Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Hydroponic Farm In Lakewood, Colo., Takes Next Step

Hydroponic Farm In Lakewood, Colo., Takes Next Step

Photo courtesy Infinite Harvest |

The room Infinite Harvest grows food in look pink because only red and blue lights are used during photosynthesis.

Before 2002, Tommy Romano's life plans were not necessarily Earthly.

He was at the University of Colorado studing for his master's in aerospace engineering. His thesis was on ways to grow food in space.

But man still has yet to land on Mars, so Romano thought, why not tru this technology on Earth, first?

It took a lot of trial and error and growing food in his basement, including ears of corn. And in January 2015, Infinite Harvest began.

“The traditional ways aren’t fulfilling (the holes left by problems). If we held to the same traditions of farming ... we’d still be riding horses right now. We’re helping it take the next step.”

Infinite Harvest is an indoor hydroponic vertical farm. Currently the farm in Lakewood, Colo., grows 13 microgreens and lettuce. A week ago, when the Denver-metro area was hit with rain, hail and snow, the crops at Infinite Harvest weren't even touched by the elements.

TECHNOLOGY

That's the beauty of growing vegetables in an indoor hydroponic vertical farm — the weather is controlled by technology.

"We don't actively manage a lot," said Nathan Lorne, operations manager. "We really rely on her."

The "her" in this scenario isn't a human, but the greenhouse control system. A box containing machines and wires takes notes on everything that happens in the greenhouse.

The system controls how much water and nutrients the plants get, the temperature, humidity, carbon dioxide levels — anything that can and will affect the plants.

And, if something goes wrong, the control system will send a message to someone so they can come in to fix it.

The room doesn't have any natural lighting, only blue and red spectrum lights are used because that's all the plants need for photosynthesis. They go through day and night cycles.

One you leave the room, everything has a green hue to it because your eyes overcompensate after only seeing two hues of light.

The other lights just waste energy, which is against the goals of Infinite Harvest.

A tech-based farm might sound like it's just wasting energy, but the way the control system is set up, the farm actually pays about six times less than marijuana greenhouses pay in electricity costs each month. When it comes to energy comparisons, marijuana is the best comparison because both grow crops are grown indoors.

Another concern that Lorne said hydroponic farms raise is the amount of CO2 released.

But the system controls the amount of CO2 that is released at all times.

'BEYOND ORGANIC'

Lorne said one of the benefits of having an indoor farm is having complete control over what the plants are exposed to. Even more important for them, though, is what the plants aren't exposed to.

Before going into the farm, a person enters an air cleanser room. Air is circulating and that is where hair nets, hats, shoe covers or specific farm shoes are put on. This helps prevent some unwanted outside elements from getting in. There are traps that attract bugs to keep them from going in, too.

Because there aren't bugs or anything else in the farm, aside from what is planned, Infinite Harvest doesn't have to use genetically modified plants and there is no need to use pesticides.

Even organic farms use natural products to get rid of weeds or pests. Infinite Harvest doesn't have to.

Even with the organic trend, Romano said there aren't plans to apply to be organically certified because he thinks the "Colorado Proud" label means more.

And, "We're beyond organic," Romano said.

KEEP MOVING FORWARD

There are a number of worries and problems farmers face, and Infinite Harvest looks to find solutions for them, Lorne said.

"Everyone here loves the romance of traditional farming," he said.

Romano said the purpose of this farm is not to compete with traditional farming. In some ways, it is an ongoing science experiment. Because indoor hydroponic vertical farms are a fairly new, some of the technologies are on the expensive side.

But the energy saving measures the company is able to do even that out.

Romano said they're looking to expand, but they don't want it to be a big leap from what they're doing now. They want to take lessons learned and improve upon them a little at a time.

"There is no textbook," Lorne said.

That's something any farmer can relate to. As technology changes on farms, there's always an experimental phase before the technology becomes widely used.

That's why Romano doesn't see Infinite Harvest as a competing entity, but as the next forward step in the industry.

"The traditional ways aren't fulfilling (the holes left by problems)," Romano said. "If we held to the same traditions of farming … we'd still be riding horses right now. We're helping it take the next step."❖

— Fox is a reporter for The Fence Post. She can be reached at (970) 392-4410, sfox@thefencepost.com or on Twitter @FoxonaFarm.

Can Hydroponic Farming Be Organic? The Battle Over The Future Of Organic Is Getting Heated

Can Hydroponic Farming Be Organic? The Battle Over The Future Of Organic Is Getting Heated

By Dan Nosowitz on May 4, 2017

Aqua Mechanical on Flickr

Last month, the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) met in Denver, Colorado to discuss what might be the most hotly-debated subject in all of eco-agriculture: What, exactly, does "organic" mean?

The organic label is worth about $40 billion a year. An organic farmer can charge as much as twice the price for the same item—and work very hard for the ability to do so.

The United States is unlike most countries (or regions, like the EU) in that our organic certification can legally be extended to crops that are not grown in soil. Hydroponic and aquaponic produce is, typically, grown in perpetually-flowing water in which nutrients are dissolved, and in the US, some farms using these methods can be certified organic. Proponents of the hydroponic organic certification say that their farms can be more energy- and water-efficient than soil-based farms, that they can reduce transportation costs by being built basically anywhere (including indoors, smack in the middle of cities), and that they can be just as sustainable and eco-friendly as any traditional farm.

The other side—the side that wants organic certification to be restricted to soil-based farms—sees hydroponic organics as a victory for a spooky sort of agriculture controlled by corporations that perverts the very soul of the organic movement.

What does the NOSB, which is in charge of actually making this decision, think? They’re not sure yet. They determined in Denver that they have more questions than answers, and that they’ll need more data before making any decision. For now, hydrorgranics remain legal.

First, some background

Hydroponics and other technologies like it have captured the imagination of farmers for decades; the technologies enable young farmers, increasing numbers of whom live in cities, to create hyper-local farms that actually produce solid yields. Some systems incorporate big fish tanks—tilapia is a popular choice—which are strung together with the plants to create an ad-hoc sort of ecosystem.

“It’s a very natural-type system,” says Marianne Cufone, executive director of the Recirculating Farms Coalition. “It’s mimicking nature, where the fish do what they do in the water to live and breathe, and they create nutrients in doing so, and those nutrients then are taken with the water to the plants, and the plants absorb the nutrients they need to live from the water, cleaning the water for the fish.” It is, basically, a high-tech artificial pond—a closed-loop system where the fish help the plants and the plants help the fish. And we can eat both the plants and the fish.

These sorts of farms are gaining traction; most cities have a few. Many of them are too small to really be commercial—maybe they’re educational farms, maybe they’re startup-y experiments, maybe they’re an outpost of a restaurant or other facility that doesn’t rely on the farm as a sole source of income. Fact is, they’re popping up more and more.

Cufone represents these farmers, who put a lot of energy into making sure their farms are sustainable and ecologically sound. They reduce their water and energy use as far as possible, they use only accepted fertilizers and nutrients, and if they must use pesticide they’ll only use accepted organic varieties. Describing her own farm, Cufone says, “We have an open-air system, so we have natural pests and natural pest controls. We have bees and butterflies and helpful insects that keep away pests and so forth.”

In her view, Cufone and farmers like her embody the spirit of sustainability and responsibility that customers look for in an organic product.

…But not everyone agrees

“I feel bad for those [small] operations, that they’re getting wrapped up in this debate, but they are not the problem,” says Linley Dixon. Dixon is the chief scientist for the Cornucopia Institute, a group that represents small farmers and has become a major voice in opposition to hydro-organics. Cornucopia firmly believes that the organic certification should go only to farmers who grow in soil.

