Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Dining Hall Officials Serve University-Grown Lettuce

Posted: Wednesday, October 19, 2016 5:25 pm | Updated: 9:02 pm, Wed Oct 19, 2016.

Ethan Owen | 0 comments

Five hundred heads of lettuce per week are being grown on campus by Chartwells to be served in the dining halls.

The lettuce is grown in a Freight Farm container, a product of the Boston-based company Freight Farms, is located near the Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences building and the Northwest Quad.

The model of the farm on campus is known as the Leafy Green Machine and can grow lettuce, herbs, and other leafy items such as chard and kale, according to the Freight Farms website.

The size of the container is 40 feet long, 8 feet wide and 9.5 feet tall. It also houses a vertical hydroponic growing system, meaning the produce is grown without soil and is climate controlled, according to the Freight Farms website.

Ashley Meek, the campus dietician for Chartwells, and Merrisa Jennings, a Chartwells student intern, helped orchestrate the project to bring Freight Farms to the UofA.

The project began in May and is a part of Chartwells’ efforts to be more transparent in where the food that is served comes from, Meek said.

The farm will typically provide 500 heads of lettuce per week that are grown without the use of pesticides, Meek said.

Unlike the experimental garden on the Arkansas Union rooftop in the spring, the farm’s climate-controlled environment protects the plants from wind damage, pests and the heat of the sun, Meek said.

A lack of pests eating away at the produce creates beautiful heads of lettuce, Jennings said.

Jennings, a senior biological engineering major, was brought on as an intern to help address the sustainability side of the project and said that the farm helps campus look more sustainable.

The farm uses 10 gallons of water and 80 kilowatt-hours of electricity per day, according to the Freight Farm website.

They want to see more student involvement with the Freight Farm and that it provides opportunities for business, marketing and communications students, Meek said.

Chartwells would like to get another Freight Farm, Meek said.

The container cost $97,000 and will be paid off in about 4.5 to five years, Meek said.

The 2016 premium Leafy Green Machine costs $85,000 plus an estimated $13,000 per year operating cost, according to the Freight Farm website.

Reception to the farm and its product has been positive amongst students and faculty, Meek said.

Meek said that she gets asked for tours of the farm at least five times a week, but because the farm is a controlled environment, those who ask for tours are turned away for food safety reasons.

Brandon Conrad, a freshman who eats at Brough dining hall, said that he was not aware that lettuce served was grown on campus.

“I think it’s pretty cool,” Conrad said. “I thought it was grown somewhere else.”

In Coal Country, Farmers Get Creative To Bridge The Fresh Produce Gap

Joel McKinney stands beside a hydroponic tower that is part of his farm outside the Five Loaves and Two Fishes Food Bank

In Coal Country, Farmers Get Creative To Bridge The Fresh Produce Ga

Roxy Todd/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

In coal country, thousands of miners have lost jobs. While there aren't any easy solutions, in West Virginia, two farmers are doing what they can to keep wealth in their community and provide healthy food to more people.

In the parking lot of the Five Loaves and Two Fishes Food Bank in McDowell County, squash and basil are growing in 18 tall white towers without any dirt. It's a farming method called hydroponics. The vegetables sprout from tiny holes as water and nutrients flood the roots.

Joel McKinney built this hydroponic garden because it produces a lot of food yet takes up just a little space.

"So like for right here I can grow 44 plants, whereas somebody growing in the ground can only grow four," McKinney says. "So I want to do as much vertical space as I can and really amaze people with the poundage of food, because I'm growing up instead of out."

McKinney sells lettuce to the local high school and makes about $800 every three weeks.

He also gives away some of his produce to the food pantry, which is run by his parents. And along with a handful of other farmers, he has started a farmers market outside the food pantry. The goal is to raise the profile of local farming in the community and help small farmers make extra income.

When the market starts back up in the spring, it will accept benefits from SNAP — the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, also known as food stamps — to help encourage purchases from low-income residents.

"People have the ability to grow their own food. I want to help them learn to market their product and earn some money," he says. "Like people who quilt or make necklaces, the same thing with growing food — people have just never seen it as a marketable skill."

With so many coal miners out of work now, the number in need of food has soared.

McKinney's mother, Linda, who runs Five Loaves and Two Fishes, sometimes brings food directly to people's homes — especially if she hears there are children going hungry.

"And when you take them food, you will find out it's not just food that they need," Linda McKinney says. "There are a lot of individuals that are so desperate. These individuals are just surviving."

Farmer Sky Edwards has tried to start a farmers market in McDowell County, W.Va., but so far it hasn't been successful. So he travels 60 miles round trip each week to sell vegetables in Bluefield, W.Va., where residents have more cash to spend on groceries.

In this West Virginia county, many have given up trying to find a job. And the unemployment rate is almost three times the national average.

This is a major problem, says John Deskins of West Virginia University's Bureau of Business and Economic Research. He says McDowell County has had an economic collapse comparable to the Great Depression.

"We're talking about tremendous, tremendous losses in a relatively short time frame," he says. "We've seen major declines in coal production, major declines in coal employment. But then that spills over into the rest of the economy, right? These coal mining jobs are good, high-paying jobs."

Families have to make choices: Do they pay rent or buy fresh food?

Bradley Wilson teaches geography at West Virginia University, and he says at least a quarter of people in the state struggle to afford groceries.

"In places like McDowell, that's compounded by a lack of access to the very kind of food environment necessary to live that healthy lifestyle as stores like Walmart disappear, or businesses close up shop because the population is declining," Wilson says.

Walmart closed its supercenter in McDowell County this past January. Many residents now have to travel over an hour to buy groceries. Not all of them own a car.

"And even when they go grocery shopping at the beginning of the month, they have to pay somebody to take them," says farmer Sky Edwards.

He has tried to start a farmers market in McDowell, but so far it hasn't been successful. So he travels 60 miles round trip each week to sell vegetables in Bluefield, W.Va., where residents have more cash to spend on groceries.

Kristin McCartney is a registered dietician who works with the Family Nutrition Program out of West Virginia University. She says poor access to grocery stores is one reason so many West Virginians eat unhealthy diets. But it's not the only challenge in encouraging better eating habits.

"There's still a struggle in West Virginia to get people to eat vegetables. We're one of the lowest states [in terms of] vegetable consumption," says McCartney.

That's why, at the market in Bluefield, Edwards often shares cooking tips with customers. Late this summer, I watched as he explained a recipe for roasted squash to a customer.

Edwards has also bought a truck to start a mobile farmers market in rural McDowell. He wants to make it easier for people in his community who don't have cars to access fresh produce. He's also planning to accept food stamps at his truck when it gets up and running.

"You have to make it easy for people to eat better," he says.

How Two IIT Scientists Are Using Food Waste To Revolutionize Indoor Farming

Two scientists at Illinois Institute of Technology may have solved one of the biggest inefficiencies in aquaponic farming -- the abundant use of energy that it requires...

10/18/16 @10:28am in Tech

Two scientists at Illinois Institute of Technology may have solved one of the biggest inefficiencies in aquaponic farming -- the abundant use of energy that it requires.

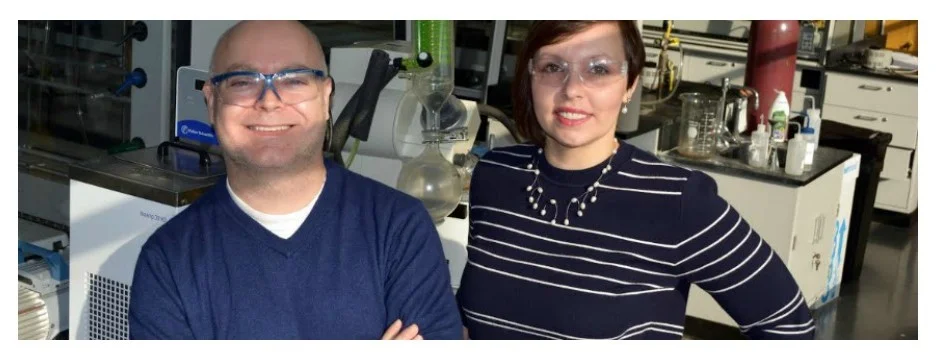

Elena Timofeeva, a research professor in chemistry, and John Katsoudas, a senior research associate in physics, have developed a system that uses organic food waste -- rather than electricity -- to generate a mobile, containerized aquaponics farm that will bring locally produced food to food-poor areas while also cutting down on the pollution that contributes to global warming. The team was recently selected as a semi-finalist in the 2016 Cleantech Open Accelerator Program, which identifies promising early-stage clean technology companies and provides them with six months of educational and mentoring support. Now, they're working with Cleantech adviser on market research, business strategy and fundraising, and they plan to have the full-scale prototype finished in the next 18 months.

