Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

The Art of Future Food | A Nebullam Newsletter

The Art of Future Food | A Nebullam Newsletter

September 2017

Volume 2

We're back, with our 2nd newsletter! We promise to keep our updates simple and short. Let's jump right in.

Our new shirts. We're thankful for the opportunity to work on technologies with applications here, and elsewhere. These shirts aren't for sale, but we may have a few extra if you catch us out and about (or on social media @nebullam).

In the News

- We've made the semi-finals of this year's John Pappajohn Iowa Entrepreneurial Venture Competition, along with plenty of other familiar faces (see photo above)

- America's SBDC Profile - Nebullam

What We're Reading

The Trajectory

- Our pilot site will be growing new varieties of microgeens this month

- Our R&D space is up and running

- Our seed round of investment has been raised from $300,000 to $500,000. If you know of anyone interested in investing in vertical farming technologies, or artificial intelligence, we'd be happy to visit with them

Quote of the Month

"Instead of thinking outside the box, get rid of the box." - Deepak Chopra

If you enjoy our newseltters, please consider forwarding them onto anyone else who may be interested in our story, progress, or contributing to our mission; to create the art of future food, now.

- The Nebullam Team

2710 South Loop Drive, Ames, IA, United States | 641-201-0651

For Profit Hydroponic Farm in Chicago Seeks to Increase Employment Opportunities in Underserved Community

Since its inception in 2013, Garfield Produce has been working to improve economic growth and employment opportunities for Garfield Park community members. The for-profit business was born from a collaboration between a successful retired couple, Mark and Judy Thomas, and an engineering major from DePaul University, Steve Lu.

For Profit Hydroponic Farm in Chicago Seeks to Increase Employment Opportunities in Underserved Community

September 7, 2017 | Charli Engelhorn

Darius Jones, general manager, vice president, and part of owner of Garfield Produce, an urban hydroponic farm located in Garfield Park, a west-side community in Chicago. Photo courtesy of Garfield Produce.

“Education is the most important thing,” says Darius Jones, general manager, vice president, and part of owner of Garfield Produce, an urban hydroponic farm located in Garfield Park, a west-side community in Chicago. “We’re trying to create an environment that inspires people to grow and feel valued.”

Since its inception in 2013, Garfield Produce has been working to improve economic growth and employment opportunities for Garfield Park community members. The for-profit business was born from a collaboration between a successful retired couple, Mark and Judy Thomas, and an engineering major from DePaul University, Steve Lu.

Through missionary work with the Breakthrough Urban Ministries, Mark and Judy saw that their misconceptions about poverty—that it is the result of laziness and not taking advantage of the same opportunities afforded to others—were inaccurate, according to Jones. What the Thomas’ discovered was that people did want to work, but there were no opportunities available and a number of systemic obstacles in place that hindered people’s ability to work.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, Garfield Park changed from a predominantly Caucasian community to a predominantly African-American community, and most of the equity that existed has been removed over the past 25 to 30 years. As one of the top five communities in the city for crime rate and poverty, the infrastructure in the community has degraded, leaving close to 3,000 abandoned buildings and facilities and no real job opportunities, says Jones, a Garfield Park native.

“When they came to Garfield Park and saw how things were, they decided there needed to be some kind of business opportunity or job opportunity offering entry-level positions, since most of those available are located in far suburbs, requiring nearly a two-hour commute for a minimum wage job,” Jones says. “Steve brought in the urban agriculture component.”

As a young company, the current focus is building the business and increasing its income to be able to support more entry-level positions. This action is happening through relationships with Chicago-area chefs, catering companies, and restaurants, and will possibly expand to include a relationship with Whole Foods, which has approached Garfield Produce about carrying its products in their stores.

“We would love that relationship because it will help us scale faster,” says Jones. “Any dollars spent on our business go directly into a community member’s pocket. We’re tracking key performance metrics so we can show our customers where their dollars are going and how many hours of gainful employment their spending affords.”

Garfield’s vertical hydroponic farm, housed in a 5,600-square-foot facility, yields approximately 2,000 to 5,000 pounds of 25-30 varieties of specialty micro greens and micro herbs, such as pea tendrils and greens mixes, a year. The farm’s production modules currently occupy only 320 sq ft. Another 2,200-square-foot grow room is in development, which will increase production to 21,000 pounds a year and add another five to 10 varieties of greens.

The hope is that this greater yield will translate into more income, allowing the company to increase their workforce from two—Darius and one grower—to approximately 11 with the addition of another grower and grower’s assistant, a sales position, and six more entry-level positions.

“We’re talking about entry-level positions that would make a little more than minimum wage, but we’re setting up the company so employees can have ownership,” Jones says. “We want the business to be fully employee owned, so even though an entry-level job wouldn’t be life-altering, equity in a company would be.”

The main challenge in employing members of the community is finding people with enough knowledge and training. The company hopes to overcome this impediment by working with local organizations that do job training for the area’s large number of people with felony convictions, which accounts for 65 percent of the population, according to Jones, who went through a similar job-training program seven years ago.

“A lot of these guys will go through three to nine months of transitioning job training through organizations that get state or federal money, and in some areas, that includes sustainable urban agriculture training, but once they are finished, there are no jobs for them,” Jones says. “This is perfect for us because providing these jobs is exactly what we want to do.”

The company also continues to work with Breakthrough Urban Ministries, which, as well as providing men’s and women’s shelters, a food pantry, and a healthy food kitchen, supports the people in their housing program with entry-level job training. The one employee besides Jones was found through the ministry’s men’s shelter in 2014.

The partnership with the ministry also includes donations of leftover harvested greens to the food pantry. Jones would love to expand this partnership to include more activities, such as food demos, but admits that part of the downside of a for-profit business is a lack of logistical feasibility to get out and educate the public with efforts that are not sales-based, an issue that also influences their customer base.

“We don’t have the manpower to be out marketing and educating the community about our products. So, right now, we are looking to bring dollars into the business, get it built up, and then start pushing the products into the community,” says Jones.

Jones wants the business model to be scalable, sustainable, and replicable so they can take it to another of the many underutilized facilities on the west side of Chicago and build the same footprint using the same sales channels to make it profitable for other communities.

“We’re not just an organization coming into a neighborhood without knowing anything about it; we’re coming in with knowledge of the neighborhood,” Jones says. “We know most of the local consumers think micro greens are too expensive, so we can talk to the people in the community about what urban agriculture is and the benefits of micro greens, find ways to use more economical packaging and bring the costs down so local consumers are not scared away.”

Garfield Produce will begin opening its doors to community members for tastings soon and hopes to increase its education efforts by working with local schools. The company is already in partnership with Nick Greens Grow Team, a group specializing in hydroponic and controlled-environment agriculture, to sponsor hydroponic systems in schools so students can learn the importance of growing their own food and use the food they grow in their lunches.

What Are Novel Farming Systems?

What Are Novel Farming Systems?

AUGUST 29, 2017 | LOUISA BURWOOD-TAYLOR AND EMMA COSGROVE

Novel farming systems are new methods of farming living ingredients, many of which are traditionally grown outdoors.

Consumers are scrutinizing the agrifood industry more than ever for its widespread use of natural resources such as water and arable land, and for its negative impact on the environment. The agrifood sector is neck and neck with heating and cooling as the global industry producing the most greenhouse gases. Industrial farming can also have a damaging environmental impact with the application of chemicals and fertilizers contributing to soil degradation, drinking water contamination, and run off harming local ecosystems.

As a planet, we are also faced with the challenge of increasing food production despite decreasingly nutrient-dense soil and a warming planet. While some are attempting to lessen the extractive nature of conventional farming in soil, or to create seeds and crops that can thrive in these new conditions, others are working on removing land and soil from the equation altogether.

To alleviate these pressures, startups and innovators are finding new ways to produce food and ingredients with novel farming systems in the hope of doing so more sustainably, using fewer natural resources.

