Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Spanish Pharmaceutical Giant Puts Growtainer into Operation

After installing the first international Growtainer in the UK last year, GreenTech Agro is expanding its presence in Europe with the recent installation of another Growtainer at Spanish biotechnological giant Bioibérica.

The Growtainer is the brainchild of Glenn Behrman, founder of GreenTech Agro and CEA Advisors. Two years after introducing his first Growtainers for sale in 2014, Behrman has now installed another EU Growtainer at the factory of leading Spanish pharmaceutical company Bioibérica in Pallafols, outside of Barcelona. Their enthusiasm for the Growtainer and vertical production has been driven by their interest in new, modern and sustainable indoor farming practices. They will use the Growtainer to produce leafy greens, herbs and vegetables for their canteen at the factory site, in order to gain more hands on experience with indoor growing.

"Bioibérica is a forward thinking company that is committed to discovering new technologies and industries", said Behrman. "They are open to new innovations and other industry angles that have a potential for capitalization.”

For the Bioibérica project, Behrman collaborated with Dutch horticultural installer Stolze, whose team transformed the used shipping container, outfitted by RCC Container Trading, into a vertical farm. After the installation at the Port of Rotterdam, the Growtainer was shipped to Spain where Behrman and an expert crew from Stolze completed the delivery with a final installation last week.

Proprietary technology

Inside Bioibérica's Growtainer there are a total of 12 Growracks divided into two separate production chambers. Ten of the Growracks have 4 layers and will be used for regular cultivation, and two racks with 5 layers each will be used for propagation.

Besides having a dedicated proprietary technology for ebb and flow irrigation installed, the Growracks are equipped with Philips GreenPower LED Generation 2 production modules, which are specifically designed for multilayer cultivation in conditioned environments with no daylight. The LED modules ensure a uniform light distribution across the shelves, which means that every plant receives the same level and quality of light.

The irrigation in the Growtainer is divided into six separate zones in order to provide flexibility and allow a wide variety of production of crops at various growth stages. Behrman worked closely with Stolze's engineers to design a sophisticated control system to manage the irrigation, climate, humidity and CO2 levels inside the Growtainer. The entire climate and crop control can be managed remotely via a computer or mobile phone.

Canteen & Research

Bioibérica will grow several crops inside the Growtainer, in the first place to supply their nearby canteen with everyday fresh and safely grown veggies. "They will use it to feed their employees first and gain indoor farming experience with it. While this is an important objective of the installation, Bioiberica is laser focused on the potential advances in their Bio stimulant products. They are excited to incorporate the Growtainer’s state of the art technology based production capacity for further research within their existing business models."

Behrman, who has a long term background in horticulture, has gained a lot of experience with technology based production and container farms over the past few years. "Thanks to the close cooperation with Stolze, VK Pro and RCC Containers, the Holland built Growtainers have become a real state of the art, completely proprietary system. While there are currently many other individuals in the US that offer shipping container farm systems, none of them is as flexible or sophisticated as this one, because this Growtainer version has focused on and tried to improve everything everybody else is trying to do."

Financing and substantial support

At the moment Behrman is continuing to improve the Growracks and building more Growtainers for clients in the United States. "But we have many other exciting plans to announce soon", said Behrman, not only referring to the several new installations in process. "We are almost ready to announce a more manageable crop specific Growtainer for the beginning farmer, with financing and a substantial support system in place, an onsite production initiative with a major US Supermarket Chain and other projects which focus on the highest and best economic use for this exciting and evolving technology.”

For more information:

CEA Advisors - GreenTech Agro

Glenn Behrman (e-mail)

www.growtainers.com

Publication date: 9/7/2016

Author: Boy de Nijs

Copyright: www.hortidaily.com

The Farm that Runs Without Sun, Soil or Water

(CNN) What do you get if you cross a tech entrepreneur with a farmer?

(CNN) What do you get if you cross a tech entrepreneur with a farmer?

The world's largest, and possibly most sophisticated indoor farm -- where greens grow without sun, soil or water.

Well, almost no water. AeroFarms, the company behind the venture, say they will use 95% less water than a conventional outdoor farm.

Set to open in September in Newark, New Jersey, the 69,000-square-foot farm will be hosted in a converted steel factory. It combines a technique called "aeroponics" - like hydroponics, but with air instead of water - with rigorous data collection, which will help these modern farmers figure out optimal conditions for growth.

The goal? To produce tall, handsome, tasty baby greens and herbs such as kale, watercress and basil.

Fighting a looming food crisis

This will be the largest farm of its kind in the world in terms of production capacity: 2 million pounds of greens a year, according to Aerofarms founder David Rosenberg.

But the company's ambitions go beyond selling vast amounts of veg. They also hope to provide an answer to a looming food crisis.

The world's population will hit 8.5 billion by 2030, according to UN estimates, meaning many more mouths to feed.

Most people now live in cities, with 54% of the world's population already living in urban areas.

Rosenberg says innovation is urgently needed to feed everyone, and urban farming might be part of the solution.

"We are building this company to be wildly impactful. Not just to build a few farms, but to change the world."

How it works

Inside the farm, there are no natural seasons, nights or days. Light, air humidity and temperature are all tightly controlled.

As soon as one harvest is in, another begins -- each plant is expected to yield between 22 and 30 harvests a year.

Long rows of LED tubes shed light at the exact wavelength each plant needs to thrive. Instead of soil, the plants are grown on a cloth made from recycled materials, and their roots are misted with a solution of nutrients.

The company says their method is superior to more commonly used indoor farming techniques like aquaponics and hydroponics, which require much more water, and that the plants taste the same, or even better, than their conventionally grown counterparts.

Aeroponic farming techniques have been used before. NASA astronauts use it to grow food at the International Space Station, for example, and home-grow DIY kits can be ordered from a number of companies online.

Farming with algorithms

To make sure the greens have everything they need, the company collects data from the plants to create algorithms for growth.

"We built our own software which take images of leaves to understand height, width, length, stem ratio, curving, color, spotting and tearing," says Rosenberg.

The light is altered to fit each plant

The long rows of so-called growing towers are more like computers than farms, with sensors everywhere observing the process. Every now and then, one of the farmers does an inspection to ensure all is well, explains co-founder Marc Oshima.

"We think of ourselves as plant whisperers, listening and observing everything we can do to optimize our plants. Our growing approach is really leading the way, marrying biology, engineering, and data science."

Their farms are partly run on renewables such as solar power, but what really gets the carbon footprint down is bypassing extensive transportation of the produce by only selling the greens to local markets, shops and restaurants.

Staying local is part of the philosophy. "We have had some request to go nationwide. It's tempting, but seems counter to our mission of locally produced food," Rosenberg says.

Beyond organic?

In addition to ultra-low water usage, not using any soil further reduces the environmental impact.

The crops are currently sold at a 20% premium, similar to organic and locally produced food, but because no soil is involved, they cannot get an organic certification, although some retailers consider them to be beyond organic, Rosenberg explains.

The closed-loop system uses only non-GMO seeds and no pesticides, herbicides or fungicides, and so it reduces the harmful agricultural run-off into the environment, says Rosenberg.

"I think we are going to have a bigger and bigger impact on leafy greens and other crops in the future. And the future is going to be very different, in large part because of data."

By Sophie Morlin-Yron

Motorleaf Is Nest Meets Lego For Next-Gen Agriculture

The world of agricultural technology, or Agtech, is rapidly evolving.

Motorleaf Is Nest Meets Lego For Next-Gen Agriculture

The world of agricultural technology, or Agtech, is rapidly evolving.

It’s automating laborious tasks and providing farmers and growers with greater knowledge and insight into their crops than ever before. As technology evolves so does the needs of the farmer and the growing environment. Around 20% of the world’s food production is grown within cities rather rural areas and inherent in this is the multi-billion dollar industry of indoor growing and hydroponics.

The industry includes $5 billion in urban farming in the US and $5.7 billion for legal cannabis production.

