Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Fresh Veggies Grown Close to Home, Without Pesticides — And Without Dirt

Fresh Veggies Grown Close to Home, Without Pesticides — And Without Dirt

Civic Farms touts having “pioneered the vertical farming industry.” The company says its proprietary growing systems, licensed patented technologies, and optimized processes for cultivation and harvesting processes maximize the efficiency and efficacy of growing indoors.

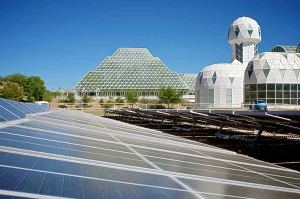

TUCSON (CN) – An ambitious project of emerging agricultural technologies that produce food without soil is taking shape at Biosphere 2, the University of Arizona’s research complex north of Tucson.

Civic Farms, an Austin-based company, this summer will start building a vertical farm in one of two 20,000-square-foot domes – or “lungs” – that regulated pressure inside a sealed glass structure during experiments to study survivability in the 1990s.

The company will invest $1 million to renovate the Biosphere’s west lung, unused for years, and outfit the space with stacked layers to grow soil-free plants in nutrient-laden circulating water under artificial lights.

At full capacity, the vertical farm will produce 225,000 to 300,000 lbs. a year of leafy greens and herbs such as lettuce, kale, arugula and basil, said Paul Hardej, CEO and co-founder of Civic Farms.

“Biosphere itself is a fantastic facility and food production is a big part of what it was originally intended to do,” he said.

As the world population continues to rise, particularly in cities, along with consumer interest in the origins of food, vertical farming is gaining traction as a commercially viable way to increase crop production in a fully controlled indoor environment.

“People want know what they eat and what’s in their food and how healthy and good it is for them,” Hardej said. “Growing food in city centers or close to city centers where people live makes perfect sense.”

Under an agreement with the university, Civic Farms will grow crops in half the space it will lease for $15,000 annually. Research and scientific education will comprise the other half and the company will contribute $250,000 over five years for those efforts.

“We envision that a portion of the lung will be open and accessible to the public so people can come in see how and what it is to have a vertical farm,” said John Adams, the Biosphere’s deputy director.

Civic Farms touts having “pioneered the vertical farming industry.” The company says its proprietary growing systems, licensed patented technologies, and optimized processes for cultivation and harvesting processes maximize the efficiency and efficacy of growing indoors.

The Biosphere already draws nearly 100,000 annual visitors to expansive grounds originally intended to showcase a self-sustaining replica of Earth, or Biosphere 1.

Set on a 40-acre campus against the backdrop of the rugged Santa Catalina Mountains, the Biosphere’s 91-foot steel-glass structure serves as a global ecology laboratory enclosing an ocean, mangrove swamp, rain forest, savanna and coastal desert.

In the early 1990s, a crew of scientists was locked inside the sealed structure in privately funded scientific experiments designed to explore survivability with an eye toward space colonization. Problems with the experiments and management disputes eventually halted the highly public venture.

The University of Arizona took over the property, about 30 miles north of Tucson in the town of Oracle, in 2011.

The Biosphere’s Adams views the planned vertical farm as a good fit for research initiatives.

“For the next 10 years, Biosphere’s focus is very much on food, energy, water – and the nexus,” he said.

Civic Farms’ Hardej said the university’s myriad resources were strong incentives for his company’s new enterprise in Arizona. A big plus are the concepts being developed at the university’s Controlled Environment Agriculture Center on North Campbell Avenue, where scientist Murat Kacira grows leafy crops indoors under LED lights.

“There’s so much interest in this technology platform because it provides the capability to grow food with consistency,” Kacira, a professor of agricultural-biosystems engineering, said of vertical farm systems.

Inside the lab where lettuce and basil grow in hydroponic beds under the glow of blue and red LED lights, Kacira and his students monitor the conditions in which seedlings mature.

“The environment is fully controlled in terms of providing temperatures needed, or humidity needed, carbon dioxide or the light intensity or the quality needed for the plant production,” Kacira said.

Not being at the mercy of Mother Nature makes vertical farms more productive than conventional farms, as well as more efficient at using natural resources such as water, he said. “You’re circulating it inside the environment, so the efficiency is much higher.”

Still, Kacira said, the technology is energy-intensive, given the use of artificial lights and the need to condition the environment. And although large-scale commercial operations are relatively rare, he said, advances in scientific research and the high-tech industry are making it a feasible platform to help supplement food production in cities.

“Our food transportation is coming from long distances, and by the time it gets to the consumer, especially leafy crops, the freshness may not be there,” Kacira said.

Vertical farms are a relatively new concept that hold great potential, Hardej said it. With a projected global population of 9.5 billion, mostly urban, by 2050, he views vertical farms as an increasingly important part of the world’s food system.

His own vertical farm aims to provide the Tucson and Phoenix markets with high-quality produce grown sustainably and without pesticides, Hardej said.

In time, he plans to incorporate more energy-efficient solutions into his operation.

“For commercial scale, those technologies still need to be perfected,” he said.

His company plans to begin growing the leafy greens by year’s end.

AeroFarms Raises $34m of $40m Series D from International Investors for Overseas Expansion

AeroFarms Raises $34m of $40m Series D from International Investors for Overseas Expansion

MAY 30, 2017 LOUISA BURWOOD-TAYLOR

US indoor agriculture group AeroFarms has raised over $34 million, according to a Securities & Exchange Commission Filing. The funding is the first close of a targeted $40 million Series D round.

AeroFarms grows leafy greens using aeroponics –- growing them in a misting environment without soil –- LED lights, and growth algorithms.

The round takes AeroFarms’ total fundraising efforts to over $130 million since 2014, according to AgFunder data, including a $40 million debt facility from Goldman Sachs and Prudential.

AeroFarms attracted new, international investors in this latest round, including Meraas, the investment vehicle of Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid, vice president of the United Arab Emirates and the ruler of Dubai.

The round marks the first investment for ADM Capital’s new growth stage agriculture-focused Cibus Fund, and global asset management firm Alliance Bernstein also invested. Existing investors Wheatsheaf Investments from the UK and GSR Ventures from China also joined the round.

The filing also revealed that AeroFarms had renamed its holding company to Dream Holdings, as part of its move from an LLC to a C-Corp, referencing its new retail brand Dream Greens. The Dream Greens brand hit the shelves of ShopRite, Whole Foods, FreshDirect, and Newark chain Seabras in February. Before that, the business was selling its greens into food service under the AeroFarms brand.

AeroFarms’ global list of investors is representative of its plans to expand globally, David Rosenberg, CEO, told AgFunderNews.

“We want to expand domestically and overseas, and we are excited about the potential for Meraas to help us expand into that region,” he said.

AeroFarms is not the only group to consider building indoor farms in the Middle East; Pegasus Agriculture Group, is a hydroponics-based indoor ag company that is based in Abu Dhabi, with facilities across the Middle East and North Africa. Egyptian Hydrofarms is another local example, and Indoor Farms of America recently made its first farm sale in the region.

AeroFarms also wants to add to its 120-strong team of plant biologists, pathologists, microbiologists, mechanical engineers, system engineers, data scientists and more. In particular, the company wants to add team members to its research & development department, with a view to improving the quality and operating costs of the business, according to Rosenberg. “This is where the data science and software platforms we’re using can really pull the business together.”

AeroFarms just completed construction of its ninth indoor farm, with four in New Jersey including its state-of-the-art 69,000 square foot flagship production facility in Newark. It also has plans to build in the Northeast of the US.

For more about AeroFarms, read our earlier interview with CEO David Rosenberg here.

Vertical Farms Grow Amid Skyscrapers In A Plan to Help Feed China’s Largest City

Vertical Farms Grow Amid Skyscrapers In A Plan to Help Feed China’s Largest City

Laura Brehaut | June 1, 2017 9:39 AM ET

More from Laura Brehaut | @newedist

Sasaki Associates

The hydroponic vertical farm will be dedicated to growing Shanghai staple greens such as kale, lettuce and spinach.

As Shanghai sprawls outward, architecture firm Sasaki Associates has announced plans for a farm that grows upward. The hydroponic vertical farm will be built amid the skyscrapers of China’s largest city. Like most vertical farms in use today, it will be dedicated to growing staple leafy greens such as kale, lettuce and spinach, according to Dezeen.

Space-saving is the aim of the project, Dezeen reports. Sasaki Associates intends the multi-storey farm to act as an alternative to the vast swaths of land — and associated costs — required for traditional agriculture. The project will also incorporate urban farming techniques such as algae farms, floating greenhouses and a seed library.

Vertical farms exist in cities worldwide, providing fresh produce, fish, crabs and other foods to residents in cities such as Anchorage, Berlin, Singapore and Tokyo. Advocates say that vertical farms have a reduced carbon footprint, use fewer pesticides and guzzle less water than traditional farming. Opponents argue that there are many unanswered questions about the practice, and question its economic viability.

Construction of the Shanghai project is expected to start in late 2017 as part of a new development — the Sunqiao Urban Agricultural District. The district will also feature markets, a culinary academy, interactive greenhouses and an education centre for members of the community.

Strawberry Imports May Become Unnecessary For Russia

Strawberry Imports May Become Unnecessary For Russia

It is now possible to grow strawberries all year round across Russia, from Kaliningrad to Yakutia, with a total of 6 harvests a year, as reported by agroinfo.com

The Russian company Fibonacci presented an innovative product for agriculture: the automated vertical farm BerryFarm800, which makes year-round strawberry cultivation possible.

