Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Partnership Brings Fresh, Eco-Friendly Produce to Area Hospitals, Clinics

Partnership Brings Fresh, Eco-Friendly Produce to Area Hospitals, Clinics

Published May 30, 2017 at 7:00 am

Lakeview Hospital Nutrition Services employee Kristal Anderson with a fresh delivery of Urban Organics salad greens to the hospital kitchen. (Submitted photo)

An new partnership between Urban Organics and four HealthPartners hospitals and clinics in the St. Croix Valley has made it simpler for patients and health care staff to be eco-friendly.

Urban Organics is an organic aquaponic farm in St. Paul.

Under the partnership — which Lakeview Health believes to be the first of its kind in Minnesota between a health system and an aquaponic farm — salad greens are provided by Urban Organics, which has converted an old brewery in St. Paul into one of the first USDA-certified organic aquaponic farms in the country. Urban Organics delivers organic salad greens to each of the four participating HealthPartners hospitals or clinics within 24 hours of harvest.

Aquaponics is a farming method where fish and plants help each other grow, with the aim of mimicking what happens organically in nature. Aquaponics uses 2 percent of the water used in conventional farming, and produce can be grown and harvested year-round.

“It’s something that people can trust,” said Urban Organics co-founder Kristen Haider of the farm’s produce. “It’s coming from a reliable source. It’s local, the produce is organic and we’re using a sustainable method of farming. It’s a different way of looking at it.”

The pilot project at Lakeview Hospital (Stillwater), Hudson Hospital & Clinic, Westfields Hospital & Clinic (New Richmond, Wis.) and Stillwater Medical Group has been received well, according to Lakeview.

“Fresh and sustainably grown foods are an important part of our commitment to health,” said Ted Wegleitner, CEO and President of Lakeview Hospital. “We were excited about this opportunity to partner with Urban Organics to provide these delicious, nutritious salad greens in our patient meals and our campus cafeterias. The feedback we’ve heard from patients and employees confirmed that this was a good decision.”

Urban Organics salad greens have been used in patient meals and cafeteria salad bars since December. A trial retail option – Greens To Go – offering patients, employees and visitors the chance to purchase 5 oz take-home containers of the salad blends went live this month after a successful trial in March.

Pentair, Urban Organics Open Aquaponics Farm In Old Schmidt Brewery

Pentair, Urban Organics Open Aquaponics Farm In Old Schmidt Brewery

One of Nancy Espinosa's jobs at Urban Organics is placing plants into their pods to continue growing. About 475,000 pounds of organic greens will be produced.

— Elizabeth Flores, Star Tribune.

By DEE DEPASS , STAR TRIBUNE

June 04, 2017 - 2:00 PM

Urban Organics worker Lee Scoggins flicked a cup of powder into a large blue pool and watched as 50,000 tiny salmon, each the size of a paper clip, darted toward dinner inside the newly converted old Schmidt Brewery plant in St. Paul.

The 8-week-old fish that will grow into 10-pound beauties over the next year were introduced to an enthusiastic crowd Thursday as part of the grand opening of Urban Organics' and Pentair's second indoor fish and produce farm, one of the largest commercial aquaponics facilities in the world.

Waste produced by 150,000 fish will help fertilize produce grown on aqua beds on the other side of the facility. The estimated $12 million project — certified as an organic farm by the U.S. Department of Agriculture — boasts 87,000 square feet and is 10 times larger than Urban Organics' and Pentair's first facility, which opened in the converted Hamm's brewery in St. Paul in 2014.

"It's a very exciting time for us," Dave Haider, who founded Urban Organics with his wife, Kristen, and Fred Haberman and Chris Ames, told the crowd at the opening. "Six years ago, my wife said, 'You know. We should open a [aquaponics] farm. We could do that.' "

The key was an unlikely pairing with Pentair, a $5 billion Wall Street stronghold, that almost didn't happen.

"At first, [Haider] wouldn't return my calls," said Bob Miller, chief financial officer of Pentair's aquatic water system business.

Haider sheepishly smiled. "It's true," he said.

Then Miller emphasized in a voice message that Pentair is a filtration expert that could probably help the tiny Urban Organics company with a host of equipment and engineering solutions. Pentair also wanted to prove fish and produce aquaponics farms are viable commercial concerns that can solve food shortage problems, Miller said.

With an added boost from the city of St. Paul, the partners were on their way to creating their new business.

The partnership works, Miller said, because both entities are committed to finding farming techniques that use less water and energy, and protein that is free of antibiotics and pesticides.

Urban Organics will use Pentair's advanced pumps, filters, aerators, mineralization systems and more at the Schmidt site to raise 275,00 pounds of Atlantic salmon and arctic char fish each year. About 475,000 pounds of organic greens including kale, bok choy and arugula also will be produced. The new operation should be at full capacity next year.

The new facility broadens Urban Organics' product offerings. The existing tiny Hamm's building raises striped bass and tilapia and grows basil, kale, watercress and Swiss chard.

With the two facilities, Urban Organics will serve customers across the Midwest, including the Fish Guys, Hy-Vee, Lunds & Byerlys and Co-Op Partners Warehouse in St. Paul.

"We are very excited about this partnership ... and have heard a lot of great feedback from both our patients and employees," said Ted Wegleitner, president and CEO of HealthPartners' Lakeview Health System in Stillwater.

Tracy Singleton, owner of the 22-year-old Birchwood Cafe, said she was "thrilled" to hear about Urban Organics.

"It's been hard to find fish that fits our parameters for sustainable ingredients" that are free of antibiotic, mercury, PCB and overfishing concerns, she said.

Haider and co-founder Ames said their method uses 2 percent of the water usually consumed by traditional agriculture.

"Our local market will get the benefit of our fish and greens, but there will also be a worldwide benefit as we continue to learn from this model and apply its lessons to other locations in the future," Haider said.

Dee DePass • 612-673-7725

Urban Farming in Singapore Has Moved Into A New, High-Tech Phase

In community gardens found in housing estates, schools and even offices, urban farms are taking root in Singapore. Such farms are not ornamental gardens. Instead, gardeners plant vegetables and fruit such as cabbage, basil and lime to eat.

Urban Farming in Singapore Has Moved Into A New, High-Tech Phase

As urban farming becomes more widespread, enthusiasts are coming up with new methods to grow edibles

JUN 3, 2017, 5:00 AM SGT

In community gardens found in housing estates, schools and even offices, urban farms are taking root in Singapore.

Such farms are not ornamental gardens. Instead, gardeners plant vegetables and fruit such as cabbage, basil and lime to eat.

Urban farms have always been popular with gardeners in Singapore, especially those who volunteer at neighbourhood community gardens.

The National Parks Board's popular Community In Bloom programme - a nationwide gardening initiative which started in 2005 - has more than 1,000 community gardening groups today. About 80 per cent of the groups in Housing Board estates grow edibles in their community gardens.

But urban farming has become more high-tech and, well, urban.

Urban farmers have started growing food in restaurants and taken over unused rooftop carpark spaces to set up garden plots.

Three urban farms stand out for their ingenuity.

The first is by a group of engineering students who have combined two aquaponics methods to get a larger harvest with more variety.

The second is by a businessman who used to sell raw materials for pesticides. He has invented a "growing tower" that does away with chemicals.

The last and most photogenic is by architecture practice Woha, which started an edible garden on the rooftop of its Hongkong Street shophouse office.

The gardening enthusiasts in the office have designed a photogenic farm, filled with lush greenery and decorated with stylish outdoor furniture.

Staff harvest vegetables and herbs such as kangkong and lemongrass to put in their salads or cook for office parties.

The Straits Times checks out these three urban farms.

PRETTY, FUNCTIONAL OFFICE ROOFTOP

Architecture practice Woha has a 2,100 sq ft organic urban farm on its rooftop, which is tended to by the firm’s gardening club, headed by Mr Jonathan Choe. ST PHOTO: LIM SIN THAI

When it comes to starting an urban farm, creating a good-looking set-up isn't usually top on the to-do list.

But for Woha, a home-grown award-winning architecture practice known for working greenery into its buildings, such as Parkroyal on Pickering hotel, urban farms can be useful and pretty.

The firm used the rooftop of its Hongkong Street office shophouse as a test bed for a 2,100 sq ft organic urban farm with more than 100 species of edible plants, including kangkong, basil, pandan, dill and bittergourd, which are shared among the staff.

Other than providing food, it is also a scenic place for staff to relax and destress, even if they are not interested in gardening.

The project, which cost $50,000, was completed last month.

Two rows of aquaponics planter beds, brimming with edible greens, are housed in sustainably treated pine wood boxes. The heights of these boxes have been designed so that gardeners need not bend over or squat when tending to the plants.

Behind these planters is a metal frame that is fitted with more planter boxes placed at different heights.