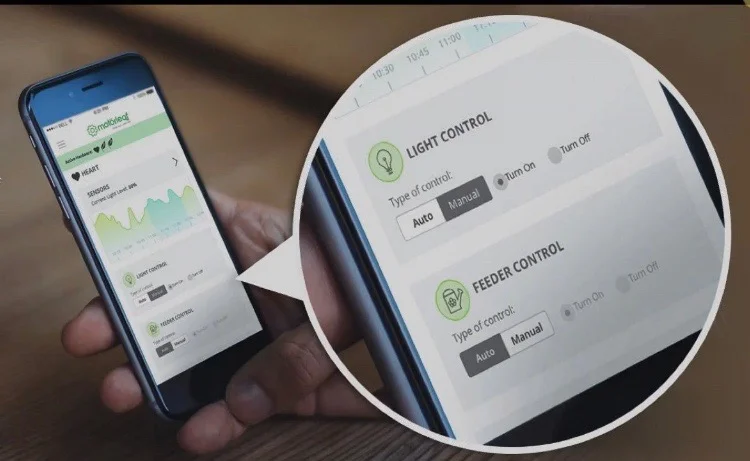

Agtech company motorleaf have released the world’s first wireless monitoring, motion detection and automated growing system for hobby and industrial growers. I spoke to CEO and co-founder Ally Monk to learn more.

According to Monk, the idea originated when as a keen indoor hobby gardener, motorleaf’s co-founder and CTO Ramen Dutta wanted to go on holidays and needed a system to take care of his plants in his absence:

“Ramen was going on vacation, but he had the problem of what would happen to his plants in his absence. He looked at the market and assumed there would be something like a smart home system akin to google Nest but there was nothing. So he started making a HUB that could monitor what was going on and automate a range of appliances such as the water chiller and water level, air temperature, webcam, heating, and cooling. He soon realized that other indoor farmers were interested."

How motorleaf works

The Heart

Motorleaf has created a system that can automate and monitor an indoor growth area with up to 5 acre coverage. Their hardware, described by some as “Nest meets Lego for agriculture” is designed to be plug-and-play, and the grower decides which part of their plant operation they control/monitor and automate. It consists of four modular units:

- The Heart collects Air Temp, Humidity, & Light Level data. Users can connect any lighting hardware, and feeder pump- and start automating their operation in seconds.

- The Power Leaf connects wirelessly to the Heart which tells them when to turn on and off, based upon pre-set times or sensor readings from the Heart and Droplet.

- The Droplet monitors everything that’s connected to a grower’s water reservoir. Every 4 seconds The Droplet wirelessly sends data to The Heart, information on water level, temperature, PH level, and nutrient levels.

- The Driplet allows growers to automate the delivery of PH and Nutrients, again based upon timer setting or actual live grow conditions.

The system is agnostic, retails for about $1,500 and contains free software which facilitates custom settings, so the motorleaf hardware will automate the grower’s equipment and adjust to their crop’s needs. It’s available online and offline as many growers do not have WiFi in their crop space. It also alerts the grower to any problems that need attending to.

More importantly, it also involves intuitive efforts in predicting and anticipating the needs of the plants. Monk says:

“We’ve never been able to speak to plants but now through technology we can listen to them through their data, we can then understand what they need and feedback instructions to the equipment that’s looking after them so we can best serve their crops.

He also notes the many people’s depiction of the farmer outdoor engaged in manual labour as not entirely actually noting “The farmer of the future looks after his farm through his mobile phone and tablet.”1 He adds that indoor growers in particular have needs which can be more complex than traditional farming:

“When you start growing indoors you have to mimic nature, they have worry bout all the things they have to control indoors such as PH; nutrients, humidity, light, air temperature. How are they controlling it? Switches, controllers, some software and in many cases people are still using pen and paper. Urban farming is on the rise but the technology that looks after this is really lagging behind.”

Motorleaf is well-timed to respond to an emerging market. They receive receives 40,000 data points per customer per week and therefore can start predicting a crop’s needs, solving potential problems before they exist. Also, the start-up plans to use its network of data and growers to connect users to each other – on an opt-in basis – to share data, plant recipes and knowledge.

With the growth in indoor agriculture, hobby farmers and small to medium enterprises will soon benefit from effective IoT technology that enables smart crops and smart farming.

By Cate Lawrence

This Indoor Farm Can Bring Fresh Produce to Food Deserts

This Indoor Farm Can Bring Fresh Produce to Food Deserts!

Almonds got the brunt of the bad press, but they hardly deserve all the blame for California’s water woes. Sure, it’s worth considering how to minimize your water footprint, and forgoing your daily handful of almonds in solidarity with the parched earth couldn’t hurt. But considering how widespread the water crisis is, and the fact that agriculture is responsible for 80 percent of the country’s water consumption, the more crucial question to be asking now—particularly on Earth Day—is what can be done to fundamentally change the way our food gets made?

Mattias Lepp says at least part of the answer involves making it easier for anyone—even city dwellers—to farm their own food. That’s why Lepp, founder of the Estonian startup Click & Grow, has developed what he calls a Smart Farm, an indoor farming system that requires 95 percent less water than traditional agriculture.

You may remember Click & Grow from their uber-successful Smart Herb Garden Kickstarter campaign a few years back. That product let people easily grow herbs in their homes with minimal maintenance. The Smart Farm is similar, but on a much larger scale. The system, which Lepp spent years developing in partnership with universities across Estonia, France, and Russia, can hold 50 to 250 plants at a time, making it a viable option for urban areas that don’t have access to fresh produce—areas the US government calls food deserts. Ideally, a shift to urban farming could drastically reduce the distance between where food is grown and where it is consumed.

The market for these indoor farms, or so-called vertical farms, is already fast-growing, driven by the growing realization that the current water-chugging agricultural system is unsustainable. On one end of the spectrum, countless DIY indoor farming enthusiasts are growing small gardens in their homes. On the other are professional outfits like Green Sense Farms out of Chicago, which grows leafy greens indoors and sells them at local stores. Even tech giants like Panasonic and Toshiba have begun developing gigantic de facto farms of their own in Asia, where there is a severe shortage of agricultural land.

And yet, the majority of these larger farms use hydroponic farming, a process that involves growing plants in mineral solutions instead of soil. They save anywhere from 70 to 80 percent of the water required for traditional agriculture, but they’re complex and can cost tens of thousands of dollars. For most of us, it wouldn’t be economically practical for you or me to grow a full-scale farm at home.

With the Smart Farm, which costs just $1,500, Lepp says it can be. “People all over the world have worked intensively the last 10 or 20 years on bringing food production closer to cities and finding ways to grow it more efficiently,” he says. “But today they all are using hydroponics, and that is unfortunately expensive and messy. We see how we can change this.”

Rather than relying on hydroponics, the Smart Farm uses a new type of soil called Smart Soil, which Lepp developed in partnership with academic advisors. The soil itself is spongey, allowing air and nutrients to flow through. Meanwhile, the nutrients are covered in a special coating that responds to soil moisture. The hardware, which looks like a glass refrigerator, consists of trays for each plant equipped with LED lights and sensors that detect when the moisture levels are off balance. The “farmer” can use an app to adjust the water levels in the system, which triggers more nutrients to be released.

This process cuts down on the amount of water required to grow the plants, Lepp says, because no wastewater is produced. At the same time, the time people have to spend actually tending to the plants is minimized.

“Click & Grow can give the plant the perfect conditions to grow, because air, water, and nutrients are dosed perfectly without any obstacles,” says Uno Mäeorg, a professor at the University of Tartu in Estonia, who worked with Lepp on the development of Smart Soil “And since those conditions are perfect for the plant, it provides us healthier plants.”

Be that as it may, the Smart Farm is still a long way from accomplishing Lepp’s eventual dream of putting a full-scale farm in every urban neighborhood. For starters, the system only supports a limited number of plants today, including strawberries, tomatoes, lettuce, and other herbs, though Lepp says that will change with time. Also, for now the Smart Farm is only available on a built-to-order basis. While the company already has orders coming in and pilot projects with universities, it won’t begin full-scale retail distribution until 2016.

Then there’s the simple fact that we’re all just plain used to buying food from a store. The dream of distributed farming may always be limited to the number of consumers who care enough to try it out.

Still, according to Dr. Dickson Despommier, a professor of public health and microbiology at Columbia University and author of the book The Vertical Farm, that number is growing steadily. And as more people become willing to give indoor farming a try, he says it’s critically important that they have tools, like the Smart Farm, to ease the effort.

“I think it could make a dent in the commercial side of things,” Despommier says of indoor farming’s potential to impact mainstream agriculture. “And if you look at what’s happening in California, there may not be a commercial side of things for much longer.”

Issie Lapowski

Kimbal Musk's New Accelerator In Brooklyn Will Train Vertical Farmers

Square Roots hopes to sprout urban farming entrepreneurs all over the country.

