Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Engineer-Turned-Farmer Brings Vertical Farm Concept Back To Earth

Engineer-Turned-Farmer Brings Vertical Farm Concept Back To Earth

KATE TRACY MAY 2, 2017

Infinite Harvest founder Tommy Romano grows lettuce and other greens in his Lakewood vertical farm. (Kate Tracy)

The origin of Tony Romano’s startup sounds plucked from the pages of a sci-fi screenplay.

As an aerospace engineering master’s student at CU Boulder in 2002, Romano was working on a project for how to feed 200 humans on Mars for two years. The solution: hydroponics and vertical farming. The problem: a lack of humans on Mars.

“There is no one there yet,” Romano said. “Why aren’t we doing this down here?”

That’s when the plot veered from fantasy to reality.

The engineer-turned-farmer ran with his idea, writing his business plan for a vertical hydroponics farm in 2009. The next year, he launched his first operation out of a wind- and solar-powered shipping container in a field in Golden.

“That was the proof of concept that we used to raise our first capital raise in 2014,” Romano said. With those funds, Romano opened his first facility in Lakewood.

Now, Infinite Harvest has 18 employees and produces 100,000 heads of lettuce per month. And Romano raised $60,000, according to a March SEC filing.

“It’s all for getting this facility to increase its own production,” Romano said. “We’re not at 100 percent production yet.”

Romano, 45, uses peat as the medium and filtrated city water to grow his plants, which are stacked vertically and in columns on 10 tiers that are 16 feet high. In the 5,400-square-foot grow area, Romano can plant an acre’s worth of produce in one-tenth of the space, he said. Infinite Harvest controls the air and water temperature, light and other factors that create ideal growth environments.

Unlike aquaponics, Infinite Harvest does not use fish to fertilize plants, as it simplifies the system and lowers the risk of contamination, Romano said.

Even on Christmas Eve with 3 feet of snow outside, Infinite Harvest is planting.

“We grow every single month of the year,” Romano said. “It is farming on the manufacturing level.”

Romano plans to use the capital from his recent raise to buy more seeds, nutrients and greenhouse equipment to provide more leafy greens for Infinite Harvest’s main clients, Shamrock Foods and FreshPoint. Both distributors sell Romano’s produce to a variety of businesses in Denver, from casual joints like Tokyo Joe’s to fine-dining restaurants like Jax Fish House and Ocean Prime. Infinite Harvest also sells directly to a few local Denver businesses, including The Way Back, Serendipity Catering and Nooch Vegan Market.

Romano looks to hire two employees to keep up with the increase in production, and also is eyeing a bigger facility.

“We have a very solid confidence that we’ll be profitable this year,” Romano said.

Right now, Infinite Harvest grows three types of lettuce and 13 kinds of micro-greens, including baby arugula, baby kale and micro curly cress.

“We stay with leafy greens because they are very easy to grow,” Romano said, adding that they are a quick harvest and require the same nutrients and other environmental conditions. He hopes to expand to tomatoes and other produce that will require a different grow room.

Denver has other indoor growing operations. The GrowHaus, a nonprofit in the Elyria-Swansea neighborhood, also has a hydroponics farm, which sells produce to neighborhood residents and restaurants. Circle Fresh Institute in Wheat Ridge teaches classes to students interested in greenhouse farming.

But Romano says Infinite Harvest’s nearest competitor is Green Sense Farms in New Jersey. Japan, Belgium and Singapore also have vertical farms of similar scale.

North Carolina: The City of Asheville Has Launched The ‘Asheville Edibles Program’

North Carolina: The City of Asheville Has Launched The ‘Asheville Edibles Program’

Linked by Michael Levenston

The purpose of this program is to provide an opportunity for community members to grow food and pollinator plants on publicly-owned land – Adopt-A-Spot – Community Gardens – Urban Agriculture Leases

City of Asheville

Adopt-A-Spot

The City has teamed up with Asheville GreenWorks to provide oversight of the new Adopt-A-Spot program. Businesses, organizations, or individuals can apply to adopt a City-owned piece of property. Once an application is approved, the responsibility of the adopter will be to maintain either an edible or pollinator garden in the location. Adopters will be recognized with a sign at the adopted spot. This program aims to make a positive impact on Asheville by promoting stewardship of publicly owned places.

Community Gardens

Asheville’s Community Gardens Program provides residents with an opportunity to organize community gardens on designated City-owned land. For successful applicants, there is no cost to lease the land, and each garden location has room for several plots. This is a great way to bring a neighborhood and/or organization together to grow local, fresh, and healthy produce to create a stronger, more resilient community.

Urban Agriculture Leases

The Urban Agriculture Leases Program has parcels of City-owned land prepared to be leased at fair market value. The terms of the leases are 3 years with an option to renew. This program is designed to support urban agriculture development to increase local food production and community food security. The City encourages applications from qualified individuals, businesses, and/or nonprofit organizations to apply for a lease agreement. This is a great opportunity for those who want to grow food on a larger scale, but do not have the property to do so.

Vertical Farming in Amsterdam

Vertical Farming in Amsterdam

GROWx Labs Opens in April 2017

Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Friday 24 March 2017 – GROWx is the leading innovator in vertical farming in the Netherlands will open GROWx Labs in Amsterdam Zuid Oost.

It is amazing that so much food arrives into cities every day, but it is not without problems. Farmers are far away from their market, there are negative ecological effects caused by modern farming, and collectively farms are the single largest users of land in the economy. Faced with limited fresh water resources and limited land to farm, we have to pioneer new ways to farm.

Today, local for local farming producing clean food is the new organic. People desire to know where their food is coming from and if it is clean of undesired chemicals. Urban farms are rising in cities around the world on roof tops and community space. Vertical farming, pioneered in the USA and Japan, is a new way to grow food year round for daily fresh products.

Jens Ruijg, engineer, and John Apesos, entrepreneur, founded GROWx in April of 2016 to build Netherland´s first production vertical farm. The project is focused on serving Amsterdam´s Chef community fresh greens. The GROWx Labs facilities opens in April for Amsterdam´s Chefs to taste interesting varieties of fresh greens and salads.

The Netherlands is a leader in horticulture technology. The GROWx Amsterdam project capitalizes on local expertise, suppliers and university eco-system to build next generation greenhouse technology in the form of vertical farming. Amsterdam has an opportunity to lead the revolution for a fresher urban food future.

GROWx:

GROWx BV is on a mission to accelerate the advent of sustainable urban agriculture. GROWx BV works in co-designing, implementing and operating sustainable vertical farming solutions for city scale food production. We are innovating in indoor food production technology involving multiple layers, controlled plant climates and LEDs.

See more on https://www.instagram.com/grow_x/

Press Contact:

Name: John Apesos

Mobile: +31 06 38 313 515

Email: john@growx.co

Local Farm Grows Mushrooms Indoors

Local Farm Grows Mushrooms Indoors

Southern Tier Mushrooms sells to stores, restaurants

By RYAN MULLER - APRIL 30, 2017

Finding its own place in the growing Binghamton area food scene, Southern Tier Mushrooms is sprouting fresh, gourmet mushrooms to be sold and served in local stores and restaurants.

“The main goal of Southern Tier Mushrooms is to produce gourmet mushrooms locally to the Southern Tier region,” said Director of Operations Eddie Compagnone, ‘15. “When people are looking for a fresh-quality mushroom, they definitely would find us attractive.”

Located in a house on the South Side of the city of Binghamton called The Genome Collective, Southern Tier Mushrooms grows its crop in a basement-turned-mushroom farm. The Genome Collective house looks like an ordinary house at the surface, with a living room, kitchen and even a house dog — but in the basement is a laboratory setup with dozens of mushrooms stacked on shelves.

Compagnone, a member of The Genome Collective, described the house as a community with the common goal of food justice, and a commitment to the idea that communities should assert their right to eat fresh, healthy food. The owner of Southern Tier Mushrooms, Bill Sica, rented the basement of The Genome Collective for growing space, and Compagnone and fellow resident, Louis Vassar Semanchik, were drawn to the project.

“[Louis] and I started helping Bill as we were residing here, because we saw potential in his business,” Compagnone said.

