Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Future Food-Tech Is Returning to New York City

Future Food-Tech Is Returning To New York City

The Future Food-Tech Summit is returning to New York City on June 7 and 8, 2017. Investors, start-ups, technology companies, and food and ingredients manufacturers will convene to develop solutions to meet the global food challenge during the two-day event.

Among this year’s Future Food-Tech speakers are Andrew Ive of Food-X, David Lee of Impossible Foods, Nicholas Chia of Mayo Clinic, Zachary Ellis, Jr., of PepsiCo, and Susan Mayne of the Food and Drug Administration.

Panel discussions will address key questions: How can we create systems that enable access to sustainable, safe and nutritious food for all? How are retailers partnering to create the right digital experience for customers? What role can restaurants have in bringing new food experiences to customers? What is the role of governments in producing dietary guidelines and supporting research and investment in alternative proteins?

The event will include panel discussions, fireside chats, networking breaks, technology showcases, and other presentations encouraging discussion around solutions to meet the global food challenge.

Future Food-Tech is an annual event which is held in London, New York City, and San Francisco. The Summit is intended to create a forum for networking, debate, discussion, and learning while giving new food innovators the opportunity to pitch their early to mid-stage companies to an audience of global food businesses, technology integrators, and venture capital investors.

If you have a great story to tell, a game-changing solution to showcase, or would like to share your expertise on one of the panels, please call Rethink Events on +44 1273 789989 or email Stephan Groves for more information.

Click here to register for Future Food-Tech NYC.

First Large Scale Commercial Vertical Farm in Europe To Be Set Up in The Netherlands

First Large Scale Commercial Vertical Farm in Europe To Be Set Up in The Netherlands

Farm to serve one of Europe’s biggest supermarket chains with fresh-cut lettuce grown using LED horticultural lighting

Eindhoven, the Netherlands – Philips Lighting (Euronext Amsterdam ticker: LIGHT), a global leader in lighting, today announced that Staay Food Group, a leading fresh fruit and vegetables company, is building the first of its kind vertical farm in Europe, in Dronten, the Netherlands, which will use Philips GreenPower LED horticultural lighting. The facility will serve one of Europe’s biggest supermarket chains and will be used for testing, and optimizing processes for future, large vertical farms.

Ahead of new legislation

The 900m2 indoor vertical farm will have over 3,000m2 of growing space and produce pesticide-free lettuce. With upcoming stricter regulations on the residual pesticide levels in a bag or bowl of lettuce, retailers will need to provide exceedingly high quality, pesticide-free lettuce.

Defining growth recipes

Staay, Philips Lighting and vegetable breeder Rijk Zwaan collaborated and undertook intensive research over the past three years to determine the best combination of lettuce varieties and growth recipes to improve crop quality and yields. Having the right growth recipe prior to the start of operations at the vertical farm will help Staay achieve a faster return on investment.

“Our plant specialists at our Philips GrowWise research center in Eindhoven are testing seeds from a selection of the most suitable lettuce varieties, to define the best growth recipes and to optimize crop growth even before the farm is running,” said Udo van Slooten, Managing Director of Philips Lighting Horticulture LED Solutions.

Sustainable growth

“Producing lettuce for the fresh-cut segment indoors not only means avoiding all pesticides, it also means a much lower bacterial count and therefore longer shelf life at the retailers. With the lettuce being packaged at the same spot as where it is grown, we save on transport before distribution to retailers,” says Rien Panneman, CEO of Staay Food Group. “Also, by avoiding weather fluctuations, we maintain an optimized and stable production environment to guarantee consistent and optimal product quality.”

Looking for the best varieties

Wim Grootscholten, Marketing and Business Development Manager of Rijk Zwaan, worldwide market leader in lettuce seeds said: “The tests we are conducting within this project are enabling us to identify which varieties are optimal for growing in a vertical farm, and also which varieties offer the best taste and texture. It will help us with our continuous challenge to offer solutions for the growing world population. We believe that vertical farms will become increasingly important, because in the future we see more economic and environmental pressure to produce fruit and vegetables, such as lettuce, closer to where end-customers are located.”

First of its kind

The vertical farms in Europe, using LED-based lighting have so far been research centers or specialist producers serving restaurants. The new Staay facility in Dronten will be the first in Europe to operate commercially, serving large-scale retail. The facility will start operations in the second half of 2017.

About Philips GrowWise

Philips GrowWise Center in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, is the largest research facility of its kind with a total growing surface of 234m2. Here, Philips Lighting’s researchers trial a variety of crops under different LED lighting and climate conditions to help determine their economic potential. Vertical farming investors and operators can visit the facility to see demonstrations of different vertical farm technologies, taste crops grown under LED lighting and discuss the economic viability of the technology used.

For further information, please contact:

Philips Lighting Global Media Relations

Bengi Silan Genc

Tel: +31 6 25441798

E-mail: bengi.genc@philips.com

Philips Lighting; Horticulture LED Solutions

Daniela Damoiseaux, Global Marcom Manager Horticulture

Tel: +31 6 31 65 29 69

E-mail: daniela.damoiseaux@philips.com

Fresh-Care Convenience (member: Staay Food Group)

Marco Kleijn, Managing director Fresh-Care Convenience

Tel: +31 321 382 308

E-mail: marco.kleijn@fresh-care.nl

www.staayfoodgroup.com

Rijk Zwaan

Ton van Leeuwen, Communication Specialist

Tel: +31 174 532 487

E-mail: t.van.leeuwen@rijkzwaan.nl

www.rijkzwaan.com

About Philips Lighting

Philips Lighting (Euronext Amsterdam ticker: LIGHT), a global leader in lighting products, systems and services, delivers innovations that unlock business value, providing rich user experiences that help improve lives. Serving professional and consumer markets, we lead the industry in leveraging the Internet of Things to transform homes, buildings and urban spaces. With 2016 sales of EUR 7.1 billion, we have approximately 34,000 employees in over 70 countries. News from Philips Lighting is located at http://www.newsroom.lighting.philips.com

About Staay Food Group

Staay Food Group is the fresh fruit and vegetables company in which centralized policy, marketing and sourcing control is supplemented by local expertise in growing and sales. Since 1946, we have delivered a wide range of excellent quality fresh fruit and vegetables worldwide. In response to supply chain integration, Staay Food Group positions itself closer to the growing process by cooperation and participation. Our regional offices closely monitor the growing process and the direct deliveries to customers.

About Rijk Zwaan

Rijk Zwaan develops vegetable varieties and produces seeds, which it sells in more than 100 countries. The family-owned company is amongst the top five in the global vegetable seed market and is characterized by a people-focused approach. More than 2,600 employees in over 30 countries work enthusiastically to provide products and services that add value for the market. The company has its headquarters in De Lier, The Netherlands.

Vertical Farming Grows Up And Comes Of Age

Vertical Farming Grows Up And Comes Of Age

Growing food without sunlight or soil is now a reality, but the economics leave little room for error

By Jennifer Blair Reporter

Published: April 25, 2017

Partners Wayne Lohr and Ulf Geerds have turned their extensive experience in agriculture and horticulture into a growing vertical farming venture near Olds. Photo: Jennifer Blair

Olds-area greenhouse operator Wayne Lohr and business partner Ulf Geerds are dreaming big — they want to grow an acre of strawberries.

That may not sound like a big deal until you consider that acre will take up just 360 square feet and produce strawberries year round. And even though they’re grown in racks on a shed, these berries will, the duo says, taste just as good as ones picked fresh in the field on a nice summer day.

“They taste like they’re from the field because they actually get the same treatment as from the field. We mimicked the environment that’s outside,” said Geerds.

“At the end, you’ll end up with a crop that has the same taste as from the field, but you can have it year round.”

The duo is talking about vertical farming, a relatively new industry birthed by the advent of LED lights and ‘aeroponics’ — rather than soil and sunlight — to produce fruit and vegetable crops in a small indoor area.

What was, until fairly recently, the stuff of science fiction is now a reality. Sales of produce grown via this method topped US$1 billion in 2015, and with production increasing by nearly 30 per cent annually, sales are forecast to surpass $15 billion by 2025.

And although it’s touted as a way to grow food in cities (as well as in countries where land is in short supply), vertical farming has also arrived in Alberta. And it’s winning over traditional growers such as Lohr and wife Carolyn, who have been in the greenhouse business (mostly growing ornamentals) since 1982. They got into vertical farming a year and a half ago, forming Lohr-A-Lee Indoor Gardens with Geerds and his wife, Sangeetha Varghese.

