Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

What Climate Change Has To Do With The Price of

What Climate Change Has To Do With The Price of Your Lettuce

By Caitlin Dewey March 3, 2017

A worker labors at a romaine lettuce farm in Yuma County, Ariz. (Eric Thayer/Reuters)

Unusual weather in the Southwest could cause a nationwide salad shortage later this month. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg (lettuce): Scientists say the weird weather is probably caused by climate change — which means these sorts of problems are likely to happen again.

The shortage, first reported by NPR, is the result of two separate phenomena in Arizona’s Yuma County and California’s Salinas Valley, the two places where the United States grows most of its leafy greens. In Yuma, the lettuce harvest, which usually runs from November to April, wound up early because of unusually warm weather. And in central California, which typically picks up the harvest once Yuma is done, heavy precipitation delayed some plantings.

[Across the U.S., February 2017 was the near-warmest in three decades]

That could potentially cause a gap at some point between lettuce supplies, said George Frisvold, an agricultural economist at the University of Arizona. Frisvold’s colleague, Jonathan Overpeck, the director of the university’s Institute of the Environment, says we can blame ourselves, in part, for the great salad shortage.

“There’s this old adage in climate science that you can’t attribute any one event to human causes,” Overpeck said. “That’s not really true anymore, because now it’s really been established that humans alter the whole global climate system. Anything related to increased warmth in the atmosphere likely has some element of human causation.”

Both the temperature in Yuma and the rain in Salinas have a link to atmospheric warmth. The case of Yuma is pretty obvious: Temperatures in the Southwest have been increasing for 100 years, and this winter was no different. According to the National Weather Service, February’s average temperature was two degrees warmer than the recorded average in recent decades.

In Salinas, the situation is a bit more complex, Overpeck said. The region has seen an unusual number of storms called “atmospheric rivers” -- you might know them by the name Pineapple Express — which push heavy precipitation to the Pacific coast from around the Hawaiian islands. It’s unclear whether climate change has a role in the increased incidence of atmospheric rivers, Overpeck said. While some early research suggests that is the case, more data is needed to confirm it.

That said, it’s “a basic concept of physics” that when the atmosphere is warmer, it holds more moisture, Overpeck explained. That means that, when storm clouds form, you tend to see more snow and rain.

According to the 2012 Census of Agriculture, Yuma County boasts nearly 70,000 acres of planted lettuce, while Monterey County, the home of the Salinas Valley, has 134,000. The 2015 Salinas harvest was valued at more than $1.65 billion.

Both regions primarily grow iceberg and leaf lettuce, followed by spinach and baby greens.

Incidentally, these sorts of cascading disruptions aren’t just limited to lettuce — or even to the United States. Britain recently suffered a widely publicized shortage of iceberg lettuce, zucchini, broccoli and cabbage, brought on by extreme weather in Europe’s “salad bowl,” Spain.

Bad weather in Spain causes European lettuce shortage

Spanish farmers say the shortage of lettuce in European retailers will continue into March as a result of bad winter weather conditions. But they say the recent rationing by supermarkets in the UK was not their fault. (Reuters)

Closer to home, fruit growers across the Northeast and Midwest have expressed concern that unusually high and fluctuating temperatures could cause crops like apples, cherries, plums and grapes to develop too early and expose them to spring freezes. The Progressive Farmer recently warned that “almost off the charts” temperatures in Kansas and Oklahoma could put early-growing winter wheat at similar risk, plus expose it to warm-weather pests and diseases.

[Cherry blossom forecast: Peak bloom will be close to record-early this year]

In 2012, high winter temperatures cost Michigan $220 million in cherry harvests. That same year, unusually hot nighttime temperatures also cut into Corn Belt yields.

The National Climate Assessment estimated that California and Arizona will have gained 70 extra hot nights per year and 12 to 15 additional consecutive days without rain by the end of the century, because of warming.

“Climate change impacts on agriculture,” the report concludes, “will have consequences for food security both in the U.S. and globally.”

Compared with that dire prediction, of course, a few weeks without lettuce probably doesn’t sound so bad. Frisvold cautions that any price spikes resulting from a shortage would probably be short term and that none have materialized just yet.

But in the sense that the looming salad scenario signals things to come, it's worth paying attention.

“Every grower is noting warming,” Overpeck said. “And while we can’t say what percentage is due to humans, we can say humans are putting their foot on the accelerator.”

Why The local Food Trend Will Not Cut It In A Climate Change Future

Why The local Food Trend Will Not Cut It In A Climate Change Future

by Pay Drechsel | CGIAR

Thursday, 2 March 2017 14:23 GMT

ABOUT OUR CLIMATE COVERAGE

We focus on the human and development impacts of climate change

Urban agriculture already plays an important role in global food production, but can it keep cities fed?

Securing sufficient food and nutrition for growing cities is considered one of today’s greatest development challenges.

Getting food from farms to urban centres raises a number of well-known issues: transporting fresh food can be costly and complicated, leading to concerns about affordability, nutritional quality and environmental impact.

But with the advance of climate change, yet another question is quickly rising to the top of the list: how can cities secure a reliable supply of food when droughts, floods and other extreme weather events are frequently interrupting supply chains?

This question is likely to be among those discussed at The Economist’s upcoming Sustainability Summit, and so ahead of the session on “Cities of the Future”, we look at what we actually know about urban food systems and their potential resilience.

GO LOCAL - OR GO GLOBAL?

The local food movement has increasingly been touted as a solution for a reliable, affordable supply of food to cities, especially in the developed world.

Concepts such as “vertical farming” – growing food in skyscrapers using hydroponics to bypass the need for soil or sunlight – has generated a great deal of interest, and it will likely be one of a diverse set of urban agriculture types we will see more of in the future.

Urban agriculture already plays a greater role in global food production than what we might think, with 456 million hectares - an area nearly half the size of the USA - under cultivation within 20km of the world’s cities, and 67 million hectares being farmed in open spaces in the urban core.

Yet, the findings of a recent study imply relying on urban farming is not enough.

In fact, we have found there is little evidence that local food systems are inherently better than national or global ones when it comes to securing supplies. Rather, a diversified urban food supply system, with food originating from a range of sources, might instead bolster a city’s resilience because it would be less sensitive to the impacts of climate change. In this scenario, even if farms near a city are flooded and the harvest lost, food from other sources might still be available.

For example, vegetable supplies in Spain were recently affected by extreme weather after lots of rain and then lots of snow in the Mediterranean. Subsequent shortages of aubergine, courgette and lettuces forced prices up, affecting the domestic market as well as the international market.

Considering the risks of such a dependence on a singular food source, what can we say about the resilience of some of world’s fastest growing cities?

TALE OF TWO WEST AFRICAN CITIES

Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso, experienced a 400 percent population increase between 1985 and 2012, swelling to almost 2 million people today. In Tamale, in neighbouring Ghana, the urban population has doubled every decade since 1970, today reaching about 400,000.

Our team recently spent two years tracking more than 40,000 records of food flowing in and out of these two cities. For each entry, we catalogued the place of origin, type of food and destination.

The results showed that both cities relied heavily on agricultural production in nearby areas to meet urban food demand. About a third of the food supplying Tamale originated from within 30km and half from within 100km. Some foods came almost solely from within the city itself; 90 per cent of leafy vegetables, which are an important part of traditional diets and rich in nutrients, were supplied by urban farming.

But both cities also depended on supplies of some food from further afield. For example, Ouagadougou is heavily reliant on imported rice, an important staple food that cannot easily be substituted by other crops. While it is grown in the region, domestic production cannot meet the demand.

At the same time, we also saw that climate change-induced weather events can have grave consequences for urban food supply: in 2007, droughts and subsequent floods in northern Ghana destroyed half of all staple crops. The results were, again, food shortages and rising prices.

INVESTING IN DIVERSE SUPPLY CHAINS

The findings of the Ouagadougou-Tamale study imply that achieving a sustainable, resilient urban food system is not a simple question of either local or global food supply chains; both are necessary. The more diverse urban food supply systems, the more resilient.

Local agricultural production needs to be considered in urban planning because most cities already are dependent on locally produced food. Overall, the extent of urban agriculture on a global scale warrants a reorientation of agricultural policies and development work, which are mostly focused on rural contexts.

