Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Philips Lighting Begins Largest LED Horticultural Lighting Project in The World

Philips Lighting Begins Largest LED Horticultural Lighting Project in The World

June 14, 2017

- LED grow lights will illuminate greenhouses occupying an area the size of 40 soccer pitches

- Project indicative of trend for large-scale horticultural LED lighting projects supporting domestically grown produce

Eindhoven, the Netherlands – Philips Lighting (Euronext Amsterdam ticker: LIGHT), a global leader in lighting, today announced that it will provide LLC Agro-Invest, Russia’s most innovative greenhouse produce company, with LED grow lights to support cultivation of tomatoes and cucumbers in greenhouses covering an area of more than 25 hectares (equivalent in size to about 40 soccer pitches). The project, which is the largest LED horticultural lighting project ever undertaken, will enable year-round growing, help boost yields - especially in the winter - and will save 50 percent on energy costs compared to conventional high-pressure sodium lighting. The project also underlines a global trend for large-scale LED horticultural lighting implementations that can support demand for locally grown produce.

Philips Lighting is working with Dutch partner Agrolux and Russian installer, LLC ST Solutions, which will equip greenhouses in Lyudinovo, Kaluga Oblast, 350 km south west of Moscow, during the next three months. Philips Lighting will provide ‘light recipes’ optimized for growing tomatoes and cucumbers, training services and 65,000 1.25m long Philips GreenPower LED toplights and 57,000 2.5m long Philips GreenPower LED interlights. Laid end to end, they would stretch 223 km, the equivalent of crossing the English Channel from Dover to Calais more than five times.

“We have a reputation for innovation on a large scale and LED grow lights are definitely the future. They deliver the right light for the plant, exactly when and where the plant needs it the most, while radiating far less heat than conventional lighting. This allows us to place them closer to the plants,” said Irina Meshkova, Deputy CEO and General Director, Agro-Invest. “Thanks to this technology we will be able to increase yields in the darker months of the year, and significantly reduce our energy usage,” she added.

“This LED horticultural project is the largest in the world. It will reduce the electricity consumed to light the crop by up to 50 percent compared with conventional horticultural lighting and uses light recipes designed to boost quality and crop yields by up to 30 percent in the dark period of the winter,” said Udo van Slooten, business leader for Philips Lighting’s horticultural lighting business. “Our grow lights are the perfect supplement to natural daylight so that crops can be grown efficiently throughout the year. The project also highlights a growing international trend to replace imports with domestically grown produce, reducing food miles and ensuring freshness,” he added.

About Agro-Invest

LLC Agro-Invest is Russia’s most innovative greenhouse produce company. Its 43 hectare modern greenhouse complex grows more than 15 varieties of vegetables with an annual production capacity of 25,000 tons. The company acts ecologically, collecting rainwater to water the plants which are pollinated by bees from special beehives within the greenhouse complex. The latter helps improve harvests by 20-25 percent. Protection of the plants is undertaken by natural biological methods. Since 2016, Agro-Invest has sold and marketed its produce under the “Moyo Leto.” trademark. The company works with all the federal trade networks in the Russian Federation and is expanding its operations.

About Agrolux

Agrolux is a worldwide supplier of assimilation lighting for horticulture. It is the biggest dealer in Philips LED horticultural lighting worldwide. It distinguishes itself based on advice, service and quality. It also produces its own luminaires and exports them to clients worldwide. The company’s broad knowledge, extensive experience and innovative technology, make it stand out as a leader in the horticulture sector. It combines good, honest advice with the fast and dependable delivery of lighting luminaires and parts. Established in 2002, Agrolux has grown in size and production numbers annually. Its employees come from diverse sectors within horticulture and offer a wealth of practical experience, providing the best advice and most efficient lighting for horticulture.

For more information on Philips horticultural lighting: www.philips.com/horti

For further information, please contact:

Philips Lighting, Global Media Relations

Neil Pattie | Tel: +31 6 15 08 48 17 | Email: neil.pattie@philips.com

Philips Lighting Horticulture LED Solutions

Daniela Damoiseaux | Tel: +31 6 31 65 29 69 | Email: daniela.damoiseaux@philips.com

About Philips Lighting

Philips Lighting (Euronext Amsterdam ticker: LIGHT), a global leader in lighting products, systems and services, delivers innovations that unlock business value, providing rich user experiences that help improve lives. Serving professional and consumer markets, we lead the industry in leveraging the Internet of Things to transform homes, buildings and urban spaces. With 2016 sales of EUR 7.1 billion, we have approximately 34,000 employees in over 70 countries. News from Philips Lighting is located at http://www.newsroom.lighting.philips.com and on Twitter via @Lighting_Press.

The Future of Farming May Not Involve Dirt or Sun

Farming uses copious amounts of water--70 percent of all freshwater consumed is used for agriculture, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, only about half of which can be recycled after using. It also requires huge swaths of land and, of course, just the right amount of sun. AeroFarms thinks it has a better solution.

AeroFarms co-founders Marc Oshima (left) and David Rosenberg.CREDIT: Ellise Verheyen

The Future of Farming May Not Involve Dirt or Sun

New Jersey-based AeroFarms proposes a radical and more sustainable way to grow the world's food.

By Kevin J. Ryan Staff writer, Inc.@wheresKR

COMPANY PROFILE

COMPANY: AeroFarms

HEADQUARTERS: Newark, NJ

CO-FOUNDERS Marc Oshima, David Rosenberg, Ed Harwood

YEAR FOUNDED: 2011

MONEY RAISED: More than $100 million

EMPLOYEES: 120

TWITTER: @AeroFarms

WEBSITE: aerofarms.com

Farming uses copious amounts of water--70 percent of all freshwater consumed is used for agriculture, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, only about half of which can be recycled after using. It also requires huge swaths of land and, of course, just the right amount of sun.

AeroFarms thinks it has a better solution. The company's farming method requires no soil, no sunlight, and very little water. It all takes place indoors, often in an old warehouse, meaning in theory that any location could become a fertile growing ground despite its climate.

The startup is the brainchild of Ed Harwood, a professor at Cornell University's agriculture school. In 2003, Harwood invented a new system for growing plants in a cloth material he created. There's no dirt necessary--beneath the cloth, the plants' roots are sprayed with nutrient-rich mist. Harwood received a patent for his invention and founded Aero Farm Systems, so named because "aeroponics" refers to the method of growing plants without placing them in soil or water. The company, which sold plant-growing systems, was mostly a side project for Harwood and didn't generate much revenue.

AeroFarms uses LED lighting to create a light recipe for each plant.CREDIT: Ellise Verheyen

In 2011, David Rosenberg, founder of waterproof concrete company Hycrete, and Marc Oshima, a longtime marketer in the food and restaurant industries, looked at the inefficiency of traditional farming and sensed an opportunity. The pair began exploring potential new methods and, in the process, came across Aero Farm Systems. They liked what Harwood had developed--so much that they offered him a cash infusion in exchange for letting them come on board as co-founders. They also proposed a change in business model: Rosenberg and Oshima saw a bigger opportunity in optimizing the growing process and selling the crops themselves.

Harwood agreed. The company became AeroFarms, with the three serving as co-founders. The trio bought old facilities in New Jersey--a steel mill, a club, a paintball center--and started converting them into indoor farms.

Today, each of the startup's farms features vertically stacked trays where the company grows carrots, cucumbers, potatoes, and, its main product high-end baby greens, which it sells to grocers on the East Coast including Whole Foods, ShopRite, and Fresh Direct, as well as to dining halls at businesses like Goldman Sachs and The New York Times. By growing locally year-round, the company hopes it will be able to provide fresher produce at a lower price point, since transportation will be kept to a minimum. (Currently, about 90 percent of the leafy greens consumed in the U.S. between November and March come from the Southwest, according to Bloomberg.) AeroFarms collects hundreds of thousands of data points at each of its facilities, which allows it to easily alter its LED lighting to control for taste, texture, color, and nutrition, Oshima says. The data also helps the company adjust variables like temperature and humidity to optimize its crop yields.