Further, many novel farming systems focus on the farming of fish, insects, and algae which have the potential to alleviate the environmental pressure of increasing global demand for protein, where cattle farming is bearing the majority of the burden.

Novel farming systems have also emerged as a captivating solution in the eyes of the public and investors precisely because they could change the paradigm of traditional agriculture so dramatically. Though, as we will explore in our upcoming agrifood tech investing report, public and media excitement are not always met with equal investment.

Novel farming systems, as a category of agrifood tech, includes:

- Indoor farms — growing produce in hi-tech greenhouses and vertical farms

- Insect farms — producing protein alternatives for animal and aquaculture feed and for human food

- Aquaculture — producing seafood and sea vegetables including algae

- New living ingredients such as microbes for use in food, as well as for other industries and applications

- Home-based consumer systems using the technology of any of the above

Here is a closer look at the components of our novel farming systems category of startups ahead of the AgFunder MidYear AgriFood Tech Investing Report.

Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) or Indoor Agriculture

The concept of farming indoors in not new; greenhouses have been around for centuries. But in recent years, greenhouses and more insulated indoor spaces like warehouses and shipping containers are rapidly picking up pace as a means to grow food closer to consumers, remove many of the unpredictabilities of outdoor agriculture, and drastically reduce the inputs necessary for outdoor farming.

There are only a few key ingredients needed to grow food: light, water, and nutrition. By growing food in a controlled environment, indoor farmers aim to give plants the perfect amount of each, reducing waste, but also maximizing yields. They can also manipulate the doses of each of these ingredients to impact flavor, color, and texture.

Tomatoes, strawberries, peppers, leafy greens, herbs, flowers, and cannabis are all frequently grown in controlled environments. Greenhouses specifically are also an important part of the tree crops industry as most rootstock starts in a greenhouse.

By some estimates, there are more than 40,000 indoor farming operations in the US alone, producing food worth more than $14.8 billion in annual market value. These numbers exclude the cannabis industry, which brings in an additional $6.7 billion in sales.

The different configurations of CEA include greenhouses and indoor vertical farms, and within these two categories, there is much variation in terms of physical growing structures and architecture, delivery systems for light, water, and nutrients, light source, growing medium, automation, data collection, and environmental controls.

Greenhouses

Greenhouses are covered structures made of glass or plastic that allow sunlight to get in but offer varying degrees of temperature control. They have been used commercially to grow fruits and vegetables for decades, but there are various ways greenhouse technology is being used today beyond its simplest form of growing plants under glass in pots of soil.

Soilless hydroponic growing systems — where the plants are grown in a watery medium as opposed to soil — have been used in greenhouses for more than a decade by major growers like Village Farms and Backyard Farms. And today, computer vision, artificial intelligence, automation, and precision agriculture techniques are arriving at the greenhouse. Some greenhouses are fully kitted-out with sensors using machine learning to detect disease, facilitate efficient use of space, and identify anomalies both within the environment and with individual plants.

Some greenhouse technology has come a particularly long way, with incidences of hybrid greenhouse and indoor operations growing cannabis, like Supreme Pharmaceuticals, as well as innovative locations — like Gotham Greens above Whole Foods in Brooklyn, New York — and business models.

Main greenhouse crops today include lettuces and, leafy and micro greens, tomatoes, peppers, and cannabis.

Vertical Farms

Ranging from as small as a shipping container to as large as an airplane hanger, indoor vertical farms are growing steadily in number, although some have already failed in what’s a capital intensive field.

Most operating vertical farms today are growing only leafy greens and microgreens due to the short growing cycles and high yields. There are a few growing strawberries such as Japan’s Ichigo Company.

Vertical farms use LED lights for photosynthesis and some form of hydroponics for water and nutrition. The fairly simple equation is nutrient-enriched water, moved either in a mist or through channels or tanks around the roots of plants. The roots are planted in various media ranging from spun concrete to coconut husks to cloth, which are submerged in the water or mist.

Every one of the elements involved in growing the plants can be manipulated precisely to influence the outcome — such as lighting wavelengths, timing, the types of nutrients, and so on. This can be particularly effective if sophisticated data collection and analytics are in place; many farms claim that their own internally-created software and hardware tools enabling this are their main differentiator.

The largest vertical farms by capital raised include AeroFarms, Bowery Farming, and Plenty which are all starting to use artificial intelligence and machine learning to manage their plants and boost yields.

Robotics are also slowly making their way into indoor agriculture, though they are currently only used for crops that grow in containers such as rootstock for apple, cherry, and almond trees, and in these cases, the robots move the containers as opposed to more complicated tasks. But fruit-picking and sorting robots are on the way with several startups in the space making advancements and raising funding. (Stay tuned for our Farm Robotics deep-dive article coming soon!)

Aquaponics

Aquaponics is a smaller subset of indoor farming where farmers grow vegetables integrated with, and on top of, fish farms, so that the waste generated by the fish can fertilize the plants. The technology set up is very similar to a vertical farm, but the monitoring of the input composition and the physical layout differ greatly from operations purchasing plant nutrition. Aquaponics operations, like Edenworks in New York and Organic Nutrition in Florida, sell both vegetables and fish.

Aquaculture

Aquaculture is the cultivation of sea creatures and vegetables for human and animal consumption.

According to United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization data from 2010, aquaculture makes up half of the seafood consumed by humans today. This includes the farming of all varieties of fish, along with oysters, scallops, shrimp, mussels, and other shelled creatures. Most of the innovation in this space is currently geared towards fish feed for farmed fish rather than the technology used at the farms themselves. Fish feed is a particularly crucial challenge as currently 30 million tons of wild caught fish per year are used to feed farmed fish, which is a third of global wild fish harvest. With global stocks of wild fish declining, and some sources pointing to the crash in some forage fish populations, this is an unsustainable source of food for farm-raised fish long-term, even with increasingly sustainable practices employed by the fishmeal and fish oil industry. This problem, valued at $100 billion, will likely be solved at least in part by some of the other types of novel farming systems listed here, especially insect farming.

Algae farming represents an underdeveloped sector within novel farming systems but has great market potential. It has been estimated that the algae market will reach $45 billion by 2023 and algae, especially macro algae like edible seaweeds, are farmed in most cases completely without technology or digitalization. Macroalgae can be grown in open water as well as in tanks while most microalgae, which are single-celled, must be grown in a controlled setting. Algae farming startup EnerGaia is growing spirulina (microalgae) on rooftops in Bangkok, Thailand.

Microbe farming

Microbe farming is another emerging field with various applications. Ginkgo Bioworks, for example, genetically engineers microbes for partner companies in the flavor, fragrance and food industries. These microbes are primarily forms of yeast or bacteria that can be designed to replace a natural alternative; rose oil, for example, would be expensive for some companies to manufacture as an ingredient given that roses are not a commodity crop. But Ginkgo can manufacture that fragrance or flavor in-house by writing new DNA code to re-program the genome of a microbe to have it do what customers want. These DNA designs are proprietary to Gingko, as well as the robotics and other technology the company uses to culture the microbes, mostly through a fermentation process. Zymergen and Novozymes are other startups growing microbes, in these cases to make agricultural inputs.

Insect & worm farming

Insects and worms are set to become an increasingly important protein source for both animals and humans with demand far outpacing supply. Insect farming is mainly touted as a more sustainable alternative to animal protein, particularly as the quality of the protein insects offer is actually quite high. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO), “insects have a high food conversion rate, e.g., crickets need six times less feed than cattle, four times less than sheep, and twice less than pigs and broiler chickens to produce the same amount of protein.” Further, insects require very little land or energy to produce, and they can be produced quickly and all year round, unlike other animal feedstock such as soybeans. Insects can serve as a protein-rich substitute for the aforementioned wild-caught fish that are often used as aquaculture inputs, potentially turning aquaculture into a sustainable solution to overfishing. Netherlands-based Protix makes animal and fish feed as well as fertilizer from black soldier flies.

