Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

How Can New York Meet the Challenges of Urban Agriculture?

How Can New York Meet the Challenges of Urban Agriculture?

SEPTEMBER 21, 2017 LOUISA BURWOOD-TAYLOR

On the final day of AgTech Week in New York City, a panel of local experts got together to think about how the city can embrace, promote and foster urban agriculture.

New York is one of the leading cities in the US for urban agriculture, with a plethora of initiatives from hobby community gardens to commercial rooftop farms to high-tech indoor vertical farms. But there is still a long way to go until the city provides wannabe urban growers with the support they need to make locally grown produce a permanent and significant part of the city’s food supply.

Before the panel commenced, Henry Gordon-Smith, a celebrity in New York’s urban agriculture scene and founder of consultancy and content businesses Agritecture and Blue Planet Consulting (now Agritecture Consulting), set the scene by offering some insights into how other cities in the world make a success of their urban agriculture initiatives.

In Cuba, for example, 3.2 tonnes of organic food was grown in urban farms in 2002. Individuals are incentivized economically to grow food, but there are also rules around what they can grow in each location, depending on what else is being grown nearby to ensure diversity in the food supply.

Japan’s weekend farming program brings families out of the city and into the surrounding countryside to help grow food, connecting them with the source of their food and providing them some often needed respite from city life. There are also programs to get their help at indoor grow operations too.

And in Canada, urban farmer Curtis Stone has borrowed or rented unused land to produce food at scale, making the most of untapped resources in the city, and rules around vacant real estate lots.

“How can we have our own brand and approach to urban agriculture in New York City?” he asked the audience.

What are the main challenges for urban agriculture in New York and what can the city do to alleviate them

1. Access to Land and Space

This can be a real inhibitor at the early days of a project, but also when the operator wants to scale, moving from 1,000 sq ft to 10,000 sq ft is very difficult, said Gordon-Smith.

The difficulties mainly lie in permitting and the delays inherent in the system. There is also lack of available information about the availability of space for urban farms.

Gordon-Smith and Tatiana Pawlowski, a law clerk at Braverman Greenspan and expert in zoning laws, blamed permitting challenges to a lack of understanding in the department of buildings about urban agriculture. “The department does not know how to handle an application for an urban farm. The zoning code itself is very hard to read and it’s very long. It hasn’t been updated since 1962 and the phrase urban agriculture doesn’t exist! There is some brief talk about raised truck beds and community gardens, but the law is very silent on what exactly can and can’t be done.”

Gordon-Smith added: “There is a lot of interpretation of code needed before permits can be awarded, but for operations, timing is critical to get investment as investors won’t support a project if you can’t secure a space.”

There is also a lack of concrete, and available data and information about where vacant spaces might be and how they’re utilized, or not.

“People might not know that technically farming is allowed in commercial and industrial districts,” Pawlowski said.

What Can NYC Do?

Create a well-organized, centralized place for all data and information about finding and securing space in New York that’s readily accessible.

“Modernize and organize the information available so it’s readily accessible for urban farmers, particularly small-scale scale community residents,” said Tatiana.

None of the panelists suggested this outright, but it sounds like the city could do with updating its zoning laws too!

Rafael Espinal, council member for Bushwick and East New York, agreed that urban farming initiatives were struggling to get seed funding they need because investors are afraid to invest in a city which has “not yet taken a leading role in recognizing the work that’s being done in this area.” He added that he has introduced a bill to “force the city to sit down and take a year to figure out what challenges we’re seeing for urban agriculture in terms of zoning or incentives as the city must get engaged at that level.”

2. Access to Basic Talent

Finding entry level talent, with some training in food safety and other relevant skills, is very challenging, according to all the panel members. It also represents a significant portion of an urban operation’s cost base.

What Can NYC Do?

Gordon Smith suggested that the city could develop a training program to help develop a diverse skillset among potential workers to strengthen the urban ag industry, but that there might need to be a financial incentive attached to it, particularly as labor is one of the leading operational costs of urban farming.

Alex Highstein, corporate development at AeroFarms, which is based in New Jersey, said New Jersey has some initiatives like this. “We work with the New Jersey Economic Development Authority. They have a program called Grow NJ which gives us tax incentives for hiring, and we’re also working with the city of Newark to source labor from fantastic places like the veterans program, and the re-entry program. They help train them, particularly where there are big gaps in knowledge such as around food safety.”

3. Lack of Awareness About Benefits of Local Food

Governments do not put local food first, which limits the ability to promote urban agriculture among the population to bring new talent and expertise to the sector.

Highstein agreed that people in New York “often lack a connection to what they’re eating; if we could spread the idea that this food was grown the next street over, those people would value their food more.”

What Can NYC Do?

Work with industry, incubators, and farms to spread those ideas around the importance and value of locally grown food.

“We need more carrot to get groups involved and excited about promoting urban agriculture to help it accelerate,” said Gordon-Smith.

4. Energy Costs and Carbon Footprint

There is a certain amount of resistance to indoor farming from some quarters of the city, namely around the high use of electricity to light and heat indoor farming facilities, and therefore the potential for added pollution. Developments in LED lighting are aiming to increase efficiency, but it’s a significant cost-base, economically and carbon emissions-wise.

Council member Espinal said: “We get lots of emails from people who are against expanding urban ag as they say it will require more power and create more plumes. There is not enough green energy produced, pushing reactors to create more power to feed indoor farm lighting.”

What Can NYC Do?

“We need to continue pushing for ’80×50′, which is a New York pledge to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050,” said Espinal. “But to do this the city needs to change the grids to accept solar and wind energy.”

Highstein also suggested incorporating hydroelectrical energy.

Panelists argued that protesters also need to be better educated about the environmental benefits of urban agriculture, something the local government could help with.

“People forget about the benefits of outdoor rooftop farming and the amazing effect it has on mitigating the heat island effect, where black tar rooftops create heat, requiring more energy to cool buildings down,” said Pawlowski. A green roof can bring temperatures down by a couple of degrees, which is significant, and not only fits with the 80×50 plan but is also good for air quality.”

Harrison Hillier, hydroponics manager at Teens For Food Justice said that just looking at energy consumption was only part of the broader picture, pointing to the food security indoor operations can bring in the face of natural disasters, and the reduction in the use of harmful chemicals and pollutants causing negative ecological impacts across the country.

Food Pioneers Regenerate Cities

Urban Organics opened the doors of its first aquaponics farm, built inside an old Minnesota brewery, in 2014. The venture was backed by global water firm Pentair, which fitted out the Hamm’s Brewery site with an innovative water filtration system and industry leading reuse technologies

Food Pioneers Regenerate Cities

Staff reporter | 15th September 2017

An urban food pioneer is transforming abandoned buildings in Minnesota into breeding grounds for sustainable fish and organic greens.

Urban Organics opened the doors of its first aquaponics farm, built inside an old Minnesota brewery, in 2014. The venture was backed by global water firm Pentair, which fitted out the Hamm’s Brewery site with an innovative water filtration system and industry leading reuse technologies. And the pair have built on that relationship with the regeneration of Minnesota’s Schmidt brewery, which will be able to supply ‘275,000 lbs. of fresh fish and 475,000 lbs. of produce per year to the surrounding region’ this year. The ‘USDA-certified-organic farm’ extends Urban Organics reach as it begins to expand a business with tech that could have a global impact.

“We started this venture as social entrepreneurs who wanted to figure out how to bring a reliable source of healthy foods into areas that had to rely on food transported in from far away,” explained Dave Haider, co-founder of Urban Organics. “It turned out that our wild idea also made a lot of sense to a community hungry for organic, sustainably-raised food, and to other innovators around the world who had been asking the same questions we were. By collaborating with Pentair, we’re able to contribute beyond our immediate region—we’re able to test and perfect the technologies that will make a global impact advancing the field of large-scale commercial aquaponics.”

