Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

A Q & A With The Urban Farmers Behind Farm LA

A Q & A With The Urban Farmers Behind Farm LA

On Their Obsession With Lima Beans And Their plans To Plant Gardens On Abandoned Properties

BY JENNA CHANDLER@JENNAKCHANDLER MAR 24, 2017, 9:30AM PDT

Arlan J. Wood and Emily Gleicher, with their dogs Buck Rogers and Ham Hock, at home in Frogtown.

Every piece of Emily Gleicher and Arlan J. Wood’s yard in Frogtown is used for gardening. The couple grows a myriad of produce, from white sage to sunflowers to strawberry corn to dragon fruit to the most detested vegetable of childhood: lima beans.

The bounty supplements their diet. They make popcorn, salads, citronella oil, and hot sauce, which Wood has named “Caliente Culo.” But it’s the lima beans that help support Farm LA, the nonprofit they founded in May 2015 to turn abandoned and derelict lots into urban gardens for neighbors to enjoy. They sell the legumes in mason jars at farmers markets along with recipes for mashed lima beans and lima bean hummus.

Their love for gardening started after Gleicher relocated from New York City to Los Angeles. She was happy to get away from the cramped, dense neighborhood of Greenpoint, so they took full advantage of their yard in Northeast LA. Gleicher also quickly took notice of the empty lots dotting their neighborhood.

“There are quite a bit of unbuildable hillsides, quite a bit of yucky abandoned properties. We know it’s challenging to fill those properties, because they have their imperfections,” she said. “Why not do something cool with it?”

Gleicher and Wood invited us to their home on a drizzly Tuesday morning. We sat on the porch and talked about how the city might encourage more urban farming, why they love lima beans so much, and their (sometimes emotional) quest to find more land.

Why Lima Beans?

Gleicher: On our first Valentine’s Day, J., in cute-, fresh-, and frantic-boyfriend-mode, at the last minute went to CVS and got me barrettes, and a card, and a lima bean plant that, when it sprouted, said “I love you.” It never actually did sprout that way. That fueled our gardening mode. Our garden was in the works, and when he got that plant for me, we realized lima beans are drought tolerant. We love to grow them on teepees; they trellis up in really fun ways.

All of our lima beans are all from that one plant—every lima bean that’s in our kits. We’re probably third generation at this point.

So a lima bean plant from CVS kickstarted this operation?

Gleicher: We were already starting to fall in love with gardening and we were wanting to do something with the space we were seeing around LA. And, everyone kept telling us when we started, “You’ve got to have a product. You’ve got to have a business plan.” And we were like, “What do you mean? We’re nonprofit!” The lima beans help sustain our nonprofit. It’s not paying us. But it’s paying for snacks for our volunteers. The goal is to get larger spaces so we can grow more lima beans.

A row of potted apple trees in the side yard.

You recently spoke at a city commission meeting to advocate for the city of LA to adopt urban agricultural zones. What are those?

Gleicher: We’re a part of this urban agriculture working group that is run by the Los Angeles Food Policy Council. The council is all about food justice in LA, whether it’s legalizing street vending or keeping food accessible for lower income neighborhoods.

One thing they’re trying to push forward is the Urban Agricultural Zone Act. This act would give property tax breaks to land owners in the city with nothing livable on their parcels—if they partner with farmers like us or if they themselves start using those plots for urban agriculture, which can mean different things, so we’re working to define that with the food policy council.

Wood: There are plots everywhere, plots that are empty. A lot of that is due to red tape. For the Average Joe homeowner, they’re not really usable. So this would give an awesome incentive for them to go, “Oh my gosh, yes, take my hillside for blank number of years.” It saves them a lot on property taxes, and it’s a win-win for everybody.

So you have a list of properties that you’ve been scouting to turn into small farms, right?

Wood: We’ve been going to property tax auctionsfor a few years now.

Gleicher: It’s usually families who unfortunately can’t pay the property tax for whatever reason, and it goes to auction. We’ve found a few and gone but got outbid. It’s a touchy subject. It gets a little tearsy.

Wood: We invest a lot of time looking for the properties.

Gleicher: There was one in October and I think the titles will be public record soon for whoever did win it, and when this act is officially on the books and we can move forward, we want to go to those people, and say, “Hey we know you purchased this property in the auction. If you’re having a hard time building on it, please think of us.”

How else are you finding land?

Gleicher: People reach out to us. Some things we’ve had to say no to, because they’re not really in line with what we’re trying to do, like a property in Laurel Canyon. We want somewhere close to us. But it’s really about trying to stay in a food desert neighborhood, in a low-income neighborhood, a neighborhood that needs beautification. It’s more Northeast LA, and Boyle Heights, and Cypress Park, and Glassell Park.

I imagine someone might contact you to say, “Hey, there’s a vacant plot of land on my street, come plant a garden here.” Great. But maybe you can’t get ahold of the property owner. What other roadblocks are you hitting?

Wood: We’ve tried to do that several times, and it’s a doozy.

Gleicher: It’s public information, so it’s not so much that as it is getting people to get out of their comfort zones and do something that feels out of the norm for them. Some people are against change, some people are against bringing beauty to a neighborhood, because they think it brings other changes, like gentrification. So we’ve experienced a touch of that, too, and understandably so.

How do you convince property owners?

Gleicher: I go for the heart strings: “Wouldn’t you rather see something that can feed a community?”

Wood: “Or beautify a community?”

Gleicher: “Or feed a women’s shelter? And enrich your soil? Nothing is permanent. We’re not planting oak trees. If you ever want to change something, which we hope you wouldn’t, this could all be relocated or transplanted.” We need to work on our elevator pitch, but each property is so unique.

Lima beans could/should be the new kale, says Gleicher.

Tell us about the gardens you have already and where the food goes.

Gleicher: We have 11.5 sidewalk gardens now. (The .5 is a giant fig tree at Cafécito Organico in Frogtown.)

Wood: Soon to be 12. (The 12th will be a patch of barley planted at Frogtown Brewery.)

Gleicher: In the residential areas, the food is for the block. The person providing the water certainly gets first dibs. But it’s to share with neighbors. It’s on them to take care of it. The spirit of this is, “this is for you, take it.” Eventually we want to put in signs that tell you how to take care of it and what each plant is. But for the most part it’s a little wild west right now.

For anyone who now feels inspired to start growing something, what do you recommend?

Gleicher: Herbs. Peppers. Lima beans do really well for us. I know. It sounds like we’re obsessed. But we are.

Canada’s Prime Minister Trudeau Visits Rooftop Lufa Farm

With the completion of its 3rd high-tech greenhouse, and its symbiosis with local farmers, Lufa Farms has grown into a compelling role model for sustainable urban agriculture.

Canada’s Prime Minister Trudeau Visits Rooftop Lufa Farm

Mar 24, 2017, 17:31 ET

With the completion of its 3rd high-tech greenhouse, and its symbiosis with local farmers, Lufa Farms has grown into a compelling role model for sustainable urban agriculture.

MONTREAL, March 24, 2017 /PRNewswire/ - Urban agriculture pioneer Lufa Farms has just finished a third highly automated greenhouse in the Montreal borough of Anjou. The Right Honourable Justin Trudeau was there to see it in full production.

The new 63,000 square foot rooftop greenhouse is a milestone in polyculture efficiency and produces over 40 varieties of urban-grown greens and vegetables, all year round. Lufa Farms' six years of rapid growth and its successes in rooftop greenhouse design, cooperation with local sustainability-focused farmers, and appeal to thousands of Montreal consumers, make it one of the most successful large-scale urban agriculture models in the world, demonstrating how to sustainably feed entire cities.

The Prime Minister was given a full tour of the new production facility by Lufa Farms founders Mohamed Hage and Lauren Rathmell. He witnessed first-hand the innovative complexity of the rooftop greenhouse, and even took time to harvest a basket of fresh greens for himself and his family.

