Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Lakewood Hydroponic Farm Looks To The Future of Farming

Samantha Fox sfox@swiftcom.com June 7, 2017

Joshua Polson/jpolson@greeleytribune.com | The Greeley Tribune

Tommy Romano stands alongside some of lettuce being grown at Infinite Harvest, 5825 West 6th Ave. Frontage Road in Lakewood. The farm is a hydroponic vertical farm that produces year-round.

Lakewood Hydroponic Farm Looks To The Future of Farming

FARM TO SCHOOL

For the crops grown at Infinite Harvest, there’s a push to make them more available for those who might want them or simply those who haven’t heard of microgreens before.

Microgreens are mainly seen at fine dining restaurants, but like we saw with kale, it’s becoming more popular, even at the school level. Infinite Harvest is working with Natalie Leffler, who works with Greeley-Evans School District 6’s Farm to School program to get some of their products into schools.

In the early 2000s, Tommy Romano started to grow plants in his basement. He wanted to experiment with ways to efficiently grow food inside through vertical farming rather than the traditional way.

He experimented with different vegetables, such as corn. He would grow them indoors and stacked crops atop of other crops. For vertical farming, the point is to use less horizontal space, which can allow for farming in the middle of urban areas.

It took a lot of trial and error to find a way to efficiently farm indoors, but Romano was used to the scientific process, as he has a master's in aerospace engineering from the University of Colorado. He studied his process as a way to grow crops in space before realizing they would work on Earth, too. Once he felt his techniques were ready, he started Infinite Harvest, which opened January 2015 in Lakewood.

The farm grows 13 microgreens and lettuce. Microgreens are young vegetables greens. They're harvested before baby greens but later than sprouts. They can come from corn, celery, arugula and other vegetables and greens. They're not always the easiest to find, but microgreens might be an option for schools in Colorado soon. Romano is working with Natalie Leffler, head of Greeley-Evans School District 6's Farm to Schools program, to possibly start supplying schools with Infinite Harvest crops.

Microgreens are ideal for Infinite Harvest because the plants don't need to grow very high before they're harvested, which means more rows can be used. The way those at Infinite Harvest put it, the ceiling is the limit.

But that ceiling comes in handy, too. This past month, when Colorado was hit with rain, hail and snow, the microgreens and lettuce weren't touched by the elements.

That's the benefit of an indoor hydroponic vertical farm — the weather is controlled by technology.

"We don't actively manage a lot," said Nathan Lorne, operations manager. "We really rely on her."

The "her" in this scenario isn't a human, but the greenhouse control system. The system, run by software, controls how much water and nutrients the plants get, the temperature, humidity, carbon dioxide levels — anything that will affect the plants. The system is contained in a box filled with machines and wires that take notes on absolutely everything that happens in the greenhouse. In case something goes wrong, the control system will send a message to someone to come fix it.

'BEYOND ORGANIC'

Joshua Polson/jpolson@greeleytribune.com | The Greeley Tribune

Red and blue lights shine around Lacy Saenz as she works on packaging a head of lettuce Wednesday at Infinite Harvest, 5825 West 6th Ave. Frontage Road in Lakewood. The farm was inspired by Tommy Romano's work on a thesis at CU that involved growing crops on Mars.

Lorne said one of the benefits of having an indoor farm is the complete control over what the plants are exposed to. Even with the lighting the farm uses. They want to save as much energy as they can, so they use only blue and red spectrum lights — those are what the plants need for photosynthesis.

The farm pays about six times less than marijuana greenhouses pay in electricity costs each month. Pot is a good comparison because it is also grown in greenhouses.

Even more important for them, though, is what the plants aren't exposed to.

Before even going into the farm, you enter an air cleanser room. Air is circulating and it's where visitors put on hair nets, hats, shoe covers or the specific farm shoes. This helps prevent some unwanted outside elements from getting in. There are traps that attract bugs to keep them from going in, too.

Because there aren't bugs or anything else in the farm aside from what is planned, Infinite Harvest doesn't use genetically modified plants, and there isn't a need for pesticides, either.

Even organic farms will use some sort of organic pesticide or spray to get rid of weeds or pests. Infinite Harvest doesn't have to.

Even with the organic trend, Romano said there aren't plans to apply to be organically certified. On one hand, the "Colorado Proud" label means more.

And on the other hand, "We're beyond organic," Romano said.

KEEP MOVING FORWARD

Joshua Polson/jpolson@greeleytribune.com | The Greeley Tribune

The rows and stacks of crops rise above Tommy Romano as he stands on the floor of the hydroponic-vertical farm Wednesday at Infinite Harvest, 5825 West 6th Ave. Frontage Road in Lakewood.

Romano made clear the purpose of this farm isn't to outdo farming. It's an ongoing science experiment in some ways. This isn't something that has been done before, and some of the technologies are relatively expensive.

There are a number of worries and problems farmers face, and Infinite Harvest looks to find solutions for them, Lorne said.

"Everyone here loves the romance of traditional farming," he said.

With the use of technology and indoor operations, Infinite Harvest has only 18 employees for their operation. They're not harvesting mass amounts of food at a time, but they're able to harvest food year-round.

But one of the most important roles is one most farms don't really need: a software engineer.

Romano said they're looking to expand, but they don't want it to be a big leap from what they're doing now. They want to take lessons learned and improve upon them a little at a time.

"There is no textbook," Lorne said.

And that's why Romano doesn't see Infinite Harvest as a competing entity, but as the next forward step in the industry.

"The traditional ways aren't fulfilling (the holes left by problems)," Romano said. "If we held to the same traditions of farming. … We'd still be riding horses right now. We're helping it take the next step."

Samantha Fox is a reporter for The Fence Post. She can be reached at sfox@thefencepost.com, (970) 392-4410 or on Twitter @FoxonaFarm.

Urban Farming Insider: Penny McBride, Founder Vertical Harvest Jackson Hole

We caught up with Penny McBride, founder of Vertical Harvest Jackson Hole, to discuss the challenges of running a commercial urban farm, why the best greenhouse engineers are from Europe, and much more!

Urban Farming Insider: Penny McBride, Founder Vertical Harvest Jackson Hole

We caught up with Penny McBride, founder of Vertical Harvest Jackson Hole, to discuss the challenges of running a commercial urban farm, why the best greenhouse engineers are from Europe, and much more!

Introduction

Jackson, Wyoming is home to one of the world’s first vertical greenhouses located on a sliver of vacant land next to a parking garage.

This 13,500 sq. ft. three-story stacked greenhouse utilizes a 1/10 of an acre to grow an annual amount of produce equivalent to 5 acres of traditional agriculture.

Vertical Harvest sells locally grown, fresh vegetables year round to Jackson area restaurants, grocery stores and directly to consumers through on-site sales. Vertical Harvest replaces 100,000 lbs of produce that is trucked into the community each year.In addition to fresh lettuce and tomatoes, Vertical Harvest produces jobs, internships and educational opportunities.

The greenhouse employs 15 individuals with intellectual and physical disabilities. Click here to learn more about our employment model.

Source: Mountain Magazine

Interview

UV: Can you talk about how Vertical Harvest started and your experience with that and how you got into the arena and kind of the background story?

Penny: Sure. I had been working as a consultant on a couple of different community projects...this was back when the pine bark beetle epidemic started and the forest service was looking for a lot of different ways to utilize biomass. That's where I kind of got a baseline understanding of what was possible from the biomass side.

Then from the greenhouse side, I was working with a team of experts that was hired to look at building a year-round greenhouse to be heated with biomass.

Unfortunately the project didn't happen, largely because this was around 2008

when the economy tanked. The people that I was working with had worked on greenhouse projects that were kind of functioning as community centers also. Mostly one was, it's in Boston, and it was helping to employ women, single mothers, and train them.

It was really exciting to me to see what was possible. My background does come

from this desire to create businesses and community enhancement projects that

really are tied to more than just one thing. It's not only a business, but it's

also a business that creates food and is just a much more circular model.

Around that time, I got a call from a case manager who is the person who actually is our employment facilitator now. She called asking if I had jobs for any of her clients, with any of these projects that I was spearheading.

