Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

From Moscow: A ‘City Farm’ Home Appliance

From Moscow: A ‘City Farm’ Home Appliance

The body is completely leak-tight, made of sound eight-layered composite aluminum. You can select out of 9 coloring options.

Regulated «smart» tinting coating of a farm’s glass door enables to turn down the glaring light RainbowSpectrum ™. Tinting coating is controlled with the use of the INTELLIGENT EXPERT application.

Module body is made of Softtouch plastic due to which it is highly wear-resistance and possesses elegant appearance.

Innovative module structure with in-built drip watering system enables to

control the level of the nutrients and minerals supply to the plants as well as enables to easily change the glasses for growing.

Rainbow Spectrum ensures efficient process of plant photosynthesis at the expense of using solely the blue and red spectrum colors. Innovative light-emitting diode unit is automatically adjusted to the croppings grown in the city farm creating the most favorable conditions for their growth and fruiting.

Automatic climate control system ensures favorable air temperature and humidity for the croppings development inside a city farm. Measurements by all parameters are displayed in the INTELLIGENTEXPERT application.

A Farm Grows In The City

Startups are leading the way to a future in which more food is grown closer to where people live

At AeroFarms’ indoor vertical farm in Newark, N.J., greens grow on shelves 36 feet high Bryan Anselm for The Wall Street Journal

A Farm Grows In The City

Startups are leading the way to a future in which more food is grown closer to where people live

By: Betsy McKay | Photographs by: Bryan Anselm for The Wall Street Journal

May 14, 2017 10:05 p.m. ET

Billions of people around the world live far from where their food is grown.

It’s a big disconnect in modern life. And it may be about to change.

The world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, 33% more people than are on the planet today, according to projections from the United Nations. About two-thirds of them are expected to live in cities, continuing a migration that has been under way around the world for years.

That’s a lot of mouths to feed, particularly in urban areas. Getting food to people who live far from farms—sometimes hundreds or thousands of miles away—is costly and strains natural resources. And heavy rains, droughts and other extreme weather events can threaten supplies

Now more startups and city authorities are finding ways to grow food closer to home. High-tech “vertical farms” are sprouting inside warehouses and shipping containers, where lettuce and other greens grow without soil, stacked in horizontal or vertical rows and fed by water and LED lights, which can be customized to control the size, texture or other characteristic of a plant.

Companies are also engineering new ways to grow vegetables in smaller spaces, such as walls, rooftops, balconies, abandoned lots—and kitchens. They’re out to take advantage of a city’s resources, composting food waste and capturing rainwater as it runs off buildings or parking lots.

“We’re currently seeing the biggest movement of humans in the history of the planet, with rural people moving into cities across the world,” says Brendan Condon, co-founder and director of Biofilta Ltd., an Australian environmental-engineering company marketing a “closed-loop” gardening system that aims to use compost and rainwater runoff. “We’ve got rooftops, car parks, walls, balconies. If we can turn these city spaces into farms, then we’re reducing food miles down to food meters.”

Moving beyond experiments

Plants at AeroFarms receive light of a specific spectrum

Urban farming isn’t easy. It can require significant investment, and there are bureaucratic hurdles to overcome. Many companies have yet to turn a profit, experts say. A few companies have already failed, and urban-farming experts say many more will be weeded out in the coming years.

But commercial vertical farms are well beyond experimental. Companies such as AeroFarms, owned by Dream Holdings Inc., and Urban Produce LLC have designed and operate commercial vertical farms that aim to deliver supplies of greens on a mass scale more cheaply and reliably to cities, by growing food locally indoors year round.

At its headquarters in Irvine, Calif., Urban Produce grows baby kale, wheatgrass and other organic greens in neat rows on shelves stacked 25 high that rotate constantly, as if on a conveyor belt, around the floor of a windowless warehouse. Computer programs determine how much water and LED light the plants receive. Sixteen acres of food grow on a floor measuring an eighth of an acre.

Its “high-density vertical growing system,” which Urban Produce patented, can lower fuel and shipping costs for produce, uses 80% less fertilizer than conventional growing methods, and generates its own filtered water for its produce from humidity in the air, says Edwin Horton Jr., the company’s president and chief executive officer.

“Our ultimate goal is to be completely off the grid,” Mr. Horton says.

The company sells the greens to grocers, juice makers and food-service companies, and is in talks to license the growing system to groups in cities around the world, he says. “We want to build these in cities, and we want to employ local people,” he says.

An AeroFarms employee inspects a tray of greens.

AeroFarms has built a 70,000-square-foot vertical farm in a former steel plant in Newark, N.J., where it is growing leafy greens like arugula and kale aeroponically—a technique in which plant roots are suspended in the air and nourished by a nutrient mist and oxygen—in trays stacked 36 feet high.

The company, which supplies stores from Delaware to Connecticut, has more than $50 million in investment from Prudential, Goldman Sachs and other investors, and aims to install its systems in other cities globally, says David Rosenberg, its chief executive officer. “We envision a farm in cities all over the world,” he says.

AeroFarms says it is offering project management and other services to urban organizations as a partner in the 100 Resilient Cities network of cities that are working on preparing themselves better for 21st century challenges such as food and water shortages.

The bottom line

Still, these farms can’t supply a city’s entire food demand. So far, vertical farms grow mostly leafy greens, because the crops can be turned over quickly, generating cash flow easily in a business that requires extensive capital investment, says Henry Gordon-Smith, managing director of Blue Planet Consulting Services LLC, a Brooklyn, N.Y., company that specializes in the design, implementation and operation of urban agricultural projects globally.

AeroFarms packaged greens await shipment.

The greens can also be marketed as locally grown to consumers who are seeking fresh produce.

Other types of vegetables require more space. Growing fruits like avocados under LED light might not make sense economically, says Mr. Gordon-Smith.

“Light costs money, so growing an avocado under LED lights to only get the fruit to sell is a challenge,” he says.

And the farms aren’t likely to grow wheat, rice or other commodities that provide much of a daily diet, because there is less of a need for them to be fresh, Mr. Gordon-Smith says. They can be stored and shipped efficiently, he says.

The farms are also costly to start and run. AeroFarms has yet to turn a profit, though Mr. Rosenberg says he expects the company to become profitable in a few months, as its new farm helps it reach a new scale of production. Urban Produce became profitable earlier this year partly by focusing on specialty crops such as microgreens—the first shoots of greens that come up from the seeds—that enerally grow indoors in a very condensed space, says Mr. Horton, who started the company in 2014.

One of the first commercial vertical-farming companies in the U.S., FarmedHere LLC, closed a 90,000 square-foot farm in a Chicago suburb and merged with another company late last year. “We’ve learned a lot of lessons,” says co-founder Paul Hardej.

Among them: Operating in cities is expensive. The company should have built its first farm in a suburb rather than a Chicago neighborhood, Mr. Hardej says. Real estate would have been cheaper.

“We could have been 10 or 20 miles away and still be a local producer,” Mr. Hardej says.

The company also might have been able to work with a smaller local government to get permits and rework zoning and other regulations, because indoor farming was a new type of land use, Mr. Hardej says. While FarmedHere produced some crops profitably, it spent a lot on overhead for lawyers and accountants “to deal with the regulations,” he says.

Mr. Hardej is now co-founder and chief executive officer of Civic Farms LLC, a company that develops a “2.0” version of the vertical farm, he says—more efficient operations that take into account the lessons learned. Civic Farms is collaborating with the University of Arizona on a research and development center at Biosphere 2, the Earth science research facility in Oracle, Ariz., where it runs a vertical farm and develops new technologies.

Blossoming tech

New technology will improve the economic viability of vertical farms, says Mr. Gordon-Smith. New cameras, sensors and smartphone apps help monitor plant growth. One company is even developing augmented-reality glasses that can show workers which plants to pick, Mr. Gordon-Smith says.

“That is making the payback look a lot better,” he says. “The future is bright for vertical farming, but if you’re building a vertical farm today, be ready for a challenge.”