The new rooftop greenhouse is a marvel in automation. It was designed by Dutch greenhouse innovators at KUBO, outfitted by Belgian greenhouse automation experts, Hortiplan, and includes advanced horticultural lighting systems from GE.

The construction of the new greenhouse was supported by Quebec financial partners Fonds de solidarité FTQ and La Financière agricole du Québec.

From one rooftop greenhouse to a new paradigm in urban agriculture

Lufa Farms began operating the world's first commercial-scale rooftop greenhouse in 2011. It was built with the goal of using sustainable irrigation, energy and growing systems for cultivation of pesticide-free produce. The first greenhouse, with 8 employees, produced more than 25 varieties of vegetables and delivered them, weekly, to a few hundred Montreal consumers.

The second Lufa Farms' rooftop greenhouse began operation in 2013. With it, the company introduced an online marketplace so that consumers could select and buy fresh Lufa Farms produce together with responsible produce, meat, dairy, bread, and more provided by hundreds of local farmers and foodmakers. The result is that consumers receive the freshest sustainably-grown goods, local farmers get a viable outlet for their products, and the city benefits from optimized land, water, and energy use.

A disruptive rethink of food production and distribution

The most recent greenhouse caps six years of steady growth and innovation. The Lufa Farms team now consists of more than 140 employees, grows over 70 different vegetable varieties, and delivers more than 10,000 food baskets every week of the year.

"We began this venture because of our passion for rooftop farming. We didn't start out as farmers and I'd never even grown a tomato before," says Lauren Rathmell, Co-Founder and Greenhouse Director of Lufa Farms. "But we did what made sense to us as technologists and problem solvers. Today, we understand that successful urban agriculture requires not only advanced greenhouse technology, but also direct-to-client distribution, and working together with local, sustainable farmers and food artisans. The sum of all the parts, working together, is greater than the whole."

The future of Lufa Farms

Founded in 2009 by Mohamed Hage, Lauren Rathmell, Kurt Lynn, and Yahya Badran, Lufa Farms now has acombined urban growing space of 138,000 square feet. The company plans to continue the expansion of its urban farm projects in Quebec urban centres, and also in select New England locations in the U.S.

For more information about Lufa Farms click here. For images of Lufa Farms and the Prime Minister's visit, see the Flickr album.

SOURCE LUFA FARMS

Related Links

Three Ways To Urban Agricultures: Digging Into Three Very Different Offerings From Three New Books

Three Ways To Urban Agricultures: Digging Into Three Very Different Offerings From Three New Books

By Wayne Roberts

When Socrates, Plato and the gang had their dialogues about the inner essence of beauty, truth and justice, while hanging out at the farmers market in downtown ancient Athens, they had no idea of the problems they would create for urban agriculture 2500 years later.

Unfortunately, urban agriculture is still all Greek to many city planners.

That might seem like a stretch, but give me a chance to make my point. The ancient Greeks established the pattern of looking for absolute and universal Truth in the singular. The simplest way to see the legacy of this tradition in today’s thinking about food is to look at all the single-minded words. Think of such commonly used expressions as food policy, food strategy, food culture, local food, sustainable food, alternative food, and urban agriculture. Not much pluralism, plurals or variation here!!

We betray the Greek origin of western styles of thinking every time we use the singular to discuss potential options with regard to the abundance of foods and food choices that urban lives and modern technologies provide (please note my use of the plural).

So, for example, we have city discussions about the need for a city policy on urban agriculture, instead of city discussions about the need for city policies to support various forms of urban agricultures.

The ancient Greek philosophers, despite many wonderful ideas they developed, were hung up with locating the one and only essence of things — an abstraction that was independent of the ups and downs of momentary appearance.

They didn’t like messy realities because they were too messy, and left that world to slaves and women. That tradition is still alive and unwell, as the low wages and standing of agricultural and food preparation work shows. The jobs that pay well are jobs removed from messy realities.

Likewise, to this day, a narrow and absolutist mindset straitjackets our thinking about food policy in cities.

Alfonso Morales edits new book on many forms of city farms

To wit, the way cities agonize over a policy (note the singular) for urban agriculture (note the singular), rather than a suite of policies (note the plural) to help as many who are interested, for whatever reasons (note the plural), be they love or money, to eat foods (note the plural) they have grown or raised or foraged in varieties (note the plural) of spaces (note the plural) — from front yards, to back yards, to green roofs, to green walls, to balconies, to windowsills, to allotment gardens, to community gardens, to beehives, to butterfly gardens, to teaching and therapeutic gardens, to edible landscaping, to soil-based, hydroponic and aquaponic greenhouses, to vacant lots, to public orchards, to community composting centers, to grey water recycling for lawns and gardens, to formally-sited farms and meadows.

LET ME COUNT THE WAYS

There are so many opportunities, so many points on the urban agricultures spectrum, that we can’t even say “urban agriculture is what it is.”

That fact is that “urban agricultures are what they are,” and city governments in different areas should embrace many of them.

Of course, public authorities need to practice their usual due diligence in terms of personal and public safety, but the emphasis of policy should not be on toleration or permission, but management and stewardship of the health, environmental, community and economic yields of urban ag.

Janine de la Salle’s wake-up call

This is in marked contrast to the present mode of civic management over urban agriculture. City food planning advocate Janine de la Salle, who has the fortune to work in Vancouver, which is an exception to the rule, describes the norm as one where officials need a wake-up call because they’re managing urban agriculture in the same passive way they manage sleep, another essential of life. Like sleep, urban food production is treated as “necessary, but not meant to be regulated or managed in any meaningful way,” she writes in her chapter in the book Cities of Farmers.

That nice little dig (there are many ways to dig in support of urban agricultures) brings me to the business at hand in this newsletter, a review of three fairly new resources (two books, one assortment of essays) on urban agriculture — each of which sheds a distinctive light on the growing possibilities of urban food production.

VIEWS FROM MADISON

The best to begin with is the collection edited by Julie Dawson and Alfonso Morales, called Cities of Farmers: Urban Agricultural Practices and Processes. It sets the stage.

Horticulture expert Julie Dawson co-edited Cities of Farmers

The two editors come from the state university in Madison, Wisconsin, where the late city planning authority, Jerry Kaufman, spread his protective wings around a new generation of urbanists who now teach and practice city food planning around the world. Before Kaufman, the conventional wisdom of city planners was that food was produced in rural areas and consumed in cities; cities should stick with making things that provided the “highest use” of expensive city land. This anthology, which breaks totally from convention, is a worthy basket from the harvest Kaufman seeded. (To be transparent, I am as indebted to encouragement from Kaufman as any of his students.)

Jerry Kaufman, godfather of city food planning

To be more transparent, I got to see this book before it was published, so I could write a back cover blurb drawing attention to its “down to earth quality” that can help city planners, health promoters, community developers and “all who love what a garden does for a day outdoors, a yard or parkette, a great meal, and quality time with others.”

The breakthrough of the book, in my view, is that it doesn’t ask the ancient and unanswerable philosophical question about “what is urban agriculture.” Instead, it asks the more pointed and fruitful question: what do urban agriculture projects do.

The book’s answers (note the plural) form the most comprehensive overview yet of how the “multi-functionality” of both agriculture and food can generate the many benefits that urban agricultures bestow on cities.

Producing food may well be the least accomplishment of urban agriculture, though that extra food can really make a difference for people on low income. But the crop itself is only one contribution on a long list that includes enhanced public safety, community vitality and cohesion, neighborhood place-making, skill development, food literacy, garbage reduction (through composting) and green infrastructure.

down to earth look at urban ag

As Erin Silva and Anne Pfeiffer argue in their chapter on agroecology in cities, the sheer range of benefits bestowed by urban agricultures dwarfs the efficiency of any one particular contribution — be it food production or the development of community food literacy. This knocks the economic analysts for a loop because the premise of this book is that the whole is greater than the part, and the efficiency comes out of the whole, not any one part. “Though food production remains a central focus for many operations,” they write, “ it is often a means to achieve other social benefits rather than the singular goal.”