Further, locally produced food comes with a set of significant advantages: the carbon footprint is lower, and food reaches consumers when it is fresh. Not least, local production safeguards the livelihoods and incomes of smallholders.

Yet it cannot stand alone; relying on a single cluster of high-rise buildings or peri-urban farms to provide a megacity with all the food it needs is just too risky.

Instead, planning for resilient food systems in cities of the future will require a holistic perspective. Focusing on diversity – including diverse sources, actors, means of transportation and more – may be the first step toward reliably securing food for growing urban populations in the face of climate change.

As we head for a world with many more mouths to feed, variety may be more than just the spice of life – it may be its bread and butter too.

A city farm in East Perth, Western Australia. The UN is urging cities to include food production in its urban planning. Image:

Inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit to Focus on Investing in Discovery

On April 1, 2017, Food Tank presents its first Boston Summit, “Investing in Discovery,” in collaboration with Tufts University and Oxfam America. The event will gather dozens of expert speakers and panelists who represent farmers, policymakers, businesses, chefs, nonprofit groups, elected officials, and more at the Tufts University Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy

Inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit to Focus on Investing in Discovery

On April 1, 2017, Food Tank presents its first Boston Summit, “Investing in Discovery,” in collaboration with Tufts University and Oxfam America. The event will gather dozens of expert speakers and panelists who represent farmers, policymakers, businesses, chefs, nonprofit groups, elected officials, and more at the Tufts University Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy. See the speaker lineup HERE, and please share this article with people who might be interested in attending the Summit.

Panel topics include Long-Term Solutions for a Healthy Planet, The True Value of Food, Creating Better Food Access, and Farm and Food Innovations. Moderators for these panels include agricultural professionals and journalists from The Washington Post, National Public Radio, and more. The Summit can be viewed remotely via a free Livestream at foodtank.com and on Facebook Live.

Confirmed speakers include (in alphabetical order—more to be announced soon):

Lauren Abda, Branchfood; Jody Adams, Trade Restaurant; Julian Agyeman, Tufts University; Patricia Baker, Massachusetts Law Reform Institute; Ian Brady, AVA; Sara Burnett, Panera Bread; Kiera Butler, Mother Jones Magazine; Matthew Dillon, Clif Bar; Jess Fanzo, Johns Hopkins University; Keri Glassman (MS, RD, CDN), Nutritious Life; Oliver Gottfried, Oxfam America; Timothy Griffin, Tufts University; Tamar Haspel, The Washington Post; Lindsay Kalter, Boston Herald; Alex Kingsbury, The Boston Globe; Wendy Kubota, Nature’s Path Foods; Corby Kummer, The Atlantic; William Masters, Tufts University; Congressman Jim McGovern, U.S. Congress (D-MA); Brad McNamara, Freight Farms; Monique Mikhail, Greenpeace; Dariush Mozaffarian, Tufts University; Danielle Nierenberg, Food Tank; Michel Nischan, Wholesome Wave; Councilor Ayanna Pressley, Boston City Council; Doug Rauch, Daily Table; Ruth Richardson, Global Alliance for the Future of Food; Lindsey Shute, National Young Farmers Coalition; Matt Tortora, Crave Food Services, Inc; Paul Willis, Niman Ranch Pork Company; Norbert Wilson, Tufts University; Tim Wise, Small Planet Institute and Tufts University.

More than 60,000 people from around the world streamed the last Food Tank Summit in Washington, D.C., at The George Washington University. During the February 2017 event, there were also one million organic views on Facebook Live. One of Food Tank’s goals is to create networks of people, organizations, and content that push for food system change, achieved in part through the conversation and connections cultivated at these Summits. Future 2017 Summits will take place in new locations for the first time: New York, Los Angeles, and Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Buy tickets for the Boston Summit on April 1, 2017, and become a Food Tank member. If you or your organization is interested in sponsoring an upcoming Food Tank Summit, please email Bernard Pollack at bernard@foodtank.com for more details.

D.C.’s Urban Farms Wrestle With Gentrification and Displacement

D.C.’s Urban Farms Wrestle With Gentrification and Displacement

Urban farmers often hold high-minded ideals about food justice and access; they’re also often unwitting vehicles for driving out communities of color.

BY BRIAN MASSEY | Commentary, Food Justice, Urban Agriculture

02.27.17

If you’ve lived or worked in Washington D.C. over the last decade, the scale and pace of gentrification there has been impossible to miss. Over the last decade, the city has experienced a rapidly increasing demand for, and cost of, housing, similar to that in other knowledge hubs and “superstar cities” like New York, San Francisco, Seattle, and Boston.

In addition to all the good things that come with increased interest in density and urban living, those cities have been the hardest hit by displacement, a process that disproportionately affects poor folks of color. Everyone who lives or works in D.C. can palpably feel this slow-motion injustice, and we are all forced to grapple with it, whether we want to or not.

“Everybody—wherever you go, no matter the educational background—sees what’s going on,” Xavier Brown told me. Brown is the founder of Soilful City, an urban agriculture organization in D.C. with the justice-centered mission of healing “the sacred relationship between communities of African descent and Mother Earth.”

Last year, I managed an eight-year-old urban farm in the neighborhood of LeDroit Park. LeDroit is just down the hill from Howard University and next to the super-hip neighborhoods of Shaw and Bloomingdale. The farm itself is surrounded by public housing, Howard dorms, and renovated row houses selling for over $800,000.

Farming in the middle of all that created a sort of socio-economic whiplash. On good days, it felt like the best that a city can be, a glorious melting pot, with the farm as a gathering place for folks to celebrate commonality. But on bad days, when I had to clean up vandalism, or when I couldn’t for the life of me get my neighbors of color to visit the farm, it felt like an exclusive resource designed to make newcomers feel comfortable and long-term residents feel alienated. It felt like I, a bearded white dude, was actively contributing to an injustice. Or, just as bad, like I was pretending to be neutral, while standing by and watching it happen.

In my experience, most urban farmers are justice-minded folks who enter this profession with high-minded ideals. But in D.C. we are increasingly finding that our work is being associated with, and even coopted by, the forces that are driving extreme gentrification and displacement, forces viewed negatively by many working class communities of color.

As I slogged through the harvest season, I realized that I couldn’t be the only farmer wrestling with this conundrum. So I set out this winter to have some frank conversations with others in my community about how to address displacement, and how to position our industry in relation to the larger forces at work.

Urban Agriculture’s Role in a Gentrifying City

During the first decade of the 21st Century, D.C. became much more young, single, and white. The city’s white population jumped by 31 percent, while its Black population declined by 11 percent. A city that peaked at 71 percent Black in 1970 lost its Black-majority status in 2011.

All of this makes Brown think about displacement every day. “A lot of urban ag is based on working in stressed and distressed communities. These communities are getting pushed out, and once [they’re] pushed out, they’re gone, and it turns into something else,” he said. “Then your mission is gone.”

Dominic Pascal is the production manager at THEARC Farm, an urban farm in the city’s Ward 8 that provides food access and education for the low-income and working-class families that live nearby. He was initially inspired by the community-based feel of the urban agriculture scene in D.C., but he worries that quality could get lost as the city changes.

“Hopefully it never becomes something where kids look at a farm in a community where their parents and grandparents grew up and feel like it’s not for them,” he said. As a Black farmer, he understands that his presence and that of others like him “is an important symbol for the community to see.” He hopes to be able to say, “I look like you, I’m related to you, and this space is for you.”

“I’ve seen a lot of maps where it looks like we’re increasing food access [in D.C.], when we’re actually just pushing poor people out,” Josh Singer, executive director and founder of Wangari Gardens, told me. Wangari is an innovative community garden near several rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods, and was designed explicitly to promote responsible community development in the face of this displacement.

“Say you have a neighborhood that is a food desert,” Singer, who is white, said, starting a story about a hypothetical project in which someone crafts a narrative, gets a big grant, builds a big garden, and does most outreach and organizing through social media. “All of a sudden that garden is just full of people who recently moved to the neighborhood, who are all good people, but who aren’t really food insecure.”

