Welcome to iGrow News, Your Source for the World of Indoor Vertical Farming

Going Indoors To Grow Local

Going Indoors To Grow Local

Alberta company wants to license its hydroponics-aquaponics system to others

Posted Jun. 15th, 2017 by Barbara Duckworth

Nutraponics employees include aquaculturalist Geoff Harrison, left, plant specialist Stephanie Bach and CEO Tanner Stewart. The company grows fresh produce at its facility near Sherwood Park, Alta. | Barbara Duckworth photo

SHERWOOD PARK, Alta. — Providing fresh local produce to Canadians year round could be achieved with a new farming concept that combines horticulture with aquaculture.

NutraPonics, which opened in 2015 near Sherwood Park, is dedicated to supplying the local produce market and supporting local suppliers.

Since last December, it has been selling fresh romaine lettuce, kale, Swiss chard, basil and arugula every week.

The produce is marketed through the Organic Box, a privately owned company in Edmonton that supplies its customers with individually selected orders of locally grown food through online sales and from a store front.

“Everything is marketed as local. We are 32 kilometres from the Organic Box, so that is as local as you can get,” said Stephanie Bach, a plant scientist with the company.

Added chief executive officer Tanner Stewart: “We are hoping to provide less need for products from very far away.”

Stewart, who invested in the company three years ago, is among about 50 private shareholders in the company, which plans to franchise the concept of growing produce indoors in a controlled environment.

“Our model is to not build our own farms and create a massive amount of in-house production,” Stewart said.

“Our business model is to build and license these facilities.”

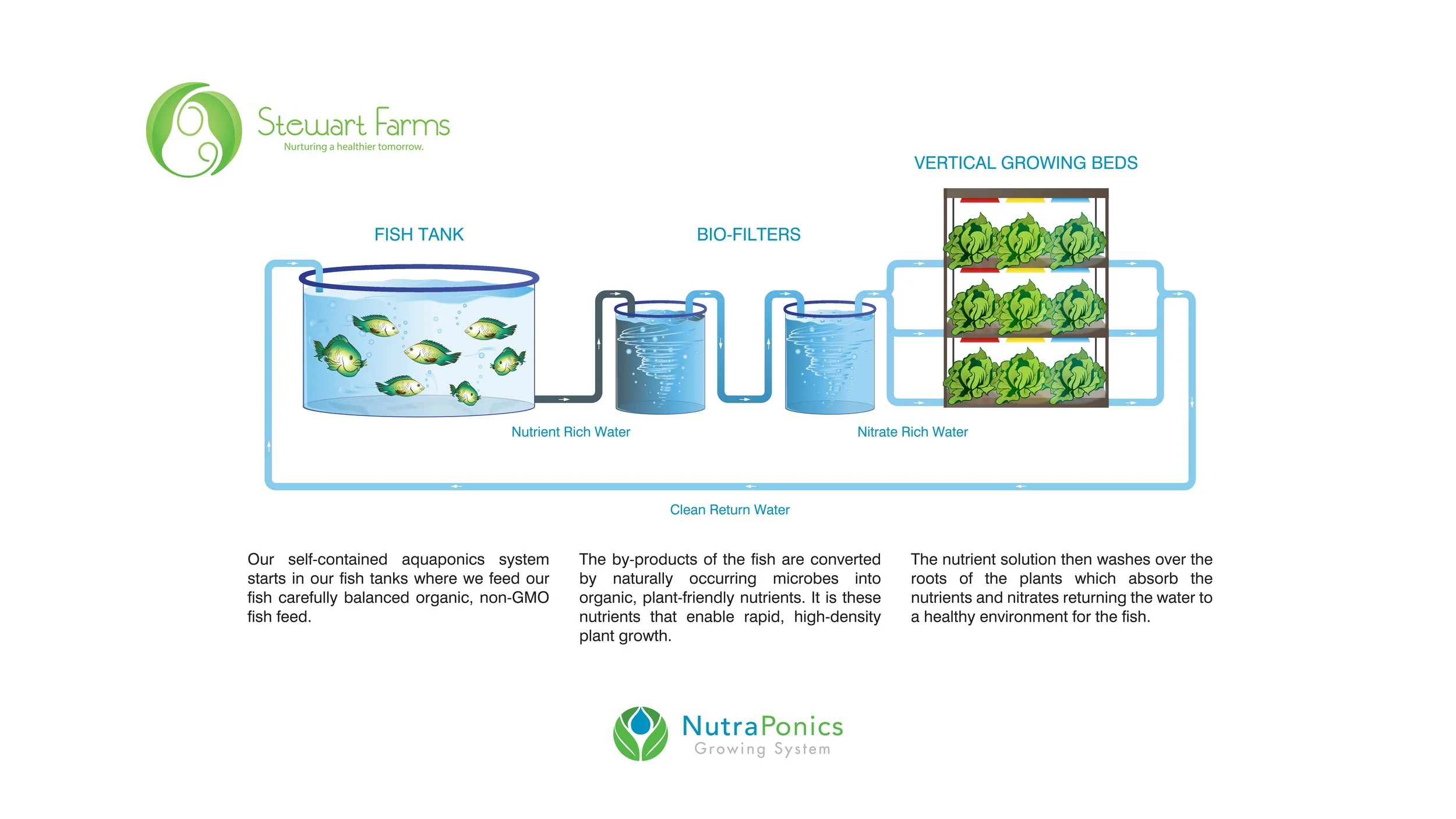

Former CEO Rick Purdy and a company owner started the system. Purdy researched hydroponics to grow food in water and added aquaponics to use byproducts from fish to create a new growing system.

This farm is considered a demonstration facility, where staff can research the best use of the fish, water and plant development.

There are three tanks full of tilapia fish. The nutrient-enriched water from the tanks is delivered to the plants, which are grown in five layers in a controlled atmosphere.

About 1000 sq. metres of growing space are available, where plants are under red and blue LED lights and fed hydroponically.

Under Bach’s supervision, seeds are planted in a special volcanic rock growing medium from Ontario. They sprout within a week and are then transplanted to the main growing rooms. The plants can be harvested within four weeks for same day pickup by clients.

The company employs about 10 people and while each person might have an official job description, the reality is everyone helps with the fish as well as planting and harvesting.

There is no plan at this time to sell the fish.

“The economics of land-based fish farms is fairly fixed,” said Stewart.

“In order to do business, you really have to look at 200 tonnes of production per year to reach economies of scale. This is two tonnes a year.”

This farm sits on 19 acres, but Stewart envisions any empty urban warehouse as a viable growing operation.

NutraPonics is an agriculture company which sells proprietary growing technologies. These technologies utilize symbiotic relationships between plants and fish known as aquaponics to grow nutrient-rich herbs, vegetables and fish in an enclosed, controlled environment. For more information please visit http://www.nutraponics.ca/home

Whitehorse, Yukon, will be the location of the next farm. The goal in the northern community is to grow and sell produce year round at a competitive price with less freight and a longer shelf life.

Stewart also hopes to develop a facility near his hometown in New Brunswick.

The produce is sold at a competitive price. For example, a bundle of romaine lettuce is offered at $6.25 in a 284 gram package.

“You have to be careful in an emerging industry like ours.” Stewart said.

“You really have to make sure you are focused on this as a business, you need to grow your produce at a certain price and you need to make sure your consumers are going to be happy to buy it at that price.”

He estimated that start-up costs are comparable to any new farm and considers this a stable business model with a decent rate of return on investment.

The difference could be a faster turnaround time from construction to the time saleable product is ready.

“Once we get up and running and all the capital costs are done, then we can produce on a consistent basis, week after week, in fairly short order after we turn the building on,” he said.

Indoor Farming Plus Made In USA LED Grow Lights: Profile 1.

Indoor Farming Plus Made In USA LED Grow Lights: Profile 1.4

GREENandSAVE Staff | Posted on Thursday 15th June 2017

This is one of the profiles in an ongoing series covering next generation agriculture. We are seeing an increased trend for indoor farming across the United States and around the world. This is a positive trend given that local farming reduces adverse CO2 emissions from moving food long distances. If you would like us to review and profile your company, just let us know! Contact Us.

Company Profile: Greensgrow Farms

Greensgrow Farms is an urban farm centered around serving its Philadelphia community.

Here is some of the “About Us” content:

Greensgrow is a nationally recognized leader in urban farming and is open to the public year round. Green roof on a composting toilet, honey bee hives atop tool shed, Milkshake the pig, an abandoned house turned office space, an unused church kitchen turned small food business incubator and a deck made from old pallets and water bottles. A laundry list of crazy ideas? Yes. And a day in the life of Greensgrow.

Greensgrow is an Idea Farm that has given birth to our CSA, the Community Kitchen, Greensgrow West and other projects resulting in permanent jobs and sustainable income. One thing that is for certain. There is no typical day at Greensgrow. We have never accepted the idea that “that’s just the way things are”. Instead we believe that’s there’s a way things could be and that we can make them happen if we’re willing to work hard enough, laugh loud enough and be open enough to learn from our mistakes.

