Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Plant-Loving Millennials At Home And At Work

The Etsy headquarters in Dumbo, Brooklyn, for example, could easily be mistaken for an indoor botanical garden. Spanning nine floors and over 200,000 square feet, the office is home to more than 11,000 plants, including dozens of large-scale plant displays and living walls installed and maintained by Ms. Bullene and Greenery NYC.

Plant-Loving Millennials At Home And At Work

By CAROLINE BIGGS | MARCH 9, 2018

Credit Brad Dickson for The New York Times

When Summer Rayne Oakes’s roommate moved out of their apartment in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, she was left with more than just a vacant bedroom.

“All of a sudden the apartment felt so cold and empty,” said Ms. Oakes, 33. “I needed to find a way to make the space feel warm and full of life again.”

Her solution? A fiddle leaf fig tree; the first of nearly 700 houseplants — spanning 400 species — that Ms. Oakes, founder of Homestead Brooklyn, would eventually buy for her 1,200-square-foot apartment.

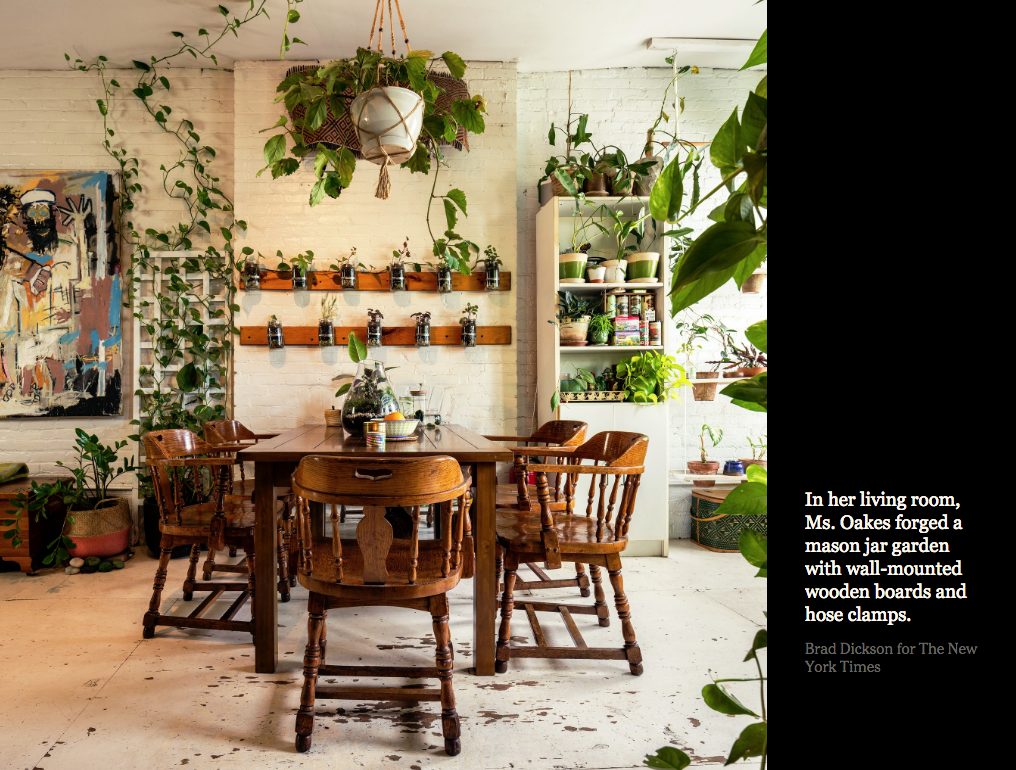

Her indoor forest features everything from a subirrigated living wall in her bedroom, which is a wall of greenery that is essentially a self-watering planter with a built-in reservoir; a vertical garden made out of Mason jars mounted to the living-room wall with wooden boards and hose clamps; and a closet-turned-kitchen grow garden with edible plants (ranging from herbs and greens to pineapple plants and curry leaves).

“I didn’t set out to build a jungle,” Ms. Oakes said. “I just saw how much energy and life the plants brought to the space and kept going.”

It’s a sentiment that more and more young people seem to be echoing in their own apartments. Wellness-mindedmillennials, especially ones in large urban environments that lack natural greenery, are opting to fill their voids — both decorative and emotional — with houseplants.

“Millennials were responsible for 31 percent of houseplant sales in 2016,” according to Ian Baldwin, a business adviser for the gardening industry. The 2016 National Gardening survey found that of the six million Americans who took up gardening that year, five million were ages 18 to 34. “This group has more college debt and as a result, are renting homes instead of buying,” Mr. Baldwin said. “Houseplants are a low-cost way to have a green space at home.”

Summer Rayne Oakes has created a vertical garden in her dining room that is made out of Mason jars mounted to the wall with wooden boards and hose clamps.CreditBrad Dickson for The New York Times

Meanwhile, Greenery NYC, a botanic design company, has increased its clientele by 6,500 percent since it was founded in 2010; developers are finding ways to include gardens as an amenity for residents, and more people — like Ms. Oakes — are turning what little spare space they have in their apartments into indoor gardens.

“Our sales have doubled each year,” said Rebecca Bullene, the founder of Greenery NYC. “And I attribute that mostly to businesses that want to attract millennial talent and millennials themselves who want more nature in their lives.”

Inside her 1,800-square-foot apartment in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, Ms. Bullene, 37, cares for over a hundred plants. She has installed a green divider wall — a six-foot-by-six-foot steel shelving unit filled with a dozen wooden planter boxes and over 50 plants — that separates her living room from her in-home office, as well as a terrarium and several other large-scale plants, including an 11-foot-tall Ficus Audrey tree, to help break up the open layout of the space.

But for Ms. Bullene, the plants do more than help define the apartment; they make her home healthier, too. “Plants boost serotonin levels and dissolve volatile airborne chemicals,” she said. “They actually make healthier spaces for humans to inhabit.” She cited a 2010 study from Washington State University that breaks down the benefits of indoor plants, including cleaner air and lowered stress levels.

Along with her floor-to-ceiling plant divider wall in the living room, she also employed a combination of plants that release oxygen at night in her bedroom — including aloe vera and sansevieria — so that she and her husband can breathe cleaner air while they sleep.

Millennial-minded companies are also going to great lengths to integrate greenery into their offices.

The Etsy headquarters in Dumbo, Brooklyn, for example, could easily be mistaken for an indoor botanical garden. Spanning nine floors and over 200,000 square feet, the office is home to more than 11,000 plants, including dozens of large-scale plant displays and living walls installed and maintained by Ms. Bullene and Greenery NYC.

“Every employee has a sight line to greenery,” said Hilary Young, Etsy’s sustainability manager, who helps the company seek ways to conserve the environment. “It’s a beautiful space that inspires and boosts productivity.” Greenery NYC and the architects at Gensler worked closely to create a state-of-the-art rainwater-harvesting and irrigation system at Etsy’s headquarters, which is considered the largest commercial “living building” in the world. It allows all the office plants to be watered with recycled stormwater.

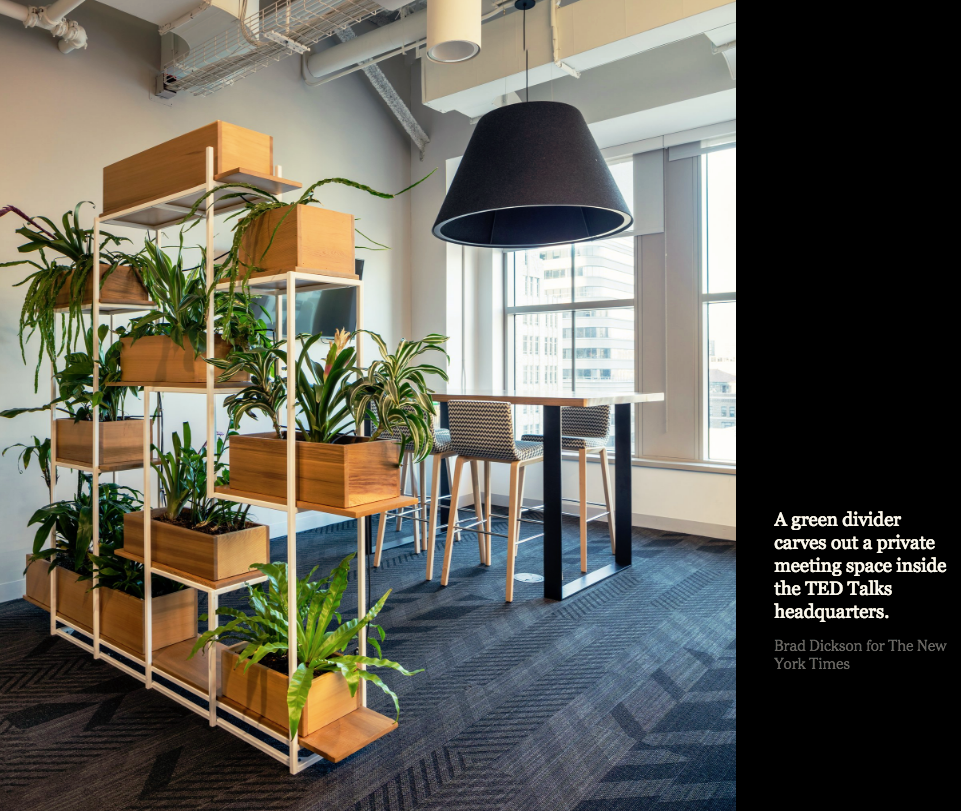

A line of cascading vines frames a conference room at the TED Talks headquarters in TriBeCa. CreditBrad Dickson for The New York Times

The roofs of the headquarters and a few of the neighboring buildings are outfitted with large gutters that collect and distribute rainwater to a 7,300-gallon cistern on the eighth floor of the Etsy building. From there, the water is dispersed through tubes to each floor of the building to water the plants.

