Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Why A Peanut Farmer From South Carolina Created A Facebook For Farmers

Why A Peanut Farmer From South Carolina Created A Facebook For Farmers

OCTOBER 2, 2015 LAUREN MANNING

As a nasty nor’easter hammers the Southeast, hurricane Joaquin lingers just off the Atlantic coast guaranteeing many more days of torrential downpour. For Pat Rogers, a fifth-generation peanut farmer running a 550-acre operation in the small town of Blenheim, South Carolina, the rain is unwelcome.

Peanuts, which grow underneath the topsoil, have to be dug up and flipped over to lie on the soil for a week so they can dry out. The last thing any peanut farmer wants to happen after a “dig up” is rain—let alone the one-two punch of a massive storm and a hurricane.

In prior years, Rogers would have been short on opportunities to commiserate with his farming colleagues about the cruel hand Mother Nature doled out. Thanks to a spark of inspiration and a whole lot of hard work, however, Rogers is hoping to change that for himself and other farmers in the business—and he’s using technology to do it.

“I was at the InfoAg conference in St. Louis during 2014. It’s just a whole bunch of farm tech and I was sitting there in the earliest session, looking around, and thinking, ‘This is great!’” says Rogers tells AgFunderNews. “But, the thing about farming is that so much of it is very rural. It’s not like we can all get together and network very often.”

Rogers returned to Blenheim and quickly set to work creating a way to make invaluable coffee shop chatter, tailgate talk, and barnyard business exchanges a lot more accessible for farmers far and wide. What was one of the first sources Rogers tapped to shape his plan? Entrepreneur Eric Ries’ famous book, The Lean Startup.

Over the summer, Rogers and a team of web developers soft-launched a website called AgFuse, a social media platform dedicated to farmers, and designed to help professionals across the agriculture world connect, share tips, show off their crops, pitch products, and keep in touch. Operating in a similar way to Facebook, with a healthy dose of LinkedIn’s business networking savvy, users can create a profile page, join groups, post messages, and peruse their news feeds to see what’s happening with other farmers in their network.

Building AgFuse’s website from the ground up enabled Rogers and the web development team to create algorithms that help members see the information that’s most relevant to their interests, operations, and needs.

While farm-focused message boards provide a flood of information, AgFuse is calibrated so that users only see postings and information from other members with whom they’ve connected.

For now, the crew is satisfied with its current algorithms, perfecting them is a routine objective. “We have a pretty good system that we are rolling out over the next week or two,” says Rogers.

After observing the soft-launch site and getting feedback from initial users, Rogers, and the AgFuse team, officially launched the site on July 22, 2015. While the platform became an instant hit with Rogers’ local community in South Carolina, he quickly saw users join from around the country and engage with other members.

AgFuse, which Rogers has fully funded himself, has even caught the attention of some venture capital investors. “In the future, that’s hopefully not only a possibility but a reality. Right now we are just focused on building a good product and building our user base,” he says. He also hasn’t ruled out the possibility of monetizing the site to provide members with carefully curated advertisements.

Rogers’ current priorities include site enhancements and building up its user base. They also have some big projects in the works, including a mobile app that is in the final stages of development, and additional AgFuse platforms focused on consolidating farmers’ knowledge around the globe.

According to Rogers, AgFuse is the first farm-centric social media platform of its kind. Although there are a number of message boards dedicated to farming and agriculture topics, he felt they weren’t cutting it when it came to helping farmers make real connections.

“If I sign in from South Carolina and they are talking about crop conditions in Illinois, that doesn’t really pertain to me,” explains Rogers. “You can still learn a lot of general things, but AgFuse’s specific niche is helping farmers find a specific audience.”

Traditional social media platforms haven’t provided a good solution either, tending to involve more talk about play and less talk about business. AgFuse, according to Rogers, is strictly a business affair.

“The content can range anywhere from somebody wanting to show off a good series of coverage crops, to showing a scouting report or weather reports. Somebody just showed a picture of armyworms they found in their soybeans to let everyone know they’ve shown up,” says Rogers.

Although the rain may have dampened Rogers’ hopes for a timely peanut harvest, it’s given him time to work on AgFuse and check in with some of his connections on AgFuse. Today’s news feed was full of reports from other farmers in the region lamenting the weather, with one farmer posting a few pictures of cotton sprouts popping through his plants’ bright white cotton lint—a sure sign that the crop has become oversaturated. Although the news may be a downer, knowing you aren’t the only frustrated farmer in the region has its value.

While agtech is making incredible headway toward helping farmers produce food more efficiently and sustainably, AgFuse is a good reminder not only of the infinite possibilities for technology’s role in agriculture but of how technology can go a long way towards bringing people together.

A Brief History of Modern Farming

A Brief History of Modern Farming

While today it’s possible to grow crops indoors, without soil or sunlight — the way we do at Bowery — this wasn’t always the case. In this post we’re going to provide an overview of the evolution from traditional field farming to industrialized agriculture, explain the differences between greenhouse farming and vertical farming, and introduce you to some of the different techniques used in modern farms today.

From Subsistence to “Super Farms”

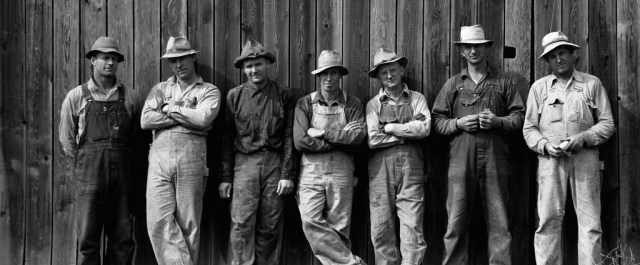

Around the time of the American Revolution, 90% of the population were farmers. Today, only 3% of the U.S. population is employed on a farm, and 2% of U.S. farms produce 70% of all domestic vegetables.(1) So how did we get here?

The first significant inflection point for the agrarian economy came with the Industrial Revolution in the 1850’s, which brought with it the use of machinery to increase productivity and reduce labor. Farmers began to use fertilizers, often in the form of natural organic material like animal waste and manure, and learned to rotate crops to achieve better soil productivity. The first use of chemical pesticides also coincided with this period.(2)

“Excavator on Mile 52 being pulled by traction-engine, plow side. August 8, 1904” by War Department Office of the Chief of Engineers, Chicago District. Image from the National Archives and Records Administration, CC-PD-Mark, PD-USGov.

Between the 1930’s and the late 1960’s, The Green Revolution accelerated new methods and technologies that increased agricultural production worldwide, including the transition from animal to mechanical power, the increased the use of chemical fertilizers, agro-chemicals and synthetic pesticides, and single cropping practices. The rapid industrialization of agriculture during this time period required farmers to become more efficient to remain competitive. It resulted in small farms, which had historically grown a wide variety of crops, being pushed out by large, corporate farms specializing in large-scale monocultures of single high-yielding crop varieties, like corn, soy, or wheat. These corporate farms were able to produce large quantities of food more efficiently to feed a growing population. Yet, this progress occurred at an environmental cost: the proliferation of synthetic pesticides, widespread soil depletion, and a heavy carbon footprint. As a result, many researchers and companies sought more efficient and environmentally friendly ways to feed a growing and increasingly urban population.

“Spraying pesticides” by John Messina for the EPA, May 1972. Image from the National Archives and Records Administration, PD-US-EPA.

Modern Farming

The idea of growing plants year-round by controlling environmental factors dates back as far as the Roman Empire. Emperor Tiberius Caesar had moveable plant beds built that could grow cucumbers year-round by being brought inside during cold or unfavorable weather. Over time, this evolved into the concept of greenhouses, which were used throughout Europe and Asia as early as the 13th century, and worked by trapping heat from the sun within an enclosed structure that insulated plants from cooler, ambient temperatures. These greenhouses, while innovative at the time, were all relatively low-tech compared to controlled-environment agriculture (CEA) today.

