Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Green Sense Farms Reaches Crowdfunding Goal on Day 1

Green Sense Farms, an indoor farm company based in Portage, has raised more than $120,000 in a crowdfunding campaign.

Green Sense Farms, an indoor farm company based in Portage, has raised more than $120,000 in a crowdfunding campaign on startengine.com.

The market-leading company, which raked in $788,000 in revenue last year and just opened its first farm in China, reached its minimum goal of $100,000 on the first day but hopes to raise up to $1 million to build a network of indoor vertical farms. These would be built at perishable food distribution centers owned by large grocery stores and institutional campuses that serve a lot of food daily, such as at hospital cafeterias.

“We’re not subject to rain or drought," Founder and CEO of Green Sense Farms Robert Colangelo said. "We precisely control the indoor environment, to create the perfect conditions for our plants to grow year-round, every single day.”

Last year, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission adopted rules that allow companies to sell securities through crowdfunding, which SEC Chairwoman Mary Jo White said would give smaller companies a more innovative way to raise capital while protecting investors.

Companies can go online to raise up to $1 million through crowdfunding over a 12-month period. They're required to disclose independently audited financial information, including from tax returns, and the crowdfunding platforms have to provide investors with disclosures and educational materials.

Green Sense Farms, which reports having $2.6 million in assets, grows GMO-free leafy green vegetables indoors, using less water and land than traditional agriculture. The company says more sustainable farming practices are needed because climate change is reducing the amount of arable land and the world's population is projected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050.

"Green Sense Farms has been the fortunate recipient of numerous stories about our exciting innovative indoor vertical farming technology," Colangelo said. "All this press has generated many inquiries from individuals asking how they can invest in our sustainable farm. We’re pleased to announce that the recently released crowdfunding regulations now allow for individuals to make direct equity investments in growth companies like ours."

The company, which started with a 20,000-square-foot farm in Portage, is seeking investments of at least $100 to fund R&D for new farm designs and to expand its network. It's eyeing indoor farms near colleges, hospitals, military bases and corporate campuses, including abroad in Canada, Scandinavia and China.

"Just as Green Sense Farms has disrupted produce distribution and cut out the middleman, the new crowdfunding regulations have democratized the capital markets, allowing individuals the opportunity to take advantage of public offerings without the use of traditional stock brokers," Colangelo said.

For more information, visit www.startengine.com/startup/green-sense-farms-llc.

15 Ways Urban Farming Can Revitalize a Neighborhood—And Help Farmers Too

What if farms and food production were integrated into every aspect of urban living?

15 Ways Urban Farming Can Revitalize a Neighborhood—and Help Farmers Too

What if farms and food production were integrated into every aspect of urban living?

By Michael Ableman / Chelsea Green Publishing

September 8, 2016

Friendly team harvesting fresh vegetables from the rooftop greenhouse garden and planning harvest season on a digital tablet

Photo Credit: LUMOimages/Shutterstock

[Editor's note: What if farms and food production were integrated into every aspect of urban living—from special assessments to create new farms and food businesses to teaching people how to grow fruits and vegetables so farmers can focus on staple crops? That’s the crux of Michael Ableman’s Urban Food Manifesto, which has been ten years in the making and is spelled out in his new book, Street Farm. The book tells the story of Sole Food Street Farms, and the role it has played in revitalizing not only a neighborhood, but the lives of its individual farmers. The urban farming manifesto below—as told through Street Farm—is a story of recovery, of land and food, of people, and of the power of farming and nourishing others as a way to heal our world and ourselves. You can also check out this Q&A with Ableman, where he describes in more detail the promise of urban farming.]

I have been developing the following 15-point Urban Food Manifesto over the last ten years.

Some of the ideas may sound radical; others will likely seem terribly obvious.

Some are practical, some more ideological, but either way they are focused on the municipal and on individual ways to address what I consider to be some of the most prominent challenges in how we feed ourselves.

1. Every municipality should establish publicly supported agricultural training centers in central and accessible locations. I’m not talking about think tanks or demonstration gardens. I’m talking about working urban farms that model not only the social, cultural, and ecological benefits of farming in the city, but the economic benefits as well. We can talk about all of the wonderful reasons to farm in urban areas, but until we can demonstrate that it’s possible to make a decent living doing it, it’s going to be a tough sell.

2. Regular folks are now so removed from the work of farming that they need to literally see what’s possible. They need access to those who have maintained this knowledge and those who are serious and active practitioners. Every city should have teams of trained farm advisers in numbers proportionate to the population devoted to urban food production. Those agents should operate out of their local urban agriculture centers to run training workshops and classes; they should also venture out into the community to provide on-site technical support in production, in marketing, and in food processing and preparation.

3. The nutrient cycle that once tied farms with those they supplied has been interrupted. We need a full-cycle food system that allows for the return of organic waste via central regional composting facilities that can support the nutrient needs of both urban farms and farms on the fringes of our urban centers. Every community could be composting all its cardboard, paper, old clothing, shoes, restaurant and grocery store waste, and on and on. We need to reduce what comes into our communities from elsewhere, but we also need to reduce what leaves those communities, especially if it has nutritional or soil conditioning values for our land.

4.My fields at Foxglove Farm have as many rocks as grains of soil. Removing those rocks represents a huge amount of work for me, but each one of those rocks also represents an enormous amount of embodied energy, if I could just release it. Every community should own a portable rock grinder that could be taken to farms and used to grind rocks in and around fields that contain essential minerals now being mined elsewhere at great ecological cost. There are huge holes in the world, entire mountains removed, to supply minerals such as gypsum and lime and rock phosphate to our farms. We cannot talk about a sustainable agriculture unless we address where the minerals—especially phosphorous—are going to come from.

5. We’ve all heard about peak oil; we need to prepare for peak water and peak phosphorous. We can grow food without oil, but we cannot grow it without phosphorous and water. Phosphorous is a mined mineral, which now has limited reserves, most of which are located in China, Morocco, and the Western Sahara. Some scientists believe that at the rate we now use it, remaining reserves will be depleted within fifty to one hundred years.

6. Let’s get over our phobia around human waste, stop spending billions of dollars to flush it away and pollute our rivers and oceans, and start recycling it onto our farms and gardens. Urine is the best local source of phosphorous, and we need to figure out creative ways to recycle it.

7. Every community should support the construction and funding of a permanent covered year-round farmers market space in a dominant central location. Providing this type of physical space is just as important to our civic health, if not more, as the public swimming pool, the sports fields, schools, churches, and libraries.

8. Every new permit for a housing development should be contingent on inclusion of an approved food-production component on a scale relative to the number of people who will live in the development. And every new office or retail building should be engineered for a full-scale rooftop food production component, including greenhouses warmed by the spent heat vented from the building.

9. Every neighborhood, school, and church should be required to restructure existing institutional-kitchen facilities to accommodate cooperative canning, freezing, and dehydrating services for their neighborhoods during non-peak hours.

10. Every real estate transaction should include a small urban farmland preservation tax from which lands could be purchased specifically for the production of food, and those lands could have protective easements that require agricultural use in perpetuity.

11. A great deal of privately owned arable land currently lies fallow. This land could be made available to new farmers under long-term leases. We need to recognize that there is not necessarily any relationship between landownership and land stewardship. The only requirement for landownership in our society is access to capital. That’s not enough. I believe that ownership of land should come with a set of responsibilities.

12. Building inspections are common practice prior to many real estate transactions; we should require land inspections, including ecological assessments and baseline documentation, on every piece of land over five acres. Every land purchaser should be required to attend a stewardship and restoration training course based on the particularities of that piece of land. This will help move land away from its status as commodity and bring some sense of stewardship into ownership.

13.When I was in school my favorite classes were wood shop, metal shop, mechanics, and home economics, which included cooking and sewing. Those subjects were well respected. I looked forward to shop class far more than math or science or English. It was a time when I could make something real and tangible. (Every wood shop teacher I’ve known was missing a finger or two, and I am sure that was a requirement for those positions. I made the connection very quickly between those missing fingers and the machines we worked with.) Life skills classes are coming back into schools, but we need to give farming and cooking and mechanics and plumbing and carpentry the same status and attention as math or English or the sciences.

