Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Urban Farms, Beacons of Self-Reliance, Change The Buffalo Landscape

Buffalo’s urban farms have grown mostly organic crops as they’ve nurtured community involvement, including in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. (Mark Mulville/Buffalo News)

Urban Farms, Beacons of Self-Reliance, Change The Buffalo Landscape

By Scott Scanlon | Published 12:04 p.m. September 8, 2017

Mayda Pozantides slings burgers two nights a week in an Allentown restaurant but her career aspirations involve something much more grounded.

She wants to be a full-time farmer in the City of Buffalo.

Pozantides, 30, and her boyfriend, Anders Gunnersen – operations director with Buffalo Reddy BikeShare – bought a patch of land three years ago on the East Side. They spent two years stripping it of brush, rock and chunks of blacktop. This year, they brought in new soil and planted a large slate of vegetable crops.

"I used to be a teacher and Anders used to do environmental education," Pozantides said. "We want to bring that element to the farm. We're building slowly."

Groundwork Market Garden – a roughly 2-acre plot at Genesee and Leslie streets – is among several urban farms that have emerged in the city during the last decade.

While not self-sustaining, each in its own way has helped inspire the creation of community and residential gardens across the city, underlined the importance of access to healthy, affordable food, and helped serve as a linchpin in ongoing efforts to revitalize neighborhoods.

Each faces similar challenges: the cost and work involved in creating proper soil conditions; access to a cheap, dependable water supply after city regulations ended their use of hydrants; and looking to boost crop yields as they battle deer, woodchucks, rabbits and a limited Western New York growing season.

Dogs and fencing have slowed the critters. Grant money from the U.S. Department of Agriculture has helped some farms build high tunnels – also called hoop houses – that allow planting and harvesting even in the winter months. A cooperative called the Farmer Pirates is among those providing compost to help bring urban farm soil into a more hospitable pH to grow fruits and vegetables.

"A lot of the farmers have reasons they're farming that are other than financial…," said Megan Burley, farm business management educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension of Erie County. "Still, without a margin, there is no mission."

Mayda Pozantides takes a cover off of some vegetables at the Groundwork Market Garden on Genesee Street. This marks the first year the farm has yielded crops. (Mark Mulville/Buffalo News)

Urban farm owners in Buffalo all aim to serve as beacons of the local food movement, symbols of simple self-reliance, and examples that simple ideas that can work at the grassroots level. Some have a spiritual mission; all, a social one.

Eleven urban farms help lead the way in Buffalo. Several will be stops on the ninth annual GObike Buffalo Tour de Farms bicycling event next Saturday, Sept. 16. For more information and to sign up, visit tourdefarmsbuffalo.org.

5 LOAVES FARM

1172 West Ave.; 5loavesfarm.org

“Garden Egg” eggplant is among the immigrant-favored crops grown at 5 Loaves Farm on the West Side. (Mark Mulville/Buffalo News)

Matt Kaufmann is the farm manager for this Upper West Side farm, which since 2012 has expanded from three lots at West and West Delevan avenues to a couple more lots a block north.

The nonprofit farm is ministry of Buffalo Vineyard Church and is tended by Kaufmann; assistant manager Seth Brown, the lone paid farmhand; and a collection of volunteers from schools, community groups, the mayor's summer youth program, Buffalo Urban Ministries Partnership and 716 Ministries.

More than 80 vegetable varieties are in the ground here. They include amaranth, Asian cucumber and original white, egg-sized eggplant – all popular with recent immigrants in the neighborhood. Produce from the farm goes to 40 members of the 5 Loaves CSA, the Tapestry Charter School lunch program and the Lexington Food Co-Op. Much of it also is sold from 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. Saturdays through October at the Elmwood Village Farmers Market.

COMMON ROOTS URBAN FARM

309 Peckham St.; commonrootsurbanfarm.com

Terra Dumas started the farm five years ago and brought on partner Josh Poodry, who also owns a landscaping business, two years ago. The farm sits on 11 lots where nearly 40 vegetable varieties are grown for 83 CSA members and a farm stand on the property. The stand is open 4 to 7 p.m. Thursdays and 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. Saturdays through mid-October.

The owners dug a well on the site this year to better supply their crops with water and also erected a hoop house that has boosted tomato production. Students from SUNY Buffalo State and the nearby School 31 are among those who will help Dumas and Poodry tend the farm this fall.

FARMER PIRATES

Foot of Gittere Street, off Sycamore Street; farmerpirates.com

The Farmer Pirates are a farm collective that has purchased lots on the East Side in an effort to promote healthy eating and self-reliance. Those who tend urban farms and large gardens are welcome to participate. Farms in the fold include Common Roots, Wilson Street, the homestead off Gittere Street and the planned Michigan Riley Farm off Michigan Avenue, north of the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus.

"Growing food in the city is often cited for its potential economic benefit," the Pirates say on their website. "Whether or not urban farming is an economically viable profession, let alone holding the potential for economic development, the real value growing food in the city is the potential to improve quality of life and strengthen communities."

GROUNDWORK MARKET GARDEN

1698 Genesee St.; facebook.com/groundworkmg

Mayda Pozantides says the Groundwork Market Garden wind tunnel, along Genesee Street, has produced 300 to 500 pounds of tomatoes weekly in recent weeks. (Mark Mulville/Buffalo News)

Cornerstones of the farm this first growing season have become a large wind tunnel that holds about 300 tomato plants, as well as the recent purchase next door of a three-story, 40,000-square-foot former manufacturing building that will be turned into a mixed-use project that helps support the farm.

Pozantides and Gunnersen sell their produce to the 20 members of their CSA – as well as neighbors who stop by Tuesday evenings for CSA pickups. They also sell produce at the North Buffalo Farmers Market from 3 to 7 p.m. Thursdays through October at Holy Spirit Church, 85 Dakota St., near Hertel and Delaware avenues.

JOURNEY'S END BREWSTER STREET FARM

Jan Rai and other refugees who farmed in their native country help tend a small farm behind the Tri-Main Center as part of a Journey's End program. (Mark Mulville/Buffalo News)

36 Brewster St.

Refugee farmers – mostly from Bhutan of Nepalese descent, Congo, Palestine and Syria – help tend two patches on a small side street behind the Tri-Main Center at Main Street and Jewett Parkway. They earn a small wage as part of the Journey's End Green Schools for New Americans program, Program Manager Beth Drouhard said.

Sixteen farmers tend more than 30 vegetables at the farm, which includes a hoop house. Produce here helps feed 20 CSA members and those who stop by a market table from 1:30 to 6 p.m. Thursdays in the Tri-Main Center. The program also will provide free produce at 2 p.m. Wednesday alongside the Brewster Street farm, while supplies last.

MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE PROJECT (MAP)

389 Massachusetts Ave.; mass-ave.org

Established in 1992 and incorporated in 2000, this nonprofit farm operation on the West Side is the largest urban farm force in the city. Since 2003, its Growing Green program has provided jobs and training to more than 700 low-incomeyouths ages 14 to 20.

MAP looks to open its new $2 million Farmhouse & Community Food Resource Center next spring. It will include a teaching kitchen, meeting and training space. The farmhouse has swallowed nine of a dozen tracts on its main farm, limiting production this season. Its produce is available at two weekly MAP Mobile Food Markets: 4 to 6 p.m. Thursdays through October at Elim Christian Fellowship, 70 Chalmers Ave.; and 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. Fridays at the Moot Senior Center, 292 High St.

"The construction is really limiting us," Development Director Erin Carmina said. "Next year we'll be in full swing," including other farm plots on Winter and Breckenridge streets.

PELION URBAN FARM

206 Best St., facebook.com/PelionCommunityGarden

Pelion Urban Farm grows fruit, vegetables and flowers. (John Hickey/Buffalo News file photo)

Garden Manager Caesandra Seawell has led the transformation of four vacant city lots across the street from City Honors into an outdoor school and community garden.

The garden – a key part of the school's fifth- and sixth-grade curriculum – includes a rain garden, a dozen raised beds for vegetables, fruits, and herbs, edible flowers, and cherry, plum, peach, and native serviceberry trees.

Bordering neighbors also have been encouraged to plant crops in raised beds on the site. Produce here is tended by volunteers and students. Some of it makes it home to families, Seawall said, though much of it doesn't even make it across the street and back to school.