Their argument against hydro-organic agribusiness is multi-fold. First is their belief in the inherent superiority of soil-grown produce. Kastel repeatedly cited the superior flavor and nutritional content of soil-grown vegetables. (That last part is up for debate; there’s yet to be scientific consensus on whether organic food is more nutritious than conventional food. The former claim varies based on crop.) Cornucopia also believes that the concept—the soul, if you will—of organics isn’t just about the singular crop: it’s about the the ecosystem, the environment, and the planet. Proper soil-based organics ensures healthy soil for generations, allows for thriving communities of beneficial insects, and, in turn, an entire ecosystem around them. Organics is about the planet beyond the pepper, they say.

It’s probably worth pointing out here that Cornucopia repeatedly claims hydro-organic farms are “illegal,” while the hydro people repeatedly state that they’re following the letter of the law. Frankly, it’s too much of a tangle to go into: both sides make compelling legal arguments, but the real battle is not really about which side is, say, bending to abstraction a bunch of minor rules about nutrient sourcing—it’s about money and soul. But probably mostly money.

“This is like Soylent Green in the shape of a vegetable.” —Mark Kastel, cofounder of Cornucopia.

Cornucopia made it a point to say that they approve in spirit of small, sustainable hydro producers like Cufone; they think that stuff is cool, or at least cute. But they do not believe it should ever be labeled organic.

The organic label is worth about $40 billion a year. It is monstrously huge business, which is the only reason many farmers put up with the equally huge amounts of red tape it takes to actually get the certification. An organic farmer can charge as much as twice the price for the same item—and work very hard for the ability to do so. So while the organic standards were designed to reward the most conscientious of farmers, what it’s also done is entice less-conscientious corporations into hitting the bare minimum in order to rake in that sweet organic cash. This is all legal at the moment, keep in mind; Cornucopia is fighting to strengthen the restrictions on organic farmers, in a way that would box out those who, in their mind, are unworthy of the organic label.

The chief villains, to Dixon and Cornucopia, aren’t small timers, like rooftop farms in Brooklyn or progressive vertical projects in Chicago. It’s gigantic agribusiness corporations, chiefly Wholesum Harvest and Driscoll’s. Both of those companies have gigantic organic hydroponic businesses, selling tomatoes, cucumbers, squash, peppers, and berries, which are grown, in some capacity, in hydroponic greenhouses. “It’s almost science fiction, Dan, to say that we want all of our food grown in these hermetically-sealed buildings,” Mark Kastel, the cofounder of Cornucopia. told me. “This is like Soylent Green in the shape of a vegetable.” Kastel believes that these companies are not in the spirit of the organic movement and are thus deceiving customers who have a vision of organic produce coming from ethical farmers, harvested by ethical farmers in ethical overalls covered in ethical dirt.

Hydro-organics often does not include any outside interaction with the planet at all, being less spooky than Kastel thinks they are but no less hermetically sealed. When I presented that to Cufone, she protested. “Not all aquaponic systems are entirely closed,” she says. “For example, the system that we run, we take some of the solid fish waste out and use it on in-ground growing. A lot of people do multiple forms of growing on a farm.” But the current law doesn’t require any of that to earn the certification.

“I think adding new labels dilutes the USDA organic label, and I also think the whole ‘separate but equal’ thing hasn’t worked so well in the United States over the years.” —Marianne Cufone, Executive Director, Recirculating Farms Coalition

The bigger argument is about money, as the end of most arguments are. It is extremely easy for a hydroponic farm to transition to organic; all they need to do, as Kastel says, “is turn a valve.” (Basically, just replace any banned nutrients or fertilizers with permitted ones.) Turning a conventional soil-based farm into an organic farm is much, much more involved; you have to allow the soil to recover for three years before you can call your food organic.

That enables big business like Wholesum Harvest to pump their low-cost organics into the market, boxing out smaller, older producers. And there’s no way to tell the difference between hydro-organics and soil-based organics; there’s only one label, and it just says “certified USDA organic.”

What about a new label?

I offered a few possible solutions to this issue, all of which…failed. What about a totally new label, I asked both Cufone and the folks from Cornucopia? Say, USDA Certified Sustainable Hydro, with totally new rules for what makes a truly sustainable and ecologically-friendly hydro farm. Has a nice ring to it, right? Cornucopia said sure, who cares, they can do whatever they want. Cufone, though, wasn’t into it.

“No,” she said flatly. “Because USDA organic is the thing, it’s the thing that consumers know, and I think it’s really important for it to be the significant label in the United States. I think adding new labels dilutes the USDA organic label, and I also think the whole ‘separate but equal’ thing hasn’t worked so well in the United States over the years.” Whoof.

Okay, how about this genius idea of mine: USDA Organic Hydro. Again, separate rules, and a new label, but it has the word “organic” in there. Cufone thought this was a great idea. The Cornucopia people, not so much.

“It’s pretty telling that they want to steal our word,” says Dixon. Cornucopia does not want any farm besides a traditional operation wherein crops are planted in the Earth to have access to the word “organic,” in any way. That includes hydroponics, aquaponics, rooftop farming, container farming, all of it. “We’ve worked really hard for this word, and it means something, and they want it, and it’s not theirs,” says Dixon. “Let them build it for 30 years, like the organic farmers did.”

For Cornucopia, any use of the “organic” word is, yes, a perversion, but also not enough of a differentiation; considering how lousy the state of agricultural education is in this country, Cornucopia worries that people won’t much care about the difference between “organic” and “organic hydro.” And then they’re in the same position they’re in now: being boxed out by a bunch of techy corporations.

So where do we go from here?

There is no conclusion on the future of organics. It is a complete mess. Without proper education to ensure that customers know or care about the difference between conventional, organic, hydroponic, sustainable hydroponic, and who knows what else, as well as stricter rules to ensure that those labels actually mean what customers think they mean? We’re stuck with basically what we have, which is kind of a free-for-all.

Both sides have a point; both the Cornucopia folks and Cufone want the farmers they represent to be recognized and paid for her dedication to sustainability. How to ensure they both get what they deserve? There’s no real solution. That’s what the NOSB is grappling with. As to when they’ll make a decision? Any decision at all? We have no idea.

5 Ways Urban Farming Benefits Utah's Cities And Residents

5 Ways Urban Farming Benefits Utah's Cities And Residents

Utah League of Cities and Towns

Published: March 3, 2017 11:40 a.m.

This story is sponsored by Utah League of Cities and Towns. Click to learn more about Utah League of Cities and Towns.

Urban farming may sound like your hipster cousin's latest hobby, but, in fact, it is transforming the way Utahns grow and buy their food. Over the past several years, the benefit of locally grown food is becoming more apparent.

According to a study by Envision Utah, only 2 percent of fruits and 3 percent of vegetables in Utah are produced locally, and these percentages could decline significantly as Utah's population and land development increases. This has led to a huge demand for urban farming solutions that support both growers and consumers in the community.

Whether you're a long-time "locavore" or a newcomer to the world of urban farming, there are plenty of reasons to jump on this produce wagon and get involved in your local urban farming programs.

1. Support the local economy

Perhaps the most obvious benefit of buying and eating local is the economic value. Spending money at your farmer's market or through membership in a Community Supported Agriculture organization puts those funds back into your community. A study by the research firm Civic Economics found that 48 percent of money spent at a local independent business is directly or indirectly recirculated into that community — compared with less than 14 percent of purchases at chain stores.

By supporting your local producers, you help protect their livelihoods and improve the health of the local economy. Good for you, good for business, good for the community.

2. Access fresher, healthier food

But urban farming isn't just about business and economics. There are wonderful health and quality benefits for the consumer, too. For instance, food often travels hundreds or even thousands of miles from the source to your plate. In order to transport produce over such great distances, much of it is harvested before it is ripened and is highly processed with preservatives. This leads to less nutritious and less tasty food by the time it reaches your table.

In contrast, local produce is often picked that day and avoids some of the harsher processing and handling methods that detract from the taste and quality of the food. Plus, you have the added benefit of buying directly from the grower, so you can ask them questions about how they grew and handled the produce before it reached you.

