Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Rooftop Farming: How Nature Flourishes On London's Skyline - Plus The Top 5 Edibles For Beginners

Rooftop Farming: How Nature Flourishes On London's Skyline - Plus The Top 5 Edibles For Beginners

25 MARCH 2017 • 8:00AM

The winter purslane at the five star Rosewood Hotel in Holborn is excellent. Served immediately after picking, it is sweet and fresh. Amandine Chaignot, the hotel’s Executive Chef, tells me it’s the best crop they've ever had. However, I’m not eating it in the marble-walled serenity of the restaurant, but in the wind and drizzle on Rosewood’s roof, where it is grown in one of Bee London's rooftop gardens.

The Rosewood London is one of three rooftop farms in the part of London that is calling itself Midtown – the pocket of buses, offices and chain food outlets between Bloomsbury, Holborn and Clerkenwell. Another is sandwiched on a terrace on the first floor of an office block and a third is perched on top of Le Cordon Bleu cookery school, which overlooks the gently peaked roof of the British Museum.

Winter purslane at the Rosewood London CREDIT: RII SCHROER

Bee London, which represents 320 businesses across the area, is working with the Wildlife Trust to design and deliver greening projects to Midtown, helping to tackle air quality and urban sustainability. The rooftop gardens are one example of this. Sean Gifford of Sky Farmers Ltd, who works on Bee London's gardens, hopes the initiative will also change the way people see food by growing it locally.

In a city, that means making the most of every bit of space available – and it transpires that the tops of large buildings provide a lot of room to grow.

Gifford has transformed these wind-blown, sun-exposed spaces into enormous container gardens. Although the Bee London team sets up the farms in the first place (a more complicated process than it may sound – you try hefting 18 tonnes of compost in 20 kilogram bags through a five star hotel) and maintains them, much of the tending is done by volunteers from the buildings they sit on.

In the case of Le Cordon Bleu and The Rosewood London that would be chefs, who are learning about their ingredients in the process, but at the office block it’s lawyers who roll up their sleeves on their lunch break.

Head Gardener for Bee London Sean Gifford at the beehive at Le Cordon Bleu” CREDIT: RII SCHROER

Gifford has mastered a number of ingenious ways to grow in urban landscapes all year round. While I'm touring the rooftop farms on a particularly unpleasant day in early February, there is a lot of life going on.

Mustard, 'Arctic King' lettuce and rainbow chard emerge from the re-appropriated recycling crates which comprise many of the planters (they are cheap, eco-friendly in their re-use and, essentially, lightweight.

With holes drilled in the bottom they are perfect for small crops), three-cornered leekstumble over the sides of containers and mintputs on a good show against the cold.

While the country bemoans a courgette crisis, mizuna, green-in-snow, buckler leaf sorrel and lambs lettuce thrive in these most unlikely of gardens.

Biodiversity is a big part of Bee London's ethos, and as well as the planting and pest-control being chemical-free (although owing to Soil Association restrictions on acknowledging container gardens, the farms aren’t officially “organic”), these urban farms also house wormeries and beehives. Small plots of nettles are allowed to grow because their stems, over winter, provide “homes for allies” – the ladybirds Gifford bought online, were delivered in a box, and now dine on the aphids in the garden.

While the modest greenhouse at the office block currently houses a lemon tree, in the summer it will produce 1,500 vegetable seedlings.

But Gifford recommends Organic Plants as a provider of a diverse range of quality plug plants, and for rookies wanting to grow at home they are perfect, bundling up plants by seasonality to take some of the confusion out of growing produce.

The rooftop farms provide inspiration for those who think small spaces put a stop to growing food. The garden on top of Le Cordon Bleu is tiny, but possibly my favourite. A huge rosemary bush grows joyfully in the warm, cake-scented air that puffs endlessly out of the cookery school’s extractor fans. “It flowers four times a year”, Gifford says.

There’s also stevia, the leaves of which taste 130 times sweeter than sugar (I know because Gifford is very enthusiastic in making me eat everything possible), and is happily overwintering despite hailing from South America.

Fennel loves its windy, sun-exposed situation and there’s a self-seeded gorse bush just beyond the rail where health and safety stops humans from going. As a result, it is massive. Proof, perhaps, that nature can choose to flourish in urban environments, if only it is given half a chance.

For more urban gardening, follow Alice on Instagram.com/noughticulture

A Future Farming Industry Grows In Brooklyn

A Future Farming Industry Grows In Brooklyn

The startup Square Roots is training the next generation of urban farmers in a Bed-Stuy parking lot.

By Alexander C. Kaufman, Joseph Erbentraut

ROOKLYN, New York ― Tobias Peggs is already cultivating leafy vegetables out of purple-lit shipping containers in the parking lot of an old Pfizer factory, just blocks from the projects where the rapper Jay-Z grew up.

What he needs to grow now is an industry.

Eight months ago, Peggs co-founded Square Roots ― a startup that coaches and equips would-be urban farmers with growing materials in repurposed 320-square-foot metal crates. He launched the venture with food and tech entrepreneur Kimbal Musk, the younger brother of Tesla and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk.

Now, 10 farmers are enrolled in Square Roots’ Brooklyn farming program, Peggs and Musk have launched a new delivery service for home-grown salad greens, and they’re deciding where to expand next.

“If we have a campus like this in every city, everyone can buy food from a local farmer,” said Peggs, 45, said as he showed The Huffington Post around his operation.

Located in the shadow of the Marcy Houses, a public housing complex in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, the former pharmaceutical plant that houses Square Roots now also provides office space for scientific research ventures and startups that ferment kombucha and kimchi, make high-end slushies and Madagascan chocolate, and even grow live oysters.

Peggs is Square Roots’ chief executive, and he has lofty plans to topple the industrial giants that dominate grocery aisles. “This is a very long-term play, to bring real food to everyone and unleash, basically, the next generation of leaders in food.”

“Ambitious,” he added with a laugh.

Square Roots was launched under the umbrella of The Kitchen LLC, Musk’s equally ambitious chain of farm-to-table eateries that he hopes will one day take over the food industry sector that TGI Friday’s and Applebee’s currently dominate.

Musk, 44, draws his inspiration from Chipotle Mexican Grill, where he serves as a board member. Chipotle leveraged its use of fresh, non-genetically modified ingredients to become a major rival of McDonald’s, despite charging higher prices. The Kitchen, which has three different restaurant concepts, operates primarily out of the American heartland, with nearly a dozen locations in Chicago, Memphis and throughout the state of Colorado. Another restaurant is slated to open in Indianapolis this year.

Musk and his colleagues are looking at all of those cities as the next possible site for a Square Roots campus.

“My heart is in Memphis, so if it were up to me, that’d be our next city,” Musk told HuffPost on Thursday, stressing that it’s ultimately up to Peggs. He wants to see Square Roots expand rapidly. “We are planning on doing this with thousands of kids a year within a few years.”

If we have a campus like this in every city, everyone can buy food from a local farmer.Tobias Peggs, chief executive of Square Roots

In Colorado, where The Kitchen is headquartered, it’s easy to get local produce, meat and alcohol. But that’s not true in a lot of major cities. That’s the niche Square Roots wants to fill. The company is the country’s first major indoor farming “accelerator” ― Silicon Valley parlance for firms that offer educational training, space and capital to bootstrapped entrepreneurs.

Enrollees complete an eight-week boot camp before setting up shop in one of Square Roots’ 10 shipping containers. They then have the next 10 months to grow vegetables and come up with novel ideas to sell them. Square Roots makes money by taking a cut of the revenue. If an idea takes off, Square Roots buys a stake in the company and introduces the farmer to other investors.

“I visualize opening Fortune magazine in 2050, and there’s a list of the top 100 food companies in America,” Peggs said. “No. 1 is Square Roots. And the other 99 have all been set up by folks who graduated from Square Roots.”

Indoor and vertical farming, essentially a techy subset of greenhouse agriculture, has recently attracted entrepreneurs competing to develop new hardware and the most energy- and water-efficient growing systems.

The benefits of growing indoors are numerous. Farmers don’t need pesticides or herbicides to ward off unwanted pests. They evade droughts, temperature shifts, whipping winds and flooding rains, all of which are becoming more destructive and erratic as greenhouse gases warm the planet and alter the climate. They are free from environmental contaminants ― a big plus in places like Japan, where, since the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, people fear radiation poisoning from food grown outdoors.

And on a baseline level, vegetables grown indoors under precise conditions can be bred to taste better. Peggs said one Square Roots farmer who is cultivating shiso, a red-leafed mint, used data on the climate in Hokkaido, Japan’s breadbasket northernmost island, to replicate conditions there. Instead of raising crops in one country and shipping them to another to be eaten, farmers could cut out the financial and environmental costs of transportation and grow even exotic produce in the dead of a New York winter.

