Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Arizona Farmer Expands Sales Opportunities With ZipGrow Towers

The tri-cities area that includes Prescott, Prescott Valley and Chino Valley, Arizona — like many places in the country— has a population that’s becoming ever more careful about where food comes from

Arizona Farmer Expands Sales Opportunities With ZipGrow Towers

Posted by Eve Newman on March 30, 2017

‘Growing Hydroponically Just Makes Sense’

The tri-cities area that includes Prescott, Prescott Valley and Chino Valley, Arizona — like many places in the country— has a population that’s becoming ever more careful about where food comes from.

Patrick Wilcox, who owns Prescott’s Natural Wonders Farm, is hoping to be on the front end of that popular trend by selling hydroponic, locally grown produce at area farmers’ markets and to area restaurants.

“Everybody is getting more and more conscious of the food they’re eating and where it’s coming from, and they’re demanding more local produce,” Wilcox said.

Wilcox decided to join the small-farm movement as a way to piggyback on an existing vermiculture business, which he runs in conjunction with a landscaping company. “It was an easy entry,” he said.

He first began producing and using compost made from worm castings, also known as vermiculture, in his landscaping business. Then he started selling this compost at area farmers’ markets.

Worm castings are the nutrient-dense fertilizer created by earthworms as they move through the dirt. In other words, worm poo. While selling the worm castings, Wilcox noticed that many customers visited the farmers’ market with an eye for vegetables, not worm poo, and he wanted to capture that market as well.

He knew from the start that if he were to make a serious business out of farming, he couldn’t do it in the local soil. At 5,000 feet in elevation, with about 17 inches of rain a year, Prescott isn’t ideally situated for farming. “Unless you’re on a well — and you’ve got a very good well — it’s just not cost-practical to do it in the ground,” he said.

That’s when he found Bright Agrotech’s ZipGrow Towers. Over the last 18 months, he’s been learning everything he can about greenhouse farming and hydroponic growing, with current crops including lettuce, Swiss chard, kale, cilantro and other cool-season greens.

Wilcox is making a gradual, deliberate move into the farming world as he grows Natural Wonders Farm. He’s using 50 ZipGrow Towers now and estimates his greenhouse has room for a total of 150.

Over the next year, Wilcox is planning to add another 50 Towers while still running his landscaping business, expanding the vermiculture operation and becoming an expert in growing top-quality produce. In the meantime, he also wants to hone his sales skills, an area he said isn’t a strength but will be necessary as he grows.

Next steps include creating a brochure to advertise Natural Wonders Farm and meeting more chefs and restaurant owners. Wilcox sees sales to those entities as an avenue of potential growth and a way to carve a niche among other local farmers.

“I feel like going into the restaurants and later possibly into grocery stores will be the market I’m looking for,” he said.

He’s also working with one intern already and would like to add another couple interns to the Natural Wonders team.

Wilcox is hoping to maximize production on the acre of land he owns by growing outdoors as well as in the greenhouse. But even with a 10,000-gallon tank to capture rainwater, Prescott’s dry climate will always be a challenge for in-ground farming, and thus ZipGrow Towers will always be part of the equation.

“Growing hydroponically just makes sense,” he said. The same dry, sunny climate that makes farming a challenge also draws retirees from around the country. They’re bringing with them a demand for locally grown food, and Natural Wonders Farm is positioning itself to meet that demand.

Federal Realty Bringing Hydroponic Shipping Containers To A Shopping Center Near You

Federal Realty Bringing Hydroponic Shipping Containers To A Shopping Center Near You

Mar 29, 2017, 7:45am EDT

Updated Mar 29, 2017, 8:27am EDT

Michael Neibauer: Associate Editor Washington Business Journal

If shipping containers can be reused as housing, why not retrofit them for farms, too?

Rockville-based Federal Realty Investment Trust (NYSE: FRT) has struck up a partnership with a Boston-based company to bring farms contained in retrofitted shipping containers to select shopping centers across the United States.

The partnership with Freight Farms, according to a release, "empowers anyone to use this technology while repurposing Federal Realty's unused parking spaces as a place to locally and sustainably produce food that benefits the shopping centers' tenants, customers and community."

Freight Farms produces what it calls the "Leafy Green Machine," a "complete hydroponic growing system capable of producing a variety of lettuces, herbs and hearty greens." The 40 x 8 x 9.5 shipping containers, weighing 7.5 tons each, include climate technology and growing equipment — LED light strips, closed-loop water system, multi-planed airflow — to ensure a regular harvest, Freight Farms claims.

The Leafy Green Machine costs $85,000, plus an estimated $13,000 a year to operate. The containers consume about 100 kWh of energy per day. With that, plus water, Freight Farms says a farmer can harvest, for example, more than 500 full-size heads of lettuce per week.

"Finding the right location is a major hurdle for most new farmers," Caroline Katsiroubas, Freight Farms' marketing director, said in the release. "By partnering up with Federal Realty, we are eliminating a large barrier to entry for individuals looking to grow fresh produce for their local communities."

Federal Realty will offer parking spaces for rent to freight farmers, providing, perhaps, opportunities to partner with restaurants and grocery stores.

It is unclear whether any Greater Washington shopping centers will be selected initially for the shipping container rollout, expected this spring, though the program is expected to be expanded eventually nationwide. Federal Realty representatives were not immediately available for comment.

Federal Realty's properties in Greater Washington include Pike & Rose, Bethesda Row, Rockville's Courthouse Center and Federal Plaza, Free State Shopping Center in Bowie, Gaithersburg Square, Friendship Center in Friendship Heights and Sam's Park & Shop in Cleveland Park, and Graham Park Plaza and Barcroft Plaza in Falls Church.

Michael Neibauer oversees our real estate coverage and edits stories for the website and print edition.

Affinor Growers Signs an "On-Farm Test Agreement" with California Berry Company

Affinor Growers Signs an "On-Farm Test Agreement" with California Berry Company

Vancouver (Canada), March 28, 2017 - Affinor Growers Inc. (CSE:AFI, OTC:RSSFF, Frankfurt:1AF) (“Affinor” or the “Corporation), is pleased to announce the signing of a research and development Test Agreement with a large strawberry production company headquartered in California, USA.

The Test Agreement is a collaboration of Affinor’s vertical farming tower technology, proprietary strawberry seedlings from California, and the new greenhouse facility in Abbotsford, B.C. currently under construction by Vertical Designs Ltd. Under the terms of the agreement, specific strains of strawberry seedlings will be supplied for testing to optimize production within the unique environment created by Affinor's greenhouse tower technology. In return, Affinor will share the testing and production results, and collect a portion of revenue from berry sales to the local market.

Strawberries will be produced within a technically advanced light-diffused polycarbonate greenhouse. Vertical Designs Ltd. will operate the facility to grow and test the various strawberry strains in partnership with Affinor. It is anticipated the facility will be operational and planting will begin in late 2017. Affinor is working directly with the Californian strawberry producer over the next several months sharing information and collaborating on growing protocols to ensure the best varieties for vertical applications are identified.

Jarrett Malnarick, President and CEO said that“This is a great opportunity for Affinor to work with a company that has a long history in strawberry development and can offer strain specific seedlings to optimize production for our vertical farming equipment. It is one more step in bringing our technology to market with solid production testing data."

For More Information, please contact:

Jarrett Malnarick, President and CEO

604.837.8688

jarrett@affinorgrowers.com

About Affinor Growers Inc.

Affinor Growers is a publicly traded company on the Canadian Securities Exchange under the symbol ("AFI"). Affinor is focused on growing high quality crops such as romaine lettuce, spinach and strawberries using its vertical farming techniques. Affinor is committed to becoming a pre-eminent supplier and grower, using exclusive vertical farming techniques.

On Behalf of the Board of Directors

AFFINOR GROWERS INC.

"Jarrett Malnarick"

President & CEO

The CSE has not reviewed and does not accept responsibility for the adequacy or accuracy of this release.

