Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

LEDs For Vertical Farming: Buying Guide For Lights

LEDs For Vertical Farming: Buying Guide For Lights

Posted on June 13, 2017

Exclusive vertical farming content delivered straight to you? Sign up here.

Big Changes in Vertical Farming!

It’s easier than you think to pick the right lights for your vertical farm.

Trying to figure out the right LED lights to buy can be an overwhelming experience. There are more specs, stats, and engineering minutiae packed into product pages for LED lights than anyone running a business should have to parse through.

This article is for people who want to start their own indoor vertical farm and it’s going to drill down on the important characteristics of the lights for a business. In other words, this isn’t an exposition on the science or engineering of LEDs – despite what LED manufacturers would have you believe, you don’t need to geek out to get this right and you don’t need “cutting-edge technology.” In fact, what I want to do is try and cut through all the science and marketing-speak and put this in terms of the factors that will influence a practical business decision.

For perspective, the conclusions drawn from this piece are from a very small farm and are probably only applicable to farms costing less than $1 million (and maybe not even all of those). Once you go beyond that, some of the business decisions change. I recognize this.

I’d also note, that for our business, we’ve always had more success with going out and getting things done than staying home and planning/optimizing. These conclusions also reflect that. But hey, we’ve been making money selling our produce while people that started at the same time as us are still at home fiddling with their systems.

Before we get started, this article gives a good overview about what makes LEDs great, but my understanding of commercial lighting has increased exponentially since it was first written.

If you would like to get into the science behind this, I’d recommend the book LED Lighting For Urban Agriculture by Toyoki Kozai.

Our Test

GE, Philips, and Total Grow lights are all used in commercial farms and all come highly recommended. By using these lights, we knew they were vetted for quality and the reputation of the brands meant that we wouldn’t have to worry if their spec sheets were accurate.

For background – when selecting these lights, our plan was to originally grow a range of plants including microgreens, lettuces, and herbs and we got the same lights (***this is not what you would do if you knew what you were buying for – we were at a different stage in our business model when we made that choice***) for all of them. With these plants in mind, we knew that for everything but the neediest herbs, we wouldn’t need to go over 400 μmol/sec/m2 (this is a measure of photosynthetic photon flux per unit area, often abbreviated as PPF and is the most important metric for determining the quality of lights) and that staying lower would be better for the micros and more efficient for the lettuce.

We did 2 test runs of different loose leaf lettuce blends, started from seed under the Philips lights before finishing them off under the different brands. We controlled for light height, light amount (daily light integral)*, humidity, temperature, duration, and feeding times.

To start, here are the lighting profiles for our layout provided by the vendors.

Philips

GE

Total Grow

*While the DLI’s were slightly different, we took this difference into account when evaluating the overall values of the lights across different factors.

Yield

For us, this was the most important factor. We wanted to know if any of these lights lead to more (or better looking) food.

After harvest, we weighed our lettuce from each of the three systems and found… that the Total Grows had a small edge. The microgreens under the Total Grows looked a lot better too but we didn’t measure that accurately. As part of this, we’d also included some cheapo LEDs that were only 6000k in the experiment, though not with as many controls in place. While all three name brand lights looked better than the yields from these lights, it wasn’t by much.

Cost

This was our second most important consideration for obvious reasons. Here are the list prices for the lights we looked at (and as with anything, when you go commercial, there’s some wiggle room):

Philips: $121+/light, $726/shelf. These are the Gen 2 lights and they can be had for slightly less than this number, but you also have to buy female connectors and wiring. The price noted here reflects that.

GE: $349/light, $698/shelf. This includes clips for hanging them, jumper cables, and the pre-wired plug. And remember, these are 8 feet long.

Total Grow: $32/light, $1050/shelf. In addition to the lights, you are also paying for the socketed cord the lights plug into and you can get hanging infrastructure that I did not include the cost of here because I didn’t end up needing it.

And of course, expect to add at least another $50-$100 for shipping each product depending on how many of these you get.

Warranty And Expected Lifetime Hours

The warranty is the more important thing here in my opinion because it is what the company is actually willing to put money behind, but each are important.

Philips: 3 year warranty. 25,000 hours at 100% efficiency that gradually drops after this point (this might be true of the other lights tested, but only Philips mentioned it).

GE: 5 year warranty. 36,000 hours.

Total Grow: 5 year warranty. 50,000 hour service life.

Energy Efficiency

This turned out to be an incredibly important factor in my decision. My farm is built inside of a refurbished garage and is limited to the breaker that was already installed: 15 amps. That means I had to be able to run the whole farm on around 11 amps (both because wattage fluctuates and because I run a space heater when the exhaust fan kicks on below certain temperatures). So, the lower the amperage draw, calculated by dividing watts by volts, the greater the area I could light at a given level

The below measurements are in joules/second which is a good approximation for watts. It also applies to 1 light for each of these brands, not what is needed to light our whole shelf.

Philips: 2.17 µmole/J (x6 lights needed for our grow space)

GE: 2.33 µmole/J (x2 lights needed for our grow space)

TotalGrow: 1.3 µmole/J (and remember, we need at least 30 of these for the grow space). Another thing to note with these lights is that the housing heated up noticeably more than the other brands.

However, all of these lights were so efficient that it didn’t actually end up mattering for my space. That calculus changes the more lights you have.

Ease of Use

This ended up mattering probably a little more than it should for us compared to a mature venture. The reason for this is because we knew we were going to be moving stuff around, just kind of playing and making frequent adjustments. No one wanted to waste time fiddling with everything and more flexibility means more testing and iterating is easier down the road.

Philips: You have to wire these things yourself, which takes less than 10 minutes/light but has a learning curve that’s steeper than I would have liked requires some basic tools and a soldering iron. You could do it without the solderer, but I feel much more confident in the wiring with it. One thing to take into account when buying plugs, try and get ones that will all fit on your power strip. We didn’t think that far ahead and have some wasted outlets as a result.

We hung these with s hooks from the frame. I only feel ok about how secure they are. When we re-do the space, these will get directly mounted onto the shelves and will eliminate this problem.

GE: Super easy. Just unpack and plug in. We used s hooks into the mounting clips for these as well. That’s definitely not how they were intended to be used but we wanted to be able to move everything around and that would have been too hard if we screwed or nailed these things into our shelves (which even being able to do is another benefit of building your own shelving).

Total Grow: So you have to unbox a lot more lights which added a negligible amount of time but was still a bit of a pain. And if we were covering 10k square feet instead of 130, it might be an actual factor in terms of costing a few hours of pay to do. And once that was done, we had a rather unwieldy socketed cord to maneuver into place. This would have been much easier if we would have used their custom built mounting option (that they suggested and was well worth the price, we just switched our grow site dimensions too far along in the process) so that’s no fault of their design. Overall, not as easy as the GE lights, but definitely easier than the Philips ones.

Feeling/Durability

Philips: These have nice metal frames and thick plastic protecting the diodes and overall feel very good although one of mine buzzes loudly. I don’t know if that’s because of mishandling from previous projects, bad wiring (it was purchased and used before the others), or a fault in manufacturing.

GE: These are made of a thick plastic and overall feel a lot less durable than the Philips or Total Grow lights. I wouldn’t quite say they were fragile though. Also, being 8 ft long, they have a slight bow when not properly supported.

Total Grow: Wow. These blew me away with how solidly they were put together. In terms of durability from dropping or water, I have the most confidence in these lights by a significant amount.

Company

Philips/GE: I ended up ordering both of these through Hort Americas. Hort Americas has great customer service and worked with me to get detailed product information and talk me through the right products for my farm. They had helpful alternative suggestions and cost saving ideas.

TotalGrow: TotalGrow (Venntis Technologies) gave me some of the best customer support that I’ve ever received in my life. They will work with any farm to customize their spectrum and setup for the space and help you with your design process.

Conclusion: I would definitely encourage either ordering from Hort Americas or TotalGrow as opposed to some other web site.

Overall

To keep this from wandering too much more, I ended up choosing the GE lights for cost and energy use reasons. The fact that they were easy to install was icing on the cake.

The results of the yield test lead me to another conclusion. Pretty much any home grower or someone looking to just get a system going and tinker with it will be set with shop lights of the right spectrum. Small commercial growers should probably get a dedicated horticultural bulb, but probably don’t need to worry too much about getting the latest and greatest, because really, despite the hype, it didn’t end up making a huge difference.

I also know that the company that manufactures the TotalGrow lights has improved both the cost, energy use (by 10%), and output (10-25%) of their product so I expect them to be a much better option once their new generation of lights is out.