They started small, with two integrated upright systems purchased from Indoor Farms of America. The vertical panels take up a floor area of about 16 square feet in one of Lohr’s outbuildings, and have 650 plants in total. That’s an incredibly dense 40 plants per square foot of floor space — normally strawberries need one square foot per plant. At that density, their plan to scale up to 360 square feet will give them the equivalent of an acre of strawberries. (Aeroponics means there is no growing medium and roots are kept moist by misting.)

Lohr-A-Lee Indoor Gardens started small with its system, with plans to scale up with an additional 24 panels in the next few months.photo: Jennifer Blair

The pair has tried their hand at lettuce, basil, kale, arugula, Swiss chard, and bok choy, but so far, strawberries are the real star. There are no weather, disease, weed, or insect pressures, and with “total control of the environment,” the strawberry plants will grow for up to 14 months before needing to be replaced. Normally, the growing season for strawberries is two months, so the potential yield per plant is much higher.

“Effectively, you create an environment that’s consistent, so as far as this plant’s concerned, it’s July 15 every day,” said Lohr. “The target is to get four pounds per plant per year. We feel that that’s more than achievable. That’s the target. The goal is to beat it.

“We don’t need to import this stuff. We can grow it here.”

‘Lots of unknowns’

Despite their belief in vertical farming’s future, both men warn that this is not a way to make a quick buck.

That view is echoed by horticulture consultant Cees VandenEnden, owner of HortiSource Consulting in Mountain View County.

“I truly believe that 50 per cent — or maybe even more — of the startups will not see their fifth anniversary,” VandenEnden said at a workshop last month. “There are plenty of opportunities. I’ll be the last one to say this is not working. But there are some big question marks.”

But VandenEnden is being “optimistic,” said Lohr, who expects 80 to 90 per cent of startups will fail in their first year.

While vertical farming has many attributes — including a reduced carbon footprint, zero pesticide use, high nutritional value, good water-use efficiency, and local production — anyone taking a “romanticized” view will be in for a rude awakening, said Geerds.

VandenEnden agrees.

“There’s a lot going on, and I think it has a lot of potential — it’s ‘sexy,’” said VandenEnden. “In the public mind, local produce and knowing your producer is good.

“(But) this piece of the industry is attracting people who have no agricultural background and no growing knowledge. Your learning curve is tremendous and very costly. There are hyped-up expectations, and your startup cost is high. Making an income is not easy.”

In addition to the typical challenges associated with agriculture, such as labour and marketing, vertical farming comes with its own set of problems, including picking the right growing system, climate controls, light sources, watering systems, and product mixes.

“There’s a lot of thinking and problems to solve,” said VandenEnden.

“At this point in time, it’s new, so we do not know what works and what doesn’t,” added Geerds.

Ready for takeoff

Figuring out the market is even trickier. Geerds points to lettuce, which is an “easy” crop to grow.

“Lettuce grows very well in here. In 26 days, we have a crop that we can sell, but the demand is not there,” said Geerds. “We want to grow what the market wants. Strawberries make a lot of sense to us because there’s a high demand and the quality is very poor from the imports.”

Lohr and Geerds have partnered with a retailer for “significant volumes of strawberries weekly” for a small price premium.

“We’re getting a reasonable premium over what they’re paying wholesalers, but it’s not huge,” said Lohr. “Economics will ultimately take the premium away, so it comes down to production efficiencies and cost efficiencies.”

VandenEnden predicts the fledging industry will quickly scale up.

“It took over 100 years for the greenhouses to go from small entities to the big greenhouses you see nowadays,” he said. “But (vertical farming) will not take 100 years to get to that point. It’s probably closer to five years or maybe even faster.

“When that volume comes on the market, your premium prices are gone. You’ll have to produce for regular market prices.”

Competition is already growing in Alberta, he added.

“I was surprised to learn how many people are already doing this in Alberta. That will only increase,” said VandenEnden. “Big producers will develop fairly soon, and they will basically drive the prices.”

When that happens, production will be “the least of your problems” when compared with marketing, he said.

“It takes time to grow, but it takes a lot of time to market as well,” he said. “I’ve seen very few people who are excellent at growing and do a good job of marketing, too. Most of the time, one of the two is mediocre.”

But ultimately, marketing vertically farmed produce is much the same as marketing any other crop, said Lohr.

“Know what it costs you to produce it, know what kind of returns you want, and that tells you what price you need to make money.”

A costly venture

Production costs will vary based on the crop and the system used to grow it.

“If a traditional crop costs $1 to produce, the closed environment systems are costing between $1.40 and $2,” said VandenEnden. “That’s something we have to work on because that is not sustainable.”

Generally, the cost of equipment is related to the size of the system, he added, and there will be power and labour costs on top of that.

“With the right setup, there are good prospects, but what is the right setup? You need to go over that in your mind to make the right decision,” said VandenEnden.

Geerds agrees.

“You can pretty quickly sink a lot of money into the system, and if you don’t do it right, you will definitely lose.”

Producers should look at the price per square foot of growing area rather than simply the price per square foot when costing out a system, said VandenEnden. Because vertical panels do more with less space, the growing area square footage is typically about double the actual square footage. The panels at Lohr-A-Lee Indoor Gardens cost $8,800 each, and Lohr and Geerds are in the process of scaling up with an additional 24 panels.

“It’s not cheap, and it does scare the financial world. The big system that would go in the whole building is about the same dollars as a new combine today,” said Lohr.

Each vertical panel, which costs $8,800 each, can accommodate around 325 plants, or 40 plants per square foot.photo: Jennifer Blair

“We’ve done some pretty elaborate cash flow projecting but again, you’ve got to look at this on a per-plant basis. They’re still big numbers and the bill still has to be paid, but on a per-unit basis, it’s not near as scary.

“The ROI is definitely there. You’ve just got to make it produce.”

The test unit they’ve been running for the past year has helped them verify their cost of production — data that isn’t available for this new type of farming.

“Because it’s the first commercial system that we’ll have, the next system will tell us, do we make money or don’t we?” said Geerds, adding they have a few other ideas of crops they can try if strawberries don’t pan out.

“We’ve talked to a lot of people who want to grow very big very fast. I don’t think that’s the right way to approach it. You have to find the sweet spot. You don’t want to be too small but because the science is just developing, we have to really see where the sweet spot is. We’re not sure what that is yet.”

Lohr’s advice is to “start small and learn as you go.”

“Do your homework. Otherwise, there’s going to be a lot of roadkill.”

Vertical Farming: A Better Option

Vertical Farming: A Better Option

By Emily Williams, Columnist | Apr 25, 2017 | Opinion, Opinion Columns |

We need to rethink industrialized factory farming and quick. The agricultural revolution boomed back in the 18th Century which allowed the industrial revolution to change the world we lived in. So, this is a good thing with more access to food, food produced on higher levels and a decline in world hunger, right?

Wrong.

The agricultural revolution not only ruined the society humans had been living in for thousands of years, but it took our environment into a downward spiral that we may not fix in time. The agricultural revolution sparked war between mankind on drastic levels since it was one of the first times we as a species started assigning ownership to land.

If we weren’t killing each other, the diseases spread by factory farming were. The domestication of animals was needed for living purposes, but on the massive levels we’ve allowed to be perceived as appropriate have caused an influx of diseases carried by our animal friends.

Influenza, TB, smallpox, Measles and even the common cold are all linked back to the domestication and farming of livestock. But let’s argue for a second, the domestication and cultivation of animals in small populations allowed the human population to grow. That’s great, we’re living and able to reproduce at rates higher than we were dying.

But we were still dying. Hunter and gatherers shifted camps quickly and effectively. The quick rise in populations allowed us to establish villages and cities which ended up doing more harm than good. We created perfect living petri-dishes for microbes and diseases to spread. We may have been reproducing at large rates due to the advancements made with farming and domestication of meat, but death was occurring at the same rate. Our life-span declined drastically for a long time.

Sounds great.

We’ve moved on from disease altering life-spans and have outsmarted microbes like the common cold and smallpox for the most part. What has factory farming done to the environment? Not only did we introduce foreign species of plants and grasses but we allowed our carbon footprint skyrocket with meat production worldwide having quadrupled in the last 50 years.

Globalagriculture.org breaks it down for us easily: in 2014 meat production reached a high of around 315 million tons. An estimation of 450 million tons will be produced by 2050 yearly. Cows, pigs and chickens, the top three livestock handled in factory farming, have increased by over 50% percent in population for each animal, chicken an upward of 114%.

In 2016, 164 million metric tons of CO2 and methane gasses were produced by livestock in the world, and meat makes up 47.6% of greenhouse gasses from average food consumption based on the factsheet produced by the University of Michigan in August 2016 for U.S. households.

So, what is the future of farming if we want to somehow protect our environment that is deteriorating away? The future of farming is: well… not any kind of farming we’ve become comfortable with. Farms are businesses, and ones that are becoming less and less valuable unless you’re at the head of a factory farm rolling in the bundles of money you make. It’s also clear that as a society we are obsessed with technology.