Flowering vines such as passionfruit and vanilla twine and creep up the metal frame. Some have even extended themselves across the wires overhead.

When more of these vines grow to maturity, they will create a canopy that will provide some shade in the open-air area.

Other highlights include an aquaponics system, which consists of a tilapia fish pond and a sloped planter bed. The system has water running through custom-made stainless steel water spouts. Across a short landing of wooden steps is a serene pond, centred by a tall kaffir lime tree.

Outdoor tables and chairs have been put in so that Woha's staff can pop up to the farm for a break.

Members of the firm's gardening club gather every Friday and spend about an hour tending to the plants.

A gardening workstation for potting and propagation and a large tank that collects rainwater to water the plants are kept out of sight at the back of this urban farm showpiece. The office also makes its own compost from food scraps.

Architectural designer Jonathan Choe, 28, who is the head of the gardening club, says they are looking to rear chickens there too.

He was part of the core team, including Woha founders Wong Mun Summ and Richard Hassell, that designed and built the farm.

He says: "We're not a commercial farm, where we grow vegetables just for food. It's also a beautiful sky garden, which the staff can enjoy."

USING WASTE TO GROW FOOD

Associate professor Lee Kim Seng (front) and the students behind the project (from left) – Mr Lim Zi Xiang, 35, Mr Kibria Shah, 31, and Ms Boo Jia Yan, 23. PHOTO: DIOS VINCOY JR FOR THE STRAITS TIMES

In a corner of Eng Kong Cheng Soon community garden in Lorong Kismis stands an industrial-looking set-up that contrasts sharply with the thriving greens in the soil.

A fish tank, filled with black African tilapia, is connected to long grey pipes which have cut-out holes in them. The seedlings of leafy vegetables are planted in net pots placed in these holes. Their roots dangle in the pipes and absorb the nutrient-rich water flowing through.

Above the fish tank is a container filled with clay pellets. Edible plants grow here, watered by the fish tank too.

The entire set-up is shaded by a plastic canopy that lets sunlight in, but keeps rain out.

This hybrid aquaponics system has yielded about 6kg of vegetables, such as butterhead lettuce, spring onion and Chinese cabbage, in the last two months.

The bountiful harvest is the result of a final-year project by three engineering students at the National University of Singapore (NUS).

The students built the system from scraps they found in their school's workshops. It took a few months to design and construct the 251 sq ft system, which is about the size of a room in an HDB flat.

Aquaponics combines aquaculture, the raising of edible fish, with hydroponics, growing vegetables without soil.

There are three ways to set up an aquaponics system, though common elements include having a fish tank and a soil-free plant bed. Both fish and plants are cultivated in one system. The fish waste provides organic fertiliser for the plants and the plants filter the water for the fish.

The students kept these basic features and combined two aquaponics methods - media-filled beds and Nutrient Film Technique - into one system, allowing them to grow a greater variety of plants.

The media-filled containers are good for growing plants such as tomato, brinjal and chilli. These have long stems that are kept sturdy by the clay pellets.

Leafy vegetables, which have shorter stems and long roots, are better suited for the Nutrient Film Technique - grown in net pots.

The fish can also be eaten once they are fully grown. The set-up is fully automated so they have to check in only once a week.

The students decided to work out of the community garden as they would be among seasoned gardeners. Ms Boo Jia Yan, 23, says: "There was a lot of experimentation and we had little knowledge of farming. Here, we were able to get advice about what could be improved."

They have plans to fit in high-tech features such as solar panels, which can generate electricity to power the system and install a device that allows for remote monitoring.

The set-up has attracted interest from two home owners.

Associate professor Lee Kim Seng of NUS' mechanical engineering department, who supervised the project, hopes more people will take on urban farming. "It's a very easy set-up. Why not utilise the waste to grow something good?"

VEGGIES FROM ON HIGH

Organic farming company Citiponics, run by Mr Teo Hwa Kok and Madam Jenny Toh (both above) operates 164 “growing towers” covered in leafy green vegetables, on a carpark rooftop. ST PHOTO: JAMIE KOH

At a multi-storey carpark rooftop in Kang Ching Road, 164 "growing towers" covered in leafy green vegetables rise to the sky.

Standing at 1.8m tall and lined up next to one another, these gardening systems are the result of years of research and development by Mr Teo Hwa Kok, 55, chairman of organic farming company Citiponics.

They have been used to produce about 25 types of vegetables and herbs, such as butterhead lettuce, spinach, dill, kailan, sweet basil and mizuna, a member of the mustard family.

At the base of each tower is a tank filled with water and nutrients. The mixture is pumped up to the top of each tower and flows down by gravity through a series of seven pipes arranged in a zig-zag manner.

The pipes have holes cut into them, creating pockets. Tiny clay pebbles, which have been cut to a specific size, fill these pockets. Seeds are placed among the pebbles, which is the growing medium for the plants.

As the water is constantly in motion, mosquitoes cannot breed. Also, no pesticides are used.

This is an improvement over some traditional hydroponics systems, which use water as a growing medium. This means that water can be stagnant in some parts.

Mr Teo says his version is lighter as it uses less water and can be built to any height.

The produce, which is harvested by volunteers from a nearby Residents' Committee centre, is given free to needy residents in Taman Jurong.

Mr Teo has been involved in the farming business for a long time, though he was not always a farmer. The Malaysian moved to Singapore in 1987 to work for a pesticide company. He quit in 1993 and set up his own venture selling raw materials used to make pesticides.

But as he read more reports about pesticides being misused and affecting food safety, he started to look into organic farming.

"It gave me an uncomfortable feeling so I decided to look into other ways to grow plants."

In 2001, he set up a 3ha organic farm in Malaysia, growing vegetables in soil. It did not take off and he gave it up about two years later.

He calls it a "very expensive experience" as consumers were not ready to pay high prices for pesticide-free vegetables then.

About seven years ago, he decided to try organic farming again and came up with the prototype for the growing towers.

He operates Citiponics with the help of Madam Jenny Toh, 55, who used to work in his pesticides business.

Citiponics has taken its growing towers to China and Malaysia.

On average, each growing tower costs about $4,800 and Mr Teo says it can last 20 years. A harvest from one tower can weigh between 5 and 10kg, depending on what vegetable is grown.

For his next green project, he wants to look into making pesticide-free feed for chicken and fish.

"Maybe one day, we can reduce the use of pesticides. Until then, we have to keep pushing ourselves to improve the safety of our food."

Nabeela Lakhani: I’m Taking Action To Create Solutions

Nabeela Lakhani: I’m Taking Action To Create Solutions

Square Roots, a new urban farming accelerator located in Brooklyn, New York, is producing as much food as a 20-acre farm without using any soil. The-five month-old company puts hydroponic growing systems in old, repurposed shipping containers. Each container is capable of producing roughly two acres of food, without the use of pesticides or GMOs. Each container only uses eight gallons of water per day. That’s less than your morning shower.

Nabeela Lakhani is a food entrepreneur at Square Roots specializing in Tuscan Kale and Rainbow Chard. She was one of 10 farmers chosen out of an application pool of 500 for Square Root’s inaugural launch. Food Tank had a chance to speak with Nabeela about her background, current work, and thoughts on approaching solutions in the food system.

Nabeela with her kale at Square Roots. Credit: Nabeela Lakhani

Food Tank (FT): How did you get involved with Square Roots?

Nabeela Lakhani (NL): I’ve always been interested in food and my passion and my purpose has always been around the food industry and the food system. I went to school for public health and nutrition thinking that was going to be the way I made whatever impact I wanted in the food industry, but then as I was going through school I started to realize nutrition was highly clinical and medical. We were looking at treating diseases with medical and nutrition therapy, diseases that could be prevented if we nourished our populations better. We should have been looking at how our food system was prioritizing certain crops over others and how food is distributed in our country. What would happen if we looked at food before it gets to the body, food before it gets to the community? When I discovered that food production and food distribution was what I wanted to pursue I just kind of started telling everyone in my networks that that was what I was now interested in. I used to just tell people, ‘I want to be a farmer I want to be a farmer!’ I was having a hard time getting my foot in the door in urban agriculture because I had no experience; my experience was all health and nutrition related. But I did have a lot of start-up experience so I was really excited about Square Roots. It put the startup experience that I had with the agriculture experience I wanted.

FT: Can you explain how Square Roots works?