However… if you were to drastically increase the scale of your facility beyond what we did at Rosemont, the calculus changes. The minor yield differences suddenly start equalling thousands of dollars/year. Same for the increased electrical cost.

Still, even at that scale, I think you would be fine with any of the lights mentioned. Probably the most important factor would be the best bulk buy price you could negotiate with your distributor.

Helpful links:

https://fluence.science/science/how-to-compare-grow-lights/

http://hortamericas.com/catalog/horticultural-lighting/arize-lynk-ge-led-grow-lights/

Buy Philips GreenPower LED Grow Lights

http://totalgrowlight.com/products/broad_grow_bulb.html

From Forgotten WWII Tunnels To Urban Farm: Q&A With Growing Underground

Photo from Growing Underground

From Forgotten WWII Tunnels To Urban Farm: Q&A With Growing Underground

by Brittany Lane - Photo from Growing Underground

Today, miles of empty tunnels run beneath the streets of London. The government constructed them over one hundred feet beneath the surface to serve as shelter during the air raids of WWII. However, after the war, many of these tunnels were left abandoned. Funding to convert them into tube lines ran dry.

Over time, the spaces took on various identities – from the storage of government documents to temporary accommodations for Caribbean immigrants. One of the more recent applications, though, is breathing new life into a space once associated with a dark history.

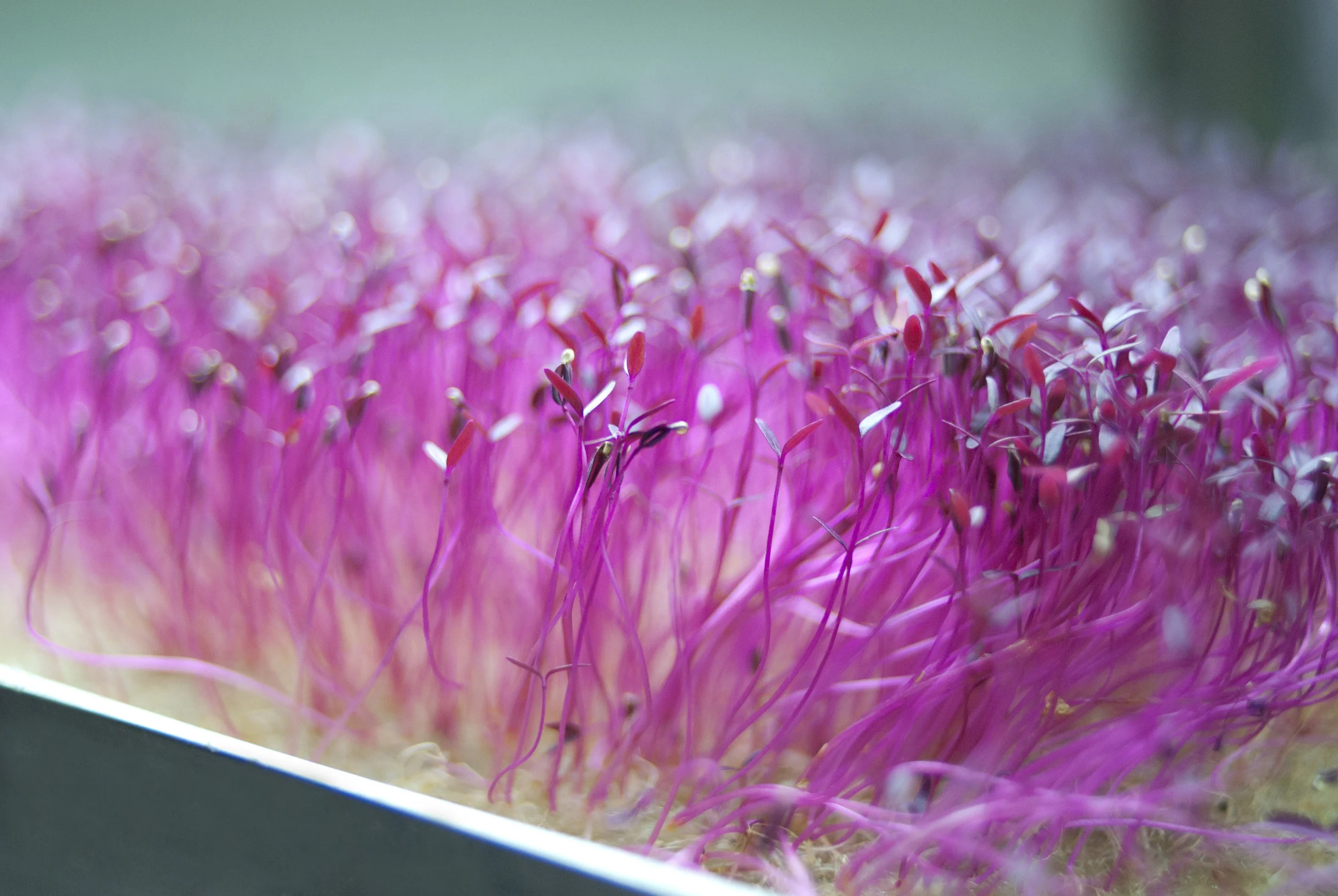

Growing Underground grows fresh micro greens and salad leaves in one of these quiet tunnels beneath the bustling streets of Clapham, South London. A combination of hydroponics and LED technology, the closed-loop farm grows crops year-round in a controlled environment with no pesticides. Due to hyper-local production, the team boasts that the produce can be in your kitchen within four hours of being picked and packed.

Unreasonable visited the underground farm and spoke with Steven Dring, co-founder of Growing Underground, about discovering the potential of urban farming and unleashing a degree of belligerence to make it succeed.

So, take me back to your corporate life. I want to hear a little bit about your journey and various work experiences along the way.

S: I worked for a PLC for 17 years, joining as a 20 year old. Literally, I was being promoted year after year. They then paid for my education as well, so there was all this buy-in and gratitude. They were a great employer in that sense. It was just the fact that I changed in terms of my views on sustainability and my views on where we were going as a planet. So as I was changing, the bits within the business that really didn’t sit with me just became more pronounced.

I can remember the moment when I sat in my office and I received a letter that said, “Your pension matures in 2039,” and I thought, no it doesn’t! That was a catalyst. So yeah, I quit.

I heard something about a suit-burning party…what was that all about?

S: That entailed me bundling all my suits together – leaving only a brown one for summer, a dress one for black tie, and a blue one for the city. Everything else got carried to a big oil drum that was in our garden, where we burned leaves and things like that. I may have had an alcoholic drink in my hand and, yeah…I put on an accelerant and enjoyed the flame.

Tell me about how Growing Underground got started.

S: Richard, my business partner, and I literally grew up in villages next to each other, right in amongst agriculture on the edge of the city where the countryside starts. So we knew about farming and agriculture and the pressures of that.

Did you know anything about this type of growing or farming?

S: Not at all. Years later, when Richard moved to London, this idea evolved. Usually on Friday nights, Rich would come down near where I lived and we’d go to a local pub and end up arguing for hours. We had many conversations about the democratization of energy and water scarcity and growing populations – we were that boring in the pub.

We are taking a space that really had a lot of negative connotations and turning it into something much more powerful. Tweet This Quote

But when Richard said there’s this thing called vertical farming, we looked into the academia behind it, and it stacked up. This was opening my eyes at a time when I was thinking I needed to do something different. One night in the pub it was, OK, let’s stop talking about it, and let’s do something about it. And Richard said, well can you actually try and throw that into a business case?

But what became apparent at that point was that we knew sod all about growing. We needed to get somebody around us. We found an LED supplier in Finland just from Google research, and next thing you know, a guy named Chris came through. He went back to his wife in Yorkshire and said, these guys are trying to build a farm underground. And she just thought it was a massive wind-up. But, we brought Chris in as a founder of the business within two weeks of taking the whole thing seriously.

So what gave you the courage and passion to just go after this?

S: I think the reason to go at it was the business case. We did two years of planning and research to understand the market and spent sleepless nights going to talk with the traders down at the food market. We sat in the British Library reading reports to understand fresh produce. It was a case of right, if we’re going to ask people for a million pounds for an idea, then we kind of need a fairly robust business plan. So, that’s what we did – two years of business planning.

I’d always made profit for people all my life. I thought we could affect the most change by showing everybody the financial dividend and a reason to invest in this market, as well as all of our sustainable and social goals we wanted to achieve. I thought we could do both and do things quicker if we weren’t a not-for-profit. Richard and I argued about it, and we struggled with all of that to start, but then I won the argument.

