Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

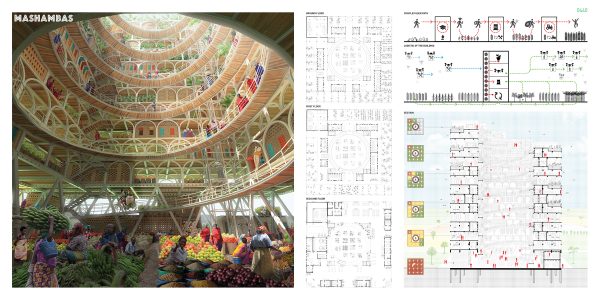

Mashambas Skyscraper

Mashambas Skyscraper

BY: ADMIN | APRIL - 10 - 2017

First Place

2017 Skyscraper Competition

Pawel Lipiński, Mateusz Frankowski

Poland

Mashamba– Swahili, East Africa

An area of cultivated ground; a plot of land, a small subsistence farm for growing crops and fruit-bearing trees, often including the dwelling of the farmer.

Over the last 30 years, worldwide absolute poverty has fallen sharply (from about 40% to under 20%). But in African countries, the percentage has barely fallen. Still today, over 40% of people living in sub-Saharan Africa live in absolute poverty. More than half of them have something in common: they’re small farmers.

Despite several attempts, the green revolution’s mix of fertilizers, irrigation, and high-yield seeds—which more than doubled global grain production between 1960 and 2000—never blossomed in Africa, because of poor infrastructure, limited markets, weak goverments, and fratricidal civil wars that wracked the postcolonial continent.

The main objective of the project is to bring this green revolution to the poorest people. Giving training, fertilizer, and seeds to the small farmers can give them an opportunity to produce as much produce per acre as huge modern farms. When farmers improve their harvests, they pull themselves out of poverty. They also start producing surplus food for their neighbors. When farmers prosper, they eradicate poverty and hunger in their communities.

Mashambas is a movable educational center, which emerges in the poorest areas of the continent. It provides education, training on agricultural techniques, cheap fertilizers, and modern tools; it also creates a local trading area, which maximizes profits from harvest sales. Agriculture around the building flourishes and the knowledge spreads towards the horizon. The structure is growing as long as the number of participants is rising. When the local community becomes self-sufficient it is transported to other places.

The structure is made with simple modular elements, it makes it easy to construct, deconstruct and transport. Modules placed one on the other create the high-rise, which is a form that takes the smallest as possible amount of space from local farmers.

Today hunger and poverty may be only African matter, but the world’s population will likely reach nine billion by 2050, scientists warn that this would result in global food shortage. Africa’s fertile farmland could not only feed its own growing population, it could also feed the whole world.

Good Food 100 Restaurants List to Highlight Sustainable Restaurants

Starting in June, consumers will be able to choose a place to eat based on a restaurant’s sustainability rating, indicated by a number of “links.” These links are the mark of a new restaurant survey, rating system, and list called The Good Food 100 Restaurants™.

Good Food 100 Restaurants List to Highlight Sustainable Restaurants

Starting in June, consumers will be able to choose a place to eat based on a restaurant’s sustainability rating, indicated by a number of “links.” These links are the mark of a new restaurant survey, rating system, and list called The Good Food 100 Restaurants™. The project aims to increase transparency surrounding sustainable business practices that benefit the environment, plants and animals, producers, purveyors, restaurants, and eaters.

The Good Food 100 Restaurants rating system measures chefs’ purchasing practices and determines the extent to which they are supporting local “good food” economies. The ratings are determined based on self-reported annual food purchasing data from a survey completed by participating chefs and restaurants. Any restaurant or food service operation in the United States, ranging from fast casual to fine dining, is eligible to take the survey.

A number of links—from two to five—will be awarded to each restaurant based on their performance as compared to similar survey participants. The inaugural list and ratings will be available to the public, along with an economic analysis report by the Business Research Division of Leeds School of Business at the University of Colorado Boulder, in June 2017 on The Good Food 100 Restaurants website.

Food Tank caught up with Sara Brito, the co-founder and president of The Good Food 100 Restaurants, to find out how this new system will affect the food world.

Food Tank (FT): Can you explain how the Good Food 100 Restaurants rating system works?

Sara Brito (SB): The Good Food 100 Restaurants is an annual list of restaurants spanning from fast casual and fine dining to food service that seeks to redefine how chefs, restaurants, and food service businesses are viewed and valued. The ratings focus on the quantitative measurement of chefs’ purchasing practices, which are based on the percentage of total food purchases spent to support local, state, regional, and national Good Food producers and purveyors compared to similar-type participating restaurants in the same region.

FT: Why did you see a need for the rating system now?

SB: Chefs are among the most trusted influencers in society today. According to the 2014 Edelman Trust Barometer, chefs are more trusted than doctors or lawyers. Until now, most of this recognition and influence has been based on the subjective standards and opaque criteria designed to reward chefs and restaurants (including food service) for how their food tastes.

I believe that good food is good for every link in the food chain. Now, more than ever, with sustainability and transparency being at the center of the industry and mainstream cultural conversation, eaters are demanding to know where their food comes from.

FT: How will this tool affect diners?

SB: The Good Food 100 will educate and inform eaters about the restaurants that are transparent with their purchasing and sustainable business practices.

FT: What will chefs gain from participating?

SB: By participating in the Good Food 100 Restaurants survey, chefs will be recognized and celebrated for being transparent with their purchasing practices. In addition, they will be contributing to a new, first-of-its-kind national economic assessment that aims to measure how restaurants are helping to build a better food system by supporting local, state, regional, and national ‘good food’ economies. Their participation will also help establish benchmarks for different types of restaurant and food service businesses across the country in order to help them understand and evolve their purchasing practices to help build a better food system.

How many chefs and restaurants will be included in the inaugural rating? Any notable names?

SB: The list of chefs and restaurants that have committed to taking the survey includes: Mike Anthony (Gramercy Tavern, Untitled, Union Square Hospitality Group), Rick Bayless (Frontera, Tortas by Frontera), Alex Seidel (Fruition, Mercantile & Provisions), Kelly Whitaker (Basta), Suzanne Goin (Lucques, A.O.C., Larder), Hugh Acheson (5 & 10), Jennifer Jasinski (Rioja), Jonathon Sawyer (Team Sawyer Restaurants), William Dissen (The Marketplace Restaurant), Stephen Stryjewski (Cochon, Butcher, Herbsaint, and Peche), Steven Satterfield (Miller Union), Paul Reilly (Beast + Bottle and Coperta), David LeFevre (Manhattan Beach Post, Fishing With Dynamite, and The Arthur J), Andrea Reusing (Lantern and The Durham), Renee Erickson (Walrus & Carpenter, The Whale Wins, Barnacle Bar, Bar Melusine, Bateau, General Porpoise), Bill Telepan (Oceana), and many more.

FT: Do you see this rating system changing the way the restaurant industry works? How?

SB: The Good Food 100 Restaurants ratings aim to redefine how chefs, restaurants, and food service businesses are viewed and valued. The rating system will also help establish benchmarks for different types of restaurant and food service businesses across the country in order to help them understand and evolve their purchasing practices to help build a better food system.

FT: What do you hope will happen with Good Food 100 Restaurants in the next 5 or 10 years?

SB: Like the Inc. 100 and Fortune 100, the Good Food 100 Restaurants is not limited to 100 restaurants. In the future, the full list could be 100 to infinity.

Urban Farm In Victoria Expands, Hopes To Grow 10,000 lbs Of Produce

Urban Farm In Victoria Expands, Hopes To Grow 10,000 lbs Of Produce

Topsoil’s new space includes 15,000 square feet to grow fresh produce and offers more sun exposure. Apr. 7, 2017 (CTV Vancouver Island)

CTV Vancouver Island

Published Friday, April 7, 2017 6:33PM PDT

Last Updated Friday, April 7, 2017 6:49PM PDT

A Victoria food producer is expanding its operation at Dockside Green after growing more than 7,000 pounds of produce last year.