Some cities are trying to propagate more urban farms and ease the regulatory burden of setting them up. Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed created the post of urban agriculture director in December 2015, with a goal of putting local healthy food within a half-mile of 75% of the city’s residents by 2020. The job includes attracting urban-farming projects to Atlanta and helping projects obtain funding and permits, says Mario Cambardella, who holds the director title.

“I want to be ahead of the curve; I don’t want to be behind,” he says.

Many groups are taking more low-tech or smaller-scale approaches. A program called BetterLife Growers Inc. in Atlanta plans to break ground this fall on a series of greenhouses in an underserved area of the city, where it will grow lettuce and herbs in 2,900 “tower gardens,” thick trunks that stand in large tubs. The plants will be propagated in rock wool, a growing medium consisting of cotton-candy-like fibers made of a melted combination of rock and sand, and then placed into pods in the columns, where they will be regularly watered with a nutrient solution pumped through the tower, says Ellen Macht, president of BetterLife Growers.

BetterLife Growers will use ‘tower gardens’ like these to grow lettuce and herbs in Atlanta. Photo: Scissortail Farms

The produce will be sold to local educational and medical institutions. “What we wanted to do was create jobs and come up with a product that institutions could use,” she says.

The $12.5 million project is funded in part by a loan from the city of Atlanta, with Mr. Cambardella helping by educating grant managers on the growing system and its importance.

Change at home

Another company aims to bring vertical farming to the kitchen. Agrilution GmbH, based in Munich, Germany, plans to start selling a “plantCube” later this year that looks like a mini-refrigerator and grows greens using LED lights and an automatic watering system that can be controlled from a smartphone. “The idea is to really make it a commodity kitchen device,” says Max Loessl, Agrilution’s co-founder and chief executive officer, of the appliance, which will cost 2,000 euros—about $2,200—initially.

The goal is to sell enough to bring the price down, so that in five years the appliance is affordable enough for most people in the developed world, Mr. Loessl says.

Biofilta’s Foodwall system of connected containers requires minimal watering. Photo: Ben Mulligan

Biofilta, the company Mr. Condon co-founded, is marketing the Foodwall, a modular system of connected containers, an approach that he calls “deliberately low tech” because it doesn’t require electricity or computers to operate. The tubs are filled with a soil-based mix and a “wicking garden-bed technology” that stores and sucks water up from the bottom of the tub to nourish the plants without the need for pumps. The plants need to be watered just once a week in summer, or every three to four weeks in the winter, says Chief Executive Marc Noyce. The tubs can be connected vertically or horizontally on rooftops, balconies or backyards. “We’ve made this gardening for dummies,” Mr. Noyce says.

The Foodwall can use composted food waste and harvested rainwater, helping to turn cities into “closed-loop food-production powerhouses,” Mr. Condon says.

He and Mr. Noyce were motivated to design the Foodwall by a projection from local experts that only 18% of the food consumed in their home city of Melbourne, Australia, will be grown locally by 2050, compared with 41% today, Mr. Noyce says.

“We were shocked,” says Mr. Noyce. “We’re going to be beholden to other states and other countries dictating our pricing for our own food.”

“Then we started to look at this trend around the world and found it was exactly the same,” he says.

Traditional, rural farming is far from being replaced by all of these new technologies, experts say. The need for food is simply too great. But urban projects can provide a steady supply of fresh produce, helping to improve diets and make a city’s food supply more secure, they say.

“While rural farmers will remain essential to feeding cities, cleverly designed urban farming can produce most of the vegetable requirements of a city,” Mr. Condon says.

Ms. McKay is a senior writer in The Wall Street Journal’s Atlanta bureau. She can be reached at betsy.mckay@wsj.com.

Appeared in the May. 15, 2017, print edition.

Camden Will House The World's Largest Indoor Farm, Thanks To State Tax Breaks

Camden Will House The World's Largest Indoor Farm, Thanks To State Tax Breaks

Updated on May 16, 2017 at 9:26 AM Posted on May 16, 2017 at 7:45 AM

For NJ.com

CAMDEN -- The world's largest indoor farm is expected to open its doors in Camden next year, thanks to a tax break from the state.

Aerofarms LLC, a Newark-headquartered company that builds sustainable, efficient farms around the globe, plans to open its 10th facility, a 78,000-square-foot vertical farm, at 1535 Broadway in Camden.

The addition comes after the state Economic Development Authority announced Thursday that Aerofarms will receive $11.14 million in tax incentives over 10 years to build the farm in Camden. The facility is expected to create 56 new jobs in the area, according to documents from the agency.

That makes Aerofarms just one of several companies, including Subaru and Holtec, that have received incentives to relocate to the city as authorities look for ways to revitalize the area.

"We probably would not have made the move to Camden -- at least not now -- without the [Grow New Jersey] tax grant," David Rosenberg, the company's founder and CEO, told Philly.com.

Aerofarm's vertical spaces and aeroponics growing technologies allow them to grow produce efficiently, using up to 95 percent less water than traditional agriculture methods while still seeing yields that are 130 times higher per square foot each year, according to the company's site. The hydroponic method uses a mist to provide plants with nutrients and water they need to grow in the smaller urban spaces.

$30M 'vertical farm' to bring jobs to Newark, fresh greens to N.J., developers say

But starting and maintaining the spaces often proves pricey. Aerofarms has yet to make a profit, and relies on investors, including Goldman Sachs and Prudential, to continue its operations. Rosenberg told The Wall Street Journal that he believes the Newark farm, which boasts 70,000 square feet of growing space, will help the company turn that corner in coming months.

The farms, which supply produce to stores from Delaware to Connecticut, will become increasingly important as urban areas become more dense and the population continues to grow, urban farming advocates say. Rosenberg told The Wall Street Journal he hopes to see the farms in cities around the world as the company expands.

But for now, New Jersey officials are glad to see the future of farming take off across the state.

"By 2050 there will be 9 billion people who need to eat every day," Lieutenant Governor Kim Guadagno said during the 2015 groundbreaking of the Newark farm. "And the solution is right here on the property you're standing on."

Amanda Hoover can be reached at ahoover@njadvancemedia.com. Follow her on Twitter @amahoover. Find NJ.com on Facebook.

The Citadel's Container Farm Is First Of Its Kind For Military College

The Citadel's Container Farm Is First Of Its Kind For Military College

Friday, April 28th 2017, 10:59 pm CDTFriday, April 28th 2017, 10:59 pm CDTBy Alexis Simmons, Reporter/MMJ

CHARLESTON, SC (WCSC) -

The Citadel's first harvest was ready from its container farm on Friday.

It's the college's Sustainability Project, part of The Zucker Family School of Education’s STEM Center of Excellence.

Tiger Corner Farms Manufacturing a company based in Summerville provided the container farm.

It uses the process of Aeroponics, growing plants in an air or mist environment without the use of soil and you control the environment.

The Citadel Cadets harvested five different types of lettuce.

It was Citadel grad and U.S. Marine 2nd Lt. Benjamin Cohen's idea to bring it to campus. He's also the Sustainability Project Founder.

"It is amazing, absolutely amazing to see what the cadets have done," Cohen said. "This entire project was envisioned for them, the idea being that we would build a farm on campus that is planned built managed developed expanded by cadets and that was really the selling point."

The 40 ft. container produced enough lettuce to cover about 2 acres of land. It totals up to several thousand heads, each that can be continually harvested

Another perk, it's organic and you don't have to worry about pesticides because it's enclosed.

Stage one of the process involves putting the seeds in trays. After they are watered they are moved to vertical panels where the lettuce will grow for four to six weeks. The plants are watered through state of the art technology and artificial lighting helps them grow.

The cadets can also track the system on a computer to make sure everything is running correctly.

Junior Cadet, Alex Richardson is the President of the Sustainability Project.

"You don't have to be a farmer to do something like this, I have no farming experience, I'm just an engineering student," Richardson said.

Matthew Miller is a sophomore cadet who's involved with the project as well.

"It's the community idea, this is something that as long as you have the right essentials you could put this in Antarctica, in Egypt, in Charleston, South Carolina," Miller said "That's really the goal you want to provide for people that can't do that themselves."