If we can show people that you can invest in a sustainable venture and make a return, and you’ve got a social and sustainable dividend as well, then shouldn’t we all be doing that?

Tell me a brief history about these tunnels. They have clearly undergone a massive transformation from a previous time in human history.

S: It was built as a WWII air raid shelter. I think the plans were drawn up in 1939, and they were finished building in 1941. You look at the engineering that’s gone on down here – the blood, sweat and tears it would have taken to build this space, and then the fact that it housed people whilst London was being bombed – it’s kind of mind-blowing what took place.

We need to show the investment community that sustainable businesses are the future. Tweet This Quote

I struggle to get my head around the concept of being housed down here with 8,000 other souls. It’s gone through a strange life, this building. Then, it sat here empty. We are taking a space that had a lot of negative connotations and turning it into something much more powerful.

When you discovered the tunnels, do you remember realizing the potential opportunity here? What did that feel like?

S: I remember the phone call to the guy at Transport for London when I said we want to meet and rent your tunnels. He was like, “You can’t do a nightclub.” We said we don’t want to; we want to build a farm. And I think at that point he was like, what? He literally came out a couple of days later and met us. They were really forward thinking and supportive.

Tell me more about the space you’re using for farming down here.

S: So we’ve got a huge space, at least 70,000 square feet, and we’re using a tiny portion of that so far. The good thing for us is expansion is just building another section of farm. I don’t need a new building. This came from Chris and other advisors around us saying, if you are going to do this, you need to do it on a commercial scale. Otherwise, you’re just going to be a market garden. Like, you really need to be able to get your economics right. So that was the reason for going somewhere big like this.

The four levels of the underground farm. Photo from Growing Underground.

Right now, we grow on four layers. When we’re maxed out, it’s going to be a couple of hectares of growing space down here. And then it’s two linear tunnels: one would have been the northbound tunnel and the other the southbound tunnel (each a half kilometer long) if they ever turned it into the tube. That’s what’s was genius about the build, actually, the fact that they realized the war was going to be over one day, and they would turn it into a tube line. They never did because they never found the money, so we turned it into a farm.

Can you give me a brief overview of how this whole process works?

S: It’s really easy. You throw around some seeds, stuff grows, and we sell it. It’s just very straightforward. A substrate, which is a recycled carpet, acts as our soil. The guys scatter the seeds on there in a uniform way. Then, we take that product and put it into propagation, which is basically just high humidity in the dark. That acts like the product is underneath the soil, so we just recreate that environment, keeping it a constant 25-30 degrees Celsius.

From there, the roots start to take hold in the substrate. At that point, we move them underneath the lights, and they stay under the lights from 6-20 days, depending on what you’re growing. Then, it comes out for cutting. We pack it, put it in the fridge, and it goes out 4-12 hours later.

Packing micro greens and getting them ready to distribute. Photo from Growing Underground.

So that’s the process. We take LED lighting and hydroponics, put them together, and use them to grow fresh produce. Hydroponics has been around since the Roman times if not before. In the 70s in this country, it was perfected as a commercial and efficient way of growing crops. And so we’ve not really done anything revolutionary apart from all that’s evolved in LED lighting.

Where does the produce go when it’s packed and ready?

S: At the moment, it goes into the wholesale markets, and that goes out to thousands of restaurants across London. We currently have an online offer as well and one at a farmer’s market. In the future, there will be retail offers, which is the large mover of produce.

And what types of micro greens do you grow?

S: We actually grow a mix of micro greens and baby leafs. So baby leafs are like mizuna, pea shoots, and red oak lettuce – all leafs that you find in a standard pack of salad. Then, for the micro herbs, we grow fennel, green and red basil, coriander, celery, and parsley. Chefs like them because you’ve got real intense flavors, but they don’t dominate the plate.

Micro greens up close. Photo from Growing Underground.

How does it compare to other produce? What makes it stand out from anything these chefs have used before, for example?

S: What makes us stand apart from our competitors is the speed of transit to get produce to the market. By the time it gets to the customer, it still has its intense flavor, and the shelf life is longer. The chefs like the security of the supply chain. It’s secure because of where we grow it, but it’s also the consistency. Because of this environment, there aren’t variations in quality.

The game changer for us will be when we start to put a product through retail and hit volume. That’s when we start to get to more ubiquitous and affordable products, which is what you want to be able to do in terms of feeding more people. Not everybody eats micro herbs. I don’t take a pack of 30 g of coriander home on an evening and use them, you know – that’s a lot of coriander.

London’s going to have another 2 million people by 2025 alone. We have to feed them. Tweet This Quote

But when you start putting that into retail and supplying to the masses, then you can affect more change. Then, we start taking food production from the rural into the urban environment. But we’re never going to do that with just micros. We’re trying to do something quite noble in terms of food production, but the product we grow at the moment goes to high-end chefs and catering. Inevitably, there’s a massive dichotomy between the two, so we have to be honest about the fact of where that product is going now.

Why have urban farms? Why is it so important to have farms underneath London?

S: So there are loads of reasons for urban farms. The first one, the argument that Richard and I started with, is the growing population. The UN says there’s going to be billions of people by 2050, and London’s going to have another 2 million people by 2025 alone. We have to feed them. Where is the energy going to come from? Where is the water going to come from?

Then, you look at agriculture. Actually, we can get yields up and do it sustainably. It’s just a case of taking all the best practices from agriculture and saying, well we don’t want agricultural runoff, and hydroponics uses 70 percent less water. So that was the case for urban farms.

But then, you get the locality of it. In terms of proximity to the distribution markets, it’s right on your doorstep. You not only have the connection with the local community and the creation of jobs, but you also have a connection between grower and consumer. Over the long term, things like salads can grow really close to where they’re consumed, freeing up the rural environment to produce food for a growing population.

Tell me about the struggles.

S: Many times a day, I think that I don’t know how to do this. There are many different struggles you go through. I think elements of the bureaucracy are always a challenge, and attracting investors to an emerging sector is always a challenge, and they cause you frustration. But you have to have a certain amount of belligerence to say, “We’re going to build a farm in a tunnel, and that’s it.” Rich and I sat on many occasions and just said, yeah, just be belligerent about it.

What do you hope your business will do for future generations?

S: I’d like to see us expand our operations into many different areas in the UK and other geographies. I’d like to see us have an impact in terms of job creation, and I’d also then like to show that investing in the sustainable sector is right and good. We need to show the investment community that sustainable projects and businesses are the future. I think once they get on board with that, then change will happen a lot quicker.

We’re using food as something to break down barriers and engage in your local community. Tweet This Quote

We are pushing back against something that’s really significant in terms of global climate change, sustainability, and just socially how we treat each other. We’re using food as something to break down barriers and engage in your local community, rather than just being a producer in the middle of nowhere, and your produce ends up on a shelf in front of me in a supermarket. We’re trying to change all elements of that.

So entrepreneurship is hard. The food industry is also hard to break into. How do you wake up every day inspired to keep going for it?

S: At the start, what got me out of bed every day was how terrible the food system was. Now, it’s possibly a belligerence to make it a success – whether it’s about job creation, the social end of the business, or the financial dividend. I think it’s something about wanting to make sure you affect the change you want.

You have to have a certain amount of belligerence to say, we’re going to build a farm in a tunnel. Tweet This Quote

We don’t take no for an answer, and we are stubborn. But a thing someone said to me ages ago was that obviously you’re going to have competitors. Just make sure they know you’re having way more fun than they are. And I was like, yeah, that’s the attitude to embrace. You have a choice of an attitude in the morning when you wake up. You can go at it being a miserable sod, or you can go at it saying, “Well, OK, let’s do it!”

So, yeah there’s belligerence, but there’s also a great group of people to pick you up when you’re having a bad day, who you can have a laugh with, and who are trying to do something different in the right direction.

This company participated in Unreasonable Impact created with Barclays, the world’s first multi-year partnership focused on scaling up entrepreneurial solutions that will help employ thousands while solving some of our most pressing societal challenges.

LumiGrow Brings Smart Horticultural Lighting to FreshTEC Expo

LumiGrow Brings Smart Horticultural Lighting to FreshTEC Expo

McCormick Place, Chicago, USA – June 13, 2017 – LumiGrow Inc., the leader in smart horticultural lighting, will be premiering their LED lighting and software suite at this year’s United FreshTEC Expo for the first time in Chicago on June 13th to 15th.

