Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Is Boston The Next Urban Farming Paradise?

The city’s healthy startup culture is contributing to Boston’s rapidly growing reputation as a haven for organic food and urban farming initiatives

The inspiration for Boston-based Freight Farms was launched after co-founders and friends Jon Friedman and Ben McNamara realized that New England currently gets almost 90% of its food from outside the region. Photograph: Freight Farms

Sunday 16 April 2017 10.00 EDT | Oset Babur

For those seeking mild, year-round temperatures and affordable plots of land, Boston, with its long winters and dense population, isn’t the first city that comes to mind.

But graduates of the city’s nearly 35 colleges and universities are contributing to the area’s growing reputation as a haven for startups challenging and transforming age-old industries, from furniture to political fundraising. The city’s strong entrepreneurial spirit, combined with progressive legislation like the passing of Article 89, has also turned Boston into one of the nation’s hubs for urban agriculture.

The inspiration for Freight Farms, an urban farming business headquartered in South Boston, was launched after co-founders and friends Jon Friedman and Ben McNamara realized that New England currently gets almost 90% of its food from outside the region, yet 10-15% of households still report that they don’t have enough to eat. The over reliance on imported produce drove Friedman and McNamara to launch a Kickstarter campaign in 2011 for their farming business, which sells freight containers to would-be farmers, many of whom aren’t necessarily farmers by trade, but are interested in contributing to sustainable living. A Freight Farms container is designed to be largely self sustained, and uses solar energy to provide the majority of electricity required to grow the crops. Julia Pope, who works in farmer education and support at the organization, says people can find the freight containers squeezed between two buildings, in a parking lot, under an overpass, or virtually anywhere in the modern urban terrain.

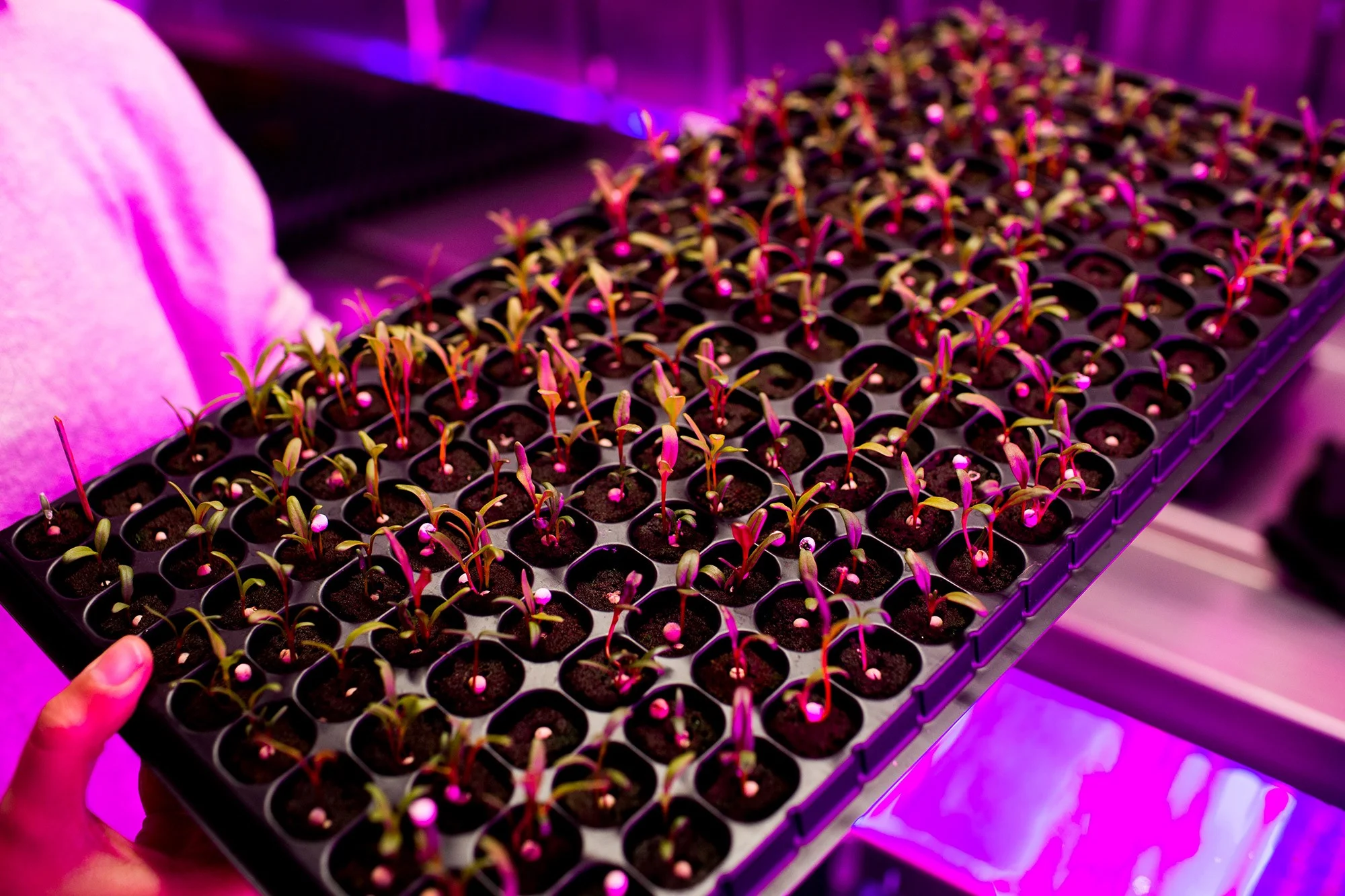

Freight Farms has spread north from Boston to Canada, and Pope says there are over just over 100 of the company’s container farms operating in the US alone. The company outfits each 40-ft container with the equipment for the entire farming cycle, from germination to harvest. This set of equipment, which the company calls Leafy Green Machine (LGM), creates a hydroponic system, a soil-free growing method that uses recirculated water with higher nutrient levels to help plants grow. Vertical growing towers line the inside of the shipping container, with LED lights optimized for each stage of the growing cycle. Farmers can manage conditions remotely using a smartphone app called Farmhand, which connects to live cameras inside the container.

Freight Farms has spread north from Boston to Canada, and Pope says there are over just over 100 of the company’s container farms operating in the US alone. Photograph: Freight Farms

Pope says that of customers who have purchased the LGM, over 50 have started small businesses, each consistently producing two acres worth of food year-round. One of these businesses is Corner Stalk Farm, which sells locally grown leafy greens – including kale, mint and arugula, as well as over twenty varieties of lettuce, to cater to demand at various farmers markets in Boston and Somerville, the city’s landmark Boston Public Market, and through orders from produce delivery services (such as Amazon Fresh) that are increasingly popular in cities. It’s no small feat to own and operate the LGM: purchasing one of the containers will run an aspiring business $85,000, with operating costs adding up to another estimated $13,000 per year.

Luckily, steady consumer demand, evidenced by over 139 farmers markets across the state of Massachusetts alone, help to offset the high costs to starting and running an urban farm. Hannah Brown, a resident of Boston’s North End, regularly shops at the Boston Public Market, which sells locally sourced goods from over thirty small businesses. “There aren’t many stores with really fresh produce in the immediate area, so it’s definitely filled a need for me,” she says. Brown also finds the small business owners who sell their produce at the market to be an invaluable resource: “It’s great to be able to talk with the people working the produce stands, because they can recommend what’s freshest and how to prepare it.” As a result, she says she’s taken to only buying produce that’s in season and adjusting her habits to align with what’s available to her locally.

The growing popularity of urban farming owes much to a former mayor, Thomas Menino, and one of his final acts while in office. He signed into law Article 89, expanded zoning laws to permit farming in freight containers, on rooftops, and in larger ground-level farms. Article 89 made it possible for those practitioners to sell their locally grown food within city limits.

One business that has taken advantage of Article 89 is Green City Growers, which runs Fenway Farms, is a 5,000-sq ft rooftop farm above Fenway Park. The rooftop is lined with plants grown in stackable milk crate containers, which are equipped with a weather sensitive drip irrigation system that monitors the moisture of the soil in the crates to make sure plants get just the right amount of water. Although the farm isn’t open to the general public, it is visible to fans from the baseball park, and a stop on the Fenway Park tour.

In late 2013, the landscape for urban agriculture in Boston got a lot greener with the passing of Article 89, which made it possible for those practitioners to sell their locally grown food within city limits. Photograph: Freight Farms

Boston is far from alone in passing legislation that makes farming a possibility for city-dwellers. In Sacramento, there are even tax incentives for property owners who agree to put their vacant plots of land to active agricultural use for at least five years, while the city council of San Antonio voted just last year to pass legislation that makes urban farming legal throughout city limits. And while Boston boasts home to various agricultural startups and nonprofits, entrepreneurs in other parts of the country are contributing to a national farming movement in their own ways: Kimbal Musk, brother of Tesla and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk, recently set up a container farm in an old Pfizer factory in Brooklyn, while Local Roots Farms is turning shipping containers into urban farms (using the same hydroponic method that the LGM uses) across the Los Angeles area.

