Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

This Farm In A Shipping Container Is More Than Just A Source of Local Produce

This Farm In A Shipping Container Is More Than Just A Source of Local Produce

Mats von Quillfeldt prepares lettuce seeds in the repurposed shipping container. He is one of the students participating in the Mason LIFE program. (John McDonnell/The Washington Post)

By Sarah Larimer April 10

The repurposed shipping container is tucked in a parking lot, behind an office building and warehouse in Woodbridge, Va. From the outside, it might not look that special.

But on the inside . . . well.

Rows of seedlings poke out of trays that are nestled under a shiny workspace. More than 200 thin towers, packed with growing produce, stretch to the back. The lighting casts a purple glow, and visitors trade sneakers for shower slippers, to keep the space uncontaminated by the outside world.

The cramped container has a bit of a “Mad Scientist” vibe, or at least a “Mad Scientist Who Is Super Into Locally Grown Produce” vibe. This is Zeponic Farms, a hydroponic farm that is more than just a source of lettuce. The Northern Virginia farm also partners with a George Mason University program for people with developmental and intellectual disabilities.

“I’m really big on being a social entrepreneur,” said Zach Zepf, a founding partner of Zeponic Farms. “I think that if you’re going to start a product or a service, it should have something that’s meaningful.”

Lettuce grows in the converted shipping container in Woodbridge, Va. (John McDonnell/The Washington Post)

The farm, which grows lettuce, greens and herbs, works with Mason LIFE, a four-year program that offers educational and work experiences to a community with special needs. This partnership is still pretty new, but Zepf said he hopes for an expansion of the operation, and an expanded role for Mason LIFE.

“We bought this thing to be a life changer,” said Brenda Zepf, Zach’s mother. “Not only for our son but for other young adults like him.”

Brenda Zepf isn’t talking about Zach there. She’s talking about his brother, Nic, who has autism and other chronic health issues. The Zepf siblings would garden together in the back yard of their Springfield, Va., home, said Zach Zepf, growing kale, zucchini, tomatoes and chard.

“Not really lettuce, funny enough,” he said.

Now they have this farm, which is a really fancy upgrade. Nic, 23, is not a student in the Mason LIFE program, but Zach, who is 25, said he works there, too.

“It’s really special to be able to give my brother a career like this,” Zach Zepf said. “It’s an opportunity that he probably wouldn’t have unless someone created it for him.”

The LIFE program is not the farm’s only connection to the university. Lettuce grown at the farm is sold to Sodexo, the company that operates Mason’s campus dining services. It is served in a dining hall, said Caitlin Lundquist, Sodexo marketing manager.

Nic Zepf, left, Mats von Quillfeldt and Zach Zepf prepare lettuce seeds in a tray. (John McDonnell/The Washington Post)

“We sell them everything we have,” Zach Zepf said.

The farm started a year ago. Zepf said he hopes one day to bring it closer to the public university’s campus in Fairfax County. He would also like to grow the farm, either with another container or by moving to a larger facility, which could accommodate more people.

“Whether we get more containers, build our own containers or expand into a warehouse setting, the goal is to expand our role with Mason LIFE and eventually provide employment,” he wrote in an email, adding that it would require the farm to move closer, “which we will be doing.”

This is the first full semester that Mason LIFE has sent a student to the Zeponic Farms container, which is about 14 miles from Fairfax. That student, Mats von Quillfeldt, is a 20-year-old from Charlottesville who has autism.

One of the characteristics of von Quillfeldt’s autism is echolalia, which means he repeats words or phrases that others say. That doesn’t really matter at Zeponic Farms, where he works solo as he goes through the seeding process.

“Mats has got a very brilliant mind, and he’s got a lot going on in his mind,” said Andrew Hahn, a Mason LIFE employment coordinator. “But because of the echolalia, it makes it a little bit more difficult to have a conversation, for example. But Mats does exceptionally well in his academic program. It’s just a little bit of a communication barrier.”

When Mason LIFE started in 2002, there were about 12 other postsecondary programs like it in the nation. Now, there are about 250, said Heidi Graff, the program’s director.

“It’s really quite a movement within the field of education,” she said.

About 50 students participate in Mason LIFE, taking courses and developing skills through a work specialty. Students work in fields that include child development and pet grooming, she said, and some, like von Quillfeldt, are placed in farming roles.

“For our students, what makes farming in particular a good skill is the repetitive nature,” Hahn said. “For different plants, obviously, there’s different seasons to plant. But as far as the routine goes, for most things, it’s pretty typical. They can build an easy routine.”

That’s true. Hydroponics can seem like pretty scientific stuff, but really, all hydroponics has to work through is a simple, step-by-step guide. The tasks can be therapeutic, Hahn said.

“It’s good for our students to be able to see the work that they’re getting done,” he said. “And it keeps them motivated.”

Brenda Zepf said that she has taken her son Nic to a dining hall on Mason’s campus and shown him the salad bar. She told him the lettuce was his — that he had picked it himself.

“Kids with special needs and young adults with special needs have the right to work,” Brenda Zepf said. “They need to reach their full potential and have the same work opportunities as anybody else, and to have a true sense of purpose when they wake up in the morning, just like anybody else.”

Sarah Larimer is a general assignment reporter for the Washington Post.

Taking The field Out of The Farm: Growing Produce In Space Is Closer Than We Think

Taking The field Out of The Farm: Growing Produce In Space Is Closer Than We Think

If scientists have their way, astronauts will get their nutrients from the real thing, not pills

By Torah Kachur, CBC News

Posted: Apr 06, 2017 3:42 PM ET Last Updated: Apr 06, 2017 4:04 PM ET

Hydroponically grown fruits and vegetables could be grown in space sooner than we think (Frank Fox, Flickr)

Torah Kachur

Science Columnist

Torah Kachur is the syndicated science columnist for CBC Radio One. Torah received her PhD in molecular genetics from the University of Alberta and now teaches at the University of Alberta and MacEwan University. She's the co-creator of scienceinseconds.com.Also by the Author

Images from the 1950s show the people of the future — that's us — travelling in flying cars and living in biodomes, lush with fruits and vegetables for the taking. While that's not the case, it's not for lack of trying.

In reality, our ability to grow food in space is limited to a few plants on the International Space Station (ISS). NASA, along with many other space agencies around the world, has been trying to change that for almost 70 years, and the advances keep coming.

A new paper published in the journal Open Agriculture has traced the history of growing food in space from its beginnings in the 1950s to today, and paves the way for colonizing even the distant reaches of space with autonomous food supply.

Why is it so hard to grow food in space?

There are really lots of reasons, but the biggest reason is actually light. Even though the sun is burning bright out there in outer space, there are places that don't experience the same diurnal daylight like we do here on Earth. Plants are a lot like people: they're used to the typical 24-hour days of alternating light and dark; in fact, they have a molecular clock timed to it. If you were to find yourself on the moon, with almost two straight weeks of daylight and no night at all, followed by two straight weeks of darkness with no light, your body wouldn't know how to react. It's the same for plants.

That was the first problem facing scientists looking to grow food off Earth, which led to an invention that we use every single day: LEDs. I spoke with Ray Wheeler, a NASA Exploration Research and Technology scientist at the Kennedy Space Center and the author of the paper.

"The patent for using LEDs to grow plants was developed through NASA-funded research, and this was in 1990, quite a while ago," he said. "At that time LEDs weren't all that efficient, but they fit a niche for use in space plant chambers that are typically very small. LEDs have continued to improve remarkably as a technology, but it was really their use for space application to grow plants that kind of brought this up to the forefront."

So, just when you think "what has space research done for me?" they go and make LEDs the invention they are today.

Once the light is figured out, what do the various space agencies want to grow?

The goal is to give the astronauts and cosmonauts fresh foods with more bio-available nutrients to keep them healthier longer. They could and do take supplements for their nutrition, but there is something about biting into a nice ripe tomato to get your vitamin C instead of just taking a pill. Plus, you absorb a lot more nutrients coming from something living than something compressed down into a pill.

It's also more than just nutrients: there is a need to keep some level of normalcy or Earth-like living out there in space: tending, caring and rearing food for yourself, and the pleasure taken by the simple act of eating, is positive for anyone's mental health, let alone someone stranded on Mars.

For shorter missions, small supplemental fruit and vegetables are the goal, but obviously longer missions and more permanent space settlements will require staple crops like wheat, other grains and legumes.