BerryFarm800 is capable of producing 6 harvests of this delicious fruit per year, including during the winter months. The 800 sections of the agro-farm, with space for 76,800 bushes, yield 15 tonnes of strawberries a month.

Managing the farm does not require special knowledge or a lot of staff. BerryFarm800 only requires 5 people because all processes are automated.

Also, remote control of all farm parameters is possible thanks to a program developed specifically for BerryFarm800.

Another advantage of the system is that there is no need to build a greenhouse. The BerryFarm800 can operate in any ready-made commercial space: warehouses, production rooms, and so on. The farm is totally independent of climatic conditions.

Another advantage is the quick installation and the start of its operation, 2 months from the time of ordering.

The Russian company's product has no equal in the world, and according to expert assessments, it could have a significant impact on Russia's food policy. It could even make the import of strawberries completely unnecessary.

"Nowadays, in a context marked by sanctions and fierce import policies, this product is economically attractive to all consumer groups. The equipment can be delivered to any country, allowing customers to grow quality strawberries for private or commercial purposes," stated a Fibonacci representative.

Cloud Controlled Mini-Farms | AUDIO Interview - Smallhold

Cloud Controlled Mini-Farms | AUDIO Interview - Smallhold

31 May 2017

Very soon, grocery stores will be cloud-controlled mini-farms with shelves of growing produce -- according to the co-founders of the Brooklyn startup Smallhold. Hear how their ideas for vertical farming could impact your home, your supermarket and even outer space.

Click Above for Audio

We farm for you by growing produce 3/4 of the way and then deliver it to miniature vertical farm units (the size of shelving units) at your place of business to be harvested onsite as fresh, local food.

Smallhold gives you a networked farm, complete with sensors, climate control mechanisms, and hydroponics. Our horticulturalists run the farm from afar, growing for you right up until you pick and serve your produce.

From Slaughterhouse To Vertical Farm: The Plant Is Innovating In Sustainability And The Circular Economy

From Slaughterhouse To Vertical Farm: The Plant Is Innovating In Sustainability And The Circular Economy

May 30, 2017 Chuck Sudo, Bisnow, Chicago

In 1906, Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle” depicted the harsh conditions workers toiled under inside the slaughterhouses of the Union Stock Yard and Packingtown. A century later, this area that gave Chicago its brawny identity as “hog butcher for the world” is now home to several new food businesses focusing on sustainability, and The Plant in Back of the Yards is its epicenter.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow - The Plant, a vertical farm in Back of the Yards, was once a slaughterhouse.

This 94K SF former slaughterhouse was abandoned and slated for demolition when John Edel — through his company Bubbly Dynamics — bought it in 2010 and slowly repurposed the building into a vertical farm and food production business committed to a "circular economy," a closed loop of recycling and material reuse. Today, the Plant is home to several businesses where the waste stream from one business is repurposed for use by another business elsewhere in the building.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow

Whiner Beer Co. brews its beer at The Plant and opened a taproom whose bar, tables and chairs were made from reclaimed wood.

The Plant’s tenants are a who’s who of local food producers. Pleasant House Bakery is a popular company that bakes breads, desserts and Yorkshire-style meat pies that are sold wholesale at farmers markets and at Pleasant House’s Pilsen pub. Arize Kombucha distributes nearly 500 gallons of fermented probiotic tea monthly to area grocery stores. Four Letter Word Coffee, a boutique coffee roaster, has a roastery on the second floor. Whiner Beer Co. specializes in Belgian-style ales and operates a taproom inside the Plant. Justice Ice makes crystal-clear ice for use by Chicago’s best bars and restaurants for their cocktails. The Plant also has an outdoor farm, an indoor aquaponic farm that grows an average of five pounds of greens a week, an indoor tilapia farm and hatchery, a mushroom farm capable of growing 500 pounds of oyster mushrooms a month, and an apiary for making honey.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow

The Plant has an outdoor farm and an indoor aquaponics farm on the basement level.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow

With all of that happening, waste is bound to pile up. And the Plant repurposes over 90% of the waste byproducts created by its tenants. Waste from the fish farm and carbon dioxide from kombucha production is used to fertilize the greens in the aquaponics farm, which in turn filters the water that goes back to the tilapia farm. Spent grain from the brewery is used to feed the fish and for Pleasant House’s baking purposes. The Plant’s tenants even repurpose as many building materials as possible. The bar, tables and seating inside Whiner Beer Co.’s taproom was made from reclaimed wood. Pleasant House uses scrap wood to fire its ovens. Sections of the former slaughterhouse's hanging rooms (where beef and pork were processed assembly line-style and aged) are now bathrooms that comply with the Affordable Care, and other sections are being rebuilt into an information center that will open in the fall.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow

The Plant is in the process of installing a digestible aerator that will produce methane and fertilizer for The Plant's internal uses and outside uses.

The linchpin in the Plant's circular economic model is a 100-foot-long anaerobic digester. This machine is capable of breaking down biodegradable material without oxygen to create methane gas to power the Plant's electrical generation systems, algae and duckweed to feed the tilapia, produce enough process heat for use by the brewery, coffee roaster and baker, and make fertilizer for the outdoor farms. The digester is capable of producing 2.2 million BTUs of biogas. On a smaller level, the Plant is also experimenting with making biobriquettes, a hockey puck-sized brick of biomass from spent grain and coffee chaff, that can be used as fuel in the bakery's ovens instead of wood.

The Plant's circular economy has the possibility of being adapted on a larger scale. A French food engineer and Brazilian urban engineer spent their internships at the Plant analyzing material flows in order to create methodologies to determine if the Plant's closed loop system can be used for developing more efficient urban ecosystems and sustainable cities.

Related Topics: The Plant, Bubbly Dynamics, John Edel, union stock yard, packingtown, Chicago stockyards, Chicago sustainability, Chicago adaptable reuse

AeroFarms To Open World’s Largest Indoor Farm In Camden

AeroFarms To Open World’s Largest Indoor Farm In Camden

By Gillian Blair - May 30, 2017

Credit: AeroFarms

AeroFarms will soon surpass itself as the world’s largest indoor vertical farm with a second and larger New Jersey location in Camden. Set to be operational by 2018, Farm No. 10 will be 78,000 square feet on the 1500 block of Broadway. They are still working on the design of the facility and will need to gain local zoning approvals, but the biggest victory was already won when AeroFarms LLC was awarded an $11.14 million grant in tax incentives by the New Jersey Economic Development Authority.

Farm No. 9 in Newark, New Jersey, is currently the world’s largest indoor vertical farm based on annual growing capacity and where, in a converted steel mill, they harvest up to 2 million pounds a year. AeroFarms is able to germinate seeds in 12 to 48 hours–a process that typically takes 8 to 10 days–and focuses on growing leafy greens like baby kale and arugula and packaging under the name “Dream Greens” for distribution locally in North Jersey and Manhattan. Farm No. 10 in Camden will supply South Jersey and Philadelphia.

The greens are grown “aeroponically,” meaning the roots grow downward, dangle in the air, and are misted with water and minerals. And the process dispenses with premium elements like land and water: “We can grow on one acre what would normally take 130 acres on a field farm. And we use 75 percent less water [than hydroponics],” said Co-founder and CEO David Rosenberg.

AeroFarms has come far since Farm No. 1 in a converted kayak shop in Ithaca, New York, where Ed Harwood, an associate professor in the Cornell University School of Agriculture, became interested in growing things without the elements that grow things: soil, sunlight, a lot of water. Now Co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer, his biggest breakthrough was developing the root mister that doesn’t clog. Also developed for this practice of vertical farming is a cloth made of recycled soda bottles on which the seeds germinate and through which the roots grow downward.

Even the lighting is specially calibrated and everything is monitored electronically. AeroFarms recently won a “vision” award at the Global Food Innovation Summit in Milan which was an especially exciting honor as it recognizes “the coolest vision of how the world should work,” said Mr. Rosenberg.

The tax incentives enabling AeroFarms to open their second facility in Camden are part of the Grow New Jersey Assistance Program Grants which incentivize businesses to relocate or start-up in economically challenged areas, infusing the local economy, workforce, and property with capital, opportunities, and improvements.

Have something to add to this story? Email tips@jerseydigs.com. Stay up-to-date by following Jersey Digs on Twitter and Instagram, and liking us on Facebook.

Why High-Tech Urban Farms Won't Displace Community Gardens

Why High-Tech Urban Farms Won't Displace Community Gardens

Jody Allard/May 16, 2017

To serve neighborhoods, they need to work together.

High-tech innovations can help urban farmers grow anywhere. (Open Agriculture Initiative, MIT Media Lab)

Urban farmers are increasingly leveraging technologies like machine learning and smartphone integration to build high-yield farms in small urban spaces. And while it may seem that those innovations upend the “slow food” idea of working together in the dirt to grow organic zucchini or lettuce, sharing time and crops with neighbors, the success of these higher-tech projects may hinge on the support of local community gardeners.

In theory, a commitment to building a local food system that meets the needs of urban dwellers without relying on long-distance transportation methods—which can leave a substantial carbon footprint—is great. Many contemporary urban farms are cropping up in direct opposition to large-scale agricultural operations that are perceived as harmful to people and the environment. But in practice, urban farmers have struggled with limited real estate, high-priced infrastructure, and other challenges unique to the city environment. (Chicago’s green rooftop initiatives, for instance, were successful in revitalizing interest in urban farming, but even the 3.5 million square feet of urban farmland on 500-plus rooftops has failed to make a real dent in the city’s food demands.) Those are constraints that high-tech innovations aim to solve.