Topsoil’s new space includes 15,000 square feet to grow fresh produce and offers more sun exposure.

The urban farm hopes to grow more than 10,000 pounds of produce in 2017.

The local food producer works with chefs in Victoria at the beginning of the season and customizes what it grows based on what the chefs need.

The founder of the business says the open site allows them to operate in full transparency.

“We’re being watched 24/7 and it gives us accountability and responsibility to produce the best, highest quality, safest, most nutritious produce possible for the city,” said Chris Hildreth.

Topsoil is working with four restaurants this year, including Caffe Fantastico, Fiamo Pizza & Wine Bar, Canoe Brewpub and Lure Restaurant & Bar.

The restaurants are so close the local food producer guarantees delivery in under 10 minutes.

The executive chef at Lure Restaurant & Bar says it’s important to support local farms.

“We think here on Vancouver Island there’s a huge market for it, there’s obviously a lot of production happening here as well,” said Dan Bain. “We don’t see a lot of reason to bring in vegetables from areas further away.

Trumbull Conference Learns How Cleveland Man Went From Crime To Award-Winning Wine

Trumbull Conference Learns How Cleveland Man Went From Crime To Award-Winning Wine

Mansfield Frazier proudly displays a 2014 bottle of his Traminette Vigonier, which came in second place at the Geauga County Fair. (Photo credit: Margaret Puskas)

Published: Sat, April 1, 2017 @ 7:03 p.m.

WARREN

When advocates of urban farming cite success stories, one of the first names they offer is Mansfield Frazier. The 73-year old took a vacant plot of land and turned it into an award-winning vineyard in the least likely of places—Hough, a predominately black community in desperate need in Cleveland’s inner city.

How Frazier wound up growing grapes seems just as unlikely as his vineyard. He had been in and out of prison multiple times – all for the same crime.

“I was a professional [credit card] counterfeiter and served five terms,” he said. He later settled down, married and became a community activist, writer and host of a radio program.

Speaking at the Growing Gardens Leadership Conference sponsored by the Trumbull Neighborhood Partnership Saturday, Frazier regaled his rapt audience with his tale of turnarounds – the community’s and his own.

“It’s called the ‘Vineyards of Chateau Hough’ and that’s a political statement,” he said. “It shows that the land we occupy is just as valuable as Westlake,” an affluent Cleveland suburb.

What did Frazier know about grape-growing or urban farming before he started? “Nothing,” he said, “but I always had an interest in nature.”

Frazier said experts at the Ohio State University Extension Service suggested two types of grapes that could flourish in Ohio’s unforgiving winters. He went along with their advice, but took it one step further. He was able to secure grants for the vineyard by making it a “re-entry project” because his workers are men transitioning from prison sentences.

“I wanted them to know there is life after prison, but they have to work for it,” he said.

Chateau Hough is actually bottled by a winery in Solon that produces nearly 1,000 bottles, but Frazier said a small winery is under construction near his vineyard. When completed, he said, the number should increase to 20,000 bottles.

“This isn’t just about grapes,” he said. “It’s about saving inner cities and the people who live in them.”

Matt Martin, TNP executive director, said Frazier’s story shows why commitment is necessary for community gardens to be successful. He estimates there are nearly 20 such vegetable and fruit gardens in Warren, each offering more access to fresh food.

“We provide logistical support and help them pursue funding, but we expect them to be self-sustaining,” he said.

Sarah Macovitz of Youngstown, a therapist and the leader of a vegetable garden on Laird Northeast in Warren, agreed. “You have to have a buy-in,” she said.

Michelle Maggio of Warren, a student who helped develop a garden project on Warren’s east side, said she identifies with what she considers to be urban gardening values. “It’s innovative and sustainable,” she said. “It’s a way to make a positive transformation.”

In Frazier’s case, there was more than sustainability with his vineyard. In a 2013 blind taste test competition involving several hundred wines, Chateau Hough’s Traiminette, a white wine, took second place.

Photo courtesy of SKYvantix

Bring Back South Central Farm

Bring Back South Central Farm

South Central Farm Restoration Committee Los Angeles, CA

Once the largest urban farm in the United States, spanning 14 acres and feeding 350 families in the midst of an industrial and residential landscape, the South Central Farm was an oasis flourishing from 1992 - 2006.

Our Mission:

Farmers and supporters have formed the South Central Farm Restoration Committee with the intention to #BuyBackTheFarm. Our goal is to secure the farm and protect one of the last and largest remaining undeveloped parcels of land in LA County. With a land trust in place the farm would be a permanent jewel for the city of LA’s sustainability and green endeavors.

Current Landowner:

Today the land is owned by the PIMA Alameda Partners, LLC, a clothing conglomerate (Poetry, Impact Mfg., Miss Me, Active Basic USA) – with plans to develop the parcel into a retail manufacturing and warehouse facility. With literally hundreds of comparable sites in the LA metro area to choose from, selling the parcel back to the South Central Community will allow for PIMA to be part of the solution for a greener Los Angeles.

The South Central Farm is securing pledges with partners who are ready to step up with funding if PIMA becomes a willing seller.

How to Help:

In addition to signing the petition, join the conversation online through following @BringBackSCFarm on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. You may also send a Letter of Support to the to the City Council. In the coming weeks we will share community events and powerful opportunities to lend your valuable support. You can email the campaign directly: BringBackSCFarm@gmail.com

The South Central Farmers have continued their mission and currently sell organic produce at 10 Farmers Markets throughout Los Angeles, as well as drop-off CSA boxes in over 15 locations (which we encourage you to visit).

Widespread Support:

Response to the initial phase of the campaign has been strong with widespread support from respected leaders and celebrity advocates like: Daryl Hannah, Scottie Thompson, Shailene Woodley, Nicole Richie, Ian Somerhalder, Van Jones, Moby, and others.

Closing:

Restoring the farm to it's original location will help grow community involvement and cultural celebration through its programs and park facilities. It will provide more oxygen and less pollution as well as lower greenhouse gasses in one of the dirtiest air corridors in all of Los Angeles, and it will grow the idea in people’s hearts and minds that if you work hard enough for something it will bloom.

This petition will be delivered to:

- Miss Me (Sweet People Apparel Inc.)

Young Cho

Lindsey Shute, National Young Farmers Coalition: "We need empathy"

Lindsey Lusher Shute, Executive Director and Co-Founder of the National Young Farmers Coalition (NYFC), is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery,” which will be held in collaboration with Tufts University and Oxfam America on April 1, 2017

Lindsey Shute, National Young Farmers Coalition: "We need empathy"

Lindsey Lusher Shute, Executive Director and Co-Founder of the National Young Farmers Coalition (NYFC), is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit, “Investing in Discovery,” which will be held in collaboration with Tufts University and Oxfam America on April 1, 2017.

With a background in organizing and state policy, Lindsey co-founded NYFC as a platform for young, progressive farmers to have a meaningful influence on the structural obstacles in the way of their success. Lindsey is a respected speaker and an expert on the structural issues facing family farms. In 2014, she was named a “Champion of Change” by the White House. In addition to her work with NYFC, Lindsey is co-owner of Hearty Roots Community Farm in Tivoli, New York.

Food Tank had a chance to speak with Lindsey about her background and inspiration, as well as the opportunity for talented and ambitious young farmers to inspire food system change.

Lindsey Lusher Shute is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit.

Food Tank (FT): What originally inspired you to get involved in your work?

Lindsey Shute (LS): I started organizing with young farmers because of the challenges that my husband Ben and I faced in growing our own farm. As we met more and more farmers who were facing similar struggles across the nation, I realized that we lacked a political voice. There were too many young people with the ambition and will to farm, but without a way to get there.