Singer and I both know many projects like this in D.C., projects that raise a good deal of money and garner glowing profiles from the press at their launch, but don’t work with the community in the planning stages, and don’t end up serving the people they say they’re going to serve.

Lauren Shweder Biel, executive director of DC Greens, a food justice organization focused on food education, access, and policy, argued that urban agriculturalists need to address these “intersectional pressures on the communities that [they] serve.”

“We know that urban ag is a tool for neighborhood revitalization and beautification, and we know that those are catchwords for gentrification,” Schweder Biel, who is white, said. That’s why she believes urban ag groups should also work to “guarantee affordable housing in areas where we’re putting in urban farms, recognizing that these urban farms will be tools of displacement.”

According to many urban farmers, projects like this end up backfiring not only because they replicate the oppressive patterns of most urban development, but also because they cement the belief in the minds of many long-term residents of color that urban agriculture is not for them. When that happens, those projects are seen as part of the problem.

Creating Community Ownership

“The legwork is the work. The work isn’t growing food,” Chris Bradshaw said bluntly.

Bradshaw is the founder and executive director of Dreaming Out Loud, an organization that is preparing to open one of the most ambitious urban farms in the city, the Kelly Miller Farm. It’s ambitious not just because of its size—two acres of flat land behind a DCPS middle school—or its location—Lincoln Heights, a neighborhood untouched by the city’s farm-to-table restaurant and organic grocery store boom.

Rather, its most lofty ambitions lie in the process that has preceded it, how it is attempting to be deeply collaborative and interwoven with the community that surrounds it from day one.

“Our work has been about relationship building over the course of a year with folks that are from the neighborhood, in the community, [folks] that we’d previously known and went deeper with, and some that we discovered along the way,” Bradshaw, who is Black, told me. He recalls sitting outside the farm listening to one older resident for two hours, getting bitten by mosquitos while she told him every single thing that had gone wrong [with previous development projects].

“The projects that are helping … are the ones that don’t just assume that they know what’s best for the community and force it on them,” Josh Singer said. “They listen to these communities, they build relationships, and they allow these communities into every aspect of decision-making.”

Shweder Biel said that if you accept that urban agriculture should be community-centric and if you follow that concept to its logical conclusions, then there are implications for how projects and organization should ultimately be structured.

“If what [urban agriculture] does is create a richer sense of community,” she told me, “it requires that there be investment by the communities that are surrounding the farm… there need to be the indicators that this is for me, for us, for the community members.”

This alternative vision of urban agriculture—one that is more intentional about how it interacts with the race and class dynamics of the city in which it operates—has had a very tangible impact on how DC Greens handles its business.

“We’ve been doing a series of anti-racism trainings internally, just to make sure that the real point of the work is very front and center for all of us,” Shweder Biel told me. As a result, the farm has hired more people of color and D.C. natives as core staff members and worked with them to design programming and outreach. They’ve also hired more people from the neighborhood to run their farmers’ markets, and they regularly invite neighborhood representatives to join them when meeting with power brokers around D.C.

Christian Melendez pointed out that “urban ag, with its ear to the ground, could be a form of preserving and building community.” Melendez, who is Latino, was the lead farmer for many years at ECO City Farms in Edmonston, MD, and recently left to start his own bicycle composting business. “You can automate greenhouses, which has some value, but what kind of culture do we want to build?”

“I’ve met so many people in the shadows of D.C. who were farmers back home in their country,” he told me. “What are the stories and the foods that we’re losing because people are being displaced? That [displacement] can be from Mexico to D.C., or it can be from D.C. pushed out to Prince George’s County.”

Soilful City’s Brown looks at urban agriculture in under-resourced urban environments as an organizing tool. “A lot of communities that I work in are powerful, but people feel like they’re fighting against a giant,” he explained. His goal is “to help people find power within themselves,” turning the energy required to organize around something tangible like a garden into energy for organizing around whatever other issues are affecting their lives. “It’s about food,” he says, “but we gotta be a little bit bigger than food.”

Joining the Larger Movement for Social Justice

In the wake of the recent election, progressive groups all over the country have been reflecting and rebuilding, redesigning strategies to reflect our new political reality, and the Food Movement’s been no exception.

In D.C., this political and media capital of the world, some in the urban agriculture community are seeking to weave their work into the larger struggle for justice.

“[We’re] making those broad based alliances where we’re connecting food to land to housing to everything else,” Brown told me.

“Coalitions are necessary, because then it’s not just one voice, it’s multiple voices,” Chris Bradshaw added. “And it’s not these disjointed calls in the wild. It’s a coordinated and multiplied voice around justice as a platform.”

Dreaming Out Loud explicitly aims “to have the broader conversations about housing, poverty, healthcare, justice, race, gender, class, all those things, through this vehicle” of urban agriculture,” Bradshaw told me. But, in the meantime, he thinks that we can do “some pretty cool things that do help the physical circumstances of food access, job creation, community wealth building.”

At the end of this process, after the last of these many profound conversations, I found myself returning to something I discovered at the beginning, the last line from the San Francisco Urban Agriculture Alliance’s position statement on gentrification:

“…While we’ve got our heads down, hands in the dirt, cultivating a new world into existence, we must think of everyone who we want to be in that new world, and what we can do to get there with them—lest we look up to find that those potential allies have long since disappeared.”

Urban farmers in D.C. are increasingly looking up. I know I am.

On the Heels of EcoFarm, Farm Lot 59 Issues Call to Action for Urban Agriculture

On the Heels of EcoFarm, Farm Lot 59 Issues Call to Action for Urban Agriculture

by SASHA KANNO

FEBRUARY 27 2017 14:42

Farm Lot 59 is the definition of a community farm. As a food hub that serves the greater Long Beach area and beyond, we create an outdoor community space where skills grow, healthy ideas take root and people become inspired.

I’ve met and worked with thousands of people in the eight years I have been in local agriculture. Our visitors often don't know the basics, so I teach the basics, like how to use a shovel or push a wheelbarrow. I often teach what real food looks like as well, with lessons like how to find a tomato amidst its green leaves.

We work hard, and the soil shows it. We just so happen to get amazing produce out of that soil, which then creates jobs and many other opportunities for our visitors and the farm.

I just returned home from the 37th annual EcoFarm Conference in Monterey County and am deeply inspired by the great work being done. Santa Cruz-based "Food What?!" is a program that empowers youth to be proud of themselves, embrace their voice and understand their food rights. Edible Schoolyard in Berkeley is phenomenal. They joined forces with a local high school and other community partners for training programs and to provide a safe place for people to be and learn.

San Francisco's Bi-Rite market is a farm, creamery, and retail store. They offer training programs to the community and welcome back everyone who has gone through their programs. San Francisco Unified School District is totally on board, and supports real world garden classrooms, cooking schools and farming academies, and is dedicated to forming programs that directly benefit the youth.

When I come across programs like these, I see people who choose work that provides love and dignity in a field of crucial relevance to community health and I appreciate the transformative mutual power of vital partnerships. When we train others, we are no longer reaching the few around us; we are empowering those around us to pass along a critical life skill—a knowledge of food—to thousands more people who we may never know.

Farm Lot 59 is our amazing place to come to. It's a peaceful oasis surrounded by nature and varieties of plants from around the globe. It’s a safe place where people of any race and gender can share and receive full respect. It's not about farming—well, it is—but it's more. It's about food policy, transparency, the restaurant industry, retail, chemistry, soil science, education, food culture... it's endless. Your local farm is a hub for all kinds of good things.

Community farms like Farm Lot 59 are not meant to grow massive food crops. Instead, we teach people where food comes from, how to grow it, how to cook it and how make a living doing so. Humans have been cultivating crops for about 12,000 years, but many people today have forgotten their connection to food. Local farms are keeping this knowledge alive, and bringing people together through good hard work.

We need to come together as a city and put an end to food insecurity and food ignorance, and Farm Lot 59 is here to help. Dial in and stay informed, participate and give back. Learn about building a cooperative market, supporting our local economy and eating at locally owned restaurants that support their local farm. Reach out to Farm Lot 59 to explore a new partnership. You live here, work here and raise your family here. Let's work together to be the change that Long Beach needs.