PROMISE VALLEY FARM

462 Elk St.; between Orlando and Babcock streets; facebook.com/SenecaGospelMission

Seneca Gospel Mission is a Christian ministry that started in a Seneca Street storefront in 1936 and moved to the Valley Neighborhood of South Buffalo two years later. Promise Valley started as a small garden tended by children and became an official urban farm last year with the hiring of Farm Manager Aaron Belleville.

"The produce goes to 12 CSA members; our NeighborShare program allows donations to subsidize costs to qualified local residents in Seneca Babcock and the Valley neighborhoods which have no fresh food access and oftentimes lower incomes," said John Brown, resident executive director of Seneca Gospel Mission.

The mission is installing a commercial kitchen and continues renovation of its ministry center for future food education and ministry programs. "We're also raising funds for a hoop house for next season," Brown said.

URBAN FRUITS AND VEGGIES

Dupont Street at Glenwood Ave.; urbanfv.com

More than 20 raised beds sit on a corner parcel and a second site nearby on Glenwood. Owner Allison DeHonney started this venture in late 2013 as both a nonprofit and limited liability company farm. DeHonney and farm manager Sandra Bynum gather vegetables from the urban farm, coupled with fruit from a pair of growers in Niagara and Erie County, to provide to corporate wellness programs for eight companies, including New Era Cap and Lawley insurance, and the new Neat restaurant in Clarence.

DeHonney also looks to build greenhouses, starting as early as this fall, at Zenner and East Ferry streets, as part of a Bailey Green sustainability and revitalization project spearheaded by Harmac Medical Products.

WEST SIDE TILTH FARM

246 Normal Ave., at Vermont Street; facebook.com/westsidetilthfarm

Started as an urban farm this year to provide its West Side community with naturally grown produce using sustainable practices. Vegetables, herbs, micro greens and mushrooms are produced at this farm, much of it in a new hoop house.

"We got our first batch of oyster mushrooms last week, which is exciting," said Carrie Nader, who owns the farm with her partner, Alex Wadsworth.

Much of their produce makes its way to the new Roost restaurant on Niagara Street and 100 Acres Kitchen in the Hotel Henry. Their salad mix is served at both Lexington Co-Opp salad bars. The farm stand, around the corner at 235 Vermont St., will be open 5 to 7 p.m. Fridays through September.

WILSON STREET URBAN FARM

Six of Janice and Mark Stevens' children help them on the family's Wilson Street Farm; a seventh, Alex Ash, helps her husband, Dan, tend the homestead farm for Farmer Pirates. (Derek Gee/Buffalo News file photo)

Wilson Street, between Broadway and Sycamore Street; wilsonstreeturbanfarm.wordpress.com

Janice and Mark Stevens, parents to seven children, operate this nine-year-old farm, which launched the urban farm movement of recent years in Buffalo. "We grow everything but corn," Mark Stevens said. Produce is sold at a farm stand that has closed for this season, as well as to 14 CSA members through October. The farm also helps supply several restaurants and Five Points Bakery.

Steven is a carpenter who does contracting work, helping the family subsist on the East Side. "The farm is not self-sustaining but Janice and I come from a homesteading background. We're terrible salespeople who love to eat what we grow, so we eat up most of our profits."

He's from Olean; she's from Rochester. "We're really about building a good community, a good neighborhood," he said. "All of the urban farms have a slightly different slant on things. We're more on the community building aspect of it. Whether we make a living is not exactly our point on things."

email: refresh@buffnews.com

Twitter: @BNrefresh, @ScottBScanlon

Story topics: urban farms

Vertical Harvest To Partner In Pennsylvania Project

Vertical Harvest To Partner In Pennsylvania Project

60,000 sq.ft. Vertical Greenhouse To Bolster Lancaster's Less Fortunate

Inspired by Vertical Harvest in Jackson Hole, a group of Pennsylvania entrepreneurs has announced an ambitious plan to realize a similar community-supporting vertical glasshouse downtown Lancaster. By partnering with their industry peers in Wyoming, the group soon hopes to break ground for the construction of the 60,000 square feet project on the side of an existing parking garage.

The Lancaster Urban Farming Initiative was founded by a group of entrepreneurs with a shared social ambition to re-develop underutilized infrastructure with urban farming projects to bring in jobs, gain availability of local produce and provide beautification of the downtown area.

Soon after they started their in-depth analysis of opportunities and locations, Lancaster mayor Rick Gray got acquainted with their initiative and composed the idea for a vertical farm at the local Orange Tree parking garage. "He showed us a picture of the Vertical Harvest greenhouse in Jackson Hole and asked us if we could do the same. And a few years later here we are, about to complete our feasibility study for a similar farm and design, only three to four times larger in size", representatives of the initiative said.

The project will be built onto the side of the garage, using a space that really cannot be used for anything else. The walk faces the famous Lancaster Central Market which is the oldest continually operating Market in America. It is the heart of the city and walking out, visitors will soon see an impressive vertical greenhouse rather than a brick wall.

Vertical Harvest will partner in the non-profit Lancaster vertical farm that is touted as bringing in jobs to mentally underdeveloped and disadvantaged and disabled people, as well as veterans, people with Down syndrome, autism or those who are unemployed or underemployed. "We want to provide them with a rewarding job in high tech agriculture. We will also create partnerships with local hospitals and industries to support the local community and its access to local, healthy food."

Aside from providing jobs, local food and making underdeveloped parts of the downtown area walkable again, the Farming Initiative also hopes to sprout the development of indoor agriculture in general by becoming a technology leader. Their facilities will grow a variety of crops in several production systems. It will serve as a dedicated testing space to trial new innovative vertical growing systems. The group said it will incorporate the latest in hydroponic and LED systems, and might even consider bringing in cogeneration to supply the greenhouse with a sustainable energy source.

The Lancaster Urban Farming Initiative is currently in the process of completing funding. Up next is going through the design phase, which is expected to take a while, since building a vertical greenhouse is also a challenge in terms of strict building codes and complex architecture. Nonetheless, the group hopes to kick off the construction early to mid 2018.

Follow the development at www.lancasterufi.org and www.facebook.com/lancasterufi

The Lancaster Urban Farming Initiative Board of Directors:

- President - Corey Fogarty - Federal Taphouse Holdings LLC

- Vice President - Todd Bartos, Esq. - Aspire Ventures / Spruce Law Group LLC

- Secretary - Gordon Kautz II - Kautz Construction / KC Green Roofing

- Treasurer - Scott Arment, CPA - Stutz Arment LLP

- Mary Ann Garrett - Owl Hill Learning Centers

- Ross Martin-Wells, Ph.D - Rijuice LLC

- Mark Pontz - Fine Living Lancaster

- Fritz Schroeder - Lancaster County Conservancy

- Joe Sheldon - Gordon Food Service

- Scott E. Kuhn - Wells Fargo Bank

- Publication date: 9/6/2017

Author: Boy de Nijs

Copyright: www.hortidaily.com

Downtown Farmer Raises Salad greens Year-Round Inside Freight Container

Harris, who sold his steel company a couple of years ago, had little experience in farming or gardening before he created Green Collar Farms , a "hydroponic vertical micro farm" located inside of a green and white re-purposed shipping container parked in a vacant lot on the city's lower West Side.

Downtown Farmer Raises Salad greens Year-Round Inside Freight Container

Updated on September 5, 2017 at 8:10 AMPosted on September 5, 2017 at 8:03 AM

GRAND RAPIDS, MI - Brian Harris is not a traditional farmer. But neither is the tender kale, spicy arugula and crispy pak choi he raises inside of a converted freight container on the edge of downtown.

Harris, who sold his steel company a couple of years ago, had little experience in farming or gardening before he created Green Collar Farms, a "hydroponic vertical micro farm" located inside of a green and white re-purposed shipping container parked in a vacant lot on the city's lower West Side.

"I'm fascinated with process and solving problems," said Harris, an engineer by training who became fascinated after a friend gave him some literature on growing vegetables indoors. "The challenge was, how do you do this indoor gardening and I could not be denied."

Harris, who also chairs the Downtown Development Authority, said he experimented with hydroponics and indoor gardening in his home's basement for several years before he got serious and bought his 350-square foot container.