I didn't think I did, but what it did spur me to do was start looking at the possibility of an urban center greenhouse. A greenhouse where people who couldn't drive could get to work by taking public transportation, something that seems a little more core to the community.

I started holding stakeholder meetings to see who might be interested. Really I thought it would be more of a community run greenhouse and not the business that it is today. That's really where (Vertical Harvest Jackson) kind of got its early legs.

UV: Could you talk about how you gained the technical side of (urban and vertical farming)? Some people are looking to grow something on their kitchen counter and some people have larger aspirations, but (either way) they (often) don't know where to start.

Penny: You know, I grew up on a farm and a ranch in Colorado. Not that that made me a hydroponic expert by any means, but I did kind of understand these plants and growing because the farm was started by my grandfather and it so it was really something I understood inherently to a certain degree.

But through the consulting work that I had been doing, I knew this man Paul Sellew, whose family started Backyard Farms, which was at the time the second largest hydroponic tomato producer in the U.S., and it was in Maine.

I knew that Paul had a really great greenhouse engineer. I also knew that this man was hard to get a hold of because he was very busy. I kind of pitched the early concept to Paul, and he was like "Okay, well I think that you seem to have a pretty good desire at least, even though the concept perhaps was half-baked." That's where we got a hold of Thomas Larssen.

I had initially hired my co-founder Nona just to do decent design work for me, basically some rendering. We presented our early renderings to Paul, and those are what he passed along to Thomas, and Thomas eventually came to visit us and really refined what we were looking at because we were looking at basically every kind of growing system under the sun at that point, even aeroponics, which seemed really far-fetched, and it's not far-fetched now. It's amazing how far the industry has come in eight years, it's pretty incredible actually.

I did things like take a hydroponics short course in the University of Arizona. We knew that we needed a head grower, and even though there were plenty ofpeople who have taught themselves how to be growers, everybody emphasizes the key to success is a good grower. We would hear things like "Oh, tomatoes are an art," and "Lettuce is more of a science,"and things like that.

UV: If somebody asked you where would you find a kind of elusive or talented greenhouse engineer now, where would you suggest looking ?

Penny: I do get that question often. The interesting thing is, a lot of the

sales groups (for urban farming equipment) now have developed so much now that they have expertise in their own team, like if you look at Hort Americas, they have their own test greenhouse. They can really basically engineer a greenhouse for you.

UV: You're talking about the companies that you might hire to develop your system for you?

Penny: Right. so a lot of the sales people kind of have greenhouse expertise on their side now. Does that make sense? A lot of the greatest experience comes from Europe because historically that's where so many of the greenhouses and the long history comes from.

UV: Is that because of the limited space there, or what is the reason?

Penny: Yeah. I think in the Netherlands, so much of their farmland was, they had to create their farmland and a lot of it was under water and they had limited space.

I think originally a lot of them were growing flowers and turned to food production also and so they've just been at indoor growing for longer than we have.

I was talking to somebody from Mexico and they were saying that the U.S. has not been responsible for their own food production for years. We've relied on other countries for our food production for such a long time that we haven't really cultivated this expertise.

Now quickly schools are changing, like the University of Arizona has a great

program and Colorado State are developing stronger indoor growing programs because they realize that it is the future.

I think it's just because we (the United States) went to monocrops that were all about the production of food for fuel and other things like that, and we weren't necessarily focusing on food production because it was so cheap for us to import food.

UV: What do you think are the hallmarks of (a greenhouse engineer) who's experienced? Is it just a body of experience, or is it like an expertise in the certain crop that you're trying to work with?

Penny: I do think that if somebody actually has a science background in plants, they

actually understand the science of growing plants (that is important).

I think because now there are certainly a lot of people who just learn about growing and don't learn about horticulture. I have to say that if you can find somebody who has both of those things, it's definitely very beneficial because plant pathology is so

much a part of it, you know because plants are, they're living things and so to say that you understand growing might be fine if you've actually maybe spent

years learning how to grow. I won't discredit those people at all.

It's like a chef. A chef is not made necessarily because he's gone to culinary school, but a chef is made because he maybe has some good experience just cooking.

Experience is another thing because you can't necessarily just take somebody out of school and expect them to run a whole facility, because there's a lot to it, you know? There are control systems. There's understanding temperature that may be something you would only learn on the job.

UV: Can you talk about some of the everyday challenges from an overall facility management side?

You obviously have your day-to-day challenges, like you mentioned temperature or what not, but then you also might have overarching challenges, like market dynamics

Can you talk about your insights and what you've learned since you guys have been in operation,and how you guys have improved both in the "whole forest" view, but also the"tree" view as well.

Penny: For us, since our system was so new and they've (the components) been built in a factory and they actually hadn't operated under growing conditions, there were a lot of kinks to be worked out as you can imagine.

Those were kind of the initial (set backs). Then were was learning about the building itself because I'm sure any new greenhouse has to kind of get to know and to grow into the skin of what their building is and adapt to that.

Then for us, it was even specific plants because we have a living wall, living three-story wall inside. Within this three-story system, the climate goes from very hot on the bottom very cool, I mean very hot on the top to very cool on the bottom.

There are challenges like that. It's not because we have a unique labor force that was an interesting thing to figure out too because I think any business has to figure out how to make sure their employees are where they should be according to their strengths.

Then things that we didn't really aspire to be maybe, like a delivery company even though it's something that everybody thinks is really simple, but adapting to delivering and packaging, I think that was one of the most shocking things for us, like the cost of packaging and the time and correct way to package. We had a lot to learn when we jumped into this.

UV: How would you summarize, or what would be your key points on packaging? For example, how much should people be budgeting for their packaging, common mistakes with packaging, or what are the mistakes that you made that you kind of shot yourself in the foot with?

Penny: We had to laugh because when we started, we had like five different sizes of boxes to ship our produce. It was ridiculous. I think we definitely overstocked on things and under stocked other things like, "oh this label's very pretty but we didn't think about how long it would actually take to put on the clam shell", and things like that.

I remember one day, just laughing at myself thinking "Oh my god, this lettuce is the most pampered lettuce that is going to this restaurant."

Realizing that what you're creating is, of course you fall in love with it and it seems like this living and breathing thing (the produce), but maybe it is like this microclimate that you're creating. It means so much as somebody who was with it from the start.

But what you have to remember is that it's a system. I think looking at it holistically as much as you can to make sure that you think of everything, and having to flow together is so important.

UV: I know you mentioned working with restaurants. It seems like selling whatever you're growing (as an urban farmer) to a restaurant is a very stereotypical kind of cliché kind of marketing channel as far as the main customer or the urban farming output.

Can you talk about what you think, in your experience, people don't understand about marketing and selling the stuff you produce on your urban farm, whether it's a very small amount to a guy down the street, or maybe it's retailers. What do you think are some major misconceptions that have to do with the actual commercialization like after you've grown something, after it's high quality, after it meets the spec of some customer?

Penny: I think the important thing to think about that we didn't probably understand would be so challenging, is to make sure that once it's in the store it might be on the shelf for three or four days, and understanding how to ensure that it looks good over that time period is really, really important.

It might be a little different for a restaurant because typically you can take things to a restaurant and it seems to last more because a lot of the lettuces we take are live.

I think it's just a little more challenging on the grocery store's shelf to make sure that things can stay looking fresh for a while on the shelf.

UV: Can you discuss the pros and cons of a couple of different (marketing and distribution) channels,whether it's restaurants or retail, some people might also be doing farmers'markets, etc?

Penny: I just think it depends on the size of your greenhouse or your farm. Obviously packaging, part of this is that it adds another element. But then again, it can be much more simple to sell to a restaurant partner.

I know that a lot of people think that restaurants can be fickle, but we've been so fortunate in that our restaurant partners are really very supportive.

People do need to look at the added costs of when you take your product to a grocery store, you do have to invest in packaging and your brand and all of things that I think people underestimate.

The whole distribution question is a whole other challenge too.