NL: We use a standard shipping container, just a regular truck, and it is repurposed to accommodate a hydroponic system. You have these towers lined up inside and the towers are essentially the farm field where everything grows. You control all the elements that a plant needs to grow and you can optimize those elements for that plant’s growing experience, which is then going to reflect heightened taste, heightened freshness, heightened nutritional content. You can even control the nutrient levels that go into the water. And then you’re also controlling the temperature, the climate, the humidity, the CO2 level; you can literally recreate an environment to grow something. For example, if you visited Italy one summer in 2006 and you the best-tasting basil you’ve ever in your life, you could look up the climate and the weather patterns for that time that you were there and recreate that climate inside this container. Another really cool thing is we have a really low water usage, so we use 70 percent less water than conventional farming. This whole container, if you really pack it in, can grow almost two acres worth of food in just that standard shipping container space. It runs on eight gallons of water a day, which is less than your shower.

FT: Are you the first farmers to grow food in a shipping container?

NL: No, actually the containers we use are bought by manufactured by a company called Freight Farms. Their business is to manufacture these containers and then they sell them to customers like us. They have these containers in multiple countries across the world already.

FT: Who is your customer base?

NL: Right now, our customers are mostly adults, although one of my customers is a bunch of NYU students. One of the channels that a lot of farmers are exploring now is farm to local membership, which is basically a weekly delivery to a local community hub. We found that offices are really good for this, because there’s already a community feeling around them. You’re already in a team and you already know the people, so it’s easier to mobilize people and get bigger hubs out of office spaces. That’s one channel that’s really taking off and we’re delivering to places like Adobe and the New York Times building. It’s picking up pretty fast.

Nabeela surveying a wall of produce. Credit: Nabeela Lakhani.

FT: What are you guys growing right now?

NL: Mostly just leafy greens. With hydroponics it is possible to grow fruits and vegetables and one of our farmers is actually experimenting with carrots and radishes and things like that, but given the way the Square Roots program is set up, which is we get this container for one year and we get to build a business out of it, it makes sense to grow whatever makes the most economic sense. If leafy greens take four weeks to grow and yield really high then I’m going to grow that.

FT: What plans does Square Roots have for the future?

NL: Right now we’re based in New York City, but the goal is to get to 20 cities by 2020. Square Roots’ mission is to create an army of young food entrepreneurs who are equipped with experience using technology and building a viable business model. Before I started at Square Roots I felt like I never knew what kind of step I could take or what kind of impact I could have. Revolutionizing the food industry seems so colossal. But now it’s like, ‘No, I’m actually taking action and I can create my own solutions in the future.’ I now have the experience of building a sustainable business and running a business responsibly and impact fully.

Kids Who Grow Vegetables, Eat Vegetables

Kids who grow vegetables are more likely to want to eat them. A recent report by Cornell University found that salad consumption increased by 400% when kids had been involved in growing the ingredients.

Kids Who Grow Vegetables, Eat Vegetables

May 31, 2017 | Posted by Nathan Littlewood | Uncategorized | 0 comments

Kids who grow vegetables are more likely to want to eat them. A recent report by Cornell University found that salad consumption increased by 400% when kids had been involved in growing the ingredients. But here’s the challenge; who has the time to go shopping for pots, soil, gloves, buckets, seeds and a watering can only to have the kids lose interest a week later and have the plants die. Not to mention the inevitable mess involved. No thanks!

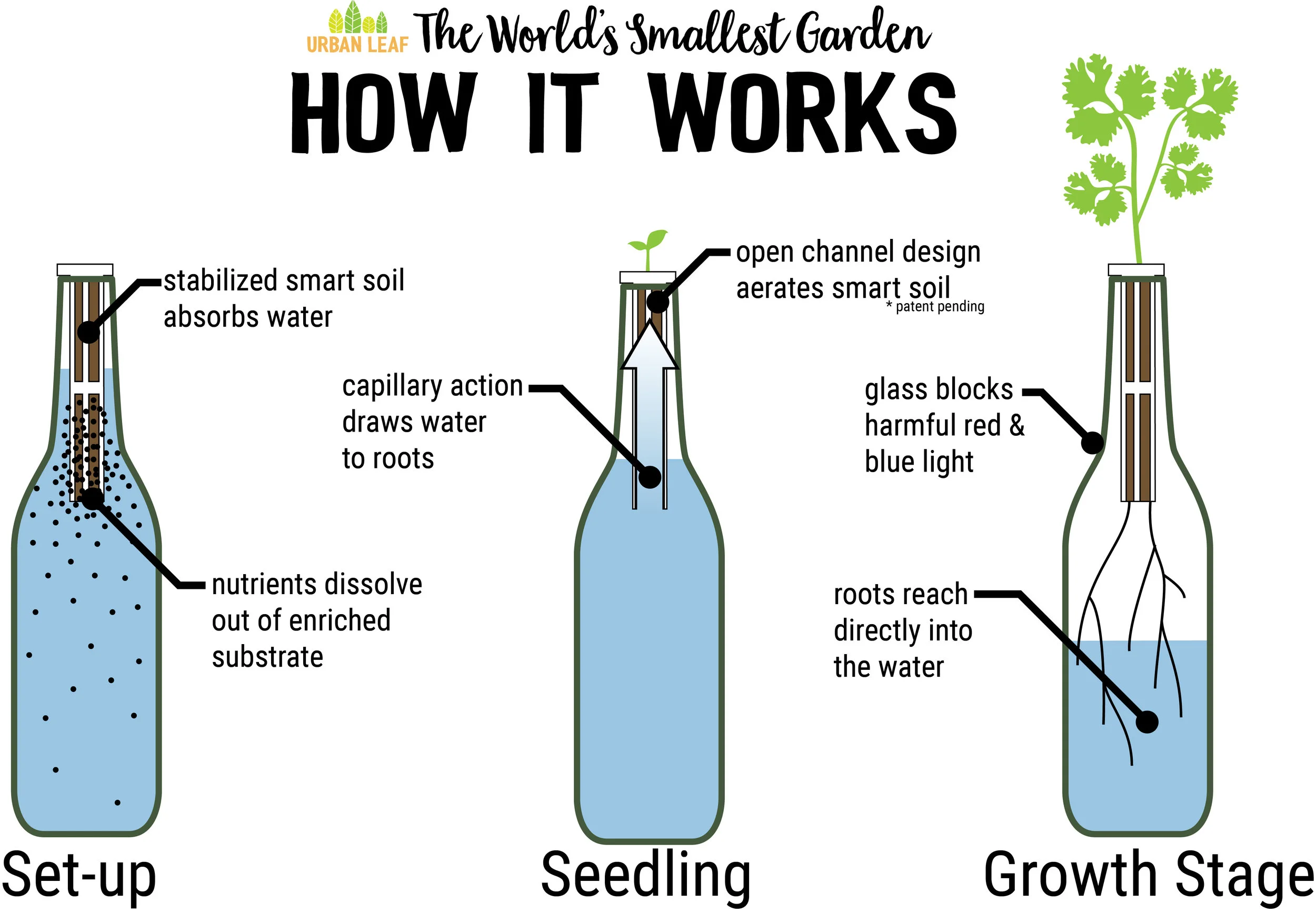

Urban Leaf may have just the answer you need. The World’s Smallest Garden turns a bottle into a self-watering garden in seconds. The device allows plants to water themselves for up to a month at a time using the water from the bottle, and when the water level gets low — top up is easy.

The product relies on capillary action to lift water up to the seed. As the seedling sprouts it sends roots down into the bottle. The nice thing about growing in a bottle is that kids can observe the entire process — roots and all! One of the many benefits of growing your own food indoors is that you know exactly where it came from and how it was produced — with no nasty pesticides or sprays.

The process of decorating the bottle can even be made into a cool craft project. We’ve seen users decorating their bottles with paint, ribbons, buttons and much more. If that sounds a bit much, there’s a bunch of people on Etsy who sell decorated bottles that are ready to go!

So while the kids are busy learning about recycling, repurposing, biology, plants, nutrition and health all mom and dad have to worry about is ensuring there’s an adequate supply of empty bottles around the house. How hard can that be?

Urban Leaf is currently launching the World’s Smallest Garden on a crowd funding site called Kickstarter. By making a pledge toward the campaign you’d be helping get the project off the ground.

About Nathan Littlewood

Nate Littlewood is the Co-Founder and CEO of Urban Leaf

The Non-Profit Urban Roots Has Broken Ground For Its First Planting This Spring

There are big plans for that little bit of turned-over urban ground. For the people behind London’s first not-for-profit organic urban farm, it’s a big step back to the community’s agrarian roots and using empty spaces to produce food.

The Non-Profit Urban Roots Has Broken Ground For Its First Planting This Spring

By Jane Sims, The London Free Press

Tuesday, May 30, 2017 | 7:40:25 EDT AM

Cars and trucks speed down the hill along Highbury Avenue, past the transmission towers and a former horse pasture just north of the Thames River.

It would be simple enough to miss seeing the newly tilled patch of earth in the middle of an open green field that used to be horse pasture.

