Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Urban Farm Grows Ugly Greens In Brooklyn, NY

Urban Farm Grows Ugly Greens In Brooklyn, NY

Good greens don’t have to ‘look’ pretty. Even ‘ugly’ produce is just as delicious. This is something Gotham Greens has discovered through its recent Ugly Greens movement. What may have once been considered unmarketable produce was enjoyed by the staff at work or home instead. “We’d enjoy them as part of a team meal and staff would take them home to eat,” explains CEO, Viraj Puri. “But we realized there was an opportunity to sell them while helping to bring attention to the issue of food waste. The amount of food waste in this country is staggering and the NRDC estimates that as much as 50% of produce is thrown out between the farm and the fork.” They’re hoping to show people that slightly blemished greens can be perfectly nutritious, fresh and local despite their cosmetic flaws. “By embracing cosmetically-challenged produce as beautiful, we’re hoping to play a small role in reducing food waste,” he adds.

Food is wasted for cosmetic reasons

Food waste is a concerning issue for consumers, something all retailers and growers should keep top of mind. Puri says that in the US over 70 billion pounds of food is wasted each year which amounts to 250 pounds per person. “Much of what’s discarded is done merely for cosmetic reasons or as a result of long distance transportation. This negatively impacts farmers, retailers and ultimately consumers.” Changing consumer’s preferences towards slightly blemished or imperfect fruits and vegetables is an additional way to address the issue. Feedback on Gotham’s program has been overwhelming, according to Puri and even though it’s a small part of their production and overall business, they’re excited to see the positive feedback.

Current greens being grown and harvested include about a dozen varieties of leafy greens, arugula, and basil. And, supply is good. “Our current production is very strong,” he says. “We’re able to offer our customers a very reliable and consistent supply of greens all year round.”

Year-round availability

Gotham Greens stands by its model of urban agriculture, something Puri says is appreciated by chefs and retail produce buyers. “We grow premium quality local produce in high tech, climate controlled greenhouses, year round. That means, even in the dead of winter, we provide our customers— supermarkets, restaurants, caterers—with fresh produce within a couple of hours of harvest.” Produce is pesticide-free, grown using ecologically sustainable methods in 100% clean, electricity-powered greenhouses. He says this also results in providing precision plant nutrition and optimal growing conditions for the plants. “Hydroponic farming, when practiced effectively, can be very efficient, using a fraction of the amount of resources as traditional farming practices. This enables us to use one tenth the amount of water as traditional soil based practices, while also eliminating all agricultural runoff.”

There may be plans of expansion in the works. Gotham Greens has several new projects planned which could bring urban farming to other cities across the US and globally. “We have several new projects in the works and look forward to sharing more information about them in the coming months.”

For more information: Viraj Puri | Gotham Greens

Publication date: 8/8/2017

Author: Rebecca D Dumais

Copyright: www.freshplaza.com

Thomas Paine Plaza Will Transform Into A Big Urban Farm in 2018

Thomas Paine Plaza Will Transform Into A Big Urban Farm in 2018

The PHS-run Farm Will Produce 1,000 Pounds of Fruits and Vegetables

BY MELISSA ROMERO JUN 20, 2017, 12:00PM EDT

PHS will bring a temporary urban farm to Thomas Paine Plaza, similar to this pop-up garden that was set up at in 2011 at 20th and Market.

Photo courtesy of Pennsylvania Horticultural Society

Goodbye, larger than life Parcheesi pieces, hello 2,000-square-foot urban farm: Next summer, the Thomas Paine Plaza in Center City will be transformed into a large community farm that’s estimated to produce about 1,000 pounds of fruits and vegetables.

The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS) was just awarded a $300,000 grant from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage to create a “Farm for the City” at Thomas Paine Plaza, across from City Hall. The plaza is well-known for its 20-year-old “Your Move” art installation that features over-sized dominoes, chess and bingo pieces, and other game pieces scattered all over the plaza.

Thomas Paine Plaza in Center City, Philadelphia. via Flickr/Wally Gobetz

Farm for the City will bring a temporary 2,000-square-foot urban farm to the plaza as way to spotlight food security in the city, where many neighborhoods lack easy access to supermarkets or fresh food. In addition to the actual farm, the site will play host to forums, gardening workshops, and performances throughout the summer and fall of 2018.

Meanwhile, the produce produced from the farm will be donated to Broad Street Ministry, a non-profit organization that serves the homeless. The ministry, which will help tend the garden, says it will also host two community dinners for 150 people using the food grown at the farm.

PHS spokesperson Alan Jaffe says the design is still in the very early stages, so we’ll have to wait a little longer for a preview of Thomas Paine Plaza’s transformation and whether the “Your Move” art installation will remain in place.

Urban Hydroponic Farms Offer Sustainable Water Solutions

Urban Hydroponic Farms Offer Sustainable Water Solutions

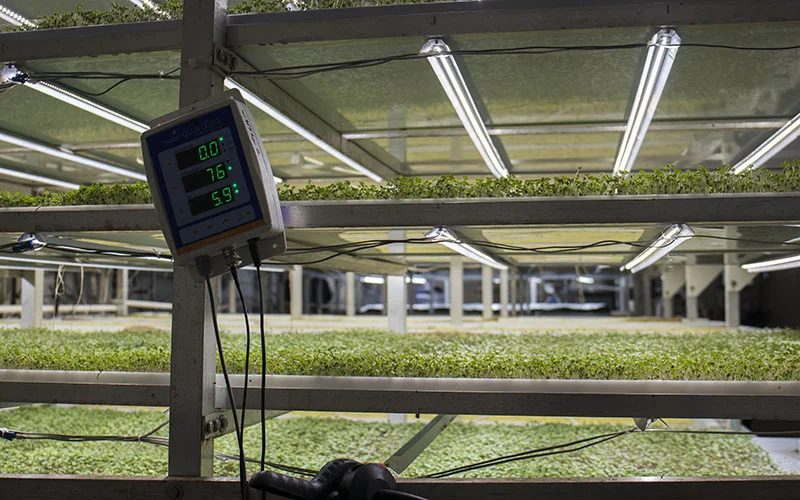

At Local Goods in California, Ron Mitchell’s monitoring system checks the plants’ water supplies for temperature, pH levels and electric conductivity. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

By Nicole Tyau | News21 Tuesday, July 11, 2017

BERKELEY, Calif. – Tucked behind a Whole Foods in a corner warehouse unit, Ron and Faye Mitchell grow 8,000 pounds of food each month without using any soil, and they recycle the water their plants don’t use.

Hydroponic farming grows crops without soil. Instead, farmers add nutrients to the water the plants use. This method can produce a wide variety of plants, from leafy greens to dwarf fruit trees.

According to a study by the Arizona State University School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, hydroponic lettuce farming used about one-tenth of the water that conventional lettuce farming did in Yuma, Ariz. A similar study from the University of Nevada, Reno, found that growing strawberries hydroponically in a greenhouse environment also used significantly less water than conventional methods.

(Video by Jackie Wang/News21)

The Mitchells started production of Local Greens in February 2014. They primarily grow microgreens such as kale, kohlrabi and sprouted beans while using the same amount of water as two average households and the same amount of electricity as three in a month, they said.

“Who knows what you’re getting when you’re using soil?” Faye said. “Hydroponics is a fully contained system, so we know exactly what’s in our water, what we want in it and what we don’t want in it, and we can control that.”

Ron installed a water filtration system he customized. He removes fluoride, a common additive in municipal water, and chlorine, a common disinfection byproduct, before adding oxygen and other plant-specific nutrients.

At Local Greens, Ron and Faye Mitchell mostly cultivate microgreens, which grow to about 10 inches before they are cut and sold in the area. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

To make use of the warehouse’s tall ceilings, the Mitchells stack six trays of microgreen seeds on top of each other. At one end, an irrigation spout controls the amount and type of water sent through the trays.

“Some plants don’t need or want nutrients because they have it in their seed,” Ron said. He explained that pea shoots don’t need any additives, but sunflowers require copious amounts of nutrients to grow quickly.

