Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

This Queens Warehouse With a Rooftop Produce farm is Sold As Part of a $78 Million Deal

This Queens Warehouse With a Rooftop Produce farm is Sold As Part of a $78 Million Deal

A rendering of the renovated warehouse at 184-60 Jamaica Ave. in Hollis - Courtesy of Madison Realty Capital.

By Robert Pozarycki | rpozarycki@qns.com

- Thursday, July 27, 2017 | 12:30 PM

Two warehouses in Hollis — including one topped with an urban produce farm — have been sold for $78 million, and the new owners have big plans to update both buildings, it was announced on Thursday.

Madison Realty Capital announced that it partnered with Artemis Real Estate Partners to purchase the industrial buildings located at 184-10 and 184-60 Jamaica Ave. from Rodless Properties LLC.

The adjacent structures house a number of commercial and manufacturing tenants including Gotham Greens, which has a 60,000 square foot greenhouse atop 184-60 Jamaica Ave. Gotham Greens uses the site to hydroponically grow leafy greens for sale to restaurants and consumers throughout New York City.

As with most real estate transactions, location was a prime factor in the acquisition, according to Josh Zegen, co-founder and managing principal of Madison Realty Capital. Jamaica Avenue is one of Queens’ busiest thoroughfares, and the warehouses are about a mile from downtown Jamaica. The buildings are also within walking distance of the Hollis Long Island Rail Road station.

“With the growing importance placed on expedient last mile delivery, today’s industrial sector tenants require proximity to population centers,” Zegen said. “We believe strongly that the combination of the site’s ideal location on Jamaica Avenue and our planned significant capital improvements will make this an attractive choice to numerous warehousing, distribution and manufacturing users throughout the city.”

Both Madison Realty Capital and Artemis plan “to upgrade both buildings including enhancing the building envelope, mechanical infrastructure and elevators, and capitalize on the increasing demand” from various industrial and commercial tenants “looking for quality industrial stock within the increasingly supply-constrained NYC market.”

According to PropertyShark, the building at 184-60 Jamaica Ave. encompasses 287,240 square feet, while the structure at 184-10 Jamaica Ave. has 226,605 square feet of space. Each building is five stories tall has an assessed value in excess of $11.3 million.

The buildings also have 12 loading docks and more than 100 parking spaces within a 30,000 square foot parking lot, Madison Realty Capital noted.

Madison Realty Capital has made $6 billion in investments across the city since its foundation in 2004, with holdings in the multi-family, retail, office, industrial and hotel sectors. Artemis has more than $2.5 billion of investor capital tied into various partners in the real estate industry.

Secret Garden: Palais des Congres Shares Rooftop Harvest

The garden also functions as a teaching tool, to show building owners and managers how to create green roof-tops.

Secret Garden: Palais des Congres Shares Rooftop Harvest

Angela MacKenzie, Reporter/Web Reporter @AMacKenzieCTV

Published Saturday, July 22, 2017 3:18PM EDT | Last Updated Sunday, July 23, 2017 11:33AM EDT

The Palais des Congres is known for hosting major events within is walls but what happens up on its rooftop is a well-hidden secret.

The convention centre has had a rooftop garden since 2010 where fruits, vegetables and herbs are grown.

“There are also edible flowers,” said Palais des Congres spokesperson Amelie Asselin. “It’s really a great harvest.”

The Palais de Congres convention centre has had a rooftop garden since 2010 where fruits, vegetables and herbs are grown. (CTV Montreal)

Initially the idea grew as a way to help reduce so-called heat islands in the downtown area, but the resulting harvest has proven to be an added benefit.

Each year the garden produces around 650 kilos of food, and much of the produce is used by the congress centre’s official caterer to feed delegates at the Palais.

The garden also functions as a teaching tool, to show building owners and managers how to create green roof-tops.

What’s more, it houses an experimental lab for urban agriculture techniques.

“The space that we use to produce the same quantity of strawberry is less because we are vertical farming,” Asselin explained.

Vertical methods also allow the berries to grow quickly, in addition to taking up less space than traditional farming.

The roof is also home to bee hives, which provide tasty honey but also help with pollination.

In fact, the rooftop honey was even given to former U.S. President Barack Obama as a souvenir gift last month when he was in Montreal to deliver a speech.

The garden is so fruitful that it actually produces more food than the Palais needs. So a portion of the harvest is donated to the Maison du Pere to help feed those less fortunate.

The shelter relies on donations to prepare the 1,000 meals it serves each day, and the fresh produce from the garden provides welcome and delicious ingredients.

An IGA In Montreal Is Growing Its Own Vegetables On The Roof

More than 30 different kinds of produce, including lettuce, kale, garlic and basil, are being grown on 25,000-square-foot roof. All of the produce is certified organic.

Required by Saint-Laurent to install a green roof, Richard Duchemin, the co-owner of IGA Extra Famille Duchemin, decided to plant a garden on it. ALLEN MCINNIS / MONTREAL GAZETTE

An IGA In Montreal Is Growing Its Own Vegetables On The Roof

JACOB SEREBRIN, MONTREAL GAZETTE

More from Jacob Serebrin, Montreal Gazette

Published on: July 19, 2017 | Last Updated: July 19, 2017 5:27 PM EDT

Required by Saint-Laurent to install a green roof, Richard Duchemin, the co-owner of IGA Extra Famille Duchemin, decided to plant a garden on it. ALLEN MCINNIS / MONTREAL GAZETTE

An IGA store in the Saint-Laurent borough says it’s the first grocery store in Canada to sell produce grown on its own roof.

More than 30 different kinds of produce, including lettuce, kale, garlic and basil, are being grown on 25,000-square-foot roof. All of the produce is certified organic.

Required by Saint-Laurent to install a green roof, Richard Duchemin, the co-owner of IGA Extra Famille Duchemin, said he decided to go a bit further.

Duchemin said he likes to offer locally grown produce to his customers and this was a chance to offer them the most local products possible. He said also he wanted to set an example for other grocery stores.

“Why don’t supermarkets plant vegetables on their roofs?” he said.

A garden bed ready for expansion at the huge rooftop garden at an IGA store in the Saint-Laurent district of Montreal. ALLEN MCINNIS / MONTREAL GAZETTE

A garden bed ready for expansion at the huge rooftop garden at an IGA store in the Saint-Laurent district of Montreal. ALLEN MCINNIS / MONTREAL GAZETTE

While the costs are higher, due to the small scale of the project, Duchemin said the produce grown on the store’s roof is being sold at the same price as any other organic produce.

The project is part of a partnership with The Green Line: Green Roof, a Montreal-based company that installs green roofs.

The Green Line is responsible for managing the actual growing of produce on the roof.

While many rooftop gardens opt for hydroponic systems, this one uses soil on the roof — which allows it to be certified organic.

However, because the soil is quite shallow, it limits the type of produce that can be grown, said Tim Murphy, a project manager for The Green Line. Large root vegetables, for example, aren’t an option.

Navy Yard Apartment Gives Residents Free Rooftop Produce Garden

Navy Yard Apartment Gives Residents Free Rooftop Produce Garden

By Jeff Clabaugh | @wtopclabaughJuly 13, 2017 12:25 pm

The Navy Yard apartment building has partnered with Up Top Acres to design and maintain a vegetable and herb garden on the roof, so residents can have access to a variety of produce through the summer and the fall.

WASHINGTON — F1RST Residences just upped the game for luxury apartment amenities in Washington, giving residents access to fresh, rooftop-grown produce.

The new 325-unit Navy Yard apartment building’s first tenants began moving in this spring.

The building has partnered with Up Top Acres to design and maintain a vegetable and herb garden on the roof, so residents can have access to a variety of produce through the summer and the fall.

There will be no cost for residents to participate in the garden program, and it will be entirely cared for by Up Top Acres.

The 470-square-foot garden will yield roughly 500 pounds of produce each year, including tomatoes, peppers, cilantro, parsley, thyme, rosemary, arugula, basil and zucchini.

“F1RST is giving its residents a community-supported agriculture program,” said Up Top Acres co-founder Kristof Grina. “This new farm will transform an underutilized part of the rooftop into a vibrant, productive living ecosystem — and bring ‘farm-to-table’ right in the same property.”

F1RST has already made extensive use of its rooftop.

The building, at First and N Streets in Southeast, includes a rooftop pool and hot tub, dog park, grills and D.C.’s only residential “stadium-style” seating with views into Nats Park.

