Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Organic Entrepreneur in Ripon Focuses on Fresh

Organic Entrepreneur in Ripon Focuses on Fresh

Nate Beck , USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin 8:53 a.m. CT Aug. 22, 2016

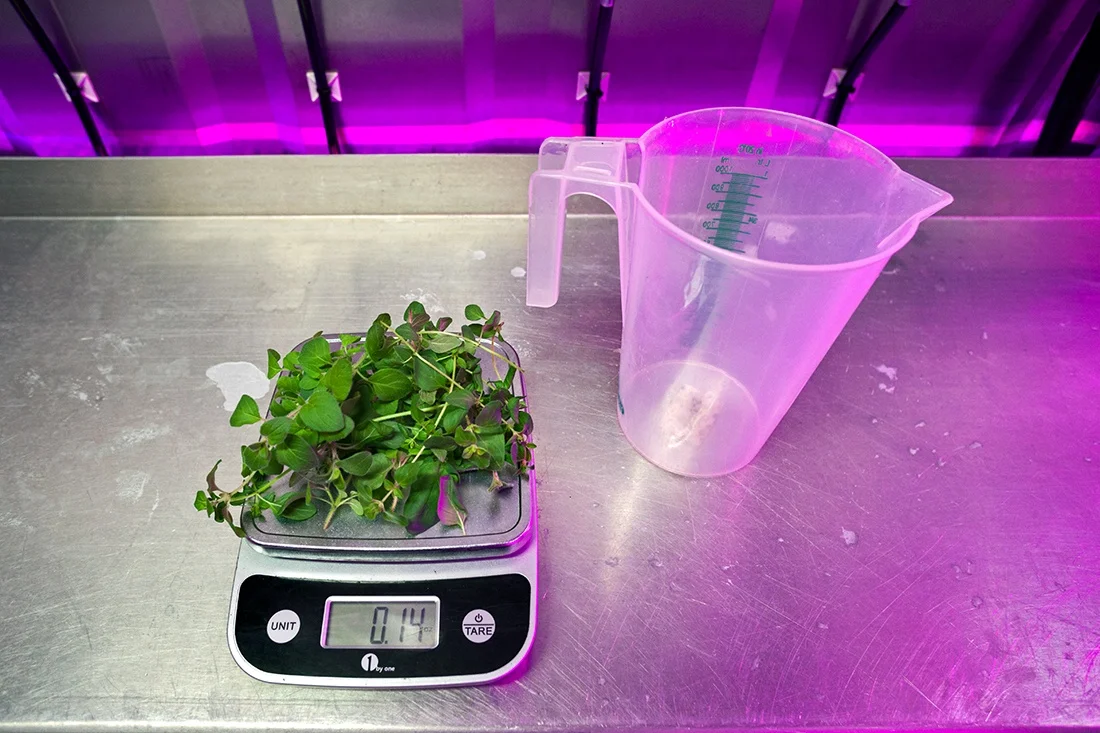

Brian Ernst, owner of Ernessi Organics in Ripon, grows microgreens and veggies in his basement urban farm.(Photo: Nate Beck/USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin)Buy Photo

RIPON - In a basement below Bluemke’s appliance shop in downtown Ripon, thousands of vegetables sprout every week, bound for the aisles of one of northeast Wisconsin’s biggest grocers.

Since it was founded two years ago, Ernessi Organics has grown to supply its greens to 16 grocery stores, including 13 Festival Foods locations across Wisconsin. Basil, amaranth and other veggies grown here can be found nestled in entrees at The Roxy, Primo Italian Restaurant and other eateries in the Fox Valley.

Ernessi’s fast success turns on consumer appetite for fresh and wholesome ingredients prepared locally, and retail’s efforts to catch up.

Ripon approved a $60,000 loan to the company last summer that helped pay for custom-made lights and other infrastructure. With a facility that produces 3,000 packages of fresh greens weekly, Ernessi can hardly keep pace with demand so the company recently launched an expansion that will double how much it can produce this fall.

So what does it take to start a blossoming company like this?

It’s about charging forward, head down, at the hurdles before you, said company founder Brian Ernst. “As an entrepreneur, you see a vacuum in the market and you go for it,” he said.

A geologist educated at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, Ernst found work after college at a large company, but soon tired of the work. He began tinkering with hydroponics, the process of growing plants without soil, in his basement. Ernst and his friend Tim Alessi began testing how light affects the growth of herbs and vegetables, settling on a combination that tricks plants into thinking that spring has just sprung, causing them to sprout faster.

In 2014, Ernst’s employer laid him off. Rather than shopping his resume around to other companies, Ernst, at the urging of his wife, decided to turn this hydroponic hobby into a company.

At Ripon's Ernessi Organics, a variety of microgreens and vegetables grow in a basement urban farm. (Photo: Nate Beck/USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin)

But to do that would require cash.

So he and his wife sold everything they could: TVs, furniture, Ernst’s 401(K), all of it. With $10,000, the company was born, three months after he and his wife had their second child, while raising a 3-year-old.

So, no. Starting a business isn’t about safety.

The draw about this breed of farming is that it can be done anywhere. Inside the Ernessi operation, floor-to-ceiling steel racks support rows of budding plants on trays. One four-foot-by-eight-foot palate of veggies yields 576 plants in just 35 days, using much less water than a typical farm would. And here in Wisconsin, with its brutal winters, there’s no end to Ernessi’s growing season.

This latest expansion will allow the company to double its production and deliver its plants faster, with a new refrigerated truck. The company’s business is built on supplying plants to grocery stores or restaurants less than 24 hours after they are cut, for the same price as producers elsewhere.

To meet this, Ernst said expanding the company to different parts of the Midwest will likely require him to franchise the company. These veggies are no longer local, he said, if they travel more than two hours to their destination. So in the next five years, Ernst hopes to start a location in Duluth, Minnesota, for example, that would supply produce to grocery stores and others in that market.

For now though, Ernst is focused on the company’s expansion, and growing new products, lettuce, gourmet mushrooms and more. He plans to use leftovers from the beer-making process at nearby Knuth Brewing Co., a Ripon-based brewery, for the soil to grow mushrooms. Lately, he’s been wheeling a blue plastic drum two blocks up Watson Street to the brewery to collect the stuff.

“If you have the drive, starting a business is not a hard decision,” Ernst said. “Any entrepreneur will tell you, there’s never a good time to start a business.”

The harder you work, the smaller these hurdles seem.

Reach Nate Beck at 920-858-9657 or nbeck@gannett.com; on Twitter: @NateBeck9.

At Ripon's Ernessi Organics, a variety of microgreens and vegetables grow in a basement urban farm. (Photo: Nate Beck/USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin)

A Former Corporate Banker Plants New Roots in Urban Farming

Apr 11, 2017

A Former Corporate Banker Plants New Roots in Urban Farming

By MOLLY SMITH

Photography By LYNDA GONZALEZ

Reporting Texas

Alejandra Rodriguez Boughton carries seedlings that are ready to transplant. She founded La Flaca, an organic urban farm that grows rare produce for local needs. “Most people that live in cities don’t know a farmer, so people are always shocked when I tell them what I do for a living,” she said. Lynda Gonzalez/Reporting Texas

Like many graduates of MBA programs, Alejandra Rodriguez Boughton starts her day around 6 a.m. But she isn’t up early to check the financial headlines. Instead, the day’s weather is her primary concern.

Rodriguez Boughton’s office is a small two-bedroom house on a quiet cul-de-sac in Southwest Austin. There’s little shade or cover in the yard where she spends most of her work day, converting what once was grass into farmland.

Raised beds line the side of the house, where she has planted radishes, beets, peppers and bananas. Planters behind the house contain edible flowers, micro-greens and a wide array of herbs, including seven types of mint and 22 varieties of basil, one of which tastes like bubblegum. A large greenhouse contains seedlings to transfer to the yard, and racks of plants fill the garage.

On a half-acre, she’s managed to grow 195 types of herbs, edible flowers and vegetables, whose seeds originated from across the globe. There’s even a beehive and hens on the property.

Rodriguez Boughton pours a layer of topsoil to prepare a new area for seedlings. Lynda Gonzalez/Reporting Texas

When Rodriguez Boughton, 33, moved to Austin in 2012 from her native Monterrey, Mexico, to attend the University of Texas at Austin’s McCombs School of Business, she didn’t envision adding the title of farmer to a resume that includes nearly six years in corporate banking. But in July 2014, she founded La Flaca and has since worked to grow the business into a profitable urban farm.

