Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

McNamara: “To Fix The Food System, Move It Back Into The Hands of More People”

Brad McNamara, CEO and co-founder of Freight Farms, is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery,” which will be held in collaboration with Tufts University and Oxfam America on April 1, 2017.

Brad McNamara, CEO and co-founder of Freight Farms, is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery,” which will be held in collaboration with Tufts University and Oxfam America on April 1, 2017.

Freight Farms is an agriculture technology company that provides physical and digital solutions for creating local produce ecosystems on a global scale. Brad and his co-founder, Jon Friedman, developed the company’s flagship product, the Leafy Green Machine, to allow any business to grow a high-volume of fresh produce in any environment regardless of the climate. His hope is for Freight Farms to be scattered across the globe making a dramatic impact on how food is produced.

Food Tank had the chance to speak to Brad about his work developing Freight Farms and his vision for the future of our food system.

Brad McNamara, CEO and co-founder of Freight Farms, is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery.”

Food Tank (FT): What originally inspired you to get involved in your work?

Brad McNamara (BM): It was a coming together of many different factors. My co-founder, Jon, and I had worked together in the past, and we were both intrigued by the food system and how we could make a difference. Around 2009, Jon was focused on food systems and system design, and I was passionate about the purity of food and the increasing trend towards food awareness. When the two of us first reconnected over a cup of coffee (and then a beer), we got to talking about the complexity of the food system and what we could do to combine our interests. With backgrounds in design and environmental science, our goal was to research methods to allow urban agriculture to emerge as a competitive industry in food production. We mainly focused on rooftop development, then determined the criteria for success and scale to be outside the realm of possibility with agricultural installations that were already in existence. When costs and logistics soared, we turned to shipping containers (there’s Jon’s design background coming into play), and the idea for Freight Farms took off with the goal to build farms in areas that couldn’t support more traditional methods.

FT: What makes you continue to want to be involved in this kind of work?

BM: Our world and our climate are changing, and it is so apparent that there is more work to be done. According to the U.N., food production needs to increase 70 percent by 2050, to feed an ever-urbanizing population. Land and water scarcity take on even more pressing importance, as does urban agriculture. The future is so much bigger and more complex than we could have ever imagined. Over the past few years, we’ve gotten to witness the emergence of a new industry of agriculture technology, and it’s poised to make a dramatic impact on the food system. One of the most amazing things we’ve been able to watch is how many are interested in joining the movement towards a better future. Our network of freight farmers are making dramatic impacts on their local food systems every day, drastically improving food security in their community. They inspire all of us to continue this work.

FT: Can you share a story about a food hero who has inspired you?

BM: My food hero is a customer of ours. His name is Ted Katsiroubas, and he runs Katsiroubas Bros. Fruit and Produce, a wholesale produce distribution company located in the heart of the city of Boston. The business is over 100 years old and was handed down from generations before. I admire how Ted has innovated in the face of a dramatically changing food landscape. As the demand for local, fresh produce has risen, the company expanded to begin working with local farms in the region to meet demand. For those familiar with wholesale distribution, sourcing locally can be a difficult task especially when you are restricted by the growing seasons and volume constraints of small local farmers. That’s why traditionally wholesale distributors rely on shipping produce long distances from warmer climates. But Ted brings a fresh approach to an old school industry. He continues to push the envelope and propel the industry to stay on top of the latest technology through collaboration with other distributors. If anyone were to fall into the category of my food hero, it would be Ted because of his willingness to look to the future and go against the conventional wisdom of how the food industry tells him to conform.

FT: What do you see as the biggest opportunity for fix the food system?

BM: I think the biggest opportunity to fix the food system is to bring it back into the hands of the people. By transitioning to a more decentralized food system, and minimizing the gap between consumers and producers, we will take a critical step towards an environmentally and economically sustainable food system. I think all the various types of technology, the hardware, the software, and the social awareness, all point in the direction to empower the individual. So the real opportunity to fix the system is to utilize what we know to be true—when you give opportunity and power to regular people from all walks of life, that’s when you can change a whole system.

FT: What would you say is the most pressing issue in food and agriculture that you would like to see solved?

BM: There are so many people advocating for a better food system, and we all must be better at communicating and cooperating if we want to make an organized effort to challenge the way things operate currently. From small farmers and producers to organizations and companies. What has become incredibly apparent in the past couple decades is that there is no one size fits all solution. Whether it’s urban or indoor agriculture, hydroponics, aeroponics, aquaponics, or traditional soil-based farming, we all play an important role. We need to have a more holistic view of the food system and how each method can contribute to a better future. If we don’t all work together, it’s going to be difficult to disrupt BigAg. I think taking a broader view is key. There has been so much progress made in agriculture, but we still have a long way to go to create a food system that will serve future generations. It is important to continue working with and connecting with each other to empower and support the next generation of farmers.

FT: What is one small change everyone can make in their daily lives to make a difference?

BM: Maybe it is a bit cliché, but the notion of voting with your dollars. I’m sure others have said it, but it is so important. If every consumer changed 5 percent of their food shopping habits by buying more seasonal and local produce, the impact would be enormous in changing the landscape of the local grocery store.

FT: What advice can you give to President Trump and the U.S. Congress on food and agriculture?

BM: My advice is to be conscious of all the complexities present within the food and agriculture system. There are so many moving pieces that small shifts in the workforce, water use, and the climate have a massive impact throughout the entire system. It is essential to keep a holistic understanding of the relationships between all the components in our food and agricultural system and to consider the ripple effect policy decisions will have on the smaller players involved.

Click here to purchase tickets to Food Tank’s inaugural Boston Summit.

Brad McNamara, CEO and co-founder of Freight Farms, is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery.”

SXSW Just Showcased The First-Ever Traveling Indoor Farm

SXSW Just Showcased The First-Ever Traveling Indoor Farm

March 16, 2017

Each year some of the most imaginative and innovative minds from all over the world gather at South by Southwest (SXSW) in Austin, Texas. The first-ever traveling indoor farm was presented this week.

The SXSW trade show offers exhibitions that range from promising startups to well-established global corporations, affiliate KEYE reported. Companies from across the world descend on Austin to display their products in hopes of catching the eye of an investor, networking or just showing what they have to offer.

Local Roots has created a traveling indoor farm that uses a scalable, proprietary growing system that promises to provide "predictable production and quality."

"We have a circulating irrigation system and we recapture all of the water that flows through the system to reduce our water consumption down just what the plant needs to be able to grow," said founder and CEO of Local Roots Eric Ellestad.

Ellestad said his company is proof that technology is needed everywhere.

"The root zone lives down in the irrigation system drinking its nutrient-filled water day in and day out," Ellestad said.

Local Roots compares their technique almost the same as outdoor farming since they are using the same seeds, nutrients, minerals and light to activate photosynthesis. The major differences are that the light is supported by LED lights instead of the sun. The soil has also been removed in order for plants to be able to collect dissolved nutrients in the water.

The California-based company promises that their plants grow twice as fast and plants grow with much higher nutrient densities.

This Bronx Distribution Hub Could Help Local Farmers Reach More Tables

This Bronx Distribution Hub Could Help Local Farmers Reach More Tables

GrowNYC's Marcel Van Ooyen is working to launch a 75,000-square-foot food distribution hub in Hunts Point

By Cara Eisenpress

Van Ooyen wants to serve local and midsize farmers in the state.

The popularity of farm-to-table eating has created demand in the city for a local farmers’ wholesale market. Gov. Andrew Cuomo in August committed $20 million to fund a 75,000-square-foot food-distribution hub in Hunts Point and chose GrowNYC to develop and operate it. The 40-year-old nonprofit runs farmers’ markets and community gardens as well as recycling, composting and education programs. The Bronx distribution hub is the biggest project Marcel Van Ooyen has taken on in his 10 years as GrowNYC’s head. He said he hopes it will open in early 2019.