Sasha Kanno is the founder of Long Beach Local, an agriculture-based nonprofit. She is the farmer and vision behind Farm Lot 59. She teaches at Farm Lot 59 and Maple Village Waldorf School. She has been awarded numerous grants and awards for her work in the community as a leader, innovator and driving force in the local food movement. She lives in Wrigley with Nelson, Nalu, some fish and a few chickens.

For more information about Farm Lot 59, visit the Facebook page here.

Farm Lot 59 is located at 2714 California Avenue

Farming Meets High Tech When Natural History Museum Kicks Off Food Lecture Series

FEB 19, 2017

Become a Member | Ad-Free Login

Farming Meets High Tech When Natural History Museum Kicks Off Food Lecture Series

By KATHY STEPHENSON | The Salt Lake Tribune

First Published Feb 18 2017 12:24PM • Last Updated Feb 18 2017 10:19 pm

They say you can't fool nature, but hundreds of "nerd farmers" around the globe are tapping technology to control climate and create the perfect conditions for growing food.

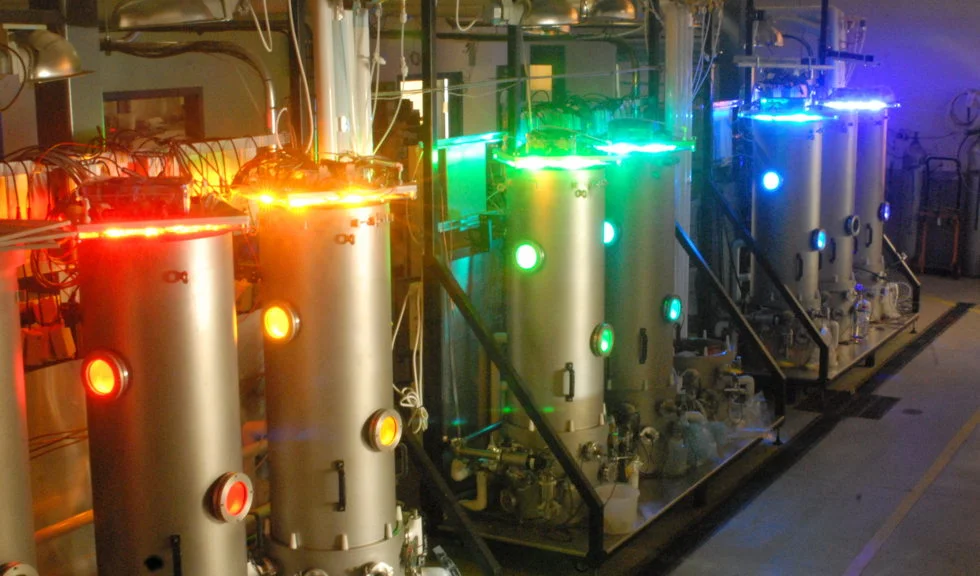

They are doing it with a personal food computer created by Caleb Harper and his team in the Open Agriculture Initiative at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Harper, the principal investigator and director of the lab, leads a diverse group of engineers, architects and scientists in the development of future food systems.

Their climate-controlled box, which can sit on a tabletop, has a computer brain and sensors that allow users to manipulate temperature, carbon-dioxide levels, humidity, light and pH. The plants are grown in minimal amount of water — no soil — using hydroponics.

Anyone, in any part of the world, can grow food, no matter the season, said Harper. Imagine growing water-loving tropical fruits in the middle of the Utah desert or sun-loving summer berries in the midst of a harsh winter.

Harper will talk about this blending of agriculture and technology Tuesday, when he kicks off the Natural History Museum of Utah's annual lecture series. Food is the theme of the five presentations, which include a keynote address by TV personality, chef and author Andrew Zimmern. Tickets for his talk go on sale Wednesday. (See box for details.)

Harper's lecture is free but requires a reservation.

There are nearly 400 "nerd farmers" around the globe who have built personal food computers — using Open Ag's open-source technology — collecting and sharing data with other users, Harper said.

"Every food computer that comes online, whatever they grow is recorded and in the future can be replayed as many times as we want," he said.

Farmers create their own growing "recipe" such as programming in more light or less humidity to see what happens. "As people explore, we are decoding that plant and getting a clearer map of a plant's ability to express itself," he said. "It's pretty phenomenal."

Eventually, Harper hopes the data can be used to create economically viable farms — possibly in shipping containers — that can be placed anywhere to create "hyperlocal food production."

"We need better food-supply chains, which are notoriously complex," he said. "This technology could be a new tool in the chain."

Interest in the personal food computers has grown beyond just the research stage, so Harper recently formed the nonprofit Open Agriculture Foundation, which will protect the open-source data and intellectual property and foster the growing community of farmers.

Harper and Utah entrepreneur Daniel Blake also have started Fenome, a small business that has begun assembling kits the community can buy that have everything needed to build a personal food computer.

The Fenome lab in West Valley City also houses large indoor growing tents, where Blake and the staff experiment with varieties of plants, learning which ones grow best in the personal food computer environments.

The personal food computers have other applications, as well. Many schools are using them to teach about biology, botany and climate change as well as coding, computer programming and engineering.

And Blake recently returned from Jordan, where he visited Azraq, a camp for refugees of the Syrian civil war. He said the United Nations World Food Organization is interested in food computer systems that could help supply at least a portion of the food to those living in the camps. Currently, all food and water are shipped.

"We are in the beginning stages of the process," Blake said, "but food computers could be deployed anywhere, especially harsh environments where food security is a problem."

Why We Need Technology As The Key Ingredient In Our Food

When asked how food security and production can be improved in Africa, former Rwandan minister and current president of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) Agnes Kaliba, had one simple answer: “Access to technologies.”

Peter Diamandis, ContributorChairman XPRIZE

Why We Need Technology As The Key Ingredient In Our Food

02/17/2017 01:54 pm ET | Updated 15 hours ago

hen asked how food security and production can be improved in Africa, former Rwandan minister and current president of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) Agnes Kaliba, had one simple answer: “Access to technologies.”

Ms. Kaliba is exactly right. We are sitting at the cusp of an explosion in exponential technologies, which can be the most critically important ingredients to improve the health and quality of life for all humanity.

The World Food Programme (WFP), the largest humanitarian organization in the world, estimates that some 795 million people do not have enough to eat to maintain their health. Additionally, we have faced an unprecedented number of large-scale emergencies — Syria, Iraq and the El Niño weather phenomenon in Southern Africa. Just last month, WFP stepped up support for tens of thousands of displaced Syrians returning home to the ruins of eastern Aleppo City, providing hot meals, ready-to-eat canned food and staple food items such as rice, beans, vegetable oil and lentils. Like Agnes Kaliba in Nairobi, WFP has resolved that technology will help most rapidly in providing better assistance in emergencies and achieve a world without hunger.

Singularity University (SU), which I co-founded with Ray Kurzweil in 2008, is a benefit organization focused on using exponential technologies to solve our Global Grand Challenges. At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Ertharin Cousin, the Executive Director of WFP, announced a new partnership with SU for a Global Impact Challenge for food.

Our Challenge is soliciting bold ideas from innovators around the world on how to create a sustainable supply of food after the onset of a crisis. In this way, we can help vulnerable families support their own households and reduce their dependence on external assistance. Entries can range from concepts to implemented innovations. Shortlisted winners will be invited to a bootcamp at the WFP Innovation Accelerator in Munich to flesh out their ideas with WFP innovators. One team will be selected to attend an all-expenses-paid, nine-week Global Solutions Program at Singularity University at NASA Research Park in Silicon Valley.

Here are some examples of moonshot thinking – and how converging exponential technologies are already reinventing food:

- Vertical Farming: If 80% of our planet’s arable land is already in use, then let’s look up. The impact of technology in vertical farming is powerful. In addition to maximizing the use of land, we can use AI to control the exact frequency and duration of light and pH and nutrient levels of the water supply. Vertical farms using clean-room technologies avoid pesticides and herbicides, and the fossil fuels used for plowing, fertilizing, harvesting and food delivery. Vertical farms are immune to weather, with crops grown year-round. One acre of a vertical farm can produce 10x to 20x that of a traditional farm. And if roughly one-quarter of world’s food calories are lost or wasted in transportation, then let’s think local. The average American meal travels 1,500 miles before being consumed. Moreover, 70 percent of a food’s final retail price is the cost of transportation, storage and handling. These miles add up quickly. The vertical farming market was $1.1 billion in 2015, and projected to exceed $6 billion by 2022.