“We wanted a space that bettered the lives of our employees,” Ms. Young said, “and that made a social and environmental impact outside of the office.”

And at the TED Talks headquarters in TriBeCa, Greenery NYC installed a series of unique plant displays throughout the two-floor office. Along with over 25 linear feet of boxed planters in the entrance lobby, the 50,000-square-foot office is filled with cascading vines, wall-mounted shelf planters, green dividers, and even desks outfitted with built-in planters, ensuring employees unlimited opportunities to take in a bit of nature throughout the workday.

“I love that when I look up from my work, all I see is green,” said Katie Hawley, 28, a senior editor at Etsy, who also keeps houseplants at home. “I feel happier just looking at them.”

With the increasing number of young people searching for access to greenery in their residences, real estate developers have also jumped on the trend.

At the ARC in Long Island City — a new 428-unit “industrial-inspired” luxury rental building developed by the Lightstone Group — residents have access to a 1,100-square-foot glass greenhouse, where they are free to plant and grow their own vegetables and herbs. “It’s been a tremendous selling point to prospective tenants,” said Scott Avram, senior vice president of development at Lightstone.

“One factor of my decision to rent in the ARC was the beautiful courtyard and greenhouse,” said Greg Garunov, 33. “There is something to having a green oasis at your fingertips in the steel city of New York.”

And over at the Margo, in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, residents enjoy a living wall in the lobby as well as a rooftop garden with plots that tenants can adopt for their own gardens.

You agree to receive occasional updates and special offers for The New York Times's products and services.

“Wellness is a priority for our millennial-aged residents,” said Dave Maundrell, executive vice president of new developments for Brooklyn and Queens at Citi Habitats. “They’re willing to pay more for access to a green space.”

But for those young urbanites who don’t have the luxury of a communal garden or greenhouse, houseplants remain an affordable, and renter-friendly option.

For instance, Ms. Oakes has managed to make the bulk of her indoor garden self-regulating and, perhaps more impressively, removable.

Thanks to several DIY irrigation systems she hacked throughout her home, including two irrigation units she created using a 150-foot hose that connects to pipes under her kitchen sink, Ms. Oakes said she has to spend only about a half-hour a day tending to her plants.

And to avoid leaks to the apartment below, Ms. Oakes reinforced her bedroom wall with plywood and then added metal gutters to collect any excess water before hanging up her vertical garden.

Ms. Bullene, a renter, also took care to ensure that all of her subirrigated plant systems — even the self-regulating terrarium and self-watering plant wall — are removable.

“All of the plant systems can come with us if we ever move,” Ms. Bullene said. “It’s as easy as unplugging them and removing a couple of screws.”

Ms. Oakes said that even though plant care might seem like a whole lot of work, the effort is worth it.

“New York City is tough,” she said. “My plants gave me a sanctuary to come home to.”

Transforming Germany’s Cities Into Organic Food Gardens

Transforming Germany’s Cities Into Organic Food Gardens

2/22/201 | FreshPlaza

With ever more people living in urban centers, food security and quality is becoming a pressing issue. In Germany, cities are increasingly taking the production of organic products to a hyperlocal level.

As part of Biostädte (‘organic cities’), now Nuremberg joins a network of municipalities across Germany -including Munich, Bremen and Karlsruhe- working to make food production healthier and more sustainable.

In other cities like Berlin, Cologne and Kiel, urban and community-supported agriculture is introduced, which includes the greening of new buildings and the transformation of uncontaminated industrial land into community gardens. Their plans also foresee car-free, solar-powered districts where edible plants grow on and around buildings.

Citizens are being encouraged to cultivate useful crops, using public green areas in their neighborhoods to plant rows of potato plants or fruit trees. In doing so, they alleviate the municipal taxes, as this costs less than designing and maintaining the public green spaces.

According to an article by dw.com, these urban agricultural spaces are intended to become focal points where food is produced, processed and traded.

Peek Preview of Hubitus Urban Sustainability Hub in Israel

Peek Preview of Hubitus Urban Sustainability Hub in Israel

Hubitus at the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens will be a zero-energy hub with smart water and solar collection systems, built from recycled containers.

By Abigail Klein Leichman FEBRUARY 5, 2018

Hubitus - the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens Hub for Urban Sustainability. Simulation by Sharon Golan

The architectural plans are completed for Hubitus – the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens Hub for Urban Sustainability, and it’s easy to see why the co-founders are fielding inquiries from botanical gardens all over the US and Canada.

“We took the entrepreneurship hub model from the startup world and adapted it to the environmental world. This is something that has never been done before, definitely not at a botanical garden,” says co-founder and director Lior Gottesman.

She and co-founder Adi Bar-Yoseph have described Hubitus, a unique co-working space for environmental entrepreneurs, environmental artists and designers, urban planners, social activists, gardeners and urban farmers, at international conferences in Hawaii, Miami, San Diego and St. Louis.

Open classrooms at Hubitus – the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens Hub for Urban Sustainability. Simulation by Sharon Golan

Recently they accepted invitations from the heads of the Chicago Botanical Gardens and the UC Davis Botanical Gardens in California.

“We are invited to talk all over the world as botanical gardens rethink their social role,” Gottesman tells ISRAEL21c. “We’ve taken it to the next level by having change agents sitting in the garden. We’re the startup nation so it’s clear this innovation will come from here.”

Hubitus – the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens Hub for Urban Sustainability. Simulation by Sharon Golan

Hubitus already exists virtually for the past three years, providing courses, training, events and professional connections to 80 change agents. The hub also runs outreach programs including an initiative to establish sustainable gardens in preschools.

The physical space to house 30 Hubitus members was planned with the input of that community in coordination with Noam Austerlitz, a prominent Israeli “green” architect and lecturer at Tel Aviv University’s schools of architecture and environmental studies.

Office of Hubitus – the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens Hub for Urban Sustainability. Simulation by Sharon Golan

The zero-energy hub will generate as much renewable energy as it uses, aided by intelligent water collection and solar energy systems. “It will be built entirely of recycled containers using green construction techniques,” says Gottesman.

“In addition to the workspaces, our hub also will have classrooms, open spaces, rooftop gardens, green walls and more because our community needs places to prove and demonstrate concepts in areas such as beekeeping, hydroponics and vertical gardening.”

Closed classroom at Hubitus – the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens Hub for Urban Sustainability. Simulation by Sharon Golan

The grading of the site has started, with funding from Leichtag Foundation, and further fundraising is being conducted through JNF Australia and the Jerusalem Foundation. In addition to Austerlitz Architecture, the hub has engaged the services of Shlomo Aronson Architects for landscape design.

How A School Kitchen Garden Can Transform An Entire Community

2018

How A School Kitchen Garden Can Transform An Entire Community

A school initiative is encouraging whole multicultural communities to improve their relationship with food. (Sunshine North Primary School)

"They say food brings people together. What we’ve found is that this program has brought our community together."

By Yasmin Noone

29 JAN 2018

There’s a small kitchen garden situated in the cultural melting pot of Sunshine North in Melbourne’s west that’s changing the way the community interacts with food.

It’s not in a local park or in an expensive gardening centre tended to by masses of horticulturists.

No. This edible garden of influence – cared for by children, teachers and parents – is located on the grounds of the low-socioeconomic, multicultural Sunshine North Primary School.

The kitchen garden at this school, operating as part of the nationwide Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Garden Foundation, goes one step further than educating kids about plants and food.