Crickets, fruit flies, grasshoppers, and mealworms are all also being cultivated for inclusion in consumer products in this nascent industry. Grasshopper farms like Israel’s Hargol, are racing to get their production capacity up since the demand for alternative proteins for both animals and humans remains much higher than current supply. While very secretive about their designs, many insect farming groups claim to have very high-tech operations using robotics, to create automated insect farming factories, such as Ynsect in France.

Consumer growing systems

Home paramours for almost every novel growing system exist, whether or not they’ve gone mainstream (yes even insect farms). Tabletop hydroponic systems like Plantui, aquaponic systems that have decorative fishtanks topped with produce like Grove, and even mini refrigerator-sized growing towers like Hydro Grow, are available for the shortest farm-to-table experience out there.

Your Produce Might Soon Grow In A Warehouse Down The Block

Plenty, Inc. is changing the way that we farm. Instead of modernizing agriculture by developing ways to keep fresh greens fresh throughout transportation, this San Francisco-based company is doing away with transportation — or at least a huge chunk of it, thanks to vertical farming.

Your Produce Might Soon Grow In A Warehouse Down The Block

IN BRIEF

Vertical farming is changing agriculture. With its capacity for more quality produce at cheaper costs, the San Francisco-based startup Plenty wants to help put a dent in the global food shortage — and they just received $200 million to do so.

MODERN-DAY FARMER

Plenty, Inc. is changing the way that we farm. Instead of modernizing agriculture by developing ways to keep fresh greens fresh throughout transportation, this San Francisco-based company is doing away with transportation — or at least a huge chunk of it, thanks to vertical farming.

As its name implies, vertical farming is essentially planting in stacks instead of a typical field. This method saves space and eliminates the need to acquire huge parcels of land before to grow crops. It’s an idea that’s especially attractive now that more people are opting to live in cities, and transporting fresh farm produce can be troublesome. Best of all, this can be done inside warehouses or other indoor spaces located within cities.

Plenty has received $200 million in funding — the largest investment in an agricultural technology ever — from Japanese telecommunications giant SoftBank, enough to put vertical farms in 500 urban centers with over a million people.

MORE EFFICIENT FARMING

Instead of using stacked, horizontal shelves like most vertical farms do, Plenty uses 6-meter (20-foot) tall vertical poles from which plants jut out horizontally. These are lined up next to each other, with about 10 centimeters (4 inches) of space in between. Infrared cameras and sensors placed among the plants monitor conditions regularly, and Plenty’s system can adjust the LED lights, humidity, and air composition in their indoor farms.

Image credit: Plenty, Inc./Fast Company

These plants are fed nutrients and water from the top of the poles, so this setup doesn’t even require soil. “Because we work with physics, not against it, we save a lot of money,” co-founder Matt Barnard told Bloomberg. This setup, Plenty claims, can grow 350 times more produce in a given area than conventional farms. Plus, all the accumulated water can be fed back into the system, so the process only really uses about one percent of the water that a regular farm would need. All of this means that a significant amount of fresh produce could be planted and grown in cities. This would mean good quality produce at potentially lower costs. Plenty’s San Franciso indoor farm, for example, can produce 2 million pounds of lettuce each year within a space that’s no bigger than an acre. “We’re giving people food that tastes better and is better for them,” Barnard said.

Life On Mars A Possibility With New Indoor-Farming Technology

Life On Mars A Possibility With New Indoor-Farming Technology

September 1, 2017

A US-based company has developed technology that can replicate any kind of climate inside a shipping container, bringing sustenance on a mission on Mars one step closer to reality.

The company, Local Roots Farms, has joined forces with Space X, a company that's trying to get people to Mars. (File photo/ Reuters)

A company in California says it could be the first to grow food on Mars.

Local Roots Farms has developed an indoor farm that could feed astronauts on longer-term space missions.

They say their technology will also benefit the earth as it uses less water than traditional farming techniques.

TRT World’s Frances Read reports from Los Angeles.

This High-Tech Vertical Farm Promises Whole Foods Quality at Walmart Prices

Before stepping into Plenty Inc.’s indoor farm on the banks of the San Francisco Bay, make sure you’re wearing pants and closed-toe shoes. Heels aren’t allowed. If you have long hair, you should probably tie it back.

Working in the Map Room, one of Plenty’s R&D rooms in South San Francisco.

PHOTOGRAPHER: JUSTIN KANEPS FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

This High-Tech Vertical Farm Promises Whole Foods Quality at Walmart Prices

SoftBank-backed Plenty is out to build massive indoor farms on the outskirts of every major city on Earth.

By Selina Wang | September 6, 2017

Before stepping into Plenty Inc.’s indoor farm on the banks of the San Francisco Bay, make sure you’re wearing pants and closed-toe shoes. Heels aren’t allowed. If you have long hair, you should probably tie it back.

Your first stop is the cleaning room. Open the door and air will whoosh behind you, removing stray dust and contaminants as the door slams shut. Slide into a white bodysuit, pull on disposable shoe covers, and don a pair of glasses with colored lenses. Wash your hands in the sink before slipping on food-safety gloves. Step into a shallow pool of clear, sterilized liquid, then open the door to what the company calls its indoor growing room, where another air bath eliminates any stray particles that collected in the cleaning room.

The growing room looks like a strange forest, with pink and purple LEDs illuminating 20-foot-tall towers of leafy vegetables that stretch as far as you can see. It smells like a forest, too, but there’s no damp earth or moss. The plants are growing sideways out of the columns, which bloom with Celtic crunch lettuce, red oak kale, sweet summer basil, and 15 other heirloom munchables. The 50,000-square-foot room, a little more than an acre, can produce some 2 million pounds of lettuce a year.

Step closer to the veggie columns, and you’ll spot one of the roughly 7,500 infrared cameras or 35,000 sensors hidden among the leaves. The sensors monitor the room’s temperature, humidity, and level of carbon dioxide, while the cameras record the plants’ growing phases. The data stream to Plenty’s botanists and artificial intelligence experts, who regularly tweak the environment to increase the farm’s productivity and enhance the food’s taste. Step even closer to the produce, and you may see a ladybug or two. They’re there to eat any pests that somehow make it past the cleaning room. “They work for free so we don’t have to eat pesticides,” says Matt Barnard, Plenty’s chief executive officer.

Barnard, 44, grew up on a 160-acre apple and cherry orchard in bucolic Door County, Wis., a place that attracts a steady stream of fruit-picking tourists. Now he and his four-year-old startup aim to radically change how we grow and eat produce. The world’s supply of fruits and vegetables falls 22 percent short of global nutritional needs, according to public-health researchers at Emory University, and that shortfall is expected to worsen. While the field is littered with the remains of companies that tried to narrow the gap over the past few years, Plenty seems the most promising of any so far, for two reasons. First is its technology, which vastly increases its farming efficiency—and, early tasters say, the quality of its food—relative to traditional farms and its venture-backed rivals. Second, but not least, is the $200 million it collected in July from Japanese telecom giant SoftBank Group, the largest agriculture technology investment in history.

Anthony Secviar, chef and member of Plenty’s culinary council.

PHOTOGRAPHER: JUSTIN KANEPS FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

With the backing of SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son, Plenty has the capital and connections to accelerate its endgame: building massive indoor farms on the outskirts of every major city on Earth, some 500 in all. In that world, food could go from farm to table in hours rather than days or weeks. Barnard says he’s been meeting with officials from some 15 governments on four continents, as well as executives from Wal-Mart Stores Inc. and Amazon.com Inc., while he plans his expansion. (Bezos Expeditions, the Amazon CEO’s personal venture fund, has also invested.) He intends to open farms abroad next year; this first one, in the Bay Area, is on track to begin making deliveries to San Francisco grocers by the end of 2017. “We’re giving people food that tastes better and is better for them,” Barnard says. He says that a lot.