Farming in the city is a growing trend. By 2022 it is estimated the vertical farming market will be worth more than $6 billion. And America is leading the way. Aero Farms is making progress with its vision to combat the ‘global food crisis with technology’. While an urban food accelerator in the heart of New York, Square Roots, led by entrepreneur Kimbal Musk, is helping innovators take forward their ideas for developing indoor farming businesses – inside shipping containers located in Brooklyn.

The Farms Of The Future Are Here – But There's A Catch

This new type of farming, dubbed "urban farming," requires significantly less acreage and energy. Simply put, urban farms grow or produce food in a city or heavily populated area using unorthodox methods.

The Farms Of The Future Are Here – But There's A Catch

By CASEY WILSON, Associate Editor, Money Morning • September 21, 2017

The farms of the future use absolutely no soil and 95% less water.

Yes, you read that right. No soil – at all.

This new type of farming, dubbed "urban farming," requires significantly less acreage and energy. Simply put, urban farms grow or produce food in a city or heavily populated area using unorthodox methods.

Urban farming takes many forms, using many different methods. Some urban farms are strictly vertical farms, which means the plants grow upright on walls. Some are aeroponic, which means the plants grow in an air or mist environment.

Urban farms are so efficient, just half an acre can yield the same (and in some cases, more) harvest than over 10 acres of traditional farmland.

No wonder these urban farms are sprouting up all over the country. There's at least one urban farm in almost every major city today. In some cities, like New York City, there are more than 20.

But here's the downside…

Urban farming isn't something average investors and traders can directly invest in, and likely won't be for a while.

You see, most urban farming ventures get their funding from venture capitalists. For example, AeroFarms Corp., one of the largest urban vertical farming companies, just secured $20 million for its latest indoor farm all from one round of venture funding.

And the company has not made any plans to go public as of yet. Instead, the company is planning to work with Goldman Sachs Group Inc. (NYSE: GS) and Prudential Financial Inc. (NYSE: PRU) to raise more than $70 million over the next five years in order to build 25 new farms – a 177% increase from the 14 farms it has now.

Still, there's a way for investors to profit from this burgeoning technology. Check out the video below…

Green City Growers Honored Globally, Nationally And Locally With Five Awards

Green City Growers Honored Globally, Nationally And Locally With Five Awards

PR Newswire

Sep. 18, 2017, 05:19 PM

BOSTON, Sept. 18, 2017 /PRNewswire/ -- Green City Growers (GCG) received five awards within one week in recognition of the company's success in its mission of transforming unused space into thriving urban farms, providing a variety of clients with immediate access to nutritious food, while revitalizing city landscapes and inspiring self-sufficiency.

"In nine years of operating, we have grown 175,000+ pounds of organic produce and engaged over 7,500 people, on less than two acres of space combined," says Jessie Banhazl, CEO and Founder of GCG. "To have this work recognized is incredibly heartening for everyone at Green City Growers."

GCG, a Certified B Corporation, has been included on B Lab's Best for the Environment and Best for the World Overall list for 2017, earning scores in the top 10 percent of more than 2,100 Certified B Corporations on the B Impact Assessment. The total 176 honoree companies come from 75 industries and 25 countries.

On September 15, GCG received the Walden Woods Project's Environmental Challenge Award in honor of Fenway Farms and the partnership with Linda Henry and the Red Sox. Sited within Fenway Park, the farm produces 6,000 pounds of organically grown produce each season. Previous award recipients include President Bill Clinton and Robert Redford. The award was presented by Don Henley of the Eagles, Walden Woods Project founder, at the Global Environmental Leadership Award Dinner.

Lastly, Scout Somerville named GCG Best Eco-Friendly Business and Best Landscaping Company in its September/October edition. GCG hosts the Urban Ag. Ambassador program for the City of Somerville, in addition to maintaining farming sites throughout the Greater Boston area.

Green City Growers, the premier urban farming company in the northeast, envisions a world where rooftops and vacant lots become common and productive places to grow food – an agricultural revolution for a healthier nation. GCG works with corporate clients, retailers, property management companies and residential properties to install and maintain attractive edible landscapes. Farming sites range from small residential and commercial locations, to in-ground production farms, to the rooftop farms at Whole Foods Lynnfield and at Fenway Park, Fenway Farms.

www.greencitygrowers.com

Modern Farmers: Modern Farmers: The Future of Farming Is Sprouting Up Where You'd Least Expect It

It's not just a potential antidote to the unsustainable machine of industrial agriculture. It's also a new frontier for the culinary world, and you're about to reap the benefits.

Go Inside the Farms | Photo: Bowery

Beneath one of NYC's best restaurants, down a hallway you could find only if you knew where to go, rows of heady, hydroponic herbs, sticky with residue, grow under LED lights. Across the East River, in an old factory, a small lab of growers tinker with their own seedlings, while a greenhouse just two miles away grows its own special line of potent plants.

No, we're not talking about weed—although in many ways, the, ahem, budding industry helped pave the way here. We're describing the field of indoor farming, much of it hydroponic, catering to home cooks and restaurant chefs, that's growing at an incredible clip around the country. And it's booming where you'd least expect it: none other than New York City.

It's not just a potential antidote to the unsustainable machine of industrial agriculture. It's also a new frontier for the culinary world, and you're about to reap the benefits.

Just ask Tom Colicchio, an investor in Bowery Farming, a seven-month-old hydroponic vertical farm, which just recently started selling greens to tristate area Whole Foods. The chef calls the company the "new paradigm for farming," one that he's "really excited about." At his new Downtown NYC restaurant, Temple Court (previously Fowler & Wells), the Top Chef judge garnishes crudo with Bowery's wasabi arugula—a spicy green bursting with flavor. Or ask Claus Meyer, an adviser at Brooklyn Navy Yard-based start-up Farmshelf, or Alex Guarnaschelli, who sources from newcomer Farm.One, which has spaces at the Institute of Culinary Education and underneath the restaurant Atera in Tribeca. Each one of these chefs is a champion for the undeniable advantage of indoor farming: fresh, unique and local produce available all year round.

Andrew Whitcomb, executive chef at Norman | Photo: Farmshelf

Exact methods vary, but generally speaking, hydroponic farms grow greens, herbs and flowers in soilless containers under LED lights in highly controlled climates. That means 365 days of ideal growing conditions, with efficient water use and minimal waste. They're also often stacked vertically, which cuts down on the need for square footage. Some farms, like Edenworks in Brooklyn, use fish and aquatic life to feed their ecosystems, while others, like AeroFarms, don't use hydroponics at all but rely on a specifically crafted aeroponic mist.

It might sound unnatural, but these farms are actually growing their goods without the use of herbicides or pesticides. Bowery cofounder Irving Fain implores skeptics to rethink what organic really means, pointing out that "organic standards were written at a time when a lot of the technology we have access to today didn't even exist."

And then there's the magic word: local. These indoor farms are able to grow and sell within mere miles of the restaurants or homes to which they're catering, no matter the season.

As Great Northern Food Hall's Jonas Boelt—who works with Farmshelf—explains, "Back in Denmark, my team and I would go forage for ingredients daily. As that is impossible in New York City, harvesting Farmshelf herbs is the next best thing."

When you look at it this way, it makes sense that NYC and the surrounding area, against all odds, has become a major hub for ag tech. The high demand from the most competitive dining scene in the country, coupled with the short growing season, actually makes for quite fertile ground. Add to that the great public transportation, Farm.One CEO Robert Laing points out, and distribution becomes even more sustainable.

Though the space may seem crowded, every company has a distinct mission. AeroFarms and Edenworks focus on large-scale production, boxing greens to sell at the supermarket. Bowery does the same but also works with Colicchio to expand its culinary partnerships.

Farmshelf builds units to put into restaurants—like the Great Northern Food Hall and Brooklyn's Norman—hotels, corporate cafeterias and eventually home kitchens, "putting the technology into the hands of the consumer and bringing the farm right into the building," as cofounder/CRO Jean-Paul Kyrillos says.