14. It sounds radical, but in the future full-time professional farmers may no longer have the luxury of raising fruits and vegetables. This should become the responsibility of individuals and families to grow for themselves in their front and backyards, on their balconies and rooftops, and in community garden plots. We could probably survive without another carrot or tomato, but we cannot live without grains and beans and protein sources.

15. Every municipality should initiate a phase-out of all home lawns—effective immediately—but they must also provide neighborhood training programs and technical support for home- and building owners to replace those lawns with food production.

It may be that along with growing food, the real work of farmers in the future should be seen as the sequestration of water and carbon. Anyone who has land, or is managing land, has a huge opportunity and a responsibility to address two of our greatest global challenges—water and climate.

Slowing and spreading surface water and allowing it to percolate and not run off, along with learning to use land and improve soils to store and hold carbon, are urgent and essential roles that farmers need to play now and into the future.

Michael Ableman is the cofounder and director of Sole Food Street Farm and an early proponent of the urban agriculture movement. He has created urban farms in Watts, California; Goleta, California; and Vancouver, British Columbia. Ableman has also worked on and advised dozens of similar projects throughout North America and the Caribbean, and he is the founder of the nonprofit Center for Urban Agriculture. He is the subject of the award-winning PBS film Beyond Organic narrated by Meryl Streep. His previous books include From the Good Earth, On Good Land, and Fields of Plenty. Ableman lives and farms at the 120-acre Foxglove Farm on Salt Spring Island in British Columbia.

How to Grow Crops Without Sun, Soil or Water

A massive new indoor farm is about to open in New Jersey

How to Grow Crops Without Sun, Soil or Water

By Gillie Houston Posted September 08, 2016

A massive new indoor farm is about to open in New Jersey.

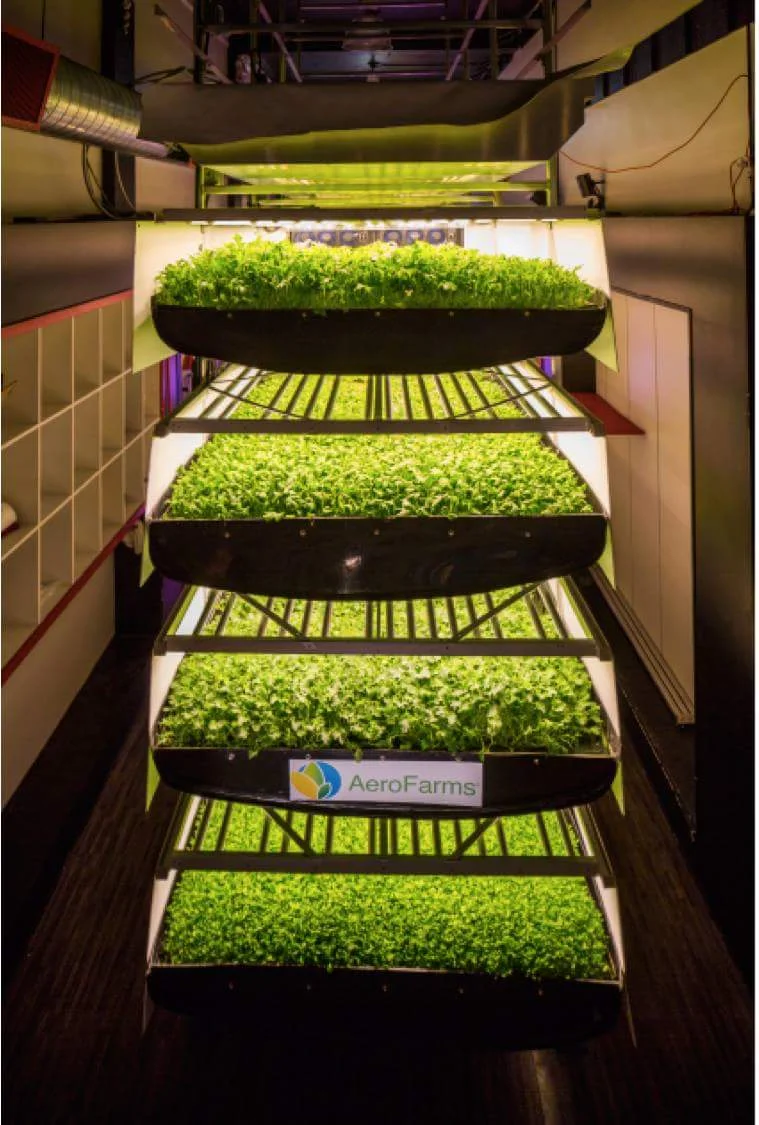

When you think farm, you might imagine sun-drenched fields of fertile soil. You probably don't imagine a very large building in Newark, New Jersey. But AeroFarms, a startup that's developed technology allowing plants to grow without sunlight or dirt (and with very little water), might be about to change that.

Related

- Elon Musk's Brother Launches "Urban Farming Accelerator" in Brooklyn

- Do Farm Subsidies Cause Diabetes?

- Funiture Giant IKEA Wants to Help Restaurants Build Their Own Indoor Farms

According to CNN, the company's first 69,000-square-foot farm is slated to open in Newark, New Jersey this September and will produce leafy greens and herbs, like kale and basil. If this sounds a bit dystopian, consider that this approach could have major environmental benefits: AeroFarms says its new structure will require 95 percent less water than the average outdoor farm.

The farm's technological design was inspired by the aeroponic farming techniques already used by astronauts at the International Space Station. At the AeroFarms facility, humidity, temperature, and light are all strictly controlled to create the most growth-friendly environment possible—free of seasons, days or nights. Each of the plant beds, which will cycle through 22-30 harvests every year, grows on a cloth made of recycled materials, under which their roots are misted with a nutrient solution. LED lights replace the sun and shine at the optimal wavelength for each plant.

AeroFarms founder David Rosenberg says the company anticipates the large-scale vertical farm will produce 2 million pounds of greens a year, setting a precedent for the potential of urban indoor farming. The tech entrepreneur, whose ambitions extend far beyond the farmers market, hopes that the technology his company is pioneering will soon be able to help feed the 54 percent of the world's population who live in urban areas, where growing fresh ingredients is difficult. "We are building this company to be wildly impactful. Not just to build a few farms, but to change the world," Rosenberg says.

Though the lack of soil usage in the growing process means AeroFarms crops aren't eligible for organic certification, all of the plants grown in the facility are free of pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides, and use non-GMO seeds. The company also collects extensive data from their plants in order to improve their growth algorithms and future crops. "We build our own software, which take images of leaves to understand height, width, length, stem ratio, curving, color, spotting and tearing," says Rosenberg of the farming method.

Co-founder Marc Oshima, says their crop beds—which the company currently sells exclusively to local markets, shops, and restaurants—are highly computerized, but still require human touch. "We think of ourselves as plant whisperers, listening and observing everything we can do to optimize our plants," he says. "Our growing approach is really leading the way, marrying biology, engineering, and data science."

The Farm that Runs Without Sun, Soil or Water

(CNN) What do you get if you cross a tech entrepreneur with a farmer?

(CNN) What do you get if you cross a tech entrepreneur with a farmer?

The world's largest, and possibly most sophisticated indoor farm -- where greens grow without sun, soil or water.

Well, almost no water. AeroFarms, the company behind the venture, say they will use 95% less water than a conventional outdoor farm.

Set to open in September in Newark, New Jersey, the 69,000-square-foot farm will be hosted in a converted steel factory. It combines a technique called "aeroponics" - like hydroponics, but with air instead of water - with rigorous data collection, which will help these modern farmers figure out optimal conditions for growth.

The goal? To produce tall, handsome, tasty baby greens and herbs such as kale, watercress and basil.

Fighting a looming food crisis

This will be the largest farm of its kind in the world in terms of production capacity: 2 million pounds of greens a year, according to Aerofarms founder David Rosenberg.

But the company's ambitions go beyond selling vast amounts of veg. They also hope to provide an answer to a looming food crisis.

The world's population will hit 8.5 billion by 2030, according to UN estimates, meaning many more mouths to feed.

Most people now live in cities, with 54% of the world's population already living in urban areas.

Rosenberg says innovation is urgently needed to feed everyone, and urban farming might be part of the solution.

"We are building this company to be wildly impactful. Not just to build a few farms, but to change the world."

How it works

Inside the farm, there are no natural seasons, nights or days. Light, air humidity and temperature are all tightly controlled.