Chuck Spern, a project engineer with Vencore on the Engineering Services Contract, removes a base tray containing zinnias from a controlled environment chamber in the Space Station Processing Facility at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Flowering plants will help scientists learn more about growing crops for deep-space missions and NASA’s journey to Mars. (NASA/Bill White)

What do growth chambers for space look like?

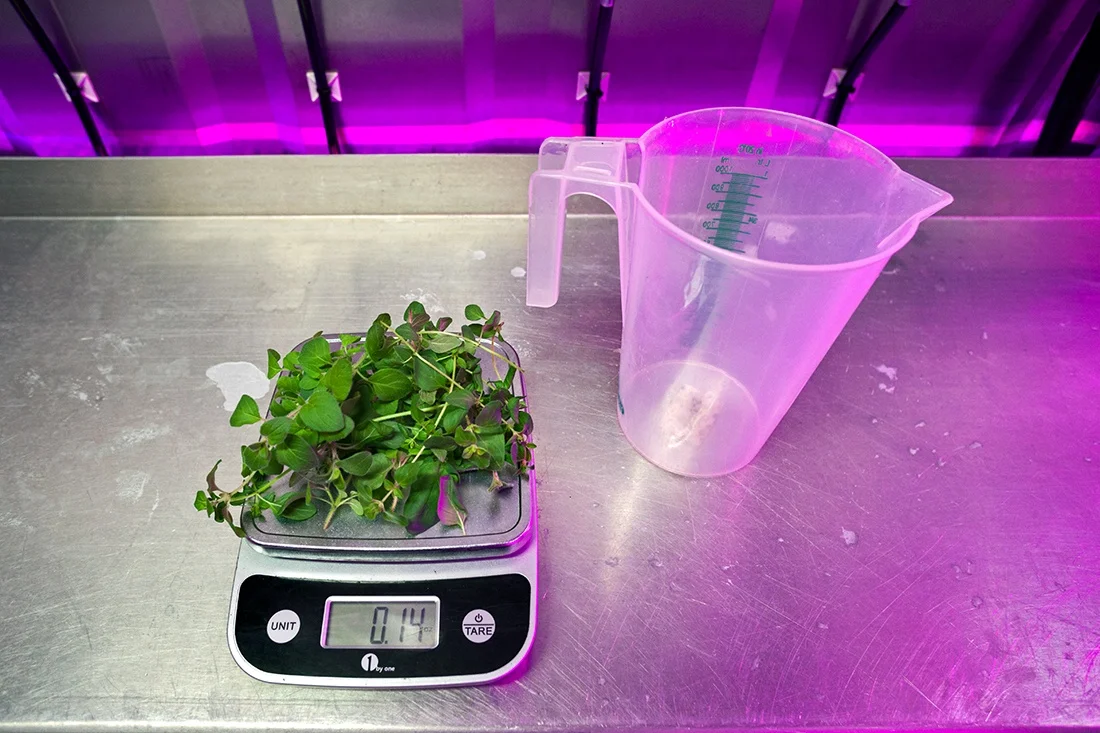

Generally pretty small at this point. The ISS has a 0.15-square-metre growth chamber. Clearly not enough to feed them, but enough to look at the feasibility of upscaling it.

The reality is the growth chambers that may one day exist on the moon or on Mars aren't that much different from what we already see on Earth. In particular, hydroponics have been a huge focus of space-farmers.

Wheeler explains: "The use of re-circulating hydroponics to conserve your water and nutrients so you don't discharge them into the environment — and you save water and you recycle the nutrients very efficiently — this is something that we have to do in space systems when we'll be setting them up. But it's very applicable to Earth settings as well. We're always under pressure to preserve water and nutrients and minimize environmental impacts."

So farming in space is going to have the same limitations as hydroponic operations here on land, complete with the need for power, closed air systems and the space to grow. Movies like The Martian really didn't do a bad job showing what space agriculture will likely look like one day.

How tough will space be on plants?

That's one thing that is going to be really important to understand, and there simply hasn't been enough work done on it yet. Low-gravity experiments have been done on Earth, and certain plants — like tomatoes — tolerate low-gravity situations quite well. However, the bigger problem up in space is the radiation. Plants are living organisms with DNA just like ours, and we know that radiation is problematic for DNA: it can cause all sorts of mutations very quickly and do all kinds of damage to the cells.

A question is: Can we conventionally breed or genetically engineer staple crops for resistance or tolerance for radiation without losing yields?

The next frontier in space agriculture is really not improving the tech, but improving the life that will live in that tech.

I'll give the last word to NASA scientist Ray Wheeler:

"The approach to date has been largely to try and continue to improve the engineering and the environmental management to accommodate the biology, and we're kind of getting to some limits here in terms of how far you can go with the engineering and the hardware. Now we really need to think about can we adapt the biology to fit the constraints of the environment, and I think the answer to that is yes."

5 In Home Growing Questions With Bjorn Dawson of Grobo

Bjorn Dawson is the CEO and co-founder of Grobo. They’ve developed an easy-to-use home growing system that takes the guesswork out of successfully growing small crops of high quality food and legal cannabis. Ahead of his presentation at Indoor Ag-Con in May, we asked him five questions about in home growing

5 In Home Growing Questions With Bjorn Dawson of Grobo

Bjorn Dawson is the CEO and co-founder of Grobo. They’ve developed an easy-to-use home growing system that takes the guesswork out of successfully growing small crops of high quality food and legal cannabis. Ahead of his presentation at Indoor Ag-Con in May, we asked him five questions about in home growing.

1. What’s your inspiration for Grobo? How long has it taken you to get to a viable product?

A few years ago I began growing fruits and vegetables outside and quickly fell in love with how delicious home grown food tastes. Tomatoes bursting with flavour, juicy watermelon, and crunchy carrots had me hooked on the idea of growing my own food, but our long Canadian winters make that nearly impossible. After not finding any good systems for automated growing that would fit within my home, Grobo was founded to allow everyone to easily grow plants indoors, all year long.

2. How is your Grobo One grow box different from the myriad other in home systems on the market?

In short, we focus on the plant and on the user. The first product we developed, but never launched, was called Grobo Pods and was designed to help the everyday user grow their own greens in a system that costs less than $200. To hit this price point required technical sacrifices that resulted in smaller yields and longer grow times. Throughout our development, this low-end market quickly became flooded with inefficient systems… so we went the other way: high-end and high-tech. Grobo One grow box is the best home growing system because it is extremely simple for anyone to use and always provides your plants with exactly the light, water, and nutrients they need. For example, we are the only company using far red LEDs to simulate the sunset which helps plants grow almost 10% faster.

3. In home systems get a lot of flack for being more jewelry than farm. How do you think about ensuring that your customer gets value from Grobo One?

It’s important to remember that this technology is still new and there is lots of work ahead of us to create in-home farms. Grobo One uses technology such as our 8 colour LED spectrum and precise nutrient dosing to ensure that plants grow as quickly as possible. By automating the growing cycles, we can actually save users hours each week because they no longer have to adjust the pH of their water, add nutrients, or even design their growing system to begin with. Although the economics change depending on what you grow, we truly believe that the quality of the end product will have people hooked on growing their own food.

4. You were a part of a hardware accelerator – HAX – in China. How was that experience?

From January to May 2016 our entire team was at HAX living in Shenzhen, China and it was a phenomenal experience. Shenzhen produces a mind boggling number of consumer products each year, and being at the heart of manufacturing taught us how to build a product at scale and on budget. More importantly, the Chinese mindset is to move quickly, and that is something we have taken back to our office in Canada. We now have the equipment to prototype most parts of a Grobo One in-house in under 24 hours, which allows us to constantly innovate and improve upon our products.

5. What crop would you love to see grown in a Grobo system that isn’t yet viable? When will that happen?

Personally I can’t wait to grow strawberries in my Grobo One because the squirrels have been the lucky ones to enjoy them over the past few years. We have already had success with cannabis, kale, tomatoes, peppers and many other plants, but I still can’t wait to see the wide variety of plants that our customers will grow. As shipping begins this summer, we have customers wanting to grow everything from cucumber to cauliflower to cacti and I’m excited to see it all!