UV: Obviously your business has like a social responsibility element, but it's also for profit. Can you talk about that decision and maybe how you came to that decision, but also maybe the ramifications of that? I mean, would you have done it differently, or how do you think it turned out?

Penny: I think for me personally, we are starting a non-profit arm to support our educational arm because we're a production greenhouse but we're also a greenhouse that has a lot of learning going on both in that we bring people in and that we're learning ourselves about this whole new growing system.

I've always wanted it to be just a business. It's a struggle because I think the challenge is that I think it's too easy to criticize something that is a charity sometimes or it's too easy not to believe in it as a solution.

Forus, we have relied heavily on the generosity of grants and donations to get where we are, and investors that have a lot of understanding about what it takes to get started.

Maybe that's just part of being an entrepreneur too and being in an innovative company. I'm sure a lot of innovative companies go through the same sort of financial challenges and they have to have similar support in one way or the other. I guess in the end it doesn't matter. I'm not sure I'm happy that we're able to be a part of a community in a larger way,that we do have educational programs and that we are able to bring in, and most bring in people from the community, and most greenhouses can't do that because of tax pressures and things like that that it brings in.

UV: What's your favorite fruit or vegetable?

Penny: My favorite fruit or vegetable? I love apples.

UV: What's the best advice that you received when you were building Vertical Harvest Jackson or when you were learning the ins and outs of operating this type of facility, like the one you have in Vertical Harvest, or it could even be not related to anything, it could be generalized advice, like what's the best advice you think you've ever gotten?

Penny: I mean, it's so cliché but I think people just say, don't underestimate how much capital you have to have on hand for startups, and I really thought we would avoid that, but it does. It takes more money than you think to get through those early phases.

UV: Do you think that amplifies for like an urban farming company, or do you think it's the same across all company types?

Penny: Not necessarily. But I think the thing that I have learned the most, is that you really have to be honest with yourself, honest with yourself and everybody else. I think that's the easiest thing not to do.

I think a lot of startups are afraid to be honest with themselves because they put so much hard work into it and they don't want to talk about the pitfalls or to be honest about what might be kind of lurking in the shadow. That is what's going to give you a hard time.It really will. I mean, it's something we all have a hard time being, and it's just honest about what the challenge of the day is, or really is that financial really as honest as you think it should be, or are those productions really ...go back and revisit all of your numbers with as many experts as you can.

UV: Obviously Vertical Harvest had a decent amount of press coverage and you probably have gotten a good amount of exposure from that over the years. What do you think is something that a lot of people don't understand about your company or like a misconception that you would like other people to know?

Penny: I've never thought about that. I feel like ... Imean, I don't know if it's a misconception, but I do think, and maybe people don't realize that the time that was put into starting this greenhouse.

It was a monumental effort. Something like this is not for the weak at heart at all.It's scary, and it's hard work and things don't turn out the way you want them to. There's a lot that goes around. It's very life-changing. I don't think it's all like a bed of roses and that. Of course we're smiling on the pictures, but let me tell you. It's not easy.

Thanks Penny!

Go Ahead and AVA Byte of Fresh Produce From This Countertop Garden

Go Ahead And AVA Byte of Fresh Produce From This Countertop Garden

Derek Markham (@derekmarkham)

Technology / Gadgets

June 14, 2017

This soil-free smart garden promises fresh greens and veggies that are grown as local as it gets.

When it comes to naming new indoor growing products, the puns and wordplay may be bad, but getting more people growing their own food is definitely not, so please forgive the title of this article and lettuce move on to the actual product itself.

If you'd like to grow some of your own produce, but you don't have a place outdoors for a garden, or you'd like to grow year-round, a countertop indoor garden can be the answer, especially in a small space. A low-tech solution, such as a plant pot or an Urban Leaf in a sunny window, can be effective until the short days of winter arrive, after which supplemental lighting is needed until spring arrives. That's one of the reasons that growing devices with integrated lighting and watering systems are a popular choice, because they can be set up virtually anywhere in the home, without regard to access to sunlight. With LED lighting that is automated and tuned for optimal plant growth, combined with a hydroponic or aeroponic growing system, even those who've never had a green thumb can successfully grow greens, herbs, and veggies indoors.

In today's edition of YAUGU (yet another urban grow unit), the AVA Byte promises to bring adaptive intelligence and machine learning to the countertop growing scene for a hassle-free experience that is "So Smart & Simple it Must be Magic."

This 5-pot growing unit is designed to accept the company's soil-free compostable grow pods, which are pre-seeded and contain a nutrient mix appropriate to the plant variety, and which are then watered automatically according to the growth of the plants. The lighting, which is supplied by LED bulbs (no other specs given), is monitored and controlled automatically by the device, and is said to be "plant-optimized." According to the company, the lighting and growing system offers up to triple the growth rates of conventional growing, and requires much less water (something which is a feature of hydroponics systems in general).

"Growing your own food is a vote against the way the food system is today. Being food-lovers, we wanted to start a food revolution. Unfortunately, unlike houses with large backyards, a condo-dweller like myself is restricted by lack of space and access to sunlight. My kitchen herbs kept dying because Vancouver gets really dark and dry at certain times of the year." - Valerie Song, co-founder and CEO of AVA Technologies

The unit measures 18" x 4.75" x 7.5" (45.75 x 12 x 19cm) and weighs 4 pounds (1.8 kg) empty, and the lighting bar telescopes up to 21" high to adjust for plant growth. According to the company, the device is "intelligent, connected, and self-improving" and can connect with Alexa, Google Home or Apple Homekit.

Plug it in, place your pods, connect to Wi-Fi using the app, and fill the water reservoir. AVA notifies you when it's time to refill the reservoir and when your plants are ready to harvest! - AVA Byte

One unique feature of the AVA Byte is the inclusion of an HD camera pointed at the plants, which allows it to track plant health and growth, as well as letting users make time-lapse videos of their herbs and veggies. I'm not totally sure there's a huge need for more time-lapse indoor gardening videos, but it could be fun, right? There's also a mention of using the camera for something called Plant Vision, which I imagined to be something that could diagnose plant issues via an image, but nothing more is said about it, so perhaps it's a future feature. And of course, there's an app for the device, which allows users to monitor the light, water, and growth of the unit, as well as to manually customize the device's growing settings if desired.

Another intriguing element, also only mentioned briefly, was that the units could not only grow herbs, greens, and veggies, but could also be used to grow mushrooms. There's no other information about how the AVA Byte system would work for growing mushrooms, but perhaps that's another feature coming in the future, which could be a way for it to stand out among other similar countertop growing systems.

The company is currently running a crowdfunding campaign for the AVA Byte, which has already surpassed its initial goal, and backers at the $189 level will receive a unit and 5 growing pods (said to be $320 MSRP) in March of 2018. Find out more at the website.

Future Of Food: How Under 30 Edenworks Is Transforming Urban Agriculture

JUN 1, 2017 @ 03:45 PM

Future Of Food: How Under 30 Edenworks Is Transforming Urban Agriculture

Tim Pierson

Jason Green, 27, and Matt LaRosa, 23, are the CEO and Construction Manager of Edenworks.

When Matt LaRosa joined Edenworks in early 2013, he was a college freshman who still hadn't even picked a major. But when he overheard CEO Jason Green at a pitch competition explain his plan to transform industrial buildings into high-tech farms, he immediately abandoned his own pitch and pitched himself to Green instead. The duo, along with cofounder Ben Silverman, went on to create the self-regulating aquaponic system that now supplies microgreens and fish to Brooklyn and landed them on this year's 30 Under 30 Social Entrepreneurs list.

The Edenworks HQ is not exactly where one would expect to find fresh produce and fish. Located in the Bushwick area of Brooklyn, the company sits atop a metalworking shop belonging to a relative of Green. Their office looks like a typical young startup: all eleven employees crowded in one room with computer screens occupying almost every surface. But upstairs across a narrow walkway is where the magic really happens: an 800 square foot greenhouse, custom built by LaRosa, housing fish tanks, vertically stacked panels of microgreens, and a sanitary packaging unit. Though admittedly cramped, the company says their size has made the team significantly more lithe than larger industrial agriculture operations.