Several restaurants near campus have agreed to use the lettuce.

The lettuce will also be used in the college's dining hall to feed the campus on a regular basis.

The cadets built the inside components of the container farm and planted the lettuce.

The harvest party is intended to help raise the funds for a second container for next year for the campus.

Copyright 2017 WCSC. All rights reserved.

Riding The Agriculture & Food Wave – Indoor Vertical Farming

Riding The Agriculture & Food Wave – Indoor Vertical Farming

Posted on May 11, 2017 by Leo Zhang

Following our recent blog post on alternative proteins, let’s take another look at the agriculture & food sector and touch on a related topic of sustainable food production – indoor vertical farming. Although vertical farming has yet to attract similar level of investments compared to alternative proteins, this space is certainly worth keeping track of as we expect more mega-cities to form over the next decade, and subsequently, the demand for a more sustainable food production system.

Below is a quick overview of what we are seeing in terms of innovators and investors, and for a close look at this space, please do get in touch with us at research@cleantech.com.

Hydroponics, Aquapoincs, and Aeroponics

There are three main types of vertical farming systems – hydroponics, aquapoincs, and aeropoincs. The hydroponic system grows plants without soil using mineral solutions in water, and it is the predominant system currently used in vertical farms. The aquaponic system combines a plant hydroponic system with indoor fish ponds. Finally, the aeroponic system grows plants without soil, and uses an air or mist solution to deliver nutrients. Examples of innovators include:

Who’s Interested?

We have seen the rise in the overall agriculture & food investment amount starting in 2014. Among this wave of investments, agricultural software, plant genomics, and even drones & robotics make up a large percentage of the total investment. Nevertheless, we have tracked a number of venture deals in the vertical farming subsector, particularly by early-stage investors.

For example, Bowery, a New York-based indoor produce grower, raised $7.5M in seed funding in April 2017. Participating early-stage investors include First Round Capital, SV Angel, Lerer Hippeau Ventures, in addition to a number of private angel investors.

Another notable example to highlight is Plenty, a California-based developer of vertical farms that incorporates AI, data analytics and IoT sensors, which raised an astonishing $26M in Series A funding earlier this year. Two noteworthy investors to highlight here – Bezos Expeditions (Amazon’s Jeff Bezos) and Innovation Endeavors (Google’s Eric Schmidt) – signify the growing importance of sustainable food production.

What’s Next?

As most vertical farm companies are still operating at a very small scale, it is expected that most of the funding has come from angel and seed investors. However, will the next wave of investments in this space come from corporate investors? Will vertical farming be able to scale up to massive food production systems?

We will certainly be keeping our eyes on this space. Let us know your thoughts via research@cleantech.com

New Skyscraper Farm Will Feed A Village

NEW SKYSCRAPER FARM WILL FEED A VILLAGE

Posted by Elise Phillips Margulis | May 12, 2017

Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, and Yemen are suffering from a famine that affects 20 million people. According to eVolo magazine, over 40 percent of people living in sub-Saharan Africa live in extreme poverty. In the last three decades, absolute poverty has been reduced from 40 percent to 20 percent worldwide. Unfortunately, the green revolution including clean energy, fertilizers, irrigation, and high-yield seeds that doubled grain production between 1960 and 2000 on other continents has failed multiple times in Africa due to limited markets, bad infrastructure, civil wars, and an ineffective government.

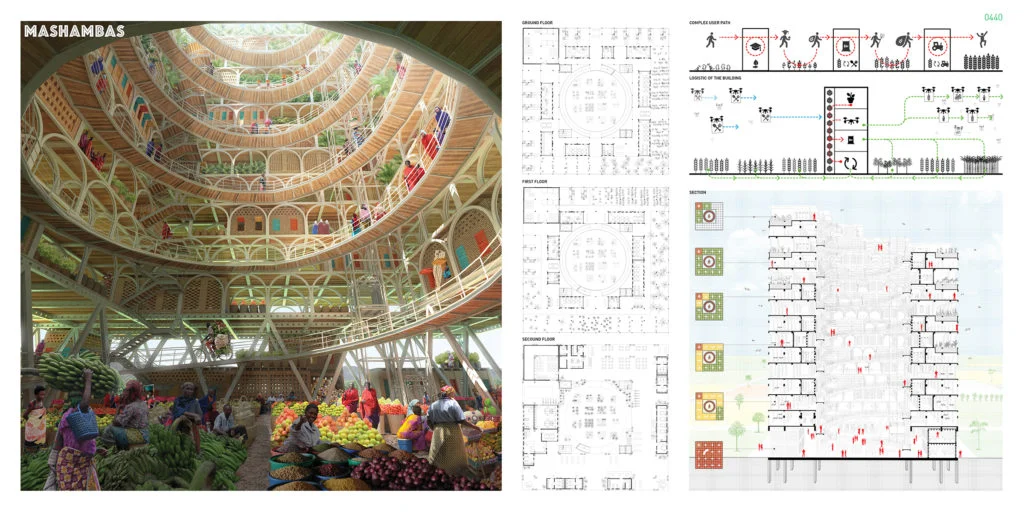

The eVolo magazine presents and discusses architecture embodying technological advances, sustainable concepts, and innovative designs. Each year, eVolo hosts a competition and awards the structures that they admire most. This year’s top prizewinners were two Polish architects, Pawel Lipinski and Mateusz Frankowski. They designed the Mashambas Skyscraper which houses a farm, an education center, and a community center.

The ingenious structure facilitates the training of subsistence farmers in modern farming techniques. Providing the farmers with inexpensive fertilizers and state-of-the-art tools enables them to increase their crop yields dramatically. The skyscraper also creates a local trading area, which helps to maximize profits. The objectives are self-sufficient farming and overcoming poverty and famine.

The top of the proposed skyscraper is comprised of layered fields. There’s a drone docking center in the middle so agricultural products can be flown to isolated locations. The first floor consists of a kindergarten, a doctor’s office, and an information center.

The designers of the Mashambas Skyscraper predict that the combination of training, fertilizer, and seeds will enable small farmers to harvest as many crops per acre as large farms do. This will end famine, as the village will have food for itself and enough to sell to nearby villages. Another amazing feature of the structure is that it can be moved. The base remains in place and the other floors can be relocated to educate other farmers.

According to The Vertical Farm , the world population will increase by three billion people by 2050. Right now, 80 percent of the land that can be used for growing crops has been built on. Vertical farming will use less land to grow more food. We’re going to need a lot of vertical farms!

Vertical Harvest Blazes Trail In Its First Year

Vertical Harvest Blazes Trail In Its First Year

Employees are working out operational kinks at 13,500-square-foot greenhouse downtown.

BRADLY J. BONER / NEWS&GUIDE

Kai Hoffman hangs tomato plants at the Vertical Harvest greenhouse. After one year operators said the greenhouse is about halfway to their goal of growing 100,000 pounds of produce annually. Though it has not turned a profit yet, they said farms usually take three years to do so.

POSTED: WEDNESDAY, MAY 10, 2017 4:30 AM

By John Spina | 0 comments

When Vertical Harvest opened its doors to the public on May 26, 2016, it received national attention for its innovative design and business model. Communities around the world immediately started calling to figure out ways to replicate it.

There was just one problem: Vertical Harvest was still trying to figure it out for itself. Being one of the first of its kind required a constant trial-and-error process to get all the parts working together.

“There’s not a week that goes by where another community doesn’t contact us and say they want to replicate this,” said Nona Yehia, co-founder of Vertical Harvest. “We had a vision of how this would all work out, but that’s definitely still an evolution. I don’t think you can underestimate the fact that there is no playbook for this.”

The 13,500-square-foot greenhouse is state of the art. Each room acts as its own microecosystem, regulated to maintain the ideal heat, moisture, UV light and carbon dioxide levels for 35 crops so that they grow in the fastest, most nutritious and environmentally sustainable way possible, all year long, at 6,200 feet above sea level.

Figuring out how to get all the cutting-edge technology to work together, however, was a daunting task.

