Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Self-Sustaining Islands, the Future of Farming?

As nautical ways of living catch on, triple decker farms might start supplying a region near you.

Charlie Stephens

The future of oceanic farming is being shaped by a group of Spanish designers. Smart Floating Farms is a floating island of fish farms, hydroponic gardens and solar panels – all of which will help future farmers bypass the inefficiencies of traditional agriculture.

Created by Barcelona design firm Forward Thinking Architecture, Smart Floating Farms (SFF) are modular, self-regulating, and multi-dimensional ocean barges. The 656 x 1,150 ft. rectangular plots provide 2.2 million square feet of farming space, and can be linked or separated according to what is needed.

The main bottom is made up of a fish farm and slaughterhouse, which are maintained by manual labor and an encompassing wave protector. The bottom floor also holds the main storage facility and desalination plant for the hydroponic farm on the story above.

Since hydroponically grown food doesn’t need soil, the floating farm makes practical sense. Production management becomes simplified as well – data is collected from the aeroponic walls and processed through an IoT system that regulates growing conditions such as climate, and eliminates the need for harmful pesticides.

The result is a self-sustaining cycle where waste from the second floor can be used as food for the first, and vice versa. Energy for the farm is sourced from the third story, where high-energy photovoltaic panels and skylights would be located.

Like the designers behind Smart Floating Farms, other entrepreneurs are venturing into unchartered waters. Blueseed is a vision for an ocean-based community of entrepreneurs who live together on an anchored ship, working and creating alongside one another in a collaborative system. While SFF could be floated offshore to any country around the world, Blueseed offers working permits for people regardless of their home citizenship.

We are also seeing new uses of shipping containers, both as living spaces in cities and also as urban farms on college campuses. Traditionally, ships have needed to be compact and efficient to get from place to place, and this maritime model of living and producing appears to be transversing industrial boundaries.

While SFF is not a ship in the exact sense, the idea is still the same – the way we work is being affected by our environmental resources. As we try to bring food production to underserved areas and seek space for making this possible, methods of production are literally changing form.

The vast expanses of rural farms are being supplanted by the vertical farming, and hydroponics are constantly being improved and adapted around the world in place of soil-dependent techniques. Now, food can be brought from farm to table in just four hours, and unused urban spaces are being transformed into agricultural powerhouses.

Smart Floating Farms is yet another one of these innovative models for producing and delivering fresh, abundant food to areas in need around the globe.

This New Site Seeks to Strengthen the Boston Food Industry

The way Branchfood sees it, Boston has the potential to be one of the strongest food systems in the country. Already, Branchfood boasts info on more than 150 local producers, distributors, advocacy groups, funders, startups and composters.

This New Site Seeks to Strengthen the Boston Food Industry

Already, Branchfood boasts info on more than 150 local producers, distributors, advocacy groups, funders, startups and composters.

Rebecca Strong - Staff Writer

8/20/15 @11:21am in Tech

"Eat local."

It’s a phrase we’ve been hearing more and more in recent years, as awareness rises around the nutritional benefits of consuming produce that hasn’t traveled thousands of miles and interest in supporting the local agriculture economy increases. Now, there’s even a term for the people who practice this motto: locavores, who tend only to consume food grown within about 100 miles of its point of purchase. Branchfood launched in 2013 as a platform to promote local food innovation, while connecting like-minded people to share their growth-stage food product and food tech companies. The coworking and events startup, which is based at the CIC on Milk Street, recently realized the lack of a go-to source for learning more about the local food ecosystem—so they decided to build one.

Empowering the industry with information

Lauren Abda

Founder Lauren Abda says her inspiration for the Boston Food Network was this Techscene map. The idea was to aggregate information about all the various entities that make up Boston’s food scene, and bring all that data online so that it’s easily accessible and searchable. Currently, the site includes information about over 150 local food producers, distributors, advocacy groups, funders, startups, composters and more. And it’s already receiving national recognition: The Boston Food Network will be featured at the upcoming International Economic Development Council’s annual conference in Anchorage, Alaska—the world's largest annual gathering of economic developers. This new initiative will also be a topic of conversation at the upcoming Branchfood Community Table gathering Sept. 3.

Abda noted that the site will serve a wide range of people in the Boston community, bringing consumer awareness to local businesses while simultaneously helping those who value local food find out about local players.

“It’s the only site where one can gain a holistic understanding of the local food ecosystem,” she said.

For example, the Support Network section will give entrepreneurs an avenue for finding food focused venture funds, consulting services, or potential business partners. Consumers looking to find locally grown producer will find links to existing resources on farms, farmer’s markets and CSAs serving the Greater Boston area. Busy professionals, meanwhile, have access to a list of food/beverage delivery services on the site, and CPG companies can locate farmers markets and retail outlets that may be interested to carry their products. Chefs, of course, will reap rewards from the resource as well: They can use it to find catering companies to work with, as well as food waste and food recovery organizations available for food pickup or drop off.

The way Branchfood sees it, Boston has the potential to be one of the strongest food systems in the country.

“The strength lies at the intersection of Boston’s proximity to local food from New England farms, patronage for supporting local, and emerging entrepreneurial initiatives dedicated to improving access, cost, health, taste, and distance to our food,” explained Abda.

But in order to get there, it will be crucial for more people in the Boston food industry to connect and collaborate—which is where the new site comes in.

Boosting the network's value

During the first stage of pulling this together, Abda says her team received feedback from about 10 local food experts, enthusiasts, and Web design/development specialists on how to improve it. They are aiming to add more functionality in the future, including sorting and filtering entries, featuring new companies and organizations that want to increase their visibility, and providing further information on each organization such business partnerships or how long they have been active. Down the road, they’re also looking at incorporate this resource organically within other existing databases, like the data available on the City of Boston Office of Food Initiatives website.

Above all, Abda emphasized that The Boston Food Network is an evolving resource. Anyone can submit suggestions to add to these lists of food startups, producers, incubators, funders and distributors. She added that Branchfood is also considering ways to incorporate suggestions a la Wikipedia, with users submitting content edits, and Branchfood reviewing/approving. Already, they’ve added Local Food Jobs section based solely on initial feedback.

“We want this resource to continue to grow and be molded by community feedback and suggestions,” she told BostInno. “This is version 1.0.”

A top priority right now, according to Abda, is working with entities like the Office of Food Initiatives to find the best ways to make this information as easily available to the public and the area's stakeholders as possible, while simultaneously enhancing the technical aspects of the site for improved user experience and interest.

