Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

The Farms Of The Future Are Here – But There's A Catch

This new type of farming, dubbed "urban farming," requires significantly less acreage and energy. Simply put, urban farms grow or produce food in a city or heavily populated area using unorthodox methods.

The Farms Of The Future Are Here – But There's A Catch

By CASEY WILSON, Associate Editor, Money Morning • September 21, 2017

The farms of the future use absolutely no soil and 95% less water.

Yes, you read that right. No soil – at all.

This new type of farming, dubbed "urban farming," requires significantly less acreage and energy. Simply put, urban farms grow or produce food in a city or heavily populated area using unorthodox methods.

Urban farming takes many forms, using many different methods. Some urban farms are strictly vertical farms, which means the plants grow upright on walls. Some are aeroponic, which means the plants grow in an air or mist environment.

Urban farms are so efficient, just half an acre can yield the same (and in some cases, more) harvest than over 10 acres of traditional farmland.

No wonder these urban farms are sprouting up all over the country. There's at least one urban farm in almost every major city today. In some cities, like New York City, there are more than 20.

But here's the downside…

Urban farming isn't something average investors and traders can directly invest in, and likely won't be for a while.

You see, most urban farming ventures get their funding from venture capitalists. For example, AeroFarms Corp., one of the largest urban vertical farming companies, just secured $20 million for its latest indoor farm all from one round of venture funding.

And the company has not made any plans to go public as of yet. Instead, the company is planning to work with Goldman Sachs Group Inc. (NYSE: GS) and Prudential Financial Inc. (NYSE: PRU) to raise more than $70 million over the next five years in order to build 25 new farms – a 177% increase from the 14 farms it has now.

Still, there's a way for investors to profit from this burgeoning technology. Check out the video below…

Bosses Of Google And Amazon Back Plenty In plan To Bring High-Tech Farm Warehouses To Feed Britain

Bosses Of Google And Amazon Back Plenty In plan To Bring High-Tech Farm Warehouses To Feed Britain

Danny Fortson, San Francisco

September 24 2017, 12:01am, The Sunday Times

Plenty plans to open farm warehouses globally, in the cities that are home to at least 1m peopleALAMY

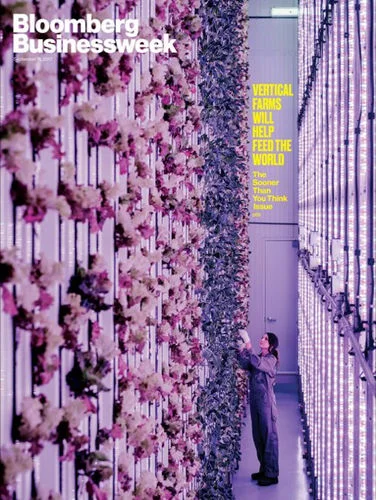

An indoor-farming start-up backed by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Eric Schmidt, chairman of Google parent Alphabet, plans to bring its high-tech farm warehouses to Britain by 2019.

Plenty raised $200m ($148m) in a funding round led by SoftBank Vision Fund, the $100bn mega-fund created by Saudi Arabia and Japan’s SoftBank. Bezos and Schmidt, who invested in a previous financing, also contributed.

The San Francisco company is in the midst of bringing in more investors to bankroll an aggressive global rollout. Chief executive Matt Barnard wants to open “farms” in the 500 cities around the world with at least 1m people, with that expansion arriving in Britain as soon as 2019.

Plenty’s giant warehouses — where plants are grown in 20ft towers with lighting, temperature, water and pests controlled and managed with artificial intelligence — promise to dramatically improve efficiency and output compared with normal farms.

Barnard claimed lettuce can be grown with less than 1% of the water required in a traditional operation. High energy costs are offset by locating warehouses in or near city centres, doing away with the need for long-haul transport that accounts for up to 40% of the price for fruit and veg.

He said: “What’s going to be stunning for people is the speed at which much of what they eat will be grown.”

Danny in the Valley podcast: Plenty’s Matt Barnard: “You’re eating year-old apples”

Modern Farmers: Modern Farmers: The Future of Farming Is Sprouting Up Where You'd Least Expect It

It's not just a potential antidote to the unsustainable machine of industrial agriculture. It's also a new frontier for the culinary world, and you're about to reap the benefits.

Go Inside the Farms | Photo: Bowery

Beneath one of NYC's best restaurants, down a hallway you could find only if you knew where to go, rows of heady, hydroponic herbs, sticky with residue, grow under LED lights. Across the East River, in an old factory, a small lab of growers tinker with their own seedlings, while a greenhouse just two miles away grows its own special line of potent plants.

No, we're not talking about weed—although in many ways, the, ahem, budding industry helped pave the way here. We're describing the field of indoor farming, much of it hydroponic, catering to home cooks and restaurant chefs, that's growing at an incredible clip around the country. And it's booming where you'd least expect it: none other than New York City.

It's not just a potential antidote to the unsustainable machine of industrial agriculture. It's also a new frontier for the culinary world, and you're about to reap the benefits.

Just ask Tom Colicchio, an investor in Bowery Farming, a seven-month-old hydroponic vertical farm, which just recently started selling greens to tristate area Whole Foods. The chef calls the company the "new paradigm for farming," one that he's "really excited about." At his new Downtown NYC restaurant, Temple Court (previously Fowler & Wells), the Top Chef judge garnishes crudo with Bowery's wasabi arugula—a spicy green bursting with flavor. Or ask Claus Meyer, an adviser at Brooklyn Navy Yard-based start-up Farmshelf, or Alex Guarnaschelli, who sources from newcomer Farm.One, which has spaces at the Institute of Culinary Education and underneath the restaurant Atera in Tribeca. Each one of these chefs is a champion for the undeniable advantage of indoor farming: fresh, unique and local produce available all year round.

Andrew Whitcomb, executive chef at Norman | Photo: Farmshelf

Exact methods vary, but generally speaking, hydroponic farms grow greens, herbs and flowers in soilless containers under LED lights in highly controlled climates. That means 365 days of ideal growing conditions, with efficient water use and minimal waste. They're also often stacked vertically, which cuts down on the need for square footage. Some farms, like Edenworks in Brooklyn, use fish and aquatic life to feed their ecosystems, while others, like AeroFarms, don't use hydroponics at all but rely on a specifically crafted aeroponic mist.

It might sound unnatural, but these farms are actually growing their goods without the use of herbicides or pesticides. Bowery cofounder Irving Fain implores skeptics to rethink what organic really means, pointing out that "organic standards were written at a time when a lot of the technology we have access to today didn't even exist."

And then there's the magic word: local. These indoor farms are able to grow and sell within mere miles of the restaurants or homes to which they're catering, no matter the season.

As Great Northern Food Hall's Jonas Boelt—who works with Farmshelf—explains, "Back in Denmark, my team and I would go forage for ingredients daily. As that is impossible in New York City, harvesting Farmshelf herbs is the next best thing."

When you look at it this way, it makes sense that NYC and the surrounding area, against all odds, has become a major hub for ag tech. The high demand from the most competitive dining scene in the country, coupled with the short growing season, actually makes for quite fertile ground. Add to that the great public transportation, Farm.One CEO Robert Laing points out, and distribution becomes even more sustainable.

Though the space may seem crowded, every company has a distinct mission. AeroFarms and Edenworks focus on large-scale production, boxing greens to sell at the supermarket. Bowery does the same but also works with Colicchio to expand its culinary partnerships.

Farmshelf builds units to put into restaurants—like the Great Northern Food Hall and Brooklyn's Norman—hotels, corporate cafeterias and eventually home kitchens, "putting the technology into the hands of the consumer and bringing the farm right into the building," as cofounder/CRO Jean-Paul Kyrillos says.

Unique greens growing at Farm.One in TriBeCa | Photo: Farm.One

Then there's Farm.One, which focuses on providing restaurants with rare and fresh ingredients, selling to some of the hottest spots in NYC. Think Mission Chinese, Daniel, Atera, Pizza Loves Emily, Le Turtle, Locanda Verde, The Pool and The Grill.