As Bostonians now find themselves with a slew of new options to grow and profit from fresh produce on rooftops and in alleyways, some nonprofit organizations are looking to use urban farming as an educational asset. CitySprouts was born in Cambridge in 2001 after executive director Jane Hirschi identified what she calls “an immense need for children to understand where their food was coming from”. CitySprouts teams up with educators to set aside class time for students to cultivate gardens on school property that they can grow their own food in. There are now over 20 public schools using CitySprouts gardens in the Boston area, and more than 300 public school teachers participating in the fresh food program.

Caitlin O’Donnell, who teaches first grade at Fletcher Maynard Academy in nearby Cambridge, says the program does a great job of giving urban kids the opportunity to interact with their environment in ways they wouldn’t have otherwise, she adds. “Whether students are digging for worms, sketching roots structures, crushing apples for cider, or sampling chives and basil, their hands are busy and their senses are engaged ...what makes City Sprouts most effective (and exceptional) is that it is collaborative and flexible by design.”

Boston’s rise in the national urban farming movement also has helped to make locally grown produce more available to low-income residents. Leah Shafer recalls that she was able to use food stamps at a farmer’s market to receive half-off of her purchases of kale, blueberries, and more.

“It made it possible for me to buy organic, local produce that I otherwise just wouldn’t have been able to afford. I don’t think I would have been able to support local farmers without that discount,” she says.

Kimbal Musk's Tech Revolution Starts With Mustard Greens

A leafy green grows in Brooklyn. (Photo by Natalie Keyssar)

The other Musk is leading a band of hipster Brooklyn farmers on a mission to overthrow Big Ag.

Farmers have always had a tough time. They have faced rapacious bankers, destructive pests, catastrophic weather, and relentless pressure to cut prices to serve huge grocery suppliers.

And now they must compete with Brooklyn hipsters. Hipsters with high-tech farms squeezed into 40-foot containers that sit in parking lots and require no soil, and can ignore bad weather and even winter.

Follow Backchannel: Facebook | Twitter

No, the 10 young entrepreneurs of the “urban farming accelerator” Square Roots and their ilk aren’t going to overthrow big agribusiness — yet. Each of them has only the equivalent of a two-acre plot of land, stuffed inside a container truck in a parking lot. And the food they grow is decidedly artisanal, sold to high-end restaurants and office workers who are amenable to snacking on Asian Greens instead of Doritos. But they are indicative of an ag tech movement that’s growing faster than Nebraska corn in July. What’s more, they are only a single degree of separation from world-class disrupters Tesla and SpaceX: Square Roots is co-founded by Kimbal Musk, sibling to Elon and board member of those two visionary tech firms.

Kimbal’s passion is food, specifically “real” food — not tainted by overuse of pesticides or adulterated with sugar or additives. His group of restaurants, named The Kitchen after its Boulder, Colorado, flagship, promotes healthy meals; a sister foundation creates agricultural classrooms that center a teaching curriculum around modular gardens that allow kids to experience and measure the growing process. More recently, he has been on a crusade to change the eating habits of the piggiest American cities, beginning with Memphis.

“This is the dawn of real food,” says Musk. “Food you can trust. Good for the body. Good for farmers.”

Square Roots is an urban farming initiative which allows “entrepreneurs” to grow organic, local vegetables indoors at its new site in Bed Stuy, Brooklyn. (Photo by Natalie Keyssar)

Square Roots is one more attempt to extend the “impact footprint” of The Kitchen, says its CEO and co-founder Tobias Peggs, a longtime friend of Musk’s. (Musk himself is executive chair.) Peggs is a lithe Brit with a doctorate in AI who has periodically been involved in businesses with Musk, along with some other ventures, and wound up working with him on food initiatives. Both he and Musk claim to sense that we’re at a moment when a demand for real food is “not just a Brooklyn hipster food thing,” but rather a national phenomenon rising out of a deep and wide distrust of the industrial food system, a triplet that Peggs enunciates with disdain. People want local food, he says. And when he and Musk talk about this onstage, there are often young people in the audience who agree with them but don’t know how to do something about it. “In tech, if I have an idea for a mobile app, I get a developer in the Ukraine, get an angel investor to give me 100k for showing up, and I launch a company,” Peggs says. “In the world of real food, there’s no easy path.”

The company is headquartered in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant, right next to the Marcy Projects, which were the early stomping grounds of Jay Z. It’s one of over 40 food-related startups housed in a former Pfizer chemicals factory, which at one time produced a good chunk of the nation’s ammonia. (Consider its current role as a hub of crunchy food goodness as a form of penance.) Though Peggs’ office and a communal area and kitchen are in the building, the real action at Square Roots is in the parking lot. That’s where the company has plunked down ten huge shipping containers, the kind you try to swerve around when they’re dragged by honking 18-wheel trucks. These are the farms: $85,000 high-tech growing chambers pre-loaded with sensors, exotic lighting, precision plumbing for irrigation, vertical growing towers, a climate control system, and, now, leafy greens.

Musk and Peggs (center) with the Brooklyn growers. (Photo by Steven Levy)

Each of these containers is tended by an individual entrepreneur, chosen from a call for applicants last summer that drew 500 candidates for the 10 available slots. Musk and Peggs selected the winners by passion and grit as opposed to agricultural acumen. Indeed, the resumes of these urban farmers reveal side gigs like musician, yoga teacher, and Indian dance fanatic. (The company does have a full-time farming expert and other resources to help with the growing stuff.) After all, the idea of Square Roots is not about developing farm technology, but rather about training people to make a business impact by distributing, marketing, and profiting off healthy food. “You can put this business in a box — it’s not complicated,” says Musk. “The really hard part is how to be an entrepreneur.”

Peggs gave me a tour late last year as the first crops were maturing. The farmers themselves were not in attendance. Every season is growing season in the ag tech world, but once you’ve planted and until you harvest, your farms can generally be run on an iPhone, and virtually all the operations are cloud-based. Peggs unlocked the back of a truck and lifted up the sliding door to reveal racks of some sort of leafy greens. Everything was bathed in a hot pink light, making it look like a set of a generic sci-fi movie. (That’s because the plants need only the red-blue part of the color spectrum for photosynthesis.) Also, the baby plants seemed to be growing sideways. “Imagine you’re on a two-dimensional field and you then tip the field on its side and hang the seedlings off,” Peggs says. “That means you’re able to squeeze the equivalent of a two-acre outdoor field inside a 40-foot shipping container.”

Square Roots didn’t have to invent this technology: You can pretty much buy off-the-shelf indoor farming operations. We owe this circumstance to what once was the dominant driver of inside-the-box ag tech: the cultivation of marijuana. The advances concocted by high-end weed wizards are now poised to power a food revolution. “Cannabis is to indoor growing as porn was to the internet,” says Pegg.

Using light, temperature, and other factors easily controlled in the nano-climate of a container farm, it’s even possible to design taste. If you know the conditions in various regions at a given time, you can replicate the flavors of a crop grown at a specific time and place. “If the best basil you ever tasted was in Italy in the summer of 2006, I can recreate that here,” Peggs says.

So far, the Square Roots entrepreneurs haven’t achieved that level of precision—but they have jiggered the controls to make tasty flora. And they’ve used imagination in selling their crops. One business model that’s taken off has the farmers hand-delivering $7 single-portion bags of greens to office workers at their desks, so the buyers can nibble on them during the day, like they would potato chips. Others supply high-end restaurants. Occasionally Square Roots will run its version of a farmer’s market at the Flushing Avenue headquarters or other locations, such as restaurants in off hours.

The prices are higher than you’d find in an average supermarket, or even at Whole Foods. Peggs doesn’t have to reach far for an analogy — the cost of the first Teslas, two-seaters whose six-figure pricetags proved no obstacle for eager buyers. “Think of it as the roadster of lettuce,” he says. Later, Musk himself will elaborate: “The passion the entrepreneurs put into it makes the food taste 10 times better.”

One selling point of the food is its hyperlocal-ness — grown in the neighborhood where it’s consumed. The Square Roots urban growers often transport their harvest not by truck but subway. While this circumstance does piggyback on the recent mania for crops grown in local terroir, I wonder aloud to Peggs whether food produced in a high-tech container in a dense urban neighborhood, even if it’s a few blocks away, has the same appeal as fresh-off-the-farm crops that are grown on actual farms. In, like, dirt. Can you tell by a grape’s taste if it came from Williamsburg or Crown Heights? I’m having a bit of trouble with that.