Today, CEA can be defined as “an advanced and intensive form of hydroponically-based agriculture,”(3) which uses technology to create and maintain optimal conditions for plant growth and minimize the use of resources including water, energy, and space. CEA works within an enclosed structure to provide a greater level of control over environmental factors which affect plant growth and quality like light, humidity, temperature, CO2, and nutrient levels.

In the 1970’s, greenhouses in the Netherlands were the first to use computer-assisted environmental control systems, but rising commodity prices quickly made the cost of heating and cooling prohibitive, and many of these were forced to shutter their operations.(4)

In the 1980’s and 1990’s, NASA used CEA to grow crops on a Martian Base prototype research facility at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, providing evidence that the nutritive value of indoor-grown food crops could be as good or better than field grown crops.(5) And in 1999, Cornell University built an advanced, commercial-scale CEA greenhouse facility in Ithaca, NY, which grew over 1,000 heads of lettuce per day. Since then, and increasingly over the last 5 years, CEA has been adopted as a commercially-viable solution to urban food production, and companies like Bowery have used CEA to build farms closer to the point of consumption that can produce food efficiently for urban populations.

Modern Farming Techniques

While CEA is a broad term, there are actually a number of different approaches that can be used to grow indoors. These techniques differ in how they deliver a plant’s three primary needs: water, nutrients, and light.

Water: Hydroponics vs. aeroponics

“Hanging Gardens of Babylon” by Maarten van Heemskerck, CC-PD-Mark, PD-Art (PD-old-100)

For water, CEA relies on either hydroponics or aeroponics. Hydroponics is defined as the science of growing plants without soil, and has been used throughout history by the Babylonians, the Aztecs, and even the ancient Egyptians, among others. The commercial use of hydroponics spread after WWII (when it was used by the U.S. Air Force to provide fresh food to troops stationed on small, rocky islands in the Pacific), and continues to accelerate with the development of better accompanying technology and automation. Traditional hydroponic methods, which we use at Bowery, grow plants directly in nutrient-rich water.

Used with permission from San Diego Hydroponics

Aeroponics is technically a subset of hydroponics, and works by suspending plant roots in air and misting them with nutrient water. This method can provide a greater level of control over the amount of water that is used throughout the growing process, but may leave plant roots vulnerable to pathogens, if not carefully controlled.

Nutrients: Hydroponics vs. aquaponics

The second main difference in technique concerns the way nutrients are supplied to the plants. Hydroponics use mineral salts that mirror those naturally-occurring in soil, including minerals like calcium, magnesium, and iron. These mineral salts are combined in precise proportions and dissolved in water to provide nutrients directly to a plant’s roots, allowing for a balanced nutrient environment to achieve optimal plant growth.

Used with permission from Ecolife Conservation

Aquaponics, on the other hand, is a closed-loop system that relies on the symbiotic relationship between aquaculture (fish) and agriculture (plants) for fertilization. While fish waste accumulates in the water and provides the nutrients necessary for plant growth, the plants naturally clean the water. It provides a balanced, yet less regimented, environment.

Light: Greenhouses vs. Indoor vertical farms

Greenhouses vs. indoor vertical farms

Any growing environment requires energy to power photosynthesis. The biggest distinction in Controlled Environment Agriculture is in where this energy comes from, since it doesn’t come (entirely) from the sun, as it does in field farming.

Greenhouses often use a combination of natural and artificial lighting. Greenhouses grow crops indoors in a structure with walls and a roof made primarily of transparent material, like glass or polyethylene, in order to make use of naturally occurring sunlight. They use glass to filter out the UV rays, reducing the heat build-up inside the growing environment. Often, they supplement this sunlight with artificial light to counteract the times when the sun’s energy is either less intense or hidden by clouds.

Indoor vertical farms rely solely on artificial lighting. These farms grow crops entirely indoors inside of a warehouse or shipping container. In some of these farms, crops grow along vertical columns, and in others, they grow horizontally in stacked rows like the stories of a skyscraper (as they do at Bowery). One advantage to relying on LED lights, as we do at Bowery, is that they allow us to grow consistently and reliably 365 days of the year, regardless of weather or seasonality. Another advantage is that we can precisely control their spectrum, intensity, and duration, which allows us to adjust many variables including flavor profiles, and make our mustard greens spicier or our arugula more peppery, for example. We do this using BoweryOS, the software-based brains of our farm.

Inside a Bowery Farm

Until about 5–10 years ago, greenhouse production dominated, but in the last few years more indoor vertical farms have emerged, due in large part to falling LED prices. Both greenhouses and indoor vertical farms can be built in and around cities allowing modern farmers to cut thousands of miles out of the supply chain and deliver fresh produce within days rather than weeks of harvest.

The Future Looks Ripe

While urban farming is on the rise, it still comprises less than 20 percent of agricultural production worldwide today according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization.(6) Yet, this next frontier of farming boasts some important advantages: it allows farmers to produce more output, use fewer resources, and reduce transportation by locating operations closer to the point of consumption. As the global population continues to rise, people continue to move to and around cities, and resources continue to dwindle, indoor vertical farming is going to continue to grow rapidly in both scale and importance. At Bowery, we’re excited to be at the forefront of this growth and are passionate about realizing the potential of indoor agriculture to grow food for a better future by revolutionizing agriculture.

Keep up-to-date with all the latest from Bowery by signing up for our email updates at boweryfarming.com and following us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter. We’re hiring!

SOURCES:

(1 & 2) Trautmann, Porter and Wagenet (2012): Modern Agriculture: Its Effects on the Environment Source via Cornell University Pesticide Safety Education Program (PSEP).

(3 & 5) Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences: Controlled Environment Agriculture.

(4) Rorabaugh, Patricia A. (2015): Introduction to Hydroponics and Controlled Environment — Chapter 1 via University of Arizon aControlled Environment Agriculture Center.

(6) Royte, Elizabeth (2015): Urban farms now produce 1/5 of the world’s foodvia GreenBiz.

Going Green - How Worcester, Central Mass Are Leading The Way

Solar Farm panels on the former Greenwood Street Landfill. Elizabeth Brooks photo.

The irony seeps through the ground – a vast wasteland on Greenwood Street that once held heaps of residential trash for more than a decade is now home to what city officials deem to be the largest municipally-owned solar farm in New England. With a ribbon-cutting ceremony expected to occur sometime this summer, the 25-acre site will have completed its transformation from an environmentally unfriendly dump to one that will be the greenest of the green in terms of energy saving measures.

The solar arrays over on the south side of Route 146 are impressive – 28,600 panels tilted at 25-degree angles, row after row, one after another. And then, just up ahead, with the hills in the distance on the northern side of 146, a lofty wind turbine spins at 262 feet high on the campus of Holy Name Central Catholic Junior/Senior High School. Separately, the two are just some of the many energy efficiency projects in the city; together, they serve as a beacon along the highway, a gateway to the city and the road map for the future. Driving down the highway and seeing both gives a feeling of “Welcome to Worcester,” says John Odell, Energy & Asset Management director for the city.

Welcome to Worcester, indeed. In a world of “going green,” the city has gone green enough that officials there consider Worcester to be a leader in such efforts.

“Yes,” says City Manager Edward M. Augustus Jr. “You might expect me to say that. I think you can prove that.”

In fact, “going green” is not a new concept for Worcester. Efforts date back to before the current administration, and other city institutions, such as Worcester Polytechnic Institute, have been practicing energy efficiency for more than a decade. Worcester was one of the first in the state to have a curbside recycling program and a climate plan, and it was also one of the first certified Green Communities. Even the Beaver Brook Farmers’ Market, which sets up Mondays and Fridays on Chandler Street, is the oldest in Worcester – its roots dating back to the ‘90s, when it was originally located near City Hall.