She moves around the farm with an ease and quiet confidence that belie her relative inexperience. She’s been farming only for a couple of years.

“Most people that live in cities don’t know a farmer, so people are always shocked when I tell them what I do for a living,” she said.

She doesn’t fit the traditional image of a Texas farmer. For starters, she’s nearly half the average age of farmers in the state. She’s also a woman and Latina.

Rodriguez Boughton is part of a growing number of women turning to agriculture. Today, 30 percent of U.S. farmers are women, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, up from 21 percent in 2007. Some, like her, are embracing it as a second career.

Her first inkling of a future career change came when she received a promotion at Banorte, one of Mexico’s largest private banks. “I realized I didn’t want my boss’ job or my boss’ boss’ job,” she said. Yet she pursued an MBA anyway, hoping that it would reinvigorate her interest in the financial world.

It was during the final weeks of the program when Rodriguez Boughton was in the midst of final-round interviews with Microsoft and other companies in Austin that she realized her definition of success had changed. “I was not looking to work hard and get money as I was in my 20s,” she said. “I wanted a purpose.”

In times of stress, Rodriguez Boughton found herself in the kitchen and she sought comfort in recreating her favorite dishes, toying with the idea of starting a business around cooking high-end Mexican cuisine. But she couldn’t find the chilhuacle peppers she needed to make Oaxacan mole tamales. She started growing the peppers, rarely found outside of Mexico, on her apartment balcony.

“One day in the shower it just struck me: what if I started growing rare produce to address local sourcing needs?” she said.

Given that she had no background in farming, she started going to agriculture conferences and took online and community college classes to learn everything she could about sustainable, small-scale farming. She also hired her first and only employee, Ben Carroll, who studied horticulture in college and moved from Connecticut to join La Flaca after meeting Rodriguez Boughton through a mutual friend.

Rodriguez Boughton pulls weeds on her farm, where she grows rare produce for local customers. Lynda Gonzalez/Reporting Texas

Her business background, paired with Texas’ year-round growing season, attracted Carroll, 25, to the position. “Farms fail because farmers have no business experience,” he said. “Farmers need to think like bankers.”

La Flaca sources produce, including chilhuacles, to seven Austin restaurants, including Olamaie, L’Oca D’Oro and Mattie’s at Green Pastures. It also sells produces to its neighbors in the cul-de-sac.

Unlike Rodriguez Boughton, most women aren’t the principal operators of Texas farms – they run 15 percent of farms in the state, one point above the national average, according to the 2012 USDA Agriculture Census, the agency’s most recent survey. Nationwide, women only own 7 percent of farmland.

Nine percent of farms in Texas have operators who identify as Hispanic or Latino, which is slightly higher than the national average of 3 percent.

“To become a farmer is a capital-intensive business and like any other business it takes money to make money,” said Robert Maggiani, a sustainable agriculture specialist at the National Center for Appropriate TechnologySouthwest Regional Office in San Antonio. “If you don’t have collateral and assets and you can’t borrow money, then you can’t really get into land unless you inherit it.”

Maggiani said that many Latinos also associate farming with poverty because that’s the way their families have experienced agriculture for the last half-century. “It’s not something that’s been promoted” in younger generations, he said.

Rodriguez Boughton decided to embrace small-scale agriculture because she wanted to remain in Austin, where the cost of land is on the rise. “Millennials aren’t moving to the country,” she said.

She relied on savings from her previous career to reduce the financial risk of jumping into an industry in which she had no experience. She purchased a small home in Austin’s Maple Run subdivision and rents out the rooms to cover the farm’s cost. A $5,000 grant from UnLtd USA and another in the same amount fromthe Austin Food & Wine Alliance have helped offset costs.

“Agriculture is a business that takes time to be self-sustainable,” she said, adding that she hopes to break even by the end of this year.

La Flaca translates to “the skinny woman,” and it’s also one of the names given to the Grim Reaper. Rodriguez Boughton chose a sugar skull, a calavera, for her logo to represent Mexican culture and reflect the farm’s young, urban feel.

“One of my favorite things of Mexican culture is how we make fun of our fears,” she said. “The biggest fear I’ve faced so far in my life was quitting a stable, profitable career to leap into the great unknown. So that logo and that name is a constant reminder to shake off my fears and keep moving forward.”

Her three goals for the end of the year are to grow more, get more people in the community growing and avoid bankruptcy. She’s working to recruit the farm’s neighbors to turn their own yards into gardens and to expand the city’s community of first-time, urban farmers. In five years’ time, she hopes to have transformed five acres of urban soil into productive farmland.

Edwin Marty, the food policy manager for the City of Austin, hopes that La Flaca’s story will change people’s perceptions of what good food means and get more people interested in growing.

“How we get out of the idea that good food is only for rich white people is a real challenge,” he said. “In all honesty, nothing could be farther from the truth, but that’s certainly a perception.”

Rodriguez Boughton said the fear that farming will ultimately not be financially sustainable still causes her many sleepless nights.

Rodriguez Boughton plucks an unwanted caterpillar from one of her plants. Lynda Gonzalez/Reporting Texas

“The way I try to approach this is to think ahead. I have clear goals on key metrics [in terms of] customers, sales [and] expenses that I constantly track,” she said. “When things are not working according to plan, I already have a plan B, C and D lined up. If this business ends up not succeeding for any reason, I want to have peace of mind that I gave it my all.”

Urban Farmer Transforms Community Into Thriving Local Food Haven

Sheryll Durrant. Photo credit: Keka Marzagao / Sustainable Flatbush

Urban Farmer Transforms Community Into Thriving Local Food Haven

By Melissa Denchak

Most people don't move to New York City and become farmers. Sheryll Durrant certainly wasn't planning to when she left Jamaica for Manhattan in 1989. She got her undergraduate degree in business from the City University of New York's Baruch College and spent the next 20 years in marketing. Then, when the 2008 financial crisis hit, Durrant decided to leave her job and try something new: volunteering at a community garden in her Brooklyn neighborhood.

It wasn't exactly uncharted terrain for this farmer's daughter. Growing up in Kingston, Durrant regularly helped her parents harvest homegrown fruits and vegetables. "But it didn't dawn on me that that was what I wanted to do," she said. Volunteering in the Brooklyn garden reminded her of her roots. "I would plant flowers or melons and that sense of putting your hand in the soil and becoming a part of that green space flooded back to me," she explained.

Kelly Street Garden.Craig Warga

Fast-forward to today. Durrant is a leader in New York's flourishing urban farming movement, which includes more than 600 community gardens under the city's GreenThumb program, plus hundreds more run by other groups across the five boroughs. A food justice advocate with a certificate from Farm School NYC, she's also a "master composter" and a community garden educator and she does outreach work for Farming Concrete, a data collection project that measures, among other things, how much urban farms and gardens produce.

Durrant's early work at the Sustainable Flatbush garden taught her the crucial first step in initiating any community project: Know your neighborhood's needs.

"We started by asking people in the community, 'What do you want to see?,'" she said. This market-research approach turned out to serve her goals—and her neighbors—well. When community members, many of whom were immigrants, expressed a desire to grow the plants and herbs of their native countries, Durrant and her fellow green thumbs collaborated with a local apothecary to establish a medicinal and culinary herb garden and to organize free workshops on how to use the herbs. These garden sessions—which covered women's and children's health, eldercare, and mental health issues like depression—at times drew more than 100 attendees.

After Brooklyn, Durrant relocated to the South Bronx, a neighborhood that's notoriously polluted, underserved and disproportionately malnourished, with more than one in five residents considered food insecure. The borough's gardens, said Durrant, help fill a void, serving as "one way we can bring fresh fruit and vegetables to a community that doesn't normally have access."

At the Kelly Street Garden, a 2,500-square-foot space on the grounds of an affordable housing complex, she serves as garden manager. And at the International Rescue Committee's New Roots Community Farm, a half-acre garden whose members include resettled refugees from countries like Myanmar and the Central African Republic, she works as a seasonal farm coordinator.

Keka Marzagao / Sustainable Flatbush

Last year, the Kelly Street Garden produced 1,200 pounds of food, available to anyone in the community who volunteered at the garden (and even those who didn't), free of cost. It was one of the few purveyors of healthy food in the neighborhood, where local stores often carry produce that's neither affordable nor fresh, due to lack of turnover. "If I have a limited amount of income, why would I waste my money or benefits on food that is going to perish in no time—that's already rotted when I get there?" Durrant said. For this reason, she explained, people often resort to purchasing processed foods that come in cans and bags. The longer shelf life stretches a tight budget. It also demonstrates why hunger often goes hand in hand with obesity—a problem particularly prevalent in the Bronx.