Peggs brushes off my objection. Local is local. It’s about transparency and connectedness. “Here’s what I know,” he says. “Consumers are disconnected from the food, disconnected from the people who grow it. We’re putting a farm four stops on the subway from SoHo, where you can know your farmer, meet your farmer. You can hang out and see them harvest. So whether the grower is a no-till soil-based rural farmer or a 23-year or dream-big entrepreneur in a refurbished shipping container, both are on the same side, fighting a common enemy, which is the industrial food system.”

Plants grow in Nabeela Lakhani’s container. (Photo by Natalie Keyssar)

Square Roots is far from the only operation signing on to an incipient boom in indoor agriculture. Indeed, ag tech is now a hot field for investors — maybe not so much that founders can get $100k for just showing up, but big enough that some very influential billionaires have ponied up their dollars. I spoke recently to Matt Barnard, the CEO of a company called Plenty. His investors include funds backed by Eric Schmidt and Jeff Bezos. In its test facility in a South San Francisco warehouse, Plenty is developing techniques that it hopes will bring high-tech agriculture to the shelves of the Walmarts of the world.

In Barnard’s view, indoor agriculture is the only way we will feed the billions of new humans predicted to further crowd our planet. “We have no choice,” he says. “We are out of acreage [of productive land] in many places. In the US, the percentage of imported produce keeps growing.”

Going indoors and using technology, he says, will not only give us more food, but also better food, “beyond organic quality.”

As its name implies, Plenty wants to scale into a huge company that will feed millions. Barnard, who previously built technology infrastructure for the likes of Verizon and Comcast, has a vision of hundreds of distribution hubs — think Amazon or Walmart, near every population center, putting perhaps 85 percent of the world’s population within a short drive of a center. Without having to optimize crops so they can be driven thousands of miles from farm to grocery store, almost all food will be local. “We’ll have food for people, not for trucks,” he says. “This enables us to grow from libraries of seeds that have never been grown commercially, that will taste awesome. These will be the strawberries that beforehand, you only got from your grandmother’s yard.”

As far as that goal goes — better-than-organic crops grown near where you consume them — Plenty is aligned with Square Roots. But Barnard insists that the key element in ag tech will be scale. “Growing food inside is the easy part,” says Barnard. The hardest part is to make food that seven billion people can eat, at prices that fit in everybody’s grocery budget.”

Green Acres? Try Pink Acres! Pictured here, Square Roots farms — and in background is Jay Z’s boyhood home, the Marcy Projects. (Photo by Natalie Keyssar)

Peggs and Musk themselves are interested in scale. They see Square Roots as grass roots — seedlings of a movement that will blossom into a profusion of food entrepreneurs who subscribe to their vision of authentic, healthy chow grown locally.

Earlier this year, Musk dropped by Square Roots to show it off to investors and friends, and then to give a pep talk over lunch to the entrepreneurs. Midway through their year at Square Roots, these urban ag tech pioneers were still enthusiastic as they described their wares. Nabeela Lakhani, who studied nutrition and public health at NYU, described how her distinctive variety of spicy mustard greens had gained a local following. “People lose their minds over this,” she says. Electra Jarvis, who hails from the Bronx, has done a land-office business in selling 2.5-ounce packages of her Asian Greens for $7 each to office workers. (That’s almost $50 a pound.) Maxwell Carmack, describing himself as a lover of nature and technology, packages a variety of his “strong spinach.”

After a tour of the parking lot — the 21st century lower forty — the guests leave and Musk schools the farmer-entrepreneurs as they feast on a spread of sandwiches and salads featuring their recently harvested products. It’s a special treat to hear from the cofounder, as he not only has that famous surname, but also is himself a superstar in the healthy food movement, as well as an entrepreneur who’s done well in his own right. And unlike his brother, who can sometime be dour, Kimbal is a social animal who lights up as he engages people on his favorite subjects.

“Are you making money?” he asks them. Most of them nod affirmatively. Only recently, they have discovered that the “Farmer2Office” program — the one that essentially sells tasty rabbit food for caviar prices — can be a big revenue generator, with 40 corporate customers so far. Peggs guesses that by the end of the year some of the farmers might be generating a $100,000-a-year run rate (the entrepreneurs pay operating expenses and share revenue with the company). But of course, because Square Roots is covering the capital costs of the farms themselves, it’s hard to claim they’re reaping huge profits.

Musk, in cowboy hat, gets back to his roots. Peggs is standing behind him. (Photo by Steven Levy)

“It’s a grind building a business,” Musk tells them. “It’s like chewing glass. If you don’t like a glass sandwich, stop right now.” The young ag tech growers stare at him, their forks frozen in mid-air until he continues. “But you choose your destiny, choose the people around you,” Musk continues.

And then he speaks of the opportunity for Square Roots. This year may only be the first of many cycles where he and Peggs pick 10 new farmers. Within a few years, he will have a small army of real-food entrepreneurs, devoted to disrupting the industry with authentic crops, grown locally. “The real problem is how to reach everybody,” he says. “We’re not going to solve that problem at Square Roots. But there are so many ways you can impact the world when you’re out of here.”

“Whole Foods is stuck in bricks and mortar,” he continues. “We can become the Amazon of real food. If not us, one of you guys. But someone is going to solve that problem.”

The urban farmers look energized. Lunch continues. The salad, fresh from the parking lot, is delicious.

Steven LevyFollow

Editor of Backchannel. Also, I write stuff. Apr 14,2017

Creative Art Direction by Redindhi Studio

Photography by Natalie Keyssar / Steven Levy

Lifelong Farmer Looks East: CEA Farms Wants to Bring Indoor Farm to Eastern Loudoun

Don Virts in his hydroponic greenhouse at CEA Farms in Purcellville. CEA stands for Controlled Environment Agriculture, and Virts says it yields much more produce for much less water, fertilizer, and pesticide. (Renss Greene/Loudoun Now)

Lifelong Farmer Looks East: CEA Farms Wants to Bring Indoor Farm to Eastern Loudoun

2017-04-14 Renss Greene 0 Comment

Don Virts is a new type of farmer.

His family has worked the land in Loudoun for generations, growing beef and produce. But things have changed now. The old ways aren’t sustainable for a small farm anymore, especially with Loudoun’s pricey land values.

In fact, according to the United States Department of Agriculture, farm households bringing in less than $350,000 annually make far more from off-farm income. Although the USDA has very broad definitions for what makes a farm. Perhaps more telling, large-scale farms bringing in more than $1 million a year make up only 2.9 percent of farms, but 42 percent of farm production.

Don Virts saw that his family’s farming business wouldn’t survive without adapting, and in 2015 he started one of the county’s first commercial hydroponic greenhouses. There, he says he gets ten times the yield from his plants, year-round, using 50 percent less fertilizer, 50-80 percent less water, 99 percent less pesticide and fungicide, and zero herbicide. He says if he could afford to build a higher-tech greenhouse, he could do away with pesticide and fungicide altogether.

“I have no desire to be certified organic, because I fully believe that this is better than organic,” Virts said. “Anything grown organically outdoors, you throw a lot of stuff on it to control those problems. It might be approved for organic use, but that doesn’t mean it’s safe.” He said that every year, more and more chemical treatments are approved for organic use.

His greenhouse has a much higher up-front cost than a traditional patch of tomatoes, but after that, costs are lower and production is much higher, on a much smaller footprint.

And he says he can do it in Loudoun’s increasingly urbanized east.

“I had to ask myself, what does Loudoun offer that I can take advantage of?” Virts said. “And what it boils down to is, the same thing that’s putting me out of business is going to turn around to be the thing that’s going to keep me in business.”

By that he means Loudoun’s booming, highly educated, high-income population. He says he can’t keep up with the demand at his CEA Farms Market and Grill in Purcellville, and thinks he can set up another one in the east, bringing the produce closer to the consumer.

“What I’m trying to do is place these things all over the place, and then we have these islands of food production,” Virts said. Instead of the traditional model of produce packed and shipped in from far away, even other hemispheres, Virts wants people eating food picked that morning only a stone’s throw away. So far, it’s working at his greenhouse in Purcellville.

“I built this as a proof of concept, so people would come out there and see this, and see I don’t have a crazy vision,” Virts said. “It’s practical.” He said he knows a landowner in eastern Loudoun who is “very interested” providing him space for a growth facility but hasn’t signed a contract yet.

It’s not just an evolution of how food is grown, but an evolution of the business of growing food.

“This is something one small family farmer cannot do by himself,” Virts said. “I don’t have the resources. I don’t know the restaurant business, I don’t know the renewable energy business.”

The USDA calculated that in 2015, for every dollar spent on food, only 8.6 cents went to the farmer. For every dollar spent in a restaurant, only 3 cents went to the farmer.

