Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Buying The Farm

Buying The Farm

Staff Writer, The Ringer

The future of agriculture is happening in cities. After years of experimentation, Silicon Valley may finally be making urban farming viable. But will residents be able to afford the crop?

The town of Kearny, New Jersey, is a small industrial desert, populated by warehouses, factories, and twisting freeways filled with hulking cargo trucks. Its natureless landscape and the decrepit remains of 19th-century textile factories make it so uninviting that it was occasionally used as a filming location for HBO’s The Sopranos. In other words, it’s the kind of place where you’d expect to see a mobster toss a dead body into a dumpster — it is not where you’d expect to see a nice man in plaid harvesting baby kale. But the day I visited a warehouse on a concrete lot in Kearny, I watched Irving Fain, the CEO of a new urban farm named Bowery, do just that.

“Are you a kale fan?” Fain asked me excitedly.

I met the 37-year-old Fain, who’s tall with messy brown hair and an enthusiastic grin, in a tidy waiting room at the back of the building. He was wearing a flannel shirt, jeans, and comfortable tennis shoes. But that was not what he wore when we headed into the adjacent room. Instead, we zipped our bodies into papery hazmat suits, tucked our hair into nets, and placed protective booties over our shoes.

The moment we walked into the spotless, brightly lit room, occupied with rows of tall remote-controlled towers that contained trays of leafy greens under LED lights, Fain morphed into a giddy, considerably healthier Willy Wonka. A single attendant had ordered the farm’s autonomous robotic forklifts to lower the portable crops onto conveyor belts and send them toward us. We walked up to their landing table, and with a pair of mini scissors, Fain began snipping leaf after leaf for me to taste. First came the arugula (which he called “crisp and peppery”), then the purple bok choy (“It’s, like, amazingly good”), then the spicy mustard greens that the executive chef at the Manhattan restaurant Craft had specifically requested (the owner, Top Chef star Tom Colicchio, is an investor in Bowery). Each sample was a pristine vision of plant life, with zero sign of the unsightly deformities that come from bugs and dirt — the risks of being grown outdoors.

And then there was the kale.

“One of the compliments our kale gets a lot is: ‘Man, I never liked kale, but I had to like kale, and I actually really like your kale,’” Fain said.

A begrudging kale consumer myself, I took a skeptical bite and was pleasantly surprised. I tasted no hints of the bitter chalkiness associated with the superfood. It was light and sweet and unusually fresh compared with the produce at my local Key Food. All this, without ever coming into contact with the outside world.

But the kale wasn’t delicious simply because it was grown without pesticides, or because Fain, who previously ran a customer loyalty software startup, has a green thumb. The kale was delicious because, in addition to maintaining a mostly autonomous farming system, Bowery uses proprietary software that collects data points about what influences a plant’s health, growth rate, yield, and factors that affect its flavor. According to Fain, it analyzes the information in real time, and automatically pushes out changes to the treatments of crops as it sees fit. I liked the kale in part because its growing conditions were dictated to a microscopic degree by machine-learning software that Fain lovingly calls “FarmOS.”

(Bowery)

Bowery is the latest of a handful of urban farm startups attempting to reinvent how people, specifically city dwellers, get their food. In February, the startup announced that it had raised a healthy $7.5 million from a handful of venture funds, joining the likes of companies like BrightFarms, AeroFarms, and Square Roots that have caught the eye of tech investment firms over the past few years. The premise of these companies, as they tell it, is simple: America’s current farming system is wrought with inefficiencies. Climate change is threatening our ability to efficiently grow crops. And, on top of that, food must be hauled great distances to reach highly-populated city centers. In the process, taste, quality, and shelf life are sacrificed. By growing plants in warehouses, shipping containers, and city-adjacent greenhouses, these next-gen farmers claim they are able to eliminate the threat of unpredictable weather, waste less water, reduce transportation costs, and — most enticingly — stop basil from wilting within 30 seconds of landing in the refrigerator. And even if agricultural experts warn that their farming models might not be enough to ameliorate the world’s food-shortage issues, that has not stopped these companies from adding a utopian flair to their marketing efforts. The same way that Soylent has floated its product as a way to end world hunger, these farming startups are angling to be seen as the solution to our collapsing agricultural system.

Aside from the chance to, as one farmer I spoke to put it, “disrupt the industrial food system,” supporting urban farming is especially appealing to Silicon Valley investors. As mega tech entrepreneurs have colonized Northern California over the past few decades, they have internalized elements of its collective environmental conscience and crunchy farm-to-table culture. (After all, it’s hard to snag a reservation at Chez Panisse without first learning who the hell Alice Waters is.) When climate change skeptics questioned Tim Cook’s 2014 pledge that Apple would invest in renewable energy, the typically mild-mannered CEO reportedly became “visibly angry” and told them to sell their shares. Cafeterias at corporations like Google have long offered organic, hormone-free meals made with ingredients sourced from local farms. In 2011, Mark Zuckerberg even announced a new “personal challenge” to eat meat only from animals he’d killed himself. Tech industry titans are so enamored with healthy, tasty, ethical food, that they once invested $120 million to develop a $700 machine that makes an eight-ounce glass of organic juice. Silicon Valley’s decision to invest in urban farming startups is just about as inevitable as Steve Wozniakchecking in at the Outback Steakhouse in Cupertino on a weeknight. It comes with the territory.

(Bowery)

These new-age agricultural businesses have found it helpful to update the language of an ancient industry to emphasize their innovative approach, and better cater to their ideal audience. Along with naming his facility’s operating system “FarmOS,” Fain has also coined the term “post-organic” to describe Bowery’s completely chemical-free produce and elevate its cachet in the competitive world of gourmet salad. The difference, as he explains it, is that the United States Department of Agriculture technically allows organic farmers to use certain pesticides and organic produce is sometimes exposed to chemicals spread from nearby farms, while his product is completely “pure and clean.” Last year, Elon Musk’s brother Kimbal lifted the startup incubator model popularized by Y Combinator and applied it to farming, launching the Brooklyn-based company Square Roots. (In his obligatory Medium post announcing the endeavor, he cited evidence that microwave sales were declining and declared that “Food is the new internet.”)

Square Roots’ premise is vaguely reminiscent of the contest described in the opening credits of America’s Next Top Model: 10 individual farmers are given their own app-controlled, 320-square-foot steel shipping container to grow plants in for a year. In what the company’s cofounder and CEO Tobias Peggs has dubbed a “farmer-to-desk” model, individuals can receive weekly deliveries to their workplace in the size of a “nanobite” (one bag), “megabite” (three bags), or a “terabite” (seven bags) from individual farmers in the program. In the end the farmers are set free to start their own enterprises. Even AeroFarms, a New Jersey farm startup that waters its plants with patented aeroponic misting apparatus and is the most established U.S. company of its kind, describes its progress in terms of traditional software release iterations (i.e. “AeroFarms 2.0”).

Not only have these startups modernized agricultural terminology, their marketing teams have also cozied up to the altruistic image of America’s modern-day agriculture movement. The history of urban farming in the United States has always been inextricably linked to the availability of food, and a community’s ability to grow that food itself. The earliest modern American urban farms were plotted in 1893, amid an economic recession. To aid the swaths of industrial workers who had recently lost their jobs, the mayor of Detroit, Hazen Pingree, launched an initiative that provided unemployed residents with vacant lots, materials, and instructions that they could use to establish their own potato farms. “Pingree’s Potato Patches,” as they were known, were so helpful in feeding needy residents that both Boston and San Francisco modeled programs after them until the economy improved. Similar programs were recycled in the 1930s, during the Great Depression.

By the early 20th century, programs similar to Pingree’s began popping up at schools in urban areas, stoked by urban reformers who worried that kids would be ruined by growing up in industrial environments. Schools in cities like Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia taught their students how to plant everything from sugar beets to rye as a way to impart individual responsibility, civic virtue, and — as one New York urban farm advocate from the time put it — “the love of nature by opening to their minds the little we know of her mysteries, more wonderful than any fairy tale.”

(Square Roots)

It wasn’t until the U.S.’s involvement in World War I began in 1917 that the federal government began pushing Americans to farm in the name of patriotism. In order to meet the export demands of food-starved Europe, the U.S. established the National War Garden Commission, a national organization that asked citizens to become “soldiers of the soil” by growing their own food. Posters encouraging agricultural action depicted gallant men and women working in fields, sometimes alongside anthropomorphic American-flag-toting potatoes. The campaign worked: The same year the government announced the program, it counted approximately 3.5 million war gardens.

