Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

From Shipping Container Farm, Casper, Wyo. Pastor and Hydroponic Lettuce Grower Preaches Local

From Shipping Container Farm, Casper, Wyo. Pastor and Hydroponic Lettuce Grower Preaches Local

March 13, 2017 | Trish Popovitch

Matt Powell opens the door to his hydroponic lettuce farm, housed in a used refrigerated storage container on the corner of his Casper, Wyoming property, and the Marriage of Figaro fills the air.

“My little Mp3 there is loaded up with Mozart and Bach. The study I heard said they tested growing plants in three sound proof environments. They had classical in one, death metal in another and silence in a third. Classical did the best, death metal did the second best,” laughs Powell explaining how his fresh hyperlocal greens are grown with the aid of some classic tunes as they stay cool in their farm-in-a-box environment.

The enclosed vertical farm, Skyline Gardens, came with the hydroponics already in place from Boston-based Freight Farms. This made it a little easier for Pastor Matt Powell, former computer salesman and current professional theologian, to find his way to a sustainable side business in an area in need of sustainable businesses. Using filtered water, nutrients, red and blue grow lights and of course, classical music, Powell will produce, at capacity, approximately 500 heads of fresh greens for the people of Casper every week. Business is growing steadily and a few harvests have already occurred.

Each variety of lettuce, Swiss chard and culinary herbs grows in isolation in one of the easy to remove and handle vertical growing towers. Powell labels the towers with dry erase marker to keep track of varieties, planting time and harvest requirements. As Powell explains, shipping container farms are ideally suited to the short growing season and temperamental weather of the Equality State. “It’s an enterprise that’s really custom suited to this area and just the lifestyle around here. People have land and it’s fairly easy to put one of these boxes down,” says Powell.

The company is still in its infancy with just six months under its belt. Most of that time was spent training in hydroponics, learning the equipment and realizing the substantial amount of legwork and marketing even the most tasty lettuce line needs to grow. “There is the barrier to entry: it’s expensive. And it’s definitely a learning curve,” says Powell. “You’ve got to be a problem solver and you got to be flexible and willing to learn. There’s a lot to learn on the farming end of it and there’s a lot to learn on the marketing end of it.”

Freight Farms uses discarded and retired refrigerated storage containers to build their hydro farms. Powell’s was the first one they sent to Wyoming so they had to add a wind barrier to the outside of the fan so it wouldn’t be pulled off or damaged by the high winds. The container ships out of Boston but the ZipGrow vertical hydroponic towers inside come from the folks at Bright Agrotech in Laramie, another indoor agriculture-focused Wyoming company.

Skyline Gardens will produce approximately 500 heads of lettuce per week at capacity.

Skyline is almost at profit level on the month to month books, but Powell predicts three years at this rate of growth to pay startup costs back in full. Self-funded, Powell realizes the wariness of banks, especially in a place like Wyoming where sustainable agriculture is still finding its feet, to fund container farms and similar new social enterprise style businesses.

Powell’s background in sales has certainly aided him in selling the idea of hyperlocal lettuce to Casper’s farmers’ market attendees as well as a few area restaurants. Although some early leads grew cold due to, in Powell’s assessment, the difference in price between his product and other wholesalers. “A lot of them want me to meet the price points of [their current suppliers] but I always say it’s a whole different product. When you have to deal with corporate offices out of state…that always makes it harder, so I’m working on that. I mean direct sales has a lot to be said for it. I get the whole profit to myself. I can control the way and time that I sell it.”

Powell has several direct sales customers who buy CSA style as well as his wholesale contracts. He also sells through a local aggregation group, Fresh Foods Wyoming, which takes his produce to the farmers market for him. Deliveries have proven the most time consuming aspect of the business so far and for now Powell wants to concentrate on solidifying his customer base with no plans to expand.

“Right now I think this is enough for me. I have my main job and I’m not planning on leaving that any time soon. Even now, in the startup phase, the time commitment is substantial,” says Powell.

As the ‘grow local’ and ‘sustainable’ concepts continue to build traction in Wyoming, Powell says he’s not worried about a crowded market just yet. “I’m not too worried about competition,” says Powell as he explains how his one container farm could supply a single local restaurant completely and exclusively. “There’s plenty of room in town for competition.”

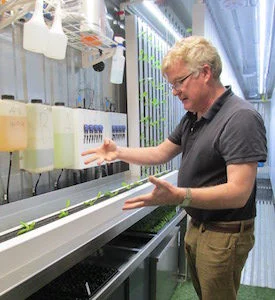

Pastor Matt Powell, the owner of Casper, Wyo.-based Skyline Gardens. Photo courtesy of Skyline Gardens

Newbean Capital and Local Roots Jointly Authored A White Paper Entitled ‘Indoor Crop Production

Newbean Capital and Local Roots jointly authored a white paper entitled ‘Indoor Crop Production: Feeding the Future’ which can be downloaded in full below by entering your name and email address. The paper was launched at the 3rd Indoor Ag-Con on March 31, 2015

Livewell Northwest Colorado: Bring Growing Back Home

Livewell Northwest Colorado: Bring Growing Back Home

Andy Kennedy/For Steamboat Today

Saturday, March 11, 2017

In a TEDx Mile High Talk, former three-time Olympian and health expert Jeff Olson described the call of duty during World War II, when Americans bonded together to grow more than 40 percent of the country’s fruits and vegetables in victory gardens. The premise was that larger agriculture ventures could go toward feeding our troops overseas.

But, when the war was over, the gardens withered, and during the next two decades, when the American family working-dynamic began to shift, there was another more toward agricultural imperialism. This imperialism birthed a larger global agriculture, as the U.S. government emphasized to its small farmers to “get big or get out,” for high-production and low-margin growing.

Olson warned that modern “industrialized food is a tragedy of human health, an irony of ecology and a paradox of economics.”

Olson elaborated that the solution to this terrible trifecta is the future of “closed-environment agriculture,” or greenhouses with a vertical twist.

Pioneered by the Dutch and now adopted by most industrialized nations — including 2.8 million acres of greenhouses in China — greenhouse growing is, indeed, feeding the world, and sadly, the U.S. is dead last in this effort. We used to be a net exporter of fruits and vegetables, and we are now a net importer of produce.

While greenhouses can be a viable solution, a better solution could be indoor vertical growing — a marriage of Jetson-like food technology with design wizardry of Steve Jobs.

We stand at the convergence of humanities and technology, and vertical aeroponics serves as nature with aerodynamic design. Imagine 43,000 square feet — about an acre — of your favorite greens. Vertical aeroponics can do it in 4,000 square feet. That’s 90 percent less space, with 90 percent less water, giving three times the nutrient density in the plant. Used by NASA and studied by universities around the world, vertical growing has proven efficient time and again.

I recently traveled to Florida to see the start of this revolution at Living Towers Farm, just north of Orlando. For more than six years, Jan Young’s organization has been growing “beyond organic” food for those in need, teaching the techniques of vertical growing to students and in-home gardeners and selling quality food that “doesn’t have to cost the Earth or have a negative impact on it.”

Even though Florida has the weather for outdoor gardening, it does not have the soil for it. Growing vertically yields more and healthier plants. Young’s eggplants, for instance, yield 8 to 10 fruits on a regular basis — about 30 percent more yield than traditional gardening.

Seeing the vision of Living Towers in person and pondering the economics of vertical growing spins my imagination to what this could mean for a local economy. For example, an acre of commodity corn earns a farmer $1,200; an acre of traditionally grown, organic food earns $12,000; and an acre of vertical aeroponics earns a quarter of a million dollars in revenue for one harvest, according to Olson.

Bringing the concept of Victory Gardens full circle, Olson has teamed up with an organization called Veterans to Farmers, which turns protectors into providers with an urban agricultural training program, creating “agropreneurs.” One of the program’s graduates launched the first vertical growing farm on the Front Range that sold out within a year of production, selling produce to fine dining restaurants on the Front Range.

“People are hungry for beautiful food,” Olson said.

