Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

5 Things To Know About Urban Organics Aquaponics Farm

5 Things To Know About Urban Organics Aquaponics Farm

Monday, June 5, 2017 by Mecca Bos in Food & Drink

Urban Organics aquaponics farm now has two locations in St. Paul

Many years ago, I stood with Dave Haider in a nearly empty grain silo at the old Hamm’s Brewery staring at a blue pool.

He had big dreams. One day, wife Kristen called him into the room, where she was watching TV.

“Look,” she said, and pointed. On the screen was an aquaponics farm, a closed-loop system for farming fish and produce. The fish enrich the water, the water is filtered through the root systems of the plants, and both are eventually edible for humans.

“You should do that.”

“OK,” said Haider.

And thus began their journey, along with partners Fred Haberman and Chris Ames, to implement Urban Organics aquaponics farm. The Hamm’s Brewery was their first location, and a second is now up and running in the Historic Schmidt Brewery. They’ve come a long way since a single pool in a silo.

Five things to know about the Twin Cities largest aquaponics farm:

1. Urban Organics greens are now available for purchase, including green and red kale, arugula, bok choy, green and red romaine, swiss chard, and green and red leaf lettuces. Get them at Hy Vee supermarkets in Eagan and Savage and at Seward, Wedge, and Lakewinds co-ops.

Want to taste the fish? Get it at Birchwood Cafe. The Fish Guys (local fish wholesaler led in part by Tim McKee) will be distributing Urban Organics fish, so watch for it at stores and restaurants in the coming months (more info on the fish below).

2. The farm was recently featured in The Guardian as a Top 10 innovative “next-gen” urban farm. Urban Organics was noted for using only 2 percent of the water used in conventional agriculture, and for its mission to prove the viability of aquaponics systems overall.

Other eco-friendly perks of the Urban Organics aquaponics system: they do not rely on herbicides, pesticides, or chemical fertilizers, and raising fish indoors takes pressure off oceans and wild-caught species.

More food raised in urban centers means less food traveling in from far-flung places. Urban Organics calls its product “hyper-local.”

3. The numbers: The 87,000 square foot Schmidt farm aims to provide 275,000 pounds of fresh fish and 475,000 pounds of organically grown produce per year.

Currently, the farm is at 30 percent capacity for produce, and they project being at full capacity by fall. Getting their Arctic Char and Atlantic Salmon to a harvestable size of eight to 10 pounds will take another 11 to 20 months.

4. If you happen to find yourself at a HealthPartners hospital, you might wind up eating Urban Organics food from your patient meal tray, cafeteria salad bar, or grab-and-go retail kiosk.

5. Part of the Urban Organics mission statement is to grow fresh food in urban “food deserts,” which would not otherwise have access to locally produced food. And with an indoor system, they can do it year-round, even in the dead of a St. Paul winter.

For more information on Urban Organics: urbanorganics.com

(Toggle around in their website. It’s kinda fun.)

700 Minnehaha Ave. E., St. Paul

543 James Ave. W.

Biosphere's Vertical Gardens Will Provide Produce For Public

Biosphere's Vertical Gardens Will Provide Produce For Public

- By Tom Beal Arizona Daily Star

- Apr 18, 2017

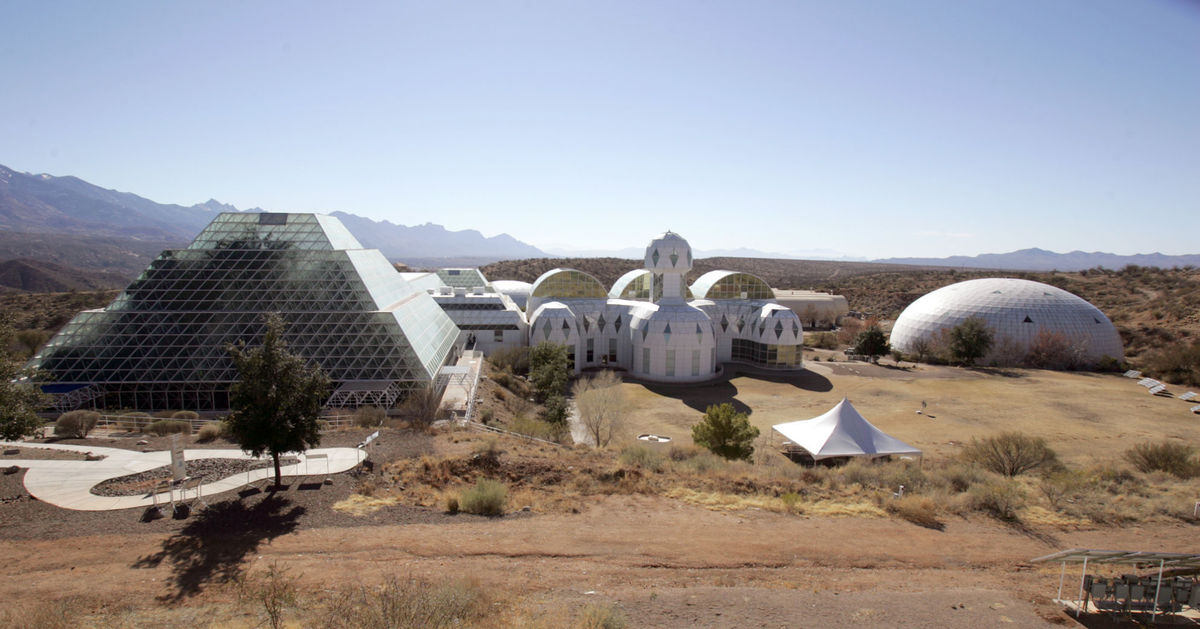

Food crops are coming back to Biosphere 2, but they won’t be planted in the 3 acres under glass at the University of Arizona research facility in Oracle.

A company named Civic Farms plans to grow its leafy greens under artificial lights in one of the cavernous “lungs” that kept the Biosphere’s glass from imploding or exploding when it was all sealed up.

The lungs, which equalized the air pressure in the dome, are no longer needed now that the Biosphere is no longer sealed. The west lung will be transformed into a “vertical farm” that will train LED lights on stacked racks of floating plants whose roots draw water and nutrients from circulating, fortified water.

A variety of leafy greens and herbs such as kale, arugula, lettuce and basil will be packaged and sold to customers in Tucson and Phoenix, said Paul Hardej, CEO and co-founder of Civic Farms.

He also expects to grow high-value crops, such as microgreens, Hardej said.

Hardej said the company plans to complete construction and begin growing by the end of the year.

Civic Farms’ contact with the UA allows for half the 20,000-square-foot space to be devoted to production, with areas given over to research and scientific education.

The UA will lease the space to Civic Farms for a nominal fee of $15,000 a year. In return, the company will invest more than $1 million in the facility and dedicate $250,000 over five years to hire student researchers in conjunction with the UA’s Controlled Environment Agriculture Center.

Details of branding haven’t been worked out, said UA Science Dean Joaquin Ruiz, but don’t be surprised to find Biosphere Basil turning up in your salad soon.

Hardej said the “brands” established by the UA were lures for his company.

“The UA itself has a brand recognition throughout the agricultural industry and specifically the Controlled Environment Agriculture Center. They have a lot of respect worldwide.”

“Also, the Biosphere itself is a great story,” he said.

“The original intent was to develop a self-sustaining, controlled environment where people could live, regardless of outside conditions.

“In a way, this is a fulfillment of the original purpose,” he said.

Hardej said he recognizes the irony of growing food in artificial light at the giant greenhouse. He is convinced, however, that growing plants with artificial lighting can become as economical as growing them in sunlight.

“Decades ago, greenhouses were very innovative. It felt like it allowed the farmer to control the environment. It did not control the light and also the temperature differentials.”

Hardej said indoor growing allows you to control all the variables — the water, the CO2 levels, the nutrients and the light. “Farming is much more productive and much more predictable than in a greenhouse,” he said.

You can’t stack plants on soil, or even in a greenhouse, he said. “A vertical farm can be 20 to 100 times more productive. The overall direction globally is indoors,” he said.

Indoor agriculture is still a sliver of overall crop production, said Gene Giacomelli, director of the UA’s Controlled Environment Agriculture Center (CEAC) and most indoor operations are greenhouses.

“Vertical farms” account for a small portion of that sliver, but are a fast-growing segment for growing high-value crops with a level of control over the environment that can’t be attained elsewhere, he said.

“Theoretically, we should be able to control everything,” he said.

Murat Kacira, a UA professor of agricultural-biosystems engineering, is already working on systems to do that in a lab at the CEAC center on North Campbell Avenue, where he grows leafy greens and herbs under banks of LED lights. He can control the wavelengths of light, temperature, humidity, the mix of oxygen and carbon dioxide and the nutrients available to the plants.

