Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Dean Martel Joins BrightFarms as Vice President of Sales

Dean Martel Joins BrightFarms as Vice President of Sales

BrightFarms is pleased to announce that Dean Martel has joined the company as Vice President of Sales. Martel will lead supermarket partnership business development, sales and account management.

Martel has more than 25 years of experience leading category growth in the consumer packaged goods industry. Most recently, he served as the Director of U.S. Retail Sales for It’s Fresh!, a food freshness technology company. Prior to his tenure with It’s Fresh!, Martel spent 16 years in category management and sales leadership positions at Fresh Express, which at the time was the nation's leading fresh salad brand. He began his career in the food industry at Kraft Foods, where he served in a variety of sales and supply chain roles.

Martel’s experience ranges from category management best practices to expertise in value added salads. He is known for building strategic relationships with key retailers in the U.S., which well-positions him to add value to the BrightFarms team during this growth phase.

With greenhouse farms built in close proximity to major metropolitan markets like Chicago, Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia, BrightFarms is currently the leader in producing local produce for supermarkets. The company plans to construct more than a dozen greenhouse farms across the country in the next three years.

“We are on a fast-track to becoming the country’s first national brand of local produce,” said BrightFarms CEO Paul Lightfoot. “Dean’s background leading high-profile teams and growth initiatives within the category adds immeasurable value to our team. We’re entering a period of serious growth as we look to bring fresh, local produce to more grocery store shelves. We are very happy to have Dean in our corner.”

This hire also allows for Abby Prior, another key member of BrightFarms leadership team, to shift into a newly created role as the Vice President of Marketing. Before joining BrightFarms, Prior served as a Director of Marketing for Bimbo Bakeries, USA.

“Joining Paul and the BrightFarms team is an incredible opportunity to be part of a leading-edge company with innovative greenhouse farming technologies and practices to help solve the lengthy food supply chain problem,” said Martel. “At the end of the day, we’re helping to deliver fresher, higher-quality produce to the grocery shelves of consumers every day, and that is something to feel good about.”

Canadian Greenhouse Cucumber Grower Prepares For Any Eventuality

Canadian Greenhouse Cucumber Grower Prepares For Any Eventuality

From storage capacity for 2 million gallons of fuel oil to multiple boilers

Leamington-based Great Lakes Greenhouses is focused on redundancy and controls to be in place to react to any unforeseen events. “We prepare for any eventuality,” says David Revington with Great Lakes. “Whatever may happen, we will continue to function and supply the highest quality greenhouse-grown cucumber to the customer,” he added.

Bunker oil as a back-up for natural gas

Greenhouses rely heavily on the supply of natural gas, but harsh winters in Leamington, ON sometimes cause interruptions of supply. Therefore, Great Lakes has two back-up tanks on the farm that each hold 1 million gallons of bunker oil. “The cost of bunker oil is four times the amount of natural gas, but security of supply is everything,” said Revington.

A huge room with multiple boilers generates the steam to heat the greenhouses. “It took us 2.5 years to get permission to build it,” shared Revington. The condenser, that was built in the Netherlands, provides significant energy savings. “With one condenser, we save four acres of energy, but now we have three condensers that we can use in the heart of winter,” mentioned Revington. As if this wasn’t enough, three natural gas generators enable Great Lakes to produce hydro. Most of the farm can run on two gas generators, but three is a safety precaution. The company has its own in-house maintenance team of 25 people who make sure everything functions the way it should.

Propagation site

Another way of taking control is a 4-acre propagation site. “The majority of greenhouse growers outsource propagation, but we feel we get to grow a better plant by doing it in-house,” shared Revington. Every two weeks, about 120,000 plants go into the propagation area and fill approximately 20 acres of greenhouses. The showpiece of the propagation area is the flood floor by European design. “It allows us to sterilize the water, which helps in preventing root diseases,” said Revington. The plants are watered as needed and the water comes up through the floor. Sprinklers are used to take the heat off the plants.

Propagation area

Organic expansion

Based on consumer demand, Great Lakes is expanding its organic program. 3.5 acres are being prepared for organic production while trials are done in a small area of the greenhouse. In the trial section, cucumbers are grown next to organic beans. The beans are needed to grow natural bugs such as thrips. Clover is used as underseeding to ‘fix’ nitrogen levels of the cucumber plants. Optimizing nitrogen levels in a natural way can result in significant savings. A unit of conventional nitrogen costs CAD 0.40 per pound whereas the organic counterpart is CAD 6.00 per pound.

Organic greenhouse

30,000 dozen of cucumbers per day

Great Lakes harvests about 30,000 dozen of cucumbers per day and product is moved the same day it is harvested. During peak season, about 250-300 laborers are involved in moving the product. The pickers play an important role and recently, Great Lakes installed scales on the picking carts. “They are tied directly to the labor system and provide the packing shed a more accurate idea of the amount of cucumbers that will come in,” according to Revington. In addition, the scales also support accountability. The system registers how many pounds each laborer picks and a bonus will be paid to the people who score above average. At the packing shed, the cucumbers go through a grading process. Based on their diameter, length and curvature, the grading system determines what packing table they are directed to.

Packing line

In addition to the organic expansion, the company also hopes to expand its conventional production from 90 acres to 120 in the next year.

For more information: David Revington |Great Lakes Greenhouses Inc.

Tel: 519-419-4937 | david@greatlakesg.com | www.greatlakesg.com

Publication date: 8/23/2017 | Author: Marieke Hemmes | Copyright: www.freshplaza.com

Urban Farming Initiative To Provide Long-Term Security For Local Green Spaces

Urban Farming Initiative To Provide Long-Term Security For Local Green Spaces

By KATHLEEN J. DAVIS • August 23, 2017

Two local nonprofits are partnering to preserve the city's urban farms.

CRISTINA SANVITO / FLICKR

In a new venture, nonprofits Grow Pittsburgh and the Allegheny Land Trust are teaming up to preserve the city's urban farms. The Three Rivers Agricultural Land Initiative will give long-term support to select a handful of garden projects in the community.

The Three Rivers Agricultural Land Initiative will buy the land of existing projects, which will be chosen by a committee consisting of members of Grow Pittsburgh, the Allegheny Land Trust and the community. Allegheny Land Trust President and CEO Chris Beichner said this step will ensure the land will be protected from future developments.

"There's no formal land agreement in many of these cases, and at any time the developer or private owner of the land could say, 'We have another use for this land now, and we want you off,'" Beichner said.

Pittsburgh is home to several food deserts, areas where fresh fruits and vegetables aren't easily accessible. Beichner said there are more than 80 urban farms in the city, and that they're a sustainable way to bring these foods to a community.

"By being able to come in and permanently protect these lands and give the volunteers and farmers the support to grow these farms, they can turn to their families and neighbors and offer these fresh foods," Beichner said.

Grow Pittsburgh is a nonprofit that "shows that food growing activities are one of the keys to building a healthy, sustainable and equitable community," said executive director Jake Seltman.

Allegheny Land Trust is a conservation land trust that acquires and protects green spaces. As a joint project, Seltman said that it was essential the community was involved in the Three Rivers Agricultural Land Initiative's decision making process, as it's often their labor that could use protection.

"We owe it to community members and to our city to make sure that the gardens can survive and thrive for many generations."

Seltman said he hopes the committee will be finalized by next growing season, so the farms can be chosen. He said the land initiative will likely prioritize farms that are currently feeling development pressure.

(Photo Credit: Cristina Sanvito/Flickr)

Will Zeal For Profits Hinder High-Tech Farming From Feeding People?

AUGUST 22, 2017 | NINA SPARLING

Will Zeal For Profits Hinder High-Tech Farming From Feeding People?

Part of the Sustainable Urban Masterplan for Shanghai, China by Except. Photo credit: Except / Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Vegetables grown on modular indoor farms in the hearts of cities may soon give roadside you-pick farms a run for their money. From produce ordered on-demand from smartphones to retrofitted shipping containers growing baby kale in the dead of urban winters, the future of farming looks ever more high-tech.

So-called vertical farming appeals to consumers devoted to clean eating and sustainable futures. Its potential to mitigate impending crises in the food system, like climate change, malnutrition and the challenge of feeding growing urban populations as the number of farmers drops worldwide, has attracted an array of investors and entrepreneurs. But can these typically venture-capital-backed businesses — which currently grow a tempting array of greens and herbs but little else— disrupt the massive and influential reach of big agriculture? That is far from certain.