Programs like the Salt Lake County Urban Farming program were created in part to facilitate these benefits and interactions. Program Manager Supreet Gill explains, "Increasing the local food supply is one of the biggest things that’s needed, so we connect farmers with available land," which in turn connects the local community with fresher, healthier food options while supporting local family farms.

3. Improve the environment

Locally sourced food also has environmental benefits. One of the most obvious and oft-acclaimed advantages is transportation. Because local food is produced right in the area, it doesn't have to travel as far to get to the consumer as traditional, mass-produced food. With fewer miles to travel, locally grown food tends to create a smaller carbon footprint.

But that's not the only environmental effect. Supporting the growth and development of local farms has numerous benefits to the local ecosystem. Urban farming and gardening adds much-needed support to local bird and insect populations, particularly bees, which have been declining in numbers over the past decade. As people cultivate rich and diverse gardens, bees will have greater sources for pollination, which benefits the bees and the growers. Not a bad deal for the Beehive state.

4. Bring communities together

One of the most rewarding benefits of urban farming is the community impact. Through programs like Salt Lake County's Parks to Produce and Commercial Farming initiatives, people living in cities and towns across the state have the opportunity to connect more closely with their food, their land and their neighbors. From participating in a CSA, cultivating a plot in a community garden, or buying food at the local farmer's market, urban farming provides multiple ways for people to interact with fresh local food and each other.

5. Empower individuals and families

When communities prioritize local food production, they empower individuals and families to increase self-reliance and sustainability. Gill explains that one of the main obstacles in her county is the lack of available, farmable land. The demand for local food is high, yet local farmers often don't have the land resources to produce enough food to meet that demand. Fortunately, a lack of available farmland is not the case in many Utah communities. And as the community works together to provide those land resources to farmers, and other public spaces for community gardens, people will have greater opportunities to provide for themselves and their families, and make food choices that will benefit their lives and the community.

Urban farming has grown in popularity over the years and with so many benefits, it's no wonder why. If you're interested in getting involved in urban farming but aren't sure where to start, Gill recommends purchasing a share in your local CSA, shopping at your farmer's market, or, if you live in the Salt Lake valley, participating in one of the four county community gardens.

Read more from the Utah League of Cities and Towns on DeseretNews.com or visit their website at ulct.org.

This Mumbai Ecopreneur Has Been Turning City Dwellers Into Urban Farmers for Over Half a Decade

This Mumbai Ecopreneur Has Been Turning City Dwellers Into Urban Farmers for Over Half a Decade

During a college project, Priyanka Amar Shah combined her love for nature with business skills to start iKheti, an enteprise that facilitates urban farming

by Sohini Dey

Priyanka Amar Shah attributes her love for greenery to her “nature loving family.” The Mumbai resident grew up in a suburban home whose balconies were always adorned with plants. It was also her affinity for nature that made her notice how barren the other balconies of her neighbourhood seemed in comparison.

Around 2011, Priyanka and her brother began growing herbs at home, plucking chillies and lemons for family dinners. During this time, she was pursuing and MBA from Welingkar Institute of Management Development & Research where she got an opportunity to present a business idea. Determined to use the opportunity fruitfully, she combined her love for nature with business skills to conceptualise iKheti, an urban farming enterprise.

Today, iKheti has become a full-fledged eco-friendly enterprise that facilitates farming among city dwellers with workshops, consultancy and gardening resources.

iKheti aims to create a sustainable environment

For this young ecopreneur, concern for environment goes hand-in-hand with a healthy food movement. Unlike other gardening ventures, iKheti emphasizes on growing edible vegetables, fruits and herbs. “Mumbai is great for growing edible plants. We have great sunshine and the weather is not as extreme as other cities,” Priyanka says.

Priyanka’s vision for iKheti’s vision is, “To create a platform for both, individuals & communities to grow healthy consumable crops within their premises & promote sustainable urban farming.”

Today, a number of organisations work in the same area and the number of people invested in urban farming is on the rise. Yet in 2011, when Priyanka got started, it was still unexplored territory and people had to be educated on the benefits and methods of farming in small spaces.

“We started with workshops,” says Priyanka on her early days with iKheti. “But we soon realised that holding workshops was not enough.” People needed to carry their learning back from home and apply it, and Priyanka took a more holistic approach to overcome the obstacle. From seeds and organic manure to consulting and maintenance, iKheti expanded their scope. “It was an unorganised sector and professional help was lacking,” she says. “Our main focus was to become a one-stop shop.”

Supported by a network of volunteers and trained malis, iKheti hopes to introduce everyone to the joy of organic farming.

Promoting organic farming among urban dwellers

Priyanka insists on taking the no-chemical approach to farming, in tandem with her emphasis on healthy eating. From offering seeds and DIY kits on sale to offering consulting services on composting and kitchen gardening, she wants to train people in the art of growing their own food.

For time-strapped clients, iKheti offers an on-call mali (gardener) service. Finding this taskforce was one of her biggest challenges, Priyanka admits, as they were unfamiliar with the extra maintenance and organic methods. “Over time, they have become very caring. I foster animals, and sometimes when I am not around the nursery, they do it for me.”

“Our malis are specially trained to look after edible plants, and they are the backbone of this business,” she adds.

For beginners, Priyanka recommends growing herbs, which are easier and faster to grow. Herbs like curry leaves, ajwain, tulsi and pudina are very popular. “These might sound common, but 90 percent people who come to us don’t grow any of those plants,” she says. Herbs like celery, basil and oregano are also popular and Priyanka recommends growing these before one moves on to vegetable farming.

iKheti’s success has prompted Priyanka to take up new challenges: community farming, vertical gardening & hydroponics.

iKheti’s diverse undertakings, from innovative planters to grand vertical gardens

Having reached out to over 4,000 people via personal services and workshops, Priyanka is now emphasizing on encouraging bigger groups. iKheti’s experience with a few corporate and religious institutions has also shown that farming is best effectively practised on rooftops or bigger spaces. She also works with schools, encouraging children to eat healthy and understand the value of food.

Another area in which iKheti is beginning to work is with farmers around Mumbai, teaching them the values of organic farming. Admittedly, it is not easy—farmers worry about diminishing produce and Priyanka thinks it is a valid concern driven by the market and low awareness. “Many farmers don’t know that organic produce fetches higher prices,” she says.

The iKheti team not only educates farmers, but also teaches them the value of land as legacy. After all, a fertile land is a boon for the next generation.

Keeping space considerations in mind, iKheti is also venturing into vegetable growing in vertical spaces and taking tiny steps towards hydroponic systems. Their ultimate endeavour is to combine the two in an effort to offer greater convenience for urban farmers.

Priyanka aims to acquaint people from all works of life to the importance of a green environment. Not just farming, even smaller plants can make a difference. At the iKheti nursery, plants are reared to contribute to their surroundings, from purifying the air to attracting butterflies and insects. “We want to create a sustainable environment,” she says, encapsulating her ecopreneurial vision.

Check out the iKheti’s products and services online or get in touch with Priyanka here.

China Focus: Factory Farms The Future For Chinese Scientists

Factory Farms The Future For Chinese Scientists

Source: Xinhua| 2017-04-30 09:06:29|Editor: Yamei

XIAMEN, Fujian Province, April 30 (Xinhua) -- In a factory in eastern China, farming is becoming like scientific endeavor, with leafy vegetables embedded neatly on stacked layers, and workers in laboratory suits tending the plants in cleanrooms.

The factory, with an area of 10,000 square meters, is in Quanzhou, Fujian Province. Built in June 2016, the land is designed to be a "plant factory," where all environmental factors, including light, humidity, temperature and gases, can be controlled to produce quality vegetables.

The method is pursued by Sananbio, a joint venture between the Institute of Botany under the Chinese Academy of Sciences (IBCAS) and Sanan Group, a Chinese optoelectronics giant. The company is attempting to produce more crops in less space while minimizing environmental damage.