As soon as one harvest is in, another begins -- each plant is expected to yield between 22 and 30 harvests a year.

Long rows of LED tubes shed light at the exact wavelength each plant needs to thrive. Instead of soil, the plants are grown on a cloth made from recycled materials, and their roots are misted with a solution of nutrients.

The company says their method is superior to more commonly used indoor farming techniques like aquaponics and hydroponics, which require much more water, and that the plants taste the same, or even better, than their conventionally grown counterparts.

Aeroponic farming techniques have been used before. NASA astronauts use it to grow food at the International Space Station, for example, and home-grow DIY kits can be ordered from a number of companies online.

Farming with algorithms

To make sure the greens have everything they need, the company collects data from the plants to create algorithms for growth.

"We built our own software which take images of leaves to understand height, width, length, stem ratio, curving, color, spotting and tearing," says Rosenberg.

The light is altered to fit each plant

The long rows of so-called growing towers are more like computers than farms, with sensors everywhere observing the process. Every now and then, one of the farmers does an inspection to ensure all is well, explains co-founder Marc Oshima.

"We think of ourselves as plant whisperers, listening and observing everything we can do to optimize our plants. Our growing approach is really leading the way, marrying biology, engineering, and data science."

Their farms are partly run on renewables such as solar power, but what really gets the carbon footprint down is bypassing extensive transportation of the produce by only selling the greens to local markets, shops and restaurants.

Staying local is part of the philosophy. "We have had some request to go nationwide. It's tempting, but seems counter to our mission of locally produced food," Rosenberg says.

Beyond organic?

In addition to ultra-low water usage, not using any soil further reduces the environmental impact.

The crops are currently sold at a 20% premium, similar to organic and locally produced food, but because no soil is involved, they cannot get an organic certification, although some retailers consider them to be beyond organic, Rosenberg explains.

The closed-loop system uses only non-GMO seeds and no pesticides, herbicides or fungicides, and so it reduces the harmful agricultural run-off into the environment, says Rosenberg.

"I think we are going to have a bigger and bigger impact on leafy greens and other crops in the future. And the future is going to be very different, in large part because of data."

By Sophie Morlin-Yron

Motorleaf Is Nest Meets Lego For Next-Gen Agriculture

The world of agricultural technology, or Agtech, is rapidly evolving.

Motorleaf Is Nest Meets Lego For Next-Gen Agriculture

The world of agricultural technology, or Agtech, is rapidly evolving.

It’s automating laborious tasks and providing farmers and growers with greater knowledge and insight into their crops than ever before. As technology evolves so does the needs of the farmer and the growing environment. Around 20% of the world’s food production is grown within cities rather rural areas and inherent in this is the multi-billion dollar industry of indoor growing and hydroponics.

The industry includes $5 billion in urban farming in the US and $5.7 billion for legal cannabis production.

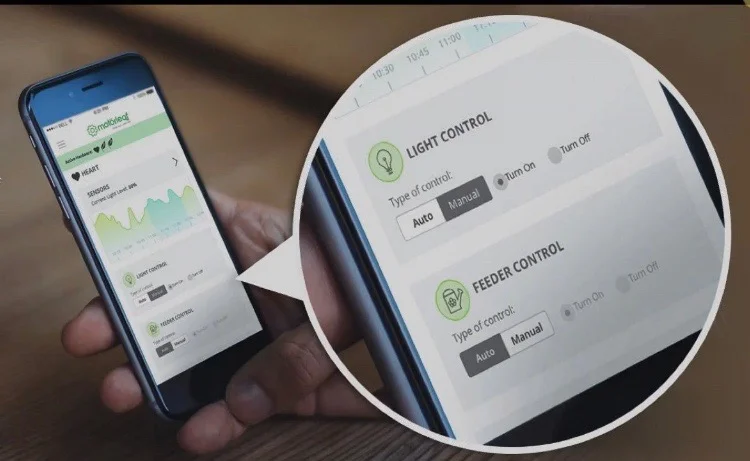

Agtech company motorleaf have released the world’s first wireless monitoring, motion detection and automated growing system for hobby and industrial growers. I spoke to CEO and co-founder Ally Monk to learn more.

According to Monk, the idea originated when as a keen indoor hobby gardener, motorleaf’s co-founder and CTO Ramen Dutta wanted to go on holidays and needed a system to take care of his plants in his absence:

“Ramen was going on vacation, but he had the problem of what would happen to his plants in his absence. He looked at the market and assumed there would be something like a smart home system akin to google Nest but there was nothing. So he started making a HUB that could monitor what was going on and automate a range of appliances such as the water chiller and water level, air temperature, webcam, heating, and cooling. He soon realized that other indoor farmers were interested."

How motorleaf works

The Heart

Motorleaf has created a system that can automate and monitor an indoor growth area with up to 5 acre coverage. Their hardware, described by some as “Nest meets Lego for agriculture” is designed to be plug-and-play, and the grower decides which part of their plant operation they control/monitor and automate. It consists of four modular units:

- The Heart collects Air Temp, Humidity, & Light Level data. Users can connect any lighting hardware, and feeder pump- and start automating their operation in seconds.

- The Power Leaf connects wirelessly to the Heart which tells them when to turn on and off, based upon pre-set times or sensor readings from the Heart and Droplet.

- The Droplet monitors everything that’s connected to a grower’s water reservoir. Every 4 seconds The Droplet wirelessly sends data to The Heart, information on water level, temperature, PH level, and nutrient levels.

- The Driplet allows growers to automate the delivery of PH and Nutrients, again based upon timer setting or actual live grow conditions.

The system is agnostic, retails for about $1,500 and contains free software which facilitates custom settings, so the motorleaf hardware will automate the grower’s equipment and adjust to their crop’s needs. It’s available online and offline as many growers do not have WiFi in their crop space. It also alerts the grower to any problems that need attending to.

More importantly, it also involves intuitive efforts in predicting and anticipating the needs of the plants. Monk says:

“We’ve never been able to speak to plants but now through technology we can listen to them through their data, we can then understand what they need and feedback instructions to the equipment that’s looking after them so we can best serve their crops.

He also notes the many people’s depiction of the farmer outdoor engaged in manual labour as not entirely actually noting “The farmer of the future looks after his farm through his mobile phone and tablet.”1 He adds that indoor growers in particular have needs which can be more complex than traditional farming:

“When you start growing indoors you have to mimic nature, they have worry bout all the things they have to control indoors such as PH; nutrients, humidity, light, air temperature. How are they controlling it? Switches, controllers, some software and in many cases people are still using pen and paper. Urban farming is on the rise but the technology that looks after this is really lagging behind.”

Motorleaf is well-timed to respond to an emerging market. They receive receives 40,000 data points per customer per week and therefore can start predicting a crop’s needs, solving potential problems before they exist. Also, the start-up plans to use its network of data and growers to connect users to each other – on an opt-in basis – to share data, plant recipes and knowledge.

With the growth in indoor agriculture, hobby farmers and small to medium enterprises will soon benefit from effective IoT technology that enables smart crops and smart farming.

By Cate Lawrence

SAPS: Using LED lighting for growing puts crops in best possible light

Food: It’s what makes the world go ‘round. This, and air and water, you know, the essentials or fundamentals.

Number 5 in the Sustainable Agricultural Practices Series.

Food: It’s what makes the world go ‘round. This, and air and water, you know, the essentials or fundamentals.

Efficiency, meanwhile, is responsible for practices, such as growing foods, to be improved; streamlined in some cases. And, innovation is what allows efficiency to take place.

Hydroponic growing technique

One innovation in agricultural practices is the application of light. Outside, light is provided by the sun. Inside growing, on the other hand, is another matter entirely. What we’re talking about here is specialized lighting application inside greenhouses, for example, of light-emitting diode (LED) lighting as a way to improve inside growing conditions for crops and plants grown in this manner.

It’s becoming a more viable way of growing food indoors. It’s also much more efficient.

“Hidden inside the prominent Philips lighting building in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, is the state-of-the-art GrowWise Center,” writes Vegetable Growers News correspondent Melanie Epp in: “Lighting the way: LED lighting solutions create a recipe for optimum plant growth,” the Sept. 2016 VGN cover story. “Here, researchers work to provide tailor-made LED light growth recipes for producers who wish to grow healthy, quality food indoors year round. The facility is concentrating its research on optimizing recipes for leafy vegetables, strawberries and herbs. Other areas of research are looking at growing wheat and potatoes indoors.”