As I used to put it during my working days at the city of Toronto, the success of all forms of food activities, including urban agricultures, rest on the economies of scope, not the economies of scale.

Therein lies the key to measuring true productivity, and when we understand why that breakthrough method of measuring progress in food matters, we will come to see the potential of totally different methods of managing and incentivizing food activities.

HOW DO YOU GET TO GARDEN AT CARNEGIE HALL? PRACTICE!!

Though I like all the essays in the book, the one that knocks my socks off is by Nevin Cohen and Katinka Wijsman. It highlights the central role of food practices in a way that points to new ways of promoting food activities that go far beyond the boundaries of urban agricultures. (Are you becoming more comfortable with all the plurals?)

Nevin Cohen, co-author, practices looking like a gardener

This essay is fundamental to anybody who want to make the journey from food policy to implementation of new food practices.

I never had a policy of brushing or flossing my teeth after a meal. But sometime before I remember, I learned the practice of brushing my teeth — though I learned the wrong practice that was standard in my day, of scrubbing up and down and side to side, not gently brushing up or down from the gums to prevent gum damage. Unfortunately, I didn’t get the practice right in time to save my gums from painful and expensive dental work, which also instilled in me the practice of flossing. At this point, flossing is no longer a policy decision I make, but a practice I follow “automatically.” That norm of “practice”is one followed by people who practice anything from medicine to yoga, and we now need to normalize it in good food practices. As medicine, yoga, Cohen and Wijsman make clear, policy is the servant of practice, not the other way around.

Their essay reviews how New Yorkers went from policy advocacy to practices that implemented community gardens. They not only normalized community gardens on the most expensive real estate in the world, they incorporated forms of urban agricultures into the basic infrastructures of a city — from green roofs and walls to green paths and street greenings that manage stormwater.

The gardening version of pilgrims’ progress in New York City has been as much about advancing practices as policies, Cohen and Widjsman argue.

Indeed, practices need to become the a lens for all people who seek meaningful food system changes in food. Part of the thinking behind a city establishing a food policy council or urban agriculture sub-committee is to provide an institutional focus for the new civic practice of automatically saying “we can do our due diligence on food practices by referring this issue on (whatever) to the food policy council and urban ag committee, and asking if we overlooked any possible food enhancements.”

We have come full circle from Plato and the ancient Greeks, who saw theory as the exemplar of purity, not defiled by the shadows in the caves that people lived in. This is why we now need to refer to people who get the new paradigm of meaningful change as “communities of practice.”

Developing such communities is the way we build vehicles for food system transformation, just as people who practice yoga or medicine or meditation work their changes.

When you have finished this book, you will be mentally ready for the latest practices from one of the master practitioners of organic food production.

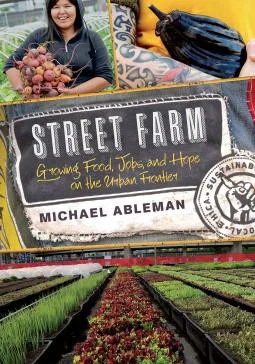

ABLEMAN’S ABILITY

Michael Ableman is one of the preeminent growers, photographers, speakers, writers and entrepreneurs produced by the global organic movement. He was able to bring all these mature skills and practices to the most delicate, fragile and responsible project of a lifetime — cultivating the skills and practices of 25 employees from Vancouver’s notoriously drug-ridden Downtown East End to the point where they tended five acres on four beautiful and productive food gardens. Urban agricultures don’t get much grittier than this. Ableman’s book, Street Farm: Growing Food, Jobs, and Hope on the Urban Frontier, tells the story.

Street Farm goes beyond-down-to-earth; it’s down to pavement

There was no utopian vision — it takes a practiced hand to know to steer clear of that — but Ableman and his crew “wanted the world to know that people from this neighborhood, those who were viewed as low-life losers, could create something beautiful and productive; that they could eat from it, feed others, and get a paycheck from its abundance; and that it could sustain itself for more than a few days or weeks or months or years.”

If urban agricultures can accomplish something akin to that, city gardens can produce something every bit as essential as food. This is what people-centered food policy is about.

Devoted organic grower and foodie that he is, Ableman digs the people-centeredness of this urban agriculture project. Employing and enabling the neighborhood farm workers is the mission of the street farm, he writes, citing the Japanese farm philosopher Masanobu Fukuoka who insisted the “ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation of human beings.” He came to regard his fellow workers as “farmily.”That does put urban agricultures in context, and explains why land-use policy for urban agriculture deserves to be classified as among the “highest uses” of urban land.

Ableman also understands that urban agriculture is not just rural agriculture in a city. It sometimes has to be adapted in stark ways. He came to understand, for example, that a paved parking lot was an ideal foundation on which to build, and that the best way to grow was in some 5000 wood and plastic bins (almost 10,000 at the time of this writing), which can be moved when a lease or a welcome run out.

Does Abelam see urban ag as another way to bring art to the people?

He also understands the centrality of partnerships and of champions on city staff to his success; they are the city farmer’s environment, as important and immediate as nature is to the rural farmer. At one point, he even argues that the crisis of global industrial agriculture is, above all, “a crisis of participation” — which distances people from their food as much as the 5000 mile trip that Asian rice takes to a plate on the eastern seaboard of the Americas.

WHAT HUMANS HAVE IN COMMONS

Ableman’s understanding of the centrality of engaging the human side of food production (should we call it human-centered food policy?) is the segway to the third body of work considered in this newsletter on urban agricultures — the work of Chiara Tornaghi at Coventry University in England.

As I read her articles, Tornaghi is so bold as to put our psychic needs of our deeply-rooted human spirit on par with deeply human physical needs for food — and thereby to classify citizen access to urban food production as essential. Only such a deep understanding of the need to engage with and participate in food production could account for her proposal that access to food production opportunities be classified as part of a citizen’s inborn and inherent “right to the city.”

Gardening activist Chiara Tornaghi and her assistant

Tornaghi’s work is accessible in a variety of places — including one article on how to set up an urban ag project, and one pieceon the critical geography of urban ag, and one study on urban ag and the politics of empowerment, and one reporton gardening activism, as well as a publication on European urban agriculture.

She’s pretty much out there, with phrases such as “insurgent urbanism” and “politics of engagement, capability and empowerment,” along with references to the commons, metabolism and other clues that Tornaghi has spent as much time in obscure sections of libraries, as in gardens.

At the very least, she is refreshing. People concerned about the runaway rates of mental ill-health among young people cannot ignore what she has to say about addressing human needs to work directly in nature — and thereby counterbalance the highly built, urbanized, synthetic, abstracted, impersonal, mediated and corporate-controlled environment of dense cities.

In my view, this mental health and well-being perspective is the most urgent and compelling reason for city planners and managers to listen up on the subject of urban agricultures.

I don’t want to gild the lily of what she has to say. There are calls to action from earlier times that call for direct action, by which was meant “take power into your own hands, and come to a demonstration calling on someone else to do something.”

By contrast, Tornaghi’s is a direct action call to meet with your neighbors, find a place to stand, dig in, and get your hands in the dirt. It deals with justice not just as a distributive matter — how to divvy up the harvest so the one per cent don’t get almost all of it and the poor get little — but a capability matter: the right of people to develop their capacities and not have to settle for a consuming life that renders us spectators of our own lives.

WE ARE WHAT WE GROW

Steven Bourne of Toronto’s Ripple Farms finds himself and a job

You shouldn’t have to leave the city to get in touch with your deeper self.

Tornaghi’s is a shout-out to go beyond the civic benefits that urban agriculture provides a city to the human benefits food production bestows on that undomesticated “gardener” and “forager” part of our inner being, brain, mind and soul. If that is not well, then life in cities cannot be good.

