Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

5 Ways Urban Farming Benefits Utah's Cities And Residents

5 Ways Urban Farming Benefits Utah's Cities And Residents

Utah League of Cities and Towns

Published: March 3, 2017 11:40 a.m.

This story is sponsored by Utah League of Cities and Towns. Click to learn more about Utah League of Cities and Towns.

Urban farming may sound like your hipster cousin's latest hobby, but, in fact, it is transforming the way Utahns grow and buy their food. Over the past several years, the benefit of locally grown food is becoming more apparent.

According to a study by Envision Utah, only 2 percent of fruits and 3 percent of vegetables in Utah are produced locally, and these percentages could decline significantly as Utah's population and land development increases. This has led to a huge demand for urban farming solutions that support both growers and consumers in the community.

Whether you're a long-time "locavore" or a newcomer to the world of urban farming, there are plenty of reasons to jump on this produce wagon and get involved in your local urban farming programs.

1. Support the local economy

Perhaps the most obvious benefit of buying and eating local is the economic value. Spending money at your farmer's market or through membership in a Community Supported Agriculture organization puts those funds back into your community. A study by the research firm Civic Economics found that 48 percent of money spent at a local independent business is directly or indirectly recirculated into that community — compared with less than 14 percent of purchases at chain stores.

By supporting your local producers, you help protect their livelihoods and improve the health of the local economy. Good for you, good for business, good for the community.

2. Access fresher, healthier food

But urban farming isn't just about business and economics. There are wonderful health and quality benefits for the consumer, too. For instance, food often travels hundreds or even thousands of miles from the source to your plate. In order to transport produce over such great distances, much of it is harvested before it is ripened and is highly processed with preservatives. This leads to less nutritious and less tasty food by the time it reaches your table.

In contrast, local produce is often picked that day and avoids some of the harsher processing and handling methods that detract from the taste and quality of the food. Plus, you have the added benefit of buying directly from the grower, so you can ask them questions about how they grew and handled the produce before it reached you.

Programs like the Salt Lake County Urban Farming program were created in part to facilitate these benefits and interactions. Program Manager Supreet Gill explains, "Increasing the local food supply is one of the biggest things that’s needed, so we connect farmers with available land," which in turn connects the local community with fresher, healthier food options while supporting local family farms.

3. Improve the environment

Locally sourced food also has environmental benefits. One of the most obvious and oft-acclaimed advantages is transportation. Because local food is produced right in the area, it doesn't have to travel as far to get to the consumer as traditional, mass-produced food. With fewer miles to travel, locally grown food tends to create a smaller carbon footprint.

But that's not the only environmental effect. Supporting the growth and development of local farms has numerous benefits to the local ecosystem. Urban farming and gardening adds much-needed support to local bird and insect populations, particularly bees, which have been declining in numbers over the past decade. As people cultivate rich and diverse gardens, bees will have greater sources for pollination, which benefits the bees and the growers. Not a bad deal for the Beehive state.

4. Bring communities together

One of the most rewarding benefits of urban farming is the community impact. Through programs like Salt Lake County's Parks to Produce and Commercial Farming initiatives, people living in cities and towns across the state have the opportunity to connect more closely with their food, their land and their neighbors. From participating in a CSA, cultivating a plot in a community garden, or buying food at the local farmer's market, urban farming provides multiple ways for people to interact with fresh local food and each other.

5. Empower individuals and families

When communities prioritize local food production, they empower individuals and families to increase self-reliance and sustainability. Gill explains that one of the main obstacles in her county is the lack of available, farmable land. The demand for local food is high, yet local farmers often don't have the land resources to produce enough food to meet that demand. Fortunately, a lack of available farmland is not the case in many Utah communities. And as the community works together to provide those land resources to farmers, and other public spaces for community gardens, people will have greater opportunities to provide for themselves and their families, and make food choices that will benefit their lives and the community.

Urban farming has grown in popularity over the years and with so many benefits, it's no wonder why. If you're interested in getting involved in urban farming but aren't sure where to start, Gill recommends purchasing a share in your local CSA, shopping at your farmer's market, or, if you live in the Salt Lake valley, participating in one of the four county community gardens.

Read more from the Utah League of Cities and Towns on DeseretNews.com or visit their website at ulct.org.

This Mumbai Ecopreneur Has Been Turning City Dwellers Into Urban Farmers for Over Half a Decade

This Mumbai Ecopreneur Has Been Turning City Dwellers Into Urban Farmers for Over Half a Decade

During a college project, Priyanka Amar Shah combined her love for nature with business skills to start iKheti, an enteprise that facilitates urban farming

by Sohini Dey

Priyanka Amar Shah attributes her love for greenery to her “nature loving family.” The Mumbai resident grew up in a suburban home whose balconies were always adorned with plants. It was also her affinity for nature that made her notice how barren the other balconies of her neighbourhood seemed in comparison.

Around 2011, Priyanka and her brother began growing herbs at home, plucking chillies and lemons for family dinners. During this time, she was pursuing and MBA from Welingkar Institute of Management Development & Research where she got an opportunity to present a business idea. Determined to use the opportunity fruitfully, she combined her love for nature with business skills to conceptualise iKheti, an urban farming enterprise.

Today, iKheti has become a full-fledged eco-friendly enterprise that facilitates farming among city dwellers with workshops, consultancy and gardening resources.

iKheti aims to create a sustainable environment

For this young ecopreneur, concern for environment goes hand-in-hand with a healthy food movement. Unlike other gardening ventures, iKheti emphasizes on growing edible vegetables, fruits and herbs. “Mumbai is great for growing edible plants. We have great sunshine and the weather is not as extreme as other cities,” Priyanka says.

Priyanka’s vision for iKheti’s vision is, “To create a platform for both, individuals & communities to grow healthy consumable crops within their premises & promote sustainable urban farming.”

Today, a number of organisations work in the same area and the number of people invested in urban farming is on the rise. Yet in 2011, when Priyanka got started, it was still unexplored territory and people had to be educated on the benefits and methods of farming in small spaces.

“We started with workshops,” says Priyanka on her early days with iKheti. “But we soon realised that holding workshops was not enough.” People needed to carry their learning back from home and apply it, and Priyanka took a more holistic approach to overcome the obstacle. From seeds and organic manure to consulting and maintenance, iKheti expanded their scope. “It was an unorganised sector and professional help was lacking,” she says. “Our main focus was to become a one-stop shop.”

Supported by a network of volunteers and trained malis, iKheti hopes to introduce everyone to the joy of organic farming.

Promoting organic farming among urban dwellers

Priyanka insists on taking the no-chemical approach to farming, in tandem with her emphasis on healthy eating. From offering seeds and DIY kits on sale to offering consulting services on composting and kitchen gardening, she wants to train people in the art of growing their own food.

For time-strapped clients, iKheti offers an on-call mali (gardener) service. Finding this taskforce was one of her biggest challenges, Priyanka admits, as they were unfamiliar with the extra maintenance and organic methods. “Over time, they have become very caring. I foster animals, and sometimes when I am not around the nursery, they do it for me.”

“Our malis are specially trained to look after edible plants, and they are the backbone of this business,” she adds.

For beginners, Priyanka recommends growing herbs, which are easier and faster to grow. Herbs like curry leaves, ajwain, tulsi and pudina are very popular. “These might sound common, but 90 percent people who come to us don’t grow any of those plants,” she says. Herbs like celery, basil and oregano are also popular and Priyanka recommends growing these before one moves on to vegetable farming.

iKheti’s success has prompted Priyanka to take up new challenges: community farming, vertical gardening & hydroponics.

iKheti’s diverse undertakings, from innovative planters to grand vertical gardens

Having reached out to over 4,000 people via personal services and workshops, Priyanka is now emphasizing on encouraging bigger groups. iKheti’s experience with a few corporate and religious institutions has also shown that farming is best effectively practised on rooftops or bigger spaces. She also works with schools, encouraging children to eat healthy and understand the value of food.