Global director of city farming for Philips is Gus van der Feltz, who emphasizes that through its research production of food grown on the local level (and this could include urban settings) can be enabled around the world. The result is conservation of land and water, less waste and reduced need for shipping produce to distant markets, Epp brought to bear in the “Lighting the way” piece.

More LED lighting benefits

But LED lighting for indoor growing goes beyond even this. “LED lighting has improved the taste, quality and health of vegetables; reduced losses due to pests, disease and weed pressure; and reduced overall energy costs, said Robert Colangelo of Green Sense Farms in Illinois,” related Epp. All of these pluses surely mean one thing: air-quality improvement. Additionally, there is no dust being kicked up on account of farm tractor disking (tilling) and plowing of land that are common in field-farming practices. Shipping local also cuts down on pollution entering the air.

Unique to growing crops in LED lighting conditions is that, with the correct combination of LED lighting colors, things like “plant height, width, color and taste,” can be controlled, added Epp. “Red light, for instance, affects height, and blue affects width.”

Because LEDs are low power devices, lighting using this technology just lasts longer, compared to, say, fluorescents, and they also give off less heat.

“‘Having lights that produce less heat and PAR (higher photosynthetic active radiation) and use less electricity are much more sustainable, better for the environment and better for our business because they’re more economical,’ he said,” Epp wrote in citing Colangelo.

Application of LED lighting in facilitating crop growth proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that the science of growing crops has indeed come a long, long way.

Image above: NASA, Kennedy Space Center

By Alan Kandel

This Indoor Farm Can Bring Fresh Produce to Food Deserts

This Indoor Farm Can Bring Fresh Produce to Food Deserts!

Almonds got the brunt of the bad press, but they hardly deserve all the blame for California’s water woes. Sure, it’s worth considering how to minimize your water footprint, and forgoing your daily handful of almonds in solidarity with the parched earth couldn’t hurt. But considering how widespread the water crisis is, and the fact that agriculture is responsible for 80 percent of the country’s water consumption, the more crucial question to be asking now—particularly on Earth Day—is what can be done to fundamentally change the way our food gets made?

Mattias Lepp says at least part of the answer involves making it easier for anyone—even city dwellers—to farm their own food. That’s why Lepp, founder of the Estonian startup Click & Grow, has developed what he calls a Smart Farm, an indoor farming system that requires 95 percent less water than traditional agriculture.

You may remember Click & Grow from their uber-successful Smart Herb Garden Kickstarter campaign a few years back. That product let people easily grow herbs in their homes with minimal maintenance. The Smart Farm is similar, but on a much larger scale. The system, which Lepp spent years developing in partnership with universities across Estonia, France, and Russia, can hold 50 to 250 plants at a time, making it a viable option for urban areas that don’t have access to fresh produce—areas the US government calls food deserts. Ideally, a shift to urban farming could drastically reduce the distance between where food is grown and where it is consumed.

The market for these indoor farms, or so-called vertical farms, is already fast-growing, driven by the growing realization that the current water-chugging agricultural system is unsustainable. On one end of the spectrum, countless DIY indoor farming enthusiasts are growing small gardens in their homes. On the other are professional outfits like Green Sense Farms out of Chicago, which grows leafy greens indoors and sells them at local stores. Even tech giants like Panasonic and Toshiba have begun developing gigantic de facto farms of their own in Asia, where there is a severe shortage of agricultural land.

And yet, the majority of these larger farms use hydroponic farming, a process that involves growing plants in mineral solutions instead of soil. They save anywhere from 70 to 80 percent of the water required for traditional agriculture, but they’re complex and can cost tens of thousands of dollars. For most of us, it wouldn’t be economically practical for you or me to grow a full-scale farm at home.

With the Smart Farm, which costs just $1,500, Lepp says it can be. “People all over the world have worked intensively the last 10 or 20 years on bringing food production closer to cities and finding ways to grow it more efficiently,” he says. “But today they all are using hydroponics, and that is unfortunately expensive and messy. We see how we can change this.”

Rather than relying on hydroponics, the Smart Farm uses a new type of soil called Smart Soil, which Lepp developed in partnership with academic advisors. The soil itself is spongey, allowing air and nutrients to flow through. Meanwhile, the nutrients are covered in a special coating that responds to soil moisture. The hardware, which looks like a glass refrigerator, consists of trays for each plant equipped with LED lights and sensors that detect when the moisture levels are off balance. The “farmer” can use an app to adjust the water levels in the system, which triggers more nutrients to be released.

This process cuts down on the amount of water required to grow the plants, Lepp says, because no wastewater is produced. At the same time, the time people have to spend actually tending to the plants is minimized.

“Click & Grow can give the plant the perfect conditions to grow, because air, water, and nutrients are dosed perfectly without any obstacles,” says Uno Mäeorg, a professor at the University of Tartu in Estonia, who worked with Lepp on the development of Smart Soil “And since those conditions are perfect for the plant, it provides us healthier plants.”

Be that as it may, the Smart Farm is still a long way from accomplishing Lepp’s eventual dream of putting a full-scale farm in every urban neighborhood. For starters, the system only supports a limited number of plants today, including strawberries, tomatoes, lettuce, and other herbs, though Lepp says that will change with time. Also, for now the Smart Farm is only available on a built-to-order basis. While the company already has orders coming in and pilot projects with universities, it won’t begin full-scale retail distribution until 2016.

Then there’s the simple fact that we’re all just plain used to buying food from a store. The dream of distributed farming may always be limited to the number of consumers who care enough to try it out.

Still, according to Dr. Dickson Despommier, a professor of public health and microbiology at Columbia University and author of the book The Vertical Farm, that number is growing steadily. And as more people become willing to give indoor farming a try, he says it’s critically important that they have tools, like the Smart Farm, to ease the effort.

“I think it could make a dent in the commercial side of things,” Despommier says of indoor farming’s potential to impact mainstream agriculture. “And if you look at what’s happening in California, there may not be a commercial side of things for much longer.”

Issie Lapowski

Kimbal Musk's New Accelerator In Brooklyn Will Train Vertical Farmers

Square Roots hopes to sprout urban farming entrepreneurs all over the country.

Kimbal Musk's New Accelerator In Brooklyn Will Train Vertical Farmers

When it opens this fall in Brooklyn, a new urban farm will grow a new crop: farmers. The Square Roots campus, co-founded by entrepreneurs Kimbal Musk and Tobias Peggs, will train new vertical farmers in a year-long accelerator program.

"Young people contact me all the time to articulate issues with the industrial food system but they are frustrated by their perceived inability to do anything about it," says Musk. "It's relatively easy to set up a tech company, join an accelerator, and progress down a pathway towards success. It's more complex to do that with food. Seeing this frustration—and pent-up energy—was a big part of the original inspiration for co-founding Square Roots."

The campus will use technology from Freight Farms, a company that repurposes used shipping containers for indoor farming, and ZipGrow, which produces indoor towers for plants. Inside a space smaller than some studio apartments—320 square feet—each module can yield the same amount of food as two acres of outdoor farmland in a year. Like other indoor farming technology, it also saves water and gives city-dwellers immediate access to local food.

New urban farmers will learn specific skills from mentors—how to grow plants hydroponically, or how to sell at farmer's markets (though hopefully it will be a little more advanced than the level of the very funny rendering Square Roots sent us, which you can see in the slideshow above)—and they'll also collaborate on new ideas. "The idea of 'the campus' came from watching magic happen at tech accelerators, like Techstars, where I've been a long time mentor," says Peggs, who will be CEO of the new accelerator. "The aim with the campus is to create an environment where entrepreneurial electricity can flow."

It's intended for early-stage entrepreneurs. "We're here to help them become future leaders in food," says Musk, who also runs a network of school gardens and a chain of restaurants that aim to source as much local food as possible.

After building out the Brooklyn campus, they plan to expand to other cities, likely starting with cities where Musk also runs his other projects—Memphis, Chicago, Denver, Los Angeles, Indianapolis, and Pittsburgh. Each location will have 10 to 100 of the shipping container farms; Brooklyn will start with 10.

"We have a lot to prove in Brooklyn but our aim to replicate the model in every community as soon as we can," says Musk.

The accelerator is looking for its first class of applicants now, and taking applications on its website.