The result, according to AeroFarms, is wild efficiency: The growing method is 130 times more productive per square foot annually than a field farm, from a crop-yield perspective. An AeroFarm uses 95 percent less water than a field farm, 40 percent less fertilizer than traditional farming, and no pesticides. Crops that usually take 30 to 45 days to grow, like the leafy gourmet greens that make up most of the company's output, take as little as 12. Oshima claims that its newest farm, which opened in Newark in May, will be the world's most productive indoor farm by output once it reaches full capacity. Currently, AeroFarms' greens retail for around the same price as similar gourmet baby greens.

AeroFarms employee Samentha Evans-Toor checks the plant growth in a Newark, New Jersey, facility. CREDIT: Alex Kwok

"Most farms don't have a chief technology officer," Oshima says. "We have a dedicated R&D center, plant scientists, microbiologists, mechanical engineers, electrical engineers. We've done our due diligence to create this."

To be sure, as innovative as AeroFarms might be, it's not exactly a practical solution for replacing the world's farms. One big problem is that indoor farming requires huge amounts of electricity, which is not only costly but also offsets much of the good done by preserving water because of the large carbon footprint it creates. AeroFarms acknowledges the drawback but says that it's working to address the problem. The company hired Roger Buelow, the former chief technology officer of LED lighting company Energy Focus, who helped design AeroFarms' customized LED lighting system. "That allows us to be much more energy efficient than anything else out there," Oshima says.

Another challenge AeroFarms faces as it tries to grow is simply scaling the necessary expertise to run these farms. Dickson Despommier, a microbiologist and professor emeritus at Columbia University, first started experimenting with vertical farming--a term that he's widely credited with coining--in 2000. Despommier says that successfully running a vertical farm requires extensive agricultural and process knowledge, which in the case of AeroFarms is provided primarily by Harwood. "Some people think you can just read a book and find out how to do this," Despommier says. "You can't."

That steep learning curve, he says, can create obstacles for companies in this industry. "The biggest issue is finding people who are qualified," he says. "Growers in particular are very hard to find. Who's training them? The answer is, very few places." In the U.S., the University of Arizona, University of California, Davis, and the University of Michigan are among the few institutions that offer courses in vertical farming.

At AeroFarms, that issue is magnified thanks to Harwood's patented growing medium. "No one has direct experience with this," Oshima says. Once the startup finds candidates it trusts to learn the growing process, it has to train them and teach them the company's more than 100 best operating procedures.

AeroFarms' finished product "Dream Greens."CREDIT: Alex Kwok

The company employs 120 people. It has raised more than $100 million to date, from firms including Goldman Sachs and GSR Ventures. Other companies, like Michigan-based Green Spirit Farms and California-based Urban Produce, also sell to consumers using vertical farming methods, though The New Yorker reported in January that AeroFarms had twice the funding of any other indoor farming company--even before its recent $34 million round.

AeroFarms sees its growing method as especially useful in areas where the climate might not be friendly to growing, or where water or land is sparse. The startup currently has nine farms, including locations in Saudi Arabia and China. It plans to reach 25 farms within five years.

"From day one," Oshima says, "this has been about having an impact around the world."

PUBLISHED ON: JUNE 14, 2017

USDA Announces Grants Designed to Increase Amount of Local Food Served in Schools

USDA Announces Grants Designed to Increase Amount of Local Food Served in Schools

June 13, 2017 | seedstock

News Release: WASHINGTON – The U.S. Department of Agriculture today announced the projects selected to receive the USDA’s annual farm to school grants designed to increase the amount of local foods served in schools. Sixty-five projects were chosen nationwide.

“Increasing the amount of local foods in America’s schools is a win-win for everyone,” said Cindy Long, Deputy Administrator for Child Nutrition Programs at USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service, which administers the Department’s school meals programs. “Farm to school projects foster healthy eating habits among America’s school-age children, and local economies are nourished, as well, when schools buy the food they provide from local producers.”

According to the 2015 USDA Farm to School Census, schools with strong farm to school programs report higher school meal participation, reduced food waste, and increased willingness of the students to try new foods, such as fruits and vegetables. In addition, in school year 2013-2014 alone, schools purchased more than $789 million in local food from farmers, ranchers, fishermen, and food processors and manufacturers. Nearly half (47 percent) of these districts plan to purchase even more local foods in future school years.

Grants range from $14,500 to $100,000, awarding a total of $5 million to schools, state agencies, tribal groups, and nonprofit organizations for farm to school planning, implementation, or training. Projects selected are located in urban, suburban and rural areas in 42 states and Puerto Rico, and they are estimated to serve more than 5,500 schools and 2 million students.

This money will support a wide range of activities from training, planning, and developing partnerships to creating new menu items, establishing supply chains for local foods, offering taste tests to children, buying equipment, planting school gardens and organizing field trips to agricultural operations, Long said. State and local agency interest and engagement in community food systems is growing. Having received 44 applications from state or local agencies, 17 state agencies will receive funding.

Grantees include the Nebraska Department of Education, which will refine and expand the “Nebraska Thursdays” program, which will focus on increasing locally sourced meals throughout Nebraska schools, and the Virginia Department of Education, which will focus on network building to ensure stakeholders from all different sectors are leveraged. Both the South Dakota Department of Education and the Arkansas Agriculture Department will use training grants to build capacity and knowledge about the relationship between Community Food Systems and Child Nutrition Programs. More information on individual projects can be found on the USDA Office of Community Food Systems’ website at www.fns.usda.gov/farmtoschool/grant-awards.

USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service administers 15 nutrition assistance programs that include the National School Lunch Program, School Breakfast Program, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), and the Summer Food Service Program. Together, these programs comprise America’s nutrition safety net. Farm to school is one of many ways USDA supports locally-produced food and the Local Food Compass Map showcases the federal investments in these efforts. For more information, visit www.fns.usda.gov.

Vertical Farming Startup Plenty Acquires Bright Agrotech to Scale

Vertical Farming Startup Plenty Acquires Bright Agrotech to Scale

California-based vertical farming company Plenty, previously See Jane Farm, has acquired Bright Agrotech in an effort to reach “field-scale.”

Bright Agrotech is an indoor ag hardware company that’s focused on building indoor growing systems for small farmers all over the world, in contrast to Plenty, which is aiming to become a large-scale indoor farming business and currently has a 52,000 sq. ft farm in South San Francisco.

“The need for local produce is not one that small farmers alone can satisfy, and I’m glad that with Plenty we can all work toward bringing people everywhere the freshest food,” said Nate Storey, founder and chairman of Bright Agrotech.

The move to acquire Bright Agrotech will give Plenty the breadth of expertise and intellectual property (IP) to scale with rapid speed, and is a natural move after a four-year relationship, according to Matt Barnard, cofounder and CEO.

“We have a great portfolio of system level IP. They have a great portfolio of component level IP,” he told AgFunderNews. “We’re getting a fire hose of demand from around the globe right now. This is an industry that is emergent, but the way to truly lift it off the ground is to do a whole set of things extraordinarily well.”

Bright Agrotech was founded in 2010 in Laramie, Wyoming, and sells a wide range of indoor farming equipment for indoor vertical farms as well as greenhouses along with smaller systems suitable for homes and business development tools – most of which are under the trademark brand “ZipGrow.”

The relationship between the two businesses started in 2013. Later Storey, the former CEO of Bright Agrotech, became chief science officer at Plenty in a part-time capacity in 2015 and went on to join the team full time earlier this year.

Barnard would not confirm to what extent Plenty already uses Bright Agrotech’s hardware in its farm, which consists of 20-foot high towers with vertical irrigation channels and facing LED lights. Leafy greens ready for picking end up looking similar to a solid wall of green.

Plenty claims to use 1 percent of the water and land of a conventional farm with no pesticides or synthetic fertilizers. Like other large soilless, hi-tech farms growing today, Plenty says it uses custom sensors feeding data-enabled systems resulting in finely-tuned environmental controls to produce greens with superior flavor.

Based on the West Coast, it plans to compete with the existing supply of greens from the salad bowl of California, by choosing premium seeds and catering growing conditions for optimal taste. Barnard says most greens growing in the field are bred to be hardy enough to last the 3,000 mile journey to the east coast and beyond.