Unique greens growing at Farm.One in TriBeCa | Photo: Farm.One

Then there's Farm.One, which focuses on providing restaurants with rare and fresh ingredients, selling to some of the hottest spots in NYC. Think Mission Chinese, Daniel, Atera, Pizza Loves Emily, Le Turtle, Locanda Verde, The Pool and The Grill.

"In general, they're buying things that are normally the last thing that a chef puts on the plate and the first thing the customer sees," Laing says of a list of herbs and flowers that may be unrecognizable to even the proudest foodie. Multiple kinds of sorrel and basil are just the beginning. (Pizza Loves Emily is fond of the Pluto basil, while the blue spice basil's vanilla notes would compliment any dessert.) There's also papalo, a limey herb from Central Mexico that's great for cutting the fat on rich dishes, as well as medicinal-tasting yarrow and sweet anise hyssop. Farm.One even grows something called cheese plant, which tastes just as funky as it sounds.

Beyond the accessibility to fresh or rare plants—and the intense flavor that comes along with them—another culinary win for these farms is that they guarantee chefs a certain amount of predictability and control, Boelt points out. Among the many reasons chef Tim Hollingsworth of L.A.'s Otium values his vertical garden—albeit an outdoor one—is for the control it gives him over a plant's different growing phases. For example, he can use nasturtium flowers one week or harvest them early for their capers another week.

With so many culinary perks, it's no wonder that the ag tech industry is taking off, with ambitious chefs going all in. Whether you're dining out or cooking at home, the variety of fresh and local produce is only going to get better as these farms grow, elevating the possibilities for your plate and palate—and making the watered-down, mass-harvested produce you're used to tasting even more bland. "I can't even buy herbs from the supermarket anymore," Laing says. You're next.

This month, join us as we go all in on Peak Season, taking full advantage of the bumper crop of cozy recipes, market ingredients, wine trends and entertaining gear to help you live your best fall.

'Pioneering New Frontiers': Fuqua Alumni Advise 'Farm-At-Your-Table' Food Truck

Photo by Special to The Chronicle | The Chronicle

'Pioneering New Frontiers': Fuqua Alumni Advise 'Farm-At-Your-Table' Food Truck

By Noah Michaud | 09/18/2017

If you stroll down West Geer Street on a Wednesday afternoon, you may be surprised to find a farm parked in front of you.

Meet the Farmery, which Ankur Sanghi and Ryan Graven—both Fuqua ’14—recently adopted. The brainchild of CEO Ben Greene, the Farmery is a multicomponent food truck and container farm model. It cooks with what it grows—whether it is exotic mushrooms, salad greens or herbs—every morning. Greene mentioned that they even had a mini-farm, the “CropBox,” behind a portable Airstream kitchen downtown, which they hope to reinstate soon.

“The model is very cool. It checks all the boxes,” said Sanghi, an advisor to the company. “It’s a much more efficient way of enjoying food. Instead of farm-to-table, farm-at-your-table.”

The Farmery brings to that table a cuisine they call “superfood fusion”—a mix of hearty salads, gourmet wraps, bowls and melts that highlight the fresh yet unique ingredients they grow. Beyond the East by West Bowl—Sanghi’s personal favorite—customers can also taste plates like the Earth First flatbread or the Do the Chimi Chicken Melt, which features their house-made chimichurri sauce. And the best part?

“All of our food is 100 percent free of preservatives,” Greene said.

In addition, all production is 100 percent free of chemicals and based off of “organic nutrients and growing substrates,” as stated on the website. Additionally, a 40-foot indoor farm only uses as much energy as a “large produce cooler” as a result of its hybridized system of vertical farming, aquaponics—fish farming and hydroponics—and specialized LEDs.

However, the Farmery goes beyond the local endeavors of healthy food and resourceful agricultural practices. Greene and his team are also looking to extend the Farmery’s influence far beyond Durham and the Research Triangle by constructing indoor farms for other clients.

Greene also spoke of his excitement about collaborating with North Carolina State University to perform studies testing the current production capacity of his model, as well as about traveling to Costa Rica in the future to introduce the model internationally.

The company's decisions are influenced by goals to fulfill its self-proclaimed mission of “social and environmental responsibility,” or “how [we] can disrupt that distribution system," as Sanghi said.

“[We want] to refine the fast-casual type restaurant on the restaurant end, and on the business end, become a new standard for production and consumption,” Greene said.

In the meantime, Greene is satisfied with the quick progress achieved so far.

“[We’re] executing a really good system, doing something new or doing something well that hasn’t been done well before," he said. "We’re pioneering new frontiers.”

5 Profitable Urban Farming Questions With Metropolis Farms

5 Profitable Urban Farming Questions With Metropolis Farms

Jack Griffin, President of Philadelphia-based vertical farming company Metropolis Farms, is known for his passionate support of the burgeoning indoor agriculture industry, whether that’s founding an industry association or representing the industry in Congress. We’re looking forward to hearing about his wide-ranging plans at Indoor Ag-Con Philly, and caught up with him ahead of that to hear more about his indoor agriculture world view.

1. Metropolis Farms has become a leader in the Philadelphia vertical farming scene. How did the farm come about?

Six years ago, I was working as the president of a merchant bank on Wall Street. Two very prominent Philadelphians came to our firm for a 25 million dollar investment to start an indoor vertical farm. After an enormous amount of due diligence I realized none of the existing farms were actually economically viable. They only thing they could grow was baby lettuce (basically crunchy water). There technical and scientific claims were a joke, and their financial projections had more in common with a game of three card monte then tier one financials. But the idea kept me up at night because economically sustainable indoor farms could not only produce food, medicine and energy, but would also create explosive local economies. If I could help build this new potential industry, cities would generate large amounts of green collar jobs to supply the existing demand while chase out the poverty and crush food deserts as a collateral consequence. It was on my mind constantly until one day I left Wall St to work on this problem myself. I made a giant list of everything that was wrong. I self-funded the research and dove in. It was a lot of work and a lot of what I call failing forward. We started on the “Mark1” about 5 years ago and here we are today with a solid commercial system at “Mark26”.

2. At Metropolis Farms, you take a ‘low tech, low cost’ approach to vertical farming. What’s the thinking behind that?

First off, we are definably not low tech. Our systems are actually among the most sophisticated in the industry. The difference is that they are designed to go up rapidly, and be operated and maintained simply with minimal training by people with high school educations instead of folks with PhDs and Master Degrees. We removed the over engineered complexity and excessive costs, not the technology. For indoor farming to truly become an industry, we need the technology to be accessible to everyone that wants grow, that means community groups and non-profits, not rich white men and cannabis farmers. We call it democratizing the technology. It has to cost less to build, grow more in less space, and it absolutely has to grow more than just baby lettuce and microgreens… We need to grow substantial nutrient dense foods to be taken seriously. Our mission is to make it possible for everyone that wants to farm to have access. That’s how we build the future.

3. You recently presented to Congress on urban agriculture. What did you learn from that experience?

While it was a positive experience, I learned that we as an emerging industry really need to step up our game. Right now, the organic farming lobby is trying to do everything it can to stop indoor farming from obtain organic status. In addition, the USDA’s current agriculture bill excludes Urban and Indoor farms from getting the same USDA funding that rural communities get. This is clearly a form of discriminatory redlining. Last year I was offered fifty million in USDA B&I funding, but only if I left the city for a rural community, because USDA B&I funding regulations actually excludes cities from funding. So I founded the National Urban Farmers Association and I am fighting to change the next agriculture bill so that city farmers have equal access to money that rural famers enjoy. We aren’t asking for a handout, just equal access. Today with almost zero funding cities like Philadelphia only have about 8 acres of urban farming. But back in 1944 city farms then called victory gardens produced over 40% of all the fresh fruits and vegetables in the United States. The difference is that back then urban farmers had access to the same funding that rural farms had. Now Urban farmers get nothing. This needs to change, and we as an industry need to stand up and change it.