FORWARD LOOKING INFORMATION

This News Release contains forward-looking statements. The use of any of the words "anticipate", "continue", "estimate", "expect", "may", "will", "project", "should", "believe" and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Although the Company believes that the expectations and assumptions on which the forward-looking statements are based are reasonable, undue reliance should not be placed on the forward-looking statements because the Company can give no assurance that they will prove to be correct. Since forward-looking statements address future events and conditions, by their very nature they involve inherent risks and uncertainties. These statements speak only as of the date of this News Release. Actual results could differ materially from those currently anticipated due to a number of factors and risks including various risk factors discussed in the Company's disclosure documents which can be found under the Company's profile on www.sedar.com. This News Release contains "forward-looking statements" within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended and such forward-looking statements are made pursuant to the safe harbor provisions of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995.

Agricultural Futures: From Home Aeroponic Gardens to Vertical Urban Farms

Around the world, urban farms are sprouting up at the intersection of new growing technologies and localvore movements.

Agricultural Futures: From Home Aeroponic Gardens to Vertical Urban Farms

03.27.17

Located in an abandoned 70,000-square-foot factory in Newark, New Jersey, the world’s largest vertical farm aims to produce 2,000,000 pounds of food per year. This AeroFarms operation is also set up to use 95% less water than open fields, with yields 75 times higher per square foot. Their stacked, high-efficiency aeroponics system needs no sunlight, soil or pesticides. The farm’s proximity to New York City means lower transportation costs and fresher goods to a local market. It also means new jobs for a former industrial district.

Around the world, urban farms are sprouting up at the intersection of new growing technologies and localvore movements. They vary in scale and focus, but their goals are generally similar: produce fruits and vegetables in more efficient, cheaper and greener ways. Growing in controlled environments also reduces environmental variables, like pests, weather and even seasons (allowing for more predictable year-round yields). Factory farm tenants can also take over and adaptively reuse structures in depressed areas with disused industrial building stock, creating employment opportunities in the process.

In a way, these endeavors are a natural extension of long-standing trends in farming. Small farms gave way to large farms, but the latter still involved open fields and variable environments. Urban farms take things to the next level, making the farm-to-table distance shorter, controlling conditions and further optimizing around available space.

Factory farm approaches are not without the limitations, however. Currently, the cost of material and technological inputs remain high. Also, many of these bigger indoor farms are designed to yield a limited subset of crops (like leafy greens) rather than a complex array of produce. Production weights and yield statistics would be somewhat less impressive were these farms focusing on a broader spectrum of fruits and vegetables, including ones that require more space to grow.

Still, the more these technologies are explored and refined the more efficient they will become — it is worth pushing them forward. At the same time, moving food production indoors and/or to urban settings is not limited to large factory operations. The global trend is unfolding at multiple scales and in different ways.

Expressions of commercial indoor farming can vary from one city to the next, responding to specific opportunities and needs in different built environments. In London, England, old subterranean WWII bomb shelters have been converted into herb farms serving local restaurants. In Berlin, Germany, a supermarket chain has introduced vertical micro-farms to grow greens for their shoppers right inside their stores. In New York City, a prototype barge farm docks at various stops, bringing produce to food deserts. In rural Japan, a high-tech vegetable factory run entirely by robots is set to produce 30,000 heads of lettuce a day.

Small-Scale & Individual Indoor Farming

While some initiatives focus on larger-scale or city-specific production, a trend is developing at the smaller end of the spectrum, enabling urban homeowners and small businesses to become part of a distributed network of production (much like 3D printing). IKEA, for example, now offers an aeroponics kit for indoor home gardening that needs no soil and uses sensors to monitor water levels.

IKEA also recently developed a prototype farming system aimed at letting restaurants grow their own ingredients in-house. As with larger-scale urban farms, these offer a critical advantage over outdoor equivalents: they require no rooftops or backyards to operate.

Integrated & Shared Indoor Farming

Hybrid approaches are also growing in popularity, combining aspects of collaboration and individualization. Shared farming space can take advantage of scale and consolidation but also build communities around shared tasks (and rewards).

A project called ReGen aims to combine the best of all worlds, blending urban, suburban and rural living in a series of off-grid communities. Each ReGen village hosts an integrated array of homes, greenhouses and other institutions, mixing farming and community. They are building the first prototype village outside Amsterdam and then aim to begin deploying the same model around the world.

A Tokyo office building, meanwhile, has already mixed productive greenery into its office spaces, aiming to provide workers with a more natural environment while growing edible fruits and veggies for their cafeteria. Food production is built right into the structure and aesthetic of the building, plugging nature directly into the architecture.

The Future of Indoor Urban Farming

At the heart of the ten projects featured here is an effort to rethink the way we produce food now and will in the future. Existing paradigms of small personal gardens and large outdoor farms can be thought of as bookends to a growing library of indoor farming possibilities.

Of course, some of these projects go viral without regard to feasibility, which could sour the public’s appetite for innovation when visionary designs fizzle in the face of reality. A Farmbot, for instance, sounds great in theory, but the device costs thousands of dollars and is arguably more of a novelty item than a practical technology.

It is hard to say whether large-scale urban farms, city-specific solutions, distributed-tech approaches or hybrid ideas will dominate the next generation of urban agriculture, but it is well worth pursuing projects spanning these extremes (as well as alternatives in between).

Exterior rendering of AeroFarms factory conversion in New Jersey

Aeroponics system diagram

Bomb shelter farm, supermarket micro-farm, floating barge farm and robot-run factory farm

Case Study: Boston Urban Farm Retailing Ordinance

Many major cities have embraced urban farming initiatives, including Chicago, Los Angeles and New York City. In the Big Apple, Gotham Greens launched with the goal of enabling urban farmers and providing the community with organic, pesticide-free vegetables

While urban farming was catching on in many cities, changes to a Boston ordinance — Article 89 — allowed urban farmers to sell direct.

BOSTON — Originally published June 4, 2014 — Boston officials passed legislation to accommodate a comprehensive transactional urban agriculture system to provide healthy, locally-sourced food in low-income neighborhoods. The law helps farmers grow and sell their produce within the city.

Goal

Boston residents had been pushing lawmakers to support urban farming legislation to increase accessibility of healthy produce to low-income neighborhoods. In response, the city passed Article 89 and the mayor signed it into law. Prior to the passing of Article 89, farmers were not permitted to sell the goods derived from city gardens. Likewise, local restaurants could not buy from farmers within city limits. The legislation expanded changes to the city’s zoning code that supported community gardens to also allow for urban farms.

Not only did Article 89 lift restrictions on growing and selling produce within Boston, but it also detailed all the steps farmers must take to properly build an urban farm and launch a local business in line with other city laws to avoid fines or penalties. It provides farmers the guidance they may need to translate growing practices into an urban environment, such as apartment building rooftops.

Furthermore, Boston officials identified city-owned pieces of land that would be suitable for farming as well as seeking out proposals from farmers interested in setting up a farm in the city. Farmers will be able to purchase up to 6,000 square feet plots of land for $100 to get their farms up and running, so long as the land is used for farming for the next 50 years.

Thus, Article 89 not only eliminated barriers to urban farming immediately, but set up requirements to ensure long-term sustainability of projects that address communities in need.

Urban Farms Sprouting

Many major cities have embraced urban farming initiatives, including Chicago, Los Angeles and New York City. In the Big Apple, Gotham Greens launched with the goal of enabling urban farmers and providing the community with organic, pesticide-free vegetables. The group leverages advanced technology to create a climate-controlled, greenhouse environment where produce can be grown year-round despite the New York City climate. Because their urban farms are not located on open rooftops victims to weather fluctuations, Gotham Greens produce is available year-round.

Gotham Greens has several locations throughout New York City. One 20,000 square foot space atop a Whole Foods in Brooklyn reportedly harvests 200 tons of organic produce annually. The facility utilizes hydroponic technology to provide plants with nutrients through a water supply, rather than soil. Through hydroponics, Gotham Greens is able to bypass the need for green space to support urban farming, instead focus on a water-efficient form of agriculture using recycled water to grow produce. Hydroponics offer a solution to problems plaguing farmlands across the country – such as drought and extreme temperatures – that are shrinking harvests and driving up fresh food costs.

City-Grown Goodness

EfficientGov has reported on a variety of urban farming initiatives, many of which start with simple adjustments to city zoning codes.

The Growing Trend of Vertical Farming

CBS NEWS

March 27, 2017, 11:46 AM

The Growing Trend of Vertical Farming

The world’s population will climb from around seven billion people to nearly 10 billion by 2050. That will make it even more challenging to feed everyone on the planet.