"Being a startup, you have a ton of room to break things and iterate very quickly," LaRosa told Forbes. "We're so nimble with changing our prototypes... we have something different than anywhere else in the entire world."

Currently, about 95% of leafy greens consumed in the US are grown in the desert regions of California and Arizona. Most of these products are grown for mass production and durability in transport, rarely for quality or sustainability. Urban farms have cropped up as way to provide growing metropolises with fresher produce in a way that is better for the environment.

The Edenworks model differentiates itself from other urban farms in that it is a complete, aquaponic ecosystem. Waste from the tilapia fish is used as a natural and potent fertilizer for the microgreens planted on vertically stacked power racks. They have no need for synthetic fertilizers or pesticides that can diminish the nutritional quality of produce.

"The water table is falling every year, there's a huge amount of money invested in pumping water out of the ground and irrigating, and inefficiency in the supply chain where a lot of product gets wasted or left in the field," explained Green, a former bio-engineer and Howard Hughes research fellow. "We eliminate all of that waste."

A common phrase in the office is turning factories into farms instead of farms into factories, and many of their design challenges have been combated by embracing the industrial nature of the location. Indoor farms are often criticized because they can't make use of the natural processes used in traditional farming. But the team has invested in studying ancillary industries to find the lowest cost and highest return methods of mimicking the natural processes, like using custom LED lighting to emulate sunlight.

The research has paid off. In the current iteration, Edenworks is able to harvest, package and reach consumers within 24 hours. By cutting down on transport and prioritizing quality over durability, the greens are also up to 40% more nutrient dense than traditional produce.

For now, their largest barrier is clear: space. With $2.5 million in funding to date, their tiny greenhouse has managed to consistently service the local Whole Foods with two varietals of microgreens. In the winter of 2018 though, they plan to move to a space 40 times the size and simultaneously roll out five additional product lines across the NYC area.

The plans for the new building have been delayed a few times, but with LaRosa graduating NYU last month and joining the team full time, Green is confident they are on track to hit their deadline. The larger facility will be the result of years of planning that will incorporate new technology that will allow them to become even more efficient and competitive in the market.

"What we've developed is a huge amount of automation that will allow us to bring the cost down for local indoor grown product into price parity with California grown product, and that's really disruptive," says Green. "If we want to move the needle on where food comes from in the mass market, it has to be cost competitive. We want to be the cost leader, we want to bring the cost down."

Innovative Thinking and Technology: The Key to Solving Global Problems

Innovative Thinking and Technology: The Key to Solving Global Problems

Austin Belisle - June 1, 2017

This blog was guest-written by Brandi DeCarli, Founding Partner of Farm from a Box. She’ll be guest-speaking during the “Global Problem Solvers Who are Guardians of Our Planet” session of the Women Rock-IT series on June 15th.

Every aspect of our modern-day lives has been impacted by technology. From cloud and robotics to digital currency and drones, our lives are inextricably tied to the technology that surrounds us. While farming may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of technology, it has played a key role in changing the face of agriculture and our global food system.

In the past 50 years, the Green Revolution has pushed to increase crop yields through large-scale intensification of single crops. Advances in mechanized farming allowed for larger and larger acreage to be farmed. By focusing on the large-scale intensification of a single crop, the natural checks and balances that diverse ecosystems provide were no longer in place.

To maintain production, it required heavy use of fertilizers and pesticides, which has directly impacted soil fertility and ecosystems around the globe. Now, with 40% of our agricultural soil degraded and 70% of our freshwater resources being gulped up by agriculture, it is clear that our current approach is not sustainable.

While advances in technology have enabled global agricultural production to increase with our growing population, those gains came at an unprecedented environmental cost. As we work to feed a growing global population, the environmental pressures will continue to increase.

By 2050, the world’s population is expected to grow by more than two billion people. Half will be born in Sub-Saharan Africa, and another 30 percent in South and Southeast Asia. Those regions are also where the effects of climate change are expected to hit hardest.

So, how can make sure that the growing need for food worldwide is met in an ecologically sustainable way? And what role can technology play? The opportunity may be in shifting our focus from mass production to production by the masses.

An estimated 70% of the world’s food comes from small, rural farms that are no bigger, on average, than two acres. And despite the increase in large-scale industrialized farms, small, rural farms are still the backbone of our global food supply. But these rural areas are often the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

The challenges of drought, degraded soil, and inefficient and labor-intensive methods contribute to and exacerbate low and unreliable crop production. Without access to the infrastructure or technologies that can support a productive farm, farmers will either struggle with low yields, depend on chemical inputs that further deplete the soil, or rely on outside aid.

This is where Farm from a Box comes in.

Farm from a Box works to bridge the “access” gap by providing a complete, off-grid toolkit for sustainable, tech-powered agriculture. Built from a modified shipping container, each unit contains a complete ecosystem of smart farm technologies to enhance agricultural productivity; from renewable power and micro-drip irrigation to Information and Communications Technology equipment.

Designed as the “Swiss-Army knife” of farming, this mobile infrastructure provides all the tools needed to support a two-acre farm. By empowering farmers to grow and sustain food production at the community level, we build greater resilience to climate shocks, boost livelihoods, and help bridge the access gap by making healthy food locally available.

With its own off-grid power, Farm from a Box can act as its own micro-grid in remote locations; drip irrigation helps save water and stabilize crops through drought conditions while also extending the growing season; internal cold-storage helps keep crops fresher longer, reducing post-harvest loss by 80%; Wi-Fi connectivity improves information access and exchange; and a cloud-based IoT system helps monitor production and efficiencies.

By introducing micro-irrigation, we can extend the growing season and better support a wide variety of crops throughout the year, while lowering the amount the water used by applying it directly to the plant. The off-grid power array and storage provide a reliable energy source to power the pump, move the water through the irrigation lines, cool the internal cold storage area, and support the charging of auxiliary needs.

We have also connected each unit with Wi-Fi capabilities and a complete IoT system to improve operational efficiency, optimize water and energy use, and provide guidance on farm management and market information. Because we have integrated sensors on all of the primary systems, we can monitor and control the performance of the system, and also set alerts for when a component dips below or exceeds certain levels.

Let me give you an example of how this applies in a real-world situation. We recently teamed up with the United Nations World Food Programme Tanzania and WFP’s Innovation Accelerator to support food and nutrition security for refugee and host communities. Our Farm from a Box system will be used to increase the availability of nutritious crops, provide low-cost agricultural commodities and, through increased production, boost the income levels for both refugees and the surrounding host communities.

Because the farm is operating in a remote location in eastern Tanzania, information becomes a vital component to ensuring the system is working as it should be, and the farmers have the data they need to know what is happening and why. Through our cloud-based IoT system, both the community and the WFP has open access to see how much energy the solar panels are producing, how much water is being used, and if the overall system is functioning properly.

Now, technology for the sake of technology isn’t a standalone solution; how it is utilized in overall value creation is where we find the real impact. By marrying technology with small-scale regenerative farming practices, we can improve soil quality, reduce dependence on outside inputs, conserve water, and build up nutrients.

Techniques like composting, crop rotation and diversification, cover cropping, and no-till practices nurture the soil’s fertility and help produce a healthier crop. By shifting our focus from industrialized agriculture to local organic agriculture, we can potentially convert carbon from a greenhouse gas into a food-producing asset.

Farm from a Box is just one of many innovations that are working to empower smallholder farmers with sustainable solutions; there are vertical farm systems, small farm robots that automate field work, drones that use near-infrared and thermal sensors to “see” how plants are doing. Technological innovations like these can help us achieve better health, well-being, and equity throughout our planetary system as a whole.

But we need creative solutions, and sometimes that requires thinking outside of the box. I don’t come from a technological background, nor does my business partner, but we saw a problem and thought, “There must be a better way.” We all have the power to change our world for the better. Food is something that connects us all and has a direct impact on our everyday lives and environment.

When we first set out to start Farm from a Box, our intention was to create a mobile infrastructure that could provide people with the tools they need to grow their own nutritious food. Over time, that idea has grown; we now see Farm from a Box as a tool that could transform local production and nutritional security globally.