Lettuce short-circuited lights

During the first year Vertical Harvest had to replace tens of thousands of specially made Dutch LED lights because the recycled water splashing out of the rotating carousels carrying lettuce plants short-circuited them. It took four months to order new ones.

“Once we took care of the lights then the plants started getting heavier, and the ones that were next to the irrigation started creating their own little wetlands,” Yehia said. “So we had really big plants on one end and really little plants on the other end. We adjusted the irrigation system again, but that increased the splashing. Once we got that under control the plants got so heavy it started straining the carousel.”

Learning to farm in Wyoming’s severe climate was another hurdle.

“We had to go back to the source on everything,” she said. “What are the proper seeds, what are the proper labs to use, how can we have replacement material on hand? Just all of these different levels of learning. Then, once you think you figured something out, there are 1,000 different consequences to your success.”

Three years to make a profit

Having operated for a year Vertical Harvest is still working out the kinks, but the problems are becoming fewer and farther between.

Since the LED lights were replaced in January the greenhouse has quadrupled its lettuce production. The goal is to grow 100,000 pounds of fresh produce a year. Right now Vertical Harvest produces somewhere between 50,000 and 60,000 pounds a year.

“It’s definitely getting better,” said Tim Schutz, Vertical Harvest’s director of production. “It takes time because every crop that you run though that takes two months to grow, you learn one or two things how to make it better.”

The produce has provided needed income, but it hasn’t pushed Vertical Harvest into the black. Sam Bartels, Vertical Harvest’s head of business operations, isn’t too worried, saying traditional farms usually take about three years to make a profit.

“Honestly, if we didn’t have these issues it’d be almost insulting to the farmers who have been fighting the hard fight for years,” Bartels said. “If you put that 50,000 or 60,000 pounds to scale back to general agriculture it’s incredibly good, especially for a 13,500-square-foot greenhouse.”

While the farming aspect of Vertical Harvest has been challenging, its employment model, which focuses on hiring developmentally disabled people, has been a clear success.

“What I’m most surprised by is not the greenhouse’s effect on the employees,” Yehia said, “but the employees’ impact on the greenhouse.”

From the beginning Vertical Harvest’s co-founders Penny McBride and Yehia were intent on integrating disabled people into the greenhouses workforce. One year in, 17 physically or mentally disabled people are employed at least part time.

“In terms of stress this project has probably pushed us all to our limits at different points in time,” Bartels said, “and it probably will continue to, but the motivation and morale our employees provide to the team is really important and something we really want to share with other businesses.

“When it’s one in the morning and there’s something I want to do, I’m like, ‘Oh, get it together, Johnny needs this job,’” he said. “It really does change your work behavior. That’s why we all come into work.”

Critical to the operation

With roughly half of the staff having some form of disability, Caroline Croft, Vertical Harvest’s employment facilitator, said the young men and women have not only developed better personal and communication skills but also become critical to the greenhouse’s operations. Some have been promoted to managerial positions.

“One of our employees told me, ‘I love working at Vertical Harvest because I can be myself,’” Croft said. “We’ve got a young man working here who was changing sheets at one of the local hotels. It was a pretty solitary job, and if he had stayed in that isolated environment he would have gone inwards and become isolated.

“Now, working here, he literally can do every job in the greenhouse, from tour guide to retail workers to microgreens seeder to doing deliveries,” she said. “I’ve had old teachers, old labor providers, even his parents tell me it’s amazing how much he’s come out of his shell.”

Thanks to community support Vertical Harvest was given the chance to push the boundaries of agriculture. Adding social, educational and environmental aspects pushed staffers to their limits, but with a year of experience they believe they have accomplished something truly groundbreaking.

“It’s insanity,” Bartels said. “But it’s just the right amount of insanity. This is a world-first farm. I think the opportunities it presents for Wyoming as a state are great. This is like the tech boom for agriculture. Nine years ago this was just a concept.”

Cheevers beet sprouts at Vertical Harvest

Green butter-head lettuce at Vertical Harvest.

Tomatos at Vertical Harvest.

Sustainable Food Production Looking Up

Sustainable Food Production Looking Up

Editor: zhangrui 丨Chinadialy

05-08-2017 07:13 BJT

A laboratory worker in full biohazard gear is patrolling rows of rainbow colored LED-lit shelves. The shelves stand about 2 meters and have six levels, each containing trays of lettuce saplings bathing underneath the light, and the room is illuminated in a psychedelic pink.

A laboratory worker in biohazard gear checks the growth of lettuce in the vertical farm in Anxi, Fujian province. ZHAN ZHUO / FOR CHINA DAILY

This is no scene from a science fiction movie, but a common sight for scientists at a plant factory in Anxi, Fujian province, which covers 1 hectare and is the largest vertical farming complex in the world. The second-largest is a 0.64 hectare farm in Newark, New Jersey.

Vertical farming is the practice of growing vegetables and fruits in vertically stacked layers of hydroponic solutions in a controlled, indoor environment. It does not require soil, sun or pesticides, and uses far less water and fertilizer than conventional farms.

However, the farm's high-energy cost has greatly limited its scale and profitability. In recent years, Chinese scientists at the Anxi plant factory have mitigated the issue by inventing energy efficient LEDs and recyclable hydroponic solutions, as well as new energy-conserving methods to maximize a plant's growth potential.

San'an Sino-Science, the company behind the project, says these new methods have cut the factory's overall energy consumption by 25 percent compared with its first facility.

"We hope to cut more energy so vertical farming can become a viable way to feed our population without polluting and straining our already scarce water and soil resources," the factory's executive manager, Zhan Zhuo, said.

"The technology would also allow astronauts, aircraft carrier personnel, and frontier guards on islands or in deserts to grow fresh produce in impossible conditions to fill their daily vitamin and fiber needs.”

China has 160 million hectares of farmland dedicated to growing vegetables. To grow them, farmers use more than 311,000 metric tons of pesticide and 59 million tons of fertilizer a year, said Li Shaohua, director of San'an Sino-Science's Photobiology Industry Institute.

"The excessive yet inefficient use of fertilizers and pesticides has done great harm to our environment," he said. "It's high time we find a sustainable and green way to protect our food security."

San'an Sino-Science was founded in 2015 by San'an Group and the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Botany. The second-generation plant in Anxi can produce 1.5 tons of vegetables, such as lettuce and cabbage, a day.

At full capacity, when the energy cost is neglected, it can produce 1,000 tons of leafy greens a year in theory, according to Li. "The high productivity is mainly because we try to emulate the most ideal natural conditions for plant growth, and use technologies to cater to their every needs."

Before entering the plant factory, visitors must put on a dual-layered jumpsuit, goggles, a face mask, rubber gloves and boots, and be disinfected from head to toe. Sneezing in the factory is strictly prohibited.

"The standard here is stricter than hospital operating rooms," said Zheng Yanhai, a botany researcher at the institute who works at the plant factory. "Because all the plants are growing in nutrient-filled hydroponic solutions, we do not want germs to get into the liquid and make plants sick."

Thanks to the clean environment, plants can grow without antiseptics or pesticides, "you can even eat it fresh out of the bag", Zheng added.

In addition to sanitation, scientists also take temperature, humidity, air circulation, light, carbon dioxide, nutrients and other elements into account to create the "perfect environment" for growth.

A tightly controlled environment not only maximizes growth potential, but also allows scientists to create food that suits specific needs, Zheng said.

For example, scientists can lower the amount of potassium from lettuce for patients with kidney problems or increase zinc in cabbage for children by altering the nutrient solution and growing conditions.

"This is the fundamental difference between a plant factory and conventional farm," he said. "We simply have extensive control over how and when our plants can grow, and let nature run its course in the most ideal conditions."

The requirements for plant growth fall into two broad categories: photosynthesis and soil nutrients.

The sun accounts for 90 percent of all botanic bioenergy through photosynthesis — a process in which plants combine carbon dioxide and water and turn them into carbohydrates and oxygen. Sunlight is a bundle of different wavelengths of light across a wide spectrum from ultraviolet to infrared.

Plants are "picky eaters that favor blue and red lights", Li said. "If we can figure out what ratio and combination of lights are best suited for each plant's growth, then we can change or create LED lights that shine at that specific intensity and spectrum, saving lots of energy in the process," he added.