Source: USDA Economic Research Service

Virts figures that by growing food close to where it’s eaten, using renewable energy, and cutting out middlemen, he can reclaim most of the money spent on food processing, packaging, transportation, wholesale and retail trading, and energy to bring food to the plate. Those account for 47.6 cents every dollar spent on food.

All that may add up to helping offset the high cost of land in eastern Loudoun. It would give consumers certainty about where their food came from.

His idea would also keep almost all the money spent on food in the local economy, and by cutting down on long-distance transportation and using renewable sources of energy, he can do his part to combat global warming. He has a farmer’s practical, pragmatic outlook on that topic—it has made it more difficult for him, with changing weather patterns and more intense storms.

“I’ve witnessed it on this farm,” Virts said. “When I was kid in high school, we used to take our pickup trucks on this pond [on his farm.] I haven’t been able to go ice skating there in years.”

Along with his other ideas—such as a restaurant with tiered seating overlooking his existing greenhouse—Virts is trying out all kinds of ways to make his family farm work.

“At some point, everybody has to wake up and think about this: Could you do your job, could anybody out there do their job, if they were hungry?” Virts said. “And that’s what it all boils down to, so somebody’s got to figure out that these five acres are worth more money in the long run with a self-sustaining business like this, producing something that everybody needs two or three times a day, than to build townhouses or apartments on it.”

Ultimately, if he can get food production up and running somewhere in eastern Loudoun, it will be another proof-of-concept for the future of small scale agriculture.

“As we get bigger and better, as we build our first one,” Virts said, “there’s going to be some lessons learned there.”

First European Vertical Farm To Open in Holland

Soon, the lettuce in your salad may come from a so-called vertical farm. Vertical farming, growing fruit and vegetables in tall buildings without daylight, is on the rise around the globe. This year, the Dutch town Dronten will be home to the first European vertical farm. Staay Food Group is building a nine-story-building, in which their company Fresh Care Convenience will cultivate various types of lettuce

First European Vertical Farm To Open in Holland

News item | 14-04-2017 | 11:56

Soon, the lettuce in your salad may come from a so-called vertical farm. Vertical farming, growing fruit and vegetables in tall buildings without daylight, is on the rise around the globe. This year, the Dutch town Dronten will be home to the first European vertical farm. Staay Food Group is building a nine-story-building, in which their company Fresh Care Convenience will cultivate various types of lettuce.

Lettuce with LED lighting - Image: Staay Food Group

Climate Chambers

Each floor in the flat will have specially designed climate chambers with LED lighting, which will produce 30,000 crops of rucola, lollo bionda, lollo rosso and curly endive a week. That’s twice as many crops as can be grown in traditional farms in a week, at a rate about 3 times as fast.

Staay Food Group is investing 8 million euros in the project. A large part of the costs is for special LED lighting. Philips is developing lights that change colours, to influence the taste and the vitamin count.

The first crops of lettuce will be processed by Fresh Care Conveniencefor ready-to-eat meal salads for the German market. They will hit Dutch supermarkets soon after.

Sustainable

Vertical farming has several advantages and is sustainable. With multiple floors to grow crops, a high-rise has a large surface area in a relatively small space. In a multi-floored building, all crops are sheltered from bad weather and insects, so farmers can grow them without insecticides.

Some vertical farms use a circular system, expanding their business with fish and adding fish farms to the building. The fish excrement is then collected and used to fertilize the vegetables.

The climate chambers in Dronten are energy efficient, using less water, electricity and fertilizer than traditional farming. They aim for CO2 neutral production.

City Farming

The fact that high-rise buildings can be built in city centres is an added benefit. Fresh products can now be grown very close to the consumer. Which answers the increased demand for sustainable, locally grown products.

Faith-Based Organization Alleges Vertical Farm Operator Breached Contract

Faith-Based Organization Alleges Vertical Farm Operator Breached Contract

by Philip Gonzales |

Apr. 12, 2017, 10:23am

CHARLESTON — A faith-based organization is suing a vertical farms operator, alleging breach of contract and conversion.

Kanawha Institute for Social Research & Action Inc filed a complaint March 21 in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia against Green Spirit Farms LLC of New Buffalo, Michigan, alleging failure to fulfill its obligations under the contract.

According to the complaint, on Dec. 22, 2014, the parties entered into a contract, and Green Spirit agreed to develop an initial vertical farm using its vertical growing system. Despite payments totaling $222,830, no multiple vertical growing systems were delivered to the institute and no services in connection with the development of the vertical farm were provided.

The plaintiff alleges Green Spirit Farms has not provided the services and the growing systems, failed to refund the plaintiff's payments as promised and wrongfully retained and exercised dominion over the institute's property.

Kanawha Institute seeks trial by jury, to recover the payments made to the defendant, with interest, punitive and consequential damages, attorney fees and court costs and all other just and equitable relief. It is represented by attorney Mark Goldner of Hughes & Goldner PLLC in Charleston.

U.S. District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia Case number 2:17-cv-01963

Organic Entrepreneur in Ripon Focuses on Fresh

Organic Entrepreneur in Ripon Focuses on Fresh

Nate Beck , USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin 8:53 a.m. CT Aug. 22, 2016

Brian Ernst, owner of Ernessi Organics in Ripon, grows microgreens and veggies in his basement urban farm.(Photo: Nate Beck/USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin)Buy Photo

RIPON - In a basement below Bluemke’s appliance shop in downtown Ripon, thousands of vegetables sprout every week, bound for the aisles of one of northeast Wisconsin’s biggest grocers.

Since it was founded two years ago, Ernessi Organics has grown to supply its greens to 16 grocery stores, including 13 Festival Foods locations across Wisconsin. Basil, amaranth and other veggies grown here can be found nestled in entrees at The Roxy, Primo Italian Restaurant and other eateries in the Fox Valley.

Ernessi’s fast success turns on consumer appetite for fresh and wholesome ingredients prepared locally, and retail’s efforts to catch up.

Ripon approved a $60,000 loan to the company last summer that helped pay for custom-made lights and other infrastructure. With a facility that produces 3,000 packages of fresh greens weekly, Ernessi can hardly keep pace with demand so the company recently launched an expansion that will double how much it can produce this fall.

So what does it take to start a blossoming company like this?

It’s about charging forward, head down, at the hurdles before you, said company founder Brian Ernst. “As an entrepreneur, you see a vacuum in the market and you go for it,” he said.

A geologist educated at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, Ernst found work after college at a large company, but soon tired of the work. He began tinkering with hydroponics, the process of growing plants without soil, in his basement. Ernst and his friend Tim Alessi began testing how light affects the growth of herbs and vegetables, settling on a combination that tricks plants into thinking that spring has just sprung, causing them to sprout faster.

In 2014, Ernst’s employer laid him off. Rather than shopping his resume around to other companies, Ernst, at the urging of his wife, decided to turn this hydroponic hobby into a company.

At Ripon's Ernessi Organics, a variety of microgreens and vegetables grow in a basement urban farm. (Photo: Nate Beck/USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin)

But to do that would require cash.

So he and his wife sold everything they could: TVs, furniture, Ernst’s 401(K), all of it. With $10,000, the company was born, three months after he and his wife had their second child, while raising a 3-year-old.

So, no. Starting a business isn’t about safety.

The draw about this breed of farming is that it can be done anywhere. Inside the Ernessi operation, floor-to-ceiling steel racks support rows of budding plants on trays. One four-foot-by-eight-foot palate of veggies yields 576 plants in just 35 days, using much less water than a typical farm would. And here in Wisconsin, with its brutal winters, there’s no end to Ernessi’s growing season.

This latest expansion will allow the company to double its production and deliver its plants faster, with a new refrigerated truck. The company’s business is built on supplying plants to grocery stores or restaurants less than 24 hours after they are cut, for the same price as producers elsewhere.

To meet this, Ernst said expanding the company to different parts of the Midwest will likely require him to franchise the company. These veggies are no longer local, he said, if they travel more than two hours to their destination. So in the next five years, Ernst hopes to start a location in Duluth, Minnesota, for example, that would supply produce to grocery stores and others in that market.

For now though, Ernst is focused on the company’s expansion, and growing new products, lettuce, gourmet mushrooms and more. He plans to use leftovers from the beer-making process at nearby Knuth Brewing Co., a Ripon-based brewery, for the soil to grow mushrooms. Lately, he’s been wheeling a blue plastic drum two blocks up Watson Street to the brewery to collect the stuff.

“If you have the drive, starting a business is not a hard decision,” Ernst said. “Any entrepreneur will tell you, there’s never a good time to start a business.”

The harder you work, the smaller these hurdles seem.

Reach Nate Beck at 920-858-9657 or nbeck@gannett.com; on Twitter: @NateBeck9.