Plenty acknowledges that its model is only part of the solution to the global nutrition gap, that other novel methods and conventional farming will still be needed. Barnard is careful not to frame his crusade in opposition to anyone, including the industrial farms and complex supply chain he’s trying to circumvent. He’s focused on proving that growing rooms such as the one in South San Francisco can reliably deliver Whole Foods quality at Walmart prices. Even with $200 million in hand, it won’t be easy. “You’re talking about seriously scaling,” says Sonny Ramaswamy, director of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the investment arm of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “The question then becomes, are things going to fall apart? Are you going to be able to maintain quality control?”

The idea of growing food indoors in unlikely places such as warehouses and rooftops has been hyped for decades. It presents a compelling solution to a series of intractable problems, including water shortages, the scarcity of arable land, and a farming population that’s graying as young people eschew the agriculture industry in greater numbers. It also promises to reduce the absurd waste built into international grocery routes. The U.S. imports some 35 percent of fruits and vegetables, according to Bain & Co., and even leafy greens, most of which are produced in California or Arizona, travel an average of 2,000 miles before reaching a retailer. In other words, vegetables that are going to be appealing and edible for two weeks or less spend an awful lot of that time in transit.

So far, though, vertical farms haven’t been able to break through. Over the past few years, early leaders in the field, including PodPonics in Atlanta, FarmedHere in Chicago, and Local Garden in Vancouver have shut down. Some had design issues, while others started too early, when hardware costs were much higher. Gotham Greens in Brooklyn, N.Y., and AeroFarms in Newark, N.J., look promising, but they haven’t raised comparable cash hoards or outlined similarly ambitious plans.

While more than one of these companies was felled by a lack of expertise in either farming or finance, Barnard’s unusual path to his Bay Area warehouse makes him especially suited for the project. He chose a different life than the orchard, frustrated with the degree to which his life could be upended by an unexpected freeze or a broken-down tractor-trailer. Eventually he became a telecommunications executive, then a partner at a private equity firm. In 2007, two decades into his white-collar life, he started his own company, one that concentrated on investing in technologies to treat and conserve water. After an investor suggested he consider putting money into vertical farming, Barnard began to research the subject and quickly found himself obsessed with shortages of food and arable land. “The length of the supply chain, the time and distance it takes,” he says, meant “we were throwing away half of the calories we grow.” He spent months chatting with farmers, distributors, grocers, and, eventually, Nate Storey.

Plenty co-founders Matt Barnard, chief executive officer, and Nate Storey, chief science officer.

PHOTOGRAPHER: JUSTIN KANEPS FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

The grandson of Montana ranchers, 36-year-old Storey spent much of his childhood planting and tending gardens with his six siblings. Their Air Force dad, who eventually retired as a lieutenant colonel, moved them to another base every few years, and the family gardened to save money on groceries. “I was always interested in ranching and family legacy but frustrated on how to do it,” Storey says. “If you’re an 18-year-old kid and you want to farm or ranch, most can’t raise $3 million to buy a farm or a ranch.”

A decade ago, as a student at the University of Wyoming, he learned about the same industry-level inefficiencies Barnard observed. He began experimenting with vertical farming for his doctoral dissertation in agronomy and crop science, and in 2009 patented a growing tower that would pack the plants more densely than other designs. He spent $13,000, then a sizable chunk of his life savings, to buy materials for the towers and started building them in a nearby garage. By the time he met Barnard in 2013, he’d sold a few thousand to hobbyist farmers and the odd commercial grower.

Storey became Barnard’s co-founder and Plenty’s chief science officer, splitting his time between Wyoming and San Francisco. Together they made Storey’s designs bigger, more efficient, and more readily automated. By 2014 they were ready to start building the farm.

Most vertical farms grow plants on horizontal shelves stacked like a tall dresser. Plenty uses tall poles from which the plants jut out horizontally. The poles are lined up about 4 inches from one another, allowing crops to grow so densely they look like a solid wall. Plenty’s setups don’t use any soil. Instead, nutrients and water are fed into the top of the poles, and gravity does much of the rest of the work. Without horizontal shelves, excess heat from the grow lights rises naturally to vents in the ceiling. “Because we work with physics, not against it, we save a lot of money,” Barnard says.

Water, too. Excess drips to the bottom of the plant towers and collects in a recyclable indoor stream, and a dehumidifier system captures the condensation produced from the cooling hardware, along with moisture released into the air by plants as they grow. All that accumulated H₂O is filtered and fed back into the farm. All told, Plenty says, its technology can yield as much as 350 times more produce in a given area as conventional farms, with 1 percent of the water. (The next-highest claim, from AeroFarms, is as much as 130 times the land efficiency of traditional models.)

Based on readings from the tens of thousands of wireless cameras and sensors, and depending on which crop it’s dealing with, Plenty’s system adjusts the LED lights, air composition, humidity, and nutrition. Along with that hardware, the company is using software to predict when plants should get certain resources. If a plant is wilting or dehydrated, for example, the software should be able to alter its lighting or water regimen to help.

Barnard, tall and lanky with a smile that crinkles his entire face, becomes giddy when he recounts the first time Plenty built an entire growing room. “It had gone from pretty sparse to a forest in about a week,” he says. “I had never seen anything like that before.”

The $200 million investment will help Plenty put a farm in every world metro area with more than 1 million residents, about 500 in all

When he and Storey started collaborating, their plan was to sell their equipment to small growers across the country. But to make a dent in the produce gap, they realized they’d need to reproduce their model farm with consistency and speed. “If it takes you two or three years to build a facility, forget about it,” Storey says. “That’s just not a pace that’s going to have any impact.” That meant they’d have to engineer the farms themselves. And that meant two things: They’d need more than their 40 staffers, and they’d need way more money.

It wasn’t easy for Barnard to get his first meeting with Son, in March. One of Plenty’s early investors had to beg the SoftBank CEO, who allotted Barnard 15 minutes. He and the investor, David Chao of DCM Ventures, jammed one of the 20-foot grow towers into Chao’s Mercedes sedan and took off for Son’s mansion in Woodside, Calif., some 30 miles from San Francisco. Son looked bewildered as they unloaded the tower, but the meeting stretched to 45 minutes, and two weeks later they flew to Tokyo for a more official discussion in SoftBank’s boardroom. The $200 million investment, announced in late July, will help Plenty put a farm in every major metro area with more than 1 million residents, according to Barnard. He says each will have a grow room of about 100,000 square feet, twice the size of the Bay Area model, and can be constructed in under 30 days.

Cutting rainbow chard.

PHOTOGRAPHER: JUSTIN KANEPS FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

Chao says SoftBank wants “to help Plenty expand very quickly, particularly in China, Japan, and the Middle East,” which all struggle with a lack of arable land. Other places on the near-term list include Canada, Denmark, and Ireland. Plenty is also in talks with insurers and institutional investors such as pension funds to bankroll its farm-building with debt. Barnard says the farms would be able to pay off investors in three to five years, vs. 20 to 40 years for traditional farms. Think of it more like a utility, he says.

Plenty, of course, isn’t as sure a bet as Consolidated Edison Inc. or Italy’s Enel SpA. The higher costs of urban real estate, and the electricity needed to run all of the company’s equipment, cut into its efficiency gains. While it’s adapting its technology for foods including strawberries and cucumbers, the complications of tree-borne fruits and rooting crops likewise neutralize the value of its technology. And Plenty has to contend with commercial farms that have spent decades building their relationships with grocers and suppliers and a system that already offers many people extremely low prices for a much wider variety of goods. “What I haven’t seen so far in vertical farm technologies is these entities getting very far beyond greens,” says Michael Hamm, a professor of sustainable agriculture at Michigan State University. “People only eat so many greens.”