“United FreshTEC is the only show focused on innovation in fresh foods technologies, so we feel it’s crucial to be present so growers have a trusted lighting resource to engage when considering new technologies,” explains Jay Albere, VP of Sales and Marketing at LumiGrow. “Light has such profound ability to boost food production performance, that when growers adjust other variables it’s always important to discuss how these changes will affect your lighting strategy. We’re really here to be a resource for growers looking to maximize their production potential.”

The United FreshTEC Expo highlights technologies beyond LED lighting automation, addressing other operational automation strategies, field harvesting and packing technologies, supply chain management, and food safety.

LumiGrow is located at the FutureTEC Zone, an area dedicated to the most innovative solutions for improving operations, tools, and services. “Our LumiGrow lighting specialists look forward to answering any questions you may have, and give guidance as you implement advanced technologies into your operation.” says Jay Albere. “Feel free to visit us at Booth FTZ48 and we’ll be happy to speak with you.”

About LumiGrow Inc.

LumiGrow, Inc., the leader in smart horticultural lighting, empowers growers and scientists with the ability to improve plant growth, boost crop yields, and achieve cost-saving operational efficiencies. LumiGrow offers a range of proven grow light solutions for use in greenhouses, controlled environment agriculture and research chambers. LumiGrow solutions are eligible for energy-efficiency subsidies from utilities across North America.

LumiGrow has the largest horticultural LED install-base in the United States, with installations in over 30 countries. Our customers range from top global agribusinesses, many of the world’s top 100 produce and flower growers, enterprise cannabis cultivators, leading universities, and the USDA. Headquartered in Emeryville, California, LumiGrow is privately owned and operated.

For additional information, call (800) 514-0487 or visit www.lumigrow.com.

Vertical Farming Gets Real: Bowery Farming Raises $20M For Its 'Post-Organic' Warehouse Farm

As indoor farming goes from fantasy to reality, Bowery Farming raised $20 million for its “post-organic” vertical farm from a group of investors, including General Catalyst, GGV Capital and GV (formerly Google Ventures), better known for betting on technology than on agriculture.

Vertical Farming Gets Real: Bowery Farming Raises $20M For Its 'Post-Organic' Warehouse Farm

Amy Feldman , FORBES STAFF - I write about entrepreneurs and small business owners.

Bowery Farming co-founder and CEO Irving Fain: "We are a tech company that is thinking about the future of food." Courtesy of Bowery Farming

As indoor farming goes from fantasy to reality, Bowery Farming raised $20 million for its “post-organic” vertical farm from a group of investors, including General Catalyst, GGV Capital and GV (formerly Google Ventures), better known for betting on technology than on agriculture.

The new financing, announced this morning, brings Bowery’s total take to $27.5 million. The company declined to disclose valuation, but it’s clearly a big bet on something that for many years had been little more than a dream. “We are a tech company that is thinking about the future of food,” says Bowery’s co-founder and CEO Irving Fain.

Bowery’s indoor farming – its first farm is in a Kearny, N.J., warehouse – relies on proprietary computer software, LED lighting and robotics to grow leafy greens without pesticides and with 95% less water than traditional agriculture. By locating near cities, indoor farms, like Bowery’s, can also cut the transportation costs and environmental impact of getting food to an increasingly urban population. And by controlling its indoor environment, Bowery can produce its greens 365 days a year. The result: Bowery can produce 100 times more greens than a traditional outdoor farm occupying the same-sized footprint.

With the global population rising at breakneck speed, farmland shrinking, and increasing numbers of people moving to urban areas, the idea of creating vertical farms in cities that would produce food more efficiently has long been a dream. Dickson Despommier, an emeritus professor of biology at Columbia University, had long promulgated this idea (as I wrote about a decade ago in Popular Science). But it’s only recently that technological advances in both data analytics and LED lighting have allowed such an approach to be done at scale.

“We think the industry is more or less near an inflection point,” says GGV managing partner Hans Tung. “It is no longer just a pie-in-the-sky theory. It has the chance to scale in the next five years.”

Fain, 37, who started his career as an investment banker at Citigroup, ran marketing at iHeartMedia and co-founded CrowdTwist, which provides loyalty marketing software for major brands, before turning to food. In October 2014, he teamed up with David Golden, who had previously cofounded and run LeapPay, and Brian Falther, who had worked as a mechanical engineer in automotive manufacturing. They began looking at the ways technology might enable better farming. “Industrialized farming is not sustainable,” Fain says. “I became really obsessed with how do you provide fresh food to those urban environments in a way that is more sustainable and more efficient.”

Bowery raised its first financing from First Round Capital, Box Group, Lerer Hippeau Ventures, Blue Apron CEO Matt Salzberg, and chef Tom Colicchio, whose restaurants Craft and Fowler & Wells have Bowery’s greens on the menu. The company has tried growing 100 different crops in its Kearney warehouse farm, and currently sells six varieties of leafy greens, including butterhead lettuce and baby kale, to Whole Foods and Foragers markets. Pricing is similar to organics, at $3.99 for a 5-ounce container.

Advances in LED lighting have enabled indoor farming to be done at scale.

Courtesy of Bowery Farming

Bowery isn’t the only one to try to do vertical farming at scale. Competitors including AeroFarms and Plenty United, which are also farming indoors with the capacity to produce millions of pounds of greens. AeroFarms has raised more than $100 million for its indoor farms, while Plenty United counts billionaires Jeff Bezos and Eric Schmidt among its backers.

Technological advances from data analytics to robotics have enabled vertical farmers to turn old warehouses and steel factories to new, agricultural uses. Bowery Farming uses its own BoweryOS proprietary software program to analyze millions of data points that can impact a plant’s growth rate or flavor. Meanwhile, all indoor farms have benefited from advances in LED lighting, which can mimic natural sunlight. Pot farmers have used LED lights to grow their plants, but relying on LED lighting for industrial-scale farming has only become possible as the cost has come down. “The fundamental change is what’s happened in LED lighting,” Fain says. “The cost of the fixtures dropped by over 85%, and the efficacy of the fixtures doubled, so what had been possible only in labs became possible in a commercially viable way. Without that trend, you couldn’t have done this.”

With the new funding, Fain says, Bowery plans to hire more people (it currently has just 12 employees), to set up additional farms (first in the tri-state area and then near other cities across the U.S.), and to move beyond leafy greens to other types of produce that could be farmed indoors. Longer term, the big opportunity may be further afield, in China and other emerging markets, where populations are massive, and food security is a hot topic. Says Tung: “This will scale beyond the U.S. to other emerging markets. It is definitely needed.”

Follow me on Twitter @amyfeldman

Philips Lighting Begins Largest LED Horticultural Lighting Project in The World

Philips Lighting Begins Largest LED Horticultural Lighting Project in The World

June 14, 2017

- LED grow lights will illuminate greenhouses occupying an area the size of 40 soccer pitches

- Project indicative of trend for large-scale horticultural LED lighting projects supporting domestically grown produce

Eindhoven, the Netherlands – Philips Lighting (Euronext Amsterdam ticker: LIGHT), a global leader in lighting, today announced that it will provide LLC Agro-Invest, Russia’s most innovative greenhouse produce company, with LED grow lights to support cultivation of tomatoes and cucumbers in greenhouses covering an area of more than 25 hectares (equivalent in size to about 40 soccer pitches). The project, which is the largest LED horticultural lighting project ever undertaken, will enable year-round growing, help boost yields - especially in the winter - and will save 50 percent on energy costs compared to conventional high-pressure sodium lighting. The project also underlines a global trend for large-scale LED horticultural lighting implementations that can support demand for locally grown produce.

Philips Lighting is working with Dutch partner Agrolux and Russian installer, LLC ST Solutions, which will equip greenhouses in Lyudinovo, Kaluga Oblast, 350 km south west of Moscow, during the next three months. Philips Lighting will provide ‘light recipes’ optimized for growing tomatoes and cucumbers, training services and 65,000 1.25m long Philips GreenPower LED toplights and 57,000 2.5m long Philips GreenPower LED interlights. Laid end to end, they would stretch 223 km, the equivalent of crossing the English Channel from Dover to Calais more than five times.

“We have a reputation for innovation on a large scale and LED grow lights are definitely the future. They deliver the right light for the plant, exactly when and where the plant needs it the most, while radiating far less heat than conventional lighting. This allows us to place them closer to the plants,” said Irina Meshkova, Deputy CEO and General Director, Agro-Invest. “Thanks to this technology we will be able to increase yields in the darker months of the year, and significantly reduce our energy usage,” she added.