Vertical Farming: What Is It, And What’s Fueling Its Growth?

80% of the earth’s population will live in urban areas by the year 2050.

Vertical farming, or urban farming, is becoming more prevalent in the agribusiness sector. Experts predict that almost 80% of the earth’s population will live in urban areas by the year 2050, so developing and maintaining sustainable supplies of fresh food in large cities is increasingly important–and profitable.

By cultivating plants inside a skyscraper greenhouse, utilizing natural sunlight and artificial lighting, vertical farmers are able to produce fresh food while minimizing land usage and transportation costs. Droughts, floods and other weather-related issues are a thing of the past, and a controlled indoor climate carefully regulates ideal growing conditions year-round.

Curious about opportunities in vertical farming? Here are 10 things you need to know about this growing industry.

History of Vertical Farming

1. Vertical farming is regarded as a fairly new concept, but the idea has been around for a long time. In 1915, American geologist Gilbert Ellis Bailey wrote a book called Vertical Farming, and while it mostly dealt with using particular types of soils to grow crops, the idea for today’s vertical farm was born from his theory.

2. The first practical example of a vertical farm dates back to the 1950s, with an attempt at growing cress indoors at a large scale.

3. In 1999, students in a university classroom were discussing the idea of rooftop farming to produce rice. Dr. Dickson Despommier then took the discussion to the next level: what if crops were grown inside buildings?

How Vertical Farming Works

4. Using Manhattan as an example, Dr. Despommier’s class estimated that one 30-story vertical farm could produce enough food for more than 50,000 people, and 160 such farms could feed the entirety of New York City.

5. The plants that thrive best in vertical farms are nutritious types of produce, like green veggies and tomatoes. Crops like wheat and rice will be more difficult to grow in a vertical farming environment because of the amount of biomass required for them to thrive.

6. Vertically farmed crops can be grown hydroponically or aquaponically (in water) or aeroponically (in the air), without any soil. The biggest need is for a light source throughout the farm. Typically, prototype vertical farms use a combination of natural and artificial light for photosynthesis.

7. Because vertically farmed crops are produced indoors, in a controlled environment, people would have access to locally grown fresh produce year round – no need to purchase imported fruits and vegetables or prepared or frozen foods during the winter months, when those crops typically aren’t in season.

8. Another benefit to vertical farming? Produce grown indoors is organic and chemical-free, as no herbicides or pesticides are required.

The Future of Vertical Farming

9. By 2050, the world’s population is estimated to swell to 9 billion people, and experts guestimate that 80 percent of them will reside in urban areas. As the population grows, there will be less land mass available for farmland and growing food.

10. The world’s largest vertical farm is scheduled to open in Newark, NJ, this year. Set up in an old steel factory, it’s estimated to be 75 times more productive than a traditional farm of a similar size, and it requires no soil and 95 percent less water.

USA Subterranean Farm

About two years ago, before I was really ready, I proposed the development of a subterranean indoor farm in a major metropolitan area in the mid-western United States

USA Subterranean Farm

- Published on July 6, 2015

Glenn Behrman

FollowingUnfollowGlenn Behrman

CEA Advisors,GreenTech Agro LLC, Developers of The Growtainer™ & Growrack™. Indoor Farming Experienced Professional

About two years ago, before I was really ready, I proposed the development of a subterranean indoor farm in a major metropolitan area in the mid-western United States.With a population of 2.75 million, access to four major highways and a food deficit over 2 billion dollars per year, this was and still is an excellent opportunity.

Although I've been in the horticulture industry for almost 45 years, two years ago I was still connecting the dots and certainly didn't know then what I know now about indoor farming, controlled environment agriculture and technology based production but my proposal was well received by the local and state government officials that I came in contact with and they were behind the project 100%. The city and state offered substantial assistance, including access to various economic incentives, a preferred "local grown" purchasing initiative and assistance with developing strategic relationships with C level executives at local Fortune 500 businesses, local hospitals and universities, non-profits, schools, etc.

Since that time I've developed and nurtured relationships with the right people, further evaluated the site that I have in mind, met with the leasing people and found a subterranean site that is affordable, has a great infrastructure in place and is guaranteed to be front page news for a number of reasons.

Fast forward to today: Now I've spent the past four years laser focused on indoor farming, learning a lot from a lot of really qualified people. I've designed, built and operate two successful container based indoor farms, picked the brains of the most knowledgeable people in the industry, established a network of experts in every necessary component and facet of indoor production, spent 1000's of hours focused on site design, automation, production, technology and economics and now I'm ready to pull the trigger on the development of the most unique state of the art indoor farm in the world.

Fast Forward to November 2016. I'll be in Kansas City next week for the kick off of this fantastic project. Watch as it unfolds.... gb@cea-advisors.com

Five Vertical Farms that Capture the Imagination and Profit

Vertical farms: the idea captures our imagination.

May 17, 2015 | Rose Egelhoff

Vertical farms: the idea captures our imagination. We envision their upward-twisting frames nestled between the steel and chrome skyscrapers of the big city. Each floor overflows with fruits and vegetables brought to life by hydroponic or aquaponic growing systems, bringing local food and a breath of fresh air to cities with a footprint smaller than any “horizontal” farm.

Harvesters Alejandra Martinez (front), Steve Rodriguez, and Marquita Twidell cut basil grown in an aquaponic system at FarmedHere, a vertical farming operation based in Bedford Park, Illinois. Image courtesy of FarmedHere.

While setup and electrical costs remain expensive, a wave of vertical farmers around the world has been finding new ways to cut costs and streamline systems to make vertical farming a reality. They may not be ‘farmscrapers’, but these five vertical farms achieve production rates up to 100 times more efficient per square foot than traditional farming while bringing year-round local produce to their communities.

FarmedHere

FarmedHere’s huge, 90,000 square foot facility features an aquaponic setup lit by specially designed magenta and blue LEDs, developed through a partnership with the LED lighting manufacturer Illumitex, Inc. The lights emit only the frequencies of light that plants utilize, reducing energy costs. Roots dangle in trays of water fertilized with waste from tanks of tilapia and closed, soil-free systems minimize exposure to pests and disease, making their organic certification an easy achievement.

FarmedHere grows microgreens, basil and mint—staple crops for vertical farmers because they can be ready in as little as 14 days (that’s 26 harvests every year!). They sell to the big names, including more than 50 Whole Foods Markets and many other Chicago grocery stores.

