Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Coffee Grounds Used To Feed A Hungry City

Coffee Grounds Used To Feed A Hungry City

In an Australian first, Port Melbourne based coffee company Red Star Roasters has partnered with urban food production company Biofilta, to transform a disused Melbourne carpark into a pop-up espresso bar and thriving vertical urban food garden. The garden is converting the by-product from Melbourne's unique coffee culture coffee grounds into thousands of dollars of fresh edible produce for charity kitchens.

The Red Star Urban Garden Espresso Bar, located at The Holy Trinity Anglican Church at 160 Bay Street, Port Melbourne, features an innovative vertical food garden that uses soil made from composted green waste and coffee grounds, to grow a full range of vegetables and herbs including basil, beans, eggplant, capsicum, kale, lettuce, oregano, rhubarb, spinach, strawberries, thyme, tomatoes, zucchinis, beetroot, broccoli, bok choy and many others. Coffee grounds are collected from the espresso bar, mixed with garden clippings, cardboard packaging, soil and worms to create a rich compost onsite. The compost is then returned to the vertical gardens, to grow food. The produce is then harvested and donated to the South Port Uniting Care?s Food Pantry and Relief Service in South Melbourne. Diane Embry, the Agency's Chief Executive Officer, says, the donations enables us to provide fresh produce to people in our community who are experiencing disadvantage, social isolation and homelessness.

The garden itself is unique - with vertically stacked growing beds that are self-watering and an innovative aeration loop to keep the plants and soil oxygenated and healthy. The garden is ultra water efficient and spatially compact, and by going vertical the garden produces a large amount of food on a very small footprint, effectively doubling food yield per square metre. The vertical garden is integrated into the espresso bar coffee grounds used to feed a hungry city and café patrons are surrounded with edible gardens, aromatic herbs and flowers as they read the paper and have a coffee. In the past 12 months, the garden has produced well over 100 kilograms of vegetables and herbs from 10 square metres of garden area. However, because of the vertical design, the garden is only using 5 square metres of space. This means the garden is producing 10 kg of food per 1 sqaure metre of garden every year and at an average cost of between $5 to $10 per kg for vegetables at the Supermarket, the garden is producing $50 to $100 of food per metre square each year.

It is great having a garden that saves you money while feeding you and the family at the same time. Australia imports over 40,000 tonnes of coffee beans per annum, resulting in a huge waste stream of used coffee grounds that go to landfill. Red Star and Biofilta have worked out a way to divert this useful by-product into food to feed a hungry city and are now looking to replicate the model with cafes and restaurants who are interested in saving on food bills and growing fresh produce onsite. 100% of coffee grounds from the Red Star Urban Garden Espresso Bar are either used in the garden, or given away for free to customers to use in their gardens at home.

Creating A Zero-Coffee-Waste Café!

CEO of Biofilta, Marc Noyce said - Thousands of tonnes of coffee grounds are produced each week in Australia's cafés and restaurants, and most ends up in landfill. Red Star and Biofilta have shown how this wonderful material can be composted to soil and help feed hungry cities at the same time. Both companies are looking for more opportunities to repeat the formula with any café or restaurant who are interested in ethically sourced coffee, and have a spare space, wall, rooftop or balcony to turn.

For more information call:

Diane Falzon, Falzon PR- 0430596699

Marc Noyce, CEO, Biofilta - 0417 133 243

Chris McKiernan, Director, Red Star Coffee - 0418 136 301

Kimbal Musk Says Food Is The New Internet

Kimbal Musk Says Food Is The New Internet

Former tech entrepreneur Kimbal Musk’s ambitions for innovation in sustainable farming are as grand as his brother Elon’s for space travel and electric cars

URBAN COWBOY | Kimbal Musk at Koberstein Ranch in Colorado. “He’s got good judgment overall and has been put through the ringer a few times,” says his brother, Elon. PHOTO: MORGAN RACHEL LEVY FOR WSJ. MAGAZINE

By Jay Cheshes

May 25, 2017 10:52 a.m. ET

ON A BRISK WINTER morning, Kimbal Musk is an incongruous sight in his signature cowboy hat and monogrammed silver K belt buckle—his folksy uniform of the past few years—as he addresses a crowd outside a cluster of shipping containers in a Brooklyn parking lot. Inside each container, pink grow lights and fire hydrant irrigation feed vertical stacks of edible crops—arugula, shiso, basil and chard, among others—the equivalent of two acres of cultivated land inside a climate-controlled 320-square-foot shell. “This is basically a business in a box,” Kimbal says, presenting his latest venture to its investors, friends and curious neighbors.

Square Roots, his new incubator for urban farming, aims to empower a generation of indoor agriculturalists, offering 10 young entrepreneurs this year (chosen from 500 applicants) the tools to build a business selling the food they grow. It will take on and mentor a new group annually, with more container campuses following across the country. “Within a few years, we will have an army of Square Roots entrepreneurs in the food ecosystem,” he says of the enterprise, launched last November with co-founder and CEO Tobias Peggs—a British expat with a Ph.D. in artificial intelligence—across from the Marcy Houses, in Bedford-Stuyvesant (where Jay Z, famously, sold crack cocaine in the 1980s).

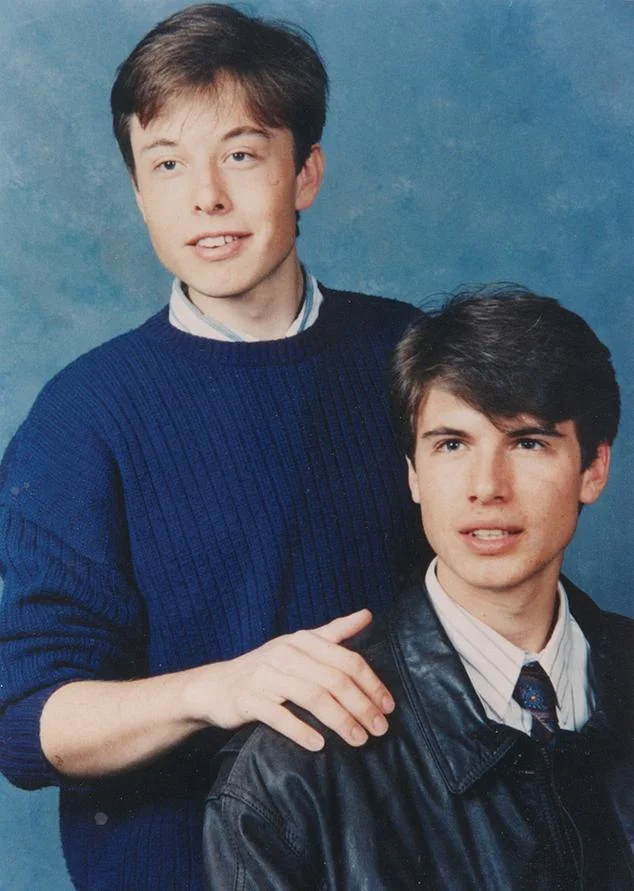

Clockwise from far left: Elon (left) and Kimbal, at 17 and 16. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIMBAL MUSK

Entrepreneurial drive runs in the family for Kimbal, 44, a close confidante of his brother, Elon, and a board member (and major shareholder) at Tesla and SpaceX. “If something happens to me, he can represent my interests,” says Elon of his kid brother (one year younger) and worst-case-scenario proxy. “He knows me better than pretty much anyone else. He’s got good judgment overall and has been put through the ringer a few times.”

Kimbal, a veteran of the tech world, has in recent years shifted his focus to food—or the “new internet,” as he called it in a 2015 TEDx Talk. With the missionary zeal his brother brings to electric sports cars and private space travel, Kimbal has launched a series of companies designed to make a lasting impact on food culture, through restaurants, school gardens and urban farms.

‘‘I want to reach a lot of people. We’ve put too much emphasis on preciousness with food.’’

—Kimbal Musk

Since 2010, a nonprofit venture supported by the Musk Foundation has built hundreds of Learning Gardens in American schools, installing self-watering polyethylene planters where kids learn to grow what they eat. Meanwhile, his Kitchen family of restaurants—promising local, sustainable, affordable food—is rapidly expanding across the American heartland, with five locations opening this year, including new outposts in Memphis and Indianapolis. Kimbal hopes to have 50 “urban-casual” Next Door restaurants, 1,000 Learning Gardens and a battalion of container farms by 2020. “I want to be able to reach a lot of people,” he says. “I think we’ve put too much emphasis on preciousness with food—and the result is a real split between the haves and have nots.”