The one- and two-bedroom apartments rent for $2,000 to $3,500 a month.

Urban Farming, Bolstered by Zoning Law Changes, Blossoms in NYC

Eagle Street Rooftop Farm in Greenpoint is one of several farms that has sprouted on rooftops around the city.(Credit: Annie Novak)

Urban Farming, Bolstered by Zoning Law Changes, Blossoms in NYC

By Ivan Pereira ivan.pereira@amny.com July 17, 2017

The seeds of New York’s rooftop farming industry, planted over the past decade, have yielded a harvest in recent years.

It has grown from a niche industry to a large-scale phenomenon, according to experts, thanks to a change in city regulations and a subsequent spur of investment.

And there’s potential for expansion in the years ahead, especially in Brooklyn and Queens.

“These large-scale greenhouses are advanced and expensive, but more and more consumers and businesses are supporting them,” said Nicole Baum, spokeswoman for Gotham Greens, a rooftop farm operator in Brooklyn.

The city changed its zoning laws in 2012 to allow rooftop greenhouses certain exemptions from limits on height and floor size on commercial and industrial properties. As a consequence, landlords have come to view them as a potential amenity and opportunity for profit.

“The landlords now see a way to use their space wisely,” said Annie Novak, a farmer who helped create the Eagle Street Rooftop Farm in Greenpoint in 2009. “Now there is a positive shift from the community who want to see these spaces.”

While the latest data on the number of urban farms comes from the U.S. Census — which said the city saw 11 new farms between 2007 and 2012 — agricultural experts point to a boom in the facilities on rooftops as evidence of the industry’s growth.

Sales from rooftop farms’ most common produce — collards, spinach, kale and other greens — have netted hundreds of thousands of dollars for farmers, with the average Brooklyn farm (on a rooftop or the ground) seeing $199,302 in sales in 2012, according to the Census.

For years, the biggest obstacle to rooftop farming was the cost.

An ideal space for a major harvest yield takes up 44,000 square feet, roughly an acre, according to an urban farming study released by Columbia University’s Earth Institute in 2013.

The space doesn’t come cheap; Brooklyn Grange’s 40,000-square-foot rooftop farm in Long Island City, for example, required $200,000 in startup capital in 2010.

After opening a successful 15,000-square-foot greenhouse on a rooftop in Greenpoint in 2011, Gotham Greens capitalized on the attention it was getting to grow its business.

“That was really a proof of concept,” Baum said of the initial facility.

The company reached various partnerships, including a deal with Whole Foods, that allowed it to build a 20,000-square-foot rooftop greenhouse on top of the Gowanus store in 2013.

Two years later, it opened a 60,000-square-foot facility on a Hollis, Queens, building and expanded to Chicago.

The city offers plenty of ready-made locations to allow for the industry’s further expansion, according to the Columbia University analysis.

It concluded that there were more than 5,701 private and public roofs in 2013 that, combined, were capable of holding 3,000 acres of rooftop farms. That’s nearly three and a half times the size of Central Park. Neighborhoods with the most rooftop space were Maspeth, Long Island City, Greenpoint and Sunset Park, according to the report.

Gabby Warshawer, the director of research for the real estate listing site CityRealty, said she’s hopeful building owners will use that potential as a selling point.

Eindhoven Unveils Plans For A Solar-Powered City Block With Living Roofs And Urban Farms

Billed as a contemporary and hyper-modern development, Nieuw Bergen will add 29,000 square meters of new development to Eindhoven city center. The sharply angled and turf-covered roofs give the buildings their jagged and eye-catching silhouettes that are both modern in appearance and reference traditional pitched roofs. The 45-degree pitches optimize indoor access to natural light.

Eindhoven Unveils Plans For A Solar-Powered City Block With Living Roofs And Urban Farms

by Lucy Wang

The Dutch city of Eindhoven just selected MVRDV and SDK Vastgoed (VolkerWessels) to create Nieuw Bergen – a super green block of homes and businesses topped with living roofs and solar panels. Located in the inner city area around Deken van Someren Street, the project’s seven buildings will comprise 240 new homes, 1,700 square meters of commercial space, 270 square meters of urban farming, and underground parking.

Billed as a contemporary and hyper-modern development, Nieuw Bergen will add 29,000 square meters of new development to Eindhoven city center. The sharply angled and turf-covered roofs give the buildings their jagged and eye-catching silhouettes that are both modern in appearance and reference traditional pitched roofs. The 45-degree pitches optimize indoor access to natural light.

“Natural light plays a central role in Nieuw Bergen, as volumes follow a strict height limit and a design guideline that allows for the maximum amount of natural sunlight, views, intimacy and reduced visibility from street levels,” says Jacob van Rijs, co-founder of MVRDV. “Pocket parks also ensure a pleasant distribution of greenery throughout the neighborhood and create an intimate atmosphere for all.”

Related: The Sax: MVRDV unveils plans for a ‘vertical city’ in Rotterdam

Each of Nieuw Bergen’s structures is different but collectively form a family of buildings that complement the existing urban fabric. Gardens and greenhouses with lamella roof structures top several buildings. A natural materials palette consisting of stone, wood, and concrete softens the green-roofed development.

INTERVIEW: Architect Thomas Kosbau On The Exciting Future Of Sustainable Design In NYC

INTERVIEW: Architect Thomas Kosbau On The Exciting Future Of Sustainable Design In NYC

POSTED ON MON, JUNE 26, 2017BY EMILY NONKO

Since Thomas Kosbau began working for a New York consultancy firm running its sustainable development group, in 2008, much has changed in the city’s attitude toward green design. Kosbau has gone from “selling” the idea of LEED certification to building developers, to designing some of the most innovative sustainable projects in New York to meet demand. He founded his firm, ORE Design, in 2010. Soon after, he picked up two big commissions that went on to embody the firm’s priority toward projects that marry great design alongside sustainability. At one commission, the Dekalb Market, ORE transformed 86 salvaged shipping containers into an incubator farm, community kitchen, event space, community garden, 14 restaurants and 82 retail spaces. At another, Riverpark Farm, he worked with Riverpark restaurant owners Tom Colicchio, Sisha Ortuzar and Jeffrey Zurofsky to build a temporary farm at a stalled development site to provide their kitchen with fresh produce.

From there, ORE has tackled everything from the outdoor dining area at the popular Brooklyn restaurant Pok Pok to the combination of two Madison Avenue studios. Last November, ORE launched designs for miniature indoor growhouses at the Brooklyn headquarters of Square Roots, an urban farming accelerator.

ORE’s latest project—and the one Kosbau feels best embodies his design philosophy—is Farmhouse, a sustainably-designed, minimalist community venue and kitchen for the city organization GrowNYC. The Union Square building features a live indoor growing area, fully-functioning kitchen, and a design inspired by the traditional geometry of the American barn. Kosbau and GrowNYC have continued their partnership to design a massive Bronx agricultural distribution center for the organization, to be called FoodHub. When it opens, the building will employ the city’s first closed-loop, entirely organic energy system that utilizes self-purifying algae blooms generated by rainwater. The system, of course, was designed by Kosbau.

With 6sqft, Kosbau discusses how his early projects set the tone for ORE Design, what’s unique about sustainable work in New York City, and how designers have to step up to the plate to offer great design that also happens to be environmentally friendly.

So you came to New York from Oregon.

Thomas: Yes, born and raised in Portland, Oregon. When I moved to New York, it wasn’t at the forefront of my mind for what kind of designer I was. But I think inevitably it’s influenced a lot of my design work.

What factors led you to start a firm in 2010?

Thomas: A combination of many different elements, which has resulted in some of our best projects. Part of it was the recession. I worked five years for another architect as a sustainability consultant in real estate. After a year, the recession hit, and the firm came to a cataclysmic halt. It made me question what would come next, and I already started receiving queries from my network to pick up small projects. I gravitated toward design work, small residential projects, then a store.

But the real culminating event was that I submitted an entry for the IIDA green idea competition hosted in Korea, in 2010. My design was a replacement for asphalt—an ubiquitous material in the world. I put together a proposal for replacing the world’s asphalt with organically-grown sandstone, as way to offset numerous health concerns associated with it.

I won that competition around the same time I received two major commissions from relationships I started years before. One was the Dekalb Market, the shipping container market in Downtown Brooklyn, and the other was Riverpark Farm, the first portable rooftop farm in an urban environment. There, we used milk crates to create a temporary farm on a stalled building site. Both were products of the economic downturn—they were stalled building sites that needed activation for various reasons.