This Singapore farming company exemplifies the potential for vertical farming to thrive in urban spaces. Real estate prices are sky-high on the densely-populated island, and access to fresh food is limited. Singapore imports most of its produce from China, Malaysia or the U.S.

Jack Ng saw the potential demand for fresh, local produce and created Sky Farms. He designed a growing system called A-Go-Gro. Thirty-foot A-frame towers rotate plant troughs up and down on a hydraulically powered belt to provide equal exposure to sunlight. Though Sky Greens grows hydroponically, these systems can also be adapted to soil growing.

Sky Greens currently produce ten varieties of greens including bok choi, lettuce, kang kong (water spinach) and bayam (amaranth). The product ends up costing about 10% more than imported greens but according to Permaculture News, Sky Greens’ extra- fresh veggies are “flying off the shelves.”

Another Chicago enterprise, the Plant describes itself as “part vertical farm, part food business incubator, part research and education space.”

Ten local food businesses, including several vertical farming operations, a sustainable prawn grower and a bakery, are located inside The Plant. The building is an abandoned pork packing facility in Chicago’s Back of the Yards neighborhood, retrofitted by crews of volunteers to fit the needs of local food producers. One business uses the roof space for good old soil farming while indoor operations employ hydroponics and artificial light. Plans for a shared kitchen are in the works, and The Plant eventually hopes to achieve net-zero energy use by harvesting biogas from their anaerobic digester, eliminating the high electricity costs that plague vertical farmers.

In Japan, the aftermath of the Fukushima crisis left in its wake both abandoned buildings and farmland devastated by radioactive contamination. Vertical farms like Mirai (“future” in Japanese) helped replace the lost food production capacity. Shigeharu Shimamuru, plant physiologist and president of Mirai, collaborated with GE Japan to design a state-of-the-art LED hydroponic system with carefully controlled wavelengths and dark periods. This means plants can photosynthesize at maximum capacity during the day and rest or “breathe” at night.

The combination makes for both fast-growing plants, and efficient resource use. Compared to conventional farming, the setup cuts produce waste by 50 percent, reduces water use by 99 percent and is 100 times more productive per square foot. The system operates in 12 locations around Japan, including a 25,000 square foot farm in the Miyagi prefecture just north of Fukushima, which can produce 10,000 heads of lettuce a day at full capacity. Mirai has recently begun another project in Korea.

Instead of growing in water, Aerofarms takes things another step away from conventional soil farming and grows plants in the air. Seeds germinate in a reusable fabric layer and suspended in stacked trays. The roots are sprayed with water and nutrients and LED lights fuel photosynthesis. Ed Harwood, a former Cornell professor who founded Aerofarms with his partners Marc Oshima and David Rosenberg in 2004, designed the system.

Aerofarms started off producing greens and herbs for farmers’ markets in upstate New York, including the prestigious Ithaca Farmers’ Market. They also sell their technology to other indoor farmers. Though not yet profitable, they are planning to expand. The project: a 69,000 square foot custom-built vertical farm in Newark, NJ. The $39 million development project, which is scheduled for completion in 2016, is being financed primarily by Goldman Sachs’ Urban Investment Group. Additional funds from Prudential Financial and the city of Newark supplement Goldman Sachs’ investment.

5 Ways Vertical Farms Are Changing the Way We Grow Food

No soil? No problem. Vertical farms are sprouting around the world.

No soil? No problem. From Japan to Jackson, Wyoming, plucking fresh lettuce is as easy as looking up. Vertical farms have been sprouting around the world, growing crops in places where traditional agriculture would have been impossible.

Vertical farms are multiple stories, often have a hydroponic system and some contain artificial lights to mimic the sun. These green hubs are attractive in a variety of ways since food can be produced with less water (since it just recirculates), creates less waste and takes up less space than traditional farming, ultimately leaving a smaller footprint on the environment.

Additionally, the United Nations projects that the world's population will reach 9.6 billion people by 2050, 86 percent of whom will live in cities. For swelling cities, these urban farms give city dwellers greater access to fresh, nutritious food-year round, reducing the distance it has to travel to get to forks. Here are five more reaons why the sky's the limit with vertical farms.

1. Vertical farms can defy any weather: In perpetually wintry Jackson, Wyoming, residents will soon be able to find fresh tomatoes, lettuce and other produce that's not hauled in by delivery trucks. The Vertical Harvest farm is a three-story 13,500 square foot hydroponic greenhouse that will sit on a mere 30 by 150-foot plot adjacent to a parking lot. Utilizing both natural and artificial lighting (especially since the area is blanketed in snow most of the year), three stories of plant trays will revolve inside the building as well as the ceiling in a carousel-like system to maximize light exposure. The company aims to supply 100,000 pounds of year-round produce that's pesticide-free, and will use 90 percent less water than conventional farming because it recycles its water.

Construction of the $3.7 million greenhouse kicked off last November and has already pre sold crops to restaurants, grocery stores and a hospital. In the video below, E/Ye Design architects and Vertical Harvest co-founders Penny McBride and Nona Yehia talk about their innovative building and their mission to hire adults with developmental disabilities to spur local employment.

2. Vertical farms are a great response to climate change: Urban farming has been touted by many as a solution to increasingly extreme weather caused by warmer global temperatures. In very parched California, the Ouroboros Farms in Pescadero employs an unusual group of farmers: Catfish. The farm uses an "aquaponics" system, where 800 catfish swim and dine on organic feed, and as they create waste, the crops above suck up this nitrogen-rich fertilizer. All this means no soil, pesticides or other toxins are required for the stunning variety of vegetables that are produced at the farm, from spicy greens to root vegetables. In case you're wondering, nothing goes to waste; these fish are also sold as food. The farm also saves 90 percent less water than traditional farming.

"I honestly believe [aquaponics] is the evolution of farming," Ken Armstrong, the founder of Ouroboros Farms, said in the video below, "because of its ability to grow faster and more densely with fewer resources it will be the methodology of growing in the future."

3. Vertical farms adapt to disaster: We previously featured Japanese plant physiologist Shigeharu Shimamura, who converted an abandoned, semiconductor factory into the world’s biggest indoor farm, Mirai. Shimamura built the farm in 2011 in response to the food shortages caused by the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami that devastated Japan, and sparked the Fukushima nuclear disaster which irradiated much of the region's farmland.

At 25,000 square feet, the farm can yield up to 10,000 heads of lettuce a day. That’s 100 times more per square foot than traditional methods, and uses 99 percent less water usage than outdoor fields.