[Photos: via Square Roots]

Take A 3D Tour Of A Vertical Farm Packed Inside A Shipping Container

These farms grow the same amount of food as a four-acre field.

In a huge warehouse just outside downtown Los Angeles, a startup turns recycled shipping containers into vertical farms. A new digital tour shows what the farms, which are each equivalent in size to a four-acre outdoor field, look like inside.

Inside one 40-foot container, trays of butter lettuce glow brightly under LED lights. Another container grows baby greens. The startup, Local Roots Farms, began as a producer, selling produce to local restaurants like Tender Greens. But when others saw how the company's custom-designed systems outperformed other shipping container farms—growing as much as five times more produce—they started getting requests to build farms as well. The empty space in the warehouse serves as a staging ground to retrofit other containers before they are shipped around the country.

"Our years of plant research helped us figure out how to grow the most per square foot while still giving plants the room they need to thrive," says Allison Towle, director of community engagement at Local Roots Farms. "In terms of sheer numbers we simply are able to grow more plants per box."

The company designed LED lights that customize red, blue, and white wavelengths at different levels depending on the type of plant and its stage of growth. "For example, arugula prefers more red light, whereas butterhead lettuce prefers more blue," says Towle. "By dialing into those colors individually we give each crop exactly what it wants. As a result, they grow more quickly and more robustly."

The 3D tour shows the details of the tiny farms, from the irrigation system to lettuce at various stages of growth. Local Roots Farms worked with Matterport, an immersive media company that 3D scans spaces and creates virtual models, to create the tour.

Have something to say about this article? You can email us and let us know. If it's interesting and thoughtful, we may publish your response.

Can Kimbal Musk Do for Farms What Elon Has Done for Cars?

“1,000s of millennials to join the real food revolution”

For more than 150 years, Pfizer manufactured pharmaceuticals in its 660,000-square-foot factory on Flushing Avenue in South Williamsburg, Brooklyn, New York. The pharma giant shut down operations in 2008, and since 2011, a host of food start-ups have taken up residence in the building’s cavernous halls. Starting next year, the bakeries and distilleries and kimchi companies will be joined by a venture called Square Roots. Founded by Kimbal Musk and Tobias Peggs, the urban farming accelerator aims to empower “1,000s of millennials to join the real food revolution,” as Musk (Elon’s brother) wrote in a Medium post announcing the venture last week.

“Our goal is to enable a whole new generation of real food entrepreneurs, ready to build thriving, responsible businesses,” Musk continued. “The opportunities in front of them will be endless.”

Square Roots’ real-food revolution will be built around container farming: shipping containers retrofitted into self-contained, highly efficient hydroponic mini farms. Beginning next fall, 10 ag-tech entrepreneurs will each develop an urban farming business in their own 350-square-foot shipping container housed in the Pfizer building. The containers will be able to produce the equivalent yield of two acres’ worth of farmland annually, with 80 percent less water than a conventional farm, according to Musk.

Brooklyn will be just the beginning: “Square Roots creates campuses of climate-controlled, indoor, hydroponic vertical farms, right in the hearts of our biggest cities,” Musk wrote on Medium. “On these campuses, we train young entrepreneurs to grow non-GMO, fresh, tasty, real food all year round, and sell locally. And we coach them to create forward-thinking companies that—like The Kitchen [Musk’s chain of eco-friendly restaurants]—strengthen communities by bringing local, real food to everyone.”

Square Roots joins the growing ranks of high-tech indoor-farming operations that are cropping up in old industrial sectors of major cities across the country—from Newark’s AeroFarms to Chicago’s FarmedHere—that are seeking to both shorten the food-supply chain and fundamentally reimagine the American farm as a high-tech, urban, factory-like operation.

If Square Roots and its contemporaries succeed, the country will be awash in locally grown lettuce, kale, and herbs. But the question is, how much locally grown lettuce, kale, and herbs do we need beyond what is already being produced? Is growing greens and herbs in shipping containers or old factories better—in terms of resources, emissions, and the environment—than growing them on farms in the Southwest? A container-farm entrepreneur can grow lettuce with less space and water than a farmer in California and Arizona, where the bulk of American lettuce is grown. But the question of sustainability isn’t answered quite so easily—and a greens revolution in agriculture can only do so much to address the problems the industry faces.

“I don’t think these big sweeping urban agriculture ideas are going to happen anytime soon,” Raychel Santo, a program coordinator at the Johns Hopkins’ Center for a Livable Future and a coauthor of a report on the potential of urban agriculture, told TakePart in May. Instead of supplanting traditional, rural agriculture, she sees urban farming’s potential in education, conservation, and as a means of fostering a connection between city residents and the food they eat—even if only on a small scale.

Start-ups like Square Roots tout the nearby nature of container farms: Produce can be grown on the outskirts of town instead of in the Arizona desert or California’s Central Valley. That’s part of the sustainability pitch: Container farming cuts down on emissions from transportation. But the great white lie of the local food movement is that the carbon emissions from trucking foods from there to here represent a small slice of agriculture’s overall climate footprint. The Environmental Protection Agency put ag at 9 percent of the nation’s overall emissions in 2014, with livestock and farmland management two of the major contributors.

With their highly efficient use of space, container gardens can do the work of a lot of farmland in exceptionally few square feet. According to Musk’s announcement, one shipping container can produce the same amount of greens or herbs as two acres of farmland—land that, if taken out of production, could be used to capture carbon rather than emitting it.

While container farms are highly efficient when it comes to space, the same cannot be said for their energy use. A 2015 study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health sought to determine whether hydroponics were “a suitable and more sustainable alternative” to conventional lettuce farming in Yuma, Arizona, which today is better known for romaine than for train robberies. While the researchers found that hydroponics outperformed traditional field-grown lettuce production in terms of land and water use, the same could not be said for energy use. Between cooling in the summer, heating in the winter, and the energy required for 24-hour lighting, hydroponic operations have high electricity demands. As the authors of the paper concluded, “Due to the high energy demands, at this time, commercial hydroponics is not a suitable alternative to conventional lettuce production in Yuma, Arizona.”

The Johns Hopkins report on urban farming, which reviewed prior research on various types of city-based ag, found similar evidence, and the authors wrote that “producing food in urban settings may increase GHG emissions and water use if plants are grown in energy- and resource-intensive operations, such as indoor/vertical farming, greenhouses, hydroponics (soilless crop production), or aquaculture (the cultivation of aquatic animals or plants for food) facilities in cold or water-scarce regions.”

Both geography and technology could mitigate the energy problem of indoor ag, as the authors noted. Renewable energy could help to offset the energy demand for heating and cooling. Building hydroponics infrastructure in a milder climate could limit the amount of cooling and heating needed throughout the year. Even if the energy issue presents a problem with indoor farming as it exists today, the researchers pointed out that the technology “provides promising concepts that could lead to more sustainable food production.”

Technology could also help to make conventional lettuce farms more efficient from a water-use standpoint. The paper noted that hydroponics are able to use less water than field-grown lettuce not because each plant needs less water when grown indoors but because highly controlled indoor farms can outperform inefficient irrigation technology. Lettuce has shallow roots “but is primarily irrigated through flood furrow irrigation in southwestern Arizona,” the authors wrote, which is also the case in California. “Water not quickly absorbed by the roots is lost to percolation. Increases in the use of low-flow and more-targeted irrigation techniques could lower the overall water use of conventional farming.”

Would a venture capitalist plow money into improving existing ag technologies? It seems unlikely during an era when the tech industry fetishizes so-called disruptive companies. Why make a better irrigation system—or invest in one—when there are more innovative ideas like shrinking down the outmoded American farm, stuffing it in a repurposed shipping container, and dropping it in an old factory in gentrified Brooklyn? CNBC does not write about irrigation companies as a “hot new area for investors,” that’s for sure.

There’s the question of what can be grown in container farms too. AeroFarms grows greens and herbs; FarmedHere grows greens and herbs. Square Roots will grow greens and herbs. Spread, a Japanese indoor-farming company that promises to go fully robotic next year, will increase its daily yield to 50,000 heads of lettuce a day, thanks to its robot workforce.