The mushroom growing process begins on a microscopic level inside of a petri dish. The mushrooms start out in the early stages of a fungi as a mycelium and grow on sugars inside of the dish. After the mycelium has grown enough, oats commonly used as horse feed are added to provide nutrients to the mycelium and allow it to grow. The matured mycelium is then mixed in a bag with sawdust, to which the mycelium attaches itself, and begins to grow into mushrooms. The mushrooms grow in a closed-off room in the basement called the fruiting chamber. Outside of that room, there is an adjoining space that houses a machine called a pond fogger to create artificial humidity. This replicates the ideal natural conditions needed for the mushrooms to grow.

At their indoor farm, Southern Tier Mushrooms mainly grows oyster mushrooms, but it is also experimenting with other types, like lion’s mane and reishi. The gourmet mushrooms produced by the farm are popular not only for their taste, but also for their health benefits. Compagnone explained that oyster mushrooms can lower cholesterol and lion’s mane mushrooms can restore the myelin sheath in the brain, improving memory.

The farm is currently selling its mushrooms to local businesses like health food store Old Barn Hollow and Citrea Restaurant and Bar, both in Downtown Binghamton. Southern Tier Mushrooms aims to produce fresh mushrooms for businesses in New York, and Compagnone said they are working with five more businesses on possible partnerships. In the future, Southern Tier Mushrooms plans to expand into a warehouse to grow on a larger scale and distribute to as many people as possible.

To Compagnone, sourcing local food allows distributors to provide benefits of health, taste and quality in ways that nationwide distributors cannot, primarily due to the time it takes to transport them and the preservatives needed. According to him, indoor farming is part of a growing trend, thanks to a renewed interest in do-it-yourself food production and concerns about unstable environmental conditions.

“This is what the future of farming looks like,” Compagnone said.

China Focus: Factory Farms The future For Chinese Scientists

China Focus: Factory Farms The future For Chinese Scientists

Source: Xinhua| 2017-04-30 09:06:29|Editor: Yamei

XIAMEN, Fujian Province, April 30 (Xinhua) -- In a factory in eastern China, farming is becoming like scientific endeavor, with leafy vegetables embedded neatly on stacked layers, and workers in laboratory suits tending the plants in cleanrooms.

The factory, with an area of 10,000 square meters, is in Quanzhou, Fujian Province. Built in June 2016, the land is designed to be a "plant factory," where all environmental factors, including light, humidity, temperature and gases, can be controlled to produce quality vegetables.

The method is pursued by Sananbio, a joint venture between the Institute of Botany under the Chinese Academy of Sciences (IBCAS) and Sanan Group, a Chinese optoelectronics giant. The company is attempting to produce more crops in less space while minimizing environmental damage.

Sananbio said it would invest 7 billion yuan (about 1.02 billion U.S. dollars) to bring the new breed of agriculture to reality.

NEW FARMING

Plant factories, also known as a vertical farms, are part of a new global industry.

China now has about 80 plant factories, and Sananbio has touted its Quanzhou facility as the world's largest plant factory.

In the factory, leafy greens grow in six stacked layers with two lines of blue and red LED lights hung above each layer. The plants are grown using hydroponics, a method that uses mineral nutrient solutions in a water solvent instead of soil.

"Unlike traditional farming, we can control the duration of lighting and the component of mineral solutions to bring a higher yield," said Pei Kequan, a researcher with IBCAS and director of R&D in Sanabio. "The new method yields ten-times more crops per square meter than traditional farming."

From seedling to harvesting, vegetables in the farm usually take 35 days, about 10 days shorter than greenhouse plants.

To achieve a higher yield, scientists have developed an algorithm which automates the color and duration of light best for plant growth, as well as different mineral solutions suitable for different growth stages.

The plant factory produces 1.5 tonnes of vegetables every day, most of which are sold to supermarkets and restaurants in Quanzhou and nearby cities.

The world's population will bloat to 9.7 billion by 2050, when 70 percent of people will reside in urban areas, according to the World Health Organization.

Pei said he believes the plant factory can be part of a solution for potential future food crises.

In the factory, he has even brought vertical farming into a deserted shipping container.

"Even if we had to move underground someday, the plant factory could help ensure a steady supply of vegetables," he said.

HEALTHIER FUTURE

Before entering the factory, Sananbio staff have to go through strict cleanroom procedures: putting on face masks, gloves, boots, and overalls, taking air showers, and putting personal belongings through an ultraviolet sterilizer.

The company aims to prevent any external hazards that could threaten the plants, which receive no fertilizers or pesticides.

By adjusting the mineral solution, scientists are able to produce vegetables rich or low in certain nutrients.

The factory has already been churning out low-potassium lettuces, which are good for people with kidney problems.

Adding to the 20 types of leafy greens already grown in the factory, the scientists are experimenting on growing herbs used in traditional Chinese medicine and other healthcare products.

Zheng Yanhai, a researcher at Sananbio, studies anoectohilus formosanus, a rare herb in eastern China with many health benefits.

"In the plant factory, we can produce the plants with almost the same nutrients as wild anoectohilus," Zheng said. "We tested different light, humidity, temperature, gases and mineral solutions to form a perfect recipe for the plant."

The factory will start with rare herbs first and then focus on other health care products, Zheng said.

GROWING PAINS

Currently, most of the products in the plant factory are short-stemmed leafy greens.

"Work is in progress to bring more varieties to the factory," said Li Dongfang, an IBCAS researcher and Sananbio employee.

Some are concerned about the energy consumed with LED lights and air-conditioning.

"Currently, it takes about 10 kwh of electricity to produce one kilogram of vegetables," said Pei, who added that the number is expected to drop in three to five years, with higher LED luminous efficiency.

In a Yonghui superstore in neighboring Xiamen city, the vegetables from the plant factory have a specially designated area, and are sold at about a 30 percent premium, slightly higher than organic and locally produced food.

"Lettuce from the plant factory is a bit expensive, at least for now, there are many other healthy options," said Wang Yuefeng, a consumer browsing through the products, which are next to the counter for locally produced food.

Sananbio said it plans to expand the factory further to drive down the cost in the next six months. "The price will not be a problem in the future, with people's improving living standards," Li said

San'an Opto headquarters in Xiamen, China. (Photo courtesy of San'an Opto)

GrowNYC Throwing Open House For New Community Center Project Farmhouse

GrowNYC has an official home — and you’re invited inside.

GrowNYC Throwing Open House For New Community Center Project Farmhouse

By Meredith Deliso meredith.deliso@amny.com April 23, 2017

The organization, which runs greenmarkets and gardens throughout the city and hosts programs on environmental issues like recycling, will celebrate the opening of its new sustainability and education center with an open house on April 29.

Project Farmhouse opened its doors late last year, hosting private events and school programming. At the open house, visitors can get a sense of what kinds of public programming will be on offer down the line, with tours of the space and cooking demos by Peter Hoffman, Gaggenau’s Eric Morales and a chef from Brooklyn’s Olmsted, as well as composting demos, nutrition workshops, recycling games, take-home DIY planters and more.

“We really built this space to be a community center for people to come together around sustainability and healthy eating and all of the programs that GrowNYC is already involved in, in the community,” said Laura McDonald, events director at Project Farmhouse.

Much of GrowNYC’s existing programming focuses on teacher training and student education. The organization anticipates hosting 500 teachers and 2,000 children each academic year at Project Farmhouse. Hands-on programs for students include GrowNYC’s Healthy Food Healthy Bodies series, which features field trips to greenmarkets and discussions with chefs on nutrition and health, as well as programs on renewable energy and farming.

The state-of-the-art space is a lesson in sustainability itself, from a farm-inspired entry archway made using repurposed wood beams to sun tunnels to let in natural light and a kinetic hydroponic wall. A centerpiece is its induction kitchen, donated by kitchen design company Boffi Soho, for cooking demos.

McDonald looks to ramp up public events in the summer, with potential programming like lectures, movie nights and demos from cookbook authors. Having the Union Square Greenmarket just steps from Project Farmhouse is also an advantage.

“There are lots of tie-ins with the market,” McDonald said. “We’re trying to get the farmers in here, doing some demos or talking about what their lives are like. It’s awesome that it’s just a couple blocks away.”

IF YOU GO

Project Farmhouse will host an open house April 29 from 11 a.m.-4 p.m. | 76 E. 13th St., projectfarmhouse.org | FREE

At TED This Week, Two Speakers Got To The Root Of Things

At TED This Week, Two Speakers Got To The Root Of Things

by Nina Gregory NPR | April 28, 2017 12:46 p.m.

Interdisciplinary artist and TED Fellow, Damon Davis.