A press release said that the building is powered by special General Electric LEDs that “generate light in wavelengths adapted to plant growth. While reducing electric power consumption by 40 percent compared to fluorescent lighting, the facility has succeeded in increasing harvest yields by 50 percent,” and meant that Mirai was able to offset the cost of pricy LEDs. Watch how it all works:

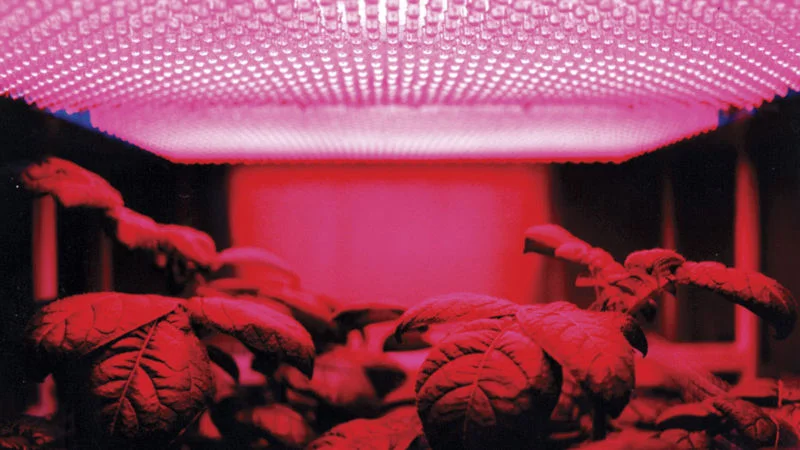

4. Vertical farms are becoming more advanced: It's only the beginning for vertical farms in terms of technology. At the New Buffalo, Michigan branch of Green Spirit Farms, some plants grow under pink-tinted LED lights which "provide the correct blue and red wavelengths for photosynthesis," according to Harbor Country News. It's so efficient, the farm can currently grow 10 tons of lettuce in only 500 square feet of space. Green Spirit Farms president Milan Kluko also told New Scientist that he and his colleagues are developing a smartphone or tablet app that can adjust nutrient levels or soil pH balance, or sound an alarm when a water pump is malfunctioning, for example. "So if I'm over in London, where we're looking for a future vertical farm site to serve restaurants, I'll still be able to adjust the process in Michigan or Pennsylvania," he said.

Farm Manager Mike Kennedy making sure our fresh & local veggies (kale) are on the right time zone - they are now! pic.twitter.com/V4sNEzd6HR— Green Spirit Farms (@greenspiritfarm) March 8, 2015

5. Vertical farms are saving lives: Vertical farms are being used beyond food. In fact, they're being used to aid human health. Caliber Biotherapeutics in Bryan, Texas is home to the world's largest plant-made pharmaceutical facility. This 18-story, 150,000 square foot facility contains a staggering 2.2 million tobacco-like plants stacked 50-feet high, that will be used for making new drugs and vaccines. Because the indoor farm is so carefully monitored and tightly controlled by technicians, these expensive plants are shielded from possible diseases and contamination from the outside world.

Barry Holtz, the CEO of Caliber, told NPR that the facility is also efficient when it comes to water and electricity: "We've done some calculations, and we lose less water in one day than a KFC restaurant uses, because we recycle all of it."

Plants at Caliber Biotherapeutics grow in a "pink house" under blue and red LED lights. The tobacco-like plants will be used for making new drugs and vaccines. Photo Credit: Caliber Biotherapeutics

This vertical farm will provide Wyoming residents with 100,000 lbs of fresh produce each year

Not only will the Vertical Harvest provide fresh produce for Jackson, it will also serve as an educational facility, with a “small but functional ‘living classroom’” and access for visitors to view the growing areas without contaminating the crops

A 30 foot by 150 foot sliver of land located next to a parking lot in Jackson, Wyoming is set to be transformed into a vertical farm that will produce up to 100,000 lbs of produce each year. Using 90 percent less water than conventional farming, and absolutely no pesticides, the three-story Vertical Harvest greenhouse will enable the cold, land-locked city to provide locally-grown produce for its residents all year round.

The Vertical Harvest farm is designed by E/Ye Design and utilizes a 30 by 150-foot plot of unused city land that sits next to a parking lot in Jackson, Wyoming. Through an efficient building design, and the use of hydroponic farming techniques, the 4,500 sq ft footprint will have 18,000 sq ft of growing area. Within this area, the farm will produce over 37,000 pounds of greens, 4,400 pounds of herbs, and 44,000 pounds of tomatoes.

This is a significant amount of fresh produce for the town of 9,577, and provides residents with a locally-grown alternative thatJackson’s climate previously prevented. Located one mile above sea level, the town is blanketed in snow for months on end, and is therefore forced to import much of its food. In addition, the developers behind the farm have been careful to plan to grow only produce that is currently imported—thereby not competing with local farms, but rather bolstering local businesses by saving on transportation costs.

The 150-foot-long greenhouse facade of the building optimizes the potential for natural light, which both improves photosynthesis and cuts down on energy costs for the facility. There will be times when artificial light is required—for instance, it is impossible to grow tomatoes during a frozen winter on natural light alone—and so grow lights will be installed in order to ensure that the farm meets production goals.

Although the grow lights will require a certain amount of energy, Vertical Harvest founders Nona Yehia and Penny McBride have stated that it still constitutes net energy savings over imported produce, and while HPS (High Pressure Sodium) bulbs will be used for the tomatoes, LEDs will be utilized for the “lettuce varietals, microgreen and propagation areas.”

Not only will the Vertical Harvest provide fresh produce for Jackson, it will also serve as an educational facility, with a “small but functional ‘living classroom’” and access for visitors to view the growing areas without contaminating the crops. Vertical Harvest recently broke ground, and growing will commence later this year.

Vertical farms: "Making Nature Better"

The entire operation is indoors, and it's a trend that could turn urban areas into agricultural hotbed

By DEAN REYNOLDS CBS NEWS December 27, 2014, 7:04 PM

Vertical farms: "Making Nature Better"

- PORTAGE, Indiana -- Do not be confused by the drab facade of the warehouse in this Northwest Indiana industrial park. It's a farm... and it could well be the future. They're called "vertical farms" -- The entire operation is indoors, and it's a trend that could turn urban areas into agricultural hotbeds.

You'll find arugula and parsley, basil, kale and other greens that grace our plates.

"We are growing nine varieties of lettuces,'' said Robert Colangelo, the founder of Green Sense Farms.

Or you could call him Mr. Salad.