The Musk brothers grew up in South Africa during the last gasp of the apartheid era. Kimbal, the more gregarious sibling, got his start selling chocolate Easter eggs at a steep markup door-to-door in their Pretoria suburb. “When people would balk at the price, I’d say, ‘You’re supporting a young capitalist,’ ” he recalls. While Elon spent hours programming on his Commodore VIC-20, Kimbal tinkered in the kitchen. “If the maid cooked, people would pick at the food and watch TV,” he says. “If I cooked, my dad would make us all sit down and eat ‘Kimbal’s meal.’ ”

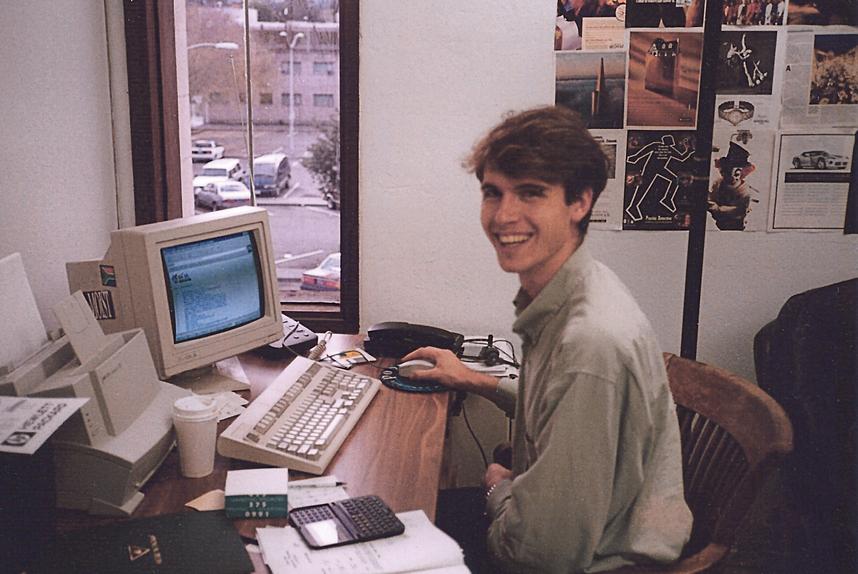

Kimbal in the kitchen, 2002. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIMBAL MUSK

After high school, the brothers moved to Canada, both enrolling, for a time, in Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario (Kimbal studied business, Elon physics). In 1995, they founded a company together in Palo Alto, California, the online business directory Zip2. “I had come over as an illegal immigrant,” Kimbal says of the move. “We slept in the office, showered at the YMCA.”

The brothers were close but also intensely competitive. Sometimes work disputes would get physical. “In a start-up, you’re just trying to survive,” says Elon. “Tensions are high.” Once they could afford it, Kimbal cooked for the whole Zip2 team in the apartment complex they shared. In 1999, the Musks sold their business to Compaq for $300 million. Though they remain investors and advisers in each other’s companies, their official partnership ended there.

HOME FRONT | Kimbal’s mother, Maye (right), with her parents at the family farm near Pretoria, South Africa, 1978. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIMBAL MUSK

After Elon launched the payment site that would later become PayPal , Kimbal, on a lark, enrolled in cooking school. He finished his studies at the French Culinary Institute in New York in late summer 2001 with no intention of pursuing a career in food. A few weeks later, after two planes flew into the Twin Towers, he spent the next six weeks as a volunteer cook, feeding firefighters out of the kitchen at Bouley. At the end of it he wanted nothing more than to open his own restaurant. “After that visceral experience, I just had to do it,” he says.

Searching for a dramatic change in scenery, post-9/11, Kimbal and his new wife at the time, lighting artist Jen Lewin, set out on a cross-country road trip looking for a place to put down roots and raise a family. They settled on Boulder, Colorado, “a walkable town, a great restaurant town,” says Kimbal at the 140-year-old Victorian home they bought there in 2002 (they have two sons and have since divorced).

The house he now shares with food-policy activist Christiana Wyly—with a cherry-red Tesla parked out back—is a few blocks from the original Kitchen, an American bistro he launched in 2004 with chef-partner Hugo Matheson, a veteran of London’s River Cafe. The Kitchen sourced ingredients from local farmers, composted food waste, ran on wind power and used recycled materials in its décor. For its first two years, the two partners worked full-time as co-chefs, taking turns composing the menu, which changed every day. Eventually, the daily grind became too much for Kimbal. “I got a little bored with the business,” he says.

Kimbal in his Zip2 office, 1996. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KIMBAL MUSK

By 2006, he was back working in tech, as CEO of a social-media-analytics start-up. The Kitchen might have remained a sideline if not for a series of unlikely events. On February 10, 2010, at a TED conference in California, he listened to Jamie Oliver admonish America for its childhood obesity problem. Four days later, while barreling down a slope in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Kimbal flipped his inner tube and broke his neck. In the hospital, wondering if he’d ever walk again, he began to reconsider his life, with Oliver’s comments rattling around in his head. “The message I heard was: The people who have no excuse should be doing something about this—and I was one of those people,” says Kimbal. “I told myself, If I get through this I’m going to focus on food and doing things at scale.” Apart from losing some feeling in his fingers, he made a full recovery.

Since then Kimbal has become a cheerful crusader for “real food,” as he calls it, sharing his message on the lecture circuit. “He’s a compelling speaker,” says food writer and activist Michael Pollan. “Particularly in his passion for kids, his recognition that if we’re going to change our approach to eating in this country, it’s about showing kids where food comes from, how to grow it, how to prepare it.”

“In 2004, there were very few local farmers that would work with us,” says Kimbal. “We opened the Kitchen before farm-to-table was a term. We showed that you could be busy and profitable while creating a new supply chain. Now there’s a huge backlash against processed food, industrial food. Real food is simply food you trust to nourish your body, nourish the farmer and nourish the planet.”

Bowery Reinvents Farming for Urban Landscapes

Bowery Reinvents Farming for Urban Landscapes

May 26, 2017 by Annie Pilon In Green Business

Agriculture is one of the oldest industries out there. But businesses are still finding new ways to update this industry in order to get fresh produce to the people who need it most.

Bowery Indoor Farming

Bowery is one such business. The farming startup made its goal to get fresh produce to consumers in big cities in a sustainable way. To achieve that goal, the company uses hardware and proprietary software to set up vertically stacked gardens that operate indoors year-round.

This solves a couple of different problems. First, many city dwellers live in food deserts, or places where there isn’t a whole lot of fresh produce available. Secondly, traditional agriculture uses massive amounts of water and other resources. And Bowery’s high tech approach allows the business to function in a way that’s both sustainable and not reliant on outdoor weather.

A Great Example of Innovation

What this business shows is that you can put a new spin on almost any industry, as long as you’re willing to get a little creative. Throughout the years, people have come up with plenty of new tools to update agriculture or make certain processes more efficient. But if you’re willing to look at things in a new way, and innovate based on your observations, you can still find ways to update almost any business model.

Image: Bowery

H-E-B-Owned Central Market Partners With CEA Advisors and Growtainer® For Store Grown Initiative

H-E-B-Owned Central Market Partners With CEA Advisors and Growtainer® For Store Grown Initiative