Barnard says he’s saving way more on truck fuel and other logistical costs, which account for more than one-third of the retail price of produce, than he’s spending on warehousing or power. He’s also promising that the company’s farms will require long-term labor from skilled, full-time workers with benefits. About 30 people can run the South San Francisco warehouse; future models, which will be about two to five times its size, may require several hundred apiece, he says. While robots can handle some of the harvesting, planting, and logistics, experts will oversee the crop development and grocer relationships on-site.

Entering one of Plenty’s R&D rooms in South San Francisc.

PHOTOGRAPHER: JUSTIN KANEPS FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

Retailers shouldn’t need much convincing, says Mikey Vu, a partner at Bain who studies the grocery business. “Grocers would love to get another four to five days of shelf life for leafy greens,” he says. “I think it’s an attractive proposition.”

Gourmets like Plenty’s results, too. Anthony Secviar, a former sous-chef at French Laundry, a Michelin-starred restaurant in the Napa town of Yountville, says he wasn’t expecting much when he received a box of Plenty’s produce at his home in Mountain View, Calif. The deep green of the basil and chives hit him first. Each was equally lush, crisp, flavorful, and blemish-free. “I’ve never had anything of this quality,” says Secviar, who while at French Laundry cooked with vegetables grown across the street from the restaurant. He’s now on Plenty’s culinary council and is basing his next restaurant’s menu around the startup’s heirloom vegetables. “It checks every box from a chef’s perspective: quality, appearance, texture, flavor, sustainability, price,” he says.

At the South San Francisco farm—recently certified organic—the greens are fragrant and sweet, the kale is free of store-bought bitterness, and the purple rose lettuce carries a strong kick. There’s enough spice and crunch that the veggies won’t need a ton of dressing. Although Plenty bears little resemblance to a quaint family farm, the tastes bring me back to the tiny vegetable patch my grandparents planted in my childhood backyard. It’s tough to believe these spicy mustard greens and fragrant chives have been re-created in a sterile room, without soil or sun.

AeroFarms Gets $1 Million Research Grant

Plants grow at indoor vertical farming company AeroFarm's research and development facility in Newark, N.J. The company has been awarded a $1 million Seeding Solutions grant from the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research to improve controlled environment specialty crop characteristics such as taste and nutritional quality.

Photo by AeroFarms

Newark, N.J.-based AeroFarms has been awarded a $1 million Seeding Solutions grant from the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research.

The foundation is a nonprofit organization established in the 2014 farm bill, according to a news release, and the grant was celebrated by research and industry leaders at a Sept. 7 function at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

AeroFarms, an indoor vertical farming company, will match the foundation’s grant for a total investment of nearly $2 million, according to the release.

Principal investigator Roger Buelow, chief technology officer at AeroFarms, will work with Rutgers University and Cornell University scientists on using vertical farming systems technology to improve specialty crop characteristics such as taste and nutritional quality.

According to the release, the project seeks to advance crop production by measuring the link between stressed plants, the phytochemicals they produce and the taste and texture of the specialty crops grown.

The work is expected to result in commercial production of improved leafy green varieties and yield science-based best practices for farming, according to the release.

“With more than half the world living in urban areas, continuing to provide nutritious food to the burgeoning population must include envisioning our cities as places where abundant, nutritious foods can be grown and delivered locally,” Sally Rockey, executive director of the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research, said in the release. “We look forward to seeing this grant to AeroFarms catalyze innovation in vertical farming and plant production for the benefit of urban farmers and the communities they serve.”

David Rosenberg, co-Founder and CEO of AeroFarms, said in the release that the company was honored to have been selected for the award.

“This FFAR grant is a huge endorsement for our company and recognition of our history and differentiated approach to be able to optimize for taste, texture, color, nutrition and yield and help lead the industry forward,” he said in the release.

Information gained from the research will be published and presented at controlled environment agriculture industry conferences, according to the release, including events tailored to startup companies and prospective entrepreneurs.

“Pioneering initiatives like the work by AeroFarms and FFAR will help lead the produce industry with a science-backed approach to understand how to grow great tasting and nutritionally dense products consistently all year,” Tom Stenzel, CEO of United Fresh Produce Association, said in the release. “We believe that there is a need for even more public/private partnerships like this to spur breakthroughs.”

Topics: AEROFARMS FARM BILL INDOOR FARMING URBAN AGRICULTURE

About the Author: Tom Karst

Tom Karst is national editor for The Packer and Farm Journal Media, covering issues of importance to the produce industry including immigration, farm policy and food safety. He began his career with The Packer in 1984 as one of the founding editors of ProNet, a pioneering electronic news service for the produce industry. Tom has also served as markets editor for The Packer and editor of Global Produce magazine, among other positions. Tom is also the main author of Fresh Talk, www.tinyurl.com/freshtalkblog, an industry blog that has been active since November 2006. Previous to coming to The Packer, Tom worked from 1982 to 1984 at Harris Electronic News, a farm videotext service based in Hutchinson, Kansas. Tom has a bachelor’s degree in agricultural journalism from Kansas State University, Manhattan. He can be reached at tkarst@farmjournal.com and 913-438-0769. Find Tom's Twitter account at www.twitter.com/tckarst.

Life On Mars A Possibility With New Indoor-Farming Technology

They say their technology will also benefit the earth as it uses less water than traditional farming techniques.

Life On Mars A Possibility With New Indoor-Farming Technology

A US-based company has developed technology that can replicate any kind of climate inside a shipping container, bringing sustenance on a mission on Mars one step closer to reality.

The company, Local Roots Farms, has joined forces with Space X, a company that's trying to get people to Mars. (File photo/ Reuters)

A company in California says it could be the first to grow food on Mars.

Local Roots Farms has developed an indoor farm that could feed astronauts on longer-term space missions.

They say their technology will also benefit the earth as it uses less water than traditional farming techniques.

TRT World’s Frances Read reports from Los Angeles.

Global Data Collection And The Future of Indoor Urban Farming

Harper is director of the Open Agriculture Initiative (OpenAg) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Media Lab. He and a global collection of “nerd farmers” are working on a Food Computer, which closely detects – and allows you to adjust – the growing conditions of any plant in the room. Francis Lam talks with Harper about the project.

From The Future of Urban Farming

September 8, 2017

Global Data Collection And The Future of Indoor Urban Farming

by Francis Lam

Photo: Nettedotca/iStock/Getty Images Plus

The urban farming movement takes many forms, both indoors and outdoors: school gardens, community vegetable patches, fish farms in tanks. Scientist Caleb Harper believes that indoor urban farming specifically can create the best tasting, most nutritious, and least energy intensive crops anywhere in the world. Harper is director of the Open Agriculture Initiative (OpenAg) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Media Lab. He and a global collection of “nerd farmers” are working on a Food Computer, which closely detects – and allows you to adjust – the growing conditions of any plant in the room. Francis Lam talks with Harper about the project.

Francis Lam: There are so many things that make a great farm great. You start with the farmers, of course. But then the kind of sunlight it gets, the soil composition, the temperature, all sorts of factors. You’re trying to bring those characteristics to growing plants – indoors.

Caleb Harper: Exactly. If someone says the best tomato in the world comes from Tuscany on the north side of the slope with the happy cow next door, we try to factor in all of the biotic or abiotic stress – most people would call it climate – that caused those specific genetics to create the flavor that they liked. We try to figure that out and, in the process, use the least amount of resources – less water, energy, and nutrition loss from transportation – so that we can make a good product that's healthy and available in our cities.

FL: I assume that means you also pipe in audio of a happy cow mooing just to make sure that's covered?

CH: A lot of my freshmen that come into my lab at MIT, the first thing they want to do is put the plants through Mozart and then put the plants through Tupac. And you know who wins between Mozart and Tupac? Tupac! Because it's all about microvibrations, which in the natural world you'd call wind. You need wind inside of these environments because the plant gets stressed by the wind and starts to grow taller, so it's morphologically correct. Those microvibrations of Tupac really help it out.