FT: What makes you continue to want to be involved in this kind of work?

LS: I have a constant source of inspiration and motivation in the people that I work to represent: young farmers. These farmers are out to change the country by growing great food, taking care of the soils and water that they depend on, and daring to compete as small farmers in a highly consolidated food system. The risk that these farmers take on behalf of their communities keeps me going. I want them to succeed, and I know what they’re up against.

I’m also encouraged by our bi-partisan traction and success at cutting through partisan divides. Just a few weeks ago, Rep. Glen Thompson (R-PA) and Rep. Joe Courtney (D-CT) reintroduced the Young Farmer Success Act (H.R. 1060) to add farmers to the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program. These co-sponsors were joined by two additional Republicans and two additional Democrats. These actions demonstrate how farming can be unifying—and a way to overcome national divisions in favor of help for ordinary people.

FT: Who inspired you as a kid?

LS: My two grandfathers were rural ministers and World War II chaplains. As a child, they served as beacons of service, faith, and devotion to community that I can only hope to achieve. When I would attend my family’s church in southeast Ohio as a child, the day would be filled with stories from church members about how my grandfather made a difference in their lives. One particular story that stuck with me is about a neighbor boy who repeatedly robbed my grandfather’s farmhouse. Over the course of months, electronics went missing and eventually my grandfather’s gun. After the kid went to jail on other counts, my grandfather repeatedly visited him and expressed his forgiveness and hope for the kid’s future.

FT: What do you see as the biggest opportunity to fix the food system?

LS: The biggest opportunity lies in the talent and ambition of young farmers. If they’re given a real chance of success—land to own, sufficient capital, healthcare, and appropriate technical support—they will thrive and change the food system through their entrepreneurship. The candidate for Secretary of Agriculture, Sonny Purdue, can leverage this new talent by directing the USDA to stand by young people in agriculture.

FT: Can you share a story about a food hero who inspired you?

LS: Leah Penniman is one of my food heroes. Last spring I gave a short, public talk about why we have lost so many farmers in the United States and I failed to speak to the effects of racism. Leah, in the audience at the time, rightly let our team know that my narrative was incomplete. Her willingness to speak up in that moment and to continue dialogue with our team led to the development of a racial equity program at NYFC—as well as more farmers of color identifying with and joining the coalition. Leah helped me in that moment and I am deeply grateful for her strong voice and leadership.

FT: What’s the most pressing issue in food and agriculture that you’d like to see solved?

LS: With the massive cuts proposed at USDA, healthcare access for farmers on the brink of collapse, and immigration enforcement threatening the farm workforce, it’s hard to ignore the myriad of rural issues created by the Trump Administration. But outside of these immediate policy crises, the nation must address the issue of affordable land access for farmers. In the next 20 years, two-thirds of the farmland in the United States will change hands as our aging farm population retires. How that land transitions will set the stage for the future of our food system. If we provide access for working class, small farmers, we will promote economic vitality, national security, and sustainability.

FT: What is one small change every person can make in their daily lives to make a big difference?

LS: Practice empathy. In so many of the political discussions that I’ve been hearing recently, there has been so much antipathy for people facing struggle. We critique immigrants who, like most of us, came here for good work and opportunity. We call out folks who couldn’t afford healthcare before the Affordable Healthcare Act, and we undermine government programs that stoke innovation in areas of the country where mobility and economic agency have grown dim. I believe we need smart government programs that leverage best practices in technology and management, but I also want a government that stands by the principles of empathy and compassion for our neighbors. To get there, we need empathy. And to practice empathy, we probably need to drop our phones and make time for conversation with people outside our immediate circles.

FT: What advice can you give to President Trump and the U.S. Congress on food and agriculture?

LS: Agriculture is the wealth of the nation, and a large part of our national security. Although so few Americans are now farming, these farmers have an outsized impact on the nation’s health and prosperity. We need to invest in their futures and ensure that we are supporting smaller farms that minimize risk, make our economy more resilient, and keep dollars in rural communities.

Lindsey Lusher Shute is speaking at the inaugural Boston Food Tank Summit.

Consider Urban Agriculture In National Policy Development

Consider Urban Agriculture In National Policy Development

By Joyce Danso, GNA

Accra, March 29, GNA – The Peasant Farmers Association of Ghana on Wednesday implored government to include Urban Agriculture (gardening) in its policy of “Planting for Food and Jobs” to curb unemployment among the youth.

Mrs Victoria Adongo, Programmes Coordinator of the Association also appealed to government to encourage backyard gardening which boosted food production when the “Operation feed yourself” was introduced some year ago.

Mrs Adongo who was speaking at a National Forum on Local Seeds, Nutrition and Urban gardening held in Accra noted that 200 million people were involved in urban agriculture worldwide and that had contributed to the feeding of 800 million urban dwellers.

According to her, Urban Agriculture had been branded as compliment in the urban food supply with 40 per cent of the population in Africa engaged in the practice.

The programme jointly held by Centre for Indigenous Knowledge and Organisational Development (CIKOD) and the Peasant Farmers Association of Ghana is aimed at drawing public attention to seed diversity for nutrition, health and wealth.

The forum also sought to create awareness on the impact of agro-chemicals on the environment and food quality and educate the public on nutritive potentials of our local seeds, food and the importance of biological agriculture in urban gardening.

Mrs Adongo noted that urban agriculture maintained biodiversity, ecosystem and provided climate resilience and temperature control in urban and peri-urban areas.

According to the Programmes Coordinator, the concept was however plagued with challenges such as increasing population and urbanisation and the threat of Commercial food production.

She noted that access to land or space by estate developers, competition for water, lack of storage facilities, and conflict on lands were some of the militating factors against urban agriculture.

She called for the institutionalisation and integration of urban agriculture into the country’s economic development agenda.

“Estate Developers should also be entreated to allocate portions of lands for community gardening to boost food production and promote social cohesion.”

Mr Bernard Guri, Executive Director, CIKOD, noted that over the years the focus had been on provision of seeds and chemical fertilizers for increased yield without much concern for dietary diversity for nutrition and health.

Mr Guri noted that those policies had rather resulted in pollution on the environment and water bodies which affected the health of many people.

He said it was therefore important to promote seed diversity and food nutrition.

Mrs Grace Dzifa Wornyoh, Clinical Dietician said no single food could give one all the nutritional needs and called for the consumption of balanced diets to ensure growth.

Mrs Wornyoh contended that the power of nutrition should not also be underestimated noting that under nutrition and over nutrition were the causes of some ailment in the country health problems.

The Clinical Dietician listed urbanisation, income, education and the media as factors affecting dietary diversity.

She suggested the creation of backyard farming as well as promoting improved technology for the preservation of food.

Mrs Wornyoh was of the opinion that nutrition should be a course in educational institutions in order to promote good eating habits.

GNA

The Regeneration Hub: Mapping the Regeneration Movement

The Regeneration Hub: Mapping the Regeneration Movement

Alexandra Groome is on the coordination team of Regeneration International (RI), a project of the Organic Consumers Association. Alexandra Groome launched The Regeneration Hub with Scott Funkhouser during the 2016 Climate Summit in Marrakech, Morocco. Katherine Paul is associate director of the Organic Consumers Association.

We, the inhabitants of Planet Earth, face multiple and accelerating global crises, including poverty, hunger, deteriorating public health, social, and political unrest. These crises are in large part a consequence of global warming, driven in part by over-consumption and irresponsible stewardship of Earth’s resources, especially its soils.

It’s fair to say that if we allow the degradation of our soils and land to accelerate, or even to continue at their current pace, these crises will only intensify.

How do we reverse course? By reducing runaway consumption and adopting agricultural and land-use practices that regenerate the world’s soils, and in so doing, regenerate local food and farming systems, local economies, human health and even our democracies.