What's the purpose of the hub, and how will it work?

The hub will source, aggregate and distribute locally grown produce to food-access programs and like-minded restaurants and retail outlets. We anticipate well over 100 farmers will benefit. Farmers who grow for the wholesale markets will deliver large quantities to us. We'll break it up and distribute to public and private buyers. We'll have additional space for farmers to store food, and eventually light processing.

Why build it?

Ninety-eight percent of what we eat comes through wholesale channels. The current hub for local farmers is only 5,000 square feet, so we will replace it to serve more of them.

The limiting factors to supporting local, midsize farmers are having the infrastructure for them to drop produce off and us to deliver it and to be able to pay them a real return on what they're growing. It's difficult for these farmers to compete with the huge farms in California.

So how do you pay farmers a real return?

We let them set the price. By being a nonprofit and not trying to make any money other than [to cover] our operating costs, GrowNYC is able to even the playing field.

How do you get fresh, local food to underserved New Yorkers?

We worked with the Department of Health to create Healthy Bucks, a food stamp incentive program that has become a national model. Through our programs, like Youthmarket, we can distribute in areas that haven't been traditionally served. The same kale that is going into Gramercy Tavern is at a farm stand run by teens in Brownsville, Brooklyn, on the same day.

Is the obsession with farm-to-table more than a trend?

It's the last frontier for environmentalism. We spend millions of dollars protecting the watershed around New York City and building the infrastructure to keep water clean and safe and deliver it to everyone at a reasonable price. We spend a lot of time regulating the air. But food is something we've left to private industry.

Is there enough local food to serve restaurants that say their food is local?

Consumers have to be skeptical and ask. We need to make sure that people are living up to their promises. With more local wholesale, the issue of "faux-cal" may disappear because there's access to that product on a consistent basis.

What does the White House's environmental position mean for the city?

Cities have been the innovators in fighting global climate change. As a citywide organization, we provide an outlet to create change in communities even if they can't get it on a federal level. You're not going to be worried about Trump's tweets while you're shopping in a Greenmarket. Hopefully, you're thinking good thoughts.

Van Ooyen wants to serve local and midsize farmers in the state

Mother Nature Gives Indoor Farms A Boost

Mother Nature Gives Indoor Farms A Boost

By Tom Karst March 14, 2017 | 10:00 am EDT

Tom Karst, national editor

There are times that Mother Nature is just too darn unpredictable.

When everything goes without a hitch, the U.S. typically has an abundant supply of vegetables. But throw in rainy weather, delays that move back planting and harvesting, and all of a sudden you have a case of panicky buyers who are keen to look for more predictable and nearby sources of supply.

Retailers and consumers in the United Kingdom in February suffered a shock when rains in Spain caused some stores to ration their supply of greens. Some California companies saw an opportunity and shipped lettuce to the U.K.

Now it’s California facing rain-related production problems. The Packer has covered the gaps in vegetable supply in California, and various marketers predict it will get worse before it gets better. The rains that brought relief to the Golden State could give buyers a roller coaster ride later this spring.

In the context of these issues, we are reminded of the conviction that one region’s disaster is an opportunity for someone else.

The Packer’s Ashley Nickle covers the issue this week in a story that reports indoor farms are seeing increased demand as weather-related production issues in Arizona and California have affected the supply of leafy greens.

Nickle reports New York, N.Y.-based BrightFarms, which has greenhouses in Illinois, Virginia and Pennsylvania, has seen retail orders rise in recent weeks.

Likewise, Buffalo, Mich.-based Green Spirit Farms and Portage, Ind.-based Green Sense Farms reported a jump in interest because of supply glitches in the West.

The latest supply disruption helps make the case for indoor farming operations.

The rains that brought relief to the Golden State could give buyers a roller coaster ride later this spring.

I recently visited with Paul Lightfoot, CEO of BrightFarms about this issue. He said leafy greens buyers are looking for locally sourced and stable leafy greens supply for a number of reasons, including supply disruptions caused by rain and mildew, the pull of overseas demand on U.S. product and even worries about the potential shortage of labor in growing regions.

Supply chain disruptions, combined with what Lightfoot believes is a consumer-led transition from “long distance” to local supply of food makes him optimistic about the future.

BrightFarms secured $30 million in financing last fall that he said will allow the company to expand into about 14 markets over the next four years, growing from three facilities now to 17 facilities in five years. On the immediate horizon is a project in Ohio, he said, followed in short order by a facility in Kansas City.

“We really view that (financing) as our opportunity to build a national platform, to build out in every major market in the Midwest and the Northeast,” he said.

After building out production facilities over several years, Lightfoot said the company may considering expanding commodities offered beyond the current lineup of leafy greens and selected tomato varieties, perhaps to include cucumbers, peppers and even strawberries.

Even if BrightFarms does have a “tiger by the tail,” as Lightfoot says, it is hard to say how much the local indoor farm trend will play out over the next decade.

For now, unpredictable Mother Nature is giving BrightFarms and similar farms an assist.

Tom Karst is The Packer’s national editor. E-mail him at tkarst@farmjournal.com.tkarst@farmjournal.com

Cuba In Your Backyard: The Indian Startup Bringing Organic Farming to Your Rooftop

Cuba in your backyard: The Indian startup bringing organic farming to your rooftop

Homecrop gives you everything you need to make your own small farm at home.

- Shilpa S Ranipeta

- Tuesday, March 14, 2017 - 19:47

Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba was heavily dependent on the USSR for petroleum, fertilizers, pesticides and farm products. But when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, and eventually sanctions were imposed on Cuba, the country was left in the lurch. According to cubahistory.org, the country lost nearly 80% of its imports and exports and the GDP plummeted by 34%.

The effects were seen almost immediately. There was acute food shortage. Calorie intake fell to less than half of what it was before. In such a situation, Cubans had no choice but to grow food themselves. Tiny pockets of land emerged all across the country. What started as a concept called Organoponicos is now being replicated around the world as a sustainable urban farming solution.

It’s as simple as converting your terrace, backyard or balcony into a small farm. And at a time when almost every fruit and vegetable being grown is sprayed with pesticides, what if you could control what goes into growing your food? This is where 26-year old Manvitha Reddy stepped in to start Homecrop – a startup that helps you grow pesticide-free vegetables at home. Reddy has designed rooftop and backyard kits that have everything you need to make your own farm at home.

The main technique used here is square foot gardening. In areas as small as 15 square feet, Homecrop gives you a kit that includes a high intensity polystyrene trough, a leak proof support structure for trellis, a shade net, a mat for drainage, garden tools, natural growth enrichers and service from the Homecrop team.

Simple farming techniques used since ancient times are incorporated into building a home farm. For example, all of Homecrop’s farms are soil-free. Instead, Coco peat is used. This does not require much depth and it lets roots take in more nutrients and gives them more aeration. The crops are irrigated using an age-old irrigation method called Olla’s where water is filled in clay pots, which are porous enough to let water seep through. This reduces the use of water by 60-70% letting you water the plant just once in every 2-3 days. Most importantly, rooftop gardens bring down a house’s temperature by a few degrees.

Reddy launched Homecrop in January this year with an initial investment of just 5 lakh rupees. Ideation took a year under the guidance of National Academy of Agricultural Research Management (NAARM)’s incubator a-IDEA. The incubator helped her research various agricultural methods for her idea and provided her with access to vendors for the kit.

She started by catering to households and is now targeting gated communities. “There is so much unused space in a house or a gated community. The idea is to use whatever available space there is, to make edible landscapes,” Reddy says.

Homecrop currently offers two kits – the budget kit, which can be used for backyards at a cost of Rs 7500 and the premium kit, which can be used for rooftops at a cost of Rs 15,000. With operations currently only in Hyderabad, Homecrop has so far covered 400 square feet.

Once it completes 300 installations, Homecrop will look at raising additional funds.