“Let’s say the best basil you ever had was on vacation in Italy in 2006,” Peggs said. “You could look up the data on rainfall, temperatures and weather and grow basil in those exact same conditions.”

In September, Square Roots began working with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to rewrite criteria for government-backed loans, making them more accessible to indoor, urban growers.

The USDA postponed a meeting with Peggs scheduled for Thursday afternoon, hours after agriculture secretary nominee Sonny Perdue testified before a Senate hearing. The USDA did not respond to questions on Friday about the status of changes to the loan applications.

“We want these kids to know they’ll be getting a loan, and they’ll have to pay it back and have to build a business and make money for themselves all in the space of one year,” Musk said. “It’s a loan, not a grant. It’s not a handout; these are real businesses.”

Ten shipping containers like this house Square Roots’ local farming initiative in Brooklyn, New York.

ALEXANDER C. KAUFMAN/THE HUFFINGTON POST

Lettuce and arugula grow on long, vertical trays in the glow of purple LED lights.

ALEXANDER C. KAUFMAN/THE HUFFINGTON POST

A Q & A With The Urban Farmers Behind Farm LA

A Q & A With The Urban Farmers Behind Farm LA

On Their Obsession With Lima Beans And Their plans To Plant Gardens On Abandoned Properties

BY JENNA CHANDLER@JENNAKCHANDLER MAR 24, 2017, 9:30AM PDT

Arlan J. Wood and Emily Gleicher, with their dogs Buck Rogers and Ham Hock, at home in Frogtown.

Every piece of Emily Gleicher and Arlan J. Wood’s yard in Frogtown is used for gardening. The couple grows a myriad of produce, from white sage to sunflowers to strawberry corn to dragon fruit to the most detested vegetable of childhood: lima beans.

The bounty supplements their diet. They make popcorn, salads, citronella oil, and hot sauce, which Wood has named “Caliente Culo.” But it’s the lima beans that help support Farm LA, the nonprofit they founded in May 2015 to turn abandoned and derelict lots into urban gardens for neighbors to enjoy. They sell the legumes in mason jars at farmers markets along with recipes for mashed lima beans and lima bean hummus.

Their love for gardening started after Gleicher relocated from New York City to Los Angeles. She was happy to get away from the cramped, dense neighborhood of Greenpoint, so they took full advantage of their yard in Northeast LA. Gleicher also quickly took notice of the empty lots dotting their neighborhood.

“There are quite a bit of unbuildable hillsides, quite a bit of yucky abandoned properties. We know it’s challenging to fill those properties, because they have their imperfections,” she said. “Why not do something cool with it?”

Gleicher and Wood invited us to their home on a drizzly Tuesday morning. We sat on the porch and talked about how the city might encourage more urban farming, why they love lima beans so much, and their (sometimes emotional) quest to find more land.

Why Lima Beans?

Gleicher: On our first Valentine’s Day, J., in cute-, fresh-, and frantic-boyfriend-mode, at the last minute went to CVS and got me barrettes, and a card, and a lima bean plant that, when it sprouted, said “I love you.” It never actually did sprout that way. That fueled our gardening mode. Our garden was in the works, and when he got that plant for me, we realized lima beans are drought tolerant. We love to grow them on teepees; they trellis up in really fun ways.

All of our lima beans are all from that one plant—every lima bean that’s in our kits. We’re probably third generation at this point.

So a lima bean plant from CVS kickstarted this operation?

Gleicher: We were already starting to fall in love with gardening and we were wanting to do something with the space we were seeing around LA. And, everyone kept telling us when we started, “You’ve got to have a product. You’ve got to have a business plan.” And we were like, “What do you mean? We’re nonprofit!” The lima beans help sustain our nonprofit. It’s not paying us. But it’s paying for snacks for our volunteers. The goal is to get larger spaces so we can grow more lima beans.

A row of potted apple trees in the side yard.

You recently spoke at a city commission meeting to advocate for the city of LA to adopt urban agricultural zones. What are those?

Gleicher: We’re a part of this urban agriculture working group that is run by the Los Angeles Food Policy Council. The council is all about food justice in LA, whether it’s legalizing street vending or keeping food accessible for lower income neighborhoods.

One thing they’re trying to push forward is the Urban Agricultural Zone Act. This act would give property tax breaks to land owners in the city with nothing livable on their parcels—if they partner with farmers like us or if they themselves start using those plots for urban agriculture, which can mean different things, so we’re working to define that with the food policy council.

Wood: There are plots everywhere, plots that are empty. A lot of that is due to red tape. For the Average Joe homeowner, they’re not really usable. So this would give an awesome incentive for them to go, “Oh my gosh, yes, take my hillside for blank number of years.” It saves them a lot on property taxes, and it’s a win-win for everybody.

So you have a list of properties that you’ve been scouting to turn into small farms, right?

Wood: We’ve been going to property tax auctionsfor a few years now.

Gleicher: It’s usually families who unfortunately can’t pay the property tax for whatever reason, and it goes to auction. We’ve found a few and gone but got outbid. It’s a touchy subject. It gets a little tearsy.

Wood: We invest a lot of time looking for the properties.

Gleicher: There was one in October and I think the titles will be public record soon for whoever did win it, and when this act is officially on the books and we can move forward, we want to go to those people, and say, “Hey we know you purchased this property in the auction. If you’re having a hard time building on it, please think of us.”

How else are you finding land?

Gleicher: People reach out to us. Some things we’ve had to say no to, because they’re not really in line with what we’re trying to do, like a property in Laurel Canyon. We want somewhere close to us. But it’s really about trying to stay in a food desert neighborhood, in a low-income neighborhood, a neighborhood that needs beautification. It’s more Northeast LA, and Boyle Heights, and Cypress Park, and Glassell Park.

I imagine someone might contact you to say, “Hey, there’s a vacant plot of land on my street, come plant a garden here.” Great. But maybe you can’t get ahold of the property owner. What other roadblocks are you hitting?

Wood: We’ve tried to do that several times, and it’s a doozy.

Gleicher: It’s public information, so it’s not so much that as it is getting people to get out of their comfort zones and do something that feels out of the norm for them. Some people are against change, some people are against bringing beauty to a neighborhood, because they think it brings other changes, like gentrification. So we’ve experienced a touch of that, too, and understandably so.

How do you convince property owners?

Gleicher: I go for the heart strings: “Wouldn’t you rather see something that can feed a community?”

Wood: “Or beautify a community?”

Gleicher: “Or feed a women’s shelter? And enrich your soil? Nothing is permanent. We’re not planting oak trees. If you ever want to change something, which we hope you wouldn’t, this could all be relocated or transplanted.” We need to work on our elevator pitch, but each property is so unique.

Lima beans could/should be the new kale, says Gleicher.

Tell us about the gardens you have already and where the food goes.

Gleicher: We have 11.5 sidewalk gardens now. (The .5 is a giant fig tree at Cafécito Organico in Frogtown.)

Wood: Soon to be 12. (The 12th will be a patch of barley planted at Frogtown Brewery.)

Gleicher: In the residential areas, the food is for the block. The person providing the water certainly gets first dibs. But it’s to share with neighbors. It’s on them to take care of it. The spirit of this is, “this is for you, take it.” Eventually we want to put in signs that tell you how to take care of it and what each plant is. But for the most part it’s a little wild west right now.

For anyone who now feels inspired to start growing something, what do you recommend?

Gleicher: Herbs. Peppers. Lima beans do really well for us. I know. It sounds like we’re obsessed. But we are.

Urban Farmers Catch New Train

March 24, 2017

The urban farming movement is taking a new twist, or rather, is on a new track. Growers are producing crops in refitted freight train cars, using hydroponics and automated systems equipment.

Each former freight car costs $85,000, not including shipping, with each “controlled environment” container producing an estimated average annual profit of $39,000. A 320-square-foot car is capable of producing roughly what a three-acre farm could, while using 95% less water than traditional farms.

Boston-based Freight Farms, the manufacturer of the equipment, says the most popular destinations for the 7.5-ton high-tech freight cars are urban areas across the country. The movement recently expanded into Arizona, where two urban farmers are growing crops in the cars.

The goal is to bring viable, space-efficient farming techniques to all climates and skill levels year-round. Quality and sustainability is enhanced, since produce travels shorter distances too.

