Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Urban Farming Insider: With Glenn Behrman, Founder CEA Advisers, The Plant Shed, and Greentech Agro

Glenn Behrman first started the Plant Shed in the 1970's, and has been involved with urban agriculture for over 40 years. We caught up with Glenn to discuss many topics, including his personal story, container farming versus vertical farming, and what is wrong with today's perception of urban farming

Urban Farming Insider: With Glenn Behrman, Founder CEA Advisers, The Plant Shed, and Greentech Agro

Glenn Behrman first started the Plant Shed in the 1970's, and has been involved with urban agriculture for over 40 years. We caught up with Glenn to discuss many topics, including his personal story, container farming versus vertical farming, and what is wrong with today's perception of urban farming.

UV:

Can you tell us a little bit about CEA Advisors and what you guys are working on now and how you got started? What is your background in the urban farming industry?

Glenn:

My career started in the foliage industry in the early '70s. When I first started there was no such thing as a real foliage industry. It was houseplants but (at the time) there was no such thing as houseplants. You know what I mean? There was no Home Depots and no aquaculture and no LED lights. There was no real marketing channel. It was a fragmented industry.

It was ripe for disruption. When I went into it, I had no experience and no real insight. I had nothing. I had no money. I had no education. I just knew it was a good idea and I just spent the next 25 years putting one foot in front of the other and building up a business that was a very substantial business that was one of the first real category killers before the term really existed.

The houseplant industry: A precursor to urban farming

UV:

That company (that dealt houseplants) was different than CEA Advisors? Did it have a different name?

Glenn:

Yeah, that was called The Plant Shed. It was in New York City. It was nine stores. I had an import division. I started traveling to the Philippines and Thailand and China back in the '70s and importing various lawn and garden products for sale in my own

stores.

The last store that I had in New York City, before I retired and sold the business, was 21,000 square feet. It was in a location that now could probably be, and I'm not exaggerating, now in New York City, would probably be $100,000 per month to rent.

UV:

These were primarily nonedible plants though, right?

Glenn:

Yeah, just houseplants, just ornamental plants for beautifying people's homes. It's funny because I kind of remember the first day, or the first time after Home Depot entered the market ... I remember for the first time telling somebody, "Look (now) plants are basically disposable." You put something in this corner in your living room and it looks beautiful for six months, and then it could die so you throw it away and you buy a new one.

You know what I mean? The whole industry, it went from a beautiful to ... It went from a living thing to a piece of furniture.

Glenn:

(Eventually) we started importing orchids from Thailand. We built a big nursery and a big plant brokerage business there. Then in 1994, I just sold everything and moved to Thailand.

UV:

What was the thinking behind that?

Glenn:

I just had enough. I had enough money. I had enough.Things were changing. Ikea was in the plant business. Home Depot was doing a big job. Rents in New York City were unbelievable. It wasn't fun anymore.

The Early Days of Urban Farming

UV:

How did you move from the foliage, as you say, to the more edible type stuff?

Glenn:

What happened was, while I was living in Thailand I became the landscape project manager for a casino project in Vietnam. It was a 500 acre site that was just sand. It had to be completely landscaped as a five star hotel.

As that project was coming to a close, I went to China to Hortiflorexpo, which is an event that's held every year in China. You know, like a horticulture exposition.

On my way back I read about a company in Holland that was starting to do research on indoor farming, using LED lighting, climate control and all that kind of stuff. I immediately went to Holland to meet with those people.

After we met I immediately tried to buy the U.S. rights to that company.

After seeing their technology. The seed for indoor farming was planted in my head. I went back home to Thailand. We had a big home and a farm and all that there. I told my wife, "You know what, we're moving back to America. I am going to get involved

with this new technology- take everything that I've learned and everything that

I've done and all the connections that I have, and I'm going to pursue this." That's what I did.

The beginning of GreenTech Agro

UV:

Did you start a new company at point, back in the States?

Glenn:

We started a new company called GreenTech Agro.

UV:

Okay, and then you eventually sold that company and then started CEA Advisors or is that company still around?

Glenn:

That company's still around. It's kind of dormant now. It's not doing anything one way or another. I had a partner in that company, he was just a silent partner.

Eventually I bought out the partner and started CEA Advisors, used it to pursue the highest and best use for vertical farming, rather than to concentrate on the Growtainer concept. In other words, I felt that containers and indoor farming had a lot more potential than just container farming.

Vertical Farming vs Container Farming

UV: You saw more potential in the vertical stacking inside of the container as opposed to just growing one level in the container? Why?

Glenn: No, in other words, what I am trying to say is, the first few years was spent strictly growing in containers and developing a system to grow in containers.

As I started to work out the problems associated with container growing, or container based production, I started realizing that this was not really the highest and best use for (controlled atmosphere) technology.

Problems With Urban Farming Container Growing

UV: What are some of those problems (with container growing)?

Glenn: Well, air circulation, humidity, climate control, an effective irrigation system. A container is not the best. For example, it's 10 feet high.

How many vertical levels can you put in there? How much production can

you put in there really without crowding the plants? There are some people,

they advertise that they can grow 45 plants per square foot.

Glenn: That's fantasy. This business, so much of it is hype. So much of it is bad information to people that don't know any better. It's difficult to really tell the truth,

whether it is good for you or not. People believe what they want to believe.

Understanding "plants per square foot" based off plant type

UV:

Does the plants per square foot ... Does that change based off of the type of plant? Are you talking about a best case scenario?

Glenn:

Well of course. You could sprout seeds at 45 seeds per square foot. You can't grow plants at 45 plants per square foot. A head of lettuce, for example, as it grows, it needs more space.

Glenn:

If I wanted to promote an untrue economic model, I would turn around and say, there are 216 seed cell trays that are 1.5 square feet, and tell people they can grow a hundred plants per square foot.

UV:

That's not even close?

Glenn:

It's not true. It's not true and it's not real and it's not economic. It's not based on any integrity. In other words it's based on just feeding. It's telling people what they want to hear.

Reliable urban farming brands to know

UV:

What are some of the brands in the industry as far as lighting or fertilizer or what not, that you view as, they've been high quality for a long time?

They're dependable. Somebody wants to get a top-notch system and get

really great lights. What are some of the companies they should be looking at?

Glenn:

It's not necessarily that ... In other words the criteria for let's say lighting, for example, which is a very very crowded market. First of all, the lighting is only ... All of the components are really based on what crop you want to produce, or what your

economic model is, or what your business model is.

In other words, listen I think Philips makes a good light for certain applications. I think Heliospectra makes a good light for certain applications. I think even Fluence ... I know it's Fluence, they make a good light. Every light is got to be matched through

the crop that you're trying to produce. Every fertilizer, in other words ... The whole key to successful vertical farming is about balance. It's not about any one particular product. It's that all the products work together and in conjunction with each other.

Knowing Variety and Desired Characteristics Before Growing

UV:

How do you go about finding that balance? For example, loose leaf lettuce, how would you view that balance?

What would be some of the best components for those, just because I know that's

a pretty popular crop?

Glenn:

Again, you're talking about lettuce. Are you talking about full heads? Are you talking about cut-leaf? Are you talking about ... You know what I mean? In other words there's so many ...

Listen, I get calls from people and they tell me, "Well I want to grow

lettuce." I'm like, "Okay, great." I then have ten more questions to ask them. In other words, lettuce is not generic. Lettuce is ... There's a hundred different varieties.

Are you growing something that's green? Are you growing something that's got red in it? Is the color important? Is the weight important? Do you have a post harvest facility? It's not all that simple. Everybody thinks it's that simple. It's not.

What Urban Farming Beginners Should Think About Before Growing:

UV:

Those are some of the considerations that people should be thinking about- some of the stuff that you just mentioned like the color, the weight, the facility after, the post harvest facility. Are there any other things that ...

Glenn:

Who's your customer, in other words, your packaging costs? Are you selling to restaurants? Are you selling to ... Listen the container, a 40 foot container is too big for a farmers market and too small for a supermarket.

UV:

Right, so that's more of a restaurant type fit, is what you're saying, or that's not what you're saying.

Glenn:

Right but then a 40 foot container could sell to a restaurant is a recipe for disaster.

UV:

Why is that?

Glenn:

An economic disaster because you're never ... They're never going to consume everything you produce.

UV:

Then they'll presumably ... You're saying that they may order from you every week, but the size of the order will be different.