Whether it is a local school, community group, or remote village in an underdeveloped country, smallholder farmers are the ecological gatekeepers to building a more sustainable and equitable food supply. Technology has the potential to help solve the intractable problems facing humanity and will continue to play an increasingly vital role in global food security and planetary health. But it will require innovative thinking from all of us to achieve it.

Freight Farms Lands $7.3M As Agriculture Meets Data & Automation

June 6th, 2017

Investors have planted $7.3 million in Freight Farms to help the Boston-based startup bring its micro-farms to more places around the globe—and potentially even beyond.

The investors in the Series B round include return backer Spark Capital, also based in Boston. The news was first reported by the Wall Street Journal on Monday. Freight Farms’ total venture capital haul now exceeds $12 million, according to SEC filings.

The company sells shipping containers filled with hydroponic farming systems that can grow a variety of lettuces, herbs, and other greens. The system is designed to operate with minimal hands-on work by humans. It employs LED lights and automated watering and fertilizing technology. Operators can monitor the farm through a live camera feed, and they can use an app to control the climate within the shipping container and shop for growing supplies. The company has said the system uses less water than traditional farming methods, and because it’s housed inside a shipping container, it doesn’t require pesticides or herbicides.

Freight Farms has deployed more than 100 of these farming systems across the U.S. and in several countries. Customers include urban farmers, traditional farms, produce distributors, and universities.

The startup was formed in 2010 by Brad McNamara and Jon Friedman, who previously worked on rooftop hydroponic gardens.

Freight Farms is trying to take advantage of the growing interest in local food sourcing, as its shipping containers can be set up close to where food gets sold or consumed. It also aims to enable year-round food production in challenging locales—think the snowy mountains of Colorado, or even space. Freight Farms and Clemson University are working on a NASA-funded project exploring ways to grow food in harsh climates and, potentially, deep space.

Freight Farms also fits with trends in agriculture around automation and using digital tools. That’s a key reason why Spark made another investment.

“Modular, Internet-connected, and highly automated commercial farms will play an important role in bringing local and affordable produce to communities all over the world,” Spark’s Todd Dagres and John Melas-Kyriazi wrote in a blog post about the new investment. “Value will accrue to those who own the technology layer of this farming stack (hardware + software) as data and automation become increasingly important drivers of low-cost production.”

Agricultural technology companies are taking various approaches to indoor farming. Like Freight Farms, Atlanta-based PodPonics sells tech-enabled mini-farms inside shipping containers. Businesses such as New York-based BrightFarms and Harrisonburg, VA-based Shenandoah Growers produce food inside greenhouses. And startups like Grove and SproutsIO, two Boston-area firms, sell micro-farming systems to consumers for growing food inside their homes.

Houses Squeezing Out Farms

Mike Chapman.

If too many houses replace vegetable growing operations, we may have to look at alternatives such as vertical farming, says Horticulture NZ chief executive Mike Chapman.

He has always been sceptical about such methods for NZ, but we may be “stuck with it” if urbanisation keeps taking productive land, he warns.

Vertical farming was among the most interesting sessions at the Produce Marketing Association (PMA) ANZ conference in Adelaide, he says.

A New York urban agriculture consultant, Henry Gordon-Smith, spoke about why vertical farming has taken off in the US; “one simple reason is fresh,” says Chapman.

In the US, leafy greens may often need transporting long distances to large cities. “So you can get reasonably priced old buildings where you can set up vertical farming close to large cities.

“In the States that is becoming quite economical as opposed to shipping in leafy greens for days in trucks. The degree of freshness with vertical farming is very acceptable to consumers.

“The cost of rentals for your warehouses can be quite prohibitive to a successful programme, and the cost of LED lighting and efficiency. But if you get the right building, LED efficiency is also increasing.”

But you can’t vertical farm, say, onions and potatoes.

“You are talking about leafy greens, but even in the States where there are lots of vertical farms, there will always be a place for soil-grown vegetables. It just gives you a bit of diversification, especially where the vegetables aren’t grown close to the cities.”

He knows of nobody vertical farming in New Zealand.

“NZ may not have the need because of the proximity of our growing operations to the cities, but as houses [replace] growing vegetables this may become one of the options.

“I have always been a little sceptical about it because we should be able to grow in our soil, but as we move forward we may find we’re stuck with it.”

Meanwhile, robots will replace some jobs but innovative people will always be needed in the workforce, says Chapman on another message from the conference.

“But the innovation is different from that required 10 years ago and even today. The skills for the future are creativity, problem solving, advanced reasoning, complex judgments, social interaction and emotional intelligence.

“In the workforces that are developing, a whole different set of skills is required which we should be training for and working on for the future.

“Robots will take away quite a few functions in future and the skills you must look to are skills that robots can’t do. Robots don’t have emotional intelligence, etc.”

Chapman says there was also much discussion about R&D in Australia, which is complicated. Much was said about research being dislocated from growers because of the complexity of the system. And too much research money is being spent on bureaucracy rather than the actual work.

“So you are not getting growers and researchers having the strong interaction we have in NZ to a far, far greater degree.

“In NZ we haven’t got federal versus state. We might think our system is complicated but the Australian system makes ours look rudimentary and straightforward.”

An Urban Farm Grows In Brooklyn

Tue Jun 6, 2017 | 8:12am EDT

An Urban Farm Grows In Brooklyn

By Melissa Fares | NEW YORK

Erik Groszyk, 30, used to spend his day as an investment banker working on spreadsheets. Now, he blasts rapper Kendrick Lamar while harvesting crops from his own urban farm out of a shipping container in a Brooklyn parking lot.

The Harvard graduate is one of 10 "entrepreneurial farmers" selected by Square Roots, an indoor urban farming company, to grow kale, mini-head lettuce and other crops locally in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn.

For 12 months, farmers each get a 320-square-foot steel shipping container where they control the climate of their own farm. Under pink LED lights, they grow GMO-free greens all year round.

Groszyk, who personally makes all the deliveries to his 45 customers, said he chooses certain crops based on customer feedback and grows new crops based on special requests.

"Literally the first day we were here, they were lowering these shipping containers with a crane off the back of a truck," said Groszyk. "By the next week, we were already planting seeds."

Tobias Peggs launched Square Roots with Kimbal Musk, the brother of Tesla Inc (TSLA.O) Chief Executive Elon Musk, in November, producing roughly 500 pounds of greens every week for hundreds of customers.

"If we can come up with a solution that works for New York, then as the rest of the world increasingly looks like New York, we'll be ready to scale everywhere," said Peggs.

In exchange for providing the farms and the year-long program, which includes support on topics like business development, branding, sales and finance, Square Roots shares 30 percent of the revenue with the farmers. Peggs estimates that farmers take home between $30,000 and $40,000 total by the end of the year.

The farmers cover the operating expenses of their container farm, such as water, electricity and seeds and pay rent, costing them roughly $1,500 per month in total, according to Peggs.

"An alternative path would be doing an MBA in food management, probably costing them tens of thousands if not hundreds of thousands of dollars," Peggs said, adding that he hopes farmers start companies of their own after they graduate from the program.

Groszyk harvests 15 to 20 pounds of produce each week, having been trained in artificial lighting, water chemistry, nutrient balance, business development and sales.

"It's really interesting to find out who's growing your food," said Tieg Zaharia, 25, a software engineer at Kickstarter, while munching on a $5 bag of greens grown and packaged by Groszyk.

"You're not just buying something that's shipped in from hundreds of miles away."

Nabeela Lakhani, 23, said reading "Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal" in high school inspired her to change the food system.

Three nights per week, Lakhani assumes the role of resident chef at a market-to-table restaurant in lower Manhattan.

"I walk up to the table and say, 'Hi guys! Sorry to interrupt, but I wanted to introduce myself. I am Chalk Point Kitchen's new urban farmer,' and they're like, 'What?'" said Lakhani, who specializes in Tuscan kale and rainbow chard.