Another area in which iKheti is beginning to work is with farmers around Mumbai, teaching them the values of organic farming. Admittedly, it is not easy—farmers worry about diminishing produce and Priyanka thinks it is a valid concern driven by the market and low awareness. “Many farmers don’t know that organic produce fetches higher prices,” she says.

The iKheti team not only educates farmers, but also teaches them the value of land as legacy. After all, a fertile land is a boon for the next generation.

Keeping space considerations in mind, iKheti is also venturing into vegetable growing in vertical spaces and taking tiny steps towards hydroponic systems. Their ultimate endeavour is to combine the two in an effort to offer greater convenience for urban farmers.

Priyanka aims to acquaint people from all works of life to the importance of a green environment. Not just farming, even smaller plants can make a difference. At the iKheti nursery, plants are reared to contribute to their surroundings, from purifying the air to attracting butterflies and insects. “We want to create a sustainable environment,” she says, encapsulating her ecopreneurial vision.

Check out the iKheti’s products and services online or get in touch with Priyanka here.

Can Urban Farming Combat Food Waste? Chatting With The Founders of Alma Backyard Farms

Can Urban Farming Combat Food Waste? Chatting With The Founders of Alma Backyard Farms

Raised garden beds at Alma Backyard Farms. (Rebecca Yee)

By Noelle CarterContact Reporter

On Monday, volunteers and farm members will be collecting unharvested colorful leaves of Lacinato kale, Redbor kale, Bright Lights Swiss chard and purple cabbage at the Alma Backyard Farms at a local church and school location in Compton. The “gleaning party” is just part of the preparation for the first Los Angeles Feeding the 5000 event later in the week on May 4, culminating in a free feast made entirely from fresh produce and meant to highlight the global issue of food waste.

Alma Backyard Farms was started in 2013 by Richard D. Garcia and Erika L. Cuellar as a small, urban farm project. Inspired by the ideas and desires shared by juvenile offenders and prisoners, Garcia and Cuellar founded the farm as a means for these folks to transform their lives through farming. Through nature, members learn how to nurture, provide and give back to their communities — all while becoming self-sufficient. Recently I spoke with Cuellar and Garcia by phone as they tended their Compton garden location.

Where do you find the land to farm? Do you really farm in backyards?

Erika Cuellar: We started in backyards, but we’ve grown. We have a partnership with a transitional home in South L.A., and that particular home houses predominantly “lifers” — men who have served life sentences. We’ve basically transformed the outside of this home that houses 16 guys into an urban farm with a garden, chickens and about 20 fruit trees. It’s really about taking underutilized land and making it productive. We don’t farm acres of land; everything is urban, and they are small farms.

Our newest place, which is where we’re going to glean from for the Feeding the 5000 event, is in partnership with a school and church. They had a piece of land that was not utilized, and we transformed the space to grow food for people who are hungry.

What exactly is “gleaning”?

It’s harvesting. It’s collecting unharvested produce from the field.

Our focus is on reconnecting people through their food and to each other. Waste stems from a lack of connectedness.

— Richard D. Garcia, executive director and co-founder, Alma Backyard Farms

Can you talk a little about food waste from the farm standpoint? When it comes to waste, we’re not just talking about the food itself, but everything that went into it — the water, energy, effort and land.

Richard Garcia: My answer would have to be partly philosophical. The way we grow food is based on relationships. You understand the relationship between not just the plant and the soil — but the relationship between the plant and its caretaker. We approach farming by way of understanding interdependence, how we all have to contribute to one another’s well-being. From that perspective, wastefulness is a result of disconnect. It’s unfortunate — waste happens because we’ve somehow given ourselves permission to be disconnected from each other. We don’t have a relationship, or even knowledge, of the soil, or even the effort it takes for someone to pick the fruit you see at the grocery store. We’re more interested in the product itself than the whole of the experience.

What surprises your members most about the farming experience?

Garcia: I think because we work primarily with people who have been incarcerated, we’re hoping to restore a sense of agency. For someone who’s been locked up for a long time, there’s a sense of powerlessness because you hold no keys. From a lengthy experience like that to a setting such as an urban farm, suddenly you’re the caretaker. You have custody of plant life, and that’s a shifting of the paradigm. And, in a sense, nothing goes to waste. When folks are able to give back to the communities that they’ve taken from, they’re contributing.

I think when we instill a sense of resourcefulness, you don’t want to be wasteful, even with your time. The thing about food waste is it’s only symptomatic of how wasteful we can be in the larger context. We want to drive home to our members that they are of value and have purpose. I know that may not sound like it has to do with food, but it’s all related.

Your website mentions that you teach families and children how to grow and cook meals. How important is the relationship between growing and cooking?

Cuellar: It goes right to the issue of waste and wasting time. Knowing how to grow, where your food is grown and doing that together is so important. We see farming and growing food as a means to unify families. Being able to do that is key with the individuals we work with, and we encourage their parents and children, even grandparents when available, to join in.

With our own team and members, we break bread together every day we work together. Sharing a meal is one of the better things we do during the day. We emphasize meals that are healthier and introduce a more nutritional aspect.

You make sure none of the food goes to waste. What restaurants or organizations do you partner with?

Cuellar: With restaurants, we work primarily with chefs who are interested in carrying out seasonal menus. Restaurants are one facet, along with organizations such as L.A. Kitchen, that transform the food into hot meals for people who are hungry. At the transitional home, the food benefits the residents as well as the surrounding community. At our Compton site, it directly impacts the community here: the schoolchildren, parishioners and church community.

Garcia: We’re also developing more and more of our own compost, so nothing ever really goes to waste. As we grow, I’d love to see us take up more food waste from restaurants and convert it to compost.

You’re looking at the whole food chain, from planting the seeds to decomposition and turning that back into nutritional soil after it has lived its life.

From life to death and life again.

Chefs and scientists will discuss solutions for tackling the global problem of food waste at the Los Angeles Times Food Bowl, beginning May 1. For a full schedule of events, click here.

Hydroponic Farming Takes Root In CT

MAY 1, 2017 1 COMMENTS

Hydroponic Farming Takes Root In CT

PHOTO | STEVE JENSEN

Cheshire-based Maple Lane Farms II co-owners Allyn Brown (left) and Brant Smith inspect a foam float holding heads of hydroponically grown bibb lettuce nearly ready for market.

KAREN ALI

SPECIAL TO THE HARTFORD BUSINESS JOURNAL

Connecticut produces a mere 1 percent or so of the fruits and vegetables eaten by its residents.

That's a statistic state agricultural experts and producers want to change.

One way they are hoping to move the needle is through a type of controlled environment agriculture, called hydroponic farming, which is an eco-friendly way of growing produce in a soilless medium, with nutrients and water.

Hydroponic farming is gaining popularity in the state and nationwide, particularly in response to consumers' shift toward healthy eating and locally grown produce, rising food prices and extreme weather conditions making it harder for traditional farming.

Joe Geremia, known as the go-to guy for hydroponics in the state, said because Connecticut has a small amount of farmable acres, it makes sense to turn to hydroponic farming.

"It's nearly impossible [for Connecticut] to feed itself," said Geremia, who is a partner in Four Season Farm LLC, which will develop 10 acres of land in Suffield as a startup hydroponic farm. The farm, which the state has invested $3 million in, is expected to generate 40 jobs over the next two years and produce millions of pounds of tomatoes.

"It's a perfect thing for Connecticut. We can do more per acre, if we can do it indoors," said Geremia, who runs seven acres of greenhouses in Wallingford.

Geremia and others say more Connecticut farmers and greenhouse operators are adopting controlled environment agriculture.

"More people are embracing indoor technology in farming," Geremia said. "The trend is upward."

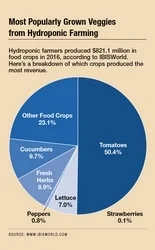

Hydroponic farming industry revenues, which reached $821.1 million nationwide in 2016, have grown at an annual rate of about 4.5 percent since 2011, according to research from IBISWorld.