Glenn:

Yeah, well of course. In other words, you're producing every day. You know what I mean? I feel bad for some of these people that have no business model. They're going to be under constant pressure to sell what they've created.

Understanding your urban farming business model:

UV:

How do you at least start? Obviously it may be a complicated total solution, but how do you at least start to address the bread and butter of the business model. What do you view as the fundamentals of that, addressing some of the problems we've been

talking about?

There might be a mismatch between demand and your supply. Managing the unit cost, how do you really look at that, just at least to get started? I know there's a lot of intricate details.

Glenn: This is a business just like any other business. You follow me? You really have to do your homework. The truth of the matter is that, again you are dealing with a market that doesn't ... They have good intentions.

You know what I mean. They don't realize how complicated it really is.

UV: You're talking about the buyers?

Glenn:

I'm talking about the growers, the customers, the indoor farm ... The Facebook ... The farmers that learned about this from social media. Learned about this from talking to their friends. They have an interest in pursuing this type of business model.

UV:

You're talking about people who

are actually growing the stuff or trying to.

Glenn:

Not growing it, but trying to.

UV:

Yeah, okay. You're saying they have good intentions but ...

Glenn: They don't realize how complicated of a process that it really is. In other words, let me tell you something. I'll give you an example. This is just my own opinion okay?

The Flaw of Remotely Monitoring Farms

Glenn:

People promote the idea that their farms can be remotely monitored. I don't think that you should run your business from Starbucks.

You follow me? I think that in order to be a farmer, you need to get up in the morning and go to your farm - whether it's in a container or a greenhouse or a warehouse or wherever it is.

You need to get yourself up to a level where you have a checklist every day of things that you do, and you do every one of those things. You follow me - so that you get to a point where in the first minute you walk in and you look around, you know what's going on. You follow me? A latte, and adjusting your humidity is nonsense.

UV:

Right. The issue with that is, from what I'm getting from what you're saying is, it may not all happen in one day, but slowly but surely you will get out of touch with what's going on.

Glenn:

You will get out of touch or get in touch. In other words if you understand that you're not ... Listen this is not a technology business. This is food production.

You follow me? That's really the bottom line. You need to put it in the right perspective and approach it for what it really is.

The Value of Data in Urban Farming

UV:

What do you think of the whole argument about collecting data on growing? A lot

of these companies that will, like as you mentioned, allow you to monitor stuff

remotely, will say there's a lot of value in the data of the growing and how

that they can use that data to make improvements in the future. How do you view

the value of that? Do you agree with that? Do you disagree with that? Do you

think that's a similar concept to ... It clashes with the idea of going every

day, or what do you think of the data aspect?

Glenn:

Honestly I haven't figured

that one out yet, for an honest answer. I don't know. I guess maybe as an old

timer in this industry, I look at things in a more traditional sense. I don't

feel that ... You know what I mean? I think that business should be run in a

cash flow positive manner.

Glenn:

I see young people today who's

business model is getting funding. That's their destination.

UV:

You're talking about specifically in the space or just in general?

Glenn:

I think in general. I don't follow other spaces. You know what I mean? I got to tell you. Somebody said it the other day on a trip overseas. They said, "The one thing we see about you, and based on everything you're doing and saying, is that you live this

business."

I'm involved with projects all over the world. I hear a lot of different perspectives. I speak to a lot of very intelligent people. I try to pay attention to everything that everyone says, take it seriously. Like I said, I pay attention to people, from young, old, in the business, not in the business. I try to compute it all, where it all fits in. I think that there's not enough focus on really building this as an industry.

Why Designing A Food System for 2050 in 2017 Is A Mistake

Glenn:

It's (urban farming) too fragmented. It's being approached from too many different levels, in too many different ways. I think that people to some degree, have lost sight in the fact that this is food production. I'll give you an example. People talk about the

population explosion and feeding the world in 2050.

Glenn:

I've got to tell you, my honest opinion is that ... First of all, we don't have any idea what people are going to be eating in 2050. There's a lot of technology involved with food production, meatless meat and egg-less eggs. There's a lot of stuff like that

going on. I believe that it's very possible that the solution to the food

crisis that's coming in 2050 ... They may not find the solution until 2049.

UV:

Yeah, that would not be surprising to me.

Glenn:

I think that the issues that need to be focused on right now are the issues that need to be focused on right now. I wouldn't use that as a motivation for building a business.

Rapid Fire Questions

UV:

A couple more short answer questions, rapid fire questions, what I like to call

them ... What are some specific crops that you see getting trendy?

Do you see any trends and stuff that people are asking you about or stuff that's getting more popular with restaurants or what not?

Glenn:

That's really a question of creativity. You know what I mean. Edible flowers are interesting- different, unique, gourmet, smaller quantities of higher value, more unique products. It also depends on again, on your market, on your economics, on your ... In other words, trendy is great. Can you make money with it?

UV:

(What about) Assuming that the trendy thing will touch a better margin or have higher demand?

Glenn:

Again, you can grow the trendy item. Can you sell it? Can you grow the trendy item in a vertical farm?

How much does it cost you to set up that facility to produce that product? You know

what I mean? This is all about business. It's all about economics. While something might be trendy, it may not be possible to produce in an efficient, profitable manner.

UV:

What's your favorite fruit or vegetable?

Glenn:

I don't know. What's my favorite vegetable? I would say spinach.

UV:

Spinach?

Glenn:

For growing or for eating?

UV:

I don't know, is it different?

Glenn:

Well growing ... Well for eating I like spinach because it's got a lot of different ways it can be prepared.

My favorite food for eating is probably fresh mozzarella. Very fresh mozzarella.

UV:

Just by itself or ...

Glenn:

Yeah.

UV:

All right well what about for growing?

Glenn:

My favorite product for growing is got to be just anything unique and unusual.

UV:

Okay, what's one example.

Glenn:

Minutina.

UV:

Minutina?

Glenn:

Yeah, minutina.

UV:

What is ... I'm not familiar

with that. What is that?

Glenn:

It's a green that originally comes from Europe. It's an addition to a salad, nice, crispy, delicious green that actually grows very well in an indoor environment.

UV:

Like arugula?

Glenn:

No, it's not. It's like ... I don't even know how to describe it. Look it up. It's a really interesting product. It's pretty rare and not easily available.

UV:

Okay, for sure. If people want to find out more about you or what you're working on now, what's the best place for them to go, just the website?

Glenn: Yeah, let them start at the website. The Growtainers' (Growtainers.com) website we keep up-to-date.

UV:

Thanks Glenn!

There Are Acres of Leafy Greens Inside These Shipping Crates On An Old St. Petersburg Junkyard

There Are Acres of Leafy Greens Inside These Shipping Crates On An Old St. Petersburg Junkyard

Friday, February 17, 2017 10:48am

ST. PETERSBURG — The would-be farmers bought three transoceanic refrigerated shipping containers, just a little dinged up, for $6,500 each.

Shannon O'Malley and Bradley Doyle had them hauled to a distressed property they purchased on Second Avenue S and painted them a vibrant green. The green of John Deere tractors and regimented rows of farm crops.

Because this is what they were building: A farm. Brick Street Farms.

The property had been used as a junk yard and asphalt dump for years. They hauled 57 loads of trash away on a 50-yard dump truck. It took eight months to clean and level the property before they could bring in their three slightly used shipping containers, two rows of picnic tables and a tall fence to discourage the lookie-loos.

You can't blame the loos for looking. This is Pinellas County's first and only commercial-size, indoor, hydroponic farm. These three upcycled containers have the ability to grow the equivalent of 6 acres of traditionally farmed leafy greens, herbs and edible flowers, using a minimum of water and no pesticides, herbicides or fungicides.

There is no dirt, there are no bugs and produce is delivered "plate ready" to the Vinoy, Brick & Mortar, Rococo Steak, Souzou, Stillwaters Tavern and BellaBrava, all in St. Petersburg. O'Malley aims to sell everything she produces within five miles of Brick Street Farms.

In this era of locavore fever, you can't get much more local than that.

Indoor, hydroponic, vertical farms are popping up in urban spaces around the globe. A dwindling amount of arable land due to industrialization, urban sprawl and climate pressures, coupled with population growth (9 billion people predicted on Earth by 2050!), has led many people to think creatively about our food supply.