Olive Trunk Farm Seizes the Opportunity To Feed Texas Town

It took a bout of food poisoning to convince Scott Rowdon to grow his own food, but now the Texas farmer has his eyes set on growing fresh, healthy food for everyone around him

Olive Trunk Farm Seizes The Opportunity To Feed Texas Town

Posted by Eve Newman on March 24, 2017

Food poisoning spurs local food conversion

It took a bout of food poisoning to convince Scott Rowdon to grow his own food, but now the Texas farmer has his eyes set on growing fresh, healthy food for everyone around him.

Rowdon’s foray into farming began with an emergency room visit following dinner at a local burger joint near his home in Little Elm, Texas, about two years ago. “It came about kind of on accident,” he said.

After his recovery, Rowdon decided he wanted to grow more of his own food. But like much of Texas, Little Elm — which sits on the northern side of the Dallas/Fort Worth metro area — isn’t celebrated for its soils.

“Down here in Texas, we have horrible clay soil,” Rowdon said. “It is horrible. But I thought, there had to be a way to be able to grow.”

He began exploring aquaponics and built his first system using a 55-gallon drum and a stock tank with catfish, all indoors. Then he came across Bright Agrotech’s hydroponic technology and purchased a ZipGrow Tower system, which soon became a second system, then a wall, then 25 Towers.

“It just continued to grow,” he said.

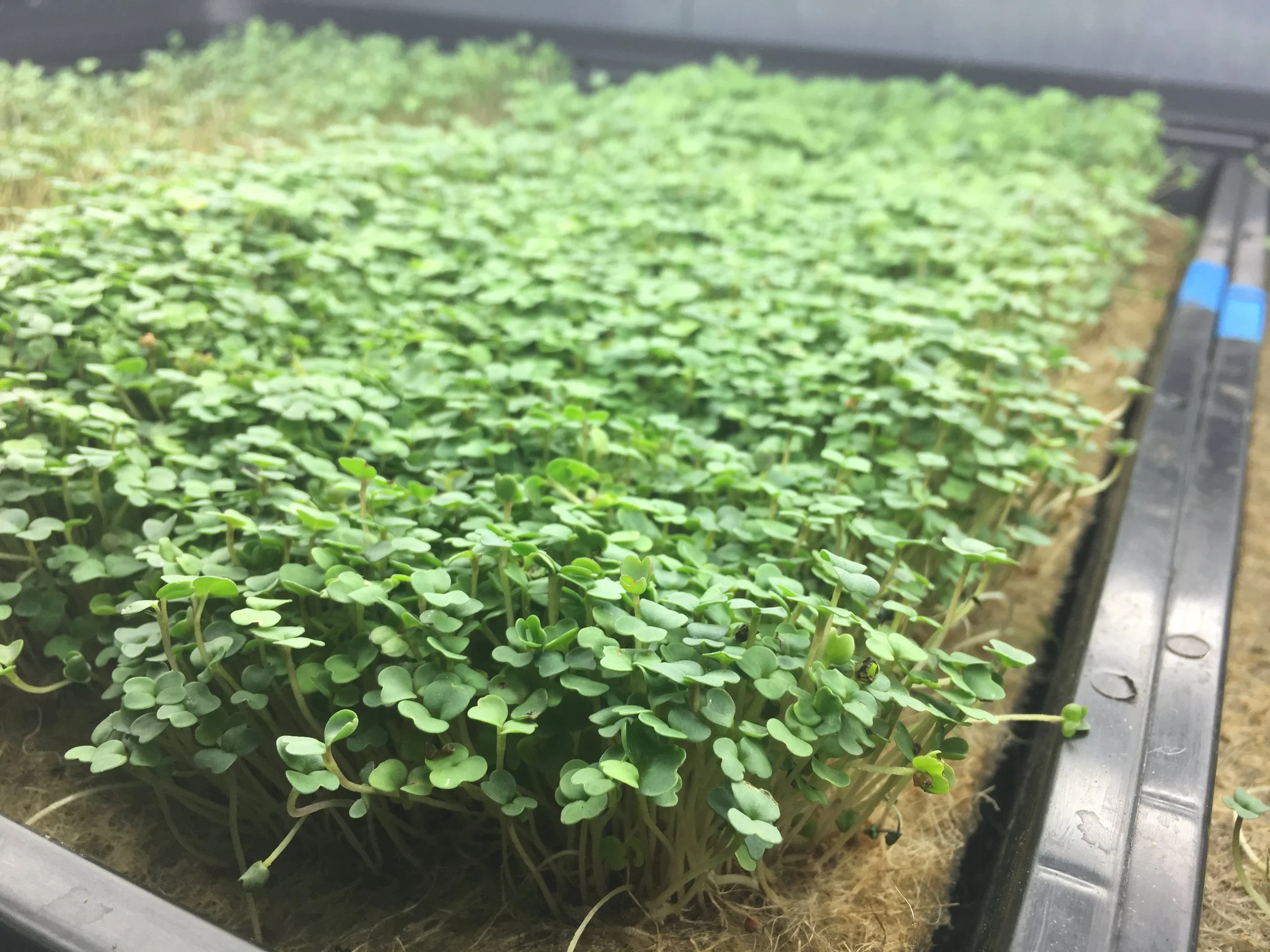

Rowdon began growing microgreens and herbs for himself, family members and friends. Then he started selling them at farmers’ markets about a year ago, and Olive Trunk Farms was born.

Microgreens are especially exciting, and Rowdon uses their vivid colors and bright flavors as selling points.

“Whatever I have at the market that day, I have samples for,” he said.

For customers who don’t want to eat full-grown kale or broccoli, Rowdon presents tiny shoots packed with nutrition and flavor, grown locally, harvested that day and fresh as can be.

One repeat customer, who has been purchasing Olive Trunk Farms sunflower shoots for the last year, said she had trouble maintaining healthy vitamin levels because of medication she takes. But after adding microgreens to her daily meals, her most recent blood work came back great even without supplements.

“[Microgreen sales are] going to be all about education and what you can do with microgreens,” Rowdon said. (Learn about microgreens for yourself here.)

He’s planning to take his greens to Earth Day Texas in Dallas in April, which is touted as the world’s largest Earth Day festival. More than 130,000 people attended last year’s three-day event to learn about the latest technologies and innovations shaping the world.

In June, Olive Trunk Farms will have a booth at the new Frisco Fresh Market, a daily market to be open year-round. The indoor/outdoor market will bring together farmers, foodies and chefs to 30 acres in central Texas to share their love for local produce, and Olive Trunk Farms figures to be right in the mix.

Rowdon is also looking ahead to moving Olive Trunk Farms from its current urban location to a spot with more space for indoor and outdoor growing, where he can power his operation using solar and wind. Already he’s working on ways to recycle and conserve water, such as running a dehumidifier with the microgreens and storing the excess water, which cuts into his water usage.

“My hope is to have an extremely small footprint, but yet very productive,” he said.

As a self-proclaimed technical person with a background working for a financial institution, Rowdon is still surprised about becoming an accidental farmer. But now he’s looking forward to working with his hands, digging into soil and building a business.

“Watching everything I grow from seed to harvest is just absolutely amazing,” he said. “It never ceases to amaze me watching all of this happen and the changes every single day. It’s never a dull moment and it’s never the same day twice,” he said.

He’s also enjoying being part of the growing community of local food producers bringing healthy produce to their friends and neighbors. “It’s healthy, it’s fresh, it’s local, and we want healthy people,” he said.

Interested In Becoming A Farmer Like Scott?

The Upstart Farmers are the modern farmers responsible for hundreds of indoor local farms around the world. Though from a variety of backgrounds and unexpected skill sets, the Upstart Farmers find themselves unified in their vision to feed healthy food to their communities and overcome the limits of traditional ag with innovative farms.

Upstart University trains new farmers to find markets, build farms, and gow incredible crops. Join Upstart U for a free week today to explore your potential as a farmer.

Detroit Turned Blighted Properties Into Urban Farming

Image: Pixabay

Recovery Park is providing a place for ex-offenders, recovering addicts and others with barriers to employment a chance to gain work experience.

Editor’s Note: As of February 2017, the project continues:

By Mary Velan

EfficientGov – Originally posted November 3, 2015

The city of Detroit is teaming up with RecoveryPark to transform a blighted 22-acre area on the city’s lower east side into a center of urban agriculture. The goal of the project is to provide a place for ex-offenders, recovering addicts and others with significant barriers to employment with an opportunity to gain valuable work experience.

The Project

The 60-acre project – which includes more than 35 acres (406 parcels) of city land – is designed to revitalized one of Detroit’s blighted neighborhoods by repurposing vacant land. The city is collaborating with RecoveryPark, a nonprofit organization working to create jobs for people who struggle to get hired.