SEE BJORN SPEAK AT THE 5TH ANNUAL INDOOR AG-CON ON MAY 3-4, 2017

You Want Fresh? Dallas' Central Market is Growing Salad Behind The Store

You Want Fresh? Dallas' Central Market is Growing Salad Behind The Store

April 10, 2017

Written by: Maria Halkias

Fresh is a word that’s used loosely in the grocery business.

To the consumer, everything in the produce section is fresh. But most fruits and vegetables are picked five to 21 days earlier to make it to your neighborhood grocery store.

Central Market wants to redefine fresh when it comes to salad greens and herbs. It also wants to make available to local chefs and foodies specialty items not grown in Texas like watermelon radishes or wasabi arugula.

And it wants to be both the retailer and the farmer with its own store-grown produce.

The Dallas-based specialty food division of H-E-B has cooked up an idea to turn fresh on its head with leafy greens and butter lettuce still attached to the roots and technically still alive.

Beginning in May, the store at Lovers Lane and Greenville Avenue in Dallas will have a crop of about half a dozen varieties of salad greens ready for customers to purchase.

The greens will be harvested just a few dozen steps from the store’s produce shelves.

They’re being grown out back, behind the store in a vertical farm inside a retrofitted 53-foot long shipping container. Inside, four levels of crops are growing under magenta and other color lights. In this controlled environment, there’s no need for pesticides and no worries of a traditional farm or greenhouse that it’s been too cloudy outside.

Central Market has been working on the idea for about a year with two local partners -- Bedford-based Hort Americas and Dallas-based CEA Advisors LLC -- in the blossoming vertical and container farming business.

Plants are harvested inside a vertical farm in the back of the Central Market store in Dallas, Thursday, April 6, 2017. Central Market is trying out indoor growing, and the crops will be sold in the store beginning in May. (Jae S. Lee/The Dallas Morning News)

“We’re the first grocery store to own and operate our own container farm onsite,” said Chris Bostad, director of procurement, merchandising and marketing for Central Market.

There’s a Whole Foods Market store in Brooklyn, New York with a greenhouse built on the roof, but it’s operated by a supplier, urban farmer Gotham Greens.

The difference, Bostad said, is that “we can grow whatever our customers want versus someone who is trying to figure out how to cut corners and make a profit.”

Central Market’s new venture is starting out with the one Dallas store, said Marty Mika, Central Market’s business development manager for produce. “But we’ll see what the customer wants. We can do more.”

This has been Mika’s project. He’s itching to bring in seeds from France and other far off places, but for now, he said,“We’re starting simple.” The initial crop included red and green leafy lettuce, a butter lettuce, spring mix, regular basil, Thai basil and wasabi arugula.

The cost will be similar to other produce in the store, Bostad said.

Why go to so much trouble? Why bother with lighting and water systems and temperature controls in what’s become a high-tech farming industry?

“Taste,” Mika said. “Fresh tastes better.”

And the company wants to be more responsive to chefs who want to reproduce recipes but don’t have ingredients like basil leaves grown in Italy that are wide enough to use as wraps.

Tyler Baras, special project manager for Hort Americas, said with the control that comes with indoor farming there are a lot of ways to change the lighting, for example, and end up with different tastes and shades of red or green leafy lettuce.

Butter lettuce is harvested inside a vertical farm in the back of the Central Market store in Dallas, Thursday, April 6, 2017. Central Market is trying out indoor growing, and the crops will be sold in the store beginning in May. (Jae S. Lee/The Dallas Morning News)

Staff Photographer

In Japan, controlled environment container farms are reducing the potassium levels, which is believed to be better for diabetics, Baras said. “We can increase the vitamin content by controlling the light color.”

At Central Market, the produce will be sold as a live plant with roots still in what the industry calls “soilless media.”

Central Market’s crops are growing in a variety called stone wool, which is rocks that are melted and blown into fibers, said Chris Higgins, co-owner of Hort Americas. The company is teaching store staff how to tend to the vertical farm and supplying it with fertilizer and other equipment.

“Because the rocks have gone through a heating process, it’s an inert foundation for the roots. There’s nothing good or bad in there,” Higgins said.

Farmers spend a lot of time and money making sure their soil is ready, he said. “The agricultural community chases the sun and is at the mercy of Mother Nature. We figure out the perfect time in California for a crop and duplicate it.”

Growers Rebecca Jin (left) and Christopher Pineau tend to plants inside a vertical farm in the back of the Central Market grocery store in Dallas, Thursday, April 6, 2017. Central Market is trying out indoor growing, and the crops will be sold in the store beginning in May. (Jae S. Lee/The Dallas Morning News) Staff Photographer

He called it a highly secure food source and in many ways a level beyond organic since there are no pesticides and nutrients are water delivered.

Glenn Behrman, owner of CEA Advisors, supplied the container and has worked on the controlled environment for several years with researchers at Texas A&M.

“Technology has advanced so that a retailer can safely grow food. Three to five years ago, we couldn’t have built this thing,” Behrman said.

Mika and Bostad said they also likes the sustainability features of not having trucks transport the produce and very little water used in vertical farming. They believe the demand is there as tastes have changed and become more sophisticated over the years.

The government didn’t even keep leafy and romaine lettuce stats until 1985.

U.S. per capita use of iceberg, that hardy, easy to transport head of lettuce, peaked in 1989. Around the same time, Fresh Express says it created the first ready-to-eat packaged garden salad in a bag and leafy and romaine lettuce popularity grew.

In 2015, the U.S. per capita consumption of lettuce was 24.6 pounds, 13.5 pounds of leafy and romaine and 11 pounds of iceberg.

No Dirt, No Problem: A Revolution In Growing

No Dirt, No Problem: A Revolution In Growing

- BY KELLY ARDIS kardis@bakersfield.com

- Apr 7, 2017 Updated Apr 7, 2017

Henry A. Barrios / The Californian

Shari Rightmer has started a new business in Taft called Up Cycle Aquaponics. Organic produce is grown using fish-produced nutrient-rich water; microbes convert the water to fertilizer for plants, which are grown in small pods. “Most people really have to scratch and sniff to really understand it,” Rightmer said. “That’s (one) reason it was so important to have a showroom.”

Courtesy of EcoCentric Farms

Shanta Jackson sells kale and other produce grown at EcoCentric Farms in Bakersfield. She and her wife, Kimberly, farm using aquaponics, a method of farming that uses a symbiotic relationship between the produce and the fish who help grow it. The Jacksons started EcoCentric in 2011 and made it their full-time job last year.

Shari Rightmer shows one of the first plants growing in her storefront aquaponics farm. Unlike produce bought at a chain grocery store, people can know exactly where and how their Up Cycle produce was grown. “Here, we have trust through transparency. It’s all right here.”

Henry A. Barrios / The Californian

Henry A. Barrios / The Californian

Shari Rightmer holds one of the small pods with organic clay pebbles that help distribute nutrients to plants in an aquaponics garden. Aquaponics has many benefits, like produce that grows faster and with less water. “It’s easier to ask ‘What’s the downside?’” Rightmer said over the phone days before the interview. “It’s zero.”

Courtesy of EcoCentric Farms

In aquaponics, produce grows in little pods without dirt, as in this photo of a plant grown at EcoCentric Farms in Bakersfield. It is one of many pods that sit in a vertical column. In aquaponics, the water that is used to hydrate these plants is a pond with fish in it. The fish fertilize the produce, and the produce filters the water back to the fish.

Henry A. Barrios / The Californian

A poster encourages healthy eating in Shari Rightmer’s office at Up Cycle Aquaponics.

Henry A. Barrios / The Californian

Rows of tubes hold hundreds of pods that will each grow organic produce in Shari Rightmer’s storefront organic farm, Up Cycle Aquaponics in Taft. “When I came across aquaponics doing research four years ago, I said ‘This is it. I don’t know how but I’m going to do this,’” she remembered. “I knew it was meant to be an offering to everyone, not just me.”

Henry A. Barrios / The Californian

With more than 20 pods in each tube, the potential to grow organic produce such as tomatoes, microgreens, leafy greens and herbs in Shari Rightmer’s storefront farm in Taft is tremendous. “Once we have the koi fish, this will be popping,” Rightmer said.

Henry A. Barrios / The Californian

Shari Rightmer outside her new business, Up Cycle Aquaponics in Taft. The business is a storefront farm that uses aquaponics to grow organic produce. “People stop and drive by; they look in the windows, like ‘What in the world?’” Rightmer said. “Once the green shows up, they’ll be blown away.”