Getty Images, Maarten de Boer

At the TED Conference in Vancouver this week two TED Fellows talked about putting ideas to work to invigorate marginalized communities from within, while harnessing the collective power, creativity, and good will of residents who want to live in thriving, healthy and safe neighborhoods.

Devita Davison, executive director of FoodLab Detroit, offered a different means of taking action: “transformation and hope: through food.” She began by reminding the audience of Detroit’s apex in the 1950s, when the city’s name itself represented the strength of America’s manufacturing capabilities and ingenuity. “Now, today, just a half a century later, Detroit is the poster child for urban decay.”

Between a shrinking population and decades of disinvestment, Davison pointed to the persistent problem of scarcity for its mostly African-American population. “There is a scarcity in Detroit. There is a scarcity of retail. More specifically: fresh food retail. Resulting in a city,” she said, “where 70 percent of Detroiters are obese and overweight. And they struggle… to access nutritious food.”

Emphasizing the proliferation of fast food and convenience stores — and the shortage of supermarkets and fresh produce — Davison said, “this is not good news about the city of Detroit. But this is… the story Detroiters intend to change. No… this is the story that Detroiters ARE changing. Through urban agriculture and food entrepreneurship.”

Despite — or perhaps because of — deindustrialization and a rapidly shrinking population, Detroit has, what she calls, “unique assets.” Specifically, the city has some 40 square miles of vacant lots. It is close to water, the soil is fertile and there are a lot of people willing to work, people who also want fresh fruits and vegetables. And what’s happening, Davison said, is, “a people-powered grass roots movement… transforming this city to what was the capital of American industry into an agrarian paradise.”

As the audience applauded, Davison continued, “For those of us who are working in urban agriculture in Detroit, Michigan today, our vision for the future of the city is very clear. We’re working to make sure Detroit is the most sustainable, most food secure city on planet earth! And we’re just getting started.”

She detailed some of the grassroots progress underway: more than 1,500 urban farms and gardens where more than just produce is being grown. Community is also being cultivated on these plots of land as people grow food together. Davison invites the audience along, “Come walk with me, I want to take you to a few Detroit neighborhoods, and I want you to see what it looks like… folks who are moving the needle in low-income communities and people of color.”

She showed a photo of Oakland Avenue Farms, in Detroit’s North End neighborhood. It looks like a small city park, except for the abundant plants pouring out of tidy planters and growing in large, green bushes from the ground. Davison described the five acres as, “art, architecture, sustainable ecologies and new market practices. In the truest sense of the word, this is what agriCULTURE looks like in the city of Detroit.”

A $500,000 grant will allow the farm to do everything from designing an irrigation system to rehabbing a vacant house and building a store produce to sell. They’ll host culinary events where guests will not just tour the farm and meet the grower, but have chefs prepare farm-to-table dinners with produce at peak season. “We want to change people’s relationship to food. We want them to know exactly where their food comes from that is grown on that farm that’s on the plate.”

Davison’s tour traverses the city to the Brightmoor neighborhood on the west side of Detroit, a lower income community with about 13,000 residents. In this community, Davison explains, they’re taking a block-by-block approach to addressing the lack of access to healthy food. “You’ll find a 21-block ‘micro-neighborhood’ called Brightmoor Farmway. Now what was a notorious, unsafe, underserved community has transformed into a welcoming, beautiful, safe farmway, lush with parks and gardens and farms and greenhouses.” She showed images of a blossoming youth garden, an abandoned house that’s been painted into a giant blackboard where people draw bright messages for each other and a building the community bought out of foreclosure that’s been transformed into a community kitchen and cafe.

Her final example is a nonprofit organization, Keep Growing Detroit, whose aim is to have most of the city’s produce grown locally. To that end, the organization has distributed 70,000 seeds which helped lead to some 550,000 pounds of produce being grown in the Motor City.

“In a city like Detroit where far too many African-Americans are dying as a result of diet-related diseases,” she acknowledges the progress being made on the food scene there, pointing to Detroit Vegan Soul, a restaurant that grew from delivery to catering to two restaurants that serve plant-based food. “Detroiters are hungry for culturally appropriate, fresh, delicious food.”

Davison ended her time on the TED stage by describing the work of her organization, Food Lab Detroit. They help local food entrepreneurs build their businesses with everything from incubation, to workshops to access to experts and mentors so that they can, “grow and scale.” While acknowledging that Detroit’s problems are deep and systemic, Davison offers some hope: those small businesses, run by people traditionally excluded from the business world, last year provided 252 jobs and generated more than $7.5 million in revenue. Not mention lots of delicious, nutritious meals grown from the ground of what’s for too long been seeded with despair and decay.

Before interdisciplinary artist and TED Fellow, Damon Davis, took to the stage on Monday, an excerpt from his film, “Whose Streets,” was shown. The documentary, about the unrest in Ferguson in 2014, premiered earlier this year at the Sundance Film Festival and will open in theaters on August 11.

Davis began his talk by acknowledging his fear while standing onstage. “But what happens when, even in the face of… fear, you do what you gotta do. That’s called courage. And just like fear, courage is contagious.”

From East St. Louis, Illinois, Damon said that when Michael Brown, Jr., was gunned down by police, he thought, “He ain’t the first, and he won’t be the last young kid to lose his life to law enforcement. But see,” he continued, “his death was different. When Mike was killed, I remember the powers that be trying to use fear as a weapon. The police response to a community in mourning was to use force to impose fear. Fear of militarized police, imprisonment, fines. The media even tried to make us afraid of each other by the way that they spun the story… this time was different.”

A musician and an artist whose work is in the permanent collection at the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture, Davis’ work tells the story of contemporary African-Americans. After the protests had gone on for a few days, he felt compelled to go see what was going on. “When I got out there, I found something surprising. I found anger… but what I found more of was love — people with love for themselves, love for their community, and it was beautiful. Until them police showed up. Then a new emotion was interjected into the conversation: fear.”

Then, he said, that fear turned to action: yelling, screaming, protesting. Davis went home and started “making things specific to the protest… things that would give people voice and things that would fortify them for the road ahead.”

He took photographs of the hands of the people there, portraits of protest. He posted them on boarded-up buildings and hoped it would boost the community’s morale. Those photos are now in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture.

But he and his filmmaking partner, Sabaah Folayan, wanted to do more. So they started making their documentary, “Whose Streets.”

“I kinda became a conduit for all of this courage that was given to me. And I think that’s part of our job as artists. I think we should be conveyors of courage in the work that we do. We are the wall between the normal folks and the people that use their power to spread fear and hate, especially in times like these.”

As the TED audience, which includes powerful leaders from corporate and cultural institutions, sat rapt, in silence, he turned to them, “I’m going to ask you, y’all the movers and shakers, y’know,” he whispered, “the ‘thought leaders.’ What are you going to do with the gifts that you’ve been given to break us from the fear that binds us every day? Because, see, I’m afraid every day. I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t… but once I figured out how to use that fear, I found my power.”

Metropolis Farms: Vertical Farming Designed to Grow Out, Not Up

Jack Griffin of Metropolis Farms. Credit: Tricia Burrough

Metropolis Farms: Vertical Farming Designed to Grow Out, Not Up

The Philadelphia-based startup is looking to change the thinking around the green-collar economy, building a sustainable, modular design around optimized indoor farming technologies.

By Matt Skoufalos | April 27, 2017

Photos by Tricia Burrough

Griffin holds a tray of microgreens grown at Metropolis Farms. Credit: Tricia Burrough.

While the first harvests of spring herald the upcoming farmers market season in South Jersey, across the river in South Philadelphia, Jack Griffin has been hauling in crops all winter long.

On the second floor of a warehouse in the 2400 block of Water Street, he’s just a few blocks away from the other shipping and receiving terminals that supply many area supermarket chains with fresh produce.

But in a fraction of the physical space—and at a fraction of the costs of growing and shipping those fruits and vegetables there from across the corners of the country—Griffin’s Metropolis Farms is quietly growing their organic, non-GMO, vegan-certified competition.

More to the point, Griffin is growing a business that he believes can close gaps in food insecurity, social justice, and sustainability.

“The transactional nature of food means that we have a lever to change the world,” he said. “Everybody eats. The conversations around food are so ingrained in our society [that] in between those transactions is an opportunity.”

Seedlings at the Metropolis Farms headquarters in Philadelphia. Credit: Tricia Burrough

Indoor vertical farming has been touted as “the next big thing” in the green-collar economy for about the past half-decade.