Our world is crying out for help in the way we’ve destroyed it, and our global size is demanding a new revolution in our agricultural system. The technology is here, we just need to stand behind it and support it. Companies like AeroFarms, FreightFarms, and BoweryFarming have the right idea.

They’ve taken farming on land and put it inside. Vertical farming is what we need, and it works. It allows produce to be aligned in a systematic way for the purest and cleanest forms to be grown. Conditions can be manipulated for produce to be grown all year long and without the use of pesticides and fertilizer since variables can be changed and controlled easily.

These farms are able to exist in any urban environment, unlike the agricultural system we have now that takes up hundreds of acres. Not only is it using less space, farming like this uses less resources too. Bowery states they use 95% less water than traditional agricultural farming and produce 100x more on the same footprint of land.

Less CO2 emissions, less harm with fertilizers and pesticides and a more effective urban setting with farming is what we need to help the environment. There would be less demand for deforestation, and species affected by pesticides like the bees and butterflies would be able heal.

Let’s take a stance against factory farming and look at what we can do to change the way we’re treating the world. Start buying from your local farmer’s market, Oxford is a fantastic place to start. Findley Market isn’t a far drive either! Decreasing your meat intake by even one day a week and combining it with buying produce at a local market and these steps with help us heal the environment we’ve … well, trashed.

taylo193@miamioh.edu

This Incredible Vertical Farm Skyscraper Could Feed An Entire Town

Every year, the design magazine eVolo holds a competition for the most ground-breaking skyscraper concepts.

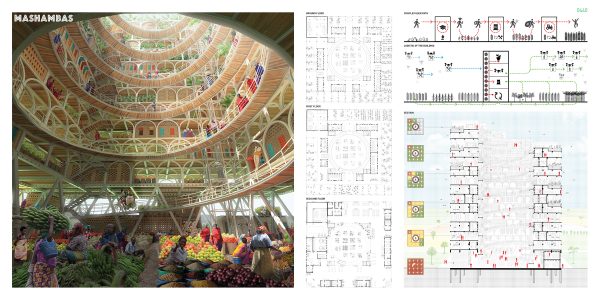

This year's first place winner is the Mashambas skyscraper, a vertical farm tower that would be able to feed an entire town in sub-Saharan Africa. The conceptual skyscraper could also be disassembled, and moved to different locations where communities need it.

This Incredible Vertical Farm Skyscraper Could Feed An Entire Town

- Leanna Garfield

- Apr. 25, 2017, 10:58 AM

Pawel Lipiński and Mateusz Frankowski

Every year, the design magazine eVolo holds a competition for the most ground-breaking skyscraper concepts.

This year's first place winner is the Mashambas skyscraper, a vertical farm tower that would be able to feed an entire town in sub-Saharan Africa. The conceptual skyscraper could also be disassembled, and moved to different locations where communities need it.

Designed by Polish architects Pawel Lipiński and Mateusz Frankowski, the tower would grow produce on the upper floors and would come with fertilizer and seeds. The other floors would feature kindergarten classrooms, a doctor's office, and even a docking port for drones that would deliver food to hard-to-reach areas. The ground floor would include an open-air market, where farmers could sell their crops.

Part of the tower would be made of modular pieces, which would allow it to be taken apart and transported somewhere else. (Though, the designers do not say how long that process would take.)

Pawel Lipiński and Mateusz Frankowski

"The main objective of the project is to bring this green revolution to the poorest people," Lipiński and Frankowski write. "Giving training, fertilizer, and seeds to the small farmers can give them an opportunity to produce as much produce per acre as huge modern farms."

Its name, Mashambas, is a Swahili word that means cultivated land, Lipiński and Frankowski write. The goal of the tower would be to bolster agricultural opportunities and fight hunger in impoverished towns in African countries.

Pawel Lipiński and Mateusz Frankowski

"When farmers improve their harvests, they pull themselves out of poverty. They also start producing surplus food for their neighbors. When farmers prosper, they eradicate poverty and hunger in their communities," the designers write.

Though he share of Africans living in poverty declined from 56% to 43% from 1990 to 2012, many more African people are poor today due to population growth, according to a recent World Bank report.

"Today hunger and poverty may be only African matter, but the world’s population will likely reach nine billion by 2050. Scientists warn that this would result in global food shortage," the designers write. "Africa’s fertile farmland could not only feed its own growing population, it could also feed the whole world."

Pawel Lipiński and Mateusz Frankowski

Announced April 10, the tower was chosen from a pool of over 400 entries. Though the designers did not name an exact site for a Mashambas skyscraper, they said the first one could be in a town south of the Sahara desert. The design is merely a concept right now, and there are no plans to actually build one.

Though the design is certainly far-fetched, the vision behind it explores what rural farms of the future could look like.

Global Food Policy Report Spotlights Urbanization

Global Food Policy Report Spotlights Urbanization

The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) has released the 2017 Global Food Policy Report. It reviews the major food policy issues, developments, and decisions of 2016, and highlights challenges and opportunities for 2017 at both global and regional levels. This year’s report looks at the impact of rapid urban growth on food security and nutrition while considering how food systems can be transformed to improve the future.

According to IFPRI, rapid urbanization and population growth are expected to put growing pressure on the global food system, which changes how countries must achieve the United Nation’s (U.N.) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of ending hunger, achieving food security, and promoting sustainable agriculture.

A 2014 U.N. report states that by 2050, 66 percent of the population is projected to live in urban areas, bringing extra stress to agricultural production from things like environmental degradation, extreme weather conditions, and a lack of land to use for crops and livestock. Most of this urbanization will occur in developing countries, where some of the world’s largest cities are already found.

The 2017 Global Food Policy Report also presents data tables and visualizations for several key food policy indicators per country such as agricultural spending and research investment, projections for future agricultural production needs, and the current state of civilian hunger. The report asserts that the world must move forward with its commitments on the SDGs by strengthening the ties between rural and urban areas to end hunger and malnutrition.

The full report is broken up into chapters that highlight global food policies and investigates the impact of rapid urbanization on local and global food systems. Each one can be explored here. Together these chapters provide an overview of what we know about urbanization, food security, and nutrition and point to some of the most vital research and data needs.

A regional section in the report also expands upon food security in different areas around the globe. Most importantly, IFPRI suggests some policy changes countries and global leaders can implement to improve food security in the future.

In addition to detailed figures, tables, and a timeline of important food policy events in 2016, the report includes the results of a global survey on urbanization and the current state of food policy. More than 1,300 individuals representing more than 100 countries responded to the 2017 Global Food Policy Report’s survey. Seventy-three percent of respondents think the expansion of cities and urban populations will make it harder to ensure that everyone gets enough nutritious food to eat, and 60 percent of respondents are dissatisfied with both global food policies and progress in global food and nutrition security.

In the preface of the report, Shenggen Fan, Director General, explains IFPRI’s goals for this publication: “I hope this report is met with interest not only by policy makers who shape the food policy agenda, but also by business, civil society, and media, who all have a stake in food policies that benefit the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people.”

IFPRI produced the Global Food Policy Report 2017 in collaboration with the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Bioversity International, and other partners.

This Japanese Smart Farm is Getting Even Smarter

This Japanese Smart Farm is Getting Even Smarter

By John Hopton

April 21, 2017

Perfect lettuce is grown with help from robots and the Internet of Things

For all Japan’s advancements, it is still common to see older people in the country bending over awkwardly in fields, picking crops by hand – a vision of the past. Twenty miles west of Kyoto, though, stands a smart farm that’s very much a vision of the future.

SPREAD‘s Kameoka Plant grows 21,000 heads of lettuce a day using multistage hydroponics and artificial lighting.

A network of connected devices, the Internet of Things at work under the roof of one slick indoor farm, ensures full control and data analysis of variables like lighting, temperature and humidity, as well as the flow of liquid nutrients.

But, if this smart farming is not smart enough, it will soon get considerably smarter. Before the end of 2017, SPREAD will open the Techno Farm™.

The world’s first robot farm

The company envisages that its super high-tech farm will reduce running costs by around 30 percent. Most impressively, though, it will be run almost entirely by robots.

The new plant in Kizugawa, Kyoto prefecture, will produce 30,000 heads of lettuce per day, which will be tended to by robots that have been brought lettuce seedlings by stacker cranes.

The robots will take care of tasks like trimming and watering, before making sure that fully grown lettuce is harvested and delivered to the factory’s packaging line.

Several countries now have smart farms, but this will be the world’s first robot farm.

A vision of the future? Source: Wide Open Country/Twitter

SPREAD says it has, “developed the most advanced vegetable production system created by

taking advantage of the cultivation techniques and accumulated know-how with the cooperation of technology equipment manufacturers.”