Friday, May. 19th, 2017

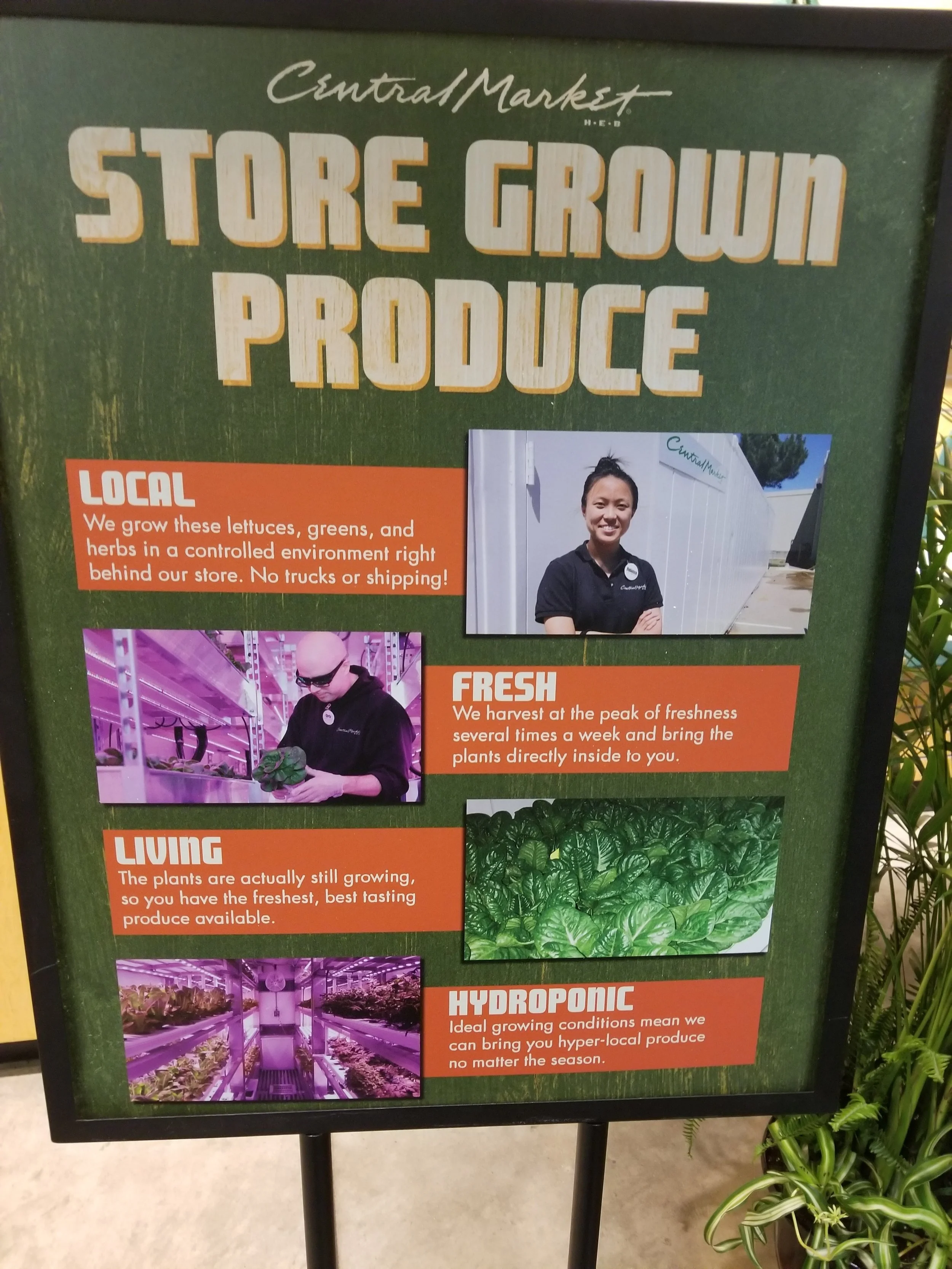

DALLAS, TX – After more than a year of planning between Central Market’s Produce Marketing team and CEA Advisors, the two companies have announced the completing of the first custom built onsite production Growtainer®. Central Market’s new Store Grown Produce program is in effect and turning out fresh leafy greens, herbs, and spices for Central Market customers in Dallas.

Glenn Behrman, Founder, Greentech Agro LLC and CEA Advisors LLC.

“We spent over a year discussing [Central Market’s] concerns and objectives, and when I was sure we were all on the same page, we began the design and manufacturing process” said Glenn Behrman, Founder of Greentech Agro LLC and CEA Advisors LLC.

The state-of-the-art 53-foot custom-built Growtainer provides 480-square-feet of climate-controlled vertical production space designed for maximum efficiency and food safety compliance. The miniature production facility features a dedicated proprietary technology for ebb and flow irrigation and a state-of-the-art water monitoring system, and its Growracks® are equipped with energy efficient LED production modules specifically designed for multilayer cultivation.

Growtainer

According to a press release, Central Market—the Texas-based upscale grocery banner owned by H-E-B—is currently using its Growtainer setup in an effort to “produce the freshest, unique, gourmet leafy greens and herbs for Central Market customers at the retail level.” The release noted that Central Market and CEA Advisors have worked closely with Chris Higgins and Tyler Baras of premier horticultural supplier Hort Americas to train the Central Market associates to operate a food safety compliant, climate controlled, LED-lit, multi-layer vertical indoor production environment.

Central Market storefront

“CEA Advisors is proud to be working with the Produce Team at Central Market, all committed to innovation and focused on food safety, unique products, and the customer experience” said Behrman.

This Texas Supermarket Is Growing Its Own Veggies In A Shipping Container Farm

This Texas Supermarket Is Growing Its Own Veggies In A Shipping Container Farm

Agriculture, Carousel Showcase, News, Sustainable Food, Urban Farming

A Texas chain of supermarkets isn’t just in the business of selling vegetables; it’s growing them, too. Based in Dallas, the H-E-B-owned Central Market has joined forces with Controlled Environment Agriculture Advisors, a self-described “horticulture disrupting” firm, to raise some of its produce in a custom-built onsite shipping container—a first for an American food retailer.

The 53-foot-long “Growtainer” features 480 square feet of climate-controlled and food-compliant vertical space designed to achieve a higher yield in a shorter time than conventional methods, according to GreenTech Agro, the system’s manufacturer.

Related: Belgian supermarket unveils plan to sell food grown on their own rooftop garden

“We spent over a year discussing [Central Market’s] concerns and objectives, and when I was sure we were all on the same page, we began the design and manufacturing process,” said Glenn Behrman, founder of GreenTech Agro and CEA Advisors, in a statement.

The miniature farm comes with a modular, self-contained series of LED-lit aluminum “GrowRacks” that supports any number of cultivation levels.

Related: Pop-up shipping container farm puts a full acre of lettuce in your backyard

It also offers an intelligent water-monitoring system, as well a zoned irrigation system that meets the needs of different varieties of produce at different stages of growth.

The Growtainer is part of Central Market’s efforts to “produce the freshest, unique, gourmet leafy greens and herbs for Central Market customers at the retail level,” the supermarket said. The hyper-local vegetables are marketed under the label “Store-Grown Produce.”

Related: Freight Farms are super efficient hydroponic farms built inside shipping containers

“CEA Advisors is proud to be working with the Produce Team at Central Market, all committed to innovation and focused on food safety, unique products, and the customer experience,” Behrman added.

Sustainable Indoor Farm Aims To Grow The Most Delicious Produce

Sustainable Indoor Farm Aims To Grow The Most Delicious Produce

A San Francisco startup is creating an indoor vertical farm that aspires to produce crops more efficiently and sustainably than traditional farms

- 25 MAY 2017

Indoor vertical farming startup Plenty wants to transform the way greens are produced. The company, headquartered in San Francisco, has created 20-foot towers of rare herbs and greens—including special kinds of basil, chives, mizuna, red leaf lettuce and Siberian kale—that are not frequently available at the average grocery store because of their high production costs.

“When you’re not outside and you’re no longer constrained by the sun, you can do things that make it easier for humans to do work and work faster, and for machines to work faster,” Plenty CEO and co-founder Matt Barnard told Fast Company. The company claims it can grow crops up to 350 times more effectively than conventional farms in a given area. Indoor vertical farms are more energy- and space-efficient, Barnard says, producing the same output as fairly large farms in a far smaller space. He believes that the indoor farming process, once perfected, may become more sustainable than traditional farms.

Plenty is attempting to put ever-improving technology toward its success and plans to build farms near large cities so it can fit into existing supply chains that deliver to city limits. Faster delivery means better food, preserving both flavor and nutrients. Indoor farming also has the potential to be more sustainable by using solar energy and cutting down on the costs and pollutants of traditional supply chains.

Can Hydroponic Lettuce Save Coal Country?

Story by Otis Gray

Illustration by Jia Sung

5.3.17

Can Hydroponic Lettuce Save Coal Country?

Young people tend to talk about “getting out” of McDowell County, West Virginia. But one radical farmer is bringing life back to his struggling hometown.

This story is a collaboration between Narratively and Hungry, a podcast about the food we eat, the people who make it, and the inspiring stories surrounding food you don’t usuall

* * *

Joel McKinney, 33, is thick and tall, with tattooed arms and a backward baseball cap. There’s a restless demeanor exuding from beneath the militaristic dude-ness he must have picked up during his time in the Navy. He slides open the greenhouse door and a warm draft washes out.

On the north side of the greenhouse are two long rows of eight-foot-tall bright white PVC towers standing at attention. From each PVC pipe explodes scores of violently purple and green heads of lettuce growing vertically up the tube. Each plant sits askew in a little cup fitted into its respective hole in the tower. A steady trickle of electricity and water reverberate in the warm tunnel. These are McKinney’s hydroponic lettuce towers.

“People are so stuck on traditional agriculture, and that’s fine, it’s all great. But I’m not growing out, I’m growing up,” he says. “What I’m doin’ with the towers, it’s not just about hydroponics to me. It’s not just about growing food. To me, this thing embraces change.”

A scene off the main road going through McDowell.

The vibrant, futuristic setup is entirely unexpected in a place like McDowell, and that’s kinda the point for McKinney. McDowell is a remote coal county tucked away in rural West Virginia. Back in the late fifties when coal was booming, McDowell’s population was over 100,000. In 2017 that number has dropped below twenty thousand. It has made headlines over the last decade for its daunting economic hardships, rampant opioid use, and most recently, its overwhelming support for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election. But these headlines fail to cover creative people like McKinney who are responding to those circumstances.

McKinney cradles a deep green head of lettuce between his fingers. The towers each sit atop big black buckets with neat tubes running in between, making the greenhouse look like a room full of computer servers as curated by an obsessive farmer. Each bucket is filled with a nutrient-rich solution – water loaded with natural stuff the plants need to grow. A pump system carries the solution to the top of the tower, where it trickles down inside and is directed to the roots of each plant. The roots dangle into the passing solution and soak it all up. The solution then falls back to the bucket, and is cyclically pumped up to the top again. While the physics of it are simple, McKinney has taken extreme care to make these towers as efficient as possible.

McKinney served in the Navy as a machinist mate, and was honorably discharged after spending 2003 to 2007 aboard the USS Trenton. He went in as an engineer, devouring any manuals he could find and ravenously learning the technology of the ship’s systems. The old-school tech used on the ships – the steam-powered stuff, the electronics – captivated McKinney. He excelled among his peers and became the first E-3 Seaman with the title of qualified firearm supervisor in the 35-year history of the USS Trenton. He deployed to Lebanon, Beirut, facilitated an Israeli evacuation, traveled up and down Latin America, and has seen most of the United States.