Farmer Dave Smiles launched a 24,000-square-foot warehouse in Tampa in 2015 doing similar indoor vertical farming. In the same year in Newark, New Jersey a steel-supply company was taken over by a new indoor-agriculture company called AeroFarms, filling it with 70,000-square-feet of vertical kale, bok choi, watercress and such. In January, the New Yorker ran an exuberant article about the future of urban farming without soil or natural light.

But it's not easy: The nation's largest indoor farm, FarmedHere, which opened in 2013 in an abandoned warehouse in Bedford Park, Ill., closed its 90,000-square-foot facility in January. While CEO Nate Laurell didn't say precisely what had gone awry, it is clear that growing large enough to offset equipment, energy and labor costs proved tricky.

There are, O'Malley says, considerable costs to running the operation, but she declined to say what the farm's ongoing costs are.

"Hydroponics aren't new, this technology isn't new and all the technology we used is 'off the shelf,'" said O'Malley, 35, who recently quit her job at Duke Energy to work the farm full time. Doyle, 37, still works in information technology at Duke Energy.

Here's how it works. Each container is its own climate, kale in the one on the right, herbs in the middle one and heirloom lettuces on the left. There are three inches of insulation, plus reflective roofing to keep things cool, plus air conditioning (lettuces like it chilly, around 60 degrees). Everything is grown from non-GMO heirloom seeds, spending two weeks in the seedling area before each tiny root plug is transplanted to a white vertical tower, fitted into a mesh of recycled food-safe plastic.

The plant lives in the tower for three to five weeks, with recirculated water running down a felt wicking strip to feed the plants.

Strips of red and blue Phillips high-efficiency LED lights provide the sunshine (although because electricity is cheaper at night, the plants "daytime" is in the evening. From there, it gets complicated. Computers take readings of the plants every seven minutes — pH levels get adjusted, CO2 levels are tweaked, plant nutrients are measured in electrical conductivity and there's special air circulation for proper "plant transpiration."

According to O'Malley, this kind of indoor vertical farming uses one tenth the water of traditional farming and a tenth of the fuel (a traditional farm uses fuel to run the equipment and deliver product, for an indoor farm fuel costs are all electricity).

So how does all this high-tech food taste?

Glorious. Basil leaves as big as a catcher's mitt (well, a kid's mitt), rainbow chard and lacinato kale. Pea shoots and micro kohlrabi, arugula and red amaranth. The Vinoy is using a special mix of Brick Street lettuces in their salads and Rococo Steak will host a farm-to-table dinner at the farm on Feb. 25.

"It's a much more consistent product and a much cleaner product because it's not grown in dirt," says Jeffrey Jew, the executive chef at Stillwaters Tavern and BellaBrava. "It's super cool what they're doing. I know at the beginning Shannon was looking for chefs and restaurants to sell to. But now they're pretty much maxed out."

It's true. O'Malley and Doyle are looking to buy more containers, their goal seven across and stacked two deep. They don't envision doing a community supported agriculture subscription in which consumers buy a share of a farm, a popular model for more traditional farms. But they do sell direct to the public on Tuesday and Thursday evenings and Saturday afternoons.

They spend a lot of their time explaining what they're doing. No, they're not growing cannabis. No, it's not U-pick. No, it's not open to the public. And it's not a garden. It's not a laboratory.

It's a farm. You just have to think inside the box.

Contact Laura Reiley at lreiley@tampabay.com or (727) 892-2293. Follow @lreiley.

Ikea Releases Open Source Designs For A Garden Sphere That Feeds A Whole Neighborhood

If you’ve already constructed Ikea desks and chairs, then it’s time to take your skills to the next level.

This week Space10, an Ikea lab for futuristic, solutions-oriented designs, released open source plans for The Growroom, a large, multi-tiered spherical garden designed to sustainably grow enough food for an entire neighborhood. Hoping to help spur local growing and sourcing, Space10 made the plans available for free on Thursday.

02/17/2017 01:20 pm ET

Ikea Releases Open Source Designs For A Garden Sphere That Feeds A Whole Neighborhood

It doesn’t even require nails.

If you’ve already constructed Ikea desks and chairs, then it’s time to take your skills to the next level.

This week the company released open source plans for The Growroom, a large, multi-tiered spherical garden designed to sustainably grow enough food for an entire neighborhood. Hoping to help spur local growing and sourcing, Ikea made the plans available for free on Thursday.

All it takes to complete the 17-step, architect-designed DIY garden of your dreams is plywood, a visit to your local community workshop, rubber hammers, metal screws and some patience:

The garden’s “slices” are designed so that water and light reaches each level.

The Growroom is a brainchild of Space10, Ikea’s lab for futuristic, solutions-oriented designs. Though it’s intended mainly for use as a neighborhood garden in cities, you could also build one for your own backyard, a spokesman told HuffPost.

The Growroom doesn’t come in a flat pack like most Ikea products. Rather, users download the files needed to create perfectly-sized plywood pieces, using a local fab lab workshop for professional cutting. Then, they can assemble them using the free instructions online.

There are already plans to build Growrooms in Helsinki, Taipei, Rio de Janeiro and San Francisco, according to a press release. And if you’re up to the challenge, it could bring more locally-sourced food right to your hometown, Space10 writes:

Local food represents a serious alternative to the global food model. It reduces food miles, our pressure on the environment, and educates our children of where food actually comes from. ... The challenge is that traditional farming takes up a lot of space and space is a scarce resource in our urban environments.

The Growroom ...is designed to support our everyday sense of well being in the cities by creating a small oasis or ‘pause’ architecture in our high paced societal scenery, and enables people to connect with nature as we smell and taste the abundance of herbs and plants. The pavilion, built as a sphere, can stand freely in any context and points in a direction of expanding contemporary and shared architecture.

Why We Need Technology As The Key Ingredient In Our Food

When asked how food security and production can be improved in Africa, former Rwandan minister and current president of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) Agnes Kaliba, had one simple answer: “Access to technologies.”

Peter Diamandis, ContributorChairman XPRIZE

Why We Need Technology As The Key Ingredient In Our Food

02/17/2017 01:54 pm ET | Updated 15 hours ago

hen asked how food security and production can be improved in Africa, former Rwandan minister and current president of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) Agnes Kaliba, had one simple answer: “Access to technologies.”

Ms. Kaliba is exactly right. We are sitting at the cusp of an explosion in exponential technologies, which can be the most critically important ingredients to improve the health and quality of life for all humanity.

The World Food Programme (WFP), the largest humanitarian organization in the world, estimates that some 795 million people do not have enough to eat to maintain their health. Additionally, we have faced an unprecedented number of large-scale emergencies — Syria, Iraq and the El Niño weather phenomenon in Southern Africa. Just last month, WFP stepped up support for tens of thousands of displaced Syrians returning home to the ruins of eastern Aleppo City, providing hot meals, ready-to-eat canned food and staple food items such as rice, beans, vegetable oil and lentils. Like Agnes Kaliba in Nairobi, WFP has resolved that technology will help most rapidly in providing better assistance in emergencies and achieve a world without hunger.

Singularity University (SU), which I co-founded with Ray Kurzweil in 2008, is a benefit organization focused on using exponential technologies to solve our Global Grand Challenges. At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Ertharin Cousin, the Executive Director of WFP, announced a new partnership with SU for a Global Impact Challenge for food.

Our Challenge is soliciting bold ideas from innovators around the world on how to create a sustainable supply of food after the onset of a crisis. In this way, we can help vulnerable families support their own households and reduce their dependence on external assistance. Entries can range from concepts to implemented innovations. Shortlisted winners will be invited to a bootcamp at the WFP Innovation Accelerator in Munich to flesh out their ideas with WFP innovators. One team will be selected to attend an all-expenses-paid, nine-week Global Solutions Program at Singularity University at NASA Research Park in Silicon Valley.

Here are some examples of moonshot thinking – and how converging exponential technologies are already reinventing food:

- Vertical Farming: If 80% of our planet’s arable land is already in use, then let’s look up. The impact of technology in vertical farming is powerful. In addition to maximizing the use of land, we can use AI to control the exact frequency and duration of light and pH and nutrient levels of the water supply. Vertical farms using clean-room technologies avoid pesticides and herbicides, and the fossil fuels used for plowing, fertilizing, harvesting and food delivery. Vertical farms are immune to weather, with crops grown year-round. One acre of a vertical farm can produce 10x to 20x that of a traditional farm. And if roughly one-quarter of world’s food calories are lost or wasted in transportation, then let’s think local. The average American meal travels 1,500 miles before being consumed. Moreover, 70 percent of a food’s final retail price is the cost of transportation, storage and handling. These miles add up quickly. The vertical farming market was $1.1 billion in 2015, and projected to exceed $6 billion by 2022.