The container, which once served as a refrigerated vessel for international shipping, now is lined with vertical trays in which plants are placed. Fertilized water flows through the foam in which the plants are held while ribbons of LED lamps offer just the right blend of blue and red rays to feed the plants.

The setting yields bumper crops of leafy greens and lettuces, including kale, arugula, bibb, butterhead, deer tongue, mustard, pak choi, spinach and tatsoi.

Thanks to the stress-free environment, Harris says his plants are tastier, more tender and more consistent than his field-grown competition. He's planning to add a second container to raise herbs such as basil, chives, mint, oregano and thyme.

Inside the container, Harris is able to control the temperature, the humidity and the amount of light his plants are exposed to every day. The computerized controls are set up so he can control the indoor farm from his home or cell phone.

Harris germinates the plants himself from pelletized seeds he places inside water-absorbent seed plugs made of coconut husks. Placed under lights on trays, the seeds germinate within a week before they are transplanted into the vertical trays, where they get 16 hours of light every night.

The controlled environment means he does not have to treat the plans with herbicides, pesticides or fungicides. He uses just 5 percent of the water a traditional soil farmer would consume. The container also allows him to raise his crops year-round regardless of weather conditions outside.

The container, which houses white vertical trays in which he places seedlings, produces as many plants as a dirt-based farm would produce on 1.5 to 2 acres, Harris said. He estimates he will be able to produce crops on a 6-week cycle.

Harris said his $90,000 investment in container farming is being duplicated around the world as growers use "controlled environment agriculture," or CEA, to combat weather conditions that include desert heat, frozen climates, drought and flooding.

As his first crops reach maturity, Harris is now scouting for restaurants and grocers who want to stock his hyper-local and super-fresh crops.

Ultimately, Harris said he wants to find a building in the city where he can create a vertical garden in about 10,000 square feet. That will allow him to create jobs and economic opportunities in the city.

"Year-round indoor vertical farming has great potential to invigorate underutilized parts of Grand Rapids," Harris said. "We're not just trying to grow kale; we're trying to grow community vitality."

Harris also hopes Green Collar Farms will have a positive impact on young people, creating an interest in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM).

"Vertical indoor farming is a wonder to see and can spark the imaginations of young people to learn not just about STEM subjects, but also plant biology, agriculture and nutrition. This could prepare students for future careers and help them better understand where their food comes from."

Why Agtech Grows In Brooklyn

Aug. 30, 2017 12:59 pm

Why Agtech Grows In Brooklyn

We've seen an abundance of agtech activity in the borough. But why here?

A rooftop greenhouse in Brooklyn. (Photo courtesy of @oneminutemeal)

By Nina Sparling / CONTRIBUTOR

The Brooklyn landscape is going green — and not just on rooftop farms. Of late, the borough has seen an explosion of innovation about how to grow fresh, healthy food in the heart of the city.

Digging beds on rooftops and harvesting baby radishes under the summer sun is rather 2010. This year, Blue Planet Consulting will reveal its +farm — a build-it-yourself, modular hydroponic farm unit for the home. Agrilyst is refining its workflow and data management software for indoor farms to automate aspects of the industry. Re-Nuble brought its fertilizer for hydroponic and soil applications derived from wholesale food waste to market in late 2016.

The agriculture technology industry (agtech for short) has seen extraordinary growth in Brooklyn in the past several years. Local entrepreneurs are pushing the boundaries of what urban agriculture looks like despite the fact that New York appears an unexpected home for such disruption in farming space. Nevertheless, Brooklyn has become a fertile environment for the future of food.

But why Brooklyn and not, say, Bakersfield?

It started with farm-to-table. Eaters borough-wide (and further afield) started thinking about where food comes from. Michael Pollan pleaded citizens to “vote with your fork.” “Local” food rose to — and perhaps surpassed — the level of “organic.”

Consumers began to embrace what industry leaders like Dan Barber and Alice Waters had espoused for decades: Where food comes from matters. And Brooklyn has necessary ingredients like the intersection of passionate chefs and a thriving network of farms.

“It’s hard not to be inspired by that pulsing entrepreneurial spirit,” Meg Savage, head of business development at food mag Edible told Technical.ly. “This is a community that cares about it’s food and where it is coming from … and longing for more advances.”

Edenworks microgreens. (Courtesy photo)

For businesses in the agtech space, the consumer and demand side provides plentiful momentum for continued growth and innovation.

“Rather than having a burden on the food system creating this large carbon footprint of having to bring food from as far as California, people are interested in how can we grow the same thing here,” Tinia Pina, founder of the organic fertilizer company Re-nuble said in an interview.

But operators — the industry word for farmers — in the agtech space are thinking about supply, too. Projections suggest the global population will exceed 9.7 billion by 2050. With New York City populations predicted to grow 9.5 percent by 2040, many agtech companies are focused on how to provide fresh and healthy food in ever more dense urban environments. “There is definitely a need to have more resource efficient localized production, distribution and consumption of resources related to food,” said Pina.

Most companies growing high-tech crops focus on leafy greens and fresh herbs. In New York, this makes sense, suggested Allison Kopf, founder of Agrilyst. “We have an interesting agricultural economy where it is a really big agricultural state. But the things that New York can specialize in year-round is very limited because of the climate and different sort of seasonality.”

The first agtech companies cropped up in Brooklyn in the 2009–2011 period. Industry leaders like EdenWorks, Gotham Greens and AeroFarms played a key role in laying the groundwork for innovation. “Smaller companies are following suit based on the population and population needs,” said Liz Vaknin, cofounder of Our Name is Farm, a digital and experiential marketing company. “In general, Brooklyn is an open-minded type of place to test out concepts.”

Seeds. (Photo courtesy of @oneminutemeal)

The result is something like an ecosystem.

“Once you have investors and customers then you have technology companies that are interested in selling products to that industry,” said Kopf. “You have companies like us and others sprouting up. A lot of it had to do with the market opportunity that is New York and the supporting resources that needed to exist just sort of do exist [here].”

And ample room for innovation and development remains.

Agtech is still young. Many of the companies involved are just a few years old, if that. Excitement from investors is growing, but solid investment requires education and transparency.

“There is definitely room for more collaboration between operators,” said Re-Nuble’s Pina. “It’s hard, each farm has its own intellectual property that they’re trying to keep defensible so they can raise money. But in driving conversation with local stakeholders at the municipal and corporate levels, we need to work together to show how we can make the supply chain more sustainable.”

Funding is a major concern across the board. “We need intelligent capital especially on the loan side,” said Kopf of Agrilyst. “This is a massive infrastructure investment — far too often farms are trying to secure venture capital. But then banks have to understand the technology. Traditional farm loans don’t work the same way yet.”

Local policymakers are beginning to catch on. The Brooklyn Borough President’s office just announced $2 million in funding for an urban agriculture incubator. Further public infrastructure involvement could be a game changer. “If government money is available, the terms are going to be different than private equity money or venture capital funds,” said Vaknin. “All together, that kind of creates a perfect storm for robust growth.”

Edenworks microgreens. (Courtesy photo)

The Finish Line Debuts On-Campus Farm

The Finish Line Debuts On-Campus Farm

Posted: Aug 24, 2017 4:23 PM CDTUpdated: Aug 24, 2017 4:23 PM CDTBy Dan McGowan, Senior Writer/Reporter

(Image of The Finish Line's Urban Farm courtesy of the city of Indianapolis.)

INDIANAPOLIS - Indianapolis-based The Finish Line Inc. (Nasdaq: FINL) has marked the opening of a 7.3-acre farm on its corporate campus on the city's east side. The athletics retailer says the farm is one of the largest in an urban setting in the state. The urban farm is a collaboration with Greenfield-based Brandywine Creek Farms and will produce cantaloupe, tomatoes, cucumbers, bell peppers and zucchini and include space for 250,000 bees.

The vegetables grown on the farm will be distributed by Brandywine Creek Farms evenly to the wholesale market, to retailers and to charity. Total Rewards by Finish Line Senior Director Kim Kurtz says "by growing and sharing this produce, we will develop a healthier community together including our Finish Line family and our nearby neighbors."

The goal, officials say, is to provide employees and the public with fresh and affordable food that can be stored at room temperature.