In September 2016, AeroFarms of Newark drew national headlines for the massive scale of its 69,000-square-foot, $30-million operation.

The company converted a shuttered steel factory into a indoor greenhouse the company says is the largest indoor farm in the world, capable of producing 2 million pounds of crops per year, according to CNN.

But Griffin said the thinking that produced it is grandiose and wrongheaded: in his opinion, the key to vertical farming is actually horizontal growth.

“If I’m ever the world’s largest vertical farm any way other than by accident, shoot me,” he said. “We don’t need the world’s largest farm, we need a dense network of independent, smart farms.

“Everybody’s got the same idea; ‘I’m going to build 60 farms,’” Griffin said. “Who’s going to buy 60 farms at $26 million a farm? We can make a profitable farm with our stuff for $600,000.”

Griffin claims the technology behind Metropolis Farms is capable of growing 2 million pounds of produce in just 14,000 square-feet of real estate, and by using one-tenth the energy of a system like AeroFarm’s. Powered by a rooftop solar array on Swanson Street in Philadelphia—where Griffin says he also can recapture 2 million gallons of water annually—Metropolis Farms is made to be energy-independent and disaster-resistant.

It also doesn’t need prime real estate to operate, or even much of it at all. By licensing the technology behind his work, which includes the growing equipment and seedling optimization schedule, Griffin is optimistic that he’ll be able to create a distributed indoor farming culture, not just a farming network. His licensing agreements will include labor clauses about paid time off, living wages, and possibly an degree correspondence program to give inmates the chance of a stable career upon release.

“I think that social responsibility should be part of this,” Griffin said. “Equal pay for equal work, and no discrimination. Our goal is to get as many people as possible farming.”

Lee Weingrad, VP of Metropolis Farms. Credit: Tricia Burrough

“It’s the evolution of technology,” said Metropolis Farms vice-president Lee Weingrad, a U.S. Air Force veteran who co-developed the technology at the heart of the system with Griffin.

“Everything’s on a schedule,” Weingrad said. “We made it simple on purpose. Anyone with a high-school diploma can work here.”

The Metropolis Farms infrastructure is modular and able to be built from equipment available at a hardware store, which Griffin said cuts out the construction costs of retaining a design firm to build custom architecture.

It’s able to be dismantled for cleaning with quick-connect PVC systems, and features optimization algorithms that are designed to help crops flourish without the use of genetic modification.

The first-generation lights were based on a design of Nikola Tesla’s, but the ballast atop them retained too much heat and showed too much infrared light, Griffin said. Their replacements are high-intensity discharge (HID) lamps with a proprietary core, shielded with lightweight, reflective, and refractive German aluminum. They’re suspended from a motorized track, which carries the light across the plants on a timed sequence to simulate cloud cover.

At $25,000 per unit, each tower can produce 20,000 pounds of produce annually, Griffin said. He expects farms will consist of 15- to 50-tower implementations; each can yield 19 harvests per year versus two-and-a-half on conventional real estate.

Insectivorous plants keep the produce free of pests without chemical sprays. Credit: Tricia Burrough

Nearby carnivorous plants secrete nectar and resin, attracting and eliminating pests without chemical sprays.

The entire system can pivot from fruits and vegetables to things like pharmaceutical herbs, stevia leaf, or biodiesel jet fuel, all grown at a consistent grade and domestically.

“A lot of what we’ve done is fourth-grade math and freshman geometry,” Griffin said.

“We’re selling ubiquity: a simple system with architecture.”

Griffin isn’t lacking for interest in his model; as of a few months ago, he was sitting on more than $20 million in letters of intent from cities across the United States and Canada to bring his model there. He wants to start in the Philadelphia metro area first.

The challenge when you’re growing 2 million pounds of produce per year is generating enough institutional purchases—from hospitals, universities, prisons, and other governmental agencies—to generate local “velocity of capital” that creates sustainable economic change.

“How many schools do you have?” Griffin said. “They’ll buy locally if you can produce at scale. The key is to drive cities to understand that where they spend their money matters. If we spend that money on local food, we create velocity of capital; we create local jobs.

Sprouts are grown floating in an aqueous solution. Credit: Tricia Burrough

“When those people go and buy things because they’re making $18 an hour, they’re getting benefits, they’re having a life,” he said.

“If we can show them better food, and they buy it because it’s in their self-interest to buy the food, that’s enough.”

Griffin said his goal “is to have every city in the United States steal this idea” so that Metropolis Farms can manufacture the necessary equipment at its core in Philadelphia and ship it out to other markets, creating yet another level of employment. But he believes the model should take root locally first because it has the potential to be a key driver of regentrification and redevelopment with a critical difference: pushing out the poverty instead of the impoverished.

“In Fishtown, there’s 15,700 people,” Griffin said. “What if I could produce enough lettuce for the daily lettuce requirement of everyone in that community, enough tomatoes, and peppers, and so on? And surround that community with wings of prosperity?

“It’s a synergistic model instead of an exploitive one. It is the ultimate demand-based business.”

Indoor Farming Operations Still Unsure If They Are "Organic"

04/27/2017

Indoor Farming Operations Still Unsure If They Are "Organic"

Source: Specialty Food News

Categories: Industry Operations; Suppliers

Indoor farming operations will need to wait until the fall to find out whether the government considers their operations "organic," after the National Organic Standards Board delayed its ruling on the subject. In the meantime, operations can call themselves organic, but many in the industry are troubled by the uncertainty. Current guidelines are very specific on the type of soil that can be used by organic operations, but there is not a set rule on whether plants must be grown in soil.

“It's more about organic, certified farmers wanting to maintain their market share,” JP Martin of GROWx, an aeroponic farming system told Forbes. “The fertilizers are identical... so the argument that they use different nutrients breaks down." Full Story

How NASA LED Lighting Research Became A Hit Product: With Hedi Baxter Lauffer, Founder of LED Habitats

How NASA LED Lighting Research Became A Hit Product: With Hedi Baxter Lauffer, Founder of LED Habitats

For this interview, we sat down with Hedi Baxter Lauffer, Founder of LED Habitats, a company that has developed an indoor growing product was inspired by "fast" plant research developed by NASA and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. We discussed basic LED lighting tips, the future of LED lighting, and some of its history as well!

Introduction

UV: What's the background story and how LED Habitats got started?

Hedi: My husband and I have been working together in science education for a very longtime, decades now, primarily in that, our focus has been on getting plants into classrooms and informal science situations to try and help get more growing minds actively engaged with plants.

We are getting more and more removed from opportunities to grow plants and interact and understand the importance of plants. I taught high school for a while before I started really getting national and global outreach efforts and it always amazed me when we would do a unit on food, how many students had absolutely no clue where their food had come from.

So in our work, with getting plants into classrooms, both my husband and I were at University of Wisconsin Madison, working with "fast" plants.

They're really cool little plant that was (being studied) at UW Madison, as a research plant. It was just bred through traditional plant breeding to try and look for disease resistance in cabbage. Wisconsin used to be a really big cabbage growing state.

(Usually) cabbage has a two year life cycle, which makes it really hard to support farmers with disease resistance because it takes so long to look for it.

This little plant was bred because it cropped up when the scientist Paul Williams was looking for disease resistance. It went straight to flower instead of producing any fruit.

He bred for this super fast life cycle. It goes from seed to flower in just fourteen days, it goes through it's whole life cycle and produces viable seed in a month to forty-five days. So, it's really cool. And, it's used in classrooms a lot.

The thing is, because it's growing so fast, it needs twenty-four hour and very high quality light. So, we've all been developing light systems for indoor growing in classrooms and things like that, for a very long time. CFL's (compact fluorescent lighting) came out first, it was fluorescent, it was the compact fluorescent light bulb.

Then finally, LED's were kind of always in the background because actually that little fast plant was the first plant to successfully produce seed in micro-gravity, up in space.

UV: With NASA?

Hedi: Yeah with NASA. So, it gave us opportunities, especially my husband at the time, was working directly with UW Madison, with NASA and others, gave exposure to the idea of LED's.

Even before they were a viable option, because there weren't blue LED's until 2009, so you couldn't really use those successfully in growing plants, in horticulture.

UV: Which color were the earlier ones?

Hedi: They have advanced now, I think the very earliest ones were red. Well, that's areally good question. What the very first colors were and just know the blue was really hard to get. It won the Nobel prize, actually, for Physics in 2009.