There are big plans for that little bit of turned-over urban ground. For the people behind London’s first not-for-profit organic urban farm, it’s a big step back to the community’s agrarian roots and using empty spaces to produce food.

Urban Roots, an organization slowly, steadily growing in momentum since its incorporation six months ago, has leased one hectare of land with the goal of a first planting and harvest this year.

This is a much different project than local community gardens. The goal is a sustainable, working farm that would supply produce to charities and neighbourhoods that have difficulty finding good quality fresh produce.

And because it is different, it has challenged municipal law-makers already working on an urban agricultural strategy.

“London, right now is focusing on its urban agricultural policy so they’re working to establish that, but it’s not in place yet,” said Heather Bracken, one of the group’s founding board members.

“So, we’ve had lots of conversations with the city. They’ve been great with taking our phone calls and with helping to guide us, but it’s still kind of an unknown.”

The city, she said, “has never encountered a project like this.” The policy is supposed to be ready by summer’s end.

One of the hurdles, for example, is the need for soil testing, not something that is necessary if you want to put a few tomato plants in your backyard.

“We’re the first of our kind. It’s a unique project for this area so it’s hard for all involved, the city and us, to really know the best way forward and to make sure we have to do it properly,” Bracken said.

But there are inspirations for their plan.

The group has made a couple of visits to the successful urban farms in the blighted areas of Detroit, part of the Michigan Urban Farming Initiative (MIUFI), some that strictly donate produce to the needy and other for-profit enterprises.

Graham Bracken, another founder of the London project and Heather’s husband, said they want to take the best of those models and “mash them all together.”

“There’s a lot of enthusiasm we’ve been picking up from people who have green thumbs and are involved in agriculture in one way or another, be it the food forests or the community gardens,” he said.

“A lot of people have been asking us, ‘Why did it take so long for it to happen?’ From that we get the sense that London is ready.”

Also needed was some added agricultural expertise. Of the four founding board members, only one, Richie Bloomfield, an accounting instructor at the Ivey School of Business, grew up on an organic farm. Social services veteran Jeremy Horrell, founder of the Forest City family project, “has an impressive backyard garden.”

Heather Bracken is a criminal defence lawyer. And Graham Bracken is an environmental philosophy writer.

But all of them agree there are food deserts in the city that could produce food.

The goal for this season is to get seeds in the ground, build a hoop-house — a portable greenhouse structure — and have a harvest to show “what we can do within the boundaries of the city,” Heather Bracken said.

Then, they want to expand the project to more locations to include training in how to grow and harvest your own food, plus cooking and canning sessions.

Urban Roots already has established relationships with Youth Opportunities Unlimited and Goodwill Industries.

The group has applied for a series of grants, but also has a GoFundMe campaign at www.gofundme.com/urban-roots-london, with the hopes of raising $7,000. So far about $1,700 has been raised.

jsims@postmedia.com

Downtown Victoria Condo Project Offers ‘New Ethos’ In Urban Living

The Wade features an urban rooftop garden space and what is believed to be the largest centre courtyard for condos in Victoria. Courtesy ten-fold projects

Downtown Victoria Condo Project Offers ‘New Ethos’ In Urban Living

The Wade is being constructed on site of former medical building at Cook and Johnson streets

- Thu Jun 1st, 2017 11:30am

- BUSINESSLOCAL BUSINESS

Tim Collins/News staff

The Wade is a low-rise, four-storey development in the works for the corner of Cook and Johnson streets, and according to the developers, it’s more than just another condo development.

According to developer Max Tomaszewski, it’s the expression of an ethos based upon environmental sustainability and a higher quality of life for its residents.

“If you’re going to spend 14 hours a day in a place, it should be a place that does more than provide shelter. You want a home that improves your health and quality of life,” he said.

Tomaszewski and his partner, David Price of ten-fold projects, have been building to Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standards for 15 years, but The Wade’s design and features are particularly rewarding.

The 102-unit, two-building development reflects the partners’ belief that real estate construction is moving toward a wellness orientation by incorporating a series of features not ordinarily found in a project of this kind, Tomaszewski said.

For example, each unit is assigned not only the standard parking spot and storage locker, but a four-by-eight-foot rooftop garden plot as part of an urban farm concept, complete with an apiary to aid in pollination.

The municipal water supply will receive additional filtration and the centre courtyard, billed as the largest of any condo in Victoria, will be home to an orchard.

The building is designed to minimize the background noise of the city. Another significant aspect of The Wade is the price point at which they’ve entered Victoria’s condo market. Units are priced between $260,000 and $300,000, a cost made possible, said Tomaszeweski, by savings realized through utilizing the existing “bones” of the medical arts building, upon whose footprint The Wade will be built.

The development is expected to be ready for occupancy by Christmas 2018.

More information is available at thewade.ca.

editor@vicnews.com

Des Moines Power Brokers Want to Build Massive Greenhouses Downtown

Des Moines Power Brokers Want to Build Massive Greenhouses Downtown

Joel Aschbrenner , jaschbrenn@dmreg.com

Published 5:40 p.m. CT May 25, 2017 | Updated 10:59 a.m. CT May 26, 2017

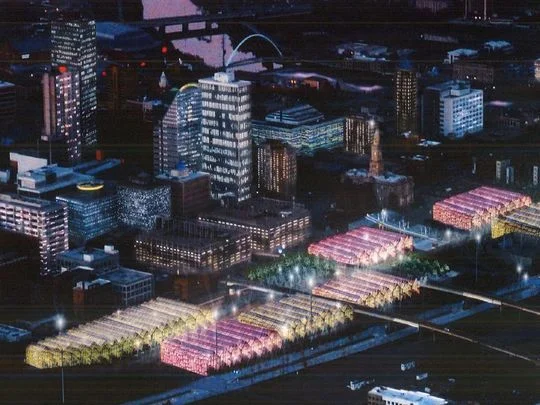

A group of business leaders want to build a string of greenhouses on the south side of downtown. They call it the Des Moines Agricultural Corridor.

(Photo: Special to The Register)

New York architect Mario Gandelsonas helped reshape Des Moines when he laid out his vision for the city nearly 30 years ago. That vision ultimately led to the development of the Western Gateway, construction of the Principal Riverwalk and resurrection of the East Village.

Now, Gandelsonas is back in town promoting his latest idea, one he says is equally ambitious.

A group led by Gandelsonas and local venture capitalist Jim Cownie wants to build a string of massive greenhouses and vertical farms along the railroad tracks on the south side of downtown. They’re calling it the Des Moines Agricultural Corridor. If fully realized, the project would span the length of downtown.

“The dream is all the way from Meredith Corp. to the state Capitol,” Cownie said.

Cownie hopes to get buy-in from local players like Hy-Vee, DuPont Pioneer, MidAmerican Energy and Iowa State University. The urban farms could feed the desire for locally grown food, provide produce for area farmers markets, grocery stores and restaurants, and offer research space for Iowa State students and agriculture companies, he said.

Gandelsonas sees the project as a cultural symbol. It would provide the urban core with a link to the state’s farming roots and showcase Des Moines as a hub for innovative agriculture, he said.

“The idea is not just to build a greenhouse,” he said. “The idea goes deeper than that. It relates to identity, to health, to education. So it is really a grand idea.”

Far-fetched? Maybe.

At this point, the Des Moines Agricultural Corridor is little more than an idea. No land has been acquired. No money has been raised. And it’s unclear who would own and operate the indoor farms.

Cownie thinks it could take 20 years and tens of millions of dollars to complete.

But after working behind the scenes for a few years, Cownie and Gandelsonas are beginning their campaign to drum up support.

They've pitched it to local companies. Officials from MidAmerican and Hy-Vee told The Register they're listening but they've made no commitments.

Cownie and Gandelsonas held meetings Wednesday and Thursday with City Council members and other power brokers.

Buy Photo

Mario Gandelsonas shows plans for the Des Moines Agricultural Corridor, a string of massive greenhouses on the south side of downtown Des Moines. Gandelsonas, a New York architect, and a group of local business leaders are trying to drum up support for the idea. (Photo: Joel Aschbrenner/The Register)

In Cownie’s penthouse office overlooking the East Village on Wednesday, Gandelsonas explained to Councilwoman Christine Hensley how the greenhouses, lit with bright colors, would create a “river of light” visible to people flying into the city.

Hensley, Des Moines’ longest serving city council member, whose ward includes downtown, said she would be apt to support the project if the greenhouses operated as a for-profit entity that pays property taxes.

“The city has demonstrated that if we get the right people behind projects such as this, there is no question we will get it done,” she said.

The goal is to start with one half-acre greenhouse. Those involved said they don't know the exact cost. Ballpark: $5 million.

Cownie thinks the best location is a piece of city-owned land near 12th and Mulberry streets, on the southwest side of downtown.