While blue and red lights are the "meat and potatoes" of a plant's growth, scientists notice other spectrums of light also play a subtle role in maximizing growth and quality.

For example, scientists discovered that adding some green light to the red-blue recipe could help some vegetables grow, while too much green light puts plants into hibernation, although this is helpful for the plant's nutrient build up.

"Mimicking sunlight using LED is very energy intensive," Li said. "At the end of the day, whoever has the most energy-efficient and productive light recipe wins."

While plant growth mostly relies on light, water and carbon dioxide, it still needs some trace elements from soil or fertilizers to be healthy. In the case of plant factories, hydroponic nutrient solutions infused with 17 essential elements ranging from nitrogen to calcium have replaced the tilted soil.

"The content of the nutrient solution is also tailored to suit the plant's specific needs," said Pei Kequan, a research director at the factory. Unlike the trace elements from fertilizers, which are locked in big compound molecules, "the nutrients in the solution are broken into small molecules, meaning the plant can absorb them easier and grow faster while keeping its nutrient value and taste".

It takes about 20 days for a sapling to reach maturity in the lab, but 40 to 60 days in a conventional farm. This means scientists can reap more than a dozen harvests of produce each year, compared with one to two harvests from a conventional farms, depending on the weather conditions, he said.

Moreover, scientists at the facility have built the infrastructure to monitor the elements in the solution. Once an element is depleted, scientist can add the missing nutrient and reuse the solution without needing to make a new batch, thus reducing the cost.

"We go to great length to study and cater to our plant's most fundamental needs, making sure they could grow under the best conditions," Pei said. "In a way, the plants are the kings, and we are all its servants."

It's high time we find a sustainable and green way to protect our food security."

Growing Student Success - One Seed At A Time

GROWING STUDENT SUCCESS

One Seed at a Time

Taylor Pruitt is an agricultural business and hospitality innovation double major. She’s a busy sophomore involved in her sorority, taking in study groups and coffee breaks and Arkansas football games. But between classes, instead of heading back to her room or chatting with friends, Pruitt heads over to a shipping container where she spends around 20 hours doing one thing – farming lettuce.

Since August 2016, Chartwells has been growing lettuce in a shipping-container-turned-sustainable-farm called the Leafy Green Machine. The farm comes from an environmentally conscious, sustainability-minded company based out of Boston, Massachusetts, called Freight Farms.

Protected from temperature changes and other environmental disturbances, the refurbished shipping freight is a fully functioning hydroponic farm that uses a vertical growing system. With approximately 260 hanging towers, over 3,000 heads of lettuce are growing in the Freight Farm at any given time.

Inside the container, LED light strips provide crops with shades of red and blue – the light spectrums required for photosynthesis. A hydroponic system delivers a nutrient rich water solution directly to roots, using only 10 gallons of water a day. Energy-efficient equipment automatically regulates temperature and humidity in the Freight Farm through a series of sensors and controls.

Overall, the Freight Farm project has the potential to shorten the food supply chain, cut emissions, decrease costs, and overall, significantly reduce the campus’ carbon footprint.

After sliding off her backpack and switching off the LED growing lights for the overhead fluorescents, Pruitt begins her work. She examines the health of the heads of lettuce and replants sprouting seedlings that have moved on from germination. She checks the nutrient levels on the in-house farm monitoring system. If it’s time to harvest a crop of lettuce, she throws her hair back and starts slinging vertical growers around with a speed that can only come with familiarity.

Pruitt, along with Merrisa Jennings, another student worker, and Ashley Meek, nutritionist and staff manager of the Freight Farm project, all work in the farm during the week. They handle weekly harvests, un-racking vertical growers, removing the lettuce head, bagging it, replanting the rack with a new seedling, and repeating.

The entire project is funded by Chartwells Dining Services. Why pour funds and resources into a project like this? Growing student success.

12,716 HEADS OF LETTUCE HARVESTED

15 # OF HOURS SPENT IN THE FREIGHT FARM EACH WEEK

2 NUMBER OF STUDENT WORKERS

While researching new ways to incorporate sustainability-minded projects into food service on campus, Andrew Lipson, resident district manager for Chartwells at UARK, became intrigued with the idea of locally growing food on campus and distributing it to the dining halls. Lipson realized the Freight Farm project would also allow for Chartwells to bring students into the farming process.

“Of course we want to be able to reduce waste and shorten the food supply chain on campus – we’re always looking for innovative ways of doing that, but we also want to do is work with students,” Lipson said. “We want to bring them in however we can. I mean, we’re here to serve them. They’re the reason why we come into work everyday.”

Lipson said after securing the funding and space for the Freight Farm, it was time to find a staff.

“And then we met Taylor,” Lipson said. “She was this dynamic, energetic freshman we met at a hospitality fair at 8 a.m. in the morning on a Saturday. That shows some real initiative, especially from a student at that stage of their college career. We instantly knew she would be a great fit for the project.”

Lipson, Pruitt and other Chartwells employees travelled to Boston to train with Freight Farm staff members on how to maintain the farm and be successful hydroponic farmers. The two-day training consisted of technical skills and community development.

Outside of the environmental benefits of the Freight Farm and the delicious, leafy greens it brings to campus dining halls, the hydroponic farm is fostering a deep growth of interest in students for community engagement, food security, and social responsibility.

For Freight Farms the company, the main goal is to spread an awareness of the need for sustainable solutions to food systems and breed a kind of connectedness and engagement with the community on where it’s food comes from.

“We’re not just selling a product, we’re building a community,” Caroline Katsiroubas, director of marketing for Freight Farms said. “If we’re trying to decentralize the food system and put the power back into the hands of the smaller farmers, we have to invest in an infrastructure that will follow them throughout their journey. We want people to join the movement and push it forward.”

Katsiroubas said the company has always been interested in working with institutions of higher learning.

“The coolest thing has been seeing the enthusiasm and almost urgency to get Freight Farms onto college campuses,” Katsiroubas said. “There is such value to having a Freight Farm on campus because its not just the fresh produce – its having students interact with sustainable farming and engaging with locally grown produce. It allows the food to be attached to a larger story of community engagement.”

“I’ve always had an interest in agriculture. I grew up going to my grandfather’s farm and my dad had one too. So I have a real appreciation for the actual cultivation of plants. I take classes where I learn about plants and the science behind it, but working on the Freight Farm is a common ground between my two majors. It brings together agriculture in the way that food is produce and hospitality in the way that food is given to the consumer.”

Taylor Pruitt -Freight Farm Student Worker

With the global community concerned about the pervasive global warming, food, and water security issues, teaching students about sustainable food options is vital to building tomorrow’s innovators.

For Pruitt, her job working at the Freight Farm is a creative way to combine both of her interests of agriculture and hospitality.

“I’ve always had an interest in agriculture. I grew up going to my grandfather’s farm and my dad had one too,” Pruitt said. “So I have a real appreciation for the actual cultivation of plants. I take classes where I learn about plants and the science behind it, but working on the Freight Farm is a common ground between my two majors. It brings together agriculture in the way that food is produce and hospitality in the way that food is given to the consumer.”

This past year, Pruitt took an educational trip to India and interacted with food insecurity in a way she never had before.

“Being in India, it helped me get that bigger picture of what is going on in our world and what needs to be worked on,” Pruitt said. “I feel like working in the Freight Farm is me contributing to society and contributing in a way that I can use my knowledge, my information, my resources to contribute and make this world a better place.”

“We can’t live in a world where we have people dying of starvation. People are dying because we can’t figure out a way to provide food soon enough,” Pruitt said. “Working in the Freight Farm, participating in that community and spreading that knowledge, I feel like is one small way for me to make a difference.”

Pruitt said working the in the hydroponic farm day-to-day is giving her a real world connection to what she’s learning in the classroom.