Larger-scale agriculture had helped food supply become more reliable by 1939, but that didn’t keep the federal government from repurposing the movement at the beginning of World War II. The government’s updated campaign saw these “victory gardens” as a source of health and morale, even if the increasing growth of suburbs meant that people were planting them in the privacy of their backyards. Once again, patriotism took hold, and an estimated 18–20 million families had planted victory gardens by 1944, according to the Smithsonian’s digital archive of American gardening history.

In the 1960s and 1970s, activists began jump-starting their own urban-greening movements to ameliorate food deserts, benefit poor communities whose city neighborhoods were littered with vacant land, and educate locals on the benefits of healthful, seasonal eating. In 1969, a handful of UC Berkeley students and locals aimed to claim an empty lot owned by the university and transform it into what’s now known as the People’s Park. (“The University had no right to create ugliness as a way of life,” read an article in the alt newspaper the Berkeley Barb.) Organizers managed to mobilize thousands of people to convert the land into a green oasis, which conservative politicians and UC officials then attempted to bulldoze. Protesters stepped in to save the park and were promptly doused with tear gas. Governor Ronald Reagan called upon the National Guard to squash the conflict, but it only led to more chaos — including the death of a bystander, the permanent blinding of a protester, and injuries to more than 100 people. A fence school officials had put around the park before the riots began was promptly torn down. Eventually the university was forced to accept that its formerly empty lot would remain a park.

In 1970s New York — where a financial crisis had caused an uptick of abandoned buildings and lots in the Lower East Side, Hell’s Kitchen, and East Harlem — a nonprofit environmental group called the Green Guerillasbegan throwing “seed bombs” full of water, fertilizer, and seeds over fences and onto empty lots in an attempt to beautify them. One of the group’s founders, Liz Christy, eventually expanded its efforts by launching a campaign to remove trash and haul in soil to empty neighborhood plots. The legacy of environmental activists’ efforts has expanded in recent years, and neighborhoods feel encouraged to organize and contribute to local beautification projects, and build everything from chicken coops to beehivesin urban areas. It’s no wonder that the sight of flourishing green squares amid concrete buildings has since been symbolic of charitable, earthy activism.

The latest urban farming startups are not charities, though. They’re businesses. But they have not hesitated to co-opt some of the same talking points about local collaboration and healthy families heralded by their grassroots counterparts. The words “HEALTHY PEOPLE, HEALTHY COMMUNITY, HEALTHY PLANET” appear at the top of the BrightFarms website in all caps. Beneath them is the company’s mission statement: “For the health of the planet, by improving the environmental impact of the food supply chain. For the health of our society, by encouraging the consumption of whole and fresh foods.” AeroFarms goes one step further, declaring “We want to be a force for good in the world.” Square Roots’ explanation of why it exists is fittingly dramatic for a Musk brother’s operation: “Our cities are at the mercy of an industrial food system that ships in high-calorie, low-nutrient, processed food from thousands of miles away. It leaves us disconnected from the comfort, the nourishment, and the taste of food — not to mention the people who grow it. But people are turning against this system. People want real food — food you can trust to nourish your body, the community, the farmer, and the planet.”

Despite their admirable intentions, this new market is also exploiting a gray area in how people think about city-based farming. According to Raychel Santo, a program coordinator at Johns Hopkins’s Center for a Livable Future, the positive environmental, health, and community effects of independently run farms are now more frequently being lumped into the pitch decks of urban for-profit ventures.

“I do think people conflate the benefits of urban farms often: We can be less wasteful and improve food access and increase the number of jobs and things like that,” Santo said. “When people try to group all of the benefits together, you lose some of the granularity of the actual limitations of each type of urban garden.”

Even if the ultimate goal of these startups is to simply provide fresher, more nutrient-rich greens to urban areas, the messaging of many high-tech farming companies implies that their method of growing is a real solution to our future farming needs. “As the population grows, more food will need to be produced in the next four decades than has been in the past 10,000 years,” reads Bowery’s mission statement. “Yet resources like water are increasingly limited. There hasn’t been a practical path to provide fresh food at the volume and quality that people are looking for — until now.” When I spoke to Fain, he built on that statement, describing his business as the next logical stage for modernizing the world’s farms. “A lot of what the organic movement was about was how do we create a farming practice that allows better or slower regeneration and better protection of the land around us while also growing a higher quality food product,” he said. “And that was a great step. When the organic standards were written, a lot of the technology that we use today didn’t even exist. What we’re able to do at Bowery is the next evolution, the next step, from what organic was able to do from where industrial agriculture was before.”

Marc Oshima, cofounder of AeroFarms, also emphasized the company’s global ambitions by citing potential future projects in arid climates like Saudi Arabia. “It’s not just plants,” he said when I visited. “At the end of the day it’s about nourishing communities. It’s how we can build these responsible farms in major cities all over the world.” Musk made a similarly grand statement the day he announced Square Roots: “Our goal is to enable a whole new generation of real food entrepreneurs, ready to build thriving, responsible businesses,” he wrote. “The opportunities in front of them will be endless.”

Inreality, there are bigger food problems in the world than whether Manhattan grocery stores carry fresh arugula. The major challenges that our global agricultural system faces cannot be solved by urban farms alone.

According to Santo, whose research includes using climate change modeling to predict agricultural demand and supply, it’s projected that the global population will reach 9.6 billion people by 2050. As the effects of climate change set in and weather patterns become more volatile, farmers’ growing and harvesting seasons may be shortened or lengthened, depending on the circumstances, and they’ll be less certain of the amount of food they can produce year to year. Like many other countries, America’s food system is currently set up so that farms dedicated to specific foods — whether it be avocados, raspberries, or beef — are typically concentrated in a single location. So in a scenario in which different parts of the world are battling their own blizzards, droughts, or floods, the U.S. population would most likely experience frequent and significant shortages of specific goods. These shortages are already happening in different pockets around the world. At the beginning of March, a vegetable grower in southern Arizona that sells bags of baby spinach and “spring mix” announced that it ended its harvest earlier than usual because of an unusually damp season. This could mean a shortage of greens in early April. Similarly, snowfall in Spanish farming areas — a major source of England’s produce — has caused a temporarily low supply of zucchini, tomatoes, lettuce, peppers, and celery that began in the winter of 2016 and stretched into this year.

“The whole global food system that we rely on is heavily dependent on imports from other places and [a] very centralized system which creates a lot of potential problems,” Santo said. “A lot of research has gone into how the really complicated interconnected system that we’re facing is not very resilient if something were to happen to it.”

So, to what degree can these startups actually help? Even if vertically grown warehouse operations like Bowery, Square Roots, and AeroFarms help supplement a salad shortage here and there, their considerable output thus far still couldn’t come close to feeding, say, the entire city of New York, let alone the United States. (Especially since the average American craves a considerable amount of meat and dairy.) Unlike your average community or rooftop garden, typical vertical farms are located indoors, so they do nothing to help what environmental scientists call the “urban heat island effect,” a phenomenon that shows cities tend to be warmer than their surrounding landscape because of human activities and concrete structures. So far, Santo says the most significant effect commercial vertical farms might have on global food system issues is influencing the culture of food consumption and encouraging communities to learn more about where their food comes from.

(BrightFarms)

When it comes to disrupting that increasingly fragile industrial farming system, Santo argues that we may be better off relying on regional farms strategically placed outside highly populated areas to avoid blips in our system. Peri-urban (urban adjacent) greenhouse operations like BrightFarms are able to produce higher crop yields, and therefore have much more potential to make a dent in the system, while also avoiding the significant environmental and monetary costs that indoor farmers are forced to incur from powering stacks of bright LEDs.

“Greenhouses have a much greater potential,” Santo said. “There’s very little evidence of the substantial benefits [of vertical farming], in terms of environmental impacts, partially because of energy input, but also because you can use those buildings in other ways. You can be productive on rural and peri-urban land in much greater volumes.”