We borrow ideas, make them uniquely our own and happily share them with you. Rethinking land, abandoned space, ideas, oil barrels, PVC, tools and trash is what we do. Veggie waste composts into fertilizer, a shipping container grew into a garden shop and rain gutters find a life as a farm. Many things we own, from our 6000 square foot greenhouse to our mobile market trucks, have come from a previous owner. Because we don’t over capitalized on equipment we have been free to change things up. Everything we buy goes through a stringent cost benefit analysis to prove that it can be used at an optimal level. Some people call this cheap, we call it smart.

Here is the link to learn more: http://www.greensgrow.org/.

To date, the cost of man made lighting has been a barrier for indoor agriculture. A new generation of LED lighting provides cost effective opportunities for farmers to deliver local produce. Warehouses and greenhouses are both viable structures for next generation agriculture. Here is one example of next generation made in USA LED grow light technology to help farmers: Commercial LED Grow Lights.

Urban Farming Reaches New Heights At Levi’s Stadium

Urban Farming Reaches New Heights At Levi’s Stadium

Emily Saeger, full-time gardener at Faithful Farms, harvests produce to send downstairs to the Levi’s Stadium kitchens. (Courtesy Isha Salian)

By ISHA SALIAN | PUBLISHED: June 10, 2017 at 7:00 am | UPDATED: June 12, 2017 at 11:11 am

SANTA CLARA — Five varieties of kale. Fresh arugula, lettuces and herbs arranged in neat rows. It’s a typical Californian vegetable garden — except it’s nine stories off the ground. The patch of greens and morning sunlight are juxtaposed against the industrial metals, bright billboard display and giant corporate logo in the backdrop. Levi’s Stadium, the sign proclaims.

This well-manicured garden, planted last year, is the first to top an NFL stadium. The Atlanta Falcons are following suit with a raised-bed garden of their own, and baseball stadiums are already in on the game: Boston’s Fenway Park set up a rooftop garden in 2015, and San Francisco’s AT&T Park boasts a vegetable garden behind center field.

Taken together, the unexpected confluence of professional sports and organic gardening signals just how far the sustainability conversation reaches — but also accentuates the role corporate patronage plays in enabling green urban design. Authentic local food production and energy savings aside, these gourmet, microgreen-rich enterprises are a far cry from the gritty, empty lot urban farms that defined the urban agriculture movement for the last two generations.

Christened “Faithful Farm,” Levi’s Stadium’s rooftop garden opened in July 2016 as a subsection of the stadium’s 27,000-square-foot green roof. As spring planting season nears, Faithful Farm produces 500 pounds of produce per month, on average.

“Originally, this roof was designed just as an ornamental perennial space,” said Emily Saeger, Faithful Farm’s full-time gardener. “It was all grasses and succulents.”

This much lower-maintenance green roof was incorporated into the stadium’s design early on, said Jim Mercurio, vice president of operations and general manager at Levi’s Stadium. Green roofs save energy by keeping the stadium cooler, reducing air conditioning costs. It earned the stadium points for LEED certification (a third-party accreditation for green building design), allowed them to demonstrate a commitment to sustainability and also just looked good.

But then Danielle York, wife of San Francisco 49ers CEO Jed York, had an idea. She had hired urban farming venture Farmscape Gardens to landscape her backyard in Los Altos Hills, and asked Farmscape’s co-owner if she could develop a farm on the roof of Levi’s Stadium. The stadium’s operations team green-lighted the project on May 15, 2016. Just six weeks later, the garden was planted.

“When we looked at what we wanted at first, which was to have a natural garden of sorts, we didn’t take it to the next level,” Mercurio said, looking out over the greenery. “This is taking it to the next level.”

The garden has been expanded twice since it opened in July, and now occupies 6,500 square feet, about one and a half times the size of an NFL endzone—not counting pathways. Food grown in the garden (primarily leafy greens and herbs during the winter months) takes a short elevator ride each day down to the stadium kitchens, where it is used in dishes served at the stadium’s restaurants and private events. “It’s the whole farm-to-fork concept coming to life,” said Mercurio.

A rooftop lettuce supply is only the tip of the iceberg for Levi’s sustainability efforts. The stadium uses 85 percent recycled water, has a solar panel canopy and has received multiple sustainability awards. It’s the first stadium to open with LEED Gold certification, and last year achieved LEED Gold for operations and maintenance too. LEED recognition is a sustainability stamp of approval for the San Francisco 49ers, and can in turn attract more business for the stadium. A 2014 Nielsen survey found more than half of respondents were willing to spend more on products and services from eco-friendly companies. But Mercurio says the stadium’s owners have more in mind than positive publicity.

“Titles are great, being the first to do this or that it’s okay, it’s fine,” Mercurio said. “But it’s part of a greater movement. If someone does it bigger and better than us, we’d encourage that. If we had a role in making the environmental and the sustainability conversation bigger, that’s awesome.”

Farmscape also manages the garden at the San Francisco Giants’ AT&T Park. The company was started nine years ago in Los Angeles, and its Bay Area branch focuses primarily on gardens for corporate buildings and multifamily residences.

“We’d never gotten a project like this; it was so exciting,” Farmscape co-owner Lara Hermanson said. “They have a weather station down here for the roof. This place is the coolest.”

The funding and support from the stadium let Farmscape find its way in the relatively new space of rooftop gardening. “There are plenty of examples of people putting a planter on a roof,” said Hermanson. But gardens set directly onto a standard aluminum roof are much rarer — a 5-year-old East Coast urban farming company is the oldest she can think of. “Really no one has the expertise yet.”

Green roofs, whether or not they include edible plants, have several benefits. They reduce the cost of heating and cooling a building by decreasing the temperature of the roof. They also mitigate the urban heat island effect, which occurs when asphalt roads and concrete pavement and roofs soak up and reflect sunlight as heat, resulting in a higher air temperature in urban centers than suburban and rural areas. If the green roofs grow produce, they also diminish the cost of transporting fresh produce from rural areas to urban centers.

But can a rooftop farm actually grow enough produce to turn a profit? Finding an economically sustainable model for urban agriculture isn’t as easy as reaping the environmental benefits. Getting urban agriculture to support itself solely on the value of its produce is difficult, particularly in places like the Bay Area where land values are high.

Top Leaf Farms, another rooftop farming venture on a residential complex in Berkeley, aims to produce as high a rooftop crop yield as possible, selling the produce grown to high-end restaurants in Berkeley and the building’s residents. These upscale restaurants pay a premium for the hyper-local produce, allowing Top Leaf to sell to locals at lower prices through their website — a pound of beet greens, for example, was priced at three dollars this week.

Co-owner Benjamin Fahrer points out that with Levi’s Stadium, the 49ers paid for the farm’s installation and continue to pay for its maintenance by Farmscape. As part of a much larger system, it doesn’t really matter whether Faithful Farm as an entity is profitable. He says there’s an opportunity cost to having walkways and flowers, as Faithful Farm does — something he must be conscious of as the owner of a for-profit farming company. “As soon as you want to make it look better, your costs go up,” he said.

Green infrastructure expert Elizabeth Fassman-Beck agreed, “If you’re looking for a cost-effective system, you don’t want to waste water on the roof for specific plants because they look good.”

Having less pressure to be turn a profit has perks beyond the ability to plant a row of flowers instead of edible greens. Nonprofit, community-based urbanfarms “are producing a yield of social equity, while we’re trying to get yield that is productively and financially viable,” Fahrer said. These socially productive farms engage the community, save energy and raise sustainability awareness even if they don’t actually net a profit for the owners.

“The environmental impact of urban development is enormous,” said Fassman-Beck, an associate professor at Stevens Institute of Technology, in Hoboken, New Jersey. “Anytime we can encourage leading by example and champion this sort of technology, that’s going to have widespread positive impacts.”

Whether the primary mission of a rooftop farm is to be profitable and environmental friendly, the sustainability benefits remain the same. And though Levi’s Stadium is the first NFL stadium to take this step, major construction projects from all kinds of industries seem certain to follow suit.

“It’s not a surprise to me that the team in Northern California was the first in the nation to be like ‘Let’s do an organic farm,’” Hermanson said. “It’s almost expected now that a world-class venue like this would have their own vegetable garden—their own herb production at least.”

Indoor Farming Plus Made In USA LED Grow Lights: Profile 1.3

Indoor Farming Plus Made In USA LED Grow Lights: Profile 1.3

GREENandSAVE Staff

This is one of the profiles in an ongoing series covering next generation agriculture. We are seeing an increased trend for indoor farming across the United States and around the world. This is a positive trend given that local farming reduces adverse CO2 emissions from moving food long distances. If you would like us to review and profile your company, just let us know! Contact Us.

Company Profile: Farmbox Greens

Farmbox Greens is Seattle's first indoor vertical farm.

Here is some of the “About Us” content: At Farmbox Greens we approach agriculture in an innovative way. We grow in square feet, not acres. We use energy efficient LEDs and a fully climate controlled environment to produce the freshest produce that can be on your plate within hours of harvest.

Since planting the first seeds of our urban farm in 2011 we’ve set out to change where and how great produce is grown. We’ve created a sustainable farm where the harvest cycle is days not months. Our farm uses 90 percent less water than traditional farming, is pesticide and herbicide free and is fresh year round.