Although there is huge wisdom in the clichéd phrase about “we are what we eat,” we now need to recognize that we are just as much what we forage and grow and make. We are also what we grow and produce. We evolved to eat in certain ways, and we also evolved to feed ourselves. The two are inseparable. The two were severed by industrial agriculture, which turned most eaters into consumers. Now we need to heal that breach.

Urban agriculture is the ultimate offering that food makes to people in cities — not what has long been considered the punishment of hard labor, meted out to humans as penalty for their sins, but what is really food’s greatest gift — the opportunity to engage and participate in the labor as well as the joys of meaningful work.

SALAD DAYS OF CITY FARMING

I’m look for a fourth book to round this picture out, a book that captures the energy of a new generation of city farmers who are growing salad greens in freight containers repurposed as greenhouses. They can fit into any number of small places and provide conditions for growing fish (aquaponics) and greens (hydroponics), together or separately.

Brandon Hebor

Like Steve Bourne and Brandon Hebor of Ripple Farms in Toronto, these ecopreneurs repurpose old freight containers, rescuing them from landfill, outfit them with grow lights and containers for fish and plants, and locate them in an out-of-the-way but accessible space (in this case, just by the parking lot of the popular Brickworks farmers market) where the 100 yard diet applies to producers and shoppers.

They can grow microgreens and fish, and they can grow micropreneur jobs by the tens of thousands — with a potential for each micro-green micro-business to supply one farmers market, or one food truck, or one school meal program, with fresh-grown greens and fish from the neighborhood.

Talk about a disruptive business model that will affect the way people can access ultra-local fresh greens and fish for 12 months of the year!!!!! They’re so close to their customers, they don’t even need to call Uber for deliveries!

Indoor ag is just one of the many ways that the many forms of urban agriculture can benefit cities. There are many more to put in the urban ag bucket list.

(Wayne Roberts also produces a free newsletter on food and cities. It links readers to all his publications, and provides other timely information from the field. To sign up, go to http://bit.ly/OpportunCity)

How Urban Farming Took Root Everywhere

HOW URBAN FARMING TOOK ROOT EVERYWHERE

Published On 03/22/2017

Chicago’s Back of the Yards neighborhood was once one of the most industrialized areas in America, where stockyards and factories were manned by thousands of working-class immigrants. It’s the setting of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. But today, inside a 93,500-square foot former meatpacking plant there, kale, swiss chard, tomatillos, and oregano grow in vertically stacked trays, nourished by water from a nearby tank of tilapia. There are two additional hydroponic farms growing greens, plus a brewery, bakery, a mushroom farm, an artisan cheesemaker, honeybees on the roof, and a fresh flower farm. In total, there are 12 food-producing tenants in the gigantic, industrial space.

Unlike the neighborhood’s original pork-based economy, this new microscale ecosystem is working towards conducting business without letting a single item go to waste.

“IT IS MUCH MORE THAN AN URBAN FARM. IT’S KIND OF LIKE A MOVEMENT, OR A WEIRD EXPERIMENT.”

The Plant, as the facility is known, is considered a “collaborative community of food producing businesses” that work together inside the former meatpacking plant to not only grow and produce food -- but to create a “closed loop” system for energy, waste, and materials. Meaning that everything is reused: spent grains from the brewery are formed into briquettes to fuel the bakery ovens, coffee grounds from the roastery inside are used to help nourish the mushroom soil. At The Plant, that closed loop system is managed by not-for-profit group Plant Chicago.

Plant Chicago staff also teach the public about this closed loop, circular economy through tours, education programs, and a year-round farmer’s market.

“It is much more than an urban farm,” Kassandra Hinrichsen, education and outreach manager for Plant Chicago says. “It’s kind of like a movement, or a weird experiment.”

It’s not just about providing fresh vegetables

The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations reports that 800 million people practice some form of urban agriculture worldwide, even though it’s illegal in several countries. The USDA doesn’t keep formal stats on urban farming in the United States, but in 2016 it funded about a dozen urban farms, the largest in the agency’s history, according to Business Insider. Even more loans and grants are expected to be given out to urban farmers in the United States this year.

But urban farming isn’t a new phenomenon for America’s cities. In the 1970s, community gardens sprang up in vacant lots in New York City, Chicago, Detroit, and San Francisco -- providing not only a place to grow fresh vegetables, but also a way for urban communities to organize. In 1993, Will Allen purchased a piece of land in Milwaukee so he could sell vegetables from his nearby farm to people in the North Side neighborhood. He then started farming food right in the city -- a project that would become Growing Power, one of the first urban farm projects in the country. In 2009, the Eagle Street Rooftop Farm in Greenpoint opened, becoming New York City’s first commercial rooftop farm. But in the eight years since, as more people have a desire to eat local foods within urban areas, the trend has stretched far beyond Brooklyn.

An increasing number of farms are taking on innovative projects that do much more than just provide food. Like Plant Chicago, for instance, which is charged with researching ways to reduce waste and reuse it at the farm, as well as conducting outreach with the neighboring community.

One of the largest endeavors, which is the brainchild of The Plant’s founder, John Edel, will be to use an anaerobic digester tank to heat the entire facility, rather than electricity or gas. Once it’s online, the energy system will be able to process 30 tons of food waste a day in the same way a human stomach does. It will break down the waste into liquid, biogas, and a high-nutrient solid. The solid and liquid will be sold to soil companies as a compost, while the biogas will be used to heat the building.

Plant Chicago staff and volunteers are also responsible for maintaining the aquaponics farm at The Plant -- a system where plants grow in water and receive the nutrients they would normally get from soil via waste created by fish. The plants, in turn, filter the water for the fish. This sort of farming has become increasingly popular in Chicago, with several for-profit and non-profit farms popping up around the city, in everything from warehouses to classrooms.

“In Chicago in the last couple of years, there has been a crazy bump in indoor farming, like hydroponics and aquaponics facilities,” Hinrichsen says. “Hopefully, indoor farming and those kinds of systems are becoming more accessible to folks, because the point of Plant Chicago is to be open sourced as well, and to show that you don’t necessarily have to have a bunch of money and crazy investors and a business degree to start something like this.”

Farm-to-table is eating better, which is the best way of living better. Fresh food will revitalize your spirits as well as your body -- even in the heart of a city. To reward yourself for living so well, open a bottle of Strongbow cider, and let the crisp and refreshing orchard taste come to you.

What we can grow in cities, and how we use it, is changing

Elsewhere, in Chicago, another company looks to turn the city’s world-famous architecture green.

Thanks to the laughably high prices of land in some cities, urban farmers looked to city roof tops as a potential growing site for their farms early on. But, while they may be more affordable, growing edible crops on a roof comes with it’s own set of problems.

“If you’re trying to grow food in a completely foreign environment, where you don’t have nutritious substates, when you don’t have reliable water, when you have extreme temperatures -- extreme cold and extreme heat -- that’s like Mars, and that’s pretty much what it’s like to grow on a rooftop,” says Molly Meyer, the CEO and founder of Omni Ecosystems, a green roof company based in Chicago.

Meyer’s company developed a green roof system that could allow plants to thrive, despite the harsh conditions. Their green roof technology supporting edible crops is not only lightweight, but includes intuitive irrigation systems. Automated watering systems are linked up to weather stations or rain sensors, to make sure the crops aren’t being watered when rain is in the forecast.

Meyer founded Omni Ecosystems in 2009, but she had worked with green roofs for years previously, and installed her first green roof in 2006 atop True Nature Foods in Chicago. She continued studying green roof tech in Germany as a Robert Bosch Fellow. Germany implemented green roof technology decades back, so Meyer’s experience there amply prepared her to start a company in the United States.

Omni has installed dozens of green roofs from Boston to San Francisco, as well as the vertical gardens known as “living walls” and subterranean barriers so that crops may be planted safely above contaminated earth. It also manufactures its own soil. But at first, Meyer says the trend was slow moving -- thanks in part to how long it takes for buildings to be designed and constructed.