Those variables can be tuned to improve the yield, quality and nutritional value of the plants being grown. He is developing sensor systems that allow the plants to signal their needs.

A lot of questions remain, said Giacomelli. Different plants require different inputs. Young plants have different needs than mature ones.

Air handling is a tricky problem, he said. Air flow differs between the bottom and top racks and at different locations of a given rack of plants.

It will take “more than a couple years” to figure it all out, said Giacomelli.

Kacira said the Civic Farms installation “is a really complementary facility to the research going on under glass.”

He expects the Biosphere to become a “test bed” for more research on the nexus of food, water and energy.

Ruiz said that “nexus” is the direction for research at the Biosphere for the coming decade.

'Plant Factories' Churn Out Clean Food in China’s Dirty Cities

'Plant Factories' Churn Out Clean Food in China’s Dirty Cities

Researchers build urban farms, crop labs to combat contamination

Bloomberg News | May 25, 2017, 4:00 PM CDT

Yang Qichang walks through his “plant factory” atop the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Beijing, inspecting trays of tomato vines that may help farmers slip the stranglehold that toxins have on China’s food supply.

The containers are stacked like bunk beds, with each vine wrapped in red and blue LED lights that evoke tiny Christmas trees. Yang is testing which parts of the visible-light spectrum are optimal for photosynthesis and plant growth while using minimal energy.

He’s having some success. With rows 10 feet high, Yang’s indoor patches of tomatoes, lettuce, celery and bok choy yield between 40 and 100 times more produce than a typical open field of the same size. There’s another advantage for using the self-contained, vertical system: outside, choking air pollution measures about five times the level the World Health Organization considers safe.

Rows of tomato seedlings are monitored in an experimental greenhouse at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

“Using vertical agriculture, we don’t need to use pesticides and we can use less chemical fertilizers—and produce safe food,” said Yang, director of the Institute of Environment and Sustainable Development in Agriculture.

Yang’s government-funded research on vertical farming reflects the changing mindset of China’s leaders, who for decades preoccupied themselves with raising incomes for 1 billion-plus people. Runaway growth created the world’s second-biggest economy, yet the catalyzing coal mines and smokestacks filled the environment with poisons and ate up valuable farmland.

That stew inhibits the nation’s ability to feed itself, and is one reason why China increasingly relies on international markets to secure enough food. For example, it imported about $31.2 billion of soybeans in 2015, an increase of 43 percent since 2008, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. About a third of that came from the U.S.

Given the fluctuating state of trade relations with U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration and the increasing global competition for resources, China is turning to technology to make its land productive again.

“We will undertake rigorous investigations on soil pollution, and develop and implement category-based measures to tackle this problem,” Premier Li Keqiang told the National People’s Congress in March.

The silver bullet would be to eliminate emissions and industrial waste, an unrealistic option for a developing $11 trillion economy. Yet inventors and investors believe there are enough promising technologies to help China circumvent—and restore—lost agricultural productivity.

Government money backs a variety of efforts to modernize farming and improve growers’ livelihoods. The state-run Agricultural Development Bank of China pledges 3 trillion yuan ($437 billion) in loans through 2020 to finance key projects promoted by the Ministry of Agriculture.

By comparison, the value of U.S. agricultural production last year is forecast to be $405.2 billion.

Favorable terms will be offered to projects trying to improve efficiency, increase the harvest, modernize farming operations and develop the seed industry to ensure grain supplies, the bank said.

The loan program also intends to stimulate overseas investment in agriculture by Chinese companies. The biggest example would be state-owned China National Chemical Corp.’s planned acquisition of Switzerland’s Syngenta AG for $43 billion. That will give ChemChina access to the intellectual property, including seed technology, of one of the largest agri-businesses.

Yet China is reluctant to unleash genetically modified foods into its grocery stores. The government doesn’t allow planting of most GMO crops, including pest-resistant rice and herbicide-resistant soybeans, especially as an October survey in the northern breadbasket of Heilongjiang province showed that 90 percent of respondents oppose GMOs. China will carry out a nationwide poll on the technology next month.

“China’s past food-safety problems have caused the public to distrust the government when it comes to new food technologies,” said Sam Geall, an associate fellow at Chatham House in London.

A researcher transplants rice seedlings in a greenhouse of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

About a fifth of China's arable land contains levels of toxins exceeding national standards, the government said in 2014. That's more than half the size of California.

About 14 percent of domestic grain is laced with such heavy metals as cadmium, arsenic and lead, scientists at government-affiliated universities wrote in 2015. The danger is most evident in industrial coastal provinces, where many of the world’s iPhones and Nikes are manufactured.

The government of Guangdong province, adjacent to Hong Kong, said in 2013 that 44 percent of the rice sampled locally was laced with excessive cadmium, which can damage organs and weaken bones if consumed regularly in high quantities.

That’s where Yang’s “plant factories” would come in. For now, the greenhouse-like structures are mostly demonstrations as he tries to improve their energy efficiency and make their produce more affordable to consumers—and a better investment for the government. Yang’s work is supported by an $8 million government grant.

“With the challenges our agriculture is facing, including China’s rapid urbanization and the increasing need for safe food, plant factories and vertical agriculture will undergo a big development in China,” he said. “There will be many ways to farm in big cities.”

He isn’t alone in hunting for techniques to grow untainted food in the concrete jungle. A Beijing startup called Alesca Life Technologies is using retrofitted shipping containers to farm leafy greens.

Roots of a kelp plant grow through a sponge under artificial light at an Alesca Life shipping-container farm in Beijing. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

A demonstration model is parked atop metal stilts in an alley between a Japanese restaurant and a block of office buildings in Beijing.

Inside, co-founder Stuart Oda, a former investment banker for Bank of America Merrill Lynch in the U.S. and Japan, checks on rows of planters sprouting peas, mustard, kale and arugula under LED bulbs. Alesca Life’s smartphone app allows growers to monitor air and water conditions remotely.

“Agriculture has not really innovated materially in the past 10,000 years,” Oda said. “The future of farming—to us—is urban.”

The containers can sell for $45,000 to $65,000 each, depending on the specifications, Oda said. Alesca Life sold portable, cabinet-sized units to a division of the Swire Group, which manages luxury hotels in Beijing, and the royal family of Dubai. The startup hasn’t publicly disclosed its fundraising.

Shunwei Capital Partners, a Beijing-based fund backed by Xiaomi Corp. founder Lei Jun, has invested in 15 rural and agriculture-related startups in China, including one that makes sensors for tracking soil and air quality.

Shunwei manages more than $1.75 billion and 2 billion yuan across five funds.

“For agriculture technology to be adopted on a wider scale, it needs to be efficient and cost-effective,” said Tuck Lye Koh, the founding partner.

That’s one reason why Shunwei is backing agricultural drones, which more precisely spray fertilizers and the chemicals that ward off crop-destroying pests and diseases.

Clockwise from top: Trays of wheat grass grow in one of Alesca Life's converted containers; Kelp seedlings are cultivated in a foam mat at the urban farm; An employee carefully places each seed.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

As China’s farmland dwindled because of urbanization, the remaining growers attempted to boost yields by soaking fields with fertilizers and pesticides, degrading the soil and contaminating the crops.

Farmers in China use four-and-a-half times more fertilizer per hectare (2.4 acres) of arable land than farmers in North America, according to the World Bank.

“There’s overuse of fertilizers in every country, but especially China,” said Jeremy Rifkin, whose books include “The Third Industrial Revolution.” “The crops can’t even absorb the amount of fertilizers that are being dumped.”

As dawn squints over cornfields on Hainan island, a pastel-blue truck rumbles down the gravel road and stops. Workers emerge with a pair of drones made by Shenzhen-based DJI and a cluster of batteries.

Zhang Yourong, the farmer managing 270 mu (44 acres), arrives in a pickup loaded with pesticide bottles. The crew adds water and pours the milky concoction into 10-liter plastic canisters suspended under the drones.

The stalks part like the wake of a boat as the drones fly over. Every 10 minutes, the eight-armed machines return, and the crew refills canisters and changes batteries.

Trays of kelp, a vitamin and mineral-rich seaweed, are ready to be transplanted to bigger growing spaces at Alesca Life's demonstration farm. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Zhang used to hire four or five workers to walk the fields with backpack sprayers for five days. Now, the drones cover his crops in a morning and use 30 percent less chemicals, he said.

That’s what the government needs to hear as it tries to make China’s food supply safer.