4. What new tech developments in vertical farming are you most excited about implementing in your farm?

We are in final trials on a new lighting technology that reduces our cost of full spectrum lighting by about 25% (and no it’s not an LED). It also reduces the cost of direct energy use by a little over 30% and indirectly removes about 2,000 BTU’s per light for a massive savings on BTU management. Considering we already use 40% less energy than other vertical farms, this is a huge reduction. This new technology is incredibly disruptive to existing technologies and everyone’s going to want it, except of course the people making the current equipment in China, Taiwan and Japan. We plan on creating even more American green collar jobs by manufacture them at our Philadelphia factory. If all goes well, I’m actually considering showing it at the conference.

5. If you were starting out and had $1,000 to spend on an indoor farm and free space in your Mom’s basement, what farm equipment would you buy?

For either food or Cannabis, I would buy two ceramic lights and mount them in a reflective hood. Then I would add a light mover with a pair of hangers mounted on a 4 ft. piece of super strut to get better coverage and yield. Philips makes a great bulb for about $100.00 per bulb with a hood and digital ballasts that’s around $500.00. A light mover and strut should run less than $200.00. Then I would use “Roots Organic Original Soil” brand and some plane old plastic pots and saucer. Plus a good dry fertilizer for a top feed. I would recommend one of the “Down to Earths” brand dry fertilizer…they are excellent. Then get to work. This rig will grow flowing plants year round, but would be quite effective on leafy greens as well. Don’t let the low wattage fool you, these lights are powerful and full spectrum so don’t go super close to the canopy or you are going to burn your plants.

SEE JACK SPEAK AT INDOOR AG-CON PHILLY ON OCTOBER 16, 2017

Minnesota: Sustainable Indoor Vertical Farming In Action

Minnesota: Sustainable Indoor Vertical Farming In Action

Wisconsin State Farmer | Published 5:04 p.m. CT Sept. 16, 2017

(Photo: Associated Press)

ST. PAUL, MN - The Midwest has long been a major source of innovation when it comes to feeding the world, so it’s no wonder that the same state where Nobel Peace Prize winning agronomist Norman Borlaug was educated is now delivering on the promise of urban indoor aquaponics.

The St. Paul, Minnesota company Urban Organics, which uses aquaponics to raise fish and grow leafy greens, has already proven the viability of an idea that’s been getting national attention: year-round indoor farming. In fact, Urban Organics has been so successful in its pioneering approach that it recently added a second larger location to meet skyrocketing local demand for its fresh arctic char and salmon, and organic greens including bok choy, kale, lettuce, arugula, chard, and spinach.

In a sector of the food industry seeing substantial growth of new entrants, Urban Organics offers a highly differentiated approach to vertical farming that addresses market demand for both local and organic produce and protein.

Unlike typical hydroponic farming operations, the Company can supply produce that is USDA-certified organic by using solids produced in its fish culturing system as the nutrient source for the produce. Using natural waste products from one system as the primary input of another has substantial economic advantages and represents a far more environmentally sustainable and resource conservative approach to urban food production.

In 2014, the company opened its first indoor urban aquaponics farm inside an old St. Paul brewery complex — the former Hamm’s Brewery. Its 8,500 sq. ft. became home to a fully-operational farm which housed four 3,500 gallon fish tanks with 4,000 hybrid striped bass plus herbs and leafy greens—one of the largest and most advanced aquaponics facilities in the country. Local, national and international interest followed; England’s The Guardian called the farm one of 10 innovative concepts from around the world.

The Hamm’s farm proved the concept, as area restaurateurs and grocers demanded more ultra-fresh, ultra-local product than the location could provide. Global water company Pentair, with its main U.S. offices in Minnesota, was an early supporter of the Hamm’s location — designing, engineering and installing the innovative system with its water filtration and reuse technologies.

After the success of the Hamm’s location, Pentair and Urban Organics joined forces and expanded to a larger space in another unused urban brewery building—the 87,000 square foot Schmidt complex, which is in the middle of a revitalization including artists’ condos and a planned food hall.

That new Urban Organics Schmidt brewery location opened earlier this summer. Its 87,000 sq. ft. are home to 14 fish tanks and 50, 5-tier towering racks of greens, and when it reaches full capacity later this year, it will provide 275,000 lbs. of fresh fish and 475,000 lbs. of produce per year to the surrounding region.

The USDA-certified-organic farm has created jobs, brought life back into abandoned buildings, provided a global model for indoor aquaponics farming, and done it all without the use of pesticides - and while using significantly less water than traditional methods to grow produce.

“We started this venture as social entrepreneurs who wanted to figure out how to bring a reliable source of healthy foods into areas that had to rely on food transported in from far away,” said Dave Haider, co-founder of Urban Organics. “It turned out that our wild idea also made a lot of sense to a community hungry for organic, sustainably-raised food, and to other innovators around the world who had been asking the same questions we were. By collaborating with Pentair, we’re able to contribute beyond our immediate region - we’re able to test and perfect the technologies that will make a global impact advancing the field of large-scale commercial aquaponics.”

Urban farming is an extremely competitive endeavor, but Urban Organics continues to add products and customers. Earlier this summer, the farm rolled out nine different types of packaged greens and salads, now distributed through regional coops and grocery chains. And by next summer, arctic char growing in its tanks will be ready for harvest. Local health care provider HealthPartners, the largest consumer-governed health care organization in the nation, is now including Urban Organics greens in patient meals and serving them in its cafeterias. And restaurants, like Birchwood Café, are serving the greens as well.

Paris Embellishes Skyline With Organic Rooftop Farms

Paris Embellishes Skyline With Organic Rooftop Farms

© Louise Nordstrom, FRANCE 24 | The organic farm perched on top of the RATP-building in eastern Paris is one of the first commercial rooftop cultivation grounds in Paris

Text by Louise NORDSTROM | Latest update : 2017-09-02

Paris has taken the farm out of the field and planted parts of it onto its rooftops to make the city greener and more sustainable. This summer, metro operator RATP became one of the first companies to host a commercial farm on one of its roofs.

A sudden breeze carrying gentle notes of basil and mint envelops pedestrians walking by the RATP building at Place Lachambeaudie in the 12th arrondissement, a middle-class district located in the east of the French capital. Some passersby quickly lift their noses to try to figure out exactly where the fresh and appetising scents are coming from, but none seem able to locate the origin.

The scents are coming from the top of the grey and arch-shaped office building where Michel Desportes and Théo Manesse have been spending the better part of the afternoon harvesting row upon row of various types of organically-grown herbs ranging from violet-coloured basil to chocolate-and-banana-flavoured mint.

Louise Nordstrom, FRANCE 24 | Michel Desportes picks zuccini flowers at the farm on top of the RATP building

“It’s growing so much at the moment that we have to harvest every day,” Desportes, one of the founders of the start-up Aéromate which runs the farm, tells FRANCE 24. Bees and ladybugs constantly buzz around the plants, seemingly oblivious to the traffic and pollution on the streets down below.

“They’re all over the place,” Desportes says.

Louise Nordstrom, FRANCE 24 | The lush, green plants attract a lot of bees and ladybugs

Inca technique

The farm was started in July this year after a 2016 call by the City of Paris for a series of urban agriculture projects to make the city more environmentally sustainable. By 2020, Paris aims to have transformed 33 hectares, or 330,000 square metres, of its unused urban space into urban agriculture.

Although the commercial Lachambeaudie farm, which sprawls over a 450 square metre area and houses up to 5,000 plants, mainly focuses on growing fresh herbs, it also offers some seasonal fruits and vegetables. At the moment, this includes several different species of tomatoes, zucchini, peppers and lettuce. This winter, Aéromate plans to cultivate crops like watercress, spinach, cabbage, Brussels sprouts and artichoke. Everything is grown hydroponically, a hydroculture method developed by the Inca and Aztec Indians and in which the plants are grown without any soil by using only mineral nutrient solutions in water solvent.