PHOTO | STEVE JENSEN

Examples of the bibb lettuce produced by Maple Lane Farms. The lettuce is sold to grocery stores, including Stop & Shop, as well as wholesalers.

And of the 2,347 hydroponic farm businesses that existed in 2016, 3.8 percent operated in Connecticut, according to IBISWorld.

Four Season Farm LLC, which is expected to break ground this spring, plans to produce 5.75 million pounds of tomatoes the first year and 7.5 million pounds by the third year. The farm plans to add cucumbers, peppers and micro-greens.

In a February publication put out by the state Department of Agriculture, Commissioner Steven Reviczky said the Suffield project could lead the way to transforming Connecticut's greenhouse industry.

"Hydroponic and other types of indoor farming are becoming increasingly effective alternatives to traditional growing methods in many parts of the world," Reviczky said. "Connecticut has a well-established greenhouse industry that I believe could make the transition to growing food 12 months a year, and has the customer base to support it."

Win-win

Hydroponic farmer Allyn Brown, who has been producing lettuce on his Cheshire farm for three years, and on his Preston farm for six years, said there is a resurgence of indoor agriculture.

"It's a growing business in the northeast," Brown said. "We run 52 weeks a year. On an acre, you produce more indoors than out."

It's seen as a win-win for both consumer and farmer, farmers say.

Consumers — who are increasingly pushing for fresh vegetables and fruits year-round — gain by getting locally sourced fresh produce whenever they want it.

Hydroponic farmers winbecause instead of growing crops only four or five months of the year, they can be year-round producers, leading to new and more revenue opportunities.

"The reality is, if we are going to provide more local food when people want it, we have to figure out how to do it off-season," said Henry Talmage, executive director of the Connecticut Farm Bureau, and a vice chairman of the Governor's Council for Agricultural Development.

The Governor's Council, which was created in 2011, is looking to create a strategic plan for Connecticut agriculture, including looking at ways to increase by 5 percent the amount of consumer dollars spent on Connecticut-grown farm products over the next few years through 2020.

Talmage says while there are disadvantages to hydroponic farming, like high labor, energy and transportation costs, Connecticut does have several things going for it.

For one, Connecticut has a very robust greenhouse industry, which means that facilities already exist for hydroponic farming.

Connecticut is also in a "high-market corridor," between Boston and New York and near Philadelphia and Washington.

When dealing with perishable items, it's good to be closer to the markets you are supplying, Talmage said. "It's crazy when our food travels 1,500 miles to get to us. Connecticut is in a position to do this better than other New England states."

Brown, who owns Maple Lane Farms in Preston and Maple Lane Farms II in Cheshire, agreed that Connecticut is in a good geographic position for hydroponic farming.

His two farms produce 1.5 million heads of hydroponically grown bibb lettuce annually.

"It's got a great flavor," he said of the lettuce that is made without pesticides, is dirt free and stays fresh for a long period of time.

"Chefs really like to use the lettuce (which comes attached to the root ball) because it's so fresh and it is all usable," Brown said.

Maple Lane sells the product to grocery stores like Stop & Shop and LaBonne's as well as to wholesalers.

"They want it 12 months a year," Brown said, of the grocery stores.

The demand is a great thing for local farmers, and farmers hope the desire for local produce continues.

"You are supporting local agriculture as you purchase it," Brown said.

2018 Farm Bill Is Enormous Opportunity For Urban Agriculture

2018 Farm Bill Is Enormous Opportunity For Urban Agriculture

APRIL 19, 2017BRIAN FILIPOWICH 2

By Brian Filipowich, Director of Public Policy at The Aquaponics Association

About every five years the Federal Government passes a massive, far-reaching “Farm Bill” with the main aim of providing an adequate national supply of food and nutrition. The Bill affects all facets of the U.S. food system including nutrition assistance, crop subsidies, crop insurance, research, and conservation. The 2014 Farm Bill directed the spending of about $450 billion.

Unfortunately, in recent decades, the Farm Bill has become a boondoggle for “corporate mega-farms”; multi-billion dollar operations that control vast acreage. The Farm Bill has failed to provide commensurate assistance to urban farmers. In effect, our government is using our tax dollars to give an advantage to corporate mega-farms over our small urban farms. Sad.

For example, the Farm Bill is the main reason high-fructose corn syrup is so cheap and loaded into 70% of food in the grocery store. In his book, Food Fight: The Citizens Guide to the Next Food and Farm Bill, Daniel Imhoff writes: “Fresh fruits, vegetables and whole grains – the foods most recommended by the USDA dietary guidelines – are largely ignored by Farm Bill policies.”

The Farm Bill has provided us a large, reliable quantity of food, but a food system racked with economic consolidation, environmental damage, and poor health outcomes.

The Urban Agriculture community has a great opportunity to shape the 2018 Farm Bill for two big reasons: 1) we offer benefits that appeal to politicians across the political spectrum, and 2) the public is already with us on this issue, ahead of the politicians.

Urban Agriculture boasts the following benefits that politicians love to hear:

- Year-round controlled-environment jobs and local economic growth;

- More fresh food to improve our diets and lower healthcare costs;

- Less waste from food spoilage and food transport; and

- Better food security.

The American consumers’ spending habits show that they are ahead of the politicians on this issue: Consumer Reports found an average price premium of 47% on a sample of 100 USDA Organic products. If folks are willing to pay 47% more for organic, then they are also willing to call their representative’s office, attend a town hall meeting, and show up at the ballot box. The energy to make the change already exists, we just need to channel it.

We have already seen the first step to shifting the Farm Bill toward our direction: Senator Debbie Stabenow (D-MI), the top Democrat on the Agriculture Committee, recently introduced the Urban Agriculture Act of 2016. The goal for the Act is to be eventually included as its own Title of the 2018 Farm Bill.

Here are some provisions of the Act:

- expands USDA authority to support urban farm cooperatives;

- makes it easier for urban farms to apply for USDA farm programs;

- explores market opportunities and technologies for lowering energy and water use;

- expands USDA loan programs to cover urban farm activities;

- provides an affordable risk management tool for urban farms to protect against crop losses;

- creates a new urban agriculture office to provide technical assistance; and

- expands resources to research, test, and remediate contaminated urban soils.

In Washington, DC, change is sometimes painfully slow. Positive changes for Urban Agriculture are by no means a foregone conclusion, especially in our unpredictable political environment. Politicians need to see that this issue will move votes.

So let’s stress our message and get the word out now, the politicians are ready to listen. Urban Agriculture offers jobs; fresh food and better health; less waste; and better food security. The legislative soil is fertile my agricultural amigos, now it’s our job to plant the seeds of an urban-friendly Farm Bill!

One way to stay involved is to sign up for the Aquaponics Association’s 2018 Farm Bill Coalition. Or there are many other groups that will be getting involved, including a few listed below.

Here’s some related resources to learn more:

- National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition Farm Bill Primer

- Haas Institute: The U.S. Farm Bill; Corporate Power and Structural Racialization in the United States

- Food Tank, the Think Tank for Food

- Association for Vertical Farming

- Congressional Research Service 2014 Farm Bill: Summary and Side-by-Side

- Congressional Research Service The Role of Local Food System in U.S. Farm Policy

- The Atlantic: Overhauling the Farm Bill; the Real Beneficiaries of Subsidies

Brian Filipowich

Director of Public Policy

The Aquaponics Association

Related

Vertical Farms to Shape Future Agriculture Supply Chains

Vertical Farms to Shape Future Agriculture Supply Chains

- New Straits Times

- 3 May 2017

- The writer is founder and CEO of LBB International, the logistics consulting and research firm that specialises in agri-food supply chains, industrial logistics and third-party logistics. LBB provides logistics diagnostics, supply chain design and solutio

BY 2040 the world will have nine billion inhabitants, of which the majority of which will live in cities. With a growing population and high urbanisation figures many countries, including Malaysia, have become highly dependent on imports for basic agriculture commodities.