Homecrop is now working with NAARM to standardise the process. It is also coming up with kits for balconies in a month and a half. This will be a vertical self-watering tower on which one can grow up to 18 plants in an area as less as two square feet. Post this, Homecrop will launch do-it-yourself kits and expand operations nationally.

And if all of Homecrop’s efforts bear fruits, or vegetables, it hopes to break even in the next one year

New Technologies Are Creating New Ways To Grow Fresh Produce

New Technologies Are Creating New Ways To Grow Fresh Produce

Vertical farming operations are popping up everywhere and this new technology can complement traditional agriculture

AF Columnist

Published: March 13, 2017

Opinion

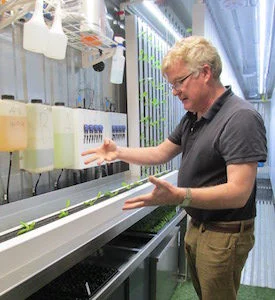

We were in Holland and our group stood in amazement at the growing capabilities of Koppert Cress.

Owner Rob Baan, a policeman’s son turned world entrepreneur, was emphatic that neither soil nor light is needed to grow food — only heat. And all of those components could be provided by technology, he said.

In a large glasshouse Baan grew microgreens in cellulose under LED lights. In the vast kitchen on site, we tasted the bounty and I remember it still: an absolute bursting of flavour and texture exploding on the palate.

The Business Plan Was Simple.

Take the product to the chef first, ask them what they liked, disliked, and were looking for in food trends. Go home, turn on some LED lights, and grow what the chef wants. Baan’s global empire (Koppert Cress distributes microgreens across Europe and has a U.S. division) is proof that fresh food can be grown inside. It is the ultimate urban farm.

Later, in a cooking class in Canada, I noted that chefs had microgreen boxes or microgreen appliances in the kitchen. Again, no natural light and no soil were present, and the greens were grown in stacked trays. But it made a huge difference to a dish when that fresh green top was pruned off the tray from the inside of that black box. A variety of these are now available for home kitchens. Retail stores in the U.K. introduced living vegetable aisles where the food was grown on site and the customer picked it from the vertical display.

And in travel, I’ve found hotels now boast rooftop gardens and restaurants are quick to highlight their little herb patch. That’s good news because it means we have a movement to grow food that has been unmatched in recent history. How far we go is really limited only by imagination. We can grow food in a field or black box, and both will metabolize similarly.

European scientists have long been curious about food produced in a black box. Their quest for perfection demands vegetables and fruit be fresh and without blemish. Not only must the shape and colour be right, but so must the degree of ripeness. Just as the Chinese form the square watermelon in a box, growing food in black boxes allows for the perfect product every time.

Why is This So Important To Traditional Farmers? And Why is it a Threat?

While it is true that farming is truly evolving on many technical platforms, the idea of food production indoors and without soil or light is leaping ahead in the area of vegetable and biomedical production. The yield is 20 to 30 times that of a conventional field, variety dependent, and the crop is not under weather distress as the environment can be remotely controlled. Lufa Farms, headquartered in Montreal, started the rooftop movement now popular around the world. But it was Vancouver that got folks thinking about filling the space on every floor with food all the way to the roof. Canada started thinking about going vertical.

As cities develop, food policies and municipalities enacted bylaws restricting chemical usage, the natural progression has been to move farms in and up. Touring the Delta area of British Columbia and the Golden Horseshoe in Ontario are jaw-dropping farming experiences. The agricultural output is staggering.

Vertical farming goes a little further and takes those huge flat areas often seen in greenhouses and tiers them with suspending boxes that grow food, particularly leafy greens. These products are often organic, or at least chemical free, saving that production cost while responding to consumer demand.

Some of the designs I researched took advantage of the moderate climate and were glass structures that allowed for natural light. None used soil and either had a growing medium or were hydroponic. A new structure in Canada based out of Truro, Nova Scotia is a closed system based on LED lighting that was built on the premise of food that is nutrient dense, fresh to use in the culinary world, and the structure itself can be built almost anywhere.

One of the challenges in this vast nation is the development of a delivery system that can get perishable, nutrient-dense foods to rural and remote communities. Vertical farming offers a solution to these issues — and creates jobs for the local people, attracts local distributors, and makes good food affordable.

A sack of seed could feed a village and that is an important consideration as we move forward in food policy. Another area of interest for me is the biomedical component as it complements natural health and there is an assurance of purity that we cannot confirm from imported product.

Vertical farming does not threaten agriculture, but it does change it. New technologies will continue to enhance farms in Canada, secure food in urban spaces, and allow our nation to be a world leader in terms of technology and health.

From Shipping Container Farm, Casper, Wyo. Pastor and Hydroponic Lettuce Grower Preaches Local

From Shipping Container Farm, Casper, Wyo. Pastor and Hydroponic Lettuce Grower Preaches Local

March 13, 2017 | Trish Popovitch

Matt Powell opens the door to his hydroponic lettuce farm, housed in a used refrigerated storage container on the corner of his Casper, Wyoming property, and the Marriage of Figaro fills the air.

“My little Mp3 there is loaded up with Mozart and Bach. The study I heard said they tested growing plants in three sound proof environments. They had classical in one, death metal in another and silence in a third. Classical did the best, death metal did the second best,” laughs Powell explaining how his fresh hyperlocal greens are grown with the aid of some classic tunes as they stay cool in their farm-in-a-box environment.

The enclosed vertical farm, Skyline Gardens, came with the hydroponics already in place from Boston-based Freight Farms. This made it a little easier for Pastor Matt Powell, former computer salesman and current professional theologian, to find his way to a sustainable side business in an area in need of sustainable businesses. Using filtered water, nutrients, red and blue grow lights and of course, classical music, Powell will produce, at capacity, approximately 500 heads of fresh greens for the people of Casper every week. Business is growing steadily and a few harvests have already occurred.

Each variety of lettuce, Swiss chard and culinary herbs grows in isolation in one of the easy to remove and handle vertical growing towers. Powell labels the towers with dry erase marker to keep track of varieties, planting time and harvest requirements. As Powell explains, shipping container farms are ideally suited to the short growing season and temperamental weather of the Equality State. “It’s an enterprise that’s really custom suited to this area and just the lifestyle around here. People have land and it’s fairly easy to put one of these boxes down,” says Powell.

The company is still in its infancy with just six months under its belt. Most of that time was spent training in hydroponics, learning the equipment and realizing the substantial amount of legwork and marketing even the most tasty lettuce line needs to grow. “There is the barrier to entry: it’s expensive. And it’s definitely a learning curve,” says Powell. “You’ve got to be a problem solver and you got to be flexible and willing to learn. There’s a lot to learn on the farming end of it and there’s a lot to learn on the marketing end of it.”

Freight Farms uses discarded and retired refrigerated storage containers to build their hydro farms. Powell’s was the first one they sent to Wyoming so they had to add a wind barrier to the outside of the fan so it wouldn’t be pulled off or damaged by the high winds. The container ships out of Boston but the ZipGrow vertical hydroponic towers inside come from the folks at Bright Agrotech in Laramie, another indoor agriculture-focused Wyoming company.

Skyline Gardens will produce approximately 500 heads of lettuce per week at capacity.

Skyline is almost at profit level on the month to month books, but Powell predicts three years at this rate of growth to pay startup costs back in full. Self-funded, Powell realizes the wariness of banks, especially in a place like Wyoming where sustainable agriculture is still finding its feet, to fund container farms and similar new social enterprise style businesses.

Powell’s background in sales has certainly aided him in selling the idea of hyperlocal lettuce to Casper’s farmers’ market attendees as well as a few area restaurants. Although some early leads grew cold due to, in Powell’s assessment, the difference in price between his product and other wholesalers. “A lot of them want me to meet the price points of [their current suppliers] but I always say it’s a whole different product. When you have to deal with corporate offices out of state…that always makes it harder, so I’m working on that. I mean direct sales has a lot to be said for it. I get the whole profit to myself. I can control the way and time that I sell it.”