Sananbio said it would invest 7 billion yuan (about 1.02 billion U.S. dollars) to bring the new breed of agriculture to reality.

NEW FARMING

Plant factories, also known as a vertical farms, are part of a new global industry.

China now has about 80 plant factories, and Sananbio has touted its Quanzhou facility as the world's largest plant factory.

In the factory, leafy greens grow in six stacked layers with two lines of blue and red LED lights hung above each layer. The plants are grown using hydroponics, a method that uses mineral nutrient solutions in a water solvent instead of soil.

"Unlike traditional farming, we can control the duration of lighting and the component of mineral solutions to bring a higher yield," said Pei Kequan, a researcher with IBCAS and director of R&D in Sanabio. "The new method yields ten-times more crops per square meter than traditional farming."

From seedling to harvesting, vegetables in the farm usually take 35 days, about 10 days shorter than greenhouse plants.

To achieve a higher yield, scientists have developed an algorithm which automates the color and duration of light best for plant growth, as well as different mineral solutions suitable for different growth stages.

The plant factory produces 1.5 tonnes of vegetables every day, most of which are sold to supermarkets and restaurants in Quanzhou and nearby cities.

The world's population will bloat to 9.7 billion by 2050, when 70 percent of people will reside in urban areas, according to the World Health Organization.

Pei said he believes the plant factory can be part of a solution for potential future food crises.

In the factory, he has even brought vertical farming into a deserted shipping container.

"Even if we had to move underground someday, the plant factory could help ensure a steady supply of vegetables," he said.

HEALTHIER FUTURE

Before entering the factory, Sananbio staff have to go through strict cleanroom procedures: putting on face masks, gloves, boots, and overalls, taking air showers, and putting personal belongings through an ultraviolet sterilizer.

The company aims to prevent any external hazards that could threaten the plants, which receive no fertilizers or pesticides.

By adjusting the mineral solution, scientists are able to produce vegetables rich or low in certain nutrients.

The factory has already been churning out low-potassium lettuces, which are good for people with kidney problems.

Adding to the 20 types of leafy greens already grown in the factory, the scientists are experimenting on growing herbs used in traditional Chinese medicine and other healthcare products.

Zheng Yanhai, a researcher at Sananbio, studies anoectohilus formosanus, a rare herb in eastern China with many health benefits.

"In the plant factory, we can produce the plants with almost the same nutrients as wild anoectohilus," Zheng said. "We tested different light, humidity, temperature, gases and mineral solutions to form a perfect recipe for the plant."

The factory will start with rare herbs first and then focus on other health care products, Zheng said.

GROWING PAINS

Currently, most of the products in the plant factory are short-stemmed leafy greens.

"Work is in progress to bring more varieties to the factory," said Li Dongfang, an IBCAS researcher and Sananbio employee.

Some are concerned about the energy consumed with LED lights and air-conditioning.

"Currently, it takes about 10 kwh of electricity to produce one kilogram of vegetables," said Pei, who added that the number is expected to drop in three to five years, with higher LED luminous efficiency.

In a Yonghui superstore in neighboring Xiamen city, the vegetables from the plant factory have a specially designated area, and are sold at about a 30 percent premium, slightly higher than organic and locally produced food.

"Lettuce from the plant factory is a bit expensive, at least for now, there are many other healthy options," said Wang Yuefeng, a consumer browsing through the products, which are next to the counter for locally produced food.

Sananbio said it plans to expand the factory further to drive down the cost in the next six months. "The price will not be a problem in the future, with people's improving living standards," Li said.

Can Urban Farming Combat Food Waste? Chatting With The Founders of Alma Backyard Farms

Can Urban Farming Combat Food Waste? Chatting With The Founders of Alma Backyard Farms

Raised garden beds at Alma Backyard Farms. (Rebecca Yee)

By Noelle CarterContact Reporter

On Monday, volunteers and farm members will be collecting unharvested colorful leaves of Lacinato kale, Redbor kale, Bright Lights Swiss chard and purple cabbage at the Alma Backyard Farms at a local church and school location in Compton. The “gleaning party” is just part of the preparation for the first Los Angeles Feeding the 5000 event later in the week on May 4, culminating in a free feast made entirely from fresh produce and meant to highlight the global issue of food waste.

Alma Backyard Farms was started in 2013 by Richard D. Garcia and Erika L. Cuellar as a small, urban farm project. Inspired by the ideas and desires shared by juvenile offenders and prisoners, Garcia and Cuellar founded the farm as a means for these folks to transform their lives through farming. Through nature, members learn how to nurture, provide and give back to their communities — all while becoming self-sufficient. Recently I spoke with Cuellar and Garcia by phone as they tended their Compton garden location.

Where do you find the land to farm? Do you really farm in backyards?

Erika Cuellar: We started in backyards, but we’ve grown. We have a partnership with a transitional home in South L.A., and that particular home houses predominantly “lifers” — men who have served life sentences. We’ve basically transformed the outside of this home that houses 16 guys into an urban farm with a garden, chickens and about 20 fruit trees. It’s really about taking underutilized land and making it productive. We don’t farm acres of land; everything is urban, and they are small farms.

Our newest place, which is where we’re going to glean from for the Feeding the 5000 event, is in partnership with a school and church. They had a piece of land that was not utilized, and we transformed the space to grow food for people who are hungry.

What exactly is “gleaning”?

It’s harvesting. It’s collecting unharvested produce from the field.

Our focus is on reconnecting people through their food and to each other. Waste stems from a lack of connectedness.

— Richard D. Garcia, executive director and co-founder, Alma Backyard Farms

Can you talk a little about food waste from the farm standpoint? When it comes to waste, we’re not just talking about the food itself, but everything that went into it — the water, energy, effort and land.

Richard Garcia: My answer would have to be partly philosophical. The way we grow food is based on relationships. You understand the relationship between not just the plant and the soil — but the relationship between the plant and its caretaker. We approach farming by way of understanding interdependence, how we all have to contribute to one another’s well-being. From that perspective, wastefulness is a result of disconnect. It’s unfortunate — waste happens because we’ve somehow given ourselves permission to be disconnected from each other. We don’t have a relationship, or even knowledge, of the soil, or even the effort it takes for someone to pick the fruit you see at the grocery store. We’re more interested in the product itself than the whole of the experience.

What surprises your members most about the farming experience?

Garcia: I think because we work primarily with people who have been incarcerated, we’re hoping to restore a sense of agency. For someone who’s been locked up for a long time, there’s a sense of powerlessness because you hold no keys. From a lengthy experience like that to a setting such as an urban farm, suddenly you’re the caretaker. You have custody of plant life, and that’s a shifting of the paradigm. And, in a sense, nothing goes to waste. When folks are able to give back to the communities that they’ve taken from, they’re contributing.

I think when we instill a sense of resourcefulness, you don’t want to be wasteful, even with your time. The thing about food waste is it’s only symptomatic of how wasteful we can be in the larger context. We want to drive home to our members that they are of value and have purpose. I know that may not sound like it has to do with food, but it’s all related.

Your website mentions that you teach families and children how to grow and cook meals. How important is the relationship between growing and cooking?

Cuellar: It goes right to the issue of waste and wasting time. Knowing how to grow, where your food is grown and doing that together is so important. We see farming and growing food as a means to unify families. Being able to do that is key with the individuals we work with, and we encourage their parents and children, even grandparents when available, to join in.

With our own team and members, we break bread together every day we work together. Sharing a meal is one of the better things we do during the day. We emphasize meals that are healthier and introduce a more nutritional aspect.

You make sure none of the food goes to waste. What restaurants or organizations do you partner with?

Cuellar: With restaurants, we work primarily with chefs who are interested in carrying out seasonal menus. Restaurants are one facet, along with organizations such as L.A. Kitchen, that transform the food into hot meals for people who are hungry. At the transitional home, the food benefits the residents as well as the surrounding community. At our Compton site, it directly impacts the community here: the schoolchildren, parishioners and church community.