Even so, “It’s easy not to notice the strides the city has made in green issues,” says Steve Fischer, executive director of the Regional Environmental Council, an organization that started in 1972 with a mission to study clean air, clean water and open space issues. It has since expanded over the years to include other green initiatives, including urban farming.

Today, however, officials want residents to take note of Worcester’s many green efforts.

Saint Gobain Kiln.

Worcester Energy, a municipal initiative of the Executive Office of Economic Development and the Division of Energy & Asset Management, has an extensive website detailing the city’s green projects past and present. And both Augustus and Odell cited three ongoing projects – not only the solar farm, but also a street light replacement conversion and an energy aggregate plan – that have had or will have significant impact on the city. The three together, Odell says, are “near completion or far enough along that we can say we are in a leadership position. We’re in a great position to start spreading the word.”

Ten years ago, the city entered into a multiyear, multi-million energy efficiency and renewable energy project to assess all of its municipal facilities. Honeywell International was hired in 2009 as Worcester’s Energy Services Company to conduct energy audits of those buildings. Two years later, the city signed an Energy Savings Performance Contract for $26.6 million. As part of the ESPC, energy conservation work was to be done in 92 of the city’s largest facilities, out of 171 total. Some buildings have benefited from small changes, such as computer power management systems, while other, more aging facilities have received more extensive improvements – heating and cooling systems, insulation, air-sealing, lighting fixtures and water conservation equipment and solar panels.

The goal, according to Odell, was to save $1.3 million a year – an amount guaranteed by the ESCO. But a recently completed assessment of the ESPC revealed a $1.7-million savings per year.

“Energy efficiency has become a really good investment,” Odell says. “I think it’s important to note that the dollars are real. It costs money to do these things, but because of the benefits you get, it’s a savings.”

Mayor Joe Petty agrees, saying green energy is ever-important, not just for the environmental aspects, but for cost-savings as well.

“I know it’s a little more expensive sometimes, but that in itself is a positive,” he says, adding the city’s endeavors are going to save millions of dollars over the next several years.

A major contributor to those savings are the city’s numerous solar projects, including the Greenwood Street solar array. Although it cost approximately $28 million to construct, with a three-year payback, the 8.1-megawatt farm will produce about 10 million kilowatt hours of electricity each year once connected to National Grid’s distribution center. That’s enough to offset the electricity used by more than 1,300 homes in the city. In total, the city expects a return of about $50 million over the 20 years of the project, plus approximately $15 million more the following 10 years.

“It’s equivalent to 19 football fields of energy,” Augustus says. “That’s a big deal in terms of taxpayers’ dollars and in terms of shrinking our carbon footprint.”

Another major project completed this past fiscal year involved the installation of approximately 4,500 LED, high-efficiency street lights throughout the city, a measure expected to save $400,000 in electricity costs. Once all 14,000 planned street lights are switched over, city officials say they expect the savings to be more than $900,000 per year.

Beyond the cost savings are the additional benefits that come with the new street lights. Officials say the lights will cost less to maintain and have longer life cycles, reduce carbon emissions and light pollution at night, and improve lighting quality overall, plus give a sense of greater security. According to Augustus, Los Angeles County did a similar street light conversion and officials there credited the project with a 10-percent reduction in crime because the intensity of the lights was able to be calibrated at specified times.

“There are a lot of operational efficiencies that come from having this kind of technology,” Augustus says.

In addition to those projects, Worcester has upgraded lighting at four parking garages to LED, saving an additional $89,000 per year in electricity costs; completed a $1.7 million lighting upgrade project at the DCU Centre without using any taxpayer funds; and replaced a failing HVAC center at the senior center, among other initiatives, with more on the way. And when President Donald Trump announced the federal government would no longer participate in the Paris Climate Agreement, Petty made his own announcement: that the city would continue to battle climate change locally and invest in green technology.

“As our federal government retreats from its responsibility as steward of our environment, it is vitally important for state and municipal government to uphold our commitment to the future of our planet,” says Petty, who joined mayors across the country in signing the U.S. Climate Mayors statement. “If the president doesn’t want to do it, we will.”

Mary O’neill and Eva Elton display fresh produce at the Mobile Farmers Market Laurel St. location, in Plumley Village.

Green Schooled

Worcester Public Schools has gotten into the green zone as well. Over at 35 Nelson Place, a school dating back to 1927 is being demolished in preparation for a new building to serve Worcester students in pre-kindergarten through grade 6 starting this fall. But unlike the old Nelson Place School, the new 600-student facility will be twice the size – 110,000 square feet compared to the original’s 55,000 square feet – and will be the city’s first-ever, net-zero energy building, defined by the U.S. Department of Energy as, “an energy-efficient building where, on a source energy basis, the actual annual delivered energy is less than or equal to the on-site renewable exported energy.”

And even though “you could effectively pull that building off the grid,” Odell says, that doesn’t mean the new school is being built with highly-specialized technology and equipment. On the contrary, it’s all “off-the-shelf technology.”

According to Brian Allen, chief financial and operations officer for Worcester Public Schools, the roof’s solar panels will provide 100 percent of the building’s energy, and together with the high-efficiency windows and insulation, “natural gas for heating will be one-third of what we’re using.”

“You basically have one school taking care of itself,” Augustus says. “Imagine if I could have every city building take care of itself.” The school was designed as a green building from the start as part of the application process for the Massachusetts School Building Authority, which works with cities and town across the state to help build affordable, sustainable and energy-efficient schools. Because the state offers more reimbursement credits for green buildings, it made more sense to create the new Nelson Place School as net-zero energy, Allen explains.

The new Nelson Place School is just one of the many examples of how the city of Worcester and the educational system have collaborated on the ESCO contract, and in the near future, the hope is to do another energy partnership with the schools, Augustus says. Many of the schools have benefited from new doors and windows, with others slated for similar work soon.

“The city,” he says, “has been very aggressive over the years with window replacement, making them energy-efficient and more aesthetically pleasing in some of the older buildings.”

Other schools have been outfitted with new boilers and exterior LED lights, while converting interior lights is currently being explored, according to Allen. In addition, the school district as a whole also benefits from numerous solar panels at its buildings, about 3 million kilowatts of energy, Allen says. Two of the schools have parking lot canopies, and eight – including the new Nelson Place – have roof arrays. Four of those roofs, according to Odell, were nearing the end of their lifespan and were resealed with white roof coating application instead of black to make the arrays more effective.

“The net effect,” said Odell, “is we got the roofs for free.”

As a result, all of these green efforts are beneficial to the city and school district and the students. “Any way that we can be part of the initiatives and save money and be more environmentally aware, it seems to perfectly align with the mission of the school district,” Allen says, noting it also demonstrates to students that there are ways to be environmentally conscious and friendly.

The solar panels on the roof of the new Nelson Place School

Windfall

Holy Name’s wind turbine is another example of how the city has collaborated with schools. Although it is a private school and no city funds were expended to construct the turbine, regulations did not allow for such projects a decade ago. City officials, however, allocated staff resources to review the regulations, and as a result, in June 2007, adopted the Large Wind (Energy Conversion Facilities) Ordinance, allowing for wind turbines to be located in Worcester by special permit with provisions for height, abutting uses buffers and noise regulations.

The turbine has been largely successful. Holy Name, built in 1967 and heated electrically, was paying $180,000 in utility bills each year, according to a sustainability profile by Worcester Energy. In 2015, when the report was written, the turbine was producing an average of 74 percent of Holy Name’s yearly energy needs.

That’s one of the reasons why Worcester officials feel it is so important to partner with other schools and businesses on green technology.

“It allows us to be credible,” when businesses want to locate or relocate in the city, so that they don’t feel like they’re working on projects in isolation, says Odell.

City officials also believe it is important to help residents go green – and stay green. The Municipal Electric Aggregation program, which City Council recently approved, pools all of Worcester’s National Grid customers into one negotiating block as long as they are signed up for the Smart Grid program. By doing so, the city can offer residents and businesses various components of green energy to them.