HIGH-TECH HELP FOR URBAN FARMERS

Housed on only one-eighth of an acre, Urban Produce in Irvine, California, harvests the volume of crops typical of a 16-acre facility. The indoor vertical farming operation specializes in growing organic microgreens, herbs, and leafy greens in a controlled environment. While Urban Produce has only one location today, they have big aspirations. "In five years, we hope to build 25 urban farms worldwide. Imagine cities, corporate campuses, master-planned communities, cruise ships, and military bases growing their own local, organic produce," says Urban Produce CEO Ed Horton. "In 20 years, I expect we’ll be growing organic produce on the International Space Station."

Space farming aside, high-yield urban farms that produce thousands of pounds of food are only one piece of the tech-enabled urban farming puzzle. Other initiatives are focusing on bringing families back into the fold with self-contained farms that are designed for use in small city apartments. Grove Garden combines an aquarium with a garden to create a closed-loop ecosystem: you feed the fish, their water is cycled to water the plants, and the plants grow to feed you. Grove Garden uses one-tenth of the water of traditional farming methods, and it's all remotely manageable by a smartphone app.

Still in the fundraising stage, Lyfbox is another permaculture garden option that can produce 40 different crops in a few feet of growing space. But Lyfbox goes one step further with an app that leads urban farmers from planting to cooking, reducing food waste by providing recipe suggestions when a crop is ready to harvest. The app even connects farmers with their community to help them buy or sell their crops from their smartphones.

The most productive urban farms have one thing in common: they rely on tightly controlled environments in order to maximize crops year-round, regardless of local growing conditions. In these environments, growing conditions are automated based on a combination of farming wisdom, trial-and-error, and growing models. But until recently, there was no such thing as an ideal "recipe" for growing conditions—making each smart farming environment only as good as the data it has available.

MIT's OpenAg initiative, in partnership with Sentient, hopes to change that. Using the power of 2 million computers located in 4,000 sites worldwide, researchers set out to discover whether advanced artificial intelligence could offer farmers insight into the optimal way to grow crops. Researchers began by testing basil in growing chambers called "Food Computers," which are similar to the type of closed-loop environments used by many urban farmers. Soon, the AI made a surprising discovery: basil grows best when exposed to continuous sunlight. By the end of the 18-week experiment, researchers had collected three million points of data, per plant, per growth cycle. This data is publicly available to anyone who wants to work with it, and in the future, researchers hope to program the AI to adapt its growing conditions based on what it learns throughout the growth cycle.

MIT’s food computer information is open data, so any farmer can build one. (Open Agriculture Initiative, MIT Media Lab)

"Farmers know a lot about the conditions in their own environment, but not even the best farmer knows how to grow the plants optimally when you can control all these environmental factors at will," says Risto Miikkulainen, vice president of research at Sentient. "We believe these recipes will help farmers grow the best crops, with the most yield, in the places that need [them] most. This would not only reduce the cost of exporting food across the world, but also reduce the amount of energy required to grow plants. We might even see food being grown directly in grocery stores."

If grocery stores doubling as farms sounds outlandish, consider how unlikely growing meat in a laboratory would've sounded a decade ago. The technology exists to make these goals a reality, but it will take more than technology to revolutionize urban farming. Their success relies on a community that's interested in and educated about sustainability, and is willing to invest in it—and that's where small community gardens can make a big impact.

COMMUNITY GARDENS HAVE DEEP ROOTS

With increasingly divergent technologies and resources, you might expect community gardeners to be at odds with the new generation of high-tech urban farmers. As urban farms continue to adopt new technologies to enhance their crop yields, space constraints could eventually pit the two against each other. Are community gardeners excited by the prospect or afraid they'll lose the community that made their gardens so successful?

In many cases, today's community gardens exist to solve a problem very different from the one they were aiming at in the 1890s, when Detroit and other cities looked to them to offer residents a place to raise a homegrown solution to an economic recession that left laborers unemployed and hungry. Now, many gardens are an antidote to isolation from nature and neighbors. While some gardeners enjoy the financial benefits of selling food, most community gardens aren't intended to feed their communities entirely. Unlike large-scale urban farming operations, their primary focus is on teaching sustainable farming principles and connecting with members of their communities.

Higher-tech innovations won’t necessarily compete with community gardens that are deeply rooted in their communities. (Carlos Jasso/Reuters)

Karin La Greca is on the board of the Fresh Roots Farm, a two-acre nonprofit organic educational farm in Mahweh, New Jersey. While each volunteer receives some of the food the farm produces, she says it's the community, not the food, that attract volunteers to the farm. "Community gardens give a sense of place to the residents of the community," she says.

Sable Bender used to work for an organic farm that relied on draft horses to plow the fields. Now, she works for the largest greenhouse manufacturer in the country and does her own farming on a smaller scale, helping out at a local school garden. She sees larger urban farms and community gardens as essential to each other's existence. "As people learn about urban farms, it encourages them to get involved with a community garden and it creates a desire to know more and try growing something for themselves," she says. "On the other hand, you have people who have been involved with a community garden taking on larger urban agriculture projects."

La Greca agrees. Far from being afraid of the impacts of urban farms on her own small community garden, she welcomes the opportunity to teach sustainable farming principles to a larger audience. "Community gardens allow residents to connect with nature, something that has been lost along the way," she says. "As community gardens move forward both in municipalities and schools, I believe farmers will get the respect they deserve and the community will support the farmers and collaborate together to change our food system for a better future."

Artificial intelligence and smartphone-integrated farms might seem like strange bedfellows for a movement that prides itself on returning to a more "natural" state. Talking casually about machine learning and closed-loop ecosystems, these aren't your grandparents' farmers—and they may be exactly what's needed to make their vision of sustainable urban farming a reality.

The Urban Farmer: Interview With João Igor of CoolFarm

The Urban Farmer: Interview With João Igor of CoolFarm

In Future trends Posted on May 25, 2017

Created out of necessity, CoolFarm now offers smart farming solutions that allow you to plug, play, and produce fresh food all year round. Get the inside scoop on how co-founder João Igor has discovered a novel way to make agriculture an integral part of urban life.

If you haven’t heard about urban farming, you must have been living under a rock for the past few years! City-based agriculture offers the opportunity to have healthy food in abundance, at a fraction of the cost, by growing only what we need, close to home.

Urban ag startups have boomed in the last few years, offering everything from unorthodox growing setups to soil sensors, hydroponics and all manner of crop data analytics. We’ve recently spoke to João Igor of CoolFarm, a Portuguese startup operating in the smarter food and in the greenhouse sustainable agriculture area. Here’s their take on the potential for urban farming.

“I found myself suffering from health problems due to the fast food that we consume inside cities, I’ve also seen my friends and family suffering from the same issues. I wanted to do something to fight this, and I ended up in finding the right team of co-founders for this project.”

Together, we started building the CoolFarm technology in order to make farming easier and to bring fresh and nutritious food to cities, close to the people.

New Sustainable Model

CoolFarm offers indoor farming solutions for production of high quality food. Their solutions provide maximum efficiency and profitability. Their control system, called CoolFarm in/control is plant-centred. Using an intuitive dashboard, growers are able to monitor and contnrol all their farms at once, anywhere, anytime. Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms ensure optimized crop production, as well as efficient management of resources.

“We also offer to the market the CoolFarm Eye, an innovative cloud based optical sensor made to capture plants’ area and plant greenness, monitoring crops through time,” explains João. “Using the Eye, growers can make wiser and straight forward decisions to achieve the best results.”

2017 marks the launch of CoolFarm in/store, a closed and vertical system with a clean and climatized environment inside, perfect to grow premium seedlings, microgreens, leafy greens, herbs and flowers. Reportedly, it uses 90% less water than common agriculture and it does not need pesticides or herbicides. It is modular, with each module covering nearly 100 square meters of the production area.

Intelligent and highly intuitive, the system is aimed at growers, food distributors, grocery and supermarket chains, research centers, medical centers, and communities.

The system is equipped with two columns of movable hydroponic growing beds, one vertical lift, a fertigation system, topnotch sensors to measure all the variables concerning the plants, LED grow lights, CoolFarm in/control system and an antechamber.

Cities Turning Green

Throughout the world, urban farming is becoming an integral part of the urban landscape. CoolFarm is part of the booming trend. However, in order to emerge into a viable industry solution, CoolFarm needs agents and distributors worldwide, as well as adequate support from governments.

“Stakeholders must jointly address food and sustainability issues, and promote novel technologies and solutions for better farming,” says João. Although there is an urgent need for producing health, tasty, environmentally sustainable food, redesigning the agricultural system would not be straightforward.

As a creative person and as a designer my job is to build new and intuitive solutions, as well as to communicate them in the best way; as a tech guy I need to bring top notch technology, like robotics, for fields in need.

Sprouting Imaginative Solutions

The European startup ecosystem has bred numerous success stories, and CoolFarm is one of them. “We’ve gained a lot of attention, especially from the media, which is essential for any startup business trying to create brand awareness.” They also learned a lot about marketing, business, and securing funding and capital.

However, the biggest lesson, by far, is avoiding money from people that don’t understand complex markets such as agriculture.

“In general, European incubators and accelerators are good. We have excellent people behind the scene, and Europe doesn’t lack experience or knowledge.”

Apparently, launching a startup in Europe was the right decision: the team now counts nearly 20 people creating indoor farming solutions, from horticulturists and biologists, software and hardware engineers, web, mobile and product designers, marketing and business experts.