At Ripon's Ernessi Organics, a variety of microgreens and vegetables grow in a basement urban farm. (Photo: Nate Beck/USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin)

Buying The Farm

Buying The Farm

Staff Writer, The Ringer

The future of agriculture is happening in cities. After years of experimentation, Silicon Valley may finally be making urban farming viable. But will residents be able to afford the crop?

The town of Kearny, New Jersey, is a small industrial desert, populated by warehouses, factories, and twisting freeways filled with hulking cargo trucks. Its natureless landscape and the decrepit remains of 19th-century textile factories make it so uninviting that it was occasionally used as a filming location for HBO’s The Sopranos. In other words, it’s the kind of place where you’d expect to see a mobster toss a dead body into a dumpster — it is not where you’d expect to see a nice man in plaid harvesting baby kale. But the day I visited a warehouse on a concrete lot in Kearny, I watched Irving Fain, the CEO of a new urban farm named Bowery, do just that.

“Are you a kale fan?” Fain asked me excitedly.

I met the 37-year-old Fain, who’s tall with messy brown hair and an enthusiastic grin, in a tidy waiting room at the back of the building. He was wearing a flannel shirt, jeans, and comfortable tennis shoes. But that was not what he wore when we headed into the adjacent room. Instead, we zipped our bodies into papery hazmat suits, tucked our hair into nets, and placed protective booties over our shoes.

The moment we walked into the spotless, brightly lit room, occupied with rows of tall remote-controlled towers that contained trays of leafy greens under LED lights, Fain morphed into a giddy, considerably healthier Willy Wonka. A single attendant had ordered the farm’s autonomous robotic forklifts to lower the portable crops onto conveyor belts and send them toward us. We walked up to their landing table, and with a pair of mini scissors, Fain began snipping leaf after leaf for me to taste. First came the arugula (which he called “crisp and peppery”), then the purple bok choy (“It’s, like, amazingly good”), then the spicy mustard greens that the executive chef at the Manhattan restaurant Craft had specifically requested (the owner, Top Chef star Tom Colicchio, is an investor in Bowery). Each sample was a pristine vision of plant life, with zero sign of the unsightly deformities that come from bugs and dirt — the risks of being grown outdoors.

And then there was the kale.

“One of the compliments our kale gets a lot is: ‘Man, I never liked kale, but I had to like kale, and I actually really like your kale,’” Fain said.

A begrudging kale consumer myself, I took a skeptical bite and was pleasantly surprised. I tasted no hints of the bitter chalkiness associated with the superfood. It was light and sweet and unusually fresh compared with the produce at my local Key Food. All this, without ever coming into contact with the outside world.

But the kale wasn’t delicious simply because it was grown without pesticides, or because Fain, who previously ran a customer loyalty software startup, has a green thumb. The kale was delicious because, in addition to maintaining a mostly autonomous farming system, Bowery uses proprietary software that collects data points about what influences a plant’s health, growth rate, yield, and factors that affect its flavor. According to Fain, it analyzes the information in real time, and automatically pushes out changes to the treatments of crops as it sees fit. I liked the kale in part because its growing conditions were dictated to a microscopic degree by machine-learning software that Fain lovingly calls “FarmOS.”

(Bowery)

Bowery is the latest of a handful of urban farm startups attempting to reinvent how people, specifically city dwellers, get their food. In February, the startup announced that it had raised a healthy $7.5 million from a handful of venture funds, joining the likes of companies like BrightFarms, AeroFarms, and Square Roots that have caught the eye of tech investment firms over the past few years. The premise of these companies, as they tell it, is simple: America’s current farming system is wrought with inefficiencies. Climate change is threatening our ability to efficiently grow crops. And, on top of that, food must be hauled great distances to reach highly-populated city centers. In the process, taste, quality, and shelf life are sacrificed. By growing plants in warehouses, shipping containers, and city-adjacent greenhouses, these next-gen farmers claim they are able to eliminate the threat of unpredictable weather, waste less water, reduce transportation costs, and — most enticingly — stop basil from wilting within 30 seconds of landing in the refrigerator. And even if agricultural experts warn that their farming models might not be enough to ameliorate the world’s food-shortage issues, that has not stopped these companies from adding a utopian flair to their marketing efforts. The same way that Soylent has floated its product as a way to end world hunger, these farming startups are angling to be seen as the solution to our collapsing agricultural system.

Aside from the chance to, as one farmer I spoke to put it, “disrupt the industrial food system,” supporting urban farming is especially appealing to Silicon Valley investors. As mega tech entrepreneurs have colonized Northern California over the past few decades, they have internalized elements of its collective environmental conscience and crunchy farm-to-table culture. (After all, it’s hard to snag a reservation at Chez Panisse without first learning who the hell Alice Waters is.) When climate change skeptics questioned Tim Cook’s 2014 pledge that Apple would invest in renewable energy, the typically mild-mannered CEO reportedly became “visibly angry” and told them to sell their shares. Cafeterias at corporations like Google have long offered organic, hormone-free meals made with ingredients sourced from local farms. In 2011, Mark Zuckerberg even announced a new “personal challenge” to eat meat only from animals he’d killed himself. Tech industry titans are so enamored with healthy, tasty, ethical food, that they once invested $120 million to develop a $700 machine that makes an eight-ounce glass of organic juice. Silicon Valley’s decision to invest in urban farming startups is just about as inevitable as Steve Wozniakchecking in at the Outback Steakhouse in Cupertino on a weeknight. It comes with the territory.

(Bowery)

These new-age agricultural businesses have found it helpful to update the language of an ancient industry to emphasize their innovative approach, and better cater to their ideal audience. Along with naming his facility’s operating system “FarmOS,” Fain has also coined the term “post-organic” to describe Bowery’s completely chemical-free produce and elevate its cachet in the competitive world of gourmet salad. The difference, as he explains it, is that the United States Department of Agriculture technically allows organic farmers to use certain pesticides and organic produce is sometimes exposed to chemicals spread from nearby farms, while his product is completely “pure and clean.” Last year, Elon Musk’s brother Kimbal lifted the startup incubator model popularized by Y Combinator and applied it to farming, launching the Brooklyn-based company Square Roots. (In his obligatory Medium post announcing the endeavor, he cited evidence that microwave sales were declining and declared that “Food is the new internet.”)

Square Roots’ premise is vaguely reminiscent of the contest described in the opening credits of America’s Next Top Model: 10 individual farmers are given their own app-controlled, 320-square-foot steel shipping container to grow plants in for a year. In what the company’s cofounder and CEO Tobias Peggs has dubbed a “farmer-to-desk” model, individuals can receive weekly deliveries to their workplace in the size of a “nanobite” (one bag), “megabite” (three bags), or a “terabite” (seven bags) from individual farmers in the program. In the end the farmers are set free to start their own enterprises. Even AeroFarms, a New Jersey farm startup that waters its plants with patented aeroponic misting apparatus and is the most established U.S. company of its kind, describes its progress in terms of traditional software release iterations (i.e. “AeroFarms 2.0”).

Not only have these startups modernized agricultural terminology, their marketing teams have also cozied up to the altruistic image of America’s modern-day agriculture movement. The history of urban farming in the United States has always been inextricably linked to the availability of food, and a community’s ability to grow that food itself. The earliest modern American urban farms were plotted in 1893, amid an economic recession. To aid the swaths of industrial workers who had recently lost their jobs, the mayor of Detroit, Hazen Pingree, launched an initiative that provided unemployed residents with vacant lots, materials, and instructions that they could use to establish their own potato farms. “Pingree’s Potato Patches,” as they were known, were so helpful in feeding needy residents that both Boston and San Francisco modeled programs after them until the economy improved. Similar programs were recycled in the 1930s, during the Great Depression.

By the early 20th century, programs similar to Pingree’s began popping up at schools in urban areas, stoked by urban reformers who worried that kids would be ruined by growing up in industrial environments. Schools in cities like Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia taught their students how to plant everything from sugar beets to rye as a way to impart individual responsibility, civic virtue, and — as one New York urban farm advocate from the time put it — “the love of nature by opening to their minds the little we know of her mysteries, more wonderful than any fairy tale.”

(Square Roots)

It wasn’t until the U.S.’s involvement in World War I began in 1917 that the federal government began pushing Americans to farm in the name of patriotism. In order to meet the export demands of food-starved Europe, the U.S. established the National War Garden Commission, a national organization that asked citizens to become “soldiers of the soil” by growing their own food. Posters encouraging agricultural action depicted gallant men and women working in fields, sometimes alongside anthropomorphic American-flag-toting potatoes. The campaign worked: The same year the government announced the program, it counted approximately 3.5 million war gardens.

Larger-scale agriculture had helped food supply become more reliable by 1939, but that didn’t keep the federal government from repurposing the movement at the beginning of World War II. The government’s updated campaign saw these “victory gardens” as a source of health and morale, even if the increasing growth of suburbs meant that people were planting them in the privacy of their backyards. Once again, patriotism took hold, and an estimated 18–20 million families had planted victory gardens by 1944, according to the Smithsonian’s digital archive of American gardening history.