Companies like AeroFarms are rethinking how we grow fresh and affordable produce through vertical farming -- growing vegetables like kale, arugula and watercress indoors on shelves stacked seven levels high. When all is said and done, AeroFarms hopes to produce 1.7 million pounds of greens a year.

A 70,000-square foot facility, housed in a former Newark, N.J., steel plant, is AeroFarms CEO David Rosenberg’s green machine. It grows 130 times more produce than the average American field farm of the same size per year.

But to fully understand this large-scale operation, you’ve got to go back to its roots, where it all began seven years ago, inside Philip’s Academy Charter School.

AeroFarms’ prototype was planted in the school’s cafeteria as a teaching tool for students to learn the basics of biology, chemistry, and nutrition.

“I think growing food every day and seeing it, I understand and have a better taste for it, and understanding for it,” said student Susannah Love. “I appreciate it a lot more.”

The technology is called aeroponics, which grows plants on a re-usable fabric -- proprietary information.

But as Love explained it to CBS News correspondent Michelle Miller, this process needs no soil, no sunlight, and uses less water than conventional farming.

“We’re misting it from underneath, so the water comes up through the sheet and it hits the seedlings.”

Hits them with a nutrient-rich solution that allows the plant to take root. LED lights substitute for the sun.

Rosenberg says vertical farming offers higher yields with less land, less time, and no pesticides. They can farm indoors in any city, anywhere around the world: “From seed to harvest in 16 days, what otherwise takes 30 days in the field,” he told Miller. “And then we’re able to do that 22 times a year versus, in the field, three times a year, because of seasonality.”

Still, not everyone is sold.

“Early adopting is not necessarily bad,” said Cornell University researcher Kale Harbick. But he says his studies found indoor farms that rely solely on artificial light are not energy-efficient or sustainable.

“Just because it’s possible to grow inside a warehouse doesn’t mean it’s a good idea, doesn’t mean it’s cost effective,” said Harbick. “If you do the math, the energy costs just aren’t what they should be.”

Harbick warns these companies struggle once their seed money runs dry. Case in point: One Chicago-based company recently shut down its growing operations.

Rosenberg says AeroFarms LEDs that run 24/7 have been tweaked to save energy. He didn’t share just how much.

Investors believe in it. AeroFarms has raised more than $50 million from the likes of Goldman Sachs and Prudential, and received more than $9 million in state and local grants.

Miller asked, “Why would someone want to buy from you as opposed to a field farmer or a greenhouse farmer?”

“Here, we’re growing in the local community,” he replied. “That’s the supply chain difference. But it turns out that we’re able to compete on taste and texture.”

By adjusting the lights and nutrients, Rosenberg says they can also make their arugula more peppery, their kale a little sweeter.

Which for many of us, parents in particular, might be the biggest selling point of all, to get their kids to enjoy their greens.

AeroFarms’ product is available in area grocery stores and supermarkets for about $3.99 a package.

For more info:

Aerofarms' 70,000-square foot facility, a former Newark, N.J., steel plant, grows 130 times more produce than the average American field farm of the same size per year.

CBS NEWS

Seedlings being grown by students at Philip's Academy Charter school. The students grow some of the greens for their cafeteria's salad bar.

CBS NEWS

CEO David Rosenberg gives correspondent Michelle Miller a tour of Aerofarms' vertical farming facility.

CBS NEWS

How A Rooftop Farm Feeds A City

How A Rooftop Farm Feeds A City

You all probably know my love for greenhouses, local food and educating city folk on where their food comes from.

Last night, I just put on another ted talk to watch whilst I cooked dinner, and decided to simply click on one of the ‘recommended’ videos that popped up on Youtube. My mood went from average to incredibly happy, in a matter of seconds. THANKS Youtube, you have impressed me once again.

This Ted talk video merged all these passions of mine, into one.

Greenhouses formed the major part of my first job as a graduate. I loved observing how the crops were growing in a protected environment, and how different growing techniques influenced the quality and yield gained. My Australian boss was Dutch, so understandably I learned a lot on the processes involved with growing a good greenhouse crop, from this expert.

Local food, as outlined in the video, is something that ‘is not new’ but something we miss in urban populations. I love growing my own veg at home, and consider myself to know quite a bit about agriculture, however, I cringe a bit, every time I visit a farm to see waste, or hear of food getting wasted. In the Montreal rooftop greenhouse outlined in the video, there is very little food waste, as produce is eaten very soon after production, with minimal transportation. Incredible.

Educating city folk on where food comes from, my final passion, really needn’t even be an issue. Hearing towards the end of the video, that urbanites were picking their own food and reducing the need for not only food miles, but resources, whilst seeding sustainability by knowing their food, just gave me so many warm fuzzies- we definitely need more of this.

So in this Ted Talk, Mohamed Hage, a Lebanese born Montreal-dweller, educates us on the disconnect I observe daily, and how to address it, by utilizing the ‘underwear’ of the building- the roof.

Sustainable agriculture means recycling water, optimizing energy use and growing without any synthetic pesticides, herbicides or fungicides. It doesn’t just stop at the farm.

- Water conservation: Recirculation of irrigation water and capturing rain water

- Pest control: Biocontrols take care of harmful pests

- Saving energy: Using half the energy to heat

- Compost: Composting organic waste on-site

- Freshness: Delivering the same day produce is harvested

Here is his business if you’d like to read more: http://lufa.com/en/ Please do- it’s an amazing website and concept.

Here we go, Canadians, once again, bawse.

Who else is up for greenhouses on supermarket/community centre rooves? Who would like to help me instigate this technology in Australia’s largest cities of Sydney and Melbourne?

HELP SPREAD THESE LITTLE SEEDS OF SUSTAINABILITY FOR ME!

Peace,

Jess

Innovator Uses Technology To Build Urban Micro-Farms

Innovator Uses Technology To Build Urban Micro-Farms

Former resident’s Cityblooms firm working on sustainable food solutions.

By Aleese Kopf - Daily News Staff Writer

Nick Halmos, the son of Palm Beach resident Vicki Halmos, recently received an Innovator of the Year Award for his company Cityblooms and its work for sustainable food solutions in Santa Cruz, Calif. Halmos is seen here at his mother’s home Thursday in Palm Beach.

(Michael Ares / Daily News)

Posted: 6:30 a.m. Monday, March 27, 2017

Nick Halmos, son of longtime Palm Beacher Vicki Halmos, recently was recognized for his work to fight food insecurity.

Halmos, 37, grew up on the island and attended Palm Beach Day Academy. He now lives in Santa Cruz, Calif., and is CEO and founder of Cityblooms, a company that uses technology to create controlled, micro-farms in urban environments.

Cityblooms farms grow in an enclosed environment with automated controls for temperature and water use. Farm management software keeps track of crop schedules and maintenance.

Last week, Halmos was named Innovator of the Year by Event Santa Cruz at its annual NEXTies awards show that honors individuals and businesses who inspire the Santa Cruz community.

Halmos, a graduate of Brown University with a law degree from Vanderbilt, was recently in town and shared what his company is about and why its work is important.

How did you become interested in farms and growing things?

I first became interested in urban agriculture in an entrepreneurship class (my undergraduate focus) at Brown. At that time (2001), global warming issues were finally getting mainstream attention. I became keenly interested in the business case for improving supply-chain inefficiencies in our food system by learning to grow food in the underutilized nooks and crannies of the urban environment. In other words, what would happen if we could bring the farm to the people and measure seed to fork in yards, rather than miles?

What was your first project?

After graduating from Brown, I stayed in Providence and started to collaborate with some of my friends who had just graduated from RISD [Rhode Island School of Design]. They were interested in urban renewal. I was interested in urban farming. So together we built the first “shipping container farm” by building a hydroponic system inside an old shipping container. We set up operations at an abandoned steel mill and that project ran for three years, growing basil for restaurants in the Italian district of Providence.

What was your first Cityblooms success story?

It must have been my proximity to major technology and agricultural centers (i.e. Silicon Valley and Salinas), but by 2011, I once again found myself keenly interested in the technology of growing food. I spun the Cityblooms effort back up inside a barn where we built almost 50 prototypes and filed four patents before we drew the attention of one of the large technology companies in the Bay Area (Plantronics) that was interested in hosting an installation to grow fresh produce for its campus eatery. This gave us the incredible opportunity to put some of our ideas into action and make a big push forward with our technology.