“This LED horticultural project is the largest in the world. It will reduce the electricity consumed to light the crop by up to 50 percent compared with conventional horticultural lighting and uses light recipes designed to boost quality and crop yields by up to 30 percent in the dark period of the winter,” said Udo van Slooten, business leader for Philips Lighting’s horticultural lighting business. “Our grow lights are the perfect supplement to natural daylight so that crops can be grown efficiently throughout the year. The project also highlights a growing international trend to replace imports with domestically grown produce, reducing food miles and ensuring freshness,” he added.

About Agro-Invest

LLC Agro-Invest is Russia’s most innovative greenhouse produce company. Its 43 hectare modern greenhouse complex grows more than 15 varieties of vegetables with an annual production capacity of 25,000 tons. The company acts ecologically, collecting rainwater to water the plants which are pollinated by bees from special beehives within the greenhouse complex. The latter helps improve harvests by 20-25 percent. Protection of the plants is undertaken by natural biological methods. Since 2016, Agro-Invest has sold and marketed its produce under the “Moyo Leto.” trademark. The company works with all the federal trade networks in the Russian Federation and is expanding its operations.

About Agrolux

Agrolux is a worldwide supplier of assimilation lighting for horticulture. It is the biggest dealer in Philips LED horticultural lighting worldwide. It distinguishes itself based on advice, service and quality. It also produces its own luminaires and exports them to clients worldwide. The company’s broad knowledge, extensive experience and innovative technology, make it stand out as a leader in the horticulture sector. It combines good, honest advice with the fast and dependable delivery of lighting luminaires and parts. Established in 2002, Agrolux has grown in size and production numbers annually. Its employees come from diverse sectors within horticulture and offer a wealth of practical experience, providing the best advice and most efficient lighting for horticulture.

For more information on Philips horticultural lighting: www.philips.com/horti

For further information, please contact:

Philips Lighting, Global Media Relations

Neil Pattie | Tel: +31 6 15 08 48 17 | Email: neil.pattie@philips.com

Philips Lighting Horticulture LED Solutions

Daniela Damoiseaux | Tel: +31 6 31 65 29 69 | Email: daniela.damoiseaux@philips.com

About Philips Lighting

Philips Lighting (Euronext Amsterdam ticker: LIGHT), a global leader in lighting products, systems and services, delivers innovations that unlock business value, providing rich user experiences that help improve lives. Serving professional and consumer markets, we lead the industry in leveraging the Internet of Things to transform homes, buildings and urban spaces. With 2016 sales of EUR 7.1 billion, we have approximately 34,000 employees in over 70 countries. News from Philips Lighting is located at http://www.newsroom.lighting.philips.com and on Twitter via @Lighting_Press.

The Future of Farming May Not Involve Dirt or Sun

Farming uses copious amounts of water--70 percent of all freshwater consumed is used for agriculture, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, only about half of which can be recycled after using. It also requires huge swaths of land and, of course, just the right amount of sun. AeroFarms thinks it has a better solution.

AeroFarms co-founders Marc Oshima (left) and David Rosenberg.CREDIT: Ellise Verheyen

The Future of Farming May Not Involve Dirt or Sun

New Jersey-based AeroFarms proposes a radical and more sustainable way to grow the world's food.

By Kevin J. Ryan Staff writer, Inc.@wheresKR

COMPANY PROFILE

COMPANY: AeroFarms

HEADQUARTERS: Newark, NJ

CO-FOUNDERS Marc Oshima, David Rosenberg, Ed Harwood

YEAR FOUNDED: 2011

MONEY RAISED: More than $100 million

EMPLOYEES: 120

TWITTER: @AeroFarms

WEBSITE: aerofarms.com

Farming uses copious amounts of water--70 percent of all freshwater consumed is used for agriculture, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, only about half of which can be recycled after using. It also requires huge swaths of land and, of course, just the right amount of sun.

AeroFarms thinks it has a better solution. The company's farming method requires no soil, no sunlight, and very little water. It all takes place indoors, often in an old warehouse, meaning in theory that any location could become a fertile growing ground despite its climate.

The startup is the brainchild of Ed Harwood, a professor at Cornell University's agriculture school. In 2003, Harwood invented a new system for growing plants in a cloth material he created. There's no dirt necessary--beneath the cloth, the plants' roots are sprayed with nutrient-rich mist. Harwood received a patent for his invention and founded Aero Farm Systems, so named because "aeroponics" refers to the method of growing plants without placing them in soil or water. The company, which sold plant-growing systems, was mostly a side project for Harwood and didn't generate much revenue.

AeroFarms uses LED lighting to create a light recipe for each plant.CREDIT: Ellise Verheyen

In 2011, David Rosenberg, founder of waterproof concrete company Hycrete, and Marc Oshima, a longtime marketer in the food and restaurant industries, looked at the inefficiency of traditional farming and sensed an opportunity. The pair began exploring potential new methods and, in the process, came across Aero Farm Systems. They liked what Harwood had developed--so much that they offered him a cash infusion in exchange for letting them come on board as co-founders. They also proposed a change in business model: Rosenberg and Oshima saw a bigger opportunity in optimizing the growing process and selling the crops themselves.

Harwood agreed. The company became AeroFarms, with the three serving as co-founders. The trio bought old facilities in New Jersey--a steel mill, a club, a paintball center--and started converting them into indoor farms.

Today, each of the startup's farms features vertically stacked trays where the company grows carrots, cucumbers, potatoes, and, its main product high-end baby greens, which it sells to grocers on the East Coast including Whole Foods, ShopRite, and Fresh Direct, as well as to dining halls at businesses like Goldman Sachs and The New York Times. By growing locally year-round, the company hopes it will be able to provide fresher produce at a lower price point, since transportation will be kept to a minimum. (Currently, about 90 percent of the leafy greens consumed in the U.S. between November and March come from the Southwest, according to Bloomberg.) AeroFarms collects hundreds of thousands of data points at each of its facilities, which allows it to easily alter its LED lighting to control for taste, texture, color, and nutrition, Oshima says. The data also helps the company adjust variables like temperature and humidity to optimize its crop yields.

The result, according to AeroFarms, is wild efficiency: The growing method is 130 times more productive per square foot annually than a field farm, from a crop-yield perspective. An AeroFarm uses 95 percent less water than a field farm, 40 percent less fertilizer than traditional farming, and no pesticides. Crops that usually take 30 to 45 days to grow, like the leafy gourmet greens that make up most of the company's output, take as little as 12. Oshima claims that its newest farm, which opened in Newark in May, will be the world's most productive indoor farm by output once it reaches full capacity. Currently, AeroFarms' greens retail for around the same price as similar gourmet baby greens.

AeroFarms employee Samentha Evans-Toor checks the plant growth in a Newark, New Jersey, facility. CREDIT: Alex Kwok

"Most farms don't have a chief technology officer," Oshima says. "We have a dedicated R&D center, plant scientists, microbiologists, mechanical engineers, electrical engineers. We've done our due diligence to create this."

To be sure, as innovative as AeroFarms might be, it's not exactly a practical solution for replacing the world's farms. One big problem is that indoor farming requires huge amounts of electricity, which is not only costly but also offsets much of the good done by preserving water because of the large carbon footprint it creates. AeroFarms acknowledges the drawback but says that it's working to address the problem. The company hired Roger Buelow, the former chief technology officer of LED lighting company Energy Focus, who helped design AeroFarms' customized LED lighting system. "That allows us to be much more energy efficient than anything else out there," Oshima says.

Another challenge AeroFarms faces as it tries to grow is simply scaling the necessary expertise to run these farms. Dickson Despommier, a microbiologist and professor emeritus at Columbia University, first started experimenting with vertical farming--a term that he's widely credited with coining--in 2000. Despommier says that successfully running a vertical farm requires extensive agricultural and process knowledge, which in the case of AeroFarms is provided primarily by Harwood. "Some people think you can just read a book and find out how to do this," Despommier says. "You can't."

That steep learning curve, he says, can create obstacles for companies in this industry. "The biggest issue is finding people who are qualified," he says. "Growers in particular are very hard to find. Who's training them? The answer is, very few places." In the U.S., the University of Arizona, University of California, Davis, and the University of Michigan are among the few institutions that offer courses in vertical farming.

At AeroFarms, that issue is magnified thanks to Harwood's patented growing medium. "No one has direct experience with this," Oshima says. Once the startup finds candidates it trusts to learn the growing process, it has to train them and teach them the company's more than 100 best operating procedures.