"Then I kind of just go, 'Yeah, you know, we have a shipping container in Brooklyn ... I harvest this stuff and bring it here within 24 hours of you eating it, so it's the freshest salad in New York City.'"

(Reporting by Melissa Fares in New York; Additional reporting by Mike Segar in New York; Editing by Dan Grebler)

The Greening Of Alaska: Vertical Hydroponic Farming & Alaska Natural Organics Affect The Economy

The Greening Of Alaska: Vertical Hydroponic Farming & Alaska Natural Organics Affect The Economy

Lester Mondrag | June 05, 2017 | 02:38 PM EDT

(Photo : Photo by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images) Spanish Intern Isabel checks Corriander plants in one of the Underground tunnels at 'Growing Underground' in London, England. The former air raid shelters covering 65,000 square feet lie 120 feet under Clapham High street and are home to 'Growing Underground', the UKs first underground farm. The farms produce includes pea shoots, rocket, wasabi mustard, red basil and red amaranth, pink stem radish, garlic chives, fennel and coriander, and supply to restaurants across London including Michelin-starred chef Michel Roux Jr's 'Le Gavroche'.

Alaska is now an agricultural supplier of fresh fruits and garden vegetables that usually grows in the warm areas of California and Mexico. The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Natural Resource Conservation Services supports and funds the farming technique. The 49th state enjoys the funding and is now accelerating its farming industry with additional greenhouses for construction, the greening of Alaska is at hand.

The greening of Alaska has its people feel the excitement of the sustainable farming industry with support from the government; the last seven years saw some 700 greenhouses put up to support the growing demand of agricultural products for domestic consumption and export to other states. Agricultural produce would include fresh tomatoes, eggplants, peppers, tomatillos, Asian greens, kales, and almost anything under the sun, except January when the sun limits its shine. The sun is farthest during the first month of the year and only rises for five hours in the southern front of Alaska.

From February to December, the greening of Alaska continues the application of Hydroponic Farming. The whole eleven months, a huge tunnel becomes a greenery of edible produce for Alaska's economy. The insides of the greenhouse become what scientists call the "hardiness zone" which the USDA classifies as the best environment for growing fruits and vegetables.

The region of ice and snow is now Alaska Greening as local farmers can now grow from corn to melons at will, as the green tunnels are reliably warm. January even extends its farming month when the sun only rises for 5 hours in the southern coast of the state. The far North never experience sunrise and setting of the sun, reports Scientific American.

The two startup companies, Vertical Hydroponic Farming and Alaska Natural Organics impacts the economy and the greening of Alaska. The two companies apply hydroponics farming with only natural nutrient rich mineral water which is a soil and pesticide free technique. The vegetation bask under red and blue LED lights mimicking sunlight, reports Eco Watch.

The growth of indoor farming is booming as its economics is feasible to make the industry flourish, says Head of the US Department of Agriculture's Farm Service Agency, Danny Consenstein. Alaska will have sustainable farming and would be able to export its produce to neighboring provinces of Canada and other states in America.

5 Things To Know About Urban Organics Aquaponics Farm

5 Things To Know About Urban Organics Aquaponics Farm

Monday, June 5, 2017 by Mecca Bos in Food & Drink

Urban Organics aquaponics farm now has two locations in St. Paul

Many years ago, I stood with Dave Haider in a nearly empty grain silo at the old Hamm’s Brewery staring at a blue pool.

He had big dreams. One day, wife Kristen called him into the room, where she was watching TV.

“Look,” she said, and pointed. On the screen was an aquaponics farm, a closed-loop system for farming fish and produce. The fish enrich the water, the water is filtered through the root systems of the plants, and both are eventually edible for humans.

“You should do that.”

“OK,” said Haider.

And thus began their journey, along with partners Fred Haberman and Chris Ames, to implement Urban Organics aquaponics farm. The Hamm’s Brewery was their first location, and a second is now up and running in the Historic Schmidt Brewery. They’ve come a long way since a single pool in a silo.

Five things to know about the Twin Cities largest aquaponics farm:

1. Urban Organics greens are now available for purchase, including green and red kale, arugula, bok choy, green and red romaine, swiss chard, and green and red leaf lettuces. Get them at Hy Vee supermarkets in Eagan and Savage and at Seward, Wedge, and Lakewinds co-ops.

Want to taste the fish? Get it at Birchwood Cafe. The Fish Guys (local fish wholesaler led in part by Tim McKee) will be distributing Urban Organics fish, so watch for it at stores and restaurants in the coming months (more info on the fish below).

2. The farm was recently featured in The Guardian as a Top 10 innovative “next-gen” urban farm. Urban Organics was noted for using only 2 percent of the water used in conventional agriculture, and for its mission to prove the viability of aquaponics systems overall.

Other eco-friendly perks of the Urban Organics aquaponics system: they do not rely on herbicides, pesticides, or chemical fertilizers, and raising fish indoors takes pressure off oceans and wild-caught species.

More food raised in urban centers means less food traveling in from far-flung places. Urban Organics calls its product “hyper-local.”

3. The numbers: The 87,000 square foot Schmidt farm aims to provide 275,000 pounds of fresh fish and 475,000 pounds of organically grown produce per year.

Currently, the farm is at 30 percent capacity for produce, and they project being at full capacity by fall. Getting their Arctic Char and Atlantic Salmon to a harvestable size of eight to 10 pounds will take another 11 to 20 months.

4. If you happen to find yourself at a HealthPartners hospital, you might wind up eating Urban Organics food from your patient meal tray, cafeteria salad bar, or grab-and-go retail kiosk.

5. Part of the Urban Organics mission statement is to grow fresh food in urban “food deserts,” which would not otherwise have access to locally produced food. And with an indoor system, they can do it year-round, even in the dead of a St. Paul winter.

For more information on Urban Organics: urbanorganics.com

(Toggle around in their website. It’s kinda fun.)

700 Minnehaha Ave. E., St. Paul

543 James Ave. W.

Biosphere's Vertical Gardens Will Provide Produce For Public

Biosphere's Vertical Gardens Will Provide Produce For Public

- By Tom Beal Arizona Daily Star

- Apr 18, 2017

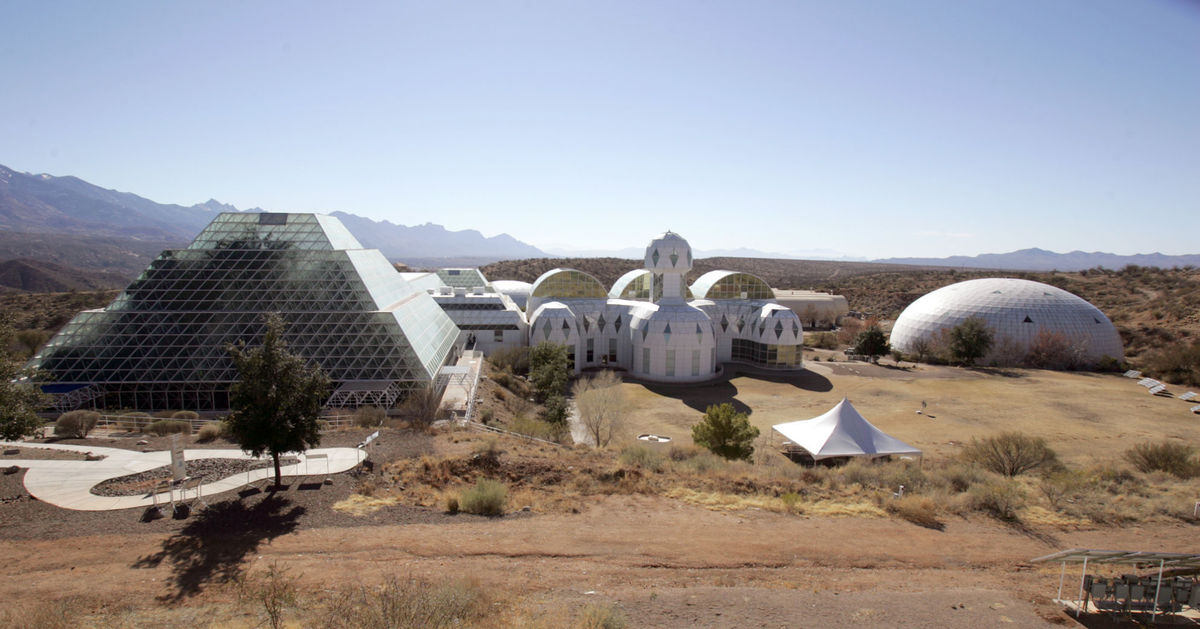

Food crops are coming back to Biosphere 2, but they won’t be planted in the 3 acres under glass at the University of Arizona research facility in Oracle.