Square Roots is working with two indoor-farming start-ups, Freight Farms and ZipGrow, for the incubator farms. Freight Farms will supply the shipping containers; ZipGrow will provide the vertical-farming towers. Freight Farms calls its farm-in-a-box containers Leafy Green Machines and recommends growing lettuces, herbs, and brassicas such as kale, chard, and arugula. ZipGrow’s “recommended go-to-market crops” are greens, herbs, and flowers.

That’s a lot of lettuce, kale, and herbs. Matt Matros, the CEO of FarmedHere, which is the largest indoor farm in the country, hopes to someday grow avocados, as he told The Guardian last year, but we aren’t there yet.

The indoor-farming start-ups all offer non-GMO crops, yes—but there are also no commercially produced genetically modified greens or herbs. Any given head of lettuce grown in California or Arizona is non-GMO.

Entrepreneurs have to start somewhere. Remember when Amazon only sold books? Even if container farms can’t move past herbs and greens, if Musk and Peggs’ incubator floods the market with kale-and-lettuce-growing start-ups, those local greens will become that much more affordable.

Take the Pledge: Take Your Place: Become An Anti-Hunger Advocate

Related stories on TakePart:

• Urban Agriculture Can’t Feed Us, but That Doesn’t Mean It’s a Bad Idea

• Can Urban Agriculture Feed the World's Growing Cities?

• Urban Farming Is Now Flying a Flag at Major U.S. Airports

Original article from TakePart

See Inside This Vertical Farm Where 65,000 Pounds of Lettuce Grow Each Year in Shipping Containers

Los Angeles-based Local Roots' three farms are no ordinary farms. They're not even outside — but inside three small shipping containers.

Los Angeles-based Local Roots' three farms are no ordinary farms. They're not even outside — but inside three small shipping containers.

The startup uses vertical hydroponic farming, a method where plants grow year-round with LEDs rather than natural sunlight. Instead of soil, the seeds lie on trays with nutrient-rich water, stacked from the floor to the ceilings inside the shipping containers. The containers live inside Local Roots' warehouse in California.

Local Roots' farms save both land and water, Director of Social Enterprise Allison Towle tells Business Insider. Each 320-square-foot shipping container produces the same amount of plants as four acres of traditional farmland — using 97% less water on average.

The farms' trays also constantly track the greens' growing parameters in real-time, like temperature and levels of oxygen and CO2. The startup then uses machine learning to analyze that data and improve the growing process.

Compared to the average growth cycle of lettuce that requires harvesting, storing, and transportation, Towle says Local Roots' process use about 45% less energy than traditional farming.

But like most vertical farms, it still soaks up a significant amount of electricity to power its LEDs. Local Roots' farms consume 205 kWh of power per day, which is equivalent to nearly seven times the daily energy consumption of the average American household. It's currently exploring options that are more carbon-neutral than the traditional power grid, like solar power.

Local Roots grows 50,000 pounds of butterhead lettuce and 15,000 pounds of baby kale and spring mix per year, Towle says. For now, the greens are only available to buy at select fast-casual restaurants and markets in LA.

By Leanna Garfield

Indoor Farm Boxes Promise Little Work and Lots of Fresh Produce

In a dark apartment corner, a head of lettuce glows—and grows.

For many city-dwelling apartment renters, securing a home with a sprig of green space is a tall order, let alone a place that gets enough sunshine or rain to cultivate a fresh vegetable garden. A pair of designers have found a way to bring farms to homes—no outdoor space required.

(Photo: Courtesy Replantable)

“There’s a lot of people who have tried to start a garden to have fresh-picked food at home,” Ruwan Subasinghe, lead product designer of the start-up Replantable, wrote in an email to TakePart. “But their garden never lived longer than a single season, because the soil was poor, or the plants didn’t get enough light, or they didn’t have a green thumb, or most often because they just didn’t have the time to keep up with it.”

Enter the nanofarm, a roughly 18-by-14-inch wooden box that uses LEDs in place of the sun to nourish greens. Subasinghe has also created specially designed plant pads for the boxes. The fabric pads are woven to trap moisture and nurture the crops—including lettuce, arugula, beets, and bok choy—all without the use of pesticides.

“Instead of trying to modify the crop through genetic modification or pesticides, indoor agriculture modifies the environment that the crop grows in,” Subasinghe explained.

Subasinghe and business partner Alex Weiss have turned to Kickstarter to fund their indoor farming project. The nanofarms cost $350, along with $25 for a set of five plant pads, which contain 16–25 plants each. With more than a month to go, the two have raised more than a quarter of their $50,000 goal.

A plethora of urban- and indoor-farming projects have cropped up in recent years, but most require daily care. Subasinghe said that people would be able to forget about their nanofarms until the time came to pick the produce. “We already have too many things to keep track of in our busy lives,” he said.

The no-muss, no-fuss farm boxes simply require users to add water, turn on a timer, and wait for a notification light, which signals that the plants are ready for picking. So far, the nanofarm has been delivered to a handful of test users, all of whom report hands-off farming and plentiful harvests.

(Photo: Courtesy Replantable)

Subasinghe expects that his effort will help cut down on food waste—an environmental hazard that accounts for 8 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Antihunger advocates estimate that Americans waste about 40 percent of all food produced, most of which gets tossed out at home.

“When [consumers] buy a bag of salad greens at the grocery store, they rarely get to eat the whole thing before it gets forgotten in the fridge,” Subasinghe wrote. “The nanofarm lets people harvest minutes before eating, and only pick what they’re about to eat. The rest stays alive and growing rather than decomposing and shrinking. Our customers have shown us that they’re able to harvest every last bit of produce from the nanofarm.”

Subasinghe acknowledges that shelling out $350 for a nanofarm can be daunting for some buyers compared with a few dollars for a head of lettuce. But he hopes people will see the boxes as an investment. The nanofarm lasts for up to five years and only adds about $1 a month to utility bills. Replantable aims to have the first units out to buyers by August 2017.

Correction: Aug. 29, 2016

An earlier version of this article misstated the cost of the plants. A set of five plant pads costs $25, with each pad containing 16–25 plants.

By Gwendolyn Wu

Square Roots Launches Urban Farming Accelerator Using Freight Farms Platform

recently announced that he will be launching a new business in the fall — Square Roots. An urban farming accelerator program focused on training young entrepreneurs to grow non-GMO, fresh, tasty, food year-round, Square Roots will be leveraging the Freight Farms technology to create campuses of climate-controlled, indoor, vertical farms. These campuses will be located in major urban centers across the US starting in the fall.

Square Roots Launches Urban Farming Accelerator Using Freight Farms Platform

Kimbal Musk just recently announced that he will be launching a new business in the fall — Square Roots. An urban farming accelerator program focused on training young entrepreneurs to grow non-GMO, fresh, tasty, food year-round, Square Roots will be leveraging the Freight Farms technology to create campuses of climate-controlled, indoor, vertical farms. These campuses will be located in major urban centers across the US starting in the fall.

The Square Roots team is made up of an incredible group of individuals and network of mentors that will coach each entrepreneur in the program. Their goal is to help facilitate the creation of forward-thinking companies that strengthen communities by bringing local, #realfood to everyone. Pretty awesome, right? We think so too! The first campus is launching this fall in Brooklyn, and they’re looking for their first class of real food entrepreneurs. If you want a chance to work in an LGM and receive guidance from industry experts, be sure to apply.

We’ve always said that our network of farmers brings to life the vision of our company, and this is yet another perfect example. Sure, we build the farms and the software, but ultimately it’s what each farmer does with those farms that makes the true impact. Square Roots is harnessing the Freight Farms platform to bring a larger vision to life, and we’re beyond excited to watch this partnership grow.

If you’d like to hear more about how Freight Farms is helping grow local food ecosystems across the globe, give us a shout!

What the Heck Is… Vertical Farming?

Radical solutions are needed to keep up with our fast-growing world population.

Our weekly series What The Heck Is… sheds light on the strange unexplained acronyms and unfamiliar buzzwords that creep into our everyday lives.

Farming, something humans have been doing for thousands of years, is struggling to adapt to our modern world. Radical solutions are needed to keep up with our fast-growing world population.

What’s wrong with regular farming?

Firstly it’s expensive, both in financial cost and the cost of land required to grow food at scale.

It’s environmentally unfriendly, not just with chemicals and pesticides being poured into the ground, but also the fact that farms only generate a few harvests a year. During winter most of the world’s farmland is simply being wasted.

Plus farming is creating food in the places that we don’t really need it.