If you want a sustainable business in agriculture, avoid money from people who don’t understand such a complex market.

Early product is strong, but their roadmap is much more exciting. “We want to install the in/store solution at universities, hospitals, supermarkets, cruises, buildings,” says João, adding that they want to grasp a significant portion of the market with their new product. “The next 18 months are going to be game changing for CoolFarm. Watch and see!”

Coffee Grounds Used To Feed A Hungry City

Coffee Grounds Used To Feed A Hungry City

In an Australian first, Port Melbourne based coffee company Red Star Roasters has partnered with urban food production company Biofilta, to transform a disused Melbourne carpark into a pop-up espresso bar and thriving vertical urban food garden. The garden is converting the by-product from Melbourne's unique coffee culture coffee grounds into thousands of dollars of fresh edible produce for charity kitchens.

The Red Star Urban Garden Espresso Bar, located at The Holy Trinity Anglican Church at 160 Bay Street, Port Melbourne, features an innovative vertical food garden that uses soil made from composted green waste and coffee grounds, to grow a full range of vegetables and herbs including basil, beans, eggplant, capsicum, kale, lettuce, oregano, rhubarb, spinach, strawberries, thyme, tomatoes, zucchinis, beetroot, broccoli, bok choy and many others. Coffee grounds are collected from the espresso bar, mixed with garden clippings, cardboard packaging, soil and worms to create a rich compost onsite. The compost is then returned to the vertical gardens, to grow food. The produce is then harvested and donated to the South Port Uniting Care?s Food Pantry and Relief Service in South Melbourne. Diane Embry, the Agency's Chief Executive Officer, says, the donations enables us to provide fresh produce to people in our community who are experiencing disadvantage, social isolation and homelessness.

The garden itself is unique - with vertically stacked growing beds that are self-watering and an innovative aeration loop to keep the plants and soil oxygenated and healthy. The garden is ultra water efficient and spatially compact, and by going vertical the garden produces a large amount of food on a very small footprint, effectively doubling food yield per square metre. The vertical garden is integrated into the espresso bar coffee grounds used to feed a hungry city and café patrons are surrounded with edible gardens, aromatic herbs and flowers as they read the paper and have a coffee. In the past 12 months, the garden has produced well over 100 kilograms of vegetables and herbs from 10 square metres of garden area. However, because of the vertical design, the garden is only using 5 square metres of space. This means the garden is producing 10 kg of food per 1 sqaure metre of garden every year and at an average cost of between $5 to $10 per kg for vegetables at the Supermarket, the garden is producing $50 to $100 of food per metre square each year.

It is great having a garden that saves you money while feeding you and the family at the same time. Australia imports over 40,000 tonnes of coffee beans per annum, resulting in a huge waste stream of used coffee grounds that go to landfill. Red Star and Biofilta have worked out a way to divert this useful by-product into food to feed a hungry city and are now looking to replicate the model with cafes and restaurants who are interested in saving on food bills and growing fresh produce onsite. 100% of coffee grounds from the Red Star Urban Garden Espresso Bar are either used in the garden, or given away for free to customers to use in their gardens at home.

Creating A Zero-Coffee-Waste Café!

CEO of Biofilta, Marc Noyce said - Thousands of tonnes of coffee grounds are produced each week in Australia's cafés and restaurants, and most ends up in landfill. Red Star and Biofilta have shown how this wonderful material can be composted to soil and help feed hungry cities at the same time. Both companies are looking for more opportunities to repeat the formula with any café or restaurant who are interested in ethically sourced coffee, and have a spare space, wall, rooftop or balcony to turn.

For more information call:

Diane Falzon, Falzon PR- 0430596699

Marc Noyce, CEO, Biofilta - 0417 133 243

Chris McKiernan, Director, Red Star Coffee - 0418 136 301

Kimbal Musk Says Food Is The New Internet

Kimbal Musk Says Food Is The New Internet

Former tech entrepreneur Kimbal Musk’s ambitions for innovation in sustainable farming are as grand as his brother Elon’s for space travel and electric cars

URBAN COWBOY | Kimbal Musk at Koberstein Ranch in Colorado. “He’s got good judgment overall and has been put through the ringer a few times,” says his brother, Elon. PHOTO: MORGAN RACHEL LEVY FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE

By Jay Cheshes

May 25, 2017 10:52 a.m. ET

ON A BRISK WINTER morning, Kimbal Musk is an incongruous sight in his signature cowboy hat and monogrammed silver K belt buckle—his folksy uniform of the past few years—as he addresses a crowd outside a cluster of shipping containers in a Brooklyn parking lot. Inside each container, pink grow lights and fire hydrant irrigation feed vertical stacks of edible crops—arugula, shiso, basil and chard, among others—the equivalent of two acres of cultivated land inside a climate-controlled 320-square-foot shell. “This is basically a business in a box,” Kimbal says, presenting his latest venture to its investors, friends and curious neighbors.

Square Roots, his new incubator for urban farming, aims to empower a generation of indoor agriculturalists, offering 10 young entrepreneurs this year (chosen from 500 applicants) the tools to build a business selling the food they grow. It will take on and mentor a new group annually, with more container campuses following across the country. “Within a few years, we will have an army of Square Roots entrepreneurs in the food ecosystem,” he says of the enterprise, launched last November with co-founder and CEO Tobias Peggs—a British expat with a Ph.D. in artificial intelligence—across from the Marcy Houses, in Bedford-Stuyvesant (where Jay Z, famously, sold crack cocaine in the 1980s).

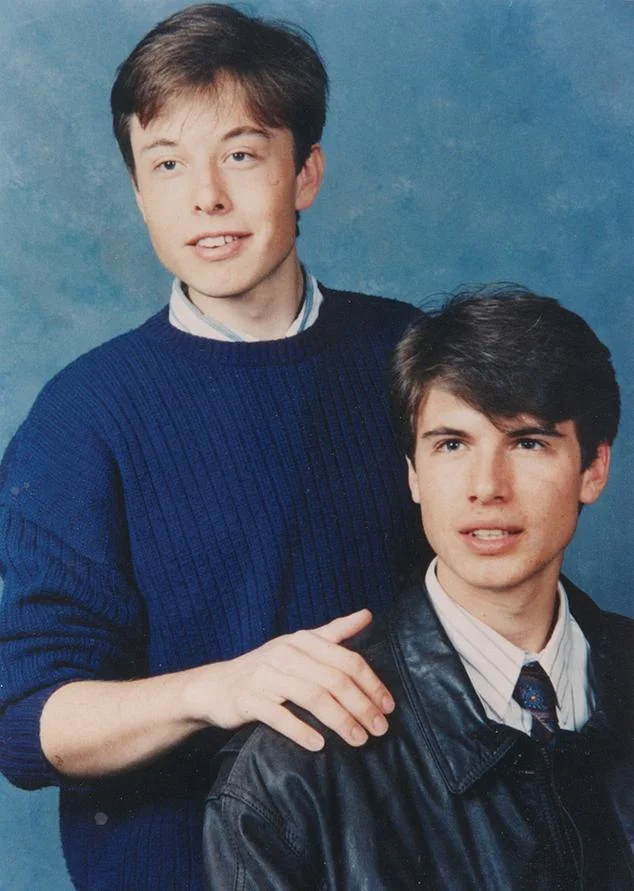

Clockwise from far left: Elon (left) and Kimbal, at 17 and 16. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIMBAL MUSK

Entrepreneurial drive runs in the family for Kimbal, 44, a close confidante of his brother, Elon, and a board member (and major shareholder) at Tesla and SpaceX. “If something happens to me, he can represent my interests,” says Elon of his kid brother (one year younger) and worst-case-scenario proxy. “He knows me better than pretty much anyone else. He’s got good judgment overall and has been put through the ringer a few times.”

Kimbal, a veteran of the tech world, has in recent years shifted his focus to food—or the “new internet,” as he called it in a 2015 TEDx Talk. With the missionary zeal his brother brings to electric sports cars and private space travel, Kimbal has launched a series of companies designed to make a lasting impact on food culture, through restaurants, school gardens and urban farms.

‘‘I want to reach a lot of people. We’ve put too much emphasis on preciousness with food.’’

—Kimbal Musk

Since 2010, a nonprofit venture supported by the Musk Foundation has built hundreds of Learning Gardens in American schools, installing self-watering polyethylene planters where kids learn to grow what they eat. Meanwhile, his Kitchen family of restaurants—promising local, sustainable, affordable food—is rapidly expanding across the American heartland, with five locations opening this year, including new outposts in Memphis and Indianapolis. Kimbal hopes to have 50 “urban-casual” Next Door restaurants, 1,000 Learning Gardens and a battalion of container farms by 2020. “I want to be able to reach a lot of people,” he says. “I think we’ve put too much emphasis on preciousness with food—and the result is a real split between the haves and have nots.”