Ron Mitchell, 67, said the stacked trays inside his hydroponic farming facility in California allow them to grow twice as much. (Photo by Jackie Wang/News21)

The water the plants don’t use is captured at the other end of the tray and reused for the next watering, with the nutrients replenished as needed. The additional nutrients in the water are organic and naturally-occurring since they don’t have to spray pesticides or herbicides in their controlled warehouse environment, Faye said.

The number of greenhouse farms has more than doubled since 2007, according to the 2012 U.S. Department of Agriculture Census of Agriculture. Some hydroponics advocates see the practice as a solution to a global food and water crisis.

“I don’t think it could take over the farming industry entirely because of the types of plants and vegetables people want to eat,” Faye said. “But I definitely think it could make a dent in the farming industry and make its place and replace certain types of farms for a more efficient and, in some cases, less expensive system.

Editor’s note: This story was produced for Cronkite News in collaboration with the Walter Cronkite School-based Carnegie-Knight News21 “Troubled Water” national reporting project scheduled for publication in August. Check out the project’s blog here.

Downtown Restaurants Growing Ingredients Right On-Site

Downtown Restaurants Growing Ingredients Right On-Site

By Todd Lihou | August 10, 2017

Michael Baird, left, of ESCA Gourmet Pizza + Bar, and Eric Lang of Zipgrow Canada, in front of the farm wall located on the ESCA patio.

CORNWALL, Ontario – A pair of downtown restaurants have partnered with a local firm to offer fresh products grown right on-site for hungry customers.

That’s right – the food is being grown on-site…in some cases right beside your table.

Truffles Burger Bar and ESCA Gourmet Pizza + Bar have partnered with Zipgrow Canada and installed a farm wall at each location.

The self-contained vertical gardens are currently growing kale and basil, which is used in food-preparation at both restaurants.

So far the response from patrons has been two thumbs up.

“Our kitchen love it, the staff love it and when we pick from it customers ask about it on the patio,” said ESCA’s Michale Baird. “And it’s fresh.

“The first pesto we made with it, the response was incredible. And it was stuff that grew 20 feet away from where it was being prepared.”

Eric Lang of Zipgrow Canada said his company, which specializes in small systems to grow in your home as well as full-scale commercial farms for warehouses, said the items grown in the farm walls can be customized and tailored depending on the time of year and foodstuffs being prepared.

“We can put in some of the vegetables that like it a little cooler. We can go right up until it is frosty,” he said. “We sell all over the world, but we are from Cornwall and we love these kinds of partnerships locally.”

Stop by Truffles and ESCA this summer and fall to enjoy some delicious offerings made with products grown right on-site.

This Company Wants to Bring Soil-Free Farming to Restaurant Kitchens

Hydroponics have allowed garden vegetables to grow in novel places—from a pillar inside a Berlin grocery store to a veritable skyscraper of plants in Singapore.

This Company Wants to Bring Soil-Free Farming to Restaurant Kitchens

by Cathy Erway • 2017

Hydroponics have allowed garden vegetables to grow in novel places—from a pillar inside a Berlin grocery store to a veritable skyscraper of plants in Singapore. The fast-growing, soil-free farming method has been well-embraced in urban areas to produce crops using less water and space, since the plants are grown in a nutrient water solution, rather than in-ground. But rarely is it done within some of the buzziest places for the farm-to-table movement: a restaurant.

The team behind Farmshelf hopes that will soon change, and recently debuted three indoor hydroponic growing units at Grand Central Station’s Great Northern Food Hall. There, the chefs at the busy food market’s Scandinavian restaurant Meyers Bageri reach into the glass-walled cubicles to pick lemon basil for a garnish on their zucchini flatbread, and nearly a dozen varieties of baby lettuces are plucked for salads at the neighboring Almanak vegetable-driven café. And, as it would appear on recent visits, curious bystanders peer through the glass, agape at the billowy mixture of herbs and greens, illuminated by a ceiling of LEDs. Unbeknownst to the casual observer, the units are also outfitted with five cameras along every shelf, so that the Farmshelf team can monitor the plants’ progress from afar and adjust the system via a web application.

“The more plants we grow, the smarter we are about plants,” said Jean-Paul Kyrillos, Farmshelf’s Chief Revenue Officer. He explained that through their data collection, Farmshelf can optimize the growth and flavor of any plants that a client may want. “This is for someone who doesn’t want to be a botanist, or farmer. The system is automatic.”

“Plants can grow two to three times as fast using 90% less water than traditional in-ground farming”

That’s why Farmshelf hopes its units will be a boon for restaurants serving greens galore. Founded in 2016 by CEO Andrew Shearer, Farmshelf is just planting its roots in the New York City restaurant industry with its first partner, Meyers USA hospitality group. The startup was in the inaugural lineup of the Urban-X accelerator and is part of the Urban Tech program at New Lab. The company is looking to partner with more restaurants soon, and Kyrillos mentioned a restaurateur who was excited about the idea of placing a Farmshelf unit right in the dining room, as a partition.

Distribution is the last challenge of getting local food onto plates, and Farmshelf eliminates that entire process—no middleman, forager, or schleps to Union Square Greenmarket. Kyrillos is hopeful that the efficiency of hydroponics—where plants can grow two to three times as fast using 90% less water than traditional in-ground farming—will also convince restaurants of the value of placing such a system on-site. Then, there is the potential of growing ingredients that you could never get locally, like citrus; or mimicking the terroir of, say, Italy, through a special blend of nutrients and conditions within the units.

Green City Growers in Cleveland, OH, has a 3.25-acre hydroponic greenhouse. Photo by Flickr/Horticulture Group

With hydroponics, you can grow a plethora of vegetables, even root vegetables like turnips, carrots, radishes, but these take much longer, and thus not suited to the fast-paced restaurant environment Farmshelf is trying to service. Crops that take up a lot of space, like watermelon and pole beans, are also not ideal, as the point is for these systems to use space efficiently (though future designs of hydroponic units might be able to tackle this challenge). It's most cost-effective to grow delicate, highly perishable, expensive leafy greens than roots, which are quick to grow and easy to ship and store.

The possibilities seem endless. But, in an age when the small family farm is rapidly disappearing in the US—and faces further threat from a recent White House budget proposal that would eliminate crop insurance—would this technology take away business from local farms, which restaurants might otherwise buy from?

Hydroponics—The Future of Farming in Detroit?by Lindsay-Jean Hard

Kyrillos doesn’t see Farmshelf as a replacement for the local farmer. There are some six to eight months of the year where traditional farms can’t grow too many crops, so restaurants would buy leafy greens and other warm-season produce elsewhere. If anything, Kyrillos posited that it might chip away at business from some of the bigger food distributors.

But time will have to tell what best works for the soon-to-be users of Farmshelf. Right now, the company is hoping to sell restaurants at least three growing units to make a significant enough impact on its kitchen orders. Rather than leaving it at that, Farmshelf wants to work with restaurants through a sort of subscription-based service, supplying seeds for crops that the restaurant would like to grow and monitoring the growing process consistently. Could a chef go rogue, and use the unit to plant and harvest whatever, whenever he pleased? Perhaps—but that wouldn’t really be taking advantage of the full product, which the team estimates might cost around $7,000 per unit (a medium-sized restaurant might need three units, at $21,000), which would pay off in ingredient costs.

And how about home chefs? When will average consumers be able to place Farmshelf inside our cramped, outdoor space-free apartments? That’s in the vision for Farmshelf someday. Not just homes, but school classrooms or cafeterias could be future sites of these hydroponic shelves, Kyrillos suggested, offering an easy, indoor way to connect youngsters to the food on their plates. “Imagine children were watching food grow, all the time.”

TAGS: HYDROPONICS, TECHNOLOGY, ENVIRONMENT, GRAND CENTRAL

Shenandoah Growers Opens Texas Indoor Production Facility

Shenandoah Growers Opens Texas Indoor Production Facility

July 13 , 2017

Virginia-based organic culinary herb grower and producer Shenandoah Growers (SGI) claims it is “set to transform the distribution of highly perishable produce”.

Through a proprietary combination of automated greenhouses and indoor LED vertical grow rooms to produce more than 30 million certified organic plants per year, SGI has now brought a third indoor growing facility online.

The new facility, located in Texas, is the latest component of SGI’s innovative hub-and-spoke farming and distribution system, and only the most recent step in the company’s three-year, multi-million-dollar nationwide expansion of indoor farming.