This has created very long agriculture supply chains, with the agriculture produce section in our supermarkets today featuring food from all over the world!

As agriculture produce is living matter, the moment it is harvested or slaughtered it becomes a highly sensitive product that requires a specific environment, handling and has limited shelflife.

Long agriculture supply chains, therefore, means higher risks of diseases, reduction of quality, higher wastage, and high logistics costs.

Food miles, the distance food needs to travel to the point of consumer purchase, have exploded over the past 25 years.

Research shows that systematic long food miles are not sustainable.

High dependence on imports comes with high risks for countries, as food prices become highly dependent on the availability of excess of agriculture produce by agriculture exporters.

Is there a way back to where we have shorter supply chains for our basic fresh produce?

To significantly increase local production of basic agriculture commodities in Malaysia, there are two solutions: agriculture food parks and integrating farming in urban environments.

Agriculture food parks produce agriculture products in bulk and are located in rural areas.

These parks are also involved in processing, ranging from washing, cutting, packing up to advanced food processing into ready meals and ultra-processed foods.

These agriculture food parks then transport these products by truck to retail outlets and restaurants.

However, as land becomes more scarce, the necessary land is often not available for this kind of bulk agriculture production. Therefore, the integration of farming in urban environments becomes a necessity in order to feed our growing population in combination with high urbanisation.

The Netherlands has more than 100 years of experience in indoor farming, and is today the example of producing agriculture products in situations where land is scarce or not suitable for farming due to climate conditions.

All over the world, countries are looking at initiatives in vertical farming.

Vertical farms are high-rise multi-functional buildings producing food in a vertical system. This can be integrated in an office building, flat, or condominium.

These buildings need to plan the necessary water, energy, and nutrient requirements needed to farm. Water can come from rainfall.

Energy can be supplied from solar energy and by making use of specialised light-emitting diode lights, where vegetables, herbs and soft fruits can be produced in climate chambers, through environmentally friendly closed systems.

These farms can be even be integrated with fish farming.

Nutrients can be gathered from used coffee grounds from coffee shops and waste from restaurants, supermarkets, and households.

Vertical farming reduces the agriculture supply chain distances dramatically, bringing down transportation costs.

However, this requires food production to be integrated in city planning.

City planners will need to force real estate developers to integrate farming in buildings.

Food sovereignty, safety, security and sustainability can thus be solved by the introduction of vertical farming.

Vertical farms dramatically reduce agriculture supply chains, cutting transportation costs and enhancing freshness.

This allows countries to restore the ecological balance in the urban jungle.

Opportunities For Growth Abound

Opportunities For Growth Abound

Rice University students learn science basics by contributing to a startup urban farm

Video produced by Brandon Martin/Rice University

HOUSTON – (May 2, 2017) – Freshmen in two Rice University classrooms teamed up this spring to make a joyful contribution to Recipe for Success' Hope Farms in Houston and learn basic scientific method along the way.

Learning literally from the ground up, the students developed their analysis of soil from fields at the urban farm, which was founded to bring nutrition to a food desert in the south part of the city.

At the start of the semester, lecturers Sandra Bishnoi and Michelle Gilbertson, both part of Rice's Wiess School of Natural Sciences, brought students to collect samples from the farm a few miles south of campus. Back then, the 7-acre site and former location of a Houston high school was still bare.

The students were pleased to return in April to see nearly an acre bursting with lettuce, tomatoes, carrots and other produce, some ready for harvest. The fruits -- and vegetables -- of their studies will help as the farm plows and plants new fields in the coming seasons.

"I'm a pre-med student and I came into this class expecting to do research, but not on this subject," Raymond Tjhia said while visiting the farm in April. "It's a really neat experience. At Rice, you can get your hands dirty and do something that helps the community while also gaining skills that will help you in any field."

"We really lucked out in finding a connection with Rice," said Hope Farms manager Amy Scott, who met Bishnoi and Gilbertson through Caroline Masiello, a Rice professor of Earth science and chemistry. "We discovered we had a lot of common purposes, that the professors were looking for opportunities for their students to have a real-life application of their skills and we were looking to learn a lot about our soil, since it is a wild card in a lot of ways."

Scott said the students' most surprising discovery revealed differences in soil acidity from field to field. "I wasn't that aware of how much the pHwas fluctuating in our fields," she said. "We ended up having a pretty broad range. That, I found out, could have been affected by our well water, which is much more acidic than we realized."

Acidity was only one aspect of the study. Gilbertson's chemistry class also analyzed the soil's salinity, conductivity, ion exchange and asphalt contamination, noting at a presentation for farm officials that material left over from razed structures had not hurt the soil. "But where the school building sat on the soil, we're finding low carbon mass," she said. "That's because nothing has grown on it and died and put carbon back into the soil."

Bishnoi's biology class tested for acidity and also designed experiments to study soil microbiology, phosphorus deficiency and water retention. "We have teams using an organism called Daphnia magna, a model of toxicity for effluents in water being drained off an area," she said. "Another team is looking at good and bad microbes in the soil to see how can we modify the microbiology to improve cultivation."

The students planted seeds in soil samples from the farm alongside seeds in potting soil. "They compared the yield from spinach and green beans, crops we knew would grow quickly," Bishnoi said. "We've gotten some nice leaf growth and germination." However, they discovered that soil from raised beds at the farm only allowed seeds to germinate and not grow into edibles.

"The clay is holding onto all of the minerals and not releasing them to the plant," she said. "The plant is having to work too hard, so there has to be some kind of soil amendment to allow better permeation."

While many laboratory courses begin with a prescribed set of experiments that lead to a foregone result, the Rice freshmen were given problems and told to design their own protocols.

"I really appreciate that you get to try to figure it out on your own," said Michelle Nguyen, the only student to take both classes. "It's been a lot of trial and error, and the method that you come up with initially doesn't necessarily work out. But it's a whole learning process."

Hope Farms' chief agricultural officer Justin Myers said the focus of its parent foundation, Recipe for Success, has been education, and it has worked extensively in Houston schools to teach children about nutrition. When the chance to establish an actual farm appeared, the organization wasted no time: It bought the former Carnegie Vanguard High School site and began preparing it for planting.

"It gave the neighbors comfort to know we were buying the land, not just leasing it until developers came in and started building," Myers said.

Hope Farms hosted its first farmers market on Earth Day, April 22. The first produce traveled mere yards from farm to farm stand, where people from the community lined up to get fresh vegetables.

Scott said she is already considering what tests she'd like Rice students to run in the future. "We appreciated their enthusiasm and dedication to finding out what's going on, coming up with really interesting experiments and making sure every step along the way that it was something that was going to benefit us," she said.

-30-

Visit the Hope Farms website at http://recipe4success.org/programs/hope-farms.html

This news release can be found online at http://news.rice.edu/2017/05/02/opportunities-for-growth-abound/

ollow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews

Related materials:

Wiess School of Natural Sciences: http://natsci.rice.edu

Recipe for Success: http://recipe4success.org/about-us/

Rice University student and teaching assistant Leila Wahab pulls a core sample from the ground at Hope Farms during a recent visit. Rice chemistry and biology students analyzed soil samples for the new farm on the site of a former public school on the south side of Houston. Standing from left: Jessy Feng, Shweta Sridah, Hania Nagy, Michelle Nguyen and Raymond Tjhia. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/files/2017/05/0508_HOPE-1-WEB-1qcpcg4.jpg

Core samples taken from Hope Farms by Rice University students revealed how well-suited the land is for cultivation. Freshmen in two classes participated in a semester-long project to analyze soil from various places around the 7-acre farm. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/files/2017/05/0508_HOPE-2-WEB-25hic22.jpg

http://news.rice.edu/files/2017/05/0508_HOPE-3-WEB-1zo6f9w.jpg

Crops grow in raised beds at Recipe for Success' Hope Farms in Houston in April. The farm's first harvest is helping to alleviate conditions in a food desert south of downtown. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

http://news.rice.edu/files/2017/05/0508_HOPE-4-WEB-29mhb1o.jpg

Rice University student Raymond Tjhia explains the science behind results from his team's analysis of soil conditions at Hope Farms. Listening are, from left, farm manager Amy Scott, chief agricultural officer Justin Myers and Rice lecturer Sandra Bishnoi. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

Rice University chemistry lecturer Michelle Gilbertson introduces students who presented the results of their semesterlong effort to analyze soil conditions for cultivation at Houston's Hope Farms. The nonprofit farm opened this year to provide a food desert in the south part of the city with fresh produce. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation’s top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,879 undergraduates and 2,861 graduate students, Rice’s undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for happiest students and for lots of race/class interaction by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger’s Personal Finance. To read “What they’re saying about Rice,” go to http://tinyurl.com/RiceUniversityoverview.