- Hydroponics and Aeroponics: Traditional agriculture uses 70 percent of the water on this planet. Hydroponics is 70 percent more efficient than traditional agriculture, and aeroponics is 70 percent more efficient than hydroponics. In times of war and natural disaster, there are no readily available food sources, so let’s think creatively on how we can grow food from — and in — the air.

- Bioprinting Meat: In 2016, it took 63 billion land animals to feed 7 billion humans. It’s a HUGE business. Land animals occupy one-third of the non-ice landmass, use 8% of our water supply and generate 18% of all greenhouse gases — more than all the cars in the world. Work is progressing on bioprinting (tissue engineering and 3D printing) to grow meat (beef, chicken and pork) and leathers in a lab. By bio-printing meat, we would be able to feed the world with 99% less land, 96% less water, 96% fewer greenhouse gases and 45% less energy.

- Shifting diets: Optimal health requires 10-20 percent of calories to come from protein. One example of innovative thinking comes from Africa, where farmers are installing fish ponds in home gardens, as the mud from the bottom of the pond also makes a great mineral-rich fertilizer. In the lab, scientists are investigating new biocrops.

This is just the beginning. If we are really serious about creating a vibrant ecosystem of sustainable food production, we need to be thinking exponentially and using technology to help create cost-efficient innovative solutions that can feed the world.

SGS Awards GLOBAL G.A.P. Quality Standard To Indoor Farming Company, INFARM

Berlin-based agricultural business INFARM has become the first indoor farming company to be awarded the GLOBALG.A.P. quality standard. SGS officially presented the GLOBALG.A.P. certificate at this year’s Fruit Logistica Trade Fair, in Berlin

SGS AWARDS GLOBAL G.A.P. QUALITY STANDARD TO INDOOR FARMING COMPANY, INFARM

February 14, 2017

Berlin-based agricultural business INFARM has become the first indoor farming company to be awarded the GLOBALG.A.P. quality standard. SGS officially presented the GLOBALG.A.P. certificate at this year’s Fruit Logistica Trade Fair, in Berlin.

INFARM designs and installs vertical farms in urban areas, helping them become self-sufficient in their food production, while eliminating waste and reducing the impact on the environment. As part of this, INFARM has installed “in-store farms” inside two supermarkets – one in the METRO Cash & Carry, in Berlin, and the other in Makro, in Antwerp.

INFARM’s “in-store farms” grow an assortment of herbs, leafy greens and salads, using light, water and nutrient resources from within the self-contained growing environment. The plants are cultivated and harvested within the shop in which they are sold. This reduces transportation costs and the associated food-miles.

This award is an important step forward for INFARM. Many supermarkets require a valid GLOBALG.A.P. certificate from suppliers of agriculture, horticulture and aquaculture products before foodstuffs can be offered for sale. The presentation of the certificate at the Fruit Logistica Fair is an acknowledgement that INFARM is operating according to globally recognized good agricultural practices.

SGS, as the world’s leading inspection, verification, testing and certification company, has plenty of experience of auditing to the GLOBALG.A.P. standard but, as Betina Jahn from SGS explains:

Usually vegetable farms or orchards are audited according to GLOBALG.A.P. Therefore, we first had to adapt the test criteria for the in-store farm. Our experts worked closely with the standard authority, FoodPLUS, to produce a reliable testing process. This can now be applied to all future vertical farming company audits.

SGS Agriculture & Food Services

SGS provides a comprehensive range of services to help manage risk, safeguard consumers, ensure correct storage and transportation, ensure quality and safety throughout the supply chain, and confirm compliance with complex legislation. Learn more about SGS’s Agriculture & Food Services.

For further information, please contact:

Betina Jahn

Head of Innovative Product Management

t: +49 4473 9439 0

Atlanta To Host Agriculture Conference

Atlanta To Host Agriculture Conference

- Leslie Johnson

- For the AJC

4:49 p.m Monday, Feb. 13, 2017 Metro Atlanta / State news

Relationships built at the inaugural Aglanta Conference on Feb. 19 could help the city meet its goals of bringing local healthy food within a half mile of 75 percent of all Atlanta residents by 2020, said the city of Atlanta’s urban agriculture director, Mario Cambardella.

Urban and controlled environment agriculture innovation will be featured during the conference, which will take place at Georgia Railroad Freight Depot.

The purpose of Aglanta is to assist in Atlanta’s growth as a central hub in the nation’s annual $9 billion indoor farming industry, the city said in an announcement. Participants will include restaurateurs, grocers, architects, entrepreneurs, technologists, business owners and urban farmers for networking, sharing of best practices and making partnerships. The conference will include workshops and lectures, and cover urban agriculture business models and technologies, with a focus on vertical and indoor farming.

Information: https://www.aglanta.org/

Loudon Greenhouse Looks to Reimagine Farming With Automated Growing

By DAVID BROOKS

Monitor staff

Sunday, February 12, 2017

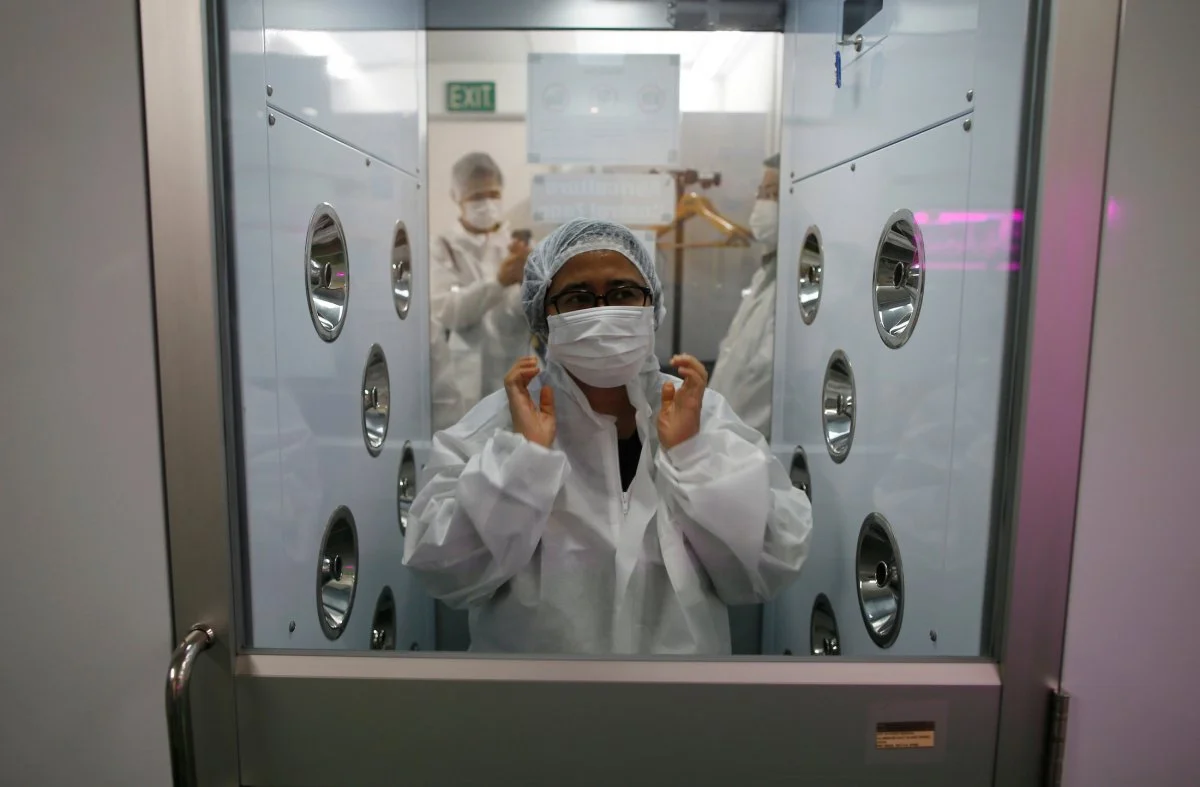

pecial clothing is often needed when you’re visiting a farm: Boots, gloves, hats, overalls, lab coats.