That first “food growing robot” has been remarkably successful and has produced over 100 different varieties of crops in the three years since our first harvest. It was not long before other organizations were contacting us about similar projects. Over the course of the last three years, we have been fortunate to work with companies as large as Apple and as small as our local community organizations. In the process, we have learned how to create intensive food-producing systems in a variety of underutilized urban settings such as parking lots, rooftops, and warehouses. We have also been fortunate to be able to deploy our technology in more traditional agricultural settings, such as the greenhouses of Central California.

Why are you passionate about this topic?

The Cityblooms team is passionate about contributing to the transformation of our food system. With a global population projected to reach 9 billion by 2050, global agricultural output must increase by 70 percent. As Nobel Prize winner Normal Borlaug pointed out, over the next 50 years we have to produce more food than we have in the past 10,000 years. Considering the impressive sustainability gains created by efficient and local food production, there will be the opportunity to grow certain classes of highly perishable crops in a much more decentralized, and community oriented, fashion than the status quo. This will not be the single silver bullet that solves this tremendous challenge, but it will be a part of the larger solution.

How can residents and businesses contribute to food sustainability?

There are many fruits and vegetables sold in Palm Beach stores that travel thousands of miles. This not only has a negative impact on the environment, but also food that travels long distances can be of inferior quality to locally sourced products. For example, many types of green vegetables can lose up to half of their beneficial nutrients after only a few days in packaging.

Palm Beach residents can help this transformation of our food system by supporting locally grown products. Consumers should embrace the seasonality of fresh produce items. Look at the packaging on your food, and pay attention to where it is from. Vote with your wallets and buy local. As the demand for local food products increases, local farms will spring up to meet that demand.

A Future Farming Industry Grows In Brooklyn

A Future Farming Industry Grows In Brooklyn

The startup Square Roots is training the next generation of urban farmers in a Bed-Stuy parking lot.

By Alexander C. Kaufman, Joseph Erbentraut

ROOKLYN, New York ― Tobias Peggs is already cultivating leafy vegetables out of purple-lit shipping containers in the parking lot of an old Pfizer factory, just blocks from the projects where the rapper Jay-Z grew up.

What he needs to grow now is an industry.

Eight months ago, Peggs co-founded Square Roots ― a startup that coaches and equips would-be urban farmers with growing materials in repurposed 320-square-foot metal crates. He launched the venture with food and tech entrepreneur Kimbal Musk, the younger brother of Tesla and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk.

Now, 10 farmers are enrolled in Square Roots’ Brooklyn farming program, Peggs and Musk have launched a new delivery service for home-grown salad greens, and they’re deciding where to expand next.

“If we have a campus like this in every city, everyone can buy food from a local farmer,” said Peggs, 45, said as he showed The Huffington Post around his operation.

Located in the shadow of the Marcy Houses, a public housing complex in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, the former pharmaceutical plant that houses Square Roots now also provides office space for scientific research ventures and startups that ferment kombucha and kimchi, make high-end slushies and Madagascan chocolate, and even grow live oysters.

Peggs is Square Roots’ chief executive, and he has lofty plans to topple the industrial giants that dominate grocery aisles. “This is a very long-term play, to bring real food to everyone and unleash, basically, the next generation of leaders in food.”

“Ambitious,” he added with a laugh.

Square Roots was launched under the umbrella of The Kitchen LLC, Musk’s equally ambitious chain of farm-to-table eateries that he hopes will one day take over the food industry sector that TGI Friday’s and Applebee’s currently dominate.

Musk, 44, draws his inspiration from Chipotle Mexican Grill, where he serves as a board member. Chipotle leveraged its use of fresh, non-genetically modified ingredients to become a major rival of McDonald’s, despite charging higher prices. The Kitchen, which has three different restaurant concepts, operates primarily out of the American heartland, with nearly a dozen locations in Chicago, Memphis and throughout the state of Colorado. Another restaurant is slated to open in Indianapolis this year.

Musk and his colleagues are looking at all of those cities as the next possible site for a Square Roots campus.

“My heart is in Memphis, so if it were up to me, that’d be our next city,” Musk told HuffPost on Thursday, stressing that it’s ultimately up to Peggs. He wants to see Square Roots expand rapidly. “We are planning on doing this with thousands of kids a year within a few years.”

If we have a campus like this in every city, everyone can buy food from a local farmer.Tobias Peggs, chief executive of Square Roots

In Colorado, where The Kitchen is headquartered, it’s easy to get local produce, meat and alcohol. But that’s not true in a lot of major cities. That’s the niche Square Roots wants to fill. The company is the country’s first major indoor farming “accelerator” ― Silicon Valley parlance for firms that offer educational training, space and capital to bootstrapped entrepreneurs.

Enrollees complete an eight-week boot camp before setting up shop in one of Square Roots’ 10 shipping containers. They then have the next 10 months to grow vegetables and come up with novel ideas to sell them. Square Roots makes money by taking a cut of the revenue. If an idea takes off, Square Roots buys a stake in the company and introduces the farmer to other investors.

“I visualize opening Fortune magazine in 2050, and there’s a list of the top 100 food companies in America,” Peggs said. “No. 1 is Square Roots. And the other 99 have all been set up by folks who graduated from Square Roots.”

Indoor and vertical farming, essentially a techy subset of greenhouse agriculture, has recently attracted entrepreneurs competing to develop new hardware and the most energy- and water-efficient growing systems.

The benefits of growing indoors are numerous. Farmers don’t need pesticides or herbicides to ward off unwanted pests. They evade droughts, temperature shifts, whipping winds and flooding rains, all of which are becoming more destructive and erratic as greenhouse gases warm the planet and alter the climate. They are free from environmental contaminants ― a big plus in places like Japan, where, since the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, people fear radiation poisoning from food grown outdoors.

And on a baseline level, vegetables grown indoors under precise conditions can be bred to taste better. Peggs said one Square Roots farmer who is cultivating shiso, a red-leafed mint, used data on the climate in Hokkaido, Japan’s breadbasket northernmost island, to replicate conditions there. Instead of raising crops in one country and shipping them to another to be eaten, farmers could cut out the financial and environmental costs of transportation and grow even exotic produce in the dead of a New York winter.

“Let’s say the best basil you ever had was on vacation in Italy in 2006,” Peggs said. “You could look up the data on rainfall, temperatures and weather and grow basil in those exact same conditions.”

In September, Square Roots began working with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to rewrite criteria for government-backed loans, making them more accessible to indoor, urban growers.

The USDA postponed a meeting with Peggs scheduled for Thursday afternoon, hours after agriculture secretary nominee Sonny Perdue testified before a Senate hearing. The USDA did not respond to questions on Friday about the status of changes to the loan applications.

“We want these kids to know they’ll be getting a loan, and they’ll have to pay it back and have to build a business and make money for themselves all in the space of one year,” Musk said. “It’s a loan, not a grant. It’s not a handout; these are real businesses.”

Ten shipping containers like this house Square Roots’ local farming initiative in Brooklyn, New York.

ALEXANDER C. KAUFMAN/THE HUFFINGTON POST

Lettuce and arugula grow on long, vertical trays in the glow of purple LED lights.

ALEXANDER C. KAUFMAN/THE HUFFINGTON POST

Urban Farmers Catch New Train

March 24, 2017

The urban farming movement is taking a new twist, or rather, is on a new track. Growers are producing crops in refitted freight train cars, using hydroponics and automated systems equipment.

Each former freight car costs $85,000, not including shipping, with each “controlled environment” container producing an estimated average annual profit of $39,000. A 320-square-foot car is capable of producing roughly what a three-acre farm could, while using 95% less water than traditional farms.

Boston-based Freight Farms, the manufacturer of the equipment, says the most popular destinations for the 7.5-ton high-tech freight cars are urban areas across the country. The movement recently expanded into Arizona, where two urban farmers are growing crops in the cars.

The goal is to bring viable, space-efficient farming techniques to all climates and skill levels year-round. Quality and sustainability is enhanced, since produce travels shorter distances too.