A company named Civic Farms plans to grow its leafy greens under artificial lights in one of the cavernous “lungs” that kept the Biosphere’s glass from imploding or exploding when it was all sealed up.

The lungs, which equalized the air pressure in the dome, are no longer needed now that the Biosphere is no longer sealed. The west lung will be transformed into a “vertical farm” that will train LED lights on stacked racks of floating plants whose roots draw water and nutrients from circulating, fortified water.

A variety of leafy greens and herbs such as kale, arugula, lettuce and basil will be packaged and sold to customers in Tucson and Phoenix, said Paul Hardej, CEO and co-founder of Civic Farms.

He also expects to grow high-value crops, such as microgreens, Hardej said.

Hardej said the company plans to complete construction and begin growing by the end of the year.

Civic Farms’ contact with the UA allows for half the 20,000-square-foot space to be devoted to production, with areas given over to research and scientific education.

The UA will lease the space to Civic Farms for a nominal fee of $15,000 a year. In return, the company will invest more than $1 million in the facility and dedicate $250,000 over five years to hire student researchers in conjunction with the UA’s Controlled Environment Agriculture Center.

Details of branding haven’t been worked out, said UA Science Dean Joaquin Ruiz, but don’t be surprised to find Biosphere Basil turning up in your salad soon.

Hardej said the “brands” established by the UA were lures for his company.

“The UA itself has a brand recognition throughout the agricultural industry and specifically the Controlled Environment Agriculture Center. They have a lot of respect worldwide.”

“Also, the Biosphere itself is a great story,” he said.

“The original intent was to develop a self-sustaining, controlled environment where people could live, regardless of outside conditions.

“In a way, this is a fulfillment of the original purpose,” he said.

Hardej said he recognizes the irony of growing food in artificial light at the giant greenhouse. He is convinced, however, that growing plants with artificial lighting can become as economical as growing them in sunlight.

“Decades ago, greenhouses were very innovative. It felt like it allowed the farmer to control the environment. It did not control the light and also the temperature differentials.”

Hardej said indoor growing allows you to control all the variables — the water, the CO2 levels, the nutrients and the light. “Farming is much more productive and much more predictable than in a greenhouse,” he said.

You can’t stack plants on soil, or even in a greenhouse, he said. “A vertical farm can be 20 to 100 times more productive. The overall direction globally is indoors,” he said.

Indoor agriculture is still a sliver of overall crop production, said Gene Giacomelli, director of the UA’s Controlled Environment Agriculture Center (CEAC) and most indoor operations are greenhouses.

“Vertical farms” account for a small portion of that sliver, but are a fast-growing segment for growing high-value crops with a level of control over the environment that can’t be attained elsewhere, he said.

“Theoretically, we should be able to control everything,” he said.

Murat Kacira, a UA professor of agricultural-biosystems engineering, is already working on systems to do that in a lab at the CEAC center on North Campbell Avenue, where he grows leafy greens and herbs under banks of LED lights. He can control the wavelengths of light, temperature, humidity, the mix of oxygen and carbon dioxide and the nutrients available to the plants.

Those variables can be tuned to improve the yield, quality and nutritional value of the plants being grown. He is developing sensor systems that allow the plants to signal their needs.

A lot of questions remain, said Giacomelli. Different plants require different inputs. Young plants have different needs than mature ones.

Air handling is a tricky problem, he said. Air flow differs between the bottom and top racks and at different locations of a given rack of plants.

It will take “more than a couple years” to figure it all out, said Giacomelli.

Kacira said the Civic Farms installation “is a really complementary facility to the research going on under glass.”

He expects the Biosphere to become a “test bed” for more research on the nexus of food, water and energy.

Ruiz said that “nexus” is the direction for research at the Biosphere for the coming decade.

'Plant Factories' Churn Out Clean Food in China’s Dirty Cities

'Plant Factories' Churn Out Clean Food in China’s Dirty Cities

Researchers build urban farms, crop labs to combat contamination

Bloomberg News | May 25, 2017, 4:00 PM CDT

Yang Qichang walks through his “plant factory” atop the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Beijing, inspecting trays of tomato vines that may help farmers slip the stranglehold that toxins have on China’s food supply.

The containers are stacked like bunk beds, with each vine wrapped in red and blue LED lights that evoke tiny Christmas trees. Yang is testing which parts of the visible-light spectrum are optimal for photosynthesis and plant growth while using minimal energy.

He’s having some success. With rows 10 feet high, Yang’s indoor patches of tomatoes, lettuce, celery and bok choy yield between 40 and 100 times more produce than a typical open field of the same size. There’s another advantage for using the self-contained, vertical system: outside, choking air pollution measures about five times the level the World Health Organization considers safe.

Rows of tomato seedlings are monitored in an experimental greenhouse at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

“Using vertical agriculture, we don’t need to use pesticides and we can use less chemical fertilizers—and produce safe food,” said Yang, director of the Institute of Environment and Sustainable Development in Agriculture.

Yang’s government-funded research on vertical farming reflects the changing mindset of China’s leaders, who for decades preoccupied themselves with raising incomes for 1 billion-plus people. Runaway growth created the world’s second-biggest economy, yet the catalyzing coal mines and smokestacks filled the environment with poisons and ate up valuable farmland.

That stew inhibits the nation’s ability to feed itself, and is one reason why China increasingly relies on international markets to secure enough food. For example, it imported about $31.2 billion of soybeans in 2015, an increase of 43 percent since 2008, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. About a third of that came from the U.S.

Given the fluctuating state of trade relations with U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration and the increasing global competition for resources, China is turning to technology to make its land productive again.

“We will undertake rigorous investigations on soil pollution, and develop and implement category-based measures to tackle this problem,” Premier Li Keqiang told the National People’s Congress in March.

The silver bullet would be to eliminate emissions and industrial waste, an unrealistic option for a developing $11 trillion economy. Yet inventors and investors believe there are enough promising technologies to help China circumvent—and restore—lost agricultural productivity.

Government money backs a variety of efforts to modernize farming and improve growers’ livelihoods. The state-run Agricultural Development Bank of China pledges 3 trillion yuan ($437 billion) in loans through 2020 to finance key projects promoted by the Ministry of Agriculture.

By comparison, the value of U.S. agricultural production last year is forecast to be $405.2 billion.

Favorable terms will be offered to projects trying to improve efficiency, increase the harvest, modernize farming operations and develop the seed industry to ensure grain supplies, the bank said.

The loan program also intends to stimulate overseas investment in agriculture by Chinese companies. The biggest example would be state-owned China National Chemical Corp.’s planned acquisition of Switzerland’s Syngenta AG for $43 billion. That will give ChemChina access to the intellectual property, including seed technology, of one of the largest agri-businesses.

Yet China is reluctant to unleash genetically modified foods into its grocery stores. The government doesn’t allow planting of most GMO crops, including pest-resistant rice and herbicide-resistant soybeans, especially as an October survey in the northern breadbasket of Heilongjiang province showed that 90 percent of respondents oppose GMOs. China will carry out a nationwide poll on the technology next month.

“China’s past food-safety problems have caused the public to distrust the government when it comes to new food technologies,” said Sam Geall, an associate fellow at Chatham House in London.

A researcher transplants rice seedlings in a greenhouse of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

About a fifth of China's arable land contains levels of toxins exceeding national standards, the government said in 2014. That's more than half the size of California.

About 14 percent of domestic grain is laced with such heavy metals as cadmium, arsenic and lead, scientists at government-affiliated universities wrote in 2015. The danger is most evident in industrial coastal provinces, where many of the world’s iPhones and Nikes are manufactured.