"I'm not going to say that community gardens and urban farms can feed New York City. Please, it's a city with over eight million people," Durrant said. "But they can provide some relief." What's more, she added, "They give you access to grow the food you want. That's where the food justice part comes in."

Margaret Brown, a Natural Resources Defense Council staff attorney who works on food justice issues, echoes Durrant's words. "One garden isn't going to fix hunger in your neighborhood, but community gardens are a way for people to take ownership over the food system in a very tangible way."

Of course, community gardens give rise to much more than fruits and vegetables. Durrant explained that the Kelly Street Garden serves as a space for cooking workshops and on-site art projects and hosts its own farmers' market. Meanwhile, the New Roots Community Farm has helped some of its neighborhood's newest arrivals find one another. "It's a means of engagement that a lot of our refugees are familiar with," she said. "It's welcoming, safe and a place where people can learn at their own pace and get involved in the country where they now live." Participants practice English ("Food is an incredible tool to teach English—a great entry point," said Durrant); plant hot peppers, mustard greens, melons and other edibles from their native homes; and exchange recipes.

Keka Marzagao / Sustainable Flatbush

Urban gardens also play a role in nutrition education. "Anecdotally, we've seen that when kids go to a community garden and get exposed to fresh fruits and veggies, they're much more likely to eat them when they're offered on the school lunch line, salad bar, or at home," Brown said.

Perhaps most important, the community garden movement and its focus on food inequities help advocates raise awareness of broader, interconnected environmental justice issues—like low wages and lack of affordable housing—that get to the heart of why people struggle to access healthy food to begin with. "Community gardens form a good space for people to come together around those issues," Brown said, "and hopefully find great organizing allies."

Durrant is clearly one of them. As part of her community outreach work, she arranges events to bring new audiences (whether corporate employees on volunteer workdays, or visitors on a Bronx Food & Farm Tour) directly through the garden gates. These visitors get a glimpse of the power of a small green lot in a sea of concrete—and if they're lucky, they leave with a taste of it, too.

Melissa Denchak is a freelance writer and editor, and has contributed to Fine Cooking, Adventure Travel, and Departures. She has a culinary diploma from New York City's Institute of Culinary Education and loves writing stories about food.

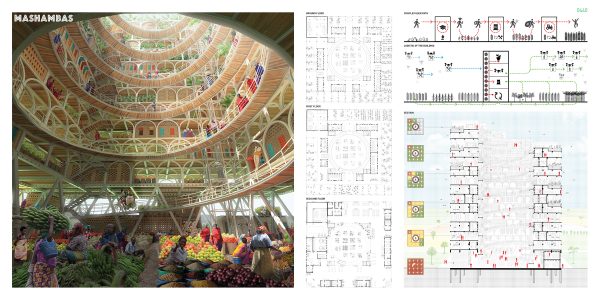

Mashambas Skyscraper

Mashambas Skyscraper

BY: ADMIN | APRIL - 10 - 2017

First Place

2017 Skyscraper Competition

Pawel Lipiński, Mateusz Frankowski

Poland

Mashamba– Swahili, East Africa

An area of cultivated ground; a plot of land, a small subsistence farm for growing crops and fruit-bearing trees, often including the dwelling of the farmer.

Over the last 30 years, worldwide absolute poverty has fallen sharply (from about 40% to under 20%). But in African countries, the percentage has barely fallen. Still today, over 40% of people living in sub-Saharan Africa live in absolute poverty. More than half of them have something in common: they’re small farmers.

Despite several attempts, the green revolution’s mix of fertilizers, irrigation, and high-yield seeds—which more than doubled global grain production between 1960 and 2000—never blossomed in Africa, because of poor infrastructure, limited markets, weak goverments, and fratricidal civil wars that wracked the postcolonial continent.

The main objective of the project is to bring this green revolution to the poorest people. Giving training, fertilizer, and seeds to the small farmers can give them an opportunity to produce as much produce per acre as huge modern farms. When farmers improve their harvests, they pull themselves out of poverty. They also start producing surplus food for their neighbors. When farmers prosper, they eradicate poverty and hunger in their communities.

Mashambas is a movable educational center, which emerges in the poorest areas of the continent. It provides education, training on agricultural techniques, cheap fertilizers, and modern tools; it also creates a local trading area, which maximizes profits from harvest sales. Agriculture around the building flourishes and the knowledge spreads towards the horizon. The structure is growing as long as the number of participants is rising. When the local community becomes self-sufficient it is transported to other places.

The structure is made with simple modular elements, it makes it easy to construct, deconstruct and transport. Modules placed one on the other create the high-rise, which is a form that takes the smallest as possible amount of space from local farmers.

Today hunger and poverty may be only African matter, but the world’s population will likely reach nine billion by 2050, scientists warn that this would result in global food shortage. Africa’s fertile farmland could not only feed its own growing population, it could also feed the whole world.

You Want Fresh? Dallas' Central Market is Growing Salad Behind The Store

You Want Fresh? Dallas' Central Market is Growing Salad Behind The Store

April 10, 2017

Written by: Maria Halkias

Fresh is a word that’s used loosely in the grocery business.

To the consumer, everything in the produce section is fresh. But most fruits and vegetables are picked five to 21 days earlier to make it to your neighborhood grocery store.

Central Market wants to redefine fresh when it comes to salad greens and herbs. It also wants to make available to local chefs and foodies specialty items not grown in Texas like watermelon radishes or wasabi arugula.

And it wants to be both the retailer and the farmer with its own store-grown produce.

The Dallas-based specialty food division of H-E-B has cooked up an idea to turn fresh on its head with leafy greens and butter lettuce still attached to the roots and technically still alive.

Beginning in May, the store at Lovers Lane and Greenville Avenue in Dallas will have a crop of about half a dozen varieties of salad greens ready for customers to purchase.

The greens will be harvested just a few dozen steps from the store’s produce shelves.

They’re being grown out back, behind the store in a vertical farm inside a retrofitted 53-foot long shipping container. Inside, four levels of crops are growing under magenta and other color lights. In this controlled environment, there’s no need for pesticides and no worries of a traditional farm or greenhouse that it’s been too cloudy outside.

Central Market has been working on the idea for about a year with two local partners -- Bedford-based Hort Americas and Dallas-based CEA Advisors LLC -- in the blossoming vertical and container farming business.

Plants are harvested inside a vertical farm in the back of the Central Market store in Dallas, Thursday, April 6, 2017. Central Market is trying out indoor growing, and the crops will be sold in the store beginning in May. (Jae S. Lee/The Dallas Morning News)

“We’re the first grocery store to own and operate our own container farm onsite,” said Chris Bostad, director of procurement, merchandising and marketing for Central Market.

There’s a Whole Foods Market store in Brooklyn, New York with a greenhouse built on the roof, but it’s operated by a supplier, urban farmer Gotham Greens.

The difference, Bostad said, is that “we can grow whatever our customers want versus someone who is trying to figure out how to cut corners and make a profit.”

Central Market’s new venture is starting out with the one Dallas store, said Marty Mika, Central Market’s business development manager for produce. “But we’ll see what the customer wants. We can do more.”

This has been Mika’s project. He’s itching to bring in seeds from France and other far off places, but for now, he said,“We’re starting simple.” The initial crop included red and green leafy lettuce, a butter lettuce, spring mix, regular basil, Thai basil and wasabi arugula.

The cost will be similar to other produce in the store, Bostad said.

Why go to so much trouble? Why bother with lighting and water systems and temperature controls in what’s become a high-tech farming industry?

“Taste,” Mika said. “Fresh tastes better.”

And the company wants to be more responsive to chefs who want to reproduce recipes but don’t have ingredients like basil leaves grown in Italy that are wide enough to use as wraps.

Tyler Baras, special project manager for Hort Americas, said with the control that comes with indoor farming there are a lot of ways to change the lighting, for example, and end up with different tastes and shades of red or green leafy lettuce.

Butter lettuce is harvested inside a vertical farm in the back of the Central Market store in Dallas, Thursday, April 6, 2017. Central Market is trying out indoor growing, and the crops will be sold in the store beginning in May. (Jae S. Lee/The Dallas Morning News)

Staff Photographer

In Japan, controlled environment container farms are reducing the potassium levels, which is believed to be better for diabetics, Baras said. “We can increase the vitamin content by controlling the light color.”