“Actually working in a hydroponic farm makes it so real. That’s why I’ve been so thankful that Chartwells decided to invest in students. Chartwells has invested so much into me, and they want to make sure that students here get involved in things they’re passionate about,” Pruitt said. “Whenever they first told me about the Freight Farm, I was excited to work on the project but I wasn’t super passionate these environmental process or food security. But it’s become such a reality in my life, and it’s made me realize we really need to work more on projects like this and further this project so we can provide for people and help people provide for themselves.”

Not only is Pruitt working to build a more informed and sustainable community at UARK, she is building her resume.

“Professors would love to send kids for professional development and out-of-classroom experiences if they could, but they don’t have the money to do that. Chartwells has been able to hire students, giving me work while I’m in school,” Pruitt said. “I have to work to get myself through school, so I would have been working a normal part-time job. That job would have gotten me through, but it wouldn’t have given me a once in a lifetime opportunity like the Freight Farm project has given me. Other students don’t get to do this everyday. I feel so lucky and blessed that I’m a part of something like this.”

“The degrees that we offer here, whether it be biological engineering, horticulture, agriculture, cultural sciences and environmental sciences – all of these degrees would work really well with working in the Freight Farm. I think it gives them an alternative idea of what they could use their degrees for instead of the conventional go work on a farm or go to food processing centers. Those jobs are important and needed, but this gives them an option they might not have thought about before. It gives them a completely new area of study to look towards.”

Merrisa Jennings - Freight Farm Student Worker

In order to take better care of the environment and find a way to feed the hungry, farmers and scientists must get creative. Environmental solutions like the Freight Farm project might be one answer to the complicated issue of food insecurity and environment consciousness farmers and scientists face. Moreover, as the world becomes more urbanized, vertical farming like Freight Farms can be used to help meet the increasing demand for fresh local produce.

Merissa Jennings said working in the Freight Farm brought life to what she’s learning in the classroom and gave it a practical, real-world application.

“I took a class called Sustainable Biosystem Design this past semester. It’s all about making sure whatever you’re doing, whether it be building a bridge or building a power plant, from start to finish it comes from sustainably sourced materials with efficient designs,” Jennings said. “So this is something that touches home because the Freight Farm lives in a cargo container – Freight Farms recycled the container, the nutrients they give us come from reused or recycled materials, and it runs on very little energy and water.”

Jennings, a biological engineering and biochemistry double major, is graduating in May 2018 and heading off into a career that will involve graduate school, but ultimately a career in sustainable community development.

“The Freight Farm project definitely ties into what I’m learning in school, and then what I’ve noticed with all my experiences both here and abroad,” Jennings said. “Food is a huge necessity; I think we all can agree on that. One of the biggest environmental issues that we have is the way we are currently producing our food; it’s really, really damaging to our environment and our water systems. It’s also economically detrimental to us because the more fertilizers we have to keep adding to soil, the more it’s being drained of nutrients. And then because of all the crops we’re putting into the soil that fertilizer is going to start running off, and it has been running off into our water systems, making it more and more expensive for us to clean that water for us to drink it. The cycle for human implications is huge. This project just shows me that this is another way we can lessen our effect on our food crisis.”

Jennings is excited about what her future career in biological engineering and biochemistry and the possibilities ahead.

“I’m really interested in sustainable community development – plant genetics, bacteria genetics, yeast genetics. I want to go into either biofuels or food production or maybe even both, because with plants, you can mess with their genetics and make them better for food and fuel,” Jennings said.

“Let’s say, for example, with crops you can use corn stalks, the part of the plant that’s not edible, and turn that into biofuels. I could use genetics with the plants to make them a better food source. I can change the microbes that will be eating that corn stalk to be converted into biofuels. I can even change the corn stalks genetics so it produces a certain protein or make them more resistant to pesticide if that’s something that’s going to be used on the crops. The possibilities are endless and the impact is so great when you’re dealing with plant genetics.”

Jennings said students with a variety of majors in STEM could benefit from working in the Freight Farm.

“The degrees that we offer here, whether it be biological engineering, horticulture, agriculture, cultural sciences and environmental sciences – all of these degrees would work really well with working in the Freight Farm,” Jennings said. “I think it gives them an alternative idea of what they could use their degrees for instead of the conventional go work on a farm or go to food processing centers. Those jobs are important and needed, but this gives them an option they might not have thought about before. It gives them a completely new area of study to look towards.”

Jennings said she realizes the high-level science behind some of these processes turns students away from learning about agriculture and sustainability, but being able to bring students into the Freight Farm and tell students about it around campus really breaks down the barrier of entry.

“That’s the ‘wow’ factor, because bringing student in here who have no idea what the Freight Farm is, even if the students aren’t already passionate about sustainable food processes, showing them what we’re doing kind of breeds this curiosity and draws them in,” Jennings said. “We’re told to question everything during college and explore ideas we haven’t been exposed to yet, so I think its pretty cool that we’re able to introduce these ideas not just to already passionate, sustainability minded people but to the average student who wouldn’t have any idea about sustainable farming through the shipping container.”

“Not only did we want to give our campus fresh, locally grown produce, we also wanted to make it an educational experience. I feel like you’ve really established a great program for students now and we’re looking forward to continuing that.”

Ashley Meek - Campus Dietician

Ashley Meek, the campus dietician for Chartwells at the University of Arkansas and staff member in charge of the Freight Farm project, said the future of the Freight Farm looks like producing even more lettuce, maybe some different herbs as well, and potentially hiring more students and taking on interns.

“Not only did we want to give our campus fresh, locally grown produce, we also wanted to make it an educational experience,” Meek said. “I feel like you’ve really established a great program for students now and we’re looking forward to continuing that.”

The Freight Farm has consistently produced a harvest every week since August 2016. Meek said the consistency is not just because of the innovative engineering of the Freight Farm, but because of the dedication and hard work put in by the student workers.

“Taylor and Merissa’s two unique backgrounds come together so well, and so much of both worlds end up playing a role in our Freight Farm,” Meek said. “They’re the primary operators. They get to run it on a day-to-day basis. They both handle the nitty-gritty work that goes into hydroponic farming.”

Meek said she is proud of what the team has been able to accomplish and what they’ve been able to contribute to the campus food system.

“People want their produce from where they’re living and where they’re working. Being on a large campus where we serve over 10,000 meals, it can be a real challenge trying to source that much local produce,” Meek said. “The Freight Farm is one way we can start attacking that problem.”

The Freight Farm will continue to produce harvests over the summer, seeing new student workers come and put in work on the hydroponic farm, planting new opportunities to grow more student success.

Is Farming In a Box Viable, or Just a Fad?

Is Farming In a Box Viable, or Just a Fad?

May 8, 2017 | Trish Popovitch

Bed in a bag, soup in a jar, cake in a cup and now ‘farm in a box’? As many urban-ag-ers jump on the shipping container farm bandwagon that’s made inroads across the pro-grow community, some are wondering if the farm in a shipping container idea is really as cost effective and sustainable as it may at first appear. Hydroponics has proven a sustainable and reliable method for growing food in the city. Where concrete fields abound, so do vertical towers. Yet some would argue that a successful hydroponics system needs more than an upcycled shipping container to sustain success.

In states with short growing seasons and tumultuous weather, the idea of an indoor, self-contained growing unit employed to produce consistent and plentiful yields and steady revenue streams seems like the ideal solution for spreading sustainability, growing local and decreasing the impact of long established food deserts.Essentially, the typical farm in a box is an upcycled shipping container with approximately 320 square-feet of grow space outfitted with a custom hydroponic kit utilizing vertical growing systems. The farmer, or entrepreneur, who invests anywhere from $70,000 – $125,000 in a single farm unit has the potential to produce hundreds of pounds of leafy greens that he/she can sell to restaurant and wholesale customers, or at the farmers’ market. Some farmers have had success while others have

Nate Storey, founder of Bright Agrotech, the world’s leading manufacturer of vertical grow towers, believes in hydroponics and the water saving science that lies behind his highly successful product. Storey is not a fan of putting his growing containers in, well… shipping containers.

“So my opinion is that shipping containers are great for shipping things around the world and a serious compromise for anything else. I believe that container farming is possible, but shipping containers are the wrong way to do it,” says Storey.