Are You Really Ready To Start Your Urban Farm Operation?

Are You Really Ready To Start Your Urban Farm Operation?

AUGUST 15, 2017 | URBAN AG NEWS

By David Ceaser

So, you have been dreaming about starting an urban farm or are about to launch your new career with an indoor farm. You have gotten funding from friends and family (and Kickstarter) but have you really dotted all the i’s and crossed all the t’s as far as what challenges you will be taking on as you get your business up and running?

The truth is that many urban farming operations enter the business from one perspective. They may be started by a grower who knows a ton about growing but little about the business and legal end of things. Or, the operation may be started by someone with a business perspective who wants to see a farming operation thrive, but has little knowledge of the daily ins and outs of running a farm.

Many urban farms fail. It’s good to be as prepared as possible when starting out so you don’t repeat the same mistakes as others.

Here are some important things to think about before getting started. Any one of these roadblocks could delay your project for several months so it’s best to look at these things ahead of time rather than letting them derail your progress.

Zoning, code issues

Since urban agriculture (as it’s known today) is a relatively new field, many municipalities are unfamiliar with it and do not have any sort of code on the books for how to permit your project. If you can’t obtain a permit, then you can’t obtain a business license.

Your options will be to move your project to another location where it is permitted, permit under a different classification such as a food processing facility (if you can convince the planning department), work without a permit (there are work arounds depending on the location of the facility) or wait until legislation is updated. Many city planning departments will not be familiar with indoor agriculture projects so it is very valuable to do your homework first.

It is good to have at least basic drawings to show them how the facility will be laid out and will operate. It is also good to be familiar with cities that have urban farming legislation on the books so that you can show that to local planning departments as needed.

Business model

What is your business model? How will you make money? Will you sell your product wholesale? To restaurants? Direct to consumers? To supermarkets? At farmers markets?

Each of these particular customers may require certifications before they will purchase your product. These might be as simple to obtain as county ag permits or as complex and expensive as organic certification or regular tests for pathogens. It is important to know what your customers will ask of you beforehand so that you are prepared.

Water

Water is a key ingredient in your facility whether hydroponic or soil-based. Important questions to consider are: Can you use the existing municipal water? Will you need to invest in expensive filtering equipment to remove excessive salts or metals? Are there restrictions on water use (such as in California)? Are there disposal issues to be educated about regarding disposal of nutrient-rich water?

Growing medium

Hydroponic farming can be done with different growing media. Do you have a guaranteed supply of that medium, especially for operations where the medium is only used for a short period of time and replaced? If you are looking for organic certification, does the medium meet the requirements for certification? If not, what alternatives are there? If you are using soil, what tests do you need to do and what adjustments will you need to make to the soil?

Electricity, energy

If you are running an indoor farm, energy costs can be one of the most expensive budget items. Using lights and dehumidifiers can really be expensive.

Do you know what your power rates are? Do you know when power is most expensive? Do you know how much light your plants need ? Is the electricity in your area reliable or should you have a back up generator on hand? Do you know how much power your facility needs and how much does the property you are looking at offers? Is the existing electrical system up to code? How much will an upgrade cost?

Floors

If you are running an indoor facility, floor design is of key importance. You need to simultaneously design your floor for multiple factors such as being able to be cleaned easily, drainage, traction and bacterial control.

Input sourcing

Just like when you are baking bread, if you run out of flour, you have a big problem. The same is true with your farm. You will have numerous inputs and if any one of them runs out, your production will be slowed or might even stop. Make sure you have a reliable source for all your inputs and a reliable backup source just in case.

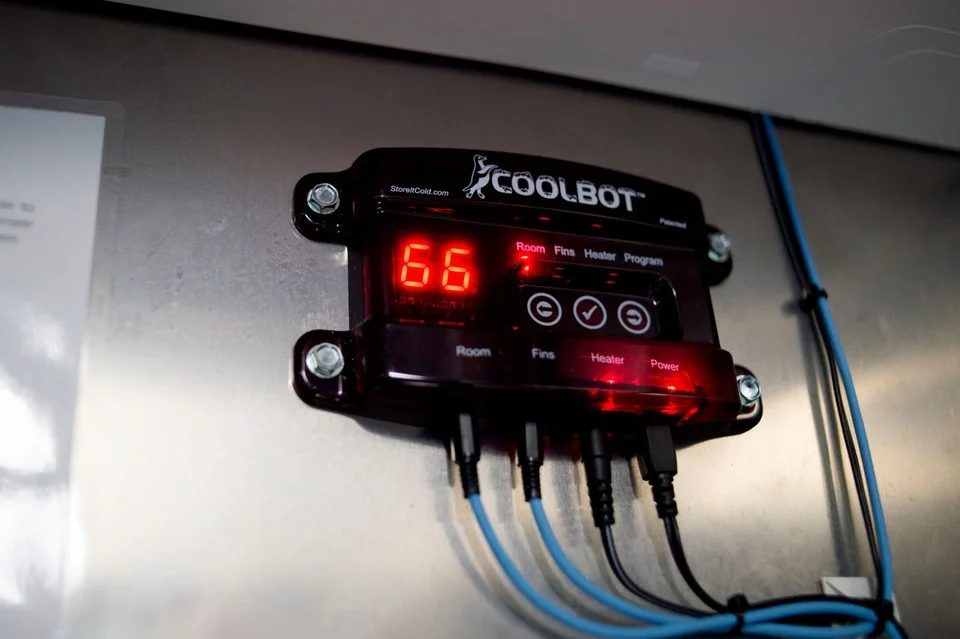

Controllers

So much of indoor farming and even aspects of outdoor farming are based on monitoring data and adjusting as necessary. What controllers will you use for your operation? How will you use the data that are being produced to your advantage?

Are you the type of person that feels more comfortable seeing everything in person and making adjustments on site or are you comfortable with making adjustments to your growing operation remotely? These questions are very important to think about before you get started so that production data can be easily understood and analyzed and the appropriate adjustments can be made to your operation when needed.

Perspective

When looking at your urban farming business, I have found it very valuable to analyze production and costs on a square foot basis. I have a background in real estate and using a square foot methodology has proven very valuable and easy to understand.

Full Cycle Planning

Many operations do intense planning for how to grow their product but don’t think about the best way to harvest and package until it is upon them. Unfortunately, harvesting and packaging can be very labor intensive and if not well planned beforehand, can turn a profitable venture into one that loses money. Talk with your buyers (especially supermarkets) about specific packaging needs they may have from the start and from there, plan a system that reduces labor costs whenever possible.

These are just some of the items that need to be thought about when launching an urban farming operation. There are many more that will undoubtedly arise based on your particular situation. If you are prepared with the ones listed above, it will significantly reduce headaches, time delays and money lost in your urban farming venture.

David Ceaser has over 20 years experience working with plants and agriculture in numerous capacities and countries. He has studied agroecology, horticulture and business along with several years working in real estate development. He currently does consulting work and operates a small outdoor urban farm specializing in herbs and salad greens. To contact David, please e-mail farmer@gsvfarm.com

The author would like to thank Will Kain for his time and insight in participating in this interview. Further gratitude goes to Chris Higgins of Hort Americas and the founder and editor of Urban Ag News.

Jim Pantaleo works to develop all aspects of indoor vertical farming and writes as an industry advocate.

Harlem Grown’s Tony Hillery: “Education Is The Way Out"

Harlem Grown’s Tony Hillery: “Education Is The Way Out”

Tony Hillery, Founder and Executive Director of Harlem Grown, will be speaking at the inaugural New York City Food Tank Summit, “Focusing on Food Loss and Food Waste,” which will be held in partnership with Rethink Food Waste Through Economics and Data (ReFED) and with support from The Rockefeller Foundation and The Fink Family Foundation on September 13, 2017.

Hillery founded Harlem Grown to address the health and academic challenges facing public elementary school students in Harlem. In 2011, he began volunteering at a local elementary school and witnessed first-hand the lack of resources allocated to the schools and the poor nutrition of students. He transformed an abandoned garden, essentially a junkyard, into a thriving community garden. Hillery worked with community members to clean up the garbage, purchase soil, and purchase 400 seedlings for 400 students. As the students’ plants grew, their eating habits were also transformed, and the students developed leadership and teamwork skills. That first season, they grew 38 pounds of produce.