Individuals and groups around the world are researching, launching, testing, and promoting agricultural and land-use projects that hold great promise for addressing our impending global warming crisis. (For more on how regenerative agriculture is key to cooling the planet and feeding the world, check out these resources).

To connect these local “regenerators” so they can exchange research and share expertise with others working in faraway places, and thereby propel the acceleration of regeneration, on a global scale, Regeneration International (RI), Open Team, and a coalition of 17 other organizations leading the regenerative food and farming movement have launched the beta version of The Regeneration Hub(RHub). RHub is an open platform that aims to accelerate the regeneration movement by encouraging collaboration among various groups and individuals focused on regenerative projects involving reforestation, seed saving, holistic land management, permaculture gardens, and agroecology networks.

Creating a digital platform to spread the message of regeneration

The idea for RHub came about during the 2015 COP21 Paris Climate Summit, as representatives of RI, Open Team, and others brainstormed ways to better connect those working within the regeneration movement. Eleven months later, RHub was launched (still in beta version) during the 2016 United Nations Climate Summit in Marrakech.

Though still in the early stages, RHub has signed on more than 90 regenerative projects. In an effort to kick-start the program, RI will award five US$1,000 grants to fund innovative regeneration projects around the globe. To apply for the call-for-projects, “Five Innovations for Regeneration,” applicants must register a project on Rhub.com and complete an online profile by March 31, 2017.

“There are regenerative solutions all around us,” said Ronnie Cummins, co-founder and international director of the Organic Consumers Association and RI steering committee member. “But people are working in silos. We need to map out and connect the global regeneration movement in order to speed up the exchange of best practices and the sharing of knowledge and resources on a global scale,” he said.

Meet the projects signed on to RHub

Here is just a sampling of projects that are already using RHub to connect with fellow regenerators:

Terra Genesis International (TGI), based in the U.S., is a RHub project dedicated to reversing climate change by transforming US$100 billion in purchasing power and 500 million hectares of land into regenerative agriculture. The folks at TGI are experts when it comes to designing regenerative farm landscapes that increase nutrient-dense food production and improve livelihoods.

Worldview Impact, based in India, is a global social enterprise that provides made-to-order services for cooperatives of small-scale organic farmers in developing countries. Worldview Impact’s goal is to integrate and expand farming systems that integrate agroforestry, bring local products to market, and create market linkages with the emerging sectors of regenerative supply chains and agro-ecotourism. Worldview Impact is in search of donations to help fund its agro-ecotourism initiative.

Sustainable Harvest International (SHI) based in Panama, aims to preserve the environment by partnering with families to improve their wellbeing through regenerative farming. SHI has two decades of experience training farmers how to transition into regenerative agriculture. The project is currently seeking sponsorship and donations to hire more staff to connect with farmers waiting to join the regenerative agriculture transition program. The goal is to expand these practices so they have a global effect.

Get involved and qualify for a micro-grant

Registering at RHub.com will allow you to join a growing global community and connect with others focused on regeneration. The platform allows you to interact with ongoing projects, even if you don’t yet have one of your own.

Registering a project with a complete profile on RHub.com will also allow you to apply for one of the five US$1,000 grants, which will be funded by RI. Grantees will be connected with experts to help support their projects, as well as will be featured on RegenerationInternational.org. The group’s steering committee will evaluate the projects and announce the winners in April 2017. Click here for more info.

Become an RHub partner or pollinator

Becoming an RHub partner offers a great opportunity to support and be part of an international network of regenerative solutions. Whether you have a network that’s seeking to expand and connect with projects worldwide or are interested in helping spread the message, RHub partnership has many benefits. We even display your logo on the official partner’s page. Send us your high-resolution logo to info@regenerationhub.com.

Interested in taking more of a leadership role in spreading regenerative solutions in your locale? We’re seeking global regenerators to help build our platform. To learn more about becoming a community pollinator, email us at info@regenerationhub.com.

A Conversation With Food Tank’s Danielle Nierenberg

A Conversation With Food Tank’s Danielle Nierenberg

By Brian Barth on March 28, 2017

anielle Nierenberg’s experience with agriculture goes all the way back to her roots in the rural Midwest. Though she admits that back then, “I didn’t want to have anything to do with farming.” To say that she has now changed her tune would be an understatement.

The feisty founder of Food Tank—as the name implies, it’s a think tank for the food system—always seems to be in three places at once, whether holding court in a farmer’s field, penning op-eds for major newspapers, or onstage, microphone in hand, smiling at a group of esteemed panelists assembled to discuss some obscure but important topic like the agroforestry systems of Afghanistan, while grilling them about their assumptions and the scientific validity of their work. (Full disclosure: Nierenberg is on the Modern Farmer Advisory Board, too.)

Food Tank is most widely know for its “food summits,” which occur sporadically throughout the year in different cities around the globe (the next one is April 1-2 in Boston). You could describe the summits as sort of a food-centric version of Ted Talks, but Nierenberg makes it clear that these aren’t just feel good preaching-to-the-crowd conventions. They’re about bringing food system players together who might not normally talk to each other—who might hate each other guts—and drawing them into a meaningful public debate on the most pressing issues of the day. No Power Points slideshows here, she says: “We don’t want to allow people to just give their usual spiel that they would give at any sort of industry event or sustainable agriculture conference. Sometimes it’s important to have an uncomfortable conversation, and allow for unusual collaborations to develop.”

I don’t like to romanticize farming; but we’re hoping to make sure that young farmers know that they are not alone,

This month, the Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture released Letters to a Young Farmer, a collection of essays by 36 leading thinkers in the food world which addresses a certain white elephant: the average age of American farmers is 58.3. Thus there are now more farmers over the age of 75 than between the ages of 35 and 44, which says something about the appeal of the profession in contemporary society. Nierenberg, who contributed an essay to the anthology (along with the likes of Barbara Kingsolver and Michael Pollan), recently sat down with Modern Farmer to share her thoughts on this, and other, essential subjects facing the future of our food system.

Modern Farmer: What was on your mind when you sat down to write your essay for Letters to a Young Farmer?

Danielle Nierenberg: My letter talks about being someone who grew up in a rural Midwest environment and didn’t want to have anything to do with farmers. I thought what they were doing was stupid and I didn’t get it. But in my own personal evolution I’ve learned so much from farmers, as a Peace Corps volunteer when I was younger and later in my career with Food Tank and other organizations. I’ve been able to spend time on farms both in the United States and around the world and get a sense of the important work that farmers are doing every day.

I don’t like to romanticize farming; but what the book is hoping to do is make sure that young farmers know that they are not alone, that there is a growing movement that wants to support them. I thought about what would I want to hear if I was a 22-year-old fresh out of college and embarking on a life as a new farmer. We’re seeing so many people giving up lucrative jobs and turning to farming because they think it’s important.

We’ve forgotten that farming is super knowledge-intensive, or at least it should be.

MF: Do you think the agriculture world is making progress in attracting new farmers?

DN: We are certainly seeing a surge in organic operations, but you don’t see a lot of the folks that I grew up with in the nineties in the Midwest who stayed on the farm. Most didn’t want to. So I think we have a long way to go, especially now with the Trump administration. We made some headway over the last eight years with USDA programs to encourage young farmers, including mentoring programs that link younger farmers with older experienced ones. I fear that a lot of that will disappear and young farmers won’t get the resources and support that they need.

MF: Riding a tractor all day by yourself through a field of corn and soybeans isn’t an appealing job description for a lot of people. Is part of the problem that farming is not sexy enough as an occupation to draw the millennial crowd?

DN: I don’t want to demonize the folks who are operating those large commodity farms, because they have a lot of valuable knowledge and skills. Despite the stereotypes a lot of those folks are actually using very advanced technology to grow crops more efficiently and I don’t want to undermine that in any way. I encourage the integration of high tech with traditional techniques—combining GPS and drones and crop data on your cell phone and all this other cool stuff that’s happening in modern agriculture with cover crops and green manure and native species. I think there is a real opportunity for farmers of all sizes to make farming intellectually stimulating and exciting. We’ve forgotten that farming is super knowledge-intensive, or at least it should be.