Garcia: We’re also developing more and more of our own compost, so nothing ever really goes to waste. As we grow, I’d love to see us take up more food waste from restaurants and convert it to compost.

You’re looking at the whole food chain, from planting the seeds to decomposition and turning that back into nutritional soil after it has lived its life.

From life to death and life again.

Chefs and scientists will discuss solutions for tackling the global problem of food waste at the Los Angeles Times Food Bowl, beginning May 1. For a full schedule of events, click here.

Hydroponic Farming Takes Root In CT

MAY 1, 2017 1 COMMENTS

Hydroponic Farming Takes Root In CT

PHOTO | STEVE JENSEN

Cheshire-based Maple Lane Farms II co-owners Allyn Brown (left) and Brant Smith inspect a foam float holding heads of hydroponically grown bibb lettuce nearly ready for market.

KAREN ALI

SPECIAL TO THE HARTFORD BUSINESS JOURNAL

Connecticut produces a mere 1 percent or so of the fruits and vegetables eaten by its residents.

That's a statistic state agricultural experts and producers want to change.

One way they are hoping to move the needle is through a type of controlled environment agriculture, called hydroponic farming, which is an eco-friendly way of growing produce in a soilless medium, with nutrients and water.

Hydroponic farming is gaining popularity in the state and nationwide, particularly in response to consumers' shift toward healthy eating and locally grown produce, rising food prices and extreme weather conditions making it harder for traditional farming.

Joe Geremia, known as the go-to guy for hydroponics in the state, said because Connecticut has a small amount of farmable acres, it makes sense to turn to hydroponic farming.

"It's nearly impossible [for Connecticut] to feed itself," said Geremia, who is a partner in Four Season Farm LLC, which will develop 10 acres of land in Suffield as a startup hydroponic farm. The farm, which the state has invested $3 million in, is expected to generate 40 jobs over the next two years and produce millions of pounds of tomatoes.

"It's a perfect thing for Connecticut. We can do more per acre, if we can do it indoors," said Geremia, who runs seven acres of greenhouses in Wallingford.

Geremia and others say more Connecticut farmers and greenhouse operators are adopting controlled environment agriculture.

"More people are embracing indoor technology in farming," Geremia said. "The trend is upward."

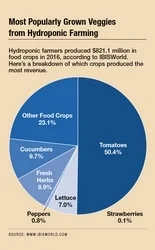

Hydroponic farming industry revenues, which reached $821.1 million nationwide in 2016, have grown at an annual rate of about 4.5 percent since 2011, according to research from IBISWorld.

PHOTO | STEVE JENSEN

Examples of the bibb lettuce produced by Maple Lane Farms. The lettuce is sold to grocery stores, including Stop & Shop, as well as wholesalers.

And of the 2,347 hydroponic farm businesses that existed in 2016, 3.8 percent operated in Connecticut, according to IBISWorld.

Four Season Farm LLC, which is expected to break ground this spring, plans to produce 5.75 million pounds of tomatoes the first year and 7.5 million pounds by the third year. The farm plans to add cucumbers, peppers and micro-greens.

In a February publication put out by the state Department of Agriculture, Commissioner Steven Reviczky said the Suffield project could lead the way to transforming Connecticut's greenhouse industry.

"Hydroponic and other types of indoor farming are becoming increasingly effective alternatives to traditional growing methods in many parts of the world," Reviczky said. "Connecticut has a well-established greenhouse industry that I believe could make the transition to growing food 12 months a year, and has the customer base to support it."

Win-win

Hydroponic farmer Allyn Brown, who has been producing lettuce on his Cheshire farm for three years, and on his Preston farm for six years, said there is a resurgence of indoor agriculture.

"It's a growing business in the northeast," Brown said. "We run 52 weeks a year. On an acre, you produce more indoors than out."

It's seen as a win-win for both consumer and farmer, farmers say.

Consumers — who are increasingly pushing for fresh vegetables and fruits year-round — gain by getting locally sourced fresh produce whenever they want it.

Hydroponic farmers winbecause instead of growing crops only four or five months of the year, they can be year-round producers, leading to new and more revenue opportunities.

"The reality is, if we are going to provide more local food when people want it, we have to figure out how to do it off-season," said Henry Talmage, executive director of the Connecticut Farm Bureau, and a vice chairman of the Governor's Council for Agricultural Development.

The Governor's Council, which was created in 2011, is looking to create a strategic plan for Connecticut agriculture, including looking at ways to increase by 5 percent the amount of consumer dollars spent on Connecticut-grown farm products over the next few years through 2020.

Talmage says while there are disadvantages to hydroponic farming, like high labor, energy and transportation costs, Connecticut does have several things going for it.

For one, Connecticut has a very robust greenhouse industry, which means that facilities already exist for hydroponic farming.

Connecticut is also in a "high-market corridor," between Boston and New York and near Philadelphia and Washington.

When dealing with perishable items, it's good to be closer to the markets you are supplying, Talmage said. "It's crazy when our food travels 1,500 miles to get to us. Connecticut is in a position to do this better than other New England states."

Brown, who owns Maple Lane Farms in Preston and Maple Lane Farms II in Cheshire, agreed that Connecticut is in a good geographic position for hydroponic farming.

His two farms produce 1.5 million heads of hydroponically grown bibb lettuce annually.

"It's got a great flavor," he said of the lettuce that is made without pesticides, is dirt free and stays fresh for a long period of time.

"Chefs really like to use the lettuce (which comes attached to the root ball) because it's so fresh and it is all usable," Brown said.

Maple Lane sells the product to grocery stores like Stop & Shop and LaBonne's as well as to wholesalers.

"They want it 12 months a year," Brown said, of the grocery stores.

The demand is a great thing for local farmers, and farmers hope the desire for local produce continues.

"You are supporting local agriculture as you purchase it," Brown said.

Carrefour Unveils Its Urban Agriculture Initiatives

04/27/2017

Carrefour Unveils Its Urban Agriculture Initiatives

For the official inauguration of the vegetable garden on the roof of the Villiers-en-Bière hypermarket in Seine-et-Marne, Carrefour is sharing its ideas for introducing short distribution channels at its stores.

Stores which are becoming production sites

Villiers-en-Bière vegetable garden: over a 1200 m² surface area, ornamental and aromatic fruit trees and fruit and vegetable plants are being grown, using methods inspired by agro-ecology. It is managed by students from the Bougainville de Brie-Comte-Robert agricultural and horticultural school. They also share information about the garden with neighbouring schools and customers at the store. The garden should begin to bear its first fruit in early May and its yield will be sold in the store.

Other vegetable gardens are set to be created all through France: in Mérignac, a 6000 m² in-ground garden is being created near the Carrefour store. In the Paris region, the Sainte-Geneviève des Bois hypermarket, the Charonne Carrefour Market and Carrefour’s Massy head office have all enlisted the services of start-up company Agripolis, which specialises in developing in situ gardens using the aeroponics process.

By signing the "Objectif 100 Hectares" charter, Carrefour is committing – alongside the Paris Town Hall – to planting throughout the capital, the aim being to convert 200 ha of Paris's built-up area into green spaces – a third of which will be for urban farming – between now and 2020.

Local supply contracts

Carrefour is also entering into local partnerships to sell products grown using agro-ecological farming techniques. In 2016, the retailer joined forces with the Ferme Akuo du Gâtinais located on a wind farm – the first farm to use permaculture in the Paris region – in order to supply local Carrefour Bio stores. Carrefour gives preference to short distribution channels by selling local products (some 60,000 products) and products made using agro-ecological methods – such as strawberries grown without synthetic pesticides.