The Musk brothers grew up in South Africa during the last gasp of the apartheid era. Kimbal, the more gregarious sibling, got his start selling chocolate Easter eggs at a steep markup door-to-door in their Pretoria suburb. “When people would balk at the price, I’d say, ‘You’re supporting a young capitalist,’ ” he recalls. While Elon spent hours programming on his Commodore VIC-20, Kimbal tinkered in the kitchen. “If the maid cooked, people would pick at the food and watch TV,” he says. “If I cooked, my dad would make us all sit down and eat ‘Kimbal’s meal.’ ”

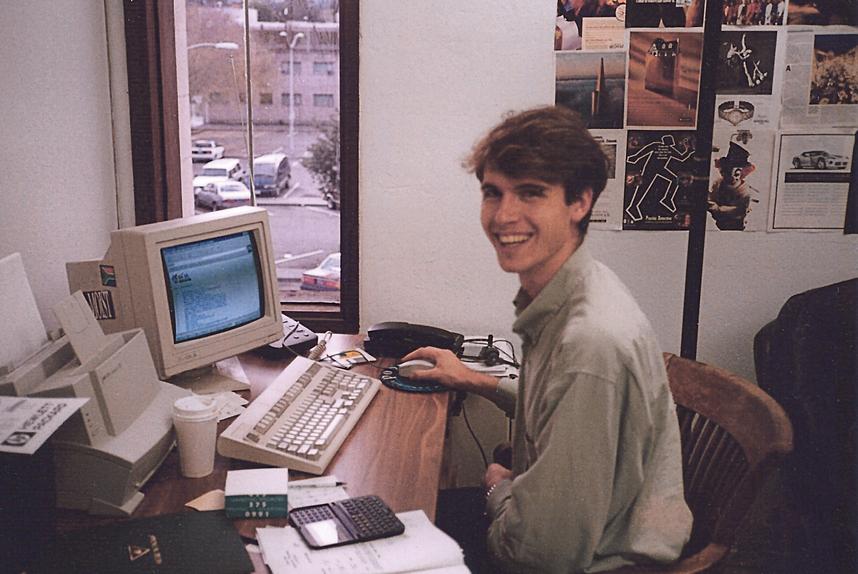

Kimbal in the kitchen, 2002. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIMBAL MUSK

After high school, the brothers moved to Canada, both enrolling, for a time, in Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario (Kimbal studied business, Elon physics). In 1995, they founded a company together in Palo Alto, California, the online business directory Zip2. “I had come over as an illegal immigrant,” Kimbal says of the move. “We slept in the office, showered at the YMCA.”

The brothers were close but also intensely competitive. Sometimes work disputes would get physical. “In a start-up, you’re just trying to survive,” says Elon. “Tensions are high.” Once they could afford it, Kimbal cooked for the whole Zip2 team in the apartment complex they shared. In 1999, the Musks sold their business to Compaq for $300 million. Though they remain investors and advisers in each other’s companies, their official partnership ended there.

HOME FRONT | Kimbal’s mother, Maye (right), with her parents at the family farm near Pretoria, South Africa, 1978. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIMBAL MUSK

After Elon launched the payment site that would later become PayPal , Kimbal, on a lark, enrolled in cooking school. He finished his studies at the French Culinary Institute in New York in late summer 2001 with no intention of pursuing a career in food. A few weeks later, after two planes flew into the Twin Towers, he spent the next six weeks as a volunteer cook, feeding firefighters out of the kitchen at Bouley. At the end of it he wanted nothing more than to open his own restaurant. “After that visceral experience, I just had to do it,” he says.

Searching for a dramatic change in scenery, post-9/11, Kimbal and his new wife at the time, lighting artist Jen Lewin, set out on a cross-country road trip looking for a place to put down roots and raise a family. They settled on Boulder, Colorado, “a walkable town, a great restaurant town,” says Kimbal at the 140-year-old Victorian home they bought there in 2002 (they have two sons and have since divorced).

The house he now shares with food-policy activist Christiana Wyly—with a cherry-red Tesla parked out back—is a few blocks from the original Kitchen, an American bistro he launched in 2004 with chef-partner Hugo Matheson, a veteran of London’s River Cafe. The Kitchen sourced ingredients from local farmers, composted food waste, ran on wind power and used recycled materials in its décor. For its first two years, the two partners worked full-time as co-chefs, taking turns composing the menu, which changed every day. Eventually, the daily grind became too much for Kimbal. “I got a little bored with the business,” he says.

Kimbal in his Zip2 office, 1996. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIMBAL MUSK

By 2006, he was back working in tech, as CEO of a social-media-analytics start-up. The Kitchen might have remained a sideline if not for a series of unlikely events. On February 10, 2010, at a TED conference in California, he listened to Jamie Oliver admonish America for its childhood obesity problem. Four days later, while barreling down a slope in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Kimbal flipped his inner tube and broke his neck. In the hospital, wondering if he’d ever walk again, he began to reconsider his life, with Oliver’s comments rattling around in his head. “The message I heard was: The people who have no excuse should be doing something about this—and I was one of those people,” says Kimbal. “I told myself, If I get through this I’m going to focus on food and doing things at scale.” Apart from losing some feeling in his fingers, he made a full recovery.

Since then Kimbal has become a cheerful crusader for “real food,” as he calls it, sharing his message on the lecture circuit. “He’s a compelling speaker,” says food writer and activist Michael Pollan. “Particularly in his passion for kids, his recognition that if we’re going to change our approach to eating in this country, it’s about showing kids where food comes from, how to grow it, how to prepare it.”

“In 2004, there were very few local farmers that would work with us,” says Kimbal. “We opened the Kitchen before farm-to-table was a term. We showed that you could be busy and profitable while creating a new supply chain. Now there’s a huge backlash against processed food, industrial food. Real food is simply food you trust to nourish your body, nourish the farmer and nourish the planet.”

Bowery Reinvents Farming for Urban Landscapes

Bowery Reinvents Farming for Urban Landscapes

May 26, 2017 by Annie Pilon In Green Business

Agriculture is one of the oldest industries out there. But businesses are still finding new ways to update this industry in order to get fresh produce to the people who need it most.

Bowery Indoor Farming

Bowery is one such business. The farming startup made its goal to get fresh produce to consumers in big cities in a sustainable way. To achieve that goal, the company uses hardware and proprietary software to set up vertically stacked gardens that operate indoors year-round.

This solves a couple of different problems. First, many city dwellers live in food deserts, or places where there isn’t a whole lot of fresh produce available. Secondly, traditional agriculture uses massive amounts of water and other resources. And Bowery’s high tech approach allows the business to function in a way that’s both sustainable and not reliant on outdoor weather.

A Great Example of Innovation

What this business shows is that you can put a new spin on almost any industry, as long as you’re willing to get a little creative. Throughout the years, people have come up with plenty of new tools to update agriculture or make certain processes more efficient. But if you’re willing to look at things in a new way, and innovate based on your observations, you can still find ways to update almost any business model.

Image: Bowery

Canadian Microgreens Grower Makes Impact Within The Lettuce Category

Canadian Microgreens Grower Makes Impact Within The Lettuce Category

Small but mighty: microgreens are fairly new in the produce category, but they’re already being widely embraced in foodservice and in consumer’s homes. For what they lack in size, they make up for in a powerful flavor profile.

Large inventory on small footprint

Greenbelt Microgreens grows a wide inventory on its mere 6.5 acres. Of that, 4.5 acres is located in Ontario, Canada and 2 acres in Maple Ridge, BC. Owner, Ian Adamson began researching and perfecting the viability and production of microgreens in 1998 and was ready to open for business in 2010. Seven years were spent in perfecting the process and achieving proper nutrient-rich soil to grow strong, healthy greens. The proprietary soil mixture comes from a farm in Quebec. “That’s how we get the shelf life, because of the quality of the soil,” said Michael Curry, Vice President of Greenbelt Microgreens.

Fast growth cycle, long shelf life

Maintaining a proper cold chain is key – it’s all about food safety; the company is Canada GAP certified. Curry says their 13-day shelf life is key. Movement and processing of the cut greens right into cold storage, plus the ability to grow organically is something he says retailers are looking for. “That’s why we’re jumping on it,” he said, noting that 80 per cent of the organic product sold in Canada is imported.

It’s an opportunity for Greenbelt Microgreens to harness, and they’re able to grow year- round under glass, which mimics growing in an open field. “It’s a 10-day growth cycle,” Curry explained. “We can grow an incredible amount in an acre, year round.” He noted that they’re experimenting the implementation of LEDs. “We’re all about soil and sunshine but LEDs are proven very effective in the winter to keep the growing cycle the same - yields as well,” he said. With the reduction in sunshine this past winter, it’s an important investment, since last January he said there was only about 50 hours of sunlight for the month.

Living lettuce and wide range of greens

Part of their inventory includes organic living lettuce as well as their namesake organic microgreens: arugula (the most popular), basil, buckwheat, broccoli, cilantro, radish, daikon radish, kale, pea shoots, red choi, red mizuna, red radish, shunkigu, sunflower and wheatgrass. At one time it seemed like the idea of consuming what should be a full head of broccoli harvested after only 10 days was unheard of, but thegoal is to get the customer to think of their products as a whole salad, whether it’s a clamshell of the mixed microgreens, mixed lettuce or a head of living lettuce.

Living lettuce is sold in sleeves, which customers can take home, keep watered and harvest whenever they wish. The microgreen salads come in four different mixes. “That’s totally unique – nobody’s got that on the market,” said Curry. “Millennials seem to love having plants growing in their kitchen.” Customers are making friends with salad.

For more information:

Michael Curry

Greenbelt Microgreens

Ph: 416 710 7547

China Subverts Pollution With Contained Vertical Farms – And Boosts Yield

China Subverts Pollution With Contained Vertical Farms – And Boosts Yield

Agriculture, China, Eat & Drink, News, Urban Farming

- by Lacy Cooke

Around one fifth of arable land in China is contaminated with levels of toxins greater than government standards, according to 2014 data. That’s around half the size of California, and it’s a growing problem for a country that faces such levels of pollution they had to import $31.2 billion of soybeans in 2015 – a 43 percent increase since 2008. Scientists and entrepreneurs are working to come up with answers to growing edible food in a polluted environment, and shipping container farms or vertical gardening could offer answers.