It aims to help a very diverse group of students to read and write, and encourages parents - many of whom are newly arrived migrants - to integrate into Australian society.

“We are a very multicultural community,” Sunshine North Primary School principal, Ken Ryan, tells SBS Food.

“There are 300 children at the school and 35 different nationalities here. We have a very big Vietnamese community and the second largest community is from Burma.

“For many of our students, they start at our school at the beginning of their life in Australia. But the thing is, only one-in-10 students speak English at home. So the starting point for the children’s formal education when they come here is usually quite low.”

School kitchen gardens aren’t just about kids dipping their fingers in the soil.

The school, which became involved in the kitchen garden program around 11 years ago, has developed the program into something extra special. The teachers have integrated kitchen garden lessons into the school curriculum, which incorporates science, math, critical thinking and English.

The recipes are used to teach children and their parents basic reading, comprehension and maths, while science lessons are conducted in the garden.

Conversational English skills are practiced while children are eating their cooked lunch. As they sit together around a table – that they set – kids discuss the experience of cooking and chat about what the food tasted like.

Students from kindergarten through to Year six participate in gardening and cooking classes, utilizing 80 percent of school-grown produce as they prepare meals (with teacher supervision) in the school kitchen.

Community-wide benefits

The program has also helped parents from non-English speaking backgrounds who haven’t felt confident volunteering for academic-based activities at the school.

They get involved with Sunshine North Primary community by lending a hand in the garden.

“Everyone cooks and everyone eats, no matter what language you speak, so we engaged the parents in the garden and in the kitchen,” says Ryan

“Parents now come into the school and look after the garden or feed the chickens. The program is the result of a whole community effort.

“They say food brings people together. What we’ve found is that this program has brought our community together.”

aims to help a very diverse group of students to read and write, and encourages parents to integrate into Australian society.

A healthy lesson for all ages

Ryan explains that the kitchen garden – consisting of seasonal herbs, fruits and vegetables – is also teaching parents and children about health and wellbeing, and on the dangers of fast food in Western society.

“It used to kill me to watch some parents coming into the school, with a McDonald's meal for their child at 10 am which they wanted to be served to them for lunch at 1 pm, thinking they were doing the right thing.

“I thought, ‘we need to change the learning around Western food and how important food is in general in a child’s wellbeing’.

“We can now clearly see that at our school, this program helps both children and their parents to make good choices about their food.

“They are learning, [as a community] to grow their own food and understand that the food you grow yourself tastes different to the food you buy.”

1,630 kitchen gardens nationwide…and counting

Sunshine North Primary is only one of the many schools around Australia participating in the Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Garden Foundation.

Since 2004, the program has been implemented in 1,630 primary schools, high schools and early learning centres nationwide. The program is among the most popular in primary schools – 1,065 primaries are involved – while 70 special schools and 237 early learning centres also participate.

The foundation reports that Victoria is by far its biggest supporter, with kitchen gardens now in almost 560 schools and centres across the state.

However, there are 48 kitchen gardens implemented in the Northern Territory, 59 in Tasmania, 71 in the ACT, 139 in South Australia, 213 in Queensland, 170 in WA and 377 in NSW.

It's also about teaching immigrant parents and children about health and wellbeing, and on the dangers of fast food in Western society.

Why kitchen gardens create good food habits

Rebecca Naylor, CEO of the Kitchen Garden Foundation and Program, attributes the program’s national popularity to its ethos – kitchen gardens teach children why eating well is important, what good food actually looks and tastes like, and where food comes from.

“Kids habits are formed early in life,” says Naylor.

“If we can build habits for kids early on, that help them engage with growing food, cooking that food, eating seasonal fresh delicious food and then sharing that with others, then their relationship with food will be different than if they were never exposed to that experience.”

Since 2004, the program has been implemented in 1630 primary schools, high schools and early learning centres nationwide.

Naylor explains that when kids are involved in the program their willingness to try new foods also increases.

“Many kids don’t necessarily know where food comes from so their experience of food is shopping in the supermarket – not putting a seed in the ground and growing a pumpkin or beetroot.

“We know, even for us as adults, many of us have a fairly distant relationship with our food. But if your experience of food, [early on] is going to school, putting a seed in the ground and watching it grow in an environment where you also learn maths, English and language, then you are more likely to want to try that purple dip with the beetroot you’ve grown, as opposed to not wanting to try a meal put in front of you that you have no association with.”

Evidence-based success

The program is reaping positive education, community engagement, health and wellbeing results. A national evaluation of the program, funded by the Department of Health and Ageing and conducted between 2011-2012 by University of Wollongong researchers, found it to be a positive learning experience for students. Over 97.5 per cent of teachers involved also thought it benefited their student’s learning.

An earlier university study, done from 2007-2009, discovered that the program encouraged students to make positive health behaviour changes. These changes, the research showed, were then transferred to their home and community environments.

The program is reaping positive education, community engagement, health and wellbeing results.

Barriers to access

The success of the kitchen gardens program begs one question: why doesn’t every school across Australia have a kitchen garden, run by this foundation or another?

Naylor says there’s often an assumption that schools might need a big space for a kitchen or garden to be involved. While this was once true, the program has been altered to adapt to the needs of any size school of any socio-economic standing.

“To be fair, it’s true to say that schools that have a lower socioeconomic make-up often find it harder to get a program like this up and running because they have less of an ability to draw on the school community for fundraising – for example.”

However, Sunshine North Primary School got one running.

“It all comes down to the vision and leadership at a school. There needs to be someone involved in the school who has the ability to see how a program like this can be used right across the school community and curriculum.”

Naylor also calls on state governments to exercise leadership and encourage all schools of the value of kitchen garden programs for children of all backgrounds and wealth status.

“We need governments to say that running a kitchen garden of this type in your school is what they want to see happening.

“It will give schools the permission they need to engage in the work that is required to set a program like this up.”

How do you provide tasty, delicious and high-quality meals, whilst keeping prices affordable? It’s a problem Shane Delia is facing both in his business and with his Feed the Mind project. The answer for Shane is to look for local solutions, and he enlists the help of Stephanie Alexander to supercharge the school garden as a means to provide healthy ingredients that don’t need to be ordered from the shop. Watch the episode on SBS On Demand here.

Shane Delia's Recipe For Life airs 8pm, Thursdays on SBS, then on SBS On-Demand. You can find the recipes and more features from the show here.

These 11 Easiest Vegetables to Grow Makes Gardening 10x Better

These 11 Easiest Vegetables to Grow Makes Gardening 10x Better

Posted on 2018-01-24 by Chris

What if I told you there are numerous easiest vegetables to grow that can make gardening 10X better and fun?

What’s more?

They require no special care or technical expertise.

You’d think there must be some hidden catch, right?

But there’s not. It’s absolutely true.

Today in this post, I’m going to walk you through 11 easiest vegetables to grow.

So, what makes some vegetables easier to grow than others? I’ve looked at four factors as follows;

1. The growing season – If a given vegetable has a short growing season, the growing becomes much easier.

2. Moisture requirement – as minimum as possible. Watering is a very difficult gardening task. Therefore, the little of it required the better.

3. Temperature – as flexible as possible.

4. Space – utilizes space efficiently.

Based on these four parameters, I’ve been able to come up with this list that can be used by both newbies as well as experienced gardeners.

Let’s jump in…

11 Easiest Vegetables to Grow

Potato

Potatoes are generally grown from seed potatoes – these are tubers specifically grown to be disease free and provide consistent and healthy plants. To be disease free, you should select the areas where seed potatoes are grown are with care.

Luckily, potatoes are so easy to grow, that gardeners end up with “accidental” potatoes every year!

Their growth is divided into five phases:

During the first phase, sprouts emerge from the seed potatoes and root growth begins.

During the second, photosynthesis begins as the plant develops leaves and branches.

In the third phase stolons develop from lower leaf axils on the stem and grow downwards into the ground and on these stolons new tubers develop as swellings of the stolon.

This phase is often (but not always) associated with flowering. Tuber formation halts when soil temperatures reach 27 °C; hence potatoes are considered a cool-season crop.

Tuber bulking occurs during the fourth phase, when the plant begins investing the majority of its resources in its newly formed tubers.

At this stage, several factors are critical to yield: optimal soil moisture and temperature, soil nutrient availability and balance, and resistance to pest attacks.

The final phase is maturation:

The plant canopy dies back, the tuber skins harden, and their sugars convert to starches – and then your potatoes are ready!

Read: 13 Easy to Grow Vertical Garden Plants

Lettuce

Generally grown as a hardy annual, lettuce is easily cultivated, although it requires relatively low temperatures to prevent it from flowering quickly.