Powell has several direct sales customers who buy CSA style as well as his wholesale contracts. He also sells through a local aggregation group, Fresh Foods Wyoming, which takes his produce to the farmers market for him. Deliveries have proven the most time consuming aspect of the business so far and for now Powell wants to concentrate on solidifying his customer base with no plans to expand.

“Right now I think this is enough for me. I have my main job and I’m not planning on leaving that any time soon. Even now, in the startup phase, the time commitment is substantial,” says Powell.

As the ‘grow local’ and ‘sustainable’ concepts continue to build traction in Wyoming, Powell says he’s not worried about a crowded market just yet. “I’m not too worried about competition,” says Powell as he explains how his one container farm could supply a single local restaurant completely and exclusively. “There’s plenty of room in town for competition.”

Pastor Matt Powell, the owner of Casper, Wyo.-based Skyline Gardens. Photo courtesy of Skyline Gardens

Newbean Capital and Local Roots Jointly Authored A White Paper Entitled ‘Indoor Crop Production

Newbean Capital and Local Roots jointly authored a white paper entitled ‘Indoor Crop Production: Feeding the Future’ which can be downloaded in full below by entering your name and email address. The paper was launched at the 3rd Indoor Ag-Con on March 31, 2015

Livewell Northwest Colorado: Bring Growing Back Home

Livewell Northwest Colorado: Bring Growing Back Home

Andy Kennedy/For Steamboat Today

Saturday, March 11, 2017

In a TEDx Mile High Talk, former three-time Olympian and health expert Jeff Olson described the call of duty during World War II, when Americans bonded together to grow more than 40 percent of the country’s fruits and vegetables in victory gardens. The premise was that larger agriculture ventures could go toward feeding our troops overseas.

But, when the war was over, the gardens withered, and during the next two decades, when the American family working-dynamic began to shift, there was another more toward agricultural imperialism. This imperialism birthed a larger global agriculture, as the U.S. government emphasized to its small farmers to “get big or get out,” for high-production and low-margin growing.

Olson warned that modern “industrialized food is a tragedy of human health, an irony of ecology and a paradox of economics.”

Olson elaborated that the solution to this terrible trifecta is the future of “closed-environment agriculture,” or greenhouses with a vertical twist.

Pioneered by the Dutch and now adopted by most industrialized nations — including 2.8 million acres of greenhouses in China — greenhouse growing is, indeed, feeding the world, and sadly, the U.S. is dead last in this effort. We used to be a net exporter of fruits and vegetables, and we are now a net importer of produce.

While greenhouses can be a viable solution, a better solution could be indoor vertical growing — a marriage of Jetson-like food technology with design wizardry of Steve Jobs.

We stand at the convergence of humanities and technology, and vertical aeroponics serves as nature with aerodynamic design. Imagine 43,000 square feet — about an acre — of your favorite greens. Vertical aeroponics can do it in 4,000 square feet. That’s 90 percent less space, with 90 percent less water, giving three times the nutrient density in the plant. Used by NASA and studied by universities around the world, vertical growing has proven efficient time and again.

I recently traveled to Florida to see the start of this revolution at Living Towers Farm, just north of Orlando. For more than six years, Jan Young’s organization has been growing “beyond organic” food for those in need, teaching the techniques of vertical growing to students and in-home gardeners and selling quality food that “doesn’t have to cost the Earth or have a negative impact on it.”

Even though Florida has the weather for outdoor gardening, it does not have the soil for it. Growing vertically yields more and healthier plants. Young’s eggplants, for instance, yield 8 to 10 fruits on a regular basis — about 30 percent more yield than traditional gardening.

Seeing the vision of Living Towers in person and pondering the economics of vertical growing spins my imagination to what this could mean for a local economy. For example, an acre of commodity corn earns a farmer $1,200; an acre of traditionally grown, organic food earns $12,000; and an acre of vertical aeroponics earns a quarter of a million dollars in revenue for one harvest, according to Olson.

Bringing the concept of Victory Gardens full circle, Olson has teamed up with an organization called Veterans to Farmers, which turns protectors into providers with an urban agricultural training program, creating “agropreneurs.” One of the program’s graduates launched the first vertical growing farm on the Front Range that sold out within a year of production, selling produce to fine dining restaurants on the Front Range.

“People are hungry for beautiful food,” Olson said.

Despite being known as an agricultural state, 97 percent of Colorado’s leafy greens are imported from thousands of miles away. With only a 25 percent increase in Colorado-grown food shift, we’d see 31,000 new jobs, generating more than $1 billion in new wages.

In my own home, we have two commercialized, state-of-the-art vertical growing systems, as do many other friends and peers in town — the Tower Garden has been around six years and is fairly well-known by now as an in-home solution to one of the shortest growing seasons on the planet.

However, it’s the larger installations that now inspire me. The vertical farms popping up around the country are something I would like to emulate. For several years, I have been inspired by the O’Hare Airport installation — more than 100 vertical towers in terminal D that outgrew their mission to feed the restaurants so quickly, they now offer a farmers market for travelers, as well.

I have brought this inspiration to several local nonprofits to start working on a project I hope will soon be growing local food on a larger scale, both for families in need and for those who want fresh produce. For more information, contact Andy Kennedy at andyjkennedy@gmail.com.

To view Jeff Olson’s full TEDx Talk, visit youtube/ttvIeugcigk.

Andy Kennedy a member of the Northwest Colorado Food Coalition

Urban Farming Insider: Understanding Organic Hydroponics With Tinia Pina

Tinia Pina is the founder and CEO of Renuble, a company started in 2011 that develops hydroponic fertilizer 100% derived from organic food waste inputs.

Renuble helps hydroponic growers increase yields with a wide variety of urban farming crops grown hydroponically in large metropolitan areas like New York City, where Renuble is based.

Urban Farming Insider: Understanding Organic Hydroponics With Tinia Pina

Tinia Pina is the founder and CEO of Renuble, a company started in 2011 that develops hydroponic fertilizer 100% derived from organic food waste inputs.

Renuble helps hydroponic growers increase yields with a wide variety of urban farming crops grown hydroponically in large metropolitan areas like New York City, where Renuble is based.

We interviewed Tinia to discuss:

- the basics of organic hydroponic fertilizer for beginning urban farmers

- some brand names she hears often for lighting, growing medium, common urban farming products

- and more!

___

Introduction

UV: Can you start off by talking about Re-Nuble and how it started? What's your mission?

Tinia: I founded Re-Nuble in 2011, the whole premise behind that was to try to increase access to more nutritious options, primarily in cities, because I saw that's were the trend was as far as macroeconomics of people migrating towards (cities).

So, how can we make food, especially nutrient dense food, more affordable, and by doing that, making use of the abundant food waste in New York City and more efficiently serve the needs of food production.

My vision to achieve that was re-purpose or up-cycle the reclaimed nutrients from food waste and at the time New York City was spending 33 million dollars (per year) to export its food waste.

We thought that by manufacturing value added, organic liquid fertilizers, primarily within the hydroponic industry, because there was definitely, and still is, a demand to grow with organic inputs, it is challenging... but we've proven that you can achieve comparable grow results.

Granted, the nutrient management side still takes a bit of a learning curve to adopt, before (using this type of fertilizer is really seamless.

So the goal is to indirectly increase food production in cities so that we can cover the crisis of food with more supply.

UV: You mentioned the learning curve for hydroponics, can you talk about what that entails? Obviously, with the company being around since 2011, you have a really good perspective on how hydroponics have been trending in the urban farming setting since then. What's your perspective on that?

Tinia: We started in 2011 with a different business model, we pivoted into hydroponics because the problem was more prevalent with using organic fertilizer and meeting that demand, (the pivot was) only as of 2015.