Joel McKinney with his hydroponic towers.

Something you’d notice driving through McDowell is that there aren’t a whole lot of people McKinney’s age. You generally see children, and then people who look to be at least forty. This is in large part due to the dramatic decline of jobs over the last fifty years, which has forced adults to flee to urban areas in West Virginia, Ohio, and Kentucky, often sending money back to kids they left in McDowell to be raised by grandparents. The younger generation has seen the county rocked by floods, a recession, and an epidemic of opioid addiction that has deterred those who leave from ever coming back.

“I was forced to adapt,” McKinney says. After the Navy, McKinney went to work for the railroad. During the next seven years, he honed his skills in electrical engineering and operating machinery, but quickly plateaued and wound up unchallenged by the job. He got bored and started drinking heavily – “I have a really addictive personality,” he explains – and got a DUI. The DUI led to a suspension from his railroad job, during which time he wound up back in McDowell helping his mom Linda at their food bank. She had one of these towers lying around so, he did what he does best: He started tinkering.

As the coal industry declined, many people here turned to traditional farming for food and profit, but the runoff from the mines made it tough to grow anything, much less anything healthy. Byproducts like arsenic, selenium, mercury, and compaction often ravage otherwise fertile soil in coal-heavy towns. Even if you do produce enough crop to sell, McDowell is secluded enough that the time and money spent on transportation to a viable market would eat up any profits. Hydroponics provided McKinney a way to farm without using the contaminated water, and the cost is so low that folks in McDowell can afford to buy the resulting produce themselves, cutting out the need for costly transportation.

McKinney calculates that the 440 heads of lettuce he has growing in this roughly twenty-by-five-foot area take up less than one-eighth of the space it would take to grow in the ground and uses ninety percent less water. This means that farmers using McKinney’s systems could bypass tainted water, produce year-round, and multiply their crop by ten times each harvest. All without using pesticides, GMOs, or growth chemicals.

The local public school has become one of McKinney’s accounts and buys lettuce for their lunches. As part of the deal, he gets to teach a raucous group of six-year-olds about hydroponics by installing a tower in one of the classrooms. “Man, working on the railroad is a lot like working with kindergartners. But I’m a structured guy, I work with bullet points – so when you go from the military to working with kids. . .”

He fiddles with a tube feeding into one of the buckets and laughs. “I learn a lot from them. I can’t go in with kids and teach like, tropism and nitrogen cycles and covalent bonding, but you go in with kindergartners and you say, ‘okay well, this is lettuce. This is what lettuce should taste like.’”

“Oh my gosh, he thinks he’s horrible with the kids and he’s fantastic. I tell him he needs to be a teacher,” Kimball Elementary school teacher Sarah Diaz says. “Many of our kids are not exposed to varieties of food,” she adds. “So even simple things like a salad with homegrown vegetables and a homemade dressing, that’s a big deal. They love the flavor. We had so many kids coming away saying ‘I really like vegetables!’ Whereas before, they wouldn’t touch it!”

Diaz says the learning doesn’t stop after kindergarten, it has to become embedded in McDowell’s culture. “If we can get people like Joel to plant a fire in these kids and develop a program that allows them to grow with these systems and grow into it, I can see huge potential for change in the next couple generations.”

The question is whether people in McDowell will embrace the new system. McKinney admits that people in McDowell can be a tough bunch to work with because of their deep traditions and weathered attitudes. Folks in McDowell even describe themselves as “good people, but defensive.” This has a lot to do with decades of their livelihood (coal and other big industries) being outsourced, broken promises from the government, and media outlets that portray their home as a hellish wasteland waiting for politicians to come save them.

McKinney says the people of McDowell constantly surprise him with how on board they are with the hydroponics. “People can be pretty close-minded, but hey, man, I’ve been all over the world, these are very good people here in Appalachia.”

Hydroponic Lettuce Towers in Joel McKinney’s greenhouse.

Hydroponic projects in big cities get most of the media attention, focusing on people growing indoors without a lot of space. But it’s wildly useful in rural areas too. “This is absolutely sustainable here,” McKinney says. “It’s something anybody can do and now I’m training people of all ages how to pick this thing up and run with it.”

“The hydroponics is kinda’ a visual for the concept of change. I wanna bring some change into a rural poverty situation,” McKinney says, nodding his head and looking at a crop. “People will say opportunities don’t exist here. And I say, ‘you’re absolutely right. Create it.’ And that’s what we’re doin’, we’re creating a market.”

His operation is applicable to countless rural economies throughout Appalachia and the rest of the U.S. that are primed with mechanically-minded industry families who are in need of better food and sustainable incomes. Coal will not come back permanently. McKinney knows this, and the folks of McDowell know this too. Transitioning into simple yet futuristic agriculture could revolutionize their narrative.

McKinney shuts the door to the greenhouse. “Look,” he says frankly as he walks back across the cold lot. “I don’t believe that lettuce and strawberries are gonna save McDowell.”

Hydroponics are a beginning. An example that there is more. “Kids here, especially once they hit the junior high age, they just feel like there’s no hope, there’s no chance for change. So as soon as they can they say ‘let’s get out of McDowell.’

“I’m really trying to change that logic as best I can. I don’t think it’ll happen in my generation, but I’m hopin’ to kinda be the spark that initiated some change in this place ’cause I believe it can happen. It’s just gonna take a long time.”

Listen to the extended audio version of this story – featuring Senator Bernie Sanders – on the Hungry podcast. You can subscribe to Hungry on iTunes, Stitcher, your podcast app, or via www.hungryradio.org.

Urban Agriculture: Growing Network Wants to Make City Farming Easier

Urban Agriculture: Growing Network Wants to Make City Farming Easier

Courtesy photo This photo from Grow Pittsburgh shows an urban agriculture area in the city.

MAY 24, 2017

CHERIE HICKS - Staff Writer - chicks@altoonamirror.com

Living in the city doesn’t mean you can’t raise a wide variety of your own food. And a growing network of urban agricultural interests in Blair County is trying to make it easier.

Kick-started by a grant last year and joining a nationwide movement, the Blair County Urban Ag Program already has pulled together more than 100 members from different groups — schools, churches, governmental organizations, nonprofit agencies, homeowners, farming interests and more. They are sharing how-to information from raising backyard chickens to gardening with organic practices, and they’re taking lessons from Pittsburgh.

“We’re surrounded by all these big farms, but people living in the city of Altoona are going hungry … because they live in a food desert,” said Beth Futrick, an ombudsman with the Blair County Conservation District and recipient of a $46,000 grant last year to start the urban ag program.

“Food deserts” are large pockets of residences at least a mile from a supermarket or large grocery store where fresh food can be purchased, she said.

“Too many poor people lack transportation to get to Weis so they walk to the closest convenience store” and purchase prepared, processed food, according to Futrick.

Last year, she enlisted the Healthy Blair County Coalition and organized the network’s first event, a tour of a community garden in State College. More than 30 people in the medical field, schools, WIC and other social programs showed up, Futrick said, with one common goal: How to get healthier foods to their customers, their clients, their patients, their students.

“We are trying to reach out to as many people as we can and build a network.”

The grant helps pay for her salary, as well as a consultant, speakers and other education programs, especially to get the word out about the programs, she said.

Tyrone Milling, for example, held a seminar on how to raise backyard chickens, and the network promoted the idea. It is legal to raise chickens in your backyard in Altoona, said Planning Director Lee Slusser, who noted that goats, chickens and rabbits are “great urban animals.”

The City of Altoona mulled an animal husbandry ordinance similar to Pittsburgh’s, but there haven’t been very many complaints so it got shelved for the time being, said Slusser, who is an active member of the urban ag network.

But it still would be unwise, Futrick said, for city residents to have a rooster.

“My dad had a rooster that at 3 o’clock in the morning would go ‘cockadoodle doo’,” she said. “Don’t make your neighbors upset.”

Futrick noted that Pennsylvania has a right-to-farm law that prevents municipalities from getting too strict, though.

“We can regulate how many animals you can own,” such as one cow per acre, Slusser said. “But we can’t ban it outright.”

Another major component of the urban ag network is the Society of St. Vincent DePaul, which has operated the nonprofit Monastery Community Gardens south of Hollidaysburg since 2008. In addition to growing produce for local food banks, the society rents out garden plots and a few are still available this season for $25 or $40. (Contact Kathy Saller at ksaller@netzero.com).

It also sponsors regular gardening classes in conjunction with the urban ag network.

The next education event, a workshop sponsored by the National Association of Conservation Districts, will discuss indoor farming techniques from 9 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. on June 12 at the Logan Valley Mall Community Room. The deadline to register is June 1. Area experts will discuss hydroponics (growing plants without soil); aquaponics (dealing with the relationship between aquaculture, or farming fish, and hydroponics); Bokashi composting (an anaerobic composting method for kitchen scraps, including dairy and meat); and growing microgreens, the immature shoots of edible plants. A $15 fee to attend includes lunch and education credits are available.