In the 1960s and 1970s, activists began jump-starting their own urban-greening movements to ameliorate food deserts, benefit poor communities whose city neighborhoods were littered with vacant land, and educate locals on the benefits of healthful, seasonal eating. In 1969, a handful of UC Berkeley students and locals aimed to claim an empty lot owned by the university and transform it into what’s now known as the People’s Park. (“The University had no right to create ugliness as a way of life,” read an article in the alt newspaper the Berkeley Barb.) Organizers managed to mobilize thousands of people to convert the land into a green oasis, which conservative politicians and UC officials then attempted to bulldoze. Protesters stepped in to save the park and were promptly doused with tear gas. Governor Ronald Reagan called upon the National Guard to squash the conflict, but it only led to more chaos — including the death of a bystander, the permanent blinding of a protester, and injuries to more than 100 people. A fence school officials had put around the park before the riots began was promptly torn down. Eventually the university was forced to accept that its formerly empty lot would remain a park.

In 1970s New York — where a financial crisis had caused an uptick of abandoned buildings and lots in the Lower East Side, Hell’s Kitchen, and East Harlem — a nonprofit environmental group called the Green Guerillasbegan throwing “seed bombs” full of water, fertilizer, and seeds over fences and onto empty lots in an attempt to beautify them. One of the group’s founders, Liz Christy, eventually expanded its efforts by launching a campaign to remove trash and haul in soil to empty neighborhood plots. The legacy of environmental activists’ efforts has expanded in recent years, and neighborhoods feel encouraged to organize and contribute to local beautification projects, and build everything from chicken coops to beehivesin urban areas. It’s no wonder that the sight of flourishing green squares amid concrete buildings has since been symbolic of charitable, earthy activism.

The latest urban farming startups are not charities, though. They’re businesses. But they have not hesitated to co-opt some of the same talking points about local collaboration and healthy families heralded by their grassroots counterparts. The words “HEALTHY PEOPLE, HEALTHY COMMUNITY, HEALTHY PLANET” appear at the top of the BrightFarms website in all caps. Beneath them is the company’s mission statement: “For the health of the planet, by improving the environmental impact of the food supply chain. For the health of our society, by encouraging the consumption of whole and fresh foods.” AeroFarms goes one step further, declaring “We want to be a force for good in the world.” Square Roots’ explanation of why it exists is fittingly dramatic for a Musk brother’s operation: “Our cities are at the mercy of an industrial food system that ships in high-calorie, low-nutrient, processed food from thousands of miles away. It leaves us disconnected from the comfort, the nourishment, and the taste of food — not to mention the people who grow it. But people are turning against this system. People want real food — food you can trust to nourish your body, the community, the farmer, and the planet.”

Despite their admirable intentions, this new market is also exploiting a gray area in how people think about city-based farming. According to Raychel Santo, a program coordinator at Johns Hopkins’s Center for a Livable Future, the positive environmental, health, and community effects of independently run farms are now more frequently being lumped into the pitch decks of urban for-profit ventures.

“I do think people conflate the benefits of urban farms often: We can be less wasteful and improve food access and increase the number of jobs and things like that,” Santo said. “When people try to group all of the benefits together, you lose some of the granularity of the actual limitations of each type of urban garden.”

Even if the ultimate goal of these startups is to simply provide fresher, more nutrient-rich greens to urban areas, the messaging of many high-tech farming companies implies that their method of growing is a real solution to our future farming needs. “As the population grows, more food will need to be produced in the next four decades than has been in the past 10,000 years,” reads Bowery’s mission statement. “Yet resources like water are increasingly limited. There hasn’t been a practical path to provide fresh food at the volume and quality that people are looking for — until now.” When I spoke to Fain, he built on that statement, describing his business as the next logical stage for modernizing the world’s farms. “A lot of what the organic movement was about was how do we create a farming practice that allows better or slower regeneration and better protection of the land around us while also growing a higher quality food product,” he said. “And that was a great step. When the organic standards were written, a lot of the technology that we use today didn’t even exist. What we’re able to do at Bowery is the next evolution, the next step, from what organic was able to do from where industrial agriculture was before.”

Marc Oshima, cofounder of AeroFarms, also emphasized the company’s global ambitions by citing potential future projects in arid climates like Saudi Arabia. “It’s not just plants,” he said when I visited. “At the end of the day it’s about nourishing communities. It’s how we can build these responsible farms in major cities all over the world.” Musk made a similarly grand statement the day he announced Square Roots: “Our goal is to enable a whole new generation of real food entrepreneurs, ready to build thriving, responsible businesses,” he wrote. “The opportunities in front of them will be endless.”

Inreality, there are bigger food problems in the world than whether Manhattan grocery stores carry fresh arugula. The major challenges that our global agricultural system faces cannot be solved by urban farms alone.

According to Santo, whose research includes using climate change modeling to predict agricultural demand and supply, it’s projected that the global population will reach 9.6 billion people by 2050. As the effects of climate change set in and weather patterns become more volatile, farmers’ growing and harvesting seasons may be shortened or lengthened, depending on the circumstances, and they’ll be less certain of the amount of food they can produce year to year. Like many other countries, America’s food system is currently set up so that farms dedicated to specific foods — whether it be avocados, raspberries, or beef — are typically concentrated in a single location. So in a scenario in which different parts of the world are battling their own blizzards, droughts, or floods, the U.S. population would most likely experience frequent and significant shortages of specific goods. These shortages are already happening in different pockets around the world. At the beginning of March, a vegetable grower in southern Arizona that sells bags of baby spinach and “spring mix” announced that it ended its harvest earlier than usual because of an unusually damp season. This could mean a shortage of greens in early April. Similarly, snowfall in Spanish farming areas — a major source of England’s produce — has caused a temporarily low supply of zucchini, tomatoes, lettuce, peppers, and celery that began in the winter of 2016 and stretched into this year.

“The whole global food system that we rely on is heavily dependent on imports from other places and [a] very centralized system which creates a lot of potential problems,” Santo said. “A lot of research has gone into how the really complicated interconnected system that we’re facing is not very resilient if something were to happen to it.”

So, to what degree can these startups actually help? Even if vertically grown warehouse operations like Bowery, Square Roots, and AeroFarms help supplement a salad shortage here and there, their considerable output thus far still couldn’t come close to feeding, say, the entire city of New York, let alone the United States. (Especially since the average American craves a considerable amount of meat and dairy.) Unlike your average community or rooftop garden, typical vertical farms are located indoors, so they do nothing to help what environmental scientists call the “urban heat island effect,” a phenomenon that shows cities tend to be warmer than their surrounding landscape because of human activities and concrete structures. So far, Santo says the most significant effect commercial vertical farms might have on global food system issues is influencing the culture of food consumption and encouraging communities to learn more about where their food comes from.

(BrightFarms)

When it comes to disrupting that increasingly fragile industrial farming system, Santo argues that we may be better off relying on regional farms strategically placed outside highly populated areas to avoid blips in our system. Peri-urban (urban adjacent) greenhouse operations like BrightFarms are able to produce higher crop yields, and therefore have much more potential to make a dent in the system, while also avoiding the significant environmental and monetary costs that indoor farmers are forced to incur from powering stacks of bright LEDs.

“Greenhouses have a much greater potential,” Santo said. “There’s very little evidence of the substantial benefits [of vertical farming], in terms of environmental impacts, partially because of energy input, but also because you can use those buildings in other ways. You can be productive on rural and peri-urban land in much greater volumes.”

The Brooklyn-based company Gotham Greens is a successful test case for shrinking the greenhouse farm format to fit smaller metropolitan spaces, but still harvest enough produce to turn a profit. As some early indoor vertical farming startups have shuttered Gotham Greens CEO Viraj Puri has slowly expanded his business. The eight-year-old company employs about 150 people among four greenhouses, the newest of which recently opened in Chicago. Though Gotham Greens’s leaf mixes cost more than your run-of-the-mill lettuce bunch, they’re tastier, and generally stay fresh in the fridge longer than their grocery-store competition. Puri is heartened to see a new collection of vertical farmers experimenting with LED growing, though he’s not yet convinced that their methods make for a viable business.

“Our goal at Gotham Greens is to produce the most consistent, reliable supply of premium-quality produce in the most cost-effective manner, and today greenhouse technology provides that,” he said. “But I’m glad they’re doing the research. I don’t necessarily have an appetite to do a lot of research and development and not be profitable. That’s why you have technology companies.”