Dekalb Market, courtesy ORE Design

Tell me more about Riverpark Farm.

Thomas: It was a site located right next to Riverpark, the restaurant owned by Tom Colicchio. The team was pretty forward thinking about doing something with this empty land. So they reached out to GrowNYC to think of a solution for a farm that would potentially be moved within a year. GrowNYC tapped our shoulder to do that.

Riverpark, courtesy ORE Design

It seems like these early projects set a tone for your firm, and how it thinks about sustainability.

Thomas: I think the gene that was inside of me from Oregon—mostly from my mother, who founded a community gardening program in Portland—was dormant. But as soon as the need became a higher-level issue, and designers became tasked with thinking about these things, the influence ingrained in who I am came out. The environment revealed this direction and ultimate design brand.

What makes NYC an interesting or challenging place to experiment with sustainable design?

Thomas: You can debate whether this is the most urban place in the world; it’s certainly the most urban environment in the United States. It’s also one of the most concentrated and most interesting environments in terms of diversity. There are so many ideas from around the globe that find a home here and are placed in a small dense environment.

Land is so critically valuable, as well, so people consider it precious. To see food, community gardens, and urban agriculture become such a priority is a litmus for how important it is to the world. We’re seeing rapid urbanization across the globe, and there’s been an influx of residents to New York making the land more precious.

It’s an exciting environment. There are so many different factors on how to use land, what’s considered valuable in green design, and thinking about design that’s equally productive as it is attractive.

Since founding your firm, have you seen a rise in awareness in sustainable design?

Thomas: I have witnessed a shift in priorities. It’s more accepted as a norm to be sustainable, and less of a selling point. LEED was an early vehicle to sell sustainability—we really had to sell developers on how these features could bring a return of value, even if it’s just from a branding standpoint. LEED has become so ubiquitous that’s not the case anymore, and I don’t think that’s a bad thing. The real revolution is that it made material sustainability an absolute must for projects. LEED created a market for sustainable materials to outperform other materials in sales. That’s the real shift. It’s that the choice is easier, and sustainable materials have become as performative, in terms of longevity, have much less of a cost premium, and there’s more variety.

The next step is good design. Making green design interesting, without being tagged green design.

What projects of yours really embody that idea?

Thomas: Farmhouse was our first project to unify our core values with our design aesthetic. It’s our first embodiment of “this is who we are.” It has the nonprofit roots, as a community space with an educational component for GrowNYC. Then there’s the green technology with the hydroponic walls, and food production on site. We did research into recycled materials that solve design issues, evidenced in the acoustic panels we chose. That became our major design move—to use acoustic panels we had pre-manufactured in our geometry, and unite the space with one design feature. It’s not only aesthetic, it balances the acoustics of the space and it’s a placemaker.

Inside farmhouse, courtesy ORE Design

We also used solar tubes to bring natural light into the darkest spaces, and we sourced hardwood from a forest that was drowned in the 1960s. That feature is then awash in natural light.

Farmhouse, courtesy ADG – Amanda Gentile Photography

We didn’t pursue the LEED designation for Farmhouse, though it could easily be Gold if not higher. We offered the option for the client, but LEED is no longer an identifier as an interesting, sustainable space. We pushed the design to make it a unique space. That’s on the shoulder of designers now, we have to be better to make these spaces speak for themselves.

So what’s next for the firm?

Thomas: GrowNYC is working on a really cool project up in the Bronx, a regional food hub. GrowNYC supplies the food for the city’s green markets, and it’s a huge task. The president of GrowNYC and his staff feel they’ve mastered the logistics for moving food in small quantities, and want now build a larger distribution center for farm fresh produce they can bring into the Bronx to distribute to various programs. It would be tenfold of what they’re able to provide now. They’ve tapped us to look at how to make a highly-performative building, with offset carbon emissions and localized power production. We also designed an “anthropomorphic stomach” for the building—a “bio digester” that would take food waste to provide energy for the electricity and heat of the facility.

275 South rooftop forest, courtesy ORE Design

L&M Development also tapped us to create a roof amenity for one of their buildings [275 South, in the Lower East Side]. The building is a 1970s, poured-in-place concrete bunker. It has a huge, bearing capacity. We looked at what it would take to allow large groups on roof—we needed to put a certain amount of steel to get to that level. We also wanted to maximize the view, so we elevated the steel above the existing concrete parapet. With the bearing weight, and 40 inches of room from the new roof to the existing roof, we realized we could plant a forest up here. That’s what we decided to do. We’re planting 80 mature aspen trees, and conceptually carving into the forest floor so the benches are situated within the forest, and trees frame different views toward Brooklyn.

If it’s done in time it will be the location of my wedding in September. The client didn’t have a problem allowing me to do that because they knew it’d get done quickly.

RELATED:

7 Ways Chicago Is Becoming the New Beacon of The Sustainable Food Movement

Chicago is undergoing a foodie revolution. From passing the nation’s largest soda tax to exploring new and intriguing options for local food, the Windy City is making leaps and bounds to become a beacon of sustainability.

7 Ways Chicago Is Becoming The New Beacon of The Sustainable Food Movement

JULY 5, 2017 by EMILY MONACO

Chicago is undergoing a foodie revolution. From passing the nation’s largest soda tax to exploring new and intriguing options for local food, the Windy City is making leaps and bounds to become a beacon of sustainability.

Don’t believe us? Here are seven fantastic initiatives the Windy City has undertaken to further the transition to great, sustainable food.

1. MightyVine Restores Damaged Farmland with Tomatoes

Just west of Chicago in the prairie town of Rochelle, IL, indoor tomato grower MightyVine has restored acres of farmland that had been damaged by a developer. The growers use Dutch technology comprising a special diffused glass and radiated heat to grow tomatoes 365 days a year. The super-local tomatoes are delivered to stores just a few hours away in Chicago as soon as they’ve been picked.

Sustainability is particularly important to MightyVine farmers, who have managed to provide a 90 percent water savings over field-grown tomatoes, not to mention reduced pesticide use as compared to most conventional growers.

2. Homestead on the Roof Gets Its Organic Produce Ultra-Locally

You can’t get more local than the organic produce grown on the 3,500-square-foot organic rooftop garden at Homestead on the Roof. Executive Chef Scott Shulman has his pick of herbs, chilies, tomatoes, peas, and more to concoct his versatile, seasonal menu, which is served on the 85-seat patio that sits right next to the rooftop garden, which also features two vertical hanging gardens, and dozens of planter boxes.

3. Daisies Keeps Local Produce in the Family

When Daisies opened last month, Chef Joe Frillman realized his dream of combining his passion for handmade pasta and locally sourced crops, almost all of which come from Frillman’s brother’s farm in nearby Prairie View, IL. But Frillman is taking the old trope of locally sourced ingredients to the next level, with the goal of rolling out an in-house fermentation program, too.

Daisies is also making strides in recycling cooking oil: used cooking oil is donated to be recycled for biodiesel, and the resulting profits are donated to charity.

4. Slow Food Chicago Highlights the Importance of Community Gardening

Member-supported non-profit Slow Food Chicago is one of the largest chapters of Slow Food USA, with more than 500 members. Its myriad projects include the preSERVE Garden, a project created in 2010 in cooperation with the North Lawndale Greening Committee, the Chicago Honey Co-Op, and NeighborSpace.

In 2013, the city lot harvested more than 430 pounds of food from 31 different crops, and the garden continues to grow today.

5. The Urban Canopy Attacks the Problem of Nutrition in Schools on the Local Level

Founded in 2011, the Urban Canopy comprises an indoor growing space and a two-acre community farm in the Englewood neighborhood of Chicago. But more than mere growers, the Canopy members see themselves as “educators and advocates for the urban food movement.”

Founder Alex Poltorak’s vision began while working with Chicago Public Schools as an Education Pioneer Fellow. After exploring how nutrition affects children in school, he was inspired to create the project to utilize idle urban spaces to attack this problem at the community level. Through volunteer availabilities, a Compost Club, and a CSA, the group endeavors to “make farming as easy as possible on as many unused spaces as possible.”