At Central Market, the produce will be sold as a live plant with roots still in what the industry calls “soilless media.”

Central Market’s crops are growing in a variety called stone wool, which is rocks that are melted and blown into fibers, said Chris Higgins, co-owner of Hort Americas. The company is teaching store staff how to tend to the vertical farm and supplying it with fertilizer and other equipment.

“Because the rocks have gone through a heating process, it’s an inert foundation for the roots. There’s nothing good or bad in there,” Higgins said.

Farmers spend a lot of time and money making sure their soil is ready, he said. “The agricultural community chases the sun and is at the mercy of Mother Nature. We figure out the perfect time in California for a crop and duplicate it.”

Growers Rebecca Jin (left) and Christopher Pineau tend to plants inside a vertical farm in the back of the Central Market grocery store in Dallas, Thursday, April 6, 2017. Central Market is trying out indoor growing, and the crops will be sold in the store beginning in May. (Jae S. Lee/The Dallas Morning News) Staff Photographer

He called it a highly secure food source and in many ways a level beyond organic since there are no pesticides and nutrients are water delivered.

Glenn Behrman, owner of CEA Advisors, supplied the container and has worked on the controlled environment for several years with researchers at Texas A&M.

“Technology has advanced so that a retailer can safely grow food. Three to five years ago, we couldn’t have built this thing,” Behrman said.

Mika and Bostad said they also likes the sustainability features of not having trucks transport the produce and very little water used in vertical farming. They believe the demand is there as tastes have changed and become more sophisticated over the years.

The government didn’t even keep leafy and romaine lettuce stats until 1985.

U.S. per capita use of iceberg, that hardy, easy to transport head of lettuce, peaked in 1989. Around the same time, Fresh Express says it created the first ready-to-eat packaged garden salad in a bag and leafy and romaine lettuce popularity grew.

In 2015, the U.S. per capita consumption of lettuce was 24.6 pounds, 13.5 pounds of leafy and romaine and 11 pounds of iceberg.

Consultant: Erie Urban Farming Plan Must Engage Community

Consultant: Erie Urban Farming Plan Must Engage Community

Charles Buki is the founder and principal of Alexandria, Virginia-based consulting firm CZB, which authored the city of Erie's comprehensive development plan. [KEVIN FLOWERS/ERIE TIMES-NEWS]

Posted Apr 9, 2017 at 2:00 AM

Charles Buki, whose firm authored the city’s comprehensive development plan, says urban agriculture could be a good fit for Erie with planning and citizen input.

Charles Buki believes the practice known nationwide as urban farming could be a good fit for Erie — if several important things happen.

The city’s zoning rules must clarify and outline what urban agriculture is and where it is allowed.

There should be clearly defined goals, such as creating green space, reducing blight, providing education and growing healthy foods for inner-city residents.

And city officials, community groups and citizens must collectively discuss the issue, including how best to develop urban farming management plans and what funding needs to be secured.

Public meeting May 3

The Erie Planning Commission's recommendations regarding zoning changes that would permit or clarify the rules for small crop farming in the city on residential properties and vacant lots, particularly in targeted areas, will be the subject of a May 3 public hearing in the Bagnoni Council Chambers at Erie City Hall, 626 State St.

The meeting will begin at 9:30 a.m.

The Planning Commission's recommendations include:

•Defining "urban garden, " "market garden" and "farm stand" in city zoning ordinances, and making them permitted uses within areas of the city now zoned medium density residential, high density residential and residential/limited business.

•Creating a specific zoning ordinance section that permits urban gardens on vacant lots in medium density residential, high density residential and residential/limited business areas, and making market gardens a "special exception" on vacant lots on those same districts.

•Requiring fences around urban gardens and urban markets.

•Including rules governing "accessory structures" associated with urban farming, and limiting them to 100 square feet in size. A storage shed would be an example of an accessory structure.

•Stipulations on how and where produce from urban farming can be sold; the proximity of urban agriculture sites to one-family and two-family houses; signs, traffic volumes, parking and compost use in those areas; and maintenance.

City Council must approve the zoning changes before they can take effect.

“Engage the community and help residents understand what’s possible,” said Buki, the founder and principal consultant at Alexandria, Virginia-based CZB, the consulting firm that authored Erie Refocused, the city’s first comprehensive development plan in decades.

Some local officials believe that creating an urban agriculture framework complements that plan, which addresses Erie’s future needs in terms of transportation, housing, land use, economic development and other areas, to combat decades of systematic decline.

Advocates say urban agriculture provides ways to effectively reuse properties that have been long vacant, and it can help reduce crime, promote neighborhood unity, provide education and job-training opportunities and increase access to healthy foods for city residents.

Buki this past said urban agriculture can benefit and help improve Erie, if the plan is forged carefully and includes significant community input.

“The interim goals can be interim banking of land until demand returns, interim beauty, interim stability,” Buki said, adding that “right-sizing the city” and “durable beautification” should also be key objectives.

“If you actually get food, too,” Buki said, “all the better.”

Erie City Council plans to launch that public engagement soon.

Council has scheduled a May 3 public hearing at Erie City Hall regarding a series of proposed amendments to city zoning ordinances that would permit or clarify the rules for small-crop farming on residential properties and vacant lots.

The zoning changes, right now, focus on a targeted area that includes the city’s east and west bayfront neighborhoods; Little Italy, on the city’s west side; and the areas near Pulaski Park, at East 10th Street and Hess Avenue, and the Land Lighthouse at the foot of Lighthouse Street.

The targeted areas are specified because they include large numbers of vacant property or dilapidated housing stock.

Matthew Puz, the city’s zoning officer, said the zoning changes are necessary because urban farming is only permitted in areas of the city zoned for light manufacturing, and that excludes many residential neighborhoods.

City Council must approve the zoning changes before they can take effect. The public meeting will give residents a chance to learn more about urban farming from city officials, and speak for or against the proposed changes.

“Different neighborhoods have already been doing this on certain lots,” said City Councilman David Brennan, who formally requested that the city examine the urban agriculture-related zoning changes. “Opening the door for this could help the city solve a lot of its current issues.”

Detroit, Boston, Portland, Cleveland, and Austin, Texas, are among cities that have revamped zoning rules or created new ones to encourage the production of local food, community gardens, farmers markets, food trucks, small urban growers and local businesses as a way of stabilizing neighborhoods.

A nonprofit in Detroit, the Michigan Urban Farming Initiative, created a 2-acre urban farm, 200-tree fruit orchard, children’s sensory garden, water harvesting cistern and more in Detroit’s lower North End that grows more than 300 produce varieties and provides fresh vegetables, free of charge, to about 2,000 city households, churches, food pantries and others in that area.

“Thoughtful initiatives like this have a large impact in community revitalization,” Katharine Czarnecki, the Michigan Economic Development Corporation’s vice president of community development, said of the nonprofit’s work in a recent news release.

Brennan said he believes urban agriculture will be an effective tool to “reuse a lot of these vacant properties, that’s in line with the comprehensive plan recommendations. And it can help stabilize a lot of these neighborhoods.”

Buki said that ideally the city should look to develop three large parcels of vacant property “downzoned into green space” for urban farming.

“Then you are right-sizing land at a volume that can stabilize land prices,” Buki said. “Then you are getting a critical mass suitable for commercial use. ... Then you have the basis for stabilizing blight.”

Brennan has said that City Council could vote on the zoning changes as soon as the panel’s May 17 meeting.

Kevin Flowers can be reached at 870-1693 or by email. Follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/ETNflowers.

NYC Luxury Condo Owners Want To Play Farmer

NYC Luxury Condo Owners Want To Play Farmer

April 08, 2017 - 03:30PM

It may sound like a bad SNL sketch about Brooklyn hipsters, but it’s no joke. A luxury condo building in Brooklyn comes with a working farm.

Eight floors above the ground at Barclays Center in downtown Brooklyn, workers at the condo building at 550 Vanderbilt Avenue are installing plots of soil on a south-facing terrace, according to the Wall Street Journal.

But not just anyone can farm. Owners will have to pay to play. And the building already has one high-profile farmer. Ian Rothman, a farmer and co-owner of the restaurant Olmsted, plans to grow hot peppers for the restaurant’s homemade aji dulce sauce at the building.

“We plan to develop a substantial amount of our space to peppers,” Rothman told the Journal.