“This is much easier and much faster than before,” Zhang said. “This is the future. Many farmers are switching.”

Vertical Farming: Farms of the Future? The Pros & Cons

Vertical Farming: Farms of the Future? The Pros & Cons

Even though more than 40 percent of American land is farmland, more people than ever before are moving into cities. Many of us may never step foot on a farm, and unless you’re lucky enough to live near a local farmers’ market, you’re likely at the mercy of your local supermarket as to what types of fruits and veggies you can purchase and where they come from.

But while cities keep booming, people are more concerned than ever about where their food is coming from. Is there really a way to merge the two? Vertical farming, some say, is the answer.

What is Vertical Farming?

Vertical farming is a method of producing crops that’s quite different from what we normally think of as farming. Instead of crops being grown on vast fields, they’re grown in vertically, or into the air. This normally means that the “farms” occupy much less space than traditional farms: think farming in tall, urban buildings vs. farming outdoors in the countryside.

Vertical farming is credited to Dickson Despommier, a professor of ecology at Columbia University, who came up with the idea of taking urban rooftop gardens a step further, and creating vertical farming “towers” in buildings, that would allow all of a building’s floors, not just the rooftop, to be used for producing crops.

Most vertical farms are either hydroponic, where veggies are grown in a basin of water containing nutrients, or aeroponics, where the plants’ roots are sprayed with a mist that includes water and the nutrients required to help the plants grow. Neither require soil for the crops to grow. Usually artificial grow lights are used, though in places blessed with an abundance of natural sunlight, it might be a combination.

And, in some places, it seems to be working quite well. Sky Greens is in Singapore, a country with a population of more than 5.5 million on a main island that’s just 26 miles wide and 14 miles long. In a four-story rotating greenhouse, the company produces 1 ton of greens each day, impressive for a country that imports about 93 percent of its produce, since there’s little available land.

Back in the States, AeroFarms, based out of Newark, NJ, operates several farms. Its global headquarters is a 70,000-sq. ft. vertical farming behemoth, the largest in the world, and can harvest up to 2 million pounds of produce annually. Additionally, AeroFarms helps area children get a little closer to the foods they eat. In a partnership with a local elementary school, students actually harvest their own greens in a 50-sq. ft. AeroFarms unit in their dining hall.

5 Benefits of Vertical Farming

While vertical farming is still relatively new, there are some real benefits.

1. There’s year-round crop production. Say goodbye to seasonal crops. Because vertical farms can control all of the technology required to grow the produce, there’s really no such thing as the wrong season. If a head of lettuce needs a certain amount of humidity and light, a vertical farm can arrange that. A growing season of just a few months is replaced with a year-round production.

Bonus: without things like bugs and weeds, vertical farms don’t need to use pesticides and other harmful chemicals to ensure plants keep growing.

2. They’re weatherproof. Every farmer knows that unseasonably cold or hot temperatures can affect an entire harvest, while a natural disaster like flood or hurricane can derail them for years. In a controlled environment like a vertical farm, there’s no need to fear Mother Nature.

3. They use less water conservation. Generally, vertical farms use less water than traditional farms. Most data points to a 70-percent reduction in water use compared to normal farms. As water becomes more scarce, particularly in communities already suffering from droughts, this is huge.

4. There’s less spoilage. Without the risk of fluctuating weather conditions or pesky critters, there’s a lot less food waste. On traditional farms, up to 30 percent of harvests are lost each year. (3) On vertical farms, that number goes way down.

Additionally, the food from vertical farms is usually sold locally, reducing transportation emissions and time from farm-to-table. Instead of several days of transport, during which foods can go bad, produce can be in the hands of a consumer in just hours.

5. They take up less space. In vertical farming, one acre of indoor space is the equivalent of 4-6 outdoor acres. A lot less space is necessary to produce the same amount of produce, particularly useful in cities, where outdoor land is limited. Instead of building out, vertical farms allow people to build up.

They also create farms out of places that already exist, like abandoned warehouses and buildings. AeroFarms’ space, for instance, was a nightclub space that was abandoned. There’s no need for new construction, because we can breathe new life into old spaces.

What’s Not So Great About Vertical Farms

Of course, it’s not all roses when it comes to vertical farms.

First of all, not everything can be grown in a vertical farm. Things like potatoes don’t turn enough of a profit to make it worth growing them indoors. Vertical farms usually stick to leafy greens and tomatoes, which grow quickly and can be sold at a premium on the market. Heavy crops like wheat and rice, which make up a lot of the American diet, aren’t feasible for vertical farms, as they require a lot more space and weigh more.

While vertical farms might also use a lot less water, they do require a lot of energy. In nature, sunlight is free. In a vertical farm, all those artificial lights add to carbon emissions at a much higher rate than traditional farms.

One reporter found that it would take 1,200 kilowatt hours of electricity to power the lights it takes to produce 2.25 pounds of food, or about the same as the average American refrigerator uses a year.

That’s an incredible amount of energy for a very small amount of food, and that’s before considering heating and cooling costs.

When producers have to pay for things that regular farms get for free, those costs are passed onto consumers. Greens grown in vertical farms are more expensive than their traditionally grown counterparts which means that they’re likely out of reach for the average consumer.

It’s ironic: while in theory, vertical farms are perfect for city dwellers, who are likely to be further away from farms, the price point will still be out of reach for many. Essentially, if you can afford the vertical farming produce, you likely already have access to better food options to begin with.

Additionally, while nature can’t disrupt vertical farming crops, human error can. In a perfectly controlled environment, the yields will definitely be better than those in nature.

However, that relies on each person who tends to the vertical farm doing things just right 100 percent of the time. While the time necessary to rectify mistakes is less than “in the wild,” the high cost of running these farms makes errors even costlier.

Are vertical farms ready to flip our country’s agricultural model on its head and completely disrupt traditional farms? It’s unlikely. Vertical farms are still in their infancy and more studies need to be done to figure out how to make them work on a larger-scale — or if that’s even worth it.

But they’re not ready to be discounted just yet, particularly as new methods to reduce energy usage are uncovered. There’s also the chance that certain vertical farming techniques could be incorporated into traditional farms, creating a sort of hybrid. You just might find vertical farmed greens coming to a grocer near you very soon.

Final Thoughts

- Vertical farms are being heralded as the farms of the future.

- Some farms, particularly in large urban areas, are successful already.

- There are several benefits to vertical farming, including no reliance on weather, less water usage, and the ability to convert city spaces into working farms.

- It’s not all positives, though. There’s a limit to what can be grown on vertical farms, their energy usage is really high and the prices will appeal to just a small fraction of people..

Nabeela Lakhani: I’m Taking Action To Create Solutions

Nabeela Lakhani: I’m Taking Action To Create Solutions

Square Roots, a new urban farming accelerator located in Brooklyn, New York, is producing as much food as a 20-acre farm without using any soil. The-five month-old company puts hydroponic growing systems in old, repurposed shipping containers. Each container is capable of producing roughly two acres of food, without the use of pesticides or GMOs. Each container only uses eight gallons of water per day. That’s less than your morning shower.

Nabeela Lakhani is a food entrepreneur at Square Roots specializing in Tuscan Kale and Rainbow Chard. She was one of 10 farmers chosen out of an application pool of 500 for Square Root’s inaugural launch. Food Tank had a chance to speak with Nabeela about her background, current work, and thoughts on approaching solutions in the food system.

Nabeela with her kale at Square Roots. Credit: Nabeela Lakhani

Food Tank (FT): How did you get involved with Square Roots?

Nabeela Lakhani (NL): I’ve always been interested in food and my passion and my purpose has always been around the food industry and the food system. I went to school for public health and nutrition thinking that was going to be the way I made whatever impact I wanted in the food industry, but then as I was going through school I started to realize nutrition was highly clinical and medical. We were looking at treating diseases with medical and nutrition therapy, diseases that could be prevented if we nourished our populations better. We should have been looking at how our food system was prioritizing certain crops over others and how food is distributed in our country. What would happen if we looked at food before it gets to the body, food before it gets to the community? When I discovered that food production and food distribution was what I wanted to pursue I just kind of started telling everyone in my networks that that was what I was now interested in. I used to just tell people, ‘I want to be a farmer I want to be a farmer!’ I was having a hard time getting my foot in the door in urban agriculture because I had no experience; my experience was all health and nutrition related. But I did have a lot of start-up experience so I was really excited about Square Roots. It put the startup experience that I had with the agriculture experience I wanted.

FT: Can you explain how Square Roots works?