- Hydroponics and Aeroponics: Traditional agriculture uses 70 percent of the water on this planet. Hydroponics is 70 percent more efficient than traditional agriculture, and aeroponics is 70 percent more efficient than hydroponics. In times of war and natural disaster, there are no readily available food sources, so let’s think creatively on how we can grow food from — and in — the air.

- Bioprinting Meat: In 2016, it took 63 billion land animals to feed 7 billion humans. It’s a HUGE business. Land animals occupy one-third of the non-ice landmass, use 8% of our water supply and generate 18% of all greenhouse gases — more than all the cars in the world. Work is progressing on bioprinting (tissue engineering and 3D printing) to grow meat (beef, chicken and pork) and leathers in a lab. By bio-printing meat, we would be able to feed the world with 99% less land, 96% less water, 96% fewer greenhouse gases and 45% less energy.

- Shifting diets: Optimal health requires 10-20 percent of calories to come from protein. One example of innovative thinking comes from Africa, where farmers are installing fish ponds in home gardens, as the mud from the bottom of the pond also makes a great mineral-rich fertilizer. In the lab, scientists are investigating new biocrops.

This is just the beginning. If we are really serious about creating a vibrant ecosystem of sustainable food production, we need to be thinking exponentially and using technology to help create cost-efficient innovative solutions that can feed the world.

Atlanta To Host Agriculture Conference

Atlanta To Host Agriculture Conference

- Leslie Johnson

- For the AJC

4:49 p.m Monday, Feb. 13, 2017 Metro Atlanta / State news

Relationships built at the inaugural Aglanta Conference on Feb. 19 could help the city meet its goals of bringing local healthy food within a half mile of 75 percent of all Atlanta residents by 2020, said the city of Atlanta’s urban agriculture director, Mario Cambardella.

Urban and controlled environment agriculture innovation will be featured during the conference, which will take place at Georgia Railroad Freight Depot.

The purpose of Aglanta is to assist in Atlanta’s growth as a central hub in the nation’s annual $9 billion indoor farming industry, the city said in an announcement. Participants will include restaurateurs, grocers, architects, entrepreneurs, technologists, business owners and urban farmers for networking, sharing of best practices and making partnerships. The conference will include workshops and lectures, and cover urban agriculture business models and technologies, with a focus on vertical and indoor farming.

Information: https://www.aglanta.org/

Loudon Greenhouse Looks to Reimagine Farming With Automated Growing

By DAVID BROOKS

Monitor staff

Sunday, February 12, 2017

pecial clothing is often needed when you’re visiting a farm: Boots, gloves, hats, overalls, lab coats.

Lab coats?

“We wear lab coats in the greenhouse because this is where you could have the most contact with the plant material,” explained Henry Huntington, president and co-founder of the state’s most interesting new agricultural operation, the automated hydroponics greenhouse called Lef Farms in Loudon, as he helped a reporter and photographer put on protective garb – protective for the seedlings, not the people.

With coats, hairnets and gloves in place, Huntington and co-owner Bob LaDue pushed through the door from the operations center, where seven days a week machines carefully place tens of thousands of seeds into 40-foot trays modeled after rain gutters, and entered the 50,000-square-foot greenhouse that they hope will launch a bright new chapter in New Hampshire farming.

On this gray, snowy day, it is certainly bright in the literal sense, with hundreds of high-pressure sodium lights overhead going full blast to compensate for shortage of daylight coming through the glass.

“My goal is to make them think it’s June, every day. We’re feeding the plants photons,” said LaDue, who has been involved in greenhouse research and commercial operations for 20 years.

“We use as much natural light as possible since we don’t have to pay for that, and plan on about 80 percent of light coming from the sun over the course of the whole year,” he said. “Not on a day like today, though.”

A year’s production in less than a week

The bright lights in the vast open space gave the greenhouse the look of an airplane hangar, if you can imagine one with a floor that has been raised 5 feet and is made of salad greens.

How much salad greens? More than you can probably imagine.

LaDue said this 1 acre of hydroponics growing space will eventually produce 3,000 pounds of leafy greens, bagged and ready to be shipped to stores or restaurants, every 24 hours. After a few months of operation, Lef Farms (pronounced “leaf”) is running at about half speed as it tweaks the operation.

That’s a ton and a half daily of arugula, bok choy, mustard greens and lettuce, meaning that every day they expect to produce about one-third the annual production (depending on the crop) expected from an acre grown organically outdoors.

“We are very excited about it. This is the first large-scale farm of this kind designed for wholesale markets here in New Hampshire and the region,” said Lorraine Merrill, the state’s agricultural commissioner. “There have been proposals for this kind of production before that haven’t come to pass.”

Merrill said that indoor agriculture, with the promise of extending our growing season, can be an important part of the mix for state farming alongside traditional wholesale operations like dairy farms, smaller specialty farms, and direct-to-consumer sales via pick-your-own, farmers markets and community-supported agriculture projects.

“I really think one of the great strengths of New Hampshire agriculture is its diversity, and this adds to it. Diversity of types of crops and diversity of types of marketing channels – not putting all of our eggs in one basket,” she said.

The idea of farming indoors, with the aim of growing more produce on smaller plots that are closer to cities and can be harvested even during winter, is becoming realistic as technology improves. One Nashua family, for example, bought a “farm in a box” from the firm Boston Freight Farms and are raising greens for sale in a converted shipping container, with plants grown hydroponically (all the nutrients coming from water rather than soil) in rows of shelving, entirely dependent on light from LEDs.

Lef Farms isn’t quite that high-tech: It went with greenhouses and sodium lights for various cost and scale reasons. But this greenhouse is unlike any you’ve seen.

Greenhouse unlike most

Greenhouses have, of course, been part of New Hampshire agriculture for many decades. In fact, Huntington owns Pleasant View Gardens, which like Lef Farms has greenhouses built on a former gravel pit, where tons of flowers are grown a year. His experience there helped trigger the idea for Lef Farms.

“We have significant greenhouse productions of ornamental and flowering plants in New Hampshire, including D.S. Cole Growers and Pleasant View, two of the larger and most significant plant propagators in the country,” said Merrill.

What makes Lef Farms unusual is that it produces food crops and uses an extremely automated system that can plant, grow, harvest and bag the greens over a two-week growing cycle with little or no human labor.

Huntington and LaDue said this cuts labor costs – Lef Farms has a dozen full-time positions – and maximizes production. But they also say the precision of automation, in which the water used for hydroponics is fully recycled with its nutrients and fertilizers, reduces agricultural pollution from runoff compared to standard farms. The tightly controlled greenhouse, use of hydroponics and a fast growing cycle also greatly reduce the number of insect pests and the need for pesticides, as well as eliminating weeds and any resulting herbicides.

Whether it will be worth the reported $10 million investment remains to be seen. But they have plans to build several more greenhouses if all goes well, and they have town approval for up to 12 acres of operations.

Dirt put in gutters

Growing any crops starts with the soil. At Lef Farms, the soil has a brand name: Cornell Mix, developed at the university where LaDue did research for years. A mix of peat and vermiculite, it comes in 120-cubic-foot bales that double in size when decompressed and watered; specialized machinery from Finland distributes it carefully along the 40-foot-long gutters.

“A lot of the technology for this was developed in Scandinavian countries. They have so little light, the growing season is so short, and they’re trying to grow their own food; that has simulated their technology,” LaDue said.

Once loaded with this dirt, each gutter moves along a conveyer under a series of machines that drop in seeds; sometimes all of one species, sometimes a variety, although growing two species alongside each other is difficult, since they are harvested at the same time and thus must grow at the same rate, so that one species doesn’t shade out the other.

Each gutter then slides onto a huge pivoting arm that swivels and sends the chute through a hole in the wall into the greenhouse. This is done roughly 800 times every day – meaning that 800 other gutters are removed and harvested.