Lab coats?

“We wear lab coats in the greenhouse because this is where you could have the most contact with the plant material,” explained Henry Huntington, president and co-founder of the state’s most interesting new agricultural operation, the automated hydroponics greenhouse called Lef Farms in Loudon, as he helped a reporter and photographer put on protective garb – protective for the seedlings, not the people.

With coats, hairnets and gloves in place, Huntington and co-owner Bob LaDue pushed through the door from the operations center, where seven days a week machines carefully place tens of thousands of seeds into 40-foot trays modeled after rain gutters, and entered the 50,000-square-foot greenhouse that they hope will launch a bright new chapter in New Hampshire farming.

On this gray, snowy day, it is certainly bright in the literal sense, with hundreds of high-pressure sodium lights overhead going full blast to compensate for shortage of daylight coming through the glass.

“My goal is to make them think it’s June, every day. We’re feeding the plants photons,” said LaDue, who has been involved in greenhouse research and commercial operations for 20 years.

“We use as much natural light as possible since we don’t have to pay for that, and plan on about 80 percent of light coming from the sun over the course of the whole year,” he said. “Not on a day like today, though.”

A year’s production in less than a week

The bright lights in the vast open space gave the greenhouse the look of an airplane hangar, if you can imagine one with a floor that has been raised 5 feet and is made of salad greens.

How much salad greens? More than you can probably imagine.

LaDue said this 1 acre of hydroponics growing space will eventually produce 3,000 pounds of leafy greens, bagged and ready to be shipped to stores or restaurants, every 24 hours. After a few months of operation, Lef Farms (pronounced “leaf”) is running at about half speed as it tweaks the operation.

That’s a ton and a half daily of arugula, bok choy, mustard greens and lettuce, meaning that every day they expect to produce about one-third the annual production (depending on the crop) expected from an acre grown organically outdoors.

“We are very excited about it. This is the first large-scale farm of this kind designed for wholesale markets here in New Hampshire and the region,” said Lorraine Merrill, the state’s agricultural commissioner. “There have been proposals for this kind of production before that haven’t come to pass.”

Merrill said that indoor agriculture, with the promise of extending our growing season, can be an important part of the mix for state farming alongside traditional wholesale operations like dairy farms, smaller specialty farms, and direct-to-consumer sales via pick-your-own, farmers markets and community-supported agriculture projects.

“I really think one of the great strengths of New Hampshire agriculture is its diversity, and this adds to it. Diversity of types of crops and diversity of types of marketing channels – not putting all of our eggs in one basket,” she said.

The idea of farming indoors, with the aim of growing more produce on smaller plots that are closer to cities and can be harvested even during winter, is becoming realistic as technology improves. One Nashua family, for example, bought a “farm in a box” from the firm Boston Freight Farms and are raising greens for sale in a converted shipping container, with plants grown hydroponically (all the nutrients coming from water rather than soil) in rows of shelving, entirely dependent on light from LEDs.

Lef Farms isn’t quite that high-tech: It went with greenhouses and sodium lights for various cost and scale reasons. But this greenhouse is unlike any you’ve seen.

Greenhouse unlike most

Greenhouses have, of course, been part of New Hampshire agriculture for many decades. In fact, Huntington owns Pleasant View Gardens, which like Lef Farms has greenhouses built on a former gravel pit, where tons of flowers are grown a year. His experience there helped trigger the idea for Lef Farms.

“We have significant greenhouse productions of ornamental and flowering plants in New Hampshire, including D.S. Cole Growers and Pleasant View, two of the larger and most significant plant propagators in the country,” said Merrill.

What makes Lef Farms unusual is that it produces food crops and uses an extremely automated system that can plant, grow, harvest and bag the greens over a two-week growing cycle with little or no human labor.

Huntington and LaDue said this cuts labor costs – Lef Farms has a dozen full-time positions – and maximizes production. But they also say the precision of automation, in which the water used for hydroponics is fully recycled with its nutrients and fertilizers, reduces agricultural pollution from runoff compared to standard farms. The tightly controlled greenhouse, use of hydroponics and a fast growing cycle also greatly reduce the number of insect pests and the need for pesticides, as well as eliminating weeds and any resulting herbicides.

Whether it will be worth the reported $10 million investment remains to be seen. But they have plans to build several more greenhouses if all goes well, and they have town approval for up to 12 acres of operations.

Dirt put in gutters

Growing any crops starts with the soil. At Lef Farms, the soil has a brand name: Cornell Mix, developed at the university where LaDue did research for years. A mix of peat and vermiculite, it comes in 120-cubic-foot bales that double in size when decompressed and watered; specialized machinery from Finland distributes it carefully along the 40-foot-long gutters.

“A lot of the technology for this was developed in Scandinavian countries. They have so little light, the growing season is so short, and they’re trying to grow their own food; that has simulated their technology,” LaDue said.

Once loaded with this dirt, each gutter moves along a conveyer under a series of machines that drop in seeds; sometimes all of one species, sometimes a variety, although growing two species alongside each other is difficult, since they are harvested at the same time and thus must grow at the same rate, so that one species doesn’t shade out the other.

Each gutter then slides onto a huge pivoting arm that swivels and sends the chute through a hole in the wall into the greenhouse. This is done roughly 800 times every day – meaning that 800 other gutters are removed and harvested.

The gutter sits in darkness underneath the growing area for two days while the seeds germinate, before being pulled by on an enormous toothed belt up into the light. Over the next 14 to 19 days, depending on the crop, it will be pulled slowly from one end of the greenhouse to the other, roughly 300 feet, while the plants are fed by a constant stream of water containing a mix of micro- and macro-nutrients, made by blending various fertilizers.

“Bob’s kind of the mad scientist. He makes his own mixes,” Huntington said.

During this entire process, little to no human interaction will be required, although LaDue and others will be monitoring many factors – not just plants’ growth and health, but the building’s temperature, the total light as measured in moles (a unit you might remember from high school chemistry) of photons, its humidity and even its carbon dioxide level.

Even carbon dioxide must be balanced

That last factor is crucial, LaDue said. Plants breathe in carbon dioxide and during the winter, when the greenhouse lacks natural airflow through the heavily screened windows, they would use up most of the CO2, stunting growth, if it weren’t replaced.

Lef Farms produces CO2 as a byproduct of the gas-fired heaters, and even produces more than natural levels to boost growth, which enables them to cut back on lighting, one of their biggest costs.

“Supplement CO2 is another avenue to reduce supplemental lighting – we’re always trying to turn these lights off,” LaDue said. On a winter’s day, byproduct from heat can “save five to six hours of supplemental lighting.”

Lighting has also been a source of irritation to neighbors, who have complained to town officials about the brightness of the glow at night from this new presence in town. Lef Farms has said it will improve its use of shades to reduce the excess.

Getting the plants cold fast

Eventually the plants make it to the far end of the greenhouse, where conveyors transfer them, plants still growing, directly into the cooler, which is larger than some warehouses. Only inside the cooler do they get “a haircut” from automated blades, with salad greens automatically sorted on conveyer belts and dropped into a machine that puts them inside plastic bags. That’s all without human help – at least in theory; LaDue said the system is still being tweaked.

Bringing plants into the cooler while they are still growing is a key to maintaining freshness, said LaDue, who compared it to traditional harvesting.

“On most operations, you get them cut, it goes into bins, people are mixing them by hand. That’s not good,” he said. “The faster you get them cold, the better.”

And that’s not counting the benefit of being closer to our tables and stores. “Alternative to West Coast-grown greens” is a phrase that shows up a lot in their promotional material. LaDue claims that this system gives Lef Farms greens sold to retailers “shelf life like they’ve never seen before,” justifying a premium price.

Plenty of people around the state and the region will be watching, both to see if that belief holds up and to see what it means about our ability to feed ourselves in New England.

“I would expect we will probably see further developments, variations on this theme – in lots of different ways,” said Merrill, the agriculture commissioner. “Farmers are creative and resourceful; they’re always finding ways to make technology work for them.”

(David Brooks can be reached at 369-3313 or dbrooks@cmonitor.com or on Twitter @GraniteGeek.)