The company showcased that production system at CeBIT 2017 in Hanover, Germany, last month. The opening of the plant is scheduled for winter 2017.

Is a smart farm an ethical farm?

Despite the obvious cost to jobs in the local area, SPREAD believes its methods will contribute to humanity, as well as, to technological advancement (and not just by giving us more lettuce).

SPREAD claims its mission is to “create a sustainable society where future generations can have peace of mind.”

“By developing a system that can produce high quality food, rich in nutritional value anywhere in the world in a stable way, we will build an infrastructure that can supply food to all people equally and fairly around the globe,” says the company site.

Spread says lettuce costs will be the same as regular produce. Source: Spread

Japan probably has more of a need to develop an automated labor force than most other countries do, given that its population is actually declining. Japanese people famously live long, and a future in which there are not enough younger workers to support older, retired people looms large.

Nevertheless, Spread’s global marketing manager, JJ Price, told the Guardian: “Our new farm could become a model for other farms, but our aim is not to replace human farmers, but to develop a system where humans and machines work together. We want to generate interest in farming, particularly among young people.”

The company hopes eventually to take its technology around the world. Meanwhile, Japanese shoppers can rest assured that even lettuce produced by such a futuristic smart farm will cost the same as lettuce always has.

[See More: How Agriculture Technology Has Helped Feed Our Growing Population]

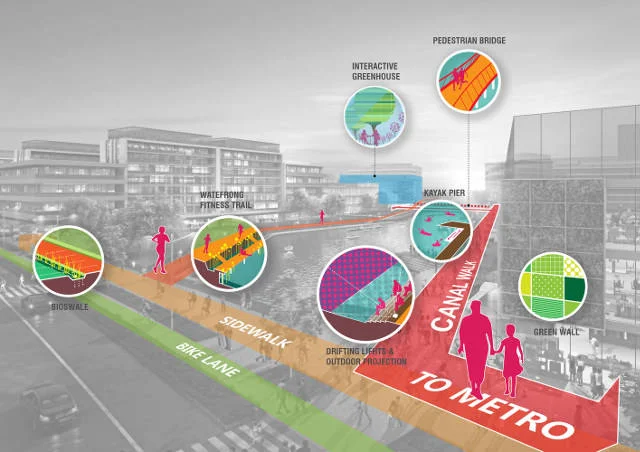

Shanghai Planning Huge Vertical Farm, Looking to change The Way It Feeds Its 24 Million Residents

Shanghai Planning Huge Vertical Farm, Looking to change The Way It Feeds Its 24 Million Residents

BY ALEX LINDER IN NEWS ON APR 21, 2017 3:30 PM

As Shanghai continues to expand outward, replacing agriculture with urbanization, a US-based design firm is looking to reimagine the way that Shanghai grows food to feed its 24 million people.

The Sasaki planning and urban design firm is turning heads with its masterplan for a 250-acre urban agricultural district in Pudong called Sunqiao, which will include, most spectacularly, towering vertical farms that grow lots of leafy vegetables

Sunqiao will include residential, commercial and public spaces integrated with an urban farm spread out across several buildings that will hydroponically produce spinach, kale, bok choi and watercress under LED lights and nutrient-rich water. Those veggies will then be sold to local grocers and restaurants.

Michael Grove, a principal at Sasaki, told Business Insider that the firm expects to break ground on the project by 2018, though there is no timeline yet. Grove said that the biggest problem they will face will be designing buildings that block out as little sun as possible.

While this project may seem ambitious, it's not quite on the level of Italian architect Stefano Boeri who wants to cover China with "forest cities" starting with the smoggy Hebei capital of Shijiazhuang

For China, the future certainly looks green.

[Images via Sasaki]

This 100-Hectare Vertical Urban Farm Will Feed 24 Million People

Shanghai is planning an urban vertical farm that will feed millions. The centre aims to educate people on the benefits of food sustainability. Sasaki Architects will create the 100-acre farm that will be interactive and hands-on. The population of Shanghai is 24 million and the company aims to feed every one of them.

This 100-Hectare Vertical Urban Farm Will Feed 24 Million People

SHAWNTAE HARRIS APRIL 20, 2017

BY: SHAWNTAE HARRIS

Shanghai is planning an urban vertical farm that will feed millions. The centre aims to educate people on the benefits of food sustainability.

Sasaki Architects will create the 100-acre farm that will be interactive and hands-on. The population of Shanghai is 24 million and the company aims to feed every one of them.

The biggest city in China lost a lot of green space due to the urbanization of the city. The city lost almost “123,000 square kilometers of farmland to urbanization – a land area equivalent to nearly the entire state of Iowa,” wrote Sasaki. The green space will fit in between the chaos of the big city and tall buildings.

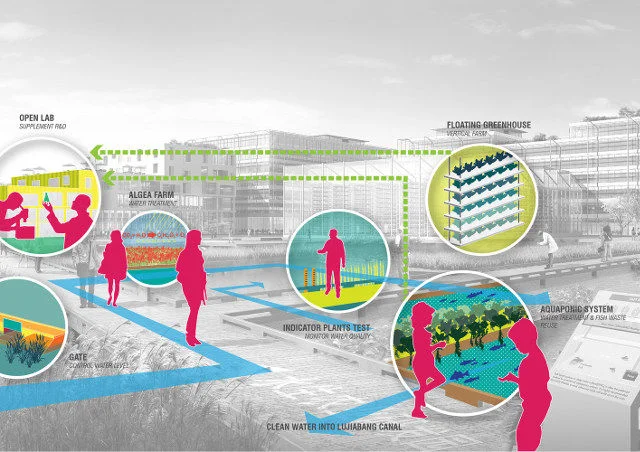

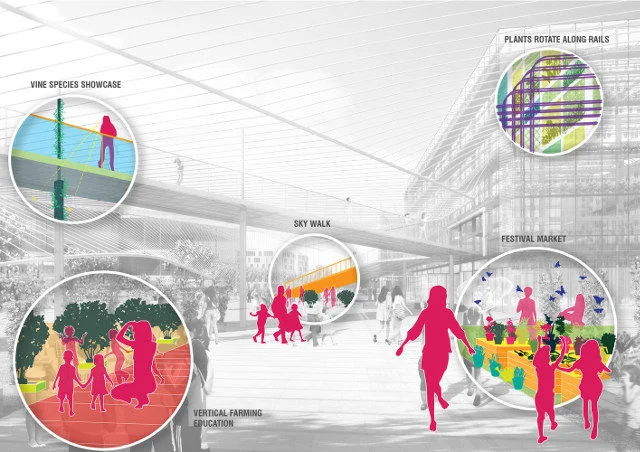

The layout will include growing centers like algae farms, floating greenhouses, vertical walls and seed libraries. “As cities continue to expand, we must continue to challenge the dichotomy between what is urban and what is rural. Sunqiao seeks to prove that you can have your kale and eat it too,” explained Sasaki to Inhabitat.

“This approach actively supports a more sustainable food network while increasing the quality of life in the city through a community program of restaurants, markets, a culinary academy and pick-your-own experience.”

The food sustainability will educate on large scale food production. There will be family-friendly events that will be held to teach kids about the values and importance of food supply.

A tour of the interactive greenhouses and a science museum will be held. As well as a tour of the sea life and plant growth to stimulate the water.

Shanghai needs more hands on food education. In recent years residents of Shanghai have turned creative to create green spaces. Many have built little gardens on their balconies or rooftop to create organic, fresh foods. Without the proper education, Shanghai food sustainability will not prosper.

Shanghai Recently Changed Food Laws

On March 20th Shanghai implemented a new restaurant food safety law, and in the last month the food hotline received over 14,000 calls. This is a 47 per cent increase from last year.

“Some businesses are trying hard to cover up violations. And tip-offs from insiders really save us a lot of time in investigation,” saidShen Ruoqing, head of the Center of Complaints and Reports at the Shanghai FDA. “The recent scandal of the famous bakery Farine is such an example.”

A reported insider told Shen one particular business was hiding expired food in a residential complex, in order to not get caught. Stricter rules will be implemented by the government soon.

In the meantime, the residents of Shanghai can look forward to the new urban farm and the benefits that it will bring to the health and well being of the community.

Netherlands Begins Construction On Europe’s First Commercial Vertical Farm

20 April 2017

Netherlands Begins Construction On Europe’s First Commercial Vertical Farm

Image source: chipmunk_1/Flickr

Europe, Worldwide, Agriculture, Tech. & Innovation, Sustainable Innovation Forum

The farm in Dronten, the Netherlands, will serve one of Europe’s biggest supermarket chains with lettuce grown using LED horticultural lighting.