Building residents can sign up each season for plots that are seven feet by 10 feet at the 1,600 square-foot “farm” — enough to harvest “a significant edible crop,” Ashley Cotton, executive vice president for external affairs for the developer Forest City Ratner Cos., told the Journal.

And while it may seem strange to garden high above the ground, there is one advantage: light.

“As a general rule,” Rothman said, “the more sun, the more vegetables you are going to get.” [WSJ] —Christopher Cameron

Good Food 100 Restaurants List to Highlight Sustainable Restaurants

Starting in June, consumers will be able to choose a place to eat based on a restaurant’s sustainability rating, indicated by a number of “links.” These links are the mark of a new restaurant survey, rating system, and list called The Good Food 100 Restaurants™.

Good Food 100 Restaurants List to Highlight Sustainable Restaurants

Starting in June, consumers will be able to choose a place to eat based on a restaurant’s sustainability rating, indicated by a number of “links.” These links are the mark of a new restaurant survey, rating system, and list called The Good Food 100 Restaurants™. The project aims to increase transparency surrounding sustainable business practices that benefit the environment, plants and animals, producers, purveyors, restaurants, and eaters.

The Good Food 100 Restaurants rating system measures chefs’ purchasing practices and determines the extent to which they are supporting local “good food” economies. The ratings are determined based on self-reported annual food purchasing data from a survey completed by participating chefs and restaurants. Any restaurant or food service operation in the United States, ranging from fast casual to fine dining, is eligible to take the survey.

A number of links—from two to five—will be awarded to each restaurant based on their performance as compared to similar survey participants. The inaugural list and ratings will be available to the public, along with an economic analysis report by the Business Research Division of Leeds School of Business at the University of Colorado Boulder, in June 2017 on The Good Food 100 Restaurants website.

Food Tank caught up with Sara Brito, the co-founder and president of The Good Food 100 Restaurants, to find out how this new system will affect the food world.

Food Tank (FT): Can you explain how the Good Food 100 Restaurants rating system works?

Sara Brito (SB): The Good Food 100 Restaurants is an annual list of restaurants spanning from fast casual and fine dining to food service that seeks to redefine how chefs, restaurants, and food service businesses are viewed and valued. The ratings focus on the quantitative measurement of chefs’ purchasing practices, which are based on the percentage of total food purchases spent to support local, state, regional, and national Good Food producers and purveyors compared to similar-type participating restaurants in the same region.

FT: Why did you see a need for the rating system now?

SB: Chefs are among the most trusted influencers in society today. According to the 2014 Edelman Trust Barometer, chefs are more trusted than doctors or lawyers. Until now, most of this recognition and influence has been based on the subjective standards and opaque criteria designed to reward chefs and restaurants (including food service) for how their food tastes.

I believe that good food is good for every link in the food chain. Now, more than ever, with sustainability and transparency being at the center of the industry and mainstream cultural conversation, eaters are demanding to know where their food comes from.

FT: How will this tool affect diners?

SB: The Good Food 100 will educate and inform eaters about the restaurants that are transparent with their purchasing and sustainable business practices.

FT: What will chefs gain from participating?

SB: By participating in the Good Food 100 Restaurants survey, chefs will be recognized and celebrated for being transparent with their purchasing practices. In addition, they will be contributing to a new, first-of-its-kind national economic assessment that aims to measure how restaurants are helping to build a better food system by supporting local, state, regional, and national ‘good food’ economies. Their participation will also help establish benchmarks for different types of restaurant and food service businesses across the country in order to help them understand and evolve their purchasing practices to help build a better food system.

How many chefs and restaurants will be included in the inaugural rating? Any notable names?

SB: The list of chefs and restaurants that have committed to taking the survey includes: Mike Anthony (Gramercy Tavern, Untitled, Union Square Hospitality Group), Rick Bayless (Frontera, Tortas by Frontera), Alex Seidel (Fruition, Mercantile & Provisions), Kelly Whitaker (Basta), Suzanne Goin (Lucques, A.O.C., Larder), Hugh Acheson (5 & 10), Jennifer Jasinski (Rioja), Jonathon Sawyer (Team Sawyer Restaurants), William Dissen (The Marketplace Restaurant), Stephen Stryjewski (Cochon, Butcher, Herbsaint, and Peche), Steven Satterfield (Miller Union), Paul Reilly (Beast + Bottle and Coperta), David LeFevre (Manhattan Beach Post, Fishing With Dynamite, and The Arthur J), Andrea Reusing (Lantern and The Durham), Renee Erickson (Walrus & Carpenter, The Whale Wins, Barnacle Bar, Bar Melusine, Bateau, General Porpoise), Bill Telepan (Oceana), and many more.

FT: Do you see this rating system changing the way the restaurant industry works? How?

SB: The Good Food 100 Restaurants ratings aim to redefine how chefs, restaurants, and food service businesses are viewed and valued. The rating system will also help establish benchmarks for different types of restaurant and food service businesses across the country in order to help them understand and evolve their purchasing practices to help build a better food system.

FT: What do you hope will happen with Good Food 100 Restaurants in the next 5 or 10 years?

SB: Like the Inc. 100 and Fortune 100, the Good Food 100 Restaurants is not limited to 100 restaurants. In the future, the full list could be 100 to infinity.

Urban Farm In Victoria Expands, Hopes To Grow 10,000 lbs Of Produce

Urban Farm In Victoria Expands, Hopes To Grow 10,000 lbs Of Produce

Topsoil’s new space includes 15,000 square feet to grow fresh produce and offers more sun exposure. Apr. 7, 2017 (CTV Vancouver Island)

CTV Vancouver Island

Published Friday, April 7, 2017 6:33PM PDT

Last Updated Friday, April 7, 2017 6:49PM PDT

A Victoria food producer is expanding its operation at Dockside Green after growing more than 7,000 pounds of produce last year.

Topsoil’s new space includes 15,000 square feet to grow fresh produce and offers more sun exposure.

The urban farm hopes to grow more than 10,000 pounds of produce in 2017.

The local food producer works with chefs in Victoria at the beginning of the season and customizes what it grows based on what the chefs need.

The founder of the business says the open site allows them to operate in full transparency.

“We’re being watched 24/7 and it gives us accountability and responsibility to produce the best, highest quality, safest, most nutritious produce possible for the city,” said Chris Hildreth.

Topsoil is working with four restaurants this year, including Caffe Fantastico, Fiamo Pizza & Wine Bar, Canoe Brewpub and Lure Restaurant & Bar.

The restaurants are so close the local food producer guarantees delivery in under 10 minutes.

The executive chef at Lure Restaurant & Bar says it’s important to support local farms.

“We think here on Vancouver Island there’s a huge market for it, there’s obviously a lot of production happening here as well,” said Dan Bain. “We don’t see a lot of reason to bring in vegetables from areas further away.

The Art of Urban Farming

The Art of Urban Farming

My Green Chapter brings gardening tools from around the world to help UAE residents join the growing network of urban farmers who want to live more sustainable lives

Published: 16:13 April 5, 2017

By Jyoti KalsiSpecial to Weekend Review

As our cities continue to expand, human beings are losing touch with nature. But the urban farming movement seeks to change this by encouraging people to grow vegetables and fruits in their yards, in empty lots in their neighbourhood and in public spaces such as schools, universities and hospitals. As this hobby becomes more popular, new and innovative products are being developed to help city dwellers grow herbs, salads and vegetables not only in gardens and yards but also on their balconies and inside their apartments.

My Green Chapter has brought this concept to the UAE with the launch of its online store, mygreenchapter.com. The store has sourced gardening and urban farming products from around the world to help UAE residents join the growing network of urban farmers, who want to live in harmony with nature, eat fresh, organic produce and live greener, more sustainable lives.

Besides gardening tools, equipment and materials for adults and children, the company offers innovative ‘smart garden’ technologies that make indoor farming as easy as clicking a button. The company also sells chicken coops, feed and accessories to enable urban farmers to raise chicken in their backyards.

The project is the brainchild of Frenchman Jean-Charles Hameau, who is an animal lover and gardening enthusiast. Hameau graduated in Agriculture Engineering and has a Master’s in Economics. He came to Dubai in 1999 as a commercial attaché in charge of agriculture and food at the French Consulate, and later co-founded the Saint Vincent Group which is the leader in the pet food and accessories industry in the GCC region.

Hameau spoke to the Weekend Review about urban farming and the new products that mygreenchapter.com is bringing to the UAE. Excerpts:

How did you get interested in urban farming?