Light glows inside the Lef Farms greenhouses in Loudon last week. Elodie Reed photos / Monitor staff

Bob LaDue walks between growing salad greens at Lef Farms in Loudon last week. Elodie Reed—Monitor staff » Buy this Image

Lef Farms Vice President Bob LaDue explains how the Loudon greenhouse operation grows baby greens year-round last week.

Lef Farms President Henry Huntington walks past one of the many boxes that controls the company’s automated hydroponic growing system.

The Vertical Farm: A Chat with Dickson D. Despommier, Ph.D.

By the year 2050, nearly 80% of the earth’s population will live in urban centers and that number will have increased by about 3 billion people in the interim – a big challenge and opportunity to feed. One emergent model is indoor farming, aka, vertical farming

The Vertical Farm: A Chat with Dickson D. Despommier, Ph.D.

February 10, 2017

By the year 2050, nearly 80% of the earth’s population will live in urban centers and that number will have increased by about 3 billion people in the interim – a big challenge and opportunity to feed. One emergent model is indoor farming, aka, vertical farming.

Columbia professor Dickson D. Despommier, Ph.D., (now emeritus) at Columbia University Medical School authored “The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century,” published in 2010, and is credited with mainstreaming the term vertical farming.

At its most basic, the process refers to growing crops in vertically stacked beds in a controlled environment, without natural light or soil as Despommier describes here:

Sustainable Brands spoke with Despommier about the adoption of this model today.

“The idea has not been in the public domain for more than ten years,” he said. “It requires a heavy investment and creativity to invent the methods and to create social buy-in. It’s been quite rapid depending on how you define it. The idea smoldered in Japan for ten years and then Fukushima occurred and countries went ballistic as the people of Japan were not buying food grown there thinking it was contaminated.

“An indoor food industry was a solution and the Japanese government supported it. Indoor farming spread in the country and Toshiba and Panasonic were enlisted by the government of Japan to become leaders in indoor farming. These two giants had some downsizing in their own factories due to competition in other sectors that affected their ability to keep pace with the growth of electronics industry. Warehouses not being used were converted to indoor growing systems. Japan has embraced indoor/vertical farming.

“Singapore lacks land but is rich. They want to control food safety and sovereignty. Before urban farming there were no options. Panasonic has large indoor farms in Singapore and six others are being built to fulfill expanding demand.

“Taiwan has 50 vertical farms. They have little land to farm on a mountainous island with a tropical climate. Korea built and experimental farm in 2010 and the Mayor of Seoul announced in the last six months that every building can accommodate an addition for vertical farming. There are 30 million people in Seoul now and they’re importing foods but want to be in control.

“Here in the US, farmers in the Midwest have a winter problem and can’t deliver fresh greens as easily – fresh greens as in picked today – so what arrives is three weeks old and 40% is thrown out from refrigerators as it rots.

“There are 30 or so indoor farms centered around Chicago in abandoned warehouses – many no higher than a single story, single greenhouses – but they must be higher than one story to qualify as vertical farms. Companies like Sears, Kmart and Walmart who have such buildings can get tax breaks to repurpose them for farming but these stories don’t make the radar screen of the public, they don’t usually make the headlines.”

Despommier and his students figured out that a space like Floyd Bennett Field, former airport-turned-park on Jamaica Bay in Brooklyn, could provide enough vegetables and rice to feed every person living in New York City in the year 2050 – along with medicinal plants, and herbs and spices for five different traditional cuisines.

SB asked is this an extensible model?

“Every situation for establishing an indoor farm is predicated on supply and demand,” Despommier said. “Most cities in the US north of the Mason Dixon - the weather division – are going to run out of fresh green vegetables in winter.

“It’s amazing how important they are to restaurants and even fast-food chains as accoutrements – it’s a huge output that needs a reliable source and from that perspective, every city has space but a different set of priorities. You have to be clever in dealing with real estate agents etc.”

“Empty warehouses are a prime target for the establishment – every Mayor has relics from industrial movements and habits developed by Kmart and Costco and Sears. Corporations overextended. Starbucks has gigantic warehouses out of reach of a city for property taxes, several thousand sq. feet, intergowing vegetables like tomatoes and green beans. They’re not hard to grow but you need demand.”

Since your book was published, what changes do you perceive in consumer and business attitudes towards sustainable agriculture?

“There’s been a gradual transition from the Currie and Ives view of farming of the 1910’s and 20’s and then the 30’s drought trashed the Midwest, followed by WWII – and then, as depicted in the “Grapes of Wrath,” a favorite book, what happened next was a generation displaced by climate change who moved to CA. How ironic that CA is in its seventh year of drought and even the weather coming isn’t going to help as it’s coming in the wrong place to solve the problem. The problem continues.

“Moving to dairy farms, out of CA’s total $70 billion agricultural initiative, half is dairy farming. Dairy farmers in Europe are growing food for cattle indoors. No bales of hay, real cow food, and they grow it on demand, enough to raise 300 head of dairy cattle on oats barley grain from plants that stand just six inches tall with a tangled root system – crops in trays – which is then inverted and the root system falls out and that cattle feed is the Häagen-Dazs or Jerry Garcia flavor for them, they love it. You don’t need a lot of room and continuous growth for six weeks yields enough for 300 head of cattle.”

Despommier is hopeful we’ll get it right before we’ve exhausted the planet’s patience and resources but cautions, “humans are born with capacity to creativity and environmental destruction. We do it creatively, use our creativity in ways that damage the planet. Eventually the reality that what we’re doing with environmental encroachment will sink in.”

Today in the U.S., there are vertical farms in Seattle, Detroit, Houston, Brooklyn, Queens and near Chicago.

AeroFarms in Newark, New Jersey is one of the largest with a main crop of

baby salad greens, “vast armies of little watercresses, arugulas, and kales waiting to be harvested and sold. For more than a year, all the company’s commercial greens came from this vertical farm.”

“It’s still hovering at lever of industrial radar screens,” said Despommier, “but it’s a big industry waiting to happen – and the grow-light industry is huge, all that equipment, but it needs to be cobbled together.”

The building now leased by AeroFarms used to be Grammer, Dempsey & Hudson headquarters in 1929 when in an average year, the steel-supply company shipped about twenty thousand tons of steel. When the vertical farm there today is in full operation, soon, they expect to ship more than a thousand tons of greens each year.

Sheila Shayon, President of Third Eye Media, is a senior media executive with twenty five plus years in television and new media including expertise in programming, production, broadband, start-up models, creative and branding strategies, digital content and social networking.

City of Atlanta to Host inaugural “Aglanta Conference”

The City of Atlanta will host its inaugural “Aglanta Conference” to showcase urban and controlled environment agriculture innovation in the City of Atlanta

City of Atlanta to Host inaugural “Aglanta Conference”

February 10, 2017 Valerie Morgan Local News, more news0

The City of Atlanta will host its inaugural “Aglanta Conference” to showcase urban and controlled environment agriculture innovation in the City of Atlanta.

The Mayor’s Office of Sustainability has partnered with Blue Planet Consulting, a firm specializing in urban agriculture projects, to bring together restaurateurs, grocers, architects, entrepreneurs, technologists, business owners and urban farmers to network, share best practices and establish partnerships. The conference will take place on Feb. 19 at the Georgia Railroad Freight Depot, and aims to help foster Atlanta’s growth as a central hub in the nation’s annual $9 billion indoor farming industry.

“We are excited about the inaugural Aglanta Conference and expect more than 200 industry leaders to attend,” said Mario Cambardella, the City of Atlanta Urban Agriculture Director. “The City of Atlanta recognizes the positive health and community outcomes of urban agriculture and will use this conference to foster relationships and partnerships which can ultimately help us meet our goals of bringing local, healthy food within a half-mile of 75 percent of all Atlanta residents by year 2020.”

In December 2015, Mayor Kasim Reed appointed Cambardella as the city’s first ever Urban Agriculture Director. Atlanta is one of a few cities in the nation with an Urban Agriculture Director, dedicated to working on food access generating policy, advocacy, and development. The Aglanta Conference will create an environment for participants to engage with a local, national and international audience. Through workshops, lectures, and networking sessions, the conference will cover issues across the spectrum of urban agriculture business models and technologies, with a particular focus on the emerging field of vertical and indoor farming.

During the conference, the Mayor’s Office of Sustainability will spotlight local champions already doing incredible work growing food as means of ecological restoration, social cohesion, cultural preservation, economic development and biopharmaceutical development.Partners for the conference include the Georgia Department of Economic Development, Georgia Power, Indoor Farms of America and Tower Farms.