Despite being known as an agricultural state, 97 percent of Colorado’s leafy greens are imported from thousands of miles away. With only a 25 percent increase in Colorado-grown food shift, we’d see 31,000 new jobs, generating more than $1 billion in new wages.

In my own home, we have two commercialized, state-of-the-art vertical growing systems, as do many other friends and peers in town — the Tower Garden has been around six years and is fairly well-known by now as an in-home solution to one of the shortest growing seasons on the planet.

However, it’s the larger installations that now inspire me. The vertical farms popping up around the country are something I would like to emulate. For several years, I have been inspired by the O’Hare Airport installation — more than 100 vertical towers in terminal D that outgrew their mission to feed the restaurants so quickly, they now offer a farmers market for travelers, as well.

I have brought this inspiration to several local nonprofits to start working on a project I hope will soon be growing local food on a larger scale, both for families in need and for those who want fresh produce. For more information, contact Andy Kennedy at andyjkennedy@gmail.com.

To view Jeff Olson’s full TEDx Talk, visit youtube/ttvIeugcigk.

Andy Kennedy a member of the Northwest Colorado Food Coalition

A Staten Island Urban Farmer - A 26-Year-Old Farmer Grows 50 Types of Produce In The Courtyard Of A New Rental Complex

Zaro Bates operates and lives on a 5,000-square-foot farm on Staten Island, which may make her the city’s only commercial farmer-in-residence

A Staten Island Urban Farmer

A 26-Year-Old Farmer Grows 50 Types of Produce In The Courtyard Of A New Rental Complex

MARCH 10, 2017

Zaro Bates operates and lives on a 5,000-square-foot farm on Staten Island, which may make her the city’s only commercial farmer-in-residence. But instead of a shingled farmhouse surrounded by acres of fields, Ms. Bates lives in a second-floor studio in a midrise apartment complex built on the site of a former naval base overlooking New York Bay.

The farm itself sits in a courtyard between two buildings at Urby, a development with 571 rental apartments that opened in Stapleton last year. Ms. Bates draws a modest salary and gets free housing, which sounds like a good deal until you discover how much work she has to put in.

The 26-year-old oversees a weekly farmstand on the complex premises from May through November and donates to food banks. In her repertory? Some 50 types of produce — greens, summer vegetables, flowers, herbs and roots. She does this with help from her business partner and husband, Asher Landes, 29.

Let the doubters doubt.

“A lot of people instinctively call it a garden, but we really try to manage it for a commercial market,” Ms. Bates said. “It’s funny that people have different kinds of notions of what a farm is. Some people think it needs to have animals, that it needs to have acreage. We intensively crop this space so that we can produce for market, and that’s why we call it a farm.”

Farming, of course, is a New York tradition. In the late 1800s, loam and livestock were predominant north of Central Park and in what is now the East 50s. In “Win-Win Ecology,” Michael L. Rosenzweig argues that ecological science has rooted itself in the common ground of development and conservation: the use of rich natural resources in places where we work and live.

Farms like Ms. Bates’s, in addition to more traditional farmland, have been around for quite some time. Thomas Whitlow, an associate professor of horticulture who specializes in urban plants at Cornell University, Ms. Bates’s alma mater, said that in the 1940s some 40 percent of fresh market produce in New York was grown in victory gardens.

“Certainly, urban populations in general are very adaptable as conditions change,” Dr. Whitlow said. “They can change within the space of a year. Just a hundred years ago we were almost a hunter-gatherer society and did indeed have farming in major metropolitan areas.”

Ms. Bates had hardly seen farmland as a child. Her parents, who moved to Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, in the early 1990s, rarely took the family upstate. They had the backyard of their home, but no green thumbs between them. The yard was a play space.

After graduating from the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell, where she studied developmental sociology, Ms. Bates volunteered as a groundskeeper at the Kripalu Center for Yoga and Health in Stockbridge, Mass.

“That was the first time that I drove a tractor, did wood chipping, shoveled heaps of snow in the Berkshires winter, then planted in the springtime and just worked outside with a team of people through the seasons,” she said. “That was my first experience with that type of work and really falling in love with that.”

Afterward she intended to travel, maybe visit South America. Her plans were postponed by an apprenticeship at Brooklyn Grange, a rooftop and urban farming consultancy group, where Ms. Bates farmed under the tutelage of the chief operating officer, Gwen Schantz.

“We love designing and installing green spaces for clients, but it’s equally exciting to see others taking this work up, especially young, savvy farmers like Zaro,” Ms. Schantz said.

The group played an advisory role in two fundamental aspects of Ms. Bates’s life. First by helping her start her own consultancy, Empress Green, and by providing the pretenses under which she met Mr. Landes. The two now live at Urby and work on the farm during the spring, summer and autumn growing seasons, traveling abroad in the winter.

The couple had consulted for Ironstate Development, the developer of Urby, ahead of the farm project, and are now consulting with it on a future residential farm project in New Jersey. While Ms. Bates is the affable and gregarious face of Empress Green, Mr. Landes caters to the bees in 20 colorful hand-painted hives on the roofs at the Stapleton development. By his estimate, there are nearly two million bees, and each hive produces 50 to 80 pounds of honey a season.

“In the spring this will be brimming with hemlock and filled with flowers and all the trees will be filled with flowers,” Mr. Landes said of the farm. The bees will “be able to fly about nine miles to find good food. You stand up here and it’s just like a highway. It’s amazing.”

The honey, herbs and produce from the farm are sold at a stand for the community.

“What we did was similar to other farmers’ markets in the city,” Ms. Bates said. “But because it was enclosed in a space that invites hanging out for a while, we really invited people to make it more of a Saturday afternoon activity. That was not just for Urby residents, but also anyone from the general public.”

Ms. Bates and Mr. Landes try to plant according to requests from local residents. The proceeds go to the couple’s company, supplementing the annual salary they each receive from Urby. (Urby and Ms. Bates declined to disclose the amount.) They also host workshops and a book club.

“The priority is to residents,” Ms. Bates said, “but also to build community.”

She has considered offering a community-supported agricultural association in which residents enroll to receive a regular supply of produce, but that would limit her client base. Her current all-are-welcome approach has Ms. Bates seeking other methods of distribution because, while there is a steady growth in demand, she produces more than she can sell even while supporting Urby’s communal kitchen, where Urby’s chef-in-residence hosts classes for tenants. Ideas include a subscription-based meal delivery service.

Even so, she is focused on expansion. Urby is developing another farm plot in the same complex, where now there is just a slab of concrete. Ms. Bates also hopes to offer more educational opportunities as the farm’s output increases.

Residents “want to contribute in some way, or they just feel like their kids should know what a tomato looks like growing in the ground,” she said. “A lot of New Yorkers don’t grow up seeing that.”

A version of this article appears in print on March 12, 2017, on Page RE1 of the New York edition with the headline: The Farm in the Courtyard.

Zaro Bates and her husband, Asher Landes, farm land between two apartment buildings in Stapleton, Staten Island. They live at the complex, too.

Credit: Emon Hassan for The New York Times

The farm, seen from a rooftop.

Credit: Emon Hassan for The New York Times

The sunflowers of last July.

Credit: Emon Hassan for The New York Times

Letters To A Young Farmer: Stone Barns Center Releases Its First Book

Today, Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture released Letters to a Young Farmer, a book which compiles insight from some of the most influential farmers, writers, and leaders in the food system in an anthology of essays and letters.

Letters To A Young Farmer: Stone Barns Center Releases Its First Book

Today, Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture released Letters to a Young Farmer, a book which compiles insight from some of the most influential farmers, writers, and leaders in the food system in an anthology of essays and letters.

The United States is on the cusp of the largest retirement of farmers in U.S. history, with more farmers over the age of 75 than between the ages of 35 and 44. Letters to a Young Farmer aims to help beginning farmers succeed through advice and encouragement, while inspiring all who work in or care about the food system. Among the 36 contributors to the book are thought leaders Barbara Kingsolver, Bill McKibben, Michael Pollan, Dan Barber, Temple Grandin, Wendell Berry, Rick Bayless, and Marion Nestle. I was honored to contribute to the book as well!

Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture is a nonprofit sustainable agriculture organization with a mission to create a healthy and sustainable food system that benefits all. The organization trains farmers, educates food citizens, develops agroecological farming practices, and convenes changemakers through programs such as a Summer Institute for High School Students and a two-day Poultry School conference.

Food Tank spoke with Jill Isenbarger, CEO of Stone Barns Center, about Letters to a Young Farmer, the need to encourage young farmers, and hope in the future of the food system.

Isenbarger says “we created this book to give voice to farmers and illuminate the choices that can lead to a stronger future, for them and for all of us who eat. It reminds us that farming has always been a political act. These young farmers, who choose to farm rather than go into law or medicine or finance—they are taking a stand; they are expressing their commitment to the land, to their communities, to the food movement.”

Food Tank (FT): Why do young farmers need encouragement?

Jill Isenbarger (JI): Farmers are becoming an endangered species. The number of farms and farmers continues to shrink, and farmers are aging off of the land at an alarming rate. The average age of a farmer in the United States is 58.3 and climbing, and only six percent of farmers are under the age of 35.

Young farmers need encouragement because our society doesn’t value them the way they should be valued. “You’re just a farmer” is the common refrain. Barbara Kingsolver, Wendell Berry, and Bill McKibben all write about this in the book. We’ve also lost many agricultural traditions based on community, a common history of stewardship and hard work.

To support the kind of dignified labor and environmentally sound land stewardship that will help us create a more sustainable farming system, we simply may have to pay more for our food. According to the USDA, in 1960, Americans spent 17.5 percent of their income on food. By 2013, that had dropped to 9.9 percent. As a country, we’ve grown accustomed to cheap food—food that is not only inexpensive, but food that doesn’t taste good and isn’t good for us. Paying more for quality, nutritious food (and helping those of lesser means gain access to it), grown by farmers able to earn a living wage and provide health care to their workers—that would go a long way to helping raise us all up.

FT: What unique obstacles do young farmers face?

JI: Bill McKibben writes about surviving the “carbon binge,” and the challenges that a changing climate will bring to farmers who grow our food. Marry this with the challenges of finding affordable land to farm, paying off student loans, the dearth of start-up capital and a lack of regional agricultural infrastructure in some parts of the country, and you have a daunting set of obstacles that most young farmers face.

It is hopeful to note that H.R. 1060, the Young Farmer Success Act, a bipartisan bill sponsored by Rep. Joe Courtney (D-CT), Rep. Glenn Thompson (R-PA), and Rep. John Faso (R-NY), was reintroduced in the House of Representatives in February. This bill will help provide college loan relief to young farmers. So, some in Congress are paying attention, especially among them Rep. Chellie Pingree (D-ME), herself a contributor to our book.

FT: What are some of the most important areas for young farmers to focus their skills?

JI: One is soil health, the very foundation of sustainable agriculture. There’s a saying, “civilizations rise or fall on the health of soil.” Farming with nature is the key; farming that builds up soil, uses water wisely and with an eye on the future—we absolutely need more of this. Wes Jackson talks about this in his letter: “Ecological agriculture has the disciplines of ecology and evolutionary biology to call on, based on millions of years of emerging efficiencies such as those seen in nature’s prairie ecosystems.”

At Stone Barns Center, we focus on two aspects of building soil health: one is through farming, and we teach and experiment with agroecology. The other is the concept of creating what we call a farm-driven cuisine in America—catalyzing a culture of eating based on what ecosystems, including farms and their soils, need to be healthy and regenerative.

Young farmers need to focus not just on the practical skills to grow, harvest, and sell their products; they also need to focus on building strong connections to their communities, sharing their deep love of land and place, and helping people understand the value and importance of farming done well.

FT: Which letters inspired you the most?

JI: So many of the letters and essays are extraordinary and inspiring and deeply moving. They flow with humor and insight, gratitude and humility. I love the wry wit of Barbara Damrosch, Mary Berry, Bill McKibben, and Gary Nabhan, and the lyrical insights of Raj Patel and Barbara Kingsolver. I was drawn to Amy Halloran’s line, “Eating is hunting in nature for food.” It pulls you back to the bond that we need to have with the earth. It is primal. I appreciate Wendy Millet’s articulation of her “hundred years” value, the idea of taking a long-term perspective on economically and ecologically sustainable management.

FT: What were the most common themes you found in the letters?

JI: There are many overlapping ideas that ripple out in their own ways, but these are a few themes that arose in a number of the essays and letters:

- Bridging the gulf between nature and agriculture, between land conservation and food production—and finding the path toward to a more sustainable future.

- Renewing respect for farmers in a society that has taught children farming is a lowly occupation, and in a country that was founded by and largely composed of farmers until the mid-20th century.

- The changing nature of today’s young farmers, from generational—ones that inherited their roles and land—to the self-selected farmers who want to be agents of change.

FT: What have farmers’ reactions been to the book?

JI: “When are you putting together the next book? I want to write a piece.” This has been a heartening response. Sharing the stories about the people who grow our food and steward our lands and waters is powerful and important. Farmers are a hearty, optimistic, and determined breed. To have received their support and encouragement is a great honor and means that we are advancing our mission in an important and meaningful way.

Indoor Ag-Con Returns to Las Vegas to Discuss Farm Economics and New Technology Trends in Hydroponics, Aquaponics & Aeroponics

Indoor Ag-Con Returns to Las Vegas to Discuss Farm Economics and New Technology Trends in Hydroponics, Aquaponics & Aeroponics

Indoor Ag-Con – the indoor agriculture industry’s premier conference – will be returning to Las Vegas for the fifth year on May 3-4, 2017 to discuss the prospects for this increasingly important contributor to the global food supply chain.

LAS VEGAS, NV (PRWEB) MARCH 10, 2017

Indoor agriculture – growing crops using hydroponic, aquaponic and aeroponic techniques – has become popular as consumer demand for “local food” leads growers to add new farms in industrial and suburban areas across the country. Indoor Ag-Con – the industry’s premier conference – will be returning to Las Vegas for the fifth year on May 3-4, 2017 to discuss the prospects for this increasingly important contributor to the global food supply chain.

The two-day event will be held at the Las Vegas Convention Center, and is tailored toward corporate executives from the technology, investment, vertical farming, greenhouse growing, and food and beverage industries, along with hydroponic, aquaponic and aeroponic startups and urban farmers. It is unique in being crop-agnostic, covering crops from leafy greens and mushrooms to alternate proteins and legal cannabis. Participants will receive an exclusive hard copy of the newest edition in a popular white paper series, which is sponsored by Urban Crops and will focus on the US industry’s development.

The event will consist of keynotes from industry leaders and extended networking breaks, along with a 50+ booth exhibition hall. This already includes industry majors such as Certhon, Dosatron, DRAMM, Hort Americas, Philips Lighting, Priva, and Transcend Lighting. A new addition for 2017 is “lunch and learn” sessions covering practical topics such as health and safety. Confirmed speakers include executives from Argus Controls, Autogrow, Bright Agrotech, CropKing, Fresh Box Farms, Grobo, Intravision, Plenty, Priva, Shenandoah Farms and Village Farms among many others. “We’re expecting that the big themes for this year will be farm economics and the commercialization of newer technologies such as machine learning, and are excited to have gathered experts from across the world to speak. The entrepreneurs in our funding session have raised more than $50mn for their indoor farms in the past year alone, and one speaker is operating a 100k ft2 commercial controlled environment farm” commented Nicola Kerslake, founder of Newbean Capital, the event’s host.

Agriculture technology companies, suppliers and automation companies will have the chance to meet and mingle with leading vertical farmers and commercial greenhouse operators at a drinks party on the first evening of the event. Event sponsors include Autogrow, Urban Crops, Kennett Township, Freight Farms, Grodan, Joe Produce, Crop One Holdings and Grobo.