Kimbal Musk's New Accelerator In Brooklyn Will Train Vertical Farmers

When it opens this fall in Brooklyn, a new urban farm will grow a new crop: farmers. The Square Roots campus, co-founded by entrepreneurs Kimbal Musk and Tobias Peggs, will train new vertical farmers in a year-long accelerator program.

"Young people contact me all the time to articulate issues with the industrial food system but they are frustrated by their perceived inability to do anything about it," says Musk. "It's relatively easy to set up a tech company, join an accelerator, and progress down a pathway towards success. It's more complex to do that with food. Seeing this frustration—and pent-up energy—was a big part of the original inspiration for co-founding Square Roots."

The campus will use technology from Freight Farms, a company that repurposes used shipping containers for indoor farming, and ZipGrow, which produces indoor towers for plants. Inside a space smaller than some studio apartments—320 square feet—each module can yield the same amount of food as two acres of outdoor farmland in a year. Like other indoor farming technology, it also saves water and gives city-dwellers immediate access to local food.

New urban farmers will learn specific skills from mentors—how to grow plants hydroponically, or how to sell at farmer's markets (though hopefully it will be a little more advanced than the level of the very funny rendering Square Roots sent us, which you can see in the slideshow above)—and they'll also collaborate on new ideas. "The idea of 'the campus' came from watching magic happen at tech accelerators, like Techstars, where I've been a long time mentor," says Peggs, who will be CEO of the new accelerator. "The aim with the campus is to create an environment where entrepreneurial electricity can flow."

It's intended for early-stage entrepreneurs. "We're here to help them become future leaders in food," says Musk, who also runs a network of school gardens and a chain of restaurants that aim to source as much local food as possible.

After building out the Brooklyn campus, they plan to expand to other cities, likely starting with cities where Musk also runs his other projects—Memphis, Chicago, Denver, Los Angeles, Indianapolis, and Pittsburgh. Each location will have 10 to 100 of the shipping container farms; Brooklyn will start with 10.

"We have a lot to prove in Brooklyn but our aim to replicate the model in every community as soon as we can," says Musk.

The accelerator is looking for its first class of applicants now, and taking applications on its website.

[Photos: via Square Roots]

Can Kimbal Musk Do for Farms What Elon Has Done for Cars?

“1,000s of millennials to join the real food revolution”

For more than 150 years, Pfizer manufactured pharmaceuticals in its 660,000-square-foot factory on Flushing Avenue in South Williamsburg, Brooklyn, New York. The pharma giant shut down operations in 2008, and since 2011, a host of food start-ups have taken up residence in the building’s cavernous halls. Starting next year, the bakeries and distilleries and kimchi companies will be joined by a venture called Square Roots. Founded by Kimbal Musk and Tobias Peggs, the urban farming accelerator aims to empower “1,000s of millennials to join the real food revolution,” as Musk (Elon’s brother) wrote in a Medium post announcing the venture last week.

“Our goal is to enable a whole new generation of real food entrepreneurs, ready to build thriving, responsible businesses,” Musk continued. “The opportunities in front of them will be endless.”

Square Roots’ real-food revolution will be built around container farming: shipping containers retrofitted into self-contained, highly efficient hydroponic mini farms. Beginning next fall, 10 ag-tech entrepreneurs will each develop an urban farming business in their own 350-square-foot shipping container housed in the Pfizer building. The containers will be able to produce the equivalent yield of two acres’ worth of farmland annually, with 80 percent less water than a conventional farm, according to Musk.

Brooklyn will be just the beginning: “Square Roots creates campuses of climate-controlled, indoor, hydroponic vertical farms, right in the hearts of our biggest cities,” Musk wrote on Medium. “On these campuses, we train young entrepreneurs to grow non-GMO, fresh, tasty, real food all year round, and sell locally. And we coach them to create forward-thinking companies that—like The Kitchen [Musk’s chain of eco-friendly restaurants]—strengthen communities by bringing local, real food to everyone.”

Square Roots joins the growing ranks of high-tech indoor-farming operations that are cropping up in old industrial sectors of major cities across the country—from Newark’s AeroFarms to Chicago’s FarmedHere—that are seeking to both shorten the food-supply chain and fundamentally reimagine the American farm as a high-tech, urban, factory-like operation.

If Square Roots and its contemporaries succeed, the country will be awash in locally grown lettuce, kale, and herbs. But the question is, how much locally grown lettuce, kale, and herbs do we need beyond what is already being produced? Is growing greens and herbs in shipping containers or old factories better—in terms of resources, emissions, and the environment—than growing them on farms in the Southwest? A container-farm entrepreneur can grow lettuce with less space and water than a farmer in California and Arizona, where the bulk of American lettuce is grown. But the question of sustainability isn’t answered quite so easily—and a greens revolution in agriculture can only do so much to address the problems the industry faces.

“I don’t think these big sweeping urban agriculture ideas are going to happen anytime soon,” Raychel Santo, a program coordinator at the Johns Hopkins’ Center for a Livable Future and a coauthor of a report on the potential of urban agriculture, told TakePart in May. Instead of supplanting traditional, rural agriculture, she sees urban farming’s potential in education, conservation, and as a means of fostering a connection between city residents and the food they eat—even if only on a small scale.

Start-ups like Square Roots tout the nearby nature of container farms: Produce can be grown on the outskirts of town instead of in the Arizona desert or California’s Central Valley. That’s part of the sustainability pitch: Container farming cuts down on emissions from transportation. But the great white lie of the local food movement is that the carbon emissions from trucking foods from there to here represent a small slice of agriculture’s overall climate footprint. The Environmental Protection Agency put ag at 9 percent of the nation’s overall emissions in 2014, with livestock and farmland management two of the major contributors.

With their highly efficient use of space, container gardens can do the work of a lot of farmland in exceptionally few square feet. According to Musk’s announcement, one shipping container can produce the same amount of greens or herbs as two acres of farmland—land that, if taken out of production, could be used to capture carbon rather than emitting it.

While container farms are highly efficient when it comes to space, the same cannot be said for their energy use. A 2015 study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health sought to determine whether hydroponics were “a suitable and more sustainable alternative” to conventional lettuce farming in Yuma, Arizona, which today is better known for romaine than for train robberies. While the researchers found that hydroponics outperformed traditional field-grown lettuce production in terms of land and water use, the same could not be said for energy use. Between cooling in the summer, heating in the winter, and the energy required for 24-hour lighting, hydroponic operations have high electricity demands. As the authors of the paper concluded, “Due to the high energy demands, at this time, commercial hydroponics is not a suitable alternative to conventional lettuce production in Yuma, Arizona.”

The Johns Hopkins report on urban farming, which reviewed prior research on various types of city-based ag, found similar evidence, and the authors wrote that “producing food in urban settings may increase GHG emissions and water use if plants are grown in energy- and resource-intensive operations, such as indoor/vertical farming, greenhouses, hydroponics (soilless crop production), or aquaculture (the cultivation of aquatic animals or plants for food) facilities in cold or water-scarce regions.”

Both geography and technology could mitigate the energy problem of indoor ag, as the authors noted. Renewable energy could help to offset the energy demand for heating and cooling. Building hydroponics infrastructure in a milder climate could limit the amount of cooling and heating needed throughout the year. Even if the energy issue presents a problem with indoor farming as it exists today, the researchers pointed out that the technology “provides promising concepts that could lead to more sustainable food production.”

Technology could also help to make conventional lettuce farms more efficient from a water-use standpoint. The paper noted that hydroponics are able to use less water than field-grown lettuce not because each plant needs less water when grown indoors but because highly controlled indoor farms can outperform inefficient irrigation technology. Lettuce has shallow roots “but is primarily irrigated through flood furrow irrigation in southwestern Arizona,” the authors wrote, which is also the case in California. “Water not quickly absorbed by the roots is lost to percolation. Increases in the use of low-flow and more-targeted irrigation techniques could lower the overall water use of conventional farming.”

Would a venture capitalist plow money into improving existing ag technologies? It seems unlikely during an era when the tech industry fetishizes so-called disruptive companies. Why make a better irrigation system—or invest in one—when there are more innovative ideas like shrinking down the outmoded American farm, stuffing it in a repurposed shipping container, and dropping it in an old factory in gentrified Brooklyn? CNBC does not write about irrigation companies as a “hot new area for investors,” that’s for sure.