The group claims the system is quickly scalable for market growth, allowing Shenandoah Growers to “locally deliver certified organic superior flavor and shelf life at a fraction of the capital cost of other indoor farms”.

“This indoor farm, and the two others in our system, are critical elements of how Shenandoah Growers is transforming the way perishable produce is grown and distributed,” SGI CEO Timothy Heydon said in a release.

“With the integration of our modular indoor growing technology into our existing national footprint, we can grow amazing certified organic produce that delivers fresh flavor to consumers in a sustainable way, minimizing inputs of water, bio-media, land resources, and food miles.

“We are proud to be a part of transforming agriculture production and distribution for the future.”

SGI’s Rockingham, Virginia farm complex serves as the eastern hub of a nationwide growing system, and with a farming and supply chain platform spanning the country, the group claims its indoor farms cover the Mid-Atlantic, Midwest and South Central market.

The group continues the expansion of its farms, greenhouses and the implementation of an indoor farming hub and spoke system on the West Coast, with completion expected in 2018.

Vertical farms: "Making Nature Better"

Vertical farms: "Making Nature Better"

PORTAGE, Indiana -- Do not be confused by the drab facade of the warehouse in this Northwest Indiana industrial park. It's a farm... and it could well be the future. They're called "vertical farms" -- The entire operation is indoors, and it's a trend that could turn urban areas into agricultural hotbeds.

Workers at the Green Sense Farms warehouse in Portage, Indiana.

CBS NEWS

You'll find arugula and parsley, basil, kale and other greens that grace our plates.

"We are growing nine varieties of lettuces,'' said Robert Colangelo, the founder of Green Sense Farms.

Or you could call him Mr. Salad.

Bob Colangelo CBS NEWS

"I guess. I'll take that. I could be called worse," says Colangelo.

This is how he does it, with a pink light from a light-emitting diode, or LED

"It gives you a very concentrated amount of light and burns much cooler. And it's much more energy efficient," says Colangelo.

No sun? No problem.

Researchers believe plants respond best to the blue and red colors of the spectrum, so the densely-packed plants are bathed in a pink and purple haze. They're moistened by recycled water; bolstered by nutrients; and anchored in a special mix of ground Sri Lankan coconut husks.

"We take weather out of the equation," says Colangelo. "We can grow year round and we can harvest year-round."

This abundance keeps the prices consistent year-round at local groceries.

Scott Hinkle, a local chef, says the sunless harvest tastes great. Hinkle shows off a "blossom salad" he serves which can include watercress, micro-arugula or kale.

With less water and fertilizer, fewer workers and no gasoline, it's more economical to grow greens this way than on a traditional farm.

Since there are no bugs, there's no need for pesticides. No weeds, so no need for herbicides.

And Colangelo really knows his plants. He says workers play classical music to create happy vibes for the flora.

Is there a composer the plants prefer? If it's Metallica, we don't want to eat it.

As to whether he's cheating nature...

"We're making nature better," says Colangelo.

High-Tech Indoor Farm Nabs $20 Million in New Funding

Bowery, an indoor farming company that deploys a lot of high-tech solutions – including propriety software systems, robotics and monitoring plants via machine learning – announces it has secured a Series A funding round of $20 million from several investors, including General Catalyst, GGV and GV.

High-Tech Indoor Farm Nabs $20 Million in New Funding

JUNE 14, 2017 09:02 AM

Bowery’s crops are planted indoors in vertical rows and meticulously monitored, “capturing a tremendous amount of data along the way,” according to the company’s website.

© Bowery

By Ben Potter

AgWeb.com

Bowery, an indoor farming company that deploys a lot of high-tech solutions – including propriety software systems, robotics and monitoring plants via machine learning – announces it has secured a Series A funding round of $20 million from several investors, including General Catalyst, GGV and GV.

“Shaping the future of food requires re-imagining the food supply chain from seed to store,” according to Spencer Lazar, partner with General Catalyst. “The Bowery team is pioneering technology that will move the entire agriculture industry forward. We are proud to be in their corner.”

Bowery uses hydroponics practices it says uses 95% less water and is more than a hundred times more productive comparable to the same footprint of land of traditional agriculture. The company also calls the leafy greens it grows “post-organic” – that is, pesticide-free and grown in a completely controlled environment.

Perhaps most importantly – the food tastes good, Lazar says.

“Their produce tastes delightful,” he says. “Their farm economics are exciting, and the conscientiousness of their approach is inspiring.”

Bowery’s crops are planted indoors in vertical rows and meticulously monitored, “capturing a tremendous amount of data along the way,” according to the company’s website. “We’re able to remove the age old reliance on ‘eyeballing.’ We can give our crops exactly what they need and nothing more -- from nutrients and water to light.”

The company sells its produce to nearby restaurants and Whole Foods stores in and around New York City.

Bowery’s CEO, Irving Fain, says he’s thrilled by the level of support the company has received so far. In February, the company announced a separate $7.5 million in total venture funding had also been raised.

The vertical farming market has proven a lucrative one in recent years. According to one market research report, the global vertical farming market is expected to grow to $5.8 billion by 2022, with an annual growth rate of nearly 25% between 2016 and 2022.

Nebraska Man’s Mushroom Growing Hobby Becomes A Business

Fence Post courtesy photo |

Nebraska Man’s Mushroom Growing Hobby Becomes A Business

At a farmers market in Lincoln, Neb., Ash Gordon talks to consumers about mushroom varieties.

They look like sculptures: mushrooms with exotic names like Lion's Mane and Blue Oyster. And they flourish inside a nondescript warehouse located near the airport in Grand Island, Neb. Nebraska Mushroom is an indoor farm where unusual varieties of the fungi are pampered and fussed over from colonization to harvest.

Ash Gordon is the mushroom man.

"The varieties we grow are different than what you normally find at the grocery store," said Gordon, the founder of Nebraska Mushroom. "They have different flavors and textures. Everybody can find a mushroom they like because there are so many options."

Growing up in Nebraska, Gordon spent time as a boy foraging for mushrooms along the Platte River near his Grand Island home. He even bought a mushroom field guide from the Audubon Society to bolster his hobby.

As an adult, Gordon worked as a kidney dialysis technician. Then, at age 27, he developed arthritis that was painful and debilitating. Research into the healing properties of mushrooms led him to include more mushrooms in his diet through tinctures, extracts and teas. With other lifestyle changes, his arthritis symptoms eased and his mushroom hobby grew into a business.

For Gordon, growing mushrooms is both a science and an art. He follows strict procedures to colonize and produce a mushroom, lessons learned by reading books and studying information found on the internet. The art of growing mushrooms has developed through trial and error.

"There's a lot of science in it but I would say the art is in manipulating the conditions so that the mushroom knows it's time to fruit, and then will produce for us," Gordon said.

COLONIZATION

The process begins with mycelium, a culture of mushroom tissue stored in a tube called a slant. A pea-sized piece of mycelium is transferred to a petri dish to colonize. The resulting mushroom culture is mixed with sterilized grain and eventually transferred to bags of sawdust.

One pea-sized piece of mycelium makes about eight grain jars. One jar translates into five master bags and each master bag expands into 30 bags of substrate, where the mushrooms begin to fruit.

The bags are moved to greenhouse-like structures where they begin to react to their environment in different ways. The grow rooms are warm and humid, but the air conditioning runs year round. Even in the winter, Gordon said the mushrooms generate so much heat as they grow they can actually start to cook if the temperature gets too high.

The growing process varies according to the mushroom. Gordon cuts holes in the bags of Oyster mushrooms, allowing them to recognize the fresh air and begin to grow out of the bags. Shitakes go through a more dramatic fruiting process.

"The Shitake mushrooms go through a popcorn stage where they really bubble up and blister. They break through the bags and turn completely brown," Gordon said. "The Oysters stay white the whole time."

Mushrooms also have different personalities: They can be small and delicate or troublesome and finicky. For example, Gordon keeps close watch on a particular strain of Shitake mushroom because if he overfeeds it, the mushroom starts to make mutants. If the bag isn't flipped over, the mushrooms start growing down, under the racks. In general, Gordon said, the mushroom "can be a pain sometimes."