"I guess. I'll take that. I could be called worse," says Colangelo.

This is how he does it, with a pink light from a light-emitting diode, or LED

"It gives you a very concentrated amount of light and burns much cooler. And it's much more energy efficient," says Colangelo.

No sun? No problem.

Researchers believe plants respond best to the blue and red colors of the spectrum, so the densely-packed plants are bathed in a pink and purple haze. They're moistened by recycled water; bolstered by nutrients; and anchored in a special mix of ground Sri Lankan coconut husks.

"We take weather out of the equation," says Colangelo. "We can grow year round and we can harvest year-round."

This abundance keeps the prices consistent year-round at local groceries.

Scott Hinkle, a local chef, says the sunless harvest tastes great. Hinkle shows off a "blossom salad" he serves which can include watercress, micro-arugula or kale.

With less water and fertilizer, fewer workers and no gasoline, it's more economical to grow greens this way than on a traditional farm.

Since there are no bugs, there's no need for pesticides. No weeds, so no need for herbicides.

And Colangelo really knows his plants. He says workers play classical music to create happy vibes for the flora.

Is there a composer the plants prefer? If it's Metallica, we don't want to eat it.

As to whether he's cheating nature...

"We're making nature better," says Colangelo.

There's no need for insecticides or herbicides inside the warehouse.

CBS NEWS

© 2014 CBS Interactive Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Landmark 20-Year Study Finds Pesticides Linked to Depression In Farmers

A landmark study indicates that seven pesticides, some widely used, may be causing clinical depression in farmers. Will the government step in and start regulating these chemical tools?

Landmark 20-Year Study Finds Pesticides Linked to Depression In Farmers

By Dan Nosowitz on November 7, 2014

A landmark study indicates that seven pesticides, some widely used, may be causing clinical depression in farmers. Will the government step in and start regulating these chemical tools?

Earlier this fall, researchers from the National Institute of Health finished up a landmark 20-year study, a study that hasn’t received the amount of coverage it deserves. About 84,000 farmers and spouses of farmers were interviewed since the mid-1990s to investigate the connection between pesticides and depression, a connection that had been suggested through anecdotal evidence for far longer. We called up Dr. Freya Kamel, the lead researcher on the study, to find out what the team learned and what it all means. Spoiler: nothing good.

“There had been scattered reports in the literature that pesticides were associated with depression,” says Kamel. “We wanted to do a new study because we had more detailed data than most people have access to.” That excessive amount of data includes tens of thousands of farmers, with specific information about which pesticides they were using and whether they had sought treatment for a variety of health problems, from pesticide poisoning to depression. Farmers were surveyed multiple times throughout the 20-year period, which gives the researchers an insight into their health over time that no other study has.

“I don’t think there’s anything surprising about the fact that pesticides would affect neurologic function.”

Because the data is so excessive, the researchers have mined it three times so far, the most recent time in a study published just this fall. The first one was concerned with suicide, the second with depression amongst the spouses of farmers (Kamel says “pesticide applicators,” but most of the people applying pesticides are farmers), and the most recent with depression amongst the farmers themselves.

There’s a significant correlation between pesticide use and depression, that much is very clear, but not all pesticides. The two types that Kamel says reliably moved the needle on depression are organochlorine insecticides and fumigants, which increase the farmer’s risk of depression by a whopping 90% and 80%, respectively. The study lays out the seven specific pesticides, falling generally into one of those two categories, that demonstrated a categorically reliable correlation to increased risk of depression.

These types aren’t necessarily uncommon, either; one, called malathion, was used by 67% of the tens of thousands of farmers surveyed. Malathion is banned in Europe, for what that’s worth.

I asked whether farmers were likely to simply have higher levels of depression than the norm, given the difficulties of the job — long hours, low wages, a lack of power due to government interference, that kind of thing — and, according to Kamel, that wasn’t a problem at all. “We didn’t have to deal with overreporting [of depression] because we weren’t seeing that,” she says. In fact, only 8% of farmers surveyed sought treatment for depression, lower than the norm, which is somewhere around 10% in this country. That doesn’t mean farmers are less likely to suffer from depression, only that they’re less likely to seek treatment for it, and that makes the findings, if anything, even stronger.

The study doesn’t really deal with exactly how the pesticides are affecting the farmers. Insecticides are designed to disrupt the way nerves work, sometimes inhibiting specific enzymes or the way nerve membranes work, that kind of thing. It’s pretty complicated, and nobody’s quite sure where depression fits in. “How this ultimately leads to depression, I don’t know that anyone can really fill in the dots there,” says Kamel. But essentially, the pesticides are designed to mess with the nerves of insects, and in certain aspects, our own nervous systems are similar enough to those of insects that we could be affected, too. “I don’t think there’s anything surprising about the fact that pesticides would affect neurologic function,” says Kamel, flatly.

Kamel speaks slowly and precisely, and though her voice is naturally a little quavery, she answered questions confidently and at one point made fun of me a little for a mischaracterization I’d made in a question. The one time she hesitated was when I asked what she thought the result of the study should be; it’s a huge deal, finding out that commonly used pesticides, pesticides approved for use by our own government, are wreaking havoc on the neurological systems of farmers. Kamel doesn’t recommend policy; she’s a scientist and would only go so far as to suggest that we should cut down on the use of pesticides in general.

Others are going further. Melanie Forti, of a farmer advocacy group based in DC, told Vice, “There should be more regulations on the type of pesticides being used.” With any luck, this study will lead to a thorough reexamination of the chemical weapons allowed by farmers.

This Vertical Farm Skyscraper May Change Our Cities Forever

The Hive-Inn farm would seriously re-vamp the way urbanites eat, by providing very local produce

The Hive-Inn farm would seriously re-vamp the way urbanites eat, by providing very local produce.

Imagine a future where you could pick fresh produce in downtown Manhattan just by visiting a vertical farm right down the block, or where restaurants could use local ingredients from that same quirky-looking farm skyscraper. That future may be nearer than you think. Meet the Hive-Inn farm by OVA Studio in Hong Kong, a concept that is still just in sketch form, but could be changing the way urbanites eat as soon as the next several years.

The Hive-Inn farm resembles a small skyscraper, and is essentially a vertical farm made up of individual containers, or farming modules. Each unit would play a role either in producing food, harvesting energy from the sun and rain, or recycling waste. Essentially, the whole “green building” would be a living ecosystem. The Hive-Inn farm would produce fruits and vegetables that could be used by downtown Manhattan residents and businesses.