The two explained that in a traditional aquaponics farm, the fish in the tank produce waste that is converted into a natural fertilizer for the plants. In turn, the plants keep the water clean for the fish. It's a system that requires about 80 percent less water than traditional farming, Katsoudas said.

However, it's not a perfect system. There are at least two popular methods of aquaponics farming -- completely enclosed units where artificial light is brought in to do year-round growing or operating one within a greenhouse. In both cases, energy is consumed for the electricity, heating or cooling of the enclosed environment.

"[Aquaponic farming] has really started to take off now in the modern age because of the stresses being put on the environment. From increased farming to increased population density, it’s been identified [that] the production model for food needs to change," Katsoudas said. "The problems with aquaponics ... is that they consume a lot of energy. What AquaGrow Technology does is [identify] a way to bring in bio-digestion."

Biodigestion is where food waste, which comes from outside sources like cafeterias, food processing plants, food banks or anywhere else organic waste is generated and destined for landfills, comes into play, Katsoudas said.

"[Food waste] is introduced into the biodigester through an external chute and then over the period of about 21 days it's converted into methane," he later explained in an email to Chicago Inno. "We then pipe that methane into an electric generator and produce electricity and CO2. The electricity is what we use to power the aquaponics systems, i.e. the grow lights, heaters, pumps, air conditioners, control systems, life support for the fish, etc. The byproduct of generating electricity using methane is CO2."

Simply put, the aquaponics farm that Timofeeva and Katsoundas have developed replaces electricity with organic food waste as the energy source for the lights and other technologies that support the system.

The other key difference to their system is the size, according to Timofeeva. The container will come to a total size of 10 feet wide, 10 feet deep and 45 feet tall.

"[The size] also enables smaller players -- like individual families, individual churches, individual communities -- to get into this farming locally," she said. "If it’s a huge farm, you need a large investment to get involved in this. Having a containerized farm that can be located in small plots of land would enable local farming and engaging pops in farming as well."

They estimated that the cost of such a unit would come to about $150k, and it would produce an annual profit of $40-$80k, depending on the plant or crop harvested.

"The investment [an individual family] would make would pay back in 2-3 years," Timofeeva said. "They can locally produce food and make money off of it ... It works really well economically … by minimizing operational expenses on site."

Katsoudas also said that the mobility of these containers would prove especially useful in communities after national disasters where there is no access to food, or in underserved urban communities

"We have to believe that when there’s a good investment made, there will be resources available to make it," he said. "When you look at the nature of the grants coming out, there is a whole new movement of grant money that's coming to bear for social impact."

He explained that there is a direct correlation between the level of crime in an urban area, and the amount of nutritional food in that area.

"You look at the dollars that society spends on police forces and incarceration ... If you were able to bring the crime down but supplying a nutritional value, an asset to the local community, those are dollars better spent.," he said, explaining that after obtaining grants, ministries, congregations and social organizations would likely be the first adopters of their aquaponics farm.

"I think that’s a good investment," he said. "I do believe there are organizations and people that will see that."

Target to Add Vertical Farming to Some Locations

“Food is a big part of our current portfolio today at Target—it does $20 billion of business for us”

MINNEAPOLIS, MN – Target is about to shake up the retail realm with its latest plan to put a focus on fresh produce and tap on in consumer penchant for fruits and vegetables. Target will be installing vertical farms in some of its locations.

“Food is a big part of our current portfolio today at Target—it does $20 billion of business for us,” continued Casey Carl, Target’s Chief Strategy and Innovation Officer to Business Insider. “We need to be able to see more effectively around corners in terms of where is the overall food and agriculture industries going domestically and globally.”

Target’s new focus on fresh will reportedly help the retailer gauge just how consumers want their produce, and how engaged they want to be with their food. Target’s Food + Future CoLab allows the company to do just that; shape the future of food, and deliver on the needs of consumers.

The Food + Future CoLab team announced at the White House that food grown from its in-store garden would be on sale starting in the spring, according to Business Insider. The initial in-store trials could also potentially see consumers picking their own produce from the Target farms.

“Down the road, it’s something where potentially part of our food supply that we have on our shelves is stuff that we’ve grown ourselves,” continued Carl.

The Food + Future CoLab was launched by the retailer in January in collaboration with Idea and the MIT Media Lab. This new research partnership is also allowing Target to pursue even further innovations, like taking vertical farming to new metaphorical heights.

“Because it's MIT, they have access to some of these seed banks around the world,” Greg Shewmaker, Entrepeneur-In-Residence, Food + Future CoLab, stated. “So we're playing with ancient varietals of different things, like tomatoes that haven’t been grown in over a century, different kinds of peppers, things like that, just to see if it's possible.”

The Target farms will use artificial lights and hydroponics to grow its produce. Daily Meal elaborated that while Target’s vertical farms will initially focus on leafy greens, the retailer is exploring growing potatos, beetroot, and zucchini for its next varieties.

As Target and its Food + Future CoLab move towards this new retail strategy, AndNowUKnow will continue to update you in the latest developments and its impact on the buy-side sector.

The Potential of Urban Agriculture Innovations in the City, from Hydroponics to Aquaponics

How large a role will local food demand play with respect to the growth of indoor and controlled environment urban farming ventures?

The Potential of Urban Agriculture Innovations in the City, from Hydroponics to Aquaponics

October 18, 2016/in aquaponics, Local Food, Sustainable Agriculture Conference, Urban Agriculture /by Robert Puro

How large a role will local food demand play with respect to the growth of indoor and controlled environment urban farming ventures? What are the costs involved in starting a small scale commercial hydroponic/aquaponics farm? What are the opportunities (community and economic) for high-tech controlled environment growing in urban environments such as Orange County? What tools or assets would give an entrepreneur the best chance for success in launching a vertical farming venture in the city?

To learn the answer to these questions, and more, you won’t want to miss the ‘The Potential of Controlled Environment Agriculture in the City’ panel at the upcoming Grow Local OC: Future of Local Food Systems slated for Nov. 10 at California State University, Fullerton. The following expert speakers will address the challenges and opportunities present in employing innovative agricultural growing systems in cities:

Erik Cutter is Managing Director of Alegría Fresh, an urban farming company engaged in promoting and deploying zero waste regenerative food and energy solutions using hybrid soils and integrated technologies. In 2009, Mr. Cutter founded EnviroIngenuity with a group of forward-thinking professionals to take advantage of the growing demand for more efficient, cost effective sustainable energy solutions, employing solar PV, hi-efficiency LED lighting, green building and zero waste food production systems. More than 35 years of travel throughout the US, Mexico, South America, Africa, French Polynesia, the Peruvian Amazon, Australia and New Zealand gave Mr. Cutter expert insight into the unique investment opportunities that exist in each region, focusing on sustainable living models and the increasing availability of super foods as a major new market opportunity.