With all of these varied projects in which it is involved, Carrefour is helping to ensure food of a high quality by selling ultra-fresh products from short distribution channels. By reducing the distances that these new products have to travel, the retailer is helping to preserve the planet's biodiversity and reducing CO2 emissions, while at the same time tackling food wastage.

The Startup That Will Change The Way China Feeds Its Cities

The Startup That Will Change The Way China Feeds Its Cities

Beijing-based startup Alesca Life is democratizing access to fresh food by creating solutions that enable anyone anywhere to grow the safest, healthiest, and freshest produce in the most efficient way possible. Their automated indoor food production system is currently growing nutrient-dense produce using no pesticides, no soil, no sunlight, 20-25 times less water, fertilizer, and land compared to traditional farming practices.

CEO Stuart Oda shares his thoughts on the necessity of evolving the modern agriculture framework to feed the globe’s ever-growing population.

What experiences inspired you to start this company?

I’ve traveled to over 40 countries and one of the most common challenges faced by emerging market countries was the access to highly nutritious, safe, fresh foods. The unpredictability of weather due to climate change and lack of access to critical resources and education makes food production and distribution and the stable supply of nutrition through fresh foods an enormous challenge.

Also, fresh food logistics is essentially the movement of water and nutrition in a perishable, damageable form: incredibly energy intense and wasteful with both food and packaging. Many of the problems of the agricultural supply chain can be overcome by removing the key variables of present day agriculture: weather, logistics, and land.

Finally, the environmental degradation associated with agriculture is quite alarming. When I was an investment banker in Tokyo, someone I greatly respected always reused printouts until the white on the paper was almost gone. Her explanation was simple, “I don’t want my grandchildren to have to visit a museum to see what a tree looks like.”

Agriculture must become a more environmentally friendly practice to ensure that future generations do not inherit a heavily polluted planet. Alesca Life was born out of the frustration of an archaic method of food production to create a more sustainable alternative to feed our current and future population.

Why solve the issues you’re trying to solve?

The world will face a number of significant challenges in the coming decades, including rapid population growth and urbanization, higher food distribution inequality and waste, environmental degradation, and natural resource depletion. In developing countries, there is the additional problem of poor food quality and safety.

Also, as the sharing economy and automation grows, the most basic of urban infrastructure and human capital will become idle or underutilized. A solution to these challenges will be critical for global social, economic, and environmental development.

Why is your solution unique?

Alesca Life designs and builds turn-key farming solutions that enable anyone in any environment to produce safe and healthy produce locally. We have several hardware form factors that enable pesticide-free food production at any scale, and we coupled it with a cloud-based operational management system that enables complete production data transparency and supply chain traceability.

The agricultural industry has traditionally been additive: more chemicals, more water, more logistics, more land. Alesca Life’s philosophy is the exact opposite: food production utilizing minimal inputs on virtually no land.

Also, our solution is looking to integrate an IT infrastructure that allows for supply chain transparency to end the production of “anonymous food” and by growing in a more consistent environment we want to end the concept of “ugly vegetables” which are some of the biggest contributors to poor food quality and high food waste.

What has been your company’s proudest moment been to date?

For the founders, completing our hand-built shipping container farm and commencing fresh vegetable production was a moment of incredible pride.

For the team, installing our first indoor food production system into Swire Hotels for the onsite production of fresh wheatgrass was one of our collective highlights.

My personal proudest moment was when, following a visit to our urban container farm, a young child told us that he wanted to be an urban farmer when he grew up.

What do you hope the world will look like as a result of your work?

Our team hopes that the integration of food production as one of the core functions of urban environments will help to create more resilient, sustainable, and beautiful cities for urban citizens. Also, if the extension of our technology can impact food production in space (outer space), it would be an incredibly exciting future.

Upping The Ante For Urban Growing

Upping The Ante For Urban Growing

4 May 2017, by Gavin McEwan, Be the first to comment

Europe is starting to catch up with the Far East and the USA with the opening of a major indoor lettuce-growing facility in the Netherlands, Gavin McEwan reports.

Lettuce: plants at Staay Food Group’s new facility in the Netherlands will be grown hydroponically in coir underneath LEDs - image: HW

With the imminent opening in the Netherlands of Staay Food Group’s €8m, 27,000sq m high-rise indoor lettuce-growing plant, Europe finally appears to be following the Far East and the United States down the route of large-scale commercial urban growing.

Located at its Fresh-Care Convenience processing plant in Dronten, central Netherlands, the facility will initially produce around 300,000kg of lettuce, a mixture of Lollo Biondo, Lollo Rosso, Rucola and Frisée forms, rising eventually to more than a one-million kilograms, for processing into salads.

The plants will be grown hydroponically on eight or nine levels in coir plugs underneath LEDs. "At this moment, we still source our lettuce in southern Europe during part of the year. The disadvantages are that the climate is erratic and the transport distances are great," says the company.

"Once the vertical farm supplies the lettuce, it will be fresher, there won’t be any pesticides involved, the quality will be stable, we will be able to plan production better and we will contribute to Staay Group’s sustainability goals."

Production times will also be considerably shorter than in conventional growing, it adds. Last year, in partnership with Philips Lighting and breeder Rijk Zwaan, it tested the format at Philips’ High Tech Campus in Eindhoven, with "positive results".

While the UK has yet to see anything on this scale, the wide exposure of a handful of pioneer projects on television and in national newspapers has brought the format to wider public attention. But suppliers tend not to think in purely national terms, according to Stephen Fry, senior business development executive at Midlands hydroponics equipment supplier HydroGarden.

"We have had a significant increase in business for our urban growing solutions," he says. "Most weeks I am drawing up plans for new systems, which could be in Lebanon, Kenya, New Zealand or the Far East as well as mainland Europe. People are looking at producing food where it’s required. For the UK, what is the carbon footprint of driving produce up from Spain?"

Responding to trends

"It’s still very niche," Fry admits. "We aren’t going to save the planet from starvation on our own, but a 50% increase in world food production has to come from somewhere. What we are doing is responding to trends in food. You only have to go to a half-decent restaurant or even pub to see the emphasis on freshness."

The VydroFarm tiered indoor growing system developed by HydroGarden took the innovation prize in the Future Manufacturing Awards presented by EEF, formerly the Engineering Employers Federation, earlier this year. Now rebranded as V-Farm, the system currently leads the company’s push into world markets.

It is also launching a new flood-and-drain vertical system at international trade events this month, says Fry.

On a smaller scale it has also developed a compact format for coffee shops, small supermarkets and high-end restaurants to grow their own micro-leaves and other crops. Its own range of LEDs "are giving very good results — they have needed to have a different spectrum for micro-greens, which are popular in the Far East", Fry explains.

"We also do a lot of work on the nutritional element. With our new product lines we can affect the nutritional content of things like micro-greens. Kale is hailed as a superfood but, if you compare the vitamin and mineral content, these are super-duper foods."

HydroGarden has also installed a trial 12-rack growing room at its Coventry headquarters, while a specially commissioned hybrid version of V-Farm combined with a FishPlant aquaponics system is also due to open at Pershore College in Worcestershire later this month.

This will be used to educate post-16 and degree-level students on a variety of courses including horticulture and animal care about hydroponics and aquaponics as sustainable alternatives to traditional farming methods.

HydroGarden’s V-Farm unit combined with FishPlant aquaponics system

Water quality and health

The college’s project manager John King explains: "In the first instance, our animal-care students will carry out testing to monitor and manage the water quality and subsequent health of the fish and plants.

These readings will be shared with our horticulture students whose focus will be the produce, grown from seed in separate propagators before being transplanted into the hydroponics part.

"If the plants are less than healthy, the students will have a real-life scenario to determine what is going wrong and what factors need to be altered such as lighting, nutrient flow and temperature." Animal-care students will then feed the finished produce to rabbits and other small herbivores in the department.

"We also plan to invest in a larger vertical-farming unit in the future so any students who are particularly interested in hydroponics will be able to take their knowledge and learning to the next level by working on a larger scale," says King.