A few years ago, I saw a documentary on TV about how the urban farming movement started in Detroit, USA, during the economic crisis in 2008, when people began using public spaces and abandoned industrial land to grow vegetables and fruits. Around the same time, I met a chicken coop supplier in Europe, and was surprised to hear that most of his company’s exports were to the GCC region. I did some research and realised that this is a part of the culture of this region and many families in the UAE are growing their own vegetables and keeping chickens in their backyard. Six months ago, I decided to keep some chickens in my garden, and seeing the smiles on the faces of my children when they pick up fresh eggs every morning is one of the factors that convinced me to start My Green Chapter.

What is your vision for the store?

Urban farming not only adds greenery to cities but also helps to reduce pollution and improve our health. Growing vegetables and fruits in our own gardens helps us to reconnect with the Earth and have a greater appreciation for where our food comes from. It reduces the food miles associated with long distance transportation while also ensuring that we eat the freshest produce and foods that are in season. We believe this is not just a passing trend but an unstoppable movement towards sustainable living, so our vision is to bring unique and innovative products to encourage the growth of urban farming in the UAE.

What kind of products are you focusing on?

For UAE residents who have gardens, we wanted to get the best quality gardening tools, seeds, potting soil, organic fertilisers, micro-irrigation kits, gloves and boots, and wooden chicken coops that are suited to the climate. It is particularly important to introduce children and young adults to green and sustainable living, hence we are offering a range of colourful gardening kits for children. Since the weather here makes it difficult to grow anything in summer and most people in the UAE live in apartments, we have sourced many innovative products that allow stress-free indoor gardening throughout the year. We also have a range of pots and planters, including self-watering pots and space saving designs for vertical gardening on indoor walls. We are working with experts in the field to source products that are suitable for the UAE and technologies that make gardening convenient. Our aim is to be a one stop shop for everybody’s gardening needs.

What are the new products you have introduced to this market?

We have many new products that take the effort and unpredictability out of gardening, making it easy for anyone to grow herbs, salads, vegetables and flowers all year round, even in indoor areas with limited space and sunlight. An example is the Click & Grow Smart Garden. All you have to do is to insert the plant capsules, fill the water tank, plug it in and the specially developed smart soil, and built-in sensors will make sure that the plants get optimal water, oxygen and nutrients. It comes with a Grow Light that immaculately calculates the spectrum of light required by the plants and the number of hours the light should be on and off. It makes the plants grow faster without any pesticides, hormones or other harmful chemicals and after you harvest the first crop, you can get new plant refills and re-use the Smart herb garden as many times as you wish.

Similarly, the Plantui Smart Garden is a hydroponic system whereby you can grow tasty greens without soil. The fully automated, patented growth process with special light spectrums, is packed into a beautifully designed ceramic device with overhead LED lights that provide optimal spectrums and intensity for photosynthesis. The watering and lighting are automatically adjusted during all growth phases, so all you do is to place the plant capsules containing the seeds in the device, switch it on and harvest the produce in about eight weeks. It comes in various sizes, to suit different kitchen spaces, allowing you grow three or more types of salads in the same unit.

Likewise, the Mini Garden is an innovative modular wall system for creating vertical gardens in a balcony of any size, or on a wall in a home or office. It comes with a patented irrigation system that automatically waters the plants. We will continue adding new products to our extensive range.

Can raising chicken in one’s yard also be so easy?

Farmers have been raising backyard fowl for over 3,000 years but only in the last five years has it become accessible for even the beginner farmer to raise their own livestock. We are the first suppliers of chicken coops in the UAE, and I can tell you that building a basic chicken coop for a small flock of birds is an easy do-it-yourself project that you can take on if you have a backyard at home. Keep in mind of course the rules regarding this in your neighbourhood and avoid keeping a rooster. It is worthwhile because you can raise them organically, free of hormones and antibiotics, and let them run around your yard rather than being cooped up in a cage. You can get around 300 eggs per hen per year, and the fowl are excellent mosquito repellants.

Is the UAE ready for the urban farming movement?

Absolutely. The country is becoming greener and has launched many sustainable living initiatives such as the urban farming competition recently organised by Dubai Municipality. I have read of urban farming programmes in local schools, and look forward to collaborating in such efforts because it is important for children to get away from their gadgets, step outdoors, connect with the Earth, learn where the food on their table comes from and experience the sheer joy of growing their own vegetables.

Jyoti Kalsi is a writer based in Dubai.

For more information go to www.mygreenchapter.com

Studio Visits: Go Inside Square Roots’ Futuristic Shipping Container Farm In Bed-Stuy

Studio Visits: Go Inside Square Roots’ Futuristic Shipping Container Farm In Bed-Stuy

POSTED ON WED, APRIL 5, 2017BY DANA SCHULZ

In our series 6sqft Studio Visits, we take you behind the scenes of the city’s up-and-coming and top designers, artists, and entrepreneurs to give you a peek into the minds, and spaces, of NYC’s creative force. In this installment we take a tour of the Bed-Stuy urban farm Square Roots. Want to see your studio featured here, or want to nominate a friend? Get in touch!

In a Bed-Stuy parking lot, across from the Marcy Houses (you’ll know this as Jay-Z’s childhood home) and behind the hulking Pfizer Building, is an urban farming accelerator that’s collectively producing the equivalent of a 20-acre farm. An assuming eye may see merely a collection of 10 shipping containers, but inside each of these is a hydroponic, climate-controlled farm growing GMO-free, spray-free, greens–“real food,” as Square Roots calls it. The incubator opened just this past November, a response by co-founders Kimbal Musk (Yes, Elon‘s brother) and Tobias Peggs against the industrial food system as a way to bring local food to urban settings. Each vertical farm is run by its own entrepreneur who runs his or her own sustainable business, selling directly to consumers. 6sqft recently visited Square Roots, went inside entrepreneur Paul Philpott‘s farm, and chatted with Tobias about the evolution of the company, its larger goals, and how food culture is changing.

Kimbal outside one of the farms

Tell us how you got interested in and involved with the urban agriculture movement? And how did you and Kimbal start Square Roots?

I came to the U.S. from my native UK in 2003 to run U.S. operations for a UK-based Speech Recognition software company (i.e. a tech startup). I have a PhD in AI and have always been in tech. Through tech, I first met Kimbal Musk–he’s on the board of companies like SpaceX and Tesla–who at the time was setting up a new social media analytics tech company called OneRiot, which I joined him on in 2006.

Since then, Kimbal’s been working on a mission to “bring real food to everyone.” Even while I was working with him in tech, he had a restaurant called The Kitchen in Boulder, Colorado that sourced food from local farmers and made farm-to-table accessible in terms of menu and price point. His journey in real food started in the late ’90s, when he sold his first tech company, Zip2, and moved to NYC and trained to become a chef, his real passion. When 9/11 happened he cooked for firefighters at Ground Zero. It was during that time – where people would come together around a freshly cooked meal – that he began to see the power of real food and its ability to strengthen communities, even in the most awful conditions imaginable.

In 2009, while we were both working at OneRiot, Kimbal had a skiing accident and broke his neck. Realizing life can be short, he decided to focus on this idea of bringing real food to everyone. So he left OneRiot to focus on The Kitchen, which is now a family of restaurants across Chicago, Boulder, Denver, Memphis, and more. That organization ploughs millions of dollars into local food economies across the country by sourcing food from local farmers and giving its customers access to healthy, nutritious food. They also run a nonprofit, The Kitchen Community, that’s built hundreds of learning gardens in schools across the country, serving almost 200,000 school children a day.

After Kimbal’s accident, I became CEO of OneRiot, which was acquired by Walmart in 2011, where I ended up running mobile commerce for international markets. I learned a lot about the industrial food system there by working with huge data sets of the groceries people were buying across the globe and researching where those foods were being grown. I began to visualize food being shipped across the world, thousands of miles, before consumers bought it. It’s well known that the average apple you buy in a supermarket has been traveling for nine months and is coated in wax. You think you’re making a healthy choice, but the nutrients have all broken down and you’re basically eating a ball of sugar. That is industrial food. I left Walmart a year later and became CEO of an NYC photo editing software startup called Aviary, but I couldn’t get this map of the industrial food system out of my head. When Aviary was acquired by Adobe in 2014, I re-joined Kimbal at the Kitchen and we started developing the idea for Square Roots.