“That’s the next big thing,” Odell says. “You can make your own portfolio greener.”

Saint Green

One such company that is no stranger to green issues is Saint-Gobain, a world leader in designing and building high-performance, innovative and sustainable building materials. Recently, the company announced a renewed commitment to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Better Plants Program, which works with manufacturers to improve energy efficiency to drive cost savings for the industrial sector. Eighty four of Saint-Gobain’s manufacturing plants in the country – Worcester included – are participating in the program, with a goal of achieving an energy savings of 20 percent over the next 10 years. Saint-Gobain joined the program in 2011, the same year it launched.

Michael Barnes, vice president of operations for Saint-Gobain Abrasives North America, says the company chose to focus on the Better Plants Program because it “really aligns with our own strategic direction. Saint-Gobain is committed to not only what we do every day with the products we make and sell, but in the communities as well.”

In Worcester, specifically, the plant is getting a lights makeover with the installation of LED lamps, plus a new kiln was installed. Many of the company’s products, Barnes says, are fired in high-temperature kilns, and the new one has provided the company with a significant reduction in natural gas consumption. In addition, Saint-Gobain in Worcester has its own powerhouse that generates steam, which in turn heats the buildings, so that the company not only procures energy but produces it as well.

It’s a “very smart move,” Barnes says, to look at the energy the company consumes and expels. Part of that as well is the company’s carbon monoxide emissions, which SaintGobain seeks to reduce by 20 percent.

With these strategic, long-term plans “heavily supported” by capital investment, a creative team and the continued financial support from the corporation, Barnes says, it shows Saint-Gobain’s commitment to remain in Worcester and to contribute to the city’s employment rate.

“It’s difficult to do business in New England. It’s a high-cost area. It’s very highly regulated environmentally. It’s easy for people to say, ‘Let’s do this elsewhere,’” Barnes says.

But, he adds, the company remains committed to its Worcester roots and helping the environment as well through its Better Plants Program participation.

“Energy is a very critical cost component. That’s why we take this initiative seriously,” he says, adding, “This isn’t just something we talk about. It’s something we’re committed to.”

While the company cites its efforts to become more environmentally friendly, it has not been without its missteps. Saint Gobain allegedly violated the Clean Water Act, reaching a settlement last December with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that required the company to pay a $131,000 penalty and to install new storm water treatment equipment.

Technically Green

If Worcester and its businesses have been in the green game for some time, WPI has, too. In fact, its very mission statement pledges the college will “demonstrate our commitment to the preservation of the planet and all its life through the incorporation of the principles of sustainability throughout the institution.”

WPI has a Sustainability Plan, an initiative put into motion during spring 2012 by the WPI Task Force on Sustainability, that outlines goals, objectives and tasks for academics, campus operations, research and scholarship, and community engagement. It offers 119 undergraduate and 30 graduate sustainability related courses, as well as a minor degree in sustainability engineering. And, back in 2004, five undergraduate students from the college were the ones to conduct the wind turbine study at Holy Name’s request.

Ten years ago, the Board of Trustees passed a resolution that all new buildings be designed to meet LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification, a national rating system created by the U.S. Green Building Council. Today, WPI boasts four LEED buildings: Bartlett Center, LEED Certified in 2006; East Hall, LEED Gold in 2008; the Recreation Center, LEED Gold in 2012; and Faraday Hall, LEED Silver in 2013.

Although WPI has many sustainability programs, two have stood out, according to WPI Director of Sustainability John Orr, who is also a professor emeritus of electrical and computer engineering.

“The project with the greatest environmental impact has been our building energy and lighting retrofit program that saves energy and reduces greenhouse gas emissions,” Orr says. “This is largely invisible to the community, but has a great environmental impact. Our bike share program, Gompei’s Gears, is highly visible and has received great community feedback.”

Gompei’s Gears was originally an Interactive Qualifying Project (submitted for degree requirements) by two students, Kevin Ackerman and John Colfer, and the program has evolved from an idea in 2015 into a fullscale program. Gompei’s Gears, named after the WPI mascot, allows students, faculty and staff access to bikes from various locations on campus that they can ride anywhere on site or even off school grounds. It is available after spring break (weather depending) until the first snowfall.

For all its efforts, in June WPI earned a gold rating in the Sustainability, Tracking, Assessment and Rating System (STARS), awarded by the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education. Two years ago, the first time the school submitted a STARS application, it earned a silver rating and worked hard to improve upon that. This year, WPI was one of 117 schools out of 415 total that received a gold rating. Only one received platinum, 201 silver, 67 bronze and 29 reporter rating.

Orr says he believes the campus’ four LEED-certified buildings – with another under construction – Gompei’s Gears, the building energy upgrades and other programs make WPI a leader in the “going green” movement out of colleges in similar size.

“Also, very much in our educational programs – environmental engineering and environmental and sustainability studies – and our global project programs in developing nations,” Orr says. “Advanced technology is required to address the world’s environmental challenges, and we are showing leadership in our campus operations, our educational programs and our research (advanced batteries, biomass, advanced recycling, etc.).”

Leeding and Leading the Way

Other Worcester and Central Mass colleges are making an effort to go green as well.

At Assumption College, the new Tsotsis Family Academic Center, which will open this fall, and site lighting were all designed for LED lights, with the exception of specialized lighting in the performance hall, according to the school’s Office of Communications. Five interior space renovations are underway, where the lighting will be replaced with LEDs and reverse refrigerant systems will be installed in place of air-conditioning to control the temperature within those particular spaces. In addition, speed controllers were added to the HVAC units in the Fuller/IT buildings, and last summer, low flow shower heads and aerators were installed on the sink’s faucets in all the resident halls. Opened in 2015, it is the first building on the campus to be designated LEED certified and is the only Gold-certified building in southern Worcester County (a term sometimes used to define towns south, southwest and southeast of Worcester), according to college officials.

Over at Nichols College in Dudley, its newest academic building was awarded LEED Gold certification last year. Opened in 2015, it is the first building on the campus to be designated LEED certified and is the only Gold-certified building in southern Worcester County, according to college officials. The three-story building’s green components include locally-sourced and recycled materials; excellent indoor air quality; efficient water use systems; sensors that better control heating and lighting in individual rooms; and large windows for natural light, which reduces the need for interior lighting and minimizes the use of electricity during the daytime.

“Gold LEED certification for the new academic building is an exciting accomplishment and a statement to Nichols College’s commitment to environmental stewardship,” says Robert LaVigne, associate vice president for facilities management at Nichols. “Since opening its doors last fall, the building has served as a testament to the college’s dedication to innovation – not only in sustainable design, but also education.”

Other green programs at Nichols include its single-stream, campus-wide recycling program, food waste recycling at Lombard Dining Hall, geothermal heating and cooling systems at two residence halls and LED conversion of all exterior lights on campus. In addition, Fels Student Center received National Grid’s Advance Building Certification for energy efficiency.

Food for Thought

But “going green” doesn’t just refer to eco-friendly buildings, energy-efficient lights and solar panels – it can also mean the food we eat and how it is sourced. In cities, people don’t always have access to fresh food, but Worcester has been working to change that as well.

On Mondays and Fridays, from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. at 306 Chandler St., the Beaver Brook Farmers’ Market sets up shop with local produce, plus bread and craft vendors. Originally the Worcester Hill Market, it is the oldest farmers’ market in the city, according to Fischer. It moved to Chandler Street when the front of City Hall closed for repairs, and the REC took over management in 2012.