There’s the question of what can be grown in container farms too. AeroFarms grows greens and herbs; FarmedHere grows greens and herbs. Square Roots will grow greens and herbs. Spread, a Japanese indoor-farming company that promises to go fully robotic next year, will increase its daily yield to 50,000 heads of lettuce a day, thanks to its robot workforce.

Square Roots is working with two indoor-farming start-ups, Freight Farms and ZipGrow, for the incubator farms. Freight Farms will supply the shipping containers; ZipGrow will provide the vertical-farming towers. Freight Farms calls its farm-in-a-box containers Leafy Green Machines and recommends growing lettuces, herbs, and brassicas such as kale, chard, and arugula. ZipGrow’s “recommended go-to-market crops” are greens, herbs, and flowers.

That’s a lot of lettuce, kale, and herbs. Matt Matros, the CEO of FarmedHere, which is the largest indoor farm in the country, hopes to someday grow avocados, as he told The Guardian last year, but we aren’t there yet.

The indoor-farming start-ups all offer non-GMO crops, yes—but there are also no commercially produced genetically modified greens or herbs. Any given head of lettuce grown in California or Arizona is non-GMO.

Entrepreneurs have to start somewhere. Remember when Amazon only sold books? Even if container farms can’t move past herbs and greens, if Musk and Peggs’ incubator floods the market with kale-and-lettuce-growing start-ups, those local greens will become that much more affordable.

Take the Pledge: Take Your Place: Become An Anti-Hunger Advocate

Related stories on TakePart:

• Urban Agriculture Can’t Feed Us, but That Doesn’t Mean It’s a Bad Idea

• Can Urban Agriculture Feed the World's Growing Cities?

• Urban Farming Is Now Flying a Flag at Major U.S. Airports

Original article from TakePart

Square Roots Launches Urban Farming Accelerator Using Freight Farms Platform

recently announced that he will be launching a new business in the fall — Square Roots. An urban farming accelerator program focused on training young entrepreneurs to grow non-GMO, fresh, tasty, food year-round, Square Roots will be leveraging the Freight Farms technology to create campuses of climate-controlled, indoor, vertical farms. These campuses will be located in major urban centers across the US starting in the fall.

Square Roots Launches Urban Farming Accelerator Using Freight Farms Platform

Kimbal Musk just recently announced that he will be launching a new business in the fall — Square Roots. An urban farming accelerator program focused on training young entrepreneurs to grow non-GMO, fresh, tasty, food year-round, Square Roots will be leveraging the Freight Farms technology to create campuses of climate-controlled, indoor, vertical farms. These campuses will be located in major urban centers across the US starting in the fall.

The Square Roots team is made up of an incredible group of individuals and network of mentors that will coach each entrepreneur in the program. Their goal is to help facilitate the creation of forward-thinking companies that strengthen communities by bringing local, #realfood to everyone. Pretty awesome, right? We think so too! The first campus is launching this fall in Brooklyn, and they’re looking for their first class of real food entrepreneurs. If you want a chance to work in an LGM and receive guidance from industry experts, be sure to apply.

We’ve always said that our network of farmers brings to life the vision of our company, and this is yet another perfect example. Sure, we build the farms and the software, but ultimately it’s what each farmer does with those farms that makes the true impact. Square Roots is harnessing the Freight Farms platform to bring a larger vision to life, and we’re beyond excited to watch this partnership grow.

If you’d like to hear more about how Freight Farms is helping grow local food ecosystems across the globe, give us a shout!

What the Heck Is… Vertical Farming?

Radical solutions are needed to keep up with our fast-growing world population.

Our weekly series What The Heck Is… sheds light on the strange unexplained acronyms and unfamiliar buzzwords that creep into our everyday lives.

Farming, something humans have been doing for thousands of years, is struggling to adapt to our modern world. Radical solutions are needed to keep up with our fast-growing world population.

What’s wrong with regular farming?

Firstly it’s expensive, both in financial cost and the cost of land required to grow food at scale.

It’s environmentally unfriendly, not just with chemicals and pesticides being poured into the ground, but also the fact that farms only generate a few harvests a year. During winter most of the world’s farmland is simply being wasted.

Plus farming is creating food in the places that we don’t really need it.

More than 50% of the world’s population lives in cities, and this will rise to 80% by 2050, but all the food is being created in rural areas because of the land required to grow at scale.

The result is that transport costs, the environmental impact of transporting this food, and the fact that 30% of all farmed food is wasted because it spoils before it can be eaten, make traditional farming a costly exercise.

So is there a better way?

What the heck is vertical farming?

As its name suggests, vertical farming is a new way of growing of food can be stacked vertically, rather than horizontally, and uses technology to solve the problems with traditional farming.

Think trays of crops stacked in warehouses, with their water, pesticides and even sunlight controlled by a computer, giving them exactly what they need to grow and dramatically boosting the quantity of food produced.

The theory suggests that these vertical farms could even be built inside skyscrapers or existing buildings, creating food where it is needed and reducing the environmental impact of farming.

We say theory, because at the moment that’s exactly what vertical farming is.

AeroFarm hasn't started vertically farming on an industrial scale, yet.

Putting theory into practice

Today there are several vertical farms in the early stages of construction.

In the US, Vertical Harvest based in Jackson, Wyoming, is up-and-running planning to vertically grow 100,000 pounds of vegetables every year.

If they achieve that goal it will offset 3% of the produce currently being shipped into the town.

But it’s early days and they have yet to prove that they can vertical farm this amount of food at such a scale.

AeroFarms in Newark, New Jersey, has even grander goals. The company plans to harvest 2m pounds of veg a year from their 69,000 sq ft warehouse, using 95% less water and 50% less fertiliser than a traditional farm… once production starts in September 2016.

The projects share two things in common:

Neither has proved that they can yet produce the quantity of food they promise, at an acceptable price and with a sustainable business model.

And both are supported by millions of dollars in venture capital investments and government subsidies.

What does it mean for your food shop?

If vertical farming works, the price you pay for food could fall – as transport costs disappear and farming becomes less wasteful – as we enter a new era of locally-sourced food.

Or, the price of your food could skyrocket – if the cost of the technology is passed onto shoppers, or if the efficiencies of vertical farming are never realised.

With millions being spent on vertical farming and dozens of vertical farms coming online over the next few months and years, it won’t be long until we discover if the food of the future will be grown in a warehouse.

Our weekly series What The Heck Is… exists to shed light on the strange unexplained acronyms and unfamiliar buzzwords that creep into our everyday lives.

By Oliver Smith

Old Steel Mill Will Soon Be World's Largest Vertical Farm

Stacks of leafy greens are sprouting inside an old brewery in New Jersey.

NEWARK, N.J. (AP) — Stacks of leafy greens are sprouting inside an old brewery in New Jersey.

On this Thursday, March 24, 2016, file photograph, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, center at podium, addresses a gathering at AeroFarms, a vertical farming operation in Newark, N.J. AeroFarms is now refurbishing an old steel mill in New Jersey and they say it will soon be the site of the world's largest indoor vertical farm. The company says their Newark facility, set to open in September, could produce 2 million pounds of food per year and help with farming land loss and long-term food shortages. (AP Photo/Mel Evans, File)

"What we do is we trick it," said David Rosenberg, co-founder and chief executive officer of AeroFarms. "We get it thinking that, if plants could think: 'All right, this is a good environment, it's time to grow now.'"

AeroFarms is one of several companies creating new ways to grow indoors year-round to solve problems like the drought out West, frost in the South or other unfavorable conditions affecting farmers. The company is in the process of building what an industry group says is the world's largest commercial vertical farm at the site of an old steel mill in New Jersey's largest city.

It will contain 12 layers of growth on 3½ acres, producing 2 million pounds of food per year. Production is set to begin next month.

"We want to help alleviate food deserts, which is a real problem in the United States and around the world," Rosenberg said. "So here, there are areas of Newark that are underprivileged, there is not enough economic development, aren't enough supermarkets. We put this farm in one of those areas."

The farm will be open to community members who want to buy the produce. It also plans to sell the food at local grocery stores.

Critics say the artificial lighting in vertical farms takes up a significant amount of energy that in turn creates carbon emissions.

"If we did decide we were going to grow all of our nation's vegetable crop in the vertical farming systems, the amount of space required, by my calculation, would be tens of thousands of Empire State Buildings," said Stan Cox, the research coordinator at The Land Institute, a nonprofit group that advocates sustainable agriculture.