“RecoveryPark isn’t just about transforming this land. It’s about transforming lives,” Mayor Duggan said. “The city of Detroit is proud to support the work Gary Wozniak and his team are doing to put this vacant land back to productive use and to help ex-offenders and others with barriers to employment rebuild their lives.”

The project is expected to employ 128 individuals within three years, 60 percent of who will be Detroit residents. Consistent with its mission, most of RecoveryPark’s workers will be ex-offenders, veterans and recovering addicts.

The RecoveryPark project wants to leverage Detroit’s underutilized assets while developing a for-profit food business – RecoveryPark Farms – in the local community. To help the project take root and grow, the city is allocated $15 million to the initiative.

Veterans, returning citizens, challenged workers, those in recovery and other marginalized citizens struggle daily for the ability to care for themselves and their families. Recovery Parkwill provide them the opportunity for a meaningful job, to earn a decent wage, own their own business and restore personal dignity, Wozniak said.

Under the $15 million project, which is expected to take five years to bring to fruition, RecoveryPark will replace blighted, vacant lots with dozens of massive greenhouses and hoop houses to grow produce. The fruits and vegetables grown in these facilities will be sold to local restaurants, retailers and wholesalers. Among the local businesses that already purchase produce from RecoveryPark Farms, includes the restaurants Cuisine and Wright & Co. (Detroit), Bacco Ristorante (Southfield) and Streetside Seafood and The Stand (Birmingham).

The City will lease the land to RecoveryPark for $105 per acre per year. In exchange, RecoveryPark must secure or demolish all vacant, blighted structures within its boundaries within the first year. Here are the terms of the deal:

- Within 120 days of possession, RecoveryPark is required to maintain the entirety of the leased footprint, mowing at least once every three weeks, and trimming trees. This remains continues for the entirety of the lease.

- Within 12 months of a signed term sheet, RecoveryPark will re-locate its Waterford, Michigan operations, to the City of Detroit’s negotiated footprint.

- Within 12 months of a signed term sheet 51% of employees will be Detroit based for the first 36 months. After 36 months, Detroit employment must increase to 60%.

- Within the first 12 months of a signed term sheet, RecoveryPark must secure or demolish any blighted / vacant structure within the boundaries. All demolitions will be in accordance with the City of Detroit’s demolition policy. Recovery Park must also present a plan to the City of Detroit for future use of all structures.

- Within 24 months of possession, RecoveryPark will operate at least 3 acres of greenhouses or hoop houses.

- Within 36 months of possession, RecoveryPark will operate at least 6 acres of greenhouses or hoop houses.

- Within 48 months of possession, RecoveryPark will operate at least 9 acres of greenhouses or hoop houses.

- Right of Reverter – The City of Detroit has the right to take back purchased land without greenhouses or hoop-houses if RecoveryPark defaults or does not meet terms.

“Commercial agriculture in Detroit is an important addition to Detroit’s expanding business portfolio,” sad Gary Wozniak, RecoveryPark CEO. “Mayor Duggan’s economic development team has move boldly and swiftly to align city resources with our company’s expansion needs.”

A New Type of Farm is Letting Us Grow 100 Times More Food

Farming has been a cornerstone of civilization for a long time — even before sewer systems. As humans have evolved, so has farming. Thanks to drones, CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, and a host of other innovations, we have come farther than we would have ever thought possible — including reaching new heights with vertical farming

A New Type of Farm is Letting Us Grow 100 Times More Food

Farming has been a cornerstone of civilization for a long time — even before sewer systems. As humans have evolved, so has farming. Thanks to drones, CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, and a host of other innovations, we have come farther than we would have ever thought possible — including reaching new heights with vertical farming.

The pinnacle of modern agriculture can be found in Kearney, New Jersey at Bowery farms. The farming company claims it has the capacity to grow 100 times more per square foot than average industrial farms. This might be because the vertical farm calibrates “synthetic” parameters for its produce. Thanks to indoor LEDs that mimic natural sunlight, and nutrient-rich waterbeds that are easy to stack from floor to ceiling, Bowery is able to grow over 80 different types of produce. Bowery will begin selling its organic produce, — including popular salad fixings such as kale and arugula — in NYC come March 6th, at around $3.99 per five-ounce package.

Click to View Full Infographic

THE FUTURE OF FARMING

What’s so remarkable about Bowery is that it underscores the next generation of agriculture. While traditional farming is unlikely to disappear anytime soon, vertical farming showcases increased automation, reduced emissions, and all-around reduced costs.

Automated machines efficiently move water around the plants using a proprietary software known as FarmOS. The unique operating system adapts to new data, adjusting environmental conditions to the warehouse. Trays are optimally stacked to the ceiling and crops are produced year round, increasing the overall efficiency of the process.

Traditional farming reduces soil productivity, wastes water, can foster the growth of pesticide-resistant insects, and increases levels of greenhouse gases. The practice itself is quickly becoming unsustainable, as there’s less land available for farming: since the 1970s, almost 30 million acres have been lost to urbanization.

While traditional agricultural methods may endure, it might be prudent to acknowledge the global and local benefits of vertical farming with so many new companies cropping up.

Garden Spaces Join The Sharing Economy

Alfrea, a company based in Linwood, New Jersey, is trying to extend the sharing economy to garden spaces.

Garden Spaces Join The Sharing Economy

Alfrea, a company based in Linwood, New Jersey, is trying to extend the sharing economy to garden spaces. The company was founded in 2016 as an online marketplace for renting land and finding farm hands for hire. Alfrea has since expanded to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Frederick, Maryland. The company has plans to expand nationwide. The website also has as a farmers’ market platform which allows farmers to sell produce at any time.

For those who live in cities and want to grow food, but lack land, Alfrea facilitates relationships with people who have available plots of land and those who have surplus crops can also sell them on the website. There are three types of Alfrea memberships to use these services, ranging from free to US$15 per month. Visitors to the site can also learn how to grow food in environmentally sustainable ways.

Food Tank had the opportunity to ask David Wagstaff, the company’s founder, about Alfrea’s past, present, and future in the sustainable food movement. This startup wants to give all people access to local, sustainably grown food.

Food Tank (FT): What motivated you to start Alfrea and advocate for locally grown, sustainable food?

David Wagstaff (DW): My parents own a 30-acre farm, but at 92 and 86 years old, it is hard for them to manage. As they have aged, I have taken a more active role in managing the farm, as well as their financial affairs and health decisions. I began to ponder my parents’ health, and in turn, my own. In early 2015, I immersed myself in research on how to have high-quality senior years. I read multiple books, watched several movies, met with various health experts, and even hired a fitness coach. All the research pointed to the importance of eating fruits and vegetables and reducing processed foods. The standard American diet has been tied to common health problems such as heart disease, dementia, Type-2 Diabetes, and some forms of cancer. Further, food purchased at grocery stores is often processed with high sugar, fat, and severely lacking vital phytonutrients.

Surprisingly, as I conducted research, I found that agriculture is linked to environmental degradation and climate change. Food production produces 14 percent of the world’s greenhouse gasses. Methane, a byproduct of many agricultural processes, has a heat trapping index 23-times higher than carbon dioxide and food travels an average of over 1,500 miles from farm to table.

During this time, I was trying to find people that would be willing to grow food on my parents’ land or lease out a portion of it, but it was harder than I thought. When I attempted to grow food in my own yard, the same problems persisted. Even when I turned to farmer’s markets, they were usually only open one day a week during the growing season and not always at convenient times.

Through my experiences, I discovered the sustainable food movement has no central hub for people to participate. Overall, the idea for Alfrea arose from my desire to eat healthily, protect the environment, and unify others who think like me.

FT: Has connecting gardeners and eaters with land, help, and food producers been easier or harder than anticipated?

DW: That’s an easy question—definitely more challenging. It takes a lot of effort to get the word out. With that said, part of the reason why Alfrea exists is that people express much excitement about this concept. Even before launching the actual website, I was in a grocery store, and one of the clerks overheard me discussing Alfrea. After that, the clerk came up to me and said he wanted to hug me in the middle of the grocery store because he was thrilled about Alfrea’s vision. That same week, a well-known environmentalist in California who rarely gets excited about many businesses was ecstatic about Alfrea. He has held positions as a board member of organizations such as Oceana, Marine Sanctuaries, and Green Peace. Both of these interactions gave me the courage to pursue the idea further.

FT: How does Alfrea plan to motivate more Americans to utilize its website’s garden share, farmers’ market, and other online community resources?