AFTER THE HARVEST

After harvesting the mushrooms, Gordon packages the crop for sale at farmer's markets, grocery stores and co-ops. He also supplies a few restaurants with his fresh mushrooms.

Summer is the busiest time for Gordon. The mushrooms grow so fast, he goes through periods where he is constantly harvesting. Late nights in the greenhouse are followed by early mornings at the farmer's market. In spite of the long hours, Gordon enjoys introducing consumers to mushrooms. He sees a strong future for mushroom farming because consumers are more interested in buying fresh food and they want to know more about where their food comes from and how it's grown.

"The best part is people's reactions," he said. "They don't realize how many types of edible mushrooms there are, the different colors and textures. I like talking to the public and educating people about the mushrooms and how to use them."

Gordon never stops learning and thinking about what's next. He produces and sells mushroom extracts and dried mushrooms. Leftover mushroom substrate is dumped in a pile where, over time, a rich compost develops that can be used to improve the quality of soil for vegetable gardens. Gordon wants to expand his business to include creating products that will help other farmers get into the mushroom business, from providing information to selling mushroom cultures.

"People are interested but maybe they don't have the space or the time or the knowledge," Gordon said. "I'd like to give people more affordable, easier options to help them get started." ❖

— Mary Jane Bruce is a freelance reporter for The Fence Post. She can be reached at mbruce1@unl.edu, or on Twitter @mjstweets.

Scotland's First Vertical Indoor Farm To Be Operational by Autumn

2017 |Arable,Crops and Cereals,News

Scotland's First Vertical Indoor Farm To Be Operational by Autumn

Scotland’s first vertical indoor farm to be operational by Autumn 2017

An indoor vertical farm in Scotland will be completed in the next few months, the company behind the project has said.Intelligent Growth Solutions (IGS), the Dundee-based company, says it will make vertical farming - the process of producing food on vertically stacked layers indoors - commercially viable through reduced power and labour costs.The modern ideas of vertical farming use indoor farming techniques and controlled-environment agriculture (CEA) technology, where all environmental factors can be controlled.These facilities utilise artificial control of light and environmental control, such as humidity, temperature and gases."Vertical farming allows us to provide the exact environmental conditions necessary for optimal plant growth," said Harry Aykroyd, the CEO of IGS."

By adopting the principles of Total Controlled Environment Agriculture (TCEA), a system in which all aspects of the growing environment can be controlled, it is possible to eliminate variations in the growing environment, enabling the grower to produce consistent, high quality crops with minimal wastage, in any location, all year round."'Most advanced technology'Omron, an automation company collaborating in the project, said it uses the most advanced technology to solve humanitarian needs.Their Field Sales Engineer Kassim Okera said: "Omron's unique integrated product offering and Sysmac platform combined with extensive market experience, underpin the most innovative vertical farm in the UK which has the potential to be the first vertical farm in the world that is economically viable."Professor Colin Campbell, Chief Executive of the James Hutton Institute commented: "

We are delighted to see how well the work on IGS' indoors growth facility at our Dundee site is progressing."This initiative combines our world-leading knowledge of plant science at the James Hutton Institute and IGS’ entrepreneurship to develop efficient ways of growing plants on a small footprint with low energy and water input.

"Singapore is also considering a huge vertical farm. The city is planning a 250-acre agricultural district, which will function as a space to work, live, shop, and farm food.

The Opportunities and Challenges of Building a Rural Agtech Startup

Startup activity in the US is typically concentrated on the two coasts, particularly in California, New York, and Massachusetts, and agtech startups are no different. In 2016, agtech startups in those three states raised 73% of all investment dollars during the year. There are, however, several startups cropping up in America’s rural regions, which can make a lot of sense considering where many of their customers will be

The Opportunities and Challenges of Building a Rural Agtech Startup

JUNE 21, 2017 LOUISA BURWOOD-TAYLOR

Startup activity in the US is typically concentrated on the two coasts, particularly in California, New York, and Massachusetts, and agtech startups are no different. In 2016, agtech startups in those three states raised 73% of all investment dollars during the year. There are, however, several startups cropping up in America’s rural regions, which can make a lot of sense considering where many of their customers will be. And there are some leading investors moving away from Silicon Valley to find investments, such as AOL founder Steve Case who’s staking a claim on rural entrepreneurs with a new $525 million fund focused on investing outside of New York and San Francisco.

Lisa Benson from the Farm Bureau introduced me to three rural agtech startup entrepreneurs that took part in the Farm Bureau’s Rural Entrepreneurship Challenge last year: Dan Perpich of Vertical Harvest Hydroponics, which is an indoor agricultural startup based in Anchorage, Alaska; Martin Bremmer from Windcall Manufacturing in Venango, Nebraska, who has developed a miniaturized grain combine called the Grain Goat; and Albert Wilde, from Wild Valley Farms in Croyden, Utah, who is producing sheep wool fertilizer from waste wool.

Applications are now open for the 2018 Challenge with a deadline of June 30, 2017, and the opportunity to win $145,000 worth of prizes. You can find out more and apply here.

In this week’s podcast, I speak to the three rural agtech startup entrepreneurs to find out more about the challenges they face launching agtech products from their respective rural bases.

Here’s an abridged transcription of the podcast.

AgFunderNews

The Opportunities and Challenges of Building a Rural Agtech Startup

Dan Perpich: I am the founder of Vertical Harvest, and we are based in Anchorage, Alaska. We started two and a half years ago, and we started designing and producing and marketing commercial hydroponic systems installed in 40-foot shipping containers, and the reason we did that is because food prices in Alaska and Canada and the North, the Arctic, are out of control. And we thought there was an opportunity to give people the means to farm locally and produce their own food locally and that would be a good market and a valuable product to people. And here we are two and a half years later, and we’re just happy to still be here.

Albert Wilde: I live in Croydon, Utah, and the company that I’ve started is called Wild Valley Farms. We do all sorts of compost, soils, landscaping materials and that, but the product we’ve developed is a natural organic fertilizer that will fertilize for a whole season, and it’ll retain water, reducing the amount of watering by about 25%, and it’s made from waste wool from sheep.

I’m a sheep rancher, and we have 2,800 sheep and 300 head of cows, which is why we started with doing the compost to be able to manage animal waste and make a value-added product for consumers for their gardening and what not. And then when we found that wool was so high in nitrogen that we started working towards trying to make the wool a useable product for an end consumer. So we pelletized it, and we’ve been selling the wool pellets to nurseries and greenhouses and for commercial use. They take the wool pellets and mix it in with their hanging baskets or potted plants that they’re selling to consumers. And then we also bag up the wool pellets and sell directly to consumers and through distribution channels.

Martin Bremmer: I’m in Southwestern Nebraska, and our company’s called Windcall Manufacturing and our first product is called the Grain Goat. It’s essentially a grain combine that’s handheld because it’s very tiny. The purpose of this combine is so that you can sample small amounts of grain, small varieties, rapidly, and then use the onboard moisture meter to tell you what the moisture content of the grain is, enabling you to determine whether or not that field that you just sampled is ready to harvest.

LBT: Thinking about all the startup activity that’s taking place in agtech in San Francisco and New York that you’re all aware of, how do you think building a startup in a rural region compares?

Bremmer: That’s a tough question, but what I’m familiar with in terms of raising raising capital is that there’s always more zeroes attached to the project [on the coasts]. And so there’s different [investor] groups that seem to be targeted by the startups, and the VC groups are pretty well established and have great reputations. They do some incredible due diligence, and when I think about my own personal experience, when we’re doing fundraising for Wind Call Manufacturing, it’s scaled back quite a little bit.

The same process goes on it’s just scaled back in the scope of expectations, which is a huge advantage for us because early stage funding is a little more easily accomplished because there’s more understanding of the dynamic with small companies like ours: our investors understand that the zeroes are going to be smaller, the growth is going to be slower, and they don’t have these rapid slingshot unicorn dreams of what’s going to happen with your company, they get that this is, I don’t want to call it a niche market, but it’s an ag market, so it’s not a mainstream US market. And so I’m not having to redirect their focus and expectations, they already understand that.