The toxins in China’s environment have made their way into the country’s food supply. In 2013, the Guangdong province government said 44 percent of rice sampled in their region contained excessive cadmium. Around 14 percent of domestic grain contains heavy metals such as lead, arsenic, and cadmium, according to research from scientists in 2015.

Related: Arctic town grows fresh produce in shipping container vertical garden

Could shipping container farms offer a way around this contamination? Beijing startup Alesca Life Technologies is testing them out. They turn retrofitted shipping containers into gardens filled to the brim with arugula, peas, kale, and mustard greens, and monitor conditions remotely via an app. They’ve already been able to sell smaller portable versions of the gardens to a division of a group managing luxury hotels in Beijing and the Dubai royal family.

Alesca Life co-founder Stuart Oda told Bloomberg, “Agriculture has not really innovated materially in the past 10,000 years. The future of farming – to us – is urban.”

And they’re not alone in their innovation. Scientist Yang Qichang of the Institute of Environment and Sustainable Development in Agriculture at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences is experimenting with a crop laboratory, testing which light from the visible light spectrum both helps plants flourish and uses little energy. His self-contained, vertical system already yields between 40 and 100 times more produce than an open field of similar size. He told Bloomberg, “Using vertical agriculture, we don’t need to use pesticides and we can use less chemical fertilizers – and produce safe food.”

Via Bloomberg

Images via Alesca Life Technologies

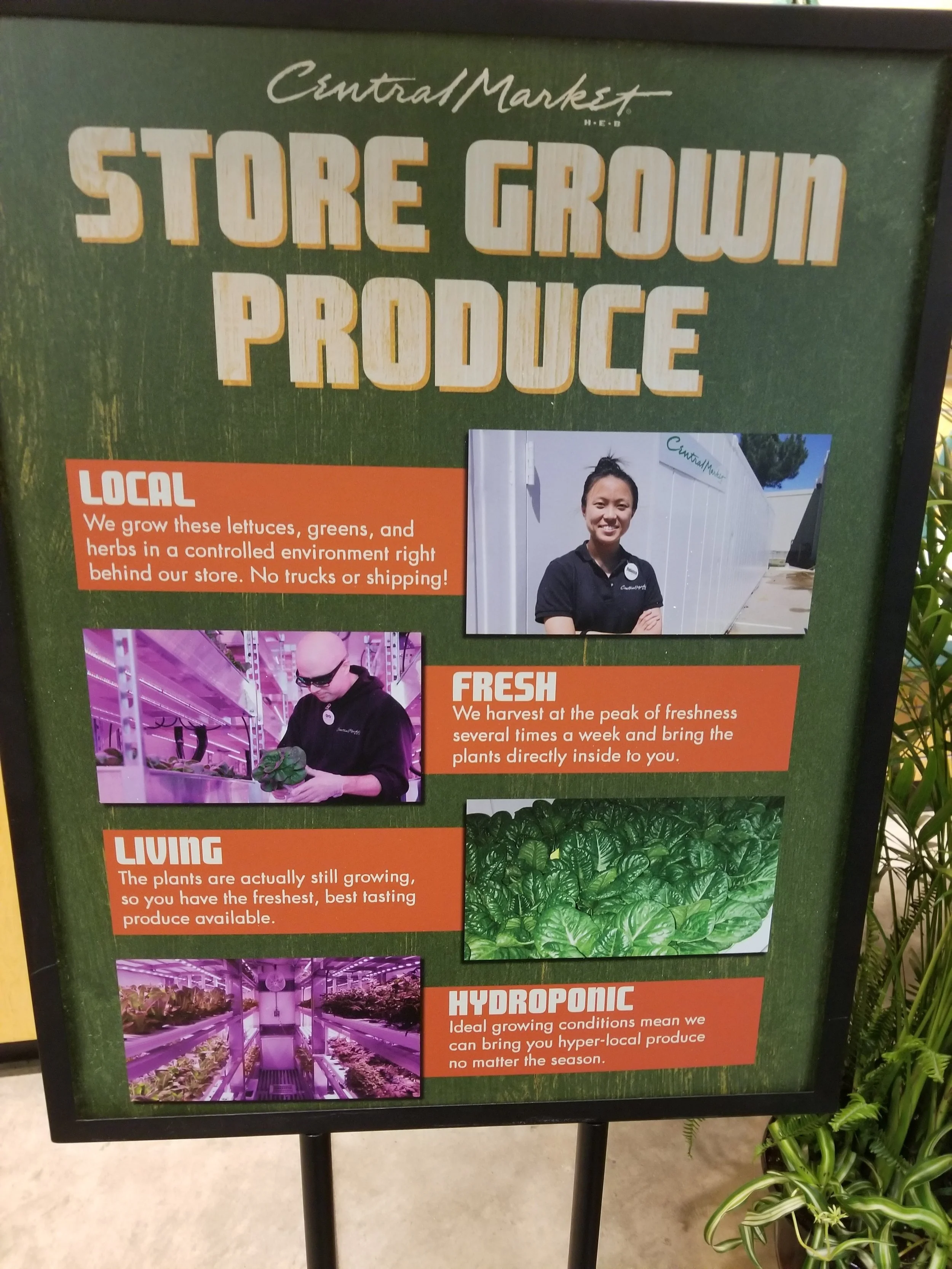

H-E-B-Owned Central Market Partners With CEA Advisors and Growtainer® For Store Grown Initiative

H-E-B-Owned Central Market Partners With CEA Advisors and Growtainer® For Store Grown Initiative

Friday, May. 19th, 2017

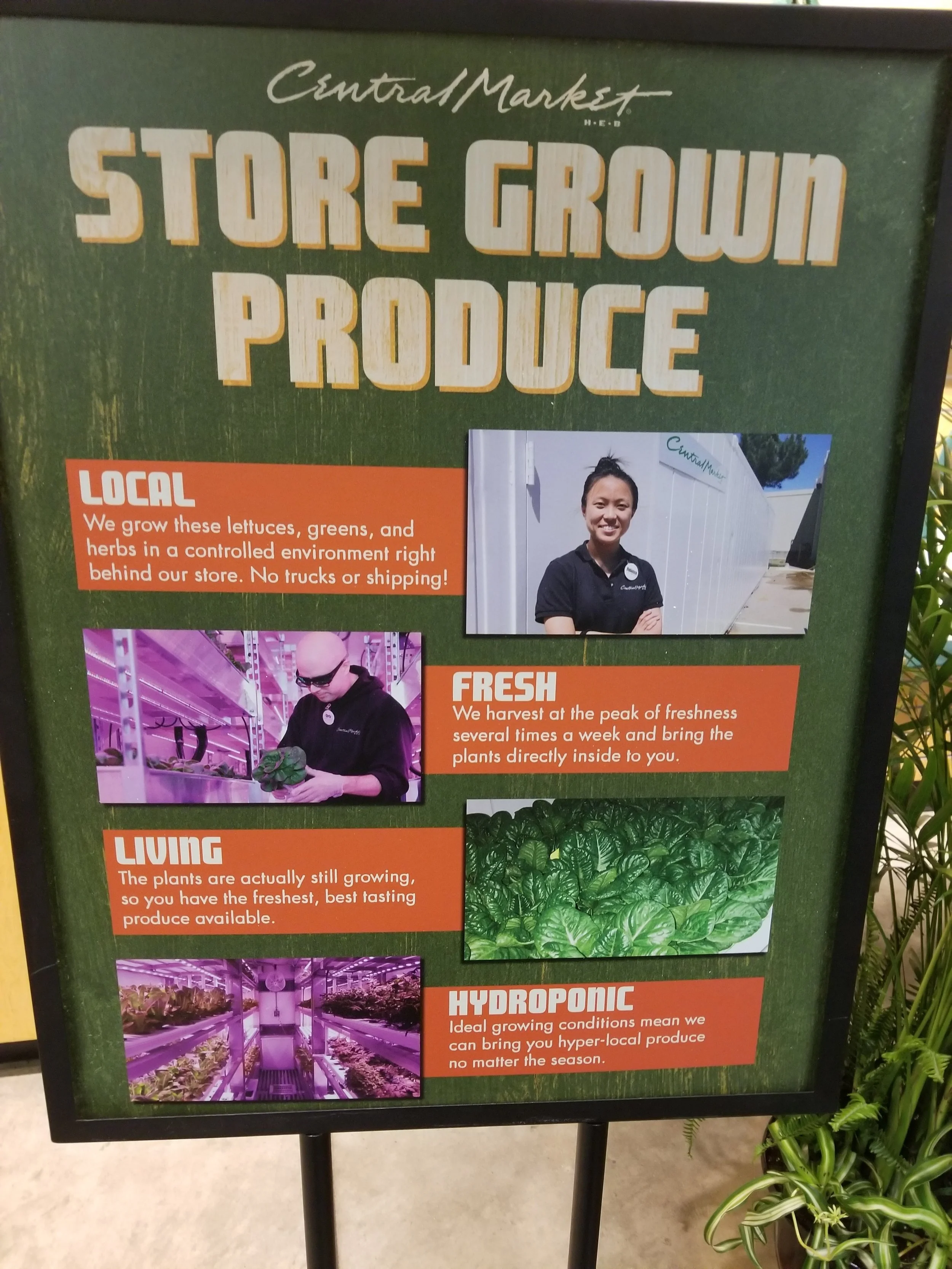

DALLAS, TX – After more than a year of planning between Central Market’s Produce Marketing team and CEA Advisors, the two companies have announced the completing of the first custom built onsite production Growtainer®. Central Market’s new Store Grown Produce program is in effect and turning out fresh leafy greens, herbs, and spices for Central Market customers in Dallas.