The Brooklyn-based company Gotham Greens is a successful test case for shrinking the greenhouse farm format to fit smaller metropolitan spaces, but still harvest enough produce to turn a profit. As some early indoor vertical farming startups have shuttered Gotham Greens CEO Viraj Puri has slowly expanded his business. The eight-year-old company employs about 150 people among four greenhouses, the newest of which recently opened in Chicago. Though Gotham Greens’s leaf mixes cost more than your run-of-the-mill lettuce bunch, they’re tastier, and generally stay fresh in the fridge longer than their grocery-store competition. Puri is heartened to see a new collection of vertical farmers experimenting with LED growing, though he’s not yet convinced that their methods make for a viable business.

“Our goal at Gotham Greens is to produce the most consistent, reliable supply of premium-quality produce in the most cost-effective manner, and today greenhouse technology provides that,” he said. “But I’m glad they’re doing the research. I don’t necessarily have an appetite to do a lot of research and development and not be profitable. That’s why you have technology companies.”

Still, visionaries of vertical farming remain optimistic that whatever challenges the industry faces will be sorted out as technology advances, and the government recognizes their utility. When Dickson D. Despommier, an emeritus professor of public and environmental health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, wrote a book about the possibilities of vertical farming in 2010, he wasn’t aware of any vertical farms that actually existed. He has since become one of the movement’s most prominent advocates. Though the vertical farming industry is in its infancy, he cites the rapid development of more energy-efficient LED lights and a growing variety of business structures as evidence that we will inevitably rely on indoor growing.

“Eventually the virtues of this will become so apparent that people will say: ‘What the hell are we doing outdoors when we can do this indoors?’” he said. “Just like they’re saying: ‘Why the hell should we burn coal when it’s much more efficient to get all your energy from solar and wind power?’”

Despommier points to Japan as a success story when it comes to the rapid adoption of vertical farms. After a massive earthquake and subsequent tsunami shook the country in 2011 and its Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant contaminated about 5 percent of the country’s farmland, the Japanese government rushed to secure alternate food solutions. It was what Dickson described as “the perfect storm” to encourage full integration of urban farming. Now, he says there are hundreds of vertical farms across the region, sometimes even integrated into workplace cafeterias. In many cases they’ve solicited the expertise of technology companies like Panasonic and Philips to establish more efficient farming methods.

“There’s not going to be instant success here any more than there was in the beginning of, say, Nokia,” Despommier said. “You can go down the line and see how advances in technology and efficiency of using that technology results in replacing the original invention with something that’s much better. That’s what the human species is very good at doing.”

For all the discussion of growing healthy communities, often the only way to balance the expenses of indoor urban farms is to cater to people who already have the money to buy fancy lettuce. In other words, their customers are gourmet restaurants, health-conscious tech companies, and Whole Foods clientele. All this despite the fact that most urban warehouse farms set up shop in low-income communities, where empty buildings are more plentiful and cheaper to rent. A box of AeroFarms greens costs $3.99, while Bowery’s greens go for $3.49 — loads more than someone on a budget might be willing to pay, when they can just grab a much cheaper loose head of lettuce. As a May 2016 report from the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future noted, “urban agriculture projects are not panaceas of social inclusion or equity.” According to Santo, disparity in access to more nutritious produce is a frequent pattern of for-profit city farms.

“Private companies like these put buildings in communities of lower income or communities of color,” she said. “Oftentimes they produce these really expensive greens for restaurants, but then go serve wealthy people for a different community in the city.” In short, the Whole Foods crowd simply has yet another option for fresh greens, and the communities housing the operations providing them can still afford only the same old wilted lettuce.

AeroFarms has come the closest to overcoming the many challenges of the modern vertical farm. The operation’s 70,000-square-foot facility in Newark, New Jersey, can grow 2 million pounds of food each year. It’s currently renovating a former steel supply company building half a mile away from its current headquarters, creating what will be its third major farm and a symbolic gesture of rehabilitation for the city. The startup has raised more than $70 million in venture capital from the likes of Prudential and Goldman Sachs.

“They’ve looked at our history, they’ve looked at our operating costs, and they’ve seen what the demand is,” cofounder Marc Oshima told me when I visited the farm. “They foresee why they want to be a part of this.”

The true question of Silicon Valley investors is almost always: Can a business scale up? Is it a Foursquare (doomed to mild popularity) or an Uber (able to expand at a near-terrifying pace)? The question is particularly tricky for something as intricately designed and finicky as a farm, which can’t simply be revamped by overhauling a portion of code or redesigning its user experience. But of all the vertical farming startups on the market at the moment, AeroFarms is closest to proving that its model is solid enough to be plopped in any urban center on the planet and still deliver the same amount of product on the same timetable. (In its case that product is limited to six different salad box mixes of leafy greens.)

The company was founded in 2004, thanks to the curious mind of Ed Harwood, an inventor and former associate professor at Cornell’s agriculture school, and AeroFarms’ current chief science officer. Harwood has toiled over refining each element of the company’s tightly coordinated growing process, from making LED lighting more energy efficient, to developing the best possible reusable fabric into which a variety of seeds can be sown to germinate and grow (his final iteration is patented). All of these elements are incorporated into each of the seven planting beds that fit into the Newark farm’s 20-foot-high, custom-designed towers.

The inventor’s secret sauce is a proprietary nozzle used to mist a plant’s roots with with nutrient-rich water, a method called aeroponics that cofounder Oshima says uses 95 percent less water than traditional farming, which is even less than hydroponic farming uses — and less than the average aeroponic farm uses. (He also made sure to mention it was “perfect” that I had chosen to visit the company’s HQ on World Water Day.) In addition to saving water, he claims the misting speeds up the growth rate of the plants themselves.

“The roots are able to get oxygen, which leads to a faster growing process, more biomass in a shorter period of time,” Oshima told me in a cold, messy meeting room that had a hole in the wall, a visual indicator of where this tech company’s priorities lie. “When we think about the business of farming, how do we have the right economics, how do we compete with that field farmer, in terms of scale, cost, and productivity? We think that aeroponics is part of that equation.”

AeroFarms’ plant beds aren’t mostly autonomous like Bowery’s. In fact, those tasked with examining plant life as it grows must stand upon adjustable accordion-like platforms to properly examine their subjects. But the company has collected a trove of data over the years from testing over 250 varieties of plants, and is developing predictive analytics and machine-learning softwares that are not unlike the kind Fain has advertised. Developers even made an in-house app to monitor the rapid progress of the crops. And when it comes to the taste of their greens, AeroFarms has earned the endorsement of chefs like Michel Nischan, a three-time James Beard Award–winning chef who also founded Wholesome Wave, a nonprofit that aims to improve access to fresh produce in low-income communities. Though Nischan is partial to produce grown the old-fashioned way, he was pleasantly surprised by the taste of AeroFarms produce.

(AeroFarms)

“Purely from a flavor and texture perspective, the stuff that comes out of the dirt is still superior to everything I’ve tasted, other than AeroFarms,” he said. “In my mind they were the ones that finally cracked the code. The spinach leaves are hearty, really sturdy, they had a really great texture to them, a really deep color, and when I ate them I got the flavor intensity that you get from nutrient density.”

As for community outreach, AeroFarms has made an earnest effort to integrate with its neighborhood however it can. In 2010, when the company was in its infancy and headquartered in upstate New York, Harwood sold one of the farming towers to the inner city Philip’s Academy Charter School, and the company still holds educational sessions there. (Last year, Michelle Obama toured the setup as part of her #LetsMove campaign to promote healthy eating and exercise.) Every Wednesday, employees set up a farmstand on the empty street outside the warehouse, even if the stuff it sells might be out of the price range for AeroFarms’ neighbors. The company has only 120 employees, many of whom are engineers, software developers, and microbiologists. But Oshima has made an effort to hire locals whenever he can, and takes pride in the fact that he’s taught people a skill scarcely practiced in a withering industrial town where unemployment is high. The company works with a local employment group to ensure over 40 percent of its workers are from Newark. While he was showing me the latest farm, one of them approached Oshima to ask about a work program that would allow the employee to take classes relating to urban farming. Recently, AeroFarms set up an informational booth at the brand-new Newark Whole Foods to spread the word about its product. As Oshima tells it, a mother and her baby approached to sing the praises of the company. “Future customer?” the AeroFarms employee asked, pointing at her child. “Future worker,” the mother replied.