Fry adds: "We are working with Pershore on growing protocols. Having a system without protocols on how to use it is like giving a car to someone who can’t drive."

The understanding of plants’ response to LEDs in controlled growing environments has so far been driven in the UK by AHDB Horticulture-funded work at Stockbridge Technology Centre’s LED4Crops facility. But while this three-year programme finishes at the end of this month, there is still much more in this area that the North Yorkshire research station is keen to investigate.

The facility’s manager, photobiologist Dr Phillip Davis, says: "We have a lot of data on the effect of different light on crops. We can control everything from how tall the plant grows to when it flowers. We have looked a lot of different crops — lettuce, tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers and many ornamentals — mainly from the point of view of propagation, but for lettuce and leafy herbs through to harvest. For

a crop like basil you can control the intensity of the flavour, for example, whether you want it mild for salads or stronger for sauces."

This response is already being harnessed by salad and herb grower Vitacress, which has recently installed Heliospectra programmable LED grow lights at its West Sussex site to increase shelf life and chill tolerance of basil plants during the final growth stage.

"There isn’t a vast acreage of indoor farming in the UK yet, though there are rumblings of big things taking off," Davis notes.

"And in research we are really just touching the surface. The more we look at it in total, the more we discover is possible in things like flavour and shelf life."

Urban growing economics

While the LED4Crops facility continues with research including private commissions, Stockbridge Technology Centre is now taking on a new project to look specifically at the economics of urban growing, and hence the barriers to commercial uptake, as part of the Innovate UK-funded Centre for Crop Health & Protection.

"There are a lot of questions in people’s minds as to whether it makes economic sense," says Davis. "It’s certainly not a low bar to start with." The new facility will have three growing areas, each producing "large volumes" of a single crop "and will be flexible enough to allow us to test what’s out there.".

He continues: "LED lighting is coming down in price — though not as quickly as some had hoped. But they are getting more efficient so you need fewer and your payback is quicker."

Viewpoint: Professor Tim Benton

"Urban agriculture, including vertical farming, is a potentially useful way to provide some high-value produce locally, and helps to connect people and food. However, it is unlikely it will underpin food security in the sense of access to a healthy diet as the amount of land necessary to provide nutritional needs is likely to be difficult to find within a purely urban setting.

"There is a clear role for it in some circumstances and for some markets, perhaps most obviously for things like lettuce, herbs and some fruit and veg. The degree to which it may emerge depends on a host of factors like access to food from other places, local access to land and water, infrastructure and so on.

"The space in most cities is very expensive relative to peri-urban and rural areas, so it might be more likely to emerge strongly in very large cities where ‘local fresh’ food might be highly valued, and where there is a market to support it, or in cities like Singapore, where access to land is absolutely difficult. Where land is cheap and available near cities, and it is easy for fresh produce to find its way into the centre, it may not play a huge role."

Number of U.S. Indoor Warehouse Farms On The Rise

Number of U.S. Indoor Warehouse Farms On The Rise

The number of urban, indoor and warehouse agricultural operations in the U.S. has grown significantly over the last two years. According to a new white paper that was presented on the first day of the 5th Indoor Ag-Con in Las Vegas this Wednesday, there are currently 56 warehouse farms, plant factories and rooftop greenhouses across the US, compared to only 15 in a previous report of March 2015.

This growth was also reflected in the atmosphere of the first day of the 5th annual Indoor Ag-Con that is being held this week on Wednesday and Thursday at the Las Vegas Convention Centre. While not very crowded, the event has grown this year and brings together the industry's best suppliers, researchers, growers, investors and other professionals from the food industry.

And while it remains a cliché to say that this industry is still young, it is growing up fast and is clearly looking more at the overall business management side of growing indoors. Therefore the first day of the event covered a number of business related topics such as real estate development, planning, management and funding. As well as this, several expert speakers shared their vision on how automation and crop selection can increase the efficiency of indoor farming and make businesses profitable.

While the first day also covered a few technical topics, the speaker program on the second day will provide more emphasis into technical aspects of indoor growing.

We will be back with more reports on the event and the presentations over the coming days. On Monday we will publish a complete photo report of the conference and exhibition.

The white paper will be available for download shortly.

Publication date: 5/4/2017

Author: Boy de Nijs

Copyright: www.hortidaily.com

Vertical Farms to Shape Future Agriculture Supply Chains

Vertical Farms to Shape Future Agriculture Supply Chains

- New Straits Times

- 3 May 2017

- The writer is founder and CEO of LBB International, the logistics consulting and research firm that specialises in agri-food supply chains, industrial logistics and third-party logistics. LBB provides logistics diagnostics, supply chain design and solutio

BY 2040 the world will have nine billion inhabitants, of which the majority of which will live in cities. With a growing population and high urbanisation figures many countries, including Malaysia, have become highly dependent on imports for basic agriculture commodities.

This has created very long agriculture supply chains, with the agriculture produce section in our supermarkets today featuring food from all over the world!

As agriculture produce is living matter, the moment it is harvested or slaughtered it becomes a highly sensitive product that requires a specific environment, handling and has limited shelflife.

Long agriculture supply chains, therefore, means higher risks of diseases, reduction of quality, higher wastage, and high logistics costs.

Food miles, the distance food needs to travel to the point of consumer purchase, have exploded over the past 25 years.

Research shows that systematic long food miles are not sustainable.

High dependence on imports comes with high risks for countries, as food prices become highly dependent on the availability of excess of agriculture produce by agriculture exporters.

Is there a way back to where we have shorter supply chains for our basic fresh produce?

To significantly increase local production of basic agriculture commodities in Malaysia, there are two solutions: agriculture food parks and integrating farming in urban environments.

Agriculture food parks produce agriculture products in bulk and are located in rural areas.

These parks are also involved in processing, ranging from washing, cutting, packing up to advanced food processing into ready meals and ultra-processed foods.

These agriculture food parks then transport these products by truck to retail outlets and restaurants.

However, as land becomes more scarce, the necessary land is often not available for this kind of bulk agriculture production. Therefore, the integration of farming in urban environments becomes a necessity in order to feed our growing population in combination with high urbanisation.

The Netherlands has more than 100 years of experience in indoor farming, and is today the example of producing agriculture products in situations where land is scarce or not suitable for farming due to climate conditions.

All over the world, countries are looking at initiatives in vertical farming.

Vertical farms are high-rise multi-functional buildings producing food in a vertical system. This can be integrated in an office building, flat, or condominium.

These buildings need to plan the necessary water, energy, and nutrient requirements needed to farm. Water can come from rainfall.

Energy can be supplied from solar energy and by making use of specialised light-emitting diode lights, where vegetables, herbs and soft fruits can be produced in climate chambers, through environmentally friendly closed systems.

These farms can be even be integrated with fish farming.

Nutrients can be gathered from used coffee grounds from coffee shops and waste from restaurants, supermarkets, and households.

Vertical farming reduces the agriculture supply chain distances dramatically, bringing down transportation costs.

However, this requires food production to be integrated in city planning.

City planners will need to force real estate developers to integrate farming in buildings.

Food sovereignty, safety, security and sustainability can thus be solved by the introduction of vertical farming.

Vertical farms dramatically reduce agriculture supply chains, cutting transportation costs and enhancing freshness.

This allows countries to restore the ecological balance in the urban jungle.

Lufa Farms Rooftop Greenhouses Trending In Montreal

Lufa Farms Rooftop Greenhouses Trending In Montreal

Danny Kucharsky | Property Biz Canada | 2017-04-25

One of Lufa Farms’ three rooftop greenhouse facilities in Montreal. (Photo courtesy Lufa Farms)

When the founders of Montreal urban agricultural pioneer Lufa Farms first approached building owners about renting their roofs to help the company establish a rooftop farm, “everybody thought they were crazy,” recalls public relations and communications manager Simon Garneau.