What we saw was that millions of people, especially those in our biggest cities, were at the mercy of industrial food. This is high calorie, low nutrient food, shipped in from thousands of miles away. It leaves people disconnected from their food and the people who grow it. And the results are awful – from childhood obesity to adult diabetes, to a total loss of community around food. (Not to mentioned environmental factors like chemical fertilizers and greenhouse gases.)

We also saw that these people were losing trust in the industrial food system and wanted what we call “real food.” Essentially, this is local food where you know your farmer. (This isn’t just a Brooklyn hipster foodie thing. Organic food has come from nowhere to be a $40 billion industry in the last decade. “Local” is the food industry’s fastest growing sector.)

Meanwhile, the world’s population is growing and urbanizing quickly. By 2050 there will be nine billion people on the planet, and 70 percent will live in cities. So if we have more people living in the city, demanding local food, the only conclusion you can draw is that we’ve got to figure out how to grow real food in the city, at scale, as quickly as possible. In many ways NYC is a template for what that future world will look like. So our thinking was: if we can figure out a solution in NYC, then it will be a solution for the rest of the world as it increasingly begins to look like NYC. The industrial food system is not going to solve this problem. Instead, this presents an extraordinary opportunity for a new generation of entrepreneurs – those who understand urban agriculture, community, and the power of real, local food. Kimbal and I believe that this opportunity is bigger than the internet was when we started our careers 20 years ago.

So we set up Square Roots as a platform to empower the next generation to become entrepreneurial leaders in this real food revolution. At Square Roots, we build campuses of urban farms located in the middle of our biggest cities. The first campus is in Brooklyn and has 10 modular, indoor, controlled climate farms that can grow spray-free, GMO-free, nutritious, tasty greens all year round. On those farms, we coach young passionate people to grow real food, to sell real food, and to become real food entrepreneurs. Square Roots’ entrepreneurs are surrounded and supported by our team and about 120 mentors with expertise in farming, marketing, finance, and selling–basically everything you need to become a sustainable, thriving business.

Why did you choose to set up at Bed-Stuy’s Pfizer Building?

We believe in “strengthening community through food,” and hopefully by joining forces with all the awesome local food companies already in Pfizer, we’re doing our part towards that. Next, in the lead up the first World War, that factory was the U.S.’s largest manufacturer of ammonia, which at the time was used for explosives. Post war, the U.S. had excessive amounts of ammonia, and it started being used as fertilizer. So in many ways, that building is the birth place of industrial food. I like the act of poetic justice that we now have a local farm on the parking lot.

Paul Philpott’s company is called Gateway Greens. His membership-based business model is that his members pay a premium to subsidize food for low-income New Yorkers.

He grows oregano, parsley, sage, thyme, and cilantro, as well as swiss chard, collard greens, and kale.

You received more than 500 entrepreneur applications; how did you narrow it down to just 10?

Lots of late nights watching video applications! We were looking for people with shared values and mission – a belief in the power of real, local food. And we needed to see a passion for entrepreneurship. Being an entrepreneur in Square Roots is hard and we needed to make sure that first 10 were coming in with eyes wide open. They are really kicking ass now!

Each farm can produce 50,000 mini-heads of lettuce per year.

The greens are grown hydroponically, meaning the nutrients are mixed with the water that feeds the roots, since the system is soil-free and uses LED lights. Each farm uses about 10 gallons of water a day–less than a typical shower.

For someone who’s not familiar with this type of technology, can you give us a basic rundown of how it works and compares with traditional farming?

The first thing we’ve got to do is build farms in the middle of the city. In Bushwick, these are modular, indoor, controlled climate, farms. You can put them in the neighborhood right next to the people who are going to eat the food. To set this up, we literally rent spaces in a parking lot and drop the farms in there. It’s scrappy, but they enable year-round growing and support the annual yield equivalent of two acres of outdoor farmland inside a climate-controlled container with a footprint of barely 320 square feet. These systems also use 80 percent less water than outdoor farms. That’s the potential for a lot of real food grown in a very small space using very few resources. Each of our ten farms is capable of growing about 50 pounds of produce per week. Most of that today goes to customers of the Farm to Local program, where a local farmer will deliver freshly harvested greens direct to your office (people love having a farmer show up at their desk with freshly harvest greens right before lunch!) Some of the farmers sell to local restaurants also.

Why do you think consumers in general respond so well to this type of local farming?

This generation of consumers want food you can trust, and when you know your farmer, you trust the food. There are so many layers between the farmer and the consumer in industrial food–agents, manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, the list goes on. And every one of them takes their cut, leaving the farmer with paper thin margins and the consumer with no connection to the food or the people who grow it. That’s 20th century food, where it takes weeks to get to you and the food has to be grown to travel. Square Roots farmers can harvest and deliver within hours – meaning food is grown for taste and nutrition.

Moving forward, how do you hope urban farming will coincide with more traditional agriculture?

The consumer wants local food where they know the farmer and the food tastes great. Whether that’s grown on a no-till organic soil farm or in a container on a parking lot, if it’s local food it’s food you can trust – and we’re all on the same side. The common enemy here is industrial food.

Where do you hope Square Roots will be in a year from now? What about 10 years?

We grow a ton of food in the middle of the city and sell locally. So we see revenue from direct-to-consumer food sales and we’re building a very valuable local food brand. But as we replicate campuses and our program to new cities, we’re building that local food brand at a national and then ultimately global scale. At the same time, our model unleashes an army of new real food entrepreneurs who will graduate from Square Roots and start their own amazing businesses, who we will invest in.

I’ve been quoted on this before, but I’d like to think I can open Fortune Magazine in 2050 and see a list of Top 100 Food Companies in the world, which includes Square Roots and 99 others that have been started by graduates of Square Roots, who all share our same values. That would mean we’re truly bring real food to everyone.

+++

All photos taken by James and Karla Murray exclusively for 6sqft. Photos are not to be reproduced without written permission from 6sqft.

New School Students Research and Rethink Rooftop Urban Gardens

In 2014, Vice Media, having just moved into its their new offices in Williamsburg, worked with Brooklyn Grange to turn their expansive rooftop into a vegetable garden and recreational space for their employees to enjoy

New School Students Research and Rethink Rooftop Urban Gardens

Apr 5, 2017

In 2014, Vice Media, having just moved into its their new offices in Williamsburg, worked with Brooklyn Grange to turn their expansive rooftop into a vegetable garden and recreational space for their employees to enjoy.

From the natural meadows to the delicious vegetables, the perks of Vice’s rooftop urban farm seem fairly obviously. But what benefits might this green infrastructure have to the broader environment?

Students at The New School are trying to find that out.

Over the last three semesters, students in the Green Roof Ecology undergraduate course have conducted research at rooftop farms throughout New York City to measure, and think about ways to enhance, the ecological benefits — increased biodiversity, mitigation of urban heat island effects, and absorption of stormwater — of green roofs such as Vice’s.

The class — which includes students from Parsons School of Design and Eugene Lang College and is supported by the Lang Civic Liberal Arts program — is a reflection of The New School’s dedication to cross-disciplinary learning, design for social good, and real-world experiences.

“In the Green Roof Ecology class, we’ve managed to pull together students who are interested in ecology — very science-oriented students — together with students studying graphic design, information design, communication design, and architectural design all together in one space to really consider how you re-think a green roof,” said Associate Professor of Urban Ecology Timon McPhearson, who teaches the class and co-founded it with faculty member Kristin Reynolds.

To learn more, visit Vice Green Roof x New School on Instagram.

Redefining Urban Farming

Redefining Urban Farming

by Ronni Wilde, for The Bulletin Special Projects

Published Apr 4, 2017 at 11:56AM / Updated Apr 4, 2017 at 11:57AM

As Central Oregon grows in population, more and more of its residents are living in homes and apartments with tiny yards, and in some cases no yard at all. While that can be a challenge to those interested in growing food, all is not lost. Container gardening can be a fun and simple way to put a green thumb to work and grow a few veggies on a patio, deck or even inside on window sills.

Benjamin Curtis, urban farmer and founder of Full Rotation Farms Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program, began his operation without a budget, and suggests that anyone can do the same.

“You can go to landscape companies and get free black pots, or offer to do some work for them in exchange for pots,” he said. “I was so broke, I started with yogurt containers. You can also make planter boxes out of wooden pallets.”

If a garden will be in window sills, Curtis recommends putting the containers in south-facing windows for maximum sunlight. If it will be created in a small space outside, a “greenhouse” can be made out of large sheets of plastic, he said.