He would not share specific growth goals for the near-term, but said that eventually they expect to be able to build two to six farms per month. The plan is to build these farms just outside major cities where retailers have distribution centers and real estate is more affordable. Barnard also said that an announcement about a major retail partnership is forthcoming.

Zack Bogue, an investor in Plenty through San Francisco venture capital fund Data Collective, agreed that the Bright Agrotech acquisition will help the startup scale. “By vertically integrating parts of their component supply chain, it will make the most efficient system out there more efficient,” he said.

Plenty claims to get 350 times the crop yield per year over an outdoor field farm. Or, as Barnard described, “It is the most efficient in terms of the amount of productive capacity per dollar spent, period.”

Plenty was the first indoor ag investment for big data-focused Data Collective, which participated in its $24.5m Series A in July 2016. “We’re pretty excited about that space because some of the hardest problems in agriculture are now lending themselves to an algorithmic or computational or applied machine-learning solution,” he said. But he added that the ability to scale was paramount, because scale is what allows data to be useful for machine-learning applications. “I came away feeling this was an endeavor that could truly achieve global scale pretty quickly,” he added.

Bogue said that though this match was a natural fit, he doesn’t expect more consolidation in the space.

Plenty has raised $26 million to date in a seed and Series A Round, both in 2016. The startup’s other investors are Innovation Endeavors , Bezos Expeditions , Finistere Ventures, Data Collective, Kirenaga Partners, DCM Ventures, and Western Technology Investment

Plenty Acquires Bright Agrotech to Globally Scale Impact of Local Farmers

Plenty Acquires Bright Agrotech to Globally Scale Impact of Local Farmers

Industry-leading technology will play crucial role in Plenty farms

June 13, 2017 - 09:00 AM - Eastern Daylight Time

SOUTH SAN FRANCISCO, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Plenty, the leading field-scale vertical farming company reshaping agriculture to bring fresh and locally grown produce to people everywhere, announced the acquisition of Bright Agrotech, the leader in vertical farming production system technology. Bright’s technology and industry leadership combined with Plenty’s own technology will help Plenty realize its plans to build field-scale indoor farms around the world, bringing the highest quality produce and healthy diets to everyone’s budget.

“Plenty grows food for people, not trucks. By making us all one team and formalizing our deep and close relationship, with a shared passion for bringing people healthy food through local farming, we’re positioned in a way no one else is today to meet the firehose of global demand for local, fresh, healthy food that fits in everyone’s budget,” said Matt Barnard, CEO and co-founder of Plenty. “Everyone wins — the small farmer, people everywhere and Plenty — as we all move forward delivering local food that’s better for people and better for the planet.”

Bright has partnered with small farmers for over seven years to start and grow indoor farms, providing high-tech growing systems and controls, workflow design, education and software. Bright will continue its work, expanding its base of hundreds of farmers around the world.

“We’re excited to join Plenty on their mission to bring the same exceptional quality local produce to families and communities around the world,” said Nate Storey, founder of Bright Agrotech. “The need for local produce and healthy food that fits in everyone’s budget is not one that small farmers alone can satisfy, and I’m glad that with Plenty, we can all work toward bringing people everywhere the freshest, pesticide-free food.”

About Plenty

Plenty is a new kind of farm for a new kind of world. We’re on a mission to bring local produce to people and communities everywhere by growing the freshest, best-tasting fruits and vegetables, while using 1% of the water, less than 1% of the land, and none of the pesticides, synthetic fertilizers, or GMOs of conventional agriculture. Our field-scale indoor vertical farms combine the best in American agriculture and crop science with machine learning, IoT, big data, sophisticated environmental controls and the exceptional flavor and nutritional profiles of heirloom seed stock, enabling us to grow the food nature intended — while minimizing our environmental footprint. Based in San Francisco, Plenty has received funding from leading investors including Eric Schmidt’s Innovation Endeavors, Bezos Expeditions, DCM, Data Collective, Finistere and WTI and is currently building out and scaling its operations to serve people around the world.

Contacts

Plenty

Christina Ra

christina.ra@plenty.ag

High-Tech Farms Give A New Meaning To ‘Locally Grown’

High-Tech Farms Give A New Meaning To ‘Locally Grown’

Published: June 8, 2017 4:58 a.m. ET

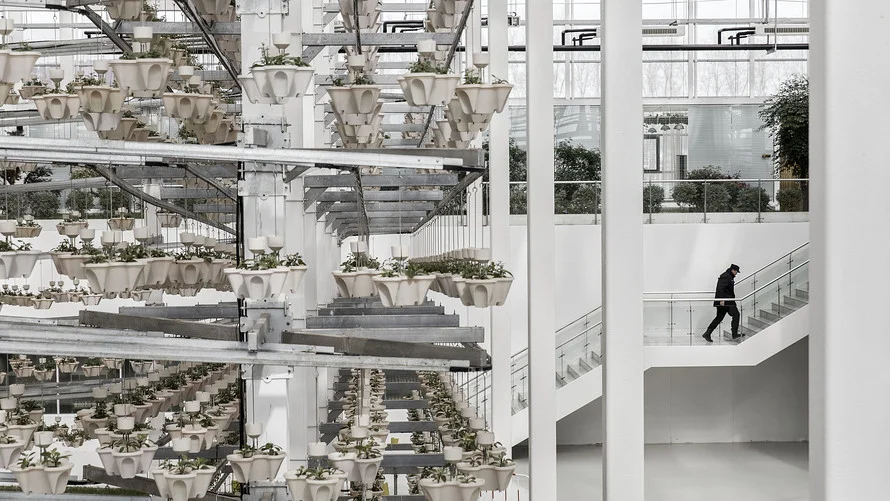

This is the new urban farm

Bloomberg

Plants growing in a rotary light-tracking system inside a greenhouse at a high-tech indoor farm on the outskirts of Beijing. China is turning to technology to make its land productive again.

By Betsy McKay

Billions of people around the world live far from where their food is grown.

It’s a big disconnect in modern life. And it may be about to change.

The world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, 33% more people than are on the planet today, according to projections from the United Nations. About two-thirds of them are expected to live in cities, continuing a migration that has been under way around the world for years.

That’s a lot of mouths to feed, particularly in urban areas. Getting food to people who live far from farms—sometimes hundreds or thousands of miles away—is costly and strains natural resources. And heavy rains, droughts and other extreme weather events can threaten supplies.

Now more startups and city authorities are finding ways to grow food closer to home. High-tech “vertical farms” are sprouting inside warehouses and shipping containers, where lettuce and other greens grow without soil, stacked in horizontal or vertical rows and fed by water and LED lights, which can be customized to control the size, texture or other characteristic of a plant.

Companies are also engineering new ways to grow vegetables in smaller spaces, such as walls, rooftops, balconies, abandoned lots — and kitchens. They’re out to take advantage of a city’s resources, composting food waste and capturing rainwater as it runs off buildings or parking lots.

“We’re currently seeing the biggest movement of humans in the history of the planet, with rural people moving into cities across the world,” says Brendan Condon, co-founder and director of Biofilta Ltd., an Australian environmental-engineering company marketing a “closed-loop” gardening system that aims to use compost and rainwater runoff. “We’ve got rooftops, car parks, walls, balconies. If we can turn these city spaces into farms, then we’re reducing food miles down to food meters.”

Moving beyond experiments

Urban farming isn’t easy. It can require significant investment, and there are bureaucratic hurdles to overcome. Many companies have yet to turn a profit, experts say. A few companies have already failed, and urban-farming experts say many more will be weeded out in the coming years.

Getty Images

In London, former air raid shelters are home to 'Growing Underground', the UK’s first underground farm, shown here in 2016. The farm grows pea shoots, rocket, wasabi mustard, red basil, red amaranth, pink stem radish, garlic chives, fennel and coriander, and supply to restaurants across London.

But commercial vertical farms are well beyond experimental. Companies such as AeroFarms, owned by Dream Holdings Inc., and Urban Produce LLC have designed and operate commercial vertical farms that aim to deliver supplies of greens on a mass scale more cheaply and reliably to cities, by growing food locally indoors year round.