“The construction industry, and the building industry in general, is very slow industry to change,” she says. “It takes maybe a year to design a building, and a year to build a building. And so, you have a couple years just for one site to change over. Now, we’re really starting to get a clip going. We’re starting to see some snowballing effects. People have seen the technology now, they are recommending and referring it, and applying it.”

Most of their edible crop rooftop farms produce the usual stuff: leafy greens, tomatoes, peppers, etc. But, just last year they were able to grow an entire wheat field in the middle of downtown Chicago -- and it was practically unintentional.

Omni was hired to build a native wildflower meadow on top of the Studio Gang Architects’ rooftop on Division Street. But the construction schedule was pushed into the fall, forcing them to grow a hardy annual plant that could protect the soil. They chose winter wheat, with no intention of harvesting an entire rooftop of the stuff.

“Then, we came back in the spring and lo and behold, there was a wheat field in the middle of downtown Chicago,” Meyer said. “I don’t think any of us were expecting to see a wheat field 40 feet up from one of the busiest intersections in Chicago.”

They enlisted Omni’s sister company, the Roof Crop (which Meyer also co-founded), as well as student volunteers, to harvest the 3,000 square feet of wheat by hand. A nearby miller donated his time and milled the harvested wheat into about 60 pounds of high-grade pastry flour. (He even rewarded the students with cookies.)

But besides the experience, Meyers was able to walk away with a clear ratio for how much wheat can be produced on a rooftop: for every 50 square feet of green roof that’s harvested, they’ll get about a pound of flour.

“Now that we have that metric, we can start looking at cities in completely different ways,” she said. “When building owners need just another incentive to do the thing that is great for a city -- bringing plants to a city -- this is one that can now be measured. We can say, ‘well, actually, if you chose to do wheat, and you harvested it for 20 years, every year you would get X pounds of flour, which could turn into X loaves of bread, or X bottles of beer."

Urban farming extends to food deserts... and real deserts

In South Phoenix, there isn’t a regular farmer’s market, and getting to a grocery store can mean a serious trek. That means the 4,711 residents in this part of town don’t have access to fresh fruit, vegetables, and other healthful whole foods. The area is officially designated a food desert by the USDA, but one project, called Spaces of Opportunity, is planning to change that.

With the help of several area nonprofits known as Cultivate South Phoenix, the Desert Botanical Garden, and a local elementary school, 18 vacant acres in the region are set to become working farmland and a community center for arts and healthy living programming.

“The whole point of the project is to keep as much healthy produce in the community as we possibly can,” says Nicolas de la Fuente, the project’s manager.

Eighteen acres is roughly the size of two New York City blocks, and 9.5 acres will be divided into “incubator farms.” Those spaces will be used as production farming space for people who want to make a serious living off the food they grow. Then, there’s 1.5 acres of community garden space, with plots that are about 4ft x 50ft.

“It’s funny when I say ‘community gardening,’” de la Fuente says. “At 1.5 acres it’s almost rural farming, it’s not like the boxes you see in other cities.”

There are currently four incubator farmers growing and selling winter vegetables, like spinach, collard greens, and kale, in the space. In the next few months, they will switch over to summer season crops: squash, peppers, tomatoes, and watermelons.

To water the crops, de la Fuente says they are planning to install a drip irrigation system. That will help the farmers conserve water, as well as substantially increase their output. Despite the desert conditions, the area was also once rich farmland, known for growing citrus and flowers. The Hohokam Canal system, which was one of the world’s largest canal systems, ran through the area, too.

“It’s actually a super rich agricultural center, that’s just been little by little developed with infill,” de la Fuente says. “So we aren’t necessarily doing anything new. We’re just essentially trying to bring back what was there and embrace the roots of the community.”

Spaces of Opportunity just received enough funding to fully connect to water and power, and their next endeavor is to build out the farmer’s market -- which will be the first in South Phoenix.

There’s still more work to do

Annie Novak has been the farm manager at Greenpoint’s Eagle Street Rooftop Farm in Brooklyn, NY since 2010, and she planted the first seeds on the farm with Ben Flanner in 2009. Since she became farm manager, she’s taught 100 people through an apprenticeship program who are looking to start an agriculture project of their own -- be it starting a small garden on top of their restaurant, or raising grass fed cattle in Texas.

“There’s a lot going on around the country, and internationally,” Novak says. “I feel like New York City leads with press, but I don’t know if we lead with acreage or initiative. Chicago, Detroit, San Francisco, LA to a degree, Milwaukee, Austin -- these are all places that have really successful urban farming programs. So we definitely are not alone.”

While farming is clearly a hard job, Novak says operating a farm in a city provides a lot of opportunities. They are close enough to their markets to meet buyers face to face. There are several restaurants seeking out fresh produce, and there are minimal transportation costs.

Besides the expansion of urban farming, one of the most vital changes she’s seen is that cities, and even the USDA, are beginning to support these initiatives. Urban farms are also getting included in conversations about the importance of green spaces in cities, and in particular how to protect them.

“There always seems to be an ebb and flow in the way cities embrace urban agriculture,” she says. “So I’m just trying to think ahead. What happens when everyone who started a rooftop farm when they were 22 decides they want to know what’s next?”

To protect the work that’s already been done, Novak hopes that cities like New York will start zoning some urban farms as agricultural property, which would ensure that the area remains a space for farming. In New York, there’s only one agriculturally zoned property: The Queens County Farm Museum, and it’s been a working farm since before New York City even existed.

“Why has nobody ever turned Central Park into a condo?” Novak asks from her bike, which is her sole form of transportation around the city. “Well, there are legal reasons why. But we could do the same thing for farms.”

Detroit Turned Blighted Properties Into Urban Farming

Image: Pixabay

Recovery Park is providing a place for ex-offenders, recovering addicts and others with barriers to employment a chance to gain work experience.

Editor’s Note: As of February 2017, the project continues:

By Mary Velan

EfficientGov – Originally posted November 3, 2015

The city of Detroit is teaming up with RecoveryPark to transform a blighted 22-acre area on the city’s lower east side into a center of urban agriculture. The goal of the project is to provide a place for ex-offenders, recovering addicts and others with significant barriers to employment with an opportunity to gain valuable work experience.

The Project

The 60-acre project – which includes more than 35 acres (406 parcels) of city land – is designed to revitalized one of Detroit’s blighted neighborhoods by repurposing vacant land. The city is collaborating with RecoveryPark, a nonprofit organization working to create jobs for people who struggle to get hired.

“RecoveryPark isn’t just about transforming this land. It’s about transforming lives,” Mayor Duggan said. “The city of Detroit is proud to support the work Gary Wozniak and his team are doing to put this vacant land back to productive use and to help ex-offenders and others with barriers to employment rebuild their lives.”

The project is expected to employ 128 individuals within three years, 60 percent of who will be Detroit residents. Consistent with its mission, most of RecoveryPark’s workers will be ex-offenders, veterans and recovering addicts.

The RecoveryPark project wants to leverage Detroit’s underutilized assets while developing a for-profit food business – RecoveryPark Farms – in the local community. To help the project take root and grow, the city is allocated $15 million to the initiative.

Veterans, returning citizens, challenged workers, those in recovery and other marginalized citizens struggle daily for the ability to care for themselves and their families. Recovery Parkwill provide them the opportunity for a meaningful job, to earn a decent wage, own their own business and restore personal dignity, Wozniak said.

Under the $15 million project, which is expected to take five years to bring to fruition, RecoveryPark will replace blighted, vacant lots with dozens of massive greenhouses and hoop houses to grow produce. The fruits and vegetables grown in these facilities will be sold to local restaurants, retailers and wholesalers. Among the local businesses that already purchase produce from RecoveryPark Farms, includes the restaurants Cuisine and Wright & Co. (Detroit), Bacco Ristorante (Southfield) and Streetside Seafood and The Stand (Birmingham).