Glenn Behrman, Founder, Greentech Agro LLC and CEA Advisors LLC.

“We spent over a year discussing [Central Market’s] concerns and objectives, and when I was sure we were all on the same page, we began the design and manufacturing process” said Glenn Behrman, Founder of Greentech Agro LLC and CEA Advisors LLC.

The state-of-the-art 53-foot custom-built Growtainer provides 480-square-feet of climate-controlled vertical production space designed for maximum efficiency and food safety compliance. The miniature production facility features a dedicated proprietary technology for ebb and flow irrigation and a state-of-the-art water monitoring system, and its Growracks® are equipped with energy efficient LED production modules specifically designed for multilayer cultivation.

Growtainer

According to a press release, Central Market—the Texas-based upscale grocery banner owned by H-E-B—is currently using its Growtainer setup in an effort to “produce the freshest, unique, gourmet leafy greens and herbs for Central Market customers at the retail level.” The release noted that Central Market and CEA Advisors have worked closely with Chris Higgins and Tyler Baras of premier horticultural supplier Hort Americas to train the Central Market associates to operate a food safety compliant, climate controlled, LED-lit, multi-layer vertical indoor production environment.

Central Market storefront

“CEA Advisors is proud to be working with the Produce Team at Central Market, all committed to innovation and focused on food safety, unique products, and the customer experience” said Behrman.

This Texas Supermarket Is Growing Its Own Veggies In A Shipping Container Farm

This Texas Supermarket Is Growing Its Own Veggies In A Shipping Container Farm

Agriculture, Carousel Showcase, News, Sustainable Food, Urban Farming

A Texas chain of supermarkets isn’t just in the business of selling vegetables; it’s growing them, too. Based in Dallas, the H-E-B-owned Central Market has joined forces with Controlled Environment Agriculture Advisors, a self-described “horticulture disrupting” firm, to raise some of its produce in a custom-built onsite shipping container—a first for an American food retailer.

The 53-foot-long “Growtainer” features 480 square feet of climate-controlled and food-compliant vertical space designed to achieve a higher yield in a shorter time than conventional methods, according to GreenTech Agro, the system’s manufacturer.

Related: Belgian supermarket unveils plan to sell food grown on their own rooftop garden

“We spent over a year discussing [Central Market’s] concerns and objectives, and when I was sure we were all on the same page, we began the design and manufacturing process,” said Glenn Behrman, founder of GreenTech Agro and CEA Advisors, in a statement.

The miniature farm comes with a modular, self-contained series of LED-lit aluminum “GrowRacks” that supports any number of cultivation levels.

Related: Pop-up shipping container farm puts a full acre of lettuce in your backyard

It also offers an intelligent water-monitoring system, as well a zoned irrigation system that meets the needs of different varieties of produce at different stages of growth.

The Growtainer is part of Central Market’s efforts to “produce the freshest, unique, gourmet leafy greens and herbs for Central Market customers at the retail level,” the supermarket said. The hyper-local vegetables are marketed under the label “Store-Grown Produce.”

Related: Freight Farms are super efficient hydroponic farms built inside shipping containers

“CEA Advisors is proud to be working with the Produce Team at Central Market, all committed to innovation and focused on food safety, unique products, and the customer experience,” Behrman added.

Sustainable Indoor Farm Aims To Grow The Most Delicious Produce

Sustainable Indoor Farm Aims To Grow The Most Delicious Produce

A San Francisco startup is creating an indoor vertical farm that aspires to produce crops more efficiently and sustainably than traditional farms

- 25 MAY 2017

Indoor vertical farming startup Plenty wants to transform the way greens are produced. The company, headquartered in San Francisco, has created 20-foot towers of rare herbs and greens—including special kinds of basil, chives, mizuna, red leaf lettuce and Siberian kale—that are not frequently available at the average grocery store because of their high production costs.

“When you’re not outside and you’re no longer constrained by the sun, you can do things that make it easier for humans to do work and work faster, and for machines to work faster,” Plenty CEO and co-founder Matt Barnard told Fast Company. The company claims it can grow crops up to 350 times more effectively than conventional farms in a given area. Indoor vertical farms are more energy- and space-efficient, Barnard says, producing the same output as fairly large farms in a far smaller space. He believes that the indoor farming process, once perfected, may become more sustainable than traditional farms.

Plenty is attempting to put ever-improving technology toward its success and plans to build farms near large cities so it can fit into existing supply chains that deliver to city limits. Faster delivery means better food, preserving both flavor and nutrients. Indoor farming also has the potential to be more sustainable by using solar energy and cutting down on the costs and pollutants of traditional supply chains.

Can Hydroponic Lettuce Save Coal Country?

Story by Otis Gray

Illustration by Jia Sung

5.3.17

Can Hydroponic Lettuce Save Coal Country?

Young people tend to talk about “getting out” of McDowell County, West Virginia. But one radical farmer is bringing life back to his struggling hometown.

This story is a collaboration between Narratively and Hungry, a podcast about the food we eat, the people who make it, and the inspiring stories surrounding food you don’t usuall

* * *

Joel McKinney, 33, is thick and tall, with tattooed arms and a backward baseball cap. There’s a restless demeanor exuding from beneath the militaristic dude-ness he must have picked up during his time in the Navy. He slides open the greenhouse door and a warm draft washes out.

On the north side of the greenhouse are two long rows of eight-foot-tall bright white PVC towers standing at attention. From each PVC pipe explodes scores of violently purple and green heads of lettuce growing vertically up the tube. Each plant sits askew in a little cup fitted into its respective hole in the tower. A steady trickle of electricity and water reverberate in the warm tunnel. These are McKinney’s hydroponic lettuce towers.

“People are so stuck on traditional agriculture, and that’s fine, it’s all great. But I’m not growing out, I’m growing up,” he says. “What I’m doin’ with the towers, it’s not just about hydroponics to me. It’s not just about growing food. To me, this thing embraces change.”

A scene off the main road going through McDowell.

The vibrant, futuristic setup is entirely unexpected in a place like McDowell, and that’s kinda the point for McKinney. McDowell is a remote coal county tucked away in rural West Virginia. Back in the late fifties when coal was booming, McDowell’s population was over 100,000. In 2017 that number has dropped below twenty thousand. It has made headlines over the last decade for its daunting economic hardships, rampant opioid use, and most recently, its overwhelming support for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election. But these headlines fail to cover creative people like McKinney who are responding to those circumstances.

McKinney cradles a deep green head of lettuce between his fingers. The towers each sit atop big black buckets with neat tubes running in between, making the greenhouse look like a room full of computer servers as curated by an obsessive farmer. Each bucket is filled with a nutrient-rich solution – water loaded with natural stuff the plants need to grow. A pump system carries the solution to the top of the tower, where it trickles down inside and is directed to the roots of each plant. The roots dangle into the passing solution and soak it all up. The solution then falls back to the bucket, and is cyclically pumped up to the top again. While the physics of it are simple, McKinney has taken extreme care to make these towers as efficient as possible.

McKinney served in the Navy as a machinist mate, and was honorably discharged after spending 2003 to 2007 aboard the USS Trenton. He went in as an engineer, devouring any manuals he could find and ravenously learning the technology of the ship’s systems. The old-school tech used on the ships – the steam-powered stuff, the electronics – captivated McKinney. He excelled among his peers and became the first E-3 Seaman with the title of qualified firearm supervisor in the 35-year history of the USS Trenton. He deployed to Lebanon, Beirut, facilitated an Israeli evacuation, traveled up and down Latin America, and has seen most of the United States.

Joel McKinney with his hydroponic towers.

Something you’d notice driving through McDowell is that there aren’t a whole lot of people McKinney’s age. You generally see children, and then people who look to be at least forty. This is in large part due to the dramatic decline of jobs over the last fifty years, which has forced adults to flee to urban areas in West Virginia, Ohio, and Kentucky, often sending money back to kids they left in McDowell to be raised by grandparents. The younger generation has seen the county rocked by floods, a recession, and an epidemic of opioid addiction that has deterred those who leave from ever coming back.

“I was forced to adapt,” McKinney says. After the Navy, McKinney went to work for the railroad. During the next seven years, he honed his skills in electrical engineering and operating machinery, but quickly plateaued and wound up unchallenged by the job. He got bored and started drinking heavily – “I have a really addictive personality,” he explains – and got a DUI. The DUI led to a suspension from his railroad job, during which time he wound up back in McDowell helping his mom Linda at their food bank. She had one of these towers lying around so, he did what he does best: He started tinkering.

As the coal industry declined, many people here turned to traditional farming for food and profit, but the runoff from the mines made it tough to grow anything, much less anything healthy. Byproducts like arsenic, selenium, mercury, and compaction often ravage otherwise fertile soil in coal-heavy towns. Even if you do produce enough crop to sell, McDowell is secluded enough that the time and money spent on transportation to a viable market would eat up any profits. Hydroponics provided McKinney a way to farm without using the contaminated water, and the cost is so low that folks in McDowell can afford to buy the resulting produce themselves, cutting out the need for costly transportation.

McKinney calculates that the 440 heads of lettuce he has growing in this roughly twenty-by-five-foot area take up less than one-eighth of the space it would take to grow in the ground and uses ninety percent less water. This means that farmers using McKinney’s systems could bypass tainted water, produce year-round, and multiply their crop by ten times each harvest. All without using pesticides, GMOs, or growth chemicals.