Beaver Brook is just one of the city markets, which all opened in late June and run through Oct. 28. The University Park Farm Stand, a Main South staple since 2008, moved to its current location last year so that the REC could more closely partner with Clark University, the Main South Community Development Corporation and other area organizations to provide not only fresh food but family-friendly activities as well. It is open every Saturday, from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m., at 965 Main St. The REC also runs the Mobile Farmers’ Market, which makes 16 stops around the city Tuesdays through Fridays, bringing locally grown produce straight to residents who might not otherwise be able to travel to a farm stand. Fischer notes the city is home to many other farmers’ markets not run by the REC. “We’re seeing a demand in farmers’ markets,” he says. “We’re seeing a demand for local food.” Martha Assefa, manager of the Worcester Food Policy Council, agrees.

“There are so many amazing farmers’ markets happening in the city,” she says, recalling, “A while ago, it was a few folks at the table talking about this. Now local food and food access is becoming mainstream. I think folks are much more interested in buying local than they were 15 years ago.”

But is buying fresh and local more expensive? The Healthy Incentives Program makes sure people who receive SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) assistance have just as much access to fresh food as others. Through March 31, 2020, the program will match any SNAP dollars spent at farmers’ markets or stands, mobile markets and Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) farm stand programs. Families of one to two people can have up to $40 instantly debited back to their EBT card each month, $60 for three to five people, and $80 for families with six or more people.

“I think many folks realize it makes sense to buy local,” Assefa says, adding it reduces the amount of food travel from producer to consumer, and it also reduces some of the packaging it comes in as well. Plus, it directly helps local farmers – and all that leads to a greener planet.

“A lot of the farming community knows how important it is to protect Mother Earth. A lot of the farmers are innovators. If they don’t protect it, they’re going to see it on their fields,” Assefa says. “That’s the forefront of it all,” she says. “Plus, local food tastes better.”

Urban Gardens

Just as farmers’ markets are not reserved for the suburbs, neither are gardens. In 1995, the REC started a network of urban farms and community gardens that has now grown to 64 in number. These farms have allowed citizens to contribute to the community, learn about growing their own food and beautify their neighborhoods. There are also 20 gardens at the public schools, as well as a youth program in Belmont Hill for ages 14 through 18 that has been in existence since 2003, Fischer says. Both programs, he says, are “transformative,” adding that, for many, this exposure to gardening is the first time students see “how a carrot comes to be, how lettuce comes to be, other than buying it in stores.”

And by working in the gardens, Fischer continues, “They can see the fruits of their labor. It has an amazing impact.”

That’s precisely why groups in the city are pushing for more urban farming – specifically to allow residents to grow and sell their own food. Although personal gardens are allowed, Fischer says, residents are not currently permitted to set up roadside stands or sell to farmers’ markets or stores.

The Urban Agriculture Zoning Ordinance seeks to change that.

“It’s a set of rules to make sure there are rules in place for growing and selling food in the city,” Fischer says. “Right now there’s a big hole in the regulations for growing food in the city.”

Currently in committee hearings, the ordinance has been three years in the making, after the mayor convened a working group with concerned citizens, those associated with urban farming, the Chamber of Commerce and other groups to look at the zoning regulations from environmental and social justice perspectives, Fischer says.

The Worcester Food Policy Council is also heavily involved with the proposal to make sure anyone in the city can farm their land and in turn sell their products. The ordinance has received some pushback, however, particularly among area beekeepers who worry it will infringe upon their efforts.

The ordinance would require beekeepers to notify abutters that they have bees, which the keepers find potentially prohibitive. Worcester Magazine wrote about their concerns earlier this month, in a story titled, “Beekeepers buzzing over proposed urban agriculture ordinance.”

Still, says Fischer, the ordinance and other work is an acknowledgment that urban agriculture is real.

“There is a growing interest as to how the food is produced and where it is grown and the quality of how it’s grown,” he says, noting that “it’s full circle, and essentially we need to rebuild the infrastructure that was dismantled over the last decade, and also to rebuild the biodiversity.”

Plus, says Fischer, “It’s exciting to have the city and local businesses and the residents taking an interest in these things and providing leadership in moving things forward.”

It is a project of which the mayor is particularly proud.

“I think it’s a great asset to the city,” Petty says of the ordinance. “We are taking what people are doing anyway and putting some rows around it.”

Plus, he adds, with that and the existing farmers’ markets, “It’s a driver for jobs. We’re taking locally grown food and selling it.”

Barking Up a New Tree

Amanda Barker knows much about urban agriculture. On a sunny day, she is planting scallions at Cotyledon Farm, her newest venture in nearby Leicester. She is the founder of Nuestro Huerto on Southgate Street in Worcester, which she watched grow from a small-scale community garden to a successful urban farm.

When she moved to Main South eight years ago for graduate school at Clark University, she didn’t know anyone but had a desire to “ultimately help create and become part of a community around food,” she recalls.

Barker started a garden in her back yard, but soon found the shady space and the lead in the soil made it unsuitable for growing anything. Faced with needing to take on an unpaid internship for her requirements at Clark, her “practical” gardening project ended up becoming long-term when she set up on land owned by Iglesia Casa de Oración (House of Prayer Church). Initially, she says, she started with 10 raised wooden garden beds, with the intent to give away the food for free. Eventually, it became a full-scale urban CSA.

“It demonstrated interest and demand for those projects. Certainly, we weren’t lacking for volunteers, depending on the day,” Barker says, recalling that there were always a “lot of young people showing interest in being outside and being in a non-city place. It was a respite and a green space.”

Today, after a largely successful run, Nuestro Huerto and the CSA are now closed to the public, but with good reason—the site is host to three farmers from Nepal who will use the opportunity to provide for themselves, their families and their communities. Barker still serves as a liaison for the project, she says, even though the farmers are mostly independent.

“You can produce incredible amounts of food, and they certainly are. Every inch is going to be packed with vegetables,” she says.

It is why she has “mixed thoughts” on the Urban Agriculture Zoning Ordinance.

“What I want is everything to be allowed by right in all zones,” Barker says. “We’re human beings; we eat food. What is there to have a conversation about?”

If the proposal is successful, it should address some of her questions and transform some of those blank spaces into only more green spaces for the city.

“We’re excited about the potential urban agriculture has in responding to how difficult it is for some people who are working hard but are unable to access fresh food,” Fischer says. “It also makes neighborhoods beautiful. That is a key strategy for beautifying the city.”

Not only that, but “people in the area grow to love those neighborhood farms, and they look out for it,” he says. Between the urban farms and solar farms, plus all the energy-efficiency programs, is there room for Worcester to improve? Augustus says,“Yes,” adding Worcester should “continue to set the pace of what can be done by a municipality … in terms of great and innovative ways to save the taxpayer money instead of being paid to a utility to produce.”

Worcester, Petty says, “is killing it” not only with green issues, but other aspects as well, such as the arts.

“I think we have a government that’s pretty interactive, and people are noticing. We’ve made all the right decisions so far.” When it comes to going green, he says, “This is good, cooperative effort between the government and the community.”

Harvest Dinner

Harvest Dinner

THE EVENT

Join us for a unique evening at the Indiana State Fair benefiting the Indiana State Fair Foundation!

Traditional harvest dinners bring together family and friends for celebration and fellowship at the end of a long planting season. They are the culmination of months of hard work, commitment and stewardship. They are the very essence of what it means to be a farmer in Indiana.

The Indiana State Fair is our state’s largest celebration of agriculture, so what better way to celebrate than with a Harvest Dinner to honor Indiana’s farmers.

This year’s event will take place on Wednesday, August 16, in the Indiana Farmers Coliseum.

HARVEST AWARD

Purdue University President Mitch Daniels Accepting the 2016 Harvest Award

The Harvest Award is given annually at the Harvest Dinner to an individual, organization or company that has made a significant contribution to the growth of our great Indiana State Fair with a focus on agriculture, youth and education.

Past Harvest Award Recipients:

DOW AgroSciences – 2015

Purdue University – 2016

FUNDRAISING

All proceeds from this event will benefit the Celebration of Champions which awards the hard working 4-H youth who rise to the top of their peers at the Indiana State Fair.