The challenge with organics or anything that's biologically derived is because it's so natural, you can't have the precision that you have with a synthetic fertilizer where it's already in its ionic form and readily available to the plant.

(With synthetic fertilizer), you know exactly to the parts per million what ionic nitrogen or phosphate or mineral is available to the plant.

With biologicals, a lot of the decomposed matter, for example, in ours, we have organic certified produce waste, that decomposed matter still goes through a degradation when it is subjected to a hydroponic reservoir (unlike synthetic fertilizer).

So (biological fertilizer) is still decomposing when you're in a hydroponic reservoir, and that lessens the ability to have precision and know exactly how much your pH or EC will be, especially within the first 1 or 2 weeks of growing, and that tends to stabilize after that.

UV: When you say "the first 1 to 2 weeks" what is that 1-2 weeks referring to? Is it to after application of the fertilizer?

Tinia: When the fertilizer is bottled, we're guaranteeing, a six month shelf life, so it is pH stable (pre application), and then when you dilute it in your hydroponic reservoir, it does go through a natural decomposition because the microbes are active again, so to answer your question, the pH and EC swing after application into the hydroponic solution due to microbe activity, so you're unable to say "you can expect with certainty a pH of 6.5 within the first 2 weeks simply because biological fertilizer has to normalize.

We've shown historically, it's at that two week mark, that your EC swings, anywhere from .8 to 3, then tends to normalize, and that's only for hydroponic reservoirs.

In soil, because you have the soil and you have a medium that diffuses, the microbes act differently in the soil medium, just like they would in rockwool or similarly in coco coir. How the organic fertilizers act in those substrates has less effect on your EC and your pH.

UV: You touched on a ballpark EC range, what is a range for pH (for hydroponic mediums)? Does it depend on the crops you're growing?

Tinia: So what we do with our product line, we have an Away We Grow, which is a grow formula, True Bloom, for flowering, and fruiting crop formula, and a supplement which does really well with microgreens but it's a supplement at the end of the day.

So we advise (pH level in hydroponics) on a benchmark. With biologicals (fertilizers) you aren't able read EC technically because there are no mineral salts, but we show based on our own trials that EC of 1.8 for butterhead leafy lettuce for example, it will be optimal to maintain that EC for the 4 or 5 week duration that you're actually cultivating it for.

Then we prescribe a pH range (only) if you were using synthetics.

UV: To clarify, the reason why you can generate this data on EC and others can't is because your essentially doing some type of simulation? Is that a fair way to say how you derive your EC benchmark of 1.8? You essentially said with the EC that you can't technically measure it, then you said is you guys do project it for the edification of the customer. What are you doing that the customer can't do as far as simulating EC?

Tinia: The customer should already be measuring their hydroponic solution for pH and EC, the only big difference is, say (For example), you often have a pH stick that also measures for EC, if you were to subject it to a reservoir that has our nutrients in it (organic fertilizer), it's going to "dial" or measure an EC value, but, there really is no salts that are in the solution, so the (reading) isn't accurate.

So what we do is project the EC so that we can tell you what to look our for, but (at first), there isn't a true measurement because technically there's no salt's in there at the end of the day.

UV: SO this at the end of the day, is a very technical aspect of hydroponic nutrients?

Tinia: Yes. With organics in general, it can be grown just as effective, as far as leaf size and harvest weight, it can take a little more time to get the same harvest weight compared to synthetics, and that's expected because it's a slower uptake process.

But you can grow with organic fertilizer just as you can grow with synthetic fertilizer. This same reason is why Re-Nuble has gotten so much interest - people want to have a more viable alternative to synthetic hydroponic fertilizer, it's the same with food and medicine, it speaks to the same cause (to not rely on synthetics).

UV: For people who are looking at the unit economics, cost and benefit analysis, maybe they're thinking about starting their own urban farming hydroponic operation, what do you look at when you're looking at the cost of say, a biologic fertilizer compared to say, a synthetic one?

When crops are grown and harvested, what do you typically see as the mark-up for the organic hydroponic produce you're typically helping your customers grow?

Tinia: We've seen to date that just organic or natural branded crops tend to command a ~44% pricing premium.

That mainly pertains to metropolitan areas, we've done less testing with rural, traditional farmland areas.

Now, (on the unit cost side), you will notice that with organic hydroponics you will typically need more applied fertilizer than with synthetic fertilizer.

As I mentioned earlier, this is because synthetic fertilizers already provide the nutrients in ionic form, which just means it's readily available for the plant to pick up, whereas with organics, there's still a requirement for the plant to convert (the organic waste based fertilizer) into a form that can be picked up.

So what that essentially means is that you will need more organic fertilizer to get to the same needed concentration, compared to synthetic fertilizer.

I typically estimate you will need 20% more of the organic fertilizer than with synthetics, but if you're selling the (organic) urban farmed produce, and you can sell it higher, it's typically worth the cost!

UV: So you're applying 20% more, on a unit basis does organic hydroponic fertilizer cost the same amount as synthetic hydroponic fertilizer? How does it compare?

Tinia: It depends on the production scale, the water, the temperature. It does become technical to answer that question because all of these variables, water, temperature, the crop type sometimes, the moisture, the air in the actual grow space, can slightly increase or slightly decrease the nutrient consumption.

So I can't give a (generalized) baseline for unit cost unfortunately.

UV: Another thing I get asked about is, especially for setting up a hydroponic system, is regarding the most commonly used / popular brands, I'm not asking you to talk as much about the fertilizer but when you're interacting with customers, what are some of the common names you see them using for the actual hydroponic system, for the tanks, for lighting, what are some of the popular names that you're hearing about more often?

Tinia: What I'm hearing from people, anywhere in between New York City, Florida, DC, and a couple people on the west coast, for lighting I've heard Lumigrow. They tend to be a popular brand on the commercial side as well as hobbyists.

For the organic base (hydroponic nutrient fertilizer / "grow formula"), depending on what you're growing, people have said Pure Blend, which is part of Botanicare, that's a brand that we directly compete with, and we've shown better yields for some crops for Botanicare, the main differentiation between Runuble and Botanicare is that Renuble has 100% organic certified inputs whereas they say they have an organic base but they do incorporate synthetics into their (fertilizer) formulation.

On the medium side, I hear Growdan (rockwool cubes) a lot, with hydroponics, surprisingly users taking a blend of perlite and mixing it with cocoa coir, kind of a hybrid set up, on the soil side, what's been popular is Batch 64, depending on what your growing, they have Batch 64 and then Waste Farmers.

The reason why I'm speaking (about) these brands is because they (the brands above) are for people interested in sustainable grows, and those that have more of an organic alignment.

UV: I like to finish up with some rapid fire questions. What's a company in the urban farming space that your excited about / that you think is onto something, that you've been following, maybe a CEO that you've been following in the space?

Tinia: One is called Farm.One. Instead of the retrofitted shipping containers they take microfarms and they provide specialized growing services but focusing on really exotic herbs. So they're really taking an angle of (growing for) culinary art to a whole other level and not just producing your typical commodity crop.

UV: The next question would be what's your favorite fruit or vegetable?

Tinia: Strawberries.

UV: What's your favorite book relating to urban farming? I know that's specific and there may not be that many books, so if you don't have an idea for that what's one of your favorite books in general, one that is most gifted or that you most recommend.

Tinia: I have quite a few! There are books on my bookshelf that I haven't even read yet but I'm wanting to. But answer your question, "The Vertical Farm", by Dickson Despommier, which is cliche now.

UV: The last question is, what's something you disagree with or think there's a misconception about in the urban farming industry or hydroponic industry that is generally accepted as being true?

Tinia: It's less of the hydroponic industry but more of the agricultural industry in general, but I'm not sure if you know, but this April 17th, anything hydroponically or aquaponically grown that wants to obtain organic certification is being voted as to whether it can obtain that certification.