Seattle’s first indoor vertical farm to grow produce, we make fresh local greens more accessible. We use a small amount of space (just a few hundred square feet) to grow thousands of pounds of greens annually. We work hard to grow local produce because we think it tastes better. Go ahead and taste it, we think you’ll agree!

Here is the link to learn more: http://www.farmboxgreens.com/.

To date, the cost of man made lighting has been a barrier for indoor agriculture. A new generation of LED lighting provides cost effective opportunities for farmers to deliver local produce. Warehouses and greenhouses are both viable structures for next generation agriculture. Here is one example of next generation made in USA LED grow light technology to help farmers: Commercial LED Grow Lights.

The Future of Farming May Not Involve Dirt or Sun

Farming uses copious amounts of water--70 percent of all freshwater consumed is used for agriculture, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, only about half of which can be recycled after using. It also requires huge swaths of land and, of course, just the right amount of sun. AeroFarms thinks it has a better solution.

AeroFarms co-founders Marc Oshima (left) and David Rosenberg.CREDIT: Ellise Verheyen

The Future of Farming May Not Involve Dirt or Sun

New Jersey-based AeroFarms proposes a radical and more sustainable way to grow the world's food.

By Kevin J. Ryan Staff writer, Inc.@wheresKR

COMPANY PROFILE

COMPANY: AeroFarms

HEADQUARTERS: Newark, NJ

CO-FOUNDERS Marc Oshima, David Rosenberg, Ed Harwood

YEAR FOUNDED: 2011

MONEY RAISED: More than $100 million

EMPLOYEES: 120

TWITTER: @AeroFarms

WEBSITE: aerofarms.com

Farming uses copious amounts of water--70 percent of all freshwater consumed is used for agriculture, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, only about half of which can be recycled after using. It also requires huge swaths of land and, of course, just the right amount of sun.

AeroFarms thinks it has a better solution. The company's farming method requires no soil, no sunlight, and very little water. It all takes place indoors, often in an old warehouse, meaning in theory that any location could become a fertile growing ground despite its climate.

The startup is the brainchild of Ed Harwood, a professor at Cornell University's agriculture school. In 2003, Harwood invented a new system for growing plants in a cloth material he created. There's no dirt necessary--beneath the cloth, the plants' roots are sprayed with nutrient-rich mist. Harwood received a patent for his invention and founded Aero Farm Systems, so named because "aeroponics" refers to the method of growing plants without placing them in soil or water. The company, which sold plant-growing systems, was mostly a side project for Harwood and didn't generate much revenue.

AeroFarms uses LED lighting to create a light recipe for each plant.CREDIT: Ellise Verheyen

In 2011, David Rosenberg, founder of waterproof concrete company Hycrete, and Marc Oshima, a longtime marketer in the food and restaurant industries, looked at the inefficiency of traditional farming and sensed an opportunity. The pair began exploring potential new methods and, in the process, came across Aero Farm Systems. They liked what Harwood had developed--so much that they offered him a cash infusion in exchange for letting them come on board as co-founders. They also proposed a change in business model: Rosenberg and Oshima saw a bigger opportunity in optimizing the growing process and selling the crops themselves.

Harwood agreed. The company became AeroFarms, with the three serving as co-founders. The trio bought old facilities in New Jersey--a steel mill, a club, a paintball center--and started converting them into indoor farms.

Today, each of the startup's farms features vertically stacked trays where the company grows carrots, cucumbers, potatoes, and, its main product high-end baby greens, which it sells to grocers on the East Coast including Whole Foods, ShopRite, and Fresh Direct, as well as to dining halls at businesses like Goldman Sachs and The New York Times. By growing locally year-round, the company hopes it will be able to provide fresher produce at a lower price point, since transportation will be kept to a minimum. (Currently, about 90 percent of the leafy greens consumed in the U.S. between November and March come from the Southwest, according to Bloomberg.) AeroFarms collects hundreds of thousands of data points at each of its facilities, which allows it to easily alter its LED lighting to control for taste, texture, color, and nutrition, Oshima says. The data also helps the company adjust variables like temperature and humidity to optimize its crop yields.

The result, according to AeroFarms, is wild efficiency: The growing method is 130 times more productive per square foot annually than a field farm, from a crop-yield perspective. An AeroFarm uses 95 percent less water than a field farm, 40 percent less fertilizer than traditional farming, and no pesticides. Crops that usually take 30 to 45 days to grow, like the leafy gourmet greens that make up most of the company's output, take as little as 12. Oshima claims that its newest farm, which opened in Newark in May, will be the world's most productive indoor farm by output once it reaches full capacity. Currently, AeroFarms' greens retail for around the same price as similar gourmet baby greens.

AeroFarms employee Samentha Evans-Toor checks the plant growth in a Newark, New Jersey, facility. CREDIT: Alex Kwok

"Most farms don't have a chief technology officer," Oshima says. "We have a dedicated R&D center, plant scientists, microbiologists, mechanical engineers, electrical engineers. We've done our due diligence to create this."

To be sure, as innovative as AeroFarms might be, it's not exactly a practical solution for replacing the world's farms. One big problem is that indoor farming requires huge amounts of electricity, which is not only costly but also offsets much of the good done by preserving water because of the large carbon footprint it creates. AeroFarms acknowledges the drawback but says that it's working to address the problem. The company hired Roger Buelow, the former chief technology officer of LED lighting company Energy Focus, who helped design AeroFarms' customized LED lighting system. "That allows us to be much more energy efficient than anything else out there," Oshima says.

Another challenge AeroFarms faces as it tries to grow is simply scaling the necessary expertise to run these farms. Dickson Despommier, a microbiologist and professor emeritus at Columbia University, first started experimenting with vertical farming--a term that he's widely credited with coining--in 2000. Despommier says that successfully running a vertical farm requires extensive agricultural and process knowledge, which in the case of AeroFarms is provided primarily by Harwood. "Some people think you can just read a book and find out how to do this," Despommier says. "You can't."

That steep learning curve, he says, can create obstacles for companies in this industry. "The biggest issue is finding people who are qualified," he says. "Growers in particular are very hard to find. Who's training them? The answer is, very few places." In the U.S., the University of Arizona, University of California, Davis, and the University of Michigan are among the few institutions that offer courses in vertical farming.

At AeroFarms, that issue is magnified thanks to Harwood's patented growing medium. "No one has direct experience with this," Oshima says. Once the startup finds candidates it trusts to learn the growing process, it has to train them and teach them the company's more than 100 best operating procedures.

AeroFarms' finished product "Dream Greens."CREDIT: Alex Kwok

The company employs 120 people. It has raised more than $100 million to date, from firms including Goldman Sachs and GSR Ventures. Other companies, like Michigan-based Green Spirit Farms and California-based Urban Produce, also sell to consumers using vertical farming methods, though The New Yorker reported in January that AeroFarms had twice the funding of any other indoor farming company--even before its recent $34 million round.

AeroFarms sees its growing method as especially useful in areas where the climate might not be friendly to growing, or where water or land is sparse. The startup currently has nine farms, including locations in Saudi Arabia and China. It plans to reach 25 farms within five years.

"From day one," Oshima says, "this has been about having an impact around the world."

PUBLISHED ON: JUNE 14, 2017

USDA Announces Grants Designed to Increase Amount of Local Food Served in Schools

USDA Announces Grants Designed to Increase Amount of Local Food Served in Schools

June 13, 2017 | seedstock

News Release: WASHINGTON – The U.S. Department of Agriculture today announced the projects selected to receive the USDA’s annual farm to school grants designed to increase the amount of local foods served in schools. Sixty-five projects were chosen nationwide.

“Increasing the amount of local foods in America’s schools is a win-win for everyone,” said Cindy Long, Deputy Administrator for Child Nutrition Programs at USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service, which administers the Department’s school meals programs. “Farm to school projects foster healthy eating habits among America’s school-age children, and local economies are nourished, as well, when schools buy the food they provide from local producers.”

According to the 2015 USDA Farm to School Census, schools with strong farm to school programs report higher school meal participation, reduced food waste, and increased willingness of the students to try new foods, such as fruits and vegetables. In addition, in school year 2013-2014 alone, schools purchased more than $789 million in local food from farmers, ranchers, fishermen, and food processors and manufacturers. Nearly half (47 percent) of these districts plan to purchase even more local foods in future school years.

Grants range from $14,500 to $100,000, awarding a total of $5 million to schools, state agencies, tribal groups, and nonprofit organizations for farm to school planning, implementation, or training. Projects selected are located in urban, suburban and rural areas in 42 states and Puerto Rico, and they are estimated to serve more than 5,500 schools and 2 million students.

This money will support a wide range of activities from training, planning, and developing partnerships to creating new menu items, establishing supply chains for local foods, offering taste tests to children, buying equipment, planting school gardens and organizing field trips to agricultural operations, Long said. State and local agency interest and engagement in community food systems is growing. Having received 44 applications from state or local agencies, 17 state agencies will receive funding.