"In general, they're buying things that are normally the last thing that a chef puts on the plate and the first thing the customer sees," Laing says of a list of herbs and flowers that may be unrecognizable to even the proudest foodie. Multiple kinds of sorrel and basil are just the beginning. (Pizza Loves Emily is fond of the Pluto basil, while the blue spice basil's vanilla notes would compliment any dessert.) There's also papalo, a limey herb from Central Mexico that's great for cutting the fat on rich dishes, as well as medicinal-tasting yarrow and sweet anise hyssop. Farm.One even grows something called cheese plant, which tastes just as funky as it sounds.

Beyond the accessibility to fresh or rare plants—and the intense flavor that comes along with them—another culinary win for these farms is that they guarantee chefs a certain amount of predictability and control, Boelt points out. Among the many reasons chef Tim Hollingsworth of L.A.'s Otium values his vertical garden—albeit an outdoor one—is for the control it gives him over a plant's different growing phases. For example, he can use nasturtium flowers one week or harvest them early for their capers another week.

With so many culinary perks, it's no wonder that the ag tech industry is taking off, with ambitious chefs going all in. Whether you're dining out or cooking at home, the variety of fresh and local produce is only going to get better as these farms grow, elevating the possibilities for your plate and palate—and making the watered-down, mass-harvested produce you're used to tasting even more bland. "I can't even buy herbs from the supermarket anymore," Laing says. You're next.

This month, join us as we go all in on Peak Season, taking full advantage of the bumper crop of cozy recipes, market ingredients, wine trends and entertaining gear to help you live your best fall.

5 Profitable Urban Farming Questions With Metropolis Farms

5 Profitable Urban Farming Questions With Metropolis Farms

Jack Griffin, President of Philadelphia-based vertical farming company Metropolis Farms, is known for his passionate support of the burgeoning indoor agriculture industry, whether that’s founding an industry association or representing the industry in Congress. We’re looking forward to hearing about his wide-ranging plans at Indoor Ag-Con Philly, and caught up with him ahead of that to hear more about his indoor agriculture world view.

1. Metropolis Farms has become a leader in the Philadelphia vertical farming scene. How did the farm come about?

Six years ago, I was working as the president of a merchant bank on Wall Street. Two very prominent Philadelphians came to our firm for a 25 million dollar investment to start an indoor vertical farm. After an enormous amount of due diligence I realized none of the existing farms were actually economically viable. They only thing they could grow was baby lettuce (basically crunchy water). There technical and scientific claims were a joke, and their financial projections had more in common with a game of three card monte then tier one financials. But the idea kept me up at night because economically sustainable indoor farms could not only produce food, medicine and energy, but would also create explosive local economies. If I could help build this new potential industry, cities would generate large amounts of green collar jobs to supply the existing demand while chase out the poverty and crush food deserts as a collateral consequence. It was on my mind constantly until one day I left Wall St to work on this problem myself. I made a giant list of everything that was wrong. I self-funded the research and dove in. It was a lot of work and a lot of what I call failing forward. We started on the “Mark1” about 5 years ago and here we are today with a solid commercial system at “Mark26”.

2. At Metropolis Farms, you take a ‘low tech, low cost’ approach to vertical farming. What’s the thinking behind that?

First off, we are definably not low tech. Our systems are actually among the most sophisticated in the industry. The difference is that they are designed to go up rapidly, and be operated and maintained simply with minimal training by people with high school educations instead of folks with PhDs and Master Degrees. We removed the over engineered complexity and excessive costs, not the technology. For indoor farming to truly become an industry, we need the technology to be accessible to everyone that wants grow, that means community groups and non-profits, not rich white men and cannabis farmers. We call it democratizing the technology. It has to cost less to build, grow more in less space, and it absolutely has to grow more than just baby lettuce and microgreens… We need to grow substantial nutrient dense foods to be taken seriously. Our mission is to make it possible for everyone that wants to farm to have access. That’s how we build the future.

3. You recently presented to Congress on urban agriculture. What did you learn from that experience?

While it was a positive experience, I learned that we as an emerging industry really need to step up our game. Right now, the organic farming lobby is trying to do everything it can to stop indoor farming from obtain organic status. In addition, the USDA’s current agriculture bill excludes Urban and Indoor farms from getting the same USDA funding that rural communities get. This is clearly a form of discriminatory redlining. Last year I was offered fifty million in USDA B&I funding, but only if I left the city for a rural community, because USDA B&I funding regulations actually excludes cities from funding. So I founded the National Urban Farmers Association and I am fighting to change the next agriculture bill so that city farmers have equal access to money that rural famers enjoy. We aren’t asking for a handout, just equal access. Today with almost zero funding cities like Philadelphia only have about 8 acres of urban farming. But back in 1944 city farms then called victory gardens produced over 40% of all the fresh fruits and vegetables in the United States. The difference is that back then urban farmers had access to the same funding that rural farms had. Now Urban farmers get nothing. This needs to change, and we as an industry need to stand up and change it.

4. What new tech developments in vertical farming are you most excited about implementing in your farm?

We are in final trials on a new lighting technology that reduces our cost of full spectrum lighting by about 25% (and no it’s not an LED). It also reduces the cost of direct energy use by a little over 30% and indirectly removes about 2,000 BTU’s per light for a massive savings on BTU management. Considering we already use 40% less energy than other vertical farms, this is a huge reduction. This new technology is incredibly disruptive to existing technologies and everyone’s going to want it, except of course the people making the current equipment in China, Taiwan and Japan. We plan on creating even more American green collar jobs by manufacture them at our Philadelphia factory. If all goes well, I’m actually considering showing it at the conference.

5. If you were starting out and had $1,000 to spend on an indoor farm and free space in your Mom’s basement, what farm equipment would you buy?

For either food or Cannabis, I would buy two ceramic lights and mount them in a reflective hood. Then I would add a light mover with a pair of hangers mounted on a 4 ft. piece of super strut to get better coverage and yield. Philips makes a great bulb for about $100.00 per bulb with a hood and digital ballasts that’s around $500.00. A light mover and strut should run less than $200.00. Then I would use “Roots Organic Original Soil” brand and some plane old plastic pots and saucer. Plus a good dry fertilizer for a top feed. I would recommend one of the “Down to Earths” brand dry fertilizer…they are excellent. Then get to work. This rig will grow flowing plants year round, but would be quite effective on leafy greens as well. Don’t let the low wattage fool you, these lights are powerful and full spectrum so don’t go super close to the canopy or you are going to burn your plants.

SEE JACK SPEAK AT INDOOR AG-CON PHILLY ON OCTOBER 16, 2017

3 Reasons Soilless Farming Practices Should Retain Organic Certification

3 Reasons Soilless Farming Practices Should Retain Organic Certification

by Jason Arnold | Sep 7, 2017

3 Reasons Modern Farming Practices Should Be Certified Organic

Did you know that the National Organic Standards Board (a Federal Advisory Board within the USDA) is considering a ban of modern farming techniques like hydroponics, aquaponics, and aeroponics from being certified organic?

That means that modern farmers like yourself who are investing in systems that conserve resources and allow you to grow healthier, locally grown crops closer to where people live, could soon lose the opportunity to be certified organic.

We here at Upstart University think that’s absurd and we’re taking action to ensure modern farmers like you have the ability to put an organic label on your product packaging!

In this post, we’ll look at 3 reasons why modern, soilless farming techniques should be certified organic.

(Did you know that you can submit a comment directly to the NOSB in opposition to this proposed ban?Here are some helpful talking points. )

1) Soilless grown produce is safe, nutritious and grown locally, just like consumers deserve!

The Organic label was created to signify safety, sustainability, and responsibility in food. Consumers depend on the organic label to help them identify food that is:

- Free of unsafe or unhealthy pesticides and fertilizers

- Resource efficient with effective cycling and recycling of inputs through the farm

- Free from harmful impacts to the air, water, and surrounding land.