6. Chicago O’Hare Brings Gardening to the Gate

An unused mezzanine space of Chicago O’Hare Airport’s G terminal has been transformed into the world’s first “aeroponic” garden by Future Growing LLC. The garden, made up of a series of vertical PVC towers where herbs, greens, and tomatoes are grown, uses a mere five percent of the water normally used for farming.

The produce grown in the airport is used by local chefs, including Wolfgang Puck, who runs a restaurant in the airport.

7. Marty Travis Transforms Nutrient-Sapped Soil into Sustainable Farmland

Marty Travis is a seventh-generation Illinois farmer. As his farming community fell victim to Big Ag, Travis decided to do something about it. He created Spence Farm, a 160-acre beacon of biodiversity where he grows a variety of ancient grains and heirloom fruits and vegetables and raises heritage breed livestock, nearly all of which is sold locally to chefs in Chicago. His story of preserving the history and practice of small sustainable family farming in is told in the film Sustainable Food.

This Amazing Farm In A Box Can Pop Up On Any City Street

Over the past decade, urban farming and community gardeninghave grown in popularity, with small gardens sprouting on top of skyscrapers – but they can be complicated and require elaborate supplies. EkoFarmer is a 13-meter long farming module that can be installed where there is a water and electrical supply. Containing ecological

soil developed by Kekkilä, EkoFARMER was designed to produce optimal yields and be used for both commercial and scientific purposes.

This Amazing Farm In A Box Can Pop Up On Any City Street

Over the past decade, urban farming and community gardeninghave grown in popularity, with small gardens sprouting on top of skyscrapers – but they can be complicated and require elaborate supplies. EkoFarmer is a 13-meter long farming module that can be installed where there is a water and electrical supply. Containing ecological soil developed by Kekkilä, EkoFARMER was designed to produce optimal yields and be used for both commercial and scientific purposes.

Exsilio is currently on the lookout for co-creation partners that are interested in developing their own farming modules based on their own requirements. Restaurants and institutional kitchens can benefit from EkoFARMER, which can also function as an excellent complementary solution for farmers to expand their traditional greenhouses.

“EkoFARMER is an excellent option for business fields in need of salads, herbs, (edible) flowers or medicinal plants, for example. The social aspect of urban farming is also prominent. For this reason, our solution is suitable for associations wanting to earn some extra income, or societies wanting to offer meaningful activities for the unemployed, for example. This is an opportunity to create new micro-enterprises”, said Tapio.

Farming Takes Root In The City

Long the domain of rural areas, commercial farming operations are now starting to take root in urban neighborhoods.

Farming Takes Root In The City

By Gerry Tuoti

Wicked Local Newsbank Editor

Posted Jun 23, 2017 at 2:13 PM | Updated Jun 23, 2017 at 3:18 PM

THE ISSUE: The state Department of Agricultural Resources is preparing to award grants to urban farming projects. THE IMPACT: In five years, the DAR has awarded nearly $1.5 million in grants for 51 projects and nearly 20 organizations.

Long the domain of rural areas, commercial farming operations are now starting to take root in urban neighborhoods.

“Demand has been really strong for this,” said Rose Arruda, urban agriculture coordinator for the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources, which has awarded approximately $1.5 million in urban farming grants over the past five years.

Perched up on rooftops, packed into greenhouses or spread across vacant lots, urban farmers grow a variety of crops to sell to customers in their communities.

High above Boston’s Seaport District, John Stoddard and Courtney Hennessey began farming the roof of the Boston Design Center in 2013. Dubbed “Higher Ground Rooftop Farm,” they lined up several Boston restaurants as customers and sold fresh produce out of kiosks on site at the Boston Design Center.

While working to fine tune his business model, Stoddard decided last year to narrow his focus to supplying smaller numbers of restaurants with fresh ingredients. This year, he’s devoting most of his attention to Boston Medical Center, which hired him to run a 2,300-square-foot rooftop farm that provides produce for the hospital’s food services program and food pantry.

“It’s great that the at the city and state level they are being supportive of trying to figure out how to make urban agriculture work and thrive,” Stoddard said.

Since it launched its urban agriculture grant program in 2012, the state has awarded funding to projects in cities across the state, including Somerville, Salem, Boston and Worcester. The Department of Agricultural Resources will begin reviewing applications for the next round of grant funding in July.

“It’s state money and we want to make sure the money we’re expending is supporting economic development in communities,” Arruda said.

Ed Davidian, president of the Massachusetts Farm Bureau Federation, said he supports the state’s investment in urban farming grants, as long as public funds aren’t being sunk into unviable enterprises.

“I think it’s a good thing, but sometimes you wonder whether the input equals the yield,” he said. “I don’t know if it works on an economic scale, but it could be good in little niche markets. I’m sure it works in some applications and not in others.”

While traditional farms often rely on machinery, it’s not practical to use tractors and other equipment on rooftop farms or in urban settings. For city farms, that means more manpower is often needed. A large portion of their operating costs, therefore, are devoted to payroll.

While community gardens have been around for decades in many cities, commercial urban agriculture is a newer trend.

“A community garden plot is really for personal use,” Arruda said. “An urban farm is a real business. It’s intensively farmed to have produce, vegetables and fruit available for sale in that community.”

Some sell to local restaurants. Others sell to customers who sign up for a farm share, or Community Supported Agriculture program. Most offer their crops at farmers’ markets, and many also donate produce to local food pantries.

The “eat local” movement, which has generated new interest in where food comes from, has helped fuel the small, but growing, number of urban farms in the state, Arruda said.

“I feel like the dust has really settled where that farm-to-table excitement has died down and now the folks who are really serious about farming have stuck with it,” she said.

Rooftop Garden Grows On Hell’s Kitchen Farm Project Volunteers

Rooftop Garden Grows On Hell’s Kitchen Farm Project Volunteers

Added by Scott Stiffler on June 14, 2017.

Saved under News, Features

How does their garden grow? Kiddie pools, pots, and hanging planters play host to good green things on the roof of Metro Baptist Church. Photo by Rebecca Fiore.

BY REBECCA FIORE | When Jennifer Shotts moved to New York City from Kansas, she knew she wanted to be a part of the community. As a self-professed environmentalist, Shotts was shocked at how much trouble she had finding a community garden.

New York Cares, which guides volunteers to places where they can work to improve education, revitalize public spaces, and meet the immediate needs of those living in poverty, placed her at Metro Baptist Church (410 W. 40th St., btw. Ninth & Dyer Aves.).

At first, she helped out in the food pantry. “Then someone said to me, ‘Have you seen the rooftop?’ I thought, what’s up there? I trekked all the steps and just fell in love with it,” Shotts recalled, of that moment over three years ago.

Four flights of stairs above the food pantry is the Hell’s Kitchen Farm Project (HKFP), a 4,000-square-foot volunteer-run rooftop garden containing 52 kiddie pools, 38 pots, and 20 rail hanging planters tasked with growing fresh, organic fruits, and vegetables.

HKFP was created in 2010 as a response to the rapid gentrification happening in the neighborhood. Clinton Housing Development Company, Metro Baptist Church, Rauschenbusch Metro Ministries, and the Metropolitan Community Church created HKFP as a way to provide fresh produce for all.

“There aren’t a lot of affordable grocery stores in this area and there was a concern that low-income people, especially the food pantry clients who weren’t really able to eat fresh, healthy vegetables,” Debbie Mullens, a third-year volunteer, said.

Lettuce, tomatoes, Swiss chard, kale, collared greens, radishes, scallions, mustard greens, bok choy, apples, blueberries, and raspberries grow in the kiddie pools and pots, while herbs are grown in the rail-hanging planters.

Kiddie pools are used because they are light-weight and don’t put too much pressure on the 20th century building’s structure, Rev. Tiffany Triplett Henkel said. Henkel is a pastor at Metro Baptist Church and executive director of Rauschenbusch Metro Ministries. “We farm from April to about mid-December,” Henkel explained, though they have experimented in the winter months, growing cover crops to keep the soil rich.

Thursdays and Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., the farm is open to the public for gardening. Shovels, trowels, sunscreen, gloves, and clippers are provided.

“Everything that we grow here goes down to the food pantry on the first floor,” Mullens noted. “Everything is donated. None of it is sold and the volunteers don’t take any food home with them.” She said on a good day there can be between 10 to 30 people on the roof. Currently, there are over 20 plants growing, with half a dozen more on the way as the summer months approach.