Beginning farmers, chefs and entrepreneurs can apply for passes to the event through the Nextbean program, which awards a limited number of complimentary passes to those who have been industry participants for less than two years. Applications are open through March 31, 2017 at Indoor Ag-Con’s website. The program is supported by Newbean Capital, the host of Indoor Ag-Con, and by Kennett Township, a leading indoor agriculture hub that produces half of the US’s mushrooms.

Indoor Ag-Con has also hosted events in Singapore, SG and New York, NY in the past year, and will host its first event in Dubai – in partnership with greenhouse major Pegasus Agriculture – in November 2017. Since it was founded in 2013, Indoor Ag-Con has captured an international audience and attracted some of the top names in the business. Events have welcomed nearly 2,000 participants from more than 20 countries.

Newbean Capital, the host of the conference, is a registered investment advisor; some of its clients or potential clients may participate in the conference. The Company is ably assisted in the event’s production by Rachelle Razon, Sarah Smith and Michael Nelson of Origin Event Planning, and by Michele Premone of Brede Allied.

5th Annual Indoor Ag-Con

Date – May 3-4, 2017

Place – South Hall, Las Vegas Convention Center, Las Vegas, NV

Exhibition Booths – available from $1,499 at indoor.ag

Registration – available from $399 at indoor.ag

Features – Two-day seminar, an exhibition hall, and after-party

For more information, please visit http://www.indoor.ag/lasvegas or call 775.623.7116

The Farm of The Future? (Video)

The Farm of The Future? (Video)

AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY

WASHINGTON, Feb. 28, 2017 -- There's a new trend in agriculture called vertical farming. As humans learned to farm, we arranged plants outside in horizontal fields, and invented irrigation and fertilizer to grow bumper crops. But with modern technology and farmers' cleverness, we can now stack those fields vertically, just as we stacked housing to make apartment buildings. Moving plants indoors has many benefits: Plants are not at the mercy of weather, less wilderness is cleared for farmland, and it's easier to control the runoff of fertilizer and pesticides. But the choice of lighting can make or break the cost of a vertical farm and affect how long it might take for urban agriculture to blossom. Watch the latest Reactions video here: https://youtu.be/rEw-VfFkUik.

Why Large-Scale Indoor Farms Will Be Crucial to Feed Our Fast Growing Cities

Why Large-Scale Indoor Farms Will Be Crucial to Feed Our Fast Growing Cities

SEB EGERTON-READ · MARCH 9, 2017

Technological innovations are enabling a new way of producing food transforming indoor environments into places where fruits and vegetables can be grown without soil, close to the city, with an extremely short supply chain, fully independent of weather fluctuations, while reducing demand on water and chemicals. One of the pioneers of the approach, New Jersey based Bowery, describe it as ‘post-organic’ farming, and momentum is growing behind the idea that a sizeable percentage of some of the fruits and vegetables of the future could be grown using this technique.

On the current path, the world population’s caloric demand will increase by 70%, while crop demand for human consumption and animal feed is expectedl rise by 100%. Meeting these needs with existing agricultural practices will require large areas of additional land, and will increase pressure on the earth’s soil, which has gradually been degraded losing a significant percentage of its nutritional capacity over the last 100-150 years. Meanwhile, the effects of climate change, realised through extreme weather patterns, threaten to negatively impact crop yields and disrupt food supply chains.

Urban agriculture in the form of aquaponics, where fish farming is combined with the growth of vegetables and a self-maintaining system is established has a long history, but the data monitoring and ability to control internal conditions provided by new technologies has enabled the further evolution of hydroponics.

Hydroponic farming involves growing produce in multi-storey warehouses without soil. Seeds are planted in a soil substitute and grown in nutrient-rich water, where water is recirculated, and temperature, salinity and humidity are monitored and controlled to maximise the yield. The method has a number of economic, environmental and social advantages. Here’s a pretty good initial list taken from SystemIQ’s Achieving Growth Within report:

- 90-95% reduction in water demand

- Fertilizer use reduced by 70%

- Use of herbicides and pesticides eliminated

- Food waste at the production stage minimized

- Growing space maximized

- Ability to grow throughout the year

- Shorter supply chain results in lower transport costs and related emissions

Reportedly 100+ times more productive on its land compared against traditional farming, Bowery is one of the most advanced movers in the sector. They’re far from alone, Japan’s Spread declared their initial plant profitable in 2013 and now have plans to open an automated plant that could increase their yield to 51,000 lettuce heads per day, and we’ve previously told the story of AeroFarms, another New Jersey based firm.

It’s also a highly efficient technique in terms of resource use. For example, only 5% of the fertilizer used on large fields is actually consumed by people, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s Growth Withinresearch, the rest of the nutritional value is waste across the value chain.

The new model doesn’t come without criticisms. Growing without soil means that there is little opportunity for regeneration or the development of an ecosystem that ‘feeds itself’, rather the method allows for the development of a large number of linear and separate processes in an ultra-efficient way.

Furthermore, there will always be concerns about the nature of the chemicals needed to grow plants in these conditions, and the types of seeds used. For their part, Bowery take pride in sourcing, “from partners who spend nearly a decade developing the ideal seed, rather than relying on GMOs”. When Circulate asked him about some of the potential trepidations, CEO Irving Fain was quick to highlight that the story of indoor farming is a healthy one, both for crops and people:

“Bowery grows its produce under LED lights that mimic the spectrum of the sun. By monitoring the growing process 24/7 and capturing data at each step, we give our crops exactly what they need and nothing more. Because we control the entire growing process from seed to store, our produce is the purest available – food you can truly feel good about eating”.

For Irving, who is already planning Bowery’s second farm, scale is the next challenge, “we plan to continue to build additional farms, keeping them all close to the point of consumption to deliver products at the height of freshness and flavor, and we hope to serve more cities throughout the country”.

Up front investment costs are a potential barrier, but there’s also an increasingly strong business case associated with indoor farming. Besides the growing number of innovators establishing businesses, SystemIQ’s research estimated that €45 billion of total investment between now and 2025 could create an economic reward across Europe of €50 billion by 2030 with key benefits including the freeing up of land space and reduced reliance upon fertilisers and pesticides.

Pair the potential economic opportunity with the demands expected by a fast-growing global population, and it’s easy to imagine a future where at least part of the food supplied to the world’s largest cities comes from indoor farms located inside the city limits.

West Coast Supply Issues Prompt More Demand At Indoor Farms

West Coast Supply Issues Prompt More Demand At Indoor Farms

By Ashley Nickle March 09, 2017 | 2:23 pm EST

Indoor farms are seeing increased demand as weather-related production issues in Arizona and California have affected the supply of leafy greens.

Rain has interrupted planting and harvesting in California throughout the season, and the Yuma, Ariz., deal is expected to finish earlier than previously thought after mildew proved to be a major problem.

With West Coast supplies tight, several indoor farms have reported increased interest from buyers.

New York, N.Y.-based BrightFarms, which has greenhouses in Illinois, Virginia and Pennsylvania, has seen retail orders rise in recent weeks.

“It has been impacting most of our customers pretty significantly and their availability on items like spinach and arugula and other baby greens items as well,” said Abby Prior, vice president of business development for BrightFarms.

“Because our crop cycles are relatively short, we have a lot of flexibility to be able to adapt on planting cycles relatively quickly,” Prior said. “That is really a daily and weekly process with our retailer partners, looking at their forecasted demand, and we can adapt our planting pretty much daily based on their needs.”

Prior said the company will likely be providing higher amounts of product at least through March as crops transition from Yuma to California.

Milan Kluko, CEO at New Buffalo, Mich.-based Green Spirit Farms, said his company has seen an uptick in interest in the last month due to the Western production problems. Green Spirit can only increase capacity at its New Buffalo location — it also has a farm in Detroit — about 20% due to space constraints, but it has been ramping up production as much as it can.

One of the large supermarkets with which Green Spirit works is ordering double what it did a few weeks ago, Kluko said.