A bus trip to Pittsburgh on June 28 ($30 per person) will include visits to several programs of the Grow Pittsburgh program, which formally organized in 2008 and today has 18 full-time staff members.

“We really think about growing food across the city, among all different ages and in all different kinds of communities,” said Jake Seltman, executive director.

Its programs include urban gardens and school gardens, and it provides resources for community gardens throughout Pittsburgh, having started more than 60 of them before turning over their sustainable operations to the communities in which they’re located, he said.

“We provide a lot of resources,” Seltman continued. “We share best practices and make it easier for people to grow their own food.”

Its website (www .GrowPittsburgh.org) is full of resources for urban dwellers.

The Blair urban ag program specifically will visit the Grow Pittsburgh’s Braddock Urban Farm, as well as the Allegheny County Courthouse’s rooftop garden, the Phipps Conserva-tory and Botanical Gardens’ Center for Sustainable Landscapes and the Phipps’ Homegrown program at the Homewood YMCA.

Among the lessons Futrick said she hopes the network can teach to consumers is an understanding of growing seasons and which crops are available here and when.

“They want corn in April,” she said. “We just need to do some customer education. We shouldn’t buy so much from California. There it’s picked to travel, not for good taste.

“We can grow really nice stuff here in Pennsylvania.”

Mirror Staff Writer Cherie Hicks is at 949-7030.

Indoor Farming: On To Pastures New

Indoor Farming: On To Pastures New

24 May 2017 | By Mia Hunt

In the drive for sustainability, new operators are looking to indoor farming to bring food closer to consumers.

Indoor farming - a low-energy, low-water-use way of growing food - Source: Mandy Zammit

Asked to imagine a farm, most people will think of vast green fields filled with neat lines of crops, grazing animals and a tractor trundling along in the distance.

It’s an idyllic visualisation that would be shattered if you were told that the farm were, in fact, on an industrial estate on the edge of a major conurbation.

Say hello to indoor - or vertical - farming, an emerging sector that aims to produce food sustainably, without sunlight or soil and, crucially, close to the retailers that will sell it and the consumers who will eat it.

It is a concept still very much in its infancy, but if this new farming method takes hold, warehouse space will be high on the shopping lists of these new operators. So what is indoor farming? And what are operators’ requirements?

Indoor farming is sustainable and uses less transport. Those who are doing it now are the forward-thinking food producers - David Binks, Cushman & Wakefield

“This is very much a new, emerging sector,” says David Binks, a partner in the industrial team at Cushman & Wakefield.

“The thinking driving this trend is to move food production closer to the source of customers. It’s sustainable and uses less transport, which is a very positive thing. Those who are doing it now are the forward-thinking food producers.”

GrowUp Urban Farms is one such operator.

A year ago it opened Unit84, an indoor farm in an industrial warehouse in Beckton, east London, that had previously lain vacant for 18 months. It claims it is the UK’s first aquaponic, vertical farm.

The farm combines two well-established farming practices: aquaculture, a method of farming fish, and hydroponics, whereby plants are grown in a nutrient solution without soil. It is a low-energy, low-water-use way of growing food that is especially suited to high-density urban agriculture.

The farm’s 6,000 sq ft of growing space produces more than 20,000kg of salads and herbs - enough to fill 200,000 salad bags - and 4,000kg of fish each year. And according to chief executive and co-founder Kate Hofman, GrowUp’s next project will be “10 times bigger”.

“I set up GrowUp with COO and co-founder Tom Webster four years ago,” Hofman explains. “We have different career backgrounds - he was a sustainability consultant for an engineering firm and I was a strategy consultant - but we were both interested in making sustainable urban food production commercially viable.”

Food For Thought

The pair took over the warehouse at London Industrial Park in May 2015 and launched after a comprehensive six-month fit-out process.

“Our 600 sq m [6,500 sq ft] hydro room alone provides 8,000 sq m of growing space because we’re able to grow up as well as along,” says Hofman. “And because it isn’t dependent on environmental and climate factors, we can produce salads of consistent quality 365 days a year.”

Now that Unit84 is fully up and running, Hofman and Webster are looking ahead to their next project - a considerably larger farm for which the firm will soon work up a design that will enable it to make even more efficient use of space. This next farm will be the blueprint for a model that can be rolled out to many different locations on a franchise basis.

Indoor farming uses hydroponics, whereby plants are grown in a nutrient solution without soil - Source: Mandy Zammit

Hofman says a standard warehouse is the ideal place for vertical farming and lists requirements similar to those of light industry, including locations within easy reach of customers - GrowUp distributes all of its produce itself using electric vehicles - and with good access and packing space.

“From what I’ve seen, read and heard, these operators need decent utility access - predominantly renewable energy to power the artificial lights that are used in place of sunlight - although they require very little water, significantly less than a traditional farm,” says Binks. “They need to be heated and cooled efficiently. And because they use a degree of technology to support the growing methods, that may be a consideration in their requirements.”

Looking Up

Binks believes old multi-level industrial buildings are well suited to vertical farming. “Former textile factories and other such buildings built in the early 1900s on the outskirts of towns and therefore in close proximity to the customer base would probably work well,” he says. “If they are at a cost base that is affordable for these operators, they could potentially bring very old, dilapidated buildings that have been redundant for years back into use.”

However, he highlights that residential developers are often at the front of the queue for these types of buildings and, as such, indoor farming operators could struggle to secure buildings.

“It’s a challenge and it could be a barrier to entry,” he says. “But where they find the right building in the right location that hasn’t been earmarked for residential use, I don’t see why they couldn’t bring it forward. They might also occupy fairly new industrial buildings with mezzanines.”

Source: Mandy Zammit

New buildings are a consideration for GrowUp. Hofman explains that they could convert an old warehouse, depending on the age and quality of the building, but the retrofitting costs are huge, so it could look to partner with developers to create the right space for its specific needs from scratch. And it isn’t only industrial space that is on GrowUp’s shopping list. It could also operate from big-box units on retail parks.

“At a time when businesses are becoming increasingly streamlined operationally and focusing on last-mile delivery, huge out-of-town retail spaces could become vacant,” says Hofman. “Landlords are already looking for alternative uses - we could be it.”

We are utilising ways of growing food that make sense commercially and environmentally - Kate Hofman, GrowUp

When it comes to planning, the sustainability and community benefits of indoor farming are such that Binks believes local authorities would be in favour of vertical farming uses. However, there is a caveat.

“There is some debate as to how employment generative they are,” he says.

“If they use automatic feeding systems, there might only be a need for a handful of year-round on-site staff and a short-term need for extra staff during the picking season. Operators may have to persuade councils that it’s a good thing for their boroughs.”

Question Marks

Planning isn’t the only potential hurdle that may need to be overcome. While it can be done profitably, Binks says this new farming technique is so innovative that thus far it is only private investors who are investing in it.

Aquaculture is a method of farming fish -Source: Mandy Zammit

“There is a question mark over the covenant strength of these types of occupiers,” he explains. “For now, the sector is so new that landlords and developers aren’t considering this to be a new or potential major occupier category. But perhaps they ought to be - indoor farming is flying under the radar.” He adds that the landed estates might pursue these tenants in a bid to showcase a forward-thinking approach.

As for the future, a number of factors could accelerate the growth of these types of farm, as Hofman explains: “Brexit could have an impact on imported foods and imported labour. Couple that with climate changes affecting farming in countries that supply the UK with much of its produce, including floods in Spain and droughts in California, and a growing desire by retailers to sell and consumers to eat locally produced food, and I see this [indoor farming] as the answer. We are utilising ways of growing food that make sense environmentally and commercially - it is an attractive investment.”

There may be questions over the viability of indoor farming but, in a changing world, its future could well be bright. This new method of food production has not yet piqued the interest of industrial landlords or institutional investors - but perhaps now is the time to take notice of a trend that is likely to grow.

The World’s Smallest Garden is Created in New York City

The World’s Smallest Garden is Created in New York City

Nate Littlewood and Rob Elliott have created The World’s Smallest Garden, a device which turns an empty bottle into a hydroponic garden.

After meeting at Columbia University in early 2016, the co-founders combined their skills in business and food growing systems to launch this first product, which is intended for beginning growers to use in their home. Setup for the product should only take about 60 seconds, by placing the small, biodegradable plastic device into the top of a bottle—such as a whiskey or wine bottle.

With UrbanLeaf, Littlewood and Elliott hope to create an experience which helps people reconnect with their food. Food Tank had a chance to speak with Nate Littlewood about the inspiration behind UrbanLeaf and challenges he and his partner have faced along the way.

Food Tank (FT): What was the inspiration that led to creating the UrbanLeaf product?

Nathan Littlewood (NL): We wanted to show people that growing food at home could be fun, easy, and accessible. Through over 200 customer interviews, we feel we’ve developed a pretty good handle on the sorts of challenges and obstacles that amateur urban farmers face.

Nine times out of ten, home gardens fail because people forget to water them. The World’s Smallest Garden solves this problem in the simplest, most elegant, and cost-effective way we could imagine. It provides a way for plants to water themselves. We also like that it repurposes something that is available locally (an empty bottle) to create the hydroponic reservoir. In doing so, we eliminate the need to make an injection molded plastic reservoir and import it from overseas. The small amount of plastic we do use in our product is biodegradable. It costs us a bit more, but we feel this is money well spent.