NL: We use a standard shipping container, just a regular truck, and it is repurposed to accommodate a hydroponic system. You have these towers lined up inside and the towers are essentially the farm field where everything grows. You control all the elements that a plant needs to grow and you can optimize those elements for that plant’s growing experience, which is then going to reflect heightened taste, heightened freshness, heightened nutritional content. You can even control the nutrient levels that go into the water. And then you’re also controlling the temperature, the climate, the humidity, the CO2 level; you can literally recreate an environment to grow something. For example, if you visited Italy one summer in 2006 and you the best-tasting basil you’ve ever in your life, you could look up the climate and the weather patterns for that time that you were there and recreate that climate inside this container. Another really cool thing is we have a really low water usage, so we use 70 percent less water than conventional farming. This whole container, if you really pack it in, can grow almost two acres worth of food in just that standard shipping container space. It runs on eight gallons of water a day, which is less than your shower.

FT: Are you the first farmers to grow food in a shipping container?

NL: No, actually the containers we use are bought by manufactured by a company called Freight Farms. Their business is to manufacture these containers and then they sell them to customers like us. They have these containers in multiple countries across the world already.

FT: Who is your customer base?

NL: Right now, our customers are mostly adults, although one of my customers is a bunch of NYU students. One of the channels that a lot of farmers are exploring now is farm to local membership, which is basically a weekly delivery to a local community hub. We found that offices are really good for this, because there’s already a community feeling around them. You’re already in a team and you already know the people, so it’s easier to mobilize people and get bigger hubs out of office spaces. That’s one channel that’s really taking off and we’re delivering to places like Adobe and the New York Times building. It’s picking up pretty fast.

Nabeela surveying a wall of produce. Credit: Nabeela Lakhani.

FT: What are you guys growing right now?

NL: Mostly just leafy greens. With hydroponics it is possible to grow fruits and vegetables and one of our farmers is actually experimenting with carrots and radishes and things like that, but given the way the Square Roots program is set up, which is we get this container for one year and we get to build a business out of it, it makes sense to grow whatever makes the most economic sense. If leafy greens take four weeks to grow and yield really high then I’m going to grow that.

FT: What plans does Square Roots have for the future?

NL: Right now we’re based in New York City, but the goal is to get to 20 cities by 2020. Square Roots’ mission is to create an army of young food entrepreneurs who are equipped with experience using technology and building a viable business model. Before I started at Square Roots I felt like I never knew what kind of step I could take or what kind of impact I could have. Revolutionizing the food industry seems so colossal. But now it’s like, ‘No, I’m actually taking action and I can create my own solutions in the future.’ I now have the experience of building a sustainable business and running a business responsibly and impact fully.

Meet The Company Building Farms in Parking Structures

Meet The Company Building Farms in Parking Structures

LIZZY SCHULTZ JUNE 2, 2017 LEAVE A COMMENT

Stuart Oda previously worked as an investment banker before serving as a co-founder of Alesca Life, a Beijing-based agriculture technology company that builds weather-proof, cloud-connected farms in order to enable local food production by anyone, anywhere.

“We’ve developed technology for indoor farming, so it allows farmers to work in an environment that is far safer, cleaner, and closer to the consumers,” said Oda in an interview with Jamie Johansen during ONE: The Alltech Ideas Conference, which he attended as part of the Pearse Lyons Accelerator Program, “We’ve built farms out of second-hand shipping containers, out of underground parking structures, and even restaurant corners.”

Urban farming is not a new concept, but Oda believes his company’s mission differentiates it from their competition: “We actually use the concept of a hub-and-spoke, almost a central kitchen concept, that uses the urban farm as both a nursery and a food production facility to deliver higher quality produce at more affordable prices directly at the point of consumption,” he said.

Oda became interested in agribusiness upon learning that the agricultural supply chain is worth over 20 trillion dollars end-to-end and after he began hearing more about the environmental and economic challenges facing the industry as it works to feed 9 billion people by 2050.

It’s very exciting to think about how the future of farming can impact the consumer, the industry, and the environment,” he said.

Fresh Veggies Grown Close to Home, Without Pesticides — And Without Dirt

Fresh Veggies Grown Close to Home, Without Pesticides — And Without Dirt

Civic Farms touts having “pioneered the vertical farming industry.” The company says its proprietary growing systems, licensed patented technologies, and optimized processes for cultivation and harvesting processes maximize the efficiency and efficacy of growing indoors.

TUCSON (CN) – An ambitious project of emerging agricultural technologies that produce food without soil is taking shape at Biosphere 2, the University of Arizona’s research complex north of Tucson.

Civic Farms, an Austin-based company, this summer will start building a vertical farm in one of two 20,000-square-foot domes – or “lungs” – that regulated pressure inside a sealed glass structure during experiments to study survivability in the 1990s.

The company will invest $1 million to renovate the Biosphere’s west lung, unused for years, and outfit the space with stacked layers to grow soil-free plants in nutrient-laden circulating water under artificial lights.

At full capacity, the vertical farm will produce 225,000 to 300,000 lbs. a year of leafy greens and herbs such as lettuce, kale, arugula and basil, said Paul Hardej, CEO and co-founder of Civic Farms.

“Biosphere itself is a fantastic facility and food production is a big part of what it was originally intended to do,” he said.

As the world population continues to rise, particularly in cities, along with consumer interest in the origins of food, vertical farming is gaining traction as a commercially viable way to increase crop production in a fully controlled indoor environment.

“People want know what they eat and what’s in their food and how healthy and good it is for them,” Hardej said. “Growing food in city centers or close to city centers where people live makes perfect sense.”

Under an agreement with the university, Civic Farms will grow crops in half the space it will lease for $15,000 annually. Research and scientific education will comprise the other half and the company will contribute $250,000 over five years for those efforts.

“We envision that a portion of the lung will be open and accessible to the public so people can come in see how and what it is to have a vertical farm,” said John Adams, the Biosphere’s deputy director.

Civic Farms touts having “pioneered the vertical farming industry.” The company says its proprietary growing systems, licensed patented technologies, and optimized processes for cultivation and harvesting processes maximize the efficiency and efficacy of growing indoors.

The Biosphere already draws nearly 100,000 annual visitors to expansive grounds originally intended to showcase a self-sustaining replica of Earth, or Biosphere 1.

Set on a 40-acre campus against the backdrop of the rugged Santa Catalina Mountains, the Biosphere’s 91-foot steel-glass structure serves as a global ecology laboratory enclosing an ocean, mangrove swamp, rain forest, savanna and coastal desert.

In the early 1990s, a crew of scientists was locked inside the sealed structure in privately funded scientific experiments designed to explore survivability with an eye toward space colonization. Problems with the experiments and management disputes eventually halted the highly public venture.

The University of Arizona took over the property, about 30 miles north of Tucson in the town of Oracle, in 2011.

The Biosphere’s Adams views the planned vertical farm as a good fit for research initiatives.

“For the next 10 years, Biosphere’s focus is very much on food, energy, water – and the nexus,” he said.

Civic Farms’ Hardej said the university’s myriad resources were strong incentives for his company’s new enterprise in Arizona. A big plus are the concepts being developed at the university’s Controlled Environment Agriculture Center on North Campbell Avenue, where scientist Murat Kacira grows leafy crops indoors under LED lights.

“There’s so much interest in this technology platform because it provides the capability to grow food with consistency,” Kacira, a professor of agricultural-biosystems engineering, said of vertical farm systems.

Inside the lab where lettuce and basil grow in hydroponic beds under the glow of blue and red LED lights, Kacira and his students monitor the conditions in which seedlings mature.

“The environment is fully controlled in terms of providing temperatures needed, or humidity needed, carbon dioxide or the light intensity or the quality needed for the plant production,” Kacira said.

Not being at the mercy of Mother Nature makes vertical farms more productive than conventional farms, as well as more efficient at using natural resources such as water, he said. “You’re circulating it inside the environment, so the efficiency is much higher.”

Still, Kacira said, the technology is energy-intensive, given the use of artificial lights and the need to condition the environment. And although large-scale commercial operations are relatively rare, he said, advances in scientific research and the high-tech industry are making it a feasible platform to help supplement food production in cities.

“Our food transportation is coming from long distances, and by the time it gets to the consumer, especially leafy crops, the freshness may not be there,” Kacira said.

Vertical farms are a relatively new concept that hold great potential, Hardej said it. With a projected global population of 9.5 billion, mostly urban, by 2050, he views vertical farms as an increasingly important part of the world’s food system.

His own vertical farm aims to provide the Tucson and Phoenix markets with high-quality produce grown sustainably and without pesticides, Hardej said.

In time, he plans to incorporate more energy-efficient solutions into his operation.

“For commercial scale, those technologies still need to be perfected,” he said.