To date, the only vertical farms in Europe using LED-based lighting have so far been research centres or specialist producers serving restaurants.

The new facility in Dronten – built by fresh fruit and vegetables company Staay Food Group – will be the first vertical farm in Europe to operate commercially.

The facility will serve one the continent’s largest supermarket chains in addition to being used for testing and optimising processes for future, larger vertical farms, and is scheduled to begin operating in the latter half of this year.

The 900 square metre indoor vertical farm will have over 3,000 square metres of growing space, and will use Philips GreenPower LED horticultural lighting.

As the farming happens indoors, any harmful insects or other pests will be prevented from reaching the crops – as a result no pesticides will be required in the process.

Staay and Philips Lighting collaborated with vegetable breeder Rijk Zwaan to carry out the extensive research required to determine the best combination of lettuce varieties and growth recipes in order to improve crop quality and yields

Udo van Slooten, Managing Director of Philips Lighting Horticulture LED Solutions, said: “Our plant specialists at our GrowWise research centre in Eindhoven are testing with seeds of a selection of the most suitable lettuce varieties to define the best growth recipes and to optimise the crop growth even before the farm is running”.

Wim Grootscholten, Manager of Marketing and Business Development at Rijk Zwaan, said: “The tests we are conducting within this project are enabling us to identify which varieties are optimal for growing in a vertical farm, and also which varieties offer the best taste and texture.”

Vertical farming also allows for the locating of food production close to – or even within – urban areas, where food consumption id concentrated.

Grootscholten went on to say: “It will help us with our continuous challenge to offer solutions for the growing world population. We believe that vertical farms will become increasingly important, because in the future we see more economic and environmental pressure to produce fruit and vegetables, such as lettuce, closer to where end customers are located.”

Farms located nearer consumers will help to reduce emissions and transport-related costs.

Similar facilities are also on the rise in the U.S., Vertical Fresh Farms has been farming commercially on a small scale in Buffalo, New York for a few years and Aerofarms in Newark, New Jersey, is currently developing the largest vertical farm in the world, with expected harvests of over 900,000 kilograms each year.

A report by PS Market Research projects that vertically farmed food market will take off in the next few years, generating $6.4 billion of total revenue by the year 2023.

To receive similar news articles, sign up to our free newsletter here.

How Freight Farms Is Taking Off From Boston To Canada

SEB EGERTON-READ · APRIL 19, 2017

Freight Farms sell a solution where 40’ x 8’ x 9.5’ shipping containers are outfitted innovative tools and technologies to produce consistent, high-volume harvests of leafy greens, herbs and a number of other select crops 365 days per year. Based in South Boston, this highly innovative idea was derived by co-founders Jon Friedman and Ben McNamara partly when they discovered that New England, despite its wealth and prosperity, relied on imports from outside the region for close to 90% of its food, while nearly 15% of all households reported not having enough to eat.

Using solar energy to provide the majority of the electricity required to grow crops, the containers are designed to be self-sustaining and are sold to individuals, not necessarily farmers by trade, but people who want to grow food for themselves and/or their community. The freight farm containers are small enough to be squeezed between buildings, placed at the end of parking lots, or almost anywhere in urban terrains.

The Freight Farm equipment set offers a hydroponic system, which they call the Leafy Green Machine, a soil-free growing method that utilised recirculated water with nutrient levels to grow plants. LED lights are optimised for each growing cycle, while a smartphone app called Farmhand allows the container owners to manage conditions remotely and connect with live cameras to monitor the plants.

The idea was simple. Give individuals a base and template to enable a distributed food growing network in cities. Boston may not be the obvious ‘hub’ for farming activity, but Freight Farms has spread across the north-east USA and into Canada, and there are now more than 100 of the company’s containers operating in the US alone.

The container’s growing conditions are controlled via a mobile app. Credit: Freight Farms

Investing and owning a Leafy Green Machine isn’t an inexpensive proposition, rather it’s an entrepreneurial investment opportunity. Purchasing one of the containers reportedly costs a business up to $85,000, while annual operating costs may reach $13,000. However, in a New England context where demand for locally grown food is increasing (close to 150 farmer markets operate in the state of Massachusetts alone), which offers significant business potential for new local growers, especially if they can run on low operating costs with minimal demand for land, water and chemical fertilisers.

In Boston in particular, enabling policy support has been a factor, where a recent mayor legally expanded zoning laws within the city to allow farming in freights, on rooftops and in other specific ground-level open spaces. One of the most overt examples the city’s positive stance on urban farming is at the iconic Fenway Park, where Green City Growers run the 5000-sq ft Fenway Farms above the iconic home of the Boston Red Sox.

There are legitimate questions about the role of urban farming, in particular hydroponic techniques, in the future of food. Will urban farming ever be able to grow the volume and variety needed to account for a significant percentage of the consumption of the city’s inhabitants? The answer to that question is, at best, unknown. However, there’s no doubt that hydroponic, aquaponic and aeroponic urban farming methods are gaining traction because they speak to a new way of thinking about how food is grown, distributed and consumed. In a context where land and water is scarce, and where people are increasingly inquisitive for information about what they eat, it seems increasingly likely that at least some portion of the food consumed within urban areas will be grown by a distributed network across the city in containers, warehouses and rooftops. The story of Freight Farms, and their growth across the north-east USA and Canada is just another hint in that direction.

Vertical Farming Is Taking Off: Europe’s First Commercial Vertical Farm Under Construction In The Netherlands

Vertical Farming Is Taking Off: Europe’s First Commercial Vertical Farm Under Construction In The Netherlands

April 19th, 2017 by Rogier van Rooij

Innumerable layers of vertically stacked crops, growing at insane speeds thanks to the meticulous administration of exactly the right quantities of water, nutrients, and a precise spectrum of light. Vertical Farming has so far been more successful in gaining media attention than in producing food, but this is about to change. Until recently, the only operational vertical farms were small-scale installations in research labs. Facilities aimed at developing the technology were involved, especially in refining the required lighting and climate control equipment. But this year, 2017, appears to usher in the next stage in the development of vertical farming. For the first time, larger scale commercial production is being undertaken.

Vertical Fresh Farms has been farming commercially on a small scale in Buffalo, New York for a few years, but a larger scale commercial facility is currently under construction in the Netherlands. Fruit and vegetables supplier Staay Food Group is erecting a 900 square meter vertical farm, which will have a total cultivation area of 3000 square meters.

Based in the town of Dronten, the facility is producing lettuce for ‘one of the largest supermarket chains of Europe.’ The lettuce is grown using Philips GreenPower LED horticulture lightning technology, and besides tech-multinational Philips, vegetable breeder Rijk Zwaan was involved in the development of the facility. The farm is expected to come online somewhere during the latter half of 2017.

This is good news for the environment because no pesticides are required in the process. Farming happens indoors, preventing any harmful insects or other pests from reaching the plants. Furthermore, vertical farming allows for locating food production closer to, or even in cities, where food consumption is concentrated. As a result, suppliers can save on transport emissions as well as on transport costs. The farm in Dronten packs the lettuce on location, which reduces the shipment distance even further.

The Dutch commercial facility is not the only sign that vertical farming is on the rise. Aerofarms in Newark, New Jersey, is currently bringing online the largest vertical farm in the world, with expected harvests of up to 2 million pounds a year. In Shanghai, plans have just been released for a massive 250-acre city farm, on which construction should start in 2018.

This growth of the vertical farming sector appears to be driven by two key components: an increasing demand for organic, pesticide-free food, and innovation, especially in the power consumption of the LED-technology required to grow indoors. A report by PS Market Research forecasts that the market for vertically farmed food will grow rapidly in the coming years. Their calculations give $6.4 billion of total revenue by the year 2023.

About the Author

Rogier van Rooij Optimistic, eager to learn and strongly committed to society's wellbeing, Rogier van Rooij wants to share with you the latest cleantech developments, focussing on Western Europe. After graduating cum laude from high school, Rogier is currently an honours student at University College Utrecht in the Netherlands.

Bolloré Logistics Korea Installs Urban Farm

Bolloré Logistics Korea Installs Urban Farm

The company installed an urban farm on its office rooftop building in Seoul, South Korea, as part of the Bolloré’s initiative to promoting “Green Projects” and protecting biodiversity.

April 18, 2017 By Denice Cabel

Bolloré Logistics Korea recently installed an urban farm on its office rooftop building in Seoul, South Korea, as part of the Group’s initiative to promoting “Green Projects” and protecting biodiversity.

Urban farming is a practice of growing your own food in the city, with limited space. Bolloré Logistics Korea has transformed the available rooftop space of its 6-floor office building into an urban farm, optimising current available space resources. This urban farm is split into four parcels and covers a total space of 264 sqm.