Grantees include the Nebraska Department of Education, which will refine and expand the “Nebraska Thursdays” program, which will focus on increasing locally sourced meals throughout Nebraska schools, and the Virginia Department of Education, which will focus on network building to ensure stakeholders from all different sectors are leveraged. Both the South Dakota Department of Education and the Arkansas Agriculture Department will use training grants to build capacity and knowledge about the relationship between Community Food Systems and Child Nutrition Programs. More information on individual projects can be found on the USDA Office of Community Food Systems’ website at www.fns.usda.gov/farmtoschool/grant-awards.

USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service administers 15 nutrition assistance programs that include the National School Lunch Program, School Breakfast Program, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), and the Summer Food Service Program. Together, these programs comprise America’s nutrition safety net. Farm to school is one of many ways USDA supports locally-produced food and the Local Food Compass Map showcases the federal investments in these efforts. For more information, visit www.fns.usda.gov.

Ideas We Should Steal: Urban Food Forest

Ideas We Should Steal: Urban Food Forest

Seattle’s Beacon Forest provides free native edibles to anyone in the city. Could the soda tax make it possible for a Philly group to do the same here?

JUN. 05, 2017

Imagine this: On a two-acre plot of land, at the edge of Fairmount Park, sits a forest hearkening back to the days when nature—not people—ruled the planet. Fruit trees tower over berry shrubs, fruit-bearing vines creep upwards. Insects, birds, animals fill the spaces in between. And every day, scores of Philadelphians wander through, filling their arms with fresh produce to take home—all for free.

This is the vision of a group of Philadelphia food access advocates—and it’s not as crazy as it seems. In fact, there’s precedent in Seattle.

Beacon Food Forest, in Seattle’s Beacon Hill, will be the largest food forest on public land in the country when it is complete. So far, it occupies two acres of a seven-acre plot sitting above a covered reservoir in South Seattle; this summer, the mostly volunteers who maintain the forest will plant another two acres. The garden contains 420 different species of edibles, some native to Seattle, like rasberries, huckleberries and walnuts, and some a reflection of the surrounding communities of Chinese, Vietnamese, Somalians, Latinos and African Americans, like Chinese pepper trees, persimmons and figs. Everything grown at Beacon Forest is free to anyone and everyone who wants to pick it at anytime.

Muehlbauer says he is hopeful that the city will grant his group a couple of acres in Fairmount Park to launch a food forest. And it is conceivable that the city could help to fund Fair Amount Food Forest with revenue from the tax on sugary beverages, a portion of which is slated for public park improvement.

“The goal is to create community and awareness around a local food supply, what you can grow that you don’t get in grocery stores,” says Glenn Herlihy, the forest’s co-founder. “It’s social healing and land healing at the same time.”

Beacon Forest is an example of permaculture, which means it is self-sustaining and perennial. The idea came out of a permaculture workshop Herlihy took in 2009, when for his final project, he decided to design a dream farm on an undeveloped piece of land next to a large park in his neighborhood of Beacon Hill. He passed the class, and then took his idea to the community, where he found a willing group of residents who decided to make his dream a reality. In 2012, after securing permission from Seattle Public Utilities and $140,000, mostly from the city’s Department of Neighborhoods, Beacon Forest broke ground.

Five years later, Beacon has become a model of urban forestry that holds two principles steadfast: Remaining true to the land, and to the community it serves. “In a food forest, you’re looking for collaboration between the community, what you can grow and what’s available,” Herlihy says. The plantings utilize what ecoloigsts call the seven layers of a food forest—trees at the top, ground cover at the bottom with shrubs, pollinators, vines in between. Those plants then propagate naturally, and shift—where berry bushes used to be most prominent, the trees have now blocked the sun, and have started providing more of the fruit. The land is also becoming what Herlihy calls a “genetic food bank” for edible plants that are dying around the globe.

All of it—the planting, the upkeep, the harvesting—depends on the community. Only a few workers, like construction managers and teachers, receive occasional stipends. The rest of the 80 or so regular planters are volunteers from all over the city. Meanwhile, the food grown is picked regularly by neighbors, and anyone else who travels to South Seattle. How many people have eaten from the garden is unclear since it is unmonitored, on public land, and free.

“There are people in the city who don’t know how to use a shovel, never planted a tree, but really want to,” Herlihy says. “They haven’t had that experience of being able to forage in a public area, and the joy of finding a bunch of berries that they’ve never had before, like a goji berry. It’s an amazing experience.”

Like so many projects of its kind, Beacon was made possible by several different factors: A dedicated group of volunteers; a city willing to work with them; and available public funding, partly as a result of a levy approved by voters to make improvements to Seattle’s many parks.

That’s what makes this such an optimal time for a group of Philly volunteers working to develop what they call Fair Amount Food Forest, a publicly accessible food forest in Fairmount Park. Formed a little over a year ago by Michael Muehlbauer, a landscaper, farmer, and builder who was a core Beacon Forest member when he lived in Seattle, the initiative is in the very early planning stages—talking to the city, forming partnerships with like-minded organizations, reaching out to neighborhoods that abut Fairmount Park to see who, if anyone, would want something like the Beacon Food Forest in their community.

Muehlbauer, a Wisconsin native who had an edible landscaping business in Seattle, says he realized about six months after moving to Philly that this city—vastly different from that on the west coast—could be ready for this. “The people I’ve met and consistent, random conversations made me think, ‘We needed you at Beacon,’” Muehlbauer says. Those people now form the core of his planning group. “I realized we could do this really well here, maybe even better than in Seattle.”

Beacon contains 420 different species of edibles, some native to Seattle, and some a reflection of the surrounding communities of Chinese, Vietnamese, Somalians, Latinos and African Americans. Everything grown at Beacon Forest is free to anyone and everyone who wants to pick it at anytime.

Muehlbauer says he is hopeful that the city will grant his group a couple of acres in Fairmount Park to launch a food forest. And it is conceivable that the city could help to fund it with revenue from the tax on sugary beverages, a portion of which is slated for public park improvement. Like Beacon in Seattle, though, the city has first asked them to find other community partners and to get neighborhood buy-in for the project. Fair Amount is spending the next few months talking to residents who would be most affected by a public forest. “We don’t want to create this somewhere if no one wants it,” Muehlbauer says.

If Fair Amount gets off (into) the ground it would take Philly’s urban gardening movement to a whole new level. First there were community gardens, often built on empty lots across the city. Then urban farming took off, led by Fishtown’s Greensgrow Farms, which opened in 1997. The Philly Orchard Project launched 10 years later, and has now planted nearly 60 tree and berry farms on empty lots throughout town, harvesting some 3,000 pounds of fruit a year. A public food forest would go even further: Native plants set on to grounds that are, always, open to the public, for anyone to reap as they see fit.

And unlike Seattle, a relatively wealthy city with little unused land, Philly is ripe for a food farming revolution: The city has some 40,000 vacant lots, acres of land that are mostly eyesores. It also, despite incredible efforts on the parts of several groups, still is home to several food deserts, neighborhoods in which it is difficult and expensive for residents to access fresh produce. And many of those residents are the ones most in need: The 26 percent in poverty, with the host of ailments that go along with the city’s worst and most unshakeable problem. Fair Amount would not solve all of these problems But it could be part of an environmental, social and nutritional answer to many of the issues the city faces.

Herlihy says that when they first proposed the idea of Beacon Forest, they were asked about how to handle people who might want to take, for example, every blueberry in the garden. But Herlihy says it hasn’t been an issue. Plants are scattered throughout the forest, so grabbing any of one species would be more complicated than simply walking in with a big box to fill. And, anyway, it wouldn’t be an issue.

“If they’re coming in and taking it all, that means there’s a demand,” Herlihy says. “It means there are people who are hungry and need it, and that we should be doing more. We need more abundance to serve the need. We’re here for everyone.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated that Beacon is the largest sustainable farm on public land in the country. It will be the largest food forest when it covers the full seven acres; right now, it occupies two acres.

Header photo: Volunteer planters at Beacon Food Forest. Courtesy of Beacon.