See More Urban Farming News

- World’s First Underground Farm to Open This Fall in London

- Explorations in Urban Farming

- The Case for Connection: Urban Farming Takes Root in Upper West Chicago

- Urban Farming Takes Off in Tokyo

- Changing Lives – Urban Farmers of Nairobi

We spoke with Slimane Ouahes, the director at OVA Studio about the future of the project, and what it could mean for New York. Right now, he said, OVA does not have a client, and the idea is still in the planning stages.

“As [the farm] is local, there is nothing to hide, you can see your food growing, rebuild trust between the food production and your appetite, and it will be an attraction for visitors,” explained Ouahes. “Local restaurants would also produce their veggies in these containers and have much more control over the quality.”

Indoor Farm Taps Technology To Grow Leafy Greens

The indoor operation consists of 10 individual farms, each about the size of a parking space that a Toyota Prius would occupy

Drawing from his background as an electrical engineer, Steve Fambro, founder and chief executive officer of Oceanside, Calif.-based Famgro Farms, has tried to eliminate as much variability in leafy green production as possible.

Steve Fambro has drawn from his electrical engineering background to take a systems approach to producing leafy greens indoors

The result is an indoor technological platform that optimizes crop production by trying to provide all of the plants’ needs in terms of lighting, nutrition, humidity, air flow and moisture.

“It uses hydroponics that we have developed and patented and it uses LEDs that we manufacture and patented, but those are just parts of the story,” Fambro said. “I don’t consider this vertical farming. Our goal is so much more.”

Instead, he thinks of it as a systems approach that meshes with his personal philosophy of providing affordable, locally grown produce.

The indoor operation consists of 10 individual farms, each about the size of a parking space that a Toyota Prius would occupy. Together, they produce leafy green yields equivalent to those from 5 to 10 acres of open fields, Fambro said.

The farm grows myriad leafy greens, ranging from its signature sweet kale to microgreens and herbs.

The kale, marketed under Famgro Farms' own label, is touted as having a buttery texture that eats more like lettuce.

“It’s not unlike Kobe beef,” Fambro said of its tenderness.

Although the operation does produce kale microgreens, its forte is full-grown leaves.

“The reason for that is chefs like the savoy, bumpy leaves and they can plate it in different ways,” he said.

For each crop, the company has developed a specific production system that caters to that plant’s individual needs.

The kale crop, for example, spends just 15 days as seedlings and another 15 days in the farm under intense lighting before harvest.

All of the crops are grown in an enclosed building designed to exclude insects, weeds and diseases. Sanitary procedures along the way help to minimize pathogens.

As a result, Fambro said they don’t use any pesticides.

In addition, he uses no animal-based nutrients.

Under the National Organic Program, producers can use 37 different pesticides, bone meal, fish emulsions and manure-based composts while maintaining their organic certification.

Famgro’s crops are not certified organic, partly because portions of the program conflict with his philosophy and partly because of food safety concerns.

Take fish emulsions, for example.

“We have no idea if it’s old-growth fish that are brimming with mercury,” he said. “There are no standards of any kind of how those fish are acquired or rendered into fish emulsions.”

Using animal-based products also introduces a second life form into the plant production system, complicating food safety, Fambro said.

In addition, using a vegan-based production system allows the company to market to consumers who for personal or religious reasons oppose killing animals.

As with every crop grown, each step along the way is entered into the computer and tied to a batch number. Not only does this provide for traceability, but it also allows the operation to improve the growing process, Fambro said.

If a propagator, for example, isn’t doing his or her job and yields suffer, the cause can be traced back.

Having all of the data at the touch of a computer also allows the company to schedule production just in time to meet customers’ orders.

Famgro sells to individual local retailers, Whole Foods in Southern California and foodservice as well as through wholesaler LA & SF Specialty, Los Angeles

14 High-Tech Farms Where Veggies Grow Indoors

Farming is moving indoors!

In the 21st century, a significant change is underway in the food industry: farming is moving indoors. The perfect crop field could be inside a windowless building with controlled light, temperature, humidity, air quality and nutrition. It could be in the basement of a Tokyo high-rise, in an old warehouse in Illinois, or even in space. Just look at our collection of awesome indoor farms, where the sun never shines, the rainfall is irrelevant, and the climate is always perfect.

Basil, arugula and microgreens.

A worker checks crops at the FarmedHere indoor vertical farm, in Bedford Park, Illinois, on February 20, 2013. The farm, in an old warehouse, has crops that include basil, arugula and microgreens, sold at grocery stores in Chicago and its suburbs.

Photo: Heather Aitken/AP

Your endive grows in total darkness.

Red endives at the California Vegetable Specialties indoor farm in Rio Vista, California (April 20, 2006). The growing process is long and fragile, with the endives' roots grown outside first and then moved in, where they are left for up to 11 months to grow into mature endives in total darkness.

Photo: Jeff Chiu/AP

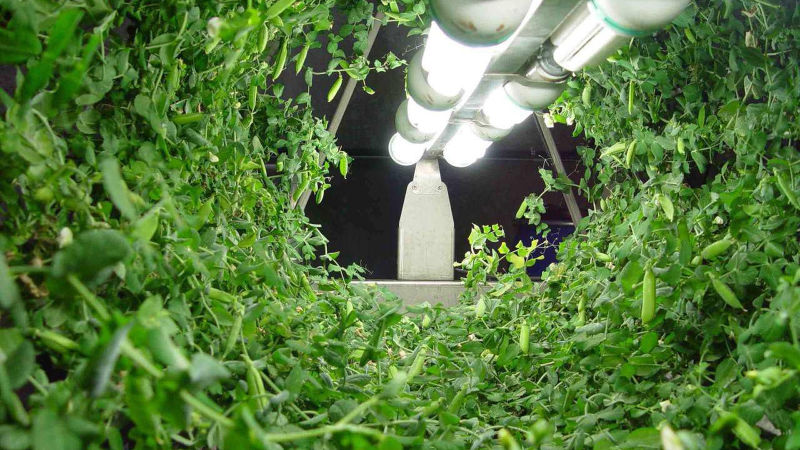

Under fluorescent lights.

Toshihiro Sakuma checks the condition of plants under fluorescent lights at a greenhouse built inside a Tokyo building on July 1, 2005.

Photo: Shizuo Kambayashi/AP

Sunless farming.

Fittonia plants are seen as they grow in a special darkened room illuminated by blue and red LEDs at PlantLab, a private research facility, in Den Bosch, central Netherlands, March 28, 2011.