So the contention that I want to bring up is that hydroponics and aquaponics, anything in the controlled environment industry, can be successfully synergistic with conventional ag. I think right now, because there is a market, it does impact a lot of people's bottom line. If they open up the organic certification process, I think a lot of people think they have to be competitive and contentious but they can very much complement each other (conventionally organic grown produce vs controlled environment organic agriculture) very much.

Thanks Tinia!

Indoor Ag-Con Returns to Las Vegas to Discuss Farm Economics and New Technology Trends in Hydroponics, Aquaponics & Aeroponics

Indoor Ag-Con Returns to Las Vegas to Discuss Farm Economics and New Technology Trends in Hydroponics, Aquaponics & Aeroponics

Indoor Ag-Con – the indoor agriculture industry’s premier conference – will be returning to Las Vegas for the fifth year on May 3-4, 2017 to discuss the prospects for this increasingly important contributor to the global food supply chain.

LAS VEGAS, NV (PRWEB) MARCH 10, 2017

Indoor agriculture – growing crops using hydroponic, aquaponic and aeroponic techniques – has become popular as consumer demand for “local food” leads growers to add new farms in industrial and suburban areas across the country. Indoor Ag-Con – the industry’s premier conference – will be returning to Las Vegas for the fifth year on May 3-4, 2017 to discuss the prospects for this increasingly important contributor to the global food supply chain.

The two-day event will be held at the Las Vegas Convention Center, and is tailored toward corporate executives from the technology, investment, vertical farming, greenhouse growing, and food and beverage industries, along with hydroponic, aquaponic and aeroponic startups and urban farmers. It is unique in being crop-agnostic, covering crops from leafy greens and mushrooms to alternate proteins and legal cannabis. Participants will receive an exclusive hard copy of the newest edition in a popular white paper series, which is sponsored by Urban Crops and will focus on the US industry’s development.

The event will consist of keynotes from industry leaders and extended networking breaks, along with a 50+ booth exhibition hall. This already includes industry majors such as Certhon, Dosatron, DRAMM, Hort Americas, Philips Lighting, Priva, and Transcend Lighting. A new addition for 2017 is “lunch and learn” sessions covering practical topics such as health and safety. Confirmed speakers include executives from Argus Controls, Autogrow, Bright Agrotech, CropKing, Fresh Box Farms, Grobo, Intravision, Plenty, Priva, Shenandoah Farms and Village Farms among many others. “We’re expecting that the big themes for this year will be farm economics and the commercialization of newer technologies such as machine learning, and are excited to have gathered experts from across the world to speak. The entrepreneurs in our funding session have raised more than $50mn for their indoor farms in the past year alone, and one speaker is operating a 100k ft2 commercial controlled environment farm” commented Nicola Kerslake, founder of Newbean Capital, the event’s host.

Agriculture technology companies, suppliers and automation companies will have the chance to meet and mingle with leading vertical farmers and commercial greenhouse operators at a drinks party on the first evening of the event. Event sponsors include Autogrow, Urban Crops, Kennett Township, Freight Farms, Grodan, Joe Produce, Crop One Holdings and Grobo.

Beginning farmers, chefs and entrepreneurs can apply for passes to the event through the Nextbean program, which awards a limited number of complimentary passes to those who have been industry participants for less than two years. Applications are open through March 31, 2017 at Indoor Ag-Con’s website. The program is supported by Newbean Capital, the host of Indoor Ag-Con, and by Kennett Township, a leading indoor agriculture hub that produces half of the US’s mushrooms.

Indoor Ag-Con has also hosted events in Singapore, SG and New York, NY in the past year, and will host its first event in Dubai – in partnership with greenhouse major Pegasus Agriculture – in November 2017. Since it was founded in 2013, Indoor Ag-Con has captured an international audience and attracted some of the top names in the business. Events have welcomed nearly 2,000 participants from more than 20 countries.

Newbean Capital, the host of the conference, is a registered investment advisor; some of its clients or potential clients may participate in the conference. The Company is ably assisted in the event’s production by Rachelle Razon, Sarah Smith and Michael Nelson of Origin Event Planning, and by Michele Premone of Brede Allied.

5th Annual Indoor Ag-Con

Date – May 3-4, 2017

Place – South Hall, Las Vegas Convention Center, Las Vegas, NV

Exhibition Booths – available from $1,499 at indoor.ag

Registration – available from $399 at indoor.ag

Features – Two-day seminar, an exhibition hall, and after-party

For more information, please visit http://www.indoor.ag/lasvegas or call 775.623.7116

Are Indoor Farms The Next Step In The Evolution of Agriculture?

You’ve probably heard of farm-to-table, or even farm-to-fork, agricultural movements that emphasize the connection between producers and consumers. But what about factory farm-to-table?

Are Indoor Farms The Next Step In The Evolution of Agriculture?

SPECIAL TO THE JAPAN TIMES

MAR 10, 2017

You’ve probably heard of farm-to-table, or even farm-to-fork, agricultural movements that emphasize the connection between producers and consumers. But what about factory farm-to-table?

Spread, a giant factory farm that grows lettuce in Kameoka, Kyoto Prefecture, is just one of more than 200 “plant factories” in Japan capable of harvesting 20,000 heads of lettuce every day. Their lettuce, which includes frilly and pleated varieties, is grown in a totally sterile environment: There’s no soil or sunlight, no wind nor rain.

The rich, dark-brown soil in which produce has traditionally been grown is utterly alien inside the factory. Instead, the lettuce is grown hydroponically, in a nutrient-rich gelatinous substance. The vegetables grow in vertically stacked trays under LED lights timed to come on during the day and switch off at night.

The lettuce Spread grows in Kameoka — which takes about 40 days from planting to harvest — is packed into bags and shipped to over 2,000 supermarkets across the country. The product also makes it into airline meals, although the company wouldn’t reveal which ones.

At a time when Asian countries are scrambling to deal with the surges and declines in population as well as the effects of climate change, factory farming is a burgeoning business. In Japan, for example, the number of farmers has dropped from a high of over 7 million in the 1970s to under 2 million, and today the average age of Japanese farmers is 67.

Spread, however, is about as far from the pastoral image of a vegetable farm you can imagine. While the facility, and even the concept, sounds futuristic, Spread has been growing lettuce in these conditions since 2006 at its Kameoka base.

This year, it will open another plant factory at Kansai Science City, on the borders of Kyoto, Nara and Osaka prefectures. Between the two factories the company will be able to produce 50,000 heads of lettuce each day.

What makes the new facility different is the level of automation: tasks such as raising seedlings, replanting and harvesting will be done by machines and guided by artificial intelligence, a move that will cut labor costs by 50 percent and boost profitability. In 2016, Spread was awarded a gold medal at the Edison Awards in recognition of its role in agricultural innovation.

On a recent tour of Spread’s facility in Kameoka participants viewed the lettuce through an observation window, while factory manager Naohiro Oiwa communicated via telephone with a worker dressed head to toe in white protective clothing. “When our products first appeared in supermarkets, plant factory-grown vegetables weren’t yet recognized by many people. Our sales staff had a very hard time selling them to retail stores,” Oiwa said.

People wanted to know if vegetables grown without sunlight are safe to eat, he added. Spread has since assuaged some of those anxieties by emphasizing the safety of its growing environment and the quality of its crops.

It also helps that Spread can compete on cost: a bag of its lettuce sells for ¥198, a price the firm can maintain. Field-grown lettuce, by contrast, is subject to the vagaries of the weather, and therefore to fluctuations in price.

So-called vertical farms, such as Spread’s facility in Kameoka, are also able to use water in an extremely efficient way. The company would not disclose, however, how much it spends on something that is essentially free to conventional farmers, sunlight, or, in Spread’s case, LED lighting.

Spread spokeswoman Minako Ando said that the firm’s operations received a boost in the aftermath of the nuclear disaster in Fukushima Prefecture following the Great East Japan Earthquake, which struck six years ago today. Amid widespread fears that traditionally grown produce could contain radioactive fallout, factory farming, which is mostly done indoors, suddenly looked like a safer option.