Robert Colangelo, CEO of Portage, Ind.-based Green Sense Farms, said the company has been shifting production to meet higher demand. Green Sense grows micro greens, baby greens, herbs and lettuces but will produce about 30% more lettuce and less of other items to address customer needs.

Benjamin Kant, CEO of Chicago-based Metropolitan Farms, said it is hard to tell whether his company’s current strong demand is a direct result of the West Coast production issues because the company just completed its first full year in operation.

However, Kant said he has heard complaints about higher prices and lower quality of West Coast product.

Marc Oshima, chief marketing officer at Newark, N.J.-based AeroFarms, said demand has “absolutely” increased lately but noted overall interest has been high for a while.

“It’s not just recently,” Oshima said. “These are ongoing issues that have troubled the industry.”

All five of the indoor farms interviewed for this article have recently expanded or are expanding.

“The more we (as a country) see challenges in sourcing all of our produce from a relatively small area on the West Coast, farms like ours and companies like BrightFarms will continue to grow and will continue to gain relevance in the produce industry,” Prior said, “and we’re glad to be able to fill the gaps at times like these where retailers are struggling.”

Students Give Schurz Food Science Lab a Green Thumbs Up

Students Give Schurz Food Science Lab a Green Thumbs Up

Erica Gunderson | March 9, 2017 4:46 pm

Hydroponics farms are hot in Chicago, with new farms sprouting up all over the city. But finding experienced hydroponics workers can be tough, so a local chef decided it was time for Chicago to grow its own. His program in a Northwest Side high school offers students the chance to get their hands dirty – and wet – growing greens in a working hydroponics farm.

We visited Carl Schurz High School, where the seeds are being planted for the next generation of urban farmers.

TRANSCRIPT

Brandis Friedman: It all starts with a seed.

Every few days, students in Schurz High School’s Food Science Lab spread thousands of tiny arugula seeds across damp paper towels and slip them under grow lights. After another few days, the sprouts become a crop of microgreens, which are delicately harvested and brought to the Schurz cafeteria to be mixed into lunchtime salads.

Jaime GuerreroJaime Guerrero, Schurz Food Science Lab: The students right now love the idea of having fresh basil in their salads. They love the idea of microgreens because they add much flavor and diversity to what they’re already eating. And whether they realize it or not, they're adding so much nutrition to what their diets are, to what they eat in the cafeteria.

Friedman: Produce doesn’t get more local than that, and that’s exactly the way the Food Science Lab’s founder Jaime Guerrero likes it. The chef and marketing executive’s idea for a high school urban farming program started as a way to prove a restaurant concept.

Guerrero: The idea came from an urban farm restaurant concept that I had in my head. Through my alderman and other supporters in the community, Arts Alive, we came up with the idea of a proof of concept that would be within the area and we connected with Schurz high school.

Friedman: The farm began with two hydroponic grow towers in an old shop classroom. Guerrero recruited students to volunteer as his first farmers. Two years later, he says it’s the students who drive the program.

Guerrero: The input of the kids has been very essential. The products that we have evolved here were a combination of things that work in these environments and with these systems and what we’ve tried, but also the tastes of these students. Our plans were to integrate it further into the departments and the school itself. This year we’re integrated into three departments: environmental science, botany and engineering.

Friedman: Yields from the Food Lab are often large enough to allow the program to donate herbs and microgreens to a nearby food pantry. And like any farm, increasing yields is a constant focus –whether it’s by adjusting light or fertilizer, testing different grow media or developing a prototype for a rotating growing system. For senior Nathaniel Dejesus, working in the Food Lab has allowed him to apply some of the problem-solving techniques he’s learned in his pre-engineering classes.

Nathaniel DejesusNathaniel Dejesus, Schurz senior: We thought of a triangle system that would have different layers. It would be a mist system, it would have LEDs under the trays, so you can access it easier. There'll be a pipe coming through the middle so it can all recycle back to the reservoir.

Friedman: Elsewhere in the lab, senior Veronica Burgo is growing tomato plants in the Food Computer, an agriculture technology platform developed by MIT to determine and share optimal growing conditions.

Veronica Burgo, Schurz senior: There were some astronauts that went out into space and took some tomato seeds and they were kind enough to let us use two packs of their seeds. We have four samples in here at the current moment, and we're trying to compare them against what we have in some of our other systems, like our lettuce systems to see if anything changed within the genetics of the plant.

Friedman: Veronica draws a direct line between her work in the Food Lab and her future career ambitions.

Veronica BurgoBurgo: I’m aspiring to be a biochemist and a lot of what we do here is chemistry and biology, so I would love to be a part of an urban farming group in college.

Friedman: For now, the Food Lab is being kept alive by donations and small grants, but funding continues to be a challenge. That’s why Guerrero hopes to fold other disciplines, like business management and marketing, into the curriculum so that Food Lab students can sell their product to the community and put the profits back into the program.

Guerrero: What we tell these kids every day is come in here, learn, experience what we have and at least be a little inspired to learn about it. If we get you to be interested to do something, to be a farmer, an engineer, even better. I think that this program can be great in this community as we build it up, but also anywhere in the country.

Urban Vertical Farming Helps, Inspires, Grows The Green Wave

Urban Vertical Farming Helps, Inspires, Grows The Green Wave

By Eliza Grace | Thursday, March 9

Last week, I went to catch up with an old friend who graduated from Duke last spring. Dr. Spencer Ware, a major in Environmental Science, found his new job by researching urban gardens in the greater Raleigh/Durham area. He stumbled across a small but productive operation called Sweet Peas Urban Gardens. This haven, created by Tami Purdue, takes up an average size plot in the middle of a residential area that features a greenhouse, outdoor garden and a Crop Box. You may not recognize the term "Crop Box," as the concept is quite new. Sweet Peas is home to the fifth one ever created!

The Idea of the Crop Box originated when a few people realized how many empty shipping containers there were laying around. These large metal boxes take up space without a purpose. The solution proposed by Crop Box was to make these spaces into small vertical urban farms. From the ideas conception in 2012, the first model took two years to perfect. As of now, a fully-functioning, fully green Crop Box would cost you about $75,000. Purdue pointed out that the high cost is due to the 50 LED lights that Sweet Peas purchased to grow each layer of produce. LED lights are four times the price of fluorescents, but in the long run save electricity costs that would be needed to ventilate the heat produced by cheaper fluorescents.

The entire container comfortably hosts four layers of a variety of soil-free growing plots. The Crop Box could also feature soil, but Sweet Greens uses a hydroponic system instead, because, why use an unnecessary resource? Their soil-free (hydroponic) growing system uses only decomposable materials which are later composted, and so little water that Sweet Peas water bill went up only four to six dollars per month once the Crop Box was up and running.

The early adaptors of this new system have so-far found that the way to make the fastest profits is through growing micro-greens. Micro-greens have a growing cycle of only 10-14 days. They are packed with flavor, nutrients(up to 40 time higher levels of vital nutrients than their mature counterparts) and are part of a growing market. This means produce can be churned out in a quick and efficient manner. The system is also made more cost-effective and sustainable by thriving without the need of any chemical fertilizer inputs. The more difficult part has been finding the market to sell to.

Sweet Peas made their mark by starting at the local farmers market in Raleigh. Until recently, micro-greens have gone underutilized and under cultivated in the kitchen. However, with a growing trend towards eating healthy and local, people have started to recognize micro greens as a perfect garnish with lots of different flavors. Sweet Peas alone harvests a large variety. When I visited, Purdue and Spencer showed me varieties of wheatgrass, radish, broccoli, kale, cilantro and much more than was all soon to be harvested. The whole operation was diverse, concise and beautifully efficient in producing delicious organic micro-greens.

While the whole operation requires a large investment to get started, Sweet Peas Urban Garden made its money back in just two years. This includes the time it took to get Sweet Peas recognized as a supplier to the area. After spending time at the farmers market, local chefs caught on to the Sweet Peas mission and fell in love. These gourmet, farm-to-table chefs are the backbone of the micro-green business, a small but budding market in the N.C. triangle.