For watering outside, rows of containers can be lined up on a patio or dirt patch, or raised beds can be created. Lining up the containers in rows simplifies the watering process, he said, which can be done with a watering can or hose. A watering device can even be made out of a milk jug by poking holes in the top, he said. If the garden is inside, Curtis recommends using drip containers that won’t leak onto the floor, or taking care to use something to catch the water that flows out of the pots after watering.

When you are ready to plant, Curtis said seeds can be purchased online, or at home improvement or farm and garden stores such as Wilco.

“Seed packets tell you what to do,” he said. “Just follow the directions. Growing only one item, like tomatoes, may be a good way to start.” If you don’t have a sunny location, he suggests looking for plants that like shade, such as spinach. To create a larger variety of vegetables or a continued harvest, he recommends staggering crops by planting a new row of seeds every two to three weeks.

With a little work and a few months’ time, having homegrown vegetables without a yard can be a reality.

“I grow food in my indoor nursery year-round,” said Curtis. “Right now, I have leeks, tomatoes, broccoli, pea shoots, kale, spinach and lettuce. I am eating a salad a day out of my winter crop.”

Full Rotation Farms, a successful urban farming operation created a year ago by Bend massage therapist Benjamin Curtis, is testament that with determination and grit, anything is possible. In early 2016, Curtis had a box of seeds, $7.13 and a vision. But that February, he launched his Full Rotation Farms Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program, and has since grown 1,500 pounds of vegetables on 2,100 square feet of land, supplying as much as 50 pounds of food to an average of 50 people a week during last year’s growing season.

For eight months last year, Curtis worked six days a week, he said, and during peak season, he worked 12-hour days for six straight weeks.

“Urban farming is complicated due to having multiple plots,” said Curtis. “It can be difficult and filled with logistical challenges. However, even though I wanted to quit many times, I did not. The pros outweigh the cons.

“Farming for my outstanding CSA has given me deep fulfillment, more courage and less depression, and there is a smaller carbon footprint (than with traditional farming),” he added.

With a CSA, money supplied by the members builds the farm, so they each own a share.

Despite the challenges in operating a CSA, Curtis remains passionate about growing for himself and others because he believes there is a global crisis due to the shortage of fresh food grown without chemicals.

“We have a serious food problem, and people don’t even know,” said Curtis, who is a U.S. Navy veteran. “If it were a perfect world with healthy food, I would not be so passionate. I want to help solve this problem, be a man of action, and put my money where my mouth is.”

The mission statement for Curtis’ CSA reads, “Full Rotation Farms is determined and committed to doing whatever it takes within the framework of integrity to change our food system by building and educating a healthier food culture, empowering people through direct contact and practicing small-scale organic methods so we can consistently serve your family with the freshest cut produce possible.”

Curtis began taking an interest in farming while growing up in small towns around Oregon, he said, and while attending school and living in Utah, where he worked alongside his stepfather in a fruit stand. He said he learned entrepreneurial skills at that time, and began growing food for himself.

“I’ve been feeding myself for my entire adult life, and I knew I wanted to be a farmer,” he said. “I’ve always wanted to live off grid, fully in nature. I’m really into self-reliance, because it teaches self-esteem. I lacked that in the past.”

Over the years, he practiced small-scale farming techniques, planting garden boxes on rooftops in Portland in 2002, working and managing a half-acre vegetable plot in Hawaii from 2008 to 2010, and growing food on a half-acre mini-farm in Alsea, Oregon in 2011.

In recent years, Curtis said he has been inspired by Bend urban farmer Jim Fields, who has a 10-acre plot right in the middle of town off Pettigrew Road. Fields Farm also offers a CSA program, and has been supplying produce to Central Oregonians since 1989.

Though there are other urban farmers in the region, what makes Curtis’ approach unique is that he does not own the land he uses. He farms in other people’s yards. With the blessing of participating homeowners, Curtis cultivates lawns, gardens and unused land and turns those spaces into productive food-producing plots. In 2016, he utilized three yards on the Westside of Bend, and was feeding 13 Full Rotation Farms member families by April 15. By June, he was in peak season, and continued to supply vegetables through December.

“On those 1-degree days, the veggies survived because I used a special cloth and greenhouse materials,” said Curtis. When the snowpack became too thick, he stopped harvesting. “But in spring, some of those vegetables will still be OK,” he said.

“This has been a big ordeal,” said Jason Friedman, owner of Center for Life Chiropractic and Wellness in Bend and a Full Rotation Farms member. “Benjamin and I have been friends for a long time. He spoke to me about urban farming awhile ago, and he really decided to go for it. I’m very proud of him, because besides the physical burden, he also had to learn about major farmer juggling, like rotating crops and dealing with the weather.

“It’s like he got a master’s degree in organic farming in one season,” Friedman added.

Among the vegetables Curtis provided through his CSA last season are kale, chard, an assortment of beets, salad greens, carrots, Pac Choi (Asian greens) and tomatoes. He also hunted and cultivated mushrooms to add to the food baskets. To participate in the CSA, members pay an upfront fee of $150, which entitles them to a weekly pick up for four to six weeks depending upon the quantity of vegetables supplied. Curtis customizes baskets for members based on family size and preferences.

“I’ve been a member of a CSA before, and there isn’t usually this much variety,” said Friedman. “You get to choose what you want each week, so you’re not stuck with food you don’t want. It’s hard to grow things here, which makes this even more impressive. It’s pretty amazing to become so adept at growing so much food for so many people in this climate.”

For the coming season and into the future, Curtis has set lofty goals, and is working hard to make them happen. As of early 2017, he has 15 members in his CSA, and hopes to grow that number to 30 by this year’s peak season. He plans to start distributing food as early as the end of March, and has been growing an assortment of food over the winter in his indoor nursery to accomplish that goal. He has also recently acquired a three-year lease on a one-acre plot on the Westside, and hopes to secure one more yard for this season.

To move forward on the one-acre plot, Curtis estimates that the cost for fencing, irrigation, equipment and insurance will be in excess of $10,000. To procure the needed money, Curtis has established an online crowd funding account on Go Fund Me and a loan campaign through Kiva, an international nonprofit group money lending program.

“I will continue to farm multiple yards if I get them, but the focus is the acre,” he said. “I am looking for investors. I want to make some money and reinvest it, pay off the loans within a year, and then get a bigger loan to grow the business.”

To date, Curtis supports himself with his massage therapy practice, but hopes to be able to make a living off Full Rotation Farms eventually.

“I started this with no money — I don’t suggest that,” he said with a laugh. “It’s best to have at least $6,000 to start with, and don’t quit your job. Doing therapeutic massage has allowed me to invest in Full Rotation Farms and survive as an urban farmer in my first year.”

In addition to retaining a CSA membership, Friedman has invested in Full Rotation Farms to help Curtis grow the operation.

“I wanted to support a friend who is very forward-thinking. I’m honored to be a part of that,” said Friedman. “Growing food instead of grass is a very green thing to do. Curtis went out on a limb and literally removed someone’s yard to do this. It takes a forward-thinking homeowner to do this.”

While Curtis’ desire is to grow Full Rotation Farms as his business, the other side of his passion lies in teaching others how to grow food.

“The barriers to entry in farming are astronomical,” he said. “That’s why I want to teach young people how to farm a yard with real-time training. At my first location, it was not unusual to have young people show up wanting to help. But due to time constraints and land restrictions, I was forced to turn them away, which broke my heart.”

To offer mentoring and training to those who want to learn urban farming techniques, Curtis hopes to establish “Farm Fit Day” events on Saturdays during the 2017 growing season. During these programs, volunteer participants will work the land alongside Curtis while he trains them. They will gain skills, and may walk away with some fresh veggies too, he said.

Friedman said he has found purchasing vegetables from Curtis to be beneficial in many ways.

“It’s less expensive than going to the store and buying organic produce because there are no middlemen involved between the farmer and the store, and the vegetables are fresher,” he said.

“His vegetables are much more bio-available for our bodies because they are grown right here and are acclimated to our climate like our bodies. For those of us who understand that food is medicine, you understand that there is good medicine and bad medicine. This food is more suitable for us than organic food grown far away.”

Because of their membership in Full Rotation Farms, Friedman said his family tends to eat more vegetables.

“My 8-year-old son loves rainbow chard,” said Friedman. “Getting your kid to eat greens is really great. I didn’t even know he liked chard until we became members.”

The ultimate benefit, Friedman said, is how good the vegetables taste.