“We get excited about how we can be an inspiration to the community,” Oshima, an otherwise reserved man, gushed. “So that was exciting.”

Nischan agrees that providing jobs to low-income communities is central to helping them afford better food. Beyond that, he argues that for-profit food companies that want to make their product affordable must structure their business plans to accommodate the extra costs that come with subsidizing a product.

“What AeroFarms is doing in Newark … by really focusing on hiring people from the local communities is actually the best beachhead that you can establish,” he said. “But when it comes to getting into Whole Foods and doing farm stands, if you want to help an underserved community because you’re producing food, and you want some of that food to transform the health of underserved communities in the place that your business calls home, you generally have to take some kind of a haircut.”

AeroFarms’ modest effect on the surrounding area is still germinating. And it may still be far off from its goal of becoming a global presence in destinations as far-flung as Saudi Arabia. But given that the vertical farming industry is exploring uncharted territory, what little impact it’s had is promising.

“There’s no playbook, no traditional government land grant,” Oshima said. “Universities aren’t developing the next generation of farmers — we are.”

While all the farmers I spoke to were eager to bridge the gap between the customers who can afford their high-quality produce and those who can’t, Jonathan Bernard seemed especially contemplative about the issue. The 24-year-old former accountant from Long Island grows premium lettuce in one of Square Roots’ narrow shipping containers, an operation that costs about $3,000 a month to maintain. The large rectangular boxes are lined up in the parking lot of the Pfizer building in Bed-Stuy, now an office that houses movie props and a variety of local food startups. At one point during the tour of his farm, he opened the door and pointed to the Marcy Houses, a cluster of public housing buildings across the street.

“Jay Z grew up right here, like literally,” he said, pointing to a fence. “And this fence is pretty symbolic of what’s going on. There’s a true barrier to getting in there. They have food deserts that they can’t get over. I can go back to Long Island, get whatever I want. But inside these communities they’re not getting fresh stuff.”

Bernard admits that he’s not entirely sure how to bring affordable food into a low-income community like Bed-Stuy without going out of business. “That’s kind of what we’re here figuring out,” he said. His intended business, a farm that grows nutrient-rich plants for performance athletes, also relies on an elite customer class. He recently showed off his operation to a handful of NBA players, and is also mulling the possibility of selling some decorative nasturtium leaves on the side to chefs, who will pay up to $60 a pound for the rare and fragile plant. Ultimately he predicts that the only way he can offer affordable produce to the people who need it most is by doubling his output.

“It costs money to light this thing, it costs rent to put it on this land,” he said. “If all else is the same, how do you get it cheaper? You have to produce more.”

Bernard isn’t currently individually paired with a business for weekly salad bag deliveries, but companies that have signed up have been impressed by the Square Roots service. As soon as Brannon Skillern, the 33-year-old head of talent management at stock exchange startup IEX, gathered about nine people in her office to participate in the program, she was visited by Square Roots farmer Electra Jarvis. Jarvis dropped off her first delivery, explained the properties of her heirloom-seed bok choy and that there was no need to wash it, and opened an email thread to encourage feedback. Soon Skillern started seeing her coworkers snacking on the greens straight from the bag. Though some people from the company have opted not to join because they’ve said it’s cheaper to buy salad at the grocery store, Skillern says that she values building a relationship with a farmer who’s within a mile radius of her home.

(Square Roots)

“It’s neat to have that back and forth with your farmer,” she said. “I follow Electra on Instagram and I can kind of see like ‘Oh, cool. She’s harvesting this this week.’ It just feels like the personal-connection aspect is not anything that you can get anywhere else.”

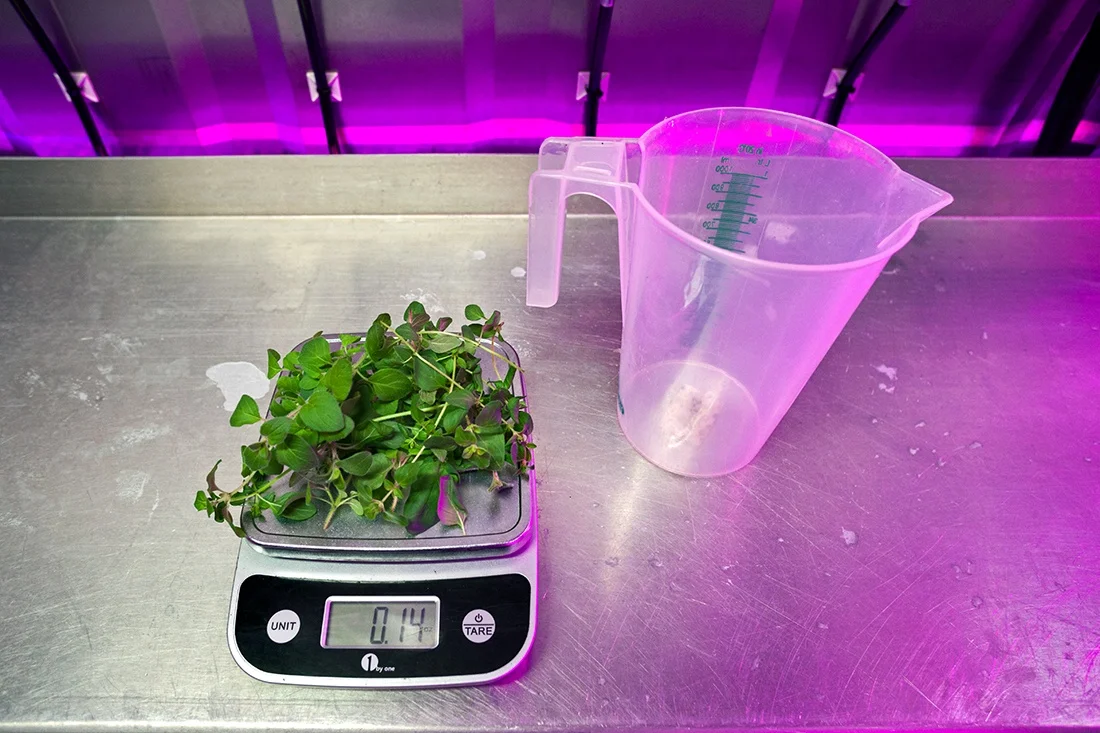

Bernard values that personal connection with customers as well. And the day I visited, he was testing a strategy to up his yield rate, in the hopes that he could nail down a structure that would allow him to give back to his surrounding community. He’d been tinkering with the temperature, light cycles, pH, and nutrient levels of his shipping container’s humming apparatus — powered by programs like Freight Farms and Bright Agrotech and monitorable via a smartphone app — to speed up the growth rate of his heirloom red leaf lettuce. Space in his narrow container is limited, so plants are stuffed into multiple rows of white plastic towers, which are rigged with plastic tubes for water delivery, and hung on a bar from the ceiling. Above them sit strands of red and blue LED lights (colored that way to beam only a portion of the light spectrum onto plants and conserve resources). Mixed together they wash the room in a purple glow.

Bernard unclipped a tower and placed it on a hook to remove a single bunch of healthy-looking lettuce, which he then placed on a metal scale. He recently began weighing each lettuce plant to measure whether he could produce 100 pounds of food a week. His goal was to hit somewhere between 4 and 5 ounces per plant. He grabbed this one ahead of schedule, to test whether his amped-up settings could help it get there earlier. Before delicately placing it on the scale, he pointed to a few tiny leaves sticking out at the root, which he proudly explained to be the remnants of the plant’s very first growth, and something that would’ve been quickly decimated in a traditional agricultural setting. The plant clocked in at 4.69 ounces, and a smile spread on Bernard’s face.

“That makes me really happy,” he said. “It’s the size that I wanted three weeks earlier than I expected.” It was a small triumph for him, maybe a microscopic one in the larger industry of vertical farming. But it was progress. We celebrated with a tasting. The lettuce was flavorful, crisp, and juicy. He sent me home with a bunch, along with a baggie of his pricy nasturtium leaves. It lasted in my dinky fridge for well over a week.

'Vertical Farming' Brings Futuristic Growing Methods To Middle Tennessee

'Vertical Farming' Brings Futuristic Growing Methods To Middle Tennessee

Mona Hitch reaches for celery at the top of one of her vertical farm towers.

CREDIT CAROLINE LELAND

Mona Hitch tends to one of her 8-foot vertical farming towers. She says she and her husband eat salads grown "vertically" in their greenhouse every day.