Olive Trunk Farm Seizes the Opportunity To Feed Texas Town

It took a bout of food poisoning to convince Scott Rowdon to grow his own food, but now the Texas farmer has his eyes set on growing fresh, healthy food for everyone around him

Olive Trunk Farm Seizes The Opportunity To Feed Texas Town

Posted by Eve Newman on March 24, 2017

Food poisoning spurs local food conversion

It took a bout of food poisoning to convince Scott Rowdon to grow his own food, but now the Texas farmer has his eyes set on growing fresh, healthy food for everyone around him.

Rowdon’s foray into farming began with an emergency room visit following dinner at a local burger joint near his home in Little Elm, Texas, about two years ago. “It came about kind of on accident,” he said.

After his recovery, Rowdon decided he wanted to grow more of his own food. But like much of Texas, Little Elm — which sits on the northern side of the Dallas/Fort Worth metro area — isn’t celebrated for its soils.

“Down here in Texas, we have horrible clay soil,” Rowdon said. “It is horrible. But I thought, there had to be a way to be able to grow.”

He began exploring aquaponics and built his first system using a 55-gallon drum and a stock tank with catfish, all indoors. Then he came across Bright Agrotech’s hydroponic technology and purchased a ZipGrow Tower system, which soon became a second system, then a wall, then 25 Towers.

“It just continued to grow,” he said.

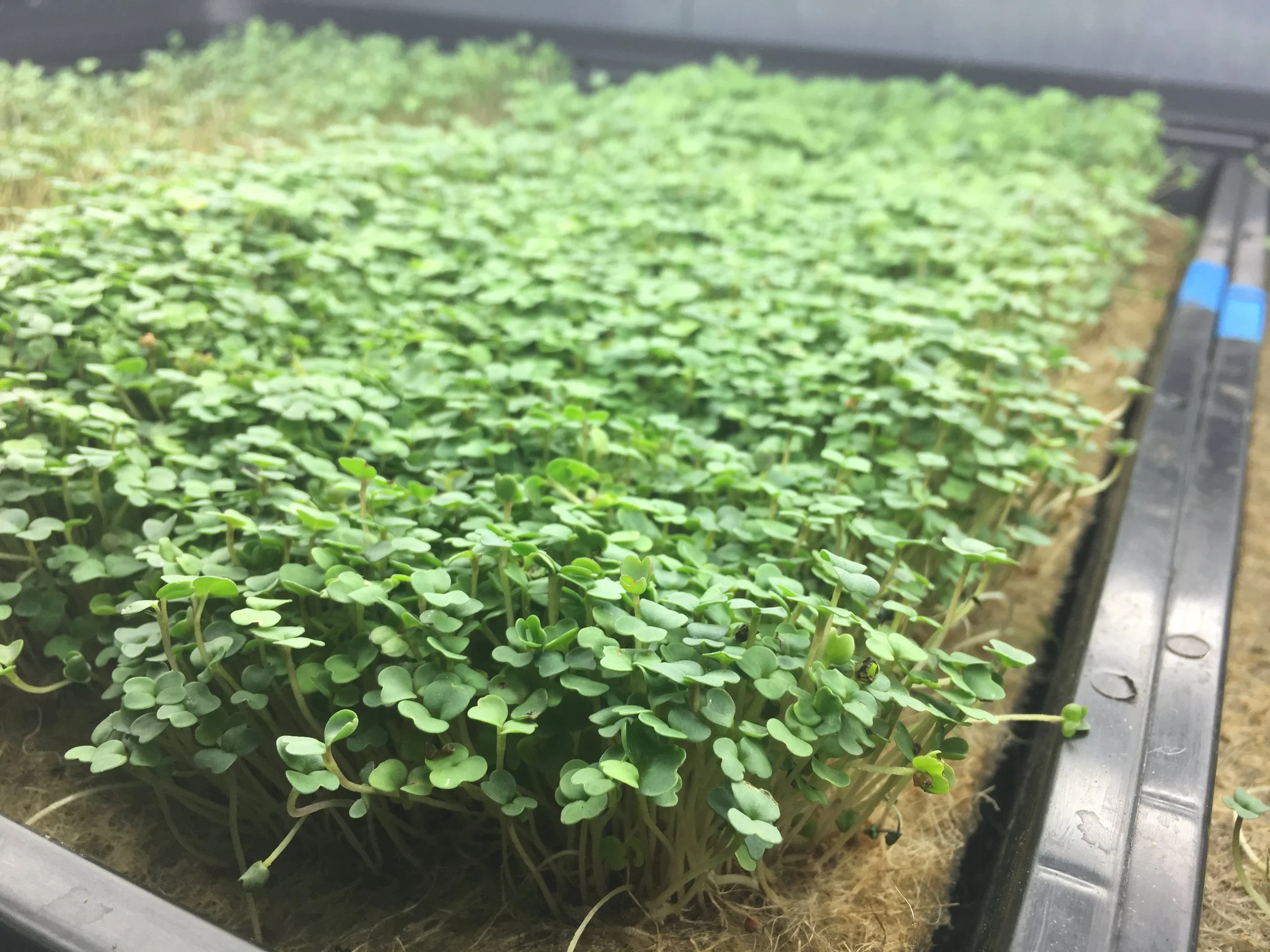

Rowdon began growing microgreens and herbs for himself, family members and friends. Then he started selling them at farmers’ markets about a year ago, and Olive Trunk Farms was born.

Microgreens are especially exciting, and Rowdon uses their vivid colors and bright flavors as selling points.

“Whatever I have at the market that day, I have samples for,” he said.

For customers who don’t want to eat full-grown kale or broccoli, Rowdon presents tiny shoots packed with nutrition and flavor, grown locally, harvested that day and fresh as can be.

One repeat customer, who has been purchasing Olive Trunk Farms sunflower shoots for the last year, said she had trouble maintaining healthy vitamin levels because of medication she takes. But after adding microgreens to her daily meals, her most recent blood work came back great even without supplements.

“[Microgreen sales are] going to be all about education and what you can do with microgreens,” Rowdon said. (Learn about microgreens for yourself here.)

He’s planning to take his greens to Earth Day Texas in Dallas in April, which is touted as the world’s largest Earth Day festival. More than 130,000 people attended last year’s three-day event to learn about the latest technologies and innovations shaping the world.

In June, Olive Trunk Farms will have a booth at the new Frisco Fresh Market, a daily market to be open year-round. The indoor/outdoor market will bring together farmers, foodies and chefs to 30 acres in central Texas to share their love for local produce, and Olive Trunk Farms figures to be right in the mix.

Rowdon is also looking ahead to moving Olive Trunk Farms from its current urban location to a spot with more space for indoor and outdoor growing, where he can power his operation using solar and wind. Already he’s working on ways to recycle and conserve water, such as running a dehumidifier with the microgreens and storing the excess water, which cuts into his water usage.

“My hope is to have an extremely small footprint, but yet very productive,” he said.

As a self-proclaimed technical person with a background working for a financial institution, Rowdon is still surprised about becoming an accidental farmer. But now he’s looking forward to working with his hands, digging into soil and building a business.

“Watching everything I grow from seed to harvest is just absolutely amazing,” he said. “It never ceases to amaze me watching all of this happen and the changes every single day. It’s never a dull moment and it’s never the same day twice,” he said.

He’s also enjoying being part of the growing community of local food producers bringing healthy produce to their friends and neighbors. “It’s healthy, it’s fresh, it’s local, and we want healthy people,” he said.

Interested In Becoming A Farmer Like Scott?

The Upstart Farmers are the modern farmers responsible for hundreds of indoor local farms around the world. Though from a variety of backgrounds and unexpected skill sets, the Upstart Farmers find themselves unified in their vision to feed healthy food to their communities and overcome the limits of traditional ag with innovative farms.

Upstart University trains new farmers to find markets, build farms, and gow incredible crops. Join Upstart U for a free week today to explore your potential as a farmer.

More Speakers Confirmed For GFIA Future Farming Theatre

Already many experts have been confirmed to speak about smart farming at the Proagrica Future Farming theatre at the Global Forum for Innovations in Agriculture (GFIA).

24 Mar 2017

More Speakers Confirmed For GFIA Future Farming Theatre

Already many experts have been confirmed to speak about smart farming at the Proagrica Future Farming theatre at the Global Forum for Innovations in Agriculture (GFIA).