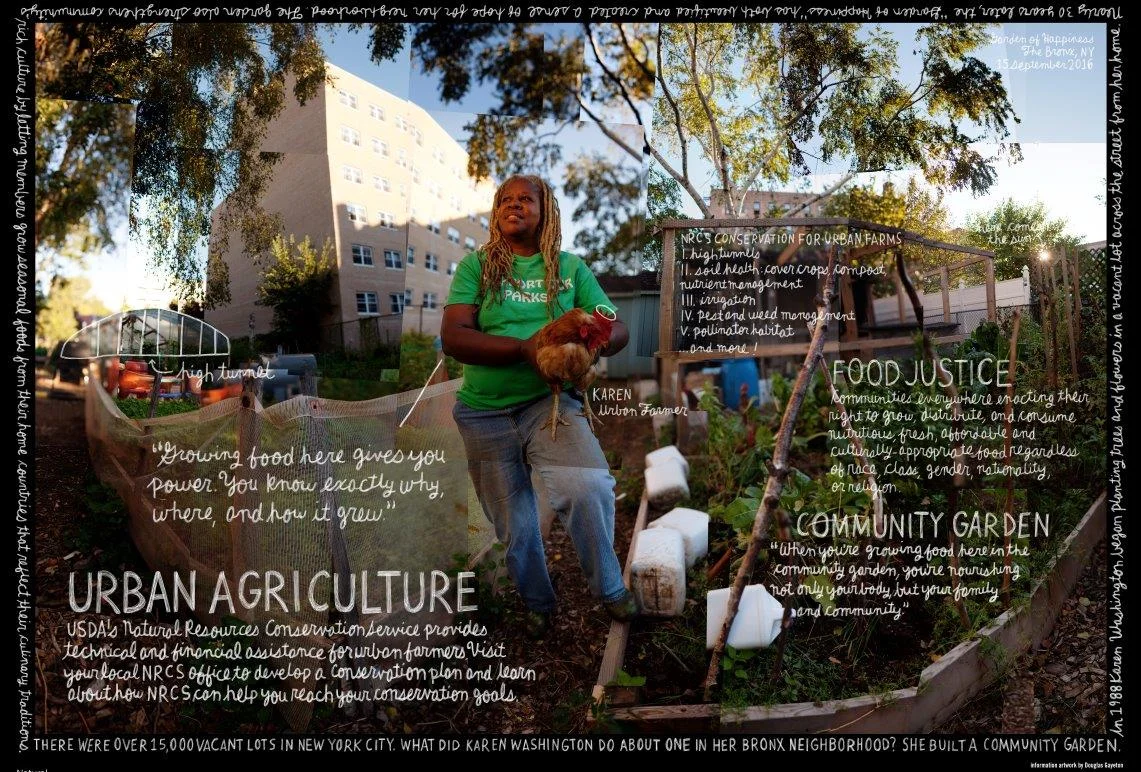

Urban Agriculture

Urban Agriculture

Image credit: Douglas Gayeton

Urban agriculture pioneers are taking action in their communities, growing not only fresh, healthy produce, but also providing jobs, beautifying their neighborhoods, and offering access to fresh, healthy food in areas where grocery stores are sparse.

As American agriculture continues to grow in new directions, NRCS conservation assistance is growing along with it. NRCS provides technical and financial assistance for assistance for urban growers in areas such as:

- Soil Health

- Irrigation and Water Conservation

- Weeds and Pests

- High Tunnels – NRCS can provide financial assistance for high tunnels, used to extend the growing season and to protect plants from harsh weather, air pollution and pests. By making local produce available for more months in the year, fewer resources are used to transport food to plates. Visit the NRCS High Tunnels website.

Resources:

- USDA Urban Agriculture Toolkit

- Fact Sheet: NRCS and Urban Agriculture (PDF, 4 MG)

- AMS Urban Agriculture Website

- Success Stories

Get Started

Starting an urban farm comes with a unique set of challenges and opportunities. NRCS can help with the challenges of conservation, and support urban farmers in their efforts to achieve local, healthy, sustainable food for their communities.

Start by contacting your local NRCS Service Center.

Success Stories in Urban Agriculture

Learn about urban farmers who have worked with NRCS. Read our stories.

“Stronger and More Resilient,” The Future of CropMobster With Co-Founder Nick Papadopoulos

“Stronger and More Resilient,” The Future of CropMobster With Co-Founder Nick Papadopoulos

Founded as a resource to prevent food waste, the CropMobster network has grown into an online platform for farmers, food activists, and pantries to exchange resources. Designed to “ignite food system crowdsourcing,” CropMobster empowers local leaders to connect communities interested in sharing or trading goods, labor, excess food, events, and news to help end hunger and reduce food waste. CropMobster was established in the in 2013 and has expanded to serve farmers and local food leaders throughout California and the West Coast.

Food Tank interviewed CropMobster CEO and Co-Founder Nick Papadopoulos to learn about the recent additions to CropMobsters’ sustainable food networking platform since Papadopoulos spoke at Food Tank’s 2016 Farm Tank Summit in Sacramento.

Food Tank (FT): Describe CropMobster’s evolution over the last four years. How has CropMobster’s network expanded from its original purpose?

Nick Papadopoulos (NP): For starters, my wife Jess and I had no clue that we’d be hawking and selling shirts like Re-Pear the System and Talk Dirt to Me. CropMobster started on my family’s farm in 2013 as an instant alert and crowdsourcing system. I was in the veggie cooler and saw a few boxes of perfect produce about ready to get chucked, and it drove me insane enough to take action. At that time our singular purpose became one of using technology to rally community members to make sure food at risk of going to waste found a home, either through flash sales and donations or activities like gleaning or bartering.

This food waste prevention focus remains core to our work. However, individuals, small businesses, and nonprofits started using our platform for many purposes and at many scales—from fundraising and jobs to product sales, crowdfunding, sourcing animal feed, and events. What we heard from folks and what we saw in the data was the need to support a range of food system transactions, relationships, and actions. In one typical day, we might help broker five tons of oversized cucumbers for donation, help sell pork for a local pig farmer, find candidates for a non-profit looking for a new operations director, or locate a lawn mower for a community garden.

The next learning [curve] came when we realized that our greatest impacts were occurring when we had local, inspired leaders facilitating the CropMobster exchange in their communities. Sort of like a traditional ombudsperson but with some new gear, we call ourselves Food System DJ’s or Switchboard Operators. Ideally, this position works just as much out in the streets and fields, as behind a screen managing their exchange. But this on-the-ground role in communities is highly interdisciplinary and takes a diverse skillset. We needed to train people to do this work. So we designed CropMobster University, and we began looking for complementary models—like Economic Development Agencies, universities, or Local Food Councils—to partner with us.

This brings us to today, where CropMobster is hungry to partner with bold community leaders like universities or Food System Councils to launch and manage inspired local food networks or community exchanges.

FT: How is CropMobster training and growing local food leaders? In what ways have you seen these local food system Switchboard Operators benefit their communities?

NP: In 2016 we launched CropMobster Sacramento in partnership with an exceptional regional non-profit called Valley Vision. They had received grants from the Wal-Mart Foundation and Bank of America to begin working with CropMobster. Two Valley Vision team members, Robyn Krock and Adrian Rehn, took our training and began working as Switchboard Operators out of their region’s exchange. One day a local gleaning organization called Harvest Sacramento posted that there were 30,000 lbs of watermelons they had the opportunity to glean the next day from a generous farmer’s field. There wasn’t a lot of time. A sizeable volunteer mobilization was needed. Adrian moderated and published the alert but then leveraged his connections and within a few hours over 20 volunteers rallied and gleaned a huge volume of watermelons which Harvest Sacramento delivered to the Sacramento Food Bank and Family Services.

As part of the University of California’s Global Food Initiative we have received a multi-year commitment to run CropMobster Mercedin partnership with the University of California Merced Campus. Here’s what leaders in this community are thinking about the potential CropMobster Merced can bring to their community. Members of the Merced Community, like Bill Gibbs, the Executive Director of Merced Food Bank, have commented, “Merced County is one of the most impoverished counties in the state, with at least 35 percent food insecure population. I am thrilled that CropMobster & UC Merced have decided to launch the Merced Community Exchange to serve organizations like ours. With this effort, we anticipate growing our own capacity for impact at the food bank but most importantly helping to grow the capacity of our 100-plus partner agencies who daily need support in meeting the needs of the food insecure. Whether helping us grow a gleaning program, raise funds, or source food donations, we anticipate that this platform and trained team are going to be a tremendous asset to our Food Bank and our community, and we are grateful.”

FT: How is CropMobster helping form an alternative food system economy? Why is this essential?

NP: I can humbly say that, after facilitating thousands of impacts large and small, it is without a doubt clear to me that local food systems can grow stronger and more resilient by having community-led exchanges guided by trusted, local leaders to support new connections and solutions. There are so many great projects, initiatives, and organizations in each foodshed working on crucial pieces of the puzzle. From food waste reduction to local economic development, having a free shared communication, and an action platform that helps bond these efforts together is something any community can benefit from and needs.

Former Farm Tank Summit Sacramento speaker and CropMobster CEO Nick Papadopoulos explains CropMobster’s growth as a sustainable food movement platform.

FT: Since its founding, how has CropMobster helped reduce and raise awareness of waste in the California?

NP: I think we forget that from a true problem-solving standpoint there are many ways to scale and help drive lasting change. One way—and I think everyone needs to take a big gulp of this one—is to set your ego aside, set an example of action, and generate a powerful story that others learn from and feel inspired by. In this sense, I am honored that the story of Jess and I seeing food go to waste in our community and deciding to act was shared throughout the world in our first few years. From TIME magazine to Central Chinese TV, the story and vision were spread widely. While the CropMobster communities we have running have found a home for millions of pounds of food at risk of going to waste, I think our largest impact has been that our story scaled at just the right time to help spark a wave of innovation, awareness, and action.

And now, four years since our start, we feel grateful and blessed that our small team has made it through our version of “Survivor” to keep working, driving impact, and supporting communities.

FT: In what ways do the initial goals of CropMobster still guide your work today?