"Instead of using free sunlight as we've always done to produce food, vertical farms are using light that has to be generated by a power plant somewhere, by electricity from a power plant somewhere, which is an unnecessary use of fuel and generation of carbon emissions."

Cox says that instead of moving food production into cities, the country's 350 million acres of farmland need to be made more sustainable.

But some growers feel agriculture must change to meet the future.

"We are at a major crisis here for our global food system," said Marc Oshima, a co-founder and chief marketing officer for AeroFarms. "We have an increasing population that by the year 2050 we need to feed 9 billion people. We have increasing urbanization."

Rosenberg also pointed out the speeded-up process.

"We grow a plant in about 16 days, what otherwise takes 30 days in the field," he said.

By TED SHAFFREY

Aug. 19, 2016 1:30 AM EDT

Indoor Farms Give Vacant Detroit Buildings New Life

Surplus of vacant buildings a boon for indoor farmers

Indoor Farms Give Vacant Detroit Buildings New Life

Breana Noble , The Detroit News 11:17 a.m. EDT August 16, 2016

Surplus of vacant buildings a boon for indoor farmers

Standing before a shelf of red incised lettuce, Artesian Farms Managing Partner Jeff Adams talks about the indoor vertical farming operation used to produce three types of lettuce and kale at the company in Detroit on Aug. 3, 2016. Brandy Baker, The Detroit New

Entrepreneurs are taking advantage of inexpensive former warehouses and factories in Detroit and transforming them for agricultural use to produce local foods.

There’s a growing movement of using vacant buildings and spaces to produce lettuce, basil and kale, and even experiment with fish farming — year-round.

And the city is considering regulations that could expand indoor agriculture even more.

“Fifteen, 20 years from now, we want people to say, ‘Of course they grow kale in that building,’ ” said Ron Reynolds, co-founder of Green Collar Foods Ltd. It built its first indoor-farming research hub in Eastern Market’s Shed 5 in 2015.

Green Collar Foods mists the bare roots of kale, cilantro and peppers using an aeroponics system under fluorescent lights in its 400-square-foot plastic-encased greenhouse. The system is built vertically, stacking plants on shelves to grow above each other. Supino Pizzeria in the Eastern Market buys its kale.

It’s one piece of Detroit’s growing urban agriculture scene. Although the city lost about a quarter of its population between 2000 and 2010, community gardens flourished from fewer than 100 in 2004 to around 1,400 today, according to Keep Growing Detroit.

In response, Detroit adopted a zoning ordinance in 2013 to legalize urban farming that was popping up all over the city. The urban agriculture ordinance, however, assumes indoor farming would be large-scale, said city planner Kathryn Underwood. To increase the zoning district, the City Planning Commission sent an amendment to the City Council for consideration that would take into account smaller operations. It is expected to vote on the proposal in the fall.

“(The amendment) recognizes (indoor farming) can happen at very large scales and very small scales,” Underwood said. “It will allow more of it to happen.”

There’s space for it. In 2014, Detroit had more than 78,000 vacant buildings, according to a blight task force survey.

That’s what Green Collar Foods found attractive about Detroit, co-founder Frank Gublo said. Several Detroit and Flint entrepreneurs are interested in working with Green Collar to create farms in 7,000-square-feet indoor spaces.

Green Collar’s Reynolds envisions franchised operations in unused buildings. “It creates a business in an area that is struggling to find businesses to locate in,” he said.

Less water, longer shelf life

Since 2013, at least three other indoor farms have opened in Detroit.

Jeff Adams started planting in 2015 at his Artesian Farms located inside a 7,500-square-foot former vacant warehouse in the Brightmoor district. He uses stacked growing beds and hydroponics to grow lettuce, kale and basil. The hydroponic system replaces soil with nutrient-filled water.

Adams said the kale sells competitively for around $4 for 5 ounces at retailers in Metro Detroit, including Busch’s and Whole Foods Market.

He said his farm has advantages over traditional growers. California farms use seven gallons of water to grow a bundle of lettuce, while his system uses three-tenths of a gallon. Growing locally also extends shelf life.

Artesian Farms, located in a 7,500-square-foot former warehouse in the Brightmoor district, uses stacked growing beds and hydroponics to grow lettuce, kale and basil. (Photo: Brandy Baker / The Detroit News)

“The food you’re eating right now, it’s seven to 10 days before it reaches Michigan,” Adams said. “(Artesian Farms’ produce) is from here to the market in a day, at most, 48 hours. ... It’s going to be much more flavorful and much more nutritional.”

Although the lights feeding his plants suck electricity, Adams is replacing them with purple LEDs, which use 40 percent less power.

That’s important for the future: Adams has five plant racks — one recently produced 95 pounds of lettuce in 36 square feet. By September, he expects to have 11 racks; by November, 26 racks; and in one year, 46 racks of lettuce, kale, spinach, arugula and bok choy. He plans to add five people to his team of two, including himself, by the end of the year — and another three when all stations are installed.

“The whole purpose of this was to employ people, and you can’t employ people if you’re going to be doing it four months out of the year,” Adams said. “If you want to farm all year-round, this is the way to do it.”

Start-up already plans to expand

Eden Urban Farms harvested its first batch of hydroponic lettuce earlier this year.

After researching indoor farmers in the Netherlands, CEO Kimberly Buffington started a pilot farm with four trays of plants, one producing 170 bundles of lettuce. Eden has grown herbs, lettuce, peppers and strawberries.

The company, which now resides in the basement of a business partner’s Milford home, will expand in the next two years to a 31,000-square-foot rental space at 1800 18th St. on the border of Corktown and Mexicantown. Eden has two employees and plans to hire five or six by year’s end. Once in full operation, Buffington expects to employ about 70. Her team is also developing a small-scale system for entrepreneurs.

Eden Urban Farms sells produce at markets and restaurants. Its basil goes at market price between $1.99 and $2.29 for three-quarter ounces, Buffington said. Herbs and peppers are the most profitable.

“We know that the model works,” she said. “If we want to be in business, we have to be competitive.”

Employing people was the goal

Central Detroit Christian Farm and Fishery opened in 2013, taking over a former food market at Second and Philadelphia when the owner donated it after struggling to sell the 3,200-square-foot facility.

The farm used a closed-loop aquaponic system. Tilapia swam in large tanks of water, and the fish-excrement wastewater was pumped through a dirt-and-earthworm filter. The water then flowed through sprinkler heads to the plants as a natural fertilizer, before cycling into the fish tanks again.

But like regular farming, indoor farming has challenges: A review six months ago found keeping the water at the ideal 75 degrees for the tilapia cost too much, said operations director Randy Walker. Fish had to sell at $8 per pound, above the $3 per pound Asian-raised tilapia at supermarkets.

“There’s a future in it, but the technology hasn’t caught up yet,” Walker said. “Everybody says they want it, but when it comes to putting the money down for it, they don’t buy local.”

The indoor farm now grows tomato and pepper starter plants under the lights formerly used for the aquaponic system to sell at Central Detroit Christian’s Peaches and Greens produce market.

“I think they found their stride,” Walker said. “We were employing people, that was the goal. We were educating people and producing food. We met our goal.”

bnoble@detroitnews.com

(313) 222-2032

Twitter: @RightandNoble

In Cold Wyoming Winters, A New Vertical Farm Keeps Fresh Produce Local

Now that Vertical Harvest is up and running, in frigid December, the tomatoes come from next door, instead of being trucked from Mexico

In Cold Wyoming Winters, A New Vertical Farm Keeps Fresh Produce Local

Now that Vertical Harvest is up and running, in frigid December, the tomatoes come from next door, instead of being trucked from Mexico.

Benjamin Graham 08.15.16 6:00 AM

Winters are notoriously harsh in Jackson, Wyoming, where temperatures can plunge far below zero and snowstorms regularly pummel the surrounding mountains. The conditions make for world-class skiing, but they aren’t necessarily conducive to growing heirloom tomatoes.

"The power here is using a small amount of land to serve a community."

As a result, the majority of vegetables consumed on dinner plates in this remote resort town have to be shipped in through steep canyons or over mountain passes, from locales as far afield as Florida, California, and Mexico. But a new vertical farming experiment in the heart of downtown is poised to turn that equation on its head, at least in part.

A group of architects, farmers, and municipal officials have come together to build a startup greenhouse, called Vertical Harvest, on a narrow strip of land next to a public parking garage. Conceived in 2009, the project took years of planning to get off the ground. Its first seeds were planted earlier this year.