When science figured out how to produce a blue LED. That opened them up for horticultural use.

So, anyway, we were trying to look at ways to get LED's into classroom study. and be able to switch to LED's, because we had a lot of concerns about a combination of things with non LED lighting options.

The heat that's put off by other light sources, the fact that there is mercury gas in fluorescent bulbs, It seemed like LED's was the way to to go.

But, every LED light that we tried out that was commercially available and, kind of, in our price range and size and scope for use in classrooms were not very high quality.

Because our plants are so sensitive to needing high intensity light, we could really be damaged easily when the intensity of the light declined.

UV: What do you specifically mean by quality in LEDs? Is it the intensity or are there other factors like spectrum?

Hedi: It's both. (intensity) and the spectrum that they're emitting, but I think for us, what we we're detecting most was the decline in intensity. In pretty short periods of time, like eight months to a year, we would notice changes.

Later, we learned that that was because when there's quality factors both in the LED chip itself and in the design of the match between the drivers that are pushing electricity, electrical energy into be converted into light energy. If the drivers are over pushing the LED chip, they burn them out.

(As a result), you do have a decline in quality over time. In a much faster time than what LED's are technically specified to last for.

My brother had been off the grid in New Mexico, I knew he'd done some stuff with LED's, I reached out to him and said, "Do you know anybody who's working with LED's, we're trying to find some people besides the scientists here that we've been working with at the University to help us come up with a low cost, relatively low cost solution for classroom?"

So, my brother introduced us to this German cabinet maker who is now our colleague and partner, he's been working with LED's for a long time in kitchen cabinetwork; and, he's a German craftsman, a cabinet maker, so, it was like this perfect triad of my husband and I with our plant backgrounds, I have a very strong agricultural background, I used to run a wholesale organic truck farm, many years ago.

All of these things converged and came up with this really clever design for being able to raise and lower the LEDs and how to house the LEDs, in a hood that is completely silent and self-cooling, and it worked beautifully. We tried it out, did prototypes, and got plants growing wonderfully and then we had them sitting around in our house.

As we were trying them out and everyone who walked in said where do I get one of those?

At that point we realized maybe this isn't just for school. Maybe this is actually a broader impact thing. And, that's how we came up with the company.

UV: The research and the inspiration is with that one cabbage plant that you mentioned, is that exclusively what you try to grow in the system now? Have you brought in the reach, to other types of micro greens or whatnot?

Hedi: Yes, we have definitely broadened, even in our prototype work we broadened. The advantage that we had in doing our initial work with the brassica, is the scientific (category) of the plant.

It's like a lab rat, in that it, its a good indicator for flowering plants, in general. And, because it does its whole life cycle in such a short time. We can group past prototypes to see how they effected the grooming, vegetative growth, seed production, stuff like that in really rapid cycles.

Once we've got to where we were really pleased with what we we're seeing, then we could start going out to longer growing crops.

UV: Right. So, have you guys seen that with a really high quality LED light, you can quicken the flowering and general growth of any plant? Like, regardless, of it's life cycle. You mentioned that the quality of the LED light helped you speed up even the fast plant. What's the multiplier in terms of productivity and speed to the flowering or any point in growth, when you have really high quality lighting?

Hedi: There are (multiple) key elements in the environment that affect the rate of growth, temperature often is a big one. Nutrient content, volume of the soil, so there's other factors besides the light.

But, the quality of the light and the availability of the light, in terms of intensity, and spectrum. It's so cool to work with, because you're plant responds by really producing strong, vigorous plants.

So, while it might be, I could keep my plants in very cool growing conditions and it wouldn't be that the LEDs would speed them up, necessarily, if it affected the cold.

But, what I would see, because of the light, is these really stocky, sturdy plants with large mass. They're really thriving. You'll notice the difference if you side by side grow six tomatoes under the fluorescent and LEDs that are full spectrum because the fluorescent tend towards the blue, the plants elongate and much more left out and reaching for light.

And they are so vulnerable to that. When you put them under LEDs, it's so satisfying to see, wonderfully, stocky little seedlings.

It's really cool as a plant lover, it's really fun to grow under really high quality lighting.

UV: Can you talk about, I don't know how much interaction you have with people who are just getting started; maybe there are people who approach you tobuy but what do you see is the biggest mistakes that people make?

Or, biggest misconception about LED lighting?

Hedi: That is really something that we encounter a lot, actually. There's people who are trying to grow micro greens, there's people who are trying to grow herbs or medicines, or all kinds of things. And, I think there are three things that, kind of, continually repeat themselves.One is, the confusion about how to compare different lights, because in the past, when we use incandescent bulbs, we talk in sense of watts. And, then in terms of lumens.

But, actually watts don't matter with LEDs. That's not a good measure, because they beauty of the LEDs is that they hardly require any input of electricity, which is what watts are made of.

To have a really high output,so, you know, you can't compare an incandescent or a fluorescent wattage input with the output of the LED. It's just not a good measure. And lumens are a measure for human. So, shifting to where we're talking about the photosynthetic area of radiation that is emitted or hard value on things like that, that's a big challenge. And, the LED world does not adjust that well, we don't have a good standard for how we talk about light, lighting or label them. Although, that's coming, hopefully.

I want to make sure that I also touched on, there is a real big misconception among those who have been looking at LEDs, that they don't give off heat.

They actually do. A lot of the quality of the LED chip and it's mount, and the quality of the LED lamp itself, is how that heat is dealt with.

That's the critical thing with the LED.

So, there needs to be a really effective design to the way the LEDlamp is engineered so that the heat dissipates really quickly. And, that prolongs the life of the LED and the lives that it has good intensity.

So, I guess that is the third thing I would say is a big misconception. That an LED is an LED is an LED and that is not true.

There is high quality LEDs, that are really made by reputable manufacturers and there's cheap, crappy ones that come, trying to flood the market with something that looks much more affordable.

UV: If you wanted to set up a dead simple urban farming system, how would you do it?

Hedi: Well,I think the dead simple part is the hanging of the LEDs and determining what the footprint is going to be that you want to light up.

So, LEDs, the chips themselves, tend to be uni-directional, that's part of what makes them really efficient. They're not shooting light off out the back and sides, they're shooting it in the direction that you point them.

You can put lenses on them that broaden their footprint, their lighting, but whenever you do that,you're also then distributing their intensity over a greater area (and as a result, reducing intensity).

I think the key is, deciding how much space are you trying to light well. Then you want to be the one that rigs how the lights go up and down or do you want to get a system that already does that for you.

Because the beauty in the LED is that they're built well so they dissipate their heat well. You can have your plants, the canopy top over tops of your seedlings or whatever just a few centimeters from the LEDs themselves. That's where you're going to have the high intensity. That's the way that you want to give your plants maximum lighting. So, you need to either raise the plants up and down or lower the lights.

UV: Keeping the focus on the hanging mechanism, that's the key take away.

Hedi: That and then the quality of the LEDs that you're getting. So, if you're just getting a cheap one strip of LEDs, be aware that you can't put that down the middle of a big, wide tray and expect that it's going to light the outside edges.

UV: How do you make sure that you're on the right track (with LED quality)? Is there some kind of measure? On YouTube, you see people measure the intensity. What tools or what do you suggest for doing the quality assurance? Or, I guess coverage assurance?

Hedi: You can get a little PAR meter, its called. That would be your most accurate measure of how many photons are actually striking the leaf surface. And, those are fairly affordable, although it's more of an investment than I would call atypical do-it-yourself thing.

So, I guess I would advise that you either do some research and make sure that the company you're buying your LEDs from LED lamp is what they actually address how much output there is, in terms of the spectrum that the lights are giving.

The PAR value, and when they tell you what the output is, that they tell you how to measure that, how far away from the light that was. If it's a good, reputable company, they will tell you what the footprint is being lit beneath it.

I would just be leery if it seems like it's over stating what is possible with the LEDs, you know then I would just be leery. I've bought enough cheap ones in our prototyping work and before we started doing LED Habitats.

You end up investing more money than you wanted anyway on ones that you can't continue to use, if you've got really cheap ones. They just won't work.

UV: So, what are some of the, what are some of your favorite brands? What would you recommend? Obviously, besides your own system.

Hedi: We've been pretty impressed by some of the higher end lights. Like by kind. You know, I would have to actually give you a list of, the problem is that, the world that I work in because I've had the benefit of being in the University system. The lights that we've had really good luck with are very high end horticultural LEDs.