NP: From the get-go, we have had the goal of reducing food waste by driving sales, donations, trading, and making connections. This remains a core part of our values and organizational DNA. But beyond food waste, we also to realize we are wasting a huge amount of human and community potential and leaving a huge reservoir of value on the table for communities to realize.

We also believe in the value of community capacity and relationship building. Each day we wake up thrilled to have the chance to help folks out even in situations where there isn’t a dollar involved but other forms of value like new relationships. It’s our favorite job in the world, and we want to reach everyone who wants to team up. That’s the goal; easier said than done though.

FT: What are your hopes for the future of the CropMobster network?

NP: Each week we get requests for what we do from all over the U.S. and the world. We want to more easily serve these folks and see that these communities get the help they need.

This year we aspire to expand to the entire state of California (and are working to recruit sponsors) and partner with two to four counties or regions to begin expanding to other states and countries. Also we are looking for a trusted, global non-profit organization with a wide reach to team with us to more rapidly expand our reach and fundraising, and with this in place, inspire more donors and social impact investors to take part in this journey.

With a few more pieces and partnerships in place we can more rapidly deploy our technology and educational model to food systems throughout the world, most ideally via regional university partners or local food councils. As mentioned this is a very exciting path because, not only can we help spark immediate food system impact, but also help sprout the next wave of food system leaders.

To learn more about Nick Papadopoulos and CropMobster’s work supporting local foodsheds, listen to his recent interview with the Peak Prosperity Podcast.

High-Tech Farms In Singapore Take On Cold-Weather Crops

High-Tech Farms In Singapore Take On Cold-Weather Crops

Kale is touted as a "superfood", eaten in salads and sandwiches, blended in green juices and even baked into chips.

08 Jun 2017 04:49PM (Updated: 08 Jun 2017 11:18PM)

SINGAPORE: Kale is touted as a "superfood", eaten in salads and sandwiches, blended in green juices and even baked into chips.

The trendy greens are typically grown in temperate countries such as Australia and the US, but with the help of technology, such cold-weather crops - which typically would not survive in Singapore's climate - are now being grown in some high-tech vertical farms.

Local farms currently produce 12 per cent of Singapore's total vegetable consumption, exceeding the 10 per cent target set in 2009.

In line with the Government's push for farming productivity - such as the recently enhanced Agriculture Productivity Fund and the announcement that farmland would be set aside to promote high-tech farming - more farms are exploring new methods to grow crops previously thought to be impossible to cultivate in Singapore's climate.

One such farm is Sustenir, which grows hydroponic crops in a fully controlled environment. This includes making use of technology such as LED lights, air-conditioning ducts and an automated irrigation system to grow temperate produce such as kale, cherry tomatoes and strawberries.

Co-founder Benjamin Swan explained that the firm leverages technology to manipulate every facet of growth within the room, from humidity and temperature, to the nutrients in the water.

This has helped the farm cut the growth time of crops to two weeks - half the time needed at conventional farms - as well as customise its crops to fit customer preferences. For example, it has successfully modified the naturally fibrous and indigestible stems of kale crops to become edible.

Da Paolo Group is one eatery chain that sources its kale from the farm, and its group executive chef Andrea Scarpa said he found the produce "very comparable" to that found overseas.

"The taste profile is very, very similar to what we get imported. But for us it's even better, simply because you get to eat the entire plant from the top of the leaf down to the root," he explained.

"Traditionally when you eat kale you import from overseas, you'd have to rip off the stem, which is a huge waste - 50 per cent of your weight gone. But it's great (that) we get to use the whole thing when it's done locally.”

The 740 sq m farm, which is located in an industrial building, also plans to expand to tailoring edible flowers and micro-greens for its customers.

Workers sort out kale produce at Sustenir. (Photo: Wendy Wong)

Another vertical farm thriving on technology is owned by Japanese electronics company Panasonic. The 1,154 sq m farm currently grows 81 tonnes of produce annually under its brand Veggie Lite, which supplies its vegetables to supermarket chains, hotels and restaurants. This includes more than 30 crop varieties such as green and red lettuce, swiss chards and sweet basil.

"By adopting technology from our parent company in Japan, we are able to control light, temperature and humidity to ensure optimum conditions,” a spokesperson for the farm told Channel NewsAsia.

"Through local production, we have the control to produce a stable supply of safe, fresh, high-nutrition and high-quality vegetables," the spokesperson said. "As importation involves more third parties and logistics arrangement, there are more concerns to be considered in ensuring the produce quality and freshness."

Veggie Lite aims to contribute 5 per cent of local vegetable production - or about 1,000 tonnes annually - by 2020.

Future Of Food: How Under 30 Edenworks Is Transforming Urban Agriculture

JUN 1, 2017 @ 03:45 PM

Future Of Food: How Under 30 Edenworks Is Transforming Urban Agriculture

Tim Pierson

Jason Green, 27, and Matt LaRosa, 23, are the CEO and Construction Manager of Edenworks.

When Matt LaRosa joined Edenworks in early 2013, he was a college freshman who still hadn't even picked a major. But when he overheard CEO Jason Green at a pitch competition explain his plan to transform industrial buildings into high-tech farms, he immediately abandoned his own pitch and pitched himself to Green instead. The duo, along with cofounder Ben Silverman, went on to create the self-regulating aquaponic system that now supplies microgreens and fish to Brooklyn and landed them on this year's 30 Under 30 Social Entrepreneurs list.

The Edenworks HQ is not exactly where one would expect to find fresh produce and fish. Located in the Bushwick area of Brooklyn, the company sits atop a metalworking shop belonging to a relative of Green. Their office looks like a typical young startup: all eleven employees crowded in one room with computer screens occupying almost every surface. But upstairs across a narrow walkway is where the magic really happens: an 800 square foot greenhouse, custom built by LaRosa, housing fish tanks, vertically stacked panels of microgreens, and a sanitary packaging unit. Though admittedly cramped, the company says their size has made the team significantly more lithe than larger industrial agriculture operations.

"Being a startup, you have a ton of room to break things and iterate very quickly," LaRosa told Forbes. "We're so nimble with changing our prototypes... we have something different than anywhere else in the entire world."

Currently, about 95% of leafy greens consumed in the US are grown in the desert regions of California and Arizona. Most of these products are grown for mass production and durability in transport, rarely for quality or sustainability. Urban farms have cropped up as way to provide growing metropolises with fresher produce in a way that is better for the environment.

The Edenworks model differentiates itself from other urban farms in that it is a complete, aquaponic ecosystem. Waste from the tilapia fish is used as a natural and potent fertilizer for the microgreens planted on vertically stacked power racks. They have no need for synthetic fertilizers or pesticides that can diminish the nutritional quality of produce.

"The water table is falling every year, there's a huge amount of money invested in pumping water out of the ground and irrigating, and inefficiency in the supply chain where a lot of product gets wasted or left in the field," explained Green, a former bio-engineer and Howard Hughes research fellow. "We eliminate all of that waste."

A common phrase in the office is turning factories into farms instead of farms into factories, and many of their design challenges have been combated by embracing the industrial nature of the location. Indoor farms are often criticized because they can't make use of the natural processes used in traditional farming. But the team has invested in studying ancillary industries to find the lowest cost and highest return methods of mimicking the natural processes, like using custom LED lighting to emulate sunlight.

The research has paid off. In the current iteration, Edenworks is able to harvest, package and reach consumers within 24 hours. By cutting down on transport and prioritizing quality over durability, the greens are also up to 40% more nutrient dense than traditional produce.

For now, their largest barrier is clear: space. With $2.5 million in funding to date, their tiny greenhouse has managed to consistently service the local Whole Foods with two varietals of microgreens. In the winter of 2018 though, they plan to move to a space 40 times the size and simultaneously roll out five additional product lines across the NYC area.

The plans for the new building have been delayed a few times, but with LaRosa graduating NYU last month and joining the team full time, Green is confident they are on track to hit their deadline. The larger facility will be the result of years of planning that will incorporate new technology that will allow them to become even more efficient and competitive in the market.

"What we've developed is a huge amount of automation that will allow us to bring the cost down for local indoor grown product into price parity with California grown product, and that's really disruptive," says Green. "If we want to move the needle on where food comes from in the mass market, it has to be cost competitive. We want to be the cost leader, we want to bring the cost down."

The Green Bronx Machine

The Green Bronx Machine

BY GGWTV ON MAY 30, 2017

In the years of creating episodes for our national television series, Growing a Greener World on PBS, we’ve had the privilege of meeting and featuring some of the world’s most genuine heroes to tell their extraordinary stories.

Each is doing something incredible for people or the planet through organic gardening, healthy food, nurturing sustainable lifestyles and more.

Stephen Ritz – The man with the ever-present cheese hat, and founder of the Green Bronx Machine. And perhaps the most tireless man we’ve ever met.

Then along came Stephen Ritz, educator, creator, and founder of the Green Bronx Machine. It’s the term given to his one-of-a-kind incredible learning environment, originally started and still growing strong in the Bronx and now spreading out around the world.

On breaks from college, Daughter Michaela Ritz is an ever-present force of her own at CS-55.