The GFIA will be held from 9-10 May 2017 at the Jaarbeurs Expo Centre in Utrecht, the Netherlands. The event will focus on practical applications and knowledge on Future Farming in horticulture, crops and livestock. The event is organised by Turret Media in cooperation with Proagrica (publisher of All About Feed, Farmers Weekly, Boerderij amongst others)

Proagrica will have its Future Farming Proagrica Theatre, held over 2 days, at the exhibition ground. At this theatre, new ideas, future farming insights will be shared in the fields of dairy, pig and poultry farming, horticulture and arable farming, each having 3 focus topics. The editors of Proagrica brands will moderate the sessions. Each session will have an independent speaker and 2 sponsored speakers. We are proud to confirm some of the speakers to you.

Future Farming Poultry: Feeding, animal management, big data

Poultry breeding has become precision agriculture and a fine art. Sergio Guerra from Aviagen will talk about the use of big data in poultry breeding and how this can be used by the whole production chain and what are the latest insights?

Ron Cramer from Xiant Technologies (XTI) will speak about innovative lighting in poultry barns. XTI has created a highly differentiated approach to agricultural lighting for both poultry and plants. XTI uses light as a primary controller of biological function by targeting specific photoreceptors in a variety of living species.

Future Farming Pigs: Genetics and breeding, gestation and lactation, grow/finishing

Jurgen van Geyte from the Belgium research institute ILVO has done research in the use of big data in pig production systems. ILVO is part of the project IOF2020, a large scale pilot focused on implementation of Internet of things. How does this apply to pigs? Van Geyte will delve more into that.

Dirk Coucke from DLV Mas in Belgium will speak about an innovative pricing/market advisory service/tool for pig farmers who buy their own raw materials and complete feed. A smart way of doing business is smart purchasing of feed.

Future Farming Dairy: Robotic milking, hygiene, young stock

Calves are the basis for a successful dairy farm. More insights have been gained on smart feeding/housing for calves. Expert Siert-Jan Boersema from Jongvee Coach in the Netherlands will present the latest insights on smart ways to get the most out of young stock.

Future Farming Horti: Precision farming, track and trace, robotics

Marc Kreuger, global head of innovation at the company Here, There and Everywhere. This company designs and builds turnkey indoor farming projects, supplies long term technical and growing support and is actively involved in starting up new businesses and supply chain models that include indoor farming solutions. He will update the audience on the latest insights and developments in this field.

Future Farming Arable: More efficient harvesting, control of pests, use of big data

Sjaak Wolfert from Wageningen UR in the Netherlands will give a short overview of smart farming in agriculture / outdoor cropping systems and how big data is used to boost efficiency and production.

Jérémie Wainstain, CEO of The Green Data will speak about how to extract value from your data. The Green Data Factory is a suite of services dedicated to agridata analysis to give you the power to optimise performance and adoption by your experts.

Want to pitch your idea/product/concept? Companies can still be part of this exciting and innovative theatre for one slot or as sponsor of the whole theatre (including slots for presentations)! Do you want to share your knowledge and practical insights in a 20 minute practical talk and share this directly with the farmers and international experts in the audience? For more information, please contact our dedicated team of account managers to tell you more about the possibilities.

Emmy Koeleman

Editor: All About Feed & Dairy Global

Impression of the Proagrica Future Farming Theatre at the GFIA. An exciting place where 5 seminars will be held about smart farming, with a practical ‘How To’ approach. Photo: Proagrica

McNamara: “The Future Is So Much More Complex Than We Could Have Imagined”

Brad McNamara, CEO and co-founder of Freight Farms, is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery,” which will be held in collaboration with Tufts University and Oxfam America on April 1, 2017

McNamara: “The Future Is So Much More Complex Than We Could Have Imagined”

Brad McNamara, CEO and co-founder of Freight Farms, is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery,” which will be held in collaboration with Tufts University and Oxfam America on April 1, 2017.

Freight Farms is an agriculture technology company that provides physical and digital solutions for creating local produce ecosystems on a global scale. Brad and his co-founder, Jon Friedman, developed the company’s flagship product, the Leafy Green Machine, to allow any business to grow a high-volume of fresh produce in any environment regardless of the climate. His hope is for Freight Farms to be scattered across the globe making a dramatic impact on how food is produced.

Food Tank had the chance to speak to Brad about his work developing Freight Farms and his vision for the future of our food system.

Brad McNamara, CEO and co-founder of Freight Farms, is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery.”

Food Tank (FT): What originally inspired you to get involved in your work?

Brad McNamara (BM): It was a coming together of many different factors. My co-founder, Jon, and I had worked together in the past, and we were both intrigued by the food system and how we could make a difference. Around 2009, Jon was focused on food systems and system design, and I was passionate about the purity of food and the increasing trend towards food awareness. When the two of us first reconnected over a cup of coffee (and then a beer), we got to talking about the complexity of the food system and what we could do to combine our interests. With backgrounds in design and environmental science, our goal was to research methods to allow urban agriculture to emerge as a competitive industry in food production. We mainly focused on rooftop development, then determined the criteria for success and scale to be outside the realm of possibility with agricultural installations that were already in existence. When costs and logistics soared, we turned to shipping containers (there’s Jon’s design background coming into play), and the idea for Freight Farms took off with the goal to build farms in areas that couldn’t support more traditional methods.

FT: What makes you continue to want to be involved in this kind of work?

BM: Our world and our climate are changing, and it is so apparent that there is more work to be done. According to the U.N., food production needs to increase 70 percent by 2050, to feed an ever-urbanizing population. Land and water scarcity take on even more pressing importance, as does urban agriculture. The future is so much bigger and more complex than we could have ever imagined. Over the past few years, we’ve gotten to witness the emergence of a new industry of agriculture technology, and it’s poised to make a dramatic impact on the food system. One of the most amazing things we’ve been able to watch is how many are interested in joining the movement towards a better future. Our network of freight farmers are making dramatic impacts on their local food systems every day, drastically improving food security in their community. They inspire all of us to continue this work.

FT: Can you share a story about a food hero who has inspired you?

BM: My food hero is a customer of ours. His name is Ted Katsiroubas, and he runs Katsiroubas Bros. Fruit and Produce, a wholesale produce distribution company located in the heart of the city of Boston. The business is over 100 years old and was handed down from generations before. I admire how Ted has innovated in the face of a dramatically changing food landscape. As the demand for local, fresh produce has risen, the company expanded to begin working with local farms in the region to meet demand. For those familiar with wholesale distribution, sourcing locally can be a difficult task especially when you are restricted by the growing seasons and volume constraints of small local farmers. That’s why traditionally wholesale distributors rely on shipping produce long distances from warmer climates. But Ted brings a fresh approach to an old school industry. He continues to push the envelope and propel the industry to stay on top of the latest technology through collaboration with other distributors. If anyone were to fall into the category of my food hero, it would be Ted because of his willingness to look to the future and go against the conventional wisdom of how the food industry tells him to conform.

FT: What do you see as the biggest opportunity for fix the food system?

BM: I think the biggest opportunity to fix the food system is to bring it back into the hands of the people. By transitioning to a more decentralized food system, and minimizing the gap between consumers and producers, we will take a critical step towards an environmentally and economically sustainable food system. I think all the various types of technology, the hardware, the software, and the social awareness, all point in the direction to empower the individual. So the real opportunity to fix the system is to utilize what we know to be true—when you give opportunity and power to regular people from all walks of life, that’s when you can change a whole system.

FT: What would you say is the most pressing issue in food and agriculture that you would like to see solved?

BM: There are so many people advocating for a better food system, and we all must be better at communicating and cooperating if we want to make an organized effort to challenge the way things operate currently. From small farmers and producers to organizations and companies. What has become incredibly apparent in the past couple decades is that there is no one size fits all solution. Whether it’s urban or indoor agriculture, hydroponics, aeroponics, aquaponics, or traditional soil-based farming, we all play an important role. We need to have a more holistic view of the food system and how each method can contribute to a better future. If we don’t all work together, it’s going to be difficult to disrupt BigAg. I think taking a broader view is key. There has been so much progress made in agriculture, but we still have a long way to go to create a food system that will serve future generations. It is important to continue working with and connecting with each other to empower and support the next generation of farmers.

FT: What is one small change everyone can make in their daily lives to make a difference?