A group of local business leaders is promoting the idea of building a string of massive greenhouses along they railroad tracks on the south side of downtown Des Moines. The idea, called the Des Moines Agricultural Corridor, is the brainchild of Mario Gandelsonas, the New York architect who created the vision for several Des Moines redevelopment projects including the Western Gateway and the Principal Riverwalk. (Photo: Special to The Register)

The first step, Cownie said, would be to come to an understanding with city leaders. He wants the city to challenge him to raise the money for the first greenhouse, and if he does the city, in return, would offer the land for free.

“We need to demonstrate to the city that it would be good public policy to make available the site to start this process,” he said.

If the first greenhouse is a successful model, it could be replicated down the railroad corridor on undeveloped sites.

Cownie hesitated to put a timeframe on the project — he’s been burned by such promises in the past — but others involved in the proposal said they want to harvest crops within five years.

More: 13 of downtown Des Moines' craziest ideas – good and bad

The project will depend on acquiring land. Most of the property along the rail line is privately owned.

That includes land where Cownie has a stake. He recently partnered with the city to offer five square blocks on the east bank of the Des Moines River as a site for a new federal courthouse. It is one of four proposed courthouse locations and includes several blocks for private development.

Gandelsonas said the greenhouses would make nearby properties more valuable by providing a buffer between the rail line. His plan also calls for a pedestrian corridor along the greenhouses with a recreational trail and landscaping.

The idea is not entirely new. Gandelsonas pitched a farming corridor nearly 10 years ago during a city planning process. The original idea was an avenue of outdoor crops stretching across downtown to showcase Iowa agriculture.

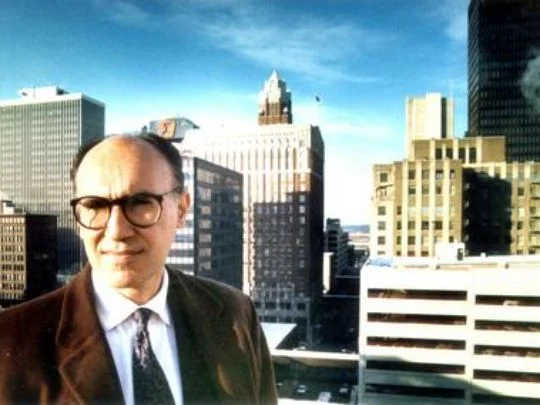

Mario Gandelsonas in Des Moines in 1989. A New York architect, Gandelsonas helped create a vision for the city that led to the create of the Western Gateway and the Principal Riverwalk. (Photo: Register file photo)

Among movers and shakers in Des Moines, Gandelsonas has a fervent following. The Argentina-born, Paris-educated architect came to city in the late 1980s and helped craft the Des Moines Vision Plan, a blueprint for revitalizing the city.

Over the years, he has proposed some of the city’s most audacious projects.

One idea called for massive apartment complexes built in the shape of letters on the north side of downtown. He also dreamed of carving back the Des Moines River banks so City Hall and the World Food Prize would stick out on peninsulas.

But Gandelsonas is also credited with some of the city's biggest successes. He had the vision to demolish roughly 10 blocks of aging buildings and car dealerships on the west side of downtown to make room for a park. The project drew scoffs from skeptics and backlash from preservation advocates, but the development of the Western Gateway ultimately led to the construction of the Pappajohn Sculpture Park and hundreds of millions of dollars of office development from Nationwide, Wellmark and Kum & Go.

Asked if the Des Moines Agricultural Corridor is even more ambitious, Gandelsonas said: “It feels as impossible as the idea for Gateway Park... It is quite an undertaking, but I view it as important to accomplish this.”

Why now?

Jim Cownie (Photo: Register file photo)

Cownie, 72, and Gandelsonas, 78, say they’re getting older so it’s now or never.

And downtown has the momentum to support it, Gandelsonas said.

It also helps that a compatible idea is gaining steam. Iowa State officials and local business leaders are working on a proposal to create a year-round, indoor market inside Kaleidoscope at the Hub, an aging downtown shopping center.

Iowa State’s Courtney Long, who is overseeing the idea, said the greenhouses could provide produce for the indoor market and collaborate in other ways. Long has been meeting with the greenhouse backers for about a year to discuss the project.

“I think it’s interesting and unique," she said. "There is nothing like it."

To lead the greenhouse effort, Cownie is considering Bill Menner, a consultant who recently served as a state director for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

A group of local business leaders is promoting the idea of building a string of massive greenhouses along they railroad tracks on the south side of downtown Des Moines. The idea, called the Des Moines Agricultural Corridor, is the brainchild of Mario Gandelsonas, the New York architect who created the vision for several Des Moines redevelopment projects including the Western Gateway and the Principal Riverwalk. (Photo: Special to The Register)

Menner said there could be USDA grants or government loans available for the Des Moines Agricultural Corridor.

And there are good models to learn from, he said. A group in Cleveland recently opened a 3.25-acre urban greenhouse, though it sits in a more industrial area, not in the heart of downtown.

Menner sees the greenhouse development as a way to bridge the urban-rural divide that has grown amid water lawsuits, bitter politics and rural population loss.

“By placing urban agriculture in the center of a metropolitan area, you’re actually building a bridge to the producers and the folks who make a living (in agriculture) while at the same time creating access to locally grown foods,” he said.

Fresh Veggies Grown Close to Home, Without Pesticides — And Without Dirt

Fresh Veggies Grown Close to Home, Without Pesticides — And Without Dirt

Civic Farms touts having “pioneered the vertical farming industry.” The company says its proprietary growing systems, licensed patented technologies, and optimized processes for cultivation and harvesting processes maximize the efficiency and efficacy of growing indoors.

TUCSON (CN) – An ambitious project of emerging agricultural technologies that produce food without soil is taking shape at Biosphere 2, the University of Arizona’s research complex north of Tucson.

Civic Farms, an Austin-based company, this summer will start building a vertical farm in one of two 20,000-square-foot domes – or “lungs” – that regulated pressure inside a sealed glass structure during experiments to study survivability in the 1990s.

The company will invest $1 million to renovate the Biosphere’s west lung, unused for years, and outfit the space with stacked layers to grow soil-free plants in nutrient-laden circulating water under artificial lights.

At full capacity, the vertical farm will produce 225,000 to 300,000 lbs. a year of leafy greens and herbs such as lettuce, kale, arugula and basil, said Paul Hardej, CEO and co-founder of Civic Farms.

“Biosphere itself is a fantastic facility and food production is a big part of what it was originally intended to do,” he said.

As the world population continues to rise, particularly in cities, along with consumer interest in the origins of food, vertical farming is gaining traction as a commercially viable way to increase crop production in a fully controlled indoor environment.

“People want know what they eat and what’s in their food and how healthy and good it is for them,” Hardej said. “Growing food in city centers or close to city centers where people live makes perfect sense.”

Under an agreement with the university, Civic Farms will grow crops in half the space it will lease for $15,000 annually. Research and scientific education will comprise the other half and the company will contribute $250,000 over five years for those efforts.

“We envision that a portion of the lung will be open and accessible to the public so people can come in see how and what it is to have a vertical farm,” said John Adams, the Biosphere’s deputy director.

Civic Farms touts having “pioneered the vertical farming industry.” The company says its proprietary growing systems, licensed patented technologies, and optimized processes for cultivation and harvesting processes maximize the efficiency and efficacy of growing indoors.

The Biosphere already draws nearly 100,000 annual visitors to expansive grounds originally intended to showcase a self-sustaining replica of Earth, or Biosphere 1.

Set on a 40-acre campus against the backdrop of the rugged Santa Catalina Mountains, the Biosphere’s 91-foot steel-glass structure serves as a global ecology laboratory enclosing an ocean, mangrove swamp, rain forest, savanna and coastal desert.

In the early 1990s, a crew of scientists was locked inside the sealed structure in privately funded scientific experiments designed to explore survivability with an eye toward space colonization. Problems with the experiments and management disputes eventually halted the highly public venture.

The University of Arizona took over the property, about 30 miles north of Tucson in the town of Oracle, in 2011.

The Biosphere’s Adams views the planned vertical farm as a good fit for research initiatives.

“For the next 10 years, Biosphere’s focus is very much on food, energy, water – and the nexus,” he said.

Civic Farms’ Hardej said the university’s myriad resources were strong incentives for his company’s new enterprise in Arizona. A big plus are the concepts being developed at the university’s Controlled Environment Agriculture Center on North Campbell Avenue, where scientist Murat Kacira grows leafy crops indoors under LED lights.

“There’s so much interest in this technology platform because it provides the capability to grow food with consistency,” Kacira, a professor of agricultural-biosystems engineering, said of vertical farm systems.