For the moment, Up Cycle Aquaponics is nearly all white. But that changes by the day, with shoots of green sprouting here and there, hinting at the leafy oasis Shari Rightmer hopes is still to come. Orange and black koi fish also add color, breaking up the stark white monochrome that imparts the vague impression of a laboratory.

Up Cycle is an aquaponics farm, a concept of growing produce that depends on a symbiotic relationship between plants, fish and the elements. A large part of Rightmer's vision for the Taft start-up is about opening it up to the public. She knows plenty of people won't get aquaponics until they can see it for themselves.

Now they can.

"Most people really have to scratch and sniff to really understand it," Rightmer said. "That's (one) reason it was so important to have a showroom."

Walking through the small solarium that has been built onto her home, Rightmer explained aquaponics in part by pointing out her all-white outfit: Since her plants don't grow in dirt, Rightmer can tend the crops without worrying about getting her clothes dirty. Growing food without dirt might be a hard thing for people to wrap their brains around, but that's where the other key part of aquaponics comes in: fish.

"I'm just going to say it: Everything grows in poop," said Rightmer, who will turn 60 in a few days. "You've just got to pick the poop your food is grown in."

Unlike the fertilizer that comes from warm-blooded animals, what comes from a cold-blooded animal like a fish is less likely to have bacteria like salmonella or e. coli, and the food lasts longer, Rightmer said.

As the fish help the plants grow, the plants help the fish by acting as a filter. In the columns, each plant grows in a small pot with organic clay, getting water from the pond via a tube that goes to the top of each column and trickles down to each plant before the last drops reach the lava rocks at the bottom, becoming a biofilter for the fish.

Though the hard work of building Up Cycle is over, now it's time to be patient. Rightmer had to wait for the added nutrients in the pond's water to balance to make it perfect for the koi fish that will live there. Then it will be time to wait for the leafy greens to grow.

"Once we have the koi fish, this will be popping," Rightmer said from inside the solarium last month.

An 'offering'

Rightmer first heard of aquaponics about four years ago and opened her doors to the public in late February after about a year of planning. She was hooked from the start because aquaponics combines her three loves: food, gardening and cutting-edge technology.

"When I came across aquaponics doing research four years ago, I said 'This is it. I don't know how but I'm going to do this,'" she remembered. "I knew it was meant to be an offering to everyone, not just me."

Rightmer's "offering" is a chance for the community to see a new way of growing food and the opportunity to eat and cook with what she believes is some of the best produce around. Since the fish are less likely to introduce bad bacteria and the temperature-controlled room where the veggies grow is air-filtered, the result is super-pure produce, she said.

Growing in the showroom are baby springs, microgreens and lettuce, all of which will grow in less than a month once the water is ready. In a shed behind the house is another aquaponic set-up where Rightmer is growing tomatoes, though that area is not open to the public. She didn't yet know specific prices for the greens and tomatoes but said they will be around farmers market prices. Anyone can walk into Up Cycle to buy produce, whether it's a single head of lettuce for a family dinner or several for a chef to use at a restaurant.

Aquaponics uses 10 percent of the water typically used for similar plants grown in soil, and aquaponic produce grows two to three times faster than in soil and three times larger in less space than in soil, Rightmer said, citing a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Each column in the three rows of aquaponic tubes holds more than 20 individual plants. There are nearly 2,000 plants at Up Cycle.

"It's easier to ask 'What's the downside?'" Rightmer said. "It's zero."

Just about anything can grow in aquaponics, other than plants like blueberries, whose acids or oils are harmful to the fish. Though many have wondered, possibly with a raised eyebrow, if Rightmer was growing marijuana, she said she couldn't grow it with aquaponics even if she wanted to because of the oil in THC. They might be confusing aquaponics for hydroponics, a similar soil-free farming technique that, yes, some people use to grow marijuana. Unlike aquaponics, hydroponics doesn't involve fish.

"The concept is simple but it has such a beautiful balance," she said. "If anything is off, it throws the whole thing off."

There are five aquaponic farms from Kern County to San Diego, she said, but the showroom aspect of her business is a first in the country, as far as she knows. Usually aquaponic farms are not open to the public.

At Up Cycle, produce is sold on a first-come, first-served basis. If there ever is unsold produce, Rightmer will dehydrate and sell them for soup mixes or spices or freeze-dry them.

Not the only fish in the pond

For insight and advice into aquaponics, Rightmer didn't have to look far. Essential to her starting Up Cycle were Kimberly Jackson and her wife, Shanta, who have been running their own aquaponic business, EcoCentric Farms, since 2011. Since Aquaponics is still so new, the Jacksons learned primarily through trial and error, reaching out online to other DIY aquaponic farmers for tips. Now the couple have become local experts on all things aquaponics. They built the columns and structures where Rightmer will grow her produce, and they're happy to help anyone who might want their own aquaponic set-up, be it for a new business or a backyard.

The Jacksons have found from experience that all the praise Rightmer gives aquaponics is true: the kale, arugula, chard and spinach EcoCentric produces is long-lasting, fast-growing and, based on how well it all sells at farmers markets, great-tasting.

"A lot of our customers say the produce just lasts so much longer because it’s picked the day before market," Kim Jackson said.

In the last year, the Jacksons have even been able to make EcoCentric Farms their full-time job. They sell their produce at local farmers markets on the weekends and their kale chips are available at Sully's convenience stores. It was Kim Jackson's mother, Deborah Jackson, who funded most of the start-up expenses, though Jackson declined to share how much. Today, anyone can support the farm with a loan through kiva.org.

"For some reason, we knew it would work," said Jackson, 31. "We kept seeing signs of improvement that encouraged us to keep going with it."

Aquaponics, in vertical structures like Up Cycle and EcoCentric or horizontal form like the system in place at Epcot in Orlando, is "extremely scalable," Jackson said. Because of its adjustability in size and scale, anyone can start an aquaponic farm with a little help and insight from those in the know. The science involved is complex to explain but simple in practice — essentially, aquaponic farmers need to get the water just right for the fish and plants. That can take time, so patience is important.

"Definitely (don't) rush it," Jackson said. "Establishing a really healthy nitrate cycle is the basis of the whole thing. You see the fish and see the plants and think that’s most important, but the beneficial bacteria is doing all the heavy lifting."

Sharing the vision

Because aquaponics requires a bit of explaining, the hardest part of starting Up Cycle might have been convincing the city of Taft and other entities to get on board. It was hard to get a loan at first, Rightmer said, but eventually everything came together, with the help of the Small Business Development Center, the United States Department of Agriculture, architects, designers and, of course, EcoCentric Farms.

"Each entity that came in truly got the vision," Rightmer said. "The city of Taft approved and that was huge, for them to trust me."

For the new front of the house and the aquaponic equipment, Up Cycle took an investment of about $150,000 to $175,000, Rightmer said.

Though she's only just put the finishing touches on Up Cycle, Rightmer is already thinking to the future. She doesn't know how or what exactly, but she'd like to expand the business to be able to grow more produce. She's also open to franchising, she said. But at the moment, it's a one-woman operation.

At the grand opening on Feb. 25, Rightmer got to show off the completion of her vision and serve guests some food grown through aquaponics, though not from Up Cycle. She said many of the guests were more excited about the food than the building, which is still a win for aquaponics.

Before its official opening, the people of Taft took notice of the construction going on at 610 Kern St., whether they knew what it was or not. Now the curious can come inside and see for themselves.

"People stop and drive by; they look in the windows, like 'What in the world?'" Rightmer said. "Once the green shows up, they'll be blown away."

While working on Up Cycle, Rightmer will continue her nonprofit Shar-On Corporation, which helps people transitioning through life changes by offering classes and free meals. Rightmer herself was homeless for about two years following her husband's 2007 death. She spent around four months at the Bakersfield Homeless Center. Now back on her feet and already giving back through her nonprofit, Rightmer is eager to share her business with the community.

What she's giving to the community this time is an opportunity to learn and the chance to buy some great fresh produce. It won't be like shopping in a grocery story. Rightmer remembered a time she was once at a chain grocery store and picked up a head of lettuce.

"I asked myself, 'What do I really know about this lettuce I'm about to put in my body?'" she said. "Here, we have trust through transparency. It's all right here."