AeroFarms' finished product "Dream Greens."CREDIT: Alex Kwok

The company employs 120 people. It has raised more than $100 million to date, from firms including Goldman Sachs and GSR Ventures. Other companies, like Michigan-based Green Spirit Farms and California-based Urban Produce, also sell to consumers using vertical farming methods, though The New Yorker reported in January that AeroFarms had twice the funding of any other indoor farming company--even before its recent $34 million round.

AeroFarms sees its growing method as especially useful in areas where the climate might not be friendly to growing, or where water or land is sparse. The startup currently has nine farms, including locations in Saudi Arabia and China. It plans to reach 25 farms within five years.

"From day one," Oshima says, "this has been about having an impact around the world."

PUBLISHED ON: JUNE 14, 2017

Leading US Indoor Agriculture Firm Partners to Offer First-of-its-Kind Alternate Financing for Indoor Growers

Leading US Indoor Agriculture Firm Partners to Offer First-of-its-Kind Alternate Financing for Indoor Growers

Contain Inc partners with AmHydro, Bright Agrotech & CropKing to offer lease financing for indoor agriculture and vertical farming equipment

Our goal is to become the alternate finance provider of choice to indoor farmers” — Nicola Kerslake, Co-Founder, Contain Inc.

RENO, NV, UNITED STATES, June 13, 2017 /EINPresswire.com/ -- Indoor agriculture - the practice of raising crops in warehouses, containers and greenhouses using hydroponic, aquaponics and aeroponic techniques - is one of the fastest-growing parts of global farming. To date, indoor farmers have lacked the same access to capital enjoyed by their outdoor peers, and one of the industry’s leading firms, registered investment adviser Newbean Capital, is now focused on remedying that inequity.

It has launched an alternate finance arm, Contain Inc., its first offering is lease financing. “Our goal is to become the alternate finance provider of choice to indoor farmers”, said Nicola Kerslake, co-founder of Contain Inc.

The venture has partnered with three leading indoor agriculture technology providers to provide lease financing to their customers. For longstanding industry consultant AmHydro, it will offer lease financing for the Company’s Get Growing!™ greenhouse bundle packages. AmHydro has been designing and building innovative, hydroponic systems for over 30 years. It manufactures and helps to install food-grade growing systems for both small and large commercial operations. AmHydro offers systems for the small business entrepreneur up to the large multi-acre commercial suppliers of companies such as Whole Foods and Costco.

Contain Inc has recently arranged a five-year lease agreement for Bright Agrotech’s ZipFarmTM equipment at a 6.5% rate for MyChoice Programs, an East coast nonprofit that supports individuals with developmental disabilities to participate in their communities. As one of its innovative programs, it decided to transform a building into a vertical farm that could feed both the residents of its homes and the local community using Bright Agrotech equipment. Bright Agrotech designs and builds the most installed vertical farming technology in the world. They revolutionized the indoor farming industry with vertical plane growing tech, system controls and workflow designs that help hundreds of farmers be more productive.

Its newest partner - CropKing - a manufacturer and distributor of commercial greenhouse structures, hydroponic growing equipment, and supplies. Known for working with family farms, it has specialized in the business of controlled environment agriculture and hydroponic growing since 1982. It offers both bucket and NFT systems for indoor grows.

About Contain

Contain is an alternate finance business that works exclusively with indoor growers, those that are farming in warehouses, greenhouses and containers. It partners with industry-leading equipment providers to secure lease financing for indoor farming equipment, such as greenhouses, grow systems, controls systems and LED lighting. It also offers insurance through its partner at Interwest.

More Information

• Contain Inc. – contain.ag

• AmHydro – amhydro.com/financing

• Bright Agrotech – brightagrotech.com

• CropKing – cropking.com

• MyChoice Programs - mychoiceprograms.com

Nicola Kerslake

Contain Inc.

7756237116

Vertical Farming Startup Plenty Acquires Bright Agrotech to Scale

Vertical Farming Startup Plenty Acquires Bright Agrotech to Scale

California-based vertical farming company Plenty, previously See Jane Farm, has acquired Bright Agrotech in an effort to reach “field-scale.”

Bright Agrotech is an indoor ag hardware company that’s focused on building indoor growing systems for small farmers all over the world, in contrast to Plenty, which is aiming to become a large-scale indoor farming business and currently has a 52,000 sq. ft farm in South San Francisco.

“The need for local produce is not one that small farmers alone can satisfy, and I’m glad that with Plenty we can all work toward bringing people everywhere the freshest food,” said Nate Storey, founder and chairman of Bright Agrotech.

The move to acquire Bright Agrotech will give Plenty the breadth of expertise and intellectual property (IP) to scale with rapid speed, and is a natural move after a four-year relationship, according to Matt Barnard, cofounder and CEO.

“We have a great portfolio of system level IP. They have a great portfolio of component level IP,” he told AgFunderNews. “We’re getting a fire hose of demand from around the globe right now. This is an industry that is emergent, but the way to truly lift it off the ground is to do a whole set of things extraordinarily well.”

Bright Agrotech was founded in 2010 in Laramie, Wyoming, and sells a wide range of indoor farming equipment for indoor vertical farms as well as greenhouses along with smaller systems suitable for homes and business development tools – most of which are under the trademark brand “ZipGrow.”

The relationship between the two businesses started in 2013. Later Storey, the former CEO of Bright Agrotech, became chief science officer at Plenty in a part-time capacity in 2015 and went on to join the team full time earlier this year.

Barnard would not confirm to what extent Plenty already uses Bright Agrotech’s hardware in its farm, which consists of 20-foot high towers with vertical irrigation channels and facing LED lights. Leafy greens ready for picking end up looking similar to a solid wall of green.

Plenty claims to use 1 percent of the water and land of a conventional farm with no pesticides or synthetic fertilizers. Like other large soilless, hi-tech farms growing today, Plenty says it uses custom sensors feeding data-enabled systems resulting in finely-tuned environmental controls to produce greens with superior flavor.

Based on the West Coast, it plans to compete with the existing supply of greens from the salad bowl of California, by choosing premium seeds and catering growing conditions for optimal taste. Barnard says most greens growing in the field are bred to be hardy enough to last the 3,000 mile journey to the east coast and beyond.

He would not share specific growth goals for the near-term, but said that eventually they expect to be able to build two to six farms per month. The plan is to build these farms just outside major cities where retailers have distribution centers and real estate is more affordable. Barnard also said that an announcement about a major retail partnership is forthcoming.

Zack Bogue, an investor in Plenty through San Francisco venture capital fund Data Collective, agreed that the Bright Agrotech acquisition will help the startup scale. “By vertically integrating parts of their component supply chain, it will make the most efficient system out there more efficient,” he said.

Plenty claims to get 350 times the crop yield per year over an outdoor field farm. Or, as Barnard described, “It is the most efficient in terms of the amount of productive capacity per dollar spent, period.”

Plenty was the first indoor ag investment for big data-focused Data Collective, which participated in its $24.5m Series A in July 2016. “We’re pretty excited about that space because some of the hardest problems in agriculture are now lending themselves to an algorithmic or computational or applied machine-learning solution,” he said. But he added that the ability to scale was paramount, because scale is what allows data to be useful for machine-learning applications. “I came away feeling this was an endeavor that could truly achieve global scale pretty quickly,” he added.

Bogue said that though this match was a natural fit, he doesn’t expect more consolidation in the space.

Plenty has raised $26 million to date in a seed and Series A Round, both in 2016. The startup’s other investors are Innovation Endeavors , Bezos Expeditions , Finistere Ventures, Data Collective, Kirenaga Partners, DCM Ventures, and Western Technology Investment

Plenty Acquires Bright Agrotech to Globally Scale Impact of Local Farmers

Plenty Acquires Bright Agrotech to Globally Scale Impact of Local Farmers

Industry-leading technology will play crucial role in Plenty farms

June 13, 2017 - 09:00 AM - Eastern Daylight Time

SOUTH SAN FRANCISCO, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Plenty, the leading field-scale vertical farming company reshaping agriculture to bring fresh and locally grown produce to people everywhere, announced the acquisition of Bright Agrotech, the leader in vertical farming production system technology. Bright’s technology and industry leadership combined with Plenty’s own technology will help Plenty realize its plans to build field-scale indoor farms around the world, bringing the highest quality produce and healthy diets to everyone’s budget.

“Plenty grows food for people, not trucks. By making us all one team and formalizing our deep and close relationship, with a shared passion for bringing people healthy food through local farming, we’re positioned in a way no one else is today to meet the firehose of global demand for local, fresh, healthy food that fits in everyone’s budget,” said Matt Barnard, CEO and co-founder of Plenty. “Everyone wins — the small farmer, people everywhere and Plenty — as we all move forward delivering local food that’s better for people and better for the planet.”