Wilde: Most ag startups are building more of a legacy business. They’re focusing on, “I’m gonna build something that helps with the industry that I know and love, and I’m gonna keep this,” more. Whereas a lot of I think the tech side of things, people get into it and there’s not a homegrown part of it. So I guess it’s just, I came up with this technology, and I’m putting it out there, and I don’t care who buys it or how fast and it can go. It can go away from me.

And I think from what I’ve seen with a lot of ag startups is they feel more like they’re building this because they saw a need for something that they love and they want to grow and keep it that way.

And so with different investors, they have to know what your end goal is before they invest in you, and as Martin said, the expectation with a legacy company is much, much lower. The profit, returns… because you’re not looking to come up with an idea and just sell it. You’re looking to come up with an idea and build it.

LBT: Are your investor bases generally local investors, or have you attracted investment from across the country or even the globe?

Wilde: We have a huge potential for growth, and we have some very large companies that are looking to license our product that’ll put it out to a wide distribution for consumers, but all of the investment came from myself or family or partners. And the reason is, I’ve got two partners that have put in $2 million worth of assets, and then for myself I’ve got a ranch and farm, so I’ve received an ag loan from this lender at a 3.8% interest, which I mean is really cheap, but that’s because I have some ag assets that they’re willing to loan that sort of money on. Most investors like a venture capitalist, you tell them that you’ve got funding at 3.8% or 5% or whatever, they know that you’re not interested.

LBT: Dan, how have you funded Vertical Harvest?

Perpich: We’re self-funded, so we put our own money in to start our company, and as we’ve started growing revenue we’ve been able to reinvest and continue development. We’ve been very lucky in that regard. Going back to your first question Louisa, it’s important to remember that farmers are by definition entrepreneurs; a farmer owns and operates his own business, and they may start by getting family loans or owner-funded farms by younger farmers, but I think it’s quite important to remember that. Up here in Alaska, I’d say we’re probably one of the more rural places in the US — some would argue quite remote — and I think it does complicate fundraising a little bit, but there’s still money in the system and I think we’ve got a lot of benefits from the connectivity of today’s world. I may not be able to go down to the row of offices if I’m fundraising but we’ve got email, we’ve got Skype, we’ve got conference calls. I think that stuff has value to us and also has value to our customers.

LBT: If you were to seek external capital where do you think you’d go first? Would you look for local Alaskan investors as the first point of call?

Perpich: My thoughts are that we need to get a strategic benefit out of any investment that we take. If we want just money, we can go to a lot of different places just for money, but we look at what our goals are that we’re trying to accomplish; operationally how do they fit in, can they connect with customers, can they lead a round and bring people to the table?

Just to frame it, we’re in the process of putting together what we’re calling a Series A to grow our workforce, so all those questions are really near to us right now. When we talk to investors we ask them, are you going to bring us sales people, are you gonna bring us customers, are you going to bring us other investors?

I think it’s important that we don’t just go and take the first guy that’s got money because from my experience the geography isn’t just limited to the West Coast, the geography is North America, the world. And there are quite a few people out there, and so if we just go to the guy down the street and he connects me to more people in Alaska, what value does that bring to me?

Bremmer: I’ve got a question for you Dan, just because where you live you could attract Canadian investors just as easily as US investors, so does that throw an added layer of complexity if you pulled in some Canadian interest?

Perpich: You know it does, but that’s all a solvable problem. If a guy from Canada wants to invest in my business, there are some questions such as are we gonna open an office there? Are we gonna do the investment in Canadian dollars or US dollars? You know, he’d have to answer some questions about mitigating currency risk because the Canadian dollar goes up and down against the US dollar. So there are questions but I think those are all solvable problems and quite frankly, if you know a guy who’s Canadian and wants to invest in me, I mean, you want to shoot us an email and connect us? [laughs]

Bremmer: I’ll send him your way. [laughs]

LBT: So, what would you say have been the main challenges that you’ve faced in launching your businesses and getting them to where they are today? And, what do you foresee as being the challenges going forward, if those challenges shift and change?

Wilde: So I think the most difficult part of being an ag startup is actually developing the product itself. I mean, I think each of us has a product that has to be manufactured, a physical thing that you’re actually building, and for myself, like I said my partners had invested $2 million, which is all in the equipment to be able to produce the product that I have. That’s a little different than, like, other tech things, startups, where it’s more of a technology and not just a physical product itself.

And so trying to get people to believe in you, or to believe in your product or even to know why it’s better or why it’s going to help before you have a real prototype, makes it very challenging that way. And I think that’s probably one of the most challenging for an early, early stage ag startup. Then, once you get your prototype and you start to build those prototypes, it’s being able to put it into more of a mass production and then like Dan mentioned, the salesforce; trying to get a salesforce out there to be able to sell your product so you can take in the materials you need to build you product but also have someone out there selling it so that your inventory doesn’t eat you alive.

LBT: What would you say are the benefits to you being based in Croydon, Utah? Are you near your customer base, or is it near the source of your product?

Wilde: I don’t know if there’s all that much advantage to it, [except] being connected through agriculture. As a sheep producer, I’ve been invited to a number of the different wool grower conventions around the country to inform them, the other sheep producers, about my product and what I’m doing in actually buying waste wool from them and entering a value added product. And that’s a huge benefit over anyone else [that might produce this product], the greenhouses or whatever, they’re like, “Oh, we really like this product, maybe we could do it,” and I’m like, well, okay, but for them they’re gonna have to go to a wool warehouse where the cost is going to be much more expensive, and I can go directly to buy the materials. So that’s a huge advantage just being in ag in that way.

Bremmer: There are two main challenges that jump into my forethoughts. One is because we’re a new product with a new market, we really have to push hard and shovel a lot of coal into the fire for what we call educational outreach – most folks would just call it flat-out marketing – we need to get our product in the mind of all our potential customers just because we don’t have competing products, and so we’ve spent a lot of our time educating farmers as to the advantage and the asset of purchasing our product to make their world a little bit easier and make some savings actually happen on their balance sheet. And so the huge challenge there is just because of the time, the energy, and the dollars it takes to execute that effort.

And then our number two challenge is keeping our cost of goods down. Because we’re manufacturing a mechanical device, the cost of goods can always come down a little bit. And it’s nice where we live; we’re in Nebraska so we can take advantage of the multitude of manufacturers in Nebraska, Kansas, and Colorado, where we can actually make them compete against each other to keep our cost of goods down when we’re subbing out a lot of parts. So that’s a huge asset to us because we live in a low cost of living part of the US and so the manufacturers in a 500-mile circle from our home base actually turn out quality products for much, much less than if we were on either coast and using the same skill set manufacturers. So huge advantage there but still driving that cost of goods down in a big deal for us; being a startup, we cannot make purchases in volumes that would really make a difference, not yet at least. And so as soon as we drive some sales further and faster, then maybe we can take advantage of that.

LBT: To go back to your first point Martin — the bit about the adoption rate — this is something that I think a lot of investors look at as being particularly challenging in agriculture, because with a lot of products you’ve only got one growing season a year, so one time for the farmers to test the product or even for you to iterate on the development of your product.

I’m also wondering how much behavioral change is required for them to adopt your technology and use that in the field, before harvest. What is your sense on that and how quickly that could happen?

Bremmer: Behavioral change is paramount for what we’re trying to sell, because we’re actually asking grain farmers to change their harvesting habits and I have to kind of draw out farmers in general, but especially grain farmers because that’s who I’m familiar with; that’s an unusual market on a good day.

Because we’ve got a group of smart people, sometimes they’re highly educated, sometimes they’re not, but they’re very traditional, and they’re very family-based businesses, and so we have lot of customers who run multi-million dollar family corporations with very little marketing education and business marketing education or just overall most farmers aren’t MBAs. And they like it that way, so they do everything by the gut, or they do everything traditionally. And so it’s a bit of a bullish kind of audience, where we have to show up at the trade show and get these folks to open their minds a bit and say, “You need to change a habit that you’ve had for the last 30 years, to improve your balance sheet.” And I can watch their eyes glaze over for a minute, and then once I get past that, they start thinking a little bit and then their business mind, their common-sense mind, kicks in, and then I have them because they start to realize oh, there is a change.