While the Crop Box also takes work to maintain, Purdue has found a lot of free help, and new friends, through using the website WWOOF (Worldwide Opportunities on Organic Farms), which lists farms worldwide where people are welcome to live for free in exchange for farm work. In addition to this money-saving tactic, Sweet Greens makes local deliveries by bicycle. Both of these methods are not only good for business, but good for the health and spirit of those running the business.

Because of the success Sweet Greens has seen, Purdue is considering investing in a second Crop Box. There is a possible deal in the works with Whole Foods that could launch their operation to a much larger scale, and even without Whole Foods the demand has still been continuously growing.

While a growing desire for fresh local foods exists, many urban areas continue to lack initiative. When exceptional people such as Purdue of Sweet Peas decide to take action and start a project, people notice. No matter how small the operation, a new trend can be created through a growing appetite and awareness for local, organic food. Every individual with any size plot of land has the power to grow their own food, and Sweet Peas is a larger symbol of that. If this small shipping container can be turned into a profitable farming project in two years, we should all spend more time thinking about the future possibilities of urban and vertical farming. People from around the world have traveled to Raleigh to see Sweet Peas Urban Farm and it’s Crop Box initiative. If their little box can serve as a model for the rest of the world, then no effort is too small to help innovate new models to feed an ever-growing population.

Many Thanks To Dr. Spencer Ware and Tami Purdue for welcoming me on their farm and talking to me about the project!

Eliza Grace is a Trinity junior. Her column, "the green wave" runs on alternate Thursdays.

Urban Crops Announces Corporate Name Change to Urban Crop Solutions

March 9th, 2017 11:16

Urban Crops Announces Corporate Name Change to Urban Crop Solutions

As of today Urban Crops will change its name to Urban Crop Solutions, highlighting the core of the company being a global turnkey solution provider in automated plant growth infrastructure and plant growth recipes. In alignment with the adoption of the new name Urban Crop Solutions has also launched a new website: urbancropsolutions.com.

“We are very excited about the introduction of our new company name and believe that the name Urban Crop Solutions allows us to better represent our business model, being an independent turnkey vertical farming solution provider with an extensive after sales model”, explains Maarten Vandecruys, co-founder and managing director of Urban Crop Solutions. “Being categorized as a solution provider better aligns with our philosophy and core values of delivering reliable and qualitative products and services” adds Frederic Bulcaen, co-founder and chairman of Urban Crop Solutions. “All our products and installations are engineered and manufactured to be industry-proof.”

We are very excited about the introduction of our new company name and believe that the name Urban Crop Solutions allows us to better represent our business model, being an independent turnkey vertical farming solution provider with an extensive after sales model.

Maarten Vandecruys, co-founder and managing director

Urban Crop Solutions with headquarters in Beveren-Leie (Waregem, Belgium), in the middle of the Western European vegetable industry and surrounded by international well-reputed machine building companies, develops since 2014 tailored plant growth installations. These systems are turnkey, robotized and able to be integrated in existing production facilities or food processing units. Urban Crop Solutions also has its own range of standard growth container products. Being a total solution provider Urban Crop Solutions can also supply seeds, substrates and nutrients for clients that have limited or no knowledge or experience with farming. Currently the company has a growing list of more than 180 varieties of crops that can be grown in closed environment vertical farms and that have been validated. These plant recipes (ranging from leafy greens, vegetables, medicinal plants to flowers) are developed specifically for indoor farming applications and sometimes exclusively for clients by its team of plant scientists. Urban Crop Solutions has started activities in Miami (Florida, US) in 2016 and expects to have an own subsidiary in Japan in Q2 2017.

Growing crops in a climate controlled multi-layer environment with own developed LED lights achieves shorter growth cycles, higher water efficiency, flexible but guaranteed harvests and safe and healthy crops (no pesticides or herbicides needed). The grow infrastructure can be installed in new buildings, as well as in existing (industrial) buildings or unused spaces. Above all, it gives the clients the possibility to grow, harvest and consume locally, every day and in any chosen quantity.

Facebook: www.facebook.com/urbancropsolutions

Twitter: www.twitter.com/U_C_Solutions

LinkedIn: bit.ly/UrbanCropSolutionsLinkedIn

YouTube: bit.ly/UrbanCropSolutionsYouTube

Harnessing Local Food Production

Harnessing Local Food Production

By Drs. Robert & Sonia Vogl

Contributors

In our efforts to promote sustainable living we have used several approaches: offering classes on gardening and hoop house construction at IREA Headquarters; workshops and booths related to organic gardening; sales of organic produce from local producers; hydroponics and fish farming at the Renewable Energy and Sustainable Lifestyle Fair; and building a demonstration solar greenhouse which we later donated to the Oregon High School agricultural program with modifications gained from our experiences with it.

We initiated a prairie project on the roof of the building occupied by Freedom Field at the Rock River Water Reclamation Campus in Rockford. We called attention to the hydroponics project at Auburn High School developed by Tim Bratina, who took his students on field trips to Chicago and Milwaukee to stimulate their interest in developing a small scale project at the high school. Bratina advocated the utilized of empty factory facilities in Rockford to house what amounts to vertical farms. We were involved in a series of meetings with YouthBuild In Rockford exploring the potential of utilizing their facilities as a site for what would be considered a vertical farm.

Sadly, none of these efforts succeeding in stimulating the utilization of available space as a site for an indoor organic farm in Rockford.

While gardening programs operate in communities in the area, an outstanding one has operated for several years in the DeKalb Schools under the leadership of Dan Kenny. He has agreed to make a presentation at this year’s IREA Fair, providing insights into the nature of his program and its future directions. His is an excellent model of what can happen in a community under effective leadership.

Vertical farming is another sustainability option to investigate. Although it is a relatively new, growing industry, it was suggested as long ago as 1909. Plants are raised indoors in layers, avoiding the extremes of weather. It generally uses hydroponics, the technique used by Bratina’s students. Vegetables are grown in nutrient rich waters and often include fish growing operations as well. Some use aeroponics, growing plants with only misting roots. Being indoors, LED grow lights are used to replace sunlight. Although it is an efficient use of resources, artificial light, heat and power are needed.

Recently some large-scale indoor gardening operations raising produce on a year-round basis and marketing through local supermarkets have been established in Chicago and Rochelle.

Mighty Vine in Rochelle grows tomatoes in a greenhouse operation and markets them through regional supermarkets. Bright Farms, also in Rochelle, offers a broader range of greens. Both of these operations are backed by outside interests and provide their produce on a year-round basis.

Chicago’s The Plant has been in operation for several years. It combines aquaculture, produce production, a brewery and an algae bioreactor. They are installing a biogas operation to reduce electricity costs. When it opened, the 90,000 square foot facility was the largest in the world. It is expected to produce one million pounds of organic greens including lettuce, spinach, basil and mint annually. It also expects to provide hundreds of jobs.

Although these farms are growing, Farmed Here in Bedford Park, formed in 2013 and billed as “the world’s largest indoor vertical farm,” closed its growing operations this year. It is, however, still producing food products.

Vertical farms are seen as an integral component in providing some of the food needs of urban populations and jobs for the communities. Such installations are expected to expand rapidly in urban centers around the world in response to the ravages of climate change, ongoing population growth and the desire to consume cleaner organic foods.

Drs. Robert and Sonia Vogl are the President and Vice President of the Illinois Renewable Energy Association.

UMass Hydro To Grow Fresh Produce For Students Year Round

UMass Hydro To Grow Fresh Produce For Students Year Round

Posted by Callie Hansson on March 8, 2017 · Leave a Comment

Christina Yacono/Collegian

If you look out of the campus-side windows in Franklin Dining Commons after the sun has gone down, you can see a mix of white, blue and magenta lights illuminating the inside of the Clark Hall Greenhouse.

These lights mark the home of the UMass Hydroponics Farm Plan, where Dana Lucas, a junior sustainable food and farming major, and Evan Chakrin, a nontraditional student majoring in sustainable horticulture, have been working throughout the winter growing fresh leafy greens.