DW: In every way, we know how. Public relations, social media, content writers, community events, and attending farm conferences will all further our cause. We intend to mainly have a business-to-business approach, offering Alfrea as an amenity to apartment communities and as a corporate employee benefit.

All of us here are excited because Alfrea breaks into a substantial market. Right now, 56 million Americans live in apartment communities and currently don’t have immediate access to grow their own food. All of those people can use Alfrea to find land to grow food or find others in their community to grow food for them.

FT: What are some of the shared benefits for farmers and customers renting land, getting hired for service, or buying produce through Alfrea?

DW: The upside of utilizing Alfrea is massive. For consumers, Alfrea makes it easy to grow and eat local, sustainable food. Studies show that when people grow their own food, they tend to eat more fruits and vegetables, which is beneficial for their overall wellbeing.

Landowners also profit in a big way. As Airbnb, Inc. did for bedrooms, Alfrea intends to do for property, farmland, and even backyards. Our vision is simple; people can earn extra income by offering land to consumers. With traditional methods, the average annual rental rate for farmland is about US$150 a year per acre. Leveraging Alfrea, landowners can subdivide the land to share with multiple growers and potentially earn more than US$3,000 a year per acre! Plus, in some areas, people gain additional tax reductions for using their property for agricultural purposes.

For farm hands and skilled gardeners, Alfrea generates more opportunities for them to earn extra income. Alfrea intends to pay these laborers with an Uber-like program. While over one million people work on farms today, it is virtually impossible to find someone to help you grow crops in your backyard. Alfrea connects this fragmented market by connecting income-seeking gardeners with those who want fresh food grown on their property.

According to the National Farm Workers Ministry, the average income for crop workers ranges from US$10,000 to US$12,499. With Alfrea, these laborers can set their own rate and are asking anywhere between US$15 and US$20 an hour. In other words, people working independently through Alfrea can make more than double the national average for farm workers.

Lastly, farmers looking to sell food benefit financially and from a convenience standpoint. Farmers usually sell to wholesalers who earn 40 to 50 percent of the produce’s market price. However, Alfrea charges farmers only 12 percent. This reduction means farmers will see an income increase and reduced time spent contacting wholesalers. Plus, Alfrea’s website gives farmers the option to opt out of sitting at farmer’s markets for hours at a time.

FT: Does Alfrea plan to leverage Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), a popular way for consumers to buy local, seasonal food directly from a farmer, as the company expands across the country?

DW: Yes, we believe Alfrea can be a central hub to unite the fragmented CSA marketplace. In our experience, it is not easy to find extensive lists of local CSAs. Alfrea’s website makes geographic searching easy.

FT: What are some of Alfrea’s goals for the future, besides expanding to more cities?

DW: We would like to create a mobile app. Today, we are mobile-friendly but do not have an Android or Apple app for members to use.

We look forward to having more customers on the website. Analytics will help us learn how to serve their needs best. We have conducted some customer surveys and interviews, but as we grow, we want to make sure we are meeting the needs of farmers and consumers.

Another key strategy for us will be expanding access. We want to reach affluent consumers as well as consumers that may not be able to afford fresh foods and reach people who live in food deserts. Our team is still working out the details how to achieve this goal well, but all of us at Alfrea are optimistic about the future.

Meet Alfrea, The Social Enterprise That’s Like Airbnb For Community Gardening

Mar. 22, 2017 4:49 pm

Meet Alfrea, The Social Enterprise That’s Like Airbnb For Community Gardening

The online platform connects aspiring gardeners to open garden space as well as locally grown food in their communities.

By Julie Zeglen / STAFF

If you belong to one of the 40+ million households in the United States that gardens for food, you should probably know about Alfrea.

The year-old social enterprise based out of New Jersey connects aspiring gardeners to open garden space as well as locally grown food in their communities.

The online platform also connects people with excess resources to those seeking resources. Have a big ol’ backyard that would be perfect for someone else’s herb garden? Looking to sell that surplus of tomatoes your crop yielded last season? Alfrea can help you out.

“What Airbnb did for the bedroom, we’re trying to do for land,” Lindsey Ricker, Alfrea’s customer engagement manager, told us during her “Around the Corner” interview. Learn more below.

How Millennials Will Forever Change America’s Farmlands

How Millennials Will Forever Change America’s Farmlands

March 21, 2017 | 3:21 PM ET

As Americans increasingly reject cheap, processed food and embrace high-quality, responsibly-sourced nutrition, hyper-local farming is having a moment.

Tiny plots on rooftops and small backyards are popping up all across America, particularly in urban areas that have never been associated with food production. These micro-farms aren’t meant to earn a profit or feed vast numbers of people, but they reflect the Millennial generation’s desire to forge a direct connection with the food they consume.

These efforts are an admirable manifestation of the mantra to think globally and act locally, but they miss the opportunity that is going on right now: the economics of branded local farms have changed, and technology in agriculture has led to a renaissance of independent American farming. Whether this means farming the traditional acreage of the Heartland or adapting to cutting-edge indoor farming methods, the result is the same: demand for real food is far outstripping supply. Highly-educated, entrepreneurial, and socially conscious young people have a great opportunity to think seriously about agriculture as a career.

On the surface, this advice sounds dubious, given the well-documented, decades-long decline of independent farming in America. Between 2007 and 2012, the number of active farmers in America dropped by 100,000 and the number of new farmers fell by more than 20%. Ironically, however, the titanic, faceless factory farms are barely eking out a profit. That often means that an independent 100-acre farm growing high-demand crops can be far more profitable than a 10,000-acre commodity farm growing corn that may end up getting wasted as ethanol.

The key to reviving America’s agricultural economy is casting aside the sentimental images we associate with farming – starting with what a farmer looks like. In recent years, many of the same technologies that have revolutionized the consumer world have fundamentally altered and improved the way we farm. Drones, satellites, autonomous tractors and robotics are now all at home on farms. As a result, tomorrow’s farms won’t just be part of the agricultural sector, they’ll also be part of the tech sector – and tomorrow’s farmers will look a whole lot like the coders who populate Silicon Valley…except with better tans.

The next assumption about farming we need to cast aside is what a farm looks like and where it will be found. The vast planting fields of America’s heartland are going to change by adjusting to grow real food with 21st century technology, but tomorrow’s farms will also be vertical and in or near our urban centers. By 2050, 70% of the global population will live in cities. As both a social imperative and a practical matter, it makes sense to grow food near these cities, rather than to waste time and resources delivering products from hundreds or even thousands of miles away.

This will require innovative new technology that will create even more flexibility in the way we farm. With this in mind, I recently co-founded Square roots, a social enterprise that aims to accelerate urban farming by empowering thousands of young Americans to become real food entrepreneurs. We create campuses of climate-controlled, indoor hydroponic farms in the heart of our biggest cities and train entrepreneurs how to grow and sell their food year-round. After their training, these young entrepreneurial farmers, in partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, can qualify for larger loan programs as a next step to owning their own farm -- either soil-based or indoor. Whether they move on to their own farm or another business, they are prepared to build forward-thinking companies that will become profitable and create good jobs.

We are investing in this initiative not only because it’s the right thing to do, but also because we are confident that agriculture is poised for explosive growth, and that technology and the power of locally branded farms will be the keystone to success. Just ask self-described “AgTech nerds” like Sarah Mock, who is a leader in the growing movement of Millennial entrepreneurs who see an opportunity in farming to achieve the double bottom line – value and values – that is key to solving our planet’s toughest challenges.

Private enterprise will lead this revolution, but the federal government must help fuel its growth. The 2018 farm bill is a critical opportunity. This massive legislation, renegotiated by Congress every five years, establishes the blueprint and funding priorities across America’s agricultural sector. Last year, Democratic U.S. Senator Debbie Stabenow of Michigan introduced forward-looking legislation called the Urban Agriculture Act that would offer protections and loan options that are currently available only to traditional rural farmers. Ideas like these are essential.

A future in which our food is safer, healthier and environmentally sustainable can exist alongside one in which our agricultural economy grows and creates good jobs for millions of American workers. The technologies and business practices of modern farming is spreading rapidly. The opportunity for a young farmer has never been better – and it’s a future we can all get behind.

Kimbal Musk is co-founder of the Kitchen Community, a nonprofit that brings outdoor vegetable gardens to schoolyards and community spaces. He sits on the boards of Tesla, SpaceX and Chipotle Mexican Grill.

Vertical Farming, The Future of Crop Growth

Vertical Farming, The Future of Crop Growth

By Riana Soobadoo -

March 21, 2017

The future of farming is on the up and up, literally. With today’s society constantly changing, progressing, and evolving, everything that can be revolutionized will be. Now, with the emergence of vertical farms on the rise, it seems that the future of urban farming is here.