- Created in humane and healthy conditions

And, as you know, modern farming techniques like hydroponic and aquaponic production can fit right into these criteria, yet they’re on the chopping block!

One great example of how hydroponics and aquaponics support responsible resource use and nutritious food is the decrease in food miles. Hydroponic and aquaponic systems can be built indoors or in greenhouses in/near cities, enabling fresh produce to be grown close to the consumer all year round, eliminating hundreds or thousands of miles of transportation.

This is different than most conventional soil farms, whether they’re certified organic or not.

Conventional soil farms need a lot of space, a lot of resources like water and labor, and healthy, unpolluted soil – all of which are difficult to find near or even in cities where people live!

That means they typically have to truck in their produce from much further than modern, soilless farms do – which increases the time between harvest and consumption. And as the Harvard T.H. Chan Center for Public Health reports:

“Even when the highest post-harvest handling standards are met, foods grown far away spend significant time on the road, and therefore have more time to lose nutrients before reaching the marketplace.” (1)

When food is grown regionally or locally using indoor hydroponics and aquaponics, the consumer gets a richer nutritional profile, and the environment benefits from a shorter supply chain.

The bottom line: hydroponics and aquaponics (i.e. soilless growing techniques) can actually deliver a better crop to market because of their proximity to where people live and their sustainable use of resources.

2) Soilless farming contributes positively to the economy and strengthens food security by bringing farms closer to where people live!

Modern farmers, empowered with appropriate tools and technology, are able to grow food in areas where fresh, local food has never been possible before (and bring jobs and opportunities along with them).

Doing so gives more people better access to nutritious food in previously unthinkable, ungrowable locations, like:

1) Urban food deserts like cities where land prices are high and areas with good soil are scarce.

2) Northern latitudes with harsh climates (e.g. Alaska) where the vast majority of food is shipped in and therefore lacks freshness.

3) Areas that lack abundant ground and surface water where conventional produce farms don’t stand a chance.

Modern growing techniques not only help grow food closer to where people live, they also help a new generation of farmers make a living doing what they love – growing good food!

Whether in an urban or rural location, farmers today face difficult growing conditions and even more difficult economics, and they need an edge to be successful. Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) – growing in greenhouses or indoor environments with resource-conscious techniques – allows more people to grow food and access markets.(3)

Even the former Secretary of Agriculture, Tom Vilsack, understands the power of fostering stronger local food economies saying:

“Urban agriculture helps strengthen the health and social fabric of communities while creating economic opportunities for farmers and neighborhoods.”

As part of the Upstart University community, you know this better than most. That’s because modern growers like you are helping to bring better food to those who want it and need it, regardless of where they live!

The bottom line: Evolved agricultural methods like hydroponics and aquaponics make farming more accessible, strengthen local economies, and supply fresher food to those who deserve it.

3) Conventional soil-based farming doesn’t have a monopoly on microbiology and healthy food.

Many anti-hydroponic and anti-aquaponic activists cite the lack of sun and soil as a major defect of the growing methods. After all, the soil is alive, and science has shown that plants grow better with the rich communities of microbes that give it life. If hydroponics uses rocks or coconuts husks or recycled plastic to grow, then it must be sterile, right?

Wrong.

What traditionalists fail to acknowledge is that microbes can thrive anywhere there is water, habitat, and nutrition for them. And unfortunately, the anti-hydroponic activists take advantage of the fact that most members of the general public do not have a degree in microbiology.

By using words like “unnatural, sterile, Robo-crops,” they deliberately try to confuse the public about the realities of evolved farming technics like hydroponic or aquaponic production methods.

That’s why it’s up to all of us who see the promise of modern technology that’s helping feed more people better food to set the record straight!

Much to the dismay of traditionalists, aquaponic and hydroponic systems are actually their own ecosystems teeming with life. In fact, studies show that Organic aquaponic and hydroponic production relies on a robust microflora in the root zone – made of the same types and numbers of bacteria and fungi that thrive in soil. These interactions and economies of microorganisms and plants are what makes them work so well.

The bottom line: While amazing in their own right, the soil and the sun hold no mystical powers and are not required to grow healthy, delicious food for our growing population. And, soilless systems take a deep understanding of microbiology (as well as other plant/physical sciences) and weave it into something that can grow organic food better.

But is it organic?

Lots of pixels have been spent in trying to define what organic means. The truth is that a narrow definition of organic is not helping us meet the challenge for fresh, healthy crops, grown close to the markets they are serving without the use of synthetic pesticides or fertilizers.

I agree with Mark Mordasky, owner of Whipple Hollow Organic Farm, when he says that “If we had all of our nutrients organic, all of our pesticides and herbicides — whatever we’re doing to control disease was organic, and the medium itself that the roots are growing in is also organic, all the inputs are organic. The outcome, it seems to me, would be organic.”

WARNING: Modern farming might be banned from being certified organic unless you take action.

The National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) is a group of 14 people that make recommendations to the USDA regarding the organic standards – what they should be and how they should change.

Currently, the NOSB is considering a recommendation that the USDA bans hydroponic, aquaponic, aeroponic, and other container-based growing methods from the organic standards. (Right now, growers using these methods are able to receive organic certification under the USDA’s National Organic Program, but that opportunity might soon be eliminated.)

If the USDA were to take such a recommendation, modern farmers using resource-conscious growing techniques will no longer be allowed to use the organic label and therefore be at a disadvantage when communicating the value of their produce to customers.

The option would be completely off the table – probably forever.

This would put the hydroponic and aquaponic industries at a disadvantage and will likely negatively impact organic-loving consumers by deleting a significant portion of the organic food supply.

The data shows that organic food sales continue to climb and more consumers want organic food. Are we willing to reduce the amount of organic food available by banning modern farmers from helping increase the supply?

To protect the business opportunities of today’s modern farmers and those of future soilless growers, it is critical that members of the hydroponic, aquaponic, and aeroponic community make their voices heard by the NOSB.

We believe that to provide consumers the reasonably priced organic fresh produce they want, we need as many organic producers as we can get!

(And we hate knowing that opportunities for modern farmers like you are being taken away!)

“Okay, I’m ready to fight back! How do I get involved?”

There’s a lack of unbiased information regarding how hydro-, aqua-, and aeroponics work and how changed standards would impact farmers, and that means those with the loudest megaphones have great power in this debate.

The NOSB needs to hear that there is an entire industry of modern, resource-smart growers using appropriate techniques to grow better food for people who need it.

It’s critical that you, as one of these modern farmers, make your voice heard and help even out this historically one-sided debate!

The best way to make sure your voice is heard is to tell the NOSB how this decision will affect you and your farming business. The NOSB will take your comments into account as they prepare for a vote on October 31st.

Here are 4 easy ways to take action TODAY:

1) [RECOMMENDED] Go to the NOSB Organic Comments page and write a message telling the NOSB that you believe your growing methods should remain organic. (Need some talking points? Here you go.)

2) Sign up to give a three-minute testimony at the October 24 and 26 webinars.

3) Sign up to attend the Fall Meeting in person and provide in-person three-minute testimony.

4) Contact your federal congressional representatives and tell them you want the NOSB to retain the organic eligibility of sustainable growing methods like aquaponics, hydroponics, and aeroponics. Click here to enter your zip code and find your representatives.

Should Organic evolve or stay stagnant? You decide.

If the goal of the Organic label is to empower more consumers with organically grown produce, then hydroponics and aquaponics have a lot to offer. It doesn’t make sense to restrict or exclude these methods from the Organic label.

However, this ban is what will happen if farmers like you stay quiet.

Click here to tell the NOSB you want to see the Organic label evolve!

Minnesota: Sustainable Indoor Vertical Farming In Action

Minnesota: Sustainable Indoor Vertical Farming In Action

Wisconsin State Farmer | Published 5:04 p.m. CT Sept. 16, 2017

(Photo: Associated Press)

ST. PAUL, MN - The Midwest has long been a major source of innovation when it comes to feeding the world, so it’s no wonder that the same state where Nobel Peace Prize winning agronomist Norman Borlaug was educated is now delivering on the promise of urban indoor aquaponics.