“In the course of the year we will probably have between two hundred to three hundred people gardening with us,” Mullens said. A regular volunteer could vary from a young adult learning about crops to a retired folk trying a new hobby out, she said. Groups often come up, corporate volunteers such as Morgan Stanley, Zipcar, and Hermes, as well as educational groups from local schools.

“Urban agriculture appeals to a wide variety. We have folks of all walks of life,” Henkel said.

The volunteers harvest the crops, weigh them, and upload their records to Farming Concrete, which is (according to their website) “an open, community-based research project to measure how much food is grown in community gardens and urban farms.” It is supported by the New York City Community Garden Coalition. They provide scales all over the city.

The pantry at Metro Baptist Church, which is open Saturdays at 11 a.m., is described as a client’s choice-style, according to Mullens, where community members can come pick out the foods they prefer.

“As the folks come through they can select what they want, rather than just walking in and somebody handing them a bag of who knows what,” she said, and noted that the food pantry currently has about 750 clients.

The Hell’s Kitchen Farm Project’s table, at May 20 & 21’s Ninth Avenue International Food Festival. Photo by Christian Miles.

Additionally, this will be the farm’s second year with high school interns working on the garden and learning about how to make a difference in their communities. All local high schoolers, experienced with farming or not, are welcome. The Urban Farm Intern Program selected 10 students to work 15-20 hours a week for six weeks from July 5 to Aug. 12. A modest stipend will be given to them.

“Last year, we had eight students for four weeks and this year we will have ten students for six weeks,” Henkel said.

These interns will not only have a hands-on experience to planting and harvesting, but also have classroom time where they will learn from professors of agriculture and other professionals.

“Interns will be learning about urban and non-urban agriculture techniques, how to care for and grow food,” Henkel said. “But more than that even learning about food systems and when they are compromised, nutrition, and how communities can address food needs.”

Also, the farm is gaining its first college intern from Berea College in Kentucky for June and July. Mullens said she is excited for the new interns to come in after the success of last summer.

“I think these kids came away with a much better idea of what food justice is and how you can impact hunger issues through urban agriculture,” she said.

In further addition to the interns, the rooftop, and the pantry, HKFP also has a program in connection with a local farmer. The Community Support Agriculture, or CSA, program provides people living in the neighborhood to purchase fresh and locally grown food from Nolasco Farm in Andover, NJ. There are weekly, and bi-weekly shares.

“The concept of the CSA is you support the farmer upfront. That way the farmer can buy what he needs. It’s a form of supporting local farmers,” Henkel said. A full share for 22 weeks costs $550, while a half share, every other week, is $275. Three hours of volunteer work is required, “that’s the spirit of it,” Henkel said.

People can also sponsor shares that will provide fresh food to other local pantries. “While we are proud of the food we are able to grow and give to the food pantries, getting education around food is more important,” Henkel said. “If we can work with a younger generation then they can learn to advocate for themselves and their community. We are growing more than food.”

For more information, visit hkfp.org, mbcnyc.org, clintonhousing.org, rmmnyc.org, mccchurch.org, farmingconcrete.org, and http://nyccgc.org.

The door is always open to volunteers. Photo courtesy Hell’s Kitchen Farm Project.

5 Repurposed Warehouses Turned Indoor Farms That Need No Land Or Sun To Grow Crops

5 Repurposed Warehouses Turned Indoor Farms That Need No Land Or Sun To Grow Crops

June 15, 2017 Chuck Sudo, Bisnow, Chicago

Earth's population is expected to reach 8.5 billion people by 2030. That is 8.5 billion mouths to feed. With dwindling land resources and soaring farming costs across the country, vertical indoor farms may be a solution to feeding the world. Often repurposed from former warehouses, the indoor farms need no sunlight or pesticides and require less water to grow produce.

Following are five indoor farms leading the pack.

1. AeroFarms

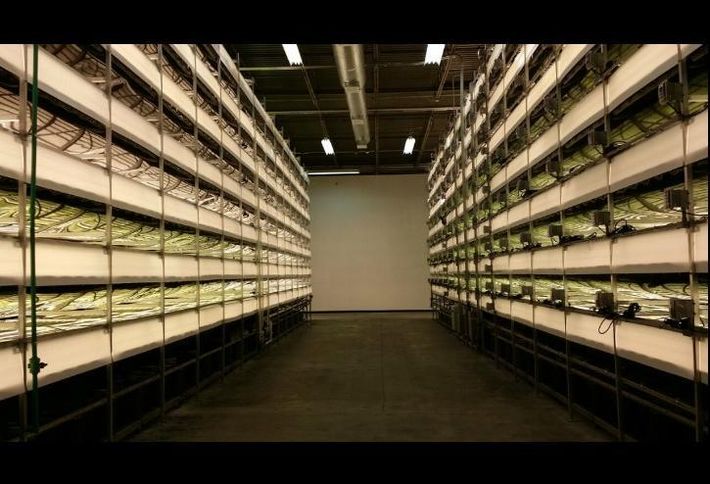

AeroFarms, Newark, N.J.

Location: Newark, New Jersey

Produce Grown: Baby greens and herbs

Company/Owner: AeroFarms At 70K SF, the world's largest indoor vertical farm cost $39M to build, and uses LED lights and computer controls to tailor the lighting for each plant. A closed-loop aeroponic system mists the roots of the greens and reduces water usage by 95%. Constant monitoring of nutrients allows AeroFarms to grow a plant from seed to harvest in half the time of a traditional farm. AeroFarms produces 2 million pounds of produce a year.

2. Gotham Greens

Courtesy of Gotham Greens rooftop greenhouse in Chicago

Location: Gotham Greens operates greenhouses in Brookln, Queens and Chicago's Pullman neighborhood.

Produce Grown: Eight types of lettuce, tomatoes, arugula, basil and bok choy Company/Owner: Gotham Greens A pioneer in the indoor farming industry, Gotham Greens built its first rooftop greenhouse in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, and installed solar panels, LED lighting, thermal curtains and a recirculating irrigation system to offset electrical use and reduce water usage. Gotham Green's newest greenhouse in Chicago is located on top of the Method home products plant and cost $8M to build. At 75K SF (or two acres), it produces a crop yield equal to that of a 50-acre farm.

3. Green Sense Farms

Green Sense Farms, Portage, Indiana

Location: Portage, Indiana

Produce Grown: Micro and baby greens, lettuce and herbs Company/Owner: Green Sense Farms Green Sense's 30K SF farm is capable of growing produce for up to 20 million people within a 100-mile radius. The farm is equipped with customized LED lights from Dutch technology firm Royal Philips and grows its produce in automated carousels, while computerized controls provide perfect conditions for year-round farming. Green Sense CEO Robert Colangelo believes his model is scalable and last year raised over $400K in equity crowdfunding to help build a nationwide network of similar indoor farms.

4. Bowery Bowery

Bowery Farming, Kearny, N.J.

Location: Kearny, New Jersey

Produce Grown: Baby kale, arugula, butterhead lettuce and basil. Company/Owner: Bowery Dubbing itself the world's "first post-organic greens" grower, Bowery uses LED lights to mimic sunlight, grows its greens in nutrient-rich water trays stacked from floor to ceiling, uses data analysis to monitor plantings from seed to harvest and robotics to harvest the crops. Investors love what Bowery is doing so much that the company announced Wednesday that it raised $20M to expand its operations in the U.S. and overseas. Bowery raised $7.5M in February from a pool of investors including "Top Chef" judge and chef Tom Colicchio.

5. Local Roots Farms

A shipping container farm from Local Roots Farms

Location: Vernon, California

Produce Grown: Baby and micro greens Company/Owner: Local Roots Farms Local Roots Farms is innovating urban farming design and building indoor farms from 40-foot-long shipping containers. These portable indoor farms are capable of producing the equivalent of a five-acre farm. Local Roots believes this model will disrupt food deserts around the world by setting up the container farms where they are needed most.

Urban Farming Reaches New Heights At Levi’s Stadium

Urban Farming Reaches New Heights At Levi’s Stadium

Emily Saeger, full-time gardener at Faithful Farms, harvests produce to send downstairs to the Levi’s Stadium kitchens. (Courtesy Isha Salian)

By ISHA SALIAN | PUBLISHED: June 10, 2017 at 7:00 am | UPDATED: June 12, 2017 at 11:11 am

SANTA CLARA — Five varieties of kale. Fresh arugula, lettuces and herbs arranged in neat rows. It’s a typical Californian vegetable garden — except it’s nine stories off the ground. The patch of greens and morning sunlight are juxtaposed against the industrial metals, bright billboard display and giant corporate logo in the backdrop. Levi’s Stadium, the sign proclaims.