Bolloré Logistics Korea signed an agreement with Pajeori, a non-profitable organization, to maintain the farm with volunteers from the nearby neighborhood in order to cultivate each a small parcel of the Urban Garden, therefore making it a community base project as well.

The urban farm is growing organic fruits and vegetables as only natural fertilisers mostly made from rice bran are and will be used. Bolloré Logistics Korea also plans to grow traditional Korean fruits and vegetables which are not always found anymore in big retail stores, as they are difficult to grow and conserve since they require a wide range of unique resources for food and agriculture.

Some honey plants will also be planted in order to attract pollinators. Back in 2016, Bolloré Logistics Korea sponsored a wooden beehive structure (“Honey Factory”) to create awareness of the vital role of bees in our lives as they are a crucial component of food production and are responsible for a third of the food that we eat.

Bolloré Logistics Korea looks forward to harvesting the very first crops in the upcoming months. Fully in line with the biodiversity action plan put into effect within the Group, Bolloré Logistics’ biodiversity strategy has three fundamental pillars based on the ARC concept (Avoid / Reduce / Compensate):

– Embracing biodiversity as one of the company’s environmental concerns;

– Working with customers and suppliers on biodiversity issues and the impact of our activities;

– Make our sites models for biodiversity, all over the world.

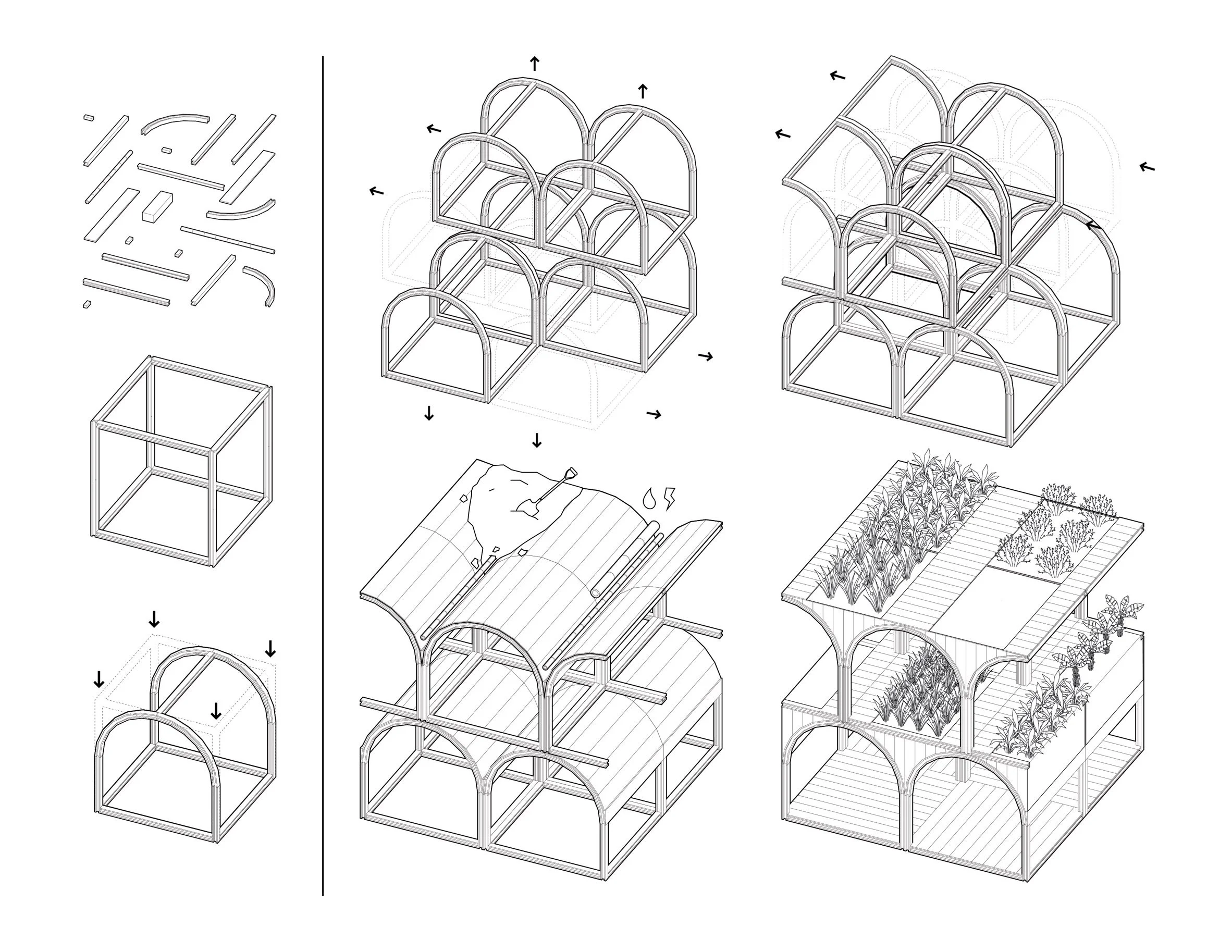

Urban Rooftop Farm Powered by Rainwater and Composted Food Waste

#LAUNCHFood innovators Marc Noyce and Brendan Condon of Biofilta shared their closed loop urban rooftop garden concept at the LAUNCH Food forum at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. The video shows a rendering of their closed loop – water, space, and time efficient rooftop concept.

Urban Rooftop Farm Powered by Rainwater and Composted Food Waste

18 APRIL 2017

#LAUNCHFood innovators Marc Noyce and Brendan Condon of Biofilta shared their closed loop urban rooftop garden concept at the LAUNCH Food forum at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. The video shows a rendering of their closed loop – water, space, and time efficient rooftop concept. “We are so excited to share the Foodwall and Foodcube garden design here, amongst some of the world’s leading innovators who are working to transform our global food system to be fairer, healthier, more nutritious and resilient,” says Biofilta’s Marc Noyce.

The system is low tech and uses rooftop rainwater and composted food waste to grow food. The two innovators hope to transform city rooftops into low cost, high yield, water efficient, ergonomic gardens for city dwellers around the world. Biofilta is bringing this system to market in the coming months, and is interested in partnering with the global housing industry in closing the loop and advancing urban farmers.

“We think with good food architecture in cities, we can repurpose food waste and rainwater runoff, and flip cities into becoming food growing powerhouses,” says Brendan Condon also of Biofilta.

With the LAUNCH Food challenge, we called for supply- or demand-side innovations with the potential to improve health outcomes by enabling people to make healthy food choices. 280 innovators from 74 countries answered our call for applications, and our panel of expert reviewers helped us choose 11 of the most promising innovations. Follow the hashtag #LAUNCHFood on Twitter and Facebook to learn about all our innovators.

LAUNCH Food is a partnership with the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s innovationXchange, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and a broad cross-sector network of key opinion leaders and industry players. We take a people-centered approach to action across the whole of the food system.

Sourced with permission from Huffington Post and @idavar

@Biofilta

Is Boston The Next Urban Farming Paradise?

The city’s healthy startup culture is contributing to Boston’s rapidly growing reputation as a haven for organic food and urban farming initiatives

The inspiration for Boston-based Freight Farms was launched after co-founders and friends Jon Friedman and Ben McNamara realized that New England currently gets almost 90% of its food from outside the region. Photograph: Freight Farms

Sunday 16 April 2017 10.00 EDT | Oset Babur

For those seeking mild, year-round temperatures and affordable plots of land, Boston, with its long winters and dense population, isn’t the first city that comes to mind.

But graduates of the city’s nearly 35 colleges and universities are contributing to the area’s growing reputation as a haven for startups challenging and transforming age-old industries, from furniture to political fundraising. The city’s strong entrepreneurial spirit, combined with progressive legislation like the passing of Article 89, has also turned Boston into one of the nation’s hubs for urban agriculture.

The inspiration for Freight Farms, an urban farming business headquartered in South Boston, was launched after co-founders and friends Jon Friedman and Ben McNamara realized that New England currently gets almost 90% of its food from outside the region, yet 10-15% of households still report that they don’t have enough to eat. The over reliance on imported produce drove Friedman and McNamara to launch a Kickstarter campaign in 2011 for their farming business, which sells freight containers to would-be farmers, many of whom aren’t necessarily farmers by trade, but are interested in contributing to sustainable living. A Freight Farms container is designed to be largely self sustained, and uses solar energy to provide the majority of electricity required to grow the crops. Julia Pope, who works in farmer education and support at the organization, says people can find the freight containers squeezed between two buildings, in a parking lot, under an overpass, or virtually anywhere in the modern urban terrain.