The St. Paul, Minnesota company Urban Organics, which uses aquaponics to raise fish and grow leafy greens, has already proven the viability of an idea that’s been getting national attention: year-round indoor farming. In fact, Urban Organics has been so successful in its pioneering approach that it recently added a second larger location to meet skyrocketing local demand for its fresh arctic char and salmon, and organic greens including bok choy, kale, lettuce, arugula, chard, and spinach.

In a sector of the food industry seeing substantial growth of new entrants, Urban Organics offers a highly differentiated approach to vertical farming that addresses market demand for both local and organic produce and protein.

Unlike typical hydroponic farming operations, the Company can supply produce that is USDA-certified organic by using solids produced in its fish culturing system as the nutrient source for the produce. Using natural waste products from one system as the primary input of another has substantial economic advantages and represents a far more environmentally sustainable and resource conservative approach to urban food production.

In 2014, the company opened its first indoor urban aquaponics farm inside an old St. Paul brewery complex — the former Hamm’s Brewery. Its 8,500 sq. ft. became home to a fully-operational farm which housed four 3,500 gallon fish tanks with 4,000 hybrid striped bass plus herbs and leafy greens—one of the largest and most advanced aquaponics facilities in the country. Local, national and international interest followed; England’s The Guardian called the farm one of 10 innovative concepts from around the world.

The Hamm’s farm proved the concept, as area restaurateurs and grocers demanded more ultra-fresh, ultra-local product than the location could provide. Global water company Pentair, with its main U.S. offices in Minnesota, was an early supporter of the Hamm’s location — designing, engineering and installing the innovative system with its water filtration and reuse technologies.

After the success of the Hamm’s location, Pentair and Urban Organics joined forces and expanded to a larger space in another unused urban brewery building—the 87,000 square foot Schmidt complex, which is in the middle of a revitalization including artists’ condos and a planned food hall.

That new Urban Organics Schmidt brewery location opened earlier this summer. Its 87,000 sq. ft. are home to 14 fish tanks and 50, 5-tier towering racks of greens, and when it reaches full capacity later this year, it will provide 275,000 lbs. of fresh fish and 475,000 lbs. of produce per year to the surrounding region.

The USDA-certified-organic farm has created jobs, brought life back into abandoned buildings, provided a global model for indoor aquaponics farming, and done it all without the use of pesticides - and while using significantly less water than traditional methods to grow produce.

“We started this venture as social entrepreneurs who wanted to figure out how to bring a reliable source of healthy foods into areas that had to rely on food transported in from far away,” said Dave Haider, co-founder of Urban Organics. “It turned out that our wild idea also made a lot of sense to a community hungry for organic, sustainably-raised food, and to other innovators around the world who had been asking the same questions we were. By collaborating with Pentair, we’re able to contribute beyond our immediate region - we’re able to test and perfect the technologies that will make a global impact advancing the field of large-scale commercial aquaponics.”

Urban farming is an extremely competitive endeavor, but Urban Organics continues to add products and customers. Earlier this summer, the farm rolled out nine different types of packaged greens and salads, now distributed through regional coops and grocery chains. And by next summer, arctic char growing in its tanks will be ready for harvest. Local health care provider HealthPartners, the largest consumer-governed health care organization in the nation, is now including Urban Organics greens in patient meals and serving them in its cafeterias. And restaurants, like Birchwood Café, are serving the greens as well.

Started By Four Friends, Triton Foodworks grows 700 Tonnes Of Organic Food Without Soil

Started By Four Friends, Triton Foodworks grows 700 Tonnes Of Organic Food Without Soil

- HEMA VAISHNAVI | 28 AUGUST 2017

Foraying into urban farming, a group of friends have set up a green enterprise that is based on hydroponics.

There is growing concern in urban and semi-urban areas about the dangers of the pesticide-ridden food that is sold in the market.

Following the Green Revolution in the mid-1960s, the use of pesticides in India has increased. Although the period saw the boom in agriculture like never before, the flip side of this revolution has left the country consuming poisonous food. Food production in large quantities at the cost of their health has made people wary and look for alternatives.

In the confines of an urban setting, four youngsters from Delhi are venturing into hydroponics to provide an organic and healthier option for the urban populace.

Hydroponics is the method of growing plants in a water-based, nutrient-rich medium, without the use of soil. This method essentially cuts down the amount of water being used compared to the method in which plants are grown in soil. In some cases, up to 90 percent less water is used in the hydroponics method compared to the traditional soil-based agriculture — a boon for water-starved urban areas. One can plant four times the number of crops in the same space as soil farming.

An experiment in urban farming

Triton Foodworks started as an experiment in urban farming in the September of 2014 by four friends — Deepak Kukreja, Dhruv Khanna, Ullas Samrat, and Devanshu Shivnani.

In early 2014, Ullas was exploring ways to develop his agricultural land in Mohali for his mother, who suffers from ILD, a degenerative disorder of the lungs. When the doctors told him that life on a farmhouse would in fact be counterintuitive for his mother due to dust and other issues related to farming, he became obsessed with finding a way to farm in a clean and hygienic manner.

Dhruv, who was in Singapore at the moment working on his tech startup, wanted to come back to India and start something here. On a catch-up call, the two got discussing how much fun it would be to start a business together; especially something that made sense economically and ecologically. Following a lot of research, they zeroed in on hydroponic farming, something that connected with both of them. Dhruv visited a few hydroponic farms in Singapore to see firsthand how it works. Ullas met Deepak online while researching on hydroponics. The team quickly realised that to make this thing big, they needed a formal structure and a financial disciple — which is when Devanshu was roped in.

“We were just a bunch of friends who wanted to do something in the space of food and agriculture. We were very excited by the opportunities of rooftop farming and farming within the limits of the city. We did a pilot to grow strawberries in Sainik Farm of Delhi. We used an open system with vertical towers to grow eight tonnes of strawberries out of 500 sqm of land. Eventually, we decided against setting rooftop farms due to feasibility issues. Instead, we set up full scale, commercial farms in the outskirts of cities,” says 38-year-old Deepak, technical Co-founder, who takes care of the farming aspect of the business.

Like any bootstrapped startup, Triton Foodworks also faced a huge number of issues at every step. Their farm at the Sainik Farm was demolished by the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) because the team refused to pay a bribe.

“We went to the Delhi government to ask for some sort of help in setting up farms in Delhi; we were called ‘food terrorists’ to our face. Quite a few vendors still owe us money for our early projects, something which is a huge issue in this industry. We had no previous data to map our progress against, no previous players who could be used as a yardstick in the field,” says 27-year-old Devanshu, who takes care of the finances and the financial modelling for the business.

Taking hydroponics ahead

“Toxic food is the biggest issue we are trying to resolve. People don’t realise how toxic their food really is. We don’t use chemical pesticides for our plants. The second issue is the fact that we are running out of land and water to grow food. Lastly, we are addressing the problem of traceability, consistency and, by extension, accountability in farming. You buy a bag of chips and you can trace it back to the field in which the potatoes were grown, but if you pick up a tomato from your vegetable vendor, there is no way to know where it came from, who harvested it, when was it harvested, and what all did he put in it to grow. We are teaching people to ask these questions by offering them answers even before they realise this information is important,” says 27-year-old Dhruv, who looks after operations and marketing.

The team relies on Ayurvedic recipes and bio control to fight off pests and other infections, as an alternative to pesticides and insecticides. The team grows the same amount of food grown under conventional farming with just about one-eighth of the area and using 80 percent less water.

The team has successfully set up more than 5 acres of hydroponic farms across three locations in India. The strawberry farm in Mahabaleshwar grows 20 tonnes of strawberries a year and a 1.25 acres facility in Wada district of Maharashtra that produces about 400 tonnes of tomatoes, 150 tonnes of cucumbers, 400 heads of spinach, and over 700 bunches of mint.