Back in December, the duo received a $5,000 grant from the Stockbridge School of Agriculture to grow produce year-round on an on-campus hydroponic farm. Hydroponics, a method of farming with water and nutrients in place of soil, allows for a continual harvesting cycle.

Along with limited pesticide use and saving 90 percent more water than a traditional farm, the farm will produce approximately 70 heads of lettuce a week, every week of the year. Lucas and Chakrin emphasize the importance of this perpetual cycle in meeting the University’s sustainability efforts.

On the University of Massachusetts website, it states, “The University recognizes its responsibility to be a leader in sustainable development and education for the community, state and nation.”

“I don’t know how we can say our food is sustainable at UMass if it’s only grown 10 weeks of the year in New England,” Lucas said.

The location allows UMass Hydro to get their greens across campus by either walking, biking or driving short distances, leaving almost no carbon footprint.

“I think this is something that really excites me and Evan because we really see a demand for fresh, local food and this is a way to actually fulfill it,” Lucas said.

Although the farm’s production capacity cannot currently meet the needs of the dining halls, Lucas and Chakrin are looking into alternative options to get their greens on the plates of students.

“We’re kind of just centering on student businesses right now because they’re smaller and they’re run by our friends, so we can easily get into the market,” Lucas said.

Their first official account is with Greeno Sub Shop in Central Residential Area.

Last week, Greeno’s hosted a special where UMass Hydro’s microgreens were free to add to any menu item.

In a statement posted to their Facebook page, they stated, “One of the goals of our mission statement is to source locally whenever possible, with UMass Hydro right down the hill, this is almost as fresh as it can get.”

Chakrin and Lucas are currently working on getting their greens served at other on-campus eateries.

In addition to adding more accounts, there is a strong focus on getting other students interested in the emerging field of hydroponics.

“We can use this as a teaching facility for students. The techniques we’re using are used in multi-acre industrial greenhouses for lettuce, so we could scale right up potentially,” Chakrin said.

The two are hoping to work UMass Hydro into the curriculum in Stockbridge, allowing students to work hands-on with the systems while also earning credits.

“Maybe we can do a one credit, half semester thing or something,” said Chakrin.

“There has been some discussion about having an accredited course for next fall where we can teach what I’m assuming are mostly going to be Stockbridge students, but we’re open to anybody and everyone who’s interested in getting involved with hydroponics,” Lucas said.

The grant covered the cost of seeds, equipment and other miscellaneous items like scissors, but the responsibility of building the farm fell entirely on Lucas and Chakrin.

“It felt really cool that we were given this much responsibility I feel like, to just buy the stuff and then build it,” Lucas said.

Chakrin noted how one of the biggest obstacles faced in getting the project off the ground was finding an available space on campus.

“Initially we were just asking for a 10-by-10 closet somewhere, then our professor was like ‘Do you think this greenhouse will work?’ and we were like ‘Of course!’” Chakrin said.

“He kind of posed it as a bummer that we weren’t going to be in a closet and we were like ‘No, no, no that’s fine!’” Lucas said, laughing.

“Without the space, none of it would be possible, so being allowed to use this space is just huge and we’re so lucky to have that,” Chakrin said.

Out of the entire space granted to UMass Hydro, only a portion of it is currently being used.

In order to make use of the underutilized space, Chakrin and Lucas are hoping the future of UMass Hydro involves more funding.

“We want to see Dutch buckets and a vertical system in here so we can show students the breadth of what you can do with hydroponics,” Lucas said.

Visitors are encouraged to stop by at the Clark Hall Greenhouse on Tuesdays between 3 p.m. and 7 p.m.

Callie Hansson can be reached at chansson@umass.edu.

Local Roots Hits The Road To SXSW With World’s First Traveling Indoor Farm

Local Roots Hits The Road To SXSW With World’s First Traveling Indoor Farm

Launch of National Tour Features Newest Methods in High Tech Agriculture Production

March 08, 2017 12:11 PM Eastern Standard Time

LOS ANGELES--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Local Roots Farms will debut the world’s first traveling indoor farm at SXSW, March 11-15, 2017. Built inside a 40’ shipping container, the mobile farm uses a proprietary form of hydroponic technology to grow leafy greens equal to five acres of land, 365 days a year, with up to 99% less water than conventional agriculture and is pesticide and herbicide free. The farm departed from the Local Roots headquarters in Los Angeles today to set up residency at the SXSW Festival in Austin, Texas.

@LocalRootsFarms to debut world’s first traveling indoor farm at SXSW! Follow our #lettuceadventures at #sxsw2017

Tweet this

Centrally located in the main SXSW exhibition hall (Booths #2011-2015), festival-goers will have an opportunity to tour inside the high tech farm. The tour focuses on the Local Roots proprietary approach to indoor farming, including the design and engineering of their modular indoor farms- see video. Capitalizing on both traditional farming methods and scientific breakthroughs at NASA, the Local Roots traveling farm features the newest methods of agricultural production.

“There is nothing like experiencing the farm firsthand,” says Local Roots VP of Business Development Brandon Martin. “We’re excited to make this unique experience available to the public with the launch of our cross-country tour. The interactive experience is truly unique and provides a profound understanding of the impact this technology will have on the future of farming.”

During the SXSW Festival, Local Roots Founder and CEO Eric Ellestad will speak on the Funding the Future of Food Tech panel on March 12. Local Roots will also be on display at the Food and Tech Innovation Spotlight on March 11. The program will explore the practical applications for this new form of growing food, including urban development and the creation of a more sustainable food system.

SXSW is the first of a series of road trips, with plans for the traveling farm to make quarterly tours throughout 2017. Additional dates and cities will be announced in May 2017. The farm will be used as an educational tool to inspire consumers about agriculture science & technology with stops at schools, corporate campuses, restaurants, and festivals throughout the U.S.

About Local Roots Farms

Local Roots designs, builds, deploys, and operates controlled-environment farms that yield the highest quality, locally-grown produce using breakthrough technologies. These farms, called TerraFarms, grow with up to 99% less water, 365 days a year, without pesticides or herbicides. Headquartered in Los Angeles, CA, Local Roots is a portfolio company of the Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator (LACI). The Local Roots R&D team, comprised of plant science, botany, agronomy, design and engineering specialists, utilizes a vast body of data to grow better-tasting and nutrient-rich produce with guaranteed harvests and yields. Visit http://www.localrootsfarms.com and follow our #lettuceadventures on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

Contacts

Local Roots Farms

Allison Towle, 310-779-6993

Director of Corporate Development

a.towle@localrootsfarms.com

or

LACI

Laurie Peters, 818-635-4101

Communications Director

lpeters@laci.org

Program Educating and Uplifting East Oakland Kids

Program Educating and Uplifting East Oakland Kids

By Shelby Pope MARCH 7, 2017

It started with a lemon tree. Kelly Carlisle didn’t grow up gardening. She didn’t have a windowsill herb garden. She knew about farming, of course, but in her mind there was a disconnect: food just sort of showed up at the grocery store. She worked a corporate job, wearing fancy clothes and heels to work. But she had gotten laid off during the recession, and one day a few years ago, she ended up at a Bay Area nursery with her daughter. They bought a lemon tree, and as it slowly started to flourish, so did Carlisle’s interest in gardening.

Around the same time the, she found herself reading more and more articles about Oakland, where she spent her childhood: about its status as one of the country’s most dangerous cities, the high rate of teen prostitution and dismal school dropout statistics. She wanted to do something that combined a concrete way to help Oakland’s kids with her newfound love of gardening. So in 2010, she started Acta Non Verba: Youth Urban Farm Project (ANV), a nonprofit that introduces low-income East Oakland children to the joys of gardening while contributing financially to their future. Local children farm a small plot at Tassafaronga Recreation Center and sell the produce through farmers markets and a CSA. All the proceeds go into individual savings accounts for each child, earmarked for their education. There’s also an eight week summer camp, camping and field trips, and community farm days. Since their founding, they’ve served over three thousand local kids.