Storey has no issue with the idea of a self-contained farm but every business needs room to operate effectively and for this reason, Storey finds freight containers too small.

“I’ve never known anyone with the patience or bankroll to grow in a freight container for more than a few years,” he says. “And given the fact that they depreciate very, very quickly compared to most other farms, shipping containers are a pretty questionable investment.”

As Storey explains, flexibility is a must in the container farmer’s world. Without room to grow, experiment and even expand, the container farmer is limited. “There are folks like Modular Farms selling containers that are larger than shipping containers and fabricated specifically for plant production. I think that those types of farms have a future,” says Storey. “Those are the types of container farms that will ultimately own the container market because they were designed with intent.”

Even with a preference for the larger container on the market, Storey feels warehouse space is still the best option for many. “Most growers growing in warehouses are doing quite well on the other hand, and warehouses are typically more valuable after years of growing/occupancy than they were before. Folks are getting better yields because they have more room to operate and more systems flexibility,” says Storey.

In the world of sustainable agriculture, the desire, often the need, to be as sustainable as possible can cause issues. Repurposing can facilitate startups and demonstrate a commitment to bettering the planet through mindful growing practices. Yet sustainable businesses must be sustainable. If rapid expansion is necessary to facilitate the growth of a business, perhaps a warehouse makes more sense than a row of used shipping containers. If leasing warehouse space is not in the startup budget, perhaps a container farm would provide a temporary platform for a new brand. A chance for short growing season states, like that of Wyoming-based Bright Agrotech, to extend the growing season, farming in shipping containers needs careful planning to insure long-term success.

“Ultimately, I’m excited to see anyone farming locally, but we really need to be discerning about what is worth investing in and what is not,” concludes Storey.

Freight Farmer Q&A: Tassinong Farms

FREIGHT FARMER Q&A: TASSINONG FARMS

APRIL 18, 2017

8 QUESTIONS WITH KATE HAVERKAMPF OF TASSINONG FARMS

One of the best parts of being part of the Freight Farms team is talking to our freight farmers and hearing about their successes, their businesses, their customers, and their challenges. They are a wealth of information, so now we are sharing some of their stories with you!

Kate Haverkampf of Tassinong Farms is providing the community of Crested Butte, Colorado with fresh produce year-round. In terms of location, Kate is one of our most extreme farmers, growing at an elevation of 8,885 feet. Crested Butte has less than ideal growing conditions, so the food available there is often shipped from hundreds to even thousands of miles away. Kate was motivated to start farming because she wanted to supply her region with local, fresh produce. We recently spoke with Kate about her experience as a freight farmer and the ways in which it has impacted her community.

Freight Farms (FF): What, if any was your experience with farming before becoming a Freight Farmer?

Kate Haverkampf (KH): Before becoming a freight farmer, my closest connection to farming was the nine generations of farmers in my family. I spent holidays at my grandmother's, uncle's and godfathers' farms, played in the barns, wandered around the corn fields but never really did any actual farming. I was a real beginner!

FF: Who do you sell to and how do you sell to them?

KH: I sell to restaurants, bars, caterers and local residents within 20 miles of my farm. I like to stay "hyper-local." I have standing orders that are pre-arranged with restaurants and bars. My website offers residents the ability to order on a week to week basis. Caterers text, call or email me when they are looking to order.

FF: What kinds of crops do you grow?

KH: I grow different varieties of lettuce: Alkindus Butterhead, Muir Greenleaf, Coastal Star Romaine, Truchas Romaine, and Sylvestra Butterhead. I also grow Toscano Kale, Rainbow Swiss Chard, Sorrel and Edible Violets. Occasionally I experiment with new types of lettuce as well.

FF: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to people interested in becoming Freight Farmers?

KH: Three things: 1.) Give yourself at least one year to turn a profit and consider waiting if that timeframe seems too long. 2.) You are going to mess up and make mistakes, and that is okay. Give yourself six months to feel comfortable understanding the workings of the farm and Agrotek programming. 3.) Do not promise your customer specific yields when they first sign on based on what your farm should be able to grow. Commit to conservative yields while you're learning, and then once you become an expert you can increase what you can sell them. Issues will occur, and you don't want to be always calling them when you are newly operating and having to tell them you cannot deliver what you promised.

FF: What’s your favorite crop and why?

KH: Alkindus Butterhead - it is so yummy, crispy, colorful!

FF: How has urban agriculture improved or impacted the lives of people in your community?

KH: A great example is as follows: I have a friend with a four-year-old and a seven-year-old boy. Both boys and her husband don't like vegetables. Ever since they tried my mixed greens, the boys and the husband love salads and will only eat my mixed greens. That is a great example of why I am doing this. To get my local community to love greens again that are fresh, local and always the best quality.

FF: What are your plans for the future?

KH: We'll be adding two new farms to make a total of four by the beginning of summer 2017. We'll also be adding a retail storefront that will sell my product and other local produce. In the evening it will be a small wine bar and craft beer lounge where my product and other tasty appetizers will be served.

FF: What reaction do you typically get from people when you tell them what you do for a living?

KH: They have so many questions and are genuinely curious about how it all works. They especially like to learn that I transitioned to a new career and I think they feel inspired that they can do it, too, if they choose.

Make sure to follow Kate and Tassinong Farms on Facebook and Instagram for updates from the farm!

If you'd like to learn more about how Freight Farms is helping farmers grow food in regions across the United States, Canada, Europe, and the Caribbean reach out to us here.

Affinor Growers To Install Large Scale Vertical Strawberry Farm In Canada

Affinor Growers To Install Large Scale Vertical Strawberry Farm In Canada

Affinor Growers has received its largest equipment order to date from a license holder in Abbotsford B.C. These 10 level growing towers will be installed during the next 6 months and be used to grow and produce strawberries and other produce.

The license holder has ordered 32 vertical growing towers capable of holding 20,480 strawberry plants in 10,000 square feet. Under the terms of the order, a single vertical tower will be manufactured and installed immediately to verify various installation design specifications with the remainder 31 growing towers to be delivered and installed over the summer.

Jarrett Malnarick, President and CEO comments, "We are excited to see our license holder and partner in Abbotsford B.C. progress with construction of the facility, as it will be a showcase to demonstrate Affinor's vertical technology on a large scale, as well as revenue from equipment sales and potential long term royalties."

Strawberry University of the Fraser Valley test site update

The small 4 level, 8 arm tower, and the 4 level 16 arm tower are now producing strawberries. Affinor expects to start harvesting strawberries within the next several weeks. Affinor and UFV are testing various strains, crop inputs, lighting conditions and nutrients to maximize production, document protocol and prepare for commercial applications.

For more information

Affinor Growers

AeroFarms Partners With 100 Resilient Cities – Pioneered by The Rockefeller Foundation To combat Climate Change And Food Insecurity

AeroFarms Partners With 100 Resilient Cities – Pioneered by The Rockefeller Foundation To combat Climate Change And Food Insecurity

AeroFarms, the world leader in indoor vertical farming announces a strategic partnership with the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities to combat climate change and food insecurity.

100 Resilient Cities - Pioneered by The Rockefeller Foundation (100RC) helps cities around the world become more resilient to social, economic, and physical challenges that are a growing part of the 21st century. 100RC provides this assistance through: funding for a Chief Resilience Officer in each city who will lead the resilience efforts; resources for drafting a Resilience Strategy; access to private sector, public sector, academic, and NGO resilience tools; and membership in a global network of peer cities to share best practices and challenges.

Feeding a growing population while stemming the tide of climate change is a major challenge for cities all over the world and AeroFarms will offer its expertise in addressing these pressing issues to the 100RC members.

“We are thrilled to be able to offer our considerable expertise and experience to help make cities more food resilient and find effective and creative ways to address food security, and announcing this strategic partnership at the annual Seeds + Chips Global Innovation Summit in Milan, Italy where Milan is one of the 100 Resilient Cities is the perfect way to kick off this program as we look to build responsible farms all over the world” said AeroFarms CEO David Rosenberg.