BM: Maybe it is a bit cliché, but the notion of voting with your dollars. I’m sure others have said it, but it is so important. If every consumer changed 5 percent of their food shopping habits by buying more seasonal and local produce, the impact would be enormous in changing the landscape of the local grocery store.

FT: What advice can you give to President Trump and the U.S. Congress on food and agriculture?

BM: My advice is to be conscious of all the complexities present within the food and agriculture system. There are so many moving pieces that small shifts in the workforce, water use, and the climate have a massive impact throughout the entire system. It is essential to keep a holistic understanding of the relationships between all the components in our food and agricultural system and to consider the ripple effect policy decisions will have on the smaller players involved.

Click here to purchase tickets to Food Tank’s inaugural Boston Summit.

How Urban Farming Took Root Everywhere

HOW URBAN FARMING TOOK ROOT EVERYWHERE

Published On 03/22/2017

Chicago’s Back of the Yards neighborhood was once one of the most industrialized areas in America, where stockyards and factories were manned by thousands of working-class immigrants. It’s the setting of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. But today, inside a 93,500-square foot former meatpacking plant there, kale, swiss chard, tomatillos, and oregano grow in vertically stacked trays, nourished by water from a nearby tank of tilapia. There are two additional hydroponic farms growing greens, plus a brewery, bakery, a mushroom farm, an artisan cheesemaker, honeybees on the roof, and a fresh flower farm. In total, there are 12 food-producing tenants in the gigantic, industrial space.

Unlike the neighborhood’s original pork-based economy, this new microscale ecosystem is working towards conducting business without letting a single item go to waste.

“IT IS MUCH MORE THAN AN URBAN FARM. IT’S KIND OF LIKE A MOVEMENT, OR A WEIRD EXPERIMENT.”

The Plant, as the facility is known, is considered a “collaborative community of food producing businesses” that work together inside the former meatpacking plant to not only grow and produce food -- but to create a “closed loop” system for energy, waste, and materials. Meaning that everything is reused: spent grains from the brewery are formed into briquettes to fuel the bakery ovens, coffee grounds from the roastery inside are used to help nourish the mushroom soil. At The Plant, that closed loop system is managed by not-for-profit group Plant Chicago.

Plant Chicago staff also teach the public about this closed loop, circular economy through tours, education programs, and a year-round farmer’s market.

“It is much more than an urban farm,” Kassandra Hinrichsen, education and outreach manager for Plant Chicago says. “It’s kind of like a movement, or a weird experiment.”

It’s not just about providing fresh vegetables

The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations reports that 800 million people practice some form of urban agriculture worldwide, even though it’s illegal in several countries. The USDA doesn’t keep formal stats on urban farming in the United States, but in 2016 it funded about a dozen urban farms, the largest in the agency’s history, according to Business Insider. Even more loans and grants are expected to be given out to urban farmers in the United States this year.

But urban farming isn’t a new phenomenon for America’s cities. In the 1970s, community gardens sprang up in vacant lots in New York City, Chicago, Detroit, and San Francisco -- providing not only a place to grow fresh vegetables, but also a way for urban communities to organize. In 1993, Will Allen purchased a piece of land in Milwaukee so he could sell vegetables from his nearby farm to people in the North Side neighborhood. He then started farming food right in the city -- a project that would become Growing Power, one of the first urban farm projects in the country. In 2009, the Eagle Street Rooftop Farm in Greenpoint opened, becoming New York City’s first commercial rooftop farm. But in the eight years since, as more people have a desire to eat local foods within urban areas, the trend has stretched far beyond Brooklyn.

An increasing number of farms are taking on innovative projects that do much more than just provide food. Like Plant Chicago, for instance, which is charged with researching ways to reduce waste and reuse it at the farm, as well as conducting outreach with the neighboring community.

One of the largest endeavors, which is the brainchild of The Plant’s founder, John Edel, will be to use an anaerobic digester tank to heat the entire facility, rather than electricity or gas. Once it’s online, the energy system will be able to process 30 tons of food waste a day in the same way a human stomach does. It will break down the waste into liquid, biogas, and a high-nutrient solid. The solid and liquid will be sold to soil companies as a compost, while the biogas will be used to heat the building.

Plant Chicago staff and volunteers are also responsible for maintaining the aquaponics farm at The Plant -- a system where plants grow in water and receive the nutrients they would normally get from soil via waste created by fish. The plants, in turn, filter the water for the fish. This sort of farming has become increasingly popular in Chicago, with several for-profit and non-profit farms popping up around the city, in everything from warehouses to classrooms.

“In Chicago in the last couple of years, there has been a crazy bump in indoor farming, like hydroponics and aquaponics facilities,” Hinrichsen says. “Hopefully, indoor farming and those kinds of systems are becoming more accessible to folks, because the point of Plant Chicago is to be open sourced as well, and to show that you don’t necessarily have to have a bunch of money and crazy investors and a business degree to start something like this.”

Farm-to-table is eating better, which is the best way of living better. Fresh food will revitalize your spirits as well as your body -- even in the heart of a city. To reward yourself for living so well, open a bottle of Strongbow cider, and let the crisp and refreshing orchard taste come to you.

What we can grow in cities, and how we use it, is changing

Elsewhere, in Chicago, another company looks to turn the city’s world-famous architecture green.

Thanks to the laughably high prices of land in some cities, urban farmers looked to city roof tops as a potential growing site for their farms early on. But, while they may be more affordable, growing edible crops on a roof comes with it’s own set of problems.

“If you’re trying to grow food in a completely foreign environment, where you don’t have nutritious substates, when you don’t have reliable water, when you have extreme temperatures -- extreme cold and extreme heat -- that’s like Mars, and that’s pretty much what it’s like to grow on a rooftop,” says Molly Meyer, the CEO and founder of Omni Ecosystems, a green roof company based in Chicago.

Meyer’s company developed a green roof system that could allow plants to thrive, despite the harsh conditions. Their green roof technology supporting edible crops is not only lightweight, but includes intuitive irrigation systems. Automated watering systems are linked up to weather stations or rain sensors, to make sure the crops aren’t being watered when rain is in the forecast.

Meyer founded Omni Ecosystems in 2009, but she had worked with green roofs for years previously, and installed her first green roof in 2006 atop True Nature Foods in Chicago. She continued studying green roof tech in Germany as a Robert Bosch Fellow. Germany implemented green roof technology decades back, so Meyer’s experience there amply prepared her to start a company in the United States.

Omni has installed dozens of green roofs from Boston to San Francisco, as well as the vertical gardens known as “living walls” and subterranean barriers so that crops may be planted safely above contaminated earth. It also manufactures its own soil. But at first, Meyer says the trend was slow moving -- thanks in part to how long it takes for buildings to be designed and constructed.

“The construction industry, and the building industry in general, is very slow industry to change,” she says. “It takes maybe a year to design a building, and a year to build a building. And so, you have a couple years just for one site to change over. Now, we’re really starting to get a clip going. We’re starting to see some snowballing effects. People have seen the technology now, they are recommending and referring it, and applying it.”

Most of their edible crop rooftop farms produce the usual stuff: leafy greens, tomatoes, peppers, etc. But, just last year they were able to grow an entire wheat field in the middle of downtown Chicago -- and it was practically unintentional.

Omni was hired to build a native wildflower meadow on top of the Studio Gang Architects’ rooftop on Division Street. But the construction schedule was pushed into the fall, forcing them to grow a hardy annual plant that could protect the soil. They chose winter wheat, with no intention of harvesting an entire rooftop of the stuff.

“Then, we came back in the spring and lo and behold, there was a wheat field in the middle of downtown Chicago,” Meyer said. “I don’t think any of us were expecting to see a wheat field 40 feet up from one of the busiest intersections in Chicago.”

They enlisted Omni’s sister company, the Roof Crop (which Meyer also co-founded), as well as student volunteers, to harvest the 3,000 square feet of wheat by hand. A nearby miller donated his time and milled the harvested wheat into about 60 pounds of high-grade pastry flour. (He even rewarded the students with cookies.)

But besides the experience, Meyers was able to walk away with a clear ratio for how much wheat can be produced on a rooftop: for every 50 square feet of green roof that’s harvested, they’ll get about a pound of flour.

“Now that we have that metric, we can start looking at cities in completely different ways,” she said. “When building owners need just another incentive to do the thing that is great for a city -- bringing plants to a city -- this is one that can now be measured. We can say, ‘well, actually, if you chose to do wheat, and you harvested it for 20 years, every year you would get X pounds of flour, which could turn into X loaves of bread, or X bottles of beer."