Photo: Peter Dejong/AP

Medical cannabis growing operation.

This facility can be found in Oakland, California. The electricity bill is over $4,000/month.

Illegal cannabis growing operation.

This indoor marijuana farm in California was raided by police.

Photo: Arcata Police Department/AP

Legal cannabis growing operation.

In the Netherlands it was legal to grow hemp for a long time. This is what cultivating the world’s finest indoor marijuana looked like a few years ago.

Photo: World Of Seeds

Japanese indoor greenhouse.

Flowers grow under fluorescent lights in greehouse named "Pasona O2" in the basement of a highrise office building in Tokyo. The new style of greenhouse, built by the human resources service company Pasona Inc. in 2005 at the center of Tokyo's business district, is a facility to train aspiring farmers with high-tech methods involving hydroponics and light-emitting diodes (LED).

Photo: Yohei Yamashita

Rice plants at an indoor paddy field in "Pasona O2". Pasona hopes this greenhouse can help promote the pleasure of agriculture to businessmen and businesswomen, and inspire a new generation of farmers.

Photo: Yohei Yamashita

Tomatoes grown by hydroponics cultivation in "Pasona O2."

Photo: Katsumi Kasahara/Ap

A staff of "Pasona O2" checks vegetables grown under fluorescent lights.

Photo: Katsumi Kasahara/Ap

Hydroponics gardening for the masses.

"The Volksgarden brings simple, clean, and amazingly effective hydroponics gardening to the comforts of your own home," says the company Urban Led Growth. This unit allows to grow up to 80 plants at once. Herbs, vegetables, fruits, and grains can be harvested easily and continuously thanks to the rotating cylinder housing.

Photo: Urban Led Growth

Put an AeroGarden into your kitchen.

This dirt-free indoor garden planter uses aeroponics: vegetables, salad greens, herbs or flowers grow in this pod while being both slightly exposed to air and slightly submerged in the nutrient solution. The AeroGarden has built-in lights and a “Smart Garden” alert button to tell you when your plants need more nutrients or water.

Photo: timmycorkery

An automated, hydroponic, recirculating vertical farming unit.

This is one of the four indoor, climate controlled, automated, hydroponic, recirculating vertical farming units at Green Farms A&M. Green Farms Agronomics & Mycology is located in Valparaiso, Indiana, and was founded in the fall of 2010.

Photo: GreenFarms

Chicago urban garden.

The first "Aeroponic Garden at Any Airport in the World." In 2011, the CDA and HMS Host Corporation collaborated to install a garden in the mezzanine level of the O'Hare Rotunda Building. In this garden, plants' roots are suspended in 26 towers that house over 1,100 planting spots. A nutrient solution is regularly cycled through the towers using pumps so that no water evaporates or is wasted, making the process self-sustaining. No fertilizers or chemicals are used.

Photo: Gkkfea

Astroculture.

A view inside the "Astroculture" plant growth unit, during Space Shuttle mission STS-73, in 1995. Quantum Devices Inc., of Barneveld, Wisconsin, builds the light-emitting diodes used in medical devices and for growing plants, like potatoes, inside the plant growth unit developed for use on the Space Shuttle by the Wisconsin Center for Space Automation and Robotics (WCSAR). The astroculture facility has flown on eight Space Shuttle missions since, including this one in 1995 in which potatoes were grown in space.

Soybean growth aboard ISS.

Expedition Five crewmember and flight engineer Peggy Whitson displays the progress of soybeans growing in the Advanced Astroculture (ADVASC) Experiment aboard the International Space Station (ISS), in 2002. The ADVASC experiment was one of the several new experiments and science facilities delivered to the ISS by Expedition Five aboard the Space Shuttle Orbiter Endeavor STS-111 mission. An agricultural seed company will grow soybeans using the ADVASC hardware, to determine whether soybean plants can produce seeds in a microgravity environment. Secondary objectives include determination of the chemical characteristics of the seed in space and any microgravity impact on the plant growth cycle.

Top photo: Yellow peppers under blue and red Light Emitting Diode (LED) lights at PlantLab, a private research facility, in Den Bosch, central Netherlands, March 28, 2011. Photo: Peter Dejong/AP

By Attila Nagy

Vertical Farms: From Vision to Reality

Vertical farming: help feed the growing global population and undo the environmental damage caused by conventional agriculture.

Agriculture

Vertical farm designs by Chris Jacobs, Gordon Graff, SOA Architectes

(Updated October 17, 2011)

Dr. Dickson Despommier laughs when he recalls how crazy people thought he was just a few years ago. But Despommier, the most passionate proponent of vertical farming—the growing of crops indoors in multi-story urban buildings—is now seeing his vision being realized. He believes vertical farming can help feed the growing global population and undo the environmental damage caused by conventional agriculture.

“Farming has upset more ecological processes than anything else—it’s the most destructive process on earth,” Despommier told me. As of 2008, 37.7 percent of global land and 45 percent of U.S. land was used for agriculture. The encroachment of humans into wild land has resulted in the spread of infectious disease, the loss of biodiversity and the disruption of ecosystems. Over-cultivation and poor soil management has led to the degradation of global agricultural lands. The millions of tons of toxic pesticides used each year contaminate surface waters and groundwater, and endanger wildlife.

Agriculture is responsible for 15 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, and accounts for one-fifth of U.S. fossil fuel use, mainly to run farm equipment, transport food and produce fertilizer. As excess fertilizer washes into rivers, streams and oceans, it can cause eutrophication: Algae blooms proliferate; when they die, they are consumed by microbes, which use up all the oxygen in the water; the result is a dead zone that kills all aquatic life. As of 2008, there were 405 dead zones around the world.

More than two-thirds of the world’s fresh water is used for agriculture. And around the world, farmers are losing the battle for water for their crops as scarce water resources are increasingly being diverted to expanding cities. As climate change brings warmer temperatures and more droughts, the water crisis will worsen.

To feed the growing and increasingly urban global population of 9 billion expected by 2050, we need to boost food production by 70 percent through higher crop yields and expanded cultivation. The FAO estimates that we will need nearly 300 million more acres of arable land to do this, but most of the remaining arable land lies in developing countries, and many of the available land and water resources are currently providing other important ecosystem functions. Pressing them into service to produce food will upset many more of the planet’s ecosystems.

Dickson Despommier.