Urban Farming Flourishes In New York

01:06 PM, May 02, 2017 / LAST MODIFIED: 01:37 PM, May 02, 2017

Urban Farming Flourishes In New York

Tobias Peggs, CEO of Square Roots Urban Growers, speaks about urban farming outside one of the Square Roots containers on April 25, 2017 in New York. The urban farm craze is finding fertile ground in New York, where 10 young entrepreneurs are learning to grow greens and herbs without soil, bathed in an indoor, psychedelic light. Photo: Don Emmert/ AFP

AFP Relaxnews

The urban farm craze is finding fertile ground in New York, where 10 young entrepreneurs are learning to grow greens and herbs without soil, bathed in an indoor, psychedelic light.

In a "hothouse" of invention in a Brooklyn car park, each farms a container, growing plants and vying for local clients in the heady atmosphere of a start-up, fighting against industrially grown food, shipped over thousands of miles.

Meet the farmer-entrepreneurs at Square Roots, a young company with a sharp eye for the kind of marketing that helps make Brooklyn a center of innovation well-equipped to ride the wave of new trends.

"It is not just another Brooklyn hipster thing. There is no doubt the local real food movement is a mega-trend," says Tobias Peggs, one of the co-founders, a 45-year-old from Britain who previously worked in software.

"If you are 20 today, food is bigger than the internet was 20 years ago when we got on it," he adds. "Consumers want trust, they want to know their farmers."

He set up Square Roots with Kimbal Musk, brother of Tesla Motors billionaire Elon, and they have been training 10 recruits since November.

Already well-established in parts of Europe -- the Netherlands in particular -- the technology is still being pioneered in the United States.

The greens are reared in an entirely closed and artificial environment that can be completely controlled, grown vertically and irrigated by a hydroponic system that feeds them water mixed with minerals and nutrients.

Wylie Goodman, a graduate student finishing a dissertation on urban farming at Cornell University, says the US financial capital was a captive market for the innovations.

"It makes total sense," she said. "You've got a well-educated and wealthy population willing to pay a lot for good local food" -- in this case $7 per single pack of fresh greens delivered to your door.

New York and its environs have seen constant innovation in urban agriculture from rooftop gardens to the huge AeroFarm complex in neighboring Newark and Gotham Greens, which grows greens and herbs in ultra-modern rooftop greenhouses that can be harvested before breakfast and on a New York plate for lunch.

Glowing Environment

Halfway through his year-long apprenticeship, Peggs says the 10 young entrepreneurs have already learned how to grow food customers want to buy.

The next stage will begin within a year, he says, with the creation of "campuses" capable of producing greens -- similar to the one in Brooklyn -- in other large US cities before the initiative rolls out "everywhere."

His enthusiasm is contagious. Around 100 people who took part in a guided tour of the farm this week, were for the most part not only willing to shop the greens but also appeared to be mulling over setting up something similar.

But there are downsides to the business model.

If indoor farms can be adapted to grow strawberries and blueberries, "no one with a background in agriculture" thinks they will replace traditional, soil-based farms, Goodman says.

Moreover, products with a denser biomass, such as cereals or beets, are out of reach for the moment. "If I grew beets, I would have to sell it for $50 a head," Peggs joked.

The working conditions are also an issue.

"Do you really want to work in an enclosed, glowing environment?" Goodman asks.

Besides, the lighting is too expensive and cultivation spaces at reasonable cost too few, at least for now.

Those questions are already being addressed by some apprentice entrepreneur-farmers at Square Roots.

Electra Jarvis, 27, joined program after earning a masters degree in environmental sustainability despite having "never grown a plant before."

In just a few months, she mastered the process and already has 20 clients for her bags of salad leaves, tagged "Grown with love by Electra Jarvis."

But if she's happy to learn how to turn "dead space" into "a productive green space," she's not sure it's really for her.

"I miss the nature," she said. "I prefer to be able to grow outdoors."

Urban Agriculture and its Role in Community Building

May 02, 2017

Author of the Month - Global Urban Agriculture, A.M.G.A. WinklerPrins

Urban Agriculture and its Role in Community Building

A.M.G.A. WinklerPrins

Urban agriculture (UA) is about much more than producing food, it is about growing communities and empowering people. The social interactions needed to grow food in urban settings, whether in organised community gardens or allotments, in abandoned lots, sacks, balconies, or berms, brings people together when they might otherwise not have, and this enables them to build trust and community where these notions may be only tenuous. Case material from around the world, in the more developed Global North as well as the Global South, demonstrates this important role for urban agriculture no matter the community. The food produced may alleviate food insecurity and provide access to healthier foods, all of which is important, but perhaps even more valuable is the social interaction fostered via the need to manage spaces of urban cultivation, which can overcome differences between new neighbours and also be leveraged by communities to mobilise for other purposes.

A Personal Vignette

When I first moved to Los Angeles, I went seeking greenspace in the concrete metropolis. While the large green parks were long walks away from my apartment, just a few minutes outside my front door was the ‘pocket’ Unidad Park.

Unidad is dominated by a playground and seating area. But, sitting at the back of the park and surrounded by a low fence lies a wedge-shaped green area with 12 raised beds. When standing inside this tiny urban garden, the buildings of downtown Los Angeles fill the skyline.

The beds teem with heterogeneous offerings: California succulents, roses in bloom, potatoes, mint, leeks, and even young fig trees. All of this belongs to the Unidad Park Garden members.

After finding the park, I decided that joining the community garden would be a great way to learn more about gardening and a way to get to know my newfound neighbourhood. A sun-faded phone number on the park bulletin board yielded that meetings were the first Saturday of each month, and attendance was all it took to join.

When I arrived at my first meeting, the warmth of the gardeners was immediate. Did I have much experience? No, not a problem, there are classes on Saturdays to help me get started. Did I want some food or coffee? Here, have some. Did I want to help with a plot until I could get my own? Rosa is willing to share. Despite a serious language barrier — the garden leaders speak Spanish, and I do not — the small team of gardeners gave me access to the garden and welcomed me to the neighbourhood.

I now check on the garden a few times a week to pick up trash, weed the plots, and water the plants. The leeks and mint have made their way to my kitchen, and I've started taking Spanish lessons. Every meeting teaches me more about my neighbourhood, the plants, the people who have made the garden their own, and by extension the new city in which I now reside.

By L.T. WinklerPrins (24), a recent arrival in Los Angeles, CA

About the book

In one of the first books to consider urban agriculture in a global context, this book brings together material from around the world, illustrating how urban agriculture is much more than growing food. The book opens with an introductory chapter (WinklerPrins) defining urban agriculture and discussing how the topic has been differentially treated around the world, comparing and contrasting UA between the Global North and South.