Triton also operates an acre facility in Shirval, Pune that grows tomatoes and cucumbers, which are used to feed farmers’ markets in Pune. The team also advises companies in Hyderabad, Manesar and Bengaluru that are interested in incorporating hydroponics.

Triton currently has over 200,000 sqft of area under hydroponic cultivation in various locations in the country. Using hydroponics, it produces more than 700 tonnes of residue-free fruits and vegetables every year.

“Our systems enable us to save around 22 crore litres of water per year as compared to traditional agriculture. In terms of volume, our vertical systems grow food comparable to 10,00,000 sqft of land when using traditional agriculture methods, which translates into a saving of more than 800,000 sqft of land to grow the same amount of food. Since our farms are located within a 100-km radius from cities, our produce carries lesser food miles,” says 27-year-old Ullas.

The team is currently in the process of setting up stalls in farmers’ markets in Pune and Mumbai.

"Towards The Green Revolution"

"Towards The Green Revolution"

2017

The vertical cultivation system aponix: The height and thus the number of planting areas of the tonne superstructures are variable. Photo: Manticore IT GmbH

Marco Tidona works as a software developer. A coincidence led him to become acquainted with the Urban Farming scene in New York. Now Tidona aponix - a vertical cultivation system for horticulture - is launching on the market, which should bring production and consumer closer together. TASPO Online spoke with the resourceful entrepreneur.

How to design a vertical cultivation system for horticulture as a software developer?

When in 1999 the Neue Markt and the Internet really started, I became a service provider. Today, I am again ready to start a new market, but this time with a product for the Vertical Urban Farming sector. In 2014, I placed an aquaponic circuit with 4,000 liters of water and 100 tilapia in private, underestimating the amount of plants that would have been necessary to balance the ever-higher concentration of nitrate in the plant.

At this time there was no simultaneously affordable, usable and vertically flexible solution on the young urban farming market. On top of that, I spent one day in New York City by chance and got an unprecedented insight into the state of the urban farming scene and the farming operations. After seeing more professional production sites and looking at the existing value chains from cultivation to harvesting through logistics to consumption by the consumer, I soon realized that we are heading towards a green revolution more purposefully.

What is the difference between aponix and common vertical systems?

There are several differences and specifically vertical systems are very different. Each system has its own strengths and weaknesses, which should be looked at and compared against one another before purchase. In case of doubt, we recommend that you first carry out a practical test. The mission of aponix is o simplify the cultivation of hyperlocal edible plants in 3D. A) for the commercial user of an urban farm with lean processes, b) the ambitious hobby grower and c) the "prosumers" - the consumers who produce some of their own food and, if necessary, have no garden.

The height and thus the number of planting areas of the tonne superstructures are variable. The barrels are constructed from similar lego-like components with different plant adapters. No fixed installations such as tables or rack systems are required. Everything is mobile, modular and scalable. In principle one can understand the system of aponix as a kit, with which one can configure many different urban solutions. In the summer, additional elements are added that can be used to assemble substrate-based tonnages, which can then be used as a raised-bed alternative for the balcony or also as a gray-water filter. We show these examples on our website.

How are the plants supplied with nutrients? How many plants fit into such a system?

In the earthless version one can work with mineral or organic fertilizer - hydroponics or aquaponics. In the summer, additional parts are added, with which one can build a ground-based version. For the groundless version, we usually sell the variant with a height of 12 ring segments. Each ring segment provides 12 2-inch mesh head racks, thus accommodating 144 herb or salad plants. A tonne has a diameter of 57 centimeters.

The height of the barrels can be changed at any time. Irrigation by means of sprinkler and gravity works independently of the height always over a lid. It is possible to combine several tonnes into a production line and manage the reservoir centrally or operate a single tonne.

What is the advantage for horticultural companies using this system?

If we want to move the production closer to the end user (= hyperlocal) in order to get the average 1,500 "food miles" in the existing value chain to zero and thus offer the end user significantly more diversity, freshness and nutrients, the mounting surfaces become significantly. In decentralized distributed urban micro-farms, it will be important to operate cultural areas of less than 1,000 square meters profitably.

This is only possible with a high plant density and a competitive offer. The freshness, sustainability of the production and the absence of herbicides / pesticides will, among other things, be the key for the mature consumer to pay a small extra charge compared to the standard merchandise from the supermarket and the discounters. It feeds on the highest nutrient level and with the greatest pleasure.

What about the renaming process during the project phase? Was the conflict with another product from the same industry or a "foreign" industry?

Originally we had called ourselves 'ponix' in the prototype phase and had a fish symbol around the logo. Shortly thereafter, a company from Austria came onto the market with the name 'Ponix Systems'. Since in most cases alphabetical sorting is carried out, we have made the renaming easy here, and a 'a' has been hanged, and from the fish on the occasion a lying "infinite 8" is made as a sign for the upcoming Circular Economy.

Created by TASPO Online

For Profit Hydroponic Farm in Chicago Seeks to Increase Employment Opportunities in Underserved Community

Since its inception in 2013, Garfield Produce has been working to improve economic growth and employment opportunities for Garfield Park community members. The for-profit business was born from a collaboration between a successful retired couple, Mark and Judy Thomas, and an engineering major from DePaul University, Steve Lu.

For Profit Hydroponic Farm in Chicago Seeks to Increase Employment Opportunities in Underserved Community

September 7, 2017 | Charli Engelhorn

Darius Jones, general manager, vice president, and part of owner of Garfield Produce, an urban hydroponic farm located in Garfield Park, a west-side community in Chicago. Photo courtesy of Garfield Produce.

“Education is the most important thing,” says Darius Jones, general manager, vice president, and part of owner of Garfield Produce, an urban hydroponic farm located in Garfield Park, a west-side community in Chicago. “We’re trying to create an environment that inspires people to grow and feel valued.”

Since its inception in 2013, Garfield Produce has been working to improve economic growth and employment opportunities for Garfield Park community members. The for-profit business was born from a collaboration between a successful retired couple, Mark and Judy Thomas, and an engineering major from DePaul University, Steve Lu.

Through missionary work with the Breakthrough Urban Ministries, Mark and Judy saw that their misconceptions about poverty—that it is the result of laziness and not taking advantage of the same opportunities afforded to others—were inaccurate, according to Jones. What the Thomas’ discovered was that people did want to work, but there were no opportunities available and a number of systemic obstacles in place that hindered people’s ability to work.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, Garfield Park changed from a predominantly Caucasian community to a predominantly African-American community, and most of the equity that existed has been removed over the past 25 to 30 years. As one of the top five communities in the city for crime rate and poverty, the infrastructure in the community has degraded, leaving close to 3,000 abandoned buildings and facilities and no real job opportunities, says Jones, a Garfield Park native.

“When they came to Garfield Park and saw how things were, they decided there needed to be some kind of business opportunity or job opportunity offering entry-level positions, since most of those available are located in far suburbs, requiring nearly a two-hour commute for a minimum wage job,” Jones says. “Steve brought in the urban agriculture component.”

As a young company, the current focus is building the business and increasing its income to be able to support more entry-level positions. This action is happening through relationships with Chicago-area chefs, catering companies, and restaurants, and will possibly expand to include a relationship with Whole Foods, which has approached Garfield Produce about carrying its products in their stores.

“We would love that relationship because it will help us scale faster,” says Jones. “Any dollars spent on our business go directly into a community member’s pocket. We’re tracking key performance metrics so we can show our customers where their dollars are going and how many hours of gainful employment their spending affords.”

Garfield’s vertical hydroponic farm, housed in a 5,600-square-foot facility, yields approximately 2,000 to 5,000 pounds of 25-30 varieties of specialty micro greens and micro herbs, such as pea tendrils and greens mixes, a year. The farm’s production modules currently occupy only 320 sq ft. Another 2,200-square-foot grow room is in development, which will increase production to 21,000 pounds a year and add another five to 10 varieties of greens.