His company plans to begin growing the leafy greens by year’s end.

AeroFarms Raises $34m of $40m Series D from International Investors for Overseas Expansion

AeroFarms Raises $34m of $40m Series D from International Investors for Overseas Expansion

MAY 30, 2017 LOUISA BURWOOD-TAYLOR

US indoor agriculture group AeroFarms has raised over $34 million, according to a Securities & Exchange Commission Filing. The funding is the first close of a targeted $40 million Series D round.

AeroFarms grows leafy greens using aeroponics –- growing them in a misting environment without soil –- LED lights, and growth algorithms.

The round takes AeroFarms’ total fundraising efforts to over $130 million since 2014, according to AgFunder data, including a $40 million debt facility from Goldman Sachs and Prudential.

AeroFarms attracted new, international investors in this latest round, including Meraas, the investment vehicle of Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid, vice president of the United Arab Emirates and the ruler of Dubai.

The round marks the first investment for ADM Capital’s new growth stage agriculture-focused Cibus Fund, and global asset management firm Alliance Bernstein also invested. Existing investors Wheatsheaf Investments from the UK and GSR Ventures from China also joined the round.

The filing also revealed that AeroFarms had renamed its holding company to Dream Holdings, as part of its move from an LLC to a C-Corp, referencing its new retail brand Dream Greens. The Dream Greens brand hit the shelves of ShopRite, Whole Foods, FreshDirect, and Newark chain Seabras in February. Before that, the business was selling its greens into food service under the AeroFarms brand.

AeroFarms’ global list of investors is representative of its plans to expand globally, David Rosenberg, CEO, told AgFunderNews.

“We want to expand domestically and overseas, and we are excited about the potential for Meraas to help us expand into that region,” he said.

AeroFarms is not the only group to consider building indoor farms in the Middle East; Pegasus Agriculture Group, is a hydroponics-based indoor ag company that is based in Abu Dhabi, with facilities across the Middle East and North Africa. Egyptian Hydrofarms is another local example, and Indoor Farms of America recently made its first farm sale in the region.

AeroFarms also wants to add to its 120-strong team of plant biologists, pathologists, microbiologists, mechanical engineers, system engineers, data scientists and more. In particular, the company wants to add team members to its research & development department, with a view to improving the quality and operating costs of the business, according to Rosenberg. “This is where the data science and software platforms we’re using can really pull the business together.”

AeroFarms just completed construction of its ninth indoor farm, with four in New Jersey including its state-of-the-art 69,000 square foot flagship production facility in Newark. It also has plans to build in the Northeast of the US.

For more about AeroFarms, read our earlier interview with CEO David Rosenberg here.

Vertical Farms Grow Amid Skyscrapers In A Plan to Help Feed China’s Largest City

Vertical Farms Grow Amid Skyscrapers In A Plan to Help Feed China’s Largest City

Laura Brehaut | June 1, 2017 9:39 AM ET

More from Laura Brehaut | @newedist

Sasaki Associates

The hydroponic vertical farm will be dedicated to growing Shanghai staple greens such as kale, lettuce and spinach.

As Shanghai sprawls outward, architecture firm Sasaki Associates has announced plans for a farm that grows upward. The hydroponic vertical farm will be built amid the skyscrapers of China’s largest city. Like most vertical farms in use today, it will be dedicated to growing staple leafy greens such as kale, lettuce and spinach, according to Dezeen.

Space-saving is the aim of the project, Dezeen reports. Sasaki Associates intends the multi-storey farm to act as an alternative to the vast swaths of land — and associated costs — required for traditional agriculture. The project will also incorporate urban farming techniques such as algae farms, floating greenhouses and a seed library.

Vertical farms exist in cities worldwide, providing fresh produce, fish, crabs and other foods to residents in cities such as Anchorage, Berlin, Singapore and Tokyo. Advocates say that vertical farms have a reduced carbon footprint, use fewer pesticides and guzzle less water than traditional farming. Opponents argue that there are many unanswered questions about the practice, and question its economic viability.

Construction of the Shanghai project is expected to start in late 2017 as part of a new development — the Sunqiao Urban Agricultural District. The district will also feature markets, a culinary academy, interactive greenhouses and an education centre for members of the community.

Strawberry Imports May Become Unnecessary For Russia

Strawberry Imports May Become Unnecessary For Russia

It is now possible to grow strawberries all year round across Russia, from Kaliningrad to Yakutia, with a total of 6 harvests a year, as reported by agroinfo.com

The Russian company Fibonacci presented an innovative product for agriculture: the automated vertical farm BerryFarm800, which makes year-round strawberry cultivation possible.

BerryFarm800 is capable of producing 6 harvests of this delicious fruit per year, including during the winter months. The 800 sections of the agro-farm, with space for 76,800 bushes, yield 15 tonnes of strawberries a month.

Managing the farm does not require special knowledge or a lot of staff. BerryFarm800 only requires 5 people because all processes are automated.

Also, remote control of all farm parameters is possible thanks to a program developed specifically for BerryFarm800.

Another advantage of the system is that there is no need to build a greenhouse. The BerryFarm800 can operate in any ready-made commercial space: warehouses, production rooms, and so on. The farm is totally independent of climatic conditions.

Another advantage is the quick installation and the start of its operation, 2 months from the time of ordering.

The Russian company's product has no equal in the world, and according to expert assessments, it could have a significant impact on Russia's food policy. It could even make the import of strawberries completely unnecessary.

"Nowadays, in a context marked by sanctions and fierce import policies, this product is economically attractive to all consumer groups. The equipment can be delivered to any country, allowing customers to grow quality strawberries for private or commercial purposes," stated a Fibonacci representative.

Cloud Controlled Mini-Farms | AUDIO Interview - Smallhold

Cloud Controlled Mini-Farms | AUDIO Interview - Smallhold

31 May 2017

Very soon, grocery stores will be cloud-controlled mini-farms with shelves of growing produce -- according to the co-founders of the Brooklyn startup Smallhold. Hear how their ideas for vertical farming could impact your home, your supermarket and even outer space.

Click Above for Audio

We farm for you by growing produce 3/4 of the way and then deliver it to miniature vertical farm units (the size of shelving units) at your place of business to be harvested onsite as fresh, local food.

Smallhold gives you a networked farm, complete with sensors, climate control mechanisms, and hydroponics. Our horticulturalists run the farm from afar, growing for you right up until you pick and serve your produce.

From Slaughterhouse To Vertical Farm: The Plant Is Innovating In Sustainability And The Circular Economy

From Slaughterhouse To Vertical Farm: The Plant Is Innovating In Sustainability And The Circular Economy

May 30, 2017 Chuck Sudo, Bisnow, Chicago

In 1906, Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle” depicted the harsh conditions workers toiled under inside the slaughterhouses of the Union Stock Yard and Packingtown. A century later, this area that gave Chicago its brawny identity as “hog butcher for the world” is now home to several new food businesses focusing on sustainability, and The Plant in Back of the Yards is its epicenter.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow - The Plant, a vertical farm in Back of the Yards, was once a slaughterhouse.

This 94K SF former slaughterhouse was abandoned and slated for demolition when John Edel — through his company Bubbly Dynamics — bought it in 2010 and slowly repurposed the building into a vertical farm and food production business committed to a "circular economy," a closed loop of recycling and material reuse. Today, the Plant is home to several businesses where the waste stream from one business is repurposed for use by another business elsewhere in the building.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow

Whiner Beer Co. brews its beer at The Plant and opened a taproom whose bar, tables and chairs were made from reclaimed wood.

The Plant’s tenants are a who’s who of local food producers. Pleasant House Bakery is a popular company that bakes breads, desserts and Yorkshire-style meat pies that are sold wholesale at farmers markets and at Pleasant House’s Pilsen pub. Arize Kombucha distributes nearly 500 gallons of fermented probiotic tea monthly to area grocery stores. Four Letter Word Coffee, a boutique coffee roaster, has a roastery on the second floor. Whiner Beer Co. specializes in Belgian-style ales and operates a taproom inside the Plant. Justice Ice makes crystal-clear ice for use by Chicago’s best bars and restaurants for their cocktails. The Plant also has an outdoor farm, an indoor aquaponic farm that grows an average of five pounds of greens a week, an indoor tilapia farm and hatchery, a mushroom farm capable of growing 500 pounds of oyster mushrooms a month, and an apiary for making honey.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow

The Plant has an outdoor farm and an indoor aquaponics farm on the basement level.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow

With all of that happening, waste is bound to pile up. And the Plant repurposes over 90% of the waste byproducts created by its tenants. Waste from the fish farm and carbon dioxide from kombucha production is used to fertilize the greens in the aquaponics farm, which in turn filters the water that goes back to the tilapia farm. Spent grain from the brewery is used to feed the fish and for Pleasant House’s baking purposes. The Plant’s tenants even repurpose as many building materials as possible. The bar, tables and seating inside Whiner Beer Co.’s taproom was made from reclaimed wood. Pleasant House uses scrap wood to fire its ovens. Sections of the former slaughterhouse's hanging rooms (where beef and pork were processed assembly line-style and aged) are now bathrooms that comply with the Affordable Care, and other sections are being rebuilt into an information center that will open in the fall.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow

The Plant is in the process of installing a digestible aerator that will produce methane and fertilizer for The Plant's internal uses and outside uses.