Louise Nordstrom, FRANCE 24 | Aside from herbs, Aéromat also grows seasonal fruit and vegetables like peppers and tomatoes

“The tomatoes are delicious, you really can’t compare the quality to the ones you get in the store,” says Eric Poutong, who bought a basket of the farm’s products at RATP’s weekly fruit and veg sale on Thursday.

“I get a basket almost every week.”

A greener Paris

The decision by RATP to install and invest in the farm is part of its corporate mission to contribute to a more sustainable Paris. The group, which owns several buildings in the city, has identified 1.4 hectares (14,000 square metres) that it plans to transform into cultivated grounds by 2020.

Louise Nordstrom, FRANCE 24 | The Aéromat team need to harvest the fields every day

Emeline Becq, project manager for RATP’s property development arm SEDP, said the Aéromate herbal garden fits perfectly into that picture.

“We wanted to do something with our unused rooftops – up until now they haven’t really served any particular purpose - and this concept turned out to be just the right thing for us.”

Thirty-one tons

Aéromate is currently setting up a 180-square-metre farm, also on the roof of real estate group Tishman Speyer, at Place de la Bourse in central Paris, and is planning for a third commissioned by the City of Paris at the nearby Place de la République.

Louise Nordstrom, FRANCE 24 | The farm occupies a 450 square metre-space that was previously unused

Aside from selling the herbs and produce to staff of the companies that own the buildings, Aéromate also offers its harvest on online platforms such as “La Ruche qui dit oui!”, which connects local producers with consumers directly. Aéromate has also begun doing business with local restaurants and bars, of which two of its current customers are Michelin-starred eateries. As the business grows, Aéromate expects to harvest up to 31 tons of herbs, fruits and vegetables each year.

“It feels good to work up here. I feel lucky to be surrounded by all these green plants while actually working in the centre of the city,” Desportes says.

Date created : 2017-09-02

Dutch Engineer Aims High With Latest Green Roof Design

Dutch Engineer Aims High With Latest Green Roof Design

Mike Corder, Associated Press

In this photo taken on Tuesday, Sept. 5, 2017, Joris Voeten inspects the rooftop garden he helped develop in Amsterdam. Voeten, an urban engineer in Amsterdam has unveiled a new kind of rooftop garden that he says can store more water than existing roofs and feed it to plants growing on shallow beds of soil

Photo: Michael C Corder, AP

September 10, 2017

AMSTERDAM (AP) — Standing between raised beds of plants on top of a former naval hospital, Joris Voeten can look across to the garden, cafe and terrace that decorate the sloping roof of Amsterdam's NEMO science museum.

Such productivity is part of the urban engineer's vision for cities worldwide, places where he sees the largely neglected flat tops of buildings doing more than keeping out weather and housing satellite dishes.

Voeten, of Dutch company Urban Roofscapes, says a rooftop garden system he unveiled Friday on the former hospital roof stores more rainwater than existing green roofs and requires less power by relying on a capillary irrigation system that uses insulation material instead of pumps to water plants.

"You can relax here, you can have meetings here. You could operate a restaurant on your rooftop garden to make it more economically beneficial," Voeten told The Associated Press ahead of the official presentation. "But most of all, we finally get to exploit the last unused square meterage in the urban environment."

Roofs that are adapted so plants can grow on them produce a cooling effect on buildings and the air immediately above them in two ways. The plants reflect heat instead of absorbing it the way traditional roofing sheets do. They also reduce heat by evaporating water.

Voeten said readings taken on a very hot day showed a temperature difference of up to 40 degrees Celsius (72 degrees Fahrenheit) between his hospital garden above the banks of a busy waterway compared with a roof covered in black bitumen.

Robbert Snep, a green roof expert from Wageningen University and Research in the central Netherlands, said the cooling effect is well known, but the new roof in Amsterdam is an improvement on existing designs because of the way it stores water and can feed it back to plants.

Sensors in the shallow layer of soil on top of the water storage elements monitor qualities such as temperature and moisture content. If the soil gets too dry, extra water can be added. If there is too much water, it can be released into the drains.

"The smart roof really ensures that there is evaporation during, for example, heatwaves and thereby they cool the surroundings," Snep, who is not involved in the project, said. "People can sleep well and people can work well in such an environment."

Voeten says his system can be laid on any flat roof with sufficient load-bearing capacity, Voeten said. Costs would likely be around 100-150 euros ($120-180) per square meter (10 square feet), he estimates.

Amsterdam, a city built around water and its World Heritage-listed canals, is keen to have its residents turn their rooftops into gardens where possible. To promote the practice, the city is offers subsidies to help meet the costs.

"We ask citizens of the city to create rooftops like this. We ask companies to create rooftops like this," Vice Mayor Eric van der Burg said. "Not only for water storage, not only for helping cooling down our city, but also to create extra gardens, extra green for our inhabitants."

For Profit Hydroponic Farm in Chicago Seeks to Increase Employment Opportunities in Underserved Community

Since its inception in 2013, Garfield Produce has been working to improve economic growth and employment opportunities for Garfield Park community members. The for-profit business was born from a collaboration between a successful retired couple, Mark and Judy Thomas, and an engineering major from DePaul University, Steve Lu.

For Profit Hydroponic Farm in Chicago Seeks to Increase Employment Opportunities in Underserved Community

September 7, 2017 | Charli Engelhorn

Darius Jones, general manager, vice president, and part of owner of Garfield Produce, an urban hydroponic farm located in Garfield Park, a west-side community in Chicago. Photo courtesy of Garfield Produce.

“Education is the most important thing,” says Darius Jones, general manager, vice president, and part of owner of Garfield Produce, an urban hydroponic farm located in Garfield Park, a west-side community in Chicago. “We’re trying to create an environment that inspires people to grow and feel valued.”

Since its inception in 2013, Garfield Produce has been working to improve economic growth and employment opportunities for Garfield Park community members. The for-profit business was born from a collaboration between a successful retired couple, Mark and Judy Thomas, and an engineering major from DePaul University, Steve Lu.

Through missionary work with the Breakthrough Urban Ministries, Mark and Judy saw that their misconceptions about poverty—that it is the result of laziness and not taking advantage of the same opportunities afforded to others—were inaccurate, according to Jones. What the Thomas’ discovered was that people did want to work, but there were no opportunities available and a number of systemic obstacles in place that hindered people’s ability to work.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, Garfield Park changed from a predominantly Caucasian community to a predominantly African-American community, and most of the equity that existed has been removed over the past 25 to 30 years. As one of the top five communities in the city for crime rate and poverty, the infrastructure in the community has degraded, leaving close to 3,000 abandoned buildings and facilities and no real job opportunities, says Jones, a Garfield Park native.

“When they came to Garfield Park and saw how things were, they decided there needed to be some kind of business opportunity or job opportunity offering entry-level positions, since most of those available are located in far suburbs, requiring nearly a two-hour commute for a minimum wage job,” Jones says. “Steve brought in the urban agriculture component.”

As a young company, the current focus is building the business and increasing its income to be able to support more entry-level positions. This action is happening through relationships with Chicago-area chefs, catering companies, and restaurants, and will possibly expand to include a relationship with Whole Foods, which has approached Garfield Produce about carrying its products in their stores.

“We would love that relationship because it will help us scale faster,” says Jones. “Any dollars spent on our business go directly into a community member’s pocket. We’re tracking key performance metrics so we can show our customers where their dollars are going and how many hours of gainful employment their spending affords.”

Garfield’s vertical hydroponic farm, housed in a 5,600-square-foot facility, yields approximately 2,000 to 5,000 pounds of 25-30 varieties of specialty micro greens and micro herbs, such as pea tendrils and greens mixes, a year. The farm’s production modules currently occupy only 320 sq ft. Another 2,200-square-foot grow room is in development, which will increase production to 21,000 pounds a year and add another five to 10 varieties of greens.

The hope is that this greater yield will translate into more income, allowing the company to increase their workforce from two—Darius and one grower—to approximately 11 with the addition of another grower and grower’s assistant, a sales position, and six more entry-level positions.