Kelly Ardis can be reached at 661-395-7660. Follow her on Twitter at @TBCKellyArdis.

Indoor Growing Is ‘Bringing Back Failed Varieties’

Indoor Growing Is ‘Bringing Back Failed Varieties’

Urban farms are allowing Rijk Zwaan to grow varieties that fell short in past crop trials due to weak disease resistance

Indoor growing with LEDs is allowing salad breeders to bring back high-performing varieties that didn't have strong enough disease resistance in crop trials, a city farming expert has revealed.

Indoor growing at facilities such as GrowUp Urban Farms in London has allowed plant breeder Rijk Zwaan to reinstate certain salad varieties and boost product quality and consistency, said Philips’ programme manager for city farming, Roel Jansson.

“Growing in indoor climate cells means there are no pests, no weather changes, no bugs,” he said. “Everything that was developed by Rijk Zwaan in previous years but maybe didn’t have enough disease resistance can be used indoors because here we don’t have disease. We can get better taste, better colouration, faster growth.”

Philips has a programme with fellow Dutch company Rijk Zwaan to screen different varieties to find out which are best for indoor growing and which LED light spectrum they respond best to.

While he accepts that indoor growing will never fully replace traditional salad outdoors or in polytunnels, he sees big potential for vertical growing in fresh-cut pre-packed salads.

“Indoor growing is the future for growing processed produce like fresh-cut pre-packed salads because you can grow bug-free and with stable nitrates,” he said. “You can predict shelf life, texture, quality because you always get the same product.”

In wholehead lettuce, Janssen believes opportunities are more limited since consumers are already used to washing the product before eating it.

“In Europe we could produce a full head of lettuce that you don’t need to wash anymore,” he said, “but people are used to washing it anyway so the added value would probably be limited.”

He added: “There is already a market [for wholehead lettuce you don’t have to wash] in North America and Asia Pacific but in countries with really high horticultural standards like the UK, Netherlands and Scandinavia I don’t think we would easily replace a greenhouse.”

Produce from indoor farms is typically twice the price, costing around the same as organic produce, however this could reduce in future as LEDs become cheaper and more efficient and higher-yielding varieties are developed.

Tiger Corner Farms Produces Full-Scale, Aeroponic Crops In Recycled Shipping Containers

Tiger Corner Farms Produces Full-Scale, Aeroponic Crops In Recycled Shipping Containers

The Future of Farming

Tiger staff: Robert Phillips, Matt Daniels, Evan Aluise, Eric Shuler, and Stefanie Swackhamer

They don't sound like farmers. With a team comprised of a former high school Latin teacher, a systems engineer, a mechanical engineer, and two technicians, they sound more like characters on the Big Bang Theory than a group of land-tillers. And while Tiger Corner Farms general manager Stefanie Swackhamer will concede that, "we're probably the biggest bunch of nerds you'll ever meet," she also assures us that looks can be deceiving.

The genesis

It all started on a whim. Swackhamer's father, Don Taylor, former chief technology officer at Benefitfocus and owner of software development company Boxcar Central, heard about aeroponic farming from a friend in Pennsylvania. Not to be confused with hyrdoponics, aeroponics is the process of growing plants in an air or mist environment without the use of soil. Hyrdoponics, a subset of hydroculture, also forgoes soil, but instead of mist uses a water solvent and mineral solutions. While many would be averse to tackling one of the 'ponics sans an agricultural background, Taylor was simply fascinated by the technology, plus he knew that he could use his company's software as part of the growing process. Starting to sound a little like The Martian? Spoiler: Matt Damon doesn't appear, but the rest is pretty damn close.

Taylor solicited help from Swackhamer in establishing their Summerville "farm" — picture a handful of shipping containers situated a few hundred yards behind a nondescript rancher (Boxcar Central headquarters) off Summerville's main drag. Not exactly the halcyon landscape of our farmer forebearers, but a farm nonetheless. The shipping containers are recycled from Carolina Mobile Storage, also located in Summerville; one container serves as an office-like space, another houses tools, and then there are the farms, 320-square-foot contained environments growing upwards of 4,000 plants at a time. The plants receive no direct sunlight, and they are not gently tucked into the Earth's rich soil, but they're not subjected to mercurial Mother Nature, either. With the right LED lights, CO2 levels, and proper mix of nutrients, Tiger Corner Farms can grow a full head of lettuce — a beautiful, perfectly formed specimen — in approximately 30 days. For comparison, growing a full head of lettuce in the ground can take any where from 55 to 70 days. Now, try telling them they're not farmers.

The nitty gritty

Swackhamer, the former Latin teacher, is at the helm of day-to-day operations. Also lacking a traditional ag background, Swackhamer is here, farming, for a lot of reasons; when she was a teacher at Stall High School in North Charleston, she says "those kids didn't know what a good head of lettuce looks like. To know we're part of the solution of [food deserts] and not part of the problem, that's huge." On our farm visit, Matt Daniels, the team's systems engineer, is finalizing the lighting in one of the containers. A couple of years ago Daniels and a friend started Vertical Roots, a small-scale hydroponics operation. He connected with Tiger Corner Farms through GrowFood Carolina. GrowFood's general manager Sara Clow was working with both Daniels and TCF separately when she saw the opportunity for a serendipitous pairing. Clow says that she asked the two companies if they would be OK working together: "It's been a really neat process to watch. One of the reasons that Stefanie and her dad got into it was for charity, and I love that [the companies] ended up collaborating instead of competing."

Upon entering the "farm" we are asked to put on special glasses because of the LED lights; the purple haze may transport you to a Jimi Hendrix concert, but the 300 feet of hanging plant panels before you will remind you that you are in fact inside a shipping container turned farm. To the right is a propagation table where the growing process begins; atop the table is a computer, the brains of the entire operation. The software — the code was developed from scratch at Boxcar Central — keeps track of everything from "seed to sale." The propagation table holds about 2,800 plants per cycle. After 10 days in the table, the plants are transported to the hanging panels. A holding tank, hanging overhead to the left, pumps the nutrients through a chiller to keep the water temperature consistent. The resulting mist is sprayed from hundreds of tiny sprayers onto the plants' roots three to four seconds every 10 minutes. "At the end of the day," says Swackhamer, "a lot of what we're doing is an analytics project. We're trying to get the best possible produce in the shortest amount of time." As a former teacher, Swackhamer says she loves this problem-solving, data-driven approach to growing. And the best part? TCF can share this technology with other farmers.

"The end goal," says Swackhamer, "is that a customer will ask us, 'OK, how do we grow blank?' and we can tell them 'here's the framework, if you want bok choy you need to use this light integral, for arugula set these CO2 levels.' We're taking the automation of an algorithm and breaking it down." Sound complex? Well, it is, at first, but TCF wants to work out all the kinks and provide customers with a product that is pretty straightforward to use, "my goal is for people to understand that it's not that complicated," says Swackhamer. "At the end of the day, it's still growing, they are plants that need light, water, and nutrients."

Tiger Corner Farms operates in a handful of cargo containers in Summerville

Aeroponics in action

So who is the customer base for these atypical farms? At $85,000 a pop, the containers aren't cheap, but, says Swackhamer, they really aren't that pricey when you look at most farm equipment. "This is a turnkey system," she says, "plus, there are endless grant opportunities, whether it be for STEM, sustainability ... so many categories that this could fall under. When we come across someone who we think is the perfect fit, we let them know we can help them figure it out. Money is never the problem. Plan and execution is the only real issue. And it's not just a piece of equipment, it's a whole farm."

The Citadel has already purchased one of the farms; it will be run by cadets as part of a sustainability/environmental studies minor — working in the farm will be an optional Capstone project. The resulting produce will go into the mess hall's salad bar. Another farm is being shipped to a family in Athens, Ga. who will use it for a roadside stand. "We've had all kinds of inquiries," says Swackhamer, "and we're just rolling with it."

Daniels' has his own Vertical Roots farm onsite, and once he has a consistent framework in place, he plans to start selling boutique plants direct to chef. Should local farmers be worried about competition in the kitchen? No, says Clow: "Chefs are pretty loyal to the farmers they use. I think TCF has the ability to hit other markets that folks aren't hitting now, and chefs will make room for the TCF products because they will be unique."