The linchpin in the Plant's circular economic model is a 100-foot-long anaerobic digester. This machine is capable of breaking down biodegradable material without oxygen to create methane gas to power the Plant's electrical generation systems, algae and duckweed to feed the tilapia, produce enough process heat for use by the brewery, coffee roaster and baker, and make fertilizer for the outdoor farms. The digester is capable of producing 2.2 million BTUs of biogas. On a smaller level, the Plant is also experimenting with making biobriquettes, a hockey puck-sized brick of biomass from spent grain and coffee chaff, that can be used as fuel in the bakery's ovens instead of wood.

The Plant's circular economy has the possibility of being adapted on a larger scale. A French food engineer and Brazilian urban engineer spent their internships at the Plant analyzing material flows in order to create methodologies to determine if the Plant's closed loop system can be used for developing more efficient urban ecosystems and sustainable cities.

Related Topics: The Plant, Bubbly Dynamics, John Edel, union stock yard, packingtown, Chicago stockyards, Chicago sustainability, Chicago adaptable reuse

AeroFarms To Open World’s Largest Indoor Farm In Camden

AeroFarms To Open World’s Largest Indoor Farm In Camden

By Gillian Blair - May 30, 2017

Credit: AeroFarms

AeroFarms will soon surpass itself as the world’s largest indoor vertical farm with a second and larger New Jersey location in Camden. Set to be operational by 2018, Farm No. 10 will be 78,000 square feet on the 1500 block of Broadway. They are still working on the design of the facility and will need to gain local zoning approvals, but the biggest victory was already won when AeroFarms LLC was awarded an $11.14 million grant in tax incentives by the New Jersey Economic Development Authority.

Farm No. 9 in Newark, New Jersey, is currently the world’s largest indoor vertical farm based on annual growing capacity and where, in a converted steel mill, they harvest up to 2 million pounds a year. AeroFarms is able to germinate seeds in 12 to 48 hours–a process that typically takes 8 to 10 days–and focuses on growing leafy greens like baby kale and arugula and packaging under the name “Dream Greens” for distribution locally in North Jersey and Manhattan. Farm No. 10 in Camden will supply South Jersey and Philadelphia.

The greens are grown “aeroponically,” meaning the roots grow downward, dangle in the air, and are misted with water and minerals. And the process dispenses with premium elements like land and water: “We can grow on one acre what would normally take 130 acres on a field farm. And we use 75 percent less water [than hydroponics],” said Co-founder and CEO David Rosenberg.

AeroFarms has come far since Farm No. 1 in a converted kayak shop in Ithaca, New York, where Ed Harwood, an associate professor in the Cornell University School of Agriculture, became interested in growing things without the elements that grow things: soil, sunlight, a lot of water. Now Co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer, his biggest breakthrough was developing the root mister that doesn’t clog. Also developed for this practice of vertical farming is a cloth made of recycled soda bottles on which the seeds germinate and through which the roots grow downward.

Even the lighting is specially calibrated and everything is monitored electronically. AeroFarms recently won a “vision” award at the Global Food Innovation Summit in Milan which was an especially exciting honor as it recognizes “the coolest vision of how the world should work,” said Mr. Rosenberg.

The tax incentives enabling AeroFarms to open their second facility in Camden are part of the Grow New Jersey Assistance Program Grants which incentivize businesses to relocate or start-up in economically challenged areas, infusing the local economy, workforce, and property with capital, opportunities, and improvements.

Have something to add to this story? Email tips@jerseydigs.com. Stay up-to-date by following Jersey Digs on Twitter and Instagram, and liking us on Facebook.

The Urban Farmer: Interview With João Igor of CoolFarm

The Urban Farmer: Interview With João Igor of CoolFarm

In Future trends Posted on May 25, 2017

Created out of necessity, CoolFarm now offers smart farming solutions that allow you to plug, play, and produce fresh food all year round. Get the inside scoop on how co-founder João Igor has discovered a novel way to make agriculture an integral part of urban life.

If you haven’t heard about urban farming, you must have been living under a rock for the past few years! City-based agriculture offers the opportunity to have healthy food in abundance, at a fraction of the cost, by growing only what we need, close to home.

Urban ag startups have boomed in the last few years, offering everything from unorthodox growing setups to soil sensors, hydroponics and all manner of crop data analytics. We’ve recently spoke to João Igor of CoolFarm, a Portuguese startup operating in the smarter food and in the greenhouse sustainable agriculture area. Here’s their take on the potential for urban farming.

“I found myself suffering from health problems due to the fast food that we consume inside cities, I’ve also seen my friends and family suffering from the same issues. I wanted to do something to fight this, and I ended up in finding the right team of co-founders for this project.”

Together, we started building the CoolFarm technology in order to make farming easier and to bring fresh and nutritious food to cities, close to the people.

New Sustainable Model

CoolFarm offers indoor farming solutions for production of high quality food. Their solutions provide maximum efficiency and profitability. Their control system, called CoolFarm in/control is plant-centred. Using an intuitive dashboard, growers are able to monitor and contnrol all their farms at once, anywhere, anytime. Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms ensure optimized crop production, as well as efficient management of resources.

“We also offer to the market the CoolFarm Eye, an innovative cloud based optical sensor made to capture plants’ area and plant greenness, monitoring crops through time,” explains João. “Using the Eye, growers can make wiser and straight forward decisions to achieve the best results.”

2017 marks the launch of CoolFarm in/store, a closed and vertical system with a clean and climatized environment inside, perfect to grow premium seedlings, microgreens, leafy greens, herbs and flowers. Reportedly, it uses 90% less water than common agriculture and it does not need pesticides or herbicides. It is modular, with each module covering nearly 100 square meters of the production area.

Intelligent and highly intuitive, the system is aimed at growers, food distributors, grocery and supermarket chains, research centers, medical centers, and communities.

The system is equipped with two columns of movable hydroponic growing beds, one vertical lift, a fertigation system, topnotch sensors to measure all the variables concerning the plants, LED grow lights, CoolFarm in/control system and an antechamber.

Cities Turning Green

Throughout the world, urban farming is becoming an integral part of the urban landscape. CoolFarm is part of the booming trend. However, in order to emerge into a viable industry solution, CoolFarm needs agents and distributors worldwide, as well as adequate support from governments.

“Stakeholders must jointly address food and sustainability issues, and promote novel technologies and solutions for better farming,” says João. Although there is an urgent need for producing health, tasty, environmentally sustainable food, redesigning the agricultural system would not be straightforward.

As a creative person and as a designer my job is to build new and intuitive solutions, as well as to communicate them in the best way; as a tech guy I need to bring top notch technology, like robotics, for fields in need.

Sprouting Imaginative Solutions

The European startup ecosystem has bred numerous success stories, and CoolFarm is one of them. “We’ve gained a lot of attention, especially from the media, which is essential for any startup business trying to create brand awareness.” They also learned a lot about marketing, business, and securing funding and capital.

However, the biggest lesson, by far, is avoiding money from people that don’t understand complex markets such as agriculture.

“In general, European incubators and accelerators are good. We have excellent people behind the scene, and Europe doesn’t lack experience or knowledge.”

Apparently, launching a startup in Europe was the right decision: the team now counts nearly 20 people creating indoor farming solutions, from horticulturists and biologists, software and hardware engineers, web, mobile and product designers, marketing and business experts.

If you want a sustainable business in agriculture, avoid money from people who don’t understand such a complex market.

Early product is strong, but their roadmap is much more exciting. “We want to install the in/store solution at universities, hospitals, supermarkets, cruises, buildings,” says João, adding that they want to grasp a significant portion of the market with their new product. “The next 18 months are going to be game changing for CoolFarm. Watch and see!”

Coffee Grounds Used To Feed A Hungry City

Coffee Grounds Used To Feed A Hungry City

In an Australian first, Port Melbourne based coffee company Red Star Roasters has partnered with urban food production company Biofilta, to transform a disused Melbourne carpark into a pop-up espresso bar and thriving vertical urban food garden. The garden is converting the by-product from Melbourne's unique coffee culture coffee grounds into thousands of dollars of fresh edible produce for charity kitchens.