Vertical farming refers to when food is produced in vertically stacked layers, usually in a greenhouse or warehouse. These farms use indoor farming techniques and a variety of controlled environmental agriculture technology to control environmental factors in their favor. Such as the use of LED lights to substitute natural light that is missing indoors. Never having to be subjected to the elements, or worrying about what season it is, indoor farming allows for completely controlled growth of produce.

Because of its potential to transform agriculture globally, vertical farming is quickly becoming the next step forward in agricultural production. Although the produce cannot technically be labeled as organic, because it is not grown in soil, vertical farming processes are completely pesticide free, require no sun, and use 95% less water than traditionally field-grown crops. Additionally, due to the faster harvest time, crops grown through vertical farming produce a higher annual yield than those grown through traditional agriculture methods. The increased popularity in the sector has led to a surge in numbers of companies looking to make their mark on the industry.

The first of these, AreoFarms, is the one of the world’s largest indoor vertical farms. Based in Newark, New Jersey, USA, AreoFarms has been farming indoors since 2004. AreoFarms uses a technique called aeroponics. Aeroponics uses 40% less water than traditional hydroponic farming. It also utilizes smart LED technology to customize the amount of light used for each plant type. This energy efficient process has the potential to change the farming industry forever. Mark Oshima, a co-founder of AeroFarms explains that they use:

“IN-DEPTH GROWING ALGORITHMS WHERE WE FACTOR IN ALL ASPECTS FROM TYPE AND INTENSITY OF LIGHT TO NUTRIENTS TO ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS LIKE TEMPERATURE, HUMIDITY, AND CO2 LEVELS, AND WE CREATE THE PERFECT RECIPE FOR EACH VARIETY.”

Another emerging vertical farm is Bowery Farming. Based in New York, New York, USA, Bowery Farming first opened their doors in 2015 and has recently opened another location in New Jersey, USA, to increase their reach. Labeled as post-organic, Bowery’s products never travel more than 100 miles to guarantee freshness. Attracting increasing interest of new Investors, Bowery Farming has quickly become a big name in the vertical farming industry. They currently produce five leafy vegetables, including baby kale, lettuce, and arugula, and one type of herb, basil. These greens are non-GMO and do not need to be washed when taken home.

In Japan, the Pasona O2 building is yet another example of vertical farming; with 6 rooms of farms, 100,000 square meters, and growing over 100 different types of produce, this farm employs young men and woman who are struggling to find jobs or have an interest in farming. The company advocates the individual development of these men and woman, passionate about seeing them succeed in their industry. Each room at Pasona O2 houses something different: room 1 houses a flower field, room 2 is a herb field, room 3 a rice field, room 4 a fruit and vegetable field, room 5 is vegetables, and room 6 is for lettuce and the seeding room. Each room is set to the proper environmental specifications needed to grow and sustain the crops.

Unfortunately, as revolutionary as vertical farming is, the start-up costs are astronomical, which can be a problem for companies trying to expand. One company in particular, the Atlanta based PondPonics, was able to get their productions costs down lower than anyone else. Unfortunately, when offered a $25 million dollar annual contact with Kroger they could not get the funds to build the necessary facilities to grow in such volumes. Ultimately, PodPonics was forced to close their doors as the running costs became too high.

This is not the case for every company. As time moves forward we will begin to see a shift in the attitudes of investors, and interest in vertical farming will continue to grow. The future of agriculture is looking greener and greener. With vertical farming on the rise, we can expect to see a change in the industry unlike ever before.

Urban Farmers Grow Veggies In Freight Containers

Urban Farmers Grow Veggies In Freight Containers

Kara Carlson, The Arizona Republic

9:10 a.m. ET March 21, 2017

(Photo: Kara Carlson/Arizona Republic)

PHOENIX -- The future of urban agriculture might require farmers to think inside the box.

Farmers here are growing vegetables here in converted freight shipping containers equipped with the latest hydroponics and automated systems equipment. They are provided by a Boston-based firm, Freight Farm.

“The farm of the future,” said Mark Norton of Phoenix, whose Picked Fresh Farms grows kale and lettuce in one of the containers.

Freight Farms started in 2010 with the goal of bringing viable, space-efficient farming techniques to all climates and skill levels year-round. It recently expanded to Arizona.

The cars are not cheap. Each container -- the kind commonly seen on trains, trucks or ships -- costs $85,000, not including shipping. Freight Farms calculates annual profit for each container to be an average of $39,000 annually.

Caroline Katsiroubas, marketing director for Freight Farms, said urban areas are the most popular destinations for its equipment and expansion has been nationwide.

Norton of Picked Fresh Farms isn’t what most people would picture as a farmer. The closest anyone has come to farming in his family was his grandfather, who farmed as a child, but that didn’t deter Norton.

“If I can get a better environment, better food, help people with their food, and still help people with their health, that’s where it all fits,” Norton said. “It aligns with my core values.”

He recently had one of his first successful harvests of lettuce, but he’s already looking to the future, with a 10-year goal to expand to 10 containers.

Mark Norton of Picked Fresh Farms closes the container where he grows kale and lettuce.

(Photo: Kara Carlson, Arizona Republic)

“I was just going to do it as like a hobby, but these things, there’s a need and nobody's really filling it,” Norton said.

Norton is one of only two freight farmers in Arizona, but the thought of competition doesn’t bother him.

“I think there’s enough space to have a bunch of these,” he said.

Heather Szymura, who co-owns Twisted Infusions Farms with her husband Brian, agreed. The Glendale, Ariz., company was the first in the Grand Canyon State to freight farm, and Szymura said she wants to see more of the farms come to Arizona because there is no way her company alone can feed everybody.

She has been urban farming for 12 years, with gardens and walls of plants in both her front and back yards. The latest edition, the 7½-ton container is nestled on the side of her house.

In a year, the 320-square-foot container can produce the equivalent of a three-acre farm. It also saves water, using five to 10 gallons of water a day, 95% less than traditional farms, Freight Farms said. The water is delivered in a nutrient-rich system based on hydroponics, a method to grow plants without soil.

Growing the leafy greens inside seem unnatural, but the farmers maintain not only is the process natural, it’s optimal.

Norton prides himself in using no GMOs, no pesticides and no herbicides. The environment is controlled, so there’s no reason for it. The container can put out 50 to 100 pounds of lettuce a week.

The farm uses strips of red and blue lights, the spectrums used in photosynthesis, to make it as efficient as possible. Machines automatically dose the plants with water and nutrients. All notifications lead back to an app on phones, which allows farmers to track everything from seeding to harvesting. On average the process takes about seven weeks and, depending on the environment, this can actually be almost twice as fast as a traditional farm, Freight Farms said.

This optimization allows for a greater variety than a grocery store might offer. Katsiroubas of Freight Farms said it allows farmers to focus on the characteristics they want because of the efficiency.

This is an aspect of farming the Szymuras enjoy, and it’s allowed them to be more experimental and try different plants and techniques.

Kale growing inside a temperature-, water- and light-controlled freight car makes the plant sweeter, and softer, Norton said. He said it’s also healthier because it’s traveling less distance and keeping produce local.

The ability to support local is part of what appealed to the Szymuras. They get as much of their farming products and water supplies as possible from local suppliers.

The produce is all sold locally, and the container allows them to easily educate people on urban farming and the seed to harvest process.

Szymura especially enjoys the ability to watch the process from start to finish. Seeding starts in trays kept at optimal light and temperature and then moves to the towers, which contain rows and surround more LED lights.

It’s something her clients like seeing as well. Many of Twisted Infusion’s customers are chefs and caters who come in to see what will be harvested next and appreciate being able to even pick the produce themselves. The caters can have their produce from farm to table in the same day.

The system, and the ability to switch crops easily, also allows chefs to put in specific orders and know it will be ready when they need it.

Norton is focused more on restaurants and individuals through members of Community Supported Agriculture, a subscription-like system that lets customers buy shares of local food. Norton expects most of Picked Fresh Farms' business to come from this, but he also has started to reach out to restaurants with samples of his product.

Plant Based Foods Association Celebrates One-Year Anniversary at Expo West

Plant Based Foods Association Celebrates One-Year Anniversary at Expo West

March 18, 2017/0 Comments/in Miscellaneous, News /by Michele Simon

Since our launch at Natural Products Expo West 2016, we have been amplifying our collective voice for our member companies. Our return to Natural Products Expo West in 2017 marked our one-year anniversary and gave us the opportunity to look back on our successes and spend some quality time with our members.