Chris Higgins is General Manager of Hort Americas, LLC (HortAmericas.com) a wholesale supply company focused on all aspects of the horticultural industries. He is also owner ofUrbanAgNews.com (eMagazine) and a founding partner of the Foundation for the Development of Controlled Environment Agriculture. With over 15 years of experience, Chris is dedicated to the commercial horticulture industry and is inspired by the current opportunities for continued innovation in the field of controlled environment agriculture. Chris is a leader in providing technical assistance to businesses, including commercial greenhouse operations, state-of-the-art hydroponic vegetable facilities, vertical farms, and tissue culture laboratories. In his role as General Manager at Hort Americas he works with seed companies, manufacturers, growers and universities regarding the development of projects, new products and ultimately the creation of brands. Chris’ role includes everything from sales and marketing to technical support and general management/owner responsibilities.

Ed Horton is the President and CEO of Urban Produce. Ed brings over 25 years of experience from the technology industry to Urban Produce. His vision of automation is what drives Urban Produce to become more efficient. With God and his family by his side he is excited to move Urban Produce forward to provide urban cities nationwide with fresh locally grown produce 365 days a year. Ed enjoys golfing and walking the harbor with his wife on the weekends.

Chef Adam Navidi – In a county named for its former abundance of orange groves, chef and farmer Adam Navidi is on the forefront of redefining local food and agriculture through his restaurant, farm, and catering business. Navidi is executive chef of Oceans & Earth restaurant in Yorba Linda, runs Chef Adam Navidi Catering and operates Future Foods Farms in Brea, an organic aquaponic farm that comprises 25 acres and several greenhouses. Navidi’s journey toward aquaponics began when he was at the pinnacle of his catering business, serving multi-course meals to discerning diners in Orange County. Their high standards for food matched his own. “My clients wanted the best produce they could get,” he says. “They didn’t want lettuce that came in a box.” So after experimenting with growing lettuce in his backyard, he ventured into hydroponics. Later, he learned of aquaponics. Now, aquaponics is one of the primary ways Navidi grows food. As part of this system he raises Tilapia, which is served at his restaurant and by his catering enterprise.

Nate Storey is the CEO at Bright Agrotech, a company that seeks to create access to real food for all people through small farmer empowerment. By focusing on equipping and educating local growers with vertical farming technology and high quality online education, Nate and the Bright Agrotech team are helping to build a distributed, transparent food economy. He completed his PhD at the University of Wyoming in Agronomy, and lives in Laramie with his wife and children.

Register here: http://growlocaloc.eventbrite.com

New York City Feeds Itself Tonight!

It’s a time where futurists growing hyperlocal food and technologies in New York City open their labs for urban food week

New York City Feeds Itself Tonight!

10/15/2015 04:45 pm ET | Updated Oct 15, 201

Karin Kloosterman flux founder

It’s the middle of NYC AgTech Week.

. Tonight there will be a fish taco dinner prepared with fish raised on a roof in the city; the rest of the food was grown in urban farms in locations throughout the Big Apple. Dining starts tonight at Farm on Kent, pictured below, in Brooklyn.

A host of tours from 12 noon to 4 tomorrow Friday will show of off the city’s coolest urban farming technologies and I’ll be there giving a demo on how my hydroponics technology flux works.

Leading a global trend to grow hyper-local food close to home, New York entrepreneurs have innovated their food well beyond tomorrow using bold applications from the world of high-tech.

Tonight Manhattan Agriculture chefs will do the chopping and cooking and at the event meet 21 of New York’s leading urban agtech companies planting roots for a vision that New York will produce up to 40% of its food locally.

Sample pesticide-free food or see how food is grown on “water” or hydroponically — one of the most sustainable ways to grow fresh, tasty food in cities.

The event is hosted by the New York City Agriculture Collective (www.farming.nyc).

Henry Gordon-Smith, from Blue Planet Consulting, one of the city’s leading consultants on urban farm projects using technologies like hydroponics says: “I am getting calls on a daily basis from Real Estate developers wanting to know how they can make use of rooftops to grow both food and a new source of income.

“On the flipside I am seeing nothing short of a revolution driven by young entrepreneurs across the globe. Farming in the city has become the next big career: Post-degree, college students from various disciplines are asking me how they can switch careers and they are moving to NYC to make it happen. They want to quit everything and start growing food in their cities. This week will give answers to everyone who is curious about the industry,” he says.

The crunchiest carrots, the coolest connected cucumbers

And just like each New York neighborhood has its own flavor, the same is true for urban farms in the city. Urban farming can mean growing fish for families on a roof in Brooklyn, using hydroponic greenhouses in the Bronx to grow greens in the winter, or using connected sensors and software to optimize yield in the smallest of space — even if you live in a small rental in Soho.

It’s no surprise that when a movement to “grow local” sweeps across the nation that New York City picks it up and takes a firm stance and a bold leaf, ahem, lead in urban farming.

Meet the breadth of New York City’s agriculture leaders in industry and products for the connected garden at New York’s first AgTech Week where investors will connect to educators, backyard farmers, large-scale commercial growers, community activists, and city officials.

The full program is found here. Or email hello@farming.nyc for more.

Follow Karin Kloosterman on Twitter: www.twitter.com/karin_flux

Target Plans to Have In-Store Vertical Farms

Target announced that the company would be adding vertical farms to some of its stores to grow produce indoors

“We sell extremely local produce at Target! No, really! We mean it.”

Target is boldly going where no major retailer has ever gone before by installing a giant farm in the middle of its store. Target’s Food + Future CoLab team announced recently at the White House that it would be installing vertical farms in select store locations, so that fresh fruits and vegetables could be grown in acclimatized conditions and sold directly in the store. Food from the in-store gardens will be on sale starting spring 2017.

The farm will make use of artificial lights and hydroponics to assure proper growing techniques.

“Down the road, it’s something where potentially part of our food supply that we have on our shelves is stuff that we’ve grown ourselves,” Casey Carl, Target’s chief strategy and innovation officer, told Business Insider.

After installing the technology in a few test locations, Target will be able to gage “how involved customers actually want to be with their food,” Business Insider reported.

At first, Target’s farms will be filled with leafy greens, which are easiest to grow vertically. Potatoes, beetroot, and zucchini will be made available in the future.

SEE MORE FARMING NEWS

- This Vertical Farm Skyscraper May Change Our Cities Forever

- The World’s Largest Vertical Farm and More Amazing Exhibits at This Year’s World’s Fair

- The World’s Largest Indoor Vertical Farm Is Being Built in Newark, New Jersey

- Could Drones Be the Future of Farming?

- Biodynamics: Not Just a Way of Farming, But a Way of Life

Target To Test Vertical Farms In Stores

Target is looking to shorten the distance from farm to plate with a planned test of vertical farms

FRIDAY, 10/14/2016

Target To Test Vertical Farms In Stores

Oct 14, 2016

by Tom Ryan

Target is looking to shorten the distance from farm to plate with a planned test of vertical farms, an agricultural technique that involves growing plants and vegetables indoors in climatized conditions.

The initiative, to take place within select U.S. stores, is part of ongoing research and development being pursued by Target’s Food + Future CoLab, a collaboration with the MIT Media Lab and Ideo launched last November that has been exploring urban farming, food transparency and food innovation.

According to Business Insider, tests of the vertical farms could begin in spring 2017. If the trials succeed, Target’s stores will likely be filled with growing leafy greens, the most common stock for vertical farming at present. Potatoes, beetroot and zucchini could potentially be made available as well. MIT could give Target access to ancient seeds for rare tomatoes or peppers.

“Down the road, it’s something where potentially part of our food supply that we have on our shelves is stuff that we’ve grown ourselves,” Casey Carl, Target’s chief strategy and innovation officer, told Business Insider.

Making use of artificial lights, vertical farming is expected to see a growth spurt in part because food cultivated by farms is being challenged by rapidly increasing urban populations. Besides using less water, taking up less space and being closer to the consumer than traditional farming, vertical farming also addresses demands for healthy food without pesticides and avoids weather risks.

On Oct. 3, key members of Target’s Food + Future CoLab team showed off the project at the South by South Lawn (SXSL) festival at the White House. The technologies showcased included the team’s Open Agriculture lab inside the MIT Media Lab that’s exploring vertical farming and ways climate and other factors affect food production.