Lettuce is one of the easiest vegetables to grow. It grows quick, is relatively convenient to harvest because you just have to simply snip the tops off the plants or select leaves as needed

It also takes up very little area. They are able to grow even in containers, possibly accompanied by flowers or tucked under taller plants.

Lettuces meant for the cutting of individual leaves are generally planted straight into the garden in thick rows.

Heading varieties of lettuces are commonly started in flats, then transplanted to individual spots, usually 20 to 36 cm (7.9 to 14.2 in) apart, in the garden after developing several leaves.

Lettuce spaced further apart receives more sunlight, which improves color and nutrient quantities in the leaves.

Lettuce grows best in full sun in loose, nitrogen-rich soils with a pH of between 6.0 and 6.8.

Heat generally prompts lettuce to bolt, with most varieties growing poorly above 24 °C; cool temperatures prompt better performance, with 16 to 18 °C being preferred and as low as 7 °C being tolerated.

Zucchini

Zucchini is very easy to cultivate in temperate climates. As such, it has a reputation among home gardeners for overwhelming production.

The part harvested as "zucchini" is the immature fruit, though the flowers, mature fruit, and leaves are eaten as well.

One good way to control overabundance is to harvest the flowers, which are an expensive delicacy in markets because of the difficulty in storing and transporting them.

The male flower is borne on the end of a stalk and is longer-lived.

While easy to grow, zucchini, like all squash, requires plentiful bees for pollination.

In areas of pollinator decline or high pesticide use, such as mosquito-spray districts, gardeners often experience fruit abortion, where the fruit begins to grow, then dries or rots.

This is due to an insufficient number of pollen grains delivered to the female flower. It can be corrected by hand pollination or by increasing the bee population.

Bok Choy

Bok choy (Brassica rapa) is also called Chinese cabbage.

This Chinese vegetable is a cool weather vegetable that grows best in spring and fall.

Growing bok choy is done from seed. Planting bok choy can be done by directly seeding the garden soil or by starting plants indoors until the weather is right for transplanting later.

Either way, when planting bok choy, germination occurs within seven to ten days.

Bok choy used to be limited to meals in Chinese restaurants, but these days you are just as likely to find it growing in backyard gardens.

It's a quick growing vegetable and there are a surprising number of varieties to try.

Takes relatively shorter time to mature. Depending on the variety and the weather, bok choy should be ready to harvest in 45 - 60 days.

eet

All beets grow best in fertile soil with a pH between 6.2 and 7.0. Water the prepared bed, and plant beet seeds half an inch deep and 2 inches apart, in rows spaced 12 inches apart.

Beet seeds germinate in five to 10 days if kept constantly moist. Repeated watering can cause some soils to crust on the surface, which can inhibit the emergence of seedlings.

Cover seeded rows with boards or burlap for a few days after planting to reduce surface crusting. This technique is also useful when planting beets for fall harvest in warm summer soil.

Just be sure to remove the covers as soon as the seedlings break the surface.

Scallion

Scallions grow so fast.

Actually, you can re-root scallions from the grocery store.

You may even have luck regrowing the ones you've used for cooking if you leave a couple of inches of stem attached to the roots.

You don't even have to plant them in the garden. Scallions will happily grow in a glass of water. When something is this ridiculously easy to grow, you might as well take every opportunity.

Read: Small Space Gardening: 14 Mind Blowing Ideas (#7 is my favorite)

Onion

Onions are best cultivated in fertile soils that are well-drained.

Sandy loams are good as they are low in sulphur, while clayey soils usually have a high sulphur content and produce pungent bulbs. Onions require a high level of nutrients in the soil.

Phosphorus is often present in sufficient quantities, but may be applied before planting because of its low level of availability in cold soils.

Nitrogen and potash can be applied at regular intervals during the growing season, the last application of nitrogen being at least four weeks before harvesting.

Bulbing onions are day-length sensitive; their bulbs begin growing only after the number of daylight hours has surpassed some minimal quantity.

Most traditional European onions are referred to as "long-day" onions, producing bulbs only after 14 hours or more of daylight occurs.

Southern European and North African varieties are often known as "intermediate-day" types, requiring only 12–13 hours of daylight to stimulate bulb formation.

Finally, "short-day" onions, which have been developed in more recent times, are planted in mild-winter areas in the autumn and form bulbs in the early spring, and require only 11–12 hours of daylight to stimulate bulb formation.

Onions are a cool-weather crop and can be grown in USDA zones 3 to 9. Hot temperatures or other stressful conditions cause them to "bolt", meaning that a flower stem begins to grow.

Ginger

The easiest way to get started growing ginger root is to get a few fresh rhizomes of someone who does grow ginger, at the time when the plant re-shoots anyway (early spring).

Otherwise just buy some at the shops at that time.

Make sure you select fresh, plump rhizomes.

Look for pieces with well developed "eyes" or growth buds. (The buds look like little horns at the end of a piece or "finger")

Some people recommend to soak the rhizomes in water over night. That's not a bad idea, since shop bought ginger might have been treated with a growth retardant.

Pea

Choose an open, weed-free site in full sun. Grow peas in a moist, fertile, well-drained soil.

Try to dig plenty of well-rotted compost into the soil several weeks before sowing to improve soil fertility and help retain moisture.

It's best to avoid sowing peas on cold, wet soils as they tend to rot away. If space is at a premium then try growing peas in containers or patio bags.

Provide supports - Peas produce tendrils to help them climb upwards.

Erect wire netting, or push upright twiggy sticks into the ground along the length of each trench to provide your peas with supports to cling to.

Water regularly- Once pea plants start to flower it's best to water thoroughly once a week to encourage good pod development.

You can reduce water loss by applying a thick mulch of well-rotted manure or compost to lock moisture into the soil.

Radish

Radishes are a fast-growing, annual, cool-season crop. The seed germinates in three to four days in moist conditions with soil temperatures between 18 and 29 °C.

Best quality roots are obtained under moderate day lengths with air temperatures in the range 10 to 18 °C.

Under average conditions, the crop matures in 3–4 weeks, but in colder weather, 6–7 weeks may be required.

Radishes grow best in full sun in light, sandy loams, with a soil pH 6.5 to 7.0, but for late-season crops, a clayey-loam is ideal. Soils that bake dry and form a crust in dry weather are unsuitable and can impair germination.

Harvesting periods can be extended by making repeat plantings, spaced a week or two apart. In warmer climates, radishes are normally planted in the autumn.

The depth at which seeds are planted affects the size of the root, from 1 cm (0.4 in) deep recommended for small radishes to 4 cm (1.6 in) for large radishes.

During the growing period, the crop needs to be thinned and weeds controlled, and irrigation may be required.

Swiss chard

Swiss chard (Beta vulgaris) is an easy-to-grow, heat-resistant heirloom that does not bolt; it has a mild flavor.

Growing Swiss chard works best in rich, moist soil with a soil pH between 6.0 and 6.8. Plant about 12 to 18 inches apart in fertile soil, watering directly after planting.

Work nitrogen-rich amendments such as blood meal, cottonseed meal, feather meal, or composted manure into the ground before planting.

Other options include applying a timed-release vegetable food, such as 14-14-14, according to label directions, when planting and every couple of weeks during the growing season.

Like all vegetables, Swiss chard does best with a nice, even supply of water. Water regularly, applying 1 to 1.5 inches of water per week if it doesn’t rain.

You can measure the amount of water with a rain gauge in the garden.

Apply organic mulch such as compost, finely ground leaves, wheat straw, or finely ground bark to keep the soil cool and moist and to keep down weeds.

Mulching will also help keep the plant leaves clean, reducing the risk of disease.

Read: The Complete Guide to Organic Gardening with Zero Skills

Kale

Kale is a leafy vegetable in the Brassica or Cole crop family.

It is usually grouped into the "Cooking Greens" category with collards, mustard and Swiss chard, but it is actually more of a non-heading cabbage, although much easier to grow than cabbage.

The leaves grow from a central stem that elongates as it grows. Kale is a powerhouse of nutrients and can be used as young, tender leaves or fully grown.

Kale can be grown as a cut and come again vegetable, so a few plants may be all you need.

The plants can be quite ornamental, with leaves that can be curly or tagged, purple or shades of green. It is considered a cool season vegetables and can handle some frost, when mature.

Carrot

Carrots are grown from seed and can take up to four months (120 days) to mature, but most cultivars mature within 70 to 80 days under the right conditions.

They grow best in full sun but tolerate some shade.

The optimum temperature is 16 to 21 °C. The ideal soil is deep, loose and well-drained, sandy or loamy, with a pH of 6.3 to 6.8.