If all goes according to plan, the three-story greenhouse will be harvesting more than 100,000 pounds of fresh, locally grown veggies annually. The founders of the greenhouse estimate it will offset 3% of the produce that currently has to be shipped into the valley. That kind of output, taking place on a tenth of an acre, would equate to the production of five acres of traditional agricultural land. "The power here is using a small amount of land to serve a community," says Vertical Harvest cofounder Nona Yehia.

By many accounts, it's working. On the top floor of the greenhouse, clusters of ruby red tomatoes already dangle from vines that hang near the ceiling. One story below, workers tend to trays of baby basil and sunflower cress basking in the warm glow of LED lights. In the background, bins of arugula are transported on conveyor belts across the width of the greenhouse and up and down its south-facing glass facade, feeding the plants on a combination of natural and artificial light.

Crops—which run the gamut from butterhead lettuce to sugar pea cress—are now being harvested each day and sold to grocery stores, local restaurants, and residents of the 10,000-person town.

Vertical Harvest is on the leading edge of a wave of multi-storied farming operations cropping up across the globe. In New Jersey, a company called AeroFarms is building a 70,000-square-foot farm in an old steel mill. Indoor farms have even taken hold in Alaska, where aspiring entrepreneurs are growing vegetables in shipping containers.

"The worst thing that could happen to Vertical Harvest is that it’s a one-off. The vision of the project would be that other communities could benefit from the work we’re doing here."

They all share a common goal: to produce more food on less land in a more controlled environment, all in a location that is closer to consumers.

"An outdoor farmer can control nothing," or at least very little, says Dickson Despommier, emeritus professor of public health and microbiology at Columbia University and author of the book The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century and one of the most vocal proponents of vertical farming over the last decade.

Traditional farms are reliant on the whims of Mother Nature for things like temperature, precipitation, and sunlight. In vertical farms, nearly everything can be controlled, he says. That can translate to a 365-day growing season free of droughts and freezes.

At Vertical Harvest, for example, crops are grown hydroponically, meaning the roots of the plant sit in water infused with the nutrients needed to help plants grow. No soil is used, and the amount of water and fertilizer needed to grow nutritious crops is minuscule compared to traditional agriculture.

"You have the option of 95% survival of whatever you plant," Despommier says. "The best farms in America are 70%. Not only that, you can grow things year-round."

All of those benefits combine to create an industry that has some significant upside, and a few investors appear to be taking note. Partners in the AeroFarms project in New Jersey include Goldman Sachs and Prudential Financial.

But the potential profits of industrial-scale farming are not what the founders of Vertical Harvest are after. Instead, they are trying to build a model for community-based vertical farming, one that they believe will be replicable elsewhere.

You have the option of 95% survival of whatever you plant. The best farms in America are 70%."

The business is registered as a "low-profit" limited liability company, or L3C, meaning Vertical Harvest has stated social goals outside of simply maximizing income.

One of those is to help Jackson’s developmentally disabled residents by providing employment. Fifteen people with a variety of intellectual and physical disabilities share 140 hours of work each week. The greenhouse employs five additional people who oversee the small workforce and the hydroponic growing system.

Vertical Harvest also has been designed as a public space, at least partially. The ground floor serves as a community gathering area. On one side is a market, where anyone can walk in and buy fresh produce. Another section is quartered off as a "living classroom," where a small number of crops are grown for educational initiatives.

"The worst thing that could happen to Vertical Harvest is that it’s a one-off," Yehia says. "The vision of the project would be that other communities could benefit from the work we’re doing here."

The greenhouse was made possible through a partnership with the town of Jackson, which provided the land and backed a $1.5 million state grant that was eventually awarded to Vertical Harvest. As a result, the town owns the greenhouse structure, while Yehia operates the business. All told, the greenhouse cost $3.8 million, with the balance coming from investors, donations, and debt.

In land-scarce Jackson, the partnerships were integral to getting the project done. Ninety-seven percent of land in the county is public. The scarcity works to drive up prices, making the town’s contribution vital. To break even, Vertical Harvest plans to lean heavily on selling high-value "microgreens," which are harvested just days after seeding and are highly sought after by fine-dining chefs.

But before city council members agreed to the project, they wanted some questions answered about energy efficiency. They weren’t convinced that growing tomatoes in winter would be less carbon-intensive than trucking them in from far away. They also had questions about the business model. If Vertical Harvest were to go under, the town would be stuck owning a greenhouse.

So, near the onset of the project, Yehia and her partners had a feasibility study done that found a greenhouse could work in Jackson. They also hired a specialty engineering firm, Larssen Ltd., which has built profitable greenhouses in other extreme climes, such as Siberia. All five members of the city council ended up getting on board.

"In terms of preparing the world for climate change, it’s a good way to make cities more resilient."

In the end, Yehia and other vertical farming experts say they don’t necessarily view the industry as a silver bullet for the future of global food production. At this point, growing certain things, such as fruit trees or root vegetables, just isn’t economical in vertical farms, says Andrew Blume, North America regional manager of the Association for Vertical Farming.

But he and others do view the nascent practice as a sustainable way to supplement the existing food industry. "In terms of preparing the world for climate change, it’s a good way to make cities more resilient," Blume says. It helps democratize the food production process by bringing it closer to consumers.

Vertical farms also help create green jobs and promote food transparency. When a new greenhouse pops up in a community, residents are apt to learn more about what they are eating and where it comes from. That, in turn, says Blume, can help communities become healthier.

Benjamin Graham is a writer in Jackson, Wyoming.

Farms Grow Up: Why Vertical Farming May Be Our Future

This is the dream of vertical farming.

The towering structures that fill urban skylines across the world could soon be filled with people and farm equipment. This is the dream of vertical farming.

Vertical farms can take a wide range of forms. The connecting feature of these innovative agriculture centers is their ability to grow food without using a lot of land. They accomplish this generally by growing food in stackable trays or on various growing levels within a vertical structure. While these growing centers can be built almost anywhere, many enthusiasts imagine them sprouting up in urban centers as either self-contained structures or even integrated into office and residential buildings.

Advanced vertical farm designs combine greenhouse agriculture, renewable energy, and hydroponics to provide cities locally based agriculture centers.

Elements of this futuristic vision are already a reality in the United States, the Middle East, Asia and Europe.

The birth of modern vertical farms

Ecologist and Columbia University Professor Dickson Despommier is most often credited with creating the modern vertical farm movement. After working on the concept for years, Despommier’s ideas entered the mainstream when he published The Vertical Farm Feeding the World in the 21st Century in 2011. This book helped fuel interest and development in vertical farms, but, as he explains in the video below, practical vertical farms are going to look more like complex greenhouses than the fantastical designs put forward by young innovators.

The argument for vertical farming

“The human population is expected to rise to at least 8.6 billion, requiring an additional 109 hectares to feed them using current technologies, or roughly the size of Brazil, Despommier said in an essay on vertical farming. “That quantity of additional arable land is simply not available.”

Despommier believes building up is the only solution.

Read More: Ugly Fruits and Vegetable Might Be the Answer to Zero Food Waste

Other advocates of vertical farming cite a broader set of benefits, ranging from year-round production, to reduced pesticide use, to less pollution from shorter distribution lines when growing centers are located within the populations they feed.

It’s important to note that there are skeptics who refute Despommier’s claims that the planet is running out of usable farmland as well as the sustainability of vertical farms. Despite these objections, a global industry has developed around vertical farming.

How it works

Vertical farming must get creative to duplicate traditional agriculture in non-traditional spaces.

Companies use a wide range of solutions from rotating crops to face the sun (like the Sky Greens approach mentioned below), to reflecting sunlight onto each level of the farm, to special LED lighting systems that replace sunlight.

Vertical farming can actually create more food than traditional farming by growing food hydroponically. This method uses substantially less water and, because it’s enclosed, is less vulnerable to bugs and disease. And soil alternatives like pumicemake the growing environment much more flexible and efficient, as well as less ecologically damaging to set up.

Read More: 7 Myths About GMOs That Actually Aren’t True

Does it work?

Vertical farms are already in use in a wide variety of places like the US, Oman, and Singapore. Current examples are more in the “advanced greenhouse” variety that Despommier referenced in his video, but there are a few companies putting more futuristic designs into practice.

Here’s a look at a few of the vertical farms already changing agriculture.