The gutter sits in darkness underneath the growing area for two days while the seeds germinate, before being pulled by on an enormous toothed belt up into the light. Over the next 14 to 19 days, depending on the crop, it will be pulled slowly from one end of the greenhouse to the other, roughly 300 feet, while the plants are fed by a constant stream of water containing a mix of micro- and macro-nutrients, made by blending various fertilizers.

“Bob’s kind of the mad scientist. He makes his own mixes,” Huntington said.

During this entire process, little to no human interaction will be required, although LaDue and others will be monitoring many factors – not just plants’ growth and health, but the building’s temperature, the total light as measured in moles (a unit you might remember from high school chemistry) of photons, its humidity and even its carbon dioxide level.

Even carbon dioxide must be balanced

That last factor is crucial, LaDue said. Plants breathe in carbon dioxide and during the winter, when the greenhouse lacks natural airflow through the heavily screened windows, they would use up most of the CO2, stunting growth, if it weren’t replaced.

Lef Farms produces CO2 as a byproduct of the gas-fired heaters, and even produces more than natural levels to boost growth, which enables them to cut back on lighting, one of their biggest costs.

“Supplement CO2 is another avenue to reduce supplemental lighting – we’re always trying to turn these lights off,” LaDue said. On a winter’s day, byproduct from heat can “save five to six hours of supplemental lighting.”

Lighting has also been a source of irritation to neighbors, who have complained to town officials about the brightness of the glow at night from this new presence in town. Lef Farms has said it will improve its use of shades to reduce the excess.

Getting the plants cold fast

Eventually the plants make it to the far end of the greenhouse, where conveyors transfer them, plants still growing, directly into the cooler, which is larger than some warehouses. Only inside the cooler do they get “a haircut” from automated blades, with salad greens automatically sorted on conveyer belts and dropped into a machine that puts them inside plastic bags. That’s all without human help – at least in theory; LaDue said the system is still being tweaked.

Bringing plants into the cooler while they are still growing is a key to maintaining freshness, said LaDue, who compared it to traditional harvesting.

“On most operations, you get them cut, it goes into bins, people are mixing them by hand. That’s not good,” he said. “The faster you get them cold, the better.”

And that’s not counting the benefit of being closer to our tables and stores. “Alternative to West Coast-grown greens” is a phrase that shows up a lot in their promotional material. LaDue claims that this system gives Lef Farms greens sold to retailers “shelf life like they’ve never seen before,” justifying a premium price.

Plenty of people around the state and the region will be watching, both to see if that belief holds up and to see what it means about our ability to feed ourselves in New England.

“I would expect we will probably see further developments, variations on this theme – in lots of different ways,” said Merrill, the agriculture commissioner. “Farmers are creative and resourceful; they’re always finding ways to make technology work for them.”

(David Brooks can be reached at 369-3313 or dbrooks@cmonitor.com or on Twitter @GraniteGeek.)

Light glows inside the Lef Farms greenhouses in Loudon last week. Elodie Reed photos / Monitor staff

Bob LaDue walks between growing salad greens at Lef Farms in Loudon last week. Elodie Reed—Monitor staff » Buy this Image

Lef Farms Vice President Bob LaDue explains how the Loudon greenhouse operation grows baby greens year-round last week.

Lef Farms President Henry Huntington walks past one of the many boxes that controls the company’s automated hydroponic growing system.

City of Atlanta to Host inaugural “Aglanta Conference”

The City of Atlanta will host its inaugural “Aglanta Conference” to showcase urban and controlled environment agriculture innovation in the City of Atlanta

City of Atlanta to Host inaugural “Aglanta Conference”

February 10, 2017 Valerie Morgan Local News, more news0

The City of Atlanta will host its inaugural “Aglanta Conference” to showcase urban and controlled environment agriculture innovation in the City of Atlanta.

The Mayor’s Office of Sustainability has partnered with Blue Planet Consulting, a firm specializing in urban agriculture projects, to bring together restaurateurs, grocers, architects, entrepreneurs, technologists, business owners and urban farmers to network, share best practices and establish partnerships. The conference will take place on Feb. 19 at the Georgia Railroad Freight Depot, and aims to help foster Atlanta’s growth as a central hub in the nation’s annual $9 billion indoor farming industry.

“We are excited about the inaugural Aglanta Conference and expect more than 200 industry leaders to attend,” said Mario Cambardella, the City of Atlanta Urban Agriculture Director. “The City of Atlanta recognizes the positive health and community outcomes of urban agriculture and will use this conference to foster relationships and partnerships which can ultimately help us meet our goals of bringing local, healthy food within a half-mile of 75 percent of all Atlanta residents by year 2020.”

In December 2015, Mayor Kasim Reed appointed Cambardella as the city’s first ever Urban Agriculture Director. Atlanta is one of a few cities in the nation with an Urban Agriculture Director, dedicated to working on food access generating policy, advocacy, and development. The Aglanta Conference will create an environment for participants to engage with a local, national and international audience. Through workshops, lectures, and networking sessions, the conference will cover issues across the spectrum of urban agriculture business models and technologies, with a particular focus on the emerging field of vertical and indoor farming.

During the conference, the Mayor’s Office of Sustainability will spotlight local champions already doing incredible work growing food as means of ecological restoration, social cohesion, cultural preservation, economic development and biopharmaceutical development.Partners for the conference include the Georgia Department of Economic Development, Georgia Power, Indoor Farms of America and Tower Farms.

To learn more about the conference or to register, visit: https://www.aglanta.org/

The Future Of Food Will Be Skyscrapers Filled With Plants

Milan is full of unusual sights. As the most populous city in Italy, and its main financial and industrial center, it’s a riot of color and design. But amid the skyline is a building that even for Milan is strange: The Bosco Verticale, or Vertical Forest, a skyscraper encircled with trees, finished in 2014.

The Future Of Food Will Be Skyscrapers Filled With Plants

02.08.17

Milan is full of unusual sights. As the most populous city in Italy, and its main financial and industrial center, it’s a riot of color and design. But amid the skyline is a building that even for Milan is strange: The Bosco Verticale, or Vertical Forest, a skyscraper encircled with trees, finished in 2014. The building was designed by acclaimed architect Stefano Boeri, and — if everyone from marijuana growers to Chinese investors get their way — will soon be as recognizable to urbanites as glass and steel towers are now.

Why? As cities expand, they destroy farmland, pump out smog, and fail to produce food. Parks, community gardens, and other green spaces can only do so much, and many foresee demand for food and the strain of climate change as an imminent danger. At the same time, we’re increasingly eager to know more about what we eat and where it’s coming from, and finding that information lacking. More and more people understand that everything we eat has a “footprint” and that the further your food travels, the more ecological damage it causes.

At the same time, as food-producing California faces water shortages that not even record precipitation can reverse, and climate change affects farmland across the world, shipping food from water-rich regions has become a vital necessity. Simply put, both consumer demand and environmental struggles mean that cities want their farms as close as possible to the populace, producing as much as possible (with as little water loss as possible), and while helping mitigate the pollution.

It’s a tall order. Literally.

Enter the vertical forest, like the afore mentioned building in Milan with more already in the works in Lausanne and Nanjing. The idea is simple: cities need more secure food supplies, more oxygen and to expand upward before gobbling up the land around them, so why not wrap skyscrapers in terraces that offer both, and build giant, towering farms that can feed thousands? The idea is undeniably ambitious, and so far, it’s little more than a proof of concept. But the concept works, and an unlikely industry is offering a path to expand it, thanks to a decision made thirty years ago.

In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan ordered law enforcement to begin helicopter flights that sprayed fields of marijuana with herbicide. The result? Marijuana operations began experimenting with hydroponics. Hydroponics are complex systems that allow farmers to grow plants indoors without soil. Instead, the plants are suspended in paper or mesh (or coconut husk) while a nutrient solution flows through the roots. Grow lights, powerful panels that turn out a replacement for sunlight, are used to offer the energy plants need to grow, with the result being an indoor, water-powered garden.

The hydroponics industry had plenty of other, more legal pioneers, such as the endless acres of Canadian hydroponics operations, but it was marijuana growers who worked on small, productive operations, and that expertise may be crucial to making vertical farms work.