The City will lease the land to RecoveryPark for $105 per acre per year. In exchange, RecoveryPark must secure or demolish all vacant, blighted structures within its boundaries within the first year. Here are the terms of the deal:

- Within 120 days of possession, RecoveryPark is required to maintain the entirety of the leased footprint, mowing at least once every three weeks, and trimming trees. This remains continues for the entirety of the lease.

- Within 12 months of a signed term sheet, RecoveryPark will re-locate its Waterford, Michigan operations, to the City of Detroit’s negotiated footprint.

- Within 12 months of a signed term sheet 51% of employees will be Detroit based for the first 36 months. After 36 months, Detroit employment must increase to 60%.

- Within the first 12 months of a signed term sheet, RecoveryPark must secure or demolish any blighted / vacant structure within the boundaries. All demolitions will be in accordance with the City of Detroit’s demolition policy. Recovery Park must also present a plan to the City of Detroit for future use of all structures.

- Within 24 months of possession, RecoveryPark will operate at least 3 acres of greenhouses or hoop houses.

- Within 36 months of possession, RecoveryPark will operate at least 6 acres of greenhouses or hoop houses.

- Within 48 months of possession, RecoveryPark will operate at least 9 acres of greenhouses or hoop houses.

- Right of Reverter – The City of Detroit has the right to take back purchased land without greenhouses or hoop-houses if RecoveryPark defaults or does not meet terms.

“Commercial agriculture in Detroit is an important addition to Detroit’s expanding business portfolio,” sad Gary Wozniak, RecoveryPark CEO. “Mayor Duggan’s economic development team has move boldly and swiftly to align city resources with our company’s expansion needs.”

Indicators For Urban Agriculture In Toronto – A Scoping Analysis

Indicators For Urban Agriculture In Toronto – A Scoping Analysis

Strong leadership and support will aid the growth of urban agriculture across Toronto.

Authors: Rhonda Teitel-Payne, James Kuhns and Joe Nasr

Toronto Urban Growers

Dec 2016

Executive Summary

When Toronto Public Health (TPH) identified a considerable gap in Toronto- specific data on the impact of urban agriculture (UA), Toronto Urban Growers (TUG) was commissioned to engage Toronto-based practitioners and key informants on identifying the most relevant and measurable indicators of the health, social, economic, and ecological benefits of urban agriculture. The overall objective of the work was to develop indicators that a wide range of stakeholders could use to make the case for making land, resources and enabling policies available for urban agriculture.

The process started with a desk study of recent attempts to create indicators to measure urban agriculture in other jurisdictions. Indicator experts were interviewed to identify effective strategies and common pitfalls for developing indicators. The preliminary research informed the development of a set of draft indicators and measures, which were reviewed by Toronto-based practitioners in one-on-one interviews and a focus group. This feedback was used to further refine the indicators and measures and to develop data collection tools for each measure. A subset of the practitioner group gave additional feedback on the feasibility of the data collection tools, leading to a list of 15 indicators and 30 measures recommended for use. The review also identified additional indicators for further development beyond the scope of the current project and a short list of indicators not recommended for use.

The diversity of urban agriculture was flagged as a complicating factor in developing widely applicable indicators, as UA initiatives vary according to type of organizational structure, focus of activities, size and capacity to collect data. Specific indicators such as improved mental health and social cohesion are difficult to assess, while even a seemingly straightforward statistic such as the amount of food grown is challenging to quantify and aggregate. This report also identifies key audiences for the indicators and how they might be used. For governmental audiences, rigorous data that emphasizes both the importance of UA to constituents and the capacity of UA to help achieve the goals and objectives

of specific government initiatives is crucial. Valid indicator data is equally valuable to engage private and institutional landholders and to increase public support among residents and consumers.

The report concludes by remarking on the need for partnerships between the City of Toronto and urban agriculture practitioners to start using the recommended indicators to collect data for the 2017 season and to simultaneously continue working on the more complex indicators to create a complete suite of tools. While individual organizations and businesses can collect data for their own funding and land use proposals, support for broader-impact strategies and enabling policies will only be possible if a city-wide picture of the critical role of urban agriculture is clearly established.

Garden Spaces Join The Sharing Economy

Alfrea, a company based in Linwood, New Jersey, is trying to extend the sharing economy to garden spaces.

Garden Spaces Join The Sharing Economy

Alfrea, a company based in Linwood, New Jersey, is trying to extend the sharing economy to garden spaces. The company was founded in 2016 as an online marketplace for renting land and finding farm hands for hire. Alfrea has since expanded to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Frederick, Maryland. The company has plans to expand nationwide. The website also has as a farmers’ market platform which allows farmers to sell produce at any time.

For those who live in cities and want to grow food, but lack land, Alfrea facilitates relationships with people who have available plots of land and those who have surplus crops can also sell them on the website. There are three types of Alfrea memberships to use these services, ranging from free to US$15 per month. Visitors to the site can also learn how to grow food in environmentally sustainable ways.

Food Tank had the opportunity to ask David Wagstaff, the company’s founder, about Alfrea’s past, present, and future in the sustainable food movement. This startup wants to give all people access to local, sustainably grown food.

Food Tank (FT): What motivated you to start Alfrea and advocate for locally grown, sustainable food?

David Wagstaff (DW): My parents own a 30-acre farm, but at 92 and 86 years old, it is hard for them to manage. As they have aged, I have taken a more active role in managing the farm, as well as their financial affairs and health decisions. I began to ponder my parents’ health, and in turn, my own. In early 2015, I immersed myself in research on how to have high-quality senior years. I read multiple books, watched several movies, met with various health experts, and even hired a fitness coach. All the research pointed to the importance of eating fruits and vegetables and reducing processed foods. The standard American diet has been tied to common health problems such as heart disease, dementia, Type-2 Diabetes, and some forms of cancer. Further, food purchased at grocery stores is often processed with high sugar, fat, and severely lacking vital phytonutrients.

Surprisingly, as I conducted research, I found that agriculture is linked to environmental degradation and climate change. Food production produces 14 percent of the world’s greenhouse gasses. Methane, a byproduct of many agricultural processes, has a heat trapping index 23-times higher than carbon dioxide and food travels an average of over 1,500 miles from farm to table.

During this time, I was trying to find people that would be willing to grow food on my parents’ land or lease out a portion of it, but it was harder than I thought. When I attempted to grow food in my own yard, the same problems persisted. Even when I turned to farmer’s markets, they were usually only open one day a week during the growing season and not always at convenient times.

Through my experiences, I discovered the sustainable food movement has no central hub for people to participate. Overall, the idea for Alfrea arose from my desire to eat healthily, protect the environment, and unify others who think like me.

FT: Has connecting gardeners and eaters with land, help, and food producers been easier or harder than anticipated?

DW: That’s an easy question—definitely more challenging. It takes a lot of effort to get the word out. With that said, part of the reason why Alfrea exists is that people express much excitement about this concept. Even before launching the actual website, I was in a grocery store, and one of the clerks overheard me discussing Alfrea. After that, the clerk came up to me and said he wanted to hug me in the middle of the grocery store because he was thrilled about Alfrea’s vision. That same week, a well-known environmentalist in California who rarely gets excited about many businesses was ecstatic about Alfrea. He has held positions as a board member of organizations such as Oceana, Marine Sanctuaries, and Green Peace. Both of these interactions gave me the courage to pursue the idea further.

FT: How does Alfrea plan to motivate more Americans to utilize its website’s garden share, farmers’ market, and other online community resources?

DW: In every way, we know how. Public relations, social media, content writers, community events, and attending farm conferences will all further our cause. We intend to mainly have a business-to-business approach, offering Alfrea as an amenity to apartment communities and as a corporate employee benefit.

All of us here are excited because Alfrea breaks into a substantial market. Right now, 56 million Americans live in apartment communities and currently don’t have immediate access to grow their own food. All of those people can use Alfrea to find land to grow food or find others in their community to grow food for them.

FT: What are some of the shared benefits for farmers and customers renting land, getting hired for service, or buying produce through Alfrea?