The Red Star Urban Garden Espresso Bar, located at The Holy Trinity Anglican Church at 160 Bay Street, Port Melbourne, features an innovative vertical food garden that uses soil made from composted green waste and coffee grounds, to grow a full range of vegetables and herbs including basil, beans, eggplant, capsicum, kale, lettuce, oregano, rhubarb, spinach, strawberries, thyme, tomatoes, zucchinis, beetroot, broccoli, bok choy and many others. Coffee grounds are collected from the espresso bar, mixed with garden clippings, cardboard packaging, soil and worms to create a rich compost onsite. The compost is then returned to the vertical gardens, to grow food. The produce is then harvested and donated to the South Port Uniting Care?s Food Pantry and Relief Service in South Melbourne. Diane Embry, the Agency's Chief Executive Officer, says, the donations enables us to provide fresh produce to people in our community who are experiencing disadvantage, social isolation and homelessness.

The garden itself is unique - with vertically stacked growing beds that are self-watering and an innovative aeration loop to keep the plants and soil oxygenated and healthy. The garden is ultra water efficient and spatially compact, and by going vertical the garden produces a large amount of food on a very small footprint, effectively doubling food yield per square metre. The vertical garden is integrated into the espresso bar coffee grounds used to feed a hungry city and café patrons are surrounded with edible gardens, aromatic herbs and flowers as they read the paper and have a coffee. In the past 12 months, the garden has produced well over 100 kilograms of vegetables and herbs from 10 square metres of garden area. However, because of the vertical design, the garden is only using 5 square metres of space. This means the garden is producing 10 kg of food per 1 sqaure metre of garden every year and at an average cost of between $5 to $10 per kg for vegetables at the Supermarket, the garden is producing $50 to $100 of food per metre square each year.

It is great having a garden that saves you money while feeding you and the family at the same time. Australia imports over 40,000 tonnes of coffee beans per annum, resulting in a huge waste stream of used coffee grounds that go to landfill. Red Star and Biofilta have worked out a way to divert this useful by-product into food to feed a hungry city and are now looking to replicate the model with cafes and restaurants who are interested in saving on food bills and growing fresh produce onsite. 100% of coffee grounds from the Red Star Urban Garden Espresso Bar are either used in the garden, or given away for free to customers to use in their gardens at home.

Creating A Zero-Coffee-Waste Café!

CEO of Biofilta, Marc Noyce said - Thousands of tonnes of coffee grounds are produced each week in Australia's cafés and restaurants, and most ends up in landfill. Red Star and Biofilta have shown how this wonderful material can be composted to soil and help feed hungry cities at the same time. Both companies are looking for more opportunities to repeat the formula with any café or restaurant who are interested in ethically sourced coffee, and have a spare space, wall, rooftop or balcony to turn.

For more information call:

Diane Falzon, Falzon PR- 0430596699

Marc Noyce, CEO, Biofilta - 0417 133 243

Chris McKiernan, Director, Red Star Coffee - 0418 136 301

Kimbal Musk Says Food Is The New Internet

Kimbal Musk Says Food Is The New Internet

Former tech entrepreneur Kimbal Musk’s ambitions for innovation in sustainable farming are as grand as his brother Elon’s for space travel and electric cars

URBAN COWBOY | Kimbal Musk at Koberstein Ranch in Colorado. “He’s got good judgment overall and has been put through the ringer a few times,” says his brother, Elon. PHOTO: MORGAN RACHEL LEVY FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE

By Jay Cheshes

May 25, 2017 10:52 a.m. ET

ON A BRISK WINTER morning, Kimbal Musk is an incongruous sight in his signature cowboy hat and monogrammed silver K belt buckle—his folksy uniform of the past few years—as he addresses a crowd outside a cluster of shipping containers in a Brooklyn parking lot. Inside each container, pink grow lights and fire hydrant irrigation feed vertical stacks of edible crops—arugula, shiso, basil and chard, among others—the equivalent of two acres of cultivated land inside a climate-controlled 320-square-foot shell. “This is basically a business in a box,” Kimbal says, presenting his latest venture to its investors, friends and curious neighbors.

Square Roots, his new incubator for urban farming, aims to empower a generation of indoor agriculturalists, offering 10 young entrepreneurs this year (chosen from 500 applicants) the tools to build a business selling the food they grow. It will take on and mentor a new group annually, with more container campuses following across the country. “Within a few years, we will have an army of Square Roots entrepreneurs in the food ecosystem,” he says of the enterprise, launched last November with co-founder and CEO Tobias Peggs—a British expat with a Ph.D. in artificial intelligence—across from the Marcy Houses, in Bedford-Stuyvesant (where Jay Z, famously, sold crack cocaine in the 1980s).

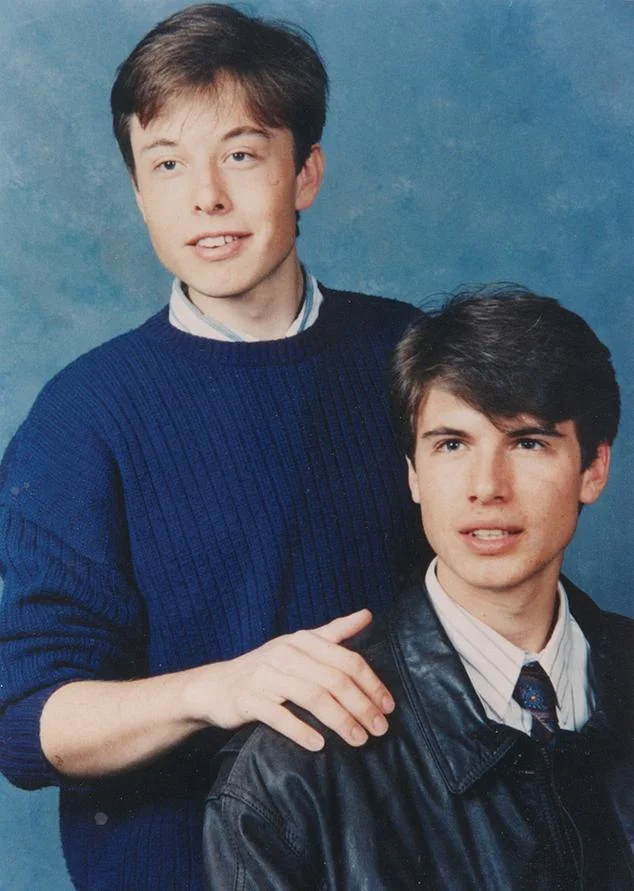

Clockwise from far left: Elon (left) and Kimbal, at 17 and 16. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIMBAL MUSK

Entrepreneurial drive runs in the family for Kimbal, 44, a close confidante of his brother, Elon, and a board member (and major shareholder) at Tesla and SpaceX. “If something happens to me, he can represent my interests,” says Elon of his kid brother (one year younger) and worst-case-scenario proxy. “He knows me better than pretty much anyone else. He’s got good judgment overall and has been put through the ringer a few times.”

Kimbal, a veteran of the tech world, has in recent years shifted his focus to food—or the “new internet,” as he called it in a 2015 TEDx Talk. With the missionary zeal his brother brings to electric sports cars and private space travel, Kimbal has launched a series of companies designed to make a lasting impact on food culture, through restaurants, school gardens and urban farms.

‘‘I want to reach a lot of people. We’ve put too much emphasis on preciousness with food.’’

—Kimbal Musk

Since 2010, a nonprofit venture supported by the Musk Foundation has built hundreds of Learning Gardens in American schools, installing self-watering polyethylene planters where kids learn to grow what they eat. Meanwhile, his Kitchen family of restaurants—promising local, sustainable, affordable food—is rapidly expanding across the American heartland, with five locations opening this year, including new outposts in Memphis and Indianapolis. Kimbal hopes to have 50 “urban-casual” Next Door restaurants, 1,000 Learning Gardens and a battalion of container farms by 2020. “I want to be able to reach a lot of people,” he says. “I think we’ve put too much emphasis on preciousness with food—and the result is a real split between the haves and have nots.”