MF: Sounds like agriculture has a branding problem.

DN: For folks out there who are looking for something that surprises them every day and invigorates them in a way that working on Wall Street or at a tech company doesn’t, I think they can find that in farming. We have this illusion that farmers are farmers because they are dumb, that they ended up on the farm because they didn’t go to college and don’t have any other opportunities. I think that perception is really changing, but it’s a slow road.

It’s an especially slow road in developing countries where often the government is telling you to get out of farming and move to the city, that they’re not going to support farmers. There is a lot of work to be done to change those perceptions and encourage investment in agriculture so that it’s attractive for young farmers all over the world. But I’m encouraged by what we have seen over just the last five years with Silicon Valley being more interested in investing in sustainable food systems—that will be hard for the new administration to ignore.

If you’re interested in what makes good business sense, what makes money, you can’t deny that having more organic, planet friendly, and plant-based products is a good idea. Those things have been successful because the demand is there. I don’t think it’s going to work to ignore that now and focus on what is essentially a 1980s philosophy for the food system. But unfortunately I don’t think this administration realizes that.

MF: Now that you’ve brought it up, what else worries you about Trump in regards to food and farming?

DN: I’m very apprehensive about what’s going to happen with the next farm bill. I think we are going to have to fight hard to maintain what we gained over the last eight years rather than trying for a lot of new things. The connection between immigration and farm labor is another thing where I think the new administration is totally behind the times. They don’t understand that without those folks, whether they are documented or undocumented, our food system would come to a grinding halt. The people who are growing, harvesting, preparing, and serving our food need to be better recognized for what they do. (Editor’s note: For more on immigration and farming, see “The High Cost of Cheap Labor” from our Spring 2017 issue.)

MF: Food Tank summits have been a fantastic forum for bringing all the stakeholders in the food system to the table, including farmworkers. Why is that important to you?

DN: Our mission is to highlight stories of hope and success in food and agriculture, both domestically and globally, and provide that inspiration to others who need it. I started Food Tank to give a different side to the story of food that was based on the work that I’d done interviewing hundreds and hundreds of farmers and other food system stakeholders around the world. I worked for an environmental organization for many years and it was very doom and gloom, always focusing on the problem. At Food Tank we also highlight where we think the system is broken, but what we really want to do, through the articles that we post every day online, through our newsletter and webinars and podcasts and research reports, is to give people examples of what is working.

Sometimes the things that are working are not getting a lot of government support or funding, so imagine what the world would look like if all those things got the support they needed to be really successful? We want to get those stories out there to a wider audience and show people what needs to be scaled up.

Without immigrants, whether they are documented or undocumented, our food system would come to a grinding halt. The people who are growing, harvesting, preparing, and serving our food need to be better recognized for what they do.

MF: You’re a bit notorious, if I may say so, for bringing people together who have strongly opposing views.

DN: We want to bring people together for the sake of good conversation, but sometimes it’s important to have an uncomfortable conversation, and allow for unusual collaborations to develop. We don’t want to allow people to just give their usual spiel that they would give at any sort of industry event or sustainable agriculture conference. We’ve brought together food labor and justice leaders on the same stage as scientists from Monsanto and Bayer and essentially forced them to talk to one another. It’s healthy to have to answer hard questions and sit next to people on stage or at lunch or in the audience who you never wanted to talk to.

I’ve been doing this for a while now and I’ve seen that preaching to the choir hasn’t gotten us anywhere. If we’re only talking to people whose viewpoints are similar to our own, we are never going to change things. That doesn’t mean I agree with Monsanto, and it doesn’t mean I agree every sustainable food advocate out there, but I do think we need to find where we can agree on things, acknowledge where we can’t, and then find ways to move forward.

We have a president who is not listening to anyone else and that’s not getting us anywhere, it’s just creating a lot of bitterness and anxiety. It’s the same in the food movement—if we want anything to change, we need to start listening to one another.

When we are talking about climate change, every story should include agriculture.

MF: In many ways Food Tank acts as a media organization, blanketing the airwaves with all these new ideas about food. What you think of mainstream media organizations and how they portray the food system?

DN: I feel they are still so behind the times. That’s not to say that The New York Times hasn’t done some amazing reporting over the years on different aspects of the food system—you can’t ignore a publication where both Michael Pollan and Mark Bittman have contributed so much amazing writing. But when we are talking about climate change, for example, every story should include agriculture. Every story about urban conflict should include agriculture. I still think there’s a tendency to not understand that the food system is not only involved in many of these issues, but it can also contain solutions, whether it’s to help alleviate a conflict, find ways to quell migration, or to better engage youth at school.

So I tend to be very disappointed with mainstream media. Anything about agriculture is usually buried below the fold of the front page or inside the newspaper because it’s something that not everyone is interested in—but they should be. Why the famine in sub-Saharan Africa is not on the front page every day, or the role of agriculture in climate change, not to mention its ability to help mitigate and reverse the effects of climate change, I do not know.

MF: You seem to keep at least one foot, and sometimes two, in the international realm of agriculture. What’s the message that you want US consumers to hear about agriculture in the developing world?

DN: Great question. It’s not just what I want consumers to know, it’s what I want other farmers to know. I feel like there has been a tendency for farmers in wealthier countries to think they have so much to teach farmers in other parts of the world, and that the transfer of knowledge and technology would naturally always come from the United States. In some cases that’s true; I think farmers here have a lot to share and that north-south collaboration is important. But what I am really invigorated by, and what I’ve actually seen a lot of, is that we have a lot to learn from farmers in the Global South. So I would love to see more of that south to north sharing of information.

We shouldn’t be ignoring farmers in the rest of the world just because they might be “less developed than we are.”

MF: What might that look like?

DN: Many farmers in developing nations have been dealing with certain things for a long time that are kind of new to American farmers, especially in terms of climate change. Like the wildfires that devastated livestock farmers in the Midwest over the last few weeks and the drought in California. Things like that are an everyday thing for many farmers in poor countries. Those farmers have learned to pivot and change their production practices quickly, though I grant that these farms are often a lot smaller than those in the United States.

There is also a lot to share around things like agroforestry, growing more indigenous and locally-adapted crops, and working with traditional livestock breeds. These are all things that could serve as important lessons for farmers in the United States and in other rich countries. We shouldn’t be ignoring farmers in the rest of the world just because they might be, quote-unquote, less developed than we are.

MF: In a similar vein, what do you think a conventional commodity crop farmer from the Midwest might have to teach a young aspiring organic farmer?

DN: I think many of these older farmers really understand the business of farming in a way that many upstart farmers do not. It’s easy to forget that farmers are businessmen, and businesses need business plans. Idealistic young people in every profession go in not knowing exactly what they’re doing financially. When I started Food Tank I didn’t have a clue about fundraising. Fortunately I had great help from my board to help me figure that out. Those are skills that we all need to learn, and hopefully we find great mentors along the way. But we also need a government that supports farmers in learning those essential skills.

Danielle Nierenberg speaking on a panel/photo by Stephan Röhl on Flickr

Why Yardfarm?

Why Yardfarm?

America’s future depends on cultivating the next generation to be yardfarmers.

The global climate is changing fast. This will require a radical shift in America’s economy, either proactively to limit carbon emissions, or in response to disruptions in global trade, and in food and energy supplies caused by runaway climate change. In turn, the consumer economy that provides the majority of the country’s jobs will inevitably contract.