FT: What has been your biggest challenge in developing UrbanLeaf?

NL: It’s been really hard finding hardware know-how and expertise here in New York. There’s a ton of people that understand tech and services based businesses, but widget producers are few and far between! We were recently accepted into FutureWorks, which is a hardware-specific Incubator Program. It seems like an amazing community and we’re looking forward to getting more involved!

FT: How do hydroponics contribute to a more sustainable food system?

NL: Hydroponics opens up new possibilities for food-system design. It doesn’t rely on clearing land, soil quality, large open spaces, and the right season. Hydroponics is very well suited to growing food in urban environments. It’s stackable, it can go vertical, and it can be modular. It allows us to conceive food system designs that involve shorter supply chains, fewer food miles, less weather vulnerability, less wastage, and less packaging.

UrbanLeaf co-founders Nate Littlewood and Rob Elliott. | Photo courtesy of UrbanLeaf

FT: What piece of advice would you give to early entrepreneurs trying to make an impact in the food system?

NL: Emily, you’d know better than most about the level of interest growing around food and sustainability—and I’m sure you’ll agree that this is a good thing. Whilst it’s encouraging to see so many bright, talented, and motivated people entering this space, coming from a business background, I do worry that food businesses generally have low barriers to entry. I fear that a lot of people are going to burn a lot of capital over the next 5 to 10 years learning hard lessons about the importance of competitive advantage. As a producer of consumer hydroponics products, this is something I worry about more than most! My advice is to remember that you can’t pay your rent with passion—most landlords require dollars.

FT: What inspires you to keep working towards food system change every day?

NL: When I’m an old man, and I tell my grandchildren what I’ve done with my life, I want them to be so excited about the answer that they go to school the next day and tell all their friends about it. I’m only in my 30s, so the grandkids are some way off, but the quality of the environmental legacy that I leave behind for them is why I’m doing this. I want them to be able to enjoy the great outdoors in the same way I have. I’m also 100-percent confident that we can improve the quality of thousands of peoples’ lives along the way by providing an experience that helps them reconnect with food.

FT: You’ve mentioned that The World’s Smallest Garden is only a first step towards building a future where food is fresh, local, and personal. What is your vision for UrbanLeaf down the road?

NL: Our goal is to make our customers happy, and to show people that growing their own food can be fun, easy, and accessible. The World’s Smallest Garden is the perfect product to start with both for us as a company and for consumers who are new to this space. Ultimately we want to grow with our customers, and we have a really exciting pipeline of new products that we’ll be releasing over the next few years. I’ll tell you more about that in our next interview!

What is Urban Agriculture?

Welcome!

Are you interested in starting an urban farm? Seeking details on how to raise backyard chickens and bees? Looking for information on laws, zoning and regulations that relate to urban agriculture? We offer resources on small-scale production, including soil, planting, irrigation, pest management, and harvesting, as well as information on the business of farming, such as how to market urban farm products.

After you explore the site, please complete our survey! We’d like to know if you found what you were looking for and hear your suggestions.

Benefits of Urban Agriculture

Urban agriculture can positively impact communities in many ways. It can improve access to healthy food, promote community development, and create jobs. A number of cities in California, including San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego have recently updated municipal policies to facilitate urban agriculture, due to strong community interest. If you’d like to learn more about some documented impacts of urban agriculture, see Research.

Challenges of Urban Agriculture

Despite the benefits associated with urban agriculture, there are many challenges. Urban farmers routinely face issues related to zoning, soil, water access, and profitability, as a few examples. At the community level, noise and nuisance issues can come into play. This site is intended to share the research on both benefits and challenges, and best practices on how to address those as a farmer or local decision maker.

Who We Are

UC ANR is part of the nation’s land grant university system, with more than a century of experience providing research-based knowledge to California farmers. This site offers resources that we’ve identified as most useful for urban farmers and local decision makers and stakeholders. Additionally, we are identifying gaps where resources need to be developed. Our team includes more than 15 experts, ranging from UC farm advisors, to agricultural economists, to urban planners and policy makers.

How Millennials Will Forever Change America’s Farmlands

How Millennials Will Forever Change America’s Farmlands

[This article originally appeared in Fortune on March 21, 2017]

Square Roots co-founders Kimbal Musk and Tobias Peggs with the first cohort of urban farmer entrepreneurs on the Brooklyn- based Square Roots vertical farming campus.

As Americans increasingly reject cheap, processed food and embrace high-quality, responsibly-sourced nutrition, hyper-local farming is having a moment.

Tiny plots on rooftops and small backyards are popping up all across America, particularly in urban areas that have never been associated with food production. These micro-farms aren’t meant to earn a profit or feed vast numbers of people, but they reflect the Millennial generation’s desire to forge a direct connection with the food they consume.

These efforts are an admirable manifestation of the mantra to think globally and act locally, but they miss the opportunity that is going on right now: the economics of branded local farms have changed, and technology in agriculture has led to a renaissance of independent American farming. Whether this means farming the traditional acreage of the Heartland or adapting to cutting-edge indoor farming methods, the result is the same: demand for real food is far outstripping supply. Highly-educated, entrepreneurial, and socially conscious young people have a great opportunity to think seriously about agriculture as a career.

On the surface, this advice sounds dubious, given the well-documented, decades-long decline of independent farming in America. Between 2007 and 2012, the number of active farmers in America dropped by 100,000 and the number of new farmers fell by more than 20%. Ironically, however, the titanic, faceless factory farms are barely eking out a profit. That often means that an independent 100-acre farm growing high-demand crops can be far more profitable than a 10,000-acre commodity farm growing corn that may end up getting wasted as ethanol.

The key to reviving America’s agricultural economy is casting aside the sentimental images we associate with farming — starting with what a farmer looks like. In recent years, many of the same technologies that have revolutionized the consumer world have fundamentally altered and improved the way we farm. Drones, satellites, autonomous tractors and robotics are now all at home on farms. As a result, tomorrow’s farms won’t just be part of the agricultural sector, they’ll also be part of the tech sector — and tomorrow’s farmers will look a whole lot like the coders who populate Silicon Valley…except with better tans.

The next assumption about farming we need to cast aside is what a farm looks like and where it will be found. The vast planting fields of America’s heartland are going to change by adjusting to grow real food with 21st century technology, but tomorrow’s farms will also be vertical and in or near our urban centers. By 2050, 70 percent of the global population will live in cities. As both a social imperative and a practical matter, it makes sense to grow food near these cities, rather than to waste time and resources delivering products from hundreds or even thousands of miles away.

Square Roots urban farming campus in Brooklyn, NY.

This will require innovative new technology that will create even more flexibility in the way we farm. With this in mind, I recently co-founded Square Roots, a social enterprise that aims to accelerate urban farming by empowering thousands of young Americans to become real food entrepreneurs. We create campuses of climate-controlled, indoor hydroponic farms in the heart of our biggest cities and train entrepreneurs how to grow and sell their food year-round. After their training, these young entrepreneurial farmers, in partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, can qualify for larger loan programs as a next step to owning their own farm — either soil-based or indoor. Whether they move on to their own farm or another business, they are prepared to build forward-thinking companies that will become profitable and create good jobs.

Greens growing vertically with a Square Roots farmer entrepreneur in the background. Photo Courtesy Square Roots

We are investing in this initiative not only because it’s the right thing to do, but also because we are confident that agriculture is poised for explosive growth, and that technology and the power of locally branded farms will be the keystone to success. Just ask self-described “AgTech nerds” like Sarah Mock, who is a leader in the growing movement of Millennial entrepreneurs who see an opportunity in farming to achieve the double bottom line — value and values — that is key to solving our planet’s toughest challenges.

Private enterprise will lead this revolution, but the federal government must help fuel its growth. The 2018 farm bill is a critical opportunity. This massive legislation, renegotiated by Congress every five years, establishes the blueprint and funding priorities across America’s agricultural sector. Last year, Democratic U.S. Senator Debbie Stabenow of Michigan introduced forward-looking legislation called the Urban Agriculture Act that would offer protections and loan options that are currently available only to traditional rural farmers. Ideas like these are essential.

A future in which our food is safer, healthier and environmentally sustainable can exist alongside one in which our agricultural economy grows and creates good jobs for millions of American workers. The technologies and business practices of modern farming is spreading rapidly. The opportunity for a young farmer has never been better — and it’s a future we can all get behind.

The Power of a Plant – Green Bronx Machine

Globally acclaimed teacher, Stephen Ritz, author of “The Power of a Plant” shows how in one of the nation’s poorest communities, his students thrive in school and in life by growing, cooking, eating, and sharing the bounty of their green classroom

The Power of a Plant – Green Bronx Machine

Globally acclaimed teacher, Stephen Ritz, author of “The Power of a Plant” shows how in one of the nation’s poorest communities, his students thrive in school and in life by growing, cooking, eating, and sharing the bounty of their green classroom. His innovative program began by accident. When a flower broke up a brawl among burly teenagers at a tough South Bronx high school, Stephen saw a teachable moment to connect students with nature.