Fortunately, one building owner said yes. So, in 2011 Lufa Farms opened in Montreal what the company says was the world’s first commercial rooftop greenhouse.

Lufa, which operates under the slogan “Our vision is a city of rooftop farms,” recently opened its third and largest hydroponic rooftop greenhouse in the city. The 63,000-square-foot facility on top of an empty warehouse in the borough of Anjou produces more than 40 varieties of vegetables.

“The business model is that we rent the roofs,” says Garneau.

The model benefits everyone because even though the roof is rented for less than interior space, building owners get money from a place they would normally not be able to generate revenue.

In addition, the rooftop greenhouse reduces owners’ heating and cooling costs because it acts as a pad between the heat and cold outside, he says.

Combined, the Lufa Farms facilities have 137,000 square feet of growing space and grow about 75 varieties of fresh vegetables.

10,000 Produce Baskets Per Week

Lufa delivers more than 10,000 baskets a week of produce to Montreal-area residents. The greenhouses give residents access to local produce that would otherwise need to be imported from thousands of miles, particularly outside the summer months.

The newest facility – the most automated yet – specializes in leafy greens and produces more than 40 varieties of lettuce, collard greens, kale, radish, broccoli, cauliflower and celery. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau toured the facility in late March.

It was developed with $3 million in debt financing from the union capital development fund Fonds de solidarité FTQ and $500,000 in support from La Financière agricole du Québec. The Quebec government fund supports sustainability in agriculture.

It was designed by Dutch greenhouse innovators Kubo and outfitted by Belgian greenhouse automation experts Hortiplan.

The Anjou “farm” is joined by the original 32,000-square-foot facility, in Montreal’s Ahuntsic neighbourhood, which specializes in cucumbers, bell peppers, hot peppers, herbs and micro-greens. A second 42,000-square-foot facility that opened in Laval in 2013 specializes in tomatoes and eggplants.

Searched Via Google Maps

When founders Mohamed Hage and Lauren Rathmell first set out to find space for a greenhouse, they used Google Maps to search for suitable Montreal buildings with flat surfaces and very little rooftop equipment, Garneau says.

At the time, Montreal had no rules for rooftop greenhouses. But after negotiations, the city decided to consider rooftop greenhouses as an extra floor on the building. Lufa now has to meet bylaws for everything from emergency escapes to fireproofing.

“The success of the first greenhouse made things simpler, because the city has now adjusted to the model. There are less hurdles when we want to build on the roof,” Garneau says.

Garneau says now that Lufa Farms is a proven and growing concern, it’s been easier to find space for rooftop rentals.

“It doesn’t sound as crazy to people; it actually makes sense to them now. Why go out of town to grow vegetables when you can use a wasted space that just creates extra heart islands in the city and why make your vegetables travel when they can be near you?”

Partnership With Farmers, Producers

Subscribers to Lufa pay a minimum weekly price of $15 for produce baskets, which can be customized to include products from more than 200 partner farmers, food artisans and local producers.

“Because we’re hydroponic, we can’t grow root vegetables like potatoes, beets and carrots, so we deal with local organic producers who are in most cases too small to sell to large-scale grocery stores,” he says.

The baskets are delivered to more than 350 pick-up points in the Montreal area, from yoga studios to libraries and daycare centres. For an extra $5 weekly, subscribers can have their baskets delivered to their homes by Lufa’s fleet of electric cars.

Lufa Farms plans to continue the expansion of its urban farm projects in Quebec and in New England.

Shanghai's 100-Hectare Vertical Farm to Feed 24 Million

Shanghai's 100-Hectare Vertical Farm to Feed 24 Million

More Urban dDevelopment Plans

By Flora Burles | Tue, May 2, 2017 02:47 PM

Plans have just been unveiled by international architecture firm Sasaaki for a spectacular 100-hectare urban farm growing fruit and vegetables in Shangahai.

News comes to us from Inhabitat that a new 250-acre farming district, “Sunqiao Shanghai”,set amidst the skyscrapers of the city, will meet the food needs of almost 24 million people using both hydroponic and aquaponics farming systems.

The farm also will also serve as a center for innovation, interaction and education within the world of urban agriculture, as visitors will be able to tour the interactive greenhouses, a science museum and an aquaponics system. There will even be family-friendly events to educate children about modern agricultural techniques and sustainability.

Given its urban setting, the Sunqiao Urban Agricultural District’s layout will have to utilise vertical space as efficiently as possible, so will include multiple growing platforms such as algae farms, floating greenhouses, vertical walls and seed libraries. Some of the crops will even be grown indoors, under LEDs and in nutrient-rich water. The farms will primarily grow leafy greens, like kale, bok choi, and spinach, which will be sold to restaurants, grocers, or be exported.

It is part of a larger plan to turn part of the city into an ag-tech hub, according to Michael Grove, a principal at Sasaki. Grove estimates that building work on the project will commence by 2018.

“As cities continue to expand, we must continue to challenge the dichotomy between what is urban and what is rural. Sunqiao seeks to prove that you can have your kale and eat it too.”

Opportunities For Growth Abound

Opportunities For Growth Abound

Rice University students learn science basics by contributing to a startup urban farm

Video produced by Brandon Martin/Rice University

HOUSTON – (May 2, 2017) – Freshmen in two Rice University classrooms teamed up this spring to make a joyful contribution to Recipe for Success' Hope Farms in Houston and learn basic scientific method along the way.

Learning literally from the ground up, the students developed their analysis of soil from fields at the urban farm, which was founded to bring nutrition to a food desert in the south part of the city.

At the start of the semester, lecturers Sandra Bishnoi and Michelle Gilbertson, both part of Rice's Wiess School of Natural Sciences, brought students to collect samples from the farm a few miles south of campus. Back then, the 7-acre site and former location of a Houston high school was still bare.

The students were pleased to return in April to see nearly an acre bursting with lettuce, tomatoes, carrots and other produce, some ready for harvest. The fruits -- and vegetables -- of their studies will help as the farm plows and plants new fields in the coming seasons.

"I'm a pre-med student and I came into this class expecting to do research, but not on this subject," Raymond Tjhia said while visiting the farm in April. "It's a really neat experience. At Rice, you can get your hands dirty and do something that helps the community while also gaining skills that will help you in any field."

"We really lucked out in finding a connection with Rice," said Hope Farms manager Amy Scott, who met Bishnoi and Gilbertson through Caroline Masiello, a Rice professor of Earth science and chemistry. "We discovered we had a lot of common purposes, that the professors were looking for opportunities for their students to have a real-life application of their skills and we were looking to learn a lot about our soil, since it is a wild card in a lot of ways."

Scott said the students' most surprising discovery revealed differences in soil acidity from field to field. "I wasn't that aware of how much the pHwas fluctuating in our fields," she said. "We ended up having a pretty broad range. That, I found out, could have been affected by our well water, which is much more acidic than we realized."

Acidity was only one aspect of the study. Gilbertson's chemistry class also analyzed the soil's salinity, conductivity, ion exchange and asphalt contamination, noting at a presentation for farm officials that material left over from razed structures had not hurt the soil. "But where the school building sat on the soil, we're finding low carbon mass," she said. "That's because nothing has grown on it and died and put carbon back into the soil."

Bishnoi's biology class tested for acidity and also designed experiments to study soil microbiology, phosphorus deficiency and water retention. "We have teams using an organism called Daphnia magna, a model of toxicity for effluents in water being drained off an area," she said. "Another team is looking at good and bad microbes in the soil to see how can we modify the microbiology to improve cultivation."

The students planted seeds in soil samples from the farm alongside seeds in potting soil. "They compared the yield from spinach and green beans, crops we knew would grow quickly," Bishnoi said. "We've gotten some nice leaf growth and germination." However, they discovered that soil from raised beds at the farm only allowed seeds to germinate and not grow into edibles.