So, when we tried to go into the lower, more cost effective, like you'd bring into your home or something like that range, things like Aero Garden and stuff like that.

That's where we started running into problems and that was what drew us to do the LED Habitat (product creation).

I could try and come up with some responses for you. Mostly, I've had people send me pictures of other LED systems that they're trying to use and some other things.

Their little seedlings are all elongated and stretching and reaching for the light, I just haven't been very impressed yet.

UV: What do you see as the future, what is the next wave of technology that will downsize in (LED) cost so that they're more available to the average person?

Is there a new type of LED? Are there new blends? What do you see as the next big trend?

Hedi: Iwas really impressed at the first annual LED Light and Horticulture Conference that was in Chicago. I was really impressed by how much enthusiasm there was towards the place that LEDs will take in horticulture.

Certainly, high pressure sodium still is a big, important light source for indoor growing.

I think that it's clear that with this vertical farming movement, the fact that you can layer into tight spaces,the growing space and the lighting is just phenomenal. And, it's pretty exciting to look at some of the large scale projects that are taking place with vertical farming.

I'm sure that LED technology is going to continue to get better. I think already even, it's pretty affordable. I think that on a small scale, it's not that bad.

It'sworth it. I think that there are some really nice options for tabletop or counter top growing. Helping to supplement the freshness of what you're feeding your family and larger scale urban farming too.

UV: What is your favorite fruit or vegetable?

Hedi: My favorite fruit or vegetable? Wow. Okay, avocado.

UV: If you had to give just one sentence of advice to somebody starting urban or vertical farming or LEDs or not. What would that advice be just in one sentence?

Hedi: Start with greens. Doing like brassica family greens. They're super fast, easy to get to know and they're really rewarding and good for you.

UV: Okay What's the best advice you ever heard from maybe a mentor or somebody that you encountered in the academic setting?

Hedi: Soil matters. You know, we sometimes, especially in academia, but in general, get really arrogant. Thinking that we can deconstruct nature and understand it all.

So, having humility about things and learning from the natural world and recognizing that soil is part of the picture, and it matters.

Thanks Hedi!

Water-Smart Farming: How Hydroponics And Drip Irrigation Are Feeding Australia

Water-Smart Farming: How Hydroponics And Drip Irrigation Are Feeding Australia

How energy-smart technology is allowing fresh vegetables to be grown in arid, isolated communities. Our Future of farming series is looking at the people, places and innovations in sustainable agribusiness in Australia

Is hydroponic farming the way forward for arid Australia? Photograph: Paul Miller/AAP

Wednesday, 26 April 2017 20.01 EDT

Sydney Fresh, Organic Angels, Freshline, Box Fresh. It’s a wonder Australian supermarkets still stock vegetables, such is the explosion of veg-box delivery services. OK, they may be a bit on the pricey side, but the food is out-of-the-ground fresh, typically free of chemicals and refreshingly wonky.

But for a veg-box scheme to work, the vegetables have to be grown locally. That effectively ruled out the arid wheatbelt towns of Western Australia. Or, it did, before Wide Open Agriculture opened a huge greenhouse-like facility to grow fresh vegetables. Boxes destined for domestic doorsteps have been leaving the Wagin-based site loaded with cucumbers, capsicums, tomatoes and the like.

Because we don’t rely on soil, we can osition our farm closer to centres of population

Philipp Saumweber, Sundrop

“We’ve had a lot of anecdotal feedback that we have brought the taste back to vegetables, particularly our tomatoes,” says Ben Cole, executive director at Wide Open Agriculture, the startup behind the initiative. “But our key is selling fresh vegetables in a region that doesn’t have many other local growers.”

The venture is tapping into growing consumer demand for food that is fresh and that doesn’t (environmentally speaking) cost the earth. It uses drip-irrigation technology, for instance, that requires only 10% of the water needed for open-field agriculture. In addition, the 5,400 square metre facility is equipped with a retractable roof and walls that open and close automatically, thus reducing water loss to evaporation.

The water used at the high-tech farm is sourced from natural surface water runoff that is directed into a series of dams before being pumped via a solar-powered system for use in irrigation. By capturing water high in the landscape, Cole argues, the wheatbelt’s first major vegetable producer is able to make use of it before it becomes saline.

“The wheatbelt has seen reductions in rainfall up to 20% over the last 20 years, so water scarcity is an issue for traditional wheat and sheep farmers,” says Cole, who holds a doctorate in environmental engineering and recently exited a successful social enterprise in Vietnam.

Wide Open Agriculture believes its agroecological approach to farming could usher in a new age of vegetable production in the wheatbelt. With its first harvest only just completed, it is already looking to list on the Australian Securities Exchange to raise finance for a second large-scale unit.

Another new player in Australia driving supply of water-smart food is Sundrop Farms. The Adelaide-based firm is the first company in Australia to develop a commercial-scale operation using hydroponic technology.

Sundrop Farms’ 65-hectare facility near Port Augusta in South Australia. Photograph: Sundrop

Pioneered by companies such as BrightFarms and AeroFarms in the US, hydroponic farming requires no soil or natural sunlight. Instead, plants are grown in trays containing nutrient-rich water and encouraged to photosynthesise by low-energy LEDs.

“Hydroponics is a thriving industry right across the globe, with produce being grown in a huge variety of environments” says Philipp Saumweber, a former investment banker who heads up the company. As if to prove the point, Sundrop has located its 65-hectare facility in an area of virtual desert near Port Augusta in South Australia.

One of the criticisms of the technology is that it is energy-intensive, what with all those indoor lights and automated heating and cooling systems. Sundrop has successfully ducked that charge by installing a concentrated solar power plant with 23,000 flat mirrors to meet most of its energy needs.

Saumweber is quick to push the water-efficiency credentials of the indoor farm too. With precious little rain or subterranean water to draw on, Sundrop has opted to pump seawater from the ocean and desalinate it. Its renewably powered desalination plant generates around 1 million litres of fresh water every day. The company also uses the seawater as a natural disinfectant, reducing the need for pesticides.

None of this comes cheap, mind. Sundrop’s Port Augusta farm cost a reported A$200m. Yet Saumweber insists this high upfront investment will be offset in the long run by lower operational costs, thanks to the use of cheaper renewable energy.

What can’t be argued with is the net result: 15,000 tonnes of tomatoes a year from a patch of land that is barely habitable, let alone productive. The prospect of siting such facilities inside cities is also a very real possibility, Saumweber adds. “Because we don’t rely on soil, we can position our farms closer to centres of population to greatly increase the efficiency of our supply chain.”

For the most part, however, water-smart technologies such as hydroponics and aquaponics (a related system that uses fish waste as an organic food source for plants) remain the preserve of hobby producers in their backyards.

For Murray Hallam, a Queensland-based expert and lecturer on aquaponics, the sector struggles with being seen as “just for hippies and way-out vegans” – an image he insists is false. A cultural propensity to think “it’ll be all right, mate” also holds back people from taking the risk of water scarcity and climate change seriously with respect to future food production, he argues.

The country is missing a trick, he continues: “In a regular farm, it doesn’t matter how well you organise it, when you irrigate, about 70% of the water evaporates straight away. Then the water that does get into the soil usually ends up going down to the subsoil and leaking away … taking with it the nutrients and fertiliser.”

Two of Hallam’s students have gone on to create multimillion dollar aquaponic businesses: Mecca in South Korea, and WaterFarmers, which has farms in India, Canada and the Middle East. He fears it will take a food crisis for Australian consumers to step up en masse and demand similar innovative solutions from the country’s agricultural industry.

Back amid the wheat fields of Wagin, Cole is more optimistic. Wide Open Agriculture is now looking to break into the local hospitality and retail market. It has opted for the brand name, Food for Reasons. For once a product that says what it is on the tin – or box.

Teacher In Remote Inuit Community Teaches Students To Garden

Teacher In Remote Inuit Community Teaches Students To Garden

Adam Malcolm hopes to eventually raise the funds for a greenhouse.

Adam Malcolm, a high school teacher in Qikiqtarjuaq, Nunavut, is trying to raise funds to build a greenhouse for his students to use to grow fruits and vegetables. (PROVIDED BY ADAM MALCOLM)

By ELLEN BRAIT Staff Reporter

Wed., April 26, 2017

Adam Malcolm, a high school teacher in the remote Inuit community of Qikiqtarjuaq, Nunavut, has a simple plan: teach his students to garden.