Bright has partnered with small farmers for over seven years to start and grow indoor farms, providing high-tech growing systems and controls, workflow design, education and software. Bright will continue its work, expanding its base of hundreds of farmers around the world.

“We’re excited to join Plenty on their mission to bring the same exceptional quality local produce to families and communities around the world,” said Nate Storey, founder of Bright Agrotech. “The need for local produce and healthy food that fits in everyone’s budget is not one that small farmers alone can satisfy, and I’m glad that with Plenty, we can all work toward bringing people everywhere the freshest, pesticide-free food.”

About Plenty

Plenty is a new kind of farm for a new kind of world. We’re on a mission to bring local produce to people and communities everywhere by growing the freshest, best-tasting fruits and vegetables, while using 1% of the water, less than 1% of the land, and none of the pesticides, synthetic fertilizers, or GMOs of conventional agriculture. Our field-scale indoor vertical farms combine the best in American agriculture and crop science with machine learning, IoT, big data, sophisticated environmental controls and the exceptional flavor and nutritional profiles of heirloom seed stock, enabling us to grow the food nature intended — while minimizing our environmental footprint. Based in San Francisco, Plenty has received funding from leading investors including Eric Schmidt’s Innovation Endeavors, Bezos Expeditions, DCM, Data Collective, Finistere and WTI and is currently building out and scaling its operations to serve people around the world.

Contacts

Plenty

Christina Ra

christina.ra@plenty.ag

High-Tech Farms Give A New Meaning To ‘Locally Grown’

High-Tech Farms Give A New Meaning To ‘Locally Grown’

Published: June 8, 2017 4:58 a.m. ET

This is the new urban farm

Bloomberg

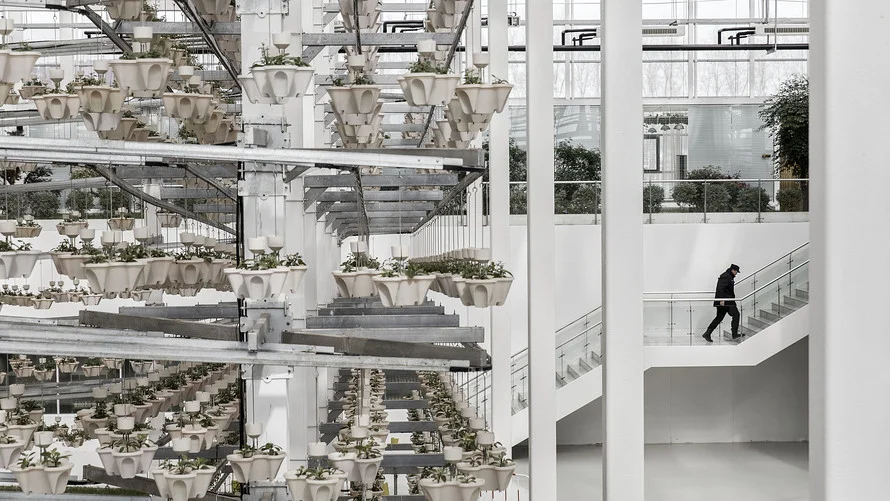

Plants growing in a rotary light-tracking system inside a greenhouse at a high-tech indoor farm on the outskirts of Beijing. China is turning to technology to make its land productive again.

By Betsy McKay

Billions of people around the world live far from where their food is grown.

It’s a big disconnect in modern life. And it may be about to change.

The world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, 33% more people than are on the planet today, according to projections from the United Nations. About two-thirds of them are expected to live in cities, continuing a migration that has been under way around the world for years.

That’s a lot of mouths to feed, particularly in urban areas. Getting food to people who live far from farms—sometimes hundreds or thousands of miles away—is costly and strains natural resources. And heavy rains, droughts and other extreme weather events can threaten supplies.

Now more startups and city authorities are finding ways to grow food closer to home. High-tech “vertical farms” are sprouting inside warehouses and shipping containers, where lettuce and other greens grow without soil, stacked in horizontal or vertical rows and fed by water and LED lights, which can be customized to control the size, texture or other characteristic of a plant.

Companies are also engineering new ways to grow vegetables in smaller spaces, such as walls, rooftops, balconies, abandoned lots — and kitchens. They’re out to take advantage of a city’s resources, composting food waste and capturing rainwater as it runs off buildings or parking lots.

“We’re currently seeing the biggest movement of humans in the history of the planet, with rural people moving into cities across the world,” says Brendan Condon, co-founder and director of Biofilta Ltd., an Australian environmental-engineering company marketing a “closed-loop” gardening system that aims to use compost and rainwater runoff. “We’ve got rooftops, car parks, walls, balconies. If we can turn these city spaces into farms, then we’re reducing food miles down to food meters.”

Moving beyond experiments

Urban farming isn’t easy. It can require significant investment, and there are bureaucratic hurdles to overcome. Many companies have yet to turn a profit, experts say. A few companies have already failed, and urban-farming experts say many more will be weeded out in the coming years.

Getty Images

In London, former air raid shelters are home to 'Growing Underground', the UK’s first underground farm, shown here in 2016. The farm grows pea shoots, rocket, wasabi mustard, red basil, red amaranth, pink stem radish, garlic chives, fennel and coriander, and supply to restaurants across London.

But commercial vertical farms are well beyond experimental. Companies such as AeroFarms, owned by Dream Holdings Inc., and Urban Produce LLC have designed and operate commercial vertical farms that aim to deliver supplies of greens on a mass scale more cheaply and reliably to cities, by growing food locally indoors year round.

At its headquarters in Irvine, Calif., Urban Produce grows baby kale, wheatgrass and other organic greens in neat rows on shelves stacked 25 high that rotate constantly, as if on a conveyor belt, around the floor of a windowless warehouse. Computer programs determine how much water and LED light the plants receive. Sixteen acres of food grow on a floor measuring an eighth of an acre.

Its “high-density vertical growing system,” which Urban Produce patented, can lower fuel and shipping costs for produce, uses 80% less fertilizer than conventional growing methods, and generates its own filtered water for its produce from humidity in the air, says Edwin Horton Jr., the company’s president and chief executive officer.

“Our ultimate goal is to be completely off the grid,” Horton says.

The company sells the greens to grocers, juice makers and food-service companies, and is in talks to license the growing system to groups in cities around the world, he says. “We want to build these in cities, and we want to employ local people,” he says.

AeroFarms has built a 70,000-square-foot vertical farm in a former steel plant in Newark, N.J., where it is growing leafy greens like arugula and kale aeroponically — a technique in which plant roots are suspended in the air and nourished by a nutrient mist and oxygen — in trays stacked 36 feet high.

The company, which supplies stores from Delaware to Connecticut, has more than $50 million in investment from Prudential, Goldman Sachs and other investors, and aims to install its systems in other cities globally, says David Rosenberg, its chief executive officer. “We envision a farm in cities all over the world,” he says.

AeroFarms says it is offering project management and other services to urban organizations as a partner in the 100 Resilient Cities network of cities that are working on preparing themselves better for 21st century challenges such as food and water shortages.

The bottom line

Still, these farms can’t supply a city’s entire food demand. So far, vertical farms grow mostly leafy greens, because the crops can be turned over quickly, generating cash flow easily in a business that requires extensive capital investment, says Henry Gordon-Smith, managing director of Blue Planet Consulting Services LLC, a Brooklyn, N.Y., company that specializes in the design, implementation and operation of urban agricultural projects globally.

The greens can also be marketed as locally grown to consumers who are seeking fresh produce.

Other types of vegetables require more space. Growing fruits like avocados under LED light might not make sense economically, says Gordon-Smith.

“Light costs money, so growing an avocado under LED lights to only get the fruit to sell is a challenge,” he says.

And the farms aren’t likely to grow wheat, rice or other commodities that provide much of a daily diet, because there is less of a need for them to be fresh, Gordon-Smith says. They can be stored and shipped efficiently, he says.

The farms are also costly to start and run. AeroFarms has yet to turn a profit, though Rosenberg says he expects the company to become profitable in a few months, as its new farm helps it reach a new scale of production. Urban Produce became profitable earlier this year partly by focusing on specialty crops such as microgreens—the first shoots of greens that come up from the seeds—that generally grow indoors in a very condensed space, says Horton, who started the company in 2014.

One of the first commercial vertical-farming companies in the U.S., FarmedHere LLC, closed a 90,000 square-foot farm in a Chicago suburb and merged with another company late last year. “We’ve learned a lot of lessons,” says co-founder Paul Hardej.