Young people are often the first pushed out of a shrinking economy (as can be seen in Spain and Greece, both with youth unemployment rates of over 50 percent). Even today in the U.S.—in a relatively strong economic position globally—unemployment for 20-29 year olds with a college degree is at 11 percent, with many more ‘underemployed.’ Economists from the University of British Columbia and York University found that “Having a B.A. is less about obtaining access to high-paying managerial and technology jobs and more about beating less-educated workers for the barista or clerical job.” About 60 percent of 20-29 year olds still rely on parents for money, and 20 percent have moved back in with them—typically a source of great shame in the individualist American culture.

Meanwhile, the fifth largest crop in America is the turf-grass lawn with 40 million acres under cultivation, just after corn, soy, hay and wheat. These lawns are significant emitters of carbon dioxide (thanks to lawn mowing), major users of water (including in drought-prone areas), and considerable polluters as they absorb three million tons of chemical fertilizers and 30,000 tons of pesticides each year.

But imagine turning this upside down. What if adult children could proudly move back in with their parents—filling underutilized housing stock, reviving multigenerational living, and converting the ecologically problematic lawns around the neighborhood into a major source of sustainable food, household security and community resilience?

While yardfarming isn’t easy, it can be highly productive. Just a quarter acre of yard can produce more than 2,000 pounds of fruits and vegetables and provide a six-fold return on every dollar invested. The Victory Garden movement during World War II reveals the potential of this type of small-scale farming mobilization, with 18-20 million Victory Gardens producing 40 percent of household vegetable needs by the war’s end.

Imagine if suburban, exurban and even small urban plots around the country were converted to yardfarms. This land could create new livelihoods, food security, community resilience, and more biodiverse lands that would absorb water runoff, attract local wildlife, and sequester carbon (in the form of richer soils). Moreover it would reduce demand for lawn chemicals, and over time reduce demand for industrial food and farming—in turn making it possible for those lands to be rewilded.

And perhaps best of all, it would start rebuilding the norm around multigenerational living. In 2013, average home size in the U.S. hit a new record of 2,598 square feet, with an average of just 2.54 people living in the average American household. Having young people move back in to family homes would rebuild family ties and increase family interdependence, shrink household living costs, and reduce housing impacts on the environment and demand for new housing, all of which is a far more resilient, more sustainable way to design households and communities in the disrupted future that’s on our doorstep.

Growing Greens In The Grid: The Future of Urban Agriculture

Growing Greens In The Grid: The Future of Urban Agriculture

Feil Hall Brooklyn Law School

205 State Street Brooklyn NY 11210, Brooklyn, New York 11201

Thursday, April 6

6:30 to 8:30 p.m.: Networking Reception with Panel Discussion to Follow

Before the reception and panel, you are invited to attend the Fourth Annual CUBE Innovators Competition from 4:30 to 6:30 p.m.

About the Panel Discussion

The Center for Urban Business Entrepreneurship (CUBE) will host a panel and networking event to discuss the growth of the urban agriculture industry in the Brooklyn and greater New York City communities. Joined by the Office of the Brooklyn Borough President and members of the New York City Council, the panel will feature industry leaders and policy experts who will explore the technology and market forces driving innovation in urban agriculture, and chart a legislative path forward to expand existing policy, foster the creation of food growth opportunities in local communities, and nurture thriving new businesses.

Discussion topics will include the role played by attorneys in providing guidance to stakeholders in this pioneering market and the ways in which city officials and policymakers are addressing the economic and nutritional needs of local communities. The discussion will be bookended by CUBE Fellow Tatiana Pawlowski's ’17 presentation of her white paper “From Food Desserts to Just Deserts: Expanding Urban Agriculture In New York City Through Sustainable Policy.” Please join this conversation about the future of how urbanites will grow and source their food.

Moderated by John Rudikoff, CEO and Managing Director, CUBE

Sponsored by CUBE, Office of the Brooklyn Borough President Eric L. Adams and Rafael L. Espinal Jr., Council Member for the 37th District

Location

Brooklyn Law School

Feil Hall, Forchelli Conference Center, 22nd Floor

205 State Street

Brooklyn, NY

brooklaw.edu/directions

CUBE Innovators Competition

Watch Brooklyn Law School’s own version of “Shark Tank,” in which five teams of students present to a distinguished panel of judges their proposals for entrepreneurial approaches to address social and business issues or legal problems and legal practice. Learn more.

RSVP online before Monday, April 3

Urban Agriculture Shifts Tactics Under Trump

Advocates for urban agriculture are nervous these days. President Donald Trump has said little about his agriculture policy plans, his Agriculture Secretary nominee Sonny Perdue is a longtime ally to traditional rural agribusiness interests, and Trump’s proposed budget slashes funding for many of the agencies upon which urban residents depend.

Urban Agriculture Shifts Tactics Under Trump

D.C. organizations who depend on urban agriculture to feed the food insecure will be impacted.

MAR 28, 2017 9 AM

Advocates for urban agriculture are nervous these days. President Donald Trump has said little about his agriculture policy plans, his Agriculture Secretary nominee Sonny Perdue is a longtime ally to traditional rural agribusiness interests, and Trump’s proposed budget slashes funding for many of the agencies upon which urban residents depend.

At a recent daylong summit on “The Future of Food Policy” hosted by Washington D.C.-based Food Tank, urban agriculture advocates expressed dismay over the current political climate, describing it as both chaotic and frightening. In the midst of this chaos, negotiations for the 2018 Farm Bill are already underway and supporters of urban agriculture are scrambling.

Kathleen Merrigan is a former U.S. Department of Agriculture Deputy Secretary and longtime advocate for both organic and urban farming. Many observers say she’d be the Agriculture Secretary right now had Hillary Clinton won the election. Less than 100 days into Trump’s presidency, she sounds worried.

Executive Director of Sustainability at George Washington University, Merrigan, told the food policy summit audience she’d heard “the forces of darkness want to eliminate organic” from the Farm Bill entirely. Both organic and urban agriculture programs may be at risk for federal funding cuts, but Merrigan stands ready to defend the space urban agriculture has carved out for itself.

“Urban agriculture can’t feed the world—heck, it may not even be able to feed the block,” she quipped, but Merrigan insists the movement has more than earned its seat at the policy table. Urban farms matter, according to Merrigan, because they offer city dwellers a way to find a connection to the land and even their rural-dwelling, fellow Americans.

Historically, the Farm Bill has always brought together unlikely allies, so Merrigan is urging urban agriculture advocates to work with traditional rural agriculture groups. Considering the many cuts to rural programs that Trump is proposing, Merrigan’s suggestion makes a lot of sense. She made that plea while sharing the stage with Kip Tom, a rural farmer from Indiana and a Trump supporter, signaling, perhaps, that negotiations can happen anywhere.

While Merrigan opined about federal funding, Chris Bradshaw, Executive Director of the D.C.-based non-profit Dreaming Out Loud, honed in on urban agriculture programs in the District. Bradshaw also sits on the D.C. Food Policy Council. For Bradshaw, D.C.’s city farms grow food, yes, but they’re also a conduit for social justice, or at least that’s what Bradshaw feels they should be.

Bradshaw was one of the few to explicitly mention racial justice at the Food Tank summit and, as quoted in a recent piece over at Civil Eats about urban farms and gentrification, Bradshaw says that for urban farms to truly feed food insecure residents, and not just those who already have a wide array of fresh and local produce options, urban farmers have to take the time to build relationships within the communities they want to serve.

Dreaming Out Loud’s urban agriculture project Kelly Farms will cover an ambitious two acres in Ward 7, and that requires funding. Right now, the U.S. Department of Agriculture provides support for urban farming projects like Kelly Farms in a variety of ways, including grants, loans, and training programs, so if Congress were to follow Trump’s recommendations and cut many of these programs, how would that impact D.C.?

If federal grants and other funding support were cut, urban agriculture advocates may become increasingly reliant on city funding. Speaking later that day at the Food Tank summit, Councilwoman Mary Cheh explained that when past presidential administrations cut federal funding, city governments were the ones to step in and fill the gaps.