CAROLINE LELAND

Originally published on April 11, 2017 9:56 am

There’s a bit of science fiction sprouting up in greenhouses around Middle Tennessee. It’s called vertical farming, and it’s basically like growing vegetables in a greenhouse on steroids.

Vertical farming incorporates methods that seem futuristic — aquaponics, aeroponics, and hydroponics — that can provide locally grown vegetables year-round. And even if it won’t immediately solve food shortages around the world, vertical farming is predicted to reach almost $6 billion in revenues within the next five years.

Springfield resident Mona Hitch tends a greenhouse filled with rows of eight-foot PVC towers. Edible plants peek through dozens of holes drilled into the sides. Hitch’s greenhouse contains ten of these towers, though it has capacity for 50. Right now Hitch is growing multiple lettuce varieties, different kinds of kale, just about any herb you could think of, even edible flowers.

“I fell in love with it for several reasons,” Hitch says. “I know where my food is; I know what’s on it. I’m my own pest control, and I can just step outside in flip flops and pearls or high heels and we have salad every day.”

Lisa Wysocky displays a model of the LED lighting system she plans to use in a vertical farm on her nonprofit's property.

CREDIT CAROLINE LELAND

Any non-root crop that’s not too tall can grow in a vertical farming system.

Hitch’s system cycles water with dissolved nutrients from 20-gallon tanks at the base of each tower, through the plant roots inside the vertical PVC pipes. There’s no soil involved. This method is called aeroponics, because the plants are suspended in the air.

All About Efficiency

Supporters of this system argue that it will become commonplace and even trendy, like cruelty-free factory farming for plants. Vertical farming uses 90 percent less land and up to 95 percent less water for a higher yield, with no pesticides.

Facilities can be built on rooftops and in empty warehouses, and certain plants can grow year-round regardless of weather, in less than half the time.

Lisa Wysocky, the executive director of an Ashland City nonprofit called Colby’s Army, plans to build a solar-powered vertical farm for charity on her property by May. Folks will be asked to pay what they can for the vegetables.

“We can grow food very quickly,” Wysocky says. “We’re looking at 1400 heads of lettuce or tomato plants that we can turn around every three weeks…and get produce out to people who need it the most.”

Entrepreneurs also see big potential: like the full-scale vertical farm that’s being built in Springfield and is expected to top a million dollars in annual revenue.

This farm will license technology from a Canadian company that has used the same technique for growing cannabis. Nick Brusatore, a spokesperson for Affinor Growers, said in a webcast that he’s excited for international expansion.

“We believe that given the proper technologies added to this process, we can be pretty close to net zero, or almost off the grid, or independent of energy,” he said. “And we feel that if we can achieve this, then this should be able to be duplicated all over the world in a modular process.”

Niche Market Or Mass Movement?

It could sound too good to be true, but there are drawbacks. It takes lots of money, energy and materials to build and light indoor growing spaces. Because vertical farming is indoors, bees and other insects are left out of the pollination process. Since there’s no soil involved, there’s been a controversy over labeling. Vertical farms have struggled to get organic certification because the system is seen as too artificial, even if there are no pesticides. In terms of output, high-calorie crops like grains or potatoes can’t grow with vertical farming.

Tennessee Agriculture Commissioner Jai Templeton says state government doesn’t track vertical farming. Nor are there special regulations. Even companies looking to start commercial ventures say they won’t compete with traditional row crops. Their produce will cost more and be available in the off season. Templeton says he encourages the technique because of the limited impacts on water, air, and soil quality.

“It's an environmentally friendly method in many ways to produce local foods for a segment of the population who wants to know where their food comes from,” Templeton says. “It's not going to replace the traditional agriculture, but it has its place because the population is growing.”

Vertical farming has taken off in population-dense countries like Japan, South Korea, and China. By comparison, Middle Tennessee remains relatively pastoral. But already, some local stores and restaurants have begun carrying vertically farmed produce.

Copyright 2017 WPLN-FM. To see more, visit WPLN-FM.

A Former Corporate Banker Plants New Roots in Urban Farming

Apr 11, 2017

A Former Corporate Banker Plants New Roots in Urban Farming

By MOLLY SMITH

Photography By LYNDA GONZALEZ

Reporting Texas

Alejandra Rodriguez Boughton carries seedlings that are ready to transplant. She founded La Flaca, an organic urban farm that grows rare produce for local needs. “Most people that live in cities don’t know a farmer, so people are always shocked when I tell them what I do for a living,” she said. Lynda Gonzalez/Reporting Texas

Like many graduates of MBA programs, Alejandra Rodriguez Boughton starts her day around 6 a.m. But she isn’t up early to check the financial headlines. Instead, the day’s weather is her primary concern.

Rodriguez Boughton’s office is a small two-bedroom house on a quiet cul-de-sac in Southwest Austin. There’s little shade or cover in the yard where she spends most of her work day, converting what once was grass into farmland.

Raised beds line the side of the house, where she has planted radishes, beets, peppers and bananas. Planters behind the house contain edible flowers, micro-greens and a wide array of herbs, including seven types of mint and 22 varieties of basil, one of which tastes like bubblegum. A large greenhouse contains seedlings to transfer to the yard, and racks of plants fill the garage.

On a half-acre, she’s managed to grow 195 types of herbs, edible flowers and vegetables, whose seeds originated from across the globe. There’s even a beehive and hens on the property.

Rodriguez Boughton pours a layer of topsoil to prepare a new area for seedlings. Lynda Gonzalez/Reporting Texas

When Rodriguez Boughton, 33, moved to Austin in 2012 from her native Monterrey, Mexico, to attend the University of Texas at Austin’s McCombs School of Business, she didn’t envision adding the title of farmer to a resume that includes nearly six years in corporate banking. But in July 2014, she founded La Flaca and has since worked to grow the business into a profitable urban farm.

She moves around the farm with an ease and quiet confidence that belie her relative inexperience. She’s been farming only for a couple of years.

“Most people that live in cities don’t know a farmer, so people are always shocked when I tell them what I do for a living,” she said.

She doesn’t fit the traditional image of a Texas farmer. For starters, she’s nearly half the average age of farmers in the state. She’s also a woman and Latina.

Rodriguez Boughton is part of a growing number of women turning to agriculture. Today, 30 percent of U.S. farmers are women, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, up from 21 percent in 2007. Some, like her, are embracing it as a second career.

Her first inkling of a future career change came when she received a promotion at Banorte, one of Mexico’s largest private banks. “I realized I didn’t want my boss’ job or my boss’ boss’ job,” she said. Yet she pursued an MBA anyway, hoping that it would reinvigorate her interest in the financial world.

It was during the final weeks of the program when Rodriguez Boughton was in the midst of final-round interviews with Microsoft and other companies in Austin that she realized her definition of success had changed. “I was not looking to work hard and get money as I was in my 20s,” she said. “I wanted a purpose.”

In times of stress, Rodriguez Boughton found herself in the kitchen and she sought comfort in recreating her favorite dishes, toying with the idea of starting a business around cooking high-end Mexican cuisine. But she couldn’t find the chilhuacle peppers she needed to make Oaxacan mole tamales. She started growing the peppers, rarely found outside of Mexico, on her apartment balcony.

“One day in the shower it just struck me: what if I started growing rare produce to address local sourcing needs?” she said.

Given that she had no background in farming, she started going to agriculture conferences and took online and community college classes to learn everything she could about sustainable, small-scale farming. She also hired her first and only employee, Ben Carroll, who studied horticulture in college and moved from Connecticut to join La Flaca after meeting Rodriguez Boughton through a mutual friend.

Rodriguez Boughton pulls weeds on her farm, where she grows rare produce for local customers. Lynda Gonzalez/Reporting Texas

Her business background, paired with Texas’ year-round growing season, attracted Carroll, 25, to the position. “Farms fail because farmers have no business experience,” he said. “Farmers need to think like bankers.”

La Flaca sources produce, including chilhuacles, to seven Austin restaurants, including Olamaie, L’Oca D’Oro and Mattie’s at Green Pastures. It also sells produces to its neighbors in the cul-de-sac.