An Urban Forest of Food

.In the future envisioned by Dr. Dickson Despommier, author of Vertical Farming: Feeding the World in the 21st Century, cities and the surrounding communities will house intensive agricultural production.

“They liken Manhattan to a forest of skyscrapers,” he told WhoWhatWhy, “I love that image because, yes, let’s make Manhattan imitate a real forest!”

He sees skyscrapers where basements harbor aquaculture tanks filled with tilapia, swimming laps under beds of microgreens whose roots take up the nutrients the fish waste provides. Heirloom tomatoes, sugar snap peas, and scotch bonnet peppers will grow on upper floors in beds programmed to provide ideal conditions through meticulous micronutrient dosage, light exposure and humidity controls.

A central column will house a massive freight elevator and utilities that allow the building to recycle the vast majority of its water. The behemoth will run on renewable energy. Vertical farmers share a common sentiment to, as Dr. Despommier put it, “get the hell off the grid.”

Investors and venture capitalists in the indoor agriculture space share his conviction. Many of the same companies that funded giants in the app-driven technology space underwrite vertical farm ventures: Bezos Expeditions, part of the empire of Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, has invested in Plenty, a Silicon Valley-based vertical farming company. In June 2017, Plenty purchased Bright Agrotech, producer of the leading vertical farm hardware, the trademarked ZipGrow tower system. Square Roots, a Brooklyn vertical farm incubator and entrepreneurial space, is led by founder Kimbal Musk, the younger brother of Elon Musk of Tesla and SpaceX fame.

But the dream of this type of farming clashes with the way farming actually operates today. Agribusiness, supported by the federal government, is focused on raising a few cash crops. Of the $25 billion spent yearly on farm subsidies, 75 percent goes to just 10 percent of farmers. That 10% represents large scale commercial farms growing commodities for the global marketplace, raising livestock on feedlots, and turning considerable profits.

“People aren’t farming to raise food for people,” Despommier said, “they are raising crops to make money. It’s all about which crops the world needs rather than us.”

Federal support for agriculture was born in the 1930s to maintain a degree of stability in the business of farming commodity crops. A powerful lobby and a revolving door between industry and public office has reinforced this relationship between the government and agribusiness. The industry’s profits come both from turning heavily subsidized commodity crops like corn and soybeans into value-added goods like high fructose corn syrup and soy milk, and from exports into the global commodity marketplace.

This has been instrumental in creating a food system saturated with highly processed goods lacking in nutritional value. It does a poor job of nourishing people while providing an abundance of cheap calories. Moreover, it pads the pockets of a minority of farmers and transnational corporations like Bayer and ConAgra.

Inside AeroFarms

.Can the vertical farming industry challenge this hegemony? To see one of the new farms up close, I scheduled a visit to AeroFarms, a 78,000-square foot facility in Newark, New Jersey. I arrived at the site early in the morning. I found a landscape where nothing was growing. A massive off-white box constructed of corrugated metal siding sat set back from the sidewalk. It was unmarked.

Adjacent to the site at 212 Rome Street is US Route 1, the eastern boundary of Newark’s Ironbound District — named for the two railroads and two highways that define its limits. Behind the big white box was a massive shed filled with dirt, a wall covered in graffiti, and nothing else. Across the parking lot was a cinderblock bungalow with yellowed glass windows and an AeroFarms logo on the door. I peered through a window but saw no one.

Around the back of the sheet metal structure was an unmarked door. I opened it and found myself in a small room that welcomes workers and visitors alike. There I was greeted by Marc Oshima, the chief marketing officer of AeroFarms.

Before I could enter the heart of the operation, Oshima had me take off all jewelry, sign a food-safety compliance form, don a hairnet and navy-blue disposable lab coat, pass through a clean room, like the ones found in computer-chip factories, walk over rubber mats doused in sanitizer to remove harmful bacteria from the soles of my shoes, and finally wash my hands.

The procedure was an everyday routine for Oshima, the kind of executive who wears Oxfords with brightly colored laces and skips a tie. Several employees were getting to work around the same time and followed the same steps. We filed through a set of swinging doors and into one of the grow rooms.

Pictures of vertical farms often feature an array of magenta and cobalt-blue LED lights more reminiscent of a nightclub than a farm. These are for demonstration only: In reality, the beds are lit with LED light that appears bright white to the human eye, but in fact emits the pink and blue wavelengths that fuel microgreen growth. A few of the beds were unlit. The lights aren’t on all the time, Oshima explained. The grow room stays at an ambient 70 degrees. Huge fans whir in the background; nevertheless, the room smells like an aquarium and the air is similarly humid and dank.

The crops are planted in beds about 80 feet long and 5 feet wide. Farmers — who wear starched white lab coats — germinate the seeds in a reusable fabric. The seeds nestle into the off-white fleecy fiber that strikes a balance between breathability and structural integrity.

In newly-seeded beds, the sprouts perk up every half inch or so, stimulated by the intense light. When the greens are ready for harvest, the surface of the bed resembles a sea of green leaves. The plants’ roots dangle into a basin below, treated with a nutrient-dense mist and oxygen delivered through aeroponic technology. The mechanism that releases AeroFarms’ signature mist is hidden from view inside a black plastic tub called the solutions chamber.

The beds stack on top of one another into towers 12 stories or 36 feet into the air. Each vertical unit has its own computer that monitors all aspects of the plants’ growth. A control-panel box houses the wires, cables, and connections that feed into a touch screen displaying data for every inch of every bed.

Accordion platforms lift employees inspecting greens up into the air, where they perform maintenance tasks in response to computer-generated warning signs. This allows for directed and efficient crop management; human observation complements the digital monitoring. A machine harvests and packages the greens once they’ve reached baby maturity.

Infrastructure and Investment

Four external factors have driven investors’ interest in such plant factories: climate change, insecurity in the labor force, food safety, and increasingly urban populations. AeroFarms and its competitors claim to provide a comprehensive fix.

Given access to ample renewable energy to power the LED lights, the grow system can function with a great deal of independence from the environment. Its computer-controlled grow systems and automated harvesting and packaging chains mean the food supply need not rely on an uncertain workforce. The food safety measures that control who and what enters the growing facility reduce the risks of contamination and foodborne illness. AeroFarms — and its competitors — do not use agrichemicals such as pesticides and herbicides. And vertical farms can bring food production to the inner city.

Among indoor farmers, Dr. Despommier is a guiding light — but the vertical farms in operation today have yet to fulfill his vision. The kind of multi-use and agriculturally-diverse buildings he envisions would require significant investment to design and build. Estimates for multistory buildings hover in the hundreds of millions; retrofitting existing structures is cheaper but still represents a substantial investment.

AeroFarms’ beds may be vertical, but the entire operation sprawls out horizontally. It is, for now, more indoor farm than vertical farm. Its Dream Greens grow in the heart of Newark — a city that still rumbles with the aftershocks of deindustrialization and the environmental threats of industry — but funnel into distribution networks up and down the Eastern Seaboard. It doesn’t quite fit Despommier’s zero food-miles vision.

Leafy greens have become the poster child for efficient urban indoor agriculture. Unlike most other crops, farmers can sell the whole green plant, except for the roots. By contrast, a cherry tomato requires growth of the entire plant (stem, leaves, blossoms) before bearing fruit.

Whether indoor farming will prove viable for a range of crops is a basic, and unanswered, question. Imagine growing wheat, rice, corn, or soy in a system where photosynthesis (via artificial light) is expensive.

Getting Off the Grid

.

Solving the renewable energy problem is at the forefront of development for vertical farmers. AeroFarms uses hydropower and solar energy — it even has a farm in Saudi Arabia that pulls water out of the air through reverse-osmosis technology. But before cities can become energy-efficient urban jungles, engineers have to produce the means to get off the grid.

A rendering of what vertical farming might look like on Mars. Photo credit: NASA / Wikimedia

The drive to render indoor farming entirely independent of its environment has pushed the concepts behind vertical farming to the stratosphere — literally. Freight Farms, a company that upcycles shipping containers into portable vertical farms, just announced a partnership with Clemson University to explore deep-space applications of its technology. The collaboration is made possible through a NASA grant to explore a “Closed-Loop Living System for Deep-Space ECLSS with Immediate Applications for a Sustainable Planet.”

While container farms reach for outer space, cities will continue to urbanize at unprecedented rates. The droughts, floods and climate inconveniences that have already begun to exert pressure on commercial and family farmers alike will intensify.