It’s important to remember that, while Spread is at the vanguard of technological developments in farming, the history of agriculture has always been characterized by innovation in its tools.

Spread doesn’t see its role as replacing farmers; it seeks to complement and support the agricultural industry as a whole, Oiwa said.

Along the way to profitability — Spread started operating in the black in 2013 — it has developed several patents and is now in talks with partners around the world to set up similar ventures.

With the know-how it has gathered from growing lettuce, Oiwa said, Spread could start mass-producing other vegetables, such as tomatoes, in giant plant factories in the years to come.

Michael Blodgett, an organic kale farmer in Wazuka, a picturesque tea-producing town in southern Kyoto Prefecture, echoes the notion that, when it comes to farming, innovation is nothing new. “From that viewpoint, new and sustainable techniques for growing healthy vegetables are certainly welcome,” Blodgett said.

He noted, however, that the type of farming he and his neighbors practice engenders a sense of community. Advice is solicited from older farmers, and at harvest time neighbors share what they bring in from the fields.

“There is something special about planting seeds in the ground, taking care of the plants by weeding, watering, and love,” Blodgett added.

In the near future it will increasingly be the charge of robots and AI systems to plant, weed, water and harvest the food that ends up on our table. Where exactly that leaves the farmers, or the land itself, remains to be seen.

Food factory: At Spread's facility in Kameoka, Kyoto Prefecture, lettuce is grown hydroponically using timed doses of LED light. | J.J. O'DONOGHUE

The Farm of The Future? (Video)

The Farm of The Future? (Video)

AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY

WASHINGTON, Feb. 28, 2017 -- There's a new trend in agriculture called vertical farming. As humans learned to farm, we arranged plants outside in horizontal fields, and invented irrigation and fertilizer to grow bumper crops. But with modern technology and farmers' cleverness, we can now stack those fields vertically, just as we stacked housing to make apartment buildings. Moving plants indoors has many benefits: Plants are not at the mercy of weather, less wilderness is cleared for farmland, and it's easier to control the runoff of fertilizer and pesticides. But the choice of lighting can make or break the cost of a vertical farm and affect how long it might take for urban agriculture to blossom. Watch the latest Reactions video here: https://youtu.be/rEw-VfFkUik.

Growing In Vertical Farms Around The World With Philips LED Systems

Following on from partnering with the Staay Food Group to build Europe’s first large-scale commercial vertical farming specifically supplying retail, city farm project manager for Philips Lighting, Roel Janssen, takes PBUK through the “growing recipes” behind the LED systems and examines the needs of different vertical farming markets around the world

10 March 2017

Growing In Vertical Farms Around The World With Philips LED Systems

Following on from partnering with the Staay Food Group to build Europe’s first large-scale commercial vertical farming specifically supplying retail, city farm project manager for Philips Lighting, Roel Janssen, takes PBUK through the “growing recipes” behind the LED systems and examines the needs of different vertical farming markets around the world.

The outdoor temperature in the remote regions of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada have recently been around the minus 30 degree mark - but inside its high-tech greenhouse herb growers Ecobain Gardens is witnessing dramatic changes in its crops as well as big energy-saving impacts, following the Philips LED system installation.

By upgrading the fluorescent lighting previously used in the facility to LED, Philips Lighting is helping the vertical farming pioneer to produce at commercial scale, accelerate growing cycles and grow healthier, more consistent plants, while saving up to CAN $30,000 per year.

From less than 1,400 square feet, the facility produces approximately 18,000 pounds (8,164 kilos) of produce each year through farming methods which use up to 98% less water, no pesticides and now the latest LED technology.

“Saskatoon is really in the middle of nowhere with extremely low temperatures, so for Ecobain CEO Brian Bain, the key was to supply basil and other produce throughout the whole year, even while it was well below zero degrees outside,” Janssen tells PBUK.

“The big advantage now for his operation is year-round supply which is premium quality, has uniformity, looks the same and tastes the same, and has the same nutrient content.

“At Ecobain, growing cycles are now considerably shorter and they are producing commercial scales of produce like basil, where now more than 10,000 plants are produced a week.”

A value-added aspect of Philips LED from a growers point of view is the low heat output which produces a healthier, more consistent plant growth by reducing the heat stress on the plant canopy and root zone as well as providing uniform lighting.

Light Recipes

“When a plant is growing it uses red and blue lights most optimally and if you start trialling LED lights it’s fairly difficult to see what is the best combination of red and blue. We’ve been active in the LED lighting industry for horticulture for the past 9 to 10 years looking at that specific combination of colours that are what we call ‘light recipes’ and they can be optimised for a specific crop or sub-optimised for a range of crops or leafy greens,” adds Janssen.

“If you look specifically at growing without daylight, there are three main advantages for growers; the first is reliability because it's a controlled production cycle so that when everything functions in the right way - the climate, the carbon dioxide, irrigation, the right seeds, the right lighting - it’s always the same production cycle.

“There is no pressure from disease or pests and it’s basically always summer inside. And because you grow in a controlled environment it’s always free from pests so you don’t need any pesticides to get rid of the disease compared with outside where you cannot control the environment and are exposed to the risks of disease and pests.”

The second advantage, Janssen, explains is quality; because of the uniformity a controlled environment under LED offers, plants can be optimised for taste, colour and nutrient content with more than 90% less water because its easier to recycle resources when growing indoors.

The Third Plus Point - And It’s A Big One - Is Yield.

“Yields can vary depending on the light levels and the varieties that you use, but for example, in open field production if you talk about head lettuce, you would go to 15 to 20 kilograms per square metre of growing area per year to, in the most advanced high-tech greenhouse, 60 to 65 kilograms. And if you grow without daylight, you could grow above 100 kilograms per square metre per year.

“That’s growing square meters so if you do that in ten layers, you could go for one square metre of floor space and get 1,000 kilograms of production.”

Ecobain Gardens has partnered with Star Produce to distribute its produce throughout Canada to retailers like Loblaws, Federated Co-op, Safeway and Sobeys, as well as other local grocery stores.

The differences in vertical farming around the world

The Ecobain Gardens project is about locally-produced crops being grown year-round in an area not ordinarily associated with growing herbs and microgreens.

Part of Janssen’s job is to travel the world investigating the specific growing recipes for a myriad of vertical farming growers who want to tap into the potential of LED. He’s the man behind the Eindhoven-based GrowWise Research Centre facility - where R&D teams work in eight “climate cells” researching how to optimise crops further and streamline light recipes.

Since GrowWise first opened in July 2015, Janssen explains how he has witnessed quite a big shift in the interest from industry.

“At first, there were a lot of entrepreneurs wanting to do something within horticulture. They didn’t necessarily have a horticulture background or sufficient knowledge to build a greenhouse, but they saw indoor controlled environments as a an opportunity and if the technology functions in the way it should do, anyone can be a grower.

“But you still need horticulture knowledge and green fingers because if something in the system doesn’t function, you really need someone who can steer the product in the right way.

“What you see in North America and Canada, which are big markets for us, is that most of the lettuce, leafy greens and salad that is produced comes from California. The produce is in a truck for five days before it reach cities like Chicago and Saskatoon in this case, and it’s not as fresh as if you would harvest it on demand and then straight away give it to the consumer. That’s a big advantage when you’re in a remote area.”

In contrast, the indoor vertical farms of the US and Europe, are known as “plant factories” in China and Japan, where the focus is more about food safety and getting access to fresh produce in massively populated urban areas like Singapore and Tokyo.

“In Asia they typically talk about “plant factories” and like the controlled conditions and the safety aspects. That’s basically the idea; they want to push food safety and accessibility.

“Whereas in the US it's more about being local, in Asia the focus is on food safety and accessibility to food is really important.