But it’s funny how you can split that demographic down into age, because anybody 55 and older, they’re pretty resistant to it. But between 30-55, they’re open to it, and they think about it, but younger than that they haven’t really had enough experience on the family farm to really understand the impact of a tool like what we are selling.

LBT: What is it that suddenly gets through to them? Are you throwing figures at them and saying that you’ll actually help them increase their revenues by x percent, or whatever?

Bremmer: The way I crack through that force field that they’ve got is by using their Achilles heel. The one thing that you can appeal to a farmer with is, what are their expenses, and is there a way that you can minimize their expense?. So that’s our biggest asset from a marketing point of view; we’re able to get the farmer to actually recount to us a story where they wasted a lot of time or a lot of money on a particular season, and by using our tool they would have eliminated that entire scenario, and that’s what gets me in the front door of their mind so that they can realize, oh my gosh yeah, maybe this is kind of an arcane method that we’ve been doing for years. Maybe there’s a new tool like the Grain Goat that avoids that risk. And so now we’ve got the cost savings that makes them go okay, I can see the value of this.

LBT: Dan, tell me about your challenges in getting Vertical Harvest Hydroponics set up?

Perpich: Oh, man, Louisa, I don’t even know where to start on that question [laughs]. You know I’ve got to say I figure if you google, “Basic entrepreneur mistakes,” we’ll probably put a checkmark next to just about every single one of them.

There a lot of pitfalls that you can just jump into, a lot of black holes and time wasting. I think our biggest challenge is that our product is sort of in a lot of ways a new paradigm shift. A lot of people are used to the idea of food being grown outside of Alaska, far away, and so to have technology that can do it at places where – I mean we’ve got the first hydroponic farm above the Arctic Circle, and it was growing food successfully for the market at 50 below zero this year. Kudos to our customers for being the first people to bring the technology out there because it’s a risky and daunting task. And I think the challenges show the customers that not only is it possible, it’s not only something you read about in a science publication or a science magazine, but it’s actually real and you can do it.

The challenge I guess is showing people to the point where they don’t just see it and think, “Wow that’s a cool thing,” but to the point where they see it, and they say, “That’s a cool thing, and I want it, and I want to do that, and that’s how I want to support my family.”

It’s definitely one of our challenges for sure. And going back to what I think Martin had mentioned about when you hit a certain age demographic, a lot of the farmers are maybe not as interested. We’ve definitely seen that as well, sort of the older farmers that we’ve dealt with, the guys in their 50s and 60s, their sort of note is, “That’s very cool, and I think it is the future, but at my age, I’m not up for an adventure.” And so we’ve definitely seen most interest from the younger farmers, the next generation of farmers. And if there was anything that I could make a very brash pitch about, I’d say what would be helpful for those guys is if they had access to cheaper money, because what we’ve seen with our technologies is that they’re very new, and the low-risk institutions like banks, traditional financing sources, don’t want to finance them yet, so they’re left with more expensive sources of money. And that’s gonna change, we hope, but we’d like it to change faster of course.

LBT: So who are your main customers?

Perpich: Right now they’re either current farmers and people that want to be farmers. And a lot of what we’ve found in Alaska anyway is the people that want to be farmers are corporations that have employees in these communities and want to grow their revenue streams, or they have a local interest in the community, and they’re willing to take the risk because of the benefits to the communities. Definitely, people are on the lower edge of the age demographic; I’d say 20s-40s in that range.

LBT: And is the fact that how you’re growing the produce indoors, organically, or non-GMO or pesticide free, etc: is that a big draw do you think for some of the farmers? To be able to get some of those price premiums?

Perpich: You know, it’s very attractive to farmers in the lower 48 – just as a side note lower 48 is what we call all of you guys. But what you’ve gotta understand is that a lot of these guys, they’re seeing just lettuce, for example, that’s three weeks old, it’s four weeks old, it’s well on its way to spoilage, and it gets sold in these communities, and it’s all they have. I mean they don’t have anything else.

So, for them, they like the idea that it’s organic or that it’s non-GMO or that it’s hydroponic, but they really care that it’s fresh and that they know the farmer personally. I mean these are communities of a couple of thousand people, and it’s not uncommon for them to knock on the door and ask for a tour and normally the farmer will give them a tour because he’s known them for 20 years.

I’d say that’s more of the big selling point for the customers in Alaska anyway.

LBT: How many of your containers are out there now?

Perpich: We’ve sold six, so, we’re young. We’re early stage.

Listen to the rest of the podcast to find out what these entrepreneurs’ goals are over the next few years, and for more insights from the conversation.

Alliance Greenhouse Uses Geothermal Heat To Produce All Year Long

Alliance Greenhouse Uses Geothermal Heat To Produce All Year Long

- TORRI BRUMBAUGH Staff Intern | torri.brumbaugh@starherald.com

- Jun 10, 2017

Russ Finch shows off his tango mandarins, a hybrid that contains no seeds.

Torri Brumbaugh/ Star Herald

ALLIANCE — Members of the Nebraska Master Gardener Program anxiously wait as Alliance’s Russ Finch cuts an orange. While the excitement for a simple orange seems strange, this orange is different. It is a 3-year-old orange that Finch grew in his own backyard.

Finch was simply a mail carrier and farmer in Alliance, until 45 years ago when he started experimenting with heating houses with geothermal heat. Fifteen years later, he began using the geothermal heat to improve greenhouses.

Geothermal heat produces heat from the ground. A singular heat source dispenses heat into a tubing system that runs under the ground of the greenhouse. The heat is constantly circulating and reused to create the perfect environment for the greenhouse. This means that in Finch’s greenhouses, he can grow any tropical or subtropical plant that he wants.

Russ Finch leads members of the Nebraska Master Gardener Program into a newly builty greenhouse.Torri Brumbaugh/ Star Herald

His personal greenhouse is filled with numerous plants, nine varieties of southern grapes, pomegranates, 13 types of citrus fruit and much more. His citrus fruits include Eureka lemons, Meyer’s lemons, Cara Cara oranges, Tango mandarins and Washington naval oranges.

At 78-feet long, Finch’s greenhouse is 24 years old and the first one he created.

Around three years ago, Finch began to sell the frames, systems and equipment for his geothermal greenhouses with his business, Greenhouse in the Snow.

Compared to his personal greenhouse, the new greenhouses are much more efficient.

The new greenhouses are at least 96 feet long. They also include shelves on one wall to grow ground vegetables and fruit. The other side of the greenhouse is often designated for trees.

“We just put everything in it to see if it’ll grow, and almost everything did,” says Finch.

Finch’s geothermal greenhouses appear to be much more efficient than the standard greenhouse.

To run his personal greenhouse, it costs Finch up to 85 cents a day. Other geothermal greenhouses, like the one at Alliance High School, cost up to 97 cents a day. A geothermal greenhouse only costs around $200 to run in the winter, compared to the $8,000 it would cost with a regular greenhouse.

In his greenhouses, Finch can also produce more product than planting outside.

A greenhouse can produce 14 tomatoes to every one tomato that average farming produces, while with other crops it is often 50-1, Finch said. Weather is a big factor in this because greenhouses have a controlled environment.

Here is a prototype of Russ Finch's newer greenhouses.

Torri Brumbaugh/ Star Herald

The profit produced by the geothermal greenhouses is a great benefit as well.

Finch said, “Each tree needs an 8-foot circle and will produce 125 pounds of fruit. If a pound is usually $3.50 at a farmers market, that makes each 8-foot circle worth $430.”

According to Finch, most young people do not want to get into agriculture because they believe it is too expensive. Little do they know, a single 3-year-old tractor with four-wheel drive is the same cost as putting up nine of Finch’s greenhouses. So for those looking to get into agriculture, Finch highly suggests going geothermal.

Member of the Nebraska Master Gardener Program get the opportunity to explore one of Russ Finch's newer greenhouses outside of Alliance, Nebraska.

Torri Brumbaugh/ Star Herald

Greenhouses are efficient cost wise, but the newer greenhouses also include a key to helping with the extinction of bees.

Finch showcased an Australian beehive called Flow Hive. The hive would replace common beehives and take away the need for smokers, a device used to calm bees. Within Flow Hive, the hexagonal cells are already formed, so the bees do not need to create them with wax.