Unlike Rodriguez Boughton, most women aren’t the principal operators of Texas farms – they run 15 percent of farms in the state, one point above the national average, according to the 2012 USDA Agriculture Census, the agency’s most recent survey. Nationwide, women only own 7 percent of farmland.

Nine percent of farms in Texas have operators who identify as Hispanic or Latino, which is slightly higher than the national average of 3 percent.

“To become a farmer is a capital-intensive business and like any other business it takes money to make money,” said Robert Maggiani, a sustainable agriculture specialist at the National Center for Appropriate TechnologySouthwest Regional Office in San Antonio. “If you don’t have collateral and assets and you can’t borrow money, then you can’t really get into land unless you inherit it.”

Maggiani said that many Latinos also associate farming with poverty because that’s the way their families have experienced agriculture for the last half-century. “It’s not something that’s been promoted” in younger generations, he said.

Rodriguez Boughton decided to embrace small-scale agriculture because she wanted to remain in Austin, where the cost of land is on the rise. “Millennials aren’t moving to the country,” she said.

She relied on savings from her previous career to reduce the financial risk of jumping into an industry in which she had no experience. She purchased a small home in Austin’s Maple Run subdivision and rents out the rooms to cover the farm’s cost. A $5,000 grant from UnLtd USA and another in the same amount fromthe Austin Food & Wine Alliance have helped offset costs.

“Agriculture is a business that takes time to be self-sustainable,” she said, adding that she hopes to break even by the end of this year.

La Flaca translates to “the skinny woman,” and it’s also one of the names given to the Grim Reaper. Rodriguez Boughton chose a sugar skull, a calavera, for her logo to represent Mexican culture and reflect the farm’s young, urban feel.

“One of my favorite things of Mexican culture is how we make fun of our fears,” she said. “The biggest fear I’ve faced so far in my life was quitting a stable, profitable career to leap into the great unknown. So that logo and that name is a constant reminder to shake off my fears and keep moving forward.”

Her three goals for the end of the year are to grow more, get more people in the community growing and avoid bankruptcy. She’s working to recruit the farm’s neighbors to turn their own yards into gardens and to expand the city’s community of first-time, urban farmers. In five years’ time, she hopes to have transformed five acres of urban soil into productive farmland.

Edwin Marty, the food policy manager for the City of Austin, hopes that La Flaca’s story will change people’s perceptions of what good food means and get more people interested in growing.

“How we get out of the idea that good food is only for rich white people is a real challenge,” he said. “In all honesty, nothing could be farther from the truth, but that’s certainly a perception.”

Rodriguez Boughton said the fear that farming will ultimately not be financially sustainable still causes her many sleepless nights.

Rodriguez Boughton plucks an unwanted caterpillar from one of her plants. Lynda Gonzalez/Reporting Texas

“The way I try to approach this is to think ahead. I have clear goals on key metrics [in terms of] customers, sales [and] expenses that I constantly track,” she said. “When things are not working according to plan, I already have a plan B, C and D lined up. If this business ends up not succeeding for any reason, I want to have peace of mind that I gave it my all.”

Urban Farmer Transforms Community Into Thriving Local Food Haven

Sheryll Durrant. Photo credit: Keka Marzagao / Sustainable Flatbush

Urban Farmer Transforms Community Into Thriving Local Food Haven

By Melissa Denchak

Most people don't move to New York City and become farmers. Sheryll Durrant certainly wasn't planning to when she left Jamaica for Manhattan in 1989. She got her undergraduate degree in business from the City University of New York's Baruch College and spent the next 20 years in marketing. Then, when the 2008 financial crisis hit, Durrant decided to leave her job and try something new: volunteering at a community garden in her Brooklyn neighborhood.

It wasn't exactly uncharted terrain for this farmer's daughter. Growing up in Kingston, Durrant regularly helped her parents harvest homegrown fruits and vegetables. "But it didn't dawn on me that that was what I wanted to do," she said. Volunteering in the Brooklyn garden reminded her of her roots. "I would plant flowers or melons and that sense of putting your hand in the soil and becoming a part of that green space flooded back to me," she explained.

Kelly Street Garden.Craig Warga

Fast-forward to today. Durrant is a leader in New York's flourishing urban farming movement, which includes more than 600 community gardens under the city's GreenThumb program, plus hundreds more run by other groups across the five boroughs. A food justice advocate with a certificate from Farm School NYC, she's also a "master composter" and a community garden educator and she does outreach work for Farming Concrete, a data collection project that measures, among other things, how much urban farms and gardens produce.

Durrant's early work at the Sustainable Flatbush garden taught her the crucial first step in initiating any community project: Know your neighborhood's needs.

"We started by asking people in the community, 'What do you want to see?,'" she said. This market-research approach turned out to serve her goals—and her neighbors—well. When community members, many of whom were immigrants, expressed a desire to grow the plants and herbs of their native countries, Durrant and her fellow green thumbs collaborated with a local apothecary to establish a medicinal and culinary herb garden and to organize free workshops on how to use the herbs. These garden sessions—which covered women's and children's health, eldercare, and mental health issues like depression—at times drew more than 100 attendees.

After Brooklyn, Durrant relocated to the South Bronx, a neighborhood that's notoriously polluted, underserved and disproportionately malnourished, with more than one in five residents considered food insecure. The borough's gardens, said Durrant, help fill a void, serving as "one way we can bring fresh fruit and vegetables to a community that doesn't normally have access."

At the Kelly Street Garden, a 2,500-square-foot space on the grounds of an affordable housing complex, she serves as garden manager. And at the International Rescue Committee's New Roots Community Farm, a half-acre garden whose members include resettled refugees from countries like Myanmar and the Central African Republic, she works as a seasonal farm coordinator.

Keka Marzagao / Sustainable Flatbush

Last year, the Kelly Street Garden produced 1,200 pounds of food, available to anyone in the community who volunteered at the garden (and even those who didn't), free of cost. It was one of the few purveyors of healthy food in the neighborhood, where local stores often carry produce that's neither affordable nor fresh, due to lack of turnover. "If I have a limited amount of income, why would I waste my money or benefits on food that is going to perish in no time—that's already rotted when I get there?" Durrant said. For this reason, she explained, people often resort to purchasing processed foods that come in cans and bags. The longer shelf life stretches a tight budget. It also demonstrates why hunger often goes hand in hand with obesity—a problem particularly prevalent in the Bronx.

"I'm not going to say that community gardens and urban farms can feed New York City. Please, it's a city with over eight million people," Durrant said. "But they can provide some relief." What's more, she added, "They give you access to grow the food you want. That's where the food justice part comes in."

Margaret Brown, a Natural Resources Defense Council staff attorney who works on food justice issues, echoes Durrant's words. "One garden isn't going to fix hunger in your neighborhood, but community gardens are a way for people to take ownership over the food system in a very tangible way."

Of course, community gardens give rise to much more than fruits and vegetables. Durrant explained that the Kelly Street Garden serves as a space for cooking workshops and on-site art projects and hosts its own farmers' market. Meanwhile, the New Roots Community Farm has helped some of its neighborhood's newest arrivals find one another. "It's a means of engagement that a lot of our refugees are familiar with," she said. "It's welcoming, safe and a place where people can learn at their own pace and get involved in the country where they now live." Participants practice English ("Food is an incredible tool to teach English—a great entry point," said Durrant); plant hot peppers, mustard greens, melons and other edibles from their native homes; and exchange recipes.

Keka Marzagao / Sustainable Flatbush

Urban gardens also play a role in nutrition education. "Anecdotally, we've seen that when kids go to a community garden and get exposed to fresh fruits and veggies, they're much more likely to eat them when they're offered on the school lunch line, salad bar, or at home," Brown said.

Perhaps most important, the community garden movement and its focus on food inequities help advocates raise awareness of broader, interconnected environmental justice issues—like low wages and lack of affordable housing—that get to the heart of why people struggle to access healthy food to begin with. "Community gardens form a good space for people to come together around those issues," Brown said, "and hopefully find great organizing allies."

Durrant is clearly one of them. As part of her community outreach work, she arranges events to bring new audiences (whether corporate employees on volunteer workdays, or visitors on a Bronx Food & Farm Tour) directly through the garden gates. These visitors get a glimpse of the power of a small green lot in a sea of concrete—and if they're lucky, they leave with a taste of it, too.