Still, visionaries of vertical farming remain optimistic that whatever challenges the industry faces will be sorted out as technology advances, and the government recognizes their utility. When Dickson D. Despommier, an emeritus professor of public and environmental health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, wrote a book about the possibilities of vertical farming in 2010, he wasn’t aware of any vertical farms that actually existed. He has since become one of the movement’s most prominent advocates. Though the vertical farming industry is in its infancy, he cites the rapid development of more energy-efficient LED lights and a growing variety of business structures as evidence that we will inevitably rely on indoor growing.

“Eventually the virtues of this will become so apparent that people will say: ‘What the hell are we doing outdoors when we can do this indoors?’” he said. “Just like they’re saying: ‘Why the hell should we burn coal when it’s much more efficient to get all your energy from solar and wind power?’”

Despommier points to Japan as a success story when it comes to the rapid adoption of vertical farms. After a massive earthquake and subsequent tsunami shook the country in 2011 and its Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant contaminated about 5 percent of the country’s farmland, the Japanese government rushed to secure alternate food solutions. It was what Dickson described as “the perfect storm” to encourage full integration of urban farming. Now, he says there are hundreds of vertical farms across the region, sometimes even integrated into workplace cafeterias. In many cases they’ve solicited the expertise of technology companies like Panasonic and Philips to establish more efficient farming methods.

“There’s not going to be instant success here any more than there was in the beginning of, say, Nokia,” Despommier said. “You can go down the line and see how advances in technology and efficiency of using that technology results in replacing the original invention with something that’s much better. That’s what the human species is very good at doing.”

For all the discussion of growing healthy communities, often the only way to balance the expenses of indoor urban farms is to cater to people who already have the money to buy fancy lettuce. In other words, their customers are gourmet restaurants, health-conscious tech companies, and Whole Foods clientele. All this despite the fact that most urban warehouse farms set up shop in low-income communities, where empty buildings are more plentiful and cheaper to rent. A box of AeroFarms greens costs $3.99, while Bowery’s greens go for $3.49 — loads more than someone on a budget might be willing to pay, when they can just grab a much cheaper loose head of lettuce. As a May 2016 report from the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future noted, “urban agriculture projects are not panaceas of social inclusion or equity.” According to Santo, disparity in access to more nutritious produce is a frequent pattern of for-profit city farms.

“Private companies like these put buildings in communities of lower income or communities of color,” she said. “Oftentimes they produce these really expensive greens for restaurants, but then go serve wealthy people for a different community in the city.” In short, the Whole Foods crowd simply has yet another option for fresh greens, and the communities housing the operations providing them can still afford only the same old wilted lettuce.

AeroFarms has come the closest to overcoming the many challenges of the modern vertical farm. The operation’s 70,000-square-foot facility in Newark, New Jersey, can grow 2 million pounds of food each year. It’s currently renovating a former steel supply company building half a mile away from its current headquarters, creating what will be its third major farm and a symbolic gesture of rehabilitation for the city. The startup has raised more than $70 million in venture capital from the likes of Prudential and Goldman Sachs.

“They’ve looked at our history, they’ve looked at our operating costs, and they’ve seen what the demand is,” cofounder Marc Oshima told me when I visited the farm. “They foresee why they want to be a part of this.”

The true question of Silicon Valley investors is almost always: Can a business scale up? Is it a Foursquare (doomed to mild popularity) or an Uber (able to expand at a near-terrifying pace)? The question is particularly tricky for something as intricately designed and finicky as a farm, which can’t simply be revamped by overhauling a portion of code or redesigning its user experience. But of all the vertical farming startups on the market at the moment, AeroFarms is closest to proving that its model is solid enough to be plopped in any urban center on the planet and still deliver the same amount of product on the same timetable. (In its case that product is limited to six different salad box mixes of leafy greens.)

The company was founded in 2004, thanks to the curious mind of Ed Harwood, an inventor and former associate professor at Cornell’s agriculture school, and AeroFarms’ current chief science officer. Harwood has toiled over refining each element of the company’s tightly coordinated growing process, from making LED lighting more energy efficient, to developing the best possible reusable fabric into which a variety of seeds can be sown to germinate and grow (his final iteration is patented). All of these elements are incorporated into each of the seven planting beds that fit into the Newark farm’s 20-foot-high, custom-designed towers.

The inventor’s secret sauce is a proprietary nozzle used to mist a plant’s roots with with nutrient-rich water, a method called aeroponics that cofounder Oshima says uses 95 percent less water than traditional farming, which is even less than hydroponic farming uses — and less than the average aeroponic farm uses. (He also made sure to mention it was “perfect” that I had chosen to visit the company’s HQ on World Water Day.) In addition to saving water, he claims the misting speeds up the growth rate of the plants themselves.

“The roots are able to get oxygen, which leads to a faster growing process, more biomass in a shorter period of time,” Oshima told me in a cold, messy meeting room that had a hole in the wall, a visual indicator of where this tech company’s priorities lie. “When we think about the business of farming, how do we have the right economics, how do we compete with that field farmer, in terms of scale, cost, and productivity? We think that aeroponics is part of that equation.”

AeroFarms’ plant beds aren’t mostly autonomous like Bowery’s. In fact, those tasked with examining plant life as it grows must stand upon adjustable accordion-like platforms to properly examine their subjects. But the company has collected a trove of data over the years from testing over 250 varieties of plants, and is developing predictive analytics and machine-learning softwares that are not unlike the kind Fain has advertised. Developers even made an in-house app to monitor the rapid progress of the crops. And when it comes to the taste of their greens, AeroFarms has earned the endorsement of chefs like Michel Nischan, a three-time James Beard Award–winning chef who also founded Wholesome Wave, a nonprofit that aims to improve access to fresh produce in low-income communities. Though Nischan is partial to produce grown the old-fashioned way, he was pleasantly surprised by the taste of AeroFarms produce.

(AeroFarms)

“Purely from a flavor and texture perspective, the stuff that comes out of the dirt is still superior to everything I’ve tasted, other than AeroFarms,” he said. “In my mind they were the ones that finally cracked the code. The spinach leaves are hearty, really sturdy, they had a really great texture to them, a really deep color, and when I ate them I got the flavor intensity that you get from nutrient density.”

As for community outreach, AeroFarms has made an earnest effort to integrate with its neighborhood however it can. In 2010, when the company was in its infancy and headquartered in upstate New York, Harwood sold one of the farming towers to the inner city Philip’s Academy Charter School, and the company still holds educational sessions there. (Last year, Michelle Obama toured the setup as part of her #LetsMove campaign to promote healthy eating and exercise.) Every Wednesday, employees set up a farmstand on the empty street outside the warehouse, even if the stuff it sells might be out of the price range for AeroFarms’ neighbors. The company has only 120 employees, many of whom are engineers, software developers, and microbiologists. But Oshima has made an effort to hire locals whenever he can, and takes pride in the fact that he’s taught people a skill scarcely practiced in a withering industrial town where unemployment is high. The company works with a local employment group to ensure over 40 percent of its workers are from Newark. While he was showing me the latest farm, one of them approached Oshima to ask about a work program that would allow the employee to take classes relating to urban farming. Recently, AeroFarms set up an informational booth at the brand-new Newark Whole Foods to spread the word about its product. As Oshima tells it, a mother and her baby approached to sing the praises of the company. “Future customer?” the AeroFarms employee asked, pointing at her child. “Future worker,” the mother replied.

“We get excited about how we can be an inspiration to the community,” Oshima, an otherwise reserved man, gushed. “So that was exciting.”

Nischan agrees that providing jobs to low-income communities is central to helping them afford better food. Beyond that, he argues that for-profit food companies that want to make their product affordable must structure their business plans to accommodate the extra costs that come with subsidizing a product.

“What AeroFarms is doing in Newark … by really focusing on hiring people from the local communities is actually the best beachhead that you can establish,” he said. “But when it comes to getting into Whole Foods and doing farm stands, if you want to help an underserved community because you’re producing food, and you want some of that food to transform the health of underserved communities in the place that your business calls home, you generally have to take some kind of a haircut.”

AeroFarms’ modest effect on the surrounding area is still germinating. And it may still be far off from its goal of becoming a global presence in destinations as far-flung as Saudi Arabia. But given that the vertical farming industry is exploring uncharted territory, what little impact it’s had is promising.

“There’s no playbook, no traditional government land grant,” Oshima said. “Universities aren’t developing the next generation of farmers — we are.”

While all the farmers I spoke to were eager to bridge the gap between the customers who can afford their high-quality produce and those who can’t, Jonathan Bernard seemed especially contemplative about the issue. The 24-year-old former accountant from Long Island grows premium lettuce in one of Square Roots’ narrow shipping containers, an operation that costs about $3,000 a month to maintain. The large rectangular boxes are lined up in the parking lot of the Pfizer building in Bed-Stuy, now an office that houses movie props and a variety of local food startups. At one point during the tour of his farm, he opened the door and pointed to the Marcy Houses, a cluster of public housing buildings across the street.