“But nobody around here is a natural gardener,” Malcolm said. “There’s nothing to garden and there never was.”

Malcolm, who teaches at the Inuksuit School, is trying to help combat food insecurity for his students by teaching them to grow their own fruits and vegetables. He has about eight Grade 10 - 12 students in his class on a “good day,” and 16 students during the two periods he spends teaching eighth and ninth grade. And they’ve already started growing some plants inside the school.

“I was trying to look at ways that I can be a positive influence on the community outside of the school,” Malcolm said. “I feel like starting off with just the young people first and giving them some skills to be able to do some gardening might be a good first step.”

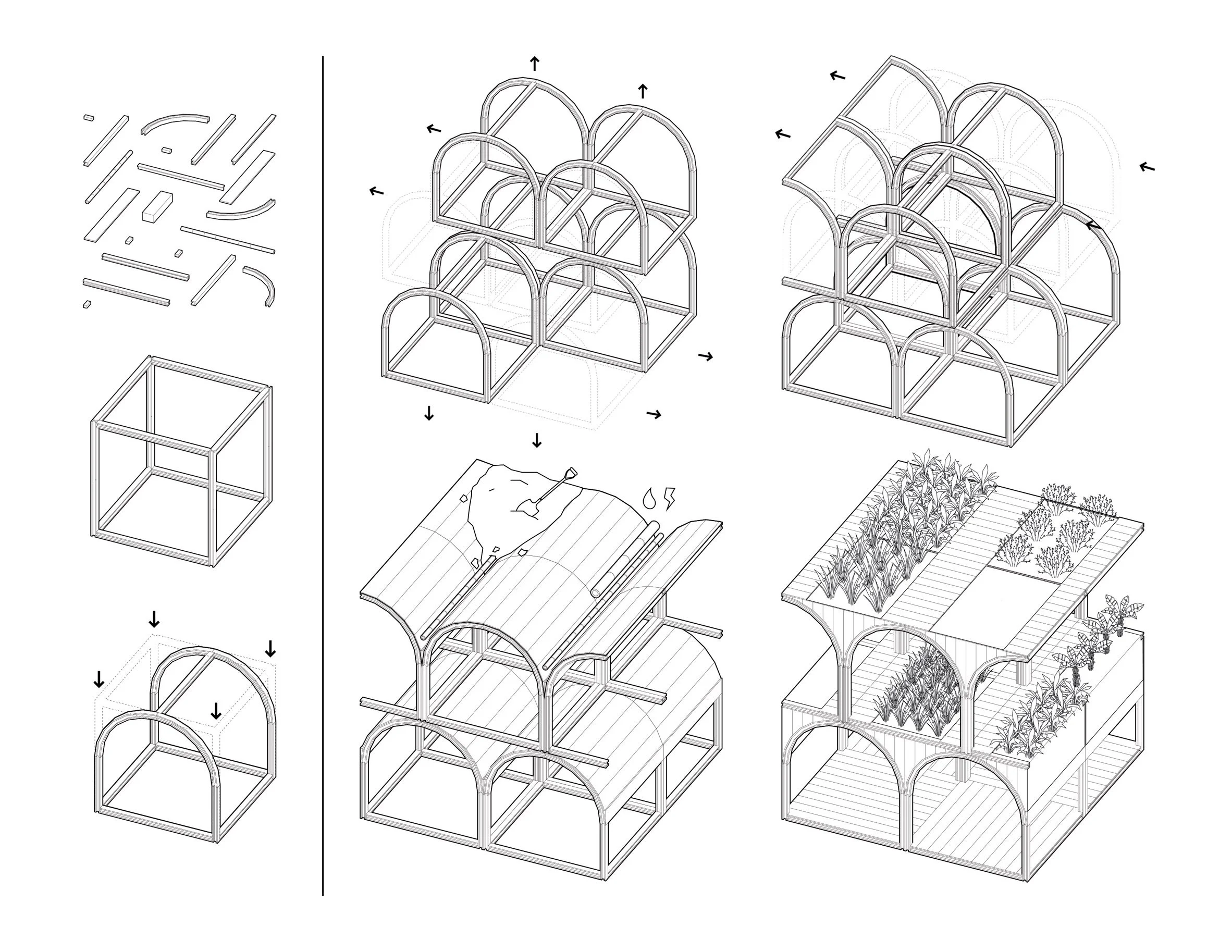

The goal is to move the student’s gardening outside and into a greenhouse before summer vacation starts. In order to do that, he has to raise the funds to buy a greenhouse.

He has started a crowdfunding campaign, looking to raise roughly $4,350 dollars in order to purchase a greenhouse and ship it up from Ottawa.

Food insecurity is a major issue in Nunavut. According to a report released in 2016 by University of Toronto researchers, nearly 47 per cent of households in Nunavut experienced some level of food insecurity in 2014. This included 19.3 per cent of households experiencing severe food insecurity. The second highest prevalence of food insecurity was in the Northwest Territories at 24.1 per cent.

Malcolm said with the installation of a greenhouse, he’s hoping they can start to “bypass the crazy prices at the grocery store.”

The Nunavut Bureau of Statistics' 2016 food price survey which compares Nunavut communities food prices with average Canadian prices, compiled by Statistics Canada, showed a large gap in prices between Nunavut and the rest of Canada. Shoppers in Nunavut paid $5.32 for canned tomatoes while the average Canadian was paying $1.60. Carrots cost about three times more at $6.90 in Nunavut compared to $2.25 in other parts of Canada, and oranges were approximately two times as expensive at $7.10, compared to $3.47.

Malcolm said he plans to offer gardening as a weekly science project or after school extra-curricular, only for students who are interested.

“There is a lot of interest among students,” he said. “They love planting stuff and growing in class too. It’s a novelty for them to see plants bearing fruit because you just don’t see it in the wild here.”

He’s already ordered seeds for a variety of fruits and vegetables including tomatoes, beans, melons, and carrots, and he has several litres of soil ready to use. He’s also hoping to obtain a small heater as “it’s cool at night.”

Eventually Malcolm is hoping gardening their own food is “something that the community will embrace too.”

“I’m starting small, having the greenhouse here,” he said. “And starting with the students will be the introduction in the community.”

The municipality of Qikiqtarjuaqhas also taken steps to help end food insecurity in their community. Memorial University’s branch of Enactus, a not-for-profit organization, will be sending three hydroponic systems to the municipality, as part of Project Sucseed, an initiative to address the need for fresh affordable produce in Northern Canada. The hydroponic systems can grow anything that’s not a root vegetable, according to Kate Fradsham, a volunteer with the organization who runs the Nunavut expansion of Project Sucseed.

“This is just a way to create community interest for the very art of growing which is not that common up here,” said David Grant, economic development officer for the municipality of Qikiqtarjuaq.

In five weeks, a system can yield 12 heads of lettuce. And in one harvest, 122 tomatoes or 360 strawberries can be grown, according to Fradsham.

“Food is a basic right and as Canadians, we’re here to be able to provide food to other Canadians,” Fradsham said. “We can’t forget that northern Canadians are part of Canada and they deserve the same access to food that we do.”

Read more about: Arctic

Will Vertical Farming Continue To Grow, Or Has It Hit The Greenhouse Ceiling?

Will Vertical Farming Continue To Grow, Or Has It Hit The Greenhouse Ceiling?

Agriculture has come a long way in the past century. We produce more food than ever before — but our current model is unsustainable, and as the world’s population rapidly approaches the 8 billion mark, modern food production methods will need a radical transformation if they’re going to keep up. But luckily, there’s a range of new technologies that might make it possible. In this series, we’ll explore some of the innovative new solutions that farmers, scientists, and entrepreneurs are working on to make sure that nobody goes hungry in our increasingly crowded world.

A pair of lab workers, dressed head to toe in bright white biohazard suits, patrol rows of LED-lit shelves of lettuce, quietly jotting down a series of numbers and readings. Stacked some 15 to 20 feet high, the shelves cover nearly every inch of a massive 25,000-square-foot facility. As the lab hands pass by each row of lettuce, some in the germination phase, some ripe for picking, a psychedelic pink glow wraps around them, painting an almost extraterrestrial setting.

This isn’t a scene plucked from Alfonso Cuarón’s latest blockbuster; it’s an everyday occurrence at a vertical farm in eastern Japan.