Inside the lab where lettuce and basil grow in hydroponic beds under the glow of blue and red LED lights, Kacira and his students monitor the conditions in which seedlings mature.

“The environment is fully controlled in terms of providing temperatures needed, or humidity needed, carbon dioxide or the light intensity or the quality needed for the plant production,” Kacira said.

Not being at the mercy of Mother Nature makes vertical farms more productive than conventional farms, as well as more efficient at using natural resources such as water, he said. “You’re circulating it inside the environment, so the efficiency is much higher.”

Still, Kacira said, the technology is energy-intensive, given the use of artificial lights and the need to condition the environment. And although large-scale commercial operations are relatively rare, he said, advances in scientific research and the high-tech industry are making it a feasible platform to help supplement food production in cities.

“Our food transportation is coming from long distances, and by the time it gets to the consumer, especially leafy crops, the freshness may not be there,” Kacira said.

Vertical farms are a relatively new concept that hold great potential, Hardej said it. With a projected global population of 9.5 billion, mostly urban, by 2050, he views vertical farms as an increasingly important part of the world’s food system.

His own vertical farm aims to provide the Tucson and Phoenix markets with high-quality produce grown sustainably and without pesticides, Hardej said.

In time, he plans to incorporate more energy-efficient solutions into his operation.

“For commercial scale, those technologies still need to be perfected,” he said.

His company plans to begin growing the leafy greens by year’s end.

Seeds Of Change: Mini Gardens Help Drive The Growth Of Food At Home

Seeds Of Change: Mini Gardens Help Drive The Growth Of Food At Home

May 31, 2017 11:59 AM ET

KRISTEN HARTKE

Seedsheets are made of weed-blocking fabric, a thick layer of soil and dissolvable pods full of organic seeds.

Courtesy of Seedsheet

The short, but intense, growing season in Vermont might be a drawback for some, but for native son Cam MacKugler, it has turned out to be the key to developing his container garden kit startup, Seedsheet.

"Up here in Vermont," says MacKugler, "we don't have a lot of time to grow our food, so the goal is to get as much as you can as quickly as possible."

A house-sitting stint on a co-worker's farm in 2012 is what inspired MacKugler, an architect working in sustainable design in Middlebury, a small town in western Vermont. "I was paid with access to the backyard garden," he says, "and I was looking at the companion planting [an agricultural system for maximizing space and crop productivity] and how well it was designed — the arrangement of tomatoes and basil and zucchini. The idea for Seedsheet almost immediately came to me."

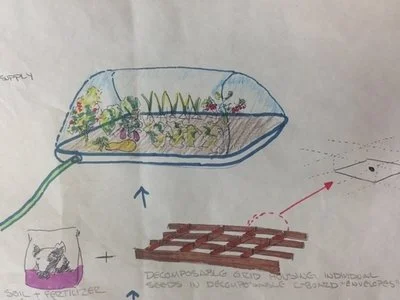

Sketching out the concept with crayons that were handy in the farmhouse, MacKugler was intrigued by the idea of foolproof gardening that would appeal to people living in cities with little or no outdoor space, but who still wanted the experience of harvesting their own crops.

When MacKugler first came up with the concept of Seedsheet, he sketched out the concept with crayons that were handy in the farmhouse where he was inspired by the garden.

Courtesy of Seedsheet

As MacKugler says, "We're kind of the Blue Apron of agriculture. It's not meal delivery, it's farm delivery."

A 2017 gardening industry survey produced by GardenResearch.com shows that 1 in 3 U.S. households now produces something edible at home, whether it's a pot of herbs on the windowsill or a raised-bed kitchen garden. In fact, consumer interest in growing food has translated to a $1 billion increase in sales in just five years, surpassing sales for flower gardening.

It's that all-important 18- to 34-year-old demographic — millennials — who are driving much of that growth, says Michelle Simakis, editor of Garden Center Magazine.

"Some millennials did not grow up gardening with their parents, so they aren't necessarily gardening as a hobby or to beautify their homes like previous generations did," says Simakis. "They are planting vegetables and fruit because they want to know where their food comes from and are interested in cooking with produce that's better than what they can find in stores."

As a millennial himself, MacKugler's instinct for the Seedsheet concept is all about making that "Green Acres" dream come true, but within the confines of modern urban living. His instincts are proving correct: 100 percent of Seedsheet customers live in cities, from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco.

"Most people here in Vermont think we're crazy, but that's because they've been raised as gardeners and don't see the need for this kind of product," he says.

His original concept involved spacing different types of seeds within two layers of dissolvable film, which were placed on top of soil and then watered. MacKugler had it tested by friends and family, who liked the basic idea — except for the weeds that sprouted alongside the seedlings, making it difficult to know what needed to be plucked. A new design using a 12-inch circle of recyclable weed-blocking fabric dotted with four or eight dissolvable pods filled with organic seeds and a thin layer of soil solved the weed problem.

"Companies in the lawn and garden industry are aware they need to provide products that guarantee ease and success for first-time gardeners," says Paul Cohen, research director of gardenresearch.com. Noting that he'd seen MacKugler demonstrating his product on a recent episode of the budding-entrepreneur reality TV show Shark Tank, Cohen says, "I expect to see a lot more of these types of products in the future."

MacKugler is particularly mindful of making first-time gardeners feel successful. "Our main goal is to choose varieties that will grow really quickly. We're figuring out which plants can grow together and reach maturity around the same time so people can coordinate cooking meals around the harvest."

MacKugler and his team focus on fast-growing varietals like Glacier tomatoes, while Ruby Streaks mustard greens and Valentine's Day radishes can be ready to eat in about a month.

Seedsheets are recipe-focused. For example, the one for hot sauce includes seeds for cayenne peppers, red carrots, Napoli carrot and purple bunching onions.

Courtesy of Seedsheet

"You can grow a lot of food in a small amount of space," asserts MacKugler. "People will say, 'You can't grow tomatoes in a bucket,' but it's actually very easy."

Indeed, besides MacKugler's kits, Simakis notes there are already a variety of other options popping up in the small garden marketplace. Both IKEA and Miracle-Gro offer countertop units, while would-be gardeners with a little more space can opt for LED-powered, indoor hydroponic growing kits. But she also sees that the millennial interest in growing food may be tied to loftier goals.

"Making gardening easy is important, but I think more companies are starting to promote the importance of gardening to help the environment, and generally speaking, the millennial generation is drawn to causes," she says.

For MacKugler, his own interest in sustainable design and supporting the local community means sourcing organic seeds and relying on the expertise of an important segment of the nearby population: farmers.

Because Vermont's farmers are typically out of work during the winter and early spring until planting season starts, they are becoming the biggest asset for his young company, where everything from custom machinery to seed assembly procedures needs to be built from the ground up. And with up to 600 kits being made per hour, MacKugler says, "We're selling more kits now than we actually have people in our town."

Curating seeds specifically for recipes has also been an important focus for MacKugler, highlighting another millennial trend: home cooking. A recent survey by online grocer Peapod shows that millennials are now twice as likely to cook at home than baby boomers, but they are more in need of inspiration than older, more experienced cooks. The "Hot Sauce Seedsheet" is one recipe-based kit designed to feed that need, with four seed varieties that grow together in a standard 12-inch pot: the Ring-O-Fire Cayenne Pepper, Dragon Red Carrot, Napoli Carrot and Purple Bunching Onions. The kit comes with recipes for spicy carrot juice and, of course, hot sauce.

"Our goal is to cultivate an understanding of how gardening works," says MacKugler. "Everyone should be able to call themselves a gardener, no matter where they live."

Social Entrepreneurs Grow A 'Computer Garden' At Zahn Innovation Center

Social Entrepreneurs Grow A 'Computer Garden' At Zahn Innovation Center

CONTRIBUTOR - I cover for-profit social enterprises and impact investing

A "computer garden" for urban farming that grows food without soil or harmful chemicals. That's the mission of SyStem, a fledgling New York City startup founded by two engineering students at The City College of New York.

"Our mission is to grow food for people in the future," says Alex Babich, a junior electrical engineering major, who founded the company with Adrian Logan.

Wild bloom Photography

SyStem's radishes (Photo credit: Wildbloom Photography)

It's also the winner of this year's Zahn Social Impact Prize, awarded earlier this month. That's a business pitch competition run by the Zahn Innovation Center, a semester-long incubator for City College students and graduates.

The co-founders created what Babich calls a "food computer"--a three-foot-wide by two-foot-deep box with a computer in it, along with an automated controlled environment for growing plants hydroponically. Various sensors monitor such factors as the temperature, humidity, the CO2 in the atmosphere, and the water's pH level. If, say, the latter is too low, the system will pump up the pH solution. "For whatever plant you want, you put in a recipe--software programmed to take the plant through the whole life cycle successfully," he says.