Meanwhile, most of the the farmers raising food for people are small, conventional operations that struggle with minimal public support in a low-margin, high-risk business. Research and development funding for the majority of American farmers growing fresh fruits and vegetables is virtually nonexistent — families or individuals own almost 83% of the farms growing vegetables in the US.

The 2014 Farm Bill inaugurated microloan and grant programs for small and beginning farmers: whether funding for these programs will continue is up for debate as Congress considers the 2018 Farm Bill. Sonny Perdue, the current Secretary of Agriculture, is an agribusiness veteran.

Vertical farmers see themselves sidestepping both the vice-like grip of Big Ag and the insecurity of small-scale farming. They bring fresh, unprocessed foods to the hearts of cities independent of the industry lobby or the inconsistencies of farmers’ markets. Production is controlled and abundant enough to tap into existing supply chains. By distributing to supermarkets and online delivery platforms, they eliminate the distribution challenges many small farmers face. And, at least for the present, they receive ample funding from venture capital and private equity, untethered by the limits of public support.

Given the looming threat from climate change and ever increasing urban populations, it’s clear that both the current farm-to-table system and Big Ag fall short. Yet the new money from venture capitalists brings its own constraints. In fact, Despommier’s condemnation of agribusiness may best describe the conflict: behind their presentation as mission-driven companies passionate about making good food widely available, they are in it to make money.

There is little precedent for how the model will behave as companies scale up and diversify. Public investment in research and development could provide some answers. Calls to action range from implementing new urban agriculture and technology programs at universities to reworking city tax structures to support the new urban farmers through subsidies and tax credits. The growing urban and climate-insecure populations that vertical farmers hope to feed will need more than the production of leafy greens. But for now, the logic among vertical farmers amounts to a hale and hearty Let them eat kale.

Related front page panorama photo credit: Adapted by WhoWhatWhy from building (Cjacobs627 / Flickr – CC BY-SA 3.0) and VertiCrop System (Valcenteu / Wikimedia – CC BY-SA 3.0).

This Vertical Farming Startup Is Valued At $27.5 Million

This Vertical Farming Startup Is Valued At $27.5 Million

By Daniel Lipson 2017

What's vertical farming? In Bowery Farming's first indoor farm, located in a warehouse in New Jersey, proprietary computer software, LEDs, and robotics are able to grow leafy greens without any pesticides, using 95% less water than traditional farms. CEO Irving Fain describes his company as a tech company "thinking about the future of food."

Their indoor farms can be located near city centers and will be able to cut transportation costs and help curb the environmental impact of the industry. By being located indoors, they're unbeholden by weather and can produce 100 times more greens than a traditional outdoor farm of the same size. Fain sees it as a way to answer global population growth, shrinking farmlands, and an influx of people towards urban areas. The farms are enabled by recent technological advances in data analytics and lighting and are poised to scale up in the coming years.

YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP/Getty Images

Fain started his career as an investment banker at Citigroup, ran marketing at iHeartMedia, and co-founded loyalty marketing software firm CrowdTwist before venturing into food. They raised first round funds of over $20 million from a list of investors that includes Blue Apron CEO Matt Salzberg and celebrity chef Tom Colicchio as well as GV (formerly Google Ventures). The company has experimented with over 100 different crops and sells six varieties of leafy greens to Whole Foods and Foragers. They plan to use the extra cash to hire more workers and move towards other types of produce. For the long term, they are eyeing China and other emerging markets where food security is an important topic.

Bowery isn't the only one trying to do vertical farming. Competitors AeroFarms and Plenty United are also farming indoors with the capacity to produce millions of greens, and AeroFarms has already raised $100 million, while Plenty United has billionaire backing from Jeff Bezos and Eric Schmidt. The technology enables vertical farmers to convert old warehouses and factories into agricultural centers. All of them benefit from advances in LED lighting that can mimic natural sunlight, as well as lower costs for industrial-scale lighting setups

A Young Startup Looking To Change Sustainable Food Production At The Hyper Local Level

August 21, 2017

A Young Startup Looking To Change Sustainable Food Production At The Hyper Local Level

Without a doubt, one of the most pressing issues in the modern world is that of feeding a rapidly expanding global population. Estimates from a UN DESA report in 2015 indicate that the estimated global population by 2050 will rise to over 9.7 billion people, and that over 66% of those people will be living in urban centers. With such staggeringly high numbers of people in urban areas, providing a food production solution that can rise to the challenge of feeding billions every day (while keeping a low enough carbon & land area footprint) and be environmentally and economically viable is one of the most important problems we must solve to prepare for this inevitable future.

Aeroasis, a young & growing AgTech startup based in South Florida hopes to tackle this problem using a hyper local, decentralized approach. Using innovative hydroponic & aeroponic technologies, combined with the most efficient renewable energy harvesting systems available today, Aeroasis aims to impact the food production/distribution industry in preparation for a more crowded world.

Aeroasis has a deep focus on educational work, providing schools & school districts with the resources to start and maintain their own indoor farms, and giving students a thorough understanding of the problems surrounding food production and distribution today. As the next generation of global citizens grows up, these technologies will continue to get exponentially more cost effective, and the young adults that are properly educated will be prepared to enter a world where they can consciously choose to consume and endorse hydroponically grown produce. Beyond just consumption, the use of automation technologies and deep analytics through sensor feedback will allow consumers and urban dwellers to go beyond just consumption, growing much of their produce in-home.

Aeroasis has been developing Oasis Mini, an automated micro Smart Garden, for the last two years in an effort to prove the viability of this concept. Oasis Mini is a 3 chamber automated Smart Gardening system that takes up less space than a fridge, but can produce up to 26 harvests a year in the case of leafy greens like lettuce and cilantro. Small systems like this are great for any urban householder with a green thumb but no space for a garden, and even for consumers with no gardening experience or free time looking to grow a small garden without all the work and mess. Oasis Mini is small, but its ability to grow food at the highest quality using 90% less water, 60% less nutrients, and no pesticides ever is a powerful showcase of the potential for these technologies to be scaled up in the very near future. Removing the concept ofseasonal crops also makes food availability universal, and allows the individual consumer to make conscious and unlimited choices about their nutrition. There is a long list of benefits to growing hyper local, but here are just a few big ones:

- No transportation and packaging means up to 80% less food waste. In the US alone, billions of tons of food are wasted every year, and the majority of that waste happens at the harvest, processing, packaging, and retail levels. Making hyper local systems ensures minimal processing and transportation, significantly reducing waste.

- Using indoor controlled systems means pests are much less of an issue. Pesticide use has been linked to several forms of disease in humans, and eliminating the need for potentially dangerous chemical inputs in the growth process increases the quality and safety of the end product.

- Having communities observe and be a part of the growth process of their food increases awareness and respect for the food grown and results in less consumer side waste. Having community scale Smart Farms incentivizes community outreach and integration and increases the sense of shared responsibility in local groups. This can have an incredibly positive effect on people’s ability to connect and interact peacefully.

- Any excess in harvests can either be given to those in need, or can be sold at a market premium due to its freshness and high quality.

Aeroasis is working hard at building this vision. Their team sees a time in the very near future when either all homes, or at least all communities, will come equipped with a larger scale Smart Farm system that allows them to grow much or all of their produce in-home or at a community center style farming co-op. The core mission at Aeroasis is to facilitate/develop projects like this in an effort to help feed the world while reducing the enormous footprint agriculture leaves on the planet. Aeroasis also does consulting and design work related to projects in community centers, retail spaces, and even individual homes. They provide a range of services from design, fabrication, installation, and maintenance of Smart Gardening systems to doing public speaking and awareness work at conferences, workshops, and other sustainability events.