To learn more about the conference or to register, visit: https://www.aglanta.org/

Buy Infinite Harvest's Greens at Nooch and Company Headquarters

Denver-based vertical farm Infinite Harvest has big plans to take its produce-growing capabilities to outer space. In the meantime, it could help a lot of people here on Earth

Buy Infinite Harvest's Greens at Nooch and Company Headquarters

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2017 AT 5:48 A.M.

BY LAURA SHUNK

You can now buy Infinite Harvest's Bibb lettuce for use in salads at home.

Denver-based vertical farm Infinite Harvest has big plans to take its produce-growing capabilities to outer space. In the meantime, it could help a lot of people here on Earth. As we reported in our feature story about the company last week, it grows some really tasty lettuce and microgreens.

At the time, you could only find Infinite Harvest products at local restaurants, tucked into salads and sprinkled as garnish on finished dishes or cocktails. But now the company has introduced two ways to purchase its produce for your own home-cooking purposes.

RELATED STORIES

Infinite Harvest has started supplying Nooch Vegan Market, a small retail shop at 10 East Ellsworth Avenue. At the moment, that store is just stocking Bibb lettuce, but the Infinite Harvest team says it may eventually bring on microgreens, too.

If it's microgreens you're after, you're in luck: Starting this weekend, Infinite Harvest will also sell to consumers directly out of its warehouse at 5825 West Sixth Avenue, Frontage Road North, Unit 3B in Lakewood. It's offering fresh-cut living Bibb lettuce plus two-ounce packages of thirteen different varieties of microgreens, including Genovese basil, micro-arugula and micro-pea tendrils.

While the warehouse store will be open from 8 a.m. until noon on Saturday and Sunday, you'll need to order in advance: E-mail info@infinite-harvest.com with your list and specify a pick-up time during the open window. Lettuce is $4 per head, while microgreens are $9 per package; Infinite Harvest requests a $12 minimum order.

If shelf life is a selling point for you, know that my Bibb lettuce lasted nearly two weeks in my fridge, and I imagine my microgreens would have, too, had I not eaten them within, like, sixteen nanoseconds.

If you'd rather try Infinite Harvest's produce in a composed dish, many restaurants around town are using it. Here are the most consistent buyers:

American Grind at Avanti, The Way Back, Jax Fish House, Grind Kitchen + Watering Hole, Il Porcellino, Blue Agave Grill, Brasserie Ten Ten, STK Denver, Machete, Ocean Prime, Shells and Sauce, Cerebral Brewing, Washington Park Grille, Edge at the Four Seasons, Ameristar Casino (Black Hawk), Mackenzie’s Chophouse (Colorado Springs), Odyssey Gastropub (Colorado Springs), Locality (Fort Collins) and 4th Street Chophouse (Loveland).

The Future Of Food Will Be Skyscrapers Filled With Plants

Milan is full of unusual sights. As the most populous city in Italy, and its main financial and industrial center, it’s a riot of color and design. But amid the skyline is a building that even for Milan is strange: The Bosco Verticale, or Vertical Forest, a skyscraper encircled with trees, finished in 2014.

The Future Of Food Will Be Skyscrapers Filled With Plants

02.08.17

Milan is full of unusual sights. As the most populous city in Italy, and its main financial and industrial center, it’s a riot of color and design. But amid the skyline is a building that even for Milan is strange: The Bosco Verticale, or Vertical Forest, a skyscraper encircled with trees, finished in 2014. The building was designed by acclaimed architect Stefano Boeri, and — if everyone from marijuana growers to Chinese investors get their way — will soon be as recognizable to urbanites as glass and steel towers are now.

Why? As cities expand, they destroy farmland, pump out smog, and fail to produce food. Parks, community gardens, and other green spaces can only do so much, and many foresee demand for food and the strain of climate change as an imminent danger. At the same time, we’re increasingly eager to know more about what we eat and where it’s coming from, and finding that information lacking. More and more people understand that everything we eat has a “footprint” and that the further your food travels, the more ecological damage it causes.

At the same time, as food-producing California faces water shortages that not even record precipitation can reverse, and climate change affects farmland across the world, shipping food from water-rich regions has become a vital necessity. Simply put, both consumer demand and environmental struggles mean that cities want their farms as close as possible to the populace, producing as much as possible (with as little water loss as possible), and while helping mitigate the pollution.

It’s a tall order. Literally.

Enter the vertical forest, like the afore mentioned building in Milan with more already in the works in Lausanne and Nanjing. The idea is simple: cities need more secure food supplies, more oxygen and to expand upward before gobbling up the land around them, so why not wrap skyscrapers in terraces that offer both, and build giant, towering farms that can feed thousands? The idea is undeniably ambitious, and so far, it’s little more than a proof of concept. But the concept works, and an unlikely industry is offering a path to expand it, thanks to a decision made thirty years ago.

In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan ordered law enforcement to begin helicopter flights that sprayed fields of marijuana with herbicide. The result? Marijuana operations began experimenting with hydroponics. Hydroponics are complex systems that allow farmers to grow plants indoors without soil. Instead, the plants are suspended in paper or mesh (or coconut husk) while a nutrient solution flows through the roots. Grow lights, powerful panels that turn out a replacement for sunlight, are used to offer the energy plants need to grow, with the result being an indoor, water-powered garden.

The hydroponics industry had plenty of other, more legal pioneers, such as the endless acres of Canadian hydroponics operations, but it was marijuana growers who worked on small, productive operations, and that expertise may be crucial to making vertical farms work.

Rick Byrd of PureAgro points out there are benefits well beyond just cutting down on fossil fuels: Vertical forests can deliver more than one harvest a year. As they’re indoors, there’s less of a pest problem, meaning less need for pesticides. And, with space at a premium, hydro operations can be build up, rather than having to grab for land.

These are expensive ideas, but marijuana — in the midst of a mega boom — means that growing operations can pioneer the technology, and then drive down the price to the point where you can grow anything with the same tech.

Byrd may find himself beaten to the punch by scientists, though. MIT recently debuted the Food Computer, an open-source system of computers and robotics that allows users to develop a “profile” for each plant they want to grow. Currently about the size of a shipping container, MIT’s team can see warehouse-sized facilities churning out specific types of food. With the robots doing the hard work, farming would be as simple as punching in the numbers and keeping an eye out for pests.

Hydroponics is not without its challenges. The nutrient solution, for example, is essentially pollution itself, and either needs to be reused or properly processed — although a well-run vertical farm offers better water management and control. Grow lights require enormous amounts of power, even with electron-sipping LED technology rapidly improving. And in a fit of irony, the plants outside these towers will need to be chosen carefully, as they might otherwise contribute to climate change.

But as a solution to a growing problem, vertical forests show that we should grow upward, not outward. Perhaps one day, the fields of the midwest will be filled with skyscrapers full of food, 50 stories tall, vastly increasing the available growing space.

Panasonic's First Indoor Farm Grows Over 80 Tons of Greens Per Year — Take A Look Inside

Panasonic may be known for its consumer electronics, but the Japanese company is also venturing into indoor agriculture

Panasonic's First Indoor Farm Grows Over 80 Tons of Greens Per Year — Take A Look Inside

Panasonic may be known for its consumer electronics, but the Japanese company is also venturing into indoor agriculture.

In 2014, Panasonic started growing leafy greens inside a warehouse in Singapore and selling them to local grocers and restaurants. At the time, the 2,670-square-foot farm produced just 3.6 tons of produce per year. The farm's square footage and output have both more than quadrupled since then, Alfred Tham, the assistant manager of Panasonic's Agriculture Business Division, tells Business Insider.

Panasonic's greens are all grown indoors year-round, with LEDs replacing sunlight. The growing beds are stacked to the ceiling in order to achieve a higher yield in the limited space.

Take a look inside.

The Future of Food - Community Development Field Trip

The Future of Food - Community Development Field Trip

Food and agriculture endeavors that focus on community development in cities -- from community gardens and urban farms to workforce development programs -- play an essential role in enhancing food security, educating citizens about where there food comes from, and strengthening food equity.