Ultimately, the startup aims to address a looming crisis--as world population increases, there will be less land available on which to grow food for more people. At the same time, the effects of climate change are likely to make it harder to produce enough sustenance. "We're developing ways to bring food closer to where people live and grow it in a more efficient way," says Babich.

But to develop technology capable of providing food on a large scale, according to Babich, time is of the essence. "That's why it's so important to be working on this type of technology now," he says. The plan is to build a modular system that has a central computer. Thus, you could create a large system with many modular sections or, with just a few, build a much smaller one in, say, someone's home.

Recently, Logan and Babich grew their first crop--radishes, which took about eight days to pop. "They came out really well," says Babich. Next step: Over the summer, they plan to develop their hardware platform. Plus, they're working with a fellow Zahn startup City LABscape to build the hardware for that company. City LABscape, which recently won the Standard Chartered Women + Tech4NYC Prize, has developed a curriculum and prototype for hands-on indoor agriculture STEM education for middle and high school students, using small hydroponic-growing systems.

SyStem's founders met each other in a CCNY engineering class and discovered they worked together well. One day, after he learned about the Zahn Center, Babich told his friend that he was interested in doing "something with an app." Logan wasn't crazy about the idea. Then Babich told him, "I really think it would be cool if there were a skyscraper growing plants automatically." So they tossed around ideas, like, for example, a computer that could grow plants, and were accepted into the Zahn program. A semester -long incubator, it takes 24 teams through a boot camp that trains them in how to move from an idea to building a prototype and forming the beginnings of a business.

Then they applied for Zahn's summer-long, a full-time accelerator program, which accepts 10 startups and is aimed at launching their business. Each of those teams gets $10,000, so they can spend the summer working on their startups, instead of at a summer job.

London Fights Urban Agriculture’s Peskiest Pest: Red Tape

London Fights Urban Agriculture’s Peskiest Pest: Red Tape

Urban farms offer cities a multitude of benefits, but municipal bylaws have long hindered them. London councillors are hoping to change that with a new strategy

Published on May 25, 2017

Urban farms like this one in Toronto can provide city-dwellers with fresh produce and can create new jobs. (Karen Stintz/Creative Commons)

by Mary Baxter

They wanted to grow food in the city and supply small local processors and soup kitchens with fresh vegetables — but when four would-be urban farmers in London found an ideal stretch of unoccupied land in the east end, the city told them they couldn’t lease it.

“We were literally not allowed to bid on that land because we were not going to develop it into houses,” says Richie Bloomfield, co-owner of Urban Roots London, the farming outfit in need of farmland. “That was kind of shocking to us.”

Urban agriculture is gaining popularity fast, but for farmers just getting started, often the biggest challenge isn’t learning how to till soil or keep pests at bay — rather, it’s the tangle of municipal rules and bylaws that either don’t take farming into account or actively discourage it.

But a new and nearly finalized urban agriculture strategy in London should make things easier, proponents say. According to Leif Maitland, the local planner spearheading the strategy, it’ll land on councillors’ desks by the end of the summer.

Supporters tout the benefits of urban farming: It makes fresh produce available to city-dwellers who might otherwise have trouble finding it, and it creates jobs, too. It can even help the environment, creating habitat for pollinators and reducing the distance food has to be trucked.

London’s strategy may not be the first in Ontario, but its inclusion of processing, distribution, food waste management, and education — all under the umbrella of urban agriculture — is unique.

Some of the proposed ideas, like building community gardens and growing fruit trees on public property, already exist in the city. Others, like a proposed backyard chicken pilot, have a long way to go before implementation. There’s also talk of establishing more farmers markets; creating hubs for sharing tools, supplies, and information; and building school gardens and community kitchens.

“We really wanted this strategy to inspire action, and that’s what the city wanted too,” says Lauren Baker, a consultant on the project and a former policy specialist with the Toronto Food Policy Council, a subcommittee of the city’s health board.

One of the biggest challenges will be putting the strategy to work — which will require participation from the municipal government and the broader community. In London, Maitland says, it’s not clear who will take the leading role.

“Maybe we’ll be enabling community groups, maybe we’ll be partnering with them,” he says. “Maybe we just need to change our bylaws to be as accommodating as possible, and then get out of the way and let people do what they want to do.”

Maitland says he’s familiar with the difficulties Urban Roots ran into searching for land. The city does rent to large-scale farmers who grow, for example, soybeans and corn, which can thrive even in poor soil. But the land is designated for other purposes, such as residential or commercial development, so it’s unsuitable for organic farming ventures that need to invest in long-term soil improvements.

Cloud Controlled Mini-Farms | AUDIO Interview - Smallhold

Cloud Controlled Mini-Farms | AUDIO Interview - Smallhold

31 May 2017

Very soon, grocery stores will be cloud-controlled mini-farms with shelves of growing produce -- according to the co-founders of the Brooklyn startup Smallhold. Hear how their ideas for vertical farming could impact your home, your supermarket and even outer space.

Click Above for Audio

We farm for you by growing produce 3/4 of the way and then deliver it to miniature vertical farm units (the size of shelving units) at your place of business to be harvested onsite as fresh, local food.

Smallhold gives you a networked farm, complete with sensors, climate control mechanisms, and hydroponics. Our horticulturalists run the farm from afar, growing for you right up until you pick and serve your produce.

From Slaughterhouse To Vertical Farm: The Plant Is Innovating In Sustainability And The Circular Economy

From Slaughterhouse To Vertical Farm: The Plant Is Innovating In Sustainability And The Circular Economy

May 30, 2017 Chuck Sudo, Bisnow, Chicago

In 1906, Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle” depicted the harsh conditions workers toiled under inside the slaughterhouses of the Union Stock Yard and Packingtown. A century later, this area that gave Chicago its brawny identity as “hog butcher for the world” is now home to several new food businesses focusing on sustainability, and The Plant in Back of the Yards is its epicenter.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow - The Plant, a vertical farm in Back of the Yards, was once a slaughterhouse.

This 94K SF former slaughterhouse was abandoned and slated for demolition when John Edel — through his company Bubbly Dynamics — bought it in 2010 and slowly repurposed the building into a vertical farm and food production business committed to a "circular economy," a closed loop of recycling and material reuse. Today, the Plant is home to several businesses where the waste stream from one business is repurposed for use by another business elsewhere in the building.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow

Whiner Beer Co. brews its beer at The Plant and opened a taproom whose bar, tables and chairs were made from reclaimed wood.

The Plant’s tenants are a who’s who of local food producers. Pleasant House Bakery is a popular company that bakes breads, desserts and Yorkshire-style meat pies that are sold wholesale at farmers markets and at Pleasant House’s Pilsen pub. Arize Kombucha distributes nearly 500 gallons of fermented probiotic tea monthly to area grocery stores. Four Letter Word Coffee, a boutique coffee roaster, has a roastery on the second floor. Whiner Beer Co. specializes in Belgian-style ales and operates a taproom inside the Plant. Justice Ice makes crystal-clear ice for use by Chicago’s best bars and restaurants for their cocktails. The Plant also has an outdoor farm, an indoor aquaponic farm that grows an average of five pounds of greens a week, an indoor tilapia farm and hatchery, a mushroom farm capable of growing 500 pounds of oyster mushrooms a month, and an apiary for making honey.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow

The Plant has an outdoor farm and an indoor aquaponics farm on the basement level.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow

With all of that happening, waste is bound to pile up. And the Plant repurposes over 90% of the waste byproducts created by its tenants. Waste from the fish farm and carbon dioxide from kombucha production is used to fertilize the greens in the aquaponics farm, which in turn filters the water that goes back to the tilapia farm. Spent grain from the brewery is used to feed the fish and for Pleasant House’s baking purposes. The Plant’s tenants even repurpose as many building materials as possible. The bar, tables and seating inside Whiner Beer Co.’s taproom was made from reclaimed wood. Pleasant House uses scrap wood to fire its ovens. Sections of the former slaughterhouse's hanging rooms (where beef and pork were processed assembly line-style and aged) are now bathrooms that comply with the Affordable Care, and other sections are being rebuilt into an information center that will open in the fall.

Chuck Sudo/Bisnow

The Plant is in the process of installing a digestible aerator that will produce methane and fertilizer for The Plant's internal uses and outside uses.

The linchpin in the Plant's circular economic model is a 100-foot-long anaerobic digester. This machine is capable of breaking down biodegradable material without oxygen to create methane gas to power the Plant's electrical generation systems, algae and duckweed to feed the tilapia, produce enough process heat for use by the brewery, coffee roaster and baker, and make fertilizer for the outdoor farms. The digester is capable of producing 2.2 million BTUs of biogas. On a smaller level, the Plant is also experimenting with making biobriquettes, a hockey puck-sized brick of biomass from spent grain and coffee chaff, that can be used as fuel in the bakery's ovens instead of wood.