The hope is that this greater yield will translate into more income, allowing the company to increase their workforce from two—Darius and one grower—to approximately 11 with the addition of another grower and grower’s assistant, a sales position, and six more entry-level positions.

“We’re talking about entry-level positions that would make a little more than minimum wage, but we’re setting up the company so employees can have ownership,” Jones says. “We want the business to be fully employee owned, so even though an entry-level job wouldn’t be life-altering, equity in a company would be.”

The main challenge in employing members of the community is finding people with enough knowledge and training. The company hopes to overcome this impediment by working with local organizations that do job training for the area’s large number of people with felony convictions, which accounts for 65 percent of the population, according to Jones, who went through a similar job-training program seven years ago.

“A lot of these guys will go through three to nine months of transitioning job training through organizations that get state or federal money, and in some areas, that includes sustainable urban agriculture training, but once they are finished, there are no jobs for them,” Jones says. “This is perfect for us because providing these jobs is exactly what we want to do.”

The company also continues to work with Breakthrough Urban Ministries, which, as well as providing men’s and women’s shelters, a food pantry, and a healthy food kitchen, supports the people in their housing program with entry-level job training. The one employee besides Jones was found through the ministry’s men’s shelter in 2014.

The partnership with the ministry also includes donations of leftover harvested greens to the food pantry. Jones would love to expand this partnership to include more activities, such as food demos, but admits that part of the downside of a for-profit business is a lack of logistical feasibility to get out and educate the public with efforts that are not sales-based, an issue that also influences their customer base.

“We don’t have the manpower to be out marketing and educating the community about our products. So, right now, we are looking to bring dollars into the business, get it built up, and then start pushing the products into the community,” says Jones.

Jones wants the business model to be scalable, sustainable, and replicable so they can take it to another of the many underutilized facilities on the west side of Chicago and build the same footprint using the same sales channels to make it profitable for other communities.

“We’re not just an organization coming into a neighborhood without knowing anything about it; we’re coming in with knowledge of the neighborhood,” Jones says. “We know most of the local consumers think micro greens are too expensive, so we can talk to the people in the community about what urban agriculture is and the benefits of micro greens, find ways to use more economical packaging and bring the costs down so local consumers are not scared away.”

Garfield Produce will begin opening its doors to community members for tastings soon and hopes to increase its education efforts by working with local schools. The company is already in partnership with Nick Greens Grow Team, a group specializing in hydroponic and controlled-environment agriculture, to sponsor hydroponic systems in schools so students can learn the importance of growing their own food and use the food they grow in their lunches.

What Are Novel Farming Systems?

What Are Novel Farming Systems?

AUGUST 29, 2017 | LOUISA BURWOOD-TAYLOR AND EMMA COSGROVE

Novel farming systems are new methods of farming living ingredients, many of which are traditionally grown outdoors.

Consumers are scrutinizing the agrifood industry more than ever for its widespread use of natural resources such as water and arable land, and for its negative impact on the environment. The agrifood sector is neck and neck with heating and cooling as the global industry producing the most greenhouse gases. Industrial farming can also have a damaging environmental impact with the application of chemicals and fertilizers contributing to soil degradation, drinking water contamination, and run off harming local ecosystems.

As a planet, we are also faced with the challenge of increasing food production despite decreasingly nutrient-dense soil and a warming planet. While some are attempting to lessen the extractive nature of conventional farming in soil, or to create seeds and crops that can thrive in these new conditions, others are working on removing land and soil from the equation altogether.

To alleviate these pressures, startups and innovators are finding new ways to produce food and ingredients with novel farming systems in the hope of doing so more sustainably, using fewer natural resources.

Further, many novel farming systems focus on the farming of fish, insects, and algae which have the potential to alleviate the environmental pressure of increasing global demand for protein, where cattle farming is bearing the majority of the burden.

Novel farming systems have also emerged as a captivating solution in the eyes of the public and investors precisely because they could change the paradigm of traditional agriculture so dramatically. Though, as we will explore in our upcoming agrifood tech investing report, public and media excitement are not always met with equal investment.

Novel farming systems, as a category of agrifood tech, includes:

- Indoor farms — growing produce in hi-tech greenhouses and vertical farms

- Insect farms — producing protein alternatives for animal and aquaculture feed and for human food

- Aquaculture — producing seafood and sea vegetables including algae

- New living ingredients such as microbes for use in food, as well as for other industries and applications

- Home-based consumer systems using the technology of any of the above

Here is a closer look at the components of our novel farming systems category of startups ahead of the AgFunder MidYear AgriFood Tech Investing Report.

Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) or Indoor Agriculture

The concept of farming indoors in not new; greenhouses have been around for centuries. But in recent years, greenhouses and more insulated indoor spaces like warehouses and shipping containers are rapidly picking up pace as a means to grow food closer to consumers, remove many of the unpredictabilities of outdoor agriculture, and drastically reduce the inputs necessary for outdoor farming.

There are only a few key ingredients needed to grow food: light, water, and nutrition. By growing food in a controlled environment, indoor farmers aim to give plants the perfect amount of each, reducing waste, but also maximizing yields. They can also manipulate the doses of each of these ingredients to impact flavor, color, and texture.

Tomatoes, strawberries, peppers, leafy greens, herbs, flowers, and cannabis are all frequently grown in controlled environments. Greenhouses specifically are also an important part of the tree crops industry as most rootstock starts in a greenhouse.

By some estimates, there are more than 40,000 indoor farming operations in the US alone, producing food worth more than $14.8 billion in annual market value. These numbers exclude the cannabis industry, which brings in an additional $6.7 billion in sales.

The different configurations of CEA include greenhouses and indoor vertical farms, and within these two categories, there is much variation in terms of physical growing structures and architecture, delivery systems for light, water, and nutrients, light source, growing medium, automation, data collection, and environmental controls.

Greenhouses

Greenhouses are covered structures made of glass or plastic that allow sunlight to get in but offer varying degrees of temperature control. They have been used commercially to grow fruits and vegetables for decades, but there are various ways greenhouse technology is being used today beyond its simplest form of growing plants under glass in pots of soil.

Soilless hydroponic growing systems — where the plants are grown in a watery medium as opposed to soil — have been used in greenhouses for more than a decade by major growers like Village Farms and Backyard Farms. And today, computer vision, artificial intelligence, automation, and precision agriculture techniques are arriving at the greenhouse. Some greenhouses are fully kitted-out with sensors using machine learning to detect disease, facilitate efficient use of space, and identify anomalies both within the environment and with individual plants.

Some greenhouse technology has come a particularly long way, with incidences of hybrid greenhouse and indoor operations growing cannabis, like Supreme Pharmaceuticals, as well as innovative locations — like Gotham Greens above Whole Foods in Brooklyn, New York — and business models.

Main greenhouse crops today include lettuces and, leafy and micro greens, tomatoes, peppers, and cannabis.

Vertical Farms

Ranging from as small as a shipping container to as large as an airplane hanger, indoor vertical farms are growing steadily in number, although some have already failed in what’s a capital intensive field.

Most operating vertical farms today are growing only leafy greens and microgreens due to the short growing cycles and high yields. There are a few growing strawberries such as Japan’s Ichigo Company.

Vertical farms use LED lights for photosynthesis and some form of hydroponics for water and nutrition. The fairly simple equation is nutrient-enriched water, moved either in a mist or through channels or tanks around the roots of plants. The roots are planted in various media ranging from spun concrete to coconut husks to cloth, which are submerged in the water or mist.

Every one of the elements involved in growing the plants can be manipulated precisely to influence the outcome — such as lighting wavelengths, timing, the types of nutrients, and so on. This can be particularly effective if sophisticated data collection and analytics are in place; many farms claim that their own internally-created software and hardware tools enabling this are their main differentiator.

The largest vertical farms by capital raised include AeroFarms, Bowery Farming, and Plenty which are all starting to use artificial intelligence and machine learning to manage their plants and boost yields.