AeroFarms joins a prestigious group of other “Platform Partners” that have committed to helping cities around the world prepare for, withstand, and bounce back from the ‘shocks’ – catastrophic events like hurricanes, fires, and floods – and ‘stresses’ – slow-moving disasters like water shortages, homelessness, and unemployment – that are increasingly part of 21st century life.

“In an increasingly complex and challenging world, cities need partnerships with leading companies like AeroFarms to help build a global resilience movement particularly for food security, just when it is needed most,” said Michael Berkowitz, President of 100 Resilient Cities.

Strategic Platform Partners are dedicated to providing 100RC network cities with solutions that integrate big data, analytics, technology, resilience land use planning, infrastructure design, and new financing and insuring products. Other 100RC Platform Partners include Microsoft, The World Bank, Ernst & Young, Siemins, Cisco, The Nature Conservancy, Save the Children, and World Wildlife Fund.

For more information, visit: www.100ResilientCities.org.

About AeroFarms

Founded in 2004 and having built 9 farms to date, AeroFarms® is on a mission to fundamentally change the way the world thinks about agriculture by building, owning, and operating indoor, vertical farms that grow flavorful, safe, healthy food in a sustainable and socially responsible way. AeroFarms patented indoor vertical farming systems make year- round harvests with peak flavor possible while disrupting the traditional distribution channels that lead to massive carbon emissions and food waste. AeroFarms is able to bring the farm to the consumer while mitigating the food safety and environmental risk of commercial field farming.

Obama Gave His First Speech Abroad, Post-Presidency, at Seeds&Chips

Obama Gave His First Speech Abroad, Post-Presidency, at Seeds&Chips

Former U.S. President Barack Obama spoke abroad for the first time since leaving office in January 2017. Hundreds of people attended his keynote speech at the Seeds&Chips Global Food Innovation Summit in Milan, Italy. Obama, dressed in an unbuttoned collar rather than his usual tie, began with remarks about his agricultural policy achievements and why food issues are intriguing to him.

“It is possible for us to make real and steady progress over the next few years,” former President Obama stated. “The path to a sustainable future will require better seeds, better storage, crops that grow with less water, and crops that can grow in extreme climates.”

Obama sat down with one of his advisors and former White House chef, Sam Kass. They discussed topics ranging from innovations in the food sector to the problem of food waste. They also talked about issues like the rise in global sea levels, clean energy, and the future of personalized medicine.

The focus of the 2017 Seeds&Chips Summit is about finding and promoting innovative agricultural solutions for a growing population. Obama stated, “Politicians can help guide change but change is going to happen by what people do every day. Essentially, millions of decisions are being made daily that influence our society.”

Later, he added, “If you want to make progress in food, you have to take into account the farmers themselves. Of course, much of agriculture is dominated by big business, but small and medium-sized farms need to be involved in change, as well. These farmers feel that they are always just a step away from losing their farms. If you put an environmental political agenda over these farmers’ economic prosperity, they will resist changing how they grow crops.”

According to Obama, right now he is writing his third book and enjoying being in his own house again. He has spent much of his time strategizing with former First Lady Michelle Obama about their next phase of work. Obama plans to set up a premiere institution in America that teaches the next generation of activists.

7 Innovative Solutions That'll Help Us Combat Climate Change & Give Us A Chance At Survival

7 Innovative Solutions That'll Help Us Combat Climate Change & Give Us A Chance At Survival

MAY 10, 2017

If there ever was a time to innovate, it is now.

The threat of climate change has sprung several architects and designers into action to devise alternatives that work for everyone. Most of these ideas will be taken to fruition in the future to counter every ill-effect caused by global warming.

These 7 solutions will tackle sea level rises, greenhouse emissions, and the changes in rainfall and temperatures. Based on revolutionary technologies, these solutions will give us hope for survival.

1. Skyscrapers that rotate

A building that can self-sustain using the energies present in nature has to be one of the most intelligent solutions to climate change.

DYNAMIC ARCHITECTURE GROUP

Already under construction in Dubai, a rotating skyscraper designed by David Fisher will power itself with terrace-mounted solar panels and 79 horizontal wind turbines that will be placed between every storey. The focus here is on solar-powered panels wherein the energy will be clean and devoid of emission.

2. Crops that beat the heat

Traditionally, selective breeding methods have helped crops adapt to different climates. But the need to have drought- and heat-resistant crops is the need of the hour.

BLACK GOLD

Scientists believe that genetic engineering is a great solution for driving characteristics from drought-tolerant species and introducing them into crops. While drought-resistance varieties of maize are being tested in Canada, drought-tolerant wheat is being tested in Egypt.

3. Skyscrapers that are farms

Climate change is making it difficult for crops to grow in a healthy environment and to slow the pace of this disintegration, vertical farms are one of the best ideas anyone has had in a very long time.

PAWEL LIPIŃSKI AND MATEUSZ FRANKOWSKI

Vertical gardens with hundreds of species of plants have already become a reality in places like Bengaluru and China. Now the focus is on the farms - one is being planned in Africa where a skyscraper of crops will aim to bring Green Revolution to the sub-Saharan Africa.

But what these farms will really achieve is this - solar-powered lighting, healthy crop cultivation, protection of crops from floods and droughts, and prevention of water and resource wastage.

4. Air conditioners that use solar energy

In a resource limited world that is being consistently pushed into the arms of climate change, we need to think bigger and better. To that end, solar-empowered air conditioners are the next big change we must accept.

INFO-OGRZEWANIE

Solar-enabled air conditioners continue to cool even when the sun is at its peak and even provide hot water. By using thermal energy, the system compresses air that sprays refrigerant out of a jet. In the process, once this refrigerant evaporates, it sucks in heat.

5. Houses that float

The sea level is expected to rise by a metre or more by the year 2100. Taking that into consideration, low-lying areas such as Bangladesh, Australia, and the Netherlands will face great peril.

INHABITAT

Scientists think that houses, communities, and even cities will be "rethought" so that they can withstand a dangerous rise in the sea level. The Netherlands has created what is known as amphibious homes that are anchored to a vertical pile and come equipped with hollow concrete cubes giving the houses the buoyancy they need to withstand a five-metre rise in the sea levels.

6. Artificial glaciers

Our glaciers are melting and cracking with alarming speed, aiding toward the rise in sea level and dwindling the supply to agricultural lands. Chewang Norphel, who is a retired civil engineer, came up with a genius idea to use artificial glaciers to keep the water supply alive especially in summers.

INDIEGOGO

A resident of Ladakh, Norphel's system pumps water into shallow pools that have rocky embankments. In winters, these pools freeze and once water is added, they gradually form a sheet of ice. In summers, the water melts and aids the sowing of crops.

7. Cities that float

Belgian architect Vincent Callebaut's intelligent design for a floating city has grabbed eyeballs. His floating sustainable city will be based on a giant lily pad, which according to Callebaut, will win us our fight against rising sea levels.

VINCENT CALLEBAUT

This floating city will be home to 50,000 climate refugees. It will help in collecting their own rainwater into a centralised lake system which in turn will help in generating power from renewable sources such as the wind, waves, and solar power.

Climate change is a challenge that needs to be tackled head-on but that effort just can't be the responsibility of a few. We must join forces to either take forward these initiatives or come up with our own solutions to extend the life of our beautiful planet.

Harris County Pushes Vertical Farming Course

Harris County Pushes Vertical Farming Course

By Mihir Zaveri

Published 10:57 am, Wednesday, May 10, 2017

Photo: Michael Ciaglo, Staff

Sprouts grow at Moonflower Farms, which uses hydroponics and is Houston's first commercial indoor vertical farm.

Harris County wants to develop a training program on indoor, vertical farming as part of its effort to reduce childhood obesity in north Pasadena.

Commissioners Court this week approved an agreement with the non-profit Association for Vertical Farming to develop a one-semester course that could be taught at an indoor farm in Pasadena. The county has been working with the city of Pasadena to set up the effort.

"The purpose of the training is to teach students and residents about the science and technology of various methods of producing healthy food," county documents state.

The county will pay the association $25,000 for implementing the course.

The industry is extremely small in Texas and the Houston area. But it could be growing.