Rick Byrd of PureAgro points out there are benefits well beyond just cutting down on fossil fuels: Vertical forests can deliver more than one harvest a year. As they’re indoors, there’s less of a pest problem, meaning less need for pesticides. And, with space at a premium, hydro operations can be build up, rather than having to grab for land.

These are expensive ideas, but marijuana — in the midst of a mega boom — means that growing operations can pioneer the technology, and then drive down the price to the point where you can grow anything with the same tech.

Byrd may find himself beaten to the punch by scientists, though. MIT recently debuted the Food Computer, an open-source system of computers and robotics that allows users to develop a “profile” for each plant they want to grow. Currently about the size of a shipping container, MIT’s team can see warehouse-sized facilities churning out specific types of food. With the robots doing the hard work, farming would be as simple as punching in the numbers and keeping an eye out for pests.

Hydroponics is not without its challenges. The nutrient solution, for example, is essentially pollution itself, and either needs to be reused or properly processed — although a well-run vertical farm offers better water management and control. Grow lights require enormous amounts of power, even with electron-sipping LED technology rapidly improving. And in a fit of irony, the plants outside these towers will need to be chosen carefully, as they might otherwise contribute to climate change.

But as a solution to a growing problem, vertical forests show that we should grow upward, not outward. Perhaps one day, the fields of the midwest will be filled with skyscrapers full of food, 50 stories tall, vastly increasing the available growing space.

The U.S.'s First Organic Farm REIT is Based in Evanston

The U.S.'s First Organic Farm REIT is Based in Evanston

By: DAWN REISS

Access to capital is notoriously difficult for farmers. Growing and raising certified organic food is even more daunting. That's because the USDA requires organic farmers to work the soil for three years before allowing them to certify their crops as organic. What's more, yields are lower for a good five years after starting out while the soil becomes richer.

To make the process easier, Dr. Stephen Rivard—former co-director of emergency medicine at Good Shepherd Hospital, and David Miller, former vice president for First Chicago Bank & Trust, created Iroquois Valley Farms to invest in land leased to farmers who convert conventional operations to organic. Rivard was spurred on in part because he saw patients hospitalized after coming into contact with pesticides.

Many younger farmers are looking for funding, says Miller, noting 72 percent of his private-equity firm's farmers are millennials. "The big guys don't operate there," he says, noting his average farm purchase is between 100 and 120 acres. "It's hard for family farmers to find funding to buy parcels of small to medium size. We are reactive to farmers looking for a specific piece of land. It's their business, and they come to us with a specific opportunity they want to finance."

A small group of 10 original investors has grown to 250—from 34 states and Canada and Great Britain—who converted their limited-liability company and began offering what they say is the first organic family farm real estate investment trust in the U.S. on Jan. 1, says Kevin Egolf, CFO of Iroquois Valley.

The Iroquois Valley Farmland REIT public benefit corporation, based in Evanston, includes 32 farms across nearly 4,500 acres in Michigan, Maine, New York, Kentucky, Montana, West Virginia, Illinois and Indiana; 73 percent of that acreage has transitioned into certified organic land. It has some $30 million in assets, with 41,500 shares valued at $568 per share, Egolf says. Compared to other private farmland funds and REITs that focus on conventional farming, Iroquois is small.

The concept blossomed after Miller purchased his uncle's 10-acre farm in Danforth, Ill., 30 miles southwest of Kankakee in Iroquois County, in 2005. Miller asked Harold Wilken—a local conventional-turned-organic fifth-generation farmer of Janie's Farm Organics, which grows hard and soft wheat, black beans, corn and soybeans—to look for other property that might become available.

Miller and Rivard, high school friends and college roommates at Loyola University Chicago, began with the $650,000 purchase of a 142-acre farm near Danforth in 2007, which they bought with eight friends and family members to start Iroquois. They followed that with an $800,000 investment for a nearby 160-acre farm in 2008.

Iroquois doubled its holdings from 302 acres in 2010 to four farms and 606 acres in 2011, in part, Miller says, after attending the Sustainable Responsible Impact Investing Conference, where Iroquois met with financial advisers. Soon after, Iroquois landed on a list of socially responsible private-equity and debt impact investment fund managers, a spot it's held for four consecutive years. That helped Iroquois scale its investments to 1,790 acres across 15 farms by the end of 2013 and 3,518 acres across 25 farms in 2015.

"There's no cookie-cutter approach," says Wilken, who sits on the company's board, owns shares and farms more than 2,000 acres among 16 farms. "Each family farm is structured differently. They aren't investing and only looking for a financial return. They are also looking to build up soil, build up the farmer and also be responsible stewards of the investments."

About 15 percent of Iroquois Valley Farms investment assets—five investments total—are mortgage finance offers to farmers, Egolf says, and the remaining 32 investments are in farmland the company owns and leases to organic family farmers.

Investments in farmland increased by $4.5 million to total $23.2 million in 2015, according to Iroquois Valley Farms' audited reports for 2014 and 2015.

TWO OFFERINGS ON TAP

Iroquois posted a net unrealized loss on investments in real estate of $312,018 in 2015 due to a decline in land value. "The market is a little soft right now," Egolf says. Since the audited report compares organic farmland to conventional farmland, which tracks the commodity market— something organics don't do since produce is sold at higher prices once it's certified—Egolf says it's not an accurate comparison, and it makes the organic farmland appear undervalued.

Later this month Iroquois will issue a $5 million to $7 million offering for "Soil Restoration Notes" to help pay millennial farmers to transition their land with short-term loans with a minimum of $25,000 buy-in amount for investors, Egolf says. The program is part of a three-year, $944,715 Conservation Innovation Grant the U.S. Department of Agriculture awarded Iroquois. Proceeds from the notes will help Iroquois' partner farmers increase profits while transitioning land to organic production and help Iroquois research how organic management practices affect soil health.

In April, Iroquois plans to issue a $15 million offering of REIT shares to accredited investors. Egolf says Iroquois will also issue two offerings for non-accredited investors in the third and fourth quarters of 2017 with a goal of raising at least $20 million. Aside from typical farm risk factors (weather, disease, labor), Iroquois cites reliance on tenants and the possibility that organic certification requirements could change.

The offerings come at a time when organic farming is becoming more popular and profitable, says Jeff Moyer, executive director of the Rodale Institute, a nonprofit research and education center. He cites a 2008-10 study conducted with Mississippi State University that found organic farms generate $558 in profit per acre, almost three times the $190 from conventional farming. Consumer demand for most organics is outpacing production growth, but investors have to decide if the trend will continue in the long-term, says Robert Johansson, the Department of Agriculture's chief economist. Because organic farming doesn't follow commodity prices, it can be more profitable, says Moyer, because farmers can help set the price and value of an organic product.

In 2015, a little more than 2 million farms were left in the U.S., and 14,861 certified organic farms with 5.3 million acres—up from 12,941 farms and 4.8 million acres in 2008—according to the USDA. While the number of certified organic farms in Illinois increased to 218 in 2015 from 50 in 2008, the number of acres decreased to 27,275 in 2015 from 35,887 in 2008.

Iroquois partners say that bodes well for the company's prospects as demand increases. "They aren't making more farmland," says Arne Lau, Iroquois chief operating officer. "We will always need food, and sustainable farming practices are critical."

AgTech Investing Report - 2016

Agtech funding figures dipped to $3.2 billion in 2016 from $4.6 billion in 2015. This reflected the broader pullback in global venture markets, though deal activity in agtech was the strongest to date with 580 deals closed

AgTech Investing Report - 2016

Agtech funding figures dipped to $3.2 billion in 2016 from $4.6 billion in 2015. This reflected the broader pullback in global venture markets, though deal activity in agtech was the strongest to date with 580 deals closed.

The year 2016 was full of contrasts. While global VC investment fell 10%, total investment in agtech fell to $3.2 billion - a 30% drop from 2015, but well ahead of 2014. Interestingly, global VC deal activity declined 24%, but it was agtech’s busiest year to date with a 10% increase in the number of deals closed year-over-year. This was largely the result of new support from the growing number of accelerators and other early stage resources dedicated to food and agtech startups.