Fertilizer should be applied according to soil type because the crop requires low levels of nitrogen, moderate phosphate and high potash.

Rich or rocky soils should be avoided, as these will cause the roots to become hairy and/or misshapen. Irrigation is applied when needed to keep the soil moist.

After sprouting, the crop is eventually thinned to a spacing of 8 to 10 cm (3 to 4 in) and weeded to prevent competition beneath the soil.

Conclusion

You’ve just read about some of the easiest vegetables to grow.1

Now all you have to do is choose one, give it a try and before you know it, you’ll become an expert in even growing the complex ones.

Just take the first step.

New Haven Farms To Expand Healthful Garden Program

New Haven Farms To Expand Healthful Garden Program

By Esteban L. Hernandez

Published 3:53 pm, Sunday, January 14, 2018

hoto: Credit: New Haven Farms

NEW HAVEN—New Haven Farms will expand its popular incubator program this spring to include 25 additional families who will manage their own garden plot and have access to fresh produce.

New Haven Farms Executive Director Russell Moore said the program has grown every year since it launched in 2015. Two new incubator sites will be placed in Fair Haven on Stevens Street, near Shelter and Clay streets, and on Davenport Avenue in the Hill neighborhood.

Fair Haven’s site will support 15 families, while the Hill is expected to serve 10. The program currently has 50 families, a majority of whom are low-income residents.

Families first participate in a wellness program operated jointly by Fair Haven Community Health Center and NHF before joining the incubator program, which provides them a plot of land to build their own vegetable garden. The goal of the wellness program is to assist people in developing more healthful eating choices to address possible health concerns. The incubator garden allows participants to continue healthful habits learned through the wellness program.

“The significance of it is not just 25 families,” Moore said. “It’s that their family members will benefit from fresh produce.”

NHF works in partnership with the New Haven Land Trust and the Harvard Pilgrim Healthcare Foundation to fund the incubator program.

Moore recently visited the Fair Haven site. At the moment, it looks barren, with what he suspected were dead collard greens near the entrance. But the site will eventually be home to 15 additional families using the land, once seeding begins in March and the season starts in May.

New Haven Farms manager Jacqueline Maisonpierre, who helped to develop the incubator garden program in 2015, said the program fits well into NHF’s mission to, “promote health and community development through urban agriculture.”

The program has just about a 100 percent retention rate, though two families have moved out of the city, Maisonpierre said.

Moore said between the seven gardens, which together comprise just about one acre, New Haven Farms produced 18,000 pounds of produce. Providing produce for 50 families means more than 200 people receive help.

“We’re really getting people to change, to make large behavioral shifts in their lives so that they can live a healthier life and reduce their dependence on medication,” Maisonpierre said.

The incubator gardens teach families “that they have the powers to change their own health outcomes,” Maisonpierre said.

New Haven Land Trust Executive Director Justin Elicker said the trust supports 52 community gardens in New Haven. Elicker said NHF’s program teaches citizens how to be more healthy.

“This partnership was a great fit for both organizations,” Elicker said. “Graduates of the wellness programs have an ability to continue their connection to the community that they developed.”

Last fall, an NHF site near Ferry Street was the site of a robbery that left a seasonal worker injured. The man who was attacked is still working for NHF; Moore said the attack seemed to make his commitment to the organization even stronger.

The attack prompted a community meeting and increased police patrol. Added safety measures, including lights, were installed on a nearby post, and have helped with security, Moore said. He was happy with both the community and local law enforcement response to the incident.

“It was galvanizing,” Moore said.

The response seems to reflect what Moore said is another important effect from their gardening programs, which is people learning by example.

“One shining example can have a ripple effect throughout the community,” Moore said.

Reach Esteban L. Hernandez at 203-680-9901

Northeast Organic Farmers Coming Together at Rutgers This January

Northeast Organic Farmers Coming Together at Rutgers This January

By ADRIAN HYDE

January 17, 2018 at 11:35 AM

More than 50 workshops on food, farming, and gardening will be offered at the Northeast Organic Farming Association of New Jersey (NOFA-NJ) Winter Conference at the Rutgers University Douglass Student Center, 100 George Street, New Brunswick.

The sessions run Jan. 27 and 27, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. They'll include five tracks: crops, livestock, gardening, policy and urban farming.

Anyone interested in learning about local, organic and sustainable food, permaculture and related policy issues is invited to attend.

The theme of this year’s conference is “Regenerating Our Communities, Restoring Our Land,” and nationally-recognized speakers are coming in from all over the country. This year’s keynote is Mark Shepard author of Restoration Agriculture, which explains his approach to permaculture, as practiced at his New Forest Farm in Wisconsin.

In his work, Shepard makes the “whys and hows” of permaculture compelling and accessible, including its ability to sequester gigantic amounts of atmospheric carbon. He also explains clearly the tradeoffs between annual and perennial crops.

Don Huber, PhD, will speak in a double-session about his research on the harms of glyphosate, the world’s most ubiquitous pesticide. Along with the content of his presentations, Huber provides copious references to scholarly and scientific work on the subject.

Dan Kittredge, lifelong farmer and founder of the Bionutrient Food Association, will reveal his organization’s efforts to democratize testing for food quality in a completely open-source framework.

For several years, Kittredge has been a leader in efforts to produce more nutrient-dense, high-quality foods, and early successes in the BFA’s food testing strategy suggest exciting possibilities.

In addition to Mark Shepard, other nationally-recognized, expert permaculturists will be speaking, both individually and on the “PermaPanel.” There will be something for everyone, from topics of general interest to specific practices for experienced farmers.

For more information, please visit nofanj.org or contact NOFA-NJ at 908-371-1111.

Kimbal Musk Doubles Down On School Garden Effort

Learning gardens provide access to nutritious food and serve as educational tools at underserved schools. Photo courtesy of the Kitchen

Kimbal Musk Doubles Down On School Garden Effort

The Colorado 100 Fund is a $2.5 million effort toward creating 100 learning gardens in Colorado by 2020.

BY DALIAH SINGER | JANUARY 3, 2018

In 2011, Kimbal Musk, co-founder of the Kitchen (and brother of tech giant Elon Musk), decided it wasn’t enough serving real, local food at his family of restaurants. So he launched the Kitchen Community nonprofit with the goal of “empower[ing] kids and their families to build real food communities from the ground up.”

In practice, what that means is creating learning gardens—a garden as an outdoor classroom—in underserved, low-income schools across the country. Since the first opened in Denver in 2011, 450 learning gardens have been built across the country. Colorado, though, has begun lagging behind. The state currently has 55 learning gardens; Chicago has 150. But that will soon change: Musk recently announced theColorado 100 Fund, a $2.5 million initiative to increase the number of Centennial State learning gardens to 100 (in other words, adding 45 more) by the end of 2020. “We built our first [learning garden] in Denver,” says Courtney Walsh, Musk’s communications director. “We need to look at our own backyard…to really impact change.”

Kimbal Musk (right) and a student at a Kitchen Community learning garden in Los Angeles in 2015. Photo by Patrick T. Fallon for the Kitchen Community

According to the 2017 Kids Count report from the Colorado Children’s Campaign (CCC), 16 percent of Colorado children experienced food insecurity—“their access to adequate food was limited by lack of money and other resources”—between 2013 and 2015. In addition, many high-poverty neighborhoods are located in food deserts, meaning they have limited access to affordable and nutritious foods. That’s one of the reasons the CCC says, “…children growing up in low-income or food-insecure families are likely to…have challenges getting the nutrients they need for proper growth and development.”

School gardens can help reverse those concerns by exposing children to fruits and vegetables, teaching them where their food comes from, and encouraging healthy lifelong eating habits. At an elementary school, students might count the plants and learn their names. In middle and high school, the gardens become the foundation for a science class or a lesson in entrepreneurship (how to run a farm stand, for instance).

To accomplish the 100-garden goal, Musk formed a Leadership Circle comprised of prominent Coloradans who support his efforts to improve children’s health. Among them is Robin Luff, who also serves on the board of the Kitchen Community. “We’re there to talk about the importance of real food, of changing behaviors. We all believe that can happen when we have a really strong effort in a city,” Luff says. “It’s useful, and it’s lasting.”

Schools submit applications for learning gardens, and the district has to approve the Kitchen Community’s efforts. The nonprofit has already worked with the Denver Public Schools and the Poudre School District and will continue to do so; it expects to add some gardens in Jefferson County as part of the Colorado 100.

“One of the challenges in Colorado versus some of the other inner cities we’re working with is that we have this gorgeous landscape we look at every day,” Luff says, “and it’s really hard to imagine that some kids have never played in a stream or with sticks. [Determining how to] make a lasting impression in Denver is really important.”