“Open Agriculture is about creating more farmers,” said Caleb Harper, principal scientist at the MIT Media Lab. “About two percent of us in the U.S. are farmers today, and the average age is 58, so what’s the next generation look like? They’re gonna be coders, hackers, makers.”

Why Cities Are the Future for Farming

Self-described nerd farmer Caleb Harper wants you to join his league of high-tech growers

Urban Explorer

Opinion: Why Cities Are the Future for Farming

Self-described nerd farmer Caleb Harper wants you to join his league of high-tech growers.

National Geographic Emerging Explorer Caleb Harper holds lettuce grown at the MIT Media Lab, where he operates a climate-controlled “digital farm” using aeroponics, a network of sensors, and LED lighting.

By Caleb Harper

PUBLISHED October 14, 2016

The landscape of our food future appears bleak, if not apocalyptic.

Humanity’s impact on the environment has become undeniable and will continue to manifest itself in ways already familiar to us, except on a grander scale. In a warmer world, heavier floods, more intense droughts, and unpredictable, violent, and increasingly frequent storms could become a new normal.

Little wonder that the theme for this year's World Food Day, which happens on Sunday, is “Climate is changing. Food and agriculture must too.” The need for an agricultural sea change was also tackled at the recent South by South Lawn, President Obama’s festival of art, ideas, and action (inspired by the innovative drive of Austin’s SXSW), where I was honored to present.

As our global agricultural system buckles under its own weight, we’re losing our farmers and we’re not creating more. In the U.S. alone, only 2 percent of the population is involved in farming, with 60 percent of our farmers above the age of 58. We’re also experiencing a dramatic move away from rural areas, our traditional growing centers. The UN estimates that by 2050, 6.5 billion people will be living in cities, nearly double what it is today.

Those of us at the helm of agricultural innovation simply must tack into these winds of change—and I see the tremendous potential of the city as a sustainable solution. After all, the domestication of plants gave rise to the first human settlements—our original cities were literally rooted in agriculture. Since then, city life has parted ways with it entirely, as urbanites have become almost completely disconnected from their food sources. But the reintegration of farming into the city is beginning to close the circle. Urban farming could not only feed future generations, but also create appealing clean-tech jobs for the waves of new “immigrants” that cities across the world will see in coming years.

Food Computers: Are These Devices the Future of Agriculture?

Harper takes us on a tour of his lab, which he envisions could be adapted for individual home use, shipping container-size for cafeterias and restaurants, and warehouses of “food data centers” capable of industrial-scale production.

Detractors of urban farming often scramble to point out that the production potential of urban farms is so minimal as to be insignificant. From where I’m standing, this is a dangerously shortsighted perspective. There are two major roles for urban agriculture: yes, the actual production of food intended to feed large numbers, but also the cumulative social benefit of cultivating what we eat. While I anticipate that eventually high-tech urban farming will account for at least 30 to 40 percent of an individual’s diet, the invaluable “product” of human-centered endeavors like farm stands and school and urban gardens lies in weaving communities together and building a foundation for food education.

Of course, we can’t expect a community garden to have the same production capacity as a conventional, massive monoculture farm or—wait for it—a multitiered, digitally integrated vertical farm. That doesn’t mean the community garden has no true value; the amount of calories it yields shouldn’t be the sole metric of its worth.

Instead, we need a renewed appreciation of the myriad benefits of growing food in the city. They range from the healing effect on veterans tending to patches in community gardens, witnessing the transformation of their plants, to the physical benefits of getting a student outside in a school garden while seeing the lessons of the classroom come to life in a burgeoning vegetable.

During World War II, victory gardens were planted both in private residences and public parks to boost morale as much as food supply. That tradition continues in the work of modern pioneers like Ron Finley, the “gangsta gardener” of Los Angeles, who similarly empowers communities by planting beautiful, defiant gardens in abandoned lots, traffic medians, and along curbs, and Will Allen, the founder of a Milwaukee non-profit center for urban agriculture training—teaching people to grow food in neighborhoods that are essentially food deserts dominated by drive-thrus.

Harper inspects a developing chocolate bell pepper. His team creates specific conditions—he calls them climate recipes—to produce plants with unique qualities of color, size, texture, taste, and nutrient density. A pepper grown in his Massachusetts lab could have the features of one grown in, say, Central America.

At the same time, technological leaps in urban agriculture are attracting bright, science-minded youth in droves and paving the path for high-volume production in cities. We’re seeing vertical farms—controlled environment agriculture—get smarter and larger. These aren’t necessarily new methods, but we are reaching a point at which they are becoming more energy efficient and cost effective. At the most cutting edge are “agri-culturing” companies like Modern Meadow and Perfect Day, culturing meat from mammalian cells and fermenting milk from yeast, moving meat and dairy production into cities.

At the MIT Media Lab, where I run the Open Agriculture Initiative, we’re developing digital farming through what we call “the food computer.” Along with aeroponic technology, we use a network of sensors to monitor a plant’s water, nutrient, and carbon needs and deliver optimal light wavelengths—not just for photosynthesis but to change flavor. This allows us to recreate climates that yield, for example, the sweetest strawberries.

Our entire endeavor is open source. We’re now piloting it outside the lab in Boston schools, and we see a near future where farmers can build their own food computers, using instructional videos and schematics already available online, and larger-scale units for restaurants, cafeterias, and industrial production—all in the city. By bringing agriculture home, we’ll have access to fresher, more nutritious food and potentially reduce spoilage and waste.

Our ultimate #nerdfarmer goal is to develop a database of climate “recipes”— for example, the ingredients for mimicking the Mexican climate that produces those sweet strawberries. We hope to pair that database with assembly kits for “personal” food computers that will be increasingly accessible, with the goal of creating and networking a billion farmers by providing access to the tools and the data required to both grow their own food and generate even more data to share—a sort of global “climate democracy” to see us through a world in flux.

Yet even at our post at the high-tech end of the spectrum, we share a common goal with even the smallest, most traditional city garden—to serve our community by creating a new lexicon of food values for the future.

A Food Forest Grows in Brooklyn

Swale aims to turn public art into public service by providing free fruits and vegetables to all.

A Food Forest Grows in Brooklyn

Swale aims to turn public art into public service by providing free fruits and vegetables to all.

In the spring of 2010, The New York Times made a mistake that required more than a sidebar correction. “On Second Thought, Don’t Eat the Plants in the Park,” read the City Room blog headline. The story retracted earlier advice to pick the delicious day lily shoots in Central Park. It’s illegal, for starters—but there was something else.

“It’s like the old adage here,” Adrian Benepe, the city’s parks commissioner, told the paper. “If 15 people decide to go harvest day lilies to stir-fry that night, you could wipe out the entire population of day lilies around the Central Park reservoir.”

This is the principle behind the tragedy of commons, an economic theory that says shared spaces result in selfishness. It’s a theory Swale—a free-to-all floating garden docked at Brooklyn Bridge Park’s Pier 6—has disproved since it began traveling New York’s waterways in June.

“Nobody has really over-picked,” said artist Mary Mattingly, who helped design the garden. That people would show care, generosity, and enthusiasm for the shared space was always the hope—but it became “the thing we have definitely learned on this project,” Mattingly said.

Working with a host of collaborators, Mattingly planted a 130-by-40-foot floating platform garden that’s produced an edible Eden of fruits and vegetables: raspberries, grapes, strawberries, apples, persimmons, potatoes, asparagus, bok choy, chamomile, and comfrey. It’s a project that sits at the intersection of public service and public art, and because it’s on the water, Swale slips through the city’s prohibition on growing and picking food in public spaces.

About 500 people wander through the space each day, discovering the medicinal properties and uses for the plants and herbs and harvesting whatever they please. The perennial garden was designed according to food forest principles. The low-maintenance design system uses companion planting to add nitrogen to the soil, which creates a productive hybrid of garden, orchard, and woodland.