Tony Hillery, Founder and Executive Director of Harlem Grown, will be speaking at Food Tank’s NYC Summit on September 13, 2017.

By 2016, Harlem Grown expanded to partner with six local Harlem schools, reach more than 4,800 youth, and grow more than 2,200 pounds of fruits and vegetables that are then distributed to families-in-need throughout the community. This year, Harlem Grown will open a brand-new farm on 127th Street to continue to reach more youth in Harlem and inspire them to lead healthy and ambitious lives.

Food Tank talked with Hillery about the collective impact these gardens have on the communities of Harlem.

Food Tank (FT): What originally inspired you to get involved in your work?

Tony Hillery (TH): One of my personal passions is education. I truly believe that education is the way out of a lot of situations. Once you have your education, it cannot be taken from you regardless of your socioeconomic position. Education is the way out. I kept reading about schools in the city, and I didn’t understand what I was reading. It didn’t make sense to me that we were living in one of the richest cities in the country, and we had such a disparity in education. I really didn’t understand it. I’m a show-me kind of guy, so I started volunteering at an elementary school in Harlem. That’s what did it. That’s what prompted everything else.

FT: What makes you continue to want to be involved in this kind of work?

TH: To be completely honest, I didn’t have a plan when I started this—it all, excuse the pun, came organically. My original mission was to work with parents on the importance of education in breaking the cycle of poverty, but my focus quickly turned to children. As I spent more time in the schools, the conditions of the underserved communities in this country became crystal clear. As a youth, I used to come to Harlem all the time. We would come to Harlem; we would party in Harlem, but then go home. You see it, but you don’t see it. That’s a lot of us in this country. We’re aware, but we’re not aware. The more time I spent here, the more obvious the problems became. And very quickly it shifted to nutrition, food access, and food justice. I’m convinced that poverty is just lack of access and lack of opportunity. In the schools where we work, there are no services. There’s no extracurriculars. There’s no art. Some of the schools don’t even have gyms or music. The children we serve come to school for reading, writing, and arithmetic as well as breakfast, lunch, and supper. They’re having their three meals in school, and yet they can’t even identify simple vegetables. It’s a huge disconnect. And that’s how this whole thing came to be.

FT: Do you think that working with kids is one of the biggest opportunities to fix the food system?

TH: Absolutely. Early on when I first started this, I did like a lot of people did. I started working in the school, and as fate would have it, across the street was an abandoned community garden. I got the garden and made it a farm. After the first crop, I was sending the kids home with some kale and some chard, and the next day I would ask the children, ‘so how do you like that chard?’ They said, ‘I don’t know, my mother threw it away.’ So mom doesn’t know what it is or how to prepare it. This is part of the problem. A lot of us nonprofits miss the mark. We come into the community to teach that community or to show the community. If you think about how I started this conversation, that’s exactly what I did. I came into this community to teach parents the importance of education. Who am I to come into a community? I’m not from here, and I don’t live here. And if you think about it, that’s insulting on its face. I mean, I’m telling you basically, ‘you’re living wrong, I’m living right. Listen to me, I know better.’

FT: Did you have push back on that from community members?

TH: No, not directly push back, but the delivery was disingenuous. It wasn’t what you would think. It wasn’t what I thought. I thought people would be so welcoming—’Oh yes, tell me, tell me.’ No, no, it’s not that. People will come, they will sit there, and they will listen. But they don’t hear you. People will come to these workshops and things for the endgame. What’s the endgame? Is it a bag of groceries? Is it a gift card? They don’t hear, they’re not taking in what’s being provided. So quickly I pivoted; I focused on the children. We don’t come into the community. We become the community. We’re here seven days a week. We see these children every day, in school, after school, and on the weekends. And from that, through that consistency, we build relationships and trust that is unbelievable. And that’s our method. We went from showing children vegetables, and they’re like ‘what’s that?’ and ‘ew, ew, ew.’ To whatever we pick up and say ‘check this out, taste this,’ they’ll put it right in their mouth without questions and no apprehension at all. And if they do it, their peers do it. There’s a whole ring of trust we’ve created with our children. And it is like the ripple effect, they bring their siblings, they bring their mothers, they bring their friends. And that’s how we’re growing it from the bottom-up—literally grassroots, a bottom-up approach.

FT: So by working with the kids, you have been able to impact the community at large?

TH: Absolutely. The population we serve is very, very challenged. The numbers move up and down, but overall, 80 percent of the children I serve are living in single parent households. Over 90 percent of my children live below the poverty line, 98 percent of our families are on food stamps, and 40 percent of the children we serve are homeless. That’s my population. So if you take a step back, nutrition is low on the list of priorities, if it’s on the list at all. We embrace the whole child. You can’t give a kid kale to take home when he doesn’t have a home or place to eat it.

FT: The work you’re doing is incredibly inspiring. What is the most inspiring experience you’ve had?

TH: Oh my god, there’s so many every day. That’s the beauty of working with children. Children are so genuine. There’s no agenda, and there’s no faking it. You get the unfiltered truth every day from these children. That is what keeps us on our toes. When we first started, we were working with children who not only didn’t eat anything green but couldn’t even identify vegetables other than a tomato and carrot. They got fuzzy on broccoli, and everything else is salad. And they didn’t eat salad. Today, they won’t have a meal without salad. And don’t give them iceberg or romaine; they want other leafy greens. They love chard. They love arugula. They love spinach. To see the change in the children that started with me six years ago is just amazing.

FT: What is one small thing that everyone can do to help make this big difference?

TH: Realize that we are the change. The average person wants to do something tends to get stuck in neutral; they don’t know how to proceed, they don’t know how to take the next step. I just say, take the step. There’s nothing holding you back but you. If you see an injustice, if you see a problem, try to fix it. It’s as simple as that. A lot of us just sit back and wrestle with it. Just get involved, and see where it goes. It’s not a job; it’s a passion, to do something you love is not working. It’s not a talent to make money. Anybody can make money. But who can change a life for the better? That’s what we have to ask ourselves. Who can do that? And that’s what we do here. And oh my goodness, it is so rewarding. Each day is better than the next.

FT: Do you have anything else you want like to share with us?

TH: I must say, the name of my organization is Harlem Grown, but this problem is not unique to Harlem; this is not black, white, or brown. This is poor. This is a poverty issue. I’m all over the country speaking. I see poverty that makes my kids look rich. You see the same landscape. You see miles of fast-food restaurants. The closest supermarket is nine, ten miles away and nobody has a car. It is the same landscape as here in Harlem, as it is in the bayou in Louisiana or in West Virginia. You see the same exact thing: lack of access, lack of opportunity, and lack of education. Our children eat badly because it’s close, it’s cheap, and it’s convenient. In six years of doing this work, I have yet to meet a mother who would not want three organic meals of healthy, fresh vegetables and food for their kids. But you can’t afford it, and you can’t get it. Food is not optional. You have to eat. And if there’s a bodega on every corner selling cheap, processed food, that’s where they go. We have these catch phrases. We always say, ‘children are our future,’ and if that’s true, we really have to do something for these children.

Hillery recently received a CNN Hero award. Read about it HERE.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The NYC Food Tank Summit is now sold out. Register HERE to watch the livestream on Facebook. A few tickets remain for the Summit Dinner at Blue Hill Restaurant with a special menu from Chef Dan Barber. Apply to attend HERE. If you live in New York City, join us on September 14 for our FREE outdoor dance workout led by Broadway performers called Garjana featuring many great speakers raising awareness about food waste issues. Register HERE.

Farming In A Shipping Container: It’s Happening In Grand Rapids

Farming In A Shipping Container: It’s Happening In Grand Rapids

POSTED 7:43 PM, AUGUST 29, 2017, BY JAMES GEMMELL

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. — Imagine growing food indoors without water, sun or soil – and making a decent living doing so.

Green Collar Farms vertical crops

Green Collar Farms LLC says it is West Michigan’s first indoor hydroponic, vertical micro farm. That’s a 350-square-foot operation inside a re-purposed shipping container, located at 530 Second Street NW in Grand Rapids. Green Collar Farms was founded by Brian Harris, who says vertical farming is a sustainable enterprise that has the potential to grow local food and provide middle income-level jobs in urban areas.