At its headquarters in Irvine, Calif., Urban Produce grows baby kale, wheatgrass and other organic greens in neat rows on shelves stacked 25 high that rotate constantly, as if on a conveyor belt, around the floor of a windowless warehouse. Computer programs determine how much water and LED light the plants receive. Sixteen acres of food grow on a floor measuring an eighth of an acre.

Its “high-density vertical growing system,” which Urban Produce patented, can lower fuel and shipping costs for produce, uses 80% less fertilizer than conventional growing methods, and generates its own filtered water for its produce from humidity in the air, says Edwin Horton Jr., the company’s president and chief executive officer.

“Our ultimate goal is to be completely off the grid,” Horton says.

The company sells the greens to grocers, juice makers and food-service companies, and is in talks to license the growing system to groups in cities around the world, he says. “We want to build these in cities, and we want to employ local people,” he says.

AeroFarms has built a 70,000-square-foot vertical farm in a former steel plant in Newark, N.J., where it is growing leafy greens like arugula and kale aeroponically — a technique in which plant roots are suspended in the air and nourished by a nutrient mist and oxygen — in trays stacked 36 feet high.

The company, which supplies stores from Delaware to Connecticut, has more than $50 million in investment from Prudential, Goldman Sachs and other investors, and aims to install its systems in other cities globally, says David Rosenberg, its chief executive officer. “We envision a farm in cities all over the world,” he says.

AeroFarms says it is offering project management and other services to urban organizations as a partner in the 100 Resilient Cities network of cities that are working on preparing themselves better for 21st century challenges such as food and water shortages.

The bottom line

Still, these farms can’t supply a city’s entire food demand. So far, vertical farms grow mostly leafy greens, because the crops can be turned over quickly, generating cash flow easily in a business that requires extensive capital investment, says Henry Gordon-Smith, managing director of Blue Planet Consulting Services LLC, a Brooklyn, N.Y., company that specializes in the design, implementation and operation of urban agricultural projects globally.

The greens can also be marketed as locally grown to consumers who are seeking fresh produce.

Other types of vegetables require more space. Growing fruits like avocados under LED light might not make sense economically, says Gordon-Smith.

“Light costs money, so growing an avocado under LED lights to only get the fruit to sell is a challenge,” he says.

And the farms aren’t likely to grow wheat, rice or other commodities that provide much of a daily diet, because there is less of a need for them to be fresh, Gordon-Smith says. They can be stored and shipped efficiently, he says.

The farms are also costly to start and run. AeroFarms has yet to turn a profit, though Rosenberg says he expects the company to become profitable in a few months, as its new farm helps it reach a new scale of production. Urban Produce became profitable earlier this year partly by focusing on specialty crops such as microgreens—the first shoots of greens that come up from the seeds—that generally grow indoors in a very condensed space, says Horton, who started the company in 2014.

One of the first commercial vertical-farming companies in the U.S., FarmedHere LLC, closed a 90,000 square-foot farm in a Chicago suburb and merged with another company late last year. “We’ve learned a lot of lessons,” says co-founder Paul Hardej.

Among them: Operating in cities is expensive. The company should have built its first farm in a suburb rather than a Chicago neighborhood, Hardej says. Real estate would have been cheaper.

“We could have been 10 or 20 miles away and still be a local producer,” Hardej says.

The company also might have been able to work with a smaller local government to get permits and rework zoning and other regulations, because indoor farming was a new type of land use, Hardej says. While FarmedHere produced some crops profitably, it spent a lot on overhead for lawyers and accountants “to deal with the regulations,” he says.

Hardej is now co-founder and chief executive officer of Civic Farms LLC, a company that develops a “2.0” version of the vertical farm, he says—more efficient operations that take into account the lessons learned. Civic Farms is collaborating with the University of Arizona on a research and development center at Biosphere 2, the Earth science research facility in Oracle, Ariz., where it runs a vertical farm and develops new technologies.

Blossoming tech

New technology will improve the economic viability of vertical farms, says Gordon-Smith. New cameras, sensors and smartphone apps help monitor plant growth. One company is even developing augmented-reality glasses that can show workers which plants to pick, Gordon-Smith says.

“That is making the payback look a lot better,” he says. “The future is bright for vertical farming, but if you’re building a vertical farm today, be ready for a challenge.”

Some cities are trying to propagate more urban farms and ease the regulatory burden of setting them up. Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed created the post of urban agriculture director in December 2015, with a goal of putting local healthy food within a half-mile of 75% of the city’s residents by 2020. The job includes attracting urban-farming projects to Atlanta and helping projects obtain funding and permits, says Mario Cambardella, who holds the director title.

“I want to be ahead of the curve; I don’t want to be behind,” he says.

Many groups are taking more low-tech or smaller-scale approaches. A program called BetterLife Growers Inc. in Atlanta plans to break ground this fall on a series of greenhouses in an underserved area of the city, where it will grow lettuce and herbs in 2,900 “tower gardens,” thick trunks that stand in large tubs. The plants will be propagated in rock wool, a growing medium consisting of cotton-candy-like fibers made of a melted combination of rock and sand, and then placed into pods in the columns, where they will be regularly watered with a nutrient solution pumped through the tower, says Ellen Macht, president of BetterLife Growers.

The produce will be sold to local educational and medical institutions. “What we wanted to do was create jobs and come up with a product that institutions could use,” she says.

The $12.5 million project is funded in part by a loan from the city of Atlanta, with Cambardella helping by educating grant managers on the growing system and its importance.

Change at home

Another company aims to bring vertical farming to the kitchen. Agrilution GmbH, based in Munich, Germany, plans to start selling a “plantCube” later this year that looks like a mini-refrigerator and grows greens using LED lights and an automatic watering system that can be controlled from a smartphone. “The idea is to really make it a commodity kitchen device,” says Max Loessl, Agrilution’s co-founder and chief executive officer, of the appliance, which will cost 2,000 euros—about $2,200—initially.

The goal is to sell enough to bring the price down, so that in five years the appliance is affordable enough for most people in the developed world, Loessl says.

Biofilta, the company Condon co-founded, is marketing the Foodwall, a modular system of connected containers, an approach that he calls “deliberately low tech” because it doesn’t require electricity or computers to operate. The tubs are filled with a soil-based mix and a “wicking garden-bed technology” that stores and sucks water up from the bottom of the tub to nourish the plants without the need for pumps. The plants need to be watered just once a week in summer, or every three to four weeks in the winter, says Chief Executive Marc Noyce. The tubs can be connected vertically or horizontally on rooftops, balconies or backyards. “We’ve made this gardening for dummies,” Noyce says.

Biofilta

Biofilta's Foodwall

The Foodwall can use composted food waste and harvested rainwater, helping to turn cities into “closed-loop food-production powerhouses,” Condon says.

He and Noyce were motivated to design the Foodwall by a projection from local experts that only 18% of the food consumed in their home city of Melbourne, Australia, will be grown locally by 2050, compared with 41% today, Noyce says.

“We were shocked,” says Noyce. “We’re going to be beholden to other states and other countries dictating our pricing for our own food.”

“Then we started to look at this trend around the world and found it was exactly the same,” he says.

Traditional, rural farming is far from being replaced by all of these new technologies, experts say. The need for food is simply too great. But urban projects can provide a steady supply of fresh produce, helping to improve diets and make a city’s food supply more secure, they say.

“While rural farmers will remain essential to feeding cities, cleverly designed urban farming can produce most of the vegetable requirements of a city,” Condon says.

Betsy McKay is a senior writer in The Wall Street Journal’s Atlanta bureau. She can be reached at betsy.mckay@wsj.com.

The article “A Farm Grows in the City” first appeared in The Wall Street Journal.

Food Revolution

Food Revolution

Applying innovation to agriculture, a student startup plans to use hydroponics to grow fruits and vegetables four times faster using 90 percent less water.

May 04, 2017 | Abigail Lague, avl8bj@virginia.edu

Those walking into the University of Virginia’s Clark Hall find themselves face-to-face with a state-of-the-art hydroponics system. A table full of growing plants and violet light is hard to miss.

As part of an undergraduate sustainability initiative, these systems have been installed in various locations on UVA’s Grounds, including Newcomb Hall and Observatory Hill Dining Hall.