More than 50% of the world’s population lives in cities, and this will rise to 80% by 2050, but all the food is being created in rural areas because of the land required to grow at scale.

The result is that transport costs, the environmental impact of transporting this food, and the fact that 30% of all farmed food is wasted because it spoils before it can be eaten, make traditional farming a costly exercise.

So is there a better way?

What the heck is vertical farming?

As its name suggests, vertical farming is a new way of growing of food can be stacked vertically, rather than horizontally, and uses technology to solve the problems with traditional farming.

Think trays of crops stacked in warehouses, with their water, pesticides and even sunlight controlled by a computer, giving them exactly what they need to grow and dramatically boosting the quantity of food produced.

The theory suggests that these vertical farms could even be built inside skyscrapers or existing buildings, creating food where it is needed and reducing the environmental impact of farming.

We say theory, because at the moment that’s exactly what vertical farming is.

AeroFarm hasn't started vertically farming on an industrial scale, yet.

Putting theory into practice

Today there are several vertical farms in the early stages of construction.

In the US, Vertical Harvest based in Jackson, Wyoming, is up-and-running planning to vertically grow 100,000 pounds of vegetables every year.

If they achieve that goal it will offset 3% of the produce currently being shipped into the town.

But it’s early days and they have yet to prove that they can vertical farm this amount of food at such a scale.

AeroFarms in Newark, New Jersey, has even grander goals. The company plans to harvest 2m pounds of veg a year from their 69,000 sq ft warehouse, using 95% less water and 50% less fertiliser than a traditional farm… once production starts in September 2016.

The projects share two things in common:

Neither has proved that they can yet produce the quantity of food they promise, at an acceptable price and with a sustainable business model.

And both are supported by millions of dollars in venture capital investments and government subsidies.

What does it mean for your food shop?

If vertical farming works, the price you pay for food could fall – as transport costs disappear and farming becomes less wasteful – as we enter a new era of locally-sourced food.

Or, the price of your food could skyrocket – if the cost of the technology is passed onto shoppers, or if the efficiencies of vertical farming are never realised.

With millions being spent on vertical farming and dozens of vertical farms coming online over the next few months and years, it won’t be long until we discover if the food of the future will be grown in a warehouse.

Our weekly series What The Heck Is… exists to shed light on the strange unexplained acronyms and unfamiliar buzzwords that creep into our everyday lives.

By Oliver Smith

Old Steel Mill Will Soon Be World's Largest Vertical Farm

Stacks of leafy greens are sprouting inside an old brewery in New Jersey.

NEWARK, N.J. (AP) — Stacks of leafy greens are sprouting inside an old brewery in New Jersey.

On this Thursday, March 24, 2016, file photograph, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, center at podium, addresses a gathering at AeroFarms, a vertical farming operation in Newark, N.J. AeroFarms is now refurbishing an old steel mill in New Jersey and they say it will soon be the site of the world's largest indoor vertical farm. The company says their Newark facility, set to open in September, could produce 2 million pounds of food per year and help with farming land loss and long-term food shortages. (AP Photo/Mel Evans, File)

"What we do is we trick it," said David Rosenberg, co-founder and chief executive officer of AeroFarms. "We get it thinking that, if plants could think: 'All right, this is a good environment, it's time to grow now.'"

AeroFarms is one of several companies creating new ways to grow indoors year-round to solve problems like the drought out West, frost in the South or other unfavorable conditions affecting farmers. The company is in the process of building what an industry group says is the world's largest commercial vertical farm at the site of an old steel mill in New Jersey's largest city.

It will contain 12 layers of growth on 3½ acres, producing 2 million pounds of food per year. Production is set to begin next month.

"We want to help alleviate food deserts, which is a real problem in the United States and around the world," Rosenberg said. "So here, there are areas of Newark that are underprivileged, there is not enough economic development, aren't enough supermarkets. We put this farm in one of those areas."

The farm will be open to community members who want to buy the produce. It also plans to sell the food at local grocery stores.

Critics say the artificial lighting in vertical farms takes up a significant amount of energy that in turn creates carbon emissions.

"If we did decide we were going to grow all of our nation's vegetable crop in the vertical farming systems, the amount of space required, by my calculation, would be tens of thousands of Empire State Buildings," said Stan Cox, the research coordinator at The Land Institute, a nonprofit group that advocates sustainable agriculture.

"Instead of using free sunlight as we've always done to produce food, vertical farms are using light that has to be generated by a power plant somewhere, by electricity from a power plant somewhere, which is an unnecessary use of fuel and generation of carbon emissions."

Cox says that instead of moving food production into cities, the country's 350 million acres of farmland need to be made more sustainable.

But some growers feel agriculture must change to meet the future.

"We are at a major crisis here for our global food system," said Marc Oshima, a co-founder and chief marketing officer for AeroFarms. "We have an increasing population that by the year 2050 we need to feed 9 billion people. We have increasing urbanization."

Rosenberg also pointed out the speeded-up process.

"We grow a plant in about 16 days, what otherwise takes 30 days in the field," he said.

By TED SHAFFREY

Aug. 19, 2016 1:30 AM EDT

How to Apply for the USDA Microloan as an Upstart Farmer

So you’ve decided to start a farm.

by Amy Storey | Aug 18, 2016 | Farm & Business Planning

Freaked out about funding?

So you’ve decided to start a farm. You’re buzzing with excitement and anxiety about getting started, and maybe you’ve hit a few hitches in the planning process. You’re worried about getting the funding you need, and the world of financing can be overwhelming.

If this is you, then don’t worry! From grants and crowdfunding, to bootstrapping and loans, you have multiple options to fund your farm. One of those options is the USDA Microloan, a loan built specifically for unique startup farmers like yourself.

In this post, we’re going to explore how to apply for the USDA Microloan as an Upstart Farmer, including:

- why the microloan is a good option for small startup farmers

- what the process looks like

- tips on applying from a recent recipient

The benefits of the USDA Microloan

Farmers looking for money to jumpstart their farm (or farm expansion) should seriously consider the USDA’s microloan program. The microloan is built for alternative farmers growing niche crops or serving niche markets, including “those using hydroponic, aquaponic, organic and vertical growing methods.”

In face, I’ve spoken with two Upstart Farmers who have recently received the microloan – Carey Martin (who spoke about it in the “Funding Your Farm” course), and Chris Elliot.

The microloan was a great fit for Chris Elliott of Water Sprout Farm, an Upstart Farmer who runs a new indoor hydroponic farm.

We’ve noted before that starting a farm is becoming a more accessible goal to anyone with a few thousand dollars (the microloan provides up to 50K) and work ethic. These funding opportunities just add to that trend.

This is perfect for the Upstart Farmers, most of whom start small with specialty crops and/or specialty markets. Often, they are completely inexperienced in the field, but ready to sweep their communities off their feet with high quality local produce.

The USDA Microloan that Chris received is especially geared towards new and “underserved” farmers; in fact, over 70% of the loans provided have been given to just-starting farmers. This year, the FSA (Farm Service Agency, a part of the USDA) expanded the loan from operating costs to include building costs.

On top of that, the microloan typically has low interest rates. Chris’ loan run interest at 2.25%. “You can’t get that at a bank.”

The process: how to apply for the USDA Microloan

Of course, some loan applications can be tedious and overwhelming. Not so with the USDA Microloan. Chris says that because he already had his financial planning done before filling out the application (you should do this prior to seeking funding, by the way), filling the application only took an hour.

The office was able to answer all questions about completing the application process.

“They were good about answering questions, so don’t be afraid to ask,” advises Chris. “Unlike a bank that’s trying to determine whether or not they can make money off you, they’re really just trying to help farmers out.”

Many entrepreneur-focused institutions will have the same helpful attitude. “We found a bank out of Pittsburgh that does startup loans and they have a lot of ancillary benefits that really are helping out. I would imagine there are similar banks around the country. You pay more in interest but they actually will work with you [unlike some] traditional banks.”

After that, the application should only take a few weeks to process. (Factor in time for mailing, since many loan offices won’t take faxed forms.) the loan office will be able to give you more specific timelines depending on their staffing.

Challenges and tips for applying for the USDA Microloan

Although the loan application and process are streamlined for beginning farmers like you, there are several things that you can do to avoid hiccups and keep things moving. Chris had several insights for small Upstart Farmers.

1) Work to get loan managers the info they need.