For now, Trump’s budget proposal is just a proposal, of course, but if these cuts are eventually enacted by Congress, Cheh says D.C. is indeed ready to make up the difference. Councilperson Cheh was the legislative driving force behind funding for school vegetable gardens, tax incentives for urban farms, and the D.C. Food Policy Council, so her track record for funding urban agriculture programs is well-established.

Of course, D.C.’s financial and political independence feel just a bit precarious these days, thanks to Trump and some recent maneuvering by politicians like Congressman Jason Chaffetz, but many of D.C.’s urban agriculture supporters say all they can do is use the funding they have today and make sure their local political support is lined up for tomorrow.

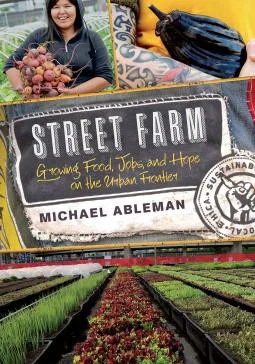

Michael Abelman: Urban Agriculture

Michael Abelman: Urban Agriculture

By PeakProsperity on March 27, 2017 3:43 pm in Politics, Videos

Food security is a foundational cornerstone of resilience, which is why here at Peak Prosperity we recommend sourcing a substantial percentage of your food calories locally. Buy from nearby sustainable farms and, if at all possible, grow some of your own food yourself.

Broin / Pixabay

Urban Agriculture

While many of our readers are now doing exactly this, we commonly hear how difficult it can be to follow these steps for those living in the suburbs or large cities.

Today, we welcome Michael Abelman to the program to share a successful urban agriculture model he’s helped to pioneer. Michael is the founder of the non-profit Center For Urban Agriculture, and has recently authored the book Street Farm: Growing Food, Jobs, and Hope on the Urban Frontier — which focuses on his efforts to transform acres of vacant and contaminated land in one of North America’s worst urban slums and grow artisan-quality fruits and vegetables.

In today’s discussion, Michael Abelman walks us through how farming in our cities is indeed possible. In fact, it not only results in healthier foods, but in healthier communities, too:

Our Sole Food Street Farm started when I received a phone call, eight or nine years ago, asking me to attend a meeting in Vancouver on the downtown eastside. The downtown eastside is a distressed neighborhood where the term “Skid Row” was coined. The invitation was to meet with several social service agencies in the neighborhood to discuss some interesting strategies for helping people in that community — the entire neighborhood is almost entirely inhabited by folks who are dealing with some form of long-term addiction, mental illness, and certainly, high levels of material poverty.

The group of people meeting had access to a half acre parking lot next to one of the dive hotels, and we decided there was a desire to do something agricultural. We decided that the most important thing that we could achieve was to try to create a model that developed meaningful work employment; a reason for people to get out of bed each day. And so, we developed that first half acre as a model — we created a technical system that allowed us to safely grow on either pavement or contaminated land using innovative boxes we designed that isolate the growing medium.

And we eventually expanded to over almost five acres of land on four different sites — including a production orchard, 16,000 square feet of high tunnel unheated greenhouses, and large open parking lots — to the point where we’re now producing 25 tons of food annually and employing close to 30 people.

And we now have people employed with us who before had never held a job for longer five or six months, but they’ve been with us now for almost eight years in supervisor positions, having in many ways cleaned up their act, learned new skills, and found some sense of purpose.

Click the play button below to listen to Adam’ interview with Michael Abelman (58m:23s).

Three Ways To Urban Agricultures: Digging Into Three Very Different Offerings From Three New Books

Three Ways To Urban Agricultures: Digging Into Three Very Different Offerings From Three New Books

By Wayne Roberts

When Socrates, Plato and the gang had their dialogues about the inner essence of beauty, truth and justice, while hanging out at the farmers market in downtown ancient Athens, they had no idea of the problems they would create for urban agriculture 2500 years later.

Unfortunately, urban agriculture is still all Greek to many city planners.

That might seem like a stretch, but give me a chance to make my point. The ancient Greeks established the pattern of looking for absolute and universal Truth in the singular. The simplest way to see the legacy of this tradition in today’s thinking about food is to look at all the single-minded words. Think of such commonly used expressions as food policy, food strategy, food culture, local food, sustainable food, alternative food, and urban agriculture. Not much pluralism, plurals or variation here!!

We betray the Greek origin of western styles of thinking every time we use the singular to discuss potential options with regard to the abundance of foods and food choices that urban lives and modern technologies provide (please note my use of the plural).

So, for example, we have city discussions about the need for a city policy on urban agriculture, instead of city discussions about the need for city policies to support various forms of urban agricultures.

The ancient Greek philosophers, despite many wonderful ideas they developed, were hung up with locating the one and only essence of things — an abstraction that was independent of the ups and downs of momentary appearance.

They didn’t like messy realities because they were too messy, and left that world to slaves and women. That tradition is still alive and unwell, as the low wages and standing of agricultural and food preparation work shows. The jobs that pay well are jobs removed from messy realities.

Likewise, to this day, a narrow and absolutist mindset straitjackets our thinking about food policy in cities.

Alfonso Morales edits new book on many forms of city farms

To wit, the way cities agonize over a policy (note the singular) for urban agriculture (note the singular), rather than a suite of policies (note the plural) to help as many who are interested, for whatever reasons (note the plural), be they love or money, to eat foods (note the plural) they have grown or raised or foraged in varieties (note the plural) of spaces (note the plural) — from front yards, to back yards, to green roofs, to green walls, to balconies, to windowsills, to allotment gardens, to community gardens, to beehives, to butterfly gardens, to teaching and therapeutic gardens, to edible landscaping, to soil-based, hydroponic and aquaponic greenhouses, to vacant lots, to public orchards, to community composting centers, to grey water recycling for lawns and gardens, to formally-sited farms and meadows.

LET ME COUNT THE WAYS

There are so many opportunities, so many points on the urban agricultures spectrum, that we can’t even say “urban agriculture is what it is.”

That fact is that “urban agricultures are what they are,” and city governments in different areas should embrace many of them.

Of course, public authorities need to practice their usual due diligence in terms of personal and public safety, but the emphasis of policy should not be on toleration or permission, but management and stewardship of the health, environmental, community and economic yields of urban ag.

Janine de la Salle’s wake-up call

This is in marked contrast to the present mode of civic management over urban agriculture. City food planning advocate Janine de la Salle, who has the fortune to work in Vancouver, which is an exception to the rule, describes the norm as one where officials need a wake-up call because they’re managing urban agriculture in the same passive way they manage sleep, another essential of life. Like sleep, urban food production is treated as “necessary, but not meant to be regulated or managed in any meaningful way,” she writes in her chapter in the book Cities of Farmers.

That nice little dig (there are many ways to dig in support of urban agricultures) brings me to the business at hand in this newsletter, a review of three fairly new resources (two books, one assortment of essays) on urban agriculture — each of which sheds a distinctive light on the growing possibilities of urban food production.

VIEWS FROM MADISON

The best to begin with is the collection edited by Julie Dawson and Alfonso Morales, called Cities of Farmers: Urban Agricultural Practices and Processes. It sets the stage.

Horticulture expert Julie Dawson co-edited Cities of Farmers

The two editors come from the state university in Madison, Wisconsin, where the late city planning authority, Jerry Kaufman, spread his protective wings around a new generation of urbanists who now teach and practice city food planning around the world. Before Kaufman, the conventional wisdom of city planners was that food was produced in rural areas and consumed in cities; cities should stick with making things that provided the “highest use” of expensive city land. This anthology, which breaks totally from convention, is a worthy basket from the harvest Kaufman seeded. (To be transparent, I am as indebted to encouragement from Kaufman as any of his students.)

Jerry Kaufman, godfather of city food planning

To be more transparent, I got to see this book before it was published, so I could write a back cover blurb drawing attention to its “down to earth quality” that can help city planners, health promoters, community developers and “all who love what a garden does for a day outdoors, a yard or parkette, a great meal, and quality time with others.”