Among them: Operating in cities is expensive. The company should have built its first farm in a suburb rather than a Chicago neighborhood, Hardej says. Real estate would have been cheaper.

“We could have been 10 or 20 miles away and still be a local producer,” Hardej says.

The company also might have been able to work with a smaller local government to get permits and rework zoning and other regulations, because indoor farming was a new type of land use, Hardej says. While FarmedHere produced some crops profitably, it spent a lot on overhead for lawyers and accountants “to deal with the regulations,” he says.

Hardej is now co-founder and chief executive officer of Civic Farms LLC, a company that develops a “2.0” version of the vertical farm, he says—more efficient operations that take into account the lessons learned. Civic Farms is collaborating with the University of Arizona on a research and development center at Biosphere 2, the Earth science research facility in Oracle, Ariz., where it runs a vertical farm and develops new technologies.

Blossoming tech

New technology will improve the economic viability of vertical farms, says Gordon-Smith. New cameras, sensors and smartphone apps help monitor plant growth. One company is even developing augmented-reality glasses that can show workers which plants to pick, Gordon-Smith says.

“That is making the payback look a lot better,” he says. “The future is bright for vertical farming, but if you’re building a vertical farm today, be ready for a challenge.”

Some cities are trying to propagate more urban farms and ease the regulatory burden of setting them up. Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed created the post of urban agriculture director in December 2015, with a goal of putting local healthy food within a half-mile of 75% of the city’s residents by 2020. The job includes attracting urban-farming projects to Atlanta and helping projects obtain funding and permits, says Mario Cambardella, who holds the director title.

“I want to be ahead of the curve; I don’t want to be behind,” he says.

Many groups are taking more low-tech or smaller-scale approaches. A program called BetterLife Growers Inc. in Atlanta plans to break ground this fall on a series of greenhouses in an underserved area of the city, where it will grow lettuce and herbs in 2,900 “tower gardens,” thick trunks that stand in large tubs. The plants will be propagated in rock wool, a growing medium consisting of cotton-candy-like fibers made of a melted combination of rock and sand, and then placed into pods in the columns, where they will be regularly watered with a nutrient solution pumped through the tower, says Ellen Macht, president of BetterLife Growers.

The produce will be sold to local educational and medical institutions. “What we wanted to do was create jobs and come up with a product that institutions could use,” she says.

The $12.5 million project is funded in part by a loan from the city of Atlanta, with Cambardella helping by educating grant managers on the growing system and its importance.

Change at home

Another company aims to bring vertical farming to the kitchen. Agrilution GmbH, based in Munich, Germany, plans to start selling a “plantCube” later this year that looks like a mini-refrigerator and grows greens using LED lights and an automatic watering system that can be controlled from a smartphone. “The idea is to really make it a commodity kitchen device,” says Max Loessl, Agrilution’s co-founder and chief executive officer, of the appliance, which will cost 2,000 euros—about $2,200—initially.

The goal is to sell enough to bring the price down, so that in five years the appliance is affordable enough for most people in the developed world, Loessl says.

Biofilta, the company Condon co-founded, is marketing the Foodwall, a modular system of connected containers, an approach that he calls “deliberately low tech” because it doesn’t require electricity or computers to operate. The tubs are filled with a soil-based mix and a “wicking garden-bed technology” that stores and sucks water up from the bottom of the tub to nourish the plants without the need for pumps. The plants need to be watered just once a week in summer, or every three to four weeks in the winter, says Chief Executive Marc Noyce. The tubs can be connected vertically or horizontally on rooftops, balconies or backyards. “We’ve made this gardening for dummies,” Noyce says.

Biofilta

Biofilta's Foodwall

The Foodwall can use composted food waste and harvested rainwater, helping to turn cities into “closed-loop food-production powerhouses,” Condon says.

He and Noyce were motivated to design the Foodwall by a projection from local experts that only 18% of the food consumed in their home city of Melbourne, Australia, will be grown locally by 2050, compared with 41% today, Noyce says.

“We were shocked,” says Noyce. “We’re going to be beholden to other states and other countries dictating our pricing for our own food.”

“Then we started to look at this trend around the world and found it was exactly the same,” he says.

Traditional, rural farming is far from being replaced by all of these new technologies, experts say. The need for food is simply too great. But urban projects can provide a steady supply of fresh produce, helping to improve diets and make a city’s food supply more secure, they say.

“While rural farmers will remain essential to feeding cities, cleverly designed urban farming can produce most of the vegetable requirements of a city,” Condon says.

Betsy McKay is a senior writer in The Wall Street Journal’s Atlanta bureau. She can be reached at betsy.mckay@wsj.com.

The article “A Farm Grows in the City” first appeared in The Wall Street Journal.

Food Revolution

Food Revolution

Applying innovation to agriculture, a student startup plans to use hydroponics to grow fruits and vegetables four times faster using 90 percent less water.

May 04, 2017 | Abigail Lague, avl8bj@virginia.edu

Those walking into the University of Virginia’s Clark Hall find themselves face-to-face with a state-of-the-art hydroponics system. A table full of growing plants and violet light is hard to miss.

As part of an undergraduate sustainability initiative, these systems have been installed in various locations on UVA’s Grounds, including Newcomb Hall and Observatory Hill Dining Hall.

An undergraduate-led company, Babylon Micro-Farms, is bringing these small hydroponic farm prototypes to Grounds as part of an effort to make fresh fruit and vegetables easily accessible for more people.

Hydroponic farming is the growing of plants in nutrient-rich solutions without the use of soil. Usually, hydroponic systems are large, costly and used in mass production – not readily available to the average consumer. However, the system created by Babylon Micro-Farms are less bulky and available for personal use in the home. Each structure is only 6 feet wide by 3 feet deep and about 6 feet tall. Above the plants are LED grow lights that emit light at the right wavelength for photosynthesis.

Plants grown in hydroponics systems, such as those used by Babylon Micro-Farms, are free of GMOs and pesticides. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

This high-tech farming method uses 90 percent less water and grows food up to four times more quickly. Additionally, hydroponics systems do not use genetically modified organisms, pesticides or inorganic fertilizers and help reduce “food miles,” the distance between where a food item is grown and where it is sold.

The Babylon team began testing prototypes around Grounds after building an early model through the student entrepreneurial clubhouse, HackCville, and winning $6,500 from Green Initiatives Funding Tomorrow. Student Council’s sustainability committee, with assistance from the Office of the Dean of Students, funds the annual GIFT grant.

“It’s been a massive hit,” company founder and fourth-year student Alexander Olesen said of the hydroponic systems’ reception in dining halls. “At first, they weren’t too sure about it, and then after a month when the plants grew, they said we could go ahead and pitch them a more finalized version.”

From left, Stefano Rumi, who handles the business expansion of Babylon Micro-Farms; founder Alexander Olesen; electrical engineer Patrick Mahan; and head engineer Graham Smith. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

The hydroponic systems in the dining halls have been growing a mixture of lettuces, arugula, kale and spinach. The yield from one table alone has been enough to feed the entire Babylon Micro-Farms team for about a week. Olesen, a foreign affairs major, and his business partner, third-year student Stefano Rumi, a sociology and social entrepreneurship double-major, hope to add their produce to the UVA Dining menu so that other students may enjoy the vegetables produced by their hydroponics systems.

To make the produce affordable, Babylon Micro-Farms plans to offer a comprehensive hydroponics system for less than $1,000 – something that cannot be found on the market today. Their system will be much smaller than other hydroponic structures and easier to have in the home.

“The existing systems you get are made out of the same materials as trash cans, and they’re still more expensive, which is crazy,” Olesen said. “It’s just a table, and it blends in. You can fit in around 100 plants. Unlike other systems, you have versatility.”

These LED grow lights emit light at a wavelength that facilitates photosynthesis so that the plants will grow faster. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

The system can be easily installed in the home and doesn’t require any special skills to set up, he said.

While the benefits of hydroponics are appealing to many, Olesen is aware that not everyone wants to have to do a “science experiment” at the end of a long day to grow lettuce. With this in mind, Babylon Micro-Farms plans to provide premeasured seeds, nutrients and an automated system to optimize the pH of the hydroponic system, making the process of growing one’s own food as easy as possible. All users have to do is pour in the mixture.

“Food is such a fundamental part of our lives,” Rumi said. “In a world where we’re innovating everything, the last thing we’ve innovated is how we grow our food. We essentially do it the same way we’ve been doing it for 10,000 years, except for pumping unhealthy pesticides that have these terrible environmental effects.”