Since loan managers aren’t usually familiar with vertical indoor growing, their questions might not be easy to answer, and the application might not be designed with questions suited to your farm. For instance, there might not be enough space to give a complete answer. Units might not be applicable (e.g.: “How many acres are you farming?”). The loan managers will want to know assets and debt – although you might not have any.

Chris says that this can be both good and bad.

“At a high level, we are a different breed than what the farm loan managers have ever experienced. They truly didn’t know what to do with me… This is a good and bad thing. They didn’t know enough to ask really tough questions, but they also didn’t know enough to figure out some easy ones on their own either.”

What to do: For assets and debt, ask if you can fill it out as though you had been in operation for a year. If they ask about the assets of the spouse who is not tied to the farm or the loan, just explain the situation and work with them to come up with a solution. The important thing here is that they have the information they need to make a good decision. So get it to them! Maybe there isn’t enough space for a financial plan. Summarize yours and send them the complete document on your own.

2) Turn everything in at once.

Make sure that you have gathered all of the documents and forms that you need, and turn it in at the same time. If you’re missing pieces, your application will be marked incomplete and after certain amount of time the application will be discontinued.

3) Know your numbers.

Depending on the farm manager, confidence in your financial and production planning can really sell them on your farm. This is when the pricing and planning information that you’ve worked on with Bright Agrotech is very convenient. If you’re planning a farm using ZipGrow, then you’re probably working on a Financial Plan and Analysis with one of our farm guides. (Not doing this yet? Here’s how to get started!)

Carey Martin noted that having someone look critically through your financial plan can be a huge asset, as they will spot holes and help you patch up rough spots.

4) Use Bright Agrotech and Upstart University as the required mentor and training certification.

“They wanted to make sure that you have some kind educational experience in farming, and be training or have a mentor. That was a hurdle I had to get through. I was actually able to use [Bright Agrotech] as a mentor and taking Upstart University; collecting those certificates worked as a legitimate training.”

5) Match your lease to your loan (and have an escape clause)

“One of the other hurdles that I came across was the length of the loan had to match the length of our lease of the warehouse. So we had to change our lease to a 7 year lease to match the 7 year loan. If that is the case across the board, farmers have to really try and negotiate a good escape clause in their lease in case things don’t work out.”

6) Be prepared for difficulty with additional liens

“One other issue was that USDA required to have the first lien on our equipment, so any additional lenders would have to take a 2nd lien, and a lot of the traditional banks did not want to do that. We had a hard time finding additional financing due to this. They won’t share the lien either, it has to be the first and only first.”

Is the USDA Microloan for you?

The microloan has served multiple starting farmers, and might be the best option for you.

If you want to look at some other funding options like grants and crowdfunding, go through the Funding Your Farm course on Upstart University.

And if the USDA Microloan is for you, you can get links to forms, instructions, and FAQ’s here.

Remember, financial planning should happen before funding!

Want information on starting a commercial farm? It can be tough to find. That’s why we’re walking aspiring farmers through the planning process in our Feasibility Workshop. In the online workshop, we’ll go through the process of creating your own in-depth feasibility study to help you make the business case for your future farm.

Indoor Farms Give Vacant Detroit Buildings New Life

Surplus of vacant buildings a boon for indoor farmers

Indoor Farms Give Vacant Detroit Buildings New Life

Breana Noble , The Detroit News 11:17 a.m. EDT August 16, 2016

Surplus of vacant buildings a boon for indoor farmers

Standing before a shelf of red incised lettuce, Artesian Farms Managing Partner Jeff Adams talks about the indoor vertical farming operation used to produce three types of lettuce and kale at the company in Detroit on Aug. 3, 2016. Brandy Baker, The Detroit New

Entrepreneurs are taking advantage of inexpensive former warehouses and factories in Detroit and transforming them for agricultural use to produce local foods.

There’s a growing movement of using vacant buildings and spaces to produce lettuce, basil and kale, and even experiment with fish farming — year-round.

And the city is considering regulations that could expand indoor agriculture even more.

“Fifteen, 20 years from now, we want people to say, ‘Of course they grow kale in that building,’ ” said Ron Reynolds, co-founder of Green Collar Foods Ltd. It built its first indoor-farming research hub in Eastern Market’s Shed 5 in 2015.

Green Collar Foods mists the bare roots of kale, cilantro and peppers using an aeroponics system under fluorescent lights in its 400-square-foot plastic-encased greenhouse. The system is built vertically, stacking plants on shelves to grow above each other. Supino Pizzeria in the Eastern Market buys its kale.

It’s one piece of Detroit’s growing urban agriculture scene. Although the city lost about a quarter of its population between 2000 and 2010, community gardens flourished from fewer than 100 in 2004 to around 1,400 today, according to Keep Growing Detroit.

In response, Detroit adopted a zoning ordinance in 2013 to legalize urban farming that was popping up all over the city. The urban agriculture ordinance, however, assumes indoor farming would be large-scale, said city planner Kathryn Underwood. To increase the zoning district, the City Planning Commission sent an amendment to the City Council for consideration that would take into account smaller operations. It is expected to vote on the proposal in the fall.

“(The amendment) recognizes (indoor farming) can happen at very large scales and very small scales,” Underwood said. “It will allow more of it to happen.”

There’s space for it. In 2014, Detroit had more than 78,000 vacant buildings, according to a blight task force survey.

That’s what Green Collar Foods found attractive about Detroit, co-founder Frank Gublo said. Several Detroit and Flint entrepreneurs are interested in working with Green Collar to create farms in 7,000-square-feet indoor spaces.

Green Collar’s Reynolds envisions franchised operations in unused buildings. “It creates a business in an area that is struggling to find businesses to locate in,” he said.

Less water, longer shelf life

Since 2013, at least three other indoor farms have opened in Detroit.

Jeff Adams started planting in 2015 at his Artesian Farms located inside a 7,500-square-foot former vacant warehouse in the Brightmoor district. He uses stacked growing beds and hydroponics to grow lettuce, kale and basil. The hydroponic system replaces soil with nutrient-filled water.

Adams said the kale sells competitively for around $4 for 5 ounces at retailers in Metro Detroit, including Busch’s and Whole Foods Market.

He said his farm has advantages over traditional growers. California farms use seven gallons of water to grow a bundle of lettuce, while his system uses three-tenths of a gallon. Growing locally also extends shelf life.

Artesian Farms, located in a 7,500-square-foot former warehouse in the Brightmoor district, uses stacked growing beds and hydroponics to grow lettuce, kale and basil. (Photo: Brandy Baker / The Detroit News)

“The food you’re eating right now, it’s seven to 10 days before it reaches Michigan,” Adams said. “(Artesian Farms’ produce) is from here to the market in a day, at most, 48 hours. ... It’s going to be much more flavorful and much more nutritional.”

Although the lights feeding his plants suck electricity, Adams is replacing them with purple LEDs, which use 40 percent less power.

That’s important for the future: Adams has five plant racks — one recently produced 95 pounds of lettuce in 36 square feet. By September, he expects to have 11 racks; by November, 26 racks; and in one year, 46 racks of lettuce, kale, spinach, arugula and bok choy. He plans to add five people to his team of two, including himself, by the end of the year — and another three when all stations are installed.

“The whole purpose of this was to employ people, and you can’t employ people if you’re going to be doing it four months out of the year,” Adams said. “If you want to farm all year-round, this is the way to do it.”

Start-up already plans to expand

Eden Urban Farms harvested its first batch of hydroponic lettuce earlier this year.

After researching indoor farmers in the Netherlands, CEO Kimberly Buffington started a pilot farm with four trays of plants, one producing 170 bundles of lettuce. Eden has grown herbs, lettuce, peppers and strawberries.

The company, which now resides in the basement of a business partner’s Milford home, will expand in the next two years to a 31,000-square-foot rental space at 1800 18th St. on the border of Corktown and Mexicantown. Eden has two employees and plans to hire five or six by year’s end. Once in full operation, Buffington expects to employ about 70. Her team is also developing a small-scale system for entrepreneurs.

Eden Urban Farms sells produce at markets and restaurants. Its basil goes at market price between $1.99 and $2.29 for three-quarter ounces, Buffington said. Herbs and peppers are the most profitable.

“We know that the model works,” she said. “If we want to be in business, we have to be competitive.”

Employing people was the goal