One hundred learning gardens is a big enough number to convince people (the legislature, school boards) to pay more attention to the issue. “It becomes an ecosystem about learning about food,” Walsh says. “If you have 100, then you’re able to truly impact the community…and reach kids at all age levels.”

But don’t expect this work to stop once Musk and team reach 100. ”Kimbal’s overarching national goal is to build 1,000 learning gardens to ostensibly impact a million children,“ Walsh says. We have no doubt he’ll get there.

DALIAH SINGER, 5280 CONTRIBUTOR

Daliah Singer is an award-winning writer and editor based in Denver. You can find more of her work at daliahsinger.com.

Urban Farming: Lessons From Growing Power

Across the country, supporters grieved the loss of Growing Power, of its example, and of the hope it offered for scaling up urban farming as a sustainable model

Urban Farming: Lessons From Growing Power

By: MARY TURCK | December 30, 2017

Just a year ago, an article in Medium touted Will Allen as “the Godfather of Urban Farming, Who’s Breeding the Next Generation of People to Feed the World.” Allen, who started urban farming in Milwaukee in 1993, then moved on to Chicago, ended up with his Growing Power organization involved in urban farming projects around the world. Along the way, Allen won a MacArthur “genius” grant in 2008 and was named one of Time Magazine’s 2010 Time 100.

Allen’s vision and his non-profit corporations focused on reimagining and rebuilding a food system in cities. Among its ambitious projects:

- aquaponic systems growing fish, watercress, and wheatgrass;

- rebuilding soil through composting and vermiculture, including a collection of supermarket wastes and use of red worm composting to turn them into soil;

- increasing productivity with intensive cultivation of food plants on small plots of land;

- sparking a passion for farming in urban youth and teaching them job skills to land jobs in the sustainable farming and food system;

- growing mass quantities of high-quality food and delivering it to people living in inner cities;

- modeling urban farming as a real and sustainable option for people around the world.

Then, in November 2017, Growing Power crashed. After years of running deficits and with more than half a million dollars in legal judgments against the organization, Allen resigned and the organization closed its doors.

New Urban Farming Organizations Sprouting

Across the country, supporters grieved the loss of Growing Power, of its example, and of the hope it offered for scaling up urban farming as a sustainable model. But the end of Growing Power does not mean the end of urban farming, not any more than a hard frost means the end of a garden. Instead, new plants have already begun to sprout.

In Milwaukee, Green Veterans Wisconsin plans to buy Growing Power’s shuttered headquarters, reclaiming it as “an urban farm school, co-op for small farmers and trauma resolution center.” Its mission: “to regenerate men and women who have served in the military for green jobs and green living.”

In Chicago, the Growing Power team has spun off into a new Urban Growers Collective, with a mission of “creating healing spaces through art and innovation rooted within the foundation of growing food.”

Less than a month after the end of Growing Power, it’s too soon to predict outcomes for either initiative, but they are only two of the seeds now growing.

Across the country, urban farming initiatives take multiple forms. Some focus more on producing nutritious, organic food, some more on the powerful therapeutic possibilities of connecting youth with growing, some on building community while feeding community, and some on creating a profitable business model.

Three Minnesota examples show combine focus on food, youth, and community:

Youth Farm MN, established in 1995 in Minneapolis, aims “to create an urban environment where youth could flourish physically, socially, and emotionally as they mature into young adults. Youth were the focus and food was the conduit.” After more than 20 years, Youth Farm engages more than 800 young people and works to build and feed community in five specific Minneapolis and St. Paul neighborhoods.

Youth in the Dirt Group take pride in harvesting produce that they have grown themselves.

The Dirt Group’s motto is “Learning to Grow, Growing to Learn.” Its focus is on giving youth “an opportunity to experience social inclusion by being part of a safe, cohesive, structured group. Students feel pride and ownership in their collective efforts growing food together as they learn, practice, and master important life and social skills and make a difference in their communities by donating food they have grown to local food shelves and other such community organizations.” Its gardens are located in urban (Minneapolis, MN), small town, and rural settings.

The MNyou Youth Garden operates in the Minnesota city of Willmar (population about 20,000) on a plot of land and greenhouse provided by a local college. Its purpose is “to have minority youth, ages 15 to 24, research how to grow and maintain highly sought after vegetables then put that research to work. During their time in the project, the youth will develop entrepreneurial skills from working closely with mentors in local businesses on how to sell and market their products. They will also learn transferable job skills from experienced volunteers while receiving a minimum wage.”

Home-made signs mark the Dirt Group’s herb garden, and plots tended by small groups.

Connecting food, farming, youth, and community works for non-profit organizations that do not need to make urban farming turn a profit. Some other urban farming initiatives rely on heavy infusions of grants and donations or on rent-free use of city-owned or vacant lots. Profitability – or economic sustainability, in the progressive parlance – remains the most difficult problem for any kind of farming, urban or rural, small-scale or larger.

Money, or the lack of money, led to Growing Power’s demise. Does the blame lie with the high cost of organic food production? Or with the exponential growth of Growing Power, beyond the scale that could be effectively managed? Whatever the cause of its eventual dissolution, Growing Power gave a powerful inspiration to others to engage in agriculture that places a higher value on food and community than on profit. The seeds Will Allen planted will continue to flourish long after Growing Power’s end.

The Dangers of Urban Gardens

The problem is almost everything else: in the midst of the horticultural fever people have forgotten that urban agriculture has challenges that seriously compromise the food security of its crops. If we do not take this problem seriously, we will find ourselves promoting tasty, ecological toxins.

The Dangers of Urban Gardens

In recent years, every city worth its salt that has had a system of urban gardens. It's a very good idea: an almost perfect combination of green spaces, community activities and food education.

The problem is almost everything else: in the midst of the horticultural fever people have forgotten that urban agriculture has challenges that seriously compromise the food security of its crops. If we do not take this problem seriously, we will find ourselves promoting tasty, ecological toxins.

The dangers of urban gardens

A few years ago, the United States experienced a controversy that illustrates the problems and dangers that urban gardens can entail. Ryan Kuck, the director of Greengrow, an urban farm located in the industrial zone of Philadelphia since the eighties, said that his two newborn twins had high levels of lead in their blood due to the consumption of fruits and vegetables from their own garden.

Lead, for example, is especially harmful to children. In high concentrations it can have a very damaging effect on the nervous system and can cause mental retardation, developmental disorders or behavioral problems. According to the World Health Organization, in reality, there are no known safe levels of lead for children or adults: almost any concentration has detrimental effects on a lot of systems and parts of the body.

As Kuck himself acknowledged, "I was worried, but not surprised." The use of land in urban areas constantly changes with the city's cycles and development. A clear example is lead: for decades millions of cars used leaded fuels, thousands of buildings were painted with lead paint. Of course the soil of the cities is contaminated! There is pollution in the environment!

In addition, the plants we use in horticulture have the property of accumulating potentially toxic elements and compounds, such as heavy metals or derivatives of the use of hydrocarbons.

"The perfect salad"

That is, we are putting 'accumulators' of toxins in a contaminated soil. According to Andres Rodriguez, people are blindly planting gardens because of the urban gardens are fashionable. That is to say, they are installing the gardens without analyzing if the conditions of the land are suitable for cultivation (and, later, consumption).

According to Rodríguez, who investigates lead pollution in urban soils, despite their pedagogical and leisure potential, most urban gardens are a completely unnecessary ecological risk. They are also a sanitary risk. The scientific research that has been carried out on the subject supports it.

Natural = safe

The foods that enters the 'food circuit' is very controlled but there are few controls on the fruits and vegetables that we can find in urban gardens. It's paradoxical that the search for healthier foods has led us to producing food without any controls, cultivating it in contaminated lands and putting the health of those who consume it at risk.

These are not theories, the analyses that have been carried out in urban gardens in Madrid, as Rodriguez pointed out, are clear: land is not safe. Nothing justifies continuing with the projects to expand them if there are no minimum guarantees of security.

In addition, the data is so worrying that it seems inadvisable that the urban gardens movement should claim food security as one of its central ideas. It would be a pity if one of the most successful movements of community dynamism in recent years was lost due to health problems.

Source: magnet.xakata.com

Publication date: 11/22/2017

Sky High Veggies? Urban Farming Grows in Unexpected Places

CalSTRS Executive Chef Conrad Caguimbal offers a salad with roasted vegetables from the pension fund’s edible garden featured every day in the CalSTRS cafeteria in West Sacramento. Renée C. Byer rbyer@sacbee.com

Sky High Veggies? Urban Farming Grows in Unexpected Places

BY DEBBIE ARRINGTON | darrington@sacbee.com

OCTOBER 13, 2017 2:00 PM

Fresh vegetables and herbs, harvested steps away from the kitchen; that’s a chef’s dream.