The Plant's circular economy has the possibility of being adapted on a larger scale. A French food engineer and Brazilian urban engineer spent their internships at the Plant analyzing material flows in order to create methodologies to determine if the Plant's closed loop system can be used for developing more efficient urban ecosystems and sustainable cities.

Related Topics: The Plant, Bubbly Dynamics, John Edel, union stock yard, packingtown, Chicago stockyards, Chicago sustainability, Chicago adaptable reuse

Jakartans To See More Urban Farming

Jakartans To See More Urban Farming

Agnes Anya | The Jakarta Post

Jakarta | Tue, May 23, 2017 | 08:05 pm

A man waters plants in a vertical garden in Cikini, Central Jakarta. The city administration plans to build 75 more such gardens, in addition to the existing 150. (Courtesy of Jakarta Fisheries, Agriculture and Food Security Agency/-)

Jakartans will have a greener city soon as the city administration is promoting urban farming in the capital.

The Jakarta administration plans to introduce "green aisle" program in 75 areas to grow vegetables, medicinal plants and potted fruit plants this year, aiming at not only beautifying the city but also to ensure food security.

"We want residents to know that farming is easy. In the future, we hope that they can produce vegetables for their own families," Fisheries, Agriculture and Food Security Agency agriculture division head Diah Meidiantie said.

The administration has allocated Rp 5 billion (US$ 375,855) for the program.

Last year, the agency disbursed Rp 6 billion to establish 150 urban gardens in the capital's five municipalities and Thousand Islands regency.

"However, this year, Thousand Islands won’t join the program as the local residents are struggling to care for the existing ones," Diah said, explaining that the difficulty was caused by a lack of clean water in the regency.

Topics :

Emphasizing Product Quality Over Narrative, an Urban Farming Enterprise Thrives

Emphasizing Product Quality Over Narrative, an Urban Farming Enterprise Thrives

Michael Ableman, Co-founder of Sole Food Street Farms, an urban farming social enterprise in Vancouver, Canada. Photo courtesy of Sole Food Street Farms.

May 30, 2017 | Trish Popovitch

Careful planning, adequate startup capital and experience working on a traditional rural farm are just three of the elements that veteran urban farmer, and co-founder of Vancouver’s Sole Food Street Farms, Michael Ableman feels are necessary to be successful in the new urban agriculture movement. Founded in 2008, Sole Food Street Farms would be considered by many growers as established and successful, but for Ableman there is still much work to be done both at Street Farms and in the development of the city farm movement.

“The skill level required to be a farmer is not something you get just by wearing the right clothes, having the right tools and having started last year. It takes five to ten years to develop that skill level,” says Ableman. “What we’re trying to do is demonstrate that it is in fact possible to have a credible model of agriculture in the city, so the scale and production levels, the volume we produce, the number of people we employ is significant.”

Employing 20 to 30 well trained local residents (most recovering from addiction or managing mental health issues) and producing 25 tons of food every year for sale though farmers’ markets, a CSA and to approximately 50 of Vancouver’s top restaurants and eateries, Street Farms offers a viable agricultural model for city farming based on scale and sustained success.

Street Farms may occupy approximately five acres of space in an urban slum, and it may employ one of North America’s most underserved populations but despite that, Ableman is adamant that his customers should buy his product because of its quality and not its narrative. “We’re not asking people to buy our food out of some sense of charity, or a belief system or our story, which is a good story, but we’re asking them to buy because it is high quality food. We don’t get a pass to be not good farmers,” says Ableman. The farm averages $350,000 in annual income from sales and programming.

For Ableman, who came into the project as a consultant and now acts as Managing Director, the city farm is a social catalyst and its sustainability lies in its larger social mission. “Our experience has proven giving people a reason to get out of bed each day, meaningful employment, a place for people to come to learn new skills, a community that depends on them […]. Really it’s been the people of that community that in many ways helped themselves,” says Ableman. “We provided the setting for it to happen.” A study by Queens University in 2013 calculated that for every dollar Street Farms pays a member of staff, it creates a $2.20 savings to local health, social and legal services.

Street Farms employees grow their fresh produce in custom built growing boxes. As the farm reduces to a skeleton crew in the winter months, Ableman sees the boxes as a way to keep folks employed and meeting their recovery goals. “The boxes address a number of problems. They address short-term leases, they address contaminated soil…if you have to move at short notice…. We get more requests for the boxes than the produce growing in them. We’re looking at trying to find a warehouse. Our idea would be to start manufacturing and distributing them within the next year,” says Ableman. This value added product must be cost effective and currently Ableman and his team are working on how to reduce the per unit cost to make them both affordable to buy and reasonable to make.

Much of what Ableman and fellow founder Seann Dory have learned in the last few years, as well as Ableman’s urban agriculture manifesto and some general advice on urban farming are surmised in Street Farm: Growing Food, Jobs, and Hope on the Urban Frontier, a book Ableman released last year which he feels will help would-be city farmers to realize the true scope of commercial growing. “I’m not trying to be discouraging,” says Abelman. “I’m trying to give people a better shot at being successful.”

With over 40 years of farming experience and deep roots in the sustainable city farming movement that stretch back to the 1980s, Ableman hopes that his project in Vancouver will encourage more social enterprise-focused urban farms and for growers to realize that in today’s social and economic climate, profit as priority is old hat.

“We have a responsibility to be self sustaining economically but I also think we have an obligation in any business to address the broader goals and needs of our community and our society,” says Ableman. “I don’t believe it is enough to be in business just to be in business. We all have an obligation to extend the work we do beyond just making money. No-one that lives on this planet, at this time, can solely live and survive without considering the impact of their actions.”

AeroFarms To Open World’s Largest Indoor Farm In Camden

AeroFarms To Open World’s Largest Indoor Farm In Camden

By Gillian Blair - May 30, 2017

Credit: AeroFarms

AeroFarms will soon surpass itself as the world’s largest indoor vertical farm with a second and larger New Jersey location in Camden. Set to be operational by 2018, Farm No. 10 will be 78,000 square feet on the 1500 block of Broadway. They are still working on the design of the facility and will need to gain local zoning approvals, but the biggest victory was already won when AeroFarms LLC was awarded an $11.14 million grant in tax incentives by the New Jersey Economic Development Authority.

Farm No. 9 in Newark, New Jersey, is currently the world’s largest indoor vertical farm based on annual growing capacity and where, in a converted steel mill, they harvest up to 2 million pounds a year. AeroFarms is able to germinate seeds in 12 to 48 hours–a process that typically takes 8 to 10 days–and focuses on growing leafy greens like baby kale and arugula and packaging under the name “Dream Greens” for distribution locally in North Jersey and Manhattan. Farm No. 10 in Camden will supply South Jersey and Philadelphia.

The greens are grown “aeroponically,” meaning the roots grow downward, dangle in the air, and are misted with water and minerals. And the process dispenses with premium elements like land and water: “We can grow on one acre what would normally take 130 acres on a field farm. And we use 75 percent less water [than hydroponics],” said Co-founder and CEO David Rosenberg.

AeroFarms has come far since Farm No. 1 in a converted kayak shop in Ithaca, New York, where Ed Harwood, an associate professor in the Cornell University School of Agriculture, became interested in growing things without the elements that grow things: soil, sunlight, a lot of water. Now Co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer, his biggest breakthrough was developing the root mister that doesn’t clog. Also developed for this practice of vertical farming is a cloth made of recycled soda bottles on which the seeds germinate and through which the roots grow downward.

Even the lighting is specially calibrated and everything is monitored electronically. AeroFarms recently won a “vision” award at the Global Food Innovation Summit in Milan which was an especially exciting honor as it recognizes “the coolest vision of how the world should work,” said Mr. Rosenberg.

The tax incentives enabling AeroFarms to open their second facility in Camden are part of the Grow New Jersey Assistance Program Grants which incentivize businesses to relocate or start-up in economically challenged areas, infusing the local economy, workforce, and property with capital, opportunities, and improvements.

Have something to add to this story? Email tips@jerseydigs.com. Stay up-to-date by following Jersey Digs on Twitter and Instagram, and liking us on Facebook.

The Urban Farmer: Interview With João Igor of CoolFarm

The Urban Farmer: Interview With João Igor of CoolFarm

In Future trends Posted on May 25, 2017

Created out of necessity, CoolFarm now offers smart farming solutions that allow you to plug, play, and produce fresh food all year round. Get the inside scoop on how co-founder João Igor has discovered a novel way to make agriculture an integral part of urban life.

If you haven’t heard about urban farming, you must have been living under a rock for the past few years! City-based agriculture offers the opportunity to have healthy food in abundance, at a fraction of the cost, by growing only what we need, close to home.