When the honey needs to be taken from the beehive, a key is used to break the cells and drain the honey. Finch claims that the new beehives would help kill less bees and hopefully, help the bee from coming extinct.

Finch has sold about 38 greenhouses and almost all of them have been used for commercial purposes. Nine states — including Alaska, South Dakota, Wyoming and Kansas — now have Finch’s greenhouses, along with two greenhouses in Canada.

The Federal Aviation Administration has just given the go for a greenhouse to be built at the Western Nebraska Regional Airport in Scottsbluff. The greenhouse will be used by the North Platte Natural Resources department. It is estimated that the greenhouse will be put in place in late spring.

With the success of Greenhouse in the Snow, Finch is very hopeful for the possibilities. He is trying to spread his geothermal heat across the globe to countries like Australia, Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Greece and South Africa.

According to Finch, all of the Midwest’s table citrus could be grown locally in greenhouses.

Lemons grow in Russ Finch's greenhouse.

Torri Brumbaugh/ Star Herald

For more information on purchasing a geothermal greenhouse, contact Finch at greenhouseinthesnow.com.

Indoor Farming Start-Up Plenty Secures $200m In Funding

Indoor Farming Start-Up Plenty Secures $200m In Funding

Posted By: News Deskon: July 19, 2017In: Agriculture, Environment, Food, Industries, Uncategorized

US indoor farming start-up Plenty has obtained $200 million in funding led by the SoftBank Vision Fund as it expands its agriculture model.

Plenty claims to be developing patented technologies to build a ‘new kind of indoor farm’ that uses LED lighting and micro sensor technology to deliver higher quality produce.

The company said the investment will boost its global farm network and support its mission of ‘making fresh produce available and affordable for people everywhere’.

As part of the deal, SoftBank Vision Fund’s managing director Jeffrey Housenbold will join the Plenty board of directors.

SoftBank Group Corp chairman Masayoshi Son said: “By combining technology with optimal agriculture methods, Plenty is working to make ultra-fresh, nutrient-rich food accessible to everyone in an always-local way that minimises wastage from transport.

“We believe that Plenty’s team will remake the current food system to improve people’s quality of life.”

Based in San Francisco, Plenty plans to build its farms near the world’s major population centres to produce GMO and pesticide-free produce while minimising water use.

Plenty CEO and founder Matt Barnard said: “Fruits and vegetables grown conventionally spend days, weeks, and thousands of miles on freeways and in storage, keeping us all from what we crave and deserve — food as irresistible and nutritious as what we used to eat out of our grandparents’ gardens.

“The world is out of land in the places it’s most economical to grow these crops.”

He concluded: “We’re now ready to build out our farm network and serve communities around the globe.

Urban Aquaponic Farmer and Chef Redefines Local Food in Orange County, CA

Urban Aquaponic Farmer and Chef Redefines Local Food in Orange County, CA

Heads of lettuce gain their sustenance through aquaponics channels at Future Foods Farms in Brea. Photo courtesy Barbie Wheatley/Future Foods Farms.

In a county named for its former abundance of orange groves, chef and farmer Adam Navidi is on the forefront of redefining local food and agriculture through his restaurant, farm, and catering business.

Navidi is executive chef of Oceans & Earth restaurant in Yorba Linda, runs Chef Adam Navidi Catering and operates Future Foods Farms in Brea, an organic aquaponic farm that comprises 25 acres and several greenhouses.

Navidi’s road to farming was shaped by one of his mentors, the late legendary chef Jean-Louis Palladin.

“Palladin said chefs would be known for their relationships with farmers,” Navidi says.

He still remembers his teacher’s words, and now as a farmer himself, supplies produce and other ingredients to a variety of clients as well as his restaurant and catering company.

Navidi’s journey toward aquaponics began when he was at the pinnacle of his catering business, serving multi-course meals to discerning diners in Orange County. Their high standards for food matched his own.

“My clients wanted the best produce they could get,” he says. “They didn’t want lettuce that came in a box.”

So after experimenting with growing lettuce in his backyard, he ventured into hydroponics. Later, he learned of aquaponics. Now, aquaponics is one of the primary ways Navidi grows food. As part of this system he raises Tilapia, which is served at his restaurant and by his catering enterprise.

Just like aquaponics helps farmers in cold-weather climes grow their produce year-round, the reverse is true for growers in arid, hot and drought-prone southern California.

“Nobody grows lettuce in the summer when it’s 110 degrees,” Navidi says.

But thanks to aquaponics, Navidi does.

Navidi also puts other growing methods to use at Future Foods Farms. He grows San Marzano tomatoes in a greenhouse bed containing volcanic rock (this premier variety was first grown in volcanic soil near Mount Vesuvius in Italy). Additionally, he utilizes vertical growing methods.

For Navidi, nutrient density is paramount—to this end, he takes a scientific approach in measuring the nutrition content of his produce. In the past, he and his staff used a refractometer, but now rely on a more precise tool—a Raman spectrometer. This instrument uses a laser that interacts with molecules, identifying nutritional value on a molecular level.

With a Raman spectrometer, Navidi measured the sugar content of three tomatoes—one from a grocery store, one from a high-end market, and one that he grew aquaponically. Respectively, measurements read 2.5, 4.0 and 8.5.

Navidi wants his customers to know about these nutritional differences, so he educates his Oceans & Earth diners through its menu and website. Future Foods Farms also offers internship opportunities to students from California State University, Fullerton. Interns conduct research and learn about cutting-edge ways to grow food.

Navidi believes aquaponics and other innovative growing methods can lead to a more robust local food system in Orange County. But he also sees some of southern California’s undervalued resources—namely, common weeds such as dandelion and wild mustard—helping the region become a major local foods player.

“We need more research on nutrients in weeds,” he says. “Dandelions and mustard are power weeds, and need little water.”

While these wild plants are important, they’re no substitute for policy. Navidi would like to see farmers in the county pay lower rates for water, and believes that a revised zoning code is needed for a county that is urban and becoming more so.

“Now, urban farming is happening all over,” he says. “We need changes to our zoning laws—politicians realize that.”

New zoning rules could help others in Orange County venture into aquaponics, something Navidi feels is necessary not only for the county, but for the country.

“For America to be sustainable, it needs aquaponics,” he says.

Ultimately, Navidi’s goal is to provide the best product possible, with an eye toward simplicity, health and wholesomeness.

“Any fine-dining chef is concerned with the quality of their product,” he says. “There’s nothing better than real food. I try to grow the most nutrient-dense tomato possible. Just add sea salt and black pepper—that’s all you need.”

Convention Center Plays Host To Urban Farm: Take A Look Around

Convention Center Plays Host To Urban Farm: Take A Look Around

2017

Tour the urban farm outside Cleveland's convention center

BY EMILY BAMFORTH, CLEVELAND.COM | ebamforth@cleveland.com

CLEVELAND, Ohio -- Look out of some of the windows of the Cleveland Convention Center, and you'll see greenery, dozens of chickens, lines of bee hives and three pigs.

It's a sight that brings Clevelanders on their lunch breaks or enjoying downtown during the summer months peering over the top of the building from the mall above, trying to sneak a peek at the animals below.

The farm is run by, and produces significant amounts of ingredients for, Levy Restaurants, the food service provider for the convention center. The project began more than three years ago with beehives, and has slowly grown to include raised beds, chickens and pigs.

Read more: Honeybees bring the sweetness of urban agriculture to Cleveland's convention center

The farm is part of the convention center's sustainability efforts. More than 50 percent of the trash from the the Global Center for Health Innovation and the convention center was recycled in 2016, according to a report by SMG, a firm hired by the Cuyahoga County Convention Facilities Development Corporation to manage operations for the facilities.

The three Mangalista heritage breed pigs help with the recycling efforts by eating some of the food scraps.

Find out more about the farm and sustainability efforts at the convention center in the video above.

These 5 Technologies Are On The Verge of Massive Breakthroughs

These 5 Technologies Are On The Verge of Massive Breakthroughs

A new report highlights a few promising fields that could explode in the near future.

By Kevin J. Ryan |Staff writer, Inc.@wheresKR

An Aerofarms employee uses a scissor-lift to check the vertically-growing greens within the company's Newark, NJ headquarters.