By using plants as an entry point for all learning, he witnessed nothing short of a transformation. Attendance soared from 40 to 93 percent. Disciplinary issues plummeted. In a school with a 17 percent graduation rate and high crime rate, every one of his students finished school and stayed out of jail. More than 50,000 pounds of vegetables later, he has figured out how to bring the magic of gardening into the heart of the school day for students of all ages.

Shanghai Goes Green: District With Towering Vertical Farms May Become A Reality In The Near Future

Shanghai Goes Green: District With Towering Vertical Farms May Become A Reality In The Near Future

Saturday, May 20, 2017 by: Frances Bloomfield

Tags: agriculture, China, Shanghai, Sunqiao, Urban agriculture

(Natural News) From towering symbols of urbanization, the skyscrapers of Shanghai may soon become agrarian wellsprings. Such is the plan for Sunqiao Urban Agricultural District, a 250-acre district where people will live, work, and shop while surrounded by massive vertical farming systems. Sasaki, the US-based architectural firm behind this bold undertaking, has called Sunqiao “a new approach to urban agriculture” and a “playful, and socially-engaging experience that presents urban agriculture as a dynamic living laboratory for innovation and education.”

Set to be constructed between Shanghai Pudong International Airport and the center of the city, Sunqiao will include all the civic essentials like housing, restaurants, and stores. Amidst all these, however, will be floating greenhouses, seed libraries, and algae farms. These will serve as an expansion of a Shanghai government project that began in the mid-1990’s, wherein a 3.6-square-mile area of the city was designated for agricultural production. Prior to Sasaki’s involvement, only three single-story greenhouses had been built.

The design firm hopes to change that. One major intended use for these is to meet the food requirements of Shanghai’s 24 million-strong population. Leafy greens like kale, bok choi, watercress and spinach make up a large part of the vegetables consumed by the Shanghainese on a daily basis; these same leafy greens do well in simple agricultural setups and require little attention to thrive, making them “an excellent choice for hydroponic and aquaponic growing systems.” Furthermore, these leafy greens are light in weight and grow quickly, making them highly-efficient, economically-viable choices for cultivation as well as food production. Michael Grove, director of Sasaki’s Shanghai office, stated that the district may also have vertical aquaponic fish farms in the future. (Related: The Technologies Making Vertical Farming a Reality)

Sasaki has even called Shanghai “the ideal context for vertical farming”, with its soaring land prices that make building up rather than building out the more prudent option. This goes hand-in-hand with the fact that over 13 percent of China’s total Gross Domestic Product comes from the country’s agricultural sector — the same agricultural sector that feeds 20 percent of the world’s population. Compare this to the United States, of whose agriculture industry only contributes to 5.7 percent of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product.

With over 200,000 kilometers of the country’s arable land now suffering from soil pollution, and 123,000 kilometers of farmland since lost to urbanization, the vertical farms of Sunqiao will become more important than ever. The threats of water shortages, deforestation, and many other complications that continue to affect small farms may soon be things of the past as investments are poured into the modernization and mechanization of the agricultural sector.

According to Sasaki, construction will begin in late 2017 or early 2018. The measurements for Sunqiao are as follows: 753,00-square feet of vertical farms, 717,000-square feet of housing, 138,000-square feet of commercial space, and 856,000-square feet of public space. Development and maintenance will be done by Shanghai Sunqiao Modern Agriculture United Development Co. Ltd., a Chinese company that develops and produces fertilizer. The company will be working together with local planning officials, reported Futurism.com.

Of the project, Sasaki has emphasized the need to balance the agrarian with the metropolitan, stating: “As cities continue to expand, we must continue to challenge the dichotomy between what is urban and what is rural.”

This Uptown Urban Farm Is Growing Career Opportunities for Kids Throughout the City | Edible Manhattan

This Uptown Urban Farm Is Growing Career Opportunities for Kids Throughout the City | Edible Manhattan

By Sarah McColl

Photos by Corinne Singer

“We want to capture whatever spark the children have and try to nurture it, even if it’s well outside the realm of agriculture,” Vincent says.

Up the street from the Apollo Theater, a lot on West 134th Street was once home to prowling neighborhood cats, abandoned engine parts and men playing dominos. With the vision of founder Tony Hillery, the kids of Harlem Grown’s youth farm, a truckload of soil from Home Depot and 400 strawberry plants, the makeshift junkyard has been a blooming Eden since 2011. Now, an arbor casts a low ceiling of leafy shade and a sign warns with a wink that, “Trespassers will be composted.”

The mission of this urban youth farm has never been rootbound. While lessons in nutrition and agriculture happen over hydroponics, and conversations about economic, social and food justice unfold between the garden rows, Harlem Grown is also connecting schoolchildren with professional mentors, internships and career connections.

“We’re trying to use the farms and food as a vehicle to inspire change beyond the plate,” says development director Vanessa Vincent. “We’ve been able to connect our youth to opportunities beyond their wildest dreams.”

Related:

Five Questions with Tony Hillery, Founder of Harlem Grown | Food Tank

Edible Manhattan: A Self-Guided Dominican Food Tour of Washington Heights & Inwood

At Harlem Shambles, The Meat is Worth the Trip | Edible Manhattan

Under the Tracks and Off the Grid, Urban Garden Center Rises Up | Edible Manhattan

Uptown, a Dominican Confection Makes Life Three Times Sweeter | Edible Manhattan

We invite you to subscribe to the weekly Uptown Love newsletter, like our Facebook page and follow us on Twitter & Instagram or e-mail us at UptownCollective@gmail.com.

PurePonics Is Planted In Geelong, Victoria

PurePonics Is Planted In Geelong, Victoria

Last Friday the PurePonics team planted the first crop in the brand new aquaponics facility in Geelong, Victoria.

A great milestone and now our sights are set on the first harvest in around 5 weeks time and getting the finest ingredients into the hands of our customers.

Thanks for following along with our progress and we look forward to providing plenty of interesting and exciting news around food production, urban farming and the beauty of aquaponics in protected cropping.

Follow us on Facebook - PurePonicsAUS

Where the Mouths Are: A Farm Grows In The City

May 21, 2017

Where the Mouths Are: A Farm Grows In The City

Relatively inexpensive space in underutilized urban areas, close to where the majority of the population will live for the foreseeable future.

It makes too much sense not to seize the opportunity. JL

Betsy McKay reports in the Wall Street Journal:

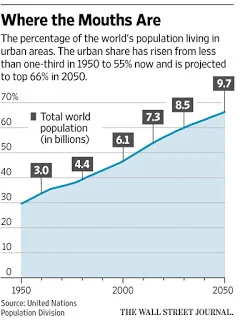

The world’s population is to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, 33% more than today. Two-thirds of them are expected to live in cities. Getting food to people who live far from farms is costly and strains natural resources. Startups and city authorities are finding ways to grow food closer to home. High-tech “vertical farms” are sprouting in rows, fed by water and LED lights, customized to control size, texture or other characteristic of a plant.

Billions of people around the world live far from where their food is grown.

It’s a big disconnect in modern life. And it may be about to change.

The world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, 33% more people than are on the planet today, according to projections from the United Nations. About two-thirds of them are expected to live in cities, continuing a migration that has been under way around the world for years.

That’s a lot of mouths to feed, particularly in urban areas. Getting food to people who live far from farms—sometimes hundreds or thousands of miles away—is costly and strains natural resources. And heavy rains, droughts and other extreme weather events can threaten supplies.

Now more startups and city authorities are finding ways to grow food closer to home. High-tech “vertical farms” are sprouting inside warehouses and shipping containers, where lettuce and other greens grow without soil, stacked in horizontal or vertical rows and fed by water and LED lights, which can be customized to control the size, texture or other characteristic of a plant.

Companies are also engineering new ways to grow vegetables in smaller spaces, such as walls, rooftops, balconies, abandoned lots—and kitchens. They’re out to take advantage of a city’s resources, composting food waste and capturing rainwater as it runs off buildings or parking lots.

“We’re currently seeing the biggest movement of humans in the history of the planet, with rural people moving into cities across the world,” says Brendan Condon, co-founder and director of Biofilta Ltd., an Australian environmental-engineering company marketing a “closed-loop” gardening system that aims to use compost and rainwater runoff. “We’ve got rooftops, car parks, walls, balconies. If we can turn these city spaces into farms, then we’re reducing food miles down to food meters.”

Moving beyond experiments

Urban farming isn’t easy. It can require significant investment, and there are bureaucratic hurdles to overcome. Many companies have yet to turn a profit, experts say. A few companies have already failed, and urban-farming experts say many more will be weeded out in the coming years.

But commercial vertical farms are well beyond experimental. Companies such as AeroFarms, owned by Dream Holdings Inc., and Urban Produce LLC have designed and operate commercial vertical farms that aim to deliver supplies of greens on a mass scale more cheaply and reliably to cities, by growing food locally indoors year round.