The first few chapters (White and Hamm; Gray et al.; Parece and Campbell) provide focused overviews of the role that urban agriculture plays in the broader context of urban food systems, including the importance of community gardens. The next few chapters in the book unpack given notions within urban agriculture such as the difficulties of defining ‘community’ consistently (Bosco and Joassart-Marcelli), illustrating the difficulties in consistently mobilising labour for UA (Broadstone and Brannstrom), and developing adequate markets for UA products (Bellwood-Howard and Nchanji). The next few chapters engage with social and environmental sustainability with LeDoux and Conz illustrating a strong link between UA and social justice while Lowell and Law consider how the concept of sustainability is or is not fully engaged in UA; Byrne et al. consider how UA maintains urban ecosystem services while White illustrates how UA creates greater resilience in urban systems.

Other chapters in the book illustrate a number of less expected elements of UA but all contribute to the idea that UA builds community. McLees focuses on the dynamism with which UA is practised while Hammelman links UA to ideas of ‘world cities’ and Gallaher demonstrates how UA creates green spaces even in one of the world’s densest slums. Albov and Halvorson link UA with urban community supported agricultural practices while Dryburgh deliberates the complex role of bees in the city. The chapter by Horowitz and Liu considers the challenge of UA as illegal activity while Mujere points to how UA’s success can be undermined due to political affiliations of its practitioners. Chan et al. elaborate further on the idea of UA as a form of resilience by considering how community gardens are socio-ecological refugia.

In the concluding chapter of the book, WinklerPrins emphasises the point that urban cultivation is much more than producing food and, because of this, points to the need for legal and social acceptance of UA as an urban livelihood, desirable not only for social reasons but also for contributing to the greening of the city and longer term environmental sustainability of cities everywhere.

All photos: L.T. WinklerPrins, March 2017.

North Carolina: The City of Asheville Has Launched The ‘Asheville Edibles Program’

North Carolina: The City of Asheville Has Launched The ‘Asheville Edibles Program’

Linked by Michael Levenston

The purpose of this program is to provide an opportunity for community members to grow food and pollinator plants on publicly-owned land – Adopt-A-Spot – Community Gardens – Urban Agriculture Leases

City of Asheville

Adopt-A-Spot

The City has teamed up with Asheville GreenWorks to provide oversight of the new Adopt-A-Spot program. Businesses, organizations, or individuals can apply to adopt a City-owned piece of property. Once an application is approved, the responsibility of the adopter will be to maintain either an edible or pollinator garden in the location. Adopters will be recognized with a sign at the adopted spot. This program aims to make a positive impact on Asheville by promoting stewardship of publicly owned places.

Community Gardens

Asheville’s Community Gardens Program provides residents with an opportunity to organize community gardens on designated City-owned land. For successful applicants, there is no cost to lease the land, and each garden location has room for several plots. This is a great way to bring a neighborhood and/or organization together to grow local, fresh, and healthy produce to create a stronger, more resilient community.

Urban Agriculture Leases

The Urban Agriculture Leases Program has parcels of City-owned land prepared to be leased at fair market value. The terms of the leases are 3 years with an option to renew. This program is designed to support urban agriculture development to increase local food production and community food security. The City encourages applications from qualified individuals, businesses, and/or nonprofit organizations to apply for a lease agreement. This is a great opportunity for those who want to grow food on a larger scale, but do not have the property to do so.

Build An Apartment Building. Save A farm. This Program’s Doing Both

“Before TDR, landowners had two real estate options: keep farming or sell their land outright - often for development,” Bratton said. “This creates a third choice: farmers can now realize some of the value of their property while retaining ownership and continuing to farm. It’s a win for everyone.”

The historic Reise Farm, at the intersection of Military Road and the Orting Highway. It will be kept as a farm because of the transfer of development rights to the new Stadium Apartments. Peter Haley phaley@thenewstribune.com

MAY 01, 2017 1:43 PM

Matt Driscoll: Build An Apartment Building. Save A farm. This Program’s Doing Both

BY MATT DRISCOLL

On a recent rainy Wednesday afternoon, Amy Moreno-Sills and I are in one of the greenhouses on her 126-acre farm near Orting.

“I’m going to check for some aphids while we’re at it,” she tells me, inspecting rows of upstart tomato plants.

The fledgling tomatoes, and some peppers next to them, will soon make their way to the fields that Moreno-Sills and her husband, Agustin Moreno, have farmed since last year. The organic vegetables they produce here will eventually find their way to places like the Orting Farmers Market, or will be wholesaled to local outfits like Marlene’s Market, Valley Farms, Terra Organics and Charlie’s Produce.

The couple met on a farm, and doing this work, Moreno-Sills tells me, is “a labor of love.”

“It’s part of my identity,” she says. “I’m not happy when I’m not doing it.”

IT’S PART OF MY IDENTITY. I’M NOT HAPPY WHEN I’M NOT DOING IT.

Amy Moreno-Sills, talking about farming

That was the case in 2015, when, despite their best efforts, the couple couldn’t find farmland in Pierce County to call their own. Over the decades, farmland in Pierce County has been disappearing. And much of what remains — thanks to extreme development pressure for housing and warehouse space — is too expensive for new farmers to get their hands on.

“There was nothing available, really at any price. You have to move on,” Moreno-Sill recalls of 2015.

She calls access to farmland “the number one problem” for folks like her.

But this farm is different. Dating back more than 100 years, Moreno-Sills and her husband work the land of the historic Reise Farm, producing organic produce and you-pick blueberries on the first farm in Pierce County protected through the transfer of development rights. It’s called TDR.

Admittedly, the process through which the Reise Farm has been protected — in this case, largely through the work of PCC Farmland Trust, which now owns the Reise Farm and leases it to Moreno-Sills and her husband — can sound a bit wonky. But Nicholas Bratton, a policy director at the regional sustainability nonprofit Forterra described it, in layman’s terms, as “a market-driven approach” to protecting farmland throughout the county.

“Before TDR, landowners had two real estate options: keep farming or sell their land outright - often for development,” Bratton said. “This creates a third choice: farmers can now realize some of the value of their property while retaining ownership and continuing to farm. It’s a win for everyone.”

One of the reasons farmland has become so expensive, and thus difficult to acquire, is because of the development rights that are typically attached to it. These rights allow the land’s owner, or a potential developer, to build homes or warehouses where working farms once stood. This drives up the price and sometimes tempts land owners to cash in on the ballooning value of their fields, trading a farm’s agricultural future for a sizable check.

Through a partnership between the county, the city of Tacoma, and based on the policy work of Forterra, what Pierce County’s TDR program utilizes is the sale of just the development rights attached to working farms, preserving the land’s agricultural use. The development rights are purchased, at market rate, removing the possibility that a valuable farm will one day become tract housing, while a conservation easement protects a farm’s future as a farm.

This process allows landowners to profit from the sale of the development rights, while the farmland is permanently protected, and the future price of the land is lowered — making it accessible to farmers like Moreno-Sills.

She calls the program “the only reason we can farm here.”

RELATED STORIES FROM THE NEWS TRIBUNE

Transfer deal preserves farm, allows Stadium apartment building to grow

It didn’t take long for Tony Carino, a member of the family of developers behind the planned Stadium Apartments, near Stadium Thriftway and across the street from the new Rhein Haus Tacoma German restaurant, to see the appeal of the city’s TDR program.

“When I was 20 years old, I had a backpack, and … we were backpacking around Europe,” Carino recalled. “What I was most surprised by … is how you could get on a bus or train in a city that’s hundreds of years old, and you just get a few minutes outside town and it’s still all farm land, compared to us — it’s all this sprawl.”

“That was 34 year ago, and it still stuck,” he said.

Having grown up in the area, Carino understands the importance of preserving local farmland. But, as a developer, he was also in a position to benefit from Tacoma’s TDR program.

On the county level, the sale of development rights is incentivized, allowing developers — like Carino — to purchase them and then trade them in for increases in height or floor area ratio in their projects here in Tacoma. To make it easier on developers, Pierce County — which has a TDR agreement with the city of Tacoma — operates a “bank” where development rights are purchased and stockpiled, creating a one-stop shopping experience for developers. (King and Snohomish counties have similar TDR programs.)