CREDIT: Ellise Verheyen

Here's a glimpse of what the future will look like.

This week, Scientific American published its annual report on emerging technologies. The list is a compilation of what the publication calls "disruptive solutions" that are "poised to change the world." To qualify, a particular technology must be attracting funding or showing signs of an imminent breakthrough, but must not have reached widespread adoption yet.

Here are a few of the cutting-edge technologies that made the list--and the companies that are already making strides with them.

1. Noninvasive Biopsies

Cancer biopsies, which entail removing tissue suspected of containing cancerous cells, can be painful and complicated. Analyzing the results takes time. Sometimes, the tumor can't be reached at all.

Liquid biopsies could be the solution to all those issues. By analyzing circulating-tumor DNA--a genetic material that travels from tumors into the bloodstream--the technique can detect the presence of cancer and help doctors make decisions about treatment. It can potentially go even further than traditional biopsies, identifying mutations and indicating when more aggressive treatment is necessary. Grail, which spun out from life sciences company Illumina earlier this year, currently has $1 billion in funding from investors including Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates. The startup is working toward developing blood tests that could detect cancer in its earliest stages.

2. Precision Farming

Farming doesn't have to be an inexact science. Thanks to artificial intelligence, GPS, and analytics software, farmers can now be more precise in managing their crop yields. This makes agriculture a more efficient operation, which is especially critical in parts of the world where resources or climate aren't conducive to growing. Indoor farming startups including Aerofarms, Green Spirit Farms, and Urban Produce all closely analyze their crops using these types of tools to maximize output and flavor. Blue River Technology and others use computer vision to cut down on wasted fertilizer--sometimes by 90 percent.

3. Sustainable Design of Communities

Creating sustainable neighborhoods isn't just be good for the environment--it might be good business, allowing companies and residents to reduce their energy costs. Google spinou Sidewalk Labs is scouting locations for a huge feasibility study that would use one neighborhood to showcase what the city of the future might look like, creating infrastructure for self-driving electric cars and sustainable energy sources like solar. Last year, Denver and Detroit were rumored to be front-runners for the project.

4. Deep Learning For Visual Tasks

Artificial intelligence has become shockingly successful at identifying images across a range of applications. Facebook already can recognize many of the people and objects in your photos and allows you to search for images by describing their contents. Google's image recognition software is the basis for its new platform, called PlaNet, which can in some cases predict the locations where photos were taken based on clues in signage, landmarks, and vegetation. Earlier this year, researchers at Stanford revealed that they'd trained A.I. to correctly identify skin cancer with 90 percent accuracy--higher than the dermatologists it went head to head with.

5. Harvesting Clean Water From Air

What if moisture could be pulled from the air, even in arid climates? Scientific American reports that research teams at University of California-Berkeley and M.I.T. are developing systems aimed at accomplishing just that. The scientists customize crystals called metal-organic frameworks to be extra porous and thus able to collect large amounts of water, which are then deposited into a collector.

An Arizona-based startup called Zero Mass Water harvests water using a different method. According to the publication, the company creates a system that uses solar energy to push air through a moisture-absorbing material. A unit with one solar panel, which runs about $3,700, produces between two and five liters of water per day. The company has performed installations in the southwestern U.S. as well as in Jordan, Dubai, and Mexico. It also recently sent panels to Lebanon to provide water to Syrian refugees.

Could Vertical Farms Save The Planet?

Could Vertical Farms Save The Planet?

With the global population rising at high speed, farmland shrinking, and more people moving to urban areas, the idea of vertical farms in cities has long been a dream. But as Bowery Farming has raised $20m for its “post-organic” vertical farm, bringing its total take to $27.5m, “indoor farming” is turning “from fantasy to reality”, says

Amy Feldman on Forbes.com.

Bowery’s co-founder and chief executive Irving Fain started his career as an investment banker at Citigroup, ran marketing at iHeartMedia and co-founded CrowdTwist, before turning to food.

In 2014 he teamed up with David Golden – who had previously co-founded and run LeapPay, a business loan provider – and Brian Falther, a mechanical engineer in automotive manufacturing. They began looking at how technology might enable better farming.

Bowery relies on computer software, LED lighting and robotics to grow leafy greens without pesticides and with 95% less water than traditional agriculture. With pricing similar to organics, Bowery sells six varieties of leafy greens to Whole Foods and Foragers, two grocery firms. By locating near cities, indoor farms have less impact on the environment and by controlling its environment Bowery can produce its greens 365 days a year. As a result, “the firm can produce 100 times more greens than a traditional outdoor farm occupying the same sized footprint”.

Why A Peanut Farmer From South Carolina Created A Facebook For Farmers

Why A Peanut Farmer From South Carolina Created A Facebook For Farmers

OCTOBER 2, 2015 LAUREN MANNING

As a nasty nor’easter hammers the Southeast, hurricane Joaquin lingers just off the Atlantic coast guaranteeing many more days of torrential downpour. For Pat Rogers, a fifth-generation peanut farmer running a 550-acre operation in the small town of Blenheim, South Carolina, the rain is unwelcome.

Peanuts, which grow underneath the topsoil, have to be dug up and flipped over to lie on the soil for a week so they can dry out. The last thing any peanut farmer wants to happen after a “dig up” is rain—let alone the one-two punch of a massive storm and a hurricane.

In prior years, Rogers would have been short on opportunities to commiserate with his farming colleagues about the cruel hand Mother Nature doled out. Thanks to a spark of inspiration and a whole lot of hard work, however, Rogers is hoping to change that for himself and other farmers in the business—and he’s using technology to do it.

“I was at the InfoAg conference in St. Louis during 2014. It’s just a whole bunch of farm tech and I was sitting there in the earliest session, looking around, and thinking, ‘This is great!’” says Rogers tells AgFunderNews. “But, the thing about farming is that so much of it is very rural. It’s not like we can all get together and network very often.”

Rogers returned to Blenheim and quickly set to work creating a way to make invaluable coffee shop chatter, tailgate talk, and barnyard business exchanges a lot more accessible for farmers far and wide. What was one of the first sources Rogers tapped to shape his plan? Entrepreneur Eric Ries’ famous book, The Lean Startup.

Over the summer, Rogers and a team of web developers soft-launched a website called AgFuse, a social media platform dedicated to farmers, and designed to help professionals across the agriculture world connect, share tips, show off their crops, pitch products, and keep in touch. Operating in a similar way to Facebook, with a healthy dose of LinkedIn’s business networking savvy, users can create a profile page, join groups, post messages, and peruse their news feeds to see what’s happening with other farmers in their network.

Building AgFuse’s website from the ground up enabled Rogers and the web development team to create algorithms that help members see the information that’s most relevant to their interests, operations, and needs.

While farm-focused message boards provide a flood of information, AgFuse is calibrated so that users only see postings and information from other members with whom they’ve connected.

For now, the crew is satisfied with its current algorithms, perfecting them is a routine objective. “We have a pretty good system that we are rolling out over the next week or two,” says Rogers.

After observing the soft-launch site and getting feedback from initial users, Rogers, and the AgFuse team, officially launched the site on July 22, 2015. While the platform became an instant hit with Rogers’ local community in South Carolina, he quickly saw users join from around the country and engage with other members.

AgFuse, which Rogers has fully funded himself, has even caught the attention of some venture capital investors. “In the future, that’s hopefully not only a possibility but a reality. Right now we are just focused on building a good product and building our user base,” he says. He also hasn’t ruled out the possibility of monetizing the site to provide members with carefully curated advertisements.

Rogers’ current priorities include site enhancements and building up its user base. They also have some big projects in the works, including a mobile app that is in the final stages of development, and additional AgFuse platforms focused on consolidating farmers’ knowledge around the globe.

According to Rogers, AgFuse is the first farm-centric social media platform of its kind. Although there are a number of message boards dedicated to farming and agriculture topics, he felt they weren’t cutting it when it came to helping farmers make real connections.

“If I sign in from South Carolina and they are talking about crop conditions in Illinois, that doesn’t really pertain to me,” explains Rogers. “You can still learn a lot of general things, but AgFuse’s specific niche is helping farmers find a specific audience.”