Click Here to learn about sponsorship opportunities and to reserve your table today!

Indoor Farming Plus Made In USA LED Grow Lights: Profile 1.8

Indoor Farming Plus Made In USA LED Grow Lights: Profile 1.8

GREENandSAVE Staff

Posted on Thursday 29th June 2017

This is one of the profiles in an ongoing series covering next generation agriculture. We are seeing an increased trend for indoor farming across the United States and around the world. This is a positive trend given that local farming reduces adverse CO2 emissions from moving food long distances. If you would like us to review and profile your company, just let us know! Contact Us.

Company Profile: Gotham Greens

Here is a great example of an urban farm with greenhouse locations on rooftops of New York City and Chicago.

Here is some of the “About Us” content: Gotham Greens’ pesticide-free produce is grown using ecologically sustainable methods in technologically-sophisticated, 100% clean energy powered, climate-controlled urban rooftop greenhouses. Gotham Greens provides its diverse retail, restaurant, and institutional customers with reliable, year-round, local supply of produce grown under the highest standards of food safety and environmental sustainability. The company has built and operates over 170,000 square feet of technologically advanced, urban rooftop greenhouses across 4 facilities in New York City and Chicago. Gotham Greens was founded in 2009 in Brooklyn, New York and is privately held.

Our flagship greenhouse, built in 2011, was the first ever commercial scale greenhouse facility of its kind built in the United States. The rooftop greenhouse, designed, built, owned and operated by Gotham Greens, measures over 15,000 square feet and annually produces over 100,000 pounds of fresh leafy greens. The greenhouse remains one of the most high profile contemporary urban agriculture projects worldwide.

Here is the link to learn more: http://gothamgreens.com/.

To date, the cost of man made lighting has been a barrier for indoor agriculture. A new generation of LED lighting provides cost effective opportunities for farmers to deliver local produce. Warehouses and greenhouses are both viable structures for next generation agriculture. Here is one example of next generation made in USA LED grow light technology to help farmers: Commercial LED Grow Lights.

13 Facts About "Organic" Foods That Will Shock You

image: http://mobile.wnd.com/files/2017/07/organic-fruits-vegetables-tw-600.jpg

No Testing, Mostly Imported, More Sickness, Higher Costs, More Subsidized

WASHINGTON – Do you choose “organic” produce because it’s healthier and locally grown?

Think again.

And that’s not the worst of it, says the report by the Capital Research Center.

Here are some shockers about how the “organic foods” phenomenon is costing you more, making foods less safe and costing real American organic farmers marketing share:

http://mobile.wnd.com/files/2017/07/USDAorganicbudget-386x1024.png

1. So-called “organic food” in America tests positive for synthetic pesticides four times out of 10.

2. Up to 80 percent of food labeled “organic” in American stores is imported. This increase has coincided with incidents of organic food-borne illness.

3. The USDA tripled its organic foods budget over the last eight years without requiring any field-testing of either domestically grown produce or imported.

4. During that time, tens of millions of dollars in subsidies were given to preserve the 0.7 percent of American farmland devoted to growing organic food.

5. The USDA has increased spending to $9.1 million on the organic bureaucracy, yet none of its 43 staffers are responsible for finding fraud, field-testing for safety, recalling unsafe food or encouraging domestic farming.

6. About 43 percent of the organic food sold in America tested positive for prohibited pesticide residue, according to two separate studies by two separate divisions of the USDA, conducted in 2010-2011 and 2015.

7. Organic groceries accounted for 7 percent of all food sales in America last year, but the U.S. government contracts out organic inspections to a total of 160 private individuals for the entire country. There are only 264 organic inspectors worldwide.

8. The USDA’s National Organic Program tests only finished product and only 5 percent of the time covering only pesticides, never looking for dangerous pathogens from manure. Yet synthetic pesticides show up 50 percent of the time. It took until 2010 before any field-testing at all was required by the USDA.

9. The USDA “certified” label for organic food is not based on any objective, scientific process that ensure authentic or safe produce. In fact, the program is regulated by the USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service and not connected to the department’s food safety, research, inspection, nutrition or risk management services.

10. Many natural pesticides approved for organic use are more toxic than the synthetic ones used by conventional farmers.

11. Though the USDA insists on an annual onsite inspection of every organic farm and facility it certifies, the inspector (regardless of country) needs permission from the farmer or processor whose facilities he or she intends to inspect, and he or she makes an appointment weeks in advance. Individual inspectors can be refused contracts to perform inspections by any USDA-certified organic entity, with no reason required.

12. Many of the 79 certifying agencies that grant USDA organic certification to farmers and processors receive 1.5 to 3 percent of gross revenue from their clients – this “royalty” from an industry worth roughly $40 billion a year. As noted, certifiers collect these royalties only on shipments they approve.

13. Many farmers make use of manure, but usually not on crops for human consumption. Only in the organic industry is manure routinely applied to fields growing crops for humans, a practice which can be detrimental to human health – even deadly, especially when manure is not fully composted. Even so, the USDA does not require field testing for possible fecal contaminants on the organic crops it certifies, even though such testing costs less than $25 per episode.

As long as consumers believe organic food is worth more (that it is “wholesome,” “natural,” and “authentic,” so certified by the USDA) no one making money in the organic sector will be obligated to prove organic food is worth the extra cost. Meanwhile, the interests of non-organic consumers, conventional and biotech farmers, processors, and wholesalers recede as the organic movement, with its knee-jerk opposition to modern farming, dominates the debate and sets the rules.

When Walmart Leaves Rural America…

Many rural people still celebrate when Walmart comes to town. However, we now know the eventual consequences for new Walmart communities.

When Walmart Leaves

Rural America…

The town “still boasts imposing brick buildings as a memory of better times. But the glow of coal’s legacy has cooled, as the boarding up of many of the town’s shops and restaurants attests.” This description of a coal mining town in Appalachia might just as easily describe a typically farming town in Middle America. The description is from a recent article in US edition of The Guardian: “What happened when Walmart left?” The place abandoned by Walmart was McDowell County—an economically depressed county in rural West Virginia. If current trends are allowed to continue, this may also be the future of farming towns all across America.

Coal mining was the economic foundation of McDowell County. When coal miners were replaced by technology—giant digging and hauling machines—many local residents were left without jobs or any other economic means of making a living in the county. It wasn’t only the mining jobs that were lost, but all of the other jobs needed to meet the varied needs of the miners and their families. “McDowell County has seen a devastating and sustained erosion of its people, from almost 100,000 in 1950 when coal was king, to about 18,000 today. That depleted population is today scattered widely across small towns and in mountain hollows, accentuating the sense of sparseness and emptiness.”

Farming was the economic foundation of many rural counties in the Middle America. As farmers were replaced by agricultural technologies—machines, agri-chemicals, livestock confinements—many local residents were left without jobs or other economic means of making a living in the community. It wasn’t only the farmers who lost their livelihoods, but all of the others local residents who had met the various economic needs of the displaced farm families. Farming communities all across America have seen the devastation and have sustained the erosion of rural people caused by the industrialization of agriculture. The depleted rural populations today are scattered widely across small towns and the rural landscape, accentuating the sense of rural economic depression and social disintegration.

The economic demise of mining towns is just more visible and more easily understood. When flying over the mountaintop removal coal mines in Appalachia, the environmental devastation is clear and compelling. Looking down at the green center-pivot crop irrigation circles on the High Plains creates a very different image—a false image of vitality. Both enterprises are mining nonrenewable natural resources. Coal mining is simply more obvious than water mining. These industrial farming operations are also mining the natural fertility of the soil, the only sustainable source of productivity. The demand for coal is slowing, environmental restraints of coal fired power plants are growing, and alternative energy sources are on the horizon. Meanwhile, demand for agricultural production is growing, industrial farming is heavily subsidized and virtually unregulated, and there are no alternatives to soil, water, or food. The erosion, degradation, salinization, and desertification of farmland may be occurring at a rate even faster than the depletion of coal.