Freight Farms has spread north from Boston to Canada, and Pope says there are over just over 100 of the company’s container farms operating in the US alone. The company outfits each 40-ft container with the equipment for the entire farming cycle, from germination to harvest. This set of equipment, which the company calls Leafy Green Machine (LGM), creates a hydroponic system, a soil-free growing method that uses recirculated water with higher nutrient levels to help plants grow. Vertical growing towers line the inside of the shipping container, with LED lights optimized for each stage of the growing cycle. Farmers can manage conditions remotely using a smartphone app called Farmhand, which connects to live cameras inside the container.

Freight Farms has spread north from Boston to Canada, and Pope says there are over just over 100 of the company’s container farms operating in the US alone. Photograph: Freight Farms

Pope says that of customers who have purchased the LGM, over 50 have started small businesses, each consistently producing two acres worth of food year-round. One of these businesses is Corner Stalk Farm, which sells locally grown leafy greens – including kale, mint and arugula, as well as over twenty varieties of lettuce, to cater to demand at various farmers markets in Boston and Somerville, the city’s landmark Boston Public Market, and through orders from produce delivery services (such as Amazon Fresh) that are increasingly popular in cities. It’s no small feat to own and operate the LGM: purchasing one of the containers will run an aspiring business $85,000, with operating costs adding up to another estimated $13,000 per year.

Luckily, steady consumer demand, evidenced by over 139 farmers markets across the state of Massachusetts alone, help to offset the high costs to starting and running an urban farm. Hannah Brown, a resident of Boston’s North End, regularly shops at the Boston Public Market, which sells locally sourced goods from over thirty small businesses. “There aren’t many stores with really fresh produce in the immediate area, so it’s definitely filled a need for me,” she says. Brown also finds the small business owners who sell their produce at the market to be an invaluable resource: “It’s great to be able to talk with the people working the produce stands, because they can recommend what’s freshest and how to prepare it.” As a result, she says she’s taken to only buying produce that’s in season and adjusting her habits to align with what’s available to her locally.

The growing popularity of urban farming owes much to a former mayor, Thomas Menino, and one of his final acts while in office. He signed into law Article 89, expanded zoning laws to permit farming in freight containers, on rooftops, and in larger ground-level farms. Article 89 made it possible for those practitioners to sell their locally grown food within city limits.

One business that has taken advantage of Article 89 is Green City Growers, which runs Fenway Farms, is a 5,000-sq ft rooftop farm above Fenway Park. The rooftop is lined with plants grown in stackable milk crate containers, which are equipped with a weather sensitive drip irrigation system that monitors the moisture of the soil in the crates to make sure plants get just the right amount of water. Although the farm isn’t open to the general public, it is visible to fans from the baseball park, and a stop on the Fenway Park tour.

In late 2013, the landscape for urban agriculture in Boston got a lot greener with the passing of Article 89, which made it possible for those practitioners to sell their locally grown food within city limits. Photograph: Freight Farms

Boston is far from alone in passing legislation that makes farming a possibility for city-dwellers. In Sacramento, there are even tax incentives for property owners who agree to put their vacant plots of land to active agricultural use for at least five years, while the city council of San Antonio voted just last year to pass legislation that makes urban farming legal throughout city limits. And while Boston boasts home to various agricultural startups and nonprofits, entrepreneurs in other parts of the country are contributing to a national farming movement in their own ways: Kimbal Musk, brother of Tesla and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk, recently set up a container farm in an old Pfizer factory in Brooklyn, while Local Roots Farms is turning shipping containers into urban farms (using the same hydroponic method that the LGM uses) across the Los Angeles area.

As Bostonians now find themselves with a slew of new options to grow and profit from fresh produce on rooftops and in alleyways, some nonprofit organizations are looking to use urban farming as an educational asset. CitySprouts was born in Cambridge in 2001 after executive director Jane Hirschi identified what she calls “an immense need for children to understand where their food was coming from”. CitySprouts teams up with educators to set aside class time for students to cultivate gardens on school property that they can grow their own food in. There are now over 20 public schools using CitySprouts gardens in the Boston area, and more than 300 public school teachers participating in the fresh food program.

Caitlin O’Donnell, who teaches first grade at Fletcher Maynard Academy in nearby Cambridge, says the program does a great job of giving urban kids the opportunity to interact with their environment in ways they wouldn’t have otherwise, she adds. “Whether students are digging for worms, sketching roots structures, crushing apples for cider, or sampling chives and basil, their hands are busy and their senses are engaged ...what makes City Sprouts most effective (and exceptional) is that it is collaborative and flexible by design.”

Boston’s rise in the national urban farming movement also has helped to make locally grown produce more available to low-income residents. Leah Shafer recalls that she was able to use food stamps at a farmer’s market to receive half-off of her purchases of kale, blueberries, and more.

“It made it possible for me to buy organic, local produce that I otherwise just wouldn’t have been able to afford. I don’t think I would have been able to support local farmers without that discount,” she says.

First European Vertical Farm To Open in Holland

Soon, the lettuce in your salad may come from a so-called vertical farm. Vertical farming, growing fruit and vegetables in tall buildings without daylight, is on the rise around the globe. This year, the Dutch town Dronten will be home to the first European vertical farm. Staay Food Group is building a nine-story-building, in which their company Fresh Care Convenience will cultivate various types of lettuce

First European Vertical Farm To Open in Holland

News item | 14-04-2017 | 11:56

Soon, the lettuce in your salad may come from a so-called vertical farm. Vertical farming, growing fruit and vegetables in tall buildings without daylight, is on the rise around the globe. This year, the Dutch town Dronten will be home to the first European vertical farm. Staay Food Group is building a nine-story-building, in which their company Fresh Care Convenience will cultivate various types of lettuce.

Lettuce with LED lighting - Image: Staay Food Group

Climate Chambers

Each floor in the flat will have specially designed climate chambers with LED lighting, which will produce 30,000 crops of rucola, lollo bionda, lollo rosso and curly endive a week. That’s twice as many crops as can be grown in traditional farms in a week, at a rate about 3 times as fast.

Staay Food Group is investing 8 million euros in the project. A large part of the costs is for special LED lighting. Philips is developing lights that change colours, to influence the taste and the vitamin count.

The first crops of lettuce will be processed by Fresh Care Conveniencefor ready-to-eat meal salads for the German market. They will hit Dutch supermarkets soon after.

Sustainable

Vertical farming has several advantages and is sustainable. With multiple floors to grow crops, a high-rise has a large surface area in a relatively small space. In a multi-floored building, all crops are sheltered from bad weather and insects, so farmers can grow them without insecticides.

Some vertical farms use a circular system, expanding their business with fish and adding fish farms to the building. The fish excrement is then collected and used to fertilize the vegetables.

The climate chambers in Dronten are energy efficient, using less water, electricity and fertilizer than traditional farming. They aim for CO2 neutral production.

City Farming

The fact that high-rise buildings can be built in city centres is an added benefit. Fresh products can now be grown very close to the consumer. Which answers the increased demand for sustainable, locally grown products.

Vancouver Community Gardens A Gift From Developers Who Get Tax Bre

Vancouver Community Gardens A Gift From Developers Who Get Tax Break

DENISE RYAN

More from Denise Ryan

Published on: April 14, 2017 | Last Updated: April 14, 2017 2:32 PM PDT

Chris Reid is the executive director at Shifting Growth, which sets up community gardens in undeveloped properties throughout the Lower Mainland. Reid is pictured Saturday, April 8, 2017 at the Alma community garden in Vancouver, B.C. JASON PAYNE / PNG

Driving rain couldn’t keep a steady stream of urban gardeners from showing up to claim their plots at a new, temporary community garden at the corner of 10th and Alma in Vancouver last Saturday.

The transformation of a gravel lot on the site of a long-shuttered gas station was spearheaded by Shifting Growth, a Vancouver non-profit that bridges the gap between commercial property owners and urbanites eager to grow their own food.

For a modest buy-in fee of $15, gardeners at one of Shifting Growth’s urban gardens get a 4′ x 3.3′ raised box, already assembled, filled with good soil and access to water. Unlike collective community gardens governed by boards, Shifting Growth gardeners don’t have to deal with the politics of a group or commit hours to site maintenance.

“We take care of all the management. There are no work party requirements, where a lot of the complications come in,” said Chris Reid, executive director of Shifting Growth. “Most people don’t want to be responsible for a non-profit, they just want to grow food, and we let them do that.”

The 100 raised beds at Alma and 10th are on land owned by Landa Global Properties.

“The site has been empty for many years and we thought this would be a great way to give back to the community and do something useful while we go through the development process,” said Kevin Cheung, Landa’s CEO in a statement.

Shifting Growth doesn’t solicit developers because there are enough developers willing to assume the risk and responsibility for the garden projects in exchange for a tax break from the B.C. Assessment Authority. If a vacant lot houses a temporary community garden it will be taxed at a lower rate than on a business site.