An undergraduate-led company, Babylon Micro-Farms, is bringing these small hydroponic farm prototypes to Grounds as part of an effort to make fresh fruit and vegetables easily accessible for more people.

Hydroponic farming is the growing of plants in nutrient-rich solutions without the use of soil. Usually, hydroponic systems are large, costly and used in mass production – not readily available to the average consumer. However, the system created by Babylon Micro-Farms are less bulky and available for personal use in the home. Each structure is only 6 feet wide by 3 feet deep and about 6 feet tall. Above the plants are LED grow lights that emit light at the right wavelength for photosynthesis.

Plants grown in hydroponics systems, such as those used by Babylon Micro-Farms, are free of GMOs and pesticides. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

This high-tech farming method uses 90 percent less water and grows food up to four times more quickly. Additionally, hydroponics systems do not use genetically modified organisms, pesticides or inorganic fertilizers and help reduce “food miles,” the distance between where a food item is grown and where it is sold.

The Babylon team began testing prototypes around Grounds after building an early model through the student entrepreneurial clubhouse, HackCville, and winning $6,500 from Green Initiatives Funding Tomorrow. Student Council’s sustainability committee, with assistance from the Office of the Dean of Students, funds the annual GIFT grant.

“It’s been a massive hit,” company founder and fourth-year student Alexander Olesen said of the hydroponic systems’ reception in dining halls. “At first, they weren’t too sure about it, and then after a month when the plants grew, they said we could go ahead and pitch them a more finalized version.”

From left, Stefano Rumi, who handles the business expansion of Babylon Micro-Farms; founder Alexander Olesen; electrical engineer Patrick Mahan; and head engineer Graham Smith. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

The hydroponic systems in the dining halls have been growing a mixture of lettuces, arugula, kale and spinach. The yield from one table alone has been enough to feed the entire Babylon Micro-Farms team for about a week. Olesen, a foreign affairs major, and his business partner, third-year student Stefano Rumi, a sociology and social entrepreneurship double-major, hope to add their produce to the UVA Dining menu so that other students may enjoy the vegetables produced by their hydroponics systems.

To make the produce affordable, Babylon Micro-Farms plans to offer a comprehensive hydroponics system for less than $1,000 – something that cannot be found on the market today. Their system will be much smaller than other hydroponic structures and easier to have in the home.

“The existing systems you get are made out of the same materials as trash cans, and they’re still more expensive, which is crazy,” Olesen said. “It’s just a table, and it blends in. You can fit in around 100 plants. Unlike other systems, you have versatility.”

These LED grow lights emit light at a wavelength that facilitates photosynthesis so that the plants will grow faster. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

The system can be easily installed in the home and doesn’t require any special skills to set up, he said.

While the benefits of hydroponics are appealing to many, Olesen is aware that not everyone wants to have to do a “science experiment” at the end of a long day to grow lettuce. With this in mind, Babylon Micro-Farms plans to provide premeasured seeds, nutrients and an automated system to optimize the pH of the hydroponic system, making the process of growing one’s own food as easy as possible. All users have to do is pour in the mixture.

“Food is such a fundamental part of our lives,” Rumi said. “In a world where we’re innovating everything, the last thing we’ve innovated is how we grow our food. We essentially do it the same way we’ve been doing it for 10,000 years, except for pumping unhealthy pesticides that have these terrible environmental effects.”

Alexander Olesen, founder of Babylon Micro-Farms, hopes that his hydroponic systems will soon be put to use in UVA dining halls and low-income areas. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Olesen and Rumi also see a possible educational aspect to of their hydroponics system.

“A lot of the early interest we’ve gotten has been in having these in schools, teaching children how to grow in the community garden, or having these in low-income neighborhoods so that there’s a public space where residents can grow their own food,” Rumi said. “Beyond having the perfect product that everyone can have in their home, we would like to give back to communities that are in need of things like this. I think this is a great step to solving food insecurity.”

“We are connecting people to where food comes from,” Olesen said.

Babylon Micro-Farms is now in beta testing with customers and currently taking preorders. The startup team also will participate in UVA’s 2017 i.Lab incubator summer cohort.

Media Contact

Katie McNally - University News Associate Office of University Communications

katiemcnally@virginia.edu 434-297-6784

Making A Life Out of Lettuce

Making A Life Out of Lettuce

Controlled environment hydroponic lettuce growing provides an honest living for Jeff Adams and the employees of Circle A Farms in Cumming, Ga.

Jeff Adams started growing lettuce after 20 years of working as a contractor. Photo courtesy of Jeff Adams

Like others with a strong work ethic and an affinity for the outdoors, Jeff Adams enjoys what he does for a living. It’s demanding work to simultaneously grow and sell multiple varieties of lettuce — a job that, for him, doesn’t let up any time of the year. However, it’s worth the time he gets to spend in greenhouses and in the community learning the intricacies of growing and selling hydroponic produce.

A contractor by trade for 20 years, Adams didn’t have any experience with controlled environment agriculture (CEA) before he constructed his first two CropKing greenhouses in 2011 (He has since built two more). He did, however, have a passion for farming. He owned about 30 heads of cattle and grew lettuce in the backyard of his 13-acre Cumming, Ga., home.

Adams became interested in CEA and CropKing’s computer-controlled, hydroponic greenhouses when he read about R & G Farm, a lettuce grower based out of Dublin, Ga., in Hobby Farms magazine (Editor’s note: Read Produce Grower’s story on R & G Farm at bit.ly/2lsRZDe). “I started researching it for about two years, and went and took some classes through CropKing on it and just decided, ‘What the heck?’,” he says. “I think it might fit what we want to do in our passion for farming and growing. And we pulled the trigger. It’s been five years now.”

With a total of eight employees, a growing customer base and fresh, quality lettuce, Adams’ business, Circle A Farms, continues to grow.

Edible Education

Once Adams began growing produce in a greenhouse, it didn’t take long for him to realize that growing hydroponically is much different than growing in the ground.

Through its training materials and information, CropKing has helped Adams make his operation a success. “They have such a wealth of knowledge, and they’ve done it for so long, that, to me, they’re just a viable source that I’d hate to be without,” he says.

Adams' greenhouses control the environment — heating, cooling, air movement, nutrient supplies and carbon dioxide — through computers, he says. Adams has adjusted growth spacing by drilling small holes to accommodate growing baby lettuce.

Using nutrient film technique (NFT) trays, Circle A Farms grows nine varieties of lettuce, Adams says. “We grow bibb, romaine, spring mix, kale, arugula, basil and we do microgreens,” he says. “And there’s a couple other varieties. We do tropicana, frisee. All just leafy greens.”

Selling to local markets and consumers

Most of Circle A Farms’ customer base, which consists of stores and restaurants, are within about a 15-mile radius of the growing operation, Adams says.

Like many other CEA growers, Circle A Farms often markets directly to consumers through avenues such as local farmers markets. In January, it began delivering directly to customers’ homes through its new Farm to Porch program.

To participate in Farm to Porch, area customers find their location listed as a “zone” on circlealettuce.com and place a lettuce order, Adams says. “You either put a cooler out or we can sell you a cooler bag that you leave out, and then it’s delivered right to your porch,” he says.

I think a lot of people come into [CEA] like they’re going to make a lot of money — a get rich quick kind of deal — and that’s not the case, but there is some profitability. — Jeff Adams, Circle A Farms

Because Circle A Lettuce is grown in ideal conditions with computer-controlled nutrition levels, and sold to local markets, it has an approximately three-week shelf life, compared to lettuce that is shipped long distances, which often has a shelf life of only four to five days, Adams says. “It’s a great, wonderful product,” he says. “You just have to educate the consumer why they’re paying a little bit more for the product.”

When it comes to revenue streams for Circle A Farms, enough money comes in to provide Adams and his employees with a steady income, but that’s because of the hard work they put into the operation. “I think a lot of people come into [CEA] like they’re going to make a lot of money — a get rich quick kind of deal — and that’s not the case,” he says. “But there is some profitability.”

Growing Pains

It is often difficult to predict what will happen from one day to the next, Adams says. Tip burn and other problems have arisen that have taught Adams and his employees how to best care for the lettuce.