Panel: Why Plant Based Foods Are Good for Your Business & the Planet

We loved putting together this panel featuring the best in our industry: Mo George-Payette, CEO of Mother’s Market, Lisa Feria, CEO of Stray Dog Capital, Aubry Walch, co-founder of the Herbivorous Butcher and our very own Executive Director Michele Simon as moderator.

Simon started things off by comparing the environmental impacts of plant-based foods with their animal-based counterparts to drive home the point that switching to more plant-based foods is an effective way to protect our planet.

Simon then presented recent data from SPINS to illustrate the rising sales of plant-based foods, which top total revenues of $5 billion annually. She finished with a discussion of the Dairy Pride Act and our strategic response to this attack on our members.

Mo George-Payette of Mother’s Market reflected on the rise of plant-based options throughout her years in the natural foods industry. “We can remember back to when it was only tofu,” she remarked. She also noted the importance of product placement for plant-based foods, and the rise of flexitarians in boosting sales.

Aubry Walch, co-founder of The Herbivorous Butcher, (PBFA member) discussed her company’s decision to not “dance around terms” and instead use the names consumers are used to seeing in an ordinary butcher shop. This approach is a natural extension of their effort “to bridge a gap between omnivores and the plant-based world.”

Lisa Feria, CEO of Stray Dog Capital, (PBFA sponsor) discussed how fueling companies and services that promote plant-based diets is an effective way to help animals. Feria also highlighted the importance of supporting women in the business world, suggesting that we “pull up as we go up.”

You can watch this panel on The Herbivorous Butcher’s Facebook page here.

Panel: Eating Animals

On Saturday, our ED Michele Simon participated in the Eating Animals panel, featuring David Bronner, CEO of Dr. Bronner’s, (PBFA sponsor) Aaron Gross, CEO of Farm Forward, and Leah Garcés, director of Compassion in World Farming, as moderator. Simon discussed the challenges faced by plant-based companies when competing with subsidized animal agriculture and emphasized how everyone can support plant-based companies by voicing their opinions to their political representatives.

You can watch Michele Simon’s segment of this panel on PBFA’s Facebook page here.

Panel: Eating Animals

On Saturday, as the trade show floor came to a close, it was time to celebrate all we have accomplished in this past year. An astounding 400 of our plant-based allies attended our celebration, creating a palpable energy in the room as they chatted and snacked on supreme pizza and strawberry cheesecake generously donated by founding board member Daiya Foods. We are also grateful for our additional generous event sponsors who made our reception possible: Follow Your Heart, Miyoko’s Kitchen, Tofurky, Upton’s Naturals, PlantBased Solutions, Nutpods, and Natural/Specialty Sales.

PBFA board president and Tofurky CEO Jaime Athos introduced our ED Michele Simon who addressed the bustling crowd. Simon drew attention to PBFA’s successes over the past year. Growing from 22 founding members to 80 members and 55 affiliates in PBFA’s first year alone shows the excitement within our industry. “The energy in this room shows that we are stronger together,” said Simon. “It truly takes a plant-based village to make this all happen.”

You can watch Simon’s speech on PBFA’s Facebook page here, and view our photos from Expo West on PBFA’s Facebook page here.

Jill Ettinger of Organic Authority covered the explosion (and our reception!) of plant-based foods in her article: “Natural Products Expo Breaks Attendance Records as Plant-Based Foods Chart New Course for Industry.”

We had a great time at Expo West and look forward to returning again next year.

Panelists, from left to right: Michele Simon, Mo George-Payette, Aubry Walch, and Lisa Feria.

PBFA board member Miyoko Schinner, founder and CEO of Miyoko’s Kitchen, chats with guests.

Urban Agriculture Director Brings Fresh Produce To Those In Need

Urban Agriculture Director Brings Fresh Produce To Those In Need

Battling food deserts with community gardens, farmers markets.

By Andrew Alexander - For the AJC

Posted: 5:16 p.m. Thursday, March 16, 2017

At first glance, the urban Atlanta neighborhood of Washington Park doesn’t seem a likely place for an organic farm. But at the corner of Lawton Street and Westview Drive in west Atlanta, the non-profit organization Truly Living Well’s new Collegetown Garden brims with organic cabbages, kale, turnips, beets, carrots and more, all thriving in tidy rows of planter boxes. Pear, plum and apple trees blossom radiantly in the early spring sun, and a busy hive of honeybees buzzes away nearby.

“This can really be a lighthouse for nutrition for this neighborhood,” says Mario Cambardella, the City of Atlanta’s first director of urban agriculture. Some might zero in on the signs of urban neglect and decay just outside the garden gates, but Cambardella is quick to point out the historic homes, the nearby elementary school and, on a street-facing the end of Truly Living Well’s new garden, the site of a future farmers’ market for the food being grown there.

“This is really building the local food economy. Urban agriculture can really transform a community.”

Cambardella was hired by the Mayor’s Office of Sustainability in 2015 to help guide projects like the Collegetown Garden to success. In the new position, Cambardella is responsible for a wide range of activities related to urban agriculture in the city, including agricultural policy development. He cultivates partnerships with local non-profits like Truly Living Well and also assists individuals and organizations in navigating the often byzantine process of permitting and zoning related to starting their urban agriculture projects.

“Urban agriculture is relatively new to this generation of constituents, so having a point person for all these different issues is a much-needed service,” he says. “People have been asking for help getting through the process. I like to think I’m creating the most efficient means to get that community garden growing as fast as it can.”

His daily work can encompass anything from helping an individual place a planned garden’s water meter to permitting a future farmers’ market.

“We want to empower what constituents do,” he says. “It’s one of the aspects of my job I love. It’s not about what program I can start, it’s about the programs I can help.”

For Cambardella, gardening and community are both part of a long family tradition. Cambardella’s grandfather hails from Italy in a small farming community south of Naples. As Cambardella tells it, his grandfather’s first attempt to come to the United States — travelling independently and working in the coal mines of Pennsylvania — was a disaster. His grandfather went back to his home country after just nine months, but returned a few years later with a new wife and other families from his village and settled in Brooklyn in the 1930s. Together, the community successfully created small gardens and relied on each other, much as they had in Italy.

“My father still remembers having to turn the compost and cover the fruit trees in winter to keep them warm,” Cambardella says. “They made it through some of the roughest times in America. When you have this network supporting each other, it can show what sustainability really means.”

His mother’s side of the family comes from Texas and likewise honored a long tradition of living off the land. “That heritage got passed down to me,” he says. “I always had it in me to scratch a little earth and see if I could grow something.”

Cambardella grew up in Sandy Springs and attended Riverwood High School. He majored in Landscape Architecture at the University of Georgia and then went on to get master’s degrees in landscape architecture and environmental planning and design at UGA, as well. In 2012, he co-founded an Atlanta-based business, Urban Agriculture Inc., that provides planning, design and construction management of food-producing landscapes for commercial, municipal and residential clients. He signed on as the City of Atlanta’s first director of urban agriculture in December 2015, and currently lives in Chamblee with Lindsey, his wife of four years.

Many of the things he’s been working on speak to Atlanta’s potential to lead the way in the realm of innovative urban agriculture. Some of his pet projects include helping Georgia Power explore the idea of using the land under power-line easements for high-level urban agriculture and developing a potential food forest in southeast Atlanta on the site of a former farm now surrounded by urban development.

One goal is to transform Atlanta’s urban food deserts by bringing local, healthy food within a half-mile of 75 percent of all residents by 2020. “I have to show up everyday and give 110 percent,” says Cambardella. “I have to be looking toward 2020. That’s a goal worthy of working toward.”

And in the end, for him, urban agriculture is about far more than just food. “If we can fuel this type of activity, we can really build up points of access,” he says. “And it’s about more than just lettuce. It’s the eyes on the street, it’s the kids coming to play and learn, it’s all these forces for good that create growth and cultural understanding. What’s coming out of the ground has so much value.”

Five of Brooklyn's Most Innovative Urban Farms

It may be a cliché to lament the loss of farms in New York City. These five Brooklyn-based urban farms, mostly co-founded by former Wall Street professionals, are using the most creative and entrepreneurial techniques, from aquaponics to vertical growing, to bring fresh, locally grown produce to New Yorkers.

FIVE OF BROOKLYN'S MOST INNOVATIVE URBAN FARMS

New YorkSustainability Mar 16, 2017 Kouichi Shirayanagi, Bisnow

It may be a cliché to lament the loss of farms in New York City. These five Brooklyn-based urban farms, mostly co-founded by former Wall Street professionals, are using the most creative and entrepreneurial techniques, from aquaponics to vertical growing, to bring fresh, locally grown produce to New Yorkers. Beyond the health benefits of eating fresher produce, locally grown food benefits the environment by cutting out the need to transport and preserve perishable fruits and vegetables, which can take more than a week to get from the farm to a New York City dinner plate.