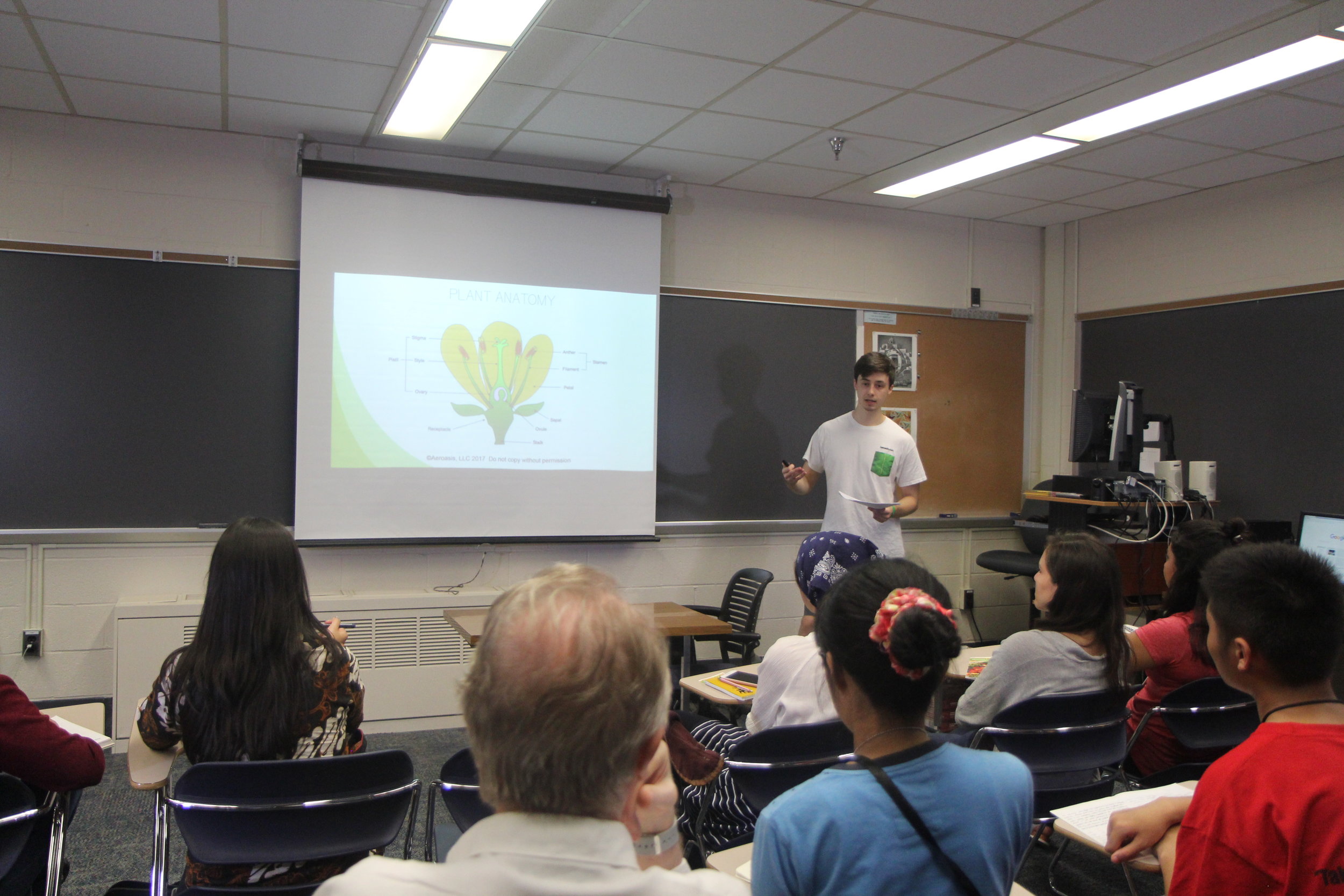

The Aeroasis CEO, Thomas Wollenberger, just taught a 2 week workshop on sustainable food production in partnership with UNESCO affiliated clubs in the Washington DC area, and is working with several schools and school districts in Florida to bring hydroponics to classrooms. Aeroasis continues to develop initiatives and workshops around the world with strategic partners.

For more information on Aeroasis, what they do, who they are, and how to contact them, you can visit www.aeroasis.com.

Indoor Farms of America Receives Investment From Major U.S. Ag Firm Co-Alliance

Indoor Farms of America Receives Investment From Major U.S. Ag Firm Co-Alliance

21-08-2017

LAS VEGAS, Aug. 21, 2017 : Indoor Farms of America, LLC is pleased to announce that it has completed the final phase of its initial relationship with Co-Alliance, LLP, one of the nation's oldest, largest and most diverse traditional agriculture companies. This final phase comes in the form of an equity investment in Indoor Farms of America. Terms of the transaction are private.

"When we had our first visit from the folks at Co-Alliance late last year, we expressed our commitment to having traditional agriculture in the U.S. embrace this technology in a manner that would benefit them, and we discussed in detail just how that would take shape," explained David Martin, CEO of Indoor Farms of America.

"Becoming a part owner of Indoor Farms of America represents our belief in its products and people," said Co-Alliance CEO, Kevin Still. "We see the potential of integrating this world class indoor agriculture equipment into traditional farming operations as a way to diversify family farms, add a year-round income stream, and bring the next generation back to the farm."

The new investment comes just weeks after Co-Alliance purchased two "warehouse" style farms, marking an important milestone for the CEA company. "We have achieved the first stage of the plans to have indoor farming adopted by the very folks who have kept us fed in this country since its inception, and that is the traditional farmer," said Martin.

Co-Alliance will pilot these indoor farms with traditional farmers, assessing the capability to diversify income, spread risks, and to supply local fresh produce all year round. Said John Graham, CFO of Co-Alliance, "We are evaluating the commercial application and income generating potential of the farms here in Indiana so when we introduce the technology to our member-growers on a larger scale, we have a turnkey, replicable, scalable complete production process in place."

"When Dave and I developed the equipment, we embarked on a journey that started 4 years ago and continues with an intense focus on Research and Development. This is an affirmation of the purpose of the journey. Our aeroponic farms have proven reliable in 3 years of test growing of over 30 types of greens, strawberries, cherry tomatoes, peppers, beans and edible flowers. The equipment will produce strong economic results that make it more than viable in the indoor growing environment, more so than any other equipment that exists today, due to far higher yields in a given space," said Ron Evans, President of Indoor Farms of America.

Co-Alliance sees new opportunities for farmers to have a major impact on the "locally grown" food movement. Per Kevin Still, Co-Alliance CEO, "Co-Alliance is positioning itself and its farmer owners to be able to capitalize on the growing consumer demands for truly fresh, locally grown, and high-quality products available to them from local farmers they know and trust, year round. And to do so, we believe investing in Indoor Farms of America is the right way to go about it."

Co-Alliance, LLP, is a partnership of cooperatives with community roots established in the 1920s. Headquartered in Avon, Indiana, its 50 locations across Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio serve the areas of Energy, Agronomy, Grain Marketing, and Swine and Animal Nutrition. For more information, visit www.co-alliance.com.

Indoor Farms of America, LLC, is leading indoor ag innovation. It has farms installed in countries surrounding the globe, and brings meaningful advancement to indoor agriculture, with a sole purpose to make it economically viable, while creating meaningful jobs for people in any region, including veterans and disabled individuals.

Indoor Farms of America is dedicated to creating a sustainable food supply for generations to come. The company designs and builds its patented advanced indoor agriculture equipment using a proven, reliable aeroponics method as the foundation of the farm, allowing year-round high yield production, with no sky-lifts or ladders required to operate the farm.

Delta Greenhouse Expansion On Hold Thanks To Labor Shortage

Delta Greenhouse Expansion On Hold Thanks To Labor Shortage

ByTyrel Linkhorn | BLADE BUSINESS WRITER

Published on Aug. 17, 2017 | Updated Aug. 18, 2017 6:19 p. m.

NatureFresh Farms has announced that a planned expansion of its greenhouse in Delta, Ohio, has been put on hold.

The owner of NatureFresh Farms said Thursday that a planned expansion of its large commercial greenhouse in Delta, Ohio, is on hold because of the company’s difficulties in finding and keeping employees.

The Ontario-based company came to northwest Ohio in 2015, with plans to build a sprawling, 175-acre greenhouse over the next seven years at a cost of up to $200 million. So far, the firm has spent about $65 million to get the operation up and running and build out 45 acres of growing space under a roof.

And business has been good. Peter Quiring, NatureFresh’s founder and chief executive officer, said he has the customers to support doubling that acreage.

RELATED: Ontario-based grower plans 175-acre greenhouse in Delta

But he’s holding back on an expansion because of the company’s ongoing struggle with finding workers.

“Labor’s the caveat,” Mr. Quiring said in an interview. “It’s not happening unless we figure out the labor situation. It can’t happen. My bank wouldn't even let me do it, not that I would.”

Mr. Quiring was in town Thursday for the Northwest Ohio Ag-Business Breakfast Forum near Bowling Green hosted by the Center for Innovative Food Technology. NatureFresh was this month’s presenter.