Over the three days our crew was embedded in CS-55, the school where Stephen voluntarily spends most of his life (along with his wife Lizette and adult daughter Michaela), our unique perspective allowed witness to a man fully present in his life’s mission—to nurture his students with love and respect. It moved us to tears more than once as we savored every moment of joy and energy radiating from his students in response.

Former White House pastry chef Bill Yosses has become an integral part of the Green Bronx Machine volunteer force.

It only takes a moment after meeting Stephen to know that this is a man devoted to changing the lives of his students. Through passion, patience, and the power of a plant that produces real food (as in fresh fruits and vegetables), Stephen Ritz and his Green Bronx Machine are building healthy minds and bodies and empowering thousands of children to discover and exploit the potential they never knew they had.

Stephen Ritz is like the Pied Piper. Students savor every moment of “Mr. Ritz time”.

Although this episode packs a lot into a 22-minute show, you can learn much more of the story behind it all. The Power of a Plant is the recently released book on the extraordinary journey of Stephen Ritz—indeed one of the world’s most genuine heroes and important role models of our time.

A personal note from Joe Lamp’l

To all of you who watched this episode to the very end, this one got me as you now know. After days of seeing so much love from students to teacher, and back again, it was a lot of emotion to keep bottled up. We made two separate trips to NY to finish this episode. After returning home from the first trip I truly was emotionally spent. Knowing I was going back for another round, just added to what was already still inside me.

These hugs happen every morning. You can tell some of the students really need these. What a way to start the day.

I wish you could have seen what I saw and will never forget over those three days. This image I call “the hug” was just the tip of the iceberg on what I was able to experience. After witnessing many more scenes like this, I plan to give more hugs and hopefully get more hugs. While the “power of a plant” is truly an amazing thing, you still can’t replace the incredible power of a hug. Thankfully, Stephen Ritz is good with both.

Links to related information from this episode and post

The Power of a Plant – Stephen Ritz’s newly released book

The Green Bronx Machine blog post by Joe Lamp’l

Houses Squeezing Out Farms

Mike Chapman.

If too many houses replace vegetable growing operations, we may have to look at alternatives such as vertical farming, says Horticulture NZ chief executive Mike Chapman.

He has always been sceptical about such methods for NZ, but we may be “stuck with it” if urbanisation keeps taking productive land, he warns.

Vertical farming was among the most interesting sessions at the Produce Marketing Association (PMA) ANZ conference in Adelaide, he says.

A New York urban agriculture consultant, Henry Gordon-Smith, spoke about why vertical farming has taken off in the US; “one simple reason is fresh,” says Chapman.

In the US, leafy greens may often need transporting long distances to large cities. “So you can get reasonably priced old buildings where you can set up vertical farming close to large cities.

“In the States that is becoming quite economical as opposed to shipping in leafy greens for days in trucks. The degree of freshness with vertical farming is very acceptable to consumers.

“The cost of rentals for your warehouses can be quite prohibitive to a successful programme, and the cost of LED lighting and efficiency. But if you get the right building, LED efficiency is also increasing.”

But you can’t vertical farm, say, onions and potatoes.

“You are talking about leafy greens, but even in the States where there are lots of vertical farms, there will always be a place for soil-grown vegetables. It just gives you a bit of diversification, especially where the vegetables aren’t grown close to the cities.”

He knows of nobody vertical farming in New Zealand.

“NZ may not have the need because of the proximity of our growing operations to the cities, but as houses [replace] growing vegetables this may become one of the options.

“I have always been a little sceptical about it because we should be able to grow in our soil, but as we move forward we may find we’re stuck with it.”

Meanwhile, robots will replace some jobs but innovative people will always be needed in the workforce, says Chapman on another message from the conference.

“But the innovation is different from that required 10 years ago and even today. The skills for the future are creativity, problem solving, advanced reasoning, complex judgments, social interaction and emotional intelligence.

“In the workforces that are developing, a whole different set of skills is required which we should be training for and working on for the future.

“Robots will take away quite a few functions in future and the skills you must look to are skills that robots can’t do. Robots don’t have emotional intelligence, etc.”

Chapman says there was also much discussion about R&D in Australia, which is complicated. Much was said about research being dislocated from growers because of the complexity of the system. And too much research money is being spent on bureaucracy rather than the actual work.

“So you are not getting growers and researchers having the strong interaction we have in NZ to a far, far greater degree.

“In NZ we haven’t got federal versus state. We might think our system is complicated but the Australian system makes ours look rudimentary and straightforward.”

An Urban Farm Grows In Brooklyn

Tue Jun 6, 2017 | 8:12am EDT

An Urban Farm Grows In Brooklyn

By Melissa Fares | NEW YORK

Erik Groszyk, 30, used to spend his day as an investment banker working on spreadsheets. Now, he blasts rapper Kendrick Lamar while harvesting crops from his own urban farm out of a shipping container in a Brooklyn parking lot.

The Harvard graduate is one of 10 "entrepreneurial farmers" selected by Square Roots, an indoor urban farming company, to grow kale, mini-head lettuce and other crops locally in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn.

For 12 months, farmers each get a 320-square-foot steel shipping container where they control the climate of their own farm. Under pink LED lights, they grow GMO-free greens all year round.

Groszyk, who personally makes all the deliveries to his 45 customers, said he chooses certain crops based on customer feedback and grows new crops based on special requests.

"Literally the first day we were here, they were lowering these shipping containers with a crane off the back of a truck," said Groszyk. "By the next week, we were already planting seeds."

Tobias Peggs launched Square Roots with Kimbal Musk, the brother of Tesla Inc (TSLA.O) Chief Executive Elon Musk, in November, producing roughly 500 pounds of greens every week for hundreds of customers.

"If we can come up with a solution that works for New York, then as the rest of the world increasingly looks like New York, we'll be ready to scale everywhere," said Peggs.

In exchange for providing the farms and the year-long program, which includes support on topics like business development, branding, sales and finance, Square Roots shares 30 percent of the revenue with the farmers. Peggs estimates that farmers take home between $30,000 and $40,000 total by the end of the year.

The farmers cover the operating expenses of their container farm, such as water, electricity and seeds and pay rent, costing them roughly $1,500 per month in total, according to Peggs.

"An alternative path would be doing an MBA in food management, probably costing them tens of thousands if not hundreds of thousands of dollars," Peggs said, adding that he hopes farmers start companies of their own after they graduate from the program.

Groszyk harvests 15 to 20 pounds of produce each week, having been trained in artificial lighting, water chemistry, nutrient balance, business development and sales.

"It's really interesting to find out who's growing your food," said Tieg Zaharia, 25, a software engineer at Kickstarter, while munching on a $5 bag of greens grown and packaged by Groszyk.

"You're not just buying something that's shipped in from hundreds of miles away."

Nabeela Lakhani, 23, said reading "Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal" in high school inspired her to change the food system.

Three nights per week, Lakhani assumes the role of resident chef at a market-to-table restaurant in lower Manhattan.

"I walk up to the table and say, 'Hi guys! Sorry to interrupt, but I wanted to introduce myself. I am Chalk Point Kitchen's new urban farmer,' and they're like, 'What?'" said Lakhani, who specializes in Tuscan kale and rainbow chard.

"Then I kind of just go, 'Yeah, you know, we have a shipping container in Brooklyn ... I harvest this stuff and bring it here within 24 hours of you eating it, so it's the freshest salad in New York City.'"

(Reporting by Melissa Fares in New York; Additional reporting by Mike Segar in New York; Editing by Dan Grebler)

The Greening Of Alaska: Vertical Hydroponic Farming & Alaska Natural Organics Affect The Economy

The Greening Of Alaska: Vertical Hydroponic Farming & Alaska Natural Organics Affect The Economy

Lester Mondrag | June 05, 2017 | 02:38 PM EDT

(Photo : Photo by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images) Spanish Intern Isabel checks Corriander plants in one of the Underground tunnels at 'Growing Underground' in London, England. The former air raid shelters covering 65,000 square feet lie 120 feet under Clapham High street and are home to 'Growing Underground', the UKs first underground farm. The farms produce includes pea shoots, rocket, wasabi mustard, red basil and red amaranth, pink stem radish, garlic chives, fennel and coriander, and supply to restaurants across London including Michelin-starred chef Michel Roux Jr's 'Le Gavroche'.

Alaska is now an agricultural supplier of fresh fruits and garden vegetables that usually grows in the warm areas of California and Mexico. The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Natural Resource Conservation Services supports and funds the farming technique. The 49th state enjoys the funding and is now accelerating its farming industry with additional greenhouses for construction, the greening of Alaska is at hand.

The greening of Alaska has its people feel the excitement of the sustainable farming industry with support from the government; the last seven years saw some 700 greenhouses put up to support the growing demand of agricultural products for domestic consumption and export to other states. Agricultural produce would include fresh tomatoes, eggplants, peppers, tomatillos, Asian greens, kales, and almost anything under the sun, except January when the sun limits its shine. The sun is farthest during the first month of the year and only rises for five hours in the southern front of Alaska.

From February to December, the greening of Alaska continues the application of Hydroponic Farming. The whole eleven months, a huge tunnel becomes a greenery of edible produce for Alaska's economy. The insides of the greenhouse become what scientists call the "hardiness zone" which the USDA classifies as the best environment for growing fruits and vegetables.