FL: I imagine the more you do it, the more you learn what these factors are –

CH: That's a bleeding edge of science. We've never before had the ability to gather or process so much data so cheaply. Now, with advancements in robotics, sensors technology, and data processing, we can start to get at some basic science that we haven’t been able to do before.

FL: It’s almost like you're creating a virtual reality for these plants that is, in fact, reality.

CH: That's totally true. One of the things that limits agriculture and agricultural science is seasons. We go season-to-season, we try and make changes, we select for genetics that did well in that season. But we have a lot of asynchronistic or non-categorized variables during that season. Imagine you could run the season ten thousand times. If you could run the season ten thousand times, you could try all different kinds of things that you would have done, and see which one worked out the best without having to wait ten thousand years. The idea is, how can we make agriculture and plant science more like computing?

Caleb Harper

(Photo: MIT Media Lab)

FL: How are we going to get to the point where this happens on every other block in every other city? How will this scale up?

CH: Right now, it’s bubbling in the entrepreneurial realm. There are a lot of start-ups – shipping container size or warehouse size – in Japan, China, Europe, and the United States, with hundreds of millions of dollars going into this. But what I think needs to happen, and what my group is trying to be a part of, is the sharing of this knowledge so it can scale up.

There are so many unanswered questions. We need trillions of data points. We need one hundred thousand images to do any machine learning. We've taken all of our plans, software and hardware, and made it open source. You can access it for free; you can use it for whatever you want and you contribute as part of the project. It’s kind of like a citizen science for horticulture or botany. After the last year and a half, there are people in 40 countries around the world contributing to our project. They are contributing code. They are growing in the bots whatever they want to grow, whatever excites them. We are able to collect data on that, and it starts to build up this data set that we can use.

This is the way of the future. You look at Tesla open sourcing their patents so that more infrastructure can be built; it’s part of that network economy. Apple open sourcing their app developer language; this is because of our networked world. There's never been a time in human history where you can get more people working on a single problem – if you share that infrastructure. I don't think anything is more important than how we are going to feed all the people in the world with the least amount of resources and the highest amount of flavor and nutrition.

FL: This sounds incredible. Good luck to you, and I think that means good luck to all of us.

CH: Absolutely. There's a nerd farmer inside all of us. A lot of us think we don't have a green thumb. But what if a green thumb was a digital asset? What if I could download a farmer's eye that took 60 years to cultivate? That beautiful eye that can tell you what's wrong with a plant. You might come into this saying, “My houseplants are always dying; I don't know what to do with them.” What if we could make that a program? What if you literally downloaded a tomato, and that tomato meant that you put a seed in an environment that was then created by a master gardener or a master horticulturalist, or by a chef that knew what to do with this plant in the northern part of Spain to get the most beautiful expression of flavor – but we captured that as a recipe? You downloaded it, you grew it, and all the sudden, you're in the Basque region in your apartment.

FL: What other technologies do you see right now in terms of farming and agriculture that we laypeople don’t know about?

CH: In a bigger context, what I’m seeing is a general shift that’s a coming together of biologic and digital technologies. For example, rapid sequencing – the ability to get to the genetics of whatever we’re interested in very quickly. And now, the ability to edit those genetics. There is something called CRISPR (Clustered Regulatory Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats); it’s a system that makes it easy and cheap to edit something within a genome. This might be something that people are concerned about. But when you think about the fact that everything we’ve eaten in our entire life has been genetically modified because it’s been trait selected for hundreds of years down to become the corn that we eat today –

FL: Breeding sweeter and sweeter corn.

CH: Exactly. Or a bigger version of whatever we were looking for. What CRISPR is, is the ability to do what used to take many years outside, one day to do in a lab. That can radically change what we’re able to do with agriculture in the short term.

There are some amazing things going on in the microbiome. I don’t know if you’re following the conversation about human microbiome, but in the plant world, we’re saying “root microbiome.” We look at what should be in the soil. Maybe it isn’t there because the method of farming that we’ve been using hasn’t cultivated that microbiome. Maybe it was never there in the first place, for whatever reason. What microbes and bacteria would we want to put back into the soil that would cause a better plant to come out? What’s even more radical than that, is people are starting to engineer microbes. If you know the process you are trying to help, you can literally engineer a helper microbe to go into the soil to cause a more efficient plant.

Things like microsatellites and drones are getting a lot more data on our fields. There is a start-up that has recently created more data about infield farming in the last five years than the USDA has in its entire existence. Part of that is the cheaper sensors and cheaper processing power. We’re getting a very described field, the ability to modify very quickly within genome, trait select using CRISPR, and we’re looking at how we would intentionally the soil with microbes.

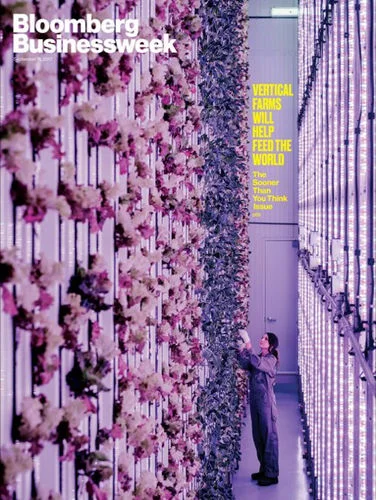

Laramie Start-Up Featured On The Cover Of Bloomberg Businessweek

- It didn’t take long for a company founded by a UW graduate student in 2011 to grow big enough to have an international reach and reputation. Bright Agrotech’s six-year growth surge was capped off this week by being featured in a cover story for Bloomberg Businessweek.

Bright Agrotech and its founder, Nate Storey have been covered closely by the Wyoming Business Report from the beginning. In 2011, when still a graduate student at UW, Storey won $10,000 in seed money in the Wyoming $10K Entrepreneurship Competition to help get his vertical vegetation towers off the ground. As part of his winnings, his growing company was planted in the Wyoming Technology Business Center (WBTC) incubator.

In 2012, Christine Langley, chief operating officer of the WTBC told the us that “We expect [Bright Agrotech] to be a very large business in the next three to five years.” It only took three.

In the fall of 2013, Whole Foods discovered Bright Agrotech’s vertical towers as a way to sell and display living organic produce in the store.

Just two years later, Bright Agrotech exited the WTBC incubator and set up shop in the ALLSOP Inc. warehouse and began working with the Laramie City Council and Laramie Chamber Business Alliance to secure a permanent building. 2015 was also the year that Bright Agrotech created the world’s largest food-wall for the USA Pavillion at the Worlds Fair in Milan, Italy. The wall featured 42 different crops along more than 7,200 square feet of growing space.

In 2016, Bright Agrotech introduced “CoolBar” a water-cooled LED lighting system to help plants grow and not cook inside a greenhouse. “Being able to decouple the light from the heat poses major benefits to indoor farmers everywhere,” Storey said at the time.

It was a busy year for the company, as the State Loan Investment Board (SLIB), approved a recommendation by Wyoming Business Council to approve a $2,685,750 grant and $209,250 loan from the City of Laramie to construct a 12,150 square-foot building to house Bright Agrotech while the Laramie Chamber Business Alliance provided a 3.85-acre lot in the Laramie River Business Park. That headquarters building is now under construction.

This June the company was aquired by a Silicon Valley firm, Plenty, a field-scale vertical farming company. Storey became a co-founder as well as the firm’s chief science offier. Storey and his co-founder, Matt Barnard, had been in communication since they met in 2013. The unique grow towers developed by Bright Agrotech – coupled with a system of dehumidifiers, infrared cameras, sensors and monitoring devices – allow as much as three times the plant growth as their nearest competetor. According to the Bloomberg cover story, Plenty’s new technology can yield as much as 350 times more produce than a conventional farm, using just 1 percent of the water. The nearest competitor, AeroFarms claims as much as 130 times the efficiency.