DW: The upside of utilizing Alfrea is massive. For consumers, Alfrea makes it easy to grow and eat local, sustainable food. Studies show that when people grow their own food, they tend to eat more fruits and vegetables, which is beneficial for their overall wellbeing.

Landowners also profit in a big way. As Airbnb, Inc. did for bedrooms, Alfrea intends to do for property, farmland, and even backyards. Our vision is simple; people can earn extra income by offering land to consumers. With traditional methods, the average annual rental rate for farmland is about US$150 a year per acre. Leveraging Alfrea, landowners can subdivide the land to share with multiple growers and potentially earn more than US$3,000 a year per acre! Plus, in some areas, people gain additional tax reductions for using their property for agricultural purposes.

For farm hands and skilled gardeners, Alfrea generates more opportunities for them to earn extra income. Alfrea intends to pay these laborers with an Uber-like program. While over one million people work on farms today, it is virtually impossible to find someone to help you grow crops in your backyard. Alfrea connects this fragmented market by connecting income-seeking gardeners with those who want fresh food grown on their property.

According to the National Farm Workers Ministry, the average income for crop workers ranges from US$10,000 to US$12,499. With Alfrea, these laborers can set their own rate and are asking anywhere between US$15 and US$20 an hour. In other words, people working independently through Alfrea can make more than double the national average for farm workers.

Lastly, farmers looking to sell food benefit financially and from a convenience standpoint. Farmers usually sell to wholesalers who earn 40 to 50 percent of the produce’s market price. However, Alfrea charges farmers only 12 percent. This reduction means farmers will see an income increase and reduced time spent contacting wholesalers. Plus, Alfrea’s website gives farmers the option to opt out of sitting at farmer’s markets for hours at a time.

FT: Does Alfrea plan to leverage Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), a popular way for consumers to buy local, seasonal food directly from a farmer, as the company expands across the country?

DW: Yes, we believe Alfrea can be a central hub to unite the fragmented CSA marketplace. In our experience, it is not easy to find extensive lists of local CSAs. Alfrea’s website makes geographic searching easy.

FT: What are some of Alfrea’s goals for the future, besides expanding to more cities?

DW: We would like to create a mobile app. Today, we are mobile-friendly but do not have an Android or Apple app for members to use.

We look forward to having more customers on the website. Analytics will help us learn how to serve their needs best. We have conducted some customer surveys and interviews, but as we grow, we want to make sure we are meeting the needs of farmers and consumers.

Another key strategy for us will be expanding access. We want to reach affluent consumers as well as consumers that may not be able to afford fresh foods and reach people who live in food deserts. Our team is still working out the details how to achieve this goal well, but all of us at Alfrea are optimistic about the future.

Meet Alfrea, The Social Enterprise That’s Like Airbnb For Community Gardening

Mar. 22, 2017 4:49 pm

Meet Alfrea, The Social Enterprise That’s Like Airbnb For Community Gardening

The online platform connects aspiring gardeners to open garden space as well as locally grown food in their communities.

By Julie Zeglen / STAFF

If you belong to one of the 40+ million households in the United States that gardens for food, you should probably know about Alfrea.

The year-old social enterprise based out of New Jersey connects aspiring gardeners to open garden space as well as locally grown food in their communities.

The online platform also connects people with excess resources to those seeking resources. Have a big ol’ backyard that would be perfect for someone else’s herb garden? Looking to sell that surplus of tomatoes your crop yielded last season? Alfrea can help you out.

“What Airbnb did for the bedroom, we’re trying to do for land,” Lindsey Ricker, Alfrea’s customer engagement manager, told us during her “Around the Corner” interview. Learn more below.

How Millennials Will Forever Change America’s Farmlands

How Millennials Will Forever Change America’s Farmlands

March 21, 2017 | 3:21 PM ET

As Americans increasingly reject cheap, processed food and embrace high-quality, responsibly-sourced nutrition, hyper-local farming is having a moment.

Tiny plots on rooftops and small backyards are popping up all across America, particularly in urban areas that have never been associated with food production. These micro-farms aren’t meant to earn a profit or feed vast numbers of people, but they reflect the Millennial generation’s desire to forge a direct connection with the food they consume.

These efforts are an admirable manifestation of the mantra to think globally and act locally, but they miss the opportunity that is going on right now: the economics of branded local farms have changed, and technology in agriculture has led to a renaissance of independent American farming. Whether this means farming the traditional acreage of the Heartland or adapting to cutting-edge indoor farming methods, the result is the same: demand for real food is far outstripping supply. Highly-educated, entrepreneurial, and socially conscious young people have a great opportunity to think seriously about agriculture as a career.

On the surface, this advice sounds dubious, given the well-documented, decades-long decline of independent farming in America. Between 2007 and 2012, the number of active farmers in America dropped by 100,000 and the number of new farmers fell by more than 20%. Ironically, however, the titanic, faceless factory farms are barely eking out a profit. That often means that an independent 100-acre farm growing high-demand crops can be far more profitable than a 10,000-acre commodity farm growing corn that may end up getting wasted as ethanol.

The key to reviving America’s agricultural economy is casting aside the sentimental images we associate with farming – starting with what a farmer looks like. In recent years, many of the same technologies that have revolutionized the consumer world have fundamentally altered and improved the way we farm. Drones, satellites, autonomous tractors and robotics are now all at home on farms. As a result, tomorrow’s farms won’t just be part of the agricultural sector, they’ll also be part of the tech sector – and tomorrow’s farmers will look a whole lot like the coders who populate Silicon Valley…except with better tans.

The next assumption about farming we need to cast aside is what a farm looks like and where it will be found. The vast planting fields of America’s heartland are going to change by adjusting to grow real food with 21st century technology, but tomorrow’s farms will also be vertical and in or near our urban centers. By 2050, 70% of the global population will live in cities. As both a social imperative and a practical matter, it makes sense to grow food near these cities, rather than to waste time and resources delivering products from hundreds or even thousands of miles away.

This will require innovative new technology that will create even more flexibility in the way we farm. With this in mind, I recently co-founded Square roots, a social enterprise that aims to accelerate urban farming by empowering thousands of young Americans to become real food entrepreneurs. We create campuses of climate-controlled, indoor hydroponic farms in the heart of our biggest cities and train entrepreneurs how to grow and sell their food year-round. After their training, these young entrepreneurial farmers, in partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, can qualify for larger loan programs as a next step to owning their own farm -- either soil-based or indoor. Whether they move on to their own farm or another business, they are prepared to build forward-thinking companies that will become profitable and create good jobs.

We are investing in this initiative not only because it’s the right thing to do, but also because we are confident that agriculture is poised for explosive growth, and that technology and the power of locally branded farms will be the keystone to success. Just ask self-described “AgTech nerds” like Sarah Mock, who is a leader in the growing movement of Millennial entrepreneurs who see an opportunity in farming to achieve the double bottom line – value and values – that is key to solving our planet’s toughest challenges.

Private enterprise will lead this revolution, but the federal government must help fuel its growth. The 2018 farm bill is a critical opportunity. This massive legislation, renegotiated by Congress every five years, establishes the blueprint and funding priorities across America’s agricultural sector. Last year, Democratic U.S. Senator Debbie Stabenow of Michigan introduced forward-looking legislation called the Urban Agriculture Act that would offer protections and loan options that are currently available only to traditional rural farmers. Ideas like these are essential.

A future in which our food is safer, healthier and environmentally sustainable can exist alongside one in which our agricultural economy grows and creates good jobs for millions of American workers. The technologies and business practices of modern farming is spreading rapidly. The opportunity for a young farmer has never been better – and it’s a future we can all get behind.

Kimbal Musk is co-founder of the Kitchen Community, a nonprofit that brings outdoor vegetable gardens to schoolyards and community spaces. He sits on the boards of Tesla, SpaceX and Chipotle Mexican Grill.