At its headquarters in Irvine, Calif., Urban Produce grows baby kale, wheatgrass and other organic greens in neat rows on shelves stacked 25 high that rotate constantly, as if on a conveyor belt, around the floor of a windowless warehouse. Computer programs determine how much water and LED light the plants receive. Sixteen acres of food grow on a floor measuring an eighth of an acre.

Its “high-density vertical growing system,” which Urban Produce patented, can lower fuel and shipping costs for produce, uses 80% less fertilizer than conventional growing methods, and generates its own filtered water for its produce from humidity in the air, says Edwin Horton Jr., the company’s president and chief executive officer.

“Our ultimate goal is to be completely off the grid,” Mr. Horton says.

The company sells the greens to grocers, juice makers and food-service companies, and is in talks to license the growing system to groups in cities around the world, he says. “We want to build these in cities, and we want to employ local people,” he says.

AeroFarms has built a 70,000-square-foot vertical farm in a former steel plant in Newark, N.J., where it is growing leafy greens like arugula and kale aeroponically—a technique in which plant roots are suspended in the air and nourished by a nutrient mist and oxygen—in trays stacked 36 feet high.

The company, which supplies stores from Delaware to Connecticut, has more than $50 million in investment from Prudential, Goldman Sachs and other investors, and aims to install its systems in other cities globally, says David Rosenberg, its chief executive officer. “We envision a farm in cities all over the world,” he says.

AeroFarms says it is offering project management and other services to urban organizations as a partner in the 100 Resilient Cities network of cities that are working on preparing themselves better for 21st century challenges such as food and water shortages.

The bottom line

Still, these farms can’t supply a city’s entire food demand. So far, vertical farms grow mostly leafy greens, because the crops can be turned over quickly, generating cash flow easily in a business that requires extensive capital investment, says Henry Gordon-Smith, managing director of Blue Planet Consulting Services LLC, a Brooklyn, N.Y., company that specializes in the design, implementation and operation of urban agricultural projects globally.

The greens can also be marketed as locally grown to consumers who are seeking fresh produce.

Other types of vegetables require more space. Growing fruits like avocados under LED light might not make sense economically, says Mr. Gordon-Smith.

“Light costs money, so growing an avocado under LED lights to only get the fruit to sell is a challenge,” he says.

And the farms aren’t likely to grow wheat, rice or other commodities that provide much of a daily diet, because there is less of a need for them to be fresh, Mr. Gordon-Smith says. They can be stored and shipped efficiently, he says.

The farms are also costly to start and run. AeroFarms has yet to turn a profit, though Mr. Rosenberg says he expects the company to become profitable in a few months, as its new farm helps it reach a new scale of production. Urban Produce became profitable earlier this year partly by focusing on specialty crops such as microgreens—the first shoots of greens that come up from the seeds—that enerally grow indoors in a very condensed space, says Mr. Horton, who started the company in 2014.

One of the first commercial vertical-farming companies in the U.S., FarmedHere LLC, closed a 90,000 square-foot farm in a Chicago suburb and merged with another company late last year. “We’ve learned a lot of lessons,” says co-founder Paul Hardej.

Among them: Operating in cities is expensive. The company should have built its first farm in a suburb rather than a Chicago neighborhood, Mr. Hardej says. Real estate would have been cheaper.

“We could have been 10 or 20 miles away and still be a local producer,” Mr. Hardej says.

The company also might have been able to work with a smaller local government to get permits and rework zoning and other regulations, because indoor farming was a new type of land use, Mr. Hardej says. While FarmedHere produced some crops profitably, it spent a lot on overhead for lawyers and accountants “to deal with the regulations,” he says.

Mr. Hardej is now co-founder and chief executive officer of Civic Farms LLC, a company that develops a “2.0” version of the vertical farm, he says—more efficient operations that take into account the lessons learned. Civic Farms is collaborating with the University of Arizona on a research and development center at Biosphere 2, the Earth science research facility in Oracle, Ariz., where it runs a vertical farm and develops new technologies.

Blossoming tech

New technology will improve the economic viability of vertical farms, says Mr. Gordon-Smith. New cameras, sensors and smartphone apps help monitor plant growth. One company is even developing augmented-reality glasses that can show workers which plants to pick, Mr. Gordon-Smith says.

“That is making the payback look a lot better,” he says. “The future is bright for vertical farming, but if you’re building a vertical farm today, be ready for a challenge.”

Some cities are trying to propagate more urban farms and ease the regulatory burden of setting them up. Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed created the post of urban agriculture director in December 2015, with a goal of putting local healthy food within a half-mile of 75% of the city’s residents by 2020. The job includes attracting urban-farming projects to Atlanta and helping projects obtain funding and permits, says Mario Cambardella, who holds the director title. “I want to be ahead of the curve; I don’t want to be behind,” he says.

Many groups are taking more low-tech or smaller-scale approaches. A program called BetterLife Growers Inc. in Atlanta plans to break ground this fall on a series of greenhouses in an underserved area of the city, where it will grow lettuce and herbs in 2,900 “tower gardens,” thick trunks that stand in large tubs. The plants will be propagated in rock wool, a growing medium consisting of cotton-candy-like fibers made of a melted combination of rock and sand, and then placed into pods in the columns, where they will be regularly watered with a nutrient solution pumped through the tower, says Ellen Macht, president of BetterLife Growers.

The produce will be sold to local educational and medical institutions. “What we wanted to do was create jobs and come up with a product that institutions could use,” she says.

The $12.5 million project is funded in part by a loan from the city of Atlanta, with Mr. Cambardella helping by educating grant managers on the growing system and its importance.

Change at home

Another company aims to bring vertical farming to the kitchen. Agrilution GmbH, based in Munich, Germany, plans to start selling a “plantCube” later this year that looks like a mini-refrigerator and grows greens using LED lights and an automatic watering system that can be controlled from a smartphone. “The idea is to really make it a commodity kitchen device,” says Max Loessl, Agrilution’s co-founder and chief executive officer, of the appliance, which will cost 2,000 euros—about $2,200—initially.

The goal is to sell enough to bring the price down, so that in five years the appliance is affordable enough for most people in the developed world, Mr. Loessl says.

Biofilta, the company Mr. Condon co-founded, is marketing the Foodwall, a modular system of connected containers, an approach that he calls “deliberately low tech” because it doesn’t require electricity or computers to operate. The tubs are filled with a soil-based mix and a “wicking garden-bed technology” that stores and sucks water up from the bottom of the tub to nourish the plants without the need for pumps. The plants need to be watered just once a week in summer, or every three to four weeks in the winter, says Chief Executive Marc Noyce. The tubs can be connected vertically or horizontally on rooftops, balconies or backyards. “We’ve made this gardening for dummies,” Mr. Noyce says.

The Foodwall can use composted food waste and harvested rainwater, helping to turn cities into “closed-loop food-production powerhouses,” Mr. Condon says.

He and Mr. Noyce were motivated to design the Foodwall by a projection from local experts that only 18% of the food consumed in their home city of Melbourne, Australia, will be grown locally by 2050, compared with 41% today, Mr. Noyce says.

“We were shocked,” says Mr. Noyce. “We’re going to be beholden to other states and other countries dictating our pricing for our own food.”

“Then we started to look at this trend around the world and found it was exactly the same,” he says.

Traditional, rural farming is far from being replaced by all of these new technologies, experts say. The need for food is simply too great. But urban projects can provide a steady supply of fresh produce, helping to improve diets and make a city’s food supply more secure, they say.

“While rural farmers will remain essential to feeding cities, cleverly designed urban farming can produce most of the vegetable requirements of a city,” Mr. Condon says.

Ikea’s Flatpack Vertical Garden Can Feed an Entire Neighborhood!

Ikea’s Flatpack Vertical Garden Can Feed an Entire Neighborhood!

February 27, 2017 by Admin Leave a Comment

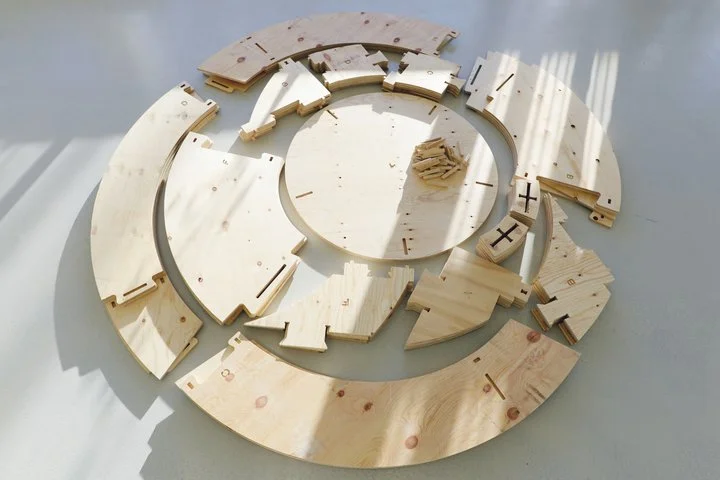

Ikea has come up with a flatpack garden so city dwellers with little space can enjoy a green patch all of their own. The Swedish furniture giant has launched the Growroom – a DIY 9ft tall sphere for nurturing plants, vegetables and herbs that you can actually sit in with your family and friends.