The combined company, simply known as Plenty has its sights set on bringing fresh food to the world. Literally. With the backing of SoftBank – which at $200 million is the largest agriculture technology investment in history – Plenty plans to build massive indoor farms on the outskirts of every major city on Earth.

The Laramie headquarters still under construction will remain part of the company, as will the 43 people currently working there, but “We’re going to need to hire a lot more people,” Story said.

Korea And The Fourth Industrial Revolution Smart Farms Swap Scarecrows For Sensors

Korea And The Fourth Industrial Revolution Smart Farms Swap Scarecrows For Sensors

Sept 04, 2017

[ILLUSTRATED BY BAE MIN-HO]

After Mr. Choe quit his high-paying corporate job early last year, he and his wife decided to move to Yeongju, North Gyeongsang, to start a farm.

Choe, a 58-year-old former quality control manager who’s done his share of physically demanding work at a number of major Korean shipbuilders, thought farming wouldn’t be much of a challenge. It took him less than a month to realize he was wrong. Growing zucchinis and trying to make a living out of it took more of a physical toll than he had anticipated. Choe and his wife have not given up on farming just yet, but a year down the line they are still looking for ways to make the work less demanding.

This is where the convergence of farming and technology may come to the rescue, ultimately enabling people like Choe to take advantage of what’s known as “smart farming.”

In a report, the Korea Rural Economic Institute (KREI), a think tank dedicated to research in agricultural development and related policy, described smart farms as “a farm that can remotely and automatically maintain and manage the growing environment of crops and livestock by utilizing ICT [information and communication technology] in [greenhouses], stables, orchards and so on.”

The report notes that in controlled horticulture, or growing plants with the aid of new technology, production increases by an average 44.6 percent and gross profit increases by an average 40.5 percent.

A farmer that adopts these smart farming techniques uses sensors to monitor the conditions in the area where plants are grown, including temperature and humidity as well as the levels of CO2 and oxygen. Data analysis is also a crucial element in smart farming, as the control unit needs to have a reference point to understand and interpret the information collected by the sensors. For instance, if past data indicates that strawberries are the sweetest when they are grown in an environment with a temperature between 20 and 26 degrees Celsius (68 to 79 degrees Fahrenheit), the system will automatically keep the temperature within that range based on the information recorded by the sensors.

The concept of smart farming is still considered relatively new in Korea, where the majority of farmers come from an older generation that are generally less willing to adopt a completely new approach to growing and maintaining crops.

But more people like Choe are giving up their jobs in the city and turning to farming.

According to data from Statistics Korea, the number of people leaving the city to take up farming has jumped from 17,464 in 2011 to 20,559 last year.

Still, the growing interest in farming hasn’t been able to stop the steady decline in the number of farmers. According to the statistics agency, there were 2.96 million farmers in 2011. This number plummeted to 2.5 million by 2016.

“The farming population in Korea continues to fall and age,” said the KREI report. “Farming methods that rely on human labor are reaching their limit, not to mention the shrinking investment in the agricultural sector.”

Even so, Koreans are reluctant to change their farming techniques.

“Most farmers don’t know what to do with the technology even if it’s installed on their farms,” said the report. “This is because, despite advantages such as an increase in productivity and reduction of labor costs, there are no previous models that farmers can follow, or they lack confidence in the effectiveness of smart farming.”

Smart farming in practice

While smart farming is yet to find a home at most farms in Korea, it has already been put into practice in other parts of the world.

Even back in the early 2000’s, major farms in the United States began to use automated trackers and machinery to more effectively prepare their fields with less manpower. More recently, the level of automation has increased, as has the precision of the equipment.

John Deere, the leading agricultural equipment maker in the United States, has included GPS in its tractors and machines for roughly a decade already. The system tracks the movement of the tractors, most of which are automated, and makes sure they don’t cover the same ground twice, increasing the efficiency of the automated system.

Monsanto, an American multinational agricultural and biotechnology company, is another leader in the industry that’s trying to bring new technology into agriculture in the United States.

One of the new areas that the company has dived into is the field of data science.

Yong Gao, the director of corporate engagement Asia and Africa for Monsanto and president of Monsanto China, told the Korea JoongAng Daily during an interview in Seoul on Aug. 17 that data science can be used in farming to optimize the size of the yield.

“If we can get all the factors [that maximize production] and optimize the function of crop yield [which combines factors such as the genes of plants, environment and farming practices with other variables], then we can maximize the yield,” Gao explained. Data science enables the analysis of these factors.

Gao provided analysis of historical weather data as an example, explaining that accumulated data on weather during the farming season can help farmers predict weather patterns that might affect their crops in the future.

Nearly 200 million acres of farms in the United States have adopted Monsanto’s climate field-view platforms, according to company data.

Investors don’t shy away from putting their money on smart farming start-ups in the U.S. either.

In May this year, a U.S. agriculture group AeroFarms raised more than $34 million from investors around the world. The company runs indoor farms which are stacked vertically to maximize space. They grow produce such as lettuce using aeroponics, which is the process of growing crops in a misty environment without using soil.

The Korean situation

There are, however, home-grown start-ups that are trying to spread smart farming in Korea.

Farmpath, an agriculture tech company based in Daejeon, offers the most common smart farming solution to Korean farmers.

One of its services, titled FarmNavi, collects, analyzes and controls the setting of greenhouses via hardware such as sensors. The monitoring is done through a farmer’s smart device or a kiosk that’s installed near the greenhouse. The system uploads the data into a cloud system provided by the company and the accumulated data is analyzed and compared to the information gathered from other users in order to optimize growth and maximize yield.

Jang Yoo-seop, a computer-programmer-turned entrepreneur, started the company in 2011 after realizing that there was a dearth in new technology in the agricultural industry.

“I was asked to create a software program that can manage a farming cooperative with some 60 farmers,” explained Jang. “But there was no request for software updates from the cooperative, which made me realize that the industry is essentially in a rut when it comes to technology.”

Jang’s parents, who had worked hard to raise livestock for nearly four decades, were heavily in debt. This led him to realize that farmers need to adopt new technology so that their labor is not wasted.

Jang also realized over the years that even with an improved yield, farmers are not compensated properly because of the way agricultural products are commonly sold in Korea. Normally, a farmer sells crops by box to a middle man. The middle man puts them up for auction at markets around Korea, which means the price that they pay the farmers can fluctuate greatly depending on demand, which also varies by region.

For this reason, Jang decided to help farmers keep track of their produce.

Agrisys was developed for this purpose. The system gathers all the data relating to a farmers produce, including where the crops were produced and how much they were ultimately sold for. Over the years, the system can even estimate the going rate of products and recommend where crops are likely to fetch the highest price at certain times of year.

Agriculture in the city

While Jang’s company bet on adding technology to traditional farms, Leo Kim of n.thing decided to develop a whole new approach to growing plants.

His business model begins with a simple and small pot, where herbs such as basil are grown. While the pots look small, they are topped with various sensors that monitor the condition of the plants inside.

“We call it the smart pot, equipped with sensors that can track the moisture in the soil and the temperature, as well as other factors crucial to the growth of the plants,” Kim explained.

Kim’s company started in January 2014 with the seed money his team earned by winning an award at a start-up competition sponsored by Google. He was given an opportunity to pitch his company in London. Five minutes into his pitch, he had already received an offer from a British company to invest $150,000.

He took these pots to the next level and created a complete farming ecosystem in a shipping container. This container, which provides farmable space equivalent to 1,322 square meters, is equipped with not only sensors but also LED lights and temperature controllers. n.thing sold the container farm to a company in Denmark in August.

“There are needs overseas for this type of farm because it allows people to grow vegetables even in the middle of a city,” said Kim. Demand for his container farms comes from countries such as the Middle East and Singapore as well. Ultimately, Kim envisions anyone living in a city will be able to grow their own vegetables using these plants.