The region of ice and snow is now Alaska Greening as local farmers can now grow from corn to melons at will, as the green tunnels are reliably warm. January even extends its farming month when the sun only rises for 5 hours in the southern coast of the state. The far North never experience sunrise and setting of the sun, reports Scientific American.

The two startup companies, Vertical Hydroponic Farming and Alaska Natural Organics impacts the economy and the greening of Alaska. The two companies apply hydroponics farming with only natural nutrient rich mineral water which is a soil and pesticide free technique. The vegetation bask under red and blue LED lights mimicking sunlight, reports Eco Watch.

The growth of indoor farming is booming as its economics is feasible to make the industry flourish, says Head of the US Department of Agriculture's Farm Service Agency, Danny Consenstein. Alaska will have sustainable farming and would be able to export its produce to neighboring provinces of Canada and other states in America.

5 Things To Know About Urban Organics Aquaponics Farm

5 Things To Know About Urban Organics Aquaponics Farm

Monday, June 5, 2017 by Mecca Bos in Food & Drink

Urban Organics aquaponics farm now has two locations in St. Paul

Many years ago, I stood with Dave Haider in a nearly empty grain silo at the old Hamm’s Brewery staring at a blue pool.

He had big dreams. One day, wife Kristen called him into the room, where she was watching TV.

“Look,” she said, and pointed. On the screen was an aquaponics farm, a closed-loop system for farming fish and produce. The fish enrich the water, the water is filtered through the root systems of the plants, and both are eventually edible for humans.

“You should do that.”

“OK,” said Haider.

And thus began their journey, along with partners Fred Haberman and Chris Ames, to implement Urban Organics aquaponics farm. The Hamm’s Brewery was their first location, and a second is now up and running in the Historic Schmidt Brewery. They’ve come a long way since a single pool in a silo.

Five things to know about the Twin Cities largest aquaponics farm:

1. Urban Organics greens are now available for purchase, including green and red kale, arugula, bok choy, green and red romaine, swiss chard, and green and red leaf lettuces. Get them at Hy Vee supermarkets in Eagan and Savage and at Seward, Wedge, and Lakewinds co-ops.

Want to taste the fish? Get it at Birchwood Cafe. The Fish Guys (local fish wholesaler led in part by Tim McKee) will be distributing Urban Organics fish, so watch for it at stores and restaurants in the coming months (more info on the fish below).

2. The farm was recently featured in The Guardian as a Top 10 innovative “next-gen” urban farm. Urban Organics was noted for using only 2 percent of the water used in conventional agriculture, and for its mission to prove the viability of aquaponics systems overall.

Other eco-friendly perks of the Urban Organics aquaponics system: they do not rely on herbicides, pesticides, or chemical fertilizers, and raising fish indoors takes pressure off oceans and wild-caught species.

More food raised in urban centers means less food traveling in from far-flung places. Urban Organics calls its product “hyper-local.”

3. The numbers: The 87,000 square foot Schmidt farm aims to provide 275,000 pounds of fresh fish and 475,000 pounds of organically grown produce per year.

Currently, the farm is at 30 percent capacity for produce, and they project being at full capacity by fall. Getting their Arctic Char and Atlantic Salmon to a harvestable size of eight to 10 pounds will take another 11 to 20 months.

4. If you happen to find yourself at a HealthPartners hospital, you might wind up eating Urban Organics food from your patient meal tray, cafeteria salad bar, or grab-and-go retail kiosk.

5. Part of the Urban Organics mission statement is to grow fresh food in urban “food deserts,” which would not otherwise have access to locally produced food. And with an indoor system, they can do it year-round, even in the dead of a St. Paul winter.

For more information on Urban Organics: urbanorganics.com

(Toggle around in their website. It’s kinda fun.)

700 Minnehaha Ave. E., St. Paul

543 James Ave. W.

Biosphere's Vertical Gardens Will Provide Produce For Public

Biosphere's Vertical Gardens Will Provide Produce For Public

- By Tom Beal Arizona Daily Star

- Apr 18, 2017

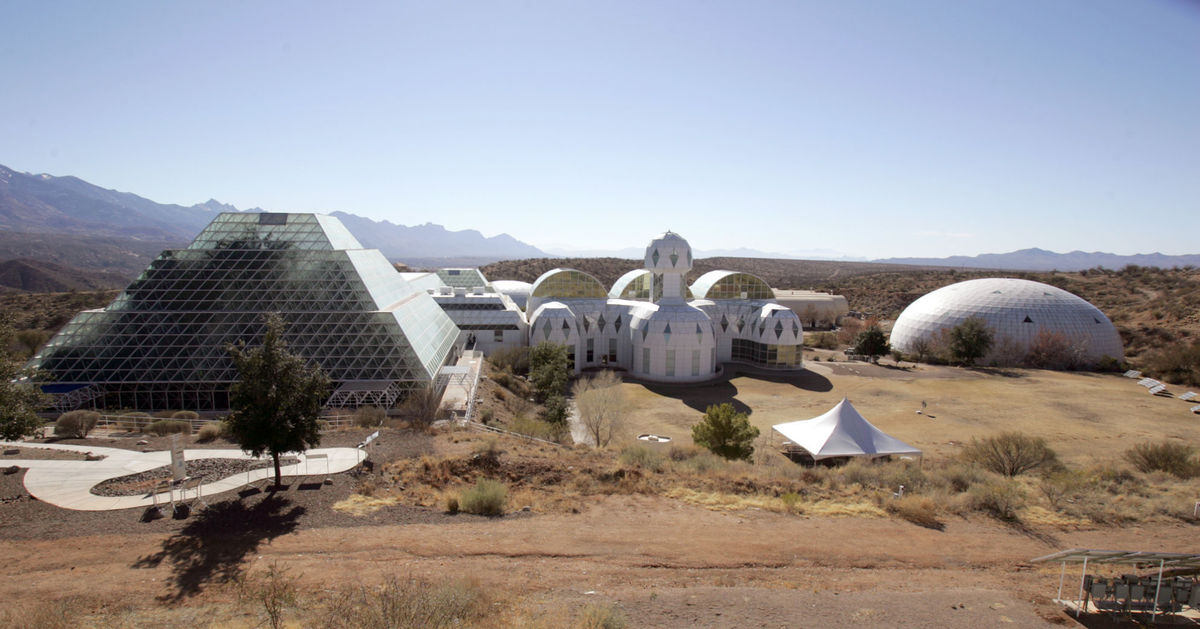

Food crops are coming back to Biosphere 2, but they won’t be planted in the 3 acres under glass at the University of Arizona research facility in Oracle.

A company named Civic Farms plans to grow its leafy greens under artificial lights in one of the cavernous “lungs” that kept the Biosphere’s glass from imploding or exploding when it was all sealed up.

The lungs, which equalized the air pressure in the dome, are no longer needed now that the Biosphere is no longer sealed. The west lung will be transformed into a “vertical farm” that will train LED lights on stacked racks of floating plants whose roots draw water and nutrients from circulating, fortified water.

A variety of leafy greens and herbs such as kale, arugula, lettuce and basil will be packaged and sold to customers in Tucson and Phoenix, said Paul Hardej, CEO and co-founder of Civic Farms.

He also expects to grow high-value crops, such as microgreens, Hardej said.

Hardej said the company plans to complete construction and begin growing by the end of the year.

Civic Farms’ contact with the UA allows for half the 20,000-square-foot space to be devoted to production, with areas given over to research and scientific education.

The UA will lease the space to Civic Farms for a nominal fee of $15,000 a year. In return, the company will invest more than $1 million in the facility and dedicate $250,000 over five years to hire student researchers in conjunction with the UA’s Controlled Environment Agriculture Center.

Details of branding haven’t been worked out, said UA Science Dean Joaquin Ruiz, but don’t be surprised to find Biosphere Basil turning up in your salad soon.

Hardej said the “brands” established by the UA were lures for his company.

“The UA itself has a brand recognition throughout the agricultural industry and specifically the Controlled Environment Agriculture Center. They have a lot of respect worldwide.”

“Also, the Biosphere itself is a great story,” he said.

“The original intent was to develop a self-sustaining, controlled environment where people could live, regardless of outside conditions.

“In a way, this is a fulfillment of the original purpose,” he said.

Hardej said he recognizes the irony of growing food in artificial light at the giant greenhouse. He is convinced, however, that growing plants with artificial lighting can become as economical as growing them in sunlight.

“Decades ago, greenhouses were very innovative. It felt like it allowed the farmer to control the environment. It did not control the light and also the temperature differentials.”

Hardej said indoor growing allows you to control all the variables — the water, the CO2 levels, the nutrients and the light. “Farming is much more productive and much more predictable than in a greenhouse,” he said.

You can’t stack plants on soil, or even in a greenhouse, he said. “A vertical farm can be 20 to 100 times more productive. The overall direction globally is indoors,” he said.

Indoor agriculture is still a sliver of overall crop production, said Gene Giacomelli, director of the UA’s Controlled Environment Agriculture Center (CEAC) and most indoor operations are greenhouses.