Podponics, (USA, Dubai, Oman)

The advanced greenhouse company, Podponics, started in Atlanta, Georgia, in the United States. Their system uses recycled shipping containers to create stackable, modular greenhouses. The company estimates each shipping container produces the same yield as an acre of traditional farmland. The company has raised millions in startup capital and runs projects in Atlanta, Dubai, and Oman.

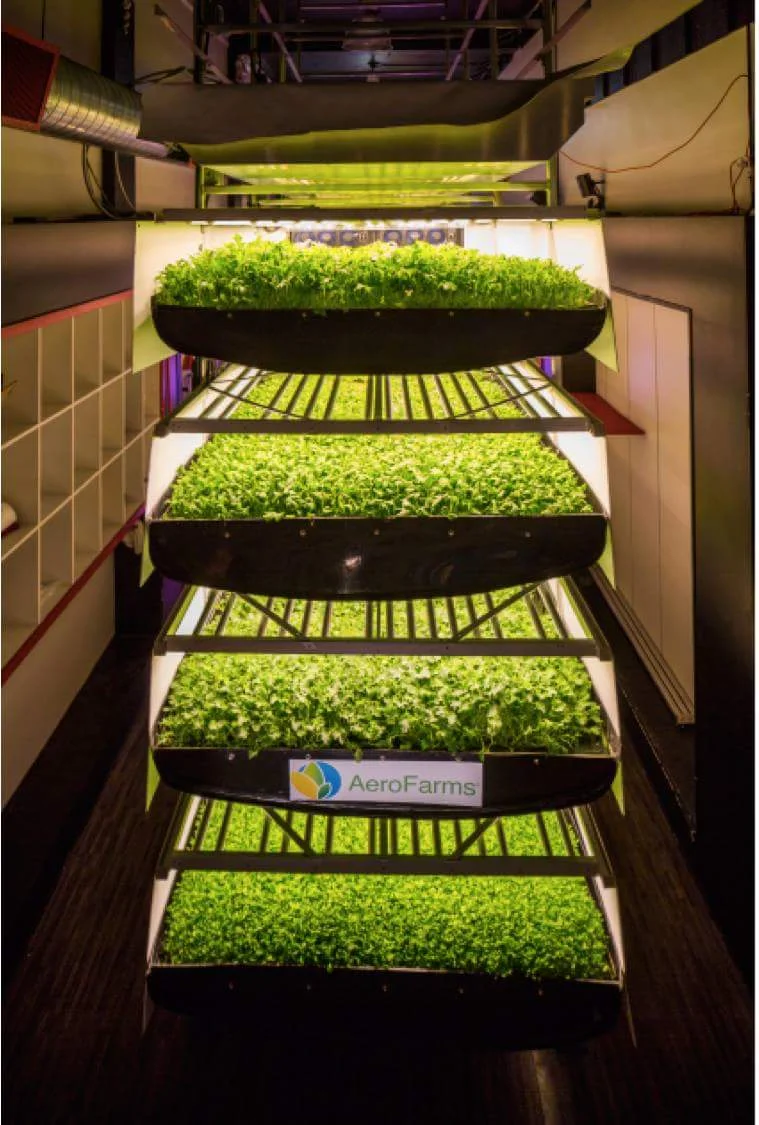

Aerofarms (USA)

Image: Aerofarms

The world’s largest vertical farm is now located in Newark, NJ, in the United States. Startup Aerofarms converted a steel factory into a 69,000-square foot agriculture center that opened earlier this year.

The urban farm produces as much as 2-million pounds of leafy greens a year through a new growing system called “aeroponics,” which does not use direct sunlight or soil to deliver nutrients. It nourishes the plants with special LED lighting and delivers nutrients to plant roots through a liquid mist. The trays can be seen in the image below.

Their lettuces are already available in stores across New Jersey.

Plantagon (Sweden)

Image: Plantagon Mockup

A Swedish company, Plantagon, is one of the leaders in bringing agriculture into urban settings. The company sells conversion kits for existing buildings interested in adding greenhouse growing pods to their interior or exterior spaces. Next, the company intends to create the world’s first true “mixed use” building with both offices and agriculture centers in the same structure.

Read More: Don't Buy These 6 Foods If You Care About Humanity

The company currently runs a geodesic dome known as the “Plantscraper” in Linkoping, Sweden (pictured above). The dome has allowed the company to experiment with different technologies as they design their full mixed-use building also intended to be in Linkoping. In the video below, Plantagon outlines the vision for this first-of-its-kind space.

Sky Greens (Singapore)

Built by Sky Urban Solutions, the Sky Greens vertical farm is the “world’s first low-carbon, hydraulic-driven vertical farm,” according to its website. The farm’s major innovation is a system that rotates hydroponic trays so each is regularly exposed to natural sunlight, reducing the need for costly lighting systems.

Sky Urban Solutions is planning a much larger urban agricultural initiative for the small island nation it calls home. The company wants to build the SG100 Agripolis, a farm and research center that could provide 30% of Singapore’s green leafy vegetable needs. The proposed project has the backing of Singapore’s government because it would promote national food security and resiliency. The video below provides an overview of the venture.

The future of farming

It’s not clear if vertical farming will save the planet, but the early international experiments do seem to show it will be part of the world’s agricultural systems.

By Brandon Blackburn-Dwyer

Futuristic Japanese Indoor Vertical Farm Produces 12,000 Heads of Lettuce a Day with LED Lighting

Philips Lighting has launched the latest in its indoor vertical farming experiments, with trials at two Japanese facilities.

Philips Lighting has launched the latest in its indoor vertical farming experiments, with trials at two Japanese facilities—with one growing 12,000 heads of lettuce a day under horticultural LED lighting technology. Indoor farming is a growing trend in urban centers, where farmland is not prevalent. A wide variety of herbs and greens can be cultivated in climate-controlled environments under LED lighting, for an energy efficient food production method that connects local folks to freshly grown produce.

The two trial farms in Japan demonstrate the awesome potential of indoor urban farming efforts.

Innovatus’ Fuji Farm in Shizuoka Prefecture is an almost 20,000 square foot facility where farmers have spent the past 14 months growing five different varieties of lettuce. Now, the farm harvests 12,000 heads a day that are mainly frilled lettuce, green leaf, and romaine. The efficient vertical farm setup saves not only land and energy, but also water, and Fuji Farm’s harvests can be picked, packaged, and on store shelves in under two hours.

At Delicious Cook’s urban farm in Narashino City in the Chiba Prefecture, an enticing selection of edible herbs are grown under Philips LED lighting. There, farmers have been experimenting with less common varieties of herbs, including edible chrysanthemums and coriander, with great success. In a space smaller than many urban apartments (around 860 square feet), the farm recently completed a 10-month trial in which these unusual herbs were grown under Philips GreenPower LED system. The resulting crops will be used in the company’s processed food products.

One of the key advantages of Philips Lighting horticultural LED systems is the “recipes” used to cultivate specific crops. Farmers are able to set the precise combinations of light, temperature, and humidity level for optimal production of each type of plant. Philips makes the job of urban farmers even easier by developing specific light recipes for various crops, which dictate light spectrum, intensity, illumination moment, uniformity, and positioning. Using this approach, crop yields skyrocket, with consistent quality and flavor, all without daylight.

Images via Philips Lighting

By Cat DiStasio

Indoor Farms of America Announces Manufacturing License Agreement For GrowTrucks Product Line, Multiple Sales

"We are excited to team with Tiger Corner Farms as we expand our reach into the Southeast region of the United States"

Indoor Farms of America Announces Manufacturing License Agreement For GrowTrucks Product Line, Multiple Sales

News provided by

Aug 08, 2016, 13:36

LAS VEGAS, Aug. 8, 2016 /PRNewswire/ -- Indoor Farms of America is very pleased to announce today the completion of a licensing agreement with Tiger Corner Farms, located in Charleston, South Carolina for assembly of their GrowTrucks product line covering the Southeast region of the U.S. to facilitate the growing demand for the GrowTrucks containerized vertical aeroponic farms.

"We are excited to team with Tiger Corner Farms as we expand our reach into the Southeast region of the United States," stated David Martin, CEO of Indoor Farms of America. "After purchasing a container farm from us this Spring, they realized our innovation in indoor agriculture is far ahead of anything else in the marketplace, and wanted to expand their relationship with us, and so we reached agreement for Tiger Corner Farms to be our exclusive representative in 7 states along the eastern seaboard, from Virginia to Florida, and including Alabama and Tennessee."