In the Farm-to-Fork Capital, it’s also a sign that a business has thoroughly bought into an ethos of sustainability. Grow tomatoes at your doorstep – or on your roof – and patrons know those veggies are as local as they can get. So do employees who like to know their food source is just outside their windows.

Popping up throughout California are statement-making gardens full of food. That includes the landscaping at the front entrance of West Sacramento’s CalSTRS building, home to the California State Teachers’ Retirement System.

“Most people grow landscaping as an afterthought,” said Lara Hermanson, the gardener/farmer behind Farmscape, which created the CalSTRS “Waterfront Gardens.” “They put in some shrubs and lawn, then forget about it. Food is much more interesting.

Farmscape, the largest urban farming company on the West Coast, has created more than 700 edible gardens in unexpected places.

“We do anything from a couple of raised beds to giant rooftop projects,” said Hermanson, who started growing food as landscaping for wealthy families in Malibu who wanted “kitchen gardens” without the gardening part.

As part of its contracts, Farmscape provides regular maintenance as well as original plans and setup. Packages start at $79 a week for 125 square feet; consultations start at $90 an hour. That’s expensive for a residential vegetable garden, but more reasonable for business or public projects – especially for such high-profile landscaping such as at the entrance of a major building.

Businesses may want to grow edible landscaping, but have no clue how to do it, Hermanson noted. Farmscape takes care of everything from planning to planting to harvest. Adding color and beauty, seasonal flowers, herbs and ornamental plants are mixed in with the vegetables, so the beds appear manicured and attractive year round.

Besides looking good, these gardens have an immediate dividend: Fresh organic food.

“That’s what people love,” Hermanson said.

Farmscape’s most famous “farms” are on top of Levi’s Stadium, the Santa Clara home to the 49ers, and under the scoreboard at the Giants’ AT&T Park in San Francisco.

Featuring espaliered fruit trees as well as annual vegetables, the Giants’ garden had a better summer than the team.

“Produce from that garden is used in three little cafes (at the ballpark) that feature wood-fired pizza including gluten-free options,” Hermanson said. “They also offer vegan options for folks who don’t do baseball food.”

A short throw from the bullpen, hydroponic towers sprout berries and greens used in ballpark smoothies and salads.

“It’s kind of an idea garden,” Hermanson said. “During games, 40,000 people can see how good it looks and think about growing food, too.”

Dubbed “Faithful Farm,” the rooftop garden at Levi’s Stadium supplies fresh produce to the venue’s food service. It looks like a typical vegetable garden – except the soil is only 6 to 9 inches deep and it sits nine stories above the ground.

“We had a crazy good summer at Levi’s,” Hermanson said. “We harvested 5,000 pounds of food from a 6,000-square-foot space. We had a thousand pounds of just melons! We grew so many peppers, we harvested 100 pounds a week.”

Among the challenges of farming on the roof: It gets really windy (but so does AT&T Park) and it’s less protected from rain and sun.

“Everything is more intense on the roof,” Hermanson said. “We had trouble with all that rain (last winter). The little lettuce just rot; it wouldn’t grow. On Christmas Eve, we had another huge storm. And the wind!

“(In summer and early fall), it gets so hot up there, everything just gets cooked,” she added. “But we’re getting to know what works up there.”

On the banks of the Sacramento River, the CalSTRS garden is much more hospitable. Originally planted two years ago, it has 10 raised beds plus more than a dozen fruit trees. It’s also been prolific; this summer, it produced 2-1/2 pounds of food per square inch.

Executive chef Conrad Caguimbal, who oversees CalSTRS’s busy cafe, enjoys growing vegetables and herbs for cafe meals. Open to the public, the cafe serves about 700 meals a day.

“I love the fact I can actually harvest my own produce, take it to the cafe and create something delicious,” Caguimbal said, “and I never get my hands dirty.”

Each week day, he creates an “Earth Bowl,” featuring fresh selections from the garden that sits just outside the cafe’s patio. Using veggies picked that morning, a recent bowl mixed together kale, zucchini and caramelized carrots with barley for a vegan entree.

“A lot of people get excited when we harvest,” he said. “They’ve been watching those tomatoes and squash grow, too.”

CalSTRS chose edible landscaping because it fits with its overall sustainability initiative, explained Madeline O’Connell, the facility’s environmental sustainability specialist. For example, the LEED-certified building recycles 40 tons of organic waste per month to make energy. (That includes waste from the garden.)

“We also use the garden for educational events,” O’Connell said. “After all, we serve teachers.”

Hermanson loves the CalSTRS garden, in part because of its location. It welcomes the building’s 1,100 workers as well as visitors and passersby.

“It’s really fun,” Hermanson said. “It’s right on the river walk. People take lunchtime rambles and stop by the garden. When we’re out there, we get a lot of questions. Is this real? Where does the produce go? (Visitors) interact – and that’s exactly the idea.”

Debbie Arrington: 916-321-1075, @debarrington

Conrad Caguimbal, executive chef at CalSTRS in West Sacramento, builds a salad from vegetables he gathered in the agency’s new edible garden. It’s on the daily menu at the CalSTRS cafeteria. Renée C. Byer rbyer@sacbee.com

Farm Bill Discontent: Urban Ag Supporters want Changes

Danielle Marvit is production manager for Garden Dreams Urban Farm and Nursery in Pittsburgh. She has serious concerns about conventional agriculture. Here, she talks with journalists during the recent annual convention of the Society of Environmental Journalists in Pittsburgh. (Jonathan Knutson/Agweek)

Farm Bill Discontent: Urban Ag Supporters want Changes

By Jonathan Knutson / Agweek Staff Writer on Oct 16, 2017

PITTSBURGH — Sonia Finn, Danielle Marvit and Raqueeb Bey are passionate about agriculture. And they believe U.S. farming practices are dangerously off course and need to be corrected, starting with the 2018 farm bill.

"The farm bill isn't right for agriculture. People need to get involved and work to change it," Finn said.

Finn is chef and owner of Dinette restaurant in Pittsburgh. Marvit is production manager of Garden Dreams Urban Farm and Nursery in Pittsburgh. Bey is project director of Black Urban Gardeners and Farmers of Pittsburgh Co-op, or BUGS-FPC, as the group calls itself.

They spoke with Agweek Oct. 4 at Garden Dreams Urban Farm and Nursery during the annual convention of the Society of Environmental Journalists. The event included a day-long session on the farm bill and urban agriculture; Finn, Marvit and Bey were among the presenters.

Though some in mainstream agriculture are skeptical of urban ag, attention is growing for the concept. U.S. local food sales totaled at least $12 billion in 2014, up from $5 billion in 2008, and experts anticipate the figure to reach $20 billion by 2019, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Urban ag consists of "backyard, rooftop and balcony gardening, community gardening in vacant lots and parks, roadside urban fringe agriculture and livestock grazing in open space," according to USDA.

Urban ag has at least one powerful champion.

Michigan's Debbie Stabenow, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Agriculture Committee and a key player in U.S. ag policy, last year introduced the Urban Agriculture Act of 2016. The proposal — at least some of which she hopes will be included in the 2018 farm bill — would increase research funding for urban ag, provide more access for urban farmers to USDA loans and risk management programs, and boost the development of urban farming cooperatives, among other things.

Get involved

Finn has both professional and personal interest in promoting urban ag; she grows much of the produce used by Dinette on the restaurant's roof and relies on local farms for as many ingredients as possible.

She's also determined to transform the farm bill, the centerpiece of federal food and agricultural policy. She's gone to Washington, D.C., repeatedly to lobby for her beliefs.

She insists that the existing farm bill — and mainstream ag in general — is tailored to the wants and needs of powerful corporate interests, not what's best for the overwhelming majority of Americans.

"Most people just don't understand how important the farm bill is," Finn said.

Marvit, for her part, is critical of much of America's conventionally raised food.

"It's not real food," she said.

The quarter-acre Garden Dreams Urban Garden and Nursery, established about a decade ago, seeks to promote urban ag, giving neighborhood residents more and healthier food options. It also wants to help community residents learn more about gardening and give them a peaceful place to visit.

The organic operation specializes in tomatoes, raising more than 70 varieties of tomato seedlings. It also has peppers, eggplant, flowers and other fruits and vegetables.

Local control

Bey stressed that urban agriculture gives residents of local neighborhoods greater influence over both their food supply and their lives in general.

"Neighborhoods need more control over what happens to them," Bey said.

Her own Pittsburgh neighborhood has been without a grocery store for decades, forcing its residents to travel several miles by bus to buy food, she said.