Hydroponics Firm Launches Urban ‘Farm-In-A-Box’

Tuesday 21st March 2017, 16:38 London

Hydroponics Firm Launches Urban ‘Farm-In-A-Box’

Company aims to reduce food miles and boost nutritional value with hydroponic farming equipment for grocery stores, restaurants, and schools

Urban farming company groLOCAL is launching equipment to enable businesses to cut food miles and grow their own fresh produce on site.

The groTAINER shipping container - which the company describes as a fully-configured "farm-in-a-box” - allows grocery retailers, restaurants and schools among other businesses to grow produce such as herbs, spices and micro-greens on their own premises.

This ensures that produce maintains its nutritional value, according to the company, which highlights the fact that a tender soft tissue plant loses 80 per cent of its essential oils and half of its vitamin and mineral content within the first day after picking.

“It’s possible for businesses to grow highly nutritious produce at just a fraction of the cost of buying from suppliers,” the firm added in a press release.

David Charitos, managing partner of groLOCAL, said: “Standing out from the crowd in the food market can be a challenge. But having the ability to grow your own spice, greens, and herbs can mean you have something different to offer customers and really gives you the flexibility to try different flavours, knowing that all the ingredients are fresh.

“Having the option to grow some of the produce used means cutting down on expenses in the long run too."

The team behind groLOCAL are experts in hydroponic farming – the process of growing plants without soil, using nutrient solutions instead. This farming method makes it possible for businesses to grow plants anywhere, including urban environments.

The farm containers come with a fully-fitted production unit, including preparation and packing areas, meaning businesses do not need to find further space in their existing premises to accommodate hydroponic farming.

groLOCAL offers businesses the choice of either purchasing a groTAINER outright or leasing the equipment.

Urban Farmers Grow Veggies In Freight Containers

Urban Farmers Grow Veggies In Freight Containers

Kara Carlson, The Arizona Republic

9:10 a.m. ET March 21, 2017

(Photo: Kara Carlson/Arizona Republic)

PHOENIX -- The future of urban agriculture might require farmers to think inside the box.

Farmers here are growing vegetables here in converted freight shipping containers equipped with the latest hydroponics and automated systems equipment. They are provided by a Boston-based firm, Freight Farm.

“The farm of the future,” said Mark Norton of Phoenix, whose Picked Fresh Farms grows kale and lettuce in one of the containers.

Freight Farms started in 2010 with the goal of bringing viable, space-efficient farming techniques to all climates and skill levels year-round. It recently expanded to Arizona.

The cars are not cheap. Each container -- the kind commonly seen on trains, trucks or ships -- costs $85,000, not including shipping. Freight Farms calculates annual profit for each container to be an average of $39,000 annually.

Caroline Katsiroubas, marketing director for Freight Farms, said urban areas are the most popular destinations for its equipment and expansion has been nationwide.

Norton of Picked Fresh Farms isn’t what most people would picture as a farmer. The closest anyone has come to farming in his family was his grandfather, who farmed as a child, but that didn’t deter Norton.

“If I can get a better environment, better food, help people with their food, and still help people with their health, that’s where it all fits,” Norton said. “It aligns with my core values.”

He recently had one of his first successful harvests of lettuce, but he’s already looking to the future, with a 10-year goal to expand to 10 containers.

Mark Norton of Picked Fresh Farms closes the container where he grows kale and lettuce.

(Photo: Kara Carlson, Arizona Republic)

“I was just going to do it as like a hobby, but these things, there’s a need and nobody's really filling it,” Norton said.

Norton is one of only two freight farmers in Arizona, but the thought of competition doesn’t bother him.

“I think there’s enough space to have a bunch of these,” he said.

Heather Szymura, who co-owns Twisted Infusions Farms with her husband Brian, agreed. The Glendale, Ariz., company was the first in the Grand Canyon State to freight farm, and Szymura said she wants to see more of the farms come to Arizona because there is no way her company alone can feed everybody.

She has been urban farming for 12 years, with gardens and walls of plants in both her front and back yards. The latest edition, the 7½-ton container is nestled on the side of her house.

In a year, the 320-square-foot container can produce the equivalent of a three-acre farm. It also saves water, using five to 10 gallons of water a day, 95% less than traditional farms, Freight Farms said. The water is delivered in a nutrient-rich system based on hydroponics, a method to grow plants without soil.

Growing the leafy greens inside seem unnatural, but the farmers maintain not only is the process natural, it’s optimal.

Norton prides himself in using no GMOs, no pesticides and no herbicides. The environment is controlled, so there’s no reason for it. The container can put out 50 to 100 pounds of lettuce a week.

The farm uses strips of red and blue lights, the spectrums used in photosynthesis, to make it as efficient as possible. Machines automatically dose the plants with water and nutrients. All notifications lead back to an app on phones, which allows farmers to track everything from seeding to harvesting. On average the process takes about seven weeks and, depending on the environment, this can actually be almost twice as fast as a traditional farm, Freight Farms said.

This optimization allows for a greater variety than a grocery store might offer. Katsiroubas of Freight Farms said it allows farmers to focus on the characteristics they want because of the efficiency.

This is an aspect of farming the Szymuras enjoy, and it’s allowed them to be more experimental and try different plants and techniques.

Kale growing inside a temperature-, water- and light-controlled freight car makes the plant sweeter, and softer, Norton said. He said it’s also healthier because it’s traveling less distance and keeping produce local.

The ability to support local is part of what appealed to the Szymuras. They get as much of their farming products and water supplies as possible from local suppliers.

The produce is all sold locally, and the container allows them to easily educate people on urban farming and the seed to harvest process.

Szymura especially enjoys the ability to watch the process from start to finish. Seeding starts in trays kept at optimal light and temperature and then moves to the towers, which contain rows and surround more LED lights.

It’s something her clients like seeing as well. Many of Twisted Infusion’s customers are chefs and caters who come in to see what will be harvested next and appreciate being able to even pick the produce themselves. The caters can have their produce from farm to table in the same day.

The system, and the ability to switch crops easily, also allows chefs to put in specific orders and know it will be ready when they need it.

Norton is focused more on restaurants and individuals through members of Community Supported Agriculture, a subscription-like system that lets customers buy shares of local food. Norton expects most of Picked Fresh Farms' business to come from this, but he also has started to reach out to restaurants with samples of his product.

U of T Scarborough Explores How Urban Agriculture Intersects With Social Justice

U of T Scarborough Explores How Urban Agriculture Intersects With Social Justice

March 21, 2017 | By Don Campbell

A summit hosted at U of T Scarborough this month looked at urban agriculture and the role of community gardens in Toronto

As Toronto continues to grow, urban agriculture may play a more significant role for people seeking alternative sources of nutritious and affordable food, U of T researcher Colleen Hammelman says.

Hammelman has examined urban agriculture in such cities as Medellín, Colombia, and Washington, D.C. She explored the role of urban agriculture in the GTA and social justice at a one-day conference organized at U of T Scarborough this month.

“Urban agriculture brings a lot of value to a city, especially in terms of sustainability, but a key element is how social justice also fits into the conversation,” says Hammelman.

While urban agriculture is widely practiced in many respects, it’s also misunderstood, particularly the important role it plays in migrant communities both culturally and nutritionally, notes Hammelman, who is a post-doc researcher at U of T Scarborough's Culinaria Research Centre.

From her experience, urban agriculture not only supplements food budgets by giving access to fresh food many can’t afford, but it also provides “spaces of community resilience” where residents can come together for a common purpose.

“Community gardens also provide important avenues of support for new Canadians,” she adds.

The conference featured a variety of speakers including Kristin Reynolds, author of Beyond the Kale, and Toronto Councillor Mary Fragedakis, along with members of various community organizations like Black Creek Community Farm, Toronto Urban Growers and AccessPoint Alliance. Undergraduate and graduate geography students also had a chance to meet with participants to talk about how social justice fits into the conversation around the urban agriculture movement.

There are about 200 spaces ranging in size that are designated for community gardens across Toronto where people can grow food.