When production hiccups take a toll on a crop, customers still have the same expectations as when production is going flawlessly, Adams says. “They get used to your consistency and they start thinking you can produce it like a widget, that you can just turn out as many as you can, when still, you have issues and you have problems, and you might lose a crop of bibb or a crop of something here and there,” he says.

Many factors, such as lettuce variety and time of year, determine production cycles, Adams says. Circle A Farms doesn’t track how many cycles it produces in a year because they are constantly changing and rotating. Some lettuces have rotations of 30 days, while others have rotations of 45 to more than 50 days.

“It never stops growing, so you can’t just shut it down and leave,” Adams says. “It’s kind of like having chickens, except with chickens you get a break every six or so many weeks. With this, you never get a break.”

Still, Adams says he finds his work affords him an honest living. He doesn’t mind the extra hours he puts in throughout the week. “If you don’t mind hard work, weekends, nights, whatever — things happen, problems happen, you’ve got to be around — it can be rewarding because the product we’re able to turn out is superior to anything that’s out there

Company Overview: INFARM - Grow Where You Are

Company Overview: INFARM - Grow Where You Are

INFARM is pioneering on-demand farming services to provide urban communities with fresh, nutritious produce, by distributing smart vertical farms in strategic centers of consumption. Our modular farms are highly efficient and can be easily deployed in any given space whether that be a supermarket, a restaurant, a school or a vacant warehouse.

Our Vision

We believe our food system should be decentralized and food production should get closer to the consum-er. INFARM offers an alternative food system that is responsive, transparent, and accessible, while allowing for significant improvement in the safety, quality, and environmental footprint of our food.

INFARM is bringing farming into the city, directly where people live and eat. Our vertical farming technology is the foundation for building urban farm-ing networks that will help cities become resilient and self-sufficient in their food production, while providing city-dwellers fresh, affordable, healthy produce all year round.

Our Farms

Our farms are comprised of modular hydroponic farming units that can be stacked and expanded, depending on the needs of our clients. All parameters of the farming unit are automated and constantly optimize the growing environment to ensure each plant gets the best conditions to thrive. Each individual farm is connected to our central farm-ing platform through IoT technology, that allows us to respond in real-time to fluctuations in demand.

Farming-As-A-Service™

Our clients pay a monthly subscription fee for farm capac-ity while INFARM’s dedicated team of professional growers operate the farms and care for the life of the plants. We work closely with each client to understand their needs and the demands of their customers to deliver a tailored assortment of fresh produce.

Our Produce

We grow the freshest, most nutritious, flavorful and beautiful produce, year round. Our grow-on-site approach means our plants have zero food miles and replace the need to import products from abroad.

We grow plants that are well known and loved, as well as rare and heirloom species which are forgotten or are hard to find. To ensure the maximum natural expression of each plant, our team of plant specialists develop unique growing recipes; tailoring the light, temperature, pH and nutrients to perfectly suit the plant type.

Our Story

INFARM was founded by Osnat Michaeli and brothers Erez and Guy Galonska when they came to Berlin in 2013. When they started out, they were motivated by what they wanted from their own lives – to be more independent, to eat healthier, and to experience the excitement of growing their own food. They built their first hydroponic farm in their apartment in Berlin, harvesting fresh vegetables on a snowy day in February. The empow-erment that came about from growing their own food, motivated them to explore urban farming further.

Over the following months, the trio began investigating the challenges facing farming in urban environments. They started to research and test methods to tackle these issues, from both a technological and strategic perspective until they arrived at a product and business model that they believed could truly shift the paradigm of food production.

Today, INFARM has grown to a 30 person company based in a large industrial warehouse in Kreuzberg, Berlin.

Our Team

Our home town of Berlin attracts like-minded individuals who are committed to making real change. This has allowed us to gather a diverse team with backgrounds in plant science, industrial design, engineering, architecture, IT, marketing and business.

Our Core Team Includes:

CEO: Erez Galonska

CTO: Guy Galonska

CMO: Osnat Michaeli

CFO: Martin Weber

Chief Science Officer: Pavlos Kalaitzoglou

Chief Growing Officer: Nico Domurath

Chief Information Officer: Alain Scialoja

News Coverage

Over the past few years, INFARM has been covered by publications including Tagesspiegel, Germany Trade & Invest, Fast Co Exist, The Guardian, Venture Village, Zeit and Inhabitat, amogst others.

– For complete press information, contact us.

Contact Information

Rebecca Griffiths

Head of Marketing & Communications Email: press@infarm.de

Phone: +49 30 55 63 00 48

Company Highlights

- Secured international patents on key technology.

- Built and operating the first in-store farms in the world in the METRO Cash & Carry in Berlin & Makro Antwerp.

- The first vertical farming company to be certified with GLOBALG.A.P.

- INFARM has received funding from the H2020 SME Instrument for the project “The vertical farming revolution, urban Farming as a Service.

- Selected by the European Commission as one of the top 4% of Europe’s leading innovators in the field of agriculture and technology.

- First prize in the Innovation Weekend Startup Competition in Tokyo, Japan.

- First prize in the Vision Award Competition 2016 Munich, Germany.

Indoor Urban Farming GmbH | Glogauer Str. 6, 10999 Berlin | www.infarm.com

EU Awards Greek Patent for Automated Indoor Farming

EU Awards Greek Patent for Automated Indoor Farming

By Philip Chrysopoulos | Jun 11, 2017

The European Commission on Wednesday awarded Christos Raftogiannis and Evriviadis Makridis for their invention of an Automated Indoor Farming device with which you can grow 40 different fruits and vegetables in your home.

CityCrop offers a fully automated indoor garden based on the technique of hydroponics. The two Greek men were awarded as best startup in the category “Smart Cities”.

The company was incorporated in 2015 and is based in London. CityCrop created the mobile device and application that allows users to grow fresh and healthy food all year-long as well as control and monitor their crops. Users can grow leafy green vegetables, herbs, fruits, edible flowers, and microgreens.

The device can take up to 40 glass cubes and the owner can grow spinach, cherry tomatoes, kale, radish, strawberries, basil, cilantro, lettuce and more. CityCrop can take 10 liters of water and its power consumption does not exceed five euros per month. Inside the glass cube the appropriate humidity, temperature and lighting conditions of plant growth are ensured. Furthermore, the device should be connected on the internet so that the grower can have constant contact with the plants to cater to their needs, such as add more water or adjust the temperature.

The cost of CityCrop is currently 1,000 euros, but could be reduced significantly if it is mass-produced.

Lake Stevens High Seniors Convert Fridge to Hydroponic Garden

Lake Stevens High School seniors Isabelle Eelnurme (left) and Elise Gooding converted an old refrigerator to a hydroponic garden for their engineering design class. Their award-winning device is for growing healthy, nutritious produce in food deserts. (Dan Bates / The Herald)

Lake Stevens High Seniors Convert Fridge to Hydroponic Garden

- KARI BRAY Sat Jun 10th, 2017 1:30am

LAKE STEVENS — Isabelle Eelnurme and Elise Gooding salvaged the small refrigerator from Eelnurme’s grandparents’ back yard.

It was a putrid shade of yellow. The brand label wore off long ago. They cleaned out bugs and grime.

Then the teens painted it turquoise and turned it into a hydroponic garden. It’s a contained produce-growing system that doesn’t require soil or much space. They picture it in apartments in neighborhoods where poverty is high and access to fresh fruit and vegetables is limited.

At the beginning of the school year, the 18-year-olds set out to find a solution for food deserts, which are areas where people lack healthy, affordable food. During their research, they noted a link to health issues such as diabetes. They also found that there are deserts close to home, with more than a dozen in Seattle.

The transformation of an old refrigerator into a hydroponic garden was a year-long project, part of the engineering and design course at Lake Stevens High School. The friends have been in engineering classes since they were in ninth grade. Both plan to continue with those studies.

Gooding is bound for California Polytechnic State University and Eelnurme for the University of Washington this fall. Both are interested in civil engineering, and Eelnurme also wants to focus on environmental engineering.

The engineering and design course has been at the high school for about 10 years, teacher Kit Shanholtzer said. Students from the program have gone on to find success. He recalls one phone call from the FBI to background a job candidate, one of the first students who had gone through the course.