BUGS-FPC is establishing a 31,000-square-foot urban farm that will use hoop houses, also known as high tunnels, to grow food to sell at its farm stand and its farmers market, at restaurants and at a community cooperative grocery that it wants to open.

Though interest in, and awareness of, healthy food is growing, supporters of urban ag and local foods need to focus on improving the farm bill and making it friendlier to consumers, Finn said.

"It's just so important we do it," she said.

USDA's "urban agriculture toolkit" is a good starting place to learn more about urban ag:www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/urban-agriculture-toolkit.pdf.

Vertical Forests Are Returning Nature To Cities, One Skyscraper At A Time

Who on Earth decides to plant a forest on the side of skyscrapers? Architects, that’s who. Two bold designers working on opposite ends of the planet are actively designing farms, gardens and forests designed to live on massive residential buildings.

Vertical Forests Are Returning Nature To Cities, One Skyscraper At A Time

By Clayton Moore — Posted on September 23, 2017 1:00 pm

Stefano Borei Architett Vertial Forest

Who on Earth decides to plant a forest on the side of skyscrapers? Architects, that’s who. Two bold designers working on opposite ends of the planet are actively designing farms, gardens and forests designed to live on massive residential buildings. Far from simply putting a few houseplants in the office, these ambitious designs are meant to clean the air, reduce energy use to net zero, and maximize food production and quality of life.

LIFE IS SWEET IN THESE “VERTICAL FORESTS” IN MILAN, ITALY

One of these projects is already complete. The Bosco Verticale (“Vertical Forest” in Italian) is a dual skyscraper project designed by Stefano Boeri that is covered in more than 21,000 plants—a level of greenery equivalent to more than five acres of forest spread over more than 1,200 square meters.

The project has just been named one of the best tall buildings in the world. It’s a completely green design that even supports its own moderate ecosystem, including more than 20 species of birds. The massive amount of vegetation helps reduce Singapore’s moderate pollution and carbon dioxide, cleaning up the air. The plant life also diminishes noise, boosts oxygen in the air, and helps regulate the temperatures between the two towers. Internally, a complex irrigation system directs “used” water back onto the forested terraces to sustain the vegetation and reduce waste.

It’s a level of greenery equivalent to more than five acres of forest.

“Vertical Forest is a model for a sustainable residential building, a project for metropolitan reforestation contributing to the regeneration of the environment and urban biodiversity without the implication of expanding the city upon the territory,” Boeri noted on his website. “It is a model for vertical densification of nature within the city. Vertical Forest increases biodiversity, so it becomes both a magnet for and a symbol of the spontaneous re-colonization of the city by vegetation and by animal life.”

The concept earned his firm second place in the 2014 Emporis Skyscraper Award, beating out more than 120 competitors including The Leadenhall Building in the United Kingdom, the KKR Tower in Malaysia, and the Burj Mohammed Bin Rashid Tower in Abu Dhabi. Only the WangJing SOHO triple skyscraper in Beijing bested the Boeri design, awarded for “its excellent energy efficiency and its distinctive design, which gives the complex a harmonious and organic momentum.”

But this completed design isn’t the only plant-accented project on Boeri’s plate; he has a portfolio of potential and ongoing projects around the world that use urbanized plant life to make the world better for the people who live and work in his buildings.

Boeri has announced plans for two Vertical Forest projects in Nanjing, China, as well as “Liuzhou Forest City,” in mainland China, the Wonderwoods residential tower in the Netherlands, and the sprawling Guizhou Mountain Forest Hotel in Southern China. His new “Tower of Cedars” in Lausanne, Switzerland is a 36-story tower that features nearly 20,000 plants and 100 trees to protect residents from pollution and dust.

“All these projects together are important for us,” Boeri told Mashable recently. “It’s very important to completely change how these new cities are developing. Urban forestation is one of the biggest issues for me in that context. That means parks, it means gardens, but it also means having buildings with trees.”

DESIGNING THE URBAN SKYFARM

Developing concurrently is one of the most dramatic building projects in the world. The Urban Skyfarm, designed by Brooklyn-based Aprilli Design Studio and to be located in Seoul, South Korea, will house nearly 25 acres of space for growing trees, tomatoes, and other sustainable crops.

The prototype building is modeled after the iconic design of a tree, with the “root,” “trunk,” “leaves,” and “branches” components to house different aspects of the sustainable farming operation.

The “trunk” of the Urban Skyfarm will contain an indoor hydroponic farm, while the “roots” provide a wide, environmentally friendly space for farmer’s markets and public events. On top of the tower, turbines provide enough power to fuel the building operations and farming spaces in a net-zero environment. The building will also capture rainwater and filter it through a synthetic wetland before returning it as fresh water to a nearby river.

The space could efficiently host more than 5,000 fruit trees.

“With the support of hydroponic farming technology, the space could efficiently host more than 5,000 fruit trees,” architects Steve Lee and Soon Yun Park recently told Fast Company. “Vertical farming is more than an issue of economical feasibility, since it can provide more trees than average urban parks, helping resolve urban environmental issues such as air pollution, water run-off and heat island effects, and bringing back balance to the urban ecology.”

Despite a location in crowded Seoul, the Urban Skyfarm will act as a living machine by producing renewable energy and giving residents improved air quality. Reproducing the biological structure of a tree gives the design certain advantages because it is light in weight but houses enough space to host a diverse range of farming activities. The design is also intended to reduce heat buildup, rain runoff, and carbon dioxide.

The architects believe that their design can support hundreds of environmental projects and experiments and serve as a future model as to how buildings are designed, built, and used.

“We hope the Urban Skyfarm can become part of the discussions as a prototype proposal,” Lee and Park said. “Vertical farming really is not only a great solution to future food shortage problems but a great strategy to address many environmental problems resulting from urbanization.

BUILDING GARDENS IN THE SKY

Boeri and Aprilli are the furthest along in these wild, green experiments, but there are plenty of other firms thinking about how arboreal and greenery-inspired designs can help make life better and more sustainable for residents and tenants around the world.

In Southeast Asia, Vo Trang Nghia Architects are building a huge complex in Ho Cho Minh City that will feature a 90,000-square-foot facility with a rooftop garden. The firm is also working with FPT University to build a tree-lined campus that will raise an elevated forest over the 14-square-mile site.

One Central Park in Sydney features massive creeping vines that climb the building’s face as well as nearly 200 native plant species.

Back on western shores, the Rolex corporation recently broke ground on its new Dallas-based headquarters, which features landscaped terraces and a tree-lined rooftop event space. The elegant design by architect Kengo Kuma was inspired by Japanese castles.

Under construction in Los Angeles is 670 Mesquit, a 2.6 million-square-foot mixed-use project that features two massive cubes that feature landscaped terraces. This is Danish architect Bjarke Ingels’ first project in Los Angeles.

Other architects are pushing the envelope of what’s possible. Harmonia 57 is a building in Brazil designed by Triptyque that actually “breathes and sweats,” according to the designers. Plants embedded in porous concrete structures are watered with a mist that makes the building look like it’s returning to nature.

All this added greenery is a pleasant distraction from the densification of urban environments, but these designers are also redefining what it means to live in an urban landscape—and providing a fresh chance to build sustainable urban environments that help cut down on pollution while they simultaneously generate energy, biodiversity, and a breath of fresh air.

How Does the Hamptons Garden Grow? With a Lot of Paid Help

The hardest-worked muscles may be in the hand writing the checks: These lavish, made-to-order gardens can cost as much as $100,000, said Alec Gunn, a Manhattan landscape architect whose firm designs high-end residential, commercial and public-works projects throughout the country.

How Does the Hamptons Garden Grow? With a Lot of Paid Help

The vegetable garden of Alexandra Munroe and her husband, Robert Rosenkranz, in East Hampton, N.Y., is sheltered from the ocean winds by dunes covered with Rosa rugosa.

DANIEL GONZALEZ FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

By STACEY STOWE

SEPTEMBER 5, 2017

EAST HAMPTON, N.Y. — The rigors of vegetable gardening, for most people, are humble and gritty: planting, weeding, dirtying knees, working up a sweat and maybe straining a back muscle or two.

But here on the gilded acres of Long Island’s East End, a different skill set often applies: hiring a landscape architect to design the garden, a gardener and crew to plant and pamper the beds, and sometimes even a chef to figure out what to do with the bushels of fresh produce. All that’s left is to pick the vegetables — though employees frequently do that, too.

The hardest-worked muscles may be in the hand writing the checks: These lavish, made-to-order gardens can cost as much as $100,000, said Alec Gunn, a Manhattan landscape architect whose firm designs high-end residential, commercial and public-works projects throughout the country.