Melissa Denchak is a freelance writer and editor, and has contributed to Fine Cooking, Adventure Travel, and Departures. She has a culinary diploma from New York City's Institute of Culinary Education and loves writing stories about food.

An Interview With Architect Nona Yehia of Vertical Harvest by Christine Havens

An Interview With Architect Nona Yehia of Vertical Harvest by Christine Havens

04/10/2017 08:33 pm ET | Updated 19 hours ago

Jackson Wyoming is best known for its upscale resorts and breathtaking Teton mountain backdrop. It’s a city that averages 38 feet of snowfall annually, with a short four-month growing season. A playground for skiers and outdoor enthusiasts it may be, for gardeners not so much.

Thanks to the vision of architect Nona Yehia and her co-founder, Penny McBride, the two have transformed the way Jackson receives some of its vegetables. In a town that’s long been dependent on trucked-in produce, Vertical Harvest is a step in the direction of sustainability. Their innovative three-story greenhouse occupies a narrow 1/10th of an acre lot and turns out an astonishing 100,000 pounds of produce each year; that’s roughly the same yield as a conventionally farmed five-acre plot. And in doing so, Vertical Harvest provides jobs for the developmentally disabled, some of Jackson’s most vulnerable population.

Christine Havens: What prompted you to start Vertical Harvest?

Nona Yehia: “It’s funny, I never set out to be a vertical farmer. I’m an architect by trade, and I believe in the power of architecture to build community. I’ve always pushed the boundaries in design, I’ve always been engaged. It’s a labor of love,” she laughs and then goes on.

When we came to Jackson Hole, we were very committed to building whereas in New York, and we entered lots of competitions. In 2008, the economy tanked and it was kind of incredible — in those moments that’s where innovation and new thought can happen, when there are a lot of constraints. There wasn’t much building going on at the time, so I started getting involved in community projects. I helped conceptualize a park in the middle of town and I fundraised for the project; I started building more connections outside of the world of architecture.

CH: Wow, so at what point did Vertical Harvest materialize?

NY: Right when I finished the park project I connected with Vertical Harvest co-founder, Penny McBride. She spent a lot of time pushing sustainability in the community, and she’d worked on multiple community projects including a composting program. Penny had always had the desire to create a space for growing in Jackson. I’m a foodie, and while Penny was thinking of this, I was also exploring how to create a residential scale greenhouse that could last a Wyoming winter. We only have a 4-month growing season, and our produce is trucked in during the winter.

Jackson acts more like an urban community because of its proximity to a national park. Penny had a hard time finding a site, so we came together conceptually and started talking to a lot of stakeholders. Through that process, we met a woman named Caroline Croft. She was an employment facilitator working with developmentally disabled residents. I have a brother with a developmental disability, so growing up I’ve was acutely aware of how our society nurtures this population in school, but when it comes to adults and employment—they’re on their own. That doubled my commitment to the project. In 2009 we started exploring the concept of Vertical Harvest in earnest.

A town councilman who has a son with a disability came to us and proposed a site. Initially, he thought we’d install a simple hoop house that might employ a few people. We scratched our heads; the property wasn’t ideal for a hoop house. That’s where my training as an architect gave us the confidence to push the boundaries, and we thought “what if we go up” and “how can we do this year round?” Now looking back we have 15 employees, and they share 200 hours of work between them in the greenhouse, based on a model called customized development.

CH: That’s incredible. How much produce does the greenhouse currently produce?

YH: Essentially, we’re growing five acres worth of vegetables on 1/10th of an acre. Vertical Harvest is an example of how architecture can respond to community needs while serving a local population. The ultimate goal is that our model can be scaled and replicated by other communities around the globe. It’s pretty unique, and that’s what keeps us all very passionate.

CH: Tell me a bit more about your process in designing the greenhouse.

YH: Early on we were able to connect with a Danish engineer who is on the forefront of hydroponics. The Dutch have been perfecting this method of farming for generations. They have a lot of land but limited sunlight, and they’ve been using greenhouses to supplement traditional agriculture for centuries. They saw Vertical Harvest as an opportunity to enter into the American market. I get calls all the time from people who want to replicate this project; none of the manufacturers have embarked on a project like this before.

At its core, Vertical Harvest is a machine for producing food; it operates as a complete ecosystem. Our greenhouse model functions as three greenhouses stacked on top of each other. Each floor has its own microclimate. We have tomatoes and fruit on the top floor and lettuce on the second floor. While most greenhouses are mono crops, we use a mechanical carousel to rotate crops—it’s like a like dry cleaning carousel on its side—and spans the entire 30’ of the building. The carousel was one of our biggest pieces of innovation and reduces the amount of LED we would otherwise need; it balances natural and artificial light, and it also brings the plants right to the employees for harvesting and transportation. There are only two mobile systems operating in the world.

CH: In light of your success, what’s next?

YH: One of the reasons I’ve stayed on is to learn as much as I can, if we prove to be a successful model, we can take it on the road. Each greenhouse will be adapted to suit its climate, the environmental conditions in Jackson Hole are unique. We danced on the line of innovation, and we defaulted to typical greenhouse infrastructure when we thought we could save some money. At the time we didn’t have much of a budget, so there are some problems in the design. For example, we now know that there’s not enough ventilation for our tomatoes on the third floor. The next greenhouse we build, we’ll be able to correct these issues. As much as Vertical Harvest is a business, we see it as a demonstration project as well. We’re trying to get the information assembled so that others could learn from it.

I’ve always envisioned this as a model that could feed communities; it wasn’t designed for maximum productivity or revenue. Once we get all the zones dialed in more, we’ll be able to push forward. It’s always figuring out that perfect balance. It’s incredible — there was a huge team of people that came together to work on this project.

Vertical Harvest’s social mission is what makes us unique. That’s why our team is so dedicated; we’re helping communities and reducing food miles. And at the same time, we’re pairing innovation with an underserved population. The impact has been really profound, and it’s also changed me. Once you see the effect that a project like this can have in a community, it’s hard to go back. I don’t feel like this process has ended; we’re still designing the trajectory, we’re still expanding the notion of what it is to be an architect. We now have a lot of interested parties, but we’re dedicated to making sure it’s a model that will work.

When people hear about Vertical Harvest, they want information and they want it now. We’re trying to ride this momentum responsibly; we’re trying to continue the conversation. When I look back at our board and dedicated employees, and think about what we’ve accomplished, I’m amazed at how far we’ve come. We tend to be pretty hard on ourselves. We always have a goal in mind, and it took us eight years to get where we are today. We’re not in a rush; we want to get it right.

For more information about Vertical Harvest, click here.

Read more interviews by Christine Havens at Seed Wine. Seed Wine is a gold medal winning, single-vineyard, Malbec from the prestigious Altamira district of Uco Valley, in Mendoza, Argentina. It is a wine of unsurpassed complexity and balance, whose story is one of serendipity, adventure, and love.

This Farm In A Shipping Container Is More Than Just A Source of Local Produce

This Farm In A Shipping Container Is More Than Just A Source of Local Produce

Mats von Quillfeldt prepares lettuce seeds in the repurposed shipping container. He is one of the students participating in the Mason LIFE program. (John McDonnell/The Washington Post)

By Sarah Larimer April 10

The repurposed shipping container is tucked in a parking lot, behind an office building and warehouse in Woodbridge, Va. From the outside, it might not look that special.

But on the inside . . . well.

Rows of seedlings poke out of trays that are nestled under a shiny workspace. More than 200 thin towers, packed with growing produce, stretch to the back. The lighting casts a purple glow, and visitors trade sneakers for shower slippers, to keep the space uncontaminated by the outside world.

The cramped container has a bit of a “Mad Scientist” vibe, or at least a “Mad Scientist Who Is Super Into Locally Grown Produce” vibe. This is Zeponic Farms, a hydroponic farm that is more than just a source of lettuce. The Northern Virginia farm also partners with a George Mason University program for people with developmental and intellectual disabilities.

“I’m really big on being a social entrepreneur,” said Zach Zepf, a founding partner of Zeponic Farms. “I think that if you’re going to start a product or a service, it should have something that’s meaningful.”

Lettuce grows in the converted shipping container in Woodbridge, Va. (John McDonnell/The Washington Post)

The farm, which grows lettuce, greens and herbs, works with Mason LIFE, a four-year program that offers educational and work experiences to a community with special needs. This partnership is still pretty new, but Zepf said he hopes for an expansion of the operation, and an expanded role for Mason LIFE.