To learn firsthand about the impact of community development ventures on the future of food, Seedstock has organized the 'Future of Food – Community Development Field Trip’. Scheduled for March 17, 2017 in Los Angeles, CA, the field trip will include lectures from experts in the fields of community gardening, urban farming, and food justice, and visits to the following sites:

1. L.A. Kitchen - Founded by Robert Egger in 2013, L.A. Kitchen is located in a 20,000 sq. ft., two–level processing kitchen, in NE Los Angeles. L.A. Kitchen operates Strong Food, a wholly owned, for-profit subsidiary that hires training program graduates and competes for food service contracts, with an emphasis on opportunities to serve healthy senior meals. By purchasing and reclaiming cosmetically imperfect fruits and vegetables, which would otherwise be discarded, and using them to train and create culinary jobs for unemployed men and women, L.A. Kitchen makes scratch-cooked, healthy meals for the community.

This tour will sell out. Discounted Early Bird Special Tickets are available for a limited time here: http://seedstockfieldtrip.eventbrite.com.

2. Edendale Grove Parish Garden is part of the Seeds of Hope program, which is a ministry of the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles that seeks to help congregations, communities, and schools turn unused land into productive gardens and orchards to provide healthy and fresh food in areas of need across the county. Edendale Grove farm is situated on a previously vacant lot next to the Cathedral Center of St. Paul in Echo Park. The lot has been transformed into a parish garden that supplies fresh produce to local families as well as the essential ingredients to create sacramental oil and bread for the church.

This tour will sell out. Discounted Early Bird Special Tickets are available for a limited time here: http://seedstockfieldtrip.eventbrite.com.

3. Lavender Hill Urban Farm - Lavender Hill is a key project of the Los Angeles Community Garden Council, which manages 40 community gardens in Los Angeles County. Comprised of four and half acres of land, Lavender Hill Farm is located alongside the 110 freeway near Chinatown in Los Angeles, directly behind the Solano Canyon Community Garden. It was launched to provide meaningful work for ex-cons, former addicts, and at-risk teenagers.

To purchase early bird tickets, please visit: http://seedstockfieldtrip.eventbrite.com

A farm-to-fork lunch will be hosted and prepared by the staff at

Select Confirmed Speakers include:

- Tim Alderson - Executive Director of Seeds of Hope

- Julie Beals - Executive Director of the Los Angeles Community Garden Council

- Robert Egger - Founder and CEO of L.A. Kitchen

For sponsorship opportunities, please send inquiries to: sponsor@seedstock.com

The Future of Urban Farming Could Be In A Shipping Container

The Future of Urban Farming Could Be In A Shipping Container

Posted: Mar 21, 2017 11:12 PM CDT | Updated: Mar 22, 2017 1:17 AM CDT

By Jeff Van Sant | GLENDALE, AZ (3TV/CBS 5) -

Urban farming has exploded in popularity over the last few years.

People are becoming more conscious of organic foods and wanting to take charge with what they put in their bodies.

One great way is to create an urban farm in your backyard. Most of us would envision a sort of big garden but one Glendale couple has taken it a step into the 21st century by farming indoors inside an old shipping container.

Heather and Brian Szymura run Twisted Infusions. They farm in a unique way called vertical organic hydroponics. They grow several different kinds of lettuce and kale.

They use an old shipping container that has been converted into an indoor farm. The containers are re-made by a company called Freight Farm.

What's amazing about the containers is that they create whatever atmosphere fits the farmer. All of the controls from the air, water and CO2 levels can be controlled at the touch of an iPad.

The containers are all about creating a sustainable farm and cut down on the use of space. Almost everything can be recycled including the water. Twisted Infusions says they only use about 15 gallons of water a day. Think about that. It's less than your average shower.

The shipping containers run about $85,000.

Copyright 2017 KPHO/KTVK (KPHO Broadcasting Corporation). All rights reserved.

Heather and Brian Szymura are growing vegetables inside a shipping container

The containers are re-made by a company called Freight Farm

All of the controls from the air, water and CO2 levels can be controlled at the touch of an iPad.

The shipping containers run about $85,000.

Women In CEA Startups

Interest in furthering the development of controlled environment agriculture (CEA) is propelled forward by the idea that we can create real solutions to some of humanity’s basic needs: like growing nutritious food. By bringing farming under cover, be that in a hoophouse, greenhouse or vertical farm, we have found ways to closely monitor and manipulate growing conditions

Women In CEA Startups

Meet 4 female trailblazers raising the bar in controlled environment agriculture through entrepreneurship.

January 25, 2017

Cassie Neiden

Interest in furthering the development of controlled environment agriculture (CEA) is propelled forward by the idea that we can create real solutions to some of humanity’s basic needs: like growing nutritious food. By bringing farming under cover, be that in a hoophouse, greenhouse or vertical farm, we have found ways to closely monitor and manipulate growing conditions. These efforts have resulted in extended growing seasons — all while improving food access, flavor and local economies.

But CEA’s improvements do not stop there. As this dynamic, ever-changing industry continues to adapt and evolve, new ideas coming to the forefront aim to solve challenges and streamline systems. Unsurprisingly, many of them are coming from women, who asking the simple question: Why not?

Why not integrate greenhouse data into a user-friendly platform? Why not ask if an abandoned garden needs a revamp? Why not grow clean, healthy greens in the comfort of a home? Why not make a greenhouse three stories tall?

On the following pages, we feature determined, inspiring women who are finding CEA success through their innovations and leadership.

Allison Kopf, Founder & CEO, Agrilyst

DATA-DRIVEN: Kopf put together a team of highly skilled data scientists and engineers to form Agrilyst, an intelligence software platform for indoor farmers, in 2015. Agrilyst utilizes algorithms to track and record data from sensors throughout the greenhouse to help growers better understand their operation’s metrics to improve plant quality and output.

Since the company’s conception, Kopf and her 10-member team have nabbed first place in TechCrunch Disrupt’s prestigious technology startup competition, raised more than $1 million in investments for development, secured customers in five countries, and in January, launched Agrilyst Reporting, which helps growers curate their own customized data sets.

“We’re helping [growers] visualize data like never before,” Kopf says. “Big data is just a [phrase], but having insights and having meaningful visualizations is important to growers, so we’ve spent a lot of time focused on that.”

BRIGHT IDEA: Based in the startup central, NYC, Kopf has experience in helping to build companies. Before founding Agrilyst, she spent four years as the Real Estate and Government Relations Manager at BrightFarms, a hydroponic grower and greenhouse builder in New York. She was one of the first employees at the company back in 2011.

“It was a really easy jump for me to say, ‘I want to be in this startup world, and I want to do something that I believe in and work alongside a team on something that’s a big problem that’s solvable by us,’” she says.

In fact, much of the idea for Agrilyst came from her time at BrightFarms. “When I was on the operating side, my job was to essentially solve problems as they came up. And that was really challenging to do because we had fragmented data systems,” she says.

Essentially, climate control systems and other technological advances provided data to the growers — but they had no comprehensive way of gathering and analyzing it. “I said, ‘That’s it. We can’t do this anymore. We have to find a way to log this data somehow,’” Kopf says. “I can build this platform to integrate this data and build a team of people smarter than me to get [growers] insights into that data.” And Agrilyst was born.

Kopf's startup advice is to make yourself an expert in your field, but don't go it alone. "It wastes time and money, especially in this space," she says.

LEVELED OUT: Part of Kopf’s success in the male-dominated technology space is due to her mindset. She was the only woman in her physics class in college; she’s spearheaded a legislative campaign; and also fearlessly pitched her business model to venture capitalists. No matter the space she’s in, she refuses to be intimidated based on her gender because she simply doesn’t factor it in.

“The way that I approach it is that I’m there because I’m the person to do this,” Kopf says. “I presented the company that I had built because I was the right person to build this company. This [is] the thing I was put on this earth to solve. That’s the way I operate … I’ve made myself the expert in the thing I’m doing, and that’s the only [way] you can have confidence standing up there and presenting something that’s yours, in my opinion.”

BORN LEADER: While Agrilyst takes up much of Kopf’s time, she hasn’t shied away from additional professional leadership opportunities. She’s an advisor for a nonprofit to promote young women’s involvement in tech called #BUILTBYGIRLS, as well as a mentor for Square Roots Urban Growers, a hydroponic vertical farm builder. Kopf was also named Entrepreneur of the Year by Technical.ly Brooklyn, and Changemaker of the Year by the Association for Vertical Farming earlier this year.

So it’s no surprise that her favorite part of starting a business is building a team.