Between its greenhouse and a distribution center in Maumee, the company has about 220 full-time employees in northwest Ohio. NatureFresh grows about 10 varieties of tomatoes in Delta, which are shipped primarily to customers across the Midwest and the eastern seaboard.

A 45-acre expansion would require another 90 to 100 full-time, year-round employees.

“The sad reality is Canadians and Americans do not want to do agricultural work. That is just the reality. If they do agricultural work, they want his job,” Mr. Quiring said, gesturing to his chief grower, “or my job, or at the very least they want to be in shipping and receiving. They do not want to pick tomatoes.”

Officials said wages start at more than $12 an hour and can rise to more than $18 an hour for quality employees.

One important source of labor are guest workers from outside the United States. The company currently has 43 employees from Honduras and Guatemala who are here on visas.

The United States does allow companies to bring in foreign workers for agricultural work, but only on a seasonal basis. And while there’s no cap on the total number, workers must go through the application process every year and can’t change employers without a new petition.

Exterior of NatureFresh Farms' greenhouse facility in Delta, Ohio. A planned expansion of its the facility is on hold because of the company’s difficulties in finding and keeping employees.

THE BLADE/JEREMY WADSWORTH

Enlarge | Buy This Image

Mr. Quiring said Canada’s guest worker program is more manageable for operations like his that can grow produce year-round.

“What we need is a better system of getting labor,” Mr. Quiring said. “We need the American program to be year-round. We need to open that up. We need to bring people here legally.”

In a phone interview, Baldemar Velasquez, president of the Toledo-based Farm Labor Organizing Committee, said that, while there have been a number of well-documented problems and abuses within the farm labor visa program, there are legitimate reasons for keeping it.

One of the chief ones, he said, is the fact that many of those workers don’t want to immigrate full-time to the United States, and the ones who do likely wouldn’t want to keep working in what are largely seasonal jobs.

And Mr. Quiring made those same arguments at the forum.

“Number 1 they’re probably not going to stay with agriculture very long. But Number 2, you’re doing a brain drain from that country again,” he said. “That may help our country, but it certainly doesn’t help theirs. When they go back home they educate their children. They’ve got a chance of taking that country out of the third world status that they’re in and making something of it.”

U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D., Toledo), who was among the crowd at Thursday’s forum, urged during a question-and-answer session that that those in the agricultural industry push for changes that can improve the country’s visa program for employers and workers.

“We have a unique opportunity with the renegotiation of NAFTA, and I just want to get it in your consciousness and the consciousness of every agricultural person here,” she said.

“This is really important,” she continued. “We’ve got 16 members in the House. We’ve got two senators from Ohio, so that’s 18 voices. If Ohio agriculture could be focused on this, I think we could really make a difference.”

Mr. Velasquez said changes to the visa program would need to come from a place where both labor and business are at the table.

“There’s some things you could do, but to make it politically feasible you have to have all segments of the labor market involved,” he said. “If you have the unions involved and you have the employers involved, it makes it much easier politically to make those changes.”

Even so, Mr. Velasquez disputes the notion that Americans won’t work those jobs at all, saying what they won’t do is work for low wages.

“I can understand how NatureFresh, being under the roof and year-round would want year-round workers, but frankly there are enough domestic workers to do something like that,” he said. “That’s a more controlled climate that would attract local workers or domestic workers if they paid a wage that was high enough.”

Mr. Quiring painted a somewhat bleak picture of their efforts to staff the greenhouse.

“We’ve interviewed around 600 people in the last two years. Of that 600 people, about 30 to 40 percent didn’t pass a drug test. And we don’t care about marijuana, by the way. This is heavy drugs we’re talking about,” he said. “It’s a sad fact.”

NatureFresh hired close to 300 from that pool. Some never showed up, about 40 were dismissed, and another 90 quit — many within their first few days.

“I go to a lot of trade shows,” Mr. Quiring said. “The Number 1 topic of conversation for the last five to 10 years has been labor. Now it’s the only topic of conversation. There is nothing else to talk about anymore.”

Contact Tyrel Linkhorn at tlinkhorn@theblade.com, 419-724-6134 or on Twitter @BladeAutoWriter

Indoor Grow Gardens Bring Your Gardening Inside

Indoor Grow Gardens Bring Your Gardening Inside

By Kim Cook | AP August 8, 2017 | Home & Garden

A tasty salad of tender pea shoots. Handfuls of fragrant herbs for the stew. Snack veggies for lunch boxes.

Keeping a fresh supply of greens and herbs on hand can be challenging as the growing season winds down, or if you don’t have a garden. But now you can plop a planter anywhere in your house, set a few timers, and in about 10 days you’ll be nibbling greens like a contented rabbit. All year round.

There are a variety of indoor grow gardens on the market that come with everything you need: planter, planting medium, seeds, fertilizer and a high-intensity grow light. Smart tech and remote controls adjust lighting and moisture levels, so even if your thumb’s not the greenest, you can still find success.

Linnea and Tarren Wolfe of Vancouver, British Columbia, decided to design a home grower after watching their kids gobble up sunflower and pea-shoot microgreens “like potato chips.”

Their Urban Cultivator looks like a wine fridge. It comes as a free-standing unit, topped with a butcher block, or it can be installed under the counter and hooked up like a dishwasher. The company offers an extensive seed selection, but anything from your local garden center will grow. (www.urbancultivator.net )

Linnea Wolfe advises home gardeners to do some research into the benefits of the edible, immature greens known as microgreens.

“Most of them only take about 7 to 10 days to grow,” she says. “You can mass-consume them, and the health benefits are extraordinary.”

The indoor garden trend is part of a, well, growing movement, says New York landscape architect Janice Parker.

“The technology of these kits simplifies hydroponic gardening at its best, and makes it available to all,” she says. You don’t need a yard, or favorable weather.

“What a pleasure to have fresh herbs, flowers and vegetables, and experience a connection to nature no matter where you are,” says Parker.

She thinks these kits shouldn’t just be relegated to the kitchen.

“I’d put them anywhere — dining room tables and coffee tables come to mind. Or in ‘dead’ spaces that have no light or interest,” she says.

She recommends growing plants with both flavor and flair: “Chives, dill, rosemary, fennel, basil and nasturtiums all have gorgeous flowers and beautiful foliage”.

Miracle Gro’s line of Aerogarden indoor planters includes the Sprout, which is about the size of a coffee maker and suitable for herbs, as well as a larger model in which you could grow just about anything. Pre-packaged seed pods like lettuces, cherry tomatoes, herb blends and petunias come ready to pop in the planter. An LCD control panel helps adjust lighting and watering needs. (www.miraclegro.com )

He’s Spent Most of His Life Perfecting Lettuce

He’s Spent Most of His Life Perfecting Lettuce

Pieter Slaman in the greenhouse at Little Leaf Farms. | JONATHAN WIGGS/GLOBE STAFF

By Cindy Atoji Keene GLOBE CORRESPONDENT AUGUST 17, 2017

Why should a greenhouse worker be granted an 0-1 Visa? The document is granted by the US government only to noncitizens who demonstrate “extraordinary ability or achievement.” For Dutchman Pieter Slaman, it’s because he had proprietary knowledge of commercial horticulture that was needed for a new high-tech lettuce farm in Devens. Slaman is a fourth-generation grower from the Netherlands, where over a century of experimentation has made the Dutch experts in sustainable-agriculture practices. He hails from near the Hague, where an industry cluster of greenhouses gave the area the nickname “Glass City.” Slaman, 50, grew up “between the tomatoes,” starting his first greenhouse when he was just 17 years old. Now he uses his “green fingers” to grow 4 million plants in a 3-acre greenhouse at Little Leaf Farms, an agribusiness that produces arugula and other greens on a relatively small footprint. While the majority of lettuce is shipped in from the West Coast, Little Leaf Farms produce goes from harvest to supermarket shelf within a day of harvest. The Globe spoke with Slaman about how he’s making a life out of lettuce.

“Both of my grandparents and many other relatives had a greenhouse in the Netherlands, so it’s in my blood. One grew lettuce, and the others, flowers and bulb plants. Dutch farmers have been growing indoors for years, using sunlight and rainwater to compensate for our agriculturally challenged geography.

“I heard stories from my dad about the World War II resistance and how my family hid escaping Jews under the greenhouse floor. The region was the biggest horticultural producer in the world, providing the whole of Europe with vegetables. But times have changed, and I wanted to travel the world to see if I could grow things elsewhere.

“Little Leaf contacted me and said they needed a Dutch grower. They had a greenhouse they were building in New England and wanted to do it ‘right’ — no pesticides, collecting rainwater for irrigation, LED lights.

“When I first arrived in Boston, it was the second week of February, minus 20 degrees Celsius, and very cold and snowy. The first couple of months, I’m thinking in Dutch and talking in English. There were many cultural differences. I had to adjust to working with a Mexican crew instead of a Polish one. I missed having a neighborhood of other growers around me.

“And I quickly learned that if something broke, I couldn’t just jump into the car and go to the nearest greenhouse supplier, especially with metric parts. I had to order and wait, and this could be a problem because a crop can die within six hours without water.

“But we were able to set up a highly advanced, automated hydroponic system. Even with that, it’s not easy to grow lettuce in New England’s erratic weather. But in the end, growing is nothing more than taking the stress away from the crop.

“An expert’s eye, the many years of experience, and a grower’s passion make the difference and can never be taken over by a computer and data. I can just step into the greenhouse and instinctively know whether the humidity or temperature is too high or low. I spend many hours a week, just walking, scouting, and turning over leaves to see what kind of bugs I can find. This is something I’ve been doing my whole life.

“After all, everything around us has a connection. That’s why I pray in the greenhouse and do yoga in my free time. It’s all about time and balance. And that’s true for plants — and for humans.”

Cindy Atoji Keene can be reached at cindy@cindyatoji.com.

Editorial: Research at UMass With Global Reach

Editorial: Research at UMass With Global Reach

Evan Chakrin, a University of Massachusetts Amherst junior studying horticulture, harvests butterhead bibb lettuce from a hydroponic raft bed Aug. 4 at the UMass Hydrofarm he co-founded with Dana Lucas, a senior majoring in sustainable food and farming. GAZETTE FILE PHOTO

August 17, 2017

Two students at the University of Massachusetts Amherst have turned a modest grant and an old greenhouse into the first hydroponic farm on campus to show off sustainable agriculture techniques.

An award-winning geoscientist at UMass will use a $94,375 grant from the Massachusetts Environmental Trust to gather and study water samples with the goal of better understanding the impact of droughts.

Those are examples of research that spills outside the university’s classrooms to address real-world issues such as local food production and climate change.

Evan Chakrin and Dana Lucas are co-leaders of the student-run hydrofarm in a small greenhouse next to Clark Hall in the central residential area of campus. Started last winter, the farm grows food without using soil. Nutrients are dissolved into the water surrounding the plants’ roots, and the system uses less water than an irrigated field. It also keeps nutrients from running off fields to other water sources.

“It’s basically just using chemistry to grow plants,” says Chakrin, a junior studying horticulture. “We can totally control whatever we waste.”

One Friday this month, he harvested 10 pounds of lettuce that he planned to donate to the Amherst Survival Center. Also during its first year, the hydrofarm has supplied food to on-campus restaurants, including the vegetarian Earthfoods Cafe. Other crops include kale, tomatoes and strawberries.

Lucas is a senior majoring in sustainable food and farming. Since it was elevated in 2013 from a concentration to a full-fledged major within the Stockbridge School of Agriculture, enrollment in the major has increased from 50 to 140 full-time students.

She started cultivating the idea for a hydroponic farm on campus in 2015, and with Chakrin received a $5,000 grant and use of the greenhouse from the Stockbridge School in December. They started germinating seeds and later in the winter began selling food they harvested. The revenue is used to buy more seeds and equipment.

In the fall, the pair will teach a course for 12 undergraduate students who want practical experience. “The techniques we use here are are the main hydroponic techniques used,” says Chakrin. “This work is directly applicable to any of their food production goals.”

He hopes to attract students interested in urban food production, even if they are not enrolled in the Stockbridge School. One of the benefits of hydroponics is that it can used almost anywhere to grow food locally.

Chakrin and Lucas also have a consulting service, which they call Farmable, to coach people who want to farm in urban areas. “Anywhere is farmable and this concept will revolutionize how urbanites are able to access food,” Lucas says.

Water is also an important ingredient in the research by hydrogeologist David Boutt, an associate professor in the Department of Geosciences. His grant — funded by the sale of the state’s environmentally themed license plates — will help develop an isotope mapping tool to study the composition of water samples and learn more about the effects of droughts. A public database will help water managers assess the sustainability of freshwater resources.

Boutt says, “By measuring the isotopic composition, we can start to describe the source of that moisture — did it come ultimately from the Arctic? Or the Gulf of Mexico?”

The data is important not just to better assess how droughts may affect an area, but also in relation to global warming. “As the Arctic is warming, more and more of that moisture is moving to New England,” Boutt says. “With this database we can start to track this and understand how the hydrological cycle is changing the source of moisture to the region.”

Boutt is seeking water samples from wells and streams in the region. Anyone interested may call him at 413-545-2724 or email dboutt@geo.umass.edu.

He will have an international forum to discuss his research next year after being named the Birdsall-Dreiss Distinguished Lecturer for 2018 by the hydrogeology division of the Geological Society of America. His topics will include groundwater and climate change, the role of groundwater flow in hydrologic processes and how water and lithium factor in the global transition from fossil fuels to green energy.

Chakrin, Lucas and Boutt put a face on the many people studying and teaching at the university who are determined to make a difference by applying what they learn locally to global problems.

Year-Round Agriculture in Milwaukee? Look No Further Than Big City Greens

Year-Round Agriculture in Milwaukee? Look No Further Than Big City Greens

Photo by Jessi Paetzke

ANN CHRISTENSON AUGUST 15, 2017

An indoor farm north of Brady Street is a model of year-round city agriculture.

After eight years selling eggs, pickles and produce out of their farmhouse in California’s Napa Valley, Bryan De Stefanis and Deborah Diaz moved back to Wisconsin with their daughter in 2015 to be close to family and to launch a farming business in, yep, the city of Milwaukee.

De Stefanis found a location for a greenhouse a few blocks north of Brady Street, close enough to the city’s farm-supporting restaurants so he could deliver within hours. One of his earliest visits was to Sanford Restaurant, where chef/co-owner Justin Aprahamian’s culinary philosophy embraces locally grown food and uses the kitchen as a lab for preserving and fermenting all manner of ingredients. Soon after making the Sanford connection, De Stefanis’ Big City Greens (906 E. Hamilton St.) supplied 20 flats of micro-arugula for Aprahamian’s 2015 gig cooking at the James Beard Foundation Awards.

In addition to heirloom vegetables, herbs and microgreens from the indoor farm, De Stefanis delivers foraged wild edibles he unearths at their property in central Wisconsin. It’s “all very fresh and great quality,” says Buckley’s restaurant chef Thi Cao, a regular customer. Big City’s ingredients and preserved foods, including those featured below, are also available at the weekly farmers markets in Shorewood and Greenfield or by emailing Big City Greens.

Deborah Diaz and Bryan De Stefanis of Big City Greens. Photo by Jessi Paetzke

Beyond the Megafarms: 4 Alternative Models For Indoor Agriculture

Beyond the Megafarms: 4 Alternative Models For Indoor Agriculture

Indoor agriculture has grabbed several headlines in the mainstream media recently. Not only does the idea of growing produce indoors, in an automated high-tech environment capture the imagination of many consumers and readers, but just last month, an indoor farming business raised a whopping $200 million in funding, in the largest ever deal for an agriculture technology startup.

South San Francisco’s Plenty raised the funding from SoftBank along with affiliates of Louis M. Bacon, the founder of Moore Capital Management, who joined the round alongside existing investors Innovation Endeavors, Bezos Expeditions, Chinese VC DCM, Data Collective, and Finistere Ventures.

Good news sells

Four different indoor farming operations told AgFunderNews that the rate of incoming investment inquiries noticeably increased after the Plenty news. High-tech indoor farming has captured the imagination of the media as well. In fact, you could say that indoor farming is the crossover hit of the agtech world — a niche story that has made it into the mainstream.

But like a country song that hits the pop charts for a while, high-tech, high-cost indoor vertical farming groups like Plenty are not necessarily representative of the form all indoor farming operations take. There are many different business models for growing food indoors, and as this segment of the agrifood industry is still very young, there are few proven successes yet.

Further, as Sanjeev Krishnan of S2G Ventures, an agtech-focused VC, told AgFunderNews in July, it is unlikely that this space will see a clear front-runner emerge.

“There is no winner takes all potential here. There are many different models that could work and we are excited about the platforms being built in the market.”

Plenty has a similar business model to a few other well funded startups including AeroFarms of New Jersey, which closed $34 million of a $40 million Series D round in May, and Bowery Farming, which raised a $20 million Series A co-led by General Catalyst and GGV Capital, including GV (Google Ventures) in June.

All of these farming operations are indoors, using LED lights and varying levels of data science to create what is essentially a plant factory — or mega farm. They don’t use soil or sunlight, they seek to make a profit selling produce for retail and food service, and they rely on scale, explaining their need to raise vast sums of capital.

“The thing that is hard about investing is that at some point someone has to invest in scale before the scale is there and SoftBank is both visionary and courageous,” said Plenty CEO Matt Barnard to AgFunderNews when the news broke in July.

Some say that the high price tag of building indoor vertical megafarms makes profitability a distant dream — AeroFarms’ flagship facility in Newark will cost about $40 million when fully complete.

Virtue in variety

Below we explore some business models that differ from these mega-farms and are lower-cost. They are of course faced with a healthy dose of skepticism too; some industry insiders say that lower-cost, smaller-scale operations are not financially sustainable long term due to the high cost of labor and lack of efficiency.

What the alternatives have in common generally, however, is that they collect their revenue at different points in the value chain and, often, they have more than one income stream.

Read below how four indoor ag startups are taking a different approach to the indoor farming trend.

Green Collar Foods

Based in Detroit, MI, Green Collar Foods (GCF) builds and operates small, indoor hydroponic farms that are run by community members. It sells leafy greens exclusively to local public sector institutions like hospitals, at market prices, with multi-year forward contracts. The company is built to operate in areas with a high degree of urban blight and eventually transfer each farm to a local owner, moving toward a franchise model. GCF plans to construct 6,000 square foot facilities, which will cost under $500k each.

The company has farms in Detroit and Bridgeport, CT, and soon will have one in Rotherham, UK, all in cooperation with local universities.

The company says that its aeroponic growing systems and farm management software are simple enough to hire unskilled labor and therefore make a larger impact at the community level through job creation. “The GCF Platform — a hybrid between best-in-class aeroponics and cloud-based computing — is designed to be an effective and simple solution right out of the box,” said co-founder Daniel Casanas.

Founder Ronald Reynolds sees his distributed — or franchised — model of urban farming as lower risk to a large megafarm because of the disease and pest risk associated with concentrated growing at scale.

“If you have 10-, 6-, 7,000 sq ft, you still add up to 60,000 sq ft. You can still leverage the same forward contract, but if you run into hiccups in the facilities you can switch over,” Reynolds told AgFunderNews.

Reynolds said that the high-profile megafarms are in a chicken and egg cycle, with investor money following this one business model and then entrepreneurs recreating it because that’s where the money is. “The business models are trying to follow where the perceived money is coming from. The only thing that seems to be getting people’s attention are big asks. People find it easier to write bigger checks than smaller checks.” GCF is currently working to complete a $1.5 million financing round. GCF’s funding to date has come from the co-founders’ own micro-venture firm called DayRiver, local individuals and grants. Read more about Green Collar Foods here.

Alesca Life

Alesca Life charges hotels, high-end catering outfits or hospitality groups for the installation and operation of a small indoor farm and then sells the produce in a subscription model. It is based in Beijing and is currently expanding to the United Arab Emirates.

Founder Stuart Oda has recently been setting up and operating small farms for two members of the Dubai ruling family and Mercedes Benz. In order to increase his footprint, he is embracing the expat population in Dubai, targeting hotels and luxury food service operations where customers are willing to pay a premium and there is more appetite for his crop, leafy greens.

Oda says that his facilities can break even in around two years. “If we have a servicing contract in place for even a year and a half, we will have made back our money.”

He further said that picking the right crops and markets is what makes his financials make sense, “Let’s find a product, or a niche, or a market, or a city, or a customer that can generate the profit we need.” In contrast to the normal practice of American indoor mega-farms, to build the farm and then find the customer, Oda is bringing the farm directly to a specific customer. With Plenty likely to build a farm in Japan and AeroFarms recently receiving an investment from the UAE’s Meraas, the investment arm of Dubai’s leader Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid, other players may be looking to capitalize on favorable pricing for produce internationally as well.

Alesca Life has raised undisclosed seed and angel rounds from individuals and family offices so far. Read more about Alesca Life and other indoor operations in the UAE here.

Freight Farms

Boston-based Freight Farms is one of the older players in the indoor, vertical space, having been around since 2011. The company sells retrofitted shipping containers for indoor, vertical growing along with software to help farmers to track and control their operations remotely via cameras and a mobile app.

The container farms sell for about $85,000 in the US and have the growing potential equivalent to eight acres of land. Freight Farms has offices in the US and Europe along with a licensed dealer in the Middle East.

In June, Freight Farms, completed its Series B funding round of $7.3 million, raising the funding from existing investor Boston-based Spark Capital along with new investor Stage 1 Ventures with support from early investors like Launch Capital.

Freight Farms has now raised a total of $12 million and deployed more than 100 farms that use hydroponic technology, LED lighting, and automated watering and fertilizing technology. The startup raised $3.7 million in Series A funding in 2014.

Fresh Box Farms

Sitting in between a few of these models is Fresh Box Farms, a Boston-based indoor operation currently farming out of shipping containers, but soon building a facility the equivalent to 200 of those, admittedly moving on from the container model. CFO David Vosburg says that though containers were a great place to start, in the long run concentrating labor into one big operation makes more sense.

However, Vosburg’s larger farm will have rooms within it to provide more precise temperature control for different plants. “You just can’t grow efficiently in a large warehouse because basil does not like to grow at the same temperature as romaine and different cultivars like wildly different CO2 levels,” he said.

Fresh Box Farms has raised more than $10 million to date from individual investors and family offices.

The indoor vertical farming industry as a whole is far from maturity and perhaps decades away from competing with the Salinas Valley in leafy greens production. As it grows and matures it may prove important to remember that there is more variety in indoor farming businesses than makes the news

Next Gen Urban Farming Is Here to Stay

Next Gen Urban Farming Is Here to Stay

By Dawn Allen - Aug 16, 2017

A combined fence, recycled-tire trellis and clothesline at the Earth Works community garden in Detroit. Photo by Jessica Reeder, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Urban farming seems so 2010. That’s when you couldn’t swing a hydroponically grown tomato vine without hitting someone who was, wanted to be, or talked about urban farmers being the Next Big Thing. However, cities and suburbs are full of people who need to eat, so urban farmers are still busy growing food and a bumper crop of them are innovating new ways to bring nutrition and social justice to their neighbors.

People in Atlanta, GA, are about to gain access to more fresh food thanks to a $50,000 grant from the National Association of Conservation Districts. This money will go towards converting three utility easements into fifteen acres of urban agriculture. The Mayor’s Office of Resilience sees urban farming as a way to bring healthy food within half a mile of 75% of the city’s residents by 2020.

In Buffalo, NY, they’re starting to take the idea of “grow food, not lawns” seriously. Fleet farming, which took off in Orlando, Florida in 2013, is a decentralized urban farming model where homeowners provide all or part of their yard to pedal-powered farmers who maintain a series of gardens throughout a roughly five-mile radius. The food is then sold in farmer’s markets and restaurants in the area. Growing and transporting food this way solves many problems, from the need to mow wasteful lawns, to avoiding fossil fuels, to helping the local economy.

During the California drought, one innovative urban farmer in the Bay Area produced fish and greens using far less water than traditional farms. Ken Armstrong of Ouroboros Farms was inspired by watching a YouTube video about Will Allen, who brought urban farming to Milwaukee, and decided to take up aquaculture. Cycling water through a system of fish tanks and pebble-filled beds of greens provides nutrients for the plants while cleaning water for the fish. On just a third of an acre, Armstrong produces five acres’-worth of lettuces using 2/3 of a gallon of water per head, compared to 12 gallons for traditionally farmed lettuce.

Urban Farmer Starting His Own Revolution, posted by the Oprah Winfrey Network

Since the urban farming trend has been catching on for several years now, people are becoming more hip to the value of having high quality, local food readily available. The next wave of urban farming may be the “agrihood.” Agrihoods are planned communities that include both residential areas and agricultural land. Residents take part in the process and enjoy the fruits of their labor. One such agrihood, in Detroit, concentrates on resilience through sharing resources, sustainability, and forming community connections. Another, a more upscale development in Las Cruces, NM, sits among custom built homes and optimizes for unusual produce and aesthetic land use. Either way, agrihoods are an old way of life that people are rediscovering in new times.

Finally, out of Dallas, TX, comes a story about the big Texan heart. Big Tex Urban Farms, at the site of the Texas State Fair, is less about profit and more about feeding the hungry.The State Fair is the big annual fundraiser for the urban farming venture, but that means that the entire farm has to move during the September fair season. That’s why they designed the mobile planting boxes that also form the heart of their urban farming outreach. Those gardening boxes are distributed to schools and community organizations, along with soil and seeds suitable for the Dallas climate, as a way of letting people try their hand at growing food risk-free. If everything works out, new urban farms hive off of Big Tex. And if they don’t, the boxes can be returned to the state fairgrounds.

As Owen Lynch of Big Tex Urban Farms says, “A food desert is a health desert is a job desert is an infrastructure desert.” Next generation urban farming is taking root, contributing to communities at the grassroots level, where people are learning to take care of themselves – and each other.

The Trump Administration’s False Promise to Rural America

The Administration claims that GMOs should be accepted on scientific grounds. And it says that its motivation for this policy is to provide large benefits to rural economies that grow these crops, and sustainability. This is undoubtedly aimed at currying favor with an important Trump constituency. But on balance, science does not support the value of GMOs for rural society or sustainability in the U.S.—just the opposite. Several recent research studies have added to the mounting record of GMOs contributing to harmful industrial agriculture in the U.S.

The Trump Administration’s False Promise to Rural America

According to a recent article, the Trump Administration intends to increase pressure on Europe and China to accept food containing genetically modified organisms (GMOs). An Administration task force has been set up to advance these goals, despite a history of European resistance and caution in China.

The Administration claims that GMOs should be accepted on scientific grounds. And it says that its motivation for this policy is to provide large benefits to rural economies that grow these crops, and sustainability. This is undoubtedly aimed at currying favor with an important Trump constituency. But on balance, science does not support the value of GMOs for rural society or sustainability in the U.S.—just the opposite. Several recent research studies have added to the mounting record of GMOs contributing to harmful industrial agriculture in the U.S.

So far, GMOs have largely been the handmaiden of corporate seed and pesticide companies. The vast majority of acres are planted to herbicide-resistant and Bt insect-resistant crops like corn, soybeans, and cotton owned by these companies under patents that prevent seed saving by farmers. Engineered crops in the U.S. are used overwhelmingly in the predominant industrial agriculture system, which causes extensive environmental harm. Since the advent of engineered crops, this trend toward industrialization has only increased, with increasing monocultures of one or two crops that are more vulnerable to pests and other problems.

Engineered crops require less labor per acre, reducing the need for workers and jobs on farms. On the other hand, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) found in a major report last year that genetically engineered (GE) crops do not increase productivity or reduce tillage, which has often argued to be a major sustainability benefit of these crops. As pointed out by the NAS, most of the gains in conservation tillage preceded the introduction of herbicide-resistant GMOs.

The trend toward reduced labor and industrialization has not led to wellbeing in rural communities. Studies by sociologists have long found that by many measures, rural areas dominated by industrial agriculture faired poorly compared to areas with more diverse farming systems.

With increasing adoption of newer industrial farming technologies—corresponding to the growth and dominance of GMOs in major commodity crops—net farm profits are now as low as any time since 2000. In the meantime, the cost of growing these crops has risen dramatically over this same time period. In other words, proportionately more farm revenue is going to pay for land, increasingly expensive corporate seed and other industrial inputs, not to farmers. It is hard to see this as a formula for prosperity in farm country, as farmers are squeezed more and more by economically powerful corporate interests.

Less, Not More Sustainable

GMOs have also facilitated the consolidation of the seed industry, through patents and contracts. This has led to bundled seed products like GMO traits and pesticide seed coatings. These increase exposure of the environment, farmers, and residents of rural communities to harmful pesticides, as well as increase costs to farmers.

The unsustainability of industrial agriculture is epitomized by increasingly dysfunctional weed control, aided and abetted by GMO herbicide-resistant crops. The skyrocketing increases in glyphosate herbicide use encouraged by these crops has resulted in an epidemic of weeds no longer controlled by this important herbicide. By now, this is widely known.

But mounting problems caused by industry’s “solution” of new GMO crops resistant to old herbicides like dicamba are just emerging. Harm to neighboring crops, especially non-GMO soybeans, from dicamba drift during and after spraying of the new engineered crops is pitting farmer against farmer. This led Arkansas to ban its use. By late July, reports of harm from dicamba drift topped 700 complaints, greatly exceeding previous years. High rates of crop damage are now reported by other states, with Missouri and Tennessee also restricting use. The result of dicamba harm is likely to be lower productivity for many damaged soybean fields. Actions by states to restrict the use of dicamba should be understood in the context of the desperation of many farmers to control glyphosate-resistant weeds, caused by the use of glyphosate-resistant GMO crops.

It is noteworthy that dicamba damage has occurred after EPA approved new forms of the herbicide intended to reduce its notorious volatilization and drift-damage potential. But as with glyphosate before it, large increases in the use of dicamba and 2,4-D are encouraged by these new GMO crops. And use later in the season when higher temperatures increase volatility at a time when susceptible crops are vulnerable, may overwhelm the reduced volatility of new forms of the herbicide.

Farmers may also have been blindsided due to restrictions on research by academic scientists on the volatilization and drift potential of the new herbicide formulations. Several academic weed scientists commented that they were not allowed to test these properties in a timely way. Alarming restrictions on the traditional roles of academic research, due to patents on GMO crops, were revealed several years ago. The industry and its supporters claimed that voluntary measures to allow research had addressed this problem. The current situation exposes the fallacy of those assurances.

It does not take a cynic to wonder whether Monsanto anticipates that many more soybean farmers will be forced to adopt this new menace simply to avoid harm from herbicide drift. That won’t save fruits and vegetables that are not engineered for herbicide resistance, harming thriving local food production.

And before long, these new crops will fail as have, increasingly, glyphosate-resistant crops. Weeds are already developing resistance to all of these herbicides, and many have resistance to multiple chemicals, making herbicides as a whole increasingly ineffective.

Meanwhile, agro-ecological methods that are not dependant on these herbicides are available for growing corn and soybeans and are practical, highly productive, as well as good for the environment.

Long-term research that demonstrates this also shows that these methods are as or more profitable than industrial farming but use far fewer synthetic chemicals. And, importantly, more profit goes to workers and farmers than to buy inputs like more expensive GMO seed, pesticides, and fertilizer. In other words, more of the profit stays with farmers and farm workers to spend in their own communities.

Insecticides That Harm Bees, Coupled with GMO Crops, Are Not Needed

A similar situation is unfolding with neonicotinoid insecticide seed coatings, which were supposedly safer than earlier insecticides. Years of research shows that “neonics” are harming bees and other helpful farm insects, and many other beneficial organisms. Pesticide and GMO companies have challenged this research by claiming that the evidence of harm from farm fields, rather than labs, is inadequate. This neglects the overall convincing weight of the evidence from many experiments, and also neglects convincing field data on harm of important wild pollinators like bumblebees.

But now, two research papers confirmed that neonics harm honeybees on the farm, including near crops such as corn. This is particularly important because corn is our most widely grown crop, at around 90 million acres.

I recently published, with Center for Food Safety, the most extensive analysis to date of the peer-reviewed science literature on neonic corn seed coating efficacy and alternatives. It documents dramatically increasing use of coated seed in parallel with Monsanto’s engineered gene to control rootworms.

Monopoly control allows corporations to apply the insecticide to corn seed without providing farmers a choice, so that now about 90 percent or more of this seed is coated with neonicotinoid insecticides. This contradicts the common claim that engineered Bt corn has dramatically reduced insecticide use on that crop. While the volume has decreased, the amount of land exposed has gone up dramatically. This allows many more pollinators and other beneficial organisms to be exposed—one of the basic measures of risk. Bt corn has been accompanied by an increase from about 30 percent of the corn cropland exposed to insecticide before the engineered trait to about 90 percent now—not a reduction to 18 percent of acres treated with insecticides due to Bt, as previously claimed.

The new report shows that harmful neonic insecticide seed coatings rarely increase productivity, are an unnecessary cost to farmers, and that alternatives using agro-ecology methods are productive and beneficial for the environment. This puts to rest the self-serving claims of the industry that these seed coatings are needed to protect corn productivity.