Robotics are also slowly making their way into indoor agriculture, though they are currently only used for crops that grow in containers such as rootstock for apple, cherry, and almond trees, and in these cases, the robots move the containers as opposed to more complicated tasks. But fruit-picking and sorting robots are on the way with several startups in the space making advancements and raising funding. (Stay tuned for our Farm Robotics deep-dive article coming soon!)

Aquaponics

Aquaponics is a smaller subset of indoor farming where farmers grow vegetables integrated with, and on top of, fish farms, so that the waste generated by the fish can fertilize the plants. The technology set up is very similar to a vertical farm, but the monitoring of the input composition and the physical layout differ greatly from operations purchasing plant nutrition. Aquaponics operations, like Edenworks in New York and Organic Nutrition in Florida, sell both vegetables and fish.

Aquaculture

Aquaculture is the cultivation of sea creatures and vegetables for human and animal consumption.

According to United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization data from 2010, aquaculture makes up half of the seafood consumed by humans today. This includes the farming of all varieties of fish, along with oysters, scallops, shrimp, mussels, and other shelled creatures. Most of the innovation in this space is currently geared towards fish feed for farmed fish rather than the technology used at the farms themselves. Fish feed is a particularly crucial challenge as currently 30 million tons of wild caught fish per year are used to feed farmed fish, which is a third of global wild fish harvest. With global stocks of wild fish declining, and some sources pointing to the crash in some forage fish populations, this is an unsustainable source of food for farm-raised fish long-term, even with increasingly sustainable practices employed by the fishmeal and fish oil industry. This problem, valued at $100 billion, will likely be solved at least in part by some of the other types of novel farming systems listed here, especially insect farming.

Algae farming represents an underdeveloped sector within novel farming systems but has great market potential. It has been estimated that the algae market will reach $45 billion by 2023 and algae, especially macro algae like edible seaweeds, are farmed in most cases completely without technology or digitalization. Macroalgae can be grown in open water as well as in tanks while most microalgae, which are single-celled, must be grown in a controlled setting. Algae farming startup EnerGaia is growing spirulina (microalgae) on rooftops in Bangkok, Thailand.

Microbe farming

Microbe farming is another emerging field with various applications. Ginkgo Bioworks, for example, genetically engineers microbes for partner companies in the flavor, fragrance and food industries. These microbes are primarily forms of yeast or bacteria that can be designed to replace a natural alternative; rose oil, for example, would be expensive for some companies to manufacture as an ingredient given that roses are not a commodity crop. But Ginkgo can manufacture that fragrance or flavor in-house by writing new DNA code to re-program the genome of a microbe to have it do what customers want. These DNA designs are proprietary to Gingko, as well as the robotics and other technology the company uses to culture the microbes, mostly through a fermentation process. Zymergen and Novozymes are other startups growing microbes, in these cases to make agricultural inputs.

Insect & worm farming

Insects and worms are set to become an increasingly important protein source for both animals and humans with demand far outpacing supply. Insect farming is mainly touted as a more sustainable alternative to animal protein, particularly as the quality of the protein insects offer is actually quite high. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO), “insects have a high food conversion rate, e.g., crickets need six times less feed than cattle, four times less than sheep, and twice less than pigs and broiler chickens to produce the same amount of protein.” Further, insects require very little land or energy to produce, and they can be produced quickly and all year round, unlike other animal feedstock such as soybeans. Insects can serve as a protein-rich substitute for the aforementioned wild-caught fish that are often used as aquaculture inputs, potentially turning aquaculture into a sustainable solution to overfishing. Netherlands-based Protix makes animal and fish feed as well as fertilizer from black soldier flies.

Crickets, fruit flies, grasshoppers, and mealworms are all also being cultivated for inclusion in consumer products in this nascent industry. Grasshopper farms like Israel’s Hargol, are racing to get their production capacity up since the demand for alternative proteins for both animals and humans remains much higher than current supply. While very secretive about their designs, many insect farming groups claim to have very high-tech operations using robotics, to create automated insect farming factories, such as Ynsect in France.

Consumer growing systems

Home paramours for almost every novel growing system exist, whether or not they’ve gone mainstream (yes even insect farms). Tabletop hydroponic systems like Plantui, aquaponic systems that have decorative fishtanks topped with produce like Grove, and even mini refrigerator-sized growing towers like Hydro Grow, are available for the shortest farm-to-table experience out there.

Your Produce Might Soon Grow In A Warehouse Down The Block

Plenty, Inc. is changing the way that we farm. Instead of modernizing agriculture by developing ways to keep fresh greens fresh throughout transportation, this San Francisco-based company is doing away with transportation — or at least a huge chunk of it, thanks to vertical farming.

Your Produce Might Soon Grow In A Warehouse Down The Block

IN BRIEF

Vertical farming is changing agriculture. With its capacity for more quality produce at cheaper costs, the San Francisco-based startup Plenty wants to help put a dent in the global food shortage — and they just received $200 million to do so.

MODERN-DAY FARMER

Plenty, Inc. is changing the way that we farm. Instead of modernizing agriculture by developing ways to keep fresh greens fresh throughout transportation, this San Francisco-based company is doing away with transportation — or at least a huge chunk of it, thanks to vertical farming.

As its name implies, vertical farming is essentially planting in stacks instead of a typical field. This method saves space and eliminates the need to acquire huge parcels of land before to grow crops. It’s an idea that’s especially attractive now that more people are opting to live in cities, and transporting fresh farm produce can be troublesome. Best of all, this can be done inside warehouses or other indoor spaces located within cities.

Plenty has received $200 million in funding — the largest investment in an agricultural technology ever — from Japanese telecommunications giant SoftBank, enough to put vertical farms in 500 urban centers with over a million people.

MORE EFFICIENT FARMING

Instead of using stacked, horizontal shelves like most vertical farms do, Plenty uses 6-meter (20-foot) tall vertical poles from which plants jut out horizontally. These are lined up next to each other, with about 10 centimeters (4 inches) of space in between. Infrared cameras and sensors placed among the plants monitor conditions regularly, and Plenty’s system can adjust the LED lights, humidity, and air composition in their indoor farms.

Image credit: Plenty, Inc./Fast Company

These plants are fed nutrients and water from the top of the poles, so this setup doesn’t even require soil. “Because we work with physics, not against it, we save a lot of money,” co-founder Matt Barnard told Bloomberg. This setup, Plenty claims, can grow 350 times more produce in a given area than conventional farms. Plus, all the accumulated water can be fed back into the system, so the process only really uses about one percent of the water that a regular farm would need. All of this means that a significant amount of fresh produce could be planted and grown in cities. This would mean good quality produce at potentially lower costs. Plenty’s San Franciso indoor farm, for example, can produce 2 million pounds of lettuce each year within a space that’s no bigger than an acre. “We’re giving people food that tastes better and is better for them,” Barnard said.

Life On Mars A Possibility With New Indoor-Farming Technology

Life On Mars A Possibility With New Indoor-Farming Technology

September 1, 2017

A US-based company has developed technology that can replicate any kind of climate inside a shipping container, bringing sustenance on a mission on Mars one step closer to reality.

The company, Local Roots Farms, has joined forces with Space X, a company that's trying to get people to Mars. (File photo/ Reuters)

A company in California says it could be the first to grow food on Mars.

Local Roots Farms has developed an indoor farm that could feed astronauts on longer-term space missions.

They say their technology will also benefit the earth as it uses less water than traditional farming techniques.

TRT World’s Frances Read reports from Los Angeles.

How Does the Hamptons Garden Grow? With a Lot of Paid Help

The hardest-worked muscles may be in the hand writing the checks: These lavish, made-to-order gardens can cost as much as $100,000, said Alec Gunn, a Manhattan landscape architect whose firm designs high-end residential, commercial and public-works projects throughout the country.

How Does the Hamptons Garden Grow? With a Lot of Paid Help

The vegetable garden of Alexandra Munroe and her husband, Robert Rosenkranz, in East Hampton, N.Y., is sheltered from the ocean winds by dunes covered with Rosa rugosa.