This well-manicured garden, planted last year, is the first to top an NFL stadium. The Atlanta Falcons are following suit with a raised-bed garden of their own, and baseball stadiums are already in on the game: Boston’s Fenway Park set up a rooftop garden in 2015, and San Francisco’s AT&T Park boasts a vegetable garden behind center field.

Taken together, the unexpected confluence of professional sports and organic gardening signals just how far the sustainability conversation reaches — but also accentuates the role corporate patronage plays in enabling green urban design. Authentic local food production and energy savings aside, these gourmet, microgreen-rich enterprises are a far cry from the gritty, empty lot urban farms that defined the urban agriculture movement for the last two generations.

Christened “Faithful Farm,” Levi’s Stadium’s rooftop garden opened in July 2016 as a subsection of the stadium’s 27,000-square-foot green roof. As spring planting season nears, Faithful Farm produces 500 pounds of produce per month, on average.

“Originally, this roof was designed just as an ornamental perennial space,” said Emily Saeger, Faithful Farm’s full-time gardener. “It was all grasses and succulents.”

This much lower-maintenance green roof was incorporated into the stadium’s design early on, said Jim Mercurio, vice president of operations and general manager at Levi’s Stadium. Green roofs save energy by keeping the stadium cooler, reducing air conditioning costs. It earned the stadium points for LEED certification (a third-party accreditation for green building design), allowed them to demonstrate a commitment to sustainability and also just looked good.

But then Danielle York, wife of San Francisco 49ers CEO Jed York, had an idea. She had hired urban farming venture Farmscape Gardens to landscape her backyard in Los Altos Hills, and asked Farmscape’s co-owner if she could develop a farm on the roof of Levi’s Stadium. The stadium’s operations team green-lighted the project on May 15, 2016. Just six weeks later, the garden was planted.

“When we looked at what we wanted at first, which was to have a natural garden of sorts, we didn’t take it to the next level,” Mercurio said, looking out over the greenery. “This is taking it to the next level.”

The garden has been expanded twice since it opened in July, and now occupies 6,500 square feet, about one and a half times the size of an NFL endzone—not counting pathways. Food grown in the garden (primarily leafy greens and herbs during the winter months) takes a short elevator ride each day down to the stadium kitchens, where it is used in dishes served at the stadium’s restaurants and private events. “It’s the whole farm-to-fork concept coming to life,” said Mercurio.

A rooftop lettuce supply is only the tip of the iceberg for Levi’s sustainability efforts. The stadium uses 85 percent recycled water, has a solar panel canopy and has received multiple sustainability awards. It’s the first stadium to open with LEED Gold certification, and last year achieved LEED Gold for operations and maintenance too. LEED recognition is a sustainability stamp of approval for the San Francisco 49ers, and can in turn attract more business for the stadium. A 2014 Nielsen survey found more than half of respondents were willing to spend more on products and services from eco-friendly companies. But Mercurio says the stadium’s owners have more in mind than positive publicity.

“Titles are great, being the first to do this or that it’s okay, it’s fine,” Mercurio said. “But it’s part of a greater movement. If someone does it bigger and better than us, we’d encourage that. If we had a role in making the environmental and the sustainability conversation bigger, that’s awesome.”

Farmscape also manages the garden at the San Francisco Giants’ AT&T Park. The company was started nine years ago in Los Angeles, and its Bay Area branch focuses primarily on gardens for corporate buildings and multifamily residences.

“We’d never gotten a project like this; it was so exciting,” Farmscape co-owner Lara Hermanson said. “They have a weather station down here for the roof. This place is the coolest.”

The funding and support from the stadium let Farmscape find its way in the relatively new space of rooftop gardening. “There are plenty of examples of people putting a planter on a roof,” said Hermanson. But gardens set directly onto a standard aluminum roof are much rarer — a 5-year-old East Coast urban farming company is the oldest she can think of. “Really no one has the expertise yet.”

Green roofs, whether or not they include edible plants, have several benefits. They reduce the cost of heating and cooling a building by decreasing the temperature of the roof. They also mitigate the urban heat island effect, which occurs when asphalt roads and concrete pavement and roofs soak up and reflect sunlight as heat, resulting in a higher air temperature in urban centers than suburban and rural areas. If the green roofs grow produce, they also diminish the cost of transporting fresh produce from rural areas to urban centers.

But can a rooftop farm actually grow enough produce to turn a profit? Finding an economically sustainable model for urban agriculture isn’t as easy as reaping the environmental benefits. Getting urban agriculture to support itself solely on the value of its produce is difficult, particularly in places like the Bay Area where land values are high.

Top Leaf Farms, another rooftop farming venture on a residential complex in Berkeley, aims to produce as high a rooftop crop yield as possible, selling the produce grown to high-end restaurants in Berkeley and the building’s residents. These upscale restaurants pay a premium for the hyper-local produce, allowing Top Leaf to sell to locals at lower prices through their website — a pound of beet greens, for example, was priced at three dollars this week.

Co-owner Benjamin Fahrer points out that with Levi’s Stadium, the 49ers paid for the farm’s installation and continue to pay for its maintenance by Farmscape. As part of a much larger system, it doesn’t really matter whether Faithful Farm as an entity is profitable. He says there’s an opportunity cost to having walkways and flowers, as Faithful Farm does — something he must be conscious of as the owner of a for-profit farming company. “As soon as you want to make it look better, your costs go up,” he said.

Green infrastructure expert Elizabeth Fassman-Beck agreed, “If you’re looking for a cost-effective system, you don’t want to waste water on the roof for specific plants because they look good.”

Having less pressure to be turn a profit has perks beyond the ability to plant a row of flowers instead of edible greens. Nonprofit, community-based urbanfarms “are producing a yield of social equity, while we’re trying to get yield that is productively and financially viable,” Fahrer said. These socially productive farms engage the community, save energy and raise sustainability awareness even if they don’t actually net a profit for the owners.

“The environmental impact of urban development is enormous,” said Fassman-Beck, an associate professor at Stevens Institute of Technology, in Hoboken, New Jersey. “Anytime we can encourage leading by example and champion this sort of technology, that’s going to have widespread positive impacts.”

Whether the primary mission of a rooftop farm is to be profitable and environmental friendly, the sustainability benefits remain the same. And though Levi’s Stadium is the first NFL stadium to take this step, major construction projects from all kinds of industries seem certain to follow suit.

“It’s not a surprise to me that the team in Northern California was the first in the nation to be like ‘Let’s do an organic farm,’” Hermanson said. “It’s almost expected now that a world-class venue like this would have their own vegetable garden—their own herb production at least.”

Urban Farming in Singapore Has Moved Into A New, High-Tech Phase

In community gardens found in housing estates, schools and even offices, urban farms are taking root in Singapore. Such farms are not ornamental gardens. Instead, gardeners plant vegetables and fruit such as cabbage, basil and lime to eat.

Urban Farming in Singapore Has Moved Into A New, High-Tech Phase

As urban farming becomes more widespread, enthusiasts are coming up with new methods to grow edibles

JUN 3, 2017, 5:00 AM SGT

In community gardens found in housing estates, schools and even offices, urban farms are taking root in Singapore.

Such farms are not ornamental gardens. Instead, gardeners plant vegetables and fruit such as cabbage, basil and lime to eat.

Urban farms have always been popular with gardeners in Singapore, especially those who volunteer at neighbourhood community gardens.

The National Parks Board's popular Community In Bloom programme - a nationwide gardening initiative which started in 2005 - has more than 1,000 community gardening groups today. About 80 per cent of the groups in Housing Board estates grow edibles in their community gardens.

But urban farming has become more high-tech and, well, urban.

Urban farmers have started growing food in restaurants and taken over unused rooftop carpark spaces to set up garden plots.

Three urban farms stand out for their ingenuity.

The first is by a group of engineering students who have combined two aquaponics methods to get a larger harvest with more variety.

The second is by a businessman who used to sell raw materials for pesticides. He has invented a "growing tower" that does away with chemicals.

The last and most photogenic is by architecture practice Woha, which started an edible garden on the rooftop of its Hongkong Street shophouse office.

The gardening enthusiasts in the office have designed a photogenic farm, filled with lush greenery and decorated with stylish outdoor furniture.