“Jay Z grew up right here, like literally,” he said, pointing to a fence. “And this fence is pretty symbolic of what’s going on. There’s a true barrier to getting in there. They have food deserts that they can’t get over. I can go back to Long Island, get whatever I want. But inside these communities they’re not getting fresh stuff.”

Bernard admits that he’s not entirely sure how to bring affordable food into a low-income community like Bed-Stuy without going out of business. “That’s kind of what we’re here figuring out,” he said. His intended business, a farm that grows nutrient-rich plants for performance athletes, also relies on an elite customer class. He recently showed off his operation to a handful of NBA players, and is also mulling the possibility of selling some decorative nasturtium leaves on the side to chefs, who will pay up to $60 a pound for the rare and fragile plant. Ultimately he predicts that the only way he can offer affordable produce to the people who need it most is by doubling his output.

“It costs money to light this thing, it costs rent to put it on this land,” he said. “If all else is the same, how do you get it cheaper? You have to produce more.”

Bernard isn’t currently individually paired with a business for weekly salad bag deliveries, but companies that have signed up have been impressed by the Square Roots service. As soon as Brannon Skillern, the 33-year-old head of talent management at stock exchange startup IEX, gathered about nine people in her office to participate in the program, she was visited by Square Roots farmer Electra Jarvis. Jarvis dropped off her first delivery, explained the properties of her heirloom-seed bok choy and that there was no need to wash it, and opened an email thread to encourage feedback. Soon Skillern started seeing her coworkers snacking on the greens straight from the bag. Though some people from the company have opted not to join because they’ve said it’s cheaper to buy salad at the grocery store, Skillern says that she values building a relationship with a farmer who’s within a mile radius of her home.

(Square Roots)

“It’s neat to have that back and forth with your farmer,” she said. “I follow Electra on Instagram and I can kind of see like ‘Oh, cool. She’s harvesting this this week.’ It just feels like the personal-connection aspect is not anything that you can get anywhere else.”

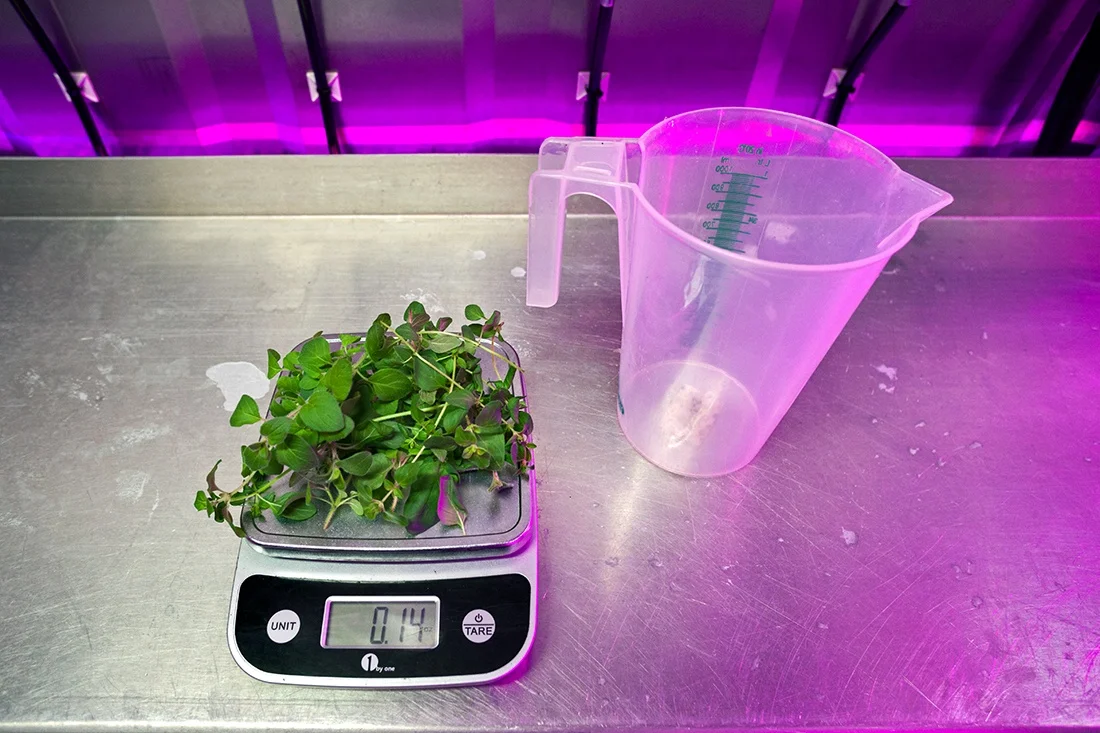

Bernard values that personal connection with customers as well. And the day I visited, he was testing a strategy to up his yield rate, in the hopes that he could nail down a structure that would allow him to give back to his surrounding community. He’d been tinkering with the temperature, light cycles, pH, and nutrient levels of his shipping container’s humming apparatus — powered by programs like Freight Farms and Bright Agrotech and monitorable via a smartphone app — to speed up the growth rate of his heirloom red leaf lettuce. Space in his narrow container is limited, so plants are stuffed into multiple rows of white plastic towers, which are rigged with plastic tubes for water delivery, and hung on a bar from the ceiling. Above them sit strands of red and blue LED lights (colored that way to beam only a portion of the light spectrum onto plants and conserve resources). Mixed together they wash the room in a purple glow.

Bernard unclipped a tower and placed it on a hook to remove a single bunch of healthy-looking lettuce, which he then placed on a metal scale. He recently began weighing each lettuce plant to measure whether he could produce 100 pounds of food a week. His goal was to hit somewhere between 4 and 5 ounces per plant. He grabbed this one ahead of schedule, to test whether his amped-up settings could help it get there earlier. Before delicately placing it on the scale, he pointed to a few tiny leaves sticking out at the root, which he proudly explained to be the remnants of the plant’s very first growth, and something that would’ve been quickly decimated in a traditional agricultural setting. The plant clocked in at 4.69 ounces, and a smile spread on Bernard’s face.

“That makes me really happy,” he said. “It’s the size that I wanted three weeks earlier than I expected.” It was a small triumph for him, maybe a microscopic one in the larger industry of vertical farming. But it was progress. We celebrated with a tasting. The lettuce was flavorful, crisp, and juicy. He sent me home with a bunch, along with a baggie of his pricy nasturtium leaves. It lasted in my dinky fridge for well over a week.

'Vertical Farming' Brings Futuristic Growing Methods To Middle Tennessee

'Vertical Farming' Brings Futuristic Growing Methods To Middle Tennessee

Mona Hitch reaches for celery at the top of one of her vertical farm towers.

CREDIT CAROLINE LELAND

Mona Hitch tends to one of her 8-foot vertical farming towers. She says she and her husband eat salads grown "vertically" in their greenhouse every day.

CAROLINE LELAND

Originally published on April 11, 2017 9:56 am

There’s a bit of science fiction sprouting up in greenhouses around Middle Tennessee. It’s called vertical farming, and it’s basically like growing vegetables in a greenhouse on steroids.

Vertical farming incorporates methods that seem futuristic — aquaponics, aeroponics, and hydroponics — that can provide locally grown vegetables year-round. And even if it won’t immediately solve food shortages around the world, vertical farming is predicted to reach almost $6 billion in revenues within the next five years.

Springfield resident Mona Hitch tends a greenhouse filled with rows of eight-foot PVC towers. Edible plants peek through dozens of holes drilled into the sides. Hitch’s greenhouse contains ten of these towers, though it has capacity for 50. Right now Hitch is growing multiple lettuce varieties, different kinds of kale, just about any herb you could think of, even edible flowers.

“I fell in love with it for several reasons,” Hitch says. “I know where my food is; I know what’s on it. I’m my own pest control, and I can just step outside in flip flops and pearls or high heels and we have salad every day.”

Lisa Wysocky displays a model of the LED lighting system she plans to use in a vertical farm on her nonprofit's property.

CREDIT CAROLINE LELAND

Any non-root crop that’s not too tall can grow in a vertical farming system.

Hitch’s system cycles water with dissolved nutrients from 20-gallon tanks at the base of each tower, through the plant roots inside the vertical PVC pipes. There’s no soil involved. This method is called aeroponics, because the plants are suspended in the air.

All About Efficiency

Supporters of this system argue that it will become commonplace and even trendy, like cruelty-free factory farming for plants. Vertical farming uses 90 percent less land and up to 95 percent less water for a higher yield, with no pesticides.

Facilities can be built on rooftops and in empty warehouses, and certain plants can grow year-round regardless of weather, in less than half the time.

Lisa Wysocky, the executive director of an Ashland City nonprofit called Colby’s Army, plans to build a solar-powered vertical farm for charity on her property by May. Folks will be asked to pay what they can for the vegetables.