At its most basic, Tacoma and Pierce County’s TDR program, according to Tacoma planner Ian Munce, accomplishes two worthy goals: It preserves farmland in key agricultural areas, ensuring that working farms forever remain working farms, while simultaneously promoting density in the urban core.

Though Tacoma and Pierce County’s efforts to establish a TDR program date back years, to the Great Recession, Carino became the first developer to actually take advantage of it, purchasing the development rights on about 20 acres of the Reise Farm, and trading that in for permission to build taller at his Stadium District project. The transaction allowed for 21 additional units at Carino’s project.

FOR THE SIZE OF THE PROJECT, IT REALLY HELPED THE BUILDING PENCIL OUT MUCH EASIER.

Tacoma developer Tony Carino

“For the size of the project, it really helped the building pencil out much easier,” Carino told me. “Two or three other developers had (considered building on) the property before us, and they couldn’t make it pencil. (The TDR program) gave us an edge over them.”

“Developers are very risk averse, they don’t want to try something new,” Carino said. “But it was very simple. The city and the county did 90 percent of the legwork.”

While Carino may have been the first Tacoma developer to take advantage of the city’s TDR program, he won’t be the last. A Koz Development project at South 17th and Market streets is also using it for extra density.

“We’ve had conversations with three or four projects that are pretty far along that are interested in doing the same thing,” Munce said.

So far, according to Forterra Conservation Director Jordan Rash, five farms, nearly 500 acres of farmland, have been protected using the county’s TDR program.

“As long as we’re seeing more mixed-use, multi-family buildings, we’re going to see more interest in TDRs,” Munce said. “We’re looking at a 20-year initiative, talking hundreds if not thousands of TDRs, if we can get this program off the ground.”

Back on the fertile land Moreno-Sills farms, the impact of Pierce County’s TDR program is not lost on her.

Gazing out over her 120 acres, hoping for a break in the rain and looking forward to this season’s crops, she’s thankful for the opportunity to be here, thankful for the security the TDR program has provided, and thankful to again be doing what she loves.

“As long as we’re good farmers and good business owners, it’s secure. That’s one of the main reasons we’re able to so heavily invest in startup costs,” she tells me as we walk past a row of peas. “Because we know we have long-term access to this land.”

“I mean, it’s a big deal,” she says.

Matt Driscoll: 253-597-8657, mdriscoll@thenewstribune.com, @mattsdriscoll

Vertical Farming in Amsterdam

Vertical Farming in Amsterdam

GROWx Labs Opens in April 2017

Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Friday 24 March 2017 – GROWx is the leading innovator in vertical farming in the Netherlands will open GROWx Labs in Amsterdam Zuid Oost.

It is amazing that so much food arrives into cities every day, but it is not without problems. Farmers are far away from their market, there are negative ecological effects caused by modern farming, and collectively farms are the single largest users of land in the economy. Faced with limited fresh water resources and limited land to farm, we have to pioneer new ways to farm.

Today, local for local farming producing clean food is the new organic. People desire to know where their food is coming from and if it is clean of undesired chemicals. Urban farms are rising in cities around the world on roof tops and community space. Vertical farming, pioneered in the USA and Japan, is a new way to grow food year round for daily fresh products.

Jens Ruijg, engineer, and John Apesos, entrepreneur, founded GROWx in April of 2016 to build Netherland´s first production vertical farm. The project is focused on serving Amsterdam´s Chef community fresh greens. The GROWx Labs facilities opens in April for Amsterdam´s Chefs to taste interesting varieties of fresh greens and salads.

The Netherlands is a leader in horticulture technology. The GROWx Amsterdam project capitalizes on local expertise, suppliers and university eco-system to build next generation greenhouse technology in the form of vertical farming. Amsterdam has an opportunity to lead the revolution for a fresher urban food future.

GROWx:

GROWx BV is on a mission to accelerate the advent of sustainable urban agriculture. GROWx BV works in co-designing, implementing and operating sustainable vertical farming solutions for city scale food production. We are innovating in indoor food production technology involving multiple layers, controlled plant climates and LEDs.

See more on https://www.instagram.com/grow_x/

Press Contact:

Name: John Apesos

Mobile: +31 06 38 313 515

Email: john@growx.co

Local Farm Grows Mushrooms Indoors

Local Farm Grows Mushrooms Indoors

Southern Tier Mushrooms sells to stores, restaurants

By RYAN MULLER - APRIL 30, 2017

Finding its own place in the growing Binghamton area food scene, Southern Tier Mushrooms is sprouting fresh, gourmet mushrooms to be sold and served in local stores and restaurants.

“The main goal of Southern Tier Mushrooms is to produce gourmet mushrooms locally to the Southern Tier region,” said Director of Operations Eddie Compagnone, ‘15. “When people are looking for a fresh-quality mushroom, they definitely would find us attractive.”

Located in a house on the South Side of the city of Binghamton called The Genome Collective, Southern Tier Mushrooms grows its crop in a basement-turned-mushroom farm. The Genome Collective house looks like an ordinary house at the surface, with a living room, kitchen and even a house dog — but in the basement is a laboratory setup with dozens of mushrooms stacked on shelves.

Compagnone, a member of The Genome Collective, described the house as a community with the common goal of food justice, and a commitment to the idea that communities should assert their right to eat fresh, healthy food. The owner of Southern Tier Mushrooms, Bill Sica, rented the basement of The Genome Collective for growing space, and Compagnone and fellow resident, Louis Vassar Semanchik, were drawn to the project.

“[Louis] and I started helping Bill as we were residing here, because we saw potential in his business,” Compagnone said.

The mushroom growing process begins on a microscopic level inside of a petri dish. The mushrooms start out in the early stages of a fungi as a mycelium and grow on sugars inside of the dish. After the mycelium has grown enough, oats commonly used as horse feed are added to provide nutrients to the mycelium and allow it to grow. The matured mycelium is then mixed in a bag with sawdust, to which the mycelium attaches itself, and begins to grow into mushrooms. The mushrooms grow in a closed-off room in the basement called the fruiting chamber. Outside of that room, there is an adjoining space that houses a machine called a pond fogger to create artificial humidity. This replicates the ideal natural conditions needed for the mushrooms to grow.

At their indoor farm, Southern Tier Mushrooms mainly grows oyster mushrooms, but it is also experimenting with other types, like lion’s mane and reishi. The gourmet mushrooms produced by the farm are popular not only for their taste, but also for their health benefits. Compagnone explained that oyster mushrooms can lower cholesterol and lion’s mane mushrooms can restore the myelin sheath in the brain, improving memory.

The farm is currently selling its mushrooms to local businesses like health food store Old Barn Hollow and Citrea Restaurant and Bar, both in Downtown Binghamton. Southern Tier Mushrooms aims to produce fresh mushrooms for businesses in New York, and Compagnone said they are working with five more businesses on possible partnerships. In the future, Southern Tier Mushrooms plans to expand into a warehouse to grow on a larger scale and distribute to as many people as possible.

To Compagnone, sourcing local food allows distributors to provide benefits of health, taste and quality in ways that nationwide distributors cannot, primarily due to the time it takes to transport them and the preservatives needed. According to him, indoor farming is part of a growing trend, thanks to a renewed interest in do-it-yourself food production and concerns about unstable environmental conditions.

“This is what the future of farming looks like,” Compagnone said.

GrowNYC Throwing Open House For New Community Center Project Farmhouse

GrowNYC has an official home — and you’re invited inside.

GrowNYC Throwing Open House For New Community Center Project Farmhouse

By Meredith Deliso meredith.deliso@amny.com April 23, 2017

The organization, which runs greenmarkets and gardens throughout the city and hosts programs on environmental issues like recycling, will celebrate the opening of its new sustainability and education center with an open house on April 29.