“We’re talking about entry-level positions that would make a little more than minimum wage, but we’re setting up the company so employees can have ownership,” Jones says. “We want the business to be fully employee owned, so even though an entry-level job wouldn’t be life-altering, equity in a company would be.”

The main challenge in employing members of the community is finding people with enough knowledge and training. The company hopes to overcome this impediment by working with local organizations that do job training for the area’s large number of people with felony convictions, which accounts for 65 percent of the population, according to Jones, who went through a similar job-training program seven years ago.

“A lot of these guys will go through three to nine months of transitioning job training through organizations that get state or federal money, and in some areas, that includes sustainable urban agriculture training, but once they are finished, there are no jobs for them,” Jones says. “This is perfect for us because providing these jobs is exactly what we want to do.”

The company also continues to work with Breakthrough Urban Ministries, which, as well as providing men’s and women’s shelters, a food pantry, and a healthy food kitchen, supports the people in their housing program with entry-level job training. The one employee besides Jones was found through the ministry’s men’s shelter in 2014.

The partnership with the ministry also includes donations of leftover harvested greens to the food pantry. Jones would love to expand this partnership to include more activities, such as food demos, but admits that part of the downside of a for-profit business is a lack of logistical feasibility to get out and educate the public with efforts that are not sales-based, an issue that also influences their customer base.

“We don’t have the manpower to be out marketing and educating the community about our products. So, right now, we are looking to bring dollars into the business, get it built up, and then start pushing the products into the community,” says Jones.

Jones wants the business model to be scalable, sustainable, and replicable so they can take it to another of the many underutilized facilities on the west side of Chicago and build the same footprint using the same sales channels to make it profitable for other communities.

“We’re not just an organization coming into a neighborhood without knowing anything about it; we’re coming in with knowledge of the neighborhood,” Jones says. “We know most of the local consumers think micro greens are too expensive, so we can talk to the people in the community about what urban agriculture is and the benefits of micro greens, find ways to use more economical packaging and bring the costs down so local consumers are not scared away.”

Garfield Produce will begin opening its doors to community members for tastings soon and hopes to increase its education efforts by working with local schools. The company is already in partnership with Nick Greens Grow Team, a group specializing in hydroponic and controlled-environment agriculture, to sponsor hydroponic systems in schools so students can learn the importance of growing their own food and use the food they grow in their lunches.

Plants In The Sky

Plants In The Sky

NANETTE DUPREE 3 SEPTEMBER 2017

The urban sprawls of the world have taken over good chunks of the earth, leaving little green to be found within these cities. However, Paris has taken a measure to bring the greenery back into the city. RATP, which is a metro operator located in Place Lachambeaudie in the 12th arrondissement (a middle class district east of Paris), has become one of the first companies to place a commercial farm on top of its roof.

According to France 24, the project was crafted in 2016 when the City of Paris called for a collection of urban agricultural projects to be completed in order to make Paris more environmentally sustainable. Paris hopes to have converted 33 hectares (330,000 meters) of unused city space into agriculture by the year 2020.

The farm, dubbed Lachambeaudie farm, currently houses around 5,000 plants. It mainly focuses on growing herbs, but it also houses seasonal fruits and vegetables. Their selection includes tomatoes, zucchini, peppers, and lettuce. This winter, plans are in place to plant new additions, such as watercress, spinach, cabbage, Brussels sprouts, and artichoke. All of the plants are grown hydroponically, which is a planting method developed by the Inca and Axtec Indians. It involves the plants being placed in mineral nutrient solutions mixed with water solvent instead of soil.

RATP's decision to take on this urban farm is a part of its mission to help Paris to become a more sustainable city. The company plans to convert more of its rooftops into urban farms by the projected date of 2020.

Presently, Aéromate is planning to set up more urban farms with other companies and hoping for similar success. The company has also started doing business with local restaurants and bars, and plans to harvest up to 31 tons of herbs, fruits, and vegetables per year.

Sudbury Container Farm Producing Smart Yields For Producers

Smart Greens was founded by business partners Eric Amyot and Eric Bergeron in Cornwall in 2014. They started out with a refurbished shipping container, using hydroponics and LED lighting to create a climate-controlled environment that reduces growing hazards, such as pests and harsh weather. Eventually, they improved the design, adapted the technology, and came up with their current model.

Sudbury Container Farm Producing Smart Yields For Producers

Smart Greens-Sudbury is a new container farm that’s producing 100 pounds of kale a week. Its owners believe indoor, contained farming is the future of food production.

Steph Lanteigne harvests kale from his container farm in the Sudbury bedroom community of Chelmsford. (Lindsay Kelly photo)

At the Sudbury farmers market on a recent Thursday afternoon, Erin Rowe and Steph Lanteigne unloaded their usual 75 bags of freshly picked kale, hoping to find buyers for their harvest. Just 90 minutes later, they were completely sold out.

The crisp, leafy green has incited a fervent fanbase amongst the market’s clientele since they began cultivating the crop at their Smart Greens-Sudbury indoor hydroponic farm just outside of Sudbury in April.

“The response has been fantastic,” Rowe said. “It’s modern farming. I believe that it’s the future, especially Northern farming.”

Smart Greens was founded by business partners Eric Amyot and Eric Bergeron in Cornwall in 2014. They started out with a refurbished shipping container, using hydroponics and LED lighting to create a climate-controlled environment that reduces growing hazards, such as pests and harsh weather. Eventually, they improved the design, adapted the technology, and came up with their current model.

The Smart Greens-Sudbury container farm resembles a shipping container, but is specifically tailored to farming, using four-inch-thick structural insulated panels designd for walk-in coolers. (Lindsay Kelly photo)

Plants are cultivated from seed and then transplanted into vertical growing towers, which allows the farmers to grow up to 4,000 plants in just 400 square feet of space. The amount of water, nutrients, and light are all controlled by a programmable computerized system.

Several crops have been tested by the founders, but for Rowe and Lanteigne, kale is proving to be a hardy, quick-growing cultivar that’s high in demand. They can harvest the leaves from one plant, which regrow at a quick pace, multiple times for up to three months before a new seed has to be planted.

“What we’re finding is kale is a really unique product,” Lanteigne said. “It’s unlike anything else that’s on the market. The fact that it’s hydroponic means that it grows very quickly and it doesn’t get that bitterness, the stalkiness that you get with regular kale.”

The couple aren’t farmers by training — Rowe is a teacher, while Lanteigne has degrees in biology and applied linguistics — but they came across the idea for container farming while contemplating a return home to Canada after a 12-year stint teaching English in South Korea.

Searching out a new challenge that would let them spend more time with their four-year-old daughter, Indie, Lanteigne came upon the Smart Greens website and started an 18-month conversation with the founders to determine if it was the right move.

They bought some property, sight unseen, in the Sudbury bedroom community of Chelmsford, and got their farm on April 19. Smart Greens-Sudbury became one of six container farms in the Smart Greens network and the first in Northern Ontario.

Within eight weeks, the farm was producing its first kale. That quick turnaround, from inception to first harvest, is one of the most attractive facets of the system. And it keeps producing 52 weeks of the year, regardless of growing conditions.

“When we’re monocropping for kale, depending on how good of a job we do that week, we can get between 100 and 150 pounds a week perpetually,” Lanteigne said.

He believes there’s ample opportunity for growth in the sector, although the technology isn’t quite ready to roll out on a large scale, at least for the average farmer. A Smart Greens farm requires a huge investment — in both money and time — although it does come with full support from the parent company, including help from a master grower, technological advice and marketing assistance.

“Absolutely, the hydro bill is expensive. It's probably our number one operating cost; there's no getting around that,” Lanteigne said.

“But for every one per cent of energy cost that I increase, I'm getting one per cent increase in biomass. So, for us, the hydro costs are significantly offset by the fact that these plants grow that quickly.”