“We had a lot of customers in Japan with a lot of operational indoor farms.”

Over the last two years, Philips Lighting has seen increasing interest, not just from growers supplying the market, but from retailers and food processors.

Last month during Fruit Logistica, Philips Lighting and the Staay Food Group announced Europe’s first large-scale vertical farm will be built in Dronten, the Netherlands, to serve supermarkets with fresh-cut lettuce grown using LED horticultural lighting.

The indoor vertical farm will have more than 3,000 squared metres of growing space to produce its pesticide-free lettuce - something that appeals to retailers who need to provide high quality bagged or loose lettuce with zero contamination issues.

“When we first met the owner of Staay he wanted to tap into the possibilities of growing in an indoor farm and we started discussing it. Eventually he decided to build a farm and his key reason was that so he could grow locally in the facility where he also uses his pre-cuts salad.

“The level of MRLs on the leaves is really low which is a big added value for them going forward with stricter rules from retail and of course there are no bugs.

“If we play with our grow recipes, we can also extend the shelf life of lettuce, get more dry matter into the lettuce, get it crispier; it’s exactly the same process as growing outside but it’s controlled so if we know what triggers red colouration in a plant for example, we can use a specific light recipe to trigger that colouration and get a nicer colour or trigger dry matter so the shelf life is extended.”

Once the facility is complete, the Staay Food Group can do everything under one roof; grow, pack, process with very low risk of contamination from the pesticide-free lettuce.

UK Loves “Home-Grown”

Janssen explains, UK-based growers like to market produce as “home-grown”, something that particularly resonates with the British market. But why do vertical farms tend to focus on salad crops, microgreens and herbs?

“In the UK we also see that it’s a real added value to have UK-grown products and there are companies growing other crops apart from lettuce and herbs such as Flavour Fresh which grows tomatoes year round using our LED solutions.

“Typically a leafy green is produced within three to five weeks and cucumbers after a few weeks already started giving fruits. We’re also investigating growing fruiting crops but because of the speed or the short crop cycles, at least at this point in time, the main focus is on leafy greens because they offer the biggest opportunities.

“We managed to grow strawberries in our GrowWise facility, but the difficulty of growing completely without daylight is that it’s better to have fast rotating crops with really high yields that you can improve because the economics around it are much more interesting.”

Taking the case of strawberries, Janssen, explains the challenges associated with growing this kind of fruit.

“If you put the seed into a substrate and the strawberry needs two months before it starts fruiting, during those two months you need to put on your lights and climate system, whereas with lettuce, leafy greens and short cucumbers, they’re really fast in how they rotate.

“We’re not saying that we can feed the masses with this but it is a market where there is added value to be found. In Asia it’s mostly about food safety and availability, in the US it’s mostly about the local movement and pesticide-free production, but in Europe it’s for processed optimisation.

“Growers in Europe are triggered by retail to look into this technology and they are stepping into the business. We expect this to grow when Staay is operational later this year because I think they will set the standard in the level of contamination you can have on a leaf which is very close to zero at that point.”

- See more at: http://www.producebusinessuk.com/insight/insight-stories/2017/03/10/growing-in-vertical-farms-around-the-world-with-philips-led-systems#sthash.s0Y5YKCx.dpuf

Why Large-Scale Indoor Farms Will Be Crucial to Feed Our Fast Growing Cities

Why Large-Scale Indoor Farms Will Be Crucial to Feed Our Fast Growing Cities

SEB EGERTON-READ · MARCH 9, 2017

Technological innovations are enabling a new way of producing food transforming indoor environments into places where fruits and vegetables can be grown without soil, close to the city, with an extremely short supply chain, fully independent of weather fluctuations, while reducing demand on water and chemicals. One of the pioneers of the approach, New Jersey based Bowery, describe it as ‘post-organic’ farming, and momentum is growing behind the idea that a sizeable percentage of some of the fruits and vegetables of the future could be grown using this technique.

On the current path, the world population’s caloric demand will increase by 70%, while crop demand for human consumption and animal feed is expectedl rise by 100%. Meeting these needs with existing agricultural practices will require large areas of additional land, and will increase pressure on the earth’s soil, which has gradually been degraded losing a significant percentage of its nutritional capacity over the last 100-150 years. Meanwhile, the effects of climate change, realised through extreme weather patterns, threaten to negatively impact crop yields and disrupt food supply chains.

Urban agriculture in the form of aquaponics, where fish farming is combined with the growth of vegetables and a self-maintaining system is established has a long history, but the data monitoring and ability to control internal conditions provided by new technologies has enabled the further evolution of hydroponics.

Hydroponic farming involves growing produce in multi-storey warehouses without soil. Seeds are planted in a soil substitute and grown in nutrient-rich water, where water is recirculated, and temperature, salinity and humidity are monitored and controlled to maximise the yield. The method has a number of economic, environmental and social advantages. Here’s a pretty good initial list taken from SystemIQ’s Achieving Growth Within report:

- 90-95% reduction in water demand

- Fertilizer use reduced by 70%

- Use of herbicides and pesticides eliminated

- Food waste at the production stage minimized

- Growing space maximized

- Ability to grow throughout the year

- Shorter supply chain results in lower transport costs and related emissions

Reportedly 100+ times more productive on its land compared against traditional farming, Bowery is one of the most advanced movers in the sector. They’re far from alone, Japan’s Spread declared their initial plant profitable in 2013 and now have plans to open an automated plant that could increase their yield to 51,000 lettuce heads per day, and we’ve previously told the story of AeroFarms, another New Jersey based firm.

It’s also a highly efficient technique in terms of resource use. For example, only 5% of the fertilizer used on large fields is actually consumed by people, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s Growth Withinresearch, the rest of the nutritional value is waste across the value chain.

The new model doesn’t come without criticisms. Growing without soil means that there is little opportunity for regeneration or the development of an ecosystem that ‘feeds itself’, rather the method allows for the development of a large number of linear and separate processes in an ultra-efficient way.

Furthermore, there will always be concerns about the nature of the chemicals needed to grow plants in these conditions, and the types of seeds used. For their part, Bowery take pride in sourcing, “from partners who spend nearly a decade developing the ideal seed, rather than relying on GMOs”. When Circulate asked him about some of the potential trepidations, CEO Irving Fain was quick to highlight that the story of indoor farming is a healthy one, both for crops and people:

“Bowery grows its produce under LED lights that mimic the spectrum of the sun. By monitoring the growing process 24/7 and capturing data at each step, we give our crops exactly what they need and nothing more. Because we control the entire growing process from seed to store, our produce is the purest available – food you can truly feel good about eating”.

For Irving, who is already planning Bowery’s second farm, scale is the next challenge, “we plan to continue to build additional farms, keeping them all close to the point of consumption to deliver products at the height of freshness and flavor, and we hope to serve more cities throughout the country”.

Up front investment costs are a potential barrier, but there’s also an increasingly strong business case associated with indoor farming. Besides the growing number of innovators establishing businesses, SystemIQ’s research estimated that €45 billion of total investment between now and 2025 could create an economic reward across Europe of €50 billion by 2030 with key benefits including the freeing up of land space and reduced reliance upon fertilisers and pesticides.

Pair the potential economic opportunity with the demands expected by a fast-growing global population, and it’s easy to imagine a future where at least part of the food supplied to the world’s largest cities comes from indoor farms located inside the city limits.

West Coast Supply Issues Prompt More Demand At Indoor Farms

West Coast Supply Issues Prompt More Demand At Indoor Farms

By Ashley Nickle March 09, 2017 | 2:23 pm EST

Indoor farms are seeing increased demand as weather-related production issues in Arizona and California have affected the supply of leafy greens.

Rain has interrupted planting and harvesting in California throughout the season, and the Yuma, Ariz., deal is expected to finish earlier than previously thought after mildew proved to be a major problem.

With West Coast supplies tight, several indoor farms have reported increased interest from buyers.