“The ultimate goal,” says Harris, “is that a person could make a middle-income living out of the crops that go to your local farm-to-fork restaurant, and groceries.” He believes that could help grow a community’s vitality, not just grow crops. Under-used spaces like vacant warehouses or dormant garages and basements could be transformed into vertical farms.

The hydroponic farming uses L.E.D. technology that Harris says is 60 percent more efficient, per watt used, than sunlight. How can the plants grow inside a container with no sunlight? Harris says plants “see” light differently than people, who mostly observe it in yellows, greens and oranges. But plants see sunlight in red and blue, and interpret it in terms of radiation. So, the L.E.D.s that are used inside the shipping container are a red-and-blue combination. “So, it gives the plant the little bit of blue it needs to have to wake up in the morning. And the red is really what makes it stretch.”

Green Collar Farms uses automated Controlled Environment Agricultural (CEA) techniques to operate year-round, regardless of season. It can produce hyper-local greens and herbs with a yield equal to the output of a traditional two-acre farm – while using only 10 percent of the water. Green Collar is supplying hydroponic greens like kale, leaf lettuces and herbs to select restaurants in Grand Rapids. And Harris plans to expand distribution to local grocery stores, markets and even school cafeterias.

He figures that will benefit students. And that the L.E.D. technology will attract and introduce them to hydroponic vertical farming: “I think if you bring some kids in here, and they see these lights, it’s like Star Wars. And I think at that point, I’ve got them where I can start talking to them about the biology of plants. Start talking to them about engineering. Introduce them to the ‘what ifs’ of innovation.” He says that spark an interest in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM), as well as plant biology, agriculture and nutrition.

Harris envisions upscaling the vertical-farm concept up to 20,000 square feet, boosting the crop output significantly. He says that will really produce jobs: “At that point…you’re starting to employ hyper-local residents. You can introduce food (for) the under-served community. The idea here is, if we scale this up to the inner-city to provide them local jobs…”.

However, Harris recognizes that the indoor vertical farming has its limitations. “So, you’re not going to grow wheat, corn, barley…this is not an apple orchard…but there are lots of field crops that are grown in muck farms or other soil environments that are not necessarily optimal for the environment. You could bring those in to hyper-local. Because they’re typically consumed hyper-local.”

This Urban Farming Accelerator Wants To Let Thousands Of New Farms Bloom

08.23.17

This Urban Farming Accelerator Wants To Let Thousands Of New Farms Bloom

Kimbal Musk’s Square Roots is giving aspiring urban farmers their own shipping containers and helping them sprout a new business, in the hopes of creating a new agricultural system.

“We are successful if the farmers are successful. So we wake up every morning thinking: how can we help the farmers be more successful?” [Photo: courtesy Square Roots]

In a parking lot outside a former pharmaceutical factory in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant, 10 entrepreneurs have spent the last nine and a half months learning how to take on the industrial food system through urban farming. Square Roots–a vertical farming accelerator co-founded by Kimbal Musk, with a campus of climate-controlled farms in shipping containers–is getting ready to graduate its first class.

With a new round of $5 million in seed funding, led by the Collaborative Fund, the accelerator is making plans to build new, larger campuses in other cities.

“Is it going to be one company that takes down the industrial food system, or is it going to be thousands of companies working together on a better food system?” [Photo: courtesy Square Roots]

In the program, each entrepreneur is temporarily given a single upgraded shipping container, filled with vertical growing towers, irrigation systems, and red and blue LED lights in a spectrum tuned to help grow greens. Then they spend roughly a year learning the skills to grow food–no prior experience is necessary–developing business plans and working with coaches and experts to improve their entrepreneurial skills. By the end, in theory, they’ll be ready to launch an urban farming business of their own.

Musk, who runs several health-focused restaurants and nonprofit school gardens (and is Elon’s brother), saw the need for a large network of well-trained young entrepreneurs who could quickly grow urban farming. “We wanted to come up with a model that scaled small urban farming, so literally every consumer of food can have a direct relationship with a farmer,” says Square Roots co-founder and CEO Tobias Peggs.

“We wanted to come up with a model that scaled small urban farming, so literally every consumer of food can have a direct relationship with a farmer.” [Photo: courtesy Square Roots]

“Is it going to be one company that takes down the industrial food system, or is it going to be thousands of companies working together on a better food system? We definitely believe the latter,” he says. “So part of the engine that we’ve created here is that by training these young people…at the end of that program, they’re armed with the tools that they need to go out and set up their own food business. The hope is there will be tens of thousands of new businesses that end up being formed.” The program offers mentorship and can help connect entrepreneurs to investors.

In a learn-by-doing model, everyone immediately starts farming. “When this first cohort joined on November 7, on that day, literally the farms were dropped from a truck onto the parking lot,” Peggs says. “Eight weeks later, we had our first farmers market in Bed-Stuy, where those people had learned to grow really tasty food. The whole system is kind of geared up to have a very fast learning curve.”

I think it’s important to expose people to urban farmers.” [Photo: courtesy Square Roots]

As they grow and sell greens during the program, the entrepreneurs make money; the accelerator keeps a portion of the profits to fund itself. “Our incentives are aligned,” he says. “We are successful if the farmers are successful. So we wake up every morning thinking: how can we help the farmers be more successful?” Even with a single shipping container farm, Peggs says that it’s possible to run a profitable business.

One pair of entrepreneurs worked together to launch a farm-to-desk delivery program that brings fresh greens to dozens of New York City offices. Another student is focused on growing greens for low-income neighborhoods. Someone else launched a business delivering produce to New Jersey while running her Square Roots farm. A former engineer is developing an improved lighting system for indoor farming and plans to launch an equipment business. Another entrepreneur used data analysis to perfect a growing recipe for heirloom basil, which he sells to restaurants and markets. (The accelerator’s layout, with modular growing containers, also allows it to study data about yield and quality and improve the technology for future students).

“What I found most valuable is you’re pretty much thrown into operating a business, and you learn as you go.”[Photo: courtesy Square Roots]

“The way that I learn is through experience and also through imitation,” says Nabeela Lakhani, one of the first class of entrepreneurs, who joined the accelerator after graduating from a public health and nutrition program. She had no prior farming experience. “What I found most valuable is you’re pretty much thrown into operating a business, and you learn as you go, which was perfect for me.”

Lakhani partnered with a SoHo restaurant, Chalk Point Kitchen, to become its “official farmer,” growing food on demand for the chef. The restaurant buys her entire yield from the shipping container, and Lakhani provides a year-round supply of produce. She also visits the restaurant once a week to wander around tables talking with customers.

[Photo: courtesy Square Roots]

“I think it’s important to expose people to urban farmers,” she says. “You should be friends with your farmer–that’s how local food should be. Just the way the chef comes out and says hi, I think it should be the norm that the farmer comes out and says hi. That builds trust between the consumer and the food system.”

The first cohort will graduate in October, and the accelerator is taking applications for its next class; in 2016, it had 500 applicants for 10 spots. In its new location in a yet-to-be announced city, it plans to have larger campuses with room for more students. The founders also hope to quickly launch in more locations. “It’s all stemming from the mission of real food for everyone,” says Peggs. “Ultimately, we want to put a Square Roots campus in every city in the U.S.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Adele Peters is a staff writer at Fast Company who focuses on solutions to some of the world's largest problems, from climate change to homelessness. Previously, she worked with GOOD, BioLite, and the Sustainable Products and Solutions program at UC Berkeley.

Future Farm To Double Size and Ramp Up Baltimore Vertical Farming Project With Second Location

SOURCE: Future Farm Technologies, Inc. | August 24, 2017 08:00 ET

Future Farm To Double Size and Ramp Up Baltimore Vertical Farming Project With Second Location

VANCOUVER, BC--(Marketwired - Aug 24, 2017) - Future Farm Technologies Inc. (the "Company" or "Future Farm") (CSE: FFT) (OTCQB: FFRMF) announces an update with respect to its Baltimore farm. As previously announced, Future Farm signed a LOI to lease 25,000-sq ft of commercial space from Volunteers of America ("VOA") Chesapeake to accommodate a vertical farm in Baltimore, MD, which will distribute high value healthy produce to local area retail stores, restaurants, institutional non-profits and other buyers. The Company is pleased to announce that the facility's design and budget are now complete and a second location will double the size of the project to almost 50,000-sq ft and speed up the development.