Lanteigne, in particular, has spent long days fine-tuning the levels of nutrients, water and lighting in order to find the perfect mix that will return the best yields. And yet, there’s still room for human error.

Early on in the process, one day before a harvest, the entire crop of kale nearly failed because the plants weren’t getting water: they had forgotten to turn on the valve that would deliver the water to the plants, something Lanteigne calls a “terrifying” lesson.

Since then, it’s been mostly smooth sailing. In addition to regularly selling out of their harvest at the farmers market, the couple has a number of restaurants on their client list, which is growing. They’ve even turned an early crop of basil into pesto. Demand for their kale is increasing, and there are already plans in the works for expansion.

“Our plan for the next six months to a year is farm number two: the identical system to this one, but with little tweaks here and there to make it a little bit more efficient,” Lanteigne said.

“In three to five years, we want to use the same technology, but in a warehouse.”

As they increase their output, the couple expects to hire additional staff to help with planting and harvesting, all of which is done by hand.

Financing for the second farm is already in place, said Lanteigne, who expects it to arrive in late October or early November — when other producers are shutting down for the season, they’ll actually be ramping up production and doubling their output, although which crop they’ll take on this time around is still up for debate.

“Spinach is on the table, lettuce is on the table, and quite a few restaurants want us to grow basil and mint,” Lanteigne said. “It’s a balancing act between what we can grow together, what we should be growing commercially, in terms of finances, and what people want.”

This Company Is Developing Pop-Up Urban Farms for City Streets

Exsilio Oy has responded to this challenge with its EkoFARMER, a small, self-contained farming chamber containing all the necessary seeds (from greens to herbs to plants), as well as adjustment mechanisms, meaning that output will not be affected by seasonal or climate factors.

This Company Is Developing Pop-Up Urban Farms for City Streets

Exsilio Oy is making a big splash in community gardening efforts with its EkoFARMER. The little greenhouse in a box is a very creative solution to producing high yield in urban areas with limited space and limited resources.

September, 10th 2017

EkoFARMER Farming ChamberExsilio Oy

From the East Coast to the West Coast, the United States has been seeing in the last decade a kind of community garden renaissance. More people are demanding better access to fresh, organic produce, without paying the high prices associated with organic food in the US—there are advocates for and against it on both sides, and little agreement about whether it is too expensive or if the high prices are justified. The reality is, though, that not all of us have a green thumb or the time and resources to know where to begin.

Source: Exsilio Oy

Exsilio Oy has responded to this challenge with its EkoFARMER, a small, self-contained farming chamber containing all the necessary seeds (from greens to herbs to plants), as well as adjustment mechanisms, meaning that output will not be affected by seasonal or climate factors. The Finland-based company has even created an interactive video with 3D models explaining the various parts and how they all work together. The boxes use house farming technology which controls the environment and helps to increase yield.

Source: Exsilio Oy

Fighting the Tide of Food Deserts

Green activists and members of the community are combining their efforts to respond to the main two issues driving the community garden revival: price and access. For some in the community, the need is more urgent, as urban deserts—impoverished areas which face critical issues related to accessing affordable and nutritious feed—have been appearing in virtually every city in the United States in the last two decades. The issue is of such growing concern that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) officially identified the term back in 2011, creating a Food Access Research Atlas and other maps which list essential data related to charting the problem, such as population demographics and proximity to supermarkets.

Source: American Nutrition Association

Michigan State University Assistant Professor of Community, Agriculture, Recreation and Resources Studies Phil Howard—one of the most vocal academic voices about the impact of food deserts in America explains the phenomenon of food deserts:

“The term ‘food desert’ kind of implies it's a natural phenomenon...What’s really been happening in some areas described as ‘food deserts’ is that they used to have supermarkets or chain grocery stores, and those stores have been shut down as they've been opening new stores in the suburbs. It's not a natural phenomenon at all.”

A company with a strong Exsilio Oy has begun a number of initiatives with businesses and is partnering with the community through its micro-entrepreneur and business co-partnering projects and is committed to making a difference.

Howard continues: “A desert implies either there's no food, or there is food, and the reality is a lot more complicated..Often, people in [these] areas have access to a lot of food-like substances that are not very healthy. Or they may have access to [only] a few types of fresh fruit and vegetables...”

Of course, intervention and measures taken by policy makers is a key part of the process; however, the powerful initiative of urban communities will have the biggest impact. Companies like Exsilio Oy, therefore, are empowering people every day to make nutrition and wellness a high priority.

Via: Exsilio Oy, Pacific Standard, Consumer Reports

US Representative Marcy Kaptur Introduces Bipartisan Urban Agriculture Production Act

Linked by Michael Levenston

Kaptur helped kick off a capital campaign for the next phase of the successful Oneida Street greenhouse project in 2011. Young people learned urban agriculture techniques, aquaculture, apiary science, gardening, and life skills.

Bill Bolsters USDA Nutritional and Farmers’ Market Programs and Works to Spur Economic Development

Press Release | September 8, 2017

Washington, D.C. – Congresswoman Marcy Kaptur (OH-09), today introduced the Urban Agriculture Production Act (H.R. 3699), a bipartisan bill to bolster nutritional and farmers’ market programs and help create the next generation of local, urban farmers and food producers. The bill is supported by the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition and Farmers Market Coalition.

“Too many urban neighborhoods are in food deserts that lack stores where people can purchase fresh, healthy foods, so the federal government needs to step up and improve access to nutritious foods,” said Kaptur. “Nutritious and healthy eating can reduce the rate of diabetes, hypertension and obesity related illnesses and my bill builds on successful nutritional programs, like the Seniors Farmers’ Market. As Congress readies to debate the Farm Bill, I’ll fight for programs that bolster farmers, develop our urban centers and help create jobs.”

The bill works to spur the development and expansion of regional and local food systems in nontraditional agriculture production areas, like cities and towns. The bill also works to strengthen farmers’ markets, improve nutrition for low-income seniors and veterans and bolster existing U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) programs that support farmers, ranchers, and producers as a tool for economic development.

“Communities are addressing these challenges by developing local farmers markets, community gardens, greenhouses, and other food systems to provide fresh, affordable and healthy foods throughout underserved communities and this bill will build on that work,” Kaptur continued.

During her tenure in Congress, Kaptur has been a champion of farmers’ markets and other programs and one of the chief authors of urban agriculture legislation. Her legislative efforts have focused on creating places in urban areas to cultivate community agriculture that improve the self-sufficiency of neighborhoods.

Kaptur introduces the Urban Agriculture Production Act just as Congress prepares to debate the upcoming Farm Bill reauthorization. Her key goals are to support direct marketing opportunities for local farmers and producers, advance local agriculture in our nation’s most underserved areas, and increase the consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables for our seniors and veterans.

What does the bill do?

Establishes an Urban Agriculture Liaison and Outreach Program at USDA

Expands the Senior Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program to include veterans

Provides for competitive grants to advance agriculture production in underserved, undernourished metropolitan areas

Creates a loan and loan guarantee program for projects that expand and promote direct producer to consumer marketing and assist in the development of local food business enterprises.

Improves federal agricultural reporting with the inclusion of Farmers Markets in the Ag. Census

AeroFarms Gets $1 Million Research Grant

Plants grow at indoor vertical farming company AeroFarm's research and development facility in Newark, N.J. The company has been awarded a $1 million Seeding Solutions grant from the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research to improve controlled environment specialty crop characteristics such as taste and nutritional quality.

Photo by AeroFarms

Newark, N.J.-based AeroFarms has been awarded a $1 million Seeding Solutions grant from the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research.

The foundation is a nonprofit organization established in the 2014 farm bill, according to a news release, and the grant was celebrated by research and industry leaders at a Sept. 7 function at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

AeroFarms, an indoor vertical farming company, will match the foundation’s grant for a total investment of nearly $2 million, according to the release.

Principal investigator Roger Buelow, chief technology officer at AeroFarms, will work with Rutgers University and Cornell University scientists on using vertical farming systems technology to improve specialty crop characteristics such as taste and nutritional quality.