The dip in dollar funding in 2016 was due in part to a cooling off in investor interest in drones, food delivery, and bioenergy, and also because of a few large financings in 2015 that drove numbers. However, four of our nine sectors showed an uptick in activity, and Seed and Series B investment came in particularly strong.

Exits remained a talking point among VCs as M&A activity from the large agribusinesses remained far too low. 2017 is already looking a lot brighter for global VC, however, and we expect growth in agtech driven by investor interest in supporting the future of food and agriculture.

Women In CEA Startups

Interest in furthering the development of controlled environment agriculture (CEA) is propelled forward by the idea that we can create real solutions to some of humanity’s basic needs: like growing nutritious food. By bringing farming under cover, be that in a hoophouse, greenhouse or vertical farm, we have found ways to closely monitor and manipulate growing conditions

Women In CEA Startups

Meet 4 female trailblazers raising the bar in controlled environment agriculture through entrepreneurship.

January 25, 2017

Cassie Neiden

Interest in furthering the development of controlled environment agriculture (CEA) is propelled forward by the idea that we can create real solutions to some of humanity’s basic needs: like growing nutritious food. By bringing farming under cover, be that in a hoophouse, greenhouse or vertical farm, we have found ways to closely monitor and manipulate growing conditions. These efforts have resulted in extended growing seasons — all while improving food access, flavor and local economies.

But CEA’s improvements do not stop there. As this dynamic, ever-changing industry continues to adapt and evolve, new ideas coming to the forefront aim to solve challenges and streamline systems. Unsurprisingly, many of them are coming from women, who asking the simple question: Why not?

Why not integrate greenhouse data into a user-friendly platform? Why not ask if an abandoned garden needs a revamp? Why not grow clean, healthy greens in the comfort of a home? Why not make a greenhouse three stories tall?

On the following pages, we feature determined, inspiring women who are finding CEA success through their innovations and leadership.

Allison Kopf, Founder & CEO, Agrilyst

DATA-DRIVEN: Kopf put together a team of highly skilled data scientists and engineers to form Agrilyst, an intelligence software platform for indoor farmers, in 2015. Agrilyst utilizes algorithms to track and record data from sensors throughout the greenhouse to help growers better understand their operation’s metrics to improve plant quality and output.

Since the company’s conception, Kopf and her 10-member team have nabbed first place in TechCrunch Disrupt’s prestigious technology startup competition, raised more than $1 million in investments for development, secured customers in five countries, and in January, launched Agrilyst Reporting, which helps growers curate their own customized data sets.

“We’re helping [growers] visualize data like never before,” Kopf says. “Big data is just a [phrase], but having insights and having meaningful visualizations is important to growers, so we’ve spent a lot of time focused on that.”

BRIGHT IDEA: Based in the startup central, NYC, Kopf has experience in helping to build companies. Before founding Agrilyst, she spent four years as the Real Estate and Government Relations Manager at BrightFarms, a hydroponic grower and greenhouse builder in New York. She was one of the first employees at the company back in 2011.

“It was a really easy jump for me to say, ‘I want to be in this startup world, and I want to do something that I believe in and work alongside a team on something that’s a big problem that’s solvable by us,’” she says.

In fact, much of the idea for Agrilyst came from her time at BrightFarms. “When I was on the operating side, my job was to essentially solve problems as they came up. And that was really challenging to do because we had fragmented data systems,” she says.

Essentially, climate control systems and other technological advances provided data to the growers — but they had no comprehensive way of gathering and analyzing it. “I said, ‘That’s it. We can’t do this anymore. We have to find a way to log this data somehow,’” Kopf says. “I can build this platform to integrate this data and build a team of people smarter than me to get [growers] insights into that data.” And Agrilyst was born.

Kopf's startup advice is to make yourself an expert in your field, but don't go it alone. "It wastes time and money, especially in this space," she says.

LEVELED OUT: Part of Kopf’s success in the male-dominated technology space is due to her mindset. She was the only woman in her physics class in college; she’s spearheaded a legislative campaign; and also fearlessly pitched her business model to venture capitalists. No matter the space she’s in, she refuses to be intimidated based on her gender because she simply doesn’t factor it in.

“The way that I approach it is that I’m there because I’m the person to do this,” Kopf says. “I presented the company that I had built because I was the right person to build this company. This [is] the thing I was put on this earth to solve. That’s the way I operate … I’ve made myself the expert in the thing I’m doing, and that’s the only [way] you can have confidence standing up there and presenting something that’s yours, in my opinion.”

BORN LEADER: While Agrilyst takes up much of Kopf’s time, she hasn’t shied away from additional professional leadership opportunities. She’s an advisor for a nonprofit to promote young women’s involvement in tech called #BUILTBYGIRLS, as well as a mentor for Square Roots Urban Growers, a hydroponic vertical farm builder. Kopf was also named Entrepreneur of the Year by Technical.ly Brooklyn, and Changemaker of the Year by the Association for Vertical Farming earlier this year.

So it’s no surprise that her favorite part of starting a business is building a team.

“I get to work with people who are tremendously brilliant and interesting, especially in our space,” she says. “And we have not yet hired from a job posting. We’ve consistently hired through our team’s network. But what we’ve done a very good job at is expanding our network broad enough to find [those] people … and make sure we incentivize them to put them on our team.”

Kopf’s also a huge proponent of hiring people of diversity. Agrilyst’s small team is made up of employees from many different backgrounds, and an even split of men and women. “It makes your company and product better, too, by having diversity and by having people who don’t look and think and speak like you do. By nature, you end up building a product that’s more inclusive for a broader set of customers,” she says. “Not ignoring colorblind people when you are building the colors of your platform; not ignoring left-handed folks when you’re building an iPad that doesn’t switch the right way … All of those things can be included earlier by broadening your community.”

BIGGEST CHALLENGE: Opportunities abound with any startup as it morphs into its own identity. So Kopf’s biggest challenge is keeping the company focused. “There are so many areas of agriculture that have a data problem,” she says. “This is why you see so many data companies sprouting up in the outdoor space — or cash commodities crops … It’s one of our biggest industries.

“But as a startup, and as 10 people,” she continues, “you can’t tackle every problem.” She says she’s proud of the way Agrilyst communicates with indoor growers, listening to them and building on what they want to see.

THE BOTTOM LINE: The most rewarding aspect of Kopf’s job is realizing results from what she and her team have created. “Seeing something physically change, or seeing operational management methods change based on using our platform and how that makes a grower able to reach profitability, or expand operations, or open a new facility, or expand into new crops — that, to me, is probably the most successful thing that we could possibly do,” she says.

Vanessa Hanel, Owner & Operator, Micro YY

TINY PRODUCT, BIG OPPORTUNITY: After working on the administrative side of the Calgary Farmers Market for about a year and a half, Hanel decided she wanted to be the grower, not the one sitting behind the desk. So in the basement of her home in Calgary, Alberta, Hanel launched Micro YYC and began to grow a plethora of microgreens varieties and other leafy greens for multiple clients, including a large local farmers market, a CSA-inspired subscription service, and local restaurants and specialty grocers. Hanel’s offerings include pea shoots, broccoli, kale, kohlrabi, arugula and other microgreen blends. “I’m super passionate about quality, delicious food,” Hanel says. “So it makes me happy every day to be growing these happy little sprouts.”

COMMUNITY COLLABORATION: One of Hanel’s biggest accounts is a cooperative with other local growers called YYC Growers’ Harvest Box. On a bi-weekly basis, customers can pick up a “harvest box” that includes a selection of seasonal produce from several different farms in the area. Hanel says not only does this bring her a good amount of business — the collective has grown exponentially from 80 shares in 2015 to more than 500 in 2016 — it also gives her a sense of belonging. The farmers frequently get together for meetings and potlucks and lean on each other for advice and moral support. “It makes you realize you’re not the only one doing something weird for a job,” she jokes.

SOCIAL STANDING: As a one-woman operation, Hanel says she hasn’t had much time to craft a website, but she’s acquired plenty of customers and mentors through social media marketing to keep her going. Every restaurant she’s worked with has found her either on Twitter or Instagram, and she’s acquired some helpful growing advice along the way.

Hanel's microgreens are sold to YYC restaurants and farmers markets.