The Company expects to gain site control of the second location in Baltimore within the next 7-10 days. This particular site is more accommodating to the Company's controlled environment agriculture ("CEA") technology requirements and requires less construction build-out. It is expected that this second location will be operational sooner than the original location and will therefore become Phase 1 of the Baltimore project.

As previously announced, Craig Stanley and CBO Financial will act as the Company's financial advisor with respect to New Market Tax Credits (NMTC) and will be arranging for $5,000,000 in NMTC-based financing for each phase of the Baltimore farms. The NMTC program is a $65 billion federal program designed to incentivize private investment in low-income communities. NMTCs are provided to financial institutions in exchange for equity investments that eligible businesses can use to subsidize project development costs. CBO Financial helps driven organizations, such as Future Farm, to finance facilities that will provide goods and services that benefit populations in need and revitalize communities.

"We are pleased to be working with CBO Financial and Volunteers of America Chesapeake on these projects and believe that their success will be a bellwether for public-private partnerships within the urban farming industry," says Mr. William Gildea, Future Farm's CEO and Chairman. "Our goal was always to create impactful social and corporate programs that are mutually beneficial for all involved, from the community, to the Company and our shareholders. Partnering with Volunteers of America and CBO Financial puts us in the position to achieve that goal."

"This approach to urban agriculture and community development is truly visionary and we are proud to be involved with such a meaningful project," says Tony Azola, General Contractor for Volunteers of America.

The primary objectives of both farms remain the same -- establish economical and environmentally friendly vertical farms; provide job training opportunities (specifically to the VOA's reentry program for ex-offenders in Baltimore, MD) as well as to the local community; provide therapeutic programs, which will be expanded to the disabled population; support entrepreneurship development; and establish a model for replication at other reentry and social services facilities.

One of the primary objectives of the projects is to provide opportunities to develop therapeutic programs involving all aspects of planting, growing/nurturing, harvesting and selling plants. The American Horticultural Therapy Association (AHTA) defines "Horticultural Therapy" as the "engagement of a person in gardening and plant-based activities, facilitated by a trained therapist, to achieve specific therapeutic treatment goals." AHTA believes that Horticultural Therapy (HT) is an active process, which occurs in the context of an established treatment plan where the process itself is considered the therapeutic activity rather than the end product. The therapeutic benefits of garden environments have been documented since ancient times. Today, HT is accepted as a beneficial and effective therapeutic modality and is widely used within a broad range of rehabilitative, vocational, and community settings. HT helps improve memory, cognitive abilities, task initiation, language skills, and socialization. In physical rehabilitation, HT can help strengthen muscles and improve coordination, balance, and endurance. In vocational HT settings, people learn to work independently, problem solve, and follow directions.

For further information, contact William Gildea, Director, at 617.834.9467.

On behalf of the Board,

Future Farm Technologies Inc.

William Gildea, CEO & Chairman

About Future Farm

The Company's business model includes developing and acquiring technologies that will position it as a leader in the evolution of Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) for the global production of various types of plants. Future Farm provides scalable, indoor CEA systems that utilize minimal land, water and energy regardless of climate, location or time of year and are customized to grow an abundance of crops close to consumers, therefore minimizing food miles and its impact to the environment. The Company holds an exclusive, worldwide license to use a patented vertical farming technology that, when compared to traditional plant production methods, generate yields up to 10 times greater per square foot of land. The contained system provides many other benefits including seed to sale security, scalability, consistency due to year-round production, cost control, product safety and purity by eliminating environmental variability.

The Company is also in the business of designing and distributing LED lighting solutions utilizing the COB and MCOB technology. The Company is focused on delivering cost efficient lighting to North America via advanced e-commerce sites the Company owns and operates. LEDCanada.com which caters to B2B customers is a supplier of the newest and highest demand LED solutions. The Company also owns and operates COBGrowlights.com which caters to both large and small agriculture green houses and controlled cultivation centers.

Neither the Canadian Securities Exchange nor its Market Regulator (as that term is defined in the policies of the Canadian Securities Exchange) accepts responsibility for the adequacy or accuracy of this release. The Canadian Securities Exchange has not in any way passed upon the merits of the proposed transaction and has neither approved nor disapproved the contents of this press release.

This news release may include forward-looking statements that are subject to risks and uncertainties. All statements within, other than statements of historical fact, are to be considered forward looking. Although the Company believes the expectations expressed in such forward-looking statements are based on reasonable assumptions, such statements are not guarantees of future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those in forward-looking statements. Factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from those in forward-looking statements include market prices, exploitation and exploration successes, continued availability of capital and financing, and general economic, market or business conditions. There can be no assurances that such statements will prove accurate and, therefore, readers are advised to rely on their own evaluation of such uncertainties. We do not assume any obligation to update any forward-looking statements except as required under the applicable laws.

CONTACT INFORMATION

William Gildea

CEO & Chairman

617-834-9467

bill@futurefarmtech.com

Up On The Farm: Ambitious Urban Agriculture In The City’s Hilltop

Up On The Farm: Ambitious Urban Agriculture In The City’s Hilltop

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette | AUG 27, 2017

Eight years ago, the remaining residents of St. Clair Village were mourning the loss of their homes, which the Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh had decided to demolish. Now, in a transformation that may be symbolic of the new Pittsburgh, the neighborhood is being reborn as the Hilltop Urban Farm.

No one should minimize the loss and the controversy that accompanied the closing of the apartment complex that once housed 1,000 families. In 2005, the authority razed more than half of the units, and the remaining units were in a state of disrepair. The authority decided to close the community, citing a study that indicated it would cost $27 million to upgrade and maintain the buildings. Residents were displaced, and the supply of affordable housing was reduced.

Now 23 acres of the site are in the early stages of becoming one of the largest urban farms in the country. The nonprofit Hilltop Alliance, with many partners, is spearheading the plan that includes community-supported agriculture, an orchard, a farm market, an education center, greenhouses, storm-water ponds, and community garden plots.

The Hilltop Alliance has conducted a careful planning process lasting more than four years. It involved feasibility work by agriculture experts at Penn State University and discussions with community members. Churches and youth-serving organizations have expressed hope that the development will give neighborhood youth a positive outlet for their energy and a way to earn some money.

Across the nation, urban agriculture is on the rise, with attendant challenges. While Detroit has made great strides, there has been controversy about the proper use of land that is near public transportation and which may be appropriate for housing. Pittsburgh seems to be avoiding these problems, since city council passed an urban agriculture ordinance in 2011 and has monitored progress since then.

The preparation of the soil at the Hilltop Urban Farm has begun, and an abandoned property will literally bear fruit in the coming years.

The Hilltop Urban Farm Report

Best Viewed In Full Screen

Solar-Powered Bike Sharing Farm Is A Mobile Community Garden For The City (Video)

Bike Share Farm has been made with mobility in mind. Using off-the-shelf components, a portable hydroponic system with a series of zigzagging tubes forms a frame into which two different bikes can be slotted as the mobile garden travels from place to place. The hydroponic system's irrigation mechanisms are powered by a series of photovoltaic panels.

Solar-Powered Bike Sharing Farm Is A Mobile Community Garden For The City (Video)

Kimberley Mok (@kimberleymok)

Design / Urban Design

August 17, 2017

© People’s Industrial Design Office

Our long love for the bicycle extends beyond the two-wheeler itself, spilling over into bike-powered inventions, electricity-generating gyms, even whole buildings designed around the bike.

Seen over at Designboom and created by the People’s Industrial Design Office -- the design arm of Beijing firm People’s Architecture Office -- during a three-day design hackathon in Seoul, South Korea, the Bike Share Farm is a solar-powered and bike-propelled mobile hydroponic garden, inspired by the bike sharing concept. The idea was to bring plant life to the citizenry, the designers say:

Seoul is a massive vertical city with minimal garden space. Mobile farms can make shared urban farming possible in such a dense megacity.

Bike Share Farm has been made with mobility in mind. Using off-the-shelf components, a portable hydroponic system with a series of zigzagging tubes forms a frame into which two different bikes can be slotted as the mobile garden travels from place to place. The hydroponic system's irrigation mechanisms are powered by a series of photovoltaic panels.