“It grows back the next year stronger and bigger and provides more food every year,” Mattingly said. “It’s kind of the opposite of what agricultural annual farming does.”

The barge has docked throughout the city, but the response has been most enthusiastic in Brooklyn, Mattingly said. The borough has the greatest food insecurity in the city, according to a study released in September by the Food Bank for New York City, a finding that surprised even the boss of the organization.

“I stopped what I was doing and said, ‘Excuse me?’ ” Margarette Purvis, chief executive of the Food Bank, told The New York Times. “When we think of Brooklyn we think of it as a foodie paradise; we think of the beautiful brownstones and we think of the high-rises. And the view from the high-rises is need.”

Swale’s mission differs from that of more traditional antihunger organizations, which might focus on finding support and food for families to eat after benefits from state and federal nutritional assistance programs and free school lunches have been exhausted. Rather, it aims to “reimagine food as a public service” in which more fresh food could be available for free and accessible to people throughout the city.

“Food as a public service is thinking about ‘Can New York City Parks change their maintenance plan slightly so that it accommodates more perennial edibles?’ ” Mattingly said. In addition to grocery stores, farmers markets, and community gardens, the city’s public green spaces could also grow food-forest gardens.

“What we’re hoping with growing more edible perennials in public spaces is that people will have access to fresh healthy food and for free,” she said. “What if we could make it safer and more of it? That’s not saying that you’re going to get all of your food. It’s more about regeneration or resiliency.”

It seems more possible than ever. This month, Swale held a public panel discussion with the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, the National Forestry Service, and community garden representatives to talk about foraging concerns and how to make safe spaces for public food production in the city. The parks department’s concerns are numerous but “not insurmountable,” Mattingly said.

“Our goal is really to align with New York City Parks and be at a pier in a New York City park permanently,” she said. “That’s what we’re working on.”

Until next month, when the barge will travel upstate to overwinter, visitors can fill a tote bag with kale, taste a leaf of comfrey, or gather a handful of mint. They can taste and touch and start talking.

“There’s enough to start conversations that most people don’t have as they go about their daily business, and that’s what makes it wonderful,” said photographer Joey O’Loughlin, whose exhibit Hidden in Plain Sight puts faces to the plight of hunger in New York City. “You’re starting to have a conversation about fresh food in a real way.”

Being parked at bustling Brooklyn Bridge Park—amid soccer games and barbecues and throngs of people—brings the issues of food accessibility front and center.

“There’s all kinds of ways to get people literally on board,” O’Loughlin said. “If you start to feel ownership of what’s possible from the planet, then there’s demand to create affordable food for everyone.”

Will This New Bill Level the Playing Field for Urban Farms?

Michigan Senator Debbie Stabenow just introduced urban farming legislation in anticipation of the 2018 Farm Bill. Will it stick?

By Jodi Helmer on October 13, 2016

Urban farming received a legitimizing nod last month when Senator Debbie Stabenow (D-Michigan) introduced the Urban Agriculture Act of 2016 in hopes of getting it included in the next Farm Bill.

In a call with reporters, Stabenow described the act as an important document, “To start the conversation and create the broad support I think we will have in including urban farming as part of the next Farm Bill.”

The bill aims to create economic opportunities for urban farmers, expand U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) farm loan programs to urban farmers, support the creation of urban farm co-ops to help bring products to market (and allow those co-ops to manage loans for urban farmers), invest in urban ag research, and improve access to fresh, local foods.

The bill is long overdue, according to Malik Yakini, executive director of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, the nonprofit that operates D-Town Farm, the Detroit farm where Stabenow announced the legislation.

“Overall, I think the bill is aggressive and it’s a significant step forward that Senator Stabenow is recognizing the importance of urban agriculture,” Yakini says.

Whether the legislation will make it into the final 2018 Farm Bill is yet to be seen. But if it does, it would be the first time urban farmers have been included in the federal legislation. And it could provide important protections for urban farm businesses in the case of bad weather, disasters, and market shifts.

Wes King, policy specialist for the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition(NSAC), points to the provision that would provide the USDA the ability to allow urban farmers to use contract and local pricing to recover losses as part of the non-insured disaster assistance program.

“Currently, the coverage uses national commodity prices to reimburse farmers,” King explains. “This works for farmers who get commodity prices for their crops, but in urban agriculture, farmers sell direct-to-consumer or high-end restaurants and are getting premium prices, not commodity prices.”

As part of the bill, Stabenow has also advocated for the creation of an office of urban agriculture under the USDA. The office would coordinate urban agriculture policies and offer technical assistance.

“The legislation is all anchored in the creation of this office, which will act as a force to coordinate urban farming activities and research and ensure that whatever is included in the Farm Bill will be properly implemented,” says King.

But Yakini worries that the advisory committee overseeing the new office might not be representative of all urban farmers. “There has been a historic marginalization of Black farmers,” he explains. “I hope that the committee that appoints the advisory board recognizes that, but we won’t know until we get there.”

Funding is also a major concern, as the bill only proposes $15 million in new funding—a drop in the bucket when looked at in the context of the overall Farm Bill, which accounts for $156 billion in 2016 alone.

Tyson Gersh, president of Detroit-based Michigan Urban Farming Initiative says, “It’s been difficult for urban farmers to take advantage of funding opportunities to support their work because [funding] is designed around traditional agriculture.”

To get by, many urban farmers have either taken advantage of “borrowed” land and built infrastructure from free and found materials or engaged in public-private partnerships. The struggle for farms that fall somewhere in the middle could be eased through more federal funding. “A new resource platform could enable the spectrum to be more fully populated,” says Gersh.

Indeed, the bill recognizes the diversity of urban farming operations and includes a specific provision to improve access to USDA farm programs like technical assistance, loans and insurance, and uses conservation grants to support access to land and production sites for farmers operating rooftop or vertical farms.

The nod to urban food production ought to be welcome news for operations like Bright Farms, Detroit’s Hantz Farm, and Square Roots, a Kimbal Musk-backed urban farming accelerator to help millennials launch vertical farming operations.

During the press call, Stabenow acknowledged that the funding for these initiatives would come from expanding existing loan programs, which could cause urban farmers to compete with other farmers for the same pot of funding.

“We don’t want to take funding away from traditional rural farmers,” Yakini says. “This is not urban ag versus rural ag.”

Stabenow explained the need to expand funding opportunities, noting, “If we can make [loans and risk management tools] available then other bankers will be more willing to participate with our urban farmers.”

But Gersh fears that the wrong type of funding could have a deleterious effect.

“I’d rather see resources allocated toward self sufficiency,” he says. “I’d hate to see our entire industry disappear overnight when the bills that provided the funding to create all of this growth are overturned and the funding disappears.”

Karen Washington also has concerns about the dollars and cents of the proposed legislation. The urban farming activist and farmer/founder of Rise & Root Farm in New York is concerned that the bill emphasizes profit-driven farming rather than urban food access.

“Urban agriculture should be in the Farm Bill … and the fact that [this bill] is even part of the conversation is huge,” she says. “But the heart of this bill cannot be profit-driven. A lot of the emphasis is on the commercialization of urban agriculture. This is not just about profit. Race economics have to be brought into the conversation.”

Yakini also expresses concern about the potential negative impacts of the bill on people of color. He’s particularly concerned by the prospect of funding for this bill coming out of the nutrition portion—which accounts for the large majority—of the farm bill “We do not want to see this bill funded by reducing SNAP benefits,” he says

There are, indeed, kinks to be worked out.

On the press call, Stabenow acknowledged the bill has little chance of passing in its current form. But, it could make waves regardless.

For starters, it could sway city and state-level lawmakers who are on the fence about updating dated legal language that puts urban farmers at odds with municipalities.

“[The bill] provides good opportunities for the federal government to step in and tell cities, ‘We’ve done the research and you’re obliged to give it a chance,’” Gersh says.

For Karen Washington, the message the proposed bill sends is a step in the right direction.