Urban farming extends to food deserts... and real deserts

In South Phoenix, there isn’t a regular farmer’s market, and getting to a grocery store can mean a serious trek. That means the 4,711 residents in this part of town don’t have access to fresh fruit, vegetables, and other healthful whole foods. The area is officially designated a food desert by the USDA, but one project, called Spaces of Opportunity, is planning to change that.

With the help of several area nonprofits known as Cultivate South Phoenix, the Desert Botanical Garden, and a local elementary school, 18 vacant acres in the region are set to become working farmland and a community center for arts and healthy living programming.

“The whole point of the project is to keep as much healthy produce in the community as we possibly can,” says Nicolas de la Fuente, the project’s manager.

Eighteen acres is roughly the size of two New York City blocks, and 9.5 acres will be divided into “incubator farms.” Those spaces will be used as production farming space for people who want to make a serious living off the food they grow. Then, there’s 1.5 acres of community garden space, with plots that are about 4ft x 50ft.

“It’s funny when I say ‘community gardening,’” de la Fuente says. “At 1.5 acres it’s almost rural farming, it’s not like the boxes you see in other cities.”

There are currently four incubator farmers growing and selling winter vegetables, like spinach, collard greens, and kale, in the space. In the next few months, they will switch over to summer season crops: squash, peppers, tomatoes, and watermelons.

To water the crops, de la Fuente says they are planning to install a drip irrigation system. That will help the farmers conserve water, as well as substantially increase their output. Despite the desert conditions, the area was also once rich farmland, known for growing citrus and flowers. The Hohokam Canal system, which was one of the world’s largest canal systems, ran through the area, too.

“It’s actually a super rich agricultural center, that’s just been little by little developed with infill,” de la Fuente says. “So we aren’t necessarily doing anything new. We’re just essentially trying to bring back what was there and embrace the roots of the community.”

Spaces of Opportunity just received enough funding to fully connect to water and power, and their next endeavor is to build out the farmer’s market -- which will be the first in South Phoenix.

There’s still more work to do

Annie Novak has been the farm manager at Greenpoint’s Eagle Street Rooftop Farm in Brooklyn, NY since 2010, and she planted the first seeds on the farm with Ben Flanner in 2009. Since she became farm manager, she’s taught 100 people through an apprenticeship program who are looking to start an agriculture project of their own -- be it starting a small garden on top of their restaurant, or raising grass fed cattle in Texas.

“There’s a lot going on around the country, and internationally,” Novak says. “I feel like New York City leads with press, but I don’t know if we lead with acreage or initiative. Chicago, Detroit, San Francisco, LA to a degree, Milwaukee, Austin -- these are all places that have really successful urban farming programs. So we definitely are not alone.”

While farming is clearly a hard job, Novak says operating a farm in a city provides a lot of opportunities. They are close enough to their markets to meet buyers face to face. There are several restaurants seeking out fresh produce, and there are minimal transportation costs.

Besides the expansion of urban farming, one of the most vital changes she’s seen is that cities, and even the USDA, are beginning to support these initiatives. Urban farms are also getting included in conversations about the importance of green spaces in cities, and in particular how to protect them.

“There always seems to be an ebb and flow in the way cities embrace urban agriculture,” she says. “So I’m just trying to think ahead. What happens when everyone who started a rooftop farm when they were 22 decides they want to know what’s next?”

To protect the work that’s already been done, Novak hopes that cities like New York will start zoning some urban farms as agricultural property, which would ensure that the area remains a space for farming. In New York, there’s only one agriculturally zoned property: The Queens County Farm Museum, and it’s been a working farm since before New York City even existed.

“Why has nobody ever turned Central Park into a condo?” Novak asks from her bike, which is her sole form of transportation around the city. “Well, there are legal reasons why. But we could do the same thing for farms.”

A New Type of Farm is Letting Us Grow 100 Times More Food

Farming has been a cornerstone of civilization for a long time — even before sewer systems. As humans have evolved, so has farming. Thanks to drones, CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, and a host of other innovations, we have come farther than we would have ever thought possible — including reaching new heights with vertical farming

A New Type of Farm is Letting Us Grow 100 Times More Food

Farming has been a cornerstone of civilization for a long time — even before sewer systems. As humans have evolved, so has farming. Thanks to drones, CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, and a host of other innovations, we have come farther than we would have ever thought possible — including reaching new heights with vertical farming.

The pinnacle of modern agriculture can be found in Kearney, New Jersey at Bowery farms. The farming company claims it has the capacity to grow 100 times more per square foot than average industrial farms. This might be because the vertical farm calibrates “synthetic” parameters for its produce. Thanks to indoor LEDs that mimic natural sunlight, and nutrient-rich waterbeds that are easy to stack from floor to ceiling, Bowery is able to grow over 80 different types of produce. Bowery will begin selling its organic produce, — including popular salad fixings such as kale and arugula — in NYC come March 6th, at around $3.99 per five-ounce package.

Click to View Full Infographic

THE FUTURE OF FARMING

What’s so remarkable about Bowery is that it underscores the next generation of agriculture. While traditional farming is unlikely to disappear anytime soon, vertical farming showcases increased automation, reduced emissions, and all-around reduced costs.

Automated machines efficiently move water around the plants using a proprietary software known as FarmOS. The unique operating system adapts to new data, adjusting environmental conditions to the warehouse. Trays are optimally stacked to the ceiling and crops are produced year round, increasing the overall efficiency of the process.

Traditional farming reduces soil productivity, wastes water, can foster the growth of pesticide-resistant insects, and increases levels of greenhouse gases. The practice itself is quickly becoming unsustainable, as there’s less land available for farming: since the 1970s, almost 30 million acres have been lost to urbanization.

While traditional agricultural methods may endure, it might be prudent to acknowledge the global and local benefits of vertical farming with so many new companies cropping up.

How Millennials Will Forever Change America’s Farmlands

How Millennials Will Forever Change America’s Farmlands

March 21, 2017 | 3:21 PM ET

As Americans increasingly reject cheap, processed food and embrace high-quality, responsibly-sourced nutrition, hyper-local farming is having a moment.

Tiny plots on rooftops and small backyards are popping up all across America, particularly in urban areas that have never been associated with food production. These micro-farms aren’t meant to earn a profit or feed vast numbers of people, but they reflect the Millennial generation’s desire to forge a direct connection with the food they consume.

These efforts are an admirable manifestation of the mantra to think globally and act locally, but they miss the opportunity that is going on right now: the economics of branded local farms have changed, and technology in agriculture has led to a renaissance of independent American farming. Whether this means farming the traditional acreage of the Heartland or adapting to cutting-edge indoor farming methods, the result is the same: demand for real food is far outstripping supply. Highly-educated, entrepreneurial, and socially conscious young people have a great opportunity to think seriously about agriculture as a career.

On the surface, this advice sounds dubious, given the well-documented, decades-long decline of independent farming in America. Between 2007 and 2012, the number of active farmers in America dropped by 100,000 and the number of new farmers fell by more than 20%. Ironically, however, the titanic, faceless factory farms are barely eking out a profit. That often means that an independent 100-acre farm growing high-demand crops can be far more profitable than a 10,000-acre commodity farm growing corn that may end up getting wasted as ethanol.

The key to reviving America’s agricultural economy is casting aside the sentimental images we associate with farming – starting with what a farmer looks like. In recent years, many of the same technologies that have revolutionized the consumer world have fundamentally altered and improved the way we farm. Drones, satellites, autonomous tractors and robotics are now all at home on farms. As a result, tomorrow’s farms won’t just be part of the agricultural sector, they’ll also be part of the tech sector – and tomorrow’s farmers will look a whole lot like the coders who populate Silicon Valley…except with better tans.

The next assumption about farming we need to cast aside is what a farm looks like and where it will be found. The vast planting fields of America’s heartland are going to change by adjusting to grow real food with 21st century technology, but tomorrow’s farms will also be vertical and in or near our urban centers. By 2050, 70% of the global population will live in cities. As both a social imperative and a practical matter, it makes sense to grow food near these cities, rather than to waste time and resources delivering products from hundreds or even thousands of miles away.