“We bought this thing to be a life changer,” said Brenda Zepf, Zach’s mother. “Not only for our son but for other young adults like him.”

Brenda Zepf isn’t talking about Zach there. She’s talking about his brother, Nic, who has autism and other chronic health issues. The Zepf siblings would garden together in the back yard of their Springfield, Va., home, said Zach Zepf, growing kale, zucchini, tomatoes and chard.

“Not really lettuce, funny enough,” he said.

Now they have this farm, which is a really fancy upgrade. Nic, 23, is not a student in the Mason LIFE program, but Zach, who is 25, said he works there, too.

“It’s really special to be able to give my brother a career like this,” Zach Zepf said. “It’s an opportunity that he probably wouldn’t have unless someone created it for him.”

The LIFE program is not the farm’s only connection to the university. Lettuce grown at the farm is sold to Sodexo, the company that operates Mason’s campus dining services. It is served in a dining hall, said Caitlin Lundquist, Sodexo marketing manager.

Nic Zepf, left, Mats von Quillfeldt and Zach Zepf prepare lettuce seeds in a tray. (John McDonnell/The Washington Post)

“We sell them everything we have,” Zach Zepf said.

The farm started a year ago. Zepf said he hopes one day to bring it closer to the public university’s campus in Fairfax County. He would also like to grow the farm, either with another container or by moving to a larger facility, which could accommodate more people.

“Whether we get more containers, build our own containers or expand into a warehouse setting, the goal is to expand our role with Mason LIFE and eventually provide employment,” he wrote in an email, adding that it would require the farm to move closer, “which we will be doing.”

This is the first full semester that Mason LIFE has sent a student to the Zeponic Farms container, which is about 14 miles from Fairfax. That student, Mats von Quillfeldt, is a 20-year-old from Charlottesville who has autism.

One of the characteristics of von Quillfeldt’s autism is echolalia, which means he repeats words or phrases that others say. That doesn’t really matter at Zeponic Farms, where he works solo as he goes through the seeding process.

“Mats has got a very brilliant mind, and he’s got a lot going on in his mind,” said Andrew Hahn, a Mason LIFE employment coordinator. “But because of the echolalia, it makes it a little bit more difficult to have a conversation, for example. But Mats does exceptionally well in his academic program. It’s just a little bit of a communication barrier.”

When Mason LIFE started in 2002, there were about 12 other postsecondary programs like it in the nation. Now, there are about 250, said Heidi Graff, the program’s director.

“It’s really quite a movement within the field of education,” she said.

About 50 students participate in Mason LIFE, taking courses and developing skills through a work specialty. Students work in fields that include child development and pet grooming, she said, and some, like von Quillfeldt, are placed in farming roles.

“For our students, what makes farming in particular a good skill is the repetitive nature,” Hahn said. “For different plants, obviously, there’s different seasons to plant. But as far as the routine goes, for most things, it’s pretty typical. They can build an easy routine.”

That’s true. Hydroponics can seem like pretty scientific stuff, but really, all hydroponics has to work through is a simple, step-by-step guide. The tasks can be therapeutic, Hahn said.

“It’s good for our students to be able to see the work that they’re getting done,” he said. “And it keeps them motivated.”

Brenda Zepf said that she has taken her son Nic to a dining hall on Mason’s campus and shown him the salad bar. She told him the lettuce was his — that he had picked it himself.

“Kids with special needs and young adults with special needs have the right to work,” Brenda Zepf said. “They need to reach their full potential and have the same work opportunities as anybody else, and to have a true sense of purpose when they wake up in the morning, just like anybody else.”

Sarah Larimer is a general assignment reporter for the Washington Post.

You Want Fresh? Dallas' Central Market is Growing Salad Behind The Store

You Want Fresh? Dallas' Central Market is Growing Salad Behind The Store

April 10, 2017

Written by: Maria Halkias

Fresh is a word that’s used loosely in the grocery business.

To the consumer, everything in the produce section is fresh. But most fruits and vegetables are picked five to 21 days earlier to make it to your neighborhood grocery store.

Central Market wants to redefine fresh when it comes to salad greens and herbs. It also wants to make available to local chefs and foodies specialty items not grown in Texas like watermelon radishes or wasabi arugula.

And it wants to be both the retailer and the farmer with its own store-grown produce.

The Dallas-based specialty food division of H-E-B has cooked up an idea to turn fresh on its head with leafy greens and butter lettuce still attached to the roots and technically still alive.

Beginning in May, the store at Lovers Lane and Greenville Avenue in Dallas will have a crop of about half a dozen varieties of salad greens ready for customers to purchase.

The greens will be harvested just a few dozen steps from the store’s produce shelves.

They’re being grown out back, behind the store in a vertical farm inside a retrofitted 53-foot long shipping container. Inside, four levels of crops are growing under magenta and other color lights. In this controlled environment, there’s no need for pesticides and no worries of a traditional farm or greenhouse that it’s been too cloudy outside.

Central Market has been working on the idea for about a year with two local partners -- Bedford-based Hort Americas and Dallas-based CEA Advisors LLC -- in the blossoming vertical and container farming business.

Plants are harvested inside a vertical farm in the back of the Central Market store in Dallas, Thursday, April 6, 2017. Central Market is trying out indoor growing, and the crops will be sold in the store beginning in May. (Jae S. Lee/The Dallas Morning News)

“We’re the first grocery store to own and operate our own container farm onsite,” said Chris Bostad, director of procurement, merchandising and marketing for Central Market.

There’s a Whole Foods Market store in Brooklyn, New York with a greenhouse built on the roof, but it’s operated by a supplier, urban farmer Gotham Greens.

The difference, Bostad said, is that “we can grow whatever our customers want versus someone who is trying to figure out how to cut corners and make a profit.”

Central Market’s new venture is starting out with the one Dallas store, said Marty Mika, Central Market’s business development manager for produce. “But we’ll see what the customer wants. We can do more.”

This has been Mika’s project. He’s itching to bring in seeds from France and other far off places, but for now, he said,“We’re starting simple.” The initial crop included red and green leafy lettuce, a butter lettuce, spring mix, regular basil, Thai basil and wasabi arugula.

The cost will be similar to other produce in the store, Bostad said.

Why go to so much trouble? Why bother with lighting and water systems and temperature controls in what’s become a high-tech farming industry?

“Taste,” Mika said. “Fresh tastes better.”

And the company wants to be more responsive to chefs who want to reproduce recipes but don’t have ingredients like basil leaves grown in Italy that are wide enough to use as wraps.

Tyler Baras, special project manager for Hort Americas, said with the control that comes with indoor farming there are a lot of ways to change the lighting, for example, and end up with different tastes and shades of red or green leafy lettuce.

Butter lettuce is harvested inside a vertical farm in the back of the Central Market store in Dallas, Thursday, April 6, 2017. Central Market is trying out indoor growing, and the crops will be sold in the store beginning in May. (Jae S. Lee/The Dallas Morning News)

Staff Photographer

In Japan, controlled environment container farms are reducing the potassium levels, which is believed to be better for diabetics, Baras said. “We can increase the vitamin content by controlling the light color.”

At Central Market, the produce will be sold as a live plant with roots still in what the industry calls “soilless media.”

Central Market’s crops are growing in a variety called stone wool, which is rocks that are melted and blown into fibers, said Chris Higgins, co-owner of Hort Americas. The company is teaching store staff how to tend to the vertical farm and supplying it with fertilizer and other equipment.

“Because the rocks have gone through a heating process, it’s an inert foundation for the roots. There’s nothing good or bad in there,” Higgins said.

Farmers spend a lot of time and money making sure their soil is ready, he said. “The agricultural community chases the sun and is at the mercy of Mother Nature. We figure out the perfect time in California for a crop and duplicate it.”

Growers Rebecca Jin (left) and Christopher Pineau tend to plants inside a vertical farm in the back of the Central Market grocery store in Dallas, Thursday, April 6, 2017. Central Market is trying out indoor growing, and the crops will be sold in the store beginning in May. (Jae S. Lee/The Dallas Morning News) Staff Photographer

He called it a highly secure food source and in many ways a level beyond organic since there are no pesticides and nutrients are water delivered.