Staff harvest vegetables and herbs such as kangkong and lemongrass to put in their salads or cook for office parties.

The Straits Times checks out these three urban farms.

PRETTY, FUNCTIONAL OFFICE ROOFTOP

Architecture practice Woha has a 2,100 sq ft organic urban farm on its rooftop, which is tended to by the firm’s gardening club, headed by Mr Jonathan Choe. ST PHOTO: LIM SIN THAI

When it comes to starting an urban farm, creating a good-looking set-up isn't usually top on the to-do list.

But for Woha, a home-grown award-winning architecture practice known for working greenery into its buildings, such as Parkroyal on Pickering hotel, urban farms can be useful and pretty.

The firm used the rooftop of its Hongkong Street office shophouse as a test bed for a 2,100 sq ft organic urban farm with more than 100 species of edible plants, including kangkong, basil, pandan, dill and bittergourd, which are shared among the staff.

Other than providing food, it is also a scenic place for staff to relax and destress, even if they are not interested in gardening.

The project, which cost $50,000, was completed last month.

Two rows of aquaponics planter beds, brimming with edible greens, are housed in sustainably treated pine wood boxes. The heights of these boxes have been designed so that gardeners need not bend over or squat when tending to the plants.

Behind these planters is a metal frame that is fitted with more planter boxes placed at different heights.

Flowering vines such as passionfruit and vanilla twine and creep up the metal frame. Some have even extended themselves across the wires overhead.

When more of these vines grow to maturity, they will create a canopy that will provide some shade in the open-air area.

Other highlights include an aquaponics system, which consists of a tilapia fish pond and a sloped planter bed. The system has water running through custom-made stainless steel water spouts. Across a short landing of wooden steps is a serene pond, centred by a tall kaffir lime tree.

Outdoor tables and chairs have been put in so that Woha's staff can pop up to the farm for a break.

Members of the firm's gardening club gather every Friday and spend about an hour tending to the plants.

A gardening workstation for potting and propagation and a large tank that collects rainwater to water the plants are kept out of sight at the back of this urban farm showpiece. The office also makes its own compost from food scraps.

Architectural designer Jonathan Choe, 28, who is the head of the gardening club, says they are looking to rear chickens there too.

He was part of the core team, including Woha founders Wong Mun Summ and Richard Hassell, that designed and built the farm.

He says: "We're not a commercial farm, where we grow vegetables just for food. It's also a beautiful sky garden, which the staff can enjoy."

USING WASTE TO GROW FOOD

Associate professor Lee Kim Seng (front) and the students behind the project (from left) – Mr Lim Zi Xiang, 35, Mr Kibria Shah, 31, and Ms Boo Jia Yan, 23. PHOTO: DIOS VINCOY JR FOR THE STRAITS TIMES

In a corner of Eng Kong Cheng Soon community garden in Lorong Kismis stands an industrial-looking set-up that contrasts sharply with the thriving greens in the soil.

A fish tank, filled with black African tilapia, is connected to long grey pipes which have cut-out holes in them. The seedlings of leafy vegetables are planted in net pots placed in these holes. Their roots dangle in the pipes and absorb the nutrient-rich water flowing through.

Above the fish tank is a container filled with clay pellets. Edible plants grow here, watered by the fish tank too.

The entire set-up is shaded by a plastic canopy that lets sunlight in, but keeps rain out.

This hybrid aquaponics system has yielded about 6kg of vegetables, such as butterhead lettuce, spring onion and Chinese cabbage, in the last two months.

The bountiful harvest is the result of a final-year project by three engineering students at the National University of Singapore (NUS).

The students built the system from scraps they found in their school's workshops. It took a few months to design and construct the 251 sq ft system, which is about the size of a room in an HDB flat.

Aquaponics combines aquaculture, the raising of edible fish, with hydroponics, growing vegetables without soil.

There are three ways to set up an aquaponics system, though common elements include having a fish tank and a soil-free plant bed. Both fish and plants are cultivated in one system. The fish waste provides organic fertiliser for the plants and the plants filter the water for the fish.

The students kept these basic features and combined two aquaponics methods - media-filled beds and Nutrient Film Technique - into one system, allowing them to grow a greater variety of plants.

The media-filled containers are good for growing plants such as tomato, brinjal and chilli. These have long stems that are kept sturdy by the clay pellets.

Leafy vegetables, which have shorter stems and long roots, are better suited for the Nutrient Film Technique - grown in net pots.

The fish can also be eaten once they are fully grown. The set-up is fully automated so they have to check in only once a week.

The students decided to work out of the community garden as they would be among seasoned gardeners. Ms Boo Jia Yan, 23, says: "There was a lot of experimentation and we had little knowledge of farming. Here, we were able to get advice about what could be improved."

They have plans to fit in high-tech features such as solar panels, which can generate electricity to power the system and install a device that allows for remote monitoring.

The set-up has attracted interest from two home owners.

Associate professor Lee Kim Seng of NUS' mechanical engineering department, who supervised the project, hopes more people will take on urban farming. "It's a very easy set-up. Why not utilise the waste to grow something good?"

VEGGIES FROM ON HIGH

Organic farming company Citiponics, run by Mr Teo Hwa Kok and Madam Jenny Toh (both above) operates 164 “growing towers” covered in leafy green vegetables, on a carpark rooftop. ST PHOTO: JAMIE KOH

At a multi-storey carpark rooftop in Kang Ching Road, 164 "growing towers" covered in leafy green vegetables rise to the sky.

Standing at 1.8m tall and lined up next to one another, these gardening systems are the result of years of research and development by Mr Teo Hwa Kok, 55, chairman of organic farming company Citiponics.

They have been used to produce about 25 types of vegetables and herbs, such as butterhead lettuce, spinach, dill, kailan, sweet basil and mizuna, a member of the mustard family.

At the base of each tower is a tank filled with water and nutrients. The mixture is pumped up to the top of each tower and flows down by gravity through a series of seven pipes arranged in a zig-zag manner.

The pipes have holes cut into them, creating pockets. Tiny clay pebbles, which have been cut to a specific size, fill these pockets. Seeds are placed among the pebbles, which is the growing medium for the plants.

As the water is constantly in motion, mosquitoes cannot breed. Also, no pesticides are used.

This is an improvement over some traditional hydroponics systems, which use water as a growing medium. This means that water can be stagnant in some parts.

Mr Teo says his version is lighter as it uses less water and can be built to any height.

The produce, which is harvested by volunteers from a nearby Residents' Committee centre, is given free to needy residents in Taman Jurong.

Mr Teo has been involved in the farming business for a long time, though he was not always a farmer. The Malaysian moved to Singapore in 1987 to work for a pesticide company. He quit in 1993 and set up his own venture selling raw materials used to make pesticides.

But as he read more reports about pesticides being misused and affecting food safety, he started to look into organic farming.

"It gave me an uncomfortable feeling so I decided to look into other ways to grow plants."

In 2001, he set up a 3ha organic farm in Malaysia, growing vegetables in soil. It did not take off and he gave it up about two years later.

He calls it a "very expensive experience" as consumers were not ready to pay high prices for pesticide-free vegetables then.

About seven years ago, he decided to try organic farming again and came up with the prototype for the growing towers.

He operates Citiponics with the help of Madam Jenny Toh, 55, who used to work in his pesticides business.

Citiponics has taken its growing towers to China and Malaysia.

On average, each growing tower costs about $4,800 and Mr Teo says it can last 20 years. A harvest from one tower can weigh between 5 and 10kg, depending on what vegetable is grown.

For his next green project, he wants to look into making pesticide-free feed for chicken and fish.

"Maybe one day, we can reduce the use of pesticides. Until then, we have to keep pushing ourselves to improve the safety of our food."

The Non-Profit Urban Roots Has Broken Ground For Its First Planting This Spring

There are big plans for that little bit of turned-over urban ground. For the people behind London’s first not-for-profit organic urban farm, it’s a big step back to the community’s agrarian roots and using empty spaces to produce food.

The Non-Profit Urban Roots Has Broken Ground For Its First Planting This Spring

By Jane Sims, The London Free Press

Tuesday, May 30, 2017 | 7:40:25 EDT AM

Cars and trucks speed down the hill along Highbury Avenue, past the transmission towers and a former horse pasture just north of the Thames River.

It would be simple enough to miss seeing the newly tilled patch of earth in the middle of an open green field that used to be horse pasture.