Project Farmhouse opened its doors late last year, hosting private events and school programming. At the open house, visitors can get a sense of what kinds of public programming will be on offer down the line, with tours of the space and cooking demos by Peter Hoffman, Gaggenau’s Eric Morales and a chef from Brooklyn’s Olmsted, as well as composting demos, nutrition workshops, recycling games, take-home DIY planters and more.

“We really built this space to be a community center for people to come together around sustainability and healthy eating and all of the programs that GrowNYC is already involved in, in the community,” said Laura McDonald, events director at Project Farmhouse.

Much of GrowNYC’s existing programming focuses on teacher training and student education. The organization anticipates hosting 500 teachers and 2,000 children each academic year at Project Farmhouse. Hands-on programs for students include GrowNYC’s Healthy Food Healthy Bodies series, which features field trips to greenmarkets and discussions with chefs on nutrition and health, as well as programs on renewable energy and farming.

The state-of-the-art space is a lesson in sustainability itself, from a farm-inspired entry archway made using repurposed wood beams to sun tunnels to let in natural light and a kinetic hydroponic wall. A centerpiece is its induction kitchen, donated by kitchen design company Boffi Soho, for cooking demos.

McDonald looks to ramp up public events in the summer, with potential programming like lectures, movie nights and demos from cookbook authors. Having the Union Square Greenmarket just steps from Project Farmhouse is also an advantage.

“There are lots of tie-ins with the market,” McDonald said. “We’re trying to get the farmers in here, doing some demos or talking about what their lives are like. It’s awesome that it’s just a couple blocks away.”

IF YOU GO

Project Farmhouse will host an open house April 29 from 11 a.m.-4 p.m. | 76 E. 13th St., projectfarmhouse.org | FREE

At TED This Week, Two Speakers Got To The Root Of Things

At TED This Week, Two Speakers Got To The Root Of Things

by Nina Gregory NPR | April 28, 2017 12:46 p.m.

Interdisciplinary artist and TED Fellow, Damon Davis.

Getty Images, Maarten de Boer

At the TED Conference in Vancouver this week two TED Fellows talked about putting ideas to work to invigorate marginalized communities from within, while harnessing the collective power, creativity, and good will of residents who want to live in thriving, healthy and safe neighborhoods.

Devita Davison, executive director of FoodLab Detroit, offered a different means of taking action: “transformation and hope: through food.” She began by reminding the audience of Detroit’s apex in the 1950s, when the city’s name itself represented the strength of America’s manufacturing capabilities and ingenuity. “Now, today, just a half a century later, Detroit is the poster child for urban decay.”

Between a shrinking population and decades of disinvestment, Davison pointed to the persistent problem of scarcity for its mostly African-American population. “There is a scarcity in Detroit. There is a scarcity of retail. More specifically: fresh food retail. Resulting in a city,” she said, “where 70 percent of Detroiters are obese and overweight. And they struggle… to access nutritious food.”

Emphasizing the proliferation of fast food and convenience stores — and the shortage of supermarkets and fresh produce — Davison said, “this is not good news about the city of Detroit. But this is… the story Detroiters intend to change. No… this is the story that Detroiters ARE changing. Through urban agriculture and food entrepreneurship.”

Despite — or perhaps because of — deindustrialization and a rapidly shrinking population, Detroit has, what she calls, “unique assets.” Specifically, the city has some 40 square miles of vacant lots. It is close to water, the soil is fertile and there are a lot of people willing to work, people who also want fresh fruits and vegetables. And what’s happening, Davison said, is, “a people-powered grass roots movement… transforming this city to what was the capital of American industry into an agrarian paradise.”

As the audience applauded, Davison continued, “For those of us who are working in urban agriculture in Detroit, Michigan today, our vision for the future of the city is very clear. We’re working to make sure Detroit is the most sustainable, most food secure city on planet earth! And we’re just getting started.”

She detailed some of the grassroots progress underway: more than 1,500 urban farms and gardens where more than just produce is being grown. Community is also being cultivated on these plots of land as people grow food together. Davison invites the audience along, “Come walk with me, I want to take you to a few Detroit neighborhoods, and I want you to see what it looks like… folks who are moving the needle in low-income communities and people of color.”

She showed a photo of Oakland Avenue Farms, in Detroit’s North End neighborhood. It looks like a small city park, except for the abundant plants pouring out of tidy planters and growing in large, green bushes from the ground. Davison described the five acres as, “art, architecture, sustainable ecologies and new market practices. In the truest sense of the word, this is what agriCULTURE looks like in the city of Detroit.”

A $500,000 grant will allow the farm to do everything from designing an irrigation system to rehabbing a vacant house and building a store produce to sell. They’ll host culinary events where guests will not just tour the farm and meet the grower, but have chefs prepare farm-to-table dinners with produce at peak season. “We want to change people’s relationship to food. We want them to know exactly where their food comes from that is grown on that farm that’s on the plate.”

Davison’s tour traverses the city to the Brightmoor neighborhood on the west side of Detroit, a lower income community with about 13,000 residents. In this community, Davison explains, they’re taking a block-by-block approach to addressing the lack of access to healthy food. “You’ll find a 21-block ‘micro-neighborhood’ called Brightmoor Farmway. Now what was a notorious, unsafe, underserved community has transformed into a welcoming, beautiful, safe farmway, lush with parks and gardens and farms and greenhouses.” She showed images of a blossoming youth garden, an abandoned house that’s been painted into a giant blackboard where people draw bright messages for each other and a building the community bought out of foreclosure that’s been transformed into a community kitchen and cafe.

Her final example is a nonprofit organization, Keep Growing Detroit, whose aim is to have most of the city’s produce grown locally. To that end, the organization has distributed 70,000 seeds which helped lead to some 550,000 pounds of produce being grown in the Motor City.

“In a city like Detroit where far too many African-Americans are dying as a result of diet-related diseases,” she acknowledges the progress being made on the food scene there, pointing to Detroit Vegan Soul, a restaurant that grew from delivery to catering to two restaurants that serve plant-based food. “Detroiters are hungry for culturally appropriate, fresh, delicious food.”

Davison ended her time on the TED stage by describing the work of her organization, Food Lab Detroit. They help local food entrepreneurs build their businesses with everything from incubation, to workshops to access to experts and mentors so that they can, “grow and scale.” While acknowledging that Detroit’s problems are deep and systemic, Davison offers some hope: those small businesses, run by people traditionally excluded from the business world, last year provided 252 jobs and generated more than $7.5 million in revenue. Not mention lots of delicious, nutritious meals grown from the ground of what’s for too long been seeded with despair and decay.

Before interdisciplinary artist and TED Fellow, Damon Davis, took to the stage on Monday, an excerpt from his film, “Whose Streets,” was shown. The documentary, about the unrest in Ferguson in 2014, premiered earlier this year at the Sundance Film Festival and will open in theaters on August 11.

Davis began his talk by acknowledging his fear while standing onstage. “But what happens when, even in the face of… fear, you do what you gotta do. That’s called courage. And just like fear, courage is contagious.”

From East St. Louis, Illinois, Damon said that when Michael Brown, Jr., was gunned down by police, he thought, “He ain’t the first, and he won’t be the last young kid to lose his life to law enforcement. But see,” he continued, “his death was different. When Mike was killed, I remember the powers that be trying to use fear as a weapon. The police response to a community in mourning was to use force to impose fear. Fear of militarized police, imprisonment, fines. The media even tried to make us afraid of each other by the way that they spun the story… this time was different.”

A musician and an artist whose work is in the permanent collection at the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture, Davis’ work tells the story of contemporary African-Americans. After the protests had gone on for a few days, he felt compelled to go see what was going on. “When I got out there, I found something surprising. I found anger… but what I found more of was love — people with love for themselves, love for their community, and it was beautiful. Until them police showed up. Then a new emotion was interjected into the conversation: fear.”