Another major difference is that Coal mining is unsustainable by nature, but farming is unsustainable by choice. The earth’s reserves of usable and economically recoverable coal are finite and eventually and inevitably will be depleted. Soil, water, and solar energy are renewable resources that are capable of sustaining a resourceful, resilient, and regenerative agriculture indefinitely into the future. Unlike coal mining, today’s extractive, exploitative industrial system of farming is a matter of choice, not necessity. Regardless, the economic and social consequences of coal mining and industrial farming are much the same for rural communities.

Walmart got its start in the 1960s by moving into farming towns that were in early stages of economic decline—also the early stages of agricultural industrialization. The prosperity brought to farming and farming towns by World War II was fading. Local merchants were offering lower quality products at higher prices in an attempt to maintain their profit margins. Sam Walton understood rural people and saw an opportunity for continuing expansion and growth of Walmart in the face of rural economic decline. Walmart would offer better quality products at lower prices to rural people.

Early on, Walmart would not locate a store in a town with more than 15,000 people or more than 500 miles from Bentonville, Arkansas. Obviously those days are long past. Walmart found there were people in urban areas who also thought prices in their communities were too high. Walmart’s expansion strategies obviously have changed but its philosophy remains virtually unchanged. Walmart prospers from serving those with declining economic opportunities. Lower prices are their key to better living—but only as long as prices and sales are high enough to maximize profits and growth for Walmart. When that’s no longer the case, Walmart closes stores and leaves town.

Many rural people still celebrate when Walmart comes to town. However, we now know the eventual consequences for new Walmart communities. Quoting from the Guardian article, “Much has been written about what happens when the corporate giant opens up in an area, with numerous studies recordinghow it sucks the energy out of a locality, overpowering the competition through sheer scale and forcing the closure of mom-and-pop stores for up to 20 miles around. A more pressing, and much less-well-understood, question is what are the consequences when Walmart screeches into reverse: when it ups and quits, leaving behind a trail of lost jobs and broken promises?” In the Guardian article, the people in McDowell County expressed a deep sense of betrayal, depression, and loss of hope for the future of their community.

Communities abandoned by Walmart obviously are left with few surviving local retailers to supply the basic needs of people in the community. By the time Walmart leaves, a community is no longer seen as a logical place to start a new business venture. Walmart only leaves when the “economic carcass” of a community is pretty well “picked clean.” However, the people are also left without the social connections and sense of community that becomes centered on shopping at Walmart, once other local retailers are gone. There is no common local place for people to see and visit with their neighbors as they drive off in different directions to find the nearest remaining Walmart-like store in the area. There are no local businesses left to replace Walmart’s PR-motivated contributions to the Girl Scouts, Little League, county fair, local food bank, or other charitable causes. The Guardian article focuses on the deep sense of personal or even spiritual loss by local residents, which few might have expected from the closing of a Walmart Supercenter.

The basic point of this post is that if we do not stop and reverse the ongoing industrialization of American agriculture—with its miles and miles of corn and soybeans and giant animal factories—rural communities all across America can expect their Walmart to leave town. They can expect the same deep sense of economic, personal, and spiritual loss the local folks felt in McDowell County, West Virginia. Walmart came to much of rural America because rural America had bought into the extractive, exploitative system of industrial agriculture. When Walmart leaves rural America, it will be because there is nothing of economic value left for industrial agriculture or Walmart to extract or exploit.

However, the people in rural American have a choice. There are better ways to farm and better ways to develop rural economies. They can choose to replace industrial agriculture with an ecologically sound, socially just, economically viable—socially responsible agriculture. Then, Walmart can leave town, along with industrial agriculture, and people in rural American will be glad to see them both gone.

John Ikerd

At The Innovation Apex of Agriculture

At The Innovation Apex of Agriculture

New crops, automation and big data fueled conversations at the 5th annual Indoor Ag-Con in Las Vegas.

July 27, 2017 | Patrick Williams

Photo: Patrick Williams; Logo courtesy of Indoor Ag-Con

Between the metallic dinosaur at the trade show’s entrance, vertical gardens exhibiting multicolored lettuce and leafy greens, and booths showing off the latest in lighting technology, the 5th annual Indoor Ag-Con in Las Vegas, May 3-4, provided attendees an all-encompassing tour of controlled environment agriculture (CEA) and the technology and innovation that surround it.

Produce Grower was proud to be a sponsor of the event, where sessions focused on everything from securing funding to managing lighting needs to ensuring food safety. To learn more about the keynotes and Produce Grower’s general takeaways from Indoor Ag-Con, listen to our event recap at bit.ly/2tJ0yB4. In these pages, we will look at sessions centered around new crops and the future of automation and big data in CEA.

New Crop Opportunities

From drastic flavor modification to growing crops with major health benefits, the Indoor Ag-Con session “Which crops will move indoors next?” spotlighted new crop opportunities in CEA.

By changing one ingredient in a hydroponic mix, Dr. Deane Falcone, SVP, plant sciences and product development at FreshBox Farms, says he and his colleagues have been able to modify the flavor intensity of arugula to create mild and spicy varieties. “[The spicy variety] is very, very spicy, and the mild is almost completely bland,” he says. “That means we have the opportunity to titrate that and ... make yet a third one.”

Additionally, scientists can adjust the phytonutrient content of specific crops to produce anticancer qualities, Falcone says. Studies over the past 10 to 15 years, for instance, have shown that broccoli possesses anticancer activity through compounds called sulforophanes, he says.

Ice plant (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum) and purslane are other crops that growers may want to consider adding to their existing offerings, Dr. Richard Fu, president of Agrivolution, discussed in the session. These crops will not only allow growers in the United States to differentiate their product lines and stick out from the crowd, he says, but they carry health benefits as well.

The inositol in ice plant helps reduce insulin resistance for people with prediabetic conditions or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and it contains beta-Carotene and Vitamin K. The Super Omega-3 and alpha-linolenic fatty acids in purslane, meanwhile, can help alleviate allergies. To learn more about ice plant and purslane, read Greenhouse Management’s Q&A with Fu at bit.ly/2uFT6EG

In the fruit realm, Driscoll’s, the largest berry marketer in the world, has recently begun growing blackberries in glasshouses and has seen promising results, says Ian Justus, senior manager, controlled environment production. Justus works in research and development and produces high quality and high yields growing the company’s new Victoria variety under glass.

The Victoria crops grow approximately 13 feet tall, which makes them difficult to harvest on foot but conducive to cart passes in the greenhouse, Justus says. Multiple supplemental lighting sources exist in the glasshouses. “We’ve got high-pressure sodium lights at the top, and we’ve got really intricate LED bars down at the bottom,” Justus says.

Clockwise from left: Dr. Deane Falcone, Dr. Richard Fu, Ian Justus, Alastair Monk, Darryn Keiller, Nate Storey

Photos courtesy of Nicola Kerslake

The future of Big Data and Automation

Many produce growers have some type of automation set up in their greenhouse or vertical farm, and all of them collect data in some way. But how can growers use automation and large data sets to improve their operations, and is there room in CEA for data sharing? These are questions that were addressed in the Indoor Ag-Con session “What impact can big data and automation have on indoor agriculture?”

Operations can track data that measures how fast crops have been growing compared to previous years, and which inputs those crops need at a given point, says Alastair Monk, co-founder and CEO of Motorleaf. Monk says he wants to see a future where every single grower can automatically use intelligent data to control their operations.

A question that came up at multiple points through Indoor Ag-Con and that Monk addressed is “Who owns the data?” He gave the example of a field farmer using a tractor that collects data. In his example, the farmer owns the raw data, but it is then put onto a server, mixed together with data from other farmers. Once the source of the data is no longer identifiable, the data is made accessible to third-party companies. “I think that’s probably the kind of model that indoor agriculture is going to have to follow,” he says.