“For generations, our communities have been told that farming is not for us,” Carlisle said. “When we talk to our kids about what a farmer looks like and where farmers live, it’s very abstract. Nobody knows a farmer, it’s all what they’ve seen on TV. There are no 4-H clubs in the flatlands.”

The financial aspect of the program was inspired by San Francisco’s San Francisco Kindergarten to College Program, where every kindergartner entering a public school is given a savings account with $50, with incentives for families that regularly contribute. (Research has shown that children are more likely to attend college if there’s money set aside for it).

But the money is just part of the way Acta Non Verba (Latin phrase meaning: actions not words) prepares children for the future. Most of the kids Carlisle works with want to be athletes, musicians, actresses–or cops, so they can carry a gun. The program allows them to explore the sprawling agricultural industry, to show them a field and a future that could be theirs.

“If you’re not into getting dirty, not into planting and harvesting, there’s all these other things that you can do,” Carlisle said. “There’s being a soil scientist, being an entomologist, pest management. That, to me, is as important as STEM.”

It hasn’t been easy. Like Carlisle, many of the kids have grown up disconnected to where their food comes from. And in East Oakland, where most kids grow up with acute food insecurity (most qualify for reduced lunch), an emphasis on pesticide-free local produce can seem precious or irrelevant. Once, the garden yielded a bumper crop of collard greens. Carlisle offered some to a woman in the neighborhood. The woman was suspicious, unbelieving that the park’s small garden could actually yield something and that Carlisle had grown it.

The greens were safe, Carlisle said. She had farmed them herself. “She’s like ‘Why would you call yourself that? No girl, we’re not farmers, you’re a gardener,’” Carlisle remembered. “I was offended, but it’s something to think about; trying not to sound superior. The farm-to-table movement doesn’t always feel like it applies to folks in my community. But to grow culturally relevant produce like collard greens and mustard greens, the community is starting to come around and see that, like with me, food is grown, it doesn’t just show up at the grocery store miraculously.”

To help share her message, Carlisle involves parents, both as volunteers and paid positions so the children’s healthy eating education is reinforced at home. She also makes it fun: she talks about a local boy named Jordan, who’s always thrilled to share his new knowledge about plant biology, or a pair of sisters whose eyes light up when it’s time to sing camp songs.

Thing could be easier, Carlisle acknowledges. She’d like to be able to afford more employees. She’d like there to be a grocery store near the farm, a nice one emphasizing healthy options. She’d like to only focus on food issues. But the more time she spends in East Oakland, the more she’s forced to confront other issues, like the area’s high rates of child asthma, or the giant crematorium that’s slated to be built near her farm. But Carlisle, who served in the Navy and whose parents also started their own nonprofit–“Service is probably ingrained in my DNA,” she said–isn’t going to give up anytime soon.

“One thing that we don’t think about in these high tech days is that we’re all here because somebody cultivated and worked with land,” she said.

“Even every single culture has some kind of agriculture going on. For me, farming is not only something that soothes my soul and makes me feel like I’ve accomplished something in a day, it’s also a connection to something bigger than myself, to a community and something innate: trying to improve my community through hard work and cultivation of land.”

AUTHOR: SHELBY POPE

Shelby Pope is a freelance writer living and eating her way through the East Bay. She’s written about food, art and science for publications including the Smithsonian, Lucky Peach, and the Washington Post's pet blog. When she’s not taste testing sourdough bread to find the Bay Area’s best loaf, you can find her on Twitter @shelbylpope or at shelbypope.com

Farm-To-Table Amenities Yield Profits

Farm-To-Table Amenities Yield Profits

Even on small infill sites, residential builders and developers are making room for vegetable gardens.

Farm-to-table-centered communities are a big draw for home buyers, but they can also mean more profits for builders and developers. With creative land planning, communities of all sizes can tap into the growing interest in fresh produce and backyard gardens.

Farmscape, the largest urban farming venture in California, works with developers, architects and cities to turn cookie-cutter urban communities into agrihoods. The gardens not only attract a higher future sale, but also draw in a wider demographic of individual property buyers who are looking to live in a more interactive community environment, says Farmscape co-founder Lara Hermanson. Here, BUILDER talks with Hermanson about the benefits and challenges of agriculture-based amenities.

How many agrihoods have you worked on? What do they entail?

Farmscape currently has 15 agrihoods in various stages of development. Several multifamily projects were completed last year and have been feeding those apartment communities since July. Trellis (a new Pulte development in Walnut Creek, Calif.) just broke ground last month. We also have a half dozen additional projects still going through the entitlement process. All our projects start with the design, and we take into account the architecture, branding and community demographics as well as the microclimate.

From there, we assist our clients through the entitlement process, appearing at all review meetings to help educate city councils, community members, and design review commissions on what this new amenity/landscape entails. After approvals, we work with the installation team to get the project built, and then get sent to the HOA or apartment management team to schedule maintenance. Finally, we get in front of our end user-the community, to create volunteer opportunities and workshops so they can get their hands dirty as well.

How much do they cost?

Installation for a small agrihood starts around $20K and goes up from there depending on complexity and size. A small agrihood could consist of 8-10 raised beds, 6 orchard trees and mulching. Large agrihoods can include more sizeable orchards, row crops, vineyards and ornamental garden. Large or small, the final result is a product that encourages residents to enjoy the perks of rural farm life with none of the responsibility.

What type of value do they add to a project?

Good landscaping and maintenance can add around seven percent to a commercial or residential property. Excellent landscaping (such as Farmscape's gardens) can increase the value to up to 28%. Agrihoods also have the ancillary benefit of creating a sense of place for communities, increasing resident well-being, and enhancing pride of ownership. We have experienced easy approvals in city councils, thanks to resident enthusiasm for agrihood projects.

What are some other benefits?

Generally, developers can expect fewer resubmits and greater community support during the entitlement process alongside Farmscape supporting developers through the design, installation, maintenance and programming phases. Additionally, In Santa Clara, the community rallied behind the Win6 agrihood development, with over 300 community members regularly attending City Council meetings in support of the project. They even created #Agrihood t-shirts and an online campaign to move the dial for the developers.

Does a community need a lot of land to have residential farming?

Not necessarily. A small agrihood can be designed to suit a 500 square foot space, and are very appropriate for infill developments. Larger suburban development can expand to several acres. We design each project to match the neighborhood and the future residents.

Running with setup costs from $55,000 to larger plots of $1 million per development, the gardens include row crops, raised beds, orchards, vineyards, and edible-inspired ornamental landscaping. Farmscape trains and manages local team members in the Farmscape method, and offers continual training and support to agrihood communities. The final result is a product that encourages residents to enjoy the perks of rural farm life with none of the responsibility.

Why do you think there is such an interest in gardens?

I think there's several reasons. Most households have two working adults, who don't have a lot of downtime for gardening. Coming home to an awesome vegetable garden, that they don't have to work themselves, is a great perk. Also, the drought in California has made everyone re-think their landscape. Agrihoods, with smart drip irrigation, use a lot less water than traditional lawn. Besides, no one wants their home to have the same landscaping as an office building. But most importantly, people love to eat good food. If they can eat a fresh picked salad every day and take a homegrown peach to work, life is pretty good.

About the Author

Jennifer Goodman is Senior Editor at BUILDER and has 17 years of experience writing about the construction industry. She lives in the walkable urban neighborhood of Silver Spring, Md. Connect with her on Twitter at @Jenn4Builder.

A D.C. Urban Farm Takes On Urban Problems

A D.C. Urban Farm Takes On Urban Problems

Monday, March 6, 2017 - 12:44am

Urban farming can serve needs of local communities beyond nutrition.

Little more than grass used to grow on the two-acre plot behind a middle school in the District of Columbia where tomatoes, okra and infrastructure for food entrepreneurs will begin cropping up this year.

In a ward of the city with just two grocery stores serving more than 70,000 residents, fresh produce is hard to come by. But the Kelly Miller Farm, which will be situated behind a middle school with the same name, aims to offer much more: youth programs, a community garden accessible to seniors and a commercial kitchen from which area residents can launch food-based businesses.