Students are tasked with defining an issue, researching solutions and coming up with their own version of how to solve the problem. Some look at transportation projects such as trains and bridges, while others focus on safety, health and quality of life.

“It’s wonderful when I can just mentor and guide, and the students have the drive and passion to do the project,” Shanholtzer said.

Eelnurme and Gooding have that drive. They’re professional and dedicated to their work, he said.

Though a school year seems like a long time for one project, students just have an hour per day in class, Shanholtzer said. If the annual hours are converted into 40-hour work weeks, students have about a month.

They don’t need to come up with new inventions, but rather an innovative approach to an existing solution. Hydroponic gardens aren’t new. Recycling outdated appliances into an easy-to-use system is a creative approach. Next, Eelnurme and Gooding hope to make one with a full-size fridge.

The two talked over more than 60 ideas before settling, they said. They wanted to think outside the box, but keep their project realistic.

Neither knew what a food desert was prior to doing an essay for their college-level English class. They learned just how widespread and often invisible the problem is.

“We didn’t know people were going without fresh produce,” Eelnurme said. “All they have is maybe a convenience store or fast food because fresh produce is too far away, and they don’t have a car to get there. We need to bring the produce to them.”

Inside the fridge-turned-garden, the portion that once was a freezer is where seeds start to germinate in small, cubic pods. The pods then go into the main body of the fridge, with a water spout and aerator. A gutter downspout has been repurposed into a container and magnetically attached inside the fridge. Once a plant grows to edible size, the downspout can be pulled out, the pod removed and a new one slotted in. The system doesn’t work for root plants such as carrots, but it’s good for lettuce, spinach and other leafy greens.

The students took their work to several engineering fairs, winning accolades at the regional and state level. Most recently, they received an honorable mention at the Imagine Tomorrow engineering fair at Washington State University, where more than 100 teams competed.

The WSU competition was the same day as their prom, so they woke up at 6 a.m. on the other side of the state, spent most of the day at the fair and caught an hour-long flight home to dance in Seattle. They got home around 1 a.m., exhausted and accomplished.

They hope students in next year’s engineering and design program will find projects they’re passionate about, and have fun while they figure out ways to make a difference in the world.

Kari Bray: 425-339-3439; kbray@heraldnet.com.

With their refrigerator-turned-hydroponic garden, Isabelle Eelnurme and Elise Gooding received an honorable mention at the Imagine Tomorrow engineering fair at Washington State University, where more than 100 teams competed. (Dan Bates / The Herald)

These Food Computers Use AI To Make “Climate Recipes” For The Best-Tasting Crops

06.09.17

These Food Computers Use AI To Make “Climate Recipes” For The Best-Tasting Crops

The tech-filled greenhouses can adjust growing conditions over and over again until they find the combination of light, humidity, and other factors that make the most delicious vegetables.

When the researchers asked the algorithm to optimize for flavor, there was as much as a 895% increase in the plant’s production of one specific flavor molecule. [Photo: Open Agriculture Initiative/MIT Media Lab]

Inside a shipping container-sized box at MIT Media Lab, crops of basil are growing in micro-climates designed by artificial intelligence. The first experiments, with controlled levels and duration of UV light, aim to grow a tastier version. As the mini-greenhouse generates roughly 3 million data points for each growth cycle of a single plant, the AI uses machine learning to analyze it and create new and better “climate recipes”–which can then be shared with anyone trying to grow food indoors.

As climate change makes it more difficult to grow crops in outdoor farms because of heat waves, more frequent storms, and more pests and disease, the researchers envision that climate-controlled, tech-filled greenhouses (which they call “food computers”) could be an increasingly useful place to grow food. The technology could also eliminate food miles: Instead of shipping avocados from Mexico to China, a Chinese greenhouse could precisely recreate a Mexican climate in Beijing–or tweak it to create a climate even better for an avocado tree.

It definitely speeds up the timescale by which we can get interesting results.” [Photo: Open Agriculture Initiative/MIT Media Lab]

Researchers at the Media Lab first developed a prototype of what they call the OpenAg Personal Food Computer in 2015. The contained growing environment, packed with sensors, actuators, and machine vision, can study and then replicate optimal growing conditions for food, changing everything from the pattern and spectrum of light used to the salinity of water and the nutrients added. A larger version, the Food Server, is the size of a shipping container, with racks of plants that can each be grown with unique variables. Initially, the researchers analyzed the data themselves to improve their climate recipes. But in June 2016, the team began working with the AI company Sentient to use its software to optimize the growing environment more quickly.

“It definitely speeds up the timescale by which we can get interesting results,” says Arielle Johnson, one of the researchers at MIT Media Lab Open Agriculture Initiative, or OpenAg.

“When you talk to [Caleb Harper, the director of OpenAg], he’s like, ‘Yeah, basil is a fast-growing plant,’ but in his terminology, fast-growing is six to eight weeks,” says Babak Hodjat, CEO of Sentient, a company that also designs AI to help stock traders find patterns in the market and hospitals predict infections. “That’s a long time to wait just to get a data point. So we tried out this methodology where the AI itself decides what are the next set of data points to try out.”

The basil is grown in staggered batches, so the AI can use the data from each batch to suggest changes to the “climate recipe” for the next crop before the first crop is finished growing, increasing the experimental throughput.

When the researchers asked the algorithm to optimize for flavor–by creating an environment that would maximize the number of volatile molecules in the plant–they discovered that if the lights in the Food Computer stayed on continuously, there was as much as a 895% increase in the plant’s production of one specific flavor molecule, and a 674% increase in production of another. The AI also rediscovered a known trade-off between weight and flavor (the bigger the plant, the less delicious).

“We’re trying to provide the standard that is open for all of this data and optimization to be shared by anybody.” [Photo: Open Agriculture Initiative/MIT Media Lab]

Using AI, the team will be able to optimize its climate recipes for multiple factors, including taste, cost, and sustainability, and create recipes for growing a myriad of crops. All of the data is available open-source, along with instructions to build a food computer yourself. “It can be made by anyone with reasonable hacking skills,” says Johnson.

The fact that it’s open-source distinguishes it from related research happening at vertical farming companies (some of which are also using artificial intelligence) or places like Philips’ GrowWise research center for urban farming in the Netherlands.

“Most people doing this kind of research, it’s proprietary, and it’s to optimize their own setups,” says Johnson. “Where I think we’re really strong is, more than trying to optimize something for ourselves, we’re trying to provide the standard that is open for all of this data and optimization to be shared by anybody.”

For fledgling indoor farming companies, the open-source climate recipes could help farmers grow better tasting, more productive, more efficient crops. New indoor farming companies typically invest heavily in their own research. “What we’ve seen is massive capital expenditure to get something up and running using controlled environments,” says Hildreth England, assistant director of the Open Agriculture Initiative. “But what happens is they sort of have to iterate in isolation.” The team envisions creating a shared language for indoor farming, “like the Linux of agriculture,” she says. “If we’re all using the same baseline, then that just lifts everybody up in an industry that is still trying to figure out its place in the conventional ag world.”

The research could also lead to tastier, more sustainably grown food, created without the type of genetic modification that some consumers find objectionable. “Ultimately, this is non-GMO GMO,” says Hodjat. “You’re not messing with the plant’s DNA . . . you’re just allowing it exhibit behavior that it would in nature should that kind of environment exist.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Adele Peters is a staff writer at Fast Company who focuses on solutions to some of the world's largest problems, from climate change to homelessness. Previously, she worked with GOOD, BioLite, and the Sustainable Products and Solutions program at UC Berkeley. More

These #4 Start-ups Are Promoting Hydroponics in India

These #4 Start-ups Are Promoting Hydroponics in India

Hydroponics or growing plants in water or sand, rather than soil, is done using mineral nutrient solutions in a water solvent

Image credit: Pixabay

Feature Writer, Entrepreneur.com

JUNE 8, 2017

You're reading Entrepreneur India, an international franchise of Entrepreneur Media.

Only an expert gardener knows how difficult it can be to grow plants and how much extra care it takes with special attention to soil, fertilizer and light. One can’t get the process right and expect good yields without getting his/her hands dirty. But, to make their work a lot easy and convenient, many start-ups in India are working on hydroponics farming.