“Until now, no one has taken growing food in cities seriously,” she says. “We’ve had to fight to make our way, making something out of nothing while people treated [urban farming] like it was a hobby. This bill validates that urban farming is not going away and needs to be an important part of the conversation.”

Target Experiments With In-Store Vertical Farms

Last year Target announced a collaboration with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and design firm IDEO to explore urban farming and other food-related research

Target Experiments With In-Store Vertical Farms

Author: Daphne Howland @daphnehowland

Published: Oct. 7, 2016

Dive Brief:

As part of its food innovation efforts, Target is researching vertical farming, an agricultural technique to grow plants and vegetables indoors in climatized conditions, and says food from the in-store gardens could go on sale as early as next spring, Business Insider reports.

The effort is a key part of growing the retailer's $20 billion food business, Target's Chief Strategy and Innovation Officer Casey Carl told Business Insider. “We need to be able to see more effectively around corners in terms of where is the overall food and agriculture industries going domestically and globally,” he said.

Last year Target announced a collaboration with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and design firm IDEO to explore urban farming and other food-related research.

Dive Insight:

Target's investments in grocery innovation could be a huge differentiator in a fiercely competitive grocery environment, which includes Wal-Mart (which gets more than half its revenue from grocery) and a host of full-line grocery stores.

That would be especially so if Target and its research and innovation partners can grow tomatoes and other foods from rare seeds saved in various “seed banks” around the world. Those plants have the potential to yield varieties not seen or tasted in quite a long time, which could set Target's produce apart from that grown by agribusiness.

Grocery has been an especially tough area for Target, showing slim margins and presenting tricky loss prevention challenges. Earlier this year the retailer took steps to head off problems with perishable losses higher than the industry average: Target has found it particularly difficult to stave off spoilage because customers aren't coming in often enough for perishable foods.

In response, Target announced it is assembling dedicated grocery teams, ranging from 10 to 60 employees, to work exclusively in grocery sections and receive special training on packaged and fresh food. There are also plans to increase grocery promotions and marketing efforts.

Target has already rolled out the revamped grocery effort in about 450 stores, with another 150 to follow by October. Target's consistent emphasis on fresh and organic foods may help its smaller TargetExpress stores, which contain a large amount of grocery offerings with the hope that nearby customers will use them as a grab-and-go destination for a quick snack or dinner.

Recommended Reading:

Follow Daphne Howland on Twitter

Here’s How Scraps Can Help Grow The Food Of The Future

This mobile aquaponic farm could be a game changer.

Senior Reporter, The Huffington Post

Americans waste millions of tons of food each year. But what if that same waste could help power a more sustainable food supply?

It’s tough to think of something more mundane than getting your electric bill in the mail. But that’s what launched two Chicago scientists down a path that just might lead to a farming revolution.

About five years ago, chemistry professor Elena Timofeeva and physics researcher John Katsoudas, who both work at the Illinois Institute of Technology, began to dabble in aquaponics, a soil-free method of farming that grows plants and aquatic life through connected systems.

The two, who are married, built an aquaponic system in their basement and began growing produce. But the eye-popping electric bill quickly showed them that the cost of powering their fledging farm was far greater than what they could grow. Power costs, it turns out, are a major drawback to the aquaponics industry.

“A couple of pounds of tomatoes were not worth the extra $200 on our bill,” Timofeeva told HuffPost.

The scientists began wondering what a more cost-effective approach to powering an aquaponic farm might look like ― a challenge they have been chasing ever since then.

They believe they’ve found an answer: a stackable, mobile aquaponic growing system that can be operated totally off the grid.

Physics researcher John Katsoudas and chemistry professor Elena Timofeeva of the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago believe their new invention could help feed the world.

The system they invented, housed inside a 45-foot shipping container, generates energy by feeding food waste into a biodigester that works like a mechanical stomach to convert the material into methane. The gas is used as fuel for a generator that powers the aquaponic farm’s pumps and lights.

The units, developed in a collaboration with Nullam Consulting, a firm specializing in anaerobic digestion systems, will be sold for $150,000, according to Timofeeva. Aquaponic farmers can recover their investment in two or three years, she and Katsoudas said, with up to $80,000 in annual profit from what they grow with the system.

Farmers can harvest 14,500 pounds of fresh produce annually with the system — like leafy greens, tomatoes, peppers and even root vegetables. Additionally, 1,100 pounds of fresh fish could be raised inside the system, and 45 tons of organic fertilizer is a byproduct of the anaerobic digester. Plus, farmers can collect fees from providers of food scraps, like grocery stores and food processing facilities.

The aquaponic system uses dramatically less water than traditional farming, and diverts a significant amount of food waste from landfills.

“We want to bring all the technology and innovation together in a very compact, mobile, independent system that can be transported while still producing, and can be dropped wherever food is needed,” Timofeeva said.

A provided diagram shows how they have designed the AquaGrow system, combining an aquaponic farm operation and an anaerobic digester in one container unit, to work.

The ambitious concept is still in its early stages. The scientists are raising funds to build a full-scale prototype of their design. They’ve already attracted attention from the likes of Silicon Valley’s Cleantech Open Accelerator, which named the couple’s startup, called AquaGrow, a semi-finalist in its funding competition.

Some researchers have been skeptical of aquaponic startups’ claims and question the AquaGrow projections.

Stan Cox, a lead scientist at the Land Institute, a nonprofit based in Salina, Kansas, has been a prominent critic of indoor vertical farms, which typically rely on systems like AquaGrow’s.

Cox questioned whether such a system could produce enough food to justify the resources needed to power artificial light and climate-control mechanisms to protect the plants.

Aquaponics, obviously, is a lot more complex than growing a plant in a traditional way outdoors.

“When we’re growing a crop out in the field, the energy situation is pretty simple,” Cox told HuffPost. “When you’re going through a more convoluted process converting biomass [through the digester] and using artificial light, there’s a loss of energy at every step.”

Aquaponic Farming Is The Next Big Agricultural Thing

Stephen Ventura, a soil science professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who also has expressed skepticism of similar operations, said he sees promise in the AquaGrow project, but is concerned with its complexity.

“They are talking about moving and containing an immense amount of material,” Ventura wrote in an email to HuffPost. “And they’re talking about doing this with not one but three biological systems that are finicky to manage, let alone keep in mutual balance.”

Still, Timofeeva and Katsoudas are confident. They project that their system will require some 900 pounds of food waste per day to operate. Farmers can easily obtain that much material by developing a relationship with a local grocery store or school cafeteria, both of which have a reputation for wasting many tons of food daily, Timofeeva said.

As for the tricky logistics of the AquaGrow system, Timofeeva and Katsoudas said they’ve already succeeded in achieving balance within their system and making it easy for an operator to maintain that balance. They still need a prototype to prove it.

The scientists said AquaGrow will help feed a growing world population in a more sustainable way, allow under-resourced neighborhoods access to fresh foods, and offer an easily movable source of sustenance for communities hit by a hurricane or other natural disaster.

“Nothing prevents these systems from being picked up and dropped off in the event of a FEMA emergency. They’re ready to go,” Katsoudas said.

And, with problems like world hunger and climate change, help is urgently needed.

“We’re taking what we’ve got in the labs and we know we can do to actually turn it into something that can be utilized right now,” Katsoudas added. “We know the world’s going to need technology like this.”

Joseph Erbentraut covers promising innovations and challenges in the areas of food and water. In addition, Erbentraut explores the evolving ways Americans are identifying and defining themselves. Follow Erbentraut on Twitter at @robojojo. Tips? Email joseph.erbentraut@huffingtonpost.com.

Target Plans To Test Vertical Farm 'In-Store Growing Environments' In 2017

Target plans to test vertical farm 'in-store growing environments' in 2017

Target plans to test vertical farm 'in-store growing environments' in 2017

DANA VARINSKY0OCT 5, 2016, 09.30 PM

Vertical farming, an agricultural technique that involves growing plants indoors in precisely programmed conditions, is spreading rapidly. Kimbal Musk (Elon's brother) is open in Brooklyn, the world's largest vertical farm is set to open this fall, and personal indoor growing boxes are being developed for home use.