There are big plans for that little bit of turned-over urban ground. For the people behind London’s first not-for-profit organic urban farm, it’s a big step back to the community’s agrarian roots and using empty spaces to produce food.

Urban Roots, an organization slowly, steadily growing in momentum since its incorporation six months ago, has leased one hectare of land with the goal of a first planting and harvest this year.

This is a much different project than local community gardens. The goal is a sustainable, working farm that would supply produce to charities and neighbourhoods that have difficulty finding good quality fresh produce.

And because it is different, it has challenged municipal law-makers already working on an urban agricultural strategy.

“London, right now is focusing on its urban agricultural policy so they’re working to establish that, but it’s not in place yet,” said Heather Bracken, one of the group’s founding board members.

“So, we’ve had lots of conversations with the city. They’ve been great with taking our phone calls and with helping to guide us, but it’s still kind of an unknown.”

The city, she said, “has never encountered a project like this.” The policy is supposed to be ready by summer’s end.

One of the hurdles, for example, is the need for soil testing, not something that is necessary if you want to put a few tomato plants in your backyard.

“We’re the first of our kind. It’s a unique project for this area so it’s hard for all involved, the city and us, to really know the best way forward and to make sure we have to do it properly,” Bracken said.

But there are inspirations for their plan.

The group has made a couple of visits to the successful urban farms in the blighted areas of Detroit, part of the Michigan Urban Farming Initiative (MIUFI), some that strictly donate produce to the needy and other for-profit enterprises.

Graham Bracken, another founder of the London project and Heather’s husband, said they want to take the best of those models and “mash them all together.”

“There’s a lot of enthusiasm we’ve been picking up from people who have green thumbs and are involved in agriculture in one way or another, be it the food forests or the community gardens,” he said.

“A lot of people have been asking us, ‘Why did it take so long for it to happen?’ From that we get the sense that London is ready.”

Also needed was some added agricultural expertise. Of the four founding board members, only one, Richie Bloomfield, an accounting instructor at the Ivey School of Business, grew up on an organic farm. Social services veteran Jeremy Horrell, founder of the Forest City family project, “has an impressive backyard garden.”

Heather Bracken is a criminal defence lawyer. And Graham Bracken is an environmental philosophy writer.

But all of them agree there are food deserts in the city that could produce food.

The goal for this season is to get seeds in the ground, build a hoop-house — a portable greenhouse structure — and have a harvest to show “what we can do within the boundaries of the city,” Heather Bracken said.

Then, they want to expand the project to more locations to include training in how to grow and harvest your own food, plus cooking and canning sessions.

Urban Roots already has established relationships with Youth Opportunities Unlimited and Goodwill Industries.

The group has applied for a series of grants, but also has a GoFundMe campaign at www.gofundme.com/urban-roots-london, with the hopes of raising $7,000. So far about $1,700 has been raised.

jsims@postmedia.com

Downtown Victoria Condo Project Offers ‘New Ethos’ In Urban Living

The Wade features an urban rooftop garden space and what is believed to be the largest centre courtyard for condos in Victoria. Courtesy ten-fold projects

Downtown Victoria Condo Project Offers ‘New Ethos’ In Urban Living

The Wade is being constructed on site of former medical building at Cook and Johnson streets

- Thu Jun 1st, 2017 11:30am

- BUSINESSLOCAL BUSINESS

Tim Collins/News staff

The Wade is a low-rise, four-storey development in the works for the corner of Cook and Johnson streets, and according to the developers, it’s more than just another condo development.

According to developer Max Tomaszewski, it’s the expression of an ethos based upon environmental sustainability and a higher quality of life for its residents.

“If you’re going to spend 14 hours a day in a place, it should be a place that does more than provide shelter. You want a home that improves your health and quality of life,” he said.

Tomaszewski and his partner, David Price of ten-fold projects, have been building to Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standards for 15 years, but The Wade’s design and features are particularly rewarding.

The 102-unit, two-building development reflects the partners’ belief that real estate construction is moving toward a wellness orientation by incorporating a series of features not ordinarily found in a project of this kind, Tomaszewski said.

For example, each unit is assigned not only the standard parking spot and storage locker, but a four-by-eight-foot rooftop garden plot as part of an urban farm concept, complete with an apiary to aid in pollination.

The municipal water supply will receive additional filtration and the centre courtyard, billed as the largest of any condo in Victoria, will be home to an orchard.

The building is designed to minimize the background noise of the city. Another significant aspect of The Wade is the price point at which they’ve entered Victoria’s condo market. Units are priced between $260,000 and $300,000, a cost made possible, said Tomaszeweski, by savings realized through utilizing the existing “bones” of the medical arts building, upon whose footprint The Wade will be built.

The development is expected to be ready for occupancy by Christmas 2018.

More information is available at thewade.ca.

editor@vicnews.com

London Fights Urban Agriculture’s Peskiest Pest: Red Tape

London Fights Urban Agriculture’s Peskiest Pest: Red Tape

Urban farms offer cities a multitude of benefits, but municipal bylaws have long hindered them. London councillors are hoping to change that with a new strategy

Published on May 25, 2017

Urban farms like this one in Toronto can provide city-dwellers with fresh produce and can create new jobs. (Karen Stintz/Creative Commons)

by Mary Baxter

They wanted to grow food in the city and supply small local processors and soup kitchens with fresh vegetables — but when four would-be urban farmers in London found an ideal stretch of unoccupied land in the east end, the city told them they couldn’t lease it.

“We were literally not allowed to bid on that land because we were not going to develop it into houses,” says Richie Bloomfield, co-owner of Urban Roots London, the farming outfit in need of farmland. “That was kind of shocking to us.”

Urban agriculture is gaining popularity fast, but for farmers just getting started, often the biggest challenge isn’t learning how to till soil or keep pests at bay — rather, it’s the tangle of municipal rules and bylaws that either don’t take farming into account or actively discourage it.

But a new and nearly finalized urban agriculture strategy in London should make things easier, proponents say. According to Leif Maitland, the local planner spearheading the strategy, it’ll land on councillors’ desks by the end of the summer.

Supporters tout the benefits of urban farming: It makes fresh produce available to city-dwellers who might otherwise have trouble finding it, and it creates jobs, too. It can even help the environment, creating habitat for pollinators and reducing the distance food has to be trucked.

London’s strategy may not be the first in Ontario, but its inclusion of processing, distribution, food waste management, and education — all under the umbrella of urban agriculture — is unique.

Some of the proposed ideas, like building community gardens and growing fruit trees on public property, already exist in the city. Others, like a proposed backyard chicken pilot, have a long way to go before implementation. There’s also talk of establishing more farmers markets; creating hubs for sharing tools, supplies, and information; and building school gardens and community kitchens.

“We really wanted this strategy to inspire action, and that’s what the city wanted too,” says Lauren Baker, a consultant on the project and a former policy specialist with the Toronto Food Policy Council, a subcommittee of the city’s health board.

One of the biggest challenges will be putting the strategy to work — which will require participation from the municipal government and the broader community. In London, Maitland says, it’s not clear who will take the leading role.

“Maybe we’ll be enabling community groups, maybe we’ll be partnering with them,” he says. “Maybe we just need to change our bylaws to be as accommodating as possible, and then get out of the way and let people do what they want to do.”

Maitland says he’s familiar with the difficulties Urban Roots ran into searching for land. The city does rent to large-scale farmers who grow, for example, soybeans and corn, which can thrive even in poor soil. But the land is designated for other purposes, such as residential or commercial development, so it’s unsuitable for organic farming ventures that need to invest in long-term soil improvements.

An Inside View of Hong Kong’s Hidden Rooftop Farms

An Inside View of Hong Kong’s Hidden Rooftop Farms

Born out of a fear of contaminated foods, the city’s budding interest in high-altitude gardening may help heal an increasingly fractured – and ageing – society.

- By David Robson

17 May 2017

A butterfly perching on a lettuce leaf is not normally a cause for marvel. But I am standing on the roof the Bank of America Tower, a 39-floor building in the heart of Hong Kong’s busiest district, to see one of its highest farms. The butterfly must have flown across miles of tower blocks to reach this small oasis amidst the concrete desert.

“You just plant it out and nature comes and enjoys it,” says Andrew Tsui. We are joined by Michelle Hong and Pol Fabrega, who together lead Rooftop Republic, a social enterprise that aims to turn the city’s dizzying skyline green.