While venturing into this new market may be high-risk (this is, at least according to TCF and GrowFood, one of the few full-scale aeroponic farms in a region populated by pretty successful traditional farms), Swackhamer says there are so many safety nets in place when it comes to potentially interested yet hesitant customers. "While a traditional farmer might struggle attaining GAP (Good Agricultural Practices) certification — the certification is key, allowing you to sell anywhere, anytime — our environment is so controlled because of what the software collects, we know where the seed came from. So, God forbid there were some sort of outbreak, we'd be able to trace back to the exact seed." And, while traditional farms inevitably waste water, TCF actually makes water-harvesting condensation from the AC unit.

Altruistic farming

While the technology TCF is creating and using is both groundbreaking and fascinating by any standards, it's the charitable bent of the company that's the linchpin, says Swackhamer: "Our mission is to get really good food into the community. We want to be a more self-sustaining community. Even though we're techy and some of what we do sounds so complex, at the end of the day we want to grow good food and get it into the hands of as many people as possible."

TCF has one farm, the community container, that is used solely to grow food for donations to local nonprofits, most recently including about six harvests worth of lettuce, spinach, kale, collard greens, and herbs for the Sea Island Hunger Awareness Foundation; the rest is donated to the South Carolina Aquarium to feed the aquatic residents. "It's such an important part of what we do," says Swackhamer, "especially in Charleston with the lack of available land, this is such a good alternative."

In addition to funneling their product free of charge back into the community, TCF will also be bringing on an apprentice this May through Lowcountry Local First's Growing New Farmers Program. "With the area farmers getting older, it's important to get a younger group of people involved with farming," says Swackhamer. Brian Wheat, who runs the LLF's New Farmers Program, agrees. Through the grapevine, Wheat heard about this shipping container farm out in Summerville and had to see it for himself. "I did a site visit with Stefanie and we are both former educators so we understand the value of that and how these containers could be applied in a school setting," says Wheat. Wheat, impressed by the farms and by Swackhamer's genuine enthusiasm about the company and its educational component, decided to incorporate TCF as a mentor for the New Farmers Program. The program, run through the school of professional studies at College of Charleston, places participants with a farm that matches their interests for six months of hands-on, experiential learning. "The aging farmer population is not being replaced," says Wheat. This program provides a new generation with the tools to tackle the challenges of farming in a changing world. And Wheat thinks that students will be particularly interested in the "super specialized and streamlined" concept that TCF is working on, especially those who aren't attracted to the "old vision of farming." There are people who feel a need to contribute to the food system or their neighborhood in some way, says Wheat, and an apprenticeship with one of these progressive farm models allows us to expand the definition of "farmer," reaching a wider and more varied group of young minds.

The future is now

So what's next for the less than a year old company? Swackhamer says Tiger Corner Farms is in the process of building a warehouse off of Clements Ferry Road so that they will have a bigger facility than their current backyard space. Even though the company seems to be evolving at a rapid pace, Swackhamer says they want to continue forward with baby steps. "We want to start with the Lowcountry first and foremost. I think there is plenty of need here," says Swackhamer. In such a new market, Swackhamer knows that soon there will be competition as other nontraditional farms start to crop up. But she says Tiger Corner Farms isn't concentrating on how to be the market leader. They just want to show up and grow good food. "Part of the fun when people come out, they don't know what to expect," says Swackhamer, "It's exciting that it's been such a short period of time and we're already here. We're putting a different face on a farmer."

How Vertical Farming Reinvents Agriculture

How Vertical Farming Reinvents Agriculture

Instead of growing crops in sunny fields or greenhouses, some companies stack them and grow them in old, dark warehouses with UV lights — saving water and harvesting produce faster.

By Chris Baraniuk

6 April 2017

In an old carpet factory on the outskirts of the Belgian city of Kortrijk, an agricultural upheaval is being plotted: growing crops indoors, not out on a farm, stacked layer after layer under candy-coloured lights in an area the size of a studio flat.

It’s called vertical farming, and several companies have sprung up over the last 10 years or so, filling old warehouses and disused factories with structures that grow vegetables and herbs in cramped, artificially lit quarters out of the warm glow of the sun.

A firm called Urban Crops is one of them. In its case, a large frame is designed to hold conveyor belt-shunted trays of young plants under gently glowing blue and red LEDs in this former carpet factory.

But their system, largely automated, is still a work in progress. When I visit, a software update, scheduled at short notice, means that none of the machinery is working. Chief executive Maarten Vandecruys apologises and explains that, usually, the hardware allows the plants to be fed light and nutrients throughout their growing cycle. Then they can be harvested when the time is right.

“You don’t have the risk of contamination,” says Vandecruys as he points out that the area is sealed off. And each species of crop has a growing plan tailored to its needs, determining its nutrient uptake and light, for instance. Plus, in here, plants grow faster than they do on an outdoor farm.

Some companies are turning to vertical farming, which they say uses less water and grows crops faster than outdoor farms or greenhouses (Credit: Urban Crops)

Urban Crops says that vertical farming yields more crops per square metre than traditional farming or greenhouses do. Vertical farming also uses less water, grows plants faster, and can be used year-round – not just in certain seasons. The facilities also can, in theory, be built anywhere.

At Urban Crops, eight layers of plants can be stacked in an area of just 30sq m (322 sq ft). It’s not a commercial-sized operation, but rather a proving ground intended to show that the concept is viable.

“Basically, inside the system, every day is a summer day without a cloud in the sky,” says Vandecruys.

Stacks and stacks of vegetables and herbs are grown under UV lights, with individual stacks fitting in spaces just 30 sq m (Credit: Urban Crops)

But can you really grow anything in a building, with the right technology at your fingertips?

Vandecruys says it’s possible to grow practically anything inside – but that’s not always a good idea. He explains that it’s more cost-effective to stick to quicker-growing crops that yield a high market value. Herbs, baby greens for salad and edible flowers, for instance, fetch a lot more per kilogram than certain root vegetables, which are more likely to be grown outdoors the old-fashioned way for some time yet.

Basically, inside the system, every day is a summer day without a cloud in the sky - Maarten Vandecruys

By growing plants indoors, you get a lot of fine-grained control you get over the resources your crops need. It allows for rapid growing and predictable nutrient content. The LEDs, for example, can be turned up or down at will and, because they do not give out lots of heat like old filament bulbs, they can be kept close to the plants for optimal light absorption.

Of course, it’s possible to produce the same amount of veg that you might get from an outdoor farm – but with far less land at your disposal.

So, how does it actually work? There are a few main models for indoor agriculture that vertical farmers tend to choose from: hydroponics – in which plants are grown in a nutrient-rich basin of water – and aeroponics, where crops’ roots are periodically sprayed with a mist containing water and nutrients. The latter uses less water overall, but comes with some greater technical challenges. There's also aquaponics, which is slightly different, in that it involves breeding fish to help cultivate bacteria that's used for plant nutrients.

Urban Crops has opted for hydroponics. Vandecruys points out that they recycle the water several times after it is evaporated from the plant and recaptured from the humid air. It’s also treated with UV light to curb the spread of disease.

Perhaps the key benefit of vertical farming is that it uses far less water. “We made an estimation with oak leaf lettuce and there we are actually at, say 5% [water consumption], compared to traditional growing in fields,” explains Vandecruys.

But Urban Crops doesn’t plan to make its money from the sale of crops. It plans to make money on the sale of its vertical farms.

Vertical farm companies hope to one day sell consumers indoor kits of their own for the ultimate 'farm to table' experience (Credit: Urban Crops)

It has designed contained growing systems as a product in and of themselves – people will be able to buy them in order to grow food in relatively confined spaces – potentially bringing farming to urban areas or complexes like the campus of a university. The apparatus can also be installed alongside existing plant production lines at greenhouse farms.

One of the biggest names in vertical farming, however, has a different business model. AeroFarms in New Jersey, USA, has opened what they say is the world’s largest indoor vertical farm – with a total of 7,000 sq m (70,000 sq ft) floor space – and they’re hoping to produce tasty greens in massive quantities.

Ed Harwood is the inventor and agricultural expert who came up with the technology that has made this possible. He got the idea years ago while working for Cornell University, where aeroponic systems were being used to grow plants in a lab setting. Why, he wondered, was this approach not being used on a bigger scale?

“I kept asking, ‘how come’ – people said, ‘Oh, it would never make money, the sun is free, it’s expensive to add lights and everything else, it won’t happen’,” recalls Harwood.