Soon, an unlikely company will also start using the technology: Target.

"Down the road, it's something where potentially part of our food supply that we have on our shelves is stuff that we've grown ourselves," Casey Carl, Target's chief strategy and innovation officer, tells Business Insider.

In January, Target launched the Food + Future CoLab, a collaboration with design firm Ideo and the MIT Media Lab. One area of the team's research focuses on vertical farming, and Greg Shewmaker, one of Target's entrepreneurs-in-residence at the CoLab, says they are planning to test the technology in a few Target stores to see how involved customers actually want to be with their food.

"The idea is that by next spring, we'll have in-store growing environments," he says.

During the in-store trials, people could potentially harvest their own produce from the vertical farms, or just watch as staff members pick greens and veggies to stock on the shelves.

Most vertical farms grow leafy greens, but the CoLab researchers are trying to figure out how to cultivate other crops as well.

"Because it's MIT, they have access to some of these seed banks around the world," Shewmaker says, "so we're playing with ancient varietals of different things, like tomatoes that haven't been grown in over a century, different kinds of peppers, things like that, just to see if it's possible."

Because the CoLab is a research partnership, the projects don't only focus on technologies that could one day be used in Target's stores or supply chain.

For example, the team is currently developing a small vertical farm would allow farmers or researchers to conduct agricultural experiments and trials. A medium sized version, which is being tested in an off-campus MIT facility, would measure a few hundred square feet and could be used to grow produce for a restaurant or store.

The largest vertical farm the team has developed, at just under 8,000 square feet, could grow crops for an entire neighborhood or community. That big farm is currently being tested in India, where the team is attempting to grow non-food crops, like cotton, that often use up soil, water, and resources that could otherwise be used to grow food.

The CoLab team has also used the same research to create a self-contained growing box that can educate kids about how food is grown. On September 30, that product, called Poly, is being given to 35 public school classrooms in Boston and Minneapolis. Shewmaker says the team hopes to eventually make a market-ready version that could be sold to textbook or curriculum companies.

Carl says anticipating and shaping the future of food - at Target and beyond - is essential to the company's growth.

"Food is a big part of our current portfolio today at Target - it does $20 billion of business for us," he says. "We need to be able to see more effectively around corners in terms of where is the overall food and agriculture industries going domestically and globally."

Urban Produce To Hire Indoor Growers

Prospective growers will attend Urban Produce University in Irvine to prepare to work for prospective licensees in China, Canada, Mexico and Japan in 2017, according to a news release

By Mike Hornick October 03, 2016 | 1:44 pm EDT

Urban Produce, Irvine, Calif., plans to hire Controlled Environmental Agriculture indoor organic vertical growers to support its licensees as part of phase two of the company’s expansion program.

Prospective growers will attend Urban Produce University in Irvine to prepare to work for prospective licensees in China, Canada, Mexico and Japan in 2017, according to a news release.

Urban Produce, which launched in January 2015, holds patents in seven countries including the U.S. and Canada.

“As we move into the next phase of our business we look forward to building vertical growing units all over the world,” Ed Horton, President and CEO, said in the release.

With world population projected to increase 70% by 2050, Urban Produce’s plans for expansion aim to help combat global hunger and eradicate food deserts.

“Our goal of sustainability incorporates our atmospheric water generation and the use of solar-generated power in order to build anywhere,”

Kimbal Musk and Dan Barber Clash About The Future of Food

September 28, 2016 — 8:36 AM CDT

Kimbal Musk, co-founder of farm-to-table restaurant group the Kitchen, board member at Chipotle, Tesla, and SpaceX, and younger brother to Elon, thinks hydroponic vertical farming—that is, soil-less, indoor, LED-lit agriculture—is the future of food.

Dan Barber, renowned chef, restaurant owner, author of bestseller The Third Plate, and crop rotation evangelist, strongly disagrees.

In August, Musk announced a new venture called Square Roots. He hopes it will get millennial city dwellers to become farmers—who grow their goods in shipping containers. In his Medium post, he described “campuses of climate-controlled, indoor, hydroponic vertical farms, right in the hearts of our big cities.”

Chef Dan Barber (left), Kimbal Musk (center), and Elly Truesdell speak onstage at The Next Kale and Quinoa panel at the New York Times Food For Tomorrow Conference 2016 on Sept. 27, in Pocantico, N.Y. Photographer: Neilson Barnard/Getty Images for The New York Times

Musk's vision calls for containers with hydroponic vertical farming technologies, controlled temperatures, artificial lighting, and soil-less nutrition. At the New York Times Food Conference on Tuesday at Barber’s Blue Hill at Stone Barns in Pocantico, N.Y., Musk explained how lights inside the containers can be dialed to yield particular flavors and, most of all, how it can bring young people into farming industry. The influx of young blood is badly needed. The average age of farmers climbed from 50.5 years old in 1982 to 58.3 years old in 2012.

Musk is hardly the first to champion vertical farming. Frequent travelers may have noticed the aeroponic model at Chicago’s O’Hare airport, where such herbs as purple basil and chives grow alongside vegetables, including green beans, Swiss chard, and Bibb lettuce, year-round. Companies like Vertical Harvest in Jackson Hole, Wyo., FarmedHere in Bedford Park, Ill., and Alegria Fresh in Irvine, Calif., are also betting on versions of the new technology. A 2015 report by New Bean Capital, Local Roots, and Proteus Environmental Technologies hailed indoor agriculture as "the next major enhancement to the American food supply chain."

Proponents boast about the water saved, the pesticides avoided, and the faster growing times in an environment in which seasons don’t matter.

Not everyone, though, is on board with dirt-less farming.

“It’s not making me hungry,” Chef Dan Barber told the audience at a panel on new food trends. Barber is a preacher of the power of soil. He often explains how crop rotations—growing not just wheat, but also legumes, rye, and lesser known plants—not only provide tables with more diverse foods but improve the flavor of the primary crops, such as the wheat itself.

“I’d rather invest intellectual capital into the soil that exists outside,” said Barber, though he added that he doesn't know much about vertical farming. Still, he wants to see more excitement about what goes on underground, instead of growing food above it. “When Kimbal says you can dial in the flavor and colors you want, I don’t know that I want that kind of power,” Barber said. “I’d rather have a region or environment express color and flavor.”

Elly Truesdell, the Northeast regional forager—a fancy term for buyer—for Whole Foods Market, agreed with him. “I’ve never had a piece of produce from a hydroponic grower that tastes as delicious to me [as the soil grown version],” she said on the panel.

Both Musk and Barber agree that the current corn- and soy-centric agricultural system that grows more feed for animals than food for humans is broken; they just see vastly different solutions to the problem.

Even Musk isn’t pretending that shipping containers are already producing the big league results he's promising. “We buy 99.99 percent of our products from soil-grown foods,” he admitted of his restaurants.

Local Food Is Great, But Can The Concept Be Taken Too Far?

The commonly held belief that reducing “food miles” is always good for the environment turns out to be a red herring.

The commonly held belief that reducing “food miles” is always good for the environment turns out to be a red herring.

One of the most interesting developments in American agriculture during the last decade has been the rise of the local food movement.

It’s incredibly popular. People love the idea of eating food that is grown nearby on surrounding farms. It helps increase the sense of authenticity and integrity in our food. Also, the food can often be fresher and tastier. Many folks also like that the supply chain — the path food travels from the farmer’s field to the dinner fork — is shorter, is more transparent and supports the local economy. And who doesn’t love going to a wildly colorful farmer’s market or a beautiful farm-to-table restaurant and learning more about the farms and farmers who grew our food? No wonder local food is so popular.