Currently, automated systems control environments and crop dosing, but companies are beginning to look more at how to improve the productivity, quality and taste of a crop, says Darryn Keiller, CEO of Autogrow. And while much of this information is proprietary, he, too, would like companies to share data to make it “big.”

Keiller equates an improved system, at least in part, with predictive analytics. “Lighting strikes, stormfronts, record temperature drops, solar radiation, reduced cloud cover — all these things effect production practices,” Keiller says. “But what if you could predict those things?”

Rounding out the session was Nate Storey, founder and chairman of Bright Agrotech. He is also the chief science officer at Plenty, which recently acquired Bright Agrotech (Editor’s Note: Read about the acquisition at bit.ly/2sF5fbs). Storey spoke specifically about machine vision, which he explains as the process of using images to glean data such as size, color and changes over time.

In fact, Storey says, machine vision can tell changes over time better than a human can, as well as temperature, nutrient deficiencies, fruit ripeness and environmental conditions. This outlook may not rest easy with every grower, but Storey is confident in it. “Even [with] my eyes, my mind and all of my experience in growing plants, I’m not as sensitive to these issues as we can get with the right set of images and the right analysis,” he says.

Nine Tours Offered At The 20th Annual Detroit Tour of Urban Farms And Gardens

Nine Tours Offered At The 20th Annual Detroit Tour of Urban Farms And Gardens

MONDAY, JULY 24, 2017 | Plum Street Farm | MARVIN SHAOUNI

Detroit has an impressive number of urban farms -- over 1,500 according to Keep Growing Detroit -- a number that has grown significantly in recent years. But the the urban farm "movement" has been alive in the city for some time, as demonstrated by the fact that the 20th Annual Detroit Tour of Urban Gardens and Farms takes place August 2.

Presented by Keep Growing Detroit, patrons can take one of nine bus and bike tours organized by theme and location. For example, a west side bus tour, called "Making Institutional Change," will swing by D-Town Farm, Detroit Public School's Charles R. Drew Transition Center, and Knagg's Creek Farm to demonstrate "how farms are inspiring systemic changes in our community."

Other tours will highlight black-led farms, farms with a focus on youth development, the history of urban farming in Detroit, and more.

All the tours will begin in Eastern Market at 6:00 p.m. and last approximately two hours. Afterwards, there will be a reception with local produce cooked by local chefs.

Keep Growing Detroit, an urban agriculture organization dedicated to food sovereignty in Detroit, hopes to not only showcase these farms, but educate attendees about Detroit's food system.

"We demand healthy, green, affordable, fair, and culturally appropriate food that is grown and made by Detroiters for Detroiters," writes the organization in a press release. "Transforming our broken food system begins with ensuring there are places to grow food in every neighborhood in the city. Places where residents can dig their hands in the soil to cultivate a healthy relationship to food, learn healthy habits from family and neighbors, and nurture an economically viable city where residents are strong and thrive."

The 20th Annual Detroit Tour of Urban Gardens and Farms takes place August 2 at 6:00 p.m. Purchase tickets at the Eventbrite page.

Mahindra Automotive North America Announces Third Round Of Urban Agriculture Grants Totaling $100,000 To Six Non-Profits

Mahindra Automotive North America Announces Third Round Of Urban Agriculture Grants Totaling $100,000 To Six Non-Profits

NEWS PROVIDED BY Mahindra Automotive North America

TROY, Mich., July 28, 2017 /PRNewswire/ -- Now in its third year, the Mahindra Urban Agriculture Grant Program announced donations totaling $100,000 in funding or Mahindra farm equipment to six southeast Michigan non-profits on Thursday evening, July 27. The presentations took place at the second of three shows in the Mahindra Summer Concert Series at Lafayette Greens in downtown Detroit. These concerts build on the musical foundation laid by the Mahindra Group's Mahindra Blues Festival in Mumbai, India, which launched in 2011 and is the largest and finest presentation of legendary blues artists in Asia.

Marhindra Automotive North America executives with the Urban Agriculture Grant winners: Front row, from left: Kieran Neal (Neighbors Building Brightmoor); Lionel Bradford (The Greening of Detroit); Holly Glomski (Pingree Farms); Coleman Yoakum (Micah 6 Community) Seated on tractor: Rick Haas (President & CEO, Mahindra Automotive North America) Behind tractor: Ashley Atkinson (Keep Growing Detroit); Rich Ansell (VP, Marketing, Mahindra Automotive North America); Patti Allemon

By awarding these grants, Mahindra Automotive North America (MANA) renewed the company's commitment to this region's robust urban agriculture movement, as well as continued to fulfill its parent company, the Mahindra Group's global corporate social responsibility initiatives.

Since the program's inception in 2015, Mahindra has donated a combined total of $300,000 in cash and farm equipment to ten non-profits in support of sustainable farming and gardening in Detroit. In 2017, the Mahindra Urban Agriculture Grant Program expanded to accept applications from urban agriculture programs in Pontiac.

"The progress our urban agriculture partners are making, with assistance from Mahindra's grants, is very commendable," said Richard Haas, MANA's President and Chief Executive Officer. "I am amazed by the innovative ideas these groups present for funding. We couldn't be prouder of the impact the company's support is having on accessibility to fresh, nutritious produce at affordable prices to residents within each organization's service area."

This year's program also marks the second grant-making collaboration between MANA and Mahindra North America (MNA), which manufactures and markets the company's line of tractors and farm equipment in the United States and Canada.

Cleo Franklin, MNA's CMO/Vice President of Strategic Planning, said, "Through this urban agriculture grant we have the privilege of collaborating with our sister company in donating a tractor. The tractor will be put to good use in supporting a nonprofit organization's efforts to have a positive impact on the city through their urban farming program. Driving positive change is an inherent part of our company's culture and core values, and is reflected in the good works of these organizations."

This year's recipients and the programs the grants will support, including four that received Mahindra funding in 2015 and 2016, are listed below.

- Full Circle Foundation ($7,075): to fund a summer intern employment program for developmentally disabled teens and young adults (2015 & 2016 grant recipient)

- The Greening of Detroit ($20,000): to support the Build-A-Garden program that provides assistance to gardeners across the city. (2015 & 2016 grant recipient)

- Keep Growing Detroit ($20,000): to install technology that will enable low-income individuals and families to use government issued EBT bridge cards to buy produce and seedlings from the Grown in Detroit program. (2015 & 2016 grant recipient)

- Neighbors Building Brightmoor ($22,000): to partially fund, along with Mahindra North America, the purchase of a Mahindra tractor with attachments (2015 & 2016 grant recipient)

- Micah 6 Community ($8,000): to build a 2,000 square foot greenhouse at the Webster Community Center in Pontiac. (1st year recipient)

- Pingree Farms ($26,010): to purchase a Mahindra tractor for use at the 13-acre farm site. (1st year recipient)

"Mahindra is committed to lifting up and celebrating the communities in which we operate," said Anand Mahindra, Chairman of the Mahindra Group. "There are few better examples of our RISE philosophy in action than the work Mahindra Automotive North America is doing in Detroit. MANA's pioneering Urban Agriculture Grant Program continues to lift up Detroit residents by giving them access to fresh, sustainable produce and inspiring work opportunities for the underserved."

Mr. Mahindra continued, "Also, MANA's new summer music series celebrates creative expression and community-building in the Motor City. To see these two initiatives working harmoniously is to truly know Mahindra."

An estimated 1.2 million pounds of fresh food have been grown and distributed to Detroit residents through the efforts of the groups that received Mahindra grants or equipment over the past two years. Among other outstanding results, the company's donations supported the opening of a Garden Resource hub in Southwest Detroit, and the purchase of a delivery vehicle to support the entrepreneurial efforts of the Full Circle Foundation's trainees at the Edible Garden.

About Mahindra Automotive North America