The breakthrough of the book, in my view, is that it doesn’t ask the ancient and unanswerable philosophical question about “what is urban agriculture.” Instead, it asks the more pointed and fruitful question: what do urban agriculture projects do.

The book’s answers (note the plural) form the most comprehensive overview yet of how the “multi-functionality” of both agriculture and food can generate the many benefits that urban agricultures bestow on cities.

Producing food may well be the least accomplishment of urban agriculture, though that extra food can really make a difference for people on low income. But the crop itself is only one contribution on a long list that includes enhanced public safety, community vitality and cohesion, neighborhood place-making, skill development, food literacy, garbage reduction (through composting) and green infrastructure.

down to earth look at urban ag

As Erin Silva and Anne Pfeiffer argue in their chapter on agroecology in cities, the sheer range of benefits bestowed by urban agricultures dwarfs the efficiency of any one particular contribution — be it food production or the development of community food literacy. This knocks the economic analysts for a loop because the premise of this book is that the whole is greater than the part, and the efficiency comes out of the whole, not any one part. “Though food production remains a central focus for many operations,” they write, “ it is often a means to achieve other social benefits rather than the singular goal.”

As I used to put it during my working days at the city of Toronto, the success of all forms of food activities, including urban agricultures, rest on the economies of scope, not the economies of scale.

Therein lies the key to measuring true productivity, and when we understand why that breakthrough method of measuring progress in food matters, we will come to see the potential of totally different methods of managing and incentivizing food activities.

HOW DO YOU GET TO GARDEN AT CARNEGIE HALL? PRACTICE!!

Though I like all the essays in the book, the one that knocks my socks off is by Nevin Cohen and Katinka Wijsman. It highlights the central role of food practices in a way that points to new ways of promoting food activities that go far beyond the boundaries of urban agricultures. (Are you becoming more comfortable with all the plurals?)

Nevin Cohen, co-author, practices looking like a gardener

This essay is fundamental to anybody who want to make the journey from food policy to implementation of new food practices.

I never had a policy of brushing or flossing my teeth after a meal. But sometime before I remember, I learned the practice of brushing my teeth — though I learned the wrong practice that was standard in my day, of scrubbing up and down and side to side, not gently brushing up or down from the gums to prevent gum damage. Unfortunately, I didn’t get the practice right in time to save my gums from painful and expensive dental work, which also instilled in me the practice of flossing. At this point, flossing is no longer a policy decision I make, but a practice I follow “automatically.” That norm of “practice”is one followed by people who practice anything from medicine to yoga, and we now need to normalize it in good food practices. As medicine, yoga, Cohen and Wijsman make clear, policy is the servant of practice, not the other way around.

Their essay reviews how New Yorkers went from policy advocacy to practices that implemented community gardens. They not only normalized community gardens on the most expensive real estate in the world, they incorporated forms of urban agricultures into the basic infrastructures of a city — from green roofs and walls to green paths and street greenings that manage stormwater.

The gardening version of pilgrims’ progress in New York City has been as much about advancing practices as policies, Cohen and Widjsman argue.

Indeed, practices need to become the a lens for all people who seek meaningful food system changes in food. Part of the thinking behind a city establishing a food policy council or urban agriculture sub-committee is to provide an institutional focus for the new civic practice of automatically saying “we can do our due diligence on food practices by referring this issue on (whatever) to the food policy council and urban ag committee, and asking if we overlooked any possible food enhancements.”

We have come full circle from Plato and the ancient Greeks, who saw theory as the exemplar of purity, not defiled by the shadows in the caves that people lived in. This is why we now need to refer to people who get the new paradigm of meaningful change as “communities of practice.”

Developing such communities is the way we build vehicles for food system transformation, just as people who practice yoga or medicine or meditation work their changes.

When you have finished this book, you will be mentally ready for the latest practices from one of the master practitioners of organic food production.

ABLEMAN’S ABILITY

Michael Ableman is one of the preeminent growers, photographers, speakers, writers and entrepreneurs produced by the global organic movement. He was able to bring all these mature skills and practices to the most delicate, fragile and responsible project of a lifetime — cultivating the skills and practices of 25 employees from Vancouver’s notoriously drug-ridden Downtown East End to the point where they tended five acres on four beautiful and productive food gardens. Urban agricultures don’t get much grittier than this. Ableman’s book, Street Farm: Growing Food, Jobs, and Hope on the Urban Frontier, tells the story.

Street Farm goes beyond-down-to-earth; it’s down to pavement

There was no utopian vision — it takes a practiced hand to know to steer clear of that — but Ableman and his crew “wanted the world to know that people from this neighborhood, those who were viewed as low-life losers, could create something beautiful and productive; that they could eat from it, feed others, and get a paycheck from its abundance; and that it could sustain itself for more than a few days or weeks or months or years.”

If urban agricultures can accomplish something akin to that, city gardens can produce something every bit as essential as food. This is what people-centered food policy is about.

Devoted organic grower and foodie that he is, Ableman digs the people-centeredness of this urban agriculture project. Employing and enabling the neighborhood farm workers is the mission of the street farm, he writes, citing the Japanese farm philosopher Masanobu Fukuoka who insisted the “ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation of human beings.” He came to regard his fellow workers as “farmily.”That does put urban agricultures in context, and explains why land-use policy for urban agriculture deserves to be classified as among the “highest uses” of urban land.

Ableman also understands that urban agriculture is not just rural agriculture in a city. It sometimes has to be adapted in stark ways. He came to understand, for example, that a paved parking lot was an ideal foundation on which to build, and that the best way to grow was in some 5000 wood and plastic bins (almost 10,000 at the time of this writing), which can be moved when a lease or a welcome run out.

Does Abelam see urban ag as another way to bring art to the people?

He also understands the centrality of partnerships and of champions on city staff to his success; they are the city farmer’s environment, as important and immediate as nature is to the rural farmer. At one point, he even argues that the crisis of global industrial agriculture is, above all, “a crisis of participation” — which distances people from their food as much as the 5000 mile trip that Asian rice takes to a plate on the eastern seaboard of the Americas.

WHAT HUMANS HAVE IN COMMONS

Ableman’s understanding of the centrality of engaging the human side of food production (should we call it human-centered food policy?) is the segway to the third body of work considered in this newsletter on urban agricultures — the work of Chiara Tornaghi at Coventry University in England.

As I read her articles, Tornaghi is so bold as to put our psychic needs of our deeply-rooted human spirit on par with deeply human physical needs for food — and thereby to classify citizen access to urban food production as essential. Only such a deep understanding of the need to engage with and participate in food production could account for her proposal that access to food production opportunities be classified as part of a citizen’s inborn and inherent “right to the city.”

Gardening activist Chiara Tornaghi and her assistant

Tornaghi’s work is accessible in a variety of places — including one article on how to set up an urban ag project, and one pieceon the critical geography of urban ag, and one study on urban ag and the politics of empowerment, and one reporton gardening activism, as well as a publication on European urban agriculture.

She’s pretty much out there, with phrases such as “insurgent urbanism” and “politics of engagement, capability and empowerment,” along with references to the commons, metabolism and other clues that Tornaghi has spent as much time in obscure sections of libraries, as in gardens.

At the very least, she is refreshing. People concerned about the runaway rates of mental ill-health among young people cannot ignore what she has to say about addressing human needs to work directly in nature — and thereby counterbalance the highly built, urbanized, synthetic, abstracted, impersonal, mediated and corporate-controlled environment of dense cities.

In my view, this mental health and well-being perspective is the most urgent and compelling reason for city planners and managers to listen up on the subject of urban agricultures.

I don’t want to gild the lily of what she has to say. There are calls to action from earlier times that call for direct action, by which was meant “take power into your own hands, and come to a demonstration calling on someone else to do something.”