But he wasn’t satisfied with that. After years of experimentation he came up with a system and nozzle design for spraying the aeroponic mist onto his plants’ roots. At AeroFarms, the roots grow through a fine cloth rather than soil. But the details of how he solved the key problem – keeping the nozzles clean over time – remain a trade secret.

“Every nozzle I purchased off the shelf had significant issues,” says Harwood. “I had to do something about it – it was just a cool moment of, I guess, serendipity.” But he’s not telling anyone how he did it.

Like Urban Crops, AeroFarms is prioritising the cultivation of fast-growing salad veg and greens. Harwood believes there is a demand for such produce grown locally in big facilities like theirs that could one day be a feature of city suburbs. And he also promises the guaranteed crunchiness and freshness that consumers want.

Despite futuristic appearances, some vertical farming facilities are built inside old factories or abandoned warehouses (Credit: Chris Baraniuk)

Harwood is firm in his belief that the business he and his colleagues have put together can be profitable. But there are still those who remain sceptical.

Michael Hamm, a professor of sustainable agriculture at Michigan State University, is one of them. He points out that vertical farms depend on constant supplies of electricity, much of which will come from fossil fuel sources.

“Why waste that energy to produce a whole lettuce, when you can get light from the sun?” he says.

And he points out that it just doesn’t make economic sense to grow some crops this way: “At 10 cents a kilowatt hour, the amount of energy it would take to produce wheat would [translate to] something like $11 for a loaf of bread.”

There’s been a spike in home beer brewing – might we see a spike in farming at home, too?

He does acknowledge a few of the benefits, though. If the indoor systems are well-maintained, then the technology should in theory allow for reproducible results with every harvest – you’ll likely get the same quality of crops every time. Plus, while it costs a lot of money to set up a vertical farm in the first instance, it’s potentially a more attractive option to people getting into the agriculture business for the first time – they won’t need to spend years learning how to contend with the vagaries of the sun and seasons. For that, there’s no substitute yet for experience.

With the development of vertical farming technologies, and the likely fall in cost associated with them in coming years, some are betting that all kinds of people will want to start growing their own greens – even at home. There’s been a spike in home beer brewing – might we see a spike in farming at home, too?

Neofarms is one start-up based in Germany and Italy that is anticipating this. Its founders, Henrik Jobczyk and Maximillian Richter, have developed a prototype vertical farm about the size of a household fridge-freezer.

“We designed it in standard kitchen closet sizes,” explains Jobczyk, who adds that their plan is to make the device available as an integrated or standalone design, depending on the customer’s preferences.

People who choose to grow their salad veg at home will pay about two euros (£1.71/2.13) per week in energy costs with this system for the privilege, the pair calculate. And they would also have to keep the Neofarms device clean and constantly topped up with water. But in exchange they will have the freshest produce possible.

“With the plants growing in the system, you know about the conditions they were raised in – that gives you control and knowledge,” says Jobczyk. “But also it’s the freshness, one of the biggest problems with fresh veg – especially the greens – is the field to fork time, the time between harvest and consumption.”

Future supermarkets, though, might be filled with miniature vertical farms of their own

If you pick the plants yourself and eat them straightaway, you might enjoy a richer wealth of vitamins and other nutrients – which can be lost during packaging and transportation. Many consumers already grow their herbs on a window box, but that is a low-cost and low-maintenance activity. It remains to be seen whether the same people would be interested in making the conceptual leap that comes with bringing a mini vertical farm into their own kitchen.

Jobczyk and Richter will have to wait to find out – they’re planning more testing of their device later this year, with a public launch potentially following sometime after that.

Ed Harwood, for one, thinks vertical farming technologies might help to bring agriculture closer to the consumer. But he also sticks by his belief that farming on giant scales is here to stay.

“Irrespective of the number of recalls, I think we’ve improved food safety over all, we’re feeding more people with fewer resources,” he says.

One of the downsides of this is that children have to be introduced to the idea that their food is grown somewhere – it doesn’t come from the supermarket, but a field or factory. Future supermarkets, though, might be filled with miniature vertical farms of their own.

“For the child who says their food comes from the grocery store,” says Harwood, “they might one day be right."

The Art of Urban Farming

The Art of Urban Farming

My Green Chapter brings gardening tools from around the world to help UAE residents join the growing network of urban farmers who want to live more sustainable lives

Published: 16:13 April 5, 2017

By Jyoti KalsiSpecial to Weekend Review

As our cities continue to expand, human beings are losing touch with nature. But the urban farming movement seeks to change this by encouraging people to grow vegetables and fruits in their yards, in empty lots in their neighbourhood and in public spaces such as schools, universities and hospitals. As this hobby becomes more popular, new and innovative products are being developed to help city dwellers grow herbs, salads and vegetables not only in gardens and yards but also on their balconies and inside their apartments.

My Green Chapter has brought this concept to the UAE with the launch of its online store, mygreenchapter.com. The store has sourced gardening and urban farming products from around the world to help UAE residents join the growing network of urban farmers, who want to live in harmony with nature, eat fresh, organic produce and live greener, more sustainable lives.

Besides gardening tools, equipment and materials for adults and children, the company offers innovative ‘smart garden’ technologies that make indoor farming as easy as clicking a button. The company also sells chicken coops, feed and accessories to enable urban farmers to raise chicken in their backyards.

The project is the brainchild of Frenchman Jean-Charles Hameau, who is an animal lover and gardening enthusiast. Hameau graduated in Agriculture Engineering and has a Master’s in Economics. He came to Dubai in 1999 as a commercial attaché in charge of agriculture and food at the French Consulate, and later co-founded the Saint Vincent Group which is the leader in the pet food and accessories industry in the GCC region.

Hameau spoke to the Weekend Review about urban farming and the new products that mygreenchapter.com is bringing to the UAE. Excerpts:

How did you get interested in urban farming?

A few years ago, I saw a documentary on TV about how the urban farming movement started in Detroit, USA, during the economic crisis in 2008, when people began using public spaces and abandoned industrial land to grow vegetables and fruits. Around the same time, I met a chicken coop supplier in Europe, and was surprised to hear that most of his company’s exports were to the GCC region. I did some research and realised that this is a part of the culture of this region and many families in the UAE are growing their own vegetables and keeping chickens in their backyard. Six months ago, I decided to keep some chickens in my garden, and seeing the smiles on the faces of my children when they pick up fresh eggs every morning is one of the factors that convinced me to start My Green Chapter.

What is your vision for the store?

Urban farming not only adds greenery to cities but also helps to reduce pollution and improve our health. Growing vegetables and fruits in our own gardens helps us to reconnect with the Earth and have a greater appreciation for where our food comes from. It reduces the food miles associated with long distance transportation while also ensuring that we eat the freshest produce and foods that are in season. We believe this is not just a passing trend but an unstoppable movement towards sustainable living, so our vision is to bring unique and innovative products to encourage the growth of urban farming in the UAE.

What kind of products are you focusing on?

For UAE residents who have gardens, we wanted to get the best quality gardening tools, seeds, potting soil, organic fertilisers, micro-irrigation kits, gloves and boots, and wooden chicken coops that are suited to the climate. It is particularly important to introduce children and young adults to green and sustainable living, hence we are offering a range of colourful gardening kits for children. Since the weather here makes it difficult to grow anything in summer and most people in the UAE live in apartments, we have sourced many innovative products that allow stress-free indoor gardening throughout the year. We also have a range of pots and planters, including self-watering pots and space saving designs for vertical gardening on indoor walls. We are working with experts in the field to source products that are suitable for the UAE and technologies that make gardening convenient. Our aim is to be a one stop shop for everybody’s gardening needs.

What are the new products you have introduced to this market?

We have many new products that take the effort and unpredictability out of gardening, making it easy for anyone to grow herbs, salads, vegetables and flowers all year round, even in indoor areas with limited space and sunlight. An example is the Click & Grow Smart Garden. All you have to do is to insert the plant capsules, fill the water tank, plug it in and the specially developed smart soil, and built-in sensors will make sure that the plants get optimal water, oxygen and nutrients. It comes with a Grow Light that immaculately calculates the spectrum of light required by the plants and the number of hours the light should be on and off. It makes the plants grow faster without any pesticides, hormones or other harmful chemicals and after you harvest the first crop, you can get new plant refills and re-use the Smart herb garden as many times as you wish.