Reid said the situation is a win for both the community and developer. “We try to keep it really local, so we put up a notice right by the property, in the hopes that we will get people from the neighbourhood who might live in condos or basement suites, who don’t have another option to grow their own food.”

Young plants ready for planting Saturday, April 8, 2017 at the Alma community garden in Vancouver, BC. JASON PAYNE / PNG

Reid said their land use agreements with corporations range from one to five years. “If we can get one season out of it, it’s a great engagement piece for the community. It’s a great engagement piece for the community.”

Shifting Growth has over 600 garden beds on seven properties from Dunbar to East Vancouver, False Creek to North Vancouver. Vacant residential lots don’t qualify for the same benefit through the B.C. Assessment Authority.

Shifting Growth began with a start-up grant from Vancity Credit Union.

“We had to work against some preconceived notions about community gardens, and the associated risks. We had to prove there was a model that would work,” Reid said.

An unexpected offshoot of the initiative is the success of their pre-fab raised garden boxes, which are set on pallets for drainage, which they now sell through their website shiftinggrowth.com

Reid said Shifting Growth researched and found a German community gardener making use of a hinged shipping industry box that lies flat when not in use. “We import the hinges, buy local untreated cedar and assemble them by hand in Vancouver. It unfolds in about a minute, you fill it with soil and you’re ready to go.”

Shanghai is Planning a Massive 100-Hectare Vertical Farm to Feed 24 Million People

Shanghai is Planning a Massive 100-Hectare Vertical Farm to Feed 24 Million People

International architecture firm Sasaki just unveiled plans for a spectacular 100-hectare urban farm set amidst the soaring skyscapers of Shanghai. The project is a mega farming laboratory that will meet the food needs of almost 24 million people while serving as a center for innovation, interaction, and education within the world of urban agriculture.

The Sunqiao Urban Agricultural District is composed of vertical farms that fit in nicely between the city’s many towers, adding a welcomed green counterpart to the shiny metal and glass cityscape. In a city like Shanghai, where real estate prices make vertical building more affordable, the urban farm layout counts on a number of separate buildings that will have various growing platforms such as algae farms, floating greenhouses, vertical walls and even seed libraries. The project incorporates several different farming methods including hydroponic and aquaponic systems.

The masterplan was designed to provide large-scale food production as well as education. Sunqiao will focus on sustainable agriculture as a key component for urban growth. “This approach actively supports a more sustainable food network while increasing the quality of life in the city through a community program of restaurants, markets, a culinary academy, and pick-your-own experience” explained Sasaki. “As cities continue to expand, we must continue to challenge the dichotomy between what is urban and what is rural. Sunqiao seeks to prove that you can have your kale and eat it too.”

Visitors to the complex will be able to tour the interactive greenhouses, a science museum, and aquaponics systems, all of which are geared to showcase the various technologies which can help keep a large urban population healthy. Additionally, there will be family-friendly events and workshops to educate children about various agricultural techniques.

Via Archdaily

Africa Needs Its Own Version of the Vertical Farm to Feed Growing Cities

Africa Needs Its Own Version of the Vertical Farm to Feed Growing Cities

April 10, 2017

ANALYSIS By: Esther Ndumi Ngumbi, Auburn University

The Netherlands is building its first large-scale commercial vertical indoor farm. It's expected to serve Europe's largest supermarket chains with high quality, pesticide-free fresh cut lettuce.

Vertical farms use high-tech lighting and climate controlled buildings to grow crops like leafy greens or herbs indoors while using less water and soil. Because it's a closed growing system, with controlled evaporation from plants, these farms use 95% less water than traditional farms. At the same time, most vertical farms don't need soil because they use aeroponics or hydroponic systems - these dispense nutrients needed for plants to grow via mist or water. This technique is ideal for meeting the challenges of urbanization and the rising demand by consumers for high-quality, pesticide-free food.

They're not unusual. In recent years, there's been a gradual increase in the number of vertical farming enterprises, especially in North America and Asia. In the US, Chicago is home to several vertical farms, while New Jersey is home to AeroFarms, the world's largest vertical farm. Other countries such as Japan, Singapore, Italy, and Brazil have also seen more vertical farms. As the trend continues, vertical farming is expected to be valued at US$5.80 billion by 2022.

Africa faces similar trends that demand it considers vertical farms. Firstly, it's urbanizing at a fast rate. By 2025 more than 70% of its population is expected to live in the cities. Secondly, many of these urban consumers are demanding and willing to spend much more to buy high quality, pesticide free food.

Yet, despite sharing trends that have fuelled the vertical farming movement, Africa is yet to see a boom in the industry.

A few unique versions are sprouting up on the continent. These show that the African versions of vertical farms may not necessarily follow the same model of other countries. It's important to establish what the barriers to entry are, and what African entrepreneurs need to do to ensure more vertical farms emerge.

Barriers To Vertical Farming

Initial financial investments are huge. For example, a complete modern (6,410sqm) vertical farm capable of growing roughly 1 million kilos of produce a year can cost up to $80 to $100 million.

There also needs to be an upfront investment in research. Many of the successful vertical farms in the developed world, including the one launching in the Netherlands, invest in research before they go live. This ranges from studying the most appropriate system that should be used to the best lighting system and seed varieties, as well investigating the many other ingredients that determine the success or failure of the farm.

Access to reliable and consistent energy is another barrier. Many African cities frequently experience power cuts and this could prove to be a big challenge for innovators wanting to venture in vertical farming business.

Faced with these challenges, entrepreneurs thinking of venturing into vertical farming in Africa need to put in more thought, creativity, and innovation in their design and building methods.

They need to be less expensive to install and maintain. They also have to take into consideration the available local materials. For example, instead of depending on LED lighting system, African versions can utilize solar energy and use locally available materials such as wood. This means that entrepreneurs should begin small and use low-tech innovations to see what works.

As innovators locally figure out what works best for them, there will be further variations in the vertical farms between African countries.

African Versions

In Uganda, for instance, faced with lack of financial resources to build a modern vertical farm and limited access to land and water, urban farmers are venturing into vertically stacked wooden crates units. These simple units consist of a central vermicomposting chamber. Water bottles are used to irrigate the crops continuously. These stacked simple vertical gardens consume less water and allow urban farmers to grow vegetables such as kale to supply urban markets. At the moment, 15 such farms have been installed in Kampala and they hope to grow the number in the coming years.

In Kenya, sack gardens represent a local and practical form of a vertical farm. Sack gardens, made from sisal fibres are cheap to design and build. One sack costs about US$0.12. Most importantly, they use local materials and fewer resources yet give yields that help farmers achieve the same outcomes as vertical farms in the developed world. As a result, many have turned into sack gardening. In Kibera, for example, over 22,000 households have farmed on sacks.

Also in Kenya, Ukulima Tech builds modern vertical farms for clients in Nairobi. At the moment it's created four prototypes of vertical farms; tower garden, hanging gardens, A-Frame gardens and multifarious gardens. Each of these prototypes uses a variation of the vertical garden theme, keeping water use to a minimum while growing vegetables in a closed and insect free environment.

The continent has unique opportunities for vertical farms. Future innovators and entrepreneurs should be thinking of how to specialise growing vegetables to meet a rise in demand of Africa's super vegetables by urban consumers. Because of their popularity, startups are assured of ready markets from the urban dwellers. In Nairobi, for example, these vegetables are already becoming popular.

Feeding Africa's rapidly growing urban population will continue to be a daunting challenge, but vertical farming - and its variations - is one of the most innovative approaches that can be tapped into as part of an effort to grow fresh, healthy, nutritious and pesticide-free food for consumers.

Now is the time for African entrepreneurs and innovators to invest in designing and building them.

Disclosure statement

Esther Ndumi Ngumbi does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Growing lettuce at a vertical farm.

Mashambas Skyscraper

Mashambas Skyscraper

BY: ADMIN | APRIL - 10 - 2017

First Place

2017 Skyscraper Competition

Pawel Lipiński, Mateusz Frankowski

Poland

Mashamba– Swahili, East Africa

An area of cultivated ground; a plot of land, a small subsistence farm for growing crops and fruit-bearing trees, often including the dwelling of the farmer.

Over the last 30 years, worldwide absolute poverty has fallen sharply (from about 40% to under 20%). But in African countries, the percentage has barely fallen. Still today, over 40% of people living in sub-Saharan Africa live in absolute poverty. More than half of them have something in common: they’re small farmers.

Despite several attempts, the green revolution’s mix of fertilizers, irrigation, and high-yield seeds—which more than doubled global grain production between 1960 and 2000—never blossomed in Africa, because of poor infrastructure, limited markets, weak goverments, and fratricidal civil wars that wracked the postcolonial continent.