. The hydroponic method uses a mist to provide plants with nutrients and water they need to grow in the smaller urban spaces.

$30M 'vertical farm' to bring jobs to Newark, fresh greens to N.J., developers say

But starting and maintaining the spaces often proves pricey. Aerofarms has yet to make a profit, and relies on investors, including Goldman Sachs and Prudential, to continue its operations. Rosenberg told The Wall Street Journal that he believes the Newark farm, which boasts 70,000 square feet of growing space, will help the company turn that corner in coming months.

The farms, which supply produce to stores from Delaware to Connecticut, will become increasingly important as urban areas become more dense and the population continues to grow, urban farming advocates say. Rosenberg told The Wall Street Journal he hopes to see the farms in cities around the world as the company expands.

But for now, New Jersey officials are glad to see the future of farming take off across the state.

"By 2050 there will be 9 billion people who need to eat every day," Lieutenant Governor Kim Guadagno said during the 2015 groundbreaking of the Newark farm. "And the solution is right here on the property you're standing on."

Amanda Hoover can be reached at ahoover@njadvancemedia.com. Follow her on Twitter @amahoover. Find NJ.com on Facebook.

The Citadel's Container Farm Is First Of Its Kind For Military College

The Citadel's Container Farm Is First Of Its Kind For Military College

Friday, April 28th 2017, 10:59 pm CDTFriday, April 28th 2017, 10:59 pm CDTBy Alexis Simmons, Reporter/MMJ

CHARLESTON, SC (WCSC) -

The Citadel's first harvest was ready from its container farm on Friday.

It's the college's Sustainability Project, part of The Zucker Family School of Education’s STEM Center of Excellence.

Tiger Corner Farms Manufacturing a company based in Summerville provided the container farm.

It uses the process of Aeroponics, growing plants in an air or mist environment without the use of soil and you control the environment.

The Citadel Cadets harvested five different types of lettuce.

It was Citadel grad and U.S. Marine 2nd Lt. Benjamin Cohen's idea to bring it to campus. He's also the Sustainability Project Founder.

"It is amazing, absolutely amazing to see what the cadets have done," Cohen said. "This entire project was envisioned for them, the idea being that we would build a farm on campus that is planned built managed developed expanded by cadets and that was really the selling point."

The 40 ft. container produced enough lettuce to cover about 2 acres of land. It totals up to several thousand heads, each that can be continually harvested

Another perk, it's organic and you don't have to worry about pesticides because it's enclosed.

Stage one of the process involves putting the seeds in trays. After they are watered they are moved to vertical panels where the lettuce will grow for four to six weeks. The plants are watered through state of the art technology and artificial lighting helps them grow.

The cadets can also track the system on a computer to make sure everything is running correctly.

Junior Cadet, Alex Richardson is the President of the Sustainability Project.

"You don't have to be a farmer to do something like this, I have no farming experience, I'm just an engineering student," Richardson said.

Matthew Miller is a sophomore cadet who's involved with the project as well.

"It's the community idea, this is something that as long as you have the right essentials you could put this in Antarctica, in Egypt, in Charleston, South Carolina," Miller said "That's really the goal you want to provide for people that can't do that themselves."

Several restaurants near campus have agreed to use the lettuce.

The lettuce will also be used in the college's dining hall to feed the campus on a regular basis.

The cadets built the inside components of the container farm and planted the lettuce.

The harvest party is intended to help raise the funds for a second container for next year for the campus.

Copyright 2017 WCSC. All rights reserved.

Riding The Agriculture & Food Wave – Indoor Vertical Farming

Riding The Agriculture & Food Wave – Indoor Vertical Farming

Posted on May 11, 2017 by Leo Zhang

Following our recent blog post on alternative proteins, let’s take another look at the agriculture & food sector and touch on a related topic of sustainable food production – indoor vertical farming. Although vertical farming has yet to attract similar level of investments compared to alternative proteins, this space is certainly worth keeping track of as we expect more mega-cities to form over the next decade, and subsequently, the demand for a more sustainable food production system.

Below is a quick overview of what we are seeing in terms of innovators and investors, and for a close look at this space, please do get in touch with us at research@cleantech.com.

Hydroponics, Aquapoincs, and Aeroponics

There are three main types of vertical farming systems – hydroponics, aquapoincs, and aeropoincs. The hydroponic system grows plants without soil using mineral solutions in water, and it is the predominant system currently used in vertical farms. The aquaponic system combines a plant hydroponic system with indoor fish ponds. Finally, the aeroponic system grows plants without soil, and uses an air or mist solution to deliver nutrients. Examples of innovators include:

Who’s Interested?

We have seen the rise in the overall agriculture & food investment amount starting in 2014. Among this wave of investments, agricultural software, plant genomics, and even drones & robotics make up a large percentage of the total investment. Nevertheless, we have tracked a number of venture deals in the vertical farming subsector, particularly by early-stage investors.

For example, Bowery, a New York-based indoor produce grower, raised $7.5M in seed funding in April 2017. Participating early-stage investors include First Round Capital, SV Angel, Lerer Hippeau Ventures, in addition to a number of private angel investors.

Another notable example to highlight is Plenty, a California-based developer of vertical farms that incorporates AI, data analytics and IoT sensors, which raised an astonishing $26M in Series A funding earlier this year. Two noteworthy investors to highlight here – Bezos Expeditions (Amazon’s Jeff Bezos) and Innovation Endeavors (Google’s Eric Schmidt) – signify the growing importance of sustainable food production.

What’s Next?

As most vertical farm companies are still operating at a very small scale, it is expected that most of the funding has come from angel and seed investors. However, will the next wave of investments in this space come from corporate investors? Will vertical farming be able to scale up to massive food production systems?

We will certainly be keeping our eyes on this space. Let us know your thoughts via research@cleantech.com

This Company Is Bringing Gardening Into The 21st Century

This Company Is Bringing Gardening Into The 21st Century

Seedsheet, a Vermont-based agri-tech company, just made it to the eighth season of Shark Tank. The business accepted a US$500,000 offer from Shark Tank cast member Lori Greiner.