Similarly, the Plantui Smart Garden is a hydroponic system whereby you can grow tasty greens without soil. The fully automated, patented growth process with special light spectrums, is packed into a beautifully designed ceramic device with overhead LED lights that provide optimal spectrums and intensity for photosynthesis. The watering and lighting are automatically adjusted during all growth phases, so all you do is to place the plant capsules containing the seeds in the device, switch it on and harvest the produce in about eight weeks. It comes in various sizes, to suit different kitchen spaces, allowing you grow three or more types of salads in the same unit.

Likewise, the Mini Garden is an innovative modular wall system for creating vertical gardens in a balcony of any size, or on a wall in a home or office. It comes with a patented irrigation system that automatically waters the plants. We will continue adding new products to our extensive range.

Can raising chicken in one’s yard also be so easy?

Farmers have been raising backyard fowl for over 3,000 years but only in the last five years has it become accessible for even the beginner farmer to raise their own livestock. We are the first suppliers of chicken coops in the UAE, and I can tell you that building a basic chicken coop for a small flock of birds is an easy do-it-yourself project that you can take on if you have a backyard at home. Keep in mind of course the rules regarding this in your neighbourhood and avoid keeping a rooster. It is worthwhile because you can raise them organically, free of hormones and antibiotics, and let them run around your yard rather than being cooped up in a cage. You can get around 300 eggs per hen per year, and the fowl are excellent mosquito repellants.

Is the UAE ready for the urban farming movement?

Absolutely. The country is becoming greener and has launched many sustainable living initiatives such as the urban farming competition recently organised by Dubai Municipality. I have read of urban farming programmes in local schools, and look forward to collaborating in such efforts because it is important for children to get away from their gadgets, step outdoors, connect with the Earth, learn where the food on their table comes from and experience the sheer joy of growing their own vegetables.

Jyoti Kalsi is a writer based in Dubai.

For more information go to www.mygreenchapter.com

Studio Visits: Go Inside Square Roots’ Futuristic Shipping Container Farm In Bed-Stuy

Studio Visits: Go Inside Square Roots’ Futuristic Shipping Container Farm In Bed-Stuy

POSTED ON WED, APRIL 5, 2017BY DANA SCHULZ

In our series 6sqft Studio Visits, we take you behind the scenes of the city’s up-and-coming and top designers, artists, and entrepreneurs to give you a peek into the minds, and spaces, of NYC’s creative force. In this installment we take a tour of the Bed-Stuy urban farm Square Roots. Want to see your studio featured here, or want to nominate a friend? Get in touch!

In a Bed-Stuy parking lot, across from the Marcy Houses (you’ll know this as Jay-Z’s childhood home) and behind the hulking Pfizer Building, is an urban farming accelerator that’s collectively producing the equivalent of a 20-acre farm. An assuming eye may see merely a collection of 10 shipping containers, but inside each of these is a hydroponic, climate-controlled farm growing GMO-free, spray-free, greens–“real food,” as Square Roots calls it. The incubator opened just this past November, a response by co-founders Kimbal Musk (Yes, Elon‘s brother) and Tobias Peggs against the industrial food system as a way to bring local food to urban settings. Each vertical farm is run by its own entrepreneur who runs his or her own sustainable business, selling directly to consumers. 6sqft recently visited Square Roots, went inside entrepreneur Paul Philpott‘s farm, and chatted with Tobias about the evolution of the company, its larger goals, and how food culture is changing.

Kimbal outside one of the farms

Tell us how you got interested in and involved with the urban agriculture movement? And how did you and Kimbal start Square Roots?

I came to the U.S. from my native UK in 2003 to run U.S. operations for a UK-based Speech Recognition software company (i.e. a tech startup). I have a PhD in AI and have always been in tech. Through tech, I first met Kimbal Musk–he’s on the board of companies like SpaceX and Tesla–who at the time was setting up a new social media analytics tech company called OneRiot, which I joined him on in 2006.

Since then, Kimbal’s been working on a mission to “bring real food to everyone.” Even while I was working with him in tech, he had a restaurant called The Kitchen in Boulder, Colorado that sourced food from local farmers and made farm-to-table accessible in terms of menu and price point. His journey in real food started in the late ’90s, when he sold his first tech company, Zip2, and moved to NYC and trained to become a chef, his real passion. When 9/11 happened he cooked for firefighters at Ground Zero. It was during that time – where people would come together around a freshly cooked meal – that he began to see the power of real food and its ability to strengthen communities, even in the most awful conditions imaginable.

In 2009, while we were both working at OneRiot, Kimbal had a skiing accident and broke his neck. Realizing life can be short, he decided to focus on this idea of bringing real food to everyone. So he left OneRiot to focus on The Kitchen, which is now a family of restaurants across Chicago, Boulder, Denver, Memphis, and more. That organization ploughs millions of dollars into local food economies across the country by sourcing food from local farmers and giving its customers access to healthy, nutritious food. They also run a nonprofit, The Kitchen Community, that’s built hundreds of learning gardens in schools across the country, serving almost 200,000 school children a day.

After Kimbal’s accident, I became CEO of OneRiot, which was acquired by Walmart in 2011, where I ended up running mobile commerce for international markets. I learned a lot about the industrial food system there by working with huge data sets of the groceries people were buying across the globe and researching where those foods were being grown. I began to visualize food being shipped across the world, thousands of miles, before consumers bought it. It’s well known that the average apple you buy in a supermarket has been traveling for nine months and is coated in wax. You think you’re making a healthy choice, but the nutrients have all broken down and you’re basically eating a ball of sugar. That is industrial food. I left Walmart a year later and became CEO of an NYC photo editing software startup called Aviary, but I couldn’t get this map of the industrial food system out of my head. When Aviary was acquired by Adobe in 2014, I re-joined Kimbal at the Kitchen and we started developing the idea for Square Roots.

What we saw was that millions of people, especially those in our biggest cities, were at the mercy of industrial food. This is high calorie, low nutrient food, shipped in from thousands of miles away. It leaves people disconnected from their food and the people who grow it. And the results are awful – from childhood obesity to adult diabetes, to a total loss of community around food. (Not to mentioned environmental factors like chemical fertilizers and greenhouse gases.)

We also saw that these people were losing trust in the industrial food system and wanted what we call “real food.” Essentially, this is local food where you know your farmer. (This isn’t just a Brooklyn hipster foodie thing. Organic food has come from nowhere to be a $40 billion industry in the last decade. “Local” is the food industry’s fastest growing sector.)

Meanwhile, the world’s population is growing and urbanizing quickly. By 2050 there will be nine billion people on the planet, and 70 percent will live in cities. So if we have more people living in the city, demanding local food, the only conclusion you can draw is that we’ve got to figure out how to grow real food in the city, at scale, as quickly as possible. In many ways NYC is a template for what that future world will look like. So our thinking was: if we can figure out a solution in NYC, then it will be a solution for the rest of the world as it increasingly begins to look like NYC. The industrial food system is not going to solve this problem. Instead, this presents an extraordinary opportunity for a new generation of entrepreneurs – those who understand urban agriculture, community, and the power of real, local food. Kimbal and I believe that this opportunity is bigger than the internet was when we started our careers 20 years ago.

So we set up Square Roots as a platform to empower the next generation to become entrepreneurial leaders in this real food revolution. At Square Roots, we build campuses of urban farms located in the middle of our biggest cities. The first campus is in Brooklyn and has 10 modular, indoor, controlled climate farms that can grow spray-free, GMO-free, nutritious, tasty greens all year round. On those farms, we coach young passionate people to grow real food, to sell real food, and to become real food entrepreneurs. Square Roots’ entrepreneurs are surrounded and supported by our team and about 120 mentors with expertise in farming, marketing, finance, and selling–basically everything you need to become a sustainable, thriving business.

Why did you choose to set up at Bed-Stuy’s Pfizer Building?

We believe in “strengthening community through food,” and hopefully by joining forces with all the awesome local food companies already in Pfizer, we’re doing our part towards that. Next, in the lead up the first World War, that factory was the U.S.’s largest manufacturer of ammonia, which at the time was used for explosives. Post war, the U.S. had excessive amounts of ammonia, and it started being used as fertilizer. So in many ways, that building is the birth place of industrial food. I like the act of poetic justice that we now have a local farm on the parking lot.