According to the release, the project seeks to advance crop production by measuring the link between stressed plants, the phytochemicals they produce and the taste and texture of the specialty crops grown.

The work is expected to result in commercial production of improved leafy green varieties and yield science-based best practices for farming, according to the release.

“With more than half the world living in urban areas, continuing to provide nutritious food to the burgeoning population must include envisioning our cities as places where abundant, nutritious foods can be grown and delivered locally,” Sally Rockey, executive director of the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research, said in the release. “We look forward to seeing this grant to AeroFarms catalyze innovation in vertical farming and plant production for the benefit of urban farmers and the communities they serve.”

David Rosenberg, co-Founder and CEO of AeroFarms, said in the release that the company was honored to have been selected for the award.

“This FFAR grant is a huge endorsement for our company and recognition of our history and differentiated approach to be able to optimize for taste, texture, color, nutrition and yield and help lead the industry forward,” he said in the release.

Information gained from the research will be published and presented at controlled environment agriculture industry conferences, according to the release, including events tailored to startup companies and prospective entrepreneurs.

“Pioneering initiatives like the work by AeroFarms and FFAR will help lead the produce industry with a science-backed approach to understand how to grow great tasting and nutritionally dense products consistently all year,” Tom Stenzel, CEO of United Fresh Produce Association, said in the release. “We believe that there is a need for even more public/private partnerships like this to spur breakthroughs.”

Topics: AEROFARMS FARM BILL INDOOR FARMING URBAN AGRICULTURE

About the Author: Tom Karst

Tom Karst is national editor for The Packer and Farm Journal Media, covering issues of importance to the produce industry including immigration, farm policy and food safety. He began his career with The Packer in 1984 as one of the founding editors of ProNet, a pioneering electronic news service for the produce industry. Tom has also served as markets editor for The Packer and editor of Global Produce magazine, among other positions. Tom is also the main author of Fresh Talk, www.tinyurl.com/freshtalkblog, an industry blog that has been active since November 2006. Previous to coming to The Packer, Tom worked from 1982 to 1984 at Harris Electronic News, a farm videotext service based in Hutchinson, Kansas. Tom has a bachelor’s degree in agricultural journalism from Kansas State University, Manhattan. He can be reached at tkarst@farmjournal.com and 913-438-0769. Find Tom's Twitter account at www.twitter.com/tckarst.

Post-Industrial Pittsburgh to Host America's Largest Urban Farm

SEPTEMBER 10, 2017

Post-Industrial Pittsburgh to Host America's Largest Urban Farm

NEW YORK (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - The U.S. city of Pittsburgh, once a dynamo of heavy industry, will soon become home to the country’s largest urban farm, part of what advocates say is a trend to transform former manufacturing cities into green gardens.

The Hilltop Urban Farm will open in 2019, consisting of 23 acres (9 hectares) of farmland where low-income housing once stood, two miles (3 km) from the city center, designers say.

On top of farmland where winter peas and other fresh produce will be grown by local residents and sold in the community, the farm will feature a fruit orchard, a youth farm and skills-building program. Hillside land will eventually have trails.

The farm is believed to be by far the largest nationwide to be located in an urban area, said Aaron Sukenik, who heads the Hilltop Alliance that is coordinating the initiative.

“The land was just kind of sitting there, fenced and looking very post-apocalyptic,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

After Pittsburgh boomed during the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a center of coal production, steel and manufacturing, it was hit by industrial decline in the 1950s, its population cut by half over the next half century.

Reinventing itself, the metropolis has since regained much of its economic vigor with the healthcare industry replacing manufacturing as the city’s powerhouse.

But while “all the areas that you can see from downtown really have turned around,” several neighborhoods on the city’s outer ring have yet to see a similar resurgence, said Sukenik.

“It’s those neighborhoods that are the focus of our work,” he said.

Open to local residents, the farm will help bring fresh food to surrounding areas that often lack such options, he said.

Pittsburgh has the largest percentage of people residing in communities with “low-supermarket access” for cities of 250,000 to 500,000 people, according to a 2012 report by the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

And local advocates say much of Pittsburgh’s Southside, where the farm will be located, is particularly underserved by supermarkets and other retailers of fresh food.

RUST BELT

The Hilltop Urban Farm embodies a trend in cities across America’s so-called Rust Belt from Detroit to Cleveland and Buffalo where manufacturing has died out, said Heather Mikulas, a farm and food business educator for Penn State Extension, an applied research arm of the Pennsylvania State University.

“You just have blight, just so much blight in Rust Belt cities,” she said.

“So you see the longstanding residents of neighborhoods who are used to trying to find their place in the world looking at this blight and just say ‘We can do something different, we can do something better’,” said Mikulas, who co-authored a report on the feasibility of the Hilltop Urban Farm project in 2014.

What were once often “guerilla” operations have morphed into projects working hand-in-hand with municipal authorities to secure land rights and re-zone areas to allow for agriculture, said Mikulas by phone.

A common concern with urban farms is their reliance on grants that eventually dry out, said Stan Ernst, a professor of agribusiness development also at Pennsylvania State University.

The $9.9 million Hilltop Urban Farm is funded by foundations, primarily the Henry L. Hillman Foundation.

“Look for ways that you can operate enough like a business that you can hopefully provide a level of sustainability there,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation by phone.

No comprehensive national study has yet measured the extent of urban farming in the United States, said Michael Hamm, a professor of sustainable agriculture at Michigan State University.

Globally, city dwellers are farming an area the size of the European Union, a 2014 study published in the journal Environmental Research Letters found.

Reporting by Sebastien Malo @sebastienmalo, Editing by Ros Russell; Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking, property rights, climate change and resilience. Visit news.trust.org

Our Standards:The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.

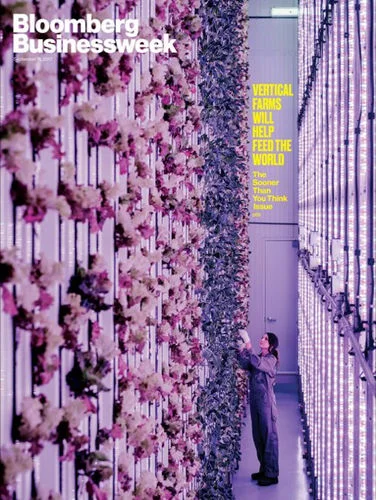

Laramie Start-Up Featured On The Cover Of Bloomberg Businessweek

- It didn’t take long for a company founded by a UW graduate student in 2011 to grow big enough to have an international reach and reputation. Bright Agrotech’s six-year growth surge was capped off this week by being featured in a cover story for Bloomberg Businessweek.

Bright Agrotech and its founder, Nate Storey have been covered closely by the Wyoming Business Report from the beginning. In 2011, when still a graduate student at UW, Storey won $10,000 in seed money in the Wyoming $10K Entrepreneurship Competition to help get his vertical vegetation towers off the ground. As part of his winnings, his growing company was planted in the Wyoming Technology Business Center (WBTC) incubator.

In 2012, Christine Langley, chief operating officer of the WTBC told the us that “We expect [Bright Agrotech] to be a very large business in the next three to five years.” It only took three.

In the fall of 2013, Whole Foods discovered Bright Agrotech’s vertical towers as a way to sell and display living organic produce in the store.

Just two years later, Bright Agrotech exited the WTBC incubator and set up shop in the ALLSOP Inc. warehouse and began working with the Laramie City Council and Laramie Chamber Business Alliance to secure a permanent building. 2015 was also the year that Bright Agrotech created the world’s largest food-wall for the USA Pavillion at the Worlds Fair in Milan, Italy. The wall featured 42 different crops along more than 7,200 square feet of growing space.

In 2016, Bright Agrotech introduced “CoolBar” a water-cooled LED lighting system to help plants grow and not cook inside a greenhouse. “Being able to decouple the light from the heat poses major benefits to indoor farmers everywhere,” Storey said at the time.