Hydroponics or growing plants in water or sand, rather than soil, is done using mineral nutrient solutions in a water solvent.Additionally, this indoor farming technique induces plant growth, making the process 50 per cent faster than growth in soil and the method is cost-effective. Mineral nutrient solutions are used to feed plants in water.

Here’s a list of four start-ups in India that are innovating agriculture methods and leading the way in indoor farming.

Letcetra Agritech

Letcetra Agritech is Goa’s first, indoor hydroponics farm, growing good quality, pesticide-free vegetables. The farm in Goa’s Mapusa is an unused shed and currently, produces over 1.5 to 2 tons of leafy vegetables like various varieties of lettuce and herbs in its 150 sq metre area. The start-up is founded by Ajay Naik, a software engineer-turned-hydroponics farmer. He gave up his IT job to help farmers in the country.

BitMantis Innovations

Bengaluru-based Iot and data analytics start-up BitMantis Innovation with its IoT solution GreenSAGE enables individuals and commercial growers to conveniently grow fresh herbs throughout the year. The GreenSAGE is a micro-edition kit that uses hydroponics methods for efficient use of water and nutrients. It is equipped with two trays to grow micro-greens at one’s own convenience.

Junga FreshnGreen

Agri-tech start-up Junga FreshnGreen has joined hands with InfraCo Asia Development Pte. Ltd. (IAD) this year to develop hydroponics farming methods in India. The project started with the development of a 9.3-hectare hydroponics-based agricultural facility at Junga in Himachal Pradesh’s Shimla district.

Junga FreshnGreen is a joint venture with a leading Netherlands-based Agricultural technology company – Westlandse Project Combinatie BV (WPC) — to set up high-technology farms in India. Their goal is to create a Hydroponics model cultivating farm fresh vegetables that have a predictable quality, having little or no pesticides and unaffected by weather or soil conditions. They will be grown in a protected, greenhouse environment.

Future Farms

Chennai-based Future Farms develops effective and accessible farming kits to facilitate Hydroponics that preserve environment while growing cleaner, fresher and healthier produce. It focuses on being environment friendly through rooftop farming and precision agriculture. The company develops indigenous systems and solutions, made from premium, food grade materials that are efficient and affordable.

Ideas We Should Steal: Urban Food Forest

Ideas We Should Steal: Urban Food Forest

Seattle’s Beacon Forest provides free native edibles to anyone in the city. Could the soda tax make it possible for a Philly group to do the same here?

JUN. 05, 2017

Imagine this: On a two-acre plot of land, at the edge of Fairmount Park, sits a forest hearkening back to the days when nature—not people—ruled the planet. Fruit trees tower over berry shrubs, fruit-bearing vines creep upwards. Insects, birds, animals fill the spaces in between. And every day, scores of Philadelphians wander through, filling their arms with fresh produce to take home—all for free.

This is the vision of a group of Philadelphia food access advocates—and it’s not as crazy as it seems. In fact, there’s precedent in Seattle.

Beacon Food Forest, in Seattle’s Beacon Hill, will be the largest food forest on public land in the country when it is complete. So far, it occupies two acres of a seven-acre plot sitting above a covered reservoir in South Seattle; this summer, the mostly volunteers who maintain the forest will plant another two acres. The garden contains 420 different species of edibles, some native to Seattle, like rasberries, huckleberries and walnuts, and some a reflection of the surrounding communities of Chinese, Vietnamese, Somalians, Latinos and African Americans, like Chinese pepper trees, persimmons and figs. Everything grown at Beacon Forest is free to anyone and everyone who wants to pick it at anytime.

Muehlbauer says he is hopeful that the city will grant his group a couple of acres in Fairmount Park to launch a food forest. And it is conceivable that the city could help to fund Fair Amount Food Forest with revenue from the tax on sugary beverages, a portion of which is slated for public park improvement.

“The goal is to create community and awareness around a local food supply, what you can grow that you don’t get in grocery stores,” says Glenn Herlihy, the forest’s co-founder. “It’s social healing and land healing at the same time.”

Beacon Forest is an example of permaculture, which means it is self-sustaining and perennial. The idea came out of a permaculture workshop Herlihy took in 2009, when for his final project, he decided to design a dream farm on an undeveloped piece of land next to a large park in his neighborhood of Beacon Hill. He passed the class, and then took his idea to the community, where he found a willing group of residents who decided to make his dream a reality. In 2012, after securing permission from Seattle Public Utilities and $140,000, mostly from the city’s Department of Neighborhoods, Beacon Forest broke ground.

Five years later, Beacon has become a model of urban forestry that holds two principles steadfast: Remaining true to the land, and to the community it serves. “In a food forest, you’re looking for collaboration between the community, what you can grow and what’s available,” Herlihy says. The plantings utilize what ecoloigsts call the seven layers of a food forest—trees at the top, ground cover at the bottom with shrubs, pollinators, vines in between. Those plants then propagate naturally, and shift—where berry bushes used to be most prominent, the trees have now blocked the sun, and have started providing more of the fruit. The land is also becoming what Herlihy calls a “genetic food bank” for edible plants that are dying around the globe.

All of it—the planting, the upkeep, the harvesting—depends on the community. Only a few workers, like construction managers and teachers, receive occasional stipends. The rest of the 80 or so regular planters are volunteers from all over the city. Meanwhile, the food grown is picked regularly by neighbors, and anyone else who travels to South Seattle. How many people have eaten from the garden is unclear since it is unmonitored, on public land, and free.

“There are people in the city who don’t know how to use a shovel, never planted a tree, but really want to,” Herlihy says. “They haven’t had that experience of being able to forage in a public area, and the joy of finding a bunch of berries that they’ve never had before, like a goji berry. It’s an amazing experience.”

Like so many projects of its kind, Beacon was made possible by several different factors: A dedicated group of volunteers; a city willing to work with them; and available public funding, partly as a result of a levy approved by voters to make improvements to Seattle’s many parks.

That’s what makes this such an optimal time for a group of Philly volunteers working to develop what they call Fair Amount Food Forest, a publicly accessible food forest in Fairmount Park. Formed a little over a year ago by Michael Muehlbauer, a landscaper, farmer, and builder who was a core Beacon Forest member when he lived in Seattle, the initiative is in the very early planning stages—talking to the city, forming partnerships with like-minded organizations, reaching out to neighborhoods that abut Fairmount Park to see who, if anyone, would want something like the Beacon Food Forest in their community.

Muehlbauer, a Wisconsin native who had an edible landscaping business in Seattle, says he realized about six months after moving to Philly that this city—vastly different from that on the west coast—could be ready for this. “The people I’ve met and consistent, random conversations made me think, ‘We needed you at Beacon,’” Muehlbauer says. Those people now form the core of his planning group. “I realized we could do this really well here, maybe even better than in Seattle.”

Beacon contains 420 different species of edibles, some native to Seattle, and some a reflection of the surrounding communities of Chinese, Vietnamese, Somalians, Latinos and African Americans. Everything grown at Beacon Forest is free to anyone and everyone who wants to pick it at anytime.

Muehlbauer says he is hopeful that the city will grant his group a couple of acres in Fairmount Park to launch a food forest. And it is conceivable that the city could help to fund it with revenue from the tax on sugary beverages, a portion of which is slated for public park improvement. Like Beacon in Seattle, though, the city has first asked them to find other community partners and to get neighborhood buy-in for the project. Fair Amount is spending the next few months talking to residents who would be most affected by a public forest. “We don’t want to create this somewhere if no one wants it,” Muehlbauer says.

If Fair Amount gets off (into) the ground it would take Philly’s urban gardening movement to a whole new level. First there were community gardens, often built on empty lots across the city. Then urban farming took off, led by Fishtown’s Greensgrow Farms, which opened in 1997. The Philly Orchard Project launched 10 years later, and has now planted nearly 60 tree and berry farms on empty lots throughout town, harvesting some 3,000 pounds of fruit a year. A public food forest would go even further: Native plants set on to grounds that are, always, open to the public, for anyone to reap as they see fit.