In 1999, while exploring the negative impacts of agriculture, Despommier, a professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, and 105 graduate students came up with the concept of the vertical farm—a multi-story building growing layers of crops on each floor. Vertical farm crops can be grown using hydroponics, where plants grow in water or a growing medium with nutrients delivered directly to their roots; aeroponics, which uses a mist to deliver nutrients to plant roots; aquaponics, when fish are raised concurrently and their waste is used as nutrients for crops; or even in soil if the building is designed accordingly.

At present, lettuce, leafy greens, herbs, strawberries and cucumbers are the most commonly grown crops in vertical farms, but in theory, corn and wheat could be grown, as well as biofuel crops and plants used to make drugs. Hydroponics use 70 percent less water than conventional agriculture; aeroponics use even less; and all water and nutrients not taken up by the plants are recycled.

LED lights. Photo credit: John Abela

Climate controls and LED lights programmed to deliver the wavelengths of light that plants prefer create optimum growing conditions. Methane generated from restaurant or crop waste can supply energy and heat for vertical farms.

As a balanced mini-ecosystem, the vertical farm has many advantages. A vertically farmed acre can produce the equivalent of 4 to 6 soil-based acres, depending on the crop (for strawberries, 1 vertical farm acre produces the same amount as 30 outdoor acres). Plants can be grown year-round, unaffected by weather conditions such as droughts, floods or pests. Vertically farmed food is safe from contamination(for example, from e-coli or radiation), and is grown sustainably and organically without the use of fertilizer, pesticides or herbicides.

Fossil fuel use is minimal because there’s no need for farm equipment, transportation of produce into cities, storage or distribution. Unused urban buildings can be revamped as sustainable centers providing healthy food in neighborhoods where fresh produce is scarce, and also creating new job opportunities. In war or disaster zones or refugee camps, modular vertical farms could provide much needed fresh produce. And if vertical farms were implemented on a large scale, we might one day be able to reclaim farmland and restore our soil, forests and ecosystems. Without fertilizer runoff, coastal waters could be revitalized and our fisheries might once again flourish.

Some skeptics have said that the amount of electricity that would be needed to replace sunlight in vertical farms would be prohibitively expensive and unachievable. But Despommier counters that the cost of LED lighting is offset by savings from the elimination of fossil fuel use in fertilizer, transport, storage and distribution, as well as from less spoilage and waste. This, however, remains to be proven, since no one has yet done a life cycle cost comparison between vertical farm-grown crops and those produced conventionally.

Another criticism, no doubt in response to early designs of futuristic vertical farms towering over a city, is that the steep capital investment needed is prohibitive and doesn’t make economic sense. Despommier himself acknowledges that integrating multiple stories of crop growing presents engineering issues that need to be solved. But why do vertical farms have to be in skycrapers?

One year ago, no vertical farms existed. Today the modestly sized vertical farms springing up around the world are proving the skeptics wrong.

Kyoto, Japan’s Nuvege is growing a variety of lettuces in a 30,000-square-foot hydroponic facility with 57,000 square feet of vertical growing space. Amidst fears of radiation contamination from the Fukushima nuclear plant, Nuvege can tout the safety and cleanliness of its crop. Over 70 percent of its produce is already being sold to supermarkets, with 30 percent going to food service clients such as Subway and Disney.

PlantLab in Den Bosch, Holland, is constructing a three-story underground vertical farm that completely eliminates the wave lengths of sunlight that inhibit plant growth. With the latest LED technology, PlantLab can adjust the light composition and intensity to the exact needs of the specific crop. The room temperature, root temperature, humidity, CO2, light intensity, light color, air velocity, irrigation and nutritional value all can be regulated. PlantLab claims it can achieve a yield three times the amount of an average greenhouse’s while using almost 90 percent less water than traditional agriculture.

Growbeds and fish tanks in The Plant. Photo credit: Plant Chicago

In the U.S., a dilapidated 93,500-square-foot former meatpacking facility in Chicago is being transformed into a net-zero aquaponic and hydroponic vertical farm. The Plant will also include an artisanal brewery, kombucha brewery, mushroom farm and bakery. Waste from the food businesses will be used to generate methane in an anaerobic digester, which will produce enough steam and electricity to meet the full energy needs of the facility.

In Seattle, ecological designer Dan Albert and his wife run a 100-square-foot, two-level vertical farm called Civesca (the name is due to change) in a simple warehouse. They will begin selling their aeroponically grown salad greens, mustard greens, and kale to a few local restaurants on Nov. 1.

Purple basil and mizuna growing in Civesca.

Albert gives high praise to his aeroponics technology, created by Ithaca, NY-based AeroFarms. The modular system incorporates aeroponics, programmable LED lights, climate controls, and a proprietary horizontal cloth conveyor that takes the plants from seed to harvest. AeroFarms says its customizable system increases yield up to 60 times that of conventional agriculture, uses 80 percent less water than hydroponic systems and only 3 percent of the land required by conventional agriculture.

In New York City, Big Box Farms is a hybrid vertical farm, growing salad greens inside a one-story industrial warehouse. It stacks plants between 10 and 20 layers high, up to 20 feet high, and uses a proprietary controlled and automated environment and harvesting system that employs LED lights, hydroponics, and 5 percent of the water used by conventional agriculture. The farms will be built right next to food suppliers and distributors to provide them with “private label,” just-harvested products.

About 3 million New Yorkers have no access to supermarkets or fresh produce in their neighborhoods. Vertical farms and other types of urban farming could help low-income residents shop and eat more healthfully. Despommier was a core member of the Earth’s Institute’s Urban Design Lab, whose fall 2003 Urban Ecology Studio project on remediating the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn produced the first concrete vertical farm design (called Agro-wanus by Andrew Kranis) based on his ideas. The Urban Design Lab recently published a report examining New York City’s capacity for urban agriculture, ranging from community gardens to rooftop greenhouses.

Kubi Ackerman, project manager at the lab, told me that the report focuses on “existing” and “shorter-term” solutions, only mentioning vertical farms in passing, “But I’m a fan of Dickson Despommier’s. His work is interesting and there’s real value in having that vision out there to grow the discussion.”

And the discussion is indeed growing. Vertical farms are also being constructed in Manchester, England and Milwaukee, WI. And there is interest around the world—from Newark, NJ to Beijing, China, and in Singapore, Doha, Vancouver, Milan, Amman, Riyadh and Las Vegas. As more vertical farms are created, the engineering and technology will continue to evolve. And one day, NYC may well have vertical farms of all sizes in every borough, providing fresh produce to retailers, restaurants, and community residents. I think it’s only a matter of time…

By Renee Cho