The Musk brothers grew up in South Africa during the last gasp of the apartheid era. Kimbal, the more gregarious sibling, got his start selling chocolate Easter eggs at a steep markup door-to-door in their Pretoria suburb. “When people would balk at the price, I’d say, ‘You’re supporting a young capitalist,’ ” he recalls. While Elon spent hours programming on his Commodore VIC-20, Kimbal tinkered in the kitchen. “If the maid cooked, people would pick at the food and watch TV,” he says. “If I cooked, my dad would make us all sit down and eat ‘Kimbal’s meal.’ ”

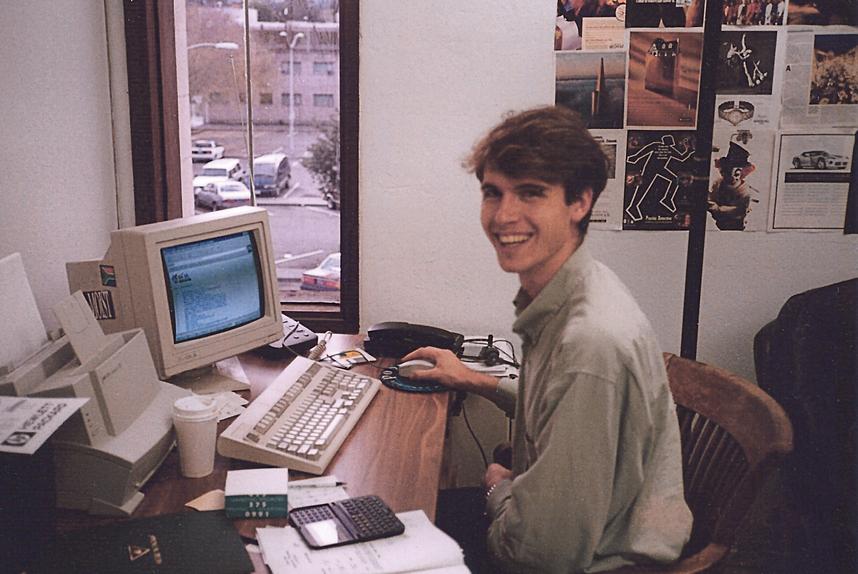

Kimbal in the kitchen, 2002. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIMBAL MUSK

After high school, the brothers moved to Canada, both enrolling, for a time, in Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario (Kimbal studied business, Elon physics). In 1995, they founded a company together in Palo Alto, California, the online business directory Zip2. “I had come over as an illegal immigrant,” Kimbal says of the move. “We slept in the office, showered at the YMCA.”

The brothers were close but also intensely competitive. Sometimes work disputes would get physical. “In a start-up, you’re just trying to survive,” says Elon. “Tensions are high.” Once they could afford it, Kimbal cooked for the whole Zip2 team in the apartment complex they shared. In 1999, the Musks sold their business to Compaq for $300 million. Though they remain investors and advisers in each other’s companies, their official partnership ended there.

HOME FRONT | Kimbal’s mother, Maye (right), with her parents at the family farm near Pretoria, South Africa, 1978. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIMBAL MUSK

After Elon launched the payment site that would later become PayPal , Kimbal, on a lark, enrolled in cooking school. He finished his studies at the French Culinary Institute in New York in late summer 2001 with no intention of pursuing a career in food. A few weeks later, after two planes flew into the Twin Towers, he spent the next six weeks as a volunteer cook, feeding firefighters out of the kitchen at Bouley. At the end of it he wanted nothing more than to open his own restaurant. “After that visceral experience, I just had to do it,” he says.

Searching for a dramatic change in scenery, post-9/11, Kimbal and his new wife at the time, lighting artist Jen Lewin, set out on a cross-country road trip looking for a place to put down roots and raise a family. They settled on Boulder, Colorado, “a walkable town, a great restaurant town,” says Kimbal at the 140-year-old Victorian home they bought there in 2002 (they have two sons and have since divorced).

The house he now shares with food-policy activist Christiana Wyly—with a cherry-red Tesla parked out back—is a few blocks from the original Kitchen, an American bistro he launched in 2004 with chef-partner Hugo Matheson, a veteran of London’s River Cafe. The Kitchen sourced ingredients from local farmers, composted food waste, ran on wind power and used recycled materials in its décor. For its first two years, the two partners worked full-time as co-chefs, taking turns composing the menu, which changed every day. Eventually, the daily grind became too much for Kimbal. “I got a little bored with the business,” he says.

Kimbal in his Zip2 office, 1996. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIMBAL MUSK

By 2006, he was back working in tech, as CEO of a social-media-analytics start-up. The Kitchen might have remained a sideline if not for a series of unlikely events. On February 10, 2010, at a TED conference in California, he listened to Jamie Oliver admonish America for its childhood obesity problem. Four days later, while barreling down a slope in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Kimbal flipped his inner tube and broke his neck. In the hospital, wondering if he’d ever walk again, he began to reconsider his life, with Oliver’s comments rattling around in his head. “The message I heard was: The people who have no excuse should be doing something about this—and I was one of those people,” says Kimbal. “I told myself, If I get through this I’m going to focus on food and doing things at scale.” Apart from losing some feeling in his fingers, he made a full recovery.

Since then Kimbal has become a cheerful crusader for “real food,” as he calls it, sharing his message on the lecture circuit. “He’s a compelling speaker,” says food writer and activist Michael Pollan. “Particularly in his passion for kids, his recognition that if we’re going to change our approach to eating in this country, it’s about showing kids where food comes from, how to grow it, how to prepare it.”

“In 2004, there were very few local farmers that would work with us,” says Kimbal. “We opened the Kitchen before farm-to-table was a term. We showed that you could be busy and profitable while creating a new supply chain. Now there’s a huge backlash against processed food, industrial food. Real food is simply food you trust to nourish your body, nourish the farmer and nourish the planet.”

Bowery Reinvents Farming for Urban Landscapes

Bowery Reinvents Farming for Urban Landscapes

May 26, 2017 by Annie Pilon In Green Business

Agriculture is one of the oldest industries out there. But businesses are still finding new ways to update this industry in order to get fresh produce to the people who need it most.

Bowery Indoor Farming

Bowery is one such business. The farming startup made its goal to get fresh produce to consumers in big cities in a sustainable way. To achieve that goal, the company uses hardware and proprietary software to set up vertically stacked gardens that operate indoors year-round.

This solves a couple of different problems. First, many city dwellers live in food deserts, or places where there isn’t a whole lot of fresh produce available. Secondly, traditional agriculture uses massive amounts of water and other resources. And Bowery’s high tech approach allows the business to function in a way that’s both sustainable and not reliant on outdoor weather.

A Great Example of Innovation

What this business shows is that you can put a new spin on almost any industry, as long as you’re willing to get a little creative. Throughout the years, people have come up with plenty of new tools to update agriculture or make certain processes more efficient. But if you’re willing to look at things in a new way, and innovate based on your observations, you can still find ways to update almost any business model.

Image: Bowery

China Subverts Pollution With Contained Vertical Farms – And Boosts Yield

China Subverts Pollution With Contained Vertical Farms – And Boosts Yield

Agriculture, China, Eat & Drink, News, Urban Farming

- by Lacy Cooke

Around one fifth of arable land in China is contaminated with levels of toxins greater than government standards, according to 2014 data. That’s around half the size of California, and it’s a growing problem for a country that faces such levels of pollution they had to import $31.2 billion of soybeans in 2015 – a 43 percent increase since 2008. Scientists and entrepreneurs are working to come up with answers to growing edible food in a polluted environment, and shipping container farms or vertical gardening could offer answers.

The toxins in China’s environment have made their way into the country’s food supply. In 2013, the Guangdong province government said 44 percent of rice sampled in their region contained excessive cadmium. Around 14 percent of domestic grain contains heavy metals such as lead, arsenic, and cadmium, according to research from scientists in 2015.

Related: Arctic town grows fresh produce in shipping container vertical garden

Could shipping container farms offer a way around this contamination? Beijing startup Alesca Life Technologies is testing them out. They turn retrofitted shipping containers into gardens filled to the brim with arugula, peas, kale, and mustard greens, and monitor conditions remotely via an app. They’ve already been able to sell smaller portable versions of the gardens to a division of a group managing luxury hotels in Beijing and the Dubai royal family.

Alesca Life co-founder Stuart Oda told Bloomberg, “Agriculture has not really innovated materially in the past 10,000 years. The future of farming – to us – is urban.”

And they’re not alone in their innovation. Scientist Yang Qichang of the Institute of Environment and Sustainable Development in Agriculture at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences is experimenting with a crop laboratory, testing which light from the visible light spectrum both helps plants flourish and uses little energy. His self-contained, vertical system already yields between 40 and 100 times more produce than an open field of similar size. He told Bloomberg, “Using vertical agriculture, we don’t need to use pesticides and we can use less chemical fertilizers – and produce safe food.”

Via Bloomberg

Images via Alesca Life Technologies