Don Taylor, founder of Tiger Corner Farms, with a long career in logistics management and innovative software development, stated: "When we met Dave at Indoor AgCon in April, we knew right away the vertical aeroponic technology and overall farm platform developed by Dave and Ron had fantastic potential. A visit to their showroom in Las Vegas sealed it for us."

"Part of our plans include bringing ultra fresh, natural and locally grown produce into the neighborhoods that need it most here in our region," says Stefanie Swackhamer, general manager at Tiger Corner Farms. "Dave is working closely with us to ensure our farm becomes a success, and we are excited to be the new manufacturing partner to serve this region with this amazing farming equipment."

The first GrowTruck to hit South Carolina was the Wheelchair Accessible model, which holds 4,550 plants in a 40' container, and is fully operable by someone in a wheelchair. According to Ron Evans, President of Indoor Farms of America, "This was an emotional one for us. We know that thousands of people can benefit from having the ability to be actively involved in running a commercial farm, who never before would have had this type of opportunity."

Part of the commitment from Tiger Corner Farms was the purchase of 10 farms to get started in the region. "We believe there is a real need for these containerized farm platforms in many areas that simply do not get truly fresh produce, especially locally grown produce, on anything resembling a regular basis, and we are gearing up to make it happen," says Don Taylor. Taylor added, "These farms are really pretty easy to operate, and have growing capacity that makes economic sense, above anything else on the market."

"This alliance with quality folks such as Don and his team add to our overall build capacity to satisfy growing demand for our products, and reduce shipping costs to customers in a large region, which makes sense for us as we execute on our plans to bring the best end to end indoor farm solutions to the marketplace across the U.S. and internationally," added Martin.

Indoor Farms of America Contact:

David W. Martin, CEO | Email | IndoorFarmsAmerica.com

4020 W. Ali Baba Lane, Ste. BLas Vegas, NV 89118

(702) 664-1236or (888) 603-7866

Southeast Regional Representative:

Tiger Corner Farms

Stefanie Swackhamer, General Manager

Email | Phone: 843-323-6521

Could This Glass-Enclosed Farm/Condo Grow on Rem Koolhaas’ High Line Site?

From multidisciplinary architectural firm Weston Baker Creative comes this vision of glass, grass and sass in the form of a mixed-use high-rise springing from the Rem Koolhaas parcel along Tenth Avenue and West 18th Street on banks of the High Line

Could This Glass-Enclosed Farm/Condo Grow on Rem Koolhaas’ High Line Site?

Posted On Fri, August 5, 2016 By Michelle Cohen

From multidisciplinary architectural firm Weston Baker Creative comes this vision of glass, grass and sass in the form of a mixed-use high-rise springing from the Rem Koolhaas parcel along Tenth Avenue and West 18th Street on banks of the High Line. As CityRealty reported, the mixed-use concept would include residences, an art gallery and ten levels of indoor farming terraces. The 12-story structure would rise from a grassy plaza, with the tower’s concrete base meeting the High Line walkway in a full-floor, glass-enclosed gallery that would sit at eye level with the park.

The tower’s form is driven by sunlight, similar to Jeanne Gang‘s “Solar Carve Tower” planned for the Meatpacking District. From Weston Baker’s page: “As the sun comes across the sky to the west, the building twists to evenly distribute daylight throughout the day.” On the southern elevation an enclosed atrium would hold 10 sets of farming terraces on view for High Line visitors and accessible to building residents. There would also be a public “observation garden” on the top floor and an art gallery on the second floor, also accessible from the High Line.

Given the building’s fantastical form, West Chelsea‘s zoning guidelines, the amount of public space and the fact the the High Line prohibits direct access to adjacent private properties, the building likely exists only in the conceptual realm at the moment, but it’s definitely a space to watch. In 2015, the New York Post reported that Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas of Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) will design a project at the site, which had been recently purchased by luxury development firm Related Companies.

UK’s First Vertical Farm To Be Built In Scotland

They have the ability to grow crops in quick time, without the need for vast amounts of land, water or sunshine

UK’s First Vertical Farm To Be Built In Scotland

ALISON CAMPSIE

They have the ability to grow crops in quick time, without the need for vast amounts of land, water or sunshine.

Now the first vertical farm of its type in the UK is to be built in Scotland following a £2.5 million investment from the James Hutton Institute and Intelligent Growth Solutions (IGS).

Lettuce, baby leaf vegetables and microgreens are to be planted in the high-tech growing house near Invergowrie as part of a research project into how vertical farms can best produce crops for Scotland and beyond.

The method is being championed around the world –particularly in urban centres in the US as a way to grow food in small spaces without the need to transport the produce over long distances.

Crops are typically grown under LED lights with hydroponic systems using minimum water and no soil.

IGS predicts costs – such as those generated by lighting –will fall quickly to allow crops such as strawberries and tomatoes to be grown.

Henry Aykroyd, chief executive of IGS with 30 years experience in large-scale farming in the UK, Eastern Europe and California, said: “Our mission is to enable our customers to be the lowest cost producers by growing local globally, with better quality and saving natural resources. The process uses little water, no pesticides, can enhance taste and is consistent all year round.”

The Invergowrie farm will be the first in the UK to be built using automated towers which can respond to peaks and troughs of energy use.

Mr Aykroyd said: “Our real-time software can ‘grab’ power when the grid has surplus power and ‘shut down’ at peak times.

“Our automated growth towers are fully programmable to suit many diverse crops, and provide smart solutions to automation, power management and lighting issues,” he added.

Perth and Kinross Council has granted approval for the project with a 10-year lease now signed by the James Hutton Institute and IGS.

Professor Colin Campbell, Chief Executive of the James Hutton Institute, said: “We are doing more research with such innovative companies in the private sector and this example combines our knowledge of plant science and specialised infrastructure to work with others whose vision is aligned to help solve the challenges around long-term food security.”

FreshBox Farms Now Non-GMO Project Certified

FreshBox Farms greens are now non-GMO certified.

MILLIS — FreshBox Farms greens are now non-GMO certified.

The vertical farm’s entire product line, while always free of genetically modified organisms, is now Non-GMO Project verified. The Non-GMO Project supports providing consumers with clearly labeled non-GMO food and products, and is North America’s only independent verification for products made according to best practices for GMO avoidance.

FreshBox Farms uses controlled environment hydroponics to create perfect produce, thanks to the latest controlled environment agriculture technology. The growing system uses no soil, very little water, controlled light and a rigorously tested nutrient mix created by plant scientists on staff to produce the freshest, cleanest, tastiest produce possible.

Certification includes required ongoing testing of at-risk ingredients, rigorous traceability and segregation practices to ensure ingredient integrity and thorough reviews of ingredient specification sheets to determine the absence of GMO risk. Verification is maintained through an annual audit, along with on-site inspections for high-risk products. Product packaging will include the Non-GMO Project logo within a few weeks.

FreshBox Farms also recently announced a major expansion that will help the Massachusetts-based vertical farm stay on track to become one of the nation’s largest modular hydroponic growers. The sustainable hydroponic farm will increase its capacity by 70 percent, to about 40,000 square feet of indoor growing space.

The expansion, set to be completed in September, comes in response to growing demand through its new direct-to-consumer strategy via partnerships in the region.

How Chicago Became a Leader in Urban Agriculture

From the world’s largest rooftop garden to the country’s biggest indoor aquaponic farm, Chicago is leading the nation in urban food production. Here’s why this is happening

How Chicago Became a Leader in Urban Agriculture

From the world’s largest rooftop garden to the country’s biggest indoor aquaponic farm, Chicago is leading the nation in urban food production. Here’s why this is happening.

July 28, 2016

In the 1830s, when Chicago was becoming established as a city, a new motto was also created: “urbs in horto,” Latin for “city in a garden.”

Chicago became a city in a garden during World War II with the victory garden movement. With 250,000 home gardens and 1,500 community farms, Chicago led the nation as an example of successful urban food production.

Today, the city is still living up to its motto as it continues to be an innovative national leader in urban agriculture.

The Chicago Urban Agriculture Mapping Project has listed that there are over 800 growing sites in Chicago. These sites include school and community gardens, orchards, urban agriculture organizations, protected habitats, and more.

The city also boasts numerous urban agriculture startups, the world’s largest rooftop farm, and the nation’s largest indoor aquaponic farm in nearby Bedford Park.

Urban agriculture’s success in Chicago can be attributed to a number of factors including the amount of vacant space, progressive land zoning policies, an increased demand for locally grown food, and the city’s innovative, entrepreneurial spirit.