The government of Guangdong province, adjacent to Hong Kong, said in 2013 that 44 percent of the rice sampled locally was laced with excessive cadmium, which can damage organs and weaken bones if consumed regularly in high quantities.

That’s where Yang’s “plant factories” would come in. For now, the greenhouse-like structures are mostly demonstrations as he tries to improve their energy efficiency and make their produce more affordable to consumers—and a better investment for the government. Yang’s work is supported by an $8 million government grant.

“With the challenges our agriculture is facing, including China’s rapid urbanization and the increasing need for safe food, plant factories and vertical agriculture will undergo a big development in China,” he said. “There will be many ways to farm in big cities.”

He isn’t alone in hunting for techniques to grow untainted food in the concrete jungle. A Beijing startup called Alesca Life Technologies is using retrofitted shipping containers to farm leafy greens.

Roots of a kelp plant grow through a sponge under artificial light at an Alesca Life shipping-container farm in Beijing. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

A demonstration model is parked atop metal stilts in an alley between a Japanese restaurant and a block of office buildings in Beijing.

Inside, co-founder Stuart Oda, a former investment banker for Bank of America Merrill Lynch in the U.S. and Japan, checks on rows of planters sprouting peas, mustard, kale and arugula under LED bulbs. Alesca Life’s smartphone app allows growers to monitor air and water conditions remotely.

“Agriculture has not really innovated materially in the past 10,000 years,” Oda said. “The future of farming—to us—is urban.”

The containers can sell for $45,000 to $65,000 each, depending on the specifications, Oda said. Alesca Life sold portable, cabinet-sized units to a division of the Swire Group, which manages luxury hotels in Beijing, and the royal family of Dubai. The startup hasn’t publicly disclosed its fundraising.

Shunwei Capital Partners, a Beijing-based fund backed by Xiaomi Corp. founder Lei Jun, has invested in 15 rural and agriculture-related startups in China, including one that makes sensors for tracking soil and air quality.

Shunwei manages more than $1.75 billion and 2 billion yuan across five funds.

“For agriculture technology to be adopted on a wider scale, it needs to be efficient and cost-effective,” said Tuck Lye Koh, the founding partner.

That’s one reason why Shunwei is backing agricultural drones, which more precisely spray fertilizers and the chemicals that ward off crop-destroying pests and diseases.

Clockwise from top: Trays of wheat grass grow in one of Alesca Life's converted containers; Kelp seedlings are cultivated in a foam mat at the urban farm; An employee carefully places each seed.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

As China’s farmland dwindled because of urbanization, the remaining growers attempted to boost yields by soaking fields with fertilizers and pesticides, degrading the soil and contaminating the crops.

Farmers in China use four-and-a-half times more fertilizer per hectare (2.4 acres) of arable land than farmers in North America, according to the World Bank.

“There’s overuse of fertilizers in every country, but especially China,” said Jeremy Rifkin, whose books include “The Third Industrial Revolution.” “The crops can’t even absorb the amount of fertilizers that are being dumped.”

As dawn squints over cornfields on Hainan island, a pastel-blue truck rumbles down the gravel road and stops. Workers emerge with a pair of drones made by Shenzhen-based DJI and a cluster of batteries.

Zhang Yourong, the farmer managing 270 mu (44 acres), arrives in a pickup loaded with pesticide bottles. The crew adds water and pours the milky concoction into 10-liter plastic canisters suspended under the drones.

The stalks part like the wake of a boat as the drones fly over. Every 10 minutes, the eight-armed machines return, and the crew refills canisters and changes batteries.

Trays of kelp, a vitamin and mineral-rich seaweed, are ready to be transplanted to bigger growing spaces at Alesca Life's demonstration farm. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Zhang used to hire four or five workers to walk the fields with backpack sprayers for five days. Now, the drones cover his crops in a morning and use 30 percent less chemicals, he said.

That’s what the government needs to hear as it tries to make China’s food supply safer.

“This is much easier and much faster than before,” Zhang said. “This is the future. Many farmers are switching.”

Vertical Farming: Farms of the Future? The Pros & Cons

Vertical Farming: Farms of the Future? The Pros & Cons

Even though more than 40 percent of American land is farmland, more people than ever before are moving into cities. Many of us may never step foot on a farm, and unless you’re lucky enough to live near a local farmers’ market, you’re likely at the mercy of your local supermarket as to what types of fruits and veggies you can purchase and where they come from.

But while cities keep booming, people are more concerned than ever about where their food is coming from. Is there really a way to merge the two? Vertical farming, some say, is the answer.

What is Vertical Farming?

Vertical farming is a method of producing crops that’s quite different from what we normally think of as farming. Instead of crops being grown on vast fields, they’re grown in vertically, or into the air. This normally means that the “farms” occupy much less space than traditional farms: think farming in tall, urban buildings vs. farming outdoors in the countryside.

Vertical farming is credited to Dickson Despommier, a professor of ecology at Columbia University, who came up with the idea of taking urban rooftop gardens a step further, and creating vertical farming “towers” in buildings, that would allow all of a building’s floors, not just the rooftop, to be used for producing crops.

Most vertical farms are either hydroponic, where veggies are grown in a basin of water containing nutrients, or aeroponics, where the plants’ roots are sprayed with a mist that includes water and the nutrients required to help the plants grow. Neither require soil for the crops to grow. Usually artificial grow lights are used, though in places blessed with an abundance of natural sunlight, it might be a combination.

And, in some places, it seems to be working quite well. Sky Greens is in Singapore, a country with a population of more than 5.5 million on a main island that’s just 26 miles wide and 14 miles long. In a four-story rotating greenhouse, the company produces 1 ton of greens each day, impressive for a country that imports about 93 percent of its produce, since there’s little available land.

Back in the States, AeroFarms, based out of Newark, NJ, operates several farms. Its global headquarters is a 70,000-sq. ft. vertical farming behemoth, the largest in the world, and can harvest up to 2 million pounds of produce annually. Additionally, AeroFarms helps area children get a little closer to the foods they eat. In a partnership with a local elementary school, students actually harvest their own greens in a 50-sq. ft. AeroFarms unit in their dining hall.

5 Benefits of Vertical Farming

While vertical farming is still relatively new, there are some real benefits.

1. There’s year-round crop production. Say goodbye to seasonal crops. Because vertical farms can control all of the technology required to grow the produce, there’s really no such thing as the wrong season. If a head of lettuce needs a certain amount of humidity and light, a vertical farm can arrange that. A growing season of just a few months is replaced with a year-round production.

Bonus: without things like bugs and weeds, vertical farms don’t need to use pesticides and other harmful chemicals to ensure plants keep growing.

2. They’re weatherproof. Every farmer knows that unseasonably cold or hot temperatures can affect an entire harvest, while a natural disaster like flood or hurricane can derail them for years. In a controlled environment like a vertical farm, there’s no need to fear Mother Nature.

3. They use less water conservation. Generally, vertical farms use less water than traditional farms. Most data points to a 70-percent reduction in water use compared to normal farms. As water becomes more scarce, particularly in communities already suffering from droughts, this is huge.

4. There’s less spoilage. Without the risk of fluctuating weather conditions or pesky critters, there’s a lot less food waste. On traditional farms, up to 30 percent of harvests are lost each year. (3) On vertical farms, that number goes way down.

Additionally, the food from vertical farms is usually sold locally, reducing transportation emissions and time from farm-to-table. Instead of several days of transport, during which foods can go bad, produce can be in the hands of a consumer in just hours.

5. They take up less space. In vertical farming, one acre of indoor space is the equivalent of 4-6 outdoor acres. A lot less space is necessary to produce the same amount of produce, particularly useful in cities, where outdoor land is limited. Instead of building out, vertical farms allow people to build up.

They also create farms out of places that already exist, like abandoned warehouses and buildings. AeroFarms’ space, for instance, was a nightclub space that was abandoned. There’s no need for new construction, because we can breathe new life into old spaces.

What’s Not So Great About Vertical Farms