Local food can also be good for the environment, especially if it reduces food waste along the supply chain. Many local farms are organic or well-run conventional farms, which can produce many benefits to soils, waterways and wildlife. And, in some places, local grass-fed ranches are trying to sequester carbon in the soil, offsetting at least part of beef’s hefty greenhouse gas emissions. Done right, local food can have many environmental benefits.

Without a doubt, local food has a great set of benefits. But the commonly held belief that reducing “food miles” is always good for the environment because it reduces the use of transportation fuel and associated carbon dioxide emissions turns out to be a red herring. Strange as it might seem, local food uses about the same amount of energy per pound to transport as long-distance food. Why? Short answer: volume and method of transport. Big box chains can ship food more efficiently — even if it travels longer distances — because of the gigantic volumes they work in. Plus, ships, trains and even large trucks driving on interstate highways use less fuel, per pound per mile, than small trucks driving around town.

But don’t feel bad. It turns out that “food miles” aren’t a very big source of CO2 emissions anyway, whether they’re local or not. In fact, they pale in comparison to emissions from deforestation, methane from cattle and rice fields, and nitrous oxide from overfertilized fields. And local food systems — especially organic farms that use fewer fertilizers and grass-fed beef that sequesters carbon in the soil — can reduce these more critical emissions. At the end of the day, local food systems are generally better for the environment, including greenhouse gas emissions. Just don’t worry about emissions from food miles too much.

Without a doubt, local food has a great set of benefits. And it’s just getting started.

From Local to Super-Local

We have also seen a movement toward what you might call“super-local” food, where people grow more food right in the city. In other words: urban agriculture.

There are commercial scale urban farms popping up, like Growing Power in Milwaukee, that grow food in vacant lots and create badly needed jobs in urban neighborhoods. Others, like Gotham Greens, are growing food in rooftop greenhouses in major cities. People are also starting community gardens in their neighborhoods, where folks can share an area of land — maybe in a city park or a school yard — to grow fruits and vegetables. And, of course, many people grow super-local food at home, in their yards, or on their patios and decks. In fact, my wife and I have always grown salad greens, herbs, vegetables, and a wide range of fruits at our place — whether in a tiny yard converted to gardens and orchards in Saint Paul, Minnesota, or a variety of potted vegetables, herbs, and fruit trees on a deck in San Francisco. It tastes great, and there is a lot of satisfaction in doing it yourself. And I love that our daughters grew up — even as city kids — knowing a little bit about where food comes from.

While it’s not a silver bullet solution to all of our global food problems, [local food is] an exciting, powerful development, and it can have important nutritional, social, economic and environmental benefits if done well.But, despite these great advances, we need to remember that urban food can’t feed everyone. There’s just not enough land. In fact, the world’s agriculture takes up about 35 to 40 percent of all of the Earth’s land, a staggering sum, especially compared to cities and suburbs, which occupy less than 1 percent of Earth’s land. Put another way: For every acre of cities and suburbs in the world, there are about 60 acres of farms. Even the most ambitious urban farming efforts can’t replace the rest of the world’s agriculture. Fortunately, urban farmers are smart and have focused their efforts on crops that benefit the most from being super-local, including nutritious fruits and vegetables that are best served fresh. In that way, urban food can still play a powerful role in the larger food system.

So there’s a lot to be excited about with local food. While it’s not a silver bullet solution to all of our global food problems, it’s an exciting, powerful development, and it can have important nutritional, social, economic and environmental benefits if done well.

Taking It Too Far: Hyper-Local Food and Indoor “Farms”

Local food is a very welcome development. But can we take it too far?

Yes, I’m afraid we can — especially when we start to grow foodindoors with energy-intensive, artificial life-support systems.

We’re now seeing what you could call “hyper-local” food, where crops are grown inside a building, whether a warehouse, an office building, a grocery store or even a restaurant. In the last few years, a number of tech companies have designed indoor, industrial “farms” that utilize artificial lights, heaters, water pumps, and computer controls to grow stuff inside. These systems glow with a fantastic magenta light — from LEDs that are specially tuned to provide optimal light for photosynthesis — with stacked trays of plants, one on top of the other.

Some of the more notable efforts to build indoor “farms” include Freight Farms in Boston. And a group at MIT is trying to create new high-tech platforms for growing food inside, including “food computers.” These folks are very smart and have done a lot to perfect the technology.

At first blush, these “farms” sound great. Why not completelyeliminate food miles, and grow food right next to, or even inside, restaurants, cafeterias or supermarkets? And why not grow crops inside closed systems, where water can be recycled, and pests can (in theory) be managed without chemicals?

But there are costs. Huge costs.

First, these systems are really expensive to build. The shipping container systems developed by Freight Farms, for example, cost between $82,000 and $85,000 per container — an astonishing sum for a box that just grows greens and herbs. Just one container costs as much as 10 entire acres of prime American farmland — which is a far better investment, both in terms of food production and future economic value. Just remember: Farmland has the benefit of generally appreciating in value over time, whereas a big metal box is likely to only decrease in value.

Second, food produced this way is very expensive. For example, the Wall Street Journal reports that mini-lettuces grown by Green Line Growers costs more than twice as much as organic lettuce available in most stores. And this is typical for other indoor growers around the country: It’s very, very expensive, even compared to organic food. Instead of making food moreavailable, especially to poorer families on limited budgets, these indoor crops are only available to the affluent. It might be fine for gourmet lettuce, or fancy greens for expensive restaurants, but regular folks may find it out of reach.

Finally, indoor farms use a lot of energy and materials to operate. The container farms from Freight Farms, for example, use about 80 kilowatt-hours of electricity a day to power the lights and pumps. That’s two to three times as much electricity as a typical (and still very inefficient) American home. And on the average American electrical grid, this translates to emitting45,000 pounds (20,000 kilograms) of CO2 per container per year from electricity alone, not counting any additional heating costs. This is vastly more than the emissions it would take to ship the food from someplace else.

And none of it is necessary.

But, Wait, Can’t Indoor Farms Use Renewable Energy?

Proponents of indoor techno-farms often say they can offset the enormous sums of electricity they use by powering them with renewable energy — especially solar panels — to make the whole thing carbon neutral.

But just stop and think about this for a second.

Any system that seeks to replace the sun to grow food is probably a bad idea.These indoor “farms” would use solar panels to harvest naturally occurring sunlight and convert it into electricity so that they can power artificial sunlight. In other words, they’re trying to use the sun to replace the sun.

But we don’t need to replace the sun. Of all of the things we should worry about in agriculture, the availability of free sunlight is not one of them. Any system that seeks to replace the sun to grow food is probably a bad idea.

Also, These Indoor “Farms” Can’t Grow Much

A further problem with indoor farms is that a lot of crops could never develop properly in these artificial conditions. While LED lights provide the light needed for photosynthesis, they don’t provide the proper mix of light and heat to trigger plant development stages — like those that tell plants when to put on fruit or seed. Moreover, a lot of crops need a bit of wind to develop tall, strong stalks for carrying heavy loads before harvest. As a result, indoor farms are severely limited and have a hard time growing things besides simple greens.

Indoor farms might be able to provide some garnish and salads to the world, but forget about them as a means of growing much other food.

A Better Way?

I’m not the only critic of indoor, high-tech, energy-intensive agriculture. Other authors are starting to point out the problems with these systems, too (read very good critiques here, here, here and here).

While I appreciate the enthusiasm and innovation put into developing indoor farms, I think these efforts are, at the end of the day, somewhat counterproductive.

Instead, I think we should use the same investment of dollars, incredible technology and amazing brains to solve other agricultural problems — like developing new methods for drip irrigation, better grazing systems that lock up soil carbon and ways of recycling on-farm nutrients. We also need innovation and capital to help other parts of the food system, especially in tackling food waste and getting people to shift their diets toward more sustainable directions.

With apologies to Michael Pollan, and his excellent Food Rules, here are some guidelines for thinking about local food:

- Grow food. Mostly near you.

- But work with the seasons and renewable resources nature provides you.

- Ship the rest.