DANIEL GONZALEZ FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

By STACEY STOWE

SEPTEMBER 5, 2017

EAST HAMPTON, N.Y. — The rigors of vegetable gardening, for most people, are humble and gritty: planting, weeding, dirtying knees, working up a sweat and maybe straining a back muscle or two.

But here on the gilded acres of Long Island’s East End, a different skill set often applies: hiring a landscape architect to design the garden, a gardener and crew to plant and pamper the beds, and sometimes even a chef to figure out what to do with the bushels of fresh produce. All that’s left is to pick the vegetables — though employees frequently do that, too.

The hardest-worked muscles may be in the hand writing the checks: These lavish, made-to-order gardens can cost as much as $100,000, said Alec Gunn, a Manhattan landscape architect whose firm designs high-end residential, commercial and public-works projects throughout the country.

The gardens that the chef Kevin Penner manages for a three-home compound in Bridgehampton, have a formal parterre design with gravel paths separating geometric planting beds, lined with trimmed boxwoods and filled with vegetables, flowers and herbs.

DANIEL GONZALEZ FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

“And it is not the plants that are driving the cost,” Mr. Gunn said. One 2015 project of his in Southampton with a six-figure price tag includes an underground irrigation system, a potting shed, an orchard and a meadow for a cutting garden. Many gardens require expensive hedges or other barriers to protect them from ocean winds and the ubiquitous deer.

The bespoke vegetable garden, these days almost always organic, has become a particular object of desire in the Hamptons. More clients have commissioned elaborate gardens this summer than ever before, say members of the support staffs who toil on them.

“I put in 10 by July,” said Charles R. Dayton, the owner of an East Hampton landscaping company whose ancestors have owned and worked land here since 1640. “I get a kick out of it.”

About 500 farms remain on the fertile East End, even as more mansions crop up each summer on former potato fields. And the kitchen garden has been a tradition on Long Island estates since the 19th century. But today, growing your own produce is a much different enterprise on what has become some of the world’s most expensive real estate.

Two landscape architects said clients this summer had asked that their vegetables be picked, packaged and put on the Hampton Jitney for use in city kitchens. (The cost, $25 to $50 a parcel, is often more than for a passenger.) One gardener, Charlene Babinski, said she had installed a “juicing garden” for her client’s favorite liquid diets.

Then there are the hostess gifts and holiday honey for guests. “One client asked me to make 27 baskets of vegetables to give to her friends,” said Paul Hamilton, a Montauk farmer who plants and maintains seven luxe gardens.

Preserved vegetables from the garden of Carole Olshan and her husband, Morton, in East Hampton.

DANIEL GONZALEZ FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

What’s driving the gardening bug among the affluent, gardeners say, is their clients’ focus on “self-care” — a curious phrase for a pursuit that requires so much help. Mr. Gunn said the impulse includes a “moral component.”

“There’s so much wealth,” he said. “It’s ‘Let’s take something I’ve been fortunate to have and put it back into the environment. I want to do something to reduce what I’m taking.’ ”

Christopher LaGuardia, a landscape architect based in Water Mill who designs raised beds with black locust wood for vegetables and herbs, said his clients were interested in reducing their carbon footprint by producing vegetables that don’t need to be trucked in. “Plus, they are contributing to biodiversity, pollinators,” he said. “We discourage the big lawn.”

Cabbage growing in a garden designed and tended by Paul Hamilton in East Hampton.

DANIEL GONZALEZ FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

But others liken the professionally tended garden to a vintage car or a Hinckley yacht — yet another means of flaunting wealth.

“I think people have just run out of status symbols,” said Steven Gaines, whose 1998 book, “Philistines at the Hedgerow: Passion and Property in the Hamptons,”tracked the peregrinations of its richest and most colorful residents. In the years since the book was published, said Mr. Gaines, who lives in Wainscott, in East Hampton, “it’s all gotten more intense — the competition has taken over in all sorts of peculiar ways.”

“God has given you too much money when you have someone else tend your vegetable garden,” he said.

FOR ALEXANDRA MUNROE, the senior curator of Asian art at the Guggenheim Museum, the roughly 5,000-square-foot vegetable garden — she calls it the Farm — just outside the 1928 neo-Palladian home she shares with her husband, Robert Rosenkranz, is “the center of the meal.”

“We feast here,” Ms. Munroe said, gesturing toward the flower-fringed vegetable garden nestled on a rise overlooking Georgica Jetty, on West End Road in East Hampton. In addition to a pool and tennis court, the property includes a billiards terrace and croquet green; a hedge of Rosa rugosa protects the garden from winds.

Mr. Hamilton plants, weeds, hand-waters and harvests the vegetable garden, while four other gardeners work on the remainder of the five-acre property, which has perennial beds, a meadow and woodland gardens designed by Ms. Munroe, who hosts self-guided tours.

Broccoli in Ms. Munroe’s East Hampton garden.

DANIEL GONZALEZ FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

She is known to get her hands dirty. But when she arrives at the house for the weekend, there is often a basket brimming with the garden’s harvest, arranged by Mr. Hamilton or the estate manager, Robert Deets.

“There is no greater thing than eating produce that’s still warm from the sun that has never seen a refrigerator,” Ms. Munroe said.

Iris Keitel, a retired music industry executive who lives in Manhattan and on Meadow Lane in Westhampton Beach, tore up her Har-Tru tennis court two years ago and hired the organic gardener Suzanne P. Ruggles to plant alliums, Green Zebra tomatoes and a cornucopia of vegetables. Ms. Ruggles does most of the work, but Ms. Keitel picks her own vegetables.

“My friends and I come here to play,” Ms. Keitel said, standing next to a patch of blooming cardoons that resembled a Dr. Seuss creation. Ms. Keitel, who had a bat house and a bee pollinator installed near the former center court, cooks recipes like cucumber gazpacho, rainbow radishes with butter, and zucchini fritters with those friends.

At the home of Carole Olshan and her husband, Morton, trumpet vines form an arch over a bench in kitchen garden of their private chef, John Hamilton.

DANIEL GONZALEZ FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

At the ivy-draped Further Lane home of Carole Olshan and her husband, Morton, Ms. Olshan said friends like to tour the vegetable garden designed and maintained by Mr. Hamilton and set off by a picket fence on meticulously landscaped grounds.

She said Mr. Hamilton had expanded her botanical knowledge. “We can’t call them weeds,” she said with a chuckle. “They’re native plants.”

The family chef, John Hamilton (no relation to Paul), creates meals around the seasonal offerings that Paul Hamilton brings in from the garden. A recent lunch included golden and Chioggia beets, sliced cucumbers and wasabi caviar. “I told Paul to cut the kale — so sick of it,” Ms. Olshan said.

A multicolored carpet of baby salad greens in the kitchen garden of the chef John Hamilton, at the Olshans’ home.

DANIEL GONZALEZ FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

Kevin Penner, a personal chef who headed the kitchens at Cittanuova and the 1770 House in East Hampton, manages 36 raised-bed gardens and berry bushes at a contemporary, three-home compound on Meadowlark Lane in Bridgehampton. The variety of heirloom vegetables and exotic herbs — from the buckler leaf sorrel he includes in salmon dishes to the La Ratte potatoes he uses to replicate Joël Robuchon’s potato purée — reflects Mr. Penner’s childhood on an Iowa farm and three decades as a professional cook.

“I have control over the quality of the product with this garden,” he said. “You can get lots of heirloom products, but, if you put it on a rail car the week before you get it, it’s not the same.”

Squash growing in geometric planting beds bordered by trimmed boxwood hedges in this vegetable garden in Bridgehampton.

DANIEL GONZALEZ FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

At his waterfront estate on Oregon Road in Cutchogue, on the North Fork, a hedge fund manager stocks a cold cellar and freezer with fingerling potatoes or sauces of Brandywine tomatoes from a large vegetable garden.