The local public school has become one of McKinney’s accounts and buys lettuce for their lunches. As part of the deal, he gets to teach a raucous group of six-year-olds about hydroponics by installing a tower in one of the classrooms. “Man, working on the railroad is a lot like working with kindergartners. But I’m a structured guy, I work with bullet points – so when you go from the military to working with kids. . .”

He fiddles with a tube feeding into one of the buckets and laughs. “I learn a lot from them. I can’t go in with kids and teach like, tropism and nitrogen cycles and covalent bonding, but you go in with kindergartners and you say, ‘okay well, this is lettuce. This is what lettuce should taste like.’”

“Oh my gosh, he thinks he’s horrible with the kids and he’s fantastic. I tell him he needs to be a teacher,” Kimball Elementary school teacher Sarah Diaz says. “Many of our kids are not exposed to varieties of food,” she adds. “So even simple things like a salad with homegrown vegetables and a homemade dressing, that’s a big deal. They love the flavor. We had so many kids coming away saying ‘I really like vegetables!’ Whereas before, they wouldn’t touch it!”

Diaz says the learning doesn’t stop after kindergarten, it has to become embedded in McDowell’s culture. “If we can get people like Joel to plant a fire in these kids and develop a program that allows them to grow with these systems and grow into it, I can see huge potential for change in the next couple generations.”

The question is whether people in McDowell will embrace the new system. McKinney admits that people in McDowell can be a tough bunch to work with because of their deep traditions and weathered attitudes. Folks in McDowell even describe themselves as “good people, but defensive.” This has a lot to do with decades of their livelihood (coal and other big industries) being outsourced, broken promises from the government, and media outlets that portray their home as a hellish wasteland waiting for politicians to come save them.

McKinney says the people of McDowell constantly surprise him with how on board they are with the hydroponics. “People can be pretty close-minded, but hey, man, I’ve been all over the world, these are very good people here in Appalachia.”

Hydroponic Lettuce Towers in Joel McKinney’s greenhouse.

Hydroponic projects in big cities get most of the media attention, focusing on people growing indoors without a lot of space. But it’s wildly useful in rural areas too. “This is absolutely sustainable here,” McKinney says. “It’s something anybody can do and now I’m training people of all ages how to pick this thing up and run with it.”

“The hydroponics is kinda’ a visual for the concept of change. I wanna bring some change into a rural poverty situation,” McKinney says, nodding his head and looking at a crop. “People will say opportunities don’t exist here. And I say, ‘you’re absolutely right. Create it.’ And that’s what we’re doin’, we’re creating a market.”

His operation is applicable to countless rural economies throughout Appalachia and the rest of the U.S. that are primed with mechanically-minded industry families who are in need of better food and sustainable incomes. Coal will not come back permanently. McKinney knows this, and the folks of McDowell know this too. Transitioning into simple yet futuristic agriculture could revolutionize their narrative.

McKinney shuts the door to the greenhouse. “Look,” he says frankly as he walks back across the cold lot. “I don’t believe that lettuce and strawberries are gonna save McDowell.”

Hydroponics are a beginning. An example that there is more. “Kids here, especially once they hit the junior high age, they just feel like there’s no hope, there’s no chance for change. So as soon as they can they say ‘let’s get out of McDowell.’

“I’m really trying to change that logic as best I can. I don’t think it’ll happen in my generation, but I’m hopin’ to kinda be the spark that initiated some change in this place ’cause I believe it can happen. It’s just gonna take a long time.”

Listen to the extended audio version of this story – featuring Senator Bernie Sanders – on the Hungry podcast. You can subscribe to Hungry on iTunes, Stitcher, your podcast app, or via www.hungryradio.org.

The Spacepot Hydroponic Planter Brings NASA Grade Farming To Your Kitchen

The Spacepot Hydroponic Planter Brings NASA Grade Farming To Your Kitchen

May 20, 2017

Qhilst cooking with fresh herbs is a simple pleasure, most novice urban farmers have never known a basil pot to last more than a few months. that’s why futurefarms have turned to NASA’s hydroponic farming techniques to revolutionize herb growing for the not-so-green-thumbed. reforming space-grade science into an elegant kitchen planter called a ‘spacepot’, futurefarms have set out to downsize the extraterrestrial farming technique into an elegant tabletop planter that grows perfect herbs in just 5 weeks, with almost zero maintenance.

hydroponic farming—that’s the art of growing plants without soil—was first popularized by NASA. widely associated with futuristic space gardens, by cutting out the soil from the equation hydroponic farms provide their plants directly with nutrients, cutting out the middle man to create bigger, healthier shrubs that grow much faster than their soil-situated counterparts. maybe it’s the their extraterrestrial connotoations, or the fact they always seem to be kitted out with endless complicated pumps and tubes, but when it comes to hydroponic farming, until now it’s been widely accepted that you do, indeed, need to be a rocket scientist to master the technique. and that’s a stigmatism futurefarms set out to change with their ‘spacepots’—elegant, hydroponic planters that bring the benefits of soil-free farming to the masses.

branded ‘hydroponics beautifully simplified’ the spacepot required no pumps, no electricity, and no extra parts to maintain. by mixing space-age technology with cutting edge design, futurefarms have crafted a planted that delivers all the benefits of hydroponics without any of the maintenence. by using the kratky method—the simplest, most hands-off way for gardening—all the spacepot requires from you is to fill the reservoir with water and nutrients, plant a seed, and watch your beautiful plant flourish in just five weeks. fashioned of high-clarity acrylic and food-grade PET,the planter’s aesthetic is designed to represent its functionality—easy and simple.

futurefarms–the LA based startup behind the futuristic and fashionable approach to gardening–comprises a team of designers, creators, and researches leading the field of personal hydroponics. ‘on a macro scale,’ they explain, ‘our mission is to have hydroponics be a part of everyone’s lives because we believe it makes us smarter, and more conscious of our health and well-being.’

beatrice murray-nag I designboom

may 20, 2017

Indoor Farming: On To Pastures New

Indoor Farming: On To Pastures New

24 May 2017 | By Mia Hunt

In the drive for sustainability, new operators are looking to indoor farming to bring food closer to consumers.

Indoor farming - a low-energy, low-water-use way of growing food - Source: Mandy Zammit

Asked to imagine a farm, most people will think of vast green fields filled with neat lines of crops, grazing animals and a tractor trundling along in the distance.

It’s an idyllic visualisation that would be shattered if you were told that the farm were, in fact, on an industrial estate on the edge of a major conurbation.

Say hello to indoor - or vertical - farming, an emerging sector that aims to produce food sustainably, without sunlight or soil and, crucially, close to the retailers that will sell it and the consumers who will eat it.

It is a concept still very much in its infancy, but if this new farming method takes hold, warehouse space will be high on the shopping lists of these new operators. So what is indoor farming? And what are operators’ requirements?

Indoor farming is sustainable and uses less transport. Those who are doing it now are the forward-thinking food producers - David Binks, Cushman & Wakefield

“This is very much a new, emerging sector,” says David Binks, a partner in the industrial team at Cushman & Wakefield.

“The thinking driving this trend is to move food production closer to the source of customers. It’s sustainable and uses less transport, which is a very positive thing. Those who are doing it now are the forward-thinking food producers.”

GrowUp Urban Farms is one such operator.

A year ago it opened Unit84, an indoor farm in an industrial warehouse in Beckton, east London, that had previously lain vacant for 18 months. It claims it is the UK’s first aquaponic, vertical farm.

The farm combines two well-established farming practices: aquaculture, a method of farming fish, and hydroponics, whereby plants are grown in a nutrient solution without soil. It is a low-energy, low-water-use way of growing food that is especially suited to high-density urban agriculture.

The farm’s 6,000 sq ft of growing space produces more than 20,000kg of salads and herbs - enough to fill 200,000 salad bags - and 4,000kg of fish each year. And according to chief executive and co-founder Kate Hofman, GrowUp’s next project will be “10 times bigger”.

“I set up GrowUp with COO and co-founder Tom Webster four years ago,” Hofman explains. “We have different career backgrounds - he was a sustainability consultant for an engineering firm and I was a strategy consultant - but we were both interested in making sustainable urban food production commercially viable.”

Food For Thought

The pair took over the warehouse at London Industrial Park in May 2015 and launched after a comprehensive six-month fit-out process.

“Our 600 sq m [6,500 sq ft] hydro room alone provides 8,000 sq m of growing space because we’re able to grow up as well as along,” says Hofman. “And because it isn’t dependent on environmental and climate factors, we can produce salads of consistent quality 365 days a year.”

Now that Unit84 is fully up and running, Hofman and Webster are looking ahead to their next project - a considerably larger farm for which the firm will soon work up a design that will enable it to make even more efficient use of space. This next farm will be the blueprint for a model that can be rolled out to many different locations on a franchise basis.

Indoor farming uses hydroponics, whereby plants are grown in a nutrient solution without soil - Source: Mandy Zammit

Hofman says a standard warehouse is the ideal place for vertical farming and lists requirements similar to those of light industry, including locations within easy reach of customers - GrowUp distributes all of its produce itself using electric vehicles - and with good access and packing space.

“From what I’ve seen, read and heard, these operators need decent utility access - predominantly renewable energy to power the artificial lights that are used in place of sunlight - although they require very little water, significantly less than a traditional farm,” says Binks. “They need to be heated and cooled efficiently. And because they use a degree of technology to support the growing methods, that may be a consideration in their requirements.”

Looking Up