Gotham Greens Location: 810 Humboldt St., Greenpoint Co-founded in 2009 by a sustainable development manager and an ex-JP Morgan Chase private equity fund manager, Gotham Greens produces organic leafy greens, lettuces and tomatoes from the tops of buildings in Greenpoint and Gowanus as well as in Hollis, Queens. Early in the business, partners Viraj Puri and Eric Haley developed a relationship with Whole Foods to distribute their produce. In 2013, Gotham Greens built a 20K SF greenhouse on the roof of the Whole Foods store in Gowanus. The project marked the first time a greenhouse integrated with a major grocery store. The first Gotham Greens greenhouse, built in 2009 in Greenpoint, is 15K SF and produces 100,000 pounds of produce a year.

Red Hook Community Farm Location: 560 Columbia St. and 30 Wolcott St., Red Hook Managed by environmental educator Saara Nafici, Red Hook Community Farm produces more than 20,000 pounds of produce a year from two Brooklyn sites. The 120K SF farm on Columbia Street uses ground compost two-feet deep to create a diverse environment of microorganisms and insects that nourish the produce. Red Hook Community Farm also built a 48K SF site on Wolcott Street in collaboration with the New York Housing Authority. Members of Green City Force, an AmeriCorps program, maintain the farm. The organization maintains a Saturday farmers market at the Columbia Street site between June and November to sell the farm's produce.

Eagle Street Rooftop Farm Location: 44 Eagle St., Greenpoint Managed by educator and journalist Annie Novak, the Eagle Street Rooftop Farm occupies 6K SF on top of a warehouse in Greenpoint. The farm grows a wide variety of vegetables, spices and greens, including hot peppers, eggplants, sage, parsley, cilantro and dill. Novak sells produce from the farm at an on-site Sunday farmers market.

Brooklyn Grange Location: McGolrick Park, Greenpoint Co-founded by former E*Trade Financial consultant Ben Flanner and longtime sustainable food advocate Gwen Schantz, Brooklyn Grange grows over 50,000 pounds of produce per year in over 87K SF on two rooftops, one in Brooklyn and one in Queens. The Brooklyn Grange education program brings 17,000 New York City youths each season for tours through their farms. The organization is supported by a produce share program in which members subscribe to weekly deliveries of fresh produce. The farm grows a variety of produce, including from salad greens, mix herbs, eggplants, chard, carrots, peppers and flowers.

Square Roots Location: 630 Flushing Ave., Sumner Houses Square Roots operates vertical farms from shipping containers. Specializing in greens and herbs, the indoor growing process allows for year-round growing using 80% less water from traditional outdoor farms. Like Brooklyn Grange, Square Roots is funded by a food-share program where members can buy in $7, $15 and $35 per week packages. The working collective also has an active, year-round events business.

SXSW Just Showcased The First-Ever Traveling Indoor Farm

SXSW Just Showcased The First-Ever Traveling Indoor Farm

March 16, 2017

Each year some of the most imaginative and innovative minds from all over the world gather at South by Southwest (SXSW) in Austin, Texas. The first-ever traveling indoor farm was presented this week.

The SXSW trade show offers exhibitions that range from promising startups to well-established global corporations, affiliate KEYE reported. Companies from across the world descend on Austin to display their products in hopes of catching the eye of an investor, networking or just showing what they have to offer.

Local Roots has created a traveling indoor farm that uses a scalable, proprietary growing system that promises to provide "predictable production and quality."

"We have a circulating irrigation system and we recapture all of the water that flows through the system to reduce our water consumption down just what the plant needs to be able to grow," said founder and CEO of Local Roots Eric Ellestad.

Ellestad said his company is proof that technology is needed everywhere.

"The root zone lives down in the irrigation system drinking its nutrient-filled water day in and day out," Ellestad said.

Local Roots compares their technique almost the same as outdoor farming since they are using the same seeds, nutrients, minerals and light to activate photosynthesis. The major differences are that the light is supported by LED lights instead of the sun. The soil has also been removed in order for plants to be able to collect dissolved nutrients in the water.

The California-based company promises that their plants grow twice as fast and plants grow with much higher nutrient densities.

This Bronx Distribution Hub Could Help Local Farmers Reach More Tables

This Bronx Distribution Hub Could Help Local Farmers Reach More Tables

GrowNYC's Marcel Van Ooyen is working to launch a 75,000-square-foot food distribution hub in Hunts Point

By Cara Eisenpress

Van Ooyen wants to serve local and midsize farmers in the state.

The popularity of farm-to-table eating has created demand in the city for a local farmers’ wholesale market. Gov. Andrew Cuomo in August committed $20 million to fund a 75,000-square-foot food-distribution hub in Hunts Point and chose GrowNYC to develop and operate it. The 40-year-old nonprofit runs farmers’ markets and community gardens as well as recycling, composting and education programs. The Bronx distribution hub is the biggest project Marcel Van Ooyen has taken on in his 10 years as GrowNYC’s head. He said he hopes it will open in early 2019.

What's the purpose of the hub, and how will it work?

The hub will source, aggregate and distribute locally grown produce to food-access programs and like-minded restaurants and retail outlets. We anticipate well over 100 farmers will benefit. Farmers who grow for the wholesale markets will deliver large quantities to us. We'll break it up and distribute to public and private buyers. We'll have additional space for farmers to store food, and eventually light processing.

Why build it?

Ninety-eight percent of what we eat comes through wholesale channels. The current hub for local farmers is only 5,000 square feet, so we will replace it to serve more of them.

The limiting factors to supporting local, midsize farmers are having the infrastructure for them to drop produce off and us to deliver it and to be able to pay them a real return on what they're growing. It's difficult for these farmers to compete with the huge farms in California.

So how do you pay farmers a real return?

We let them set the price. By being a nonprofit and not trying to make any money other than [to cover] our operating costs, GrowNYC is able to even the playing field.

How do you get fresh, local food to underserved New Yorkers?

We worked with the Department of Health to create Healthy Bucks, a food stamp incentive program that has become a national model. Through our programs, like Youthmarket, we can distribute in areas that haven't been traditionally served. The same kale that is going into Gramercy Tavern is at a farm stand run by teens in Brownsville, Brooklyn, on the same day.

Is the obsession with farm-to-table more than a trend?

It's the last frontier for environmentalism. We spend millions of dollars protecting the watershed around New York City and building the infrastructure to keep water clean and safe and deliver it to everyone at a reasonable price. We spend a lot of time regulating the air. But food is something we've left to private industry.

Is there enough local food to serve restaurants that say their food is local?

Consumers have to be skeptical and ask. We need to make sure that people are living up to their promises. With more local wholesale, the issue of "faux-cal" may disappear because there's access to that product on a consistent basis.

What does the White House's environmental position mean for the city?

Cities have been the innovators in fighting global climate change. As a citywide organization, we provide an outlet to create change in communities even if they can't get it on a federal level. You're not going to be worried about Trump's tweets while you're shopping in a Greenmarket. Hopefully, you're thinking good thoughts.

Van Ooyen wants to serve local and midsize farmers in the state

Mother Nature Gives Indoor Farms A Boost

Mother Nature Gives Indoor Farms A Boost

By Tom Karst March 14, 2017 | 10:00 am EDT

Tom Karst, national editor

There are times that Mother Nature is just too darn unpredictable.

When everything goes without a hitch, the U.S. typically has an abundant supply of vegetables. But throw in rainy weather, delays that move back planting and harvesting, and all of a sudden you have a case of panicky buyers who are keen to look for more predictable and nearby sources of supply.

Retailers and consumers in the United Kingdom in February suffered a shock when rains in Spain caused some stores to ration their supply of greens. Some California companies saw an opportunity and shipped lettuce to the U.K.

Now it’s California facing rain-related production problems. The Packer has covered the gaps in vegetable supply in California, and various marketers predict it will get worse before it gets better. The rains that brought relief to the Golden State could give buyers a roller coaster ride later this spring.

In the context of these issues, we are reminded of the conviction that one region’s disaster is an opportunity for someone else.

The Packer’s Ashley Nickle covers the issue this week in a story that reports indoor farms are seeing increased demand as weather-related production issues in Arizona and California have affected the supply of leafy greens.

Nickle reports New York, N.Y.-based BrightFarms, which has greenhouses in Illinois, Virginia and Pennsylvania, has seen retail orders rise in recent weeks.