The farm was built in the wake of a devastating magnitude 9.1 earthquake that rocked Japan in 2011 and led to a temporary food crisis in the affected area. After seeing the chaos, Japanese plant physiologist Shigerharu Shimamura decided to develop a more consistent, reliable model for manufacturing lettuce. He ended up turning an old Sony-backed semiconductor facility into the planet’s largest vertical farm – a huge operation that now churns out an astounding 10,000 heads of lettuce per day.

“We’re talking coming in and supplying 10, 20, 30 percent of the food supply of an entire city.”

Recently, the facility (and others like it) has become a poster child for indoor farming. There’s now a rapidly expanding movement to bring this type of food production to urban centers all over the globe.

It’s easy to see the appeal. In theory, indoor farms could allow us to grow food 24 hours a day, protect crops from unpredictable weather, and even eliminate the use of pesticides, fertilizers, and herbicides. If these farms were built in cities, we could potentially mitigate crop loss due to shipping and storage, and cut down on fossil fuel usage because food wouldn’t need to be transported very far after harvest.

But of course, the idea of indoor farming isn’t without its detractors. Critics are quick to point out the method’s shortcomings when it comes to efficiency, effectiveness, and cost. In their eyes, vertical farming simply isn’t something that can be deployed on a large enough scale, and therefore isn’t a viable solution to our problems.

So, who’s right? Should we start building giant, garden-stuffed skyscrapers in our cities, or abandon the idea and devote our efforts to improving existing (horizontal) farms? Could vertical farming legitimately help us meet the world’s growing demand for food, or are we chasing the proverbial pie in the sky?

Upward trajectory: the benefits of growing vertically

In his seminal book, The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century, Dr. Dickson Despommier puts forth the theory that vertical farming is a prime candidate to help solve the growing food, water, and energy crisis in the United States.

As populations continue to rise in urban centers around the globe, Despommier sees no other solution.

“As of this moment, the WHO (World Health Organization) and the Population Council estimate that about 50 percent of us live in cities and the other half, of course, live somewhere else,” Despommier said in a video. “Another thing we can learn, from NASA of all places, is how much land those 7 billion people — half urban, half rural — actually need to produce their food every year. It turns out to be the size of South America. So, the size of South America, in land mass, is used just to grow our crops that we plant and harvest. I’m not even talking about herbivores like cows, goats, or sheep.”

When the book was first published in 2011, the indoor farming industry essentially stood as a barren landscape, with few companies setting out to literally put vertical farms on the map. Now, with Despommier’s written blueprint in the wild, the concept has recently gained a good deal of popularity.

“It’s estimated that by around 2050, roughly 80 percent of the world’s population will reside in urban city centers.”

Aside from Despommier, a growing number of people strongly believe in a prominent future for vertical farms. Today, there exist throngs of vertical farming companies all geared toward making this innovative technology a reality. Unsurprisingly, it’s with Despommier and these upstart companies that the industry’s appeal rings the loudest.

Companies such as Bright AgroTech and AeroFarms have set out to educate and inform small farmers to grow locally in urban areas, while other firms like Freight Farms and Edenworks lean on unique and innovative growing concepts — such as shipping containers or rooftop aquaponics — to bring the idea to life. Thus far, there’s no real right or wrong way to go about it, and the recent influx of startups should only prove advantageous to the industry in the long run.

“I do believe there are a few players coming to the table that look poised to supplement local food supplies to a really significant degree,” aquaponics expert Dr. Nate Storey told Digital Trends. “We’re talking coming in and supplying 10, 20, 30 percent of the food supply of an entire city. So, you have this future where you have indoor growers taking on that task, and you have small guys that are kind of collaborating and cooperating to sell to niche markets, really high-value products. Then you have the big boys who are really kind of going head-to-head with some of your field producers, who are growing at much larger scales and interested in replacing that wholesale product.”

As Despommier states on his website, it’s estimated that by around 2050, roughly 80 percent of the world’s population will reside in urban city centers, with the population of the world ballooning by an additional 3 billion people over that time. To Storey’s point, the diversity of vertical farms should allow these urban areas to continue to function as they do today. That is, access to food should remain a basic function of society, as opposed to it serving as a luxury should food production dwindle in the future.

Like the Green Revolution from the 1930s to the 1960s, Storey believes the world sits poised for yet another research and development breakthrough regarding vertical farming.

“When you step back a bit, you begin to realize that we’re kind of on the verge of another Green Revolution,” he added. “I think that indoor agriculture plays a huge role in that. So, the 40,000 feet in the air perspective is it’s not just about supporting local demand for food, it’s about controlling the environment completely. This means eventually taking things out of the field entirely and putting them indoors.”

Bringing a high-flying idea back down to Earth

While the upstart vertical farming community largely agrees with Storey’s stance, there also exists a wing of detractors who point to indoor farming’s inefficiencies.

The loudest voice among these critics is former United States Department of Agriculture biologist Stan Cox. After serving for the USDA for 13 years as a wheat geneticist, Cox joined the Land Institute as a senior scientist in 2000, specifically focusing on plant breeding in greenhouses and fields. An author of several books looking at the past, present, and future of all things agriculture and food, Cox is an expert in the field — which is why his view of vertical farming as a scam is a perspective that should give anyone pause.

“This will never be able to supply any significant percentage of our food needs.”

Vertical farming’s largest hurdle — a concept Cox thinks should’ve “collapsed under its own weight of illogic” and that he says remains incredibly difficult to overcome — concerns its scale. Cox posits that to be truly effective, vertical farms would require an incredible amount of floorspace. Despommier envisions indoor farming as a means to avoid the degradation of soil, but turning currently cultivated land into soil-preserving indoor farms would require an almost unfathomable amount of space.

To get a true picture of this, Cox breaks down the floorspace requirement for growing just vegetables — which clocks in at roughly 1.6 percent of cultivated land in the U.S.

While that number may not sound like much, turning that 1.6 percent of cultivated land into a functioning indoor or vertical farming operation demands the relative floorspace of around 105,000 Empire State Buildings. As Cox also points out, even with that much dedicated space, 98 percent of U.S. crops would continue to grow at outdoor farms.

“A colleague and I originally did some back of the envelope calculations that show if we grew grain- or fruit-producing crops [in vertical farms], it would take half of the country’s electricity supply or tens of thousands of Empire State Buildings,” Cox told Digital Trends. “These huge numbers would show that this may be fine for growing, on the small side, fairly expensive leafy greens to be used in restaurants or local areas. But the two things we have to always keep in mind is the amount of energy and resources being put into each unit of food, and the second is the scale. This will never be able to supply any significant percentage of our food needs.”

Despite Cox’s calculations painting a grim picture for large-scale urban production of grain or vegetables, he did emphasize that he’s “all for” urban gardening, or growing food as close to a population center as possible. To Cox, it just “makes sense.” Unfortunately, small urban gardening operations won’t likely have any shot at replacing the more than 350 million acres of rural U.S. cropland that consistently churn out America’s food supply.

“We can only grow enough crops within cities to substitute for a very tiny portion of [our food supply],” Cox added. “We’re still going to depend on rural America for growing the bulk of our food. There’s no big problem with that, really. We certainly want for perishable food, like fresh produce, to grow as much as we can close to where we live. But for grains, dry beans, food legumes, oil seeds, quinoa, all of these dry, nutrient-dense foods with a lower moisture content that can be shipped with very little energy or cost (by rail), that’s still going to be grown around our rural areas.”

Plain and simple, Cox doesn’t see a way around the issue of energy as it pertains to vertical farms — at least for the sustained growth of something like grains or fruit. Because leafy greens require less light to grow sufficiently, it makes much more sense to operate vertical farms geared solely around these foods. Conversely, growing something like corn or wheat — which produce much more dry matter — just doesn’t seem like a feasible option if there’s an intention to keep energy, production, and food costs down.

Growing up: The future of vertical farming

With the vertical farming industry still very much in its infancy, its future remains somewhat murky. Despite the growing number of startups committed to nurturing the idea, its hindrances and drawbacks pointed out by critics like Stan Cox carry just as much clout. Because of this, it’s hard to confidently put stock in either its failure or success.

“The Achilles’ heel of vertical farming or gardening is that it just does not work out energetically.”

Vertical farming’s best shot at a lasting legacy may be to simply pump the brakes on continued advancement. As it stands today, the startups that currently run operations geared toward producing heaps of leafy greens might want to think long and hard about introducing anything capable of completely shutting down momentum — i.e., fruits, grains, etc. In this case, energy usage is the bane of vertical farming’s existence.