The Bike Share Farm is a prototype attempts to tackle the issues highlighted during the hackathon of how to "[share an] eco-city with technology." While there may be finer details to work out (such as factoring in how long it will take the plants to mature before harvesting), one could almost imagine a mobile garden like this bringing 'instant' fresh green produce to food deserts or neighbourhoods lacking community gardens. An intriguing idea as well as a powerful symbol of food security and human-powered mobility; see more over at People’s Industrial Design Office.

Hippie Amenities With a High-End Twist

Hippie Amenities With a High-End Twist

By KIM VELSEYAUG. 18, 2017

Garden construction in progress on the eighth floor deck of 550 Vanderbilt in Brooklyn. CreditEmon Hassan for The New York Times

As dusk fell over Staten Island on a recent evening, about 10 people sat around a large wooden table in a communal kitchen, listening to Van Morrison and painting terra-cotta flowerpots. Houseplants were suspended from the room’s high wood-beamed ceilings, and the smell of freshly baked bread hung in the air.

A hippie house share? Not quite. It was crafts and cocktails night at Urby Staten Island, an upscale rental complex where the demographic skews more young professional than drum-circle enthusiast. Nonetheless, the complex has features that might make that crowd feel right at home: In addition to the communal kitchen, there’s a 5,000-square-foot urban farm, a 20-hive apiary — both tended by live-in farmers/beekeepers — and a kombucha workshop planned for later this summer.

“Live cultures are really something people are responding to,” said Brendan Costello, the complex’s in-residence chef, as he wiped the last of the bread crumbs and black maple butter from the countertops. He has already taught well-attended workshops on making sauerkraut and kimchi.

Just as Birkenstocks and bee pollen have come back in style, so have crunchy lifestyle concepts, from yoga and meditation to composting and home fermentation. And with veganism, Waldorf schools, doulas and healing crystals shifting from far out to very much in fashion, a growing number of New York luxury buildings have embraced the hallmarks of 1970s hippiedom with a high-end twist. Look for amenities like rooftop gardens, kitchen composters, art and meditation studios, bike shares, infrared saunas, even an adult treehouse.

“Especially in Brooklyn, the concrete jungle is not the atmosphere people are aiming for,” said Ashley Cotton, an executive vice president of Forest City New York, whose recently opened condo in Prospect Heights, 550 Vanderbilt, developed in partnership with Greenland USA, has window planters for units on lower floors and a communal garden terrace with individual plots on the eighth floor. Two of the terrace’s six large planters will be tended by a nearby farm-to-table restaurant, Olmsted, which will also offer gardening lessons to residents.

At Pierhouse, the Toll Brothers City Living condo in Brooklyn Bridge Park in Brooklyn, every kitchen has an in-unit composter, a first for a Toll Brothers development.

Residents of URBY in Staten Island visit a farmstand set up by Empress Green in Urby’s communal kitchen. CreditEmon Hassan for The New York Times

“If we were deciding between a compost unit and a wine chiller, we’d probably go with the wine chiller since more people would be interested,” said David von Spreckelsen, the president of Toll Brothers City Living division. “But here we had large kitchens and a lot of the units have outdoor space, so we thought people could compost in their kitchen and go right out to their garden.”

While such amenities might be aspirational for some, others are yearning to get their hands dirty. Christine Blackburn, an associate broker at Compass real estate, said that for a woman to whom she recently sold a condo at 144 North Eighth Street in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, the roof garden was the most important amenity.

“She didn’t care about the gym, she didn’t care about the garage,” Ms. Blackburn said. “They live in a $2 million condo, but for her to be able to grow tomatoes with her son, that was it.

“The garden plots in that building are tiny,” she added, “but it makes some people feel like they’re not living in a high-rise.”

Public green space has always been a priority, of course, and let’s not forget that large swaths of all five boroughs were once farmland.

Green rooftops have some historical antecedents in the city: The Ansonia, on the Upper West Side, kept 500 chickens on its rooftop farm in the early 20th century, with eggs delivered daily to the tenants, according to “The Sky’s the Limit,” a book by Steven Gaines. But the roof was shut down by the Department of Health after just a few years, in 1907. And for the past century, it was accepted that living in New York meant leaving nature, and local honey, behind.

“It definitely used to be an either/or mentality,” said Rick Cook, a founder of the architecture firm CookFox and a designer of 550 Vanderbilt, who moved to New York from a small town upstate in 1983. But after studying abroad in Florence, Italy, he said, “I understand you could have both. That, in fact, the highest quality of life is to have both.”

Indeed, the explosion of the wellness industry has left many craving a different kind of New York lifestyle.

For a younger generation, practices like organic gardening and meditation may not carry any whiff of the counterculture.

“Being green is modern, being organic is modern,” said Jordan Horowitz, 26, an assistant manager of Enterprise Rent-a-Car who grew up gardening in suburban New Jersey and was excited to get a studio at Urby, where residents have an entire city block of gardens. But he is equally enthusiastic about the pool, the giant bean bags strewn across the grounds and learning to make Vietnamese cuisine from scratch in Mr. Costello’s cooking classes.

That many such offerings tend to be far more upscale than their 1970s counterparts no doubt helps to remove any lingering hippie vibe. Rather than a stable of rusty Schwinns, for example, 50 West, in the financial district, allows residents to pedal out on Porsche bikes that cost $3,700 a pop.

“Yes, it’s sharing, but in a luxury manner,” said Javier Lattanzio, the sales manager at the condo.

Javier and Irina Lattanzio, residents and brokers of 50 West in Lower Manhattan, take a spin on Porsche bikes provided by the building.CreditSasha Maslov for The New York Times

The adult treehouse at One Manhattan Square on the Lower East Side, likewise, is hardly primitive, with Wi-Fi and a staircase. As for all those rooftop herb gardens, asked if they are actually used, one broker replied that they definitely were, though not necessarily for a Moosewood recipe: On a recent trip to 338 Berry in Williamsburg, she saw people with Aperol spritzes clipping herbs to put in their cocktails.

Frank Monterisi, a senior vice president of the Related Companies, emphasized that the new generation of renters and buyers “like to see sustainability, they like to see rooftop gardens.”

At Hunter’s Point South, Related’s massive affordable housing complex in Long Island City, Queens, residents can receive deliveries of fresh vegetables from a C.S.A. — community-supported agriculture. There are also an apiary, about 2,300 square feet of rooftop gardens and a waiting list for the gardening club.

“Everyone wants to garden now. I think New Yorkers have gotten comfortable with the amount of concrete we have, but they also want to see green,” said Joyce Artis, a retired Port Authority worker who helps organize the gardening program at the complex and grows microgreens and lemon trees in her apartment.

Ms. Artis said that when she was growing up in Brooklyn, she was sent to visit relatives in North Carolina in the summer, and hated having to get up early to weed. “But then as I got older, I started missing it,” she said. “And I started growing things in my apartment. No matter how small your space I always say: ‘You can grow one thing.’”

Ms. Blackburn, the Compass broker, said that gardening, for some, is a version of meditation. “Maybe they’re not sitting there with a meditation app, but sticking their hands in the soil — it doesn’t matter if someone’s making $10 million a year — it can be very therapeutic.”

She expects the enthusiasm to continue and intensify. “I wouldn’t be surprised in a year if a luxury building had a chicken coop,” she said.

Glasgow’s Community Gardens: Sustainable Communities of Care

Glasgow’s Community Gardens: Sustainable Communities of Care

Community gardens are not yet embedded in place or institutions – their immediate future is precarious in many cases.

Dr John Crossan

Professor Deirdre Shaw

Professor Andrew Cumbers

Professor Robert McMaste

University of Glasgow 2015

Excerpt:

The potential for community gardening is high in old industrial cities where the loss of manufacturing industry has resulted in vast areas of unused spaces. Glasgow is a particularly pertinent case with 1300 hectares of vacant and derelict land, representing 4% of its total land area and comprising 925 individual sites. As a result over 60% of Glasgow City’s population lives within 500 metres, and over 90% within 1000 metres, of a derelict site. This is important when considering issues of social and environmental justice, as most of the vacant and derelict land can be found in the most deprived areas of the city, thus, disproportionately affecting the poorest citizens (see Map 1).