Plant food from fish

Manna CEA, a startup based in Jincheon, North Chungcheong, has been developing a farming ecosystem that defies climate change.

The company adopted an aquaponics system for its farms, which relies on fresh water fish to produce bacteria that plants can feed on.

“Manna CEA has improved proven aquaponics production methods by developing proprietary technology that controls the levels of macro and micro nutrients,” said the company spokesperson.

The system, according to the company, uses 90 percent less water than traditional farming systems while nearly doubling the yield. It is also pesticide free, which has became a major issue among Korean consumers after the recent contaminated egg scandal.

Manna CEA has raised over $13 million in venture capital, according to company data.

There are, however, hurdles to jump over for tech companies hoping to operate in the local agriculture sector.

One of the important tasks is to raise awareness among farmers that they need to change their methods in order to increase productivity, even against unfavorable conditions such as natural disasters.

Since a number of free trade agreements were signed with countries such as Chile and the United States in recent years, the quantity of imported agricultural products has nearly doubled. The total in 2004 stood at about $14.5 billion. The figure catapulted to about $30.5 billion by 2015.

Local farmers are unable to cope with natural disasters and other unfavorable conditions, leading to a fall in production. As a result, the production of locally grown products dropped over the years, causing imports to increase. For instance, the market share of homegrown carrots has fallen below 50 percent with the fall of production in Korea. “The production of carrots plummeted due to [unfavorable weather conditions such as] the heavy rainfall in September, 2004 and typhoons in 2007 and 2012,” said Ji Sung-tae, a senior researcher at KREI. “This led imported carrots to take the bigger share of the pie in the domestic market.”

“The dynamics of farming are changing rapidly,” said Kim of n.thing. “For instance, most strawberry farms in Indonesia had to close down because they could no longer grow strawberries because of climate change. Modern farming must be able to cope with such changes.”

There is also a lack of technological understanding among senior officials.

“A lot of information technology companies put their foot into the industry but end up leaving because of a lack of government support, which tends to lean more toward spending money for hardware,” explained Jang of FarmPath. “But software to control the hardware is equally - if not more - important because software programs allow this equipment to react properly to farming conditions that can often change.”

BY CHOI HYUNG-JO [choi.hyungjo@joongang.co.kr]

This Urban Farmer Feeds Old Age Homes Through His Hydroponic Farm

Hydroponics is a subset of hydroculture. It is a method of growing plants using mineral nutrient solutions in water. These plants grow directly in water and require no soil. The two important factors to be controlled include the nutrients in the water, as well as the air temperature.

This Urban Farmer Feeds Old Age Homes Through His Hydroponic Farm

The produce from his hydroponic farm will help feed underprivileged senior citizens in old age homes and NGOs, with none of it being commercially sold for profits.

Ever wondered what it would be like to grow your vegetables at home? One might looked puzzled and say, “Sure! But in an urban setting? Is there even enough space?”

Well, one program manager based in Singapore is on a mission to change the concept of traditional agriculture by practicing hydroponic farming on unused spacious rooftops.

Srihari Kanchala is not only focused on growing produce locally but aims to impact the lives of senior citizens. The produce from his hydroponic farm will help feed underprivileged senior citizens in old age homes and NGOs, with none of it being commercially sold for profits.

“Urban farming seemed to be the best option not only to promote locally grown vegetables and fruits but also utilize unused open spaces, in the concrete jungle that the cities have turned into,” says Srihari

What is hydroponic farming?

Hydroponic farming

Hydroponics is a subset of hydroculture. It is a method of growing plants using mineral nutrient solutions in water. These plants grow directly in water and require no soil. The two important factors to be controlled include the nutrients in the water, as well as the air temperature. Even though the effort one has to put in is double than that of outdoor agriculture, the method allows an urban farmer to grow veggies efficiently year-round.

This method of farming uses water and space efficiently. Most experts deem it the ultimate future of farming.

Read more: This Software Engineer Sold His Company to Start a Vertical Hydroponic Farm in Goa

Is Urban farming a new concept?

Well, no! You can trace the history of urban agriculture to 3,500 BC when Mesopotamian farmers set aside plots in their growing cities to carry out farming. During World War II, urban farmers had what came to be called ‘victory gardens’ that produced crops to feed underprivileged neighborhoods too. One of the prime reasons for the implementation of this concept is the lack of clean produce. It is expected to pick up pace in India.

Speaking about the inspiration behind Urban Chennai, Srihari told Milaap, “One of the biggest examples of the urban citizens helping each other during crisis was Chennai floods. That inspired me to do something and contribute back to the society.”

The idea behind the initiative is to encourage and promote small communities to grow healthy fruits and vegetables locally. “I believe that food brings people closer, which in turn brings communities together,” he says.

Srihari’s goal is to help apartments, gated communities, and corporate offices with large terrace spaces join hands and grow healthier vegetables, not only for their personal use but also share what’s left with underprivileged communities that can’t afford meals.

The financial capital investment for hydroponics even though on the higher end of the scale, is

cost effective and energy efficient. It can provide more yields, ensuring surplus locally grown produce at a lesser cost.

Charity and experiments, all begin at home. So, Srihari wants to start this project by transforming 1,000 sqft of his family rooftop and convert it into a model urban farm and community space.

Technology used after funding

Srihari has received financial help from his family – his father, Mr Gopikrishnan, his father-in-law, Mr Chandrasekaran and his cousin, Mr Sreevatsava, all of whom are based in Chennai.

The urban farmer’s 1,000 sqft greenhouse is built using polycarbonate instead of plastic sheets. This helps the farm withstand the heavy rains and storms that Chennai is infamous for.

To ensure natural ventilation, it has side openings and an insect mesh over the top. The power requirement for the greenhouse is very minimal.

To ease problems of controlling leaf temperature, Srihari has installed Aluminet screens on the top that bounce off 50% of the sunlight. This helps them control the temperature and ensures the plants don’t burn out.

Control panel and automation tools that ensure very minimal work is required.

Without these aluminet screens, the greenhouse temperature would be 8-10 degrees above the temperature outside. So, even the process of controlling temperature is 100% natural without the use of huge mechanical exhaust fans.

An installed RO Unit(Reverse Osmosis water filter) ensures clean water supply to plants.

This 1,000 sqft place can grow 1600 plants at any given point. Once the plants are transplanted into the grow systems, they don’t need any manual work as they are irrigated automatically until harvest.

There are sensors that monitor the amount of nutrients given to the plants and control it as per requirements. So, the urban farmer only intervenes at the harvest stage.

This urban farm grows vegetables such as tomatoes, brinjals, capsicums and greens like spinach and lettuces. In addition, a lot of herbs like basil, fenugreek, coriander, and curry leaves are also grown.

“I see this project as a means of bringing huge difference. The whole thing seems more personal and fulfilling,” he says.

A newly imported vertical Aeroponics system from Germany is now allowing them to grow more plants in a space as tiny as 20sqft in a vertical tower. Is aeroponics the future then? Well, it’s hard to predict but it certainly more water efficient than hydroponic farming.

(L) Aeroponics (R) Foggers that automatically turn on when the humidity inside the greenhouse goes below 50.

You can connect to Srihari at Srihari@me.com

FFAR Partners With AeroFarms on $2M Precision-AG Research Project

FFAR Partners With AeroFarms on $2M Precision-AG Research Project

09/07/17 5:00 PM By Daniel Enoch

KEYWORDS AEROFARMS DAVID ROSENBERG FFAR GRANT PRECISION FARMING ROGER BUELOW SALLY ROCKEY VERTICAL FARMS

WASHINGTON, Sept. 7, 2016 – The Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research today announced a $1 million grant to New Jersey-based AeroFarms LLC, a leading vertical farming company, for a research project on precision agriculture. Aero Farms will match FFAR’s grant for a total investment of nearly $2 million.