Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Autogrow Announces Its Support Of A Global Indoor Agriculture Hub In Kennett Township, Pennsylvania

Autogrow Announces Its Support Of A Global Indoor Agriculture Hub In Kennett Township, Pennsylvania

AUCKLAND, NZ – Today Autogrow, a major supplier of automated control systems for indoor agriculture facilities, announced its support for a major public-private initiative to develop a global indoor agriculture production, research, training, and service hub on the US East Coast, to be located in Kennett Township, Pennsylvania.

According to Darryn Keiller, CEO of Autogrow, “Kennett is already the center of the US mushroom industry, producing about 1.5M lbs. of fresh product every day, all grown indoors and delivered within 48 hours of picking to markets across North America via Kennett’s extensive ‘cold-chain’ infrastructure of refrigerated packing, storage, and shipping facilities. Over the coming years, that unique infrastructure is likely to attract many new facilities growing other indoor crops, such as leafy greens. This alone makes Kennett a huge potential market for our control systems.”

“But that’s just the beginning of our interest in Kennett’s very innovative initiative,” continued Keiller. “Kennett is also working with a several of the region’s world-class agriculture, engineering and business schools to develop a joint indoor agriculture research, training, and innovation incubator center in Kennett, the first of its kind in a major indoor ag production area. This center will be a major asset to our rapidly evolving industry, and Autogrow very much wants to be a part of its development.”

Michael Guttman, who directs the initiative for Kennett Township, explained that “it is very important to our initiative to attract innovative ag tech companies like Autogrow to help us grow and diversify our regional indoor ag industry. But Autogrow offers a lot more than just its state-of-the-art control systems. Autogrow also has a very forward-thinking strategy that can help us adapt our extensive infrastructure to incorporate emerging trends like the Internet of Things (IOT) and ‘big data,’ which will have a huge impact on how indoor agriculture is done in the future. Working together with Autogrow and our other partners, we hope to develop a blueprint not only for Kennett, but also for a network of similar indoor agriculture hubs around the world.”

About Autogrow

Autogrow (www.autogrow.com) is a leading supplier of climate and automation control systems for indoor agriculture, building systems for everything from single compartment environments through to large-scale, fully-automated greenhouses. In the last few years, Autogrow, based in Auckland, NZ, has been at the forefront of new emerging developments from the US, Canada, UK and Asia in vertical growing, building conversion and shipping container based systems.

About Kennett Township, Pennsylvania

Kennett Township (www.kennett.pa.us) is a municipality in SE Pennsylvania, and historically the center of the 100+ year old US mushroom industry, with grows 500M pounds of fresh produce year-round exclusively in climate-controlled indoor facilities. Kennett Township is currently involved in a major initiative to diversify its economy by leveraging its already-extensive indoor agriculture infrastructure to create a world-class research, training and production hub for the whole indoor agriculture industry.

Water-Smart Farming: How Hydroponics And Drip Irrigation Are Feeding Australia

Water-Smart Farming: How Hydroponics And Drip Irrigation Are Feeding Australia

How energy-smart technology is allowing fresh vegetables to be grown in arid, isolated communities. Our Future of farming series is looking at the people, places and innovations in sustainable agribusiness in Australia

Is hydroponic farming the way forward for arid Australia? Photograph: Paul Miller/AAP

Wednesday, 26 April 2017 20.01 EDT

Sydney Fresh, Organic Angels, Freshline, Box Fresh. It’s a wonder Australian supermarkets still stock vegetables, such is the explosion of veg-box delivery services. OK, they may be a bit on the pricey side, but the food is out-of-the-ground fresh, typically free of chemicals and refreshingly wonky.

But for a veg-box scheme to work, the vegetables have to be grown locally. That effectively ruled out the arid wheatbelt towns of Western Australia. Or, it did, before Wide Open Agriculture opened a huge greenhouse-like facility to grow fresh vegetables. Boxes destined for domestic doorsteps have been leaving the Wagin-based site loaded with cucumbers, capsicums, tomatoes and the like.

Because we don’t rely on soil, we can osition our farm closer to centres of population

Philipp Saumweber, Sundrop

“We’ve had a lot of anecdotal feedback that we have brought the taste back to vegetables, particularly our tomatoes,” says Ben Cole, executive director at Wide Open Agriculture, the startup behind the initiative. “But our key is selling fresh vegetables in a region that doesn’t have many other local growers.”

The venture is tapping into growing consumer demand for food that is fresh and that doesn’t (environmentally speaking) cost the earth. It uses drip-irrigation technology, for instance, that requires only 10% of the water needed for open-field agriculture. In addition, the 5,400 square metre facility is equipped with a retractable roof and walls that open and close automatically, thus reducing water loss to evaporation.

The water used at the high-tech farm is sourced from natural surface water runoff that is directed into a series of dams before being pumped via a solar-powered system for use in irrigation. By capturing water high in the landscape, Cole argues, the wheatbelt’s first major vegetable producer is able to make use of it before it becomes saline.

“The wheatbelt has seen reductions in rainfall up to 20% over the last 20 years, so water scarcity is an issue for traditional wheat and sheep farmers,” says Cole, who holds a doctorate in environmental engineering and recently exited a successful social enterprise in Vietnam.

Wide Open Agriculture believes its agroecological approach to farming could usher in a new age of vegetable production in the wheatbelt. With its first harvest only just completed, it is already looking to list on the Australian Securities Exchange to raise finance for a second large-scale unit.

Another new player in Australia driving supply of water-smart food is Sundrop Farms. The Adelaide-based firm is the first company in Australia to develop a commercial-scale operation using hydroponic technology.

Sundrop Farms’ 65-hectare facility near Port Augusta in South Australia. Photograph: Sundrop

Pioneered by companies such as BrightFarms and AeroFarms in the US, hydroponic farming requires no soil or natural sunlight. Instead, plants are grown in trays containing nutrient-rich water and encouraged to photosynthesise by low-energy LEDs.

“Hydroponics is a thriving industry right across the globe, with produce being grown in a huge variety of environments” says Philipp Saumweber, a former investment banker who heads up the company. As if to prove the point, Sundrop has located its 65-hectare facility in an area of virtual desert near Port Augusta in South Australia.

One of the criticisms of the technology is that it is energy-intensive, what with all those indoor lights and automated heating and cooling systems. Sundrop has successfully ducked that charge by installing a concentrated solar power plant with 23,000 flat mirrors to meet most of its energy needs.

Saumweber is quick to push the water-efficiency credentials of the indoor farm too. With precious little rain or subterranean water to draw on, Sundrop has opted to pump seawater from the ocean and desalinate it. Its renewably powered desalination plant generates around 1 million litres of fresh water every day. The company also uses the seawater as a natural disinfectant, reducing the need for pesticides.

None of this comes cheap, mind. Sundrop’s Port Augusta farm cost a reported A$200m. Yet Saumweber insists this high upfront investment will be offset in the long run by lower operational costs, thanks to the use of cheaper renewable energy.

What can’t be argued with is the net result: 15,000 tonnes of tomatoes a year from a patch of land that is barely habitable, let alone productive. The prospect of siting such facilities inside cities is also a very real possibility, Saumweber adds. “Because we don’t rely on soil, we can position our farms closer to centres of population to greatly increase the efficiency of our supply chain.”

For the most part, however, water-smart technologies such as hydroponics and aquaponics (a related system that uses fish waste as an organic food source for plants) remain the preserve of hobby producers in their backyards.

For Murray Hallam, a Queensland-based expert and lecturer on aquaponics, the sector struggles with being seen as “just for hippies and way-out vegans” – an image he insists is false. A cultural propensity to think “it’ll be all right, mate” also holds back people from taking the risk of water scarcity and climate change seriously with respect to future food production, he argues.

The country is missing a trick, he continues: “In a regular farm, it doesn’t matter how well you organise it, when you irrigate, about 70% of the water evaporates straight away. Then the water that does get into the soil usually ends up going down to the subsoil and leaking away … taking with it the nutrients and fertiliser.”

Two of Hallam’s students have gone on to create multimillion dollar aquaponic businesses: Mecca in South Korea, and WaterFarmers, which has farms in India, Canada and the Middle East. He fears it will take a food crisis for Australian consumers to step up en masse and demand similar innovative solutions from the country’s agricultural industry.

Back amid the wheat fields of Wagin, Cole is more optimistic. Wide Open Agriculture is now looking to break into the local hospitality and retail market. It has opted for the brand name, Food for Reasons. For once a product that says what it is on the tin – or box.

Apply To The Food Sustainability Media Award

Apply To The Food Sustainability Media Award

Applications are now open for the Food Sustainability Media Award, which aims increase the public’s awareness of food sustainability issues worldwide, find solutions, and encourage action. Launched by the Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition (BCFN) and the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the award will recognize excellent professional and up-and-coming journalists from around the world who have focused their reporting on topics relating to food security, sustainable agriculture, and nutrition.

“With this award, we want to connect the everyday person with issues that are ultimately affecting all of us, and we believe media is the best route to make [this] happen,” says Monique Villa, CEO of the Thomson Reuters Foundation, in a BCFN press release.

BCFN and Thomson Reuters Foundation believe that the media can play an influential role in the way consumers think about and interact with food, helping to create a more sustainable and just global food system. With the Food Sustainability Media Award, they aim to highlight some of the major paradoxes that are impacting the global food system—such as hunger and obesity, food and fuel, and waste and starvation—as well as propose solutions and engage the public.

Entries to the Food Sustainability Media Award will be judged in three categories: written journalism, photography, and video. One published and one unpublished piece of work will be awarded in each category. Published work will receive a €10,000 (US$10,862) cash prize, while unpublished work will receive an all-expenses paid trip to attend a Thomson Reuters Foundation media training course on food sustainability. Unpublished entries will be distributed via the Thomson Reuters Foundation and the BCFN websites, and unpublished written work will also be distributed to the Reuters wire’s 1 billion readers.

Cassandra Waldron of the International Fund for Agricultural Development, Ronaldo Ribeiro of National Geographic Brazil, Laurie Goering of the Thomson Reuters Foundation, and Olly Buston of the Jamie Oliver Food Foundation are among the panel of nine experts and professionals in food and agriculture policy and research, journalism, and photography that will judge the shortlisted entries.

Applications are now open and entries can be submitted on the Sustainability Media Award’s website until May 31, 2017, at midnight (London time). Winners will be announced at the 2017 BCFN Food Forum.

For more information on the entry guidelines for each category, click here.

Future Food-Tech Is Returning to New York City

Future Food-Tech Is Returning To New York City

The Future Food-Tech Summit is returning to New York City on June 7 and 8, 2017. Investors, start-ups, technology companies, and food and ingredients manufacturers will convene to develop solutions to meet the global food challenge during the two-day event.

Among this year’s Future Food-Tech speakers are Andrew Ive of Food-X, David Lee of Impossible Foods, Nicholas Chia of Mayo Clinic, Zachary Ellis, Jr., of PepsiCo, and Susan Mayne of the Food and Drug Administration.

Panel discussions will address key questions: How can we create systems that enable access to sustainable, safe and nutritious food for all? How are retailers partnering to create the right digital experience for customers? What role can restaurants have in bringing new food experiences to customers? What is the role of governments in producing dietary guidelines and supporting research and investment in alternative proteins?

The event will include panel discussions, fireside chats, networking breaks, technology showcases, and other presentations encouraging discussion around solutions to meet the global food challenge.

Future Food-Tech is an annual event which is held in London, New York City, and San Francisco. The Summit is intended to create a forum for networking, debate, discussion, and learning while giving new food innovators the opportunity to pitch their early to mid-stage companies to an audience of global food businesses, technology integrators, and venture capital investors.

If you have a great story to tell, a game-changing solution to showcase, or would like to share your expertise on one of the panels, please call Rethink Events on +44 1273 789989 or email Stephan Groves for more information.

Click here to register for Future Food-Tech NYC.

NASA Developing Inflatable Greenhouses For Future Astronauts

NASA Developing Inflatable Greenhouses For Future Astronauts

The technology could have application for a new approach to agriculture called vertical farming

Pioneering Space Requires Living Off the Land in the Solar System ... - nasa.gov

One of the necessities for sustaining life is food. Astronauts who have traveled in space have taken their food with them, ranging from the goop squeezed from plastic tubes in the early days to microwavable dinners that astronauts on the #international space station enjoy today. Future space explorers, who may spend months or even years on the moon or Mars, will have to grow their own food. Scientists at #NASA and the University of Arizona are developing an inflatable greenhouse that will not only provide fresh vegetables and fruit for astronauts but will help to recycle the air..

Water would feed the plants, likely derived from local sources, filled with nutrients continuously circulated in the root systems, CO2, breathed out by the astronauts, would be pumped into the greenhouse. Oxygen would be pumped out. Illumination would be provided by LED lights supplemented by natural sunlight piped in through fiber optic cables. The greenhouses would likely be inside larger habitats or buried underground to protect them from radiation and micrometeorites.

Scientists are now trying to ascertain what kind of plants and seeds will provide an optimal balanced diet for astronauts on long-duration space missions. Another factor that will be hard to replicate on Earth will be how low gravity affects plant growth. The moon has one-sixth the gravity of Earth and Mars about one-third.

In the meantime, the astronauts have had some success growing food plants on board the International Space Station in the Vegetable Production System (Veggie) experiment that featured astronauts growing food under meticulously controlled conditions.

A second stage experiment, called the Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) was recently delivered to the ISS to expand space farming on board the orbiting laboratory. The APH not only has more advanced lighting that is hoped to quadruple crop yield but a suite of sensors that will track plant growth under space conditions.

The technology for growing food in space may be adapted for Earth agriculture. “#Vertical Farming” is a concept in which large amounts of food is grown under controlled conditions inside warehouses located in urban centers. The idea is that more food can be produced cheaper with lighting, air, and light under tight control than the traditional way in the ground under sunlight and rain. The fact that the vertical farms are located close to food retail outlets such as supermarkets is another plus. So far attempts to make these kinds of urban farms economically viable have had mixed results. However, given time and investments, advocates believe that the approach will serve as a new source of food divorced from the vagaries of weather. The fact that no pesticides will be needed is another plus.

5 Control System Questions With Darryn Keiller of Autogrow

5 Control System Questions With Darryn Keiller of Autogrow

Darryn Keiller, CEO of control company Autogrow, came to the company from a consulting background, and has led the New Zealand-based company to a sub $3mn equity raise since taking the helm. Ahead of his presentation at Indoor Ag-Con on May 3-4, we caught up with Darryn to ask him about big data and the future of controls in controlled environment agriculture.

1. Autogrow has created a dedicated system – RoomBoss – for controlled environment applications. What drove you to do that?

Market need. Urban and vertical systems are on the rise; from a control and automation perspective innovators in this space have either a) been sourcing from industry vendors existing technology created for Greenhouse production or b) building their own. What is needed is a technology approach that is purpose designed for systems using LED / HPS grow lights, CO2 management and integrates dosing control and all other automation requirements. The Room Boss is a Beta product that also anticipates controlling automated harvesting and robotics. It’s an Internet of Things based platform, not just a device.

2. How much of the hoopla over the application of big data in the industry is well-founded and how much is just hype?

Certainly, there is no shortage of hype. Along with machine learning, deep learning, etc. in every other sentence. The opportunity to apply these data methodologies and techniques to solve real world problems in agriculture is real. The time-line to make these effective and beneficial on a prolific basis is a lot longer than everyone would like. Part of this is due to the slow rate of market adoption and part of it is the technology development itself. Its potential is well-founded.

3. What’s the most common mistake you see beginning farmers make when picking a control system?

The first thing is considering the control and automation side of things last – this happens all the time. And it then leaves the farmer trying to find a solution with what’s left of their budget. Automating your production is key to consistently great crops and profitability through using less labour and managing inputs like water, energy and nutrients. The second part is thinking ahead – if you purchase a limited system now, then what happens when you decide to scale your operations? Sometimes spending a little more now is better than having to “rip and replace” technology later. The approach is to obtain technology that is flexible and modular, that grows as you grow.

4. What do you expect control systems to look like in five years’ time?

I expect most indoor growing environments will be fully automated with no human component except pre-planting and post-harvest. All automation and control to be cloud delivered and all physical automation will be carried out through a variety IoT devices and multi-functions sensors. This will include automated robotic harvesting – it’s already here when you look at examples like Urban Crop Solutions of Belgium or integration of machine vision solutions for crop monitoring, pest and pathogen detection as examples.

5. What’s the biggest advantage that being a Kiwi gives you?

We’re a nation of innovators, inventors and entrepreneurs – it’s how Autogrow began 24 years ago. As a nation, we have a deep history in horticulture, agriculture and pastoral production including R&D in genomics, biologics and technology. We even have our own Rocket company which despite the name was founded and is based in New Zealand. A nation of 4.5m we feed 40m people, exporting 95% of what we produce to 100 countries, every month, including beef, wool, seafood, dairy products and fruit. Because of our location, we travel the World and we embrace the idea of boundarylessness – no limits! Autogrow now exports to 30 countries around the globe.

SEE DARRYN SPEAK AT THE 5TH ANNUAL INDOOR AG-CON ON MAY 3-4, 2017

Philips Lighting Results Show LED Growth

Philips Lighting Results Show LED Growth

24 April 2017, by Matthew Appleby, Be the first to comment

LEDs now represent 61% of Philips Lighting sales, with first quarter sales at 1,690 million euros.

Philips Lighting announced the company’s 2017 first quarter results.

"Our comparable sales growth improved in comparison to previous quarters, driven by double-digit growth in our business groups LED and Home and a return to growth in Europe and the Rest of the World, despite ongoing challenging conditions in some markets," said CEO Eric Rondolat.

"We continued to increase our operational profitability and free cash flow compared to the first quarter of last year, demonstrating the rigorous implementation of our strategy.

"These results reinforce our confidence that the company is well positioned to achieve its 2017 outlook and medium term goals," Rondolat added.

On a comparable basis, the decline in sales slowed to -0.8%, an improvement compared to previous quarters. Europe and the Rest of the World delivered growth, while the Americas was impacted by an accelerated decline in conventional lighting and softer market conditions.

Business groups LED and Home achieved double-digit growth, driving total LED-based sales growth of 19% and total LED based-sales now representing 61% of total sales.

With Floating Farm, New York Looks to the Future of Public Parks

With Floating Farm, New York Looks to the Future of Public Parks

Public foraging farms are sprouting up from coast to coast, but one, in New York, has an especially ambitious social mission.

by Nikki Ekstein

March 31, 2017, 9:44 AM CDT March 31, 2017, 12:36 PM CDT

If you always thought Central Park needed more edible plants, you're in luck.

Come April, a farm full of fruit trees and other crops will float to locations in three New York City boroughs, and visitors will be invited to enjoy nature by literally picking, snipping, and sowing to their hearts' content. Located on a 5,000-square-foot barge, "Swale" will include 4,000 square feet of solar-powered growing space, including a perennial garden, an aquaponics area, and an apple orchard sponsored by Heineken USA's Strongbow Apple Ciders atop a large man-made hill. (The hill allows deeper root space for fruiting trees.)

The project will be open to the public, but it’s more interactive exhibit than floating Central Park; only 75 people can board at once, and docents will usher guests around the grounds. Free educational workshops will include “painting with plants” and “dying natural fabrics,” and volunteers will always be on hand to explain how thoughtful permaculture planning can create a virtually self-sustaining farm.

Waterpod, a predecessor to Swale, docked in Brooklyn, N.Y., in 2009.

Photographer: Michael Nagle

But founder Mary Mattingly’s goals go far beyond providing city dwellers with a high-design place to forage for mushrooms in their next attempt at Beef Bourgignon.

She wants to make people work harder for public spaces, and public spaces work harder for people. She wants to create a model for sustainable urban farming. She wants to create an educational space. And she wants to eradicate the problem of food deserts in blighted urban neighborhoods.

“We don’t have much access to stewardship in New York City,” Mattingly told Bloomberg, “so we wanted to highlight and cultivate opportunities around that idea. People care for spaces that they can pick food from.”

That's exactly what appealed to the approving committee at the New York City Parks Department. "We are trying to prioritize community engagement," said Bram Gunther, co-director of the Urban Field Station, who cited a growing field of study that believes that community involvement, empowerment, and land management must all go hand in hand. "This project will act like a magnet, in a way, and inspire people to civic action," he added.

A rendering of Swale, the floating forest coming soon to New York. Source: Swale

That's exactly Mattingly's plan. Eventually, she hopes community investment (and city grants) will take the project from floating farm to philanthropic powerhouse. She’d like to use it as a springboard to raise awareness of such food deserts as Hunts Point in New York's South Bronx, where, Mattingly says, “10,000 trucks pass through each day, and everyone has asthma, and nobody has access to fresh food.” In her perfect world, Swale becomes a conduit to a public park in the Bronx, where “people could pick food 24 hours a day.”

Here’s the only issue with that: Public policy in New York makes that kind of project legally impossible—or close to it—as it currently stands. And on a trial run last summer, Swale barely raised enough funds to keep itself going for a second season. Its manifestation this year in the East River was made possible by the partnership with Strongbow, which has made it a brand pillar to conserve and create orchards around the world. Before Mattingly can sustain entire neighborhoods, she’ll need to sustain Swale itself.

There’s reason to believe in the project, though. First, there’s Mattingly’s own record: In 2009, she spent half a year creating and living aboard a fully self-sustained ecosystem on a barge in New York, which partially inspired the Swale project.

Then there’s the success of other so-called “food farms” around the country.

In Hawaii, the Malama Kauai Food Forest supplies several underserved schools and food banks—to the tune of 37,000 pounds of fruit and 1,000 volunteer hours in the last two and a half years. In North Carolina, the George Washington Carver Edible Park anchored a major urban revitalization project near downtown Asheville, replacing a trash-filled lot with a natural source for plums, figs, chestnuts, and pawpaws, among other things. The list extends to Massachusetts, Colorado, Alaska, Seattle, and beyond.

With the exception of a nascent project in London, no other food forest has cropped up in such an urban setting. Certainly, no other initiative has as striking a design. So Swale should drum up interest. And with an advocate like Mattingly at its helm, converting interest into action should be a real possibility. Even if she fails to create her public farm in the South Bronx, she will likely open up a dialogue that can lead to lasting public policy impacts.

And let's not ignore the twin goal of creating public stewards, which Gunther says is what he most looks forward to seeing. "The benefits start with people going to Swale and thinking about it—being more aware. Others will be inspired to come out each weekend and take care of their park or advocate for it." Over time, it's something that he thinks will come to represent "an evolution of more sophisticated community engagement in the New York City parks system."

Will Mattingly sail her concept elsewhere? Maybe. “People have approached us about using our plans in other cities,” she said, “but the scope of that seems pretty big for us right now.”

At least, one thing is for sure: There’s never been a more interesting way to treat your winter doldrums.

The Regeneration Hub: Mapping the Regeneration Movement

The Regeneration Hub: Mapping the Regeneration Movement

Alexandra Groome is on the coordination team of Regeneration International (RI), a project of the Organic Consumers Association. Alexandra Groome launched The Regeneration Hub with Scott Funkhouser during the 2016 Climate Summit in Marrakech, Morocco. Katherine Paul is associate director of the Organic Consumers Association.

We, the inhabitants of Planet Earth, face multiple and accelerating global crises, including poverty, hunger, deteriorating public health, social, and political unrest. These crises are in large part a consequence of global warming, driven in part by over-consumption and irresponsible stewardship of Earth’s resources, especially its soils.

It’s fair to say that if we allow the degradation of our soils and land to accelerate, or even to continue at their current pace, these crises will only intensify.

How do we reverse course? By reducing runaway consumption and adopting agricultural and land-use practices that regenerate the world’s soils, and in so doing, regenerate local food and farming systems, local economies, human health and even our democracies.

Individuals and groups around the world are researching, launching, testing, and promoting agricultural and land-use projects that hold great promise for addressing our impending global warming crisis. (For more on how regenerative agriculture is key to cooling the planet and feeding the world, check out these resources).

To connect these local “regenerators” so they can exchange research and share expertise with others working in faraway places, and thereby propel the acceleration of regeneration, on a global scale, Regeneration International (RI), Open Team, and a coalition of 17 other organizations leading the regenerative food and farming movement have launched the beta version of The Regeneration Hub(RHub). RHub is an open platform that aims to accelerate the regeneration movement by encouraging collaboration among various groups and individuals focused on regenerative projects involving reforestation, seed saving, holistic land management, permaculture gardens, and agroecology networks.

Creating a digital platform to spread the message of regeneration

The idea for RHub came about during the 2015 COP21 Paris Climate Summit, as representatives of RI, Open Team, and others brainstormed ways to better connect those working within the regeneration movement. Eleven months later, RHub was launched (still in beta version) during the 2016 United Nations Climate Summit in Marrakech.

Though still in the early stages, RHub has signed on more than 90 regenerative projects. In an effort to kick-start the program, RI will award five US$1,000 grants to fund innovative regeneration projects around the globe. To apply for the call-for-projects, “Five Innovations for Regeneration,” applicants must register a project on Rhub.com and complete an online profile by March 31, 2017.

“There are regenerative solutions all around us,” said Ronnie Cummins, co-founder and international director of the Organic Consumers Association and RI steering committee member. “But people are working in silos. We need to map out and connect the global regeneration movement in order to speed up the exchange of best practices and the sharing of knowledge and resources on a global scale,” he said.

Meet the projects signed on to RHub

Here is just a sampling of projects that are already using RHub to connect with fellow regenerators:

Terra Genesis International (TGI), based in the U.S., is a RHub project dedicated to reversing climate change by transforming US$100 billion in purchasing power and 500 million hectares of land into regenerative agriculture. The folks at TGI are experts when it comes to designing regenerative farm landscapes that increase nutrient-dense food production and improve livelihoods.

Worldview Impact, based in India, is a global social enterprise that provides made-to-order services for cooperatives of small-scale organic farmers in developing countries. Worldview Impact’s goal is to integrate and expand farming systems that integrate agroforestry, bring local products to market, and create market linkages with the emerging sectors of regenerative supply chains and agro-ecotourism. Worldview Impact is in search of donations to help fund its agro-ecotourism initiative.

Sustainable Harvest International (SHI) based in Panama, aims to preserve the environment by partnering with families to improve their wellbeing through regenerative farming. SHI has two decades of experience training farmers how to transition into regenerative agriculture. The project is currently seeking sponsorship and donations to hire more staff to connect with farmers waiting to join the regenerative agriculture transition program. The goal is to expand these practices so they have a global effect.

Get involved and qualify for a micro-grant

Registering at RHub.com will allow you to join a growing global community and connect with others focused on regeneration. The platform allows you to interact with ongoing projects, even if you don’t yet have one of your own.

Registering a project with a complete profile on RHub.com will also allow you to apply for one of the five US$1,000 grants, which will be funded by RI. Grantees will be connected with experts to help support their projects, as well as will be featured on RegenerationInternational.org. The group’s steering committee will evaluate the projects and announce the winners in April 2017. Click here for more info.

Become an RHub partner or pollinator

Becoming an RHub partner offers a great opportunity to support and be part of an international network of regenerative solutions. Whether you have a network that’s seeking to expand and connect with projects worldwide or are interested in helping spread the message, RHub partnership has many benefits. We even display your logo on the official partner’s page. Send us your high-resolution logo to info@regenerationhub.com.

Interested in taking more of a leadership role in spreading regenerative solutions in your locale? We’re seeking global regenerators to help build our platform. To learn more about becoming a community pollinator, email us at info@regenerationhub.com.

A Conversation With Food Tank’s Danielle Nierenberg

A Conversation With Food Tank’s Danielle Nierenberg

By Brian Barth on March 28, 2017

anielle Nierenberg’s experience with agriculture goes all the way back to her roots in the rural Midwest. Though she admits that back then, “I didn’t want to have anything to do with farming.” To say that she has now changed her tune would be an understatement.

The feisty founder of Food Tank—as the name implies, it’s a think tank for the food system—always seems to be in three places at once, whether holding court in a farmer’s field, penning op-eds for major newspapers, or onstage, microphone in hand, smiling at a group of esteemed panelists assembled to discuss some obscure but important topic like the agroforestry systems of Afghanistan, while grilling them about their assumptions and the scientific validity of their work. (Full disclosure: Nierenberg is on the Modern Farmer Advisory Board, too.)

Food Tank is most widely know for its “food summits,” which occur sporadically throughout the year in different cities around the globe (the next one is April 1-2 in Boston). You could describe the summits as sort of a food-centric version of Ted Talks, but Nierenberg makes it clear that these aren’t just feel good preaching-to-the-crowd conventions. They’re about bringing food system players together who might not normally talk to each other—who might hate each other guts—and drawing them into a meaningful public debate on the most pressing issues of the day. No Power Points slideshows here, she says: “We don’t want to allow people to just give their usual spiel that they would give at any sort of industry event or sustainable agriculture conference. Sometimes it’s important to have an uncomfortable conversation, and allow for unusual collaborations to develop.”

I don’t like to romanticize farming; but we’re hoping to make sure that young farmers know that they are not alone,

This month, the Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture released Letters to a Young Farmer, a collection of essays by 36 leading thinkers in the food world which addresses a certain white elephant: the average age of American farmers is 58.3. Thus there are now more farmers over the age of 75 than between the ages of 35 and 44, which says something about the appeal of the profession in contemporary society. Nierenberg, who contributed an essay to the anthology (along with the likes of Barbara Kingsolver and Michael Pollan), recently sat down with Modern Farmer to share her thoughts on this, and other, essential subjects facing the future of our food system.

Modern Farmer: What was on your mind when you sat down to write your essay for Letters to a Young Farmer?

Danielle Nierenberg: My letter talks about being someone who grew up in a rural Midwest environment and didn’t want to have anything to do with farmers. I thought what they were doing was stupid and I didn’t get it. But in my own personal evolution I’ve learned so much from farmers, as a Peace Corps volunteer when I was younger and later in my career with Food Tank and other organizations. I’ve been able to spend time on farms both in the United States and around the world and get a sense of the important work that farmers are doing every day.

I don’t like to romanticize farming; but what the book is hoping to do is make sure that young farmers know that they are not alone, that there is a growing movement that wants to support them. I thought about what would I want to hear if I was a 22-year-old fresh out of college and embarking on a life as a new farmer. We’re seeing so many people giving up lucrative jobs and turning to farming because they think it’s important.

We’ve forgotten that farming is super knowledge-intensive, or at least it should be.

MF: Do you think the agriculture world is making progress in attracting new farmers?

DN: We are certainly seeing a surge in organic operations, but you don’t see a lot of the folks that I grew up with in the nineties in the Midwest who stayed on the farm. Most didn’t want to. So I think we have a long way to go, especially now with the Trump administration. We made some headway over the last eight years with USDA programs to encourage young farmers, including mentoring programs that link younger farmers with older experienced ones. I fear that a lot of that will disappear and young farmers won’t get the resources and support that they need.

MF: Riding a tractor all day by yourself through a field of corn and soybeans isn’t an appealing job description for a lot of people. Is part of the problem that farming is not sexy enough as an occupation to draw the millennial crowd?

DN: I don’t want to demonize the folks who are operating those large commodity farms, because they have a lot of valuable knowledge and skills. Despite the stereotypes a lot of those folks are actually using very advanced technology to grow crops more efficiently and I don’t want to undermine that in any way. I encourage the integration of high tech with traditional techniques—combining GPS and drones and crop data on your cell phone and all this other cool stuff that’s happening in modern agriculture with cover crops and green manure and native species. I think there is a real opportunity for farmers of all sizes to make farming intellectually stimulating and exciting. We’ve forgotten that farming is super knowledge-intensive, or at least it should be.

MF: Sounds like agriculture has a branding problem.

DN: For folks out there who are looking for something that surprises them every day and invigorates them in a way that working on Wall Street or at a tech company doesn’t, I think they can find that in farming. We have this illusion that farmers are farmers because they are dumb, that they ended up on the farm because they didn’t go to college and don’t have any other opportunities. I think that perception is really changing, but it’s a slow road.

It’s an especially slow road in developing countries where often the government is telling you to get out of farming and move to the city, that they’re not going to support farmers. There is a lot of work to be done to change those perceptions and encourage investment in agriculture so that it’s attractive for young farmers all over the world. But I’m encouraged by what we have seen over just the last five years with Silicon Valley being more interested in investing in sustainable food systems—that will be hard for the new administration to ignore.

If you’re interested in what makes good business sense, what makes money, you can’t deny that having more organic, planet friendly, and plant-based products is a good idea. Those things have been successful because the demand is there. I don’t think it’s going to work to ignore that now and focus on what is essentially a 1980s philosophy for the food system. But unfortunately I don’t think this administration realizes that.

MF: Now that you’ve brought it up, what else worries you about Trump in regards to food and farming?

DN: I’m very apprehensive about what’s going to happen with the next farm bill. I think we are going to have to fight hard to maintain what we gained over the last eight years rather than trying for a lot of new things. The connection between immigration and farm labor is another thing where I think the new administration is totally behind the times. They don’t understand that without those folks, whether they are documented or undocumented, our food system would come to a grinding halt. The people who are growing, harvesting, preparing, and serving our food need to be better recognized for what they do. (Editor’s note: For more on immigration and farming, see “The High Cost of Cheap Labor” from our Spring 2017 issue.)

MF: Food Tank summits have been a fantastic forum for bringing all the stakeholders in the food system to the table, including farmworkers. Why is that important to you?

DN: Our mission is to highlight stories of hope and success in food and agriculture, both domestically and globally, and provide that inspiration to others who need it. I started Food Tank to give a different side to the story of food that was based on the work that I’d done interviewing hundreds and hundreds of farmers and other food system stakeholders around the world. I worked for an environmental organization for many years and it was very doom and gloom, always focusing on the problem. At Food Tank we also highlight where we think the system is broken, but what we really want to do, through the articles that we post every day online, through our newsletter and webinars and podcasts and research reports, is to give people examples of what is working.

Sometimes the things that are working are not getting a lot of government support or funding, so imagine what the world would look like if all those things got the support they needed to be really successful? We want to get those stories out there to a wider audience and show people what needs to be scaled up.

Without immigrants, whether they are documented or undocumented, our food system would come to a grinding halt. The people who are growing, harvesting, preparing, and serving our food need to be better recognized for what they do.

MF: You’re a bit notorious, if I may say so, for bringing people together who have strongly opposing views.

DN: We want to bring people together for the sake of good conversation, but sometimes it’s important to have an uncomfortable conversation, and allow for unusual collaborations to develop. We don’t want to allow people to just give their usual spiel that they would give at any sort of industry event or sustainable agriculture conference. We’ve brought together food labor and justice leaders on the same stage as scientists from Monsanto and Bayer and essentially forced them to talk to one another. It’s healthy to have to answer hard questions and sit next to people on stage or at lunch or in the audience who you never wanted to talk to.

I’ve been doing this for a while now and I’ve seen that preaching to the choir hasn’t gotten us anywhere. If we’re only talking to people whose viewpoints are similar to our own, we are never going to change things. That doesn’t mean I agree with Monsanto, and it doesn’t mean I agree every sustainable food advocate out there, but I do think we need to find where we can agree on things, acknowledge where we can’t, and then find ways to move forward.

We have a president who is not listening to anyone else and that’s not getting us anywhere, it’s just creating a lot of bitterness and anxiety. It’s the same in the food movement—if we want anything to change, we need to start listening to one another.

When we are talking about climate change, every story should include agriculture.

MF: In many ways Food Tank acts as a media organization, blanketing the airwaves with all these new ideas about food. What you think of mainstream media organizations and how they portray the food system?

DN: I feel they are still so behind the times. That’s not to say that The New York Times hasn’t done some amazing reporting over the years on different aspects of the food system—you can’t ignore a publication where both Michael Pollan and Mark Bittman have contributed so much amazing writing. But when we are talking about climate change, for example, every story should include agriculture. Every story about urban conflict should include agriculture. I still think there’s a tendency to not understand that the food system is not only involved in many of these issues, but it can also contain solutions, whether it’s to help alleviate a conflict, find ways to quell migration, or to better engage youth at school.

So I tend to be very disappointed with mainstream media. Anything about agriculture is usually buried below the fold of the front page or inside the newspaper because it’s something that not everyone is interested in—but they should be. Why the famine in sub-Saharan Africa is not on the front page every day, or the role of agriculture in climate change, not to mention its ability to help mitigate and reverse the effects of climate change, I do not know.

MF: You seem to keep at least one foot, and sometimes two, in the international realm of agriculture. What’s the message that you want US consumers to hear about agriculture in the developing world?

DN: Great question. It’s not just what I want consumers to know, it’s what I want other farmers to know. I feel like there has been a tendency for farmers in wealthier countries to think they have so much to teach farmers in other parts of the world, and that the transfer of knowledge and technology would naturally always come from the United States. In some cases that’s true; I think farmers here have a lot to share and that north-south collaboration is important. But what I am really invigorated by, and what I’ve actually seen a lot of, is that we have a lot to learn from farmers in the Global South. So I would love to see more of that south to north sharing of information.

We shouldn’t be ignoring farmers in the rest of the world just because they might be “less developed than we are.”

MF: What might that look like?

DN: Many farmers in developing nations have been dealing with certain things for a long time that are kind of new to American farmers, especially in terms of climate change. Like the wildfires that devastated livestock farmers in the Midwest over the last few weeks and the drought in California. Things like that are an everyday thing for many farmers in poor countries. Those farmers have learned to pivot and change their production practices quickly, though I grant that these farms are often a lot smaller than those in the United States.

There is also a lot to share around things like agroforestry, growing more indigenous and locally-adapted crops, and working with traditional livestock breeds. These are all things that could serve as important lessons for farmers in the United States and in other rich countries. We shouldn’t be ignoring farmers in the rest of the world just because they might be, quote-unquote, less developed than we are.

MF: In a similar vein, what do you think a conventional commodity crop farmer from the Midwest might have to teach a young aspiring organic farmer?

DN: I think many of these older farmers really understand the business of farming in a way that many upstart farmers do not. It’s easy to forget that farmers are businessmen, and businesses need business plans. Idealistic young people in every profession go in not knowing exactly what they’re doing financially. When I started Food Tank I didn’t have a clue about fundraising. Fortunately I had great help from my board to help me figure that out. Those are skills that we all need to learn, and hopefully we find great mentors along the way. But we also need a government that supports farmers in learning those essential skills.

Danielle Nierenberg speaking on a panel/photo by Stephan Röhl on Flickr

Three Ways To Urban Agricultures: Digging Into Three Very Different Offerings From Three New Books

Three Ways To Urban Agricultures: Digging Into Three Very Different Offerings From Three New Books

By Wayne Roberts

When Socrates, Plato and the gang had their dialogues about the inner essence of beauty, truth and justice, while hanging out at the farmers market in downtown ancient Athens, they had no idea of the problems they would create for urban agriculture 2500 years later.

Unfortunately, urban agriculture is still all Greek to many city planners.

That might seem like a stretch, but give me a chance to make my point. The ancient Greeks established the pattern of looking for absolute and universal Truth in the singular. The simplest way to see the legacy of this tradition in today’s thinking about food is to look at all the single-minded words. Think of such commonly used expressions as food policy, food strategy, food culture, local food, sustainable food, alternative food, and urban agriculture. Not much pluralism, plurals or variation here!!

We betray the Greek origin of western styles of thinking every time we use the singular to discuss potential options with regard to the abundance of foods and food choices that urban lives and modern technologies provide (please note my use of the plural).

So, for example, we have city discussions about the need for a city policy on urban agriculture, instead of city discussions about the need for city policies to support various forms of urban agricultures.

The ancient Greek philosophers, despite many wonderful ideas they developed, were hung up with locating the one and only essence of things — an abstraction that was independent of the ups and downs of momentary appearance.

They didn’t like messy realities because they were too messy, and left that world to slaves and women. That tradition is still alive and unwell, as the low wages and standing of agricultural and food preparation work shows. The jobs that pay well are jobs removed from messy realities.

Likewise, to this day, a narrow and absolutist mindset straitjackets our thinking about food policy in cities.

Alfonso Morales edits new book on many forms of city farms

To wit, the way cities agonize over a policy (note the singular) for urban agriculture (note the singular), rather than a suite of policies (note the plural) to help as many who are interested, for whatever reasons (note the plural), be they love or money, to eat foods (note the plural) they have grown or raised or foraged in varieties (note the plural) of spaces (note the plural) — from front yards, to back yards, to green roofs, to green walls, to balconies, to windowsills, to allotment gardens, to community gardens, to beehives, to butterfly gardens, to teaching and therapeutic gardens, to edible landscaping, to soil-based, hydroponic and aquaponic greenhouses, to vacant lots, to public orchards, to community composting centers, to grey water recycling for lawns and gardens, to formally-sited farms and meadows.

LET ME COUNT THE WAYS

There are so many opportunities, so many points on the urban agricultures spectrum, that we can’t even say “urban agriculture is what it is.”

That fact is that “urban agricultures are what they are,” and city governments in different areas should embrace many of them.

Of course, public authorities need to practice their usual due diligence in terms of personal and public safety, but the emphasis of policy should not be on toleration or permission, but management and stewardship of the health, environmental, community and economic yields of urban ag.

Janine de la Salle’s wake-up call

This is in marked contrast to the present mode of civic management over urban agriculture. City food planning advocate Janine de la Salle, who has the fortune to work in Vancouver, which is an exception to the rule, describes the norm as one where officials need a wake-up call because they’re managing urban agriculture in the same passive way they manage sleep, another essential of life. Like sleep, urban food production is treated as “necessary, but not meant to be regulated or managed in any meaningful way,” she writes in her chapter in the book Cities of Farmers.

That nice little dig (there are many ways to dig in support of urban agricultures) brings me to the business at hand in this newsletter, a review of three fairly new resources (two books, one assortment of essays) on urban agriculture — each of which sheds a distinctive light on the growing possibilities of urban food production.

VIEWS FROM MADISON

The best to begin with is the collection edited by Julie Dawson and Alfonso Morales, called Cities of Farmers: Urban Agricultural Practices and Processes. It sets the stage.

Horticulture expert Julie Dawson co-edited Cities of Farmers

The two editors come from the state university in Madison, Wisconsin, where the late city planning authority, Jerry Kaufman, spread his protective wings around a new generation of urbanists who now teach and practice city food planning around the world. Before Kaufman, the conventional wisdom of city planners was that food was produced in rural areas and consumed in cities; cities should stick with making things that provided the “highest use” of expensive city land. This anthology, which breaks totally from convention, is a worthy basket from the harvest Kaufman seeded. (To be transparent, I am as indebted to encouragement from Kaufman as any of his students.)

Jerry Kaufman, godfather of city food planning

To be more transparent, I got to see this book before it was published, so I could write a back cover blurb drawing attention to its “down to earth quality” that can help city planners, health promoters, community developers and “all who love what a garden does for a day outdoors, a yard or parkette, a great meal, and quality time with others.”

The breakthrough of the book, in my view, is that it doesn’t ask the ancient and unanswerable philosophical question about “what is urban agriculture.” Instead, it asks the more pointed and fruitful question: what do urban agriculture projects do.

The book’s answers (note the plural) form the most comprehensive overview yet of how the “multi-functionality” of both agriculture and food can generate the many benefits that urban agricultures bestow on cities.

Producing food may well be the least accomplishment of urban agriculture, though that extra food can really make a difference for people on low income. But the crop itself is only one contribution on a long list that includes enhanced public safety, community vitality and cohesion, neighborhood place-making, skill development, food literacy, garbage reduction (through composting) and green infrastructure.

down to earth look at urban ag

As Erin Silva and Anne Pfeiffer argue in their chapter on agroecology in cities, the sheer range of benefits bestowed by urban agricultures dwarfs the efficiency of any one particular contribution — be it food production or the development of community food literacy. This knocks the economic analysts for a loop because the premise of this book is that the whole is greater than the part, and the efficiency comes out of the whole, not any one part. “Though food production remains a central focus for many operations,” they write, “ it is often a means to achieve other social benefits rather than the singular goal.”

As I used to put it during my working days at the city of Toronto, the success of all forms of food activities, including urban agricultures, rest on the economies of scope, not the economies of scale.

Therein lies the key to measuring true productivity, and when we understand why that breakthrough method of measuring progress in food matters, we will come to see the potential of totally different methods of managing and incentivizing food activities.

HOW DO YOU GET TO GARDEN AT CARNEGIE HALL? PRACTICE!!

Though I like all the essays in the book, the one that knocks my socks off is by Nevin Cohen and Katinka Wijsman. It highlights the central role of food practices in a way that points to new ways of promoting food activities that go far beyond the boundaries of urban agricultures. (Are you becoming more comfortable with all the plurals?)

Nevin Cohen, co-author, practices looking like a gardener

This essay is fundamental to anybody who want to make the journey from food policy to implementation of new food practices.

I never had a policy of brushing or flossing my teeth after a meal. But sometime before I remember, I learned the practice of brushing my teeth — though I learned the wrong practice that was standard in my day, of scrubbing up and down and side to side, not gently brushing up or down from the gums to prevent gum damage. Unfortunately, I didn’t get the practice right in time to save my gums from painful and expensive dental work, which also instilled in me the practice of flossing. At this point, flossing is no longer a policy decision I make, but a practice I follow “automatically.” That norm of “practice”is one followed by people who practice anything from medicine to yoga, and we now need to normalize it in good food practices. As medicine, yoga, Cohen and Wijsman make clear, policy is the servant of practice, not the other way around.

Their essay reviews how New Yorkers went from policy advocacy to practices that implemented community gardens. They not only normalized community gardens on the most expensive real estate in the world, they incorporated forms of urban agricultures into the basic infrastructures of a city — from green roofs and walls to green paths and street greenings that manage stormwater.

The gardening version of pilgrims’ progress in New York City has been as much about advancing practices as policies, Cohen and Widjsman argue.

Indeed, practices need to become the a lens for all people who seek meaningful food system changes in food. Part of the thinking behind a city establishing a food policy council or urban agriculture sub-committee is to provide an institutional focus for the new civic practice of automatically saying “we can do our due diligence on food practices by referring this issue on (whatever) to the food policy council and urban ag committee, and asking if we overlooked any possible food enhancements.”

We have come full circle from Plato and the ancient Greeks, who saw theory as the exemplar of purity, not defiled by the shadows in the caves that people lived in. This is why we now need to refer to people who get the new paradigm of meaningful change as “communities of practice.”

Developing such communities is the way we build vehicles for food system transformation, just as people who practice yoga or medicine or meditation work their changes.

When you have finished this book, you will be mentally ready for the latest practices from one of the master practitioners of organic food production.

ABLEMAN’S ABILITY

Michael Ableman is one of the preeminent growers, photographers, speakers, writers and entrepreneurs produced by the global organic movement. He was able to bring all these mature skills and practices to the most delicate, fragile and responsible project of a lifetime — cultivating the skills and practices of 25 employees from Vancouver’s notoriously drug-ridden Downtown East End to the point where they tended five acres on four beautiful and productive food gardens. Urban agricultures don’t get much grittier than this. Ableman’s book, Street Farm: Growing Food, Jobs, and Hope on the Urban Frontier, tells the story.

Street Farm goes beyond-down-to-earth; it’s down to pavement

There was no utopian vision — it takes a practiced hand to know to steer clear of that — but Ableman and his crew “wanted the world to know that people from this neighborhood, those who were viewed as low-life losers, could create something beautiful and productive; that they could eat from it, feed others, and get a paycheck from its abundance; and that it could sustain itself for more than a few days or weeks or months or years.”

If urban agricultures can accomplish something akin to that, city gardens can produce something every bit as essential as food. This is what people-centered food policy is about.

Devoted organic grower and foodie that he is, Ableman digs the people-centeredness of this urban agriculture project. Employing and enabling the neighborhood farm workers is the mission of the street farm, he writes, citing the Japanese farm philosopher Masanobu Fukuoka who insisted the “ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation of human beings.” He came to regard his fellow workers as “farmily.”That does put urban agricultures in context, and explains why land-use policy for urban agriculture deserves to be classified as among the “highest uses” of urban land.

Ableman also understands that urban agriculture is not just rural agriculture in a city. It sometimes has to be adapted in stark ways. He came to understand, for example, that a paved parking lot was an ideal foundation on which to build, and that the best way to grow was in some 5000 wood and plastic bins (almost 10,000 at the time of this writing), which can be moved when a lease or a welcome run out.

Does Abelam see urban ag as another way to bring art to the people?

He also understands the centrality of partnerships and of champions on city staff to his success; they are the city farmer’s environment, as important and immediate as nature is to the rural farmer. At one point, he even argues that the crisis of global industrial agriculture is, above all, “a crisis of participation” — which distances people from their food as much as the 5000 mile trip that Asian rice takes to a plate on the eastern seaboard of the Americas.

WHAT HUMANS HAVE IN COMMONS

Ableman’s understanding of the centrality of engaging the human side of food production (should we call it human-centered food policy?) is the segway to the third body of work considered in this newsletter on urban agricultures — the work of Chiara Tornaghi at Coventry University in England.

As I read her articles, Tornaghi is so bold as to put our psychic needs of our deeply-rooted human spirit on par with deeply human physical needs for food — and thereby to classify citizen access to urban food production as essential. Only such a deep understanding of the need to engage with and participate in food production could account for her proposal that access to food production opportunities be classified as part of a citizen’s inborn and inherent “right to the city.”

Gardening activist Chiara Tornaghi and her assistant

Tornaghi’s work is accessible in a variety of places — including one article on how to set up an urban ag project, and one pieceon the critical geography of urban ag, and one study on urban ag and the politics of empowerment, and one reporton gardening activism, as well as a publication on European urban agriculture.

She’s pretty much out there, with phrases such as “insurgent urbanism” and “politics of engagement, capability and empowerment,” along with references to the commons, metabolism and other clues that Tornaghi has spent as much time in obscure sections of libraries, as in gardens.

At the very least, she is refreshing. People concerned about the runaway rates of mental ill-health among young people cannot ignore what she has to say about addressing human needs to work directly in nature — and thereby counterbalance the highly built, urbanized, synthetic, abstracted, impersonal, mediated and corporate-controlled environment of dense cities.

In my view, this mental health and well-being perspective is the most urgent and compelling reason for city planners and managers to listen up on the subject of urban agricultures.

I don’t want to gild the lily of what she has to say. There are calls to action from earlier times that call for direct action, by which was meant “take power into your own hands, and come to a demonstration calling on someone else to do something.”

By contrast, Tornaghi’s is a direct action call to meet with your neighbors, find a place to stand, dig in, and get your hands in the dirt. It deals with justice not just as a distributive matter — how to divvy up the harvest so the one per cent don’t get almost all of it and the poor get little — but a capability matter: the right of people to develop their capacities and not have to settle for a consuming life that renders us spectators of our own lives.

WE ARE WHAT WE GROW

Steven Bourne of Toronto’s Ripple Farms finds himself and a job

You shouldn’t have to leave the city to get in touch with your deeper self.

Tornaghi’s is a shout-out to go beyond the civic benefits that urban agriculture provides a city to the human benefits food production bestows on that undomesticated “gardener” and “forager” part of our inner being, brain, mind and soul. If that is not well, then life in cities cannot be good.

Although there is huge wisdom in the clichéd phrase about “we are what we eat,” we now need to recognize that we are just as much what we forage and grow and make. We are also what we grow and produce. We evolved to eat in certain ways, and we also evolved to feed ourselves. The two are inseparable. The two were severed by industrial agriculture, which turned most eaters into consumers. Now we need to heal that breach.

Urban agriculture is the ultimate offering that food makes to people in cities — not what has long been considered the punishment of hard labor, meted out to humans as penalty for their sins, but what is really food’s greatest gift — the opportunity to engage and participate in the labor as well as the joys of meaningful work.

SALAD DAYS OF CITY FARMING

I’m look for a fourth book to round this picture out, a book that captures the energy of a new generation of city farmers who are growing salad greens in freight containers repurposed as greenhouses. They can fit into any number of small places and provide conditions for growing fish (aquaponics) and greens (hydroponics), together or separately.

Brandon Hebor

Like Steve Bourne and Brandon Hebor of Ripple Farms in Toronto, these ecopreneurs repurpose old freight containers, rescuing them from landfill, outfit them with grow lights and containers for fish and plants, and locate them in an out-of-the-way but accessible space (in this case, just by the parking lot of the popular Brickworks farmers market) where the 100 yard diet applies to producers and shoppers.

They can grow microgreens and fish, and they can grow micropreneur jobs by the tens of thousands — with a potential for each micro-green micro-business to supply one farmers market, or one food truck, or one school meal program, with fresh-grown greens and fish from the neighborhood.

Talk about a disruptive business model that will affect the way people can access ultra-local fresh greens and fish for 12 months of the year!!!!! They’re so close to their customers, they don’t even need to call Uber for deliveries!

Indoor ag is just one of the many ways that the many forms of urban agriculture can benefit cities. There are many more to put in the urban ag bucket list.

(Wayne Roberts also produces a free newsletter on food and cities. It links readers to all his publications, and provides other timely information from the field. To sign up, go to http://bit.ly/OpportunCity)

The Future of Food

The Future of Food

MARCH 20, 2017 18:06

From computer-monitored growing chambers and vertical farms to superfoods, the increasing needs of a burgeoning population have led to technology-fuelled innovations in agriculture

If history is to be believed, the plow and seeder were invented by the Mesopotamian civilisation in 3000 BC. In 2017, if you do a Google search on technology used in farming, the results would display similar tools, with the exception of the innovations of the last century.

How does limited evolution in farming technologies fare against the challenge of feeding a population this world has never seen before? In the late 1950s, when serious food shortages occurred in developing nations across the world, efforts were made to improve the growth of major grain crops like wheat, rice and corn, by creating hybrid grains that responded well to the application of fertilisers and pesticides. This meant, especially for countries in Asia, high yields per hectare. However, the repercussions of ever-increasing use of chemicals are now visible, with many diseases being traced back to the use of chemically-grown food. A technology that was supposed to help feed the growing world has proven to be more hindrance than help. Today, more people are moving towards organic produce, but the question remains – how do we connect growing more and better with healthy and organic?

At a TED Talk in December 2015, Caleb Harper, Principal Investigator and Director of Open Agriculture Initiative at MIT Media Lab, gave a peek into the future of urban agricultural systems.

His team has created a food computer, a controlled-environment agriculture technology platform that uses robotic systems to control and monitor climate, energy, and plant growth inside a specialised growing chamber. Climate variables such as carbon dioxide, air temperature, humidity, dissolved oxygen, potential hydrogen, electrical conductivity, and root-zone temperature are among the many conditions that can be controlled and monitored within the growing chamber. While the food computer remains a research project at the moment, there are companies using technology in their current food-growing ecosystems.

Japan has been experimenting with Sandponics, a unique cultivation system that uses no soil, only sunlight and greenhouse facilities.

A small section of sand is supplied with a mix of essential nutrients, and in some cases, the same section of sand has been in use for over three decades. The first systems were developed in the 1970s and are still evolving today. They have proved to be not just efficient, but affordable and scalable too.

The 750-square-kilometre island of Singapore, feeds a population of five million by importing more than 90% of its requirement. With available farmland being low, the only way to grow food is to go vertical. This is where vertical farms and farming entrepreneurs and companies such as Sky Greens have come up with innovative solutions that are not resource-intensive.

India initiatives

India isn’t far behind in exploring urban farms either. Chennai-based Future Farms, Jaipur-based Hamari Krishi and a few others are bringing the urban farm revolution to India.

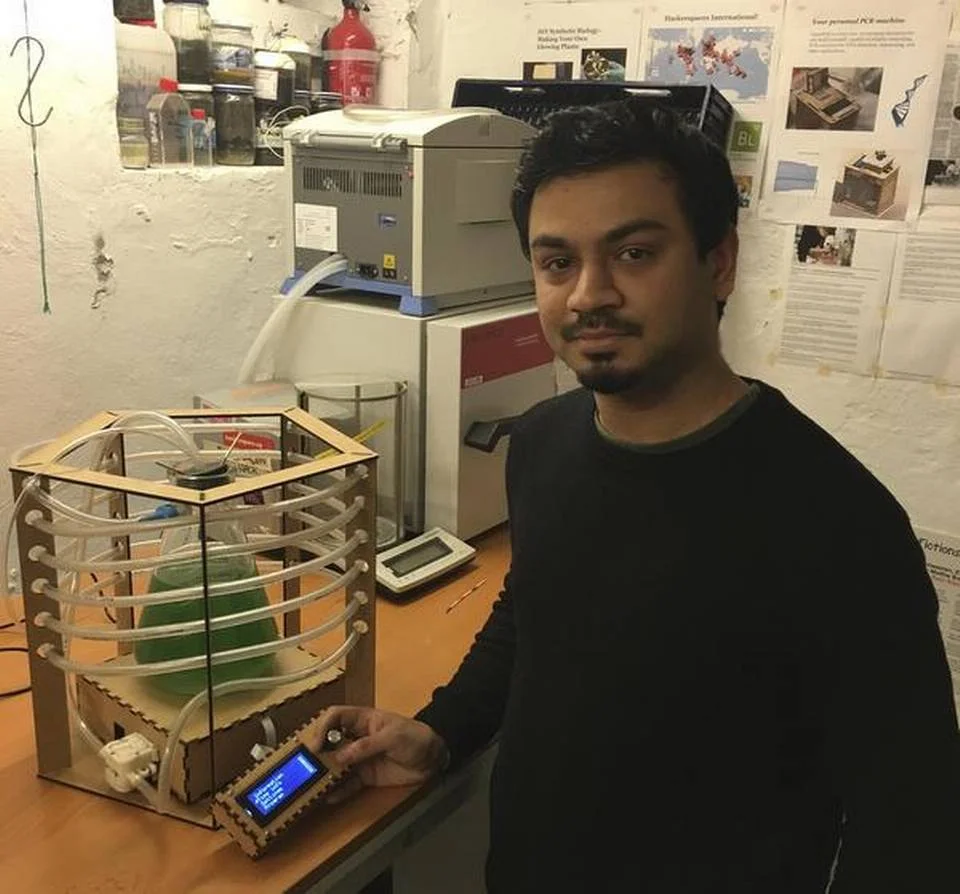

Most of the above technologies will help increase the yield in terms of quantities, but what about the nutrient value? Around the world, companies and researchers are spending time to find the next superfoods, something that our species might not be able to survive without. While some might think cricket (yes, the insect) flour is too extreme, there are those who consume it. Keenan Pinto, an engineer with a background in molecular biology and biotech, has created a bio-reactor for micro-algae after hearing that Spirulina could hold the key to fighting malnutrition. Companies such as Soylent (USA) and Onemeal (Denmark) have been making highly-engineered minimalist food powered by micro-algae, that only need water to make a liquid meal with 20% of daily nutritional value of a person.

NASA’s data has already shown evidence of drastically depleting groundwater resources in North India, and Pinto believes this makes initiatives like the Soil Health Card (a scheme launched by the Government under which farm soil is analysed and crop, nutrient and fertiliser recommendations are given to farmers in the form of a card) the need of the hour.

In the past two years, the image of agriculture and farming technologies has changed from a sickle and plough to computers and vertical farms.

As need grows, our food systems are destined to evolve, and it is our job to evolve with them.

Five of Brooklyn's Most Innovative Urban Farms

It may be a cliché to lament the loss of farms in New York City. These five Brooklyn-based urban farms, mostly co-founded by former Wall Street professionals, are using the most creative and entrepreneurial techniques, from aquaponics to vertical growing, to bring fresh, locally grown produce to New Yorkers.

FIVE OF BROOKLYN'S MOST INNOVATIVE URBAN FARMS

New YorkSustainability Mar 16, 2017 Kouichi Shirayanagi, Bisnow

It may be a cliché to lament the loss of farms in New York City. These five Brooklyn-based urban farms, mostly co-founded by former Wall Street professionals, are using the most creative and entrepreneurial techniques, from aquaponics to vertical growing, to bring fresh, locally grown produce to New Yorkers. Beyond the health benefits of eating fresher produce, locally grown food benefits the environment by cutting out the need to transport and preserve perishable fruits and vegetables, which can take more than a week to get from the farm to a New York City dinner plate.

Gotham Greens Location: 810 Humboldt St., Greenpoint Co-founded in 2009 by a sustainable development manager and an ex-JP Morgan Chase private equity fund manager, Gotham Greens produces organic leafy greens, lettuces and tomatoes from the tops of buildings in Greenpoint and Gowanus as well as in Hollis, Queens. Early in the business, partners Viraj Puri and Eric Haley developed a relationship with Whole Foods to distribute their produce. In 2013, Gotham Greens built a 20K SF greenhouse on the roof of the Whole Foods store in Gowanus. The project marked the first time a greenhouse integrated with a major grocery store. The first Gotham Greens greenhouse, built in 2009 in Greenpoint, is 15K SF and produces 100,000 pounds of produce a year.

Red Hook Community Farm Location: 560 Columbia St. and 30 Wolcott St., Red Hook Managed by environmental educator Saara Nafici, Red Hook Community Farm produces more than 20,000 pounds of produce a year from two Brooklyn sites. The 120K SF farm on Columbia Street uses ground compost two-feet deep to create a diverse environment of microorganisms and insects that nourish the produce. Red Hook Community Farm also built a 48K SF site on Wolcott Street in collaboration with the New York Housing Authority. Members of Green City Force, an AmeriCorps program, maintain the farm. The organization maintains a Saturday farmers market at the Columbia Street site between June and November to sell the farm's produce.

Eagle Street Rooftop Farm Location: 44 Eagle St., Greenpoint Managed by educator and journalist Annie Novak, the Eagle Street Rooftop Farm occupies 6K SF on top of a warehouse in Greenpoint. The farm grows a wide variety of vegetables, spices and greens, including hot peppers, eggplants, sage, parsley, cilantro and dill. Novak sells produce from the farm at an on-site Sunday farmers market.

Brooklyn Grange Location: McGolrick Park, Greenpoint Co-founded by former E*Trade Financial consultant Ben Flanner and longtime sustainable food advocate Gwen Schantz, Brooklyn Grange grows over 50,000 pounds of produce per year in over 87K SF on two rooftops, one in Brooklyn and one in Queens. The Brooklyn Grange education program brings 17,000 New York City youths each season for tours through their farms. The organization is supported by a produce share program in which members subscribe to weekly deliveries of fresh produce. The farm grows a variety of produce, including from salad greens, mix herbs, eggplants, chard, carrots, peppers and flowers.

Square Roots Location: 630 Flushing Ave., Sumner Houses Square Roots operates vertical farms from shipping containers. Specializing in greens and herbs, the indoor growing process allows for year-round growing using 80% less water from traditional outdoor farms. Like Brooklyn Grange, Square Roots is funded by a food-share program where members can buy in $7, $15 and $35 per week packages. The working collective also has an active, year-round events business.

Urban Farming Insider: Understanding Organic Hydroponics With Tinia Pina

Tinia Pina is the founder and CEO of Renuble